Introduction

The drum kit exists as a result of significant technological innovations and developments that have influenced the design and manufacture of its constituent parts. The drum kit can be defined as a technology in itself, in that it is a device that exists and functions as a direct result of ‘the practical … use of scientific discoveries’.1 The technological developments of the traditional acoustic drum kit have been recorded and described in articles in periodicals such as Modern Drummer (Modern Drummer Publications) and Rhythm Magazine (Future plc), and are comprehensively charted in Matt Dean’s book, The Drum: A History.2 Additionally, Matt Brennan (Chapter 1 in this book) provides a short historiography of the technological development of the drum kit in which he states that the definition of the drum kit is continually ‘in flux’; arguably, this has never been more true considering recent developments in electronic drum kit technologies and how they are used in performance by drummers.3

In this chapter, however, I have chosen to be mindful of the use of the word technology when discussing the modern drum kit setup, as the description of the drum kit as a technology may not be recognisable to many contemporary drummers. My choice is predicated on the growing use of the word technology to describe the electronic devices that permeate our every-day life. In this chapter the word technology will only be used in the context of the electronic technologies used to augment, or replace, the acoustic drum kit. ‘Technology has vastly extended the drummer’s sonic palette’ and in many cases, technology has also augmented the role of the drummer within their performance settings.4 These technologies include percussion controllers, sample pads, triggers, and music creation software(s) that are now commonly used to augment, or even replace, the traditional drum kit setup.5

This chapter seeks to open the discussion about how drum kit educators might embrace drum kit technologies as an exciting and highly relevant part of their curricula. Through examination of the experience of students studying my own drum kit technologies course, this chapter will propose ways in which educators might consider supporting their students to explore these technologies and develop valuable skills and knowledge by situating them at the heart of their student’s creative music making.

Situating the Drum Kit in Popular Music Education

This chapter is firmly situated in Popular Music Education, an emerging and expanding field of music research.6 Courses in popular music in higher education (HE) have only existed for around three decades and as such, educators are still developing teaching approaches that provide recognisable, valuable, effective, personalised and authentic experiences for their learners.

Drum kit is taught across a range of popular music performance courses at HE level, with tutors drawing on a series of long-standing approaches and methods to teach the instrument.7 However, the learning opportunities drummers might experience during their studies may vary based on: (1) the level at which they are studying; (2) the tutor with whom they are studying; and (3) the course they have selected to study. Most drum kit curricula have been designed based on what the tutor decides is valuable with some degree of personalisation for each student.8 Some courses will teach drum kit as an ensemble instrument with no, or limited, one-to-one tuition. On other courses students may receive a weekly one-to-one lesson, and in some cases, drum kit is taught to groups using electronic drum kits which have the same setup and layout as an acoustic drum kit, with each drummer wearing headphones.

From my own experience working as a drum kit specialist in HE, it is rare that drum kit curricula include teaching the creative use of drum kit technologies. In this chapter, I examine student perceptions of learning these technologies as part of their undergraduate studies at Edinburgh Napier University, Scotland. I explore the benefits of studying this course, the challenges students encountered, and discuss the implications of these findings for future course and technology development.

Teaching Electronic Drum Kit Technologies

Since 2008, I have been running a compulsory course that teaches drum kit technologies to drummers in Year 3 of the BA Popular Music degree programme at Edinburgh Napier University, Scotland. Drummers embarking on this course are performing at approximately London College of Music Diploma level, have studied at least two modules in music technology and have developed skills in music analysis.9 This prior experience equips students with the prerequisite skills to engage effectively with the learning on the course. The course has been designed to explore the full affordances of drum kit technologies, to provide students with a skill set that will support their creative and musical activity, and to produce versatile graduate drummers who have increased chances of employment in the music industry.10 From a music industry perspective, it is now commonplace for drummers to integrate technologies into their setup, therefore it is important that students have the opportunity to develop knowledge and understanding of drum kit technologies to enable them to perform the production-led music they aspire to play.

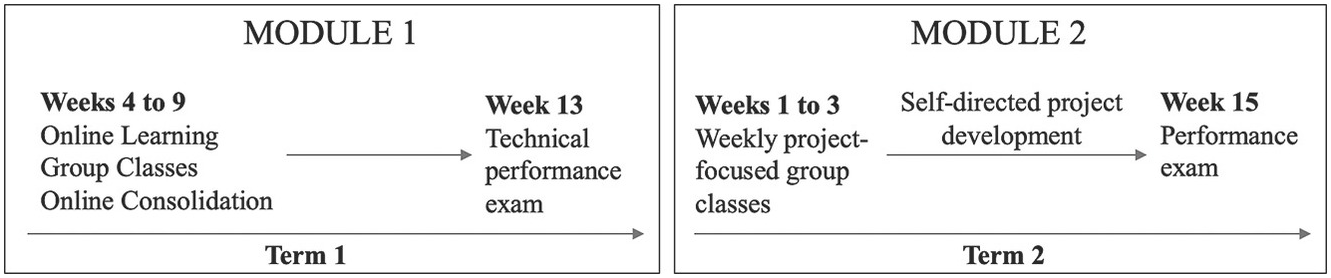

The course straddles two modules (Figure 10.1). In Term 1 students learn the functionality of the technologies then engage in a series of practical tasks and creative performances.11 The initial section of the course occurs across a six-week block. The curricular content is delivered using a flipped classroom methodology.12 Each week, students engage in online learning prior to class, participate in practical face-to-face group workshops, and engage in online individual and group consolidation activities. The primary drum kit technology used on this course is the Roland SPD-20 percussion controller.13 There are a number of reasons for this selection:

the simplicity of the user interface;

the ability to layer two MIDI notes on different MIDI channels on each pad; and

the controller is prevalent in contemporary popular music, the focus of the BA Popular Music programme.

Figure 10.1 The arrangement of the drum kit course within the two-performance module structure

In the initial weeks, students cover the following topics: accessing and editing sounds; acoustic and electronic drum triggers; the MIDI functions of the percussion controller; and connecting the controller to computer-based music software to access sampler instruments.14 At the end of the first term students are assessed on their performance of a set work for solo hybrid drum kit.15

In the second term students develop a solo performance to be played using only drum kit technologies and music software. The process of developing these performances requires students to:

1. analyse and describe their chosen song;

2. record, program, produce, and deconstruct the arrangement they will perform;

3. learn a new notation method and produce a score of their performance; and

4. develop a different approach to coordination that is driven by the complexity of musical arrangement which embraces both the affordances and the limitations of the technology.

Stages 1 and 2 above require students to analyse the music they are creating from multiple perspectives including melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, timbre, and from a music production standpoint. To successfully analyse and reproduce the music they want to perform, students need to understand the stylistic characteristics of the music, and the production techniques employed in the recordings. At this stage students are also analysing timbre – ‘all that is left after pitch and dynamic level’.16 The students deploy analysis skills to examine timbre to then accurately recreate sounds and produce quality reproductions of their chosen songs. Tutor support is offered at this stage, but in line with observations made by Tobias, students on this course regularly develop their production skills through researching and viewing online videos.17

Drivers for This Current Research and Method

Module-level feedback has always highlighted that students value the opportunity to learn these technologies as part of their studies. However, the feedback rarely provided detail, depth, or context on the learning experience. I chose to conduct qualitative research to gain a deeper understanding of the student experience on the course to ensure that the learning experience was relevant, valuable, and delivered effectively. I conducted semi-structured interviews with twelve drum kit students (two female and ten male) from Year 3 and 4 of the BA Popular Music course. Seven students studied the drum kit technologies course in 2017–2018 and five students studied the same course in 2018–2019. Three students had never used these technologies before and of the remaining nine students, the majority had used electronic drum kits as a direct substitute for an acoustic drum kit. All students had experience of using Logic Pro X, the music software used in this course. Interviews were recorded (with permission) and were fully transcribed. I scrutinised the transcripts and conducted a thematic analysis to identify emergent themes.

Research Findings and Discussion

The analysis of the transcripts exposed the following four themes:

Learning and Teaching Experience

The findings indicate that participants valued the opportunity to learn drum kit technologies. The student learning experience in Term 1 can be categorised into four distinct learning activities: (a) online class preparation; (b) face-to-face groupwork in class; (c) online consolidation activities; and (d) the preparation and completion of a summative assessment. In particular, participants felt that the flipped classroom approach used to structure and deliver learning experiences was of significant benefit to their engagement and understanding of the weekly topics.18 The online learning activities enabled students to prepare for class, increasing their confidence in the use of these unfamiliar technologies.

It meant that you could do it [learn] at your own pace so you could pause videos instead of taking up class time … if you watched all the videos everything you needed to know was all in those videos … It also meant that if you forgot something, then you could go back. Participant 4 (Year 3)

It was like having a one-on-one lesson with you [the tutor] that never ended because we were able to go back and double check everything. If there was a bit that we didn’t understand, we were able to rewind … It gave me the knowledge on a one-to-one basis at a time and place, and pace that suited me best. Participant 6 (Year 3)

The comments received in relation to the preparatory activities highlight that the use of video demonstration was highly effective in enabling learners to develop a deep understanding of how the technologies function. This approach mirrors the way in which many instrumentalists use online video streaming services such as YouTube or Vimeo, or specialist instrumental education sites such as Drumeo, or video created by their tutor in formal, non-formal and informal contexts.19 The asynchronous nature of this online delivery had a positive impact on student learning, enabling students to study and review materials at their own pace, at a time that suited their schedule.20

Traditional acoustic drum kit tuition does not suit group teaching settings for a variety of reasons, for example, only one person can play the kit at a time and the volume and space considerations of having more than one kit in a room. These issues are somewhat mitigated when using drum kit technologies as their volume can be controlled, the equipment often occupies a smaller physical space, and if resources allow, multiple drummers can be playing and learning in the same space.21 This approach can be seen in many institutions where rooms are filled with electronic drum kits set up in rows facing the teacher. However, this approach does not necessarily support what Lave and Wenger describe as a ‘community of practice’ or promote collaborative learning, since the drummers are working individually.22 In this setting, the in-class activity is not predicated on sharing or co-creating knowledge, or collective problem-solving. A significant difference in the way my course is delivered is that there is very little tutor direction in group workshops. Students collaborate to complete a series of tasks and share their learning and understanding in the group. This enables the students to enter what Vygotsky describes as the ‘zone of proximal development’ i.e. the collaborative learning environment enables students to develop a deeper understanding of the equipment compared to completing the tasks individually.23

They [group classes] were really good in terms of other people coming up with questions … all of us basically are teaching each other and learning from each other’s mistakes and problems. Participant 3 (Year 3)

I really enjoyed it because it was collaborative … If one of us figured something out, the environment was tailored to enable us to share that … it tended to be that someone would experience a problem, and once we found the solution, the whole class would know. Participant 12 (Year 4)

Following workshop classes students engage in a range of online consolidation tasks, some of which are used to develop a community of inquiry.24 The tasks included: sharing videos that demonstrate the skills developed in the previous class; writing research-led collaborative blogs to explain the functionality of certain technologies to the class; and sharing research into drummers who use technology in live performance. Students recognised that by completing each task they deepened their knowledge and increased their confidence in using these technologies.

It was like a recap on what we had gone through in class. It obviously gave you [the lecturer] confidence knowing that we could do it [in class] and then go away and do it again. Participant 9 (Year 4)

It was very important that the tasks we were set were determined on what we had learned in class … and being able to show what you had done in your own time to everyone else was pretty cool. Participant 7 (Year 4)

Working with Notation and Developing Coordination

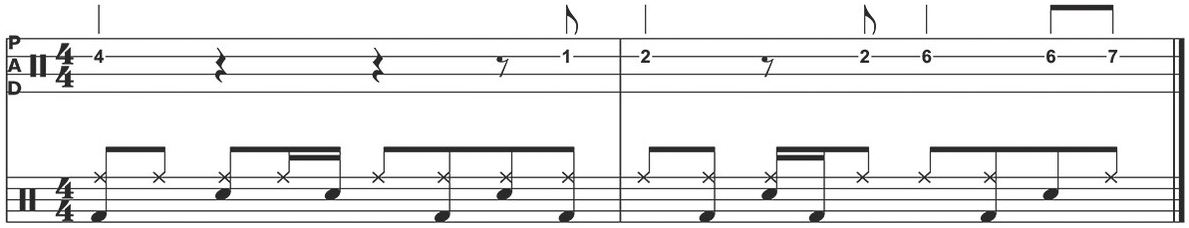

Approaches to scoring music for hybrid drum kit so far have negated to include directions for coordination and assume that the learner will be able to ‘work it out’.25 This may be the case if the coordination required to trigger the electronic sounds is an obvious substitution for elements of an original groove. For example, Example 10.1 shows notation of a simple hybrid performance. The pad strike in bar 2 is played using similar coordination to that used in bar 1.

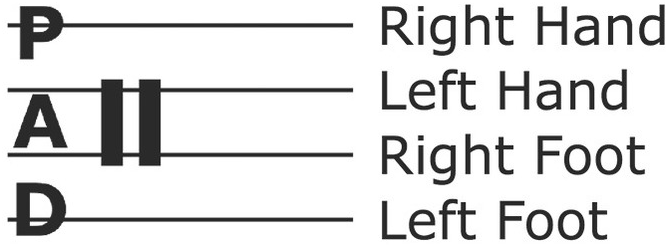

Most drummers would be familiar with the coordination required to play the groove in Example 10.1, and the process of substituting a different sound source on beat one is similar to the coordination used to play the crash cymbal when introducing a new section of an arrangement. However, if the coordination is not clearly mapped for the learner, there is always a chance that the coordination they apply will not be the most straightforward or efficient. In Figure 10.2, the coordination used to perform the pad strike may seem obvious – for a right-handed drummer the pad could be played by the right hand in substitution for the hi-hat. However, it could just as easily be performed with the left hand allowing the drummer to also play the hi-hat on beat 1 of the second bar. Clear signposting of the required coordination is vital to ensuring economy of motion and to allow as much of the existing or underlying groove to be maintained.

A key feature of this course is that drummers learn a notation system specifically for electronic drum kit technologies. This notation system can represent the coordination, rhythmic phrasing, and the pad numbers that are to be struck to activate sounds (Figure 10.2 and Example 10.2).

Figure 10.2 The PAD notation clef and legend

Example 10.2 Notation of a hybrid performance. The left hand is used to trigger the electronic elements of the performance

This notation method has been highly effective in supporting the process of learning and sharing music, so much so that students have learned the notated performances without actually practicing on the technology. Students often use a piece of paper with the SPD-20 layout drawn on it and learn the coordination required by tapping the numbers in the grid to familiarise themselves with the patterns (See Figure 10.3).

Using the PAD notation, students were able to quickly learn the coordination required to perform new pieces.

I really liked it. I thought it was brilliant, I have never seen anything like it. It’s unique. I think each limb having its own line on the stave really works. Participant 9 (Year 4)

It was quite easy to read, it also just … makes sense. I hadn’t seen any pad notation before, it was good. Participant 10 (Year 4)

When we examine the educational publications that focus on developing coordination and dexterity, almost all are predicated on developing these skills in relation to the acoustic drum kit setup.26 Hybrid and fully electronic performances provide an alternative way of developing coordination. Cameron suggests coordination, and creative performance, can be developed through reallocating patterns with grooves to different limbs on the traditional drum kit.27 When drummers use drum kit technologies to activate melodic, harmonic and/or rhythmic elements of a piece, performances will require non-standard coordination that will rarely be recognisable as a groove or fill. In fully electronic performances any limb can activate any sound which greatly enhances the opportunity to manipulate and develop coordination. For example, to increase challenge, drummers might make significant use of their non-dominant hand to trigger parts of the arrangement. Additionally, increasing the rate at which sounds are triggered can make the performance more difficult. Changes made to these variables can pose significant challenges to the coordination of drummers who have only learned patterns on acoustic kit. For many, integrating electronics often feels like playing two instruments (or more) at a time. During the interviews it was clear that students recognised that their coordination was challenged and that it improved as a result of performing the set work.

The conceptual challenge of playing drum kit differently, or of utilising technology for performance, which I don’t think any of us had previously done, changes the way you think about your parts. Suddenly you are not thinking about drum beats you are thinking about musical parts that have to be played and from a coordination standpoint technically you are changing what you do with your body. Participant 12 (Year 4)

The coordination was probably the hardest part for me … It definitely got you used to wrapping your head around the completely different way you have got to approach actually playing … Once you have got your head around the coordination, playing grooves whilst playing the added sounds in amongst that, you are kinda set to do anything you want when you are just solely [playing] on the electronics. Participant 3 (Year 3)

Employability

Although electronic drum kit technologies emerged in the late 1970s, they have only recently started to feature in the kit setups of a significant number of drummers. Several factors have influenced this growth, such as: lower relative cost of purchasing equipment; the greater choice of products available to drummers; an increased expectation that highly produced sounds are replicated in live performances so that artists ‘sound like the album’. As an educator based in the HE sector, there is significant pressure to produce employable graduates.28 This expectation greatly influenced the development of this course. Students felt that the course enhanced their employability and furnished them with vital skills for their future career.

I’ve been hired to perform as part of a pit band for a musical and the whole premise is that I will be using a sample pad alongside the kit I’m playing the kit, percussion, sound effects or samples that they need. It just gives you another notch on your belt. It’s another bullet point on your CV … in the modern climate of what music is, electronics are very important. Participant 6 (Year 3)

It’s done a lot for it [employability]. Every band that you see playing anywhere there’s not a drummer who doesn’t have a sample pad or trigger here and there. I think it’s vital for drummers going forward to be able to use this stuff … not being able to program something stops you from being able to play almost every song that is in the charts right now. Participant 4 (Year 3)

Desired Course Developments

The current course expects students to demonstrate their use of the technologies in solo performance settings. A number of students discussed their desire to explore the use of technologies in band settings. Using solo performances with technology as the focus for the course ensures that the learners understand, explore and demonstrate the technology’s full potential. However, it is understandable that students would want to learn to use it in settings where they will most likely use it in the future.

It might be worth … using it [percussion controller] in more of a live setting … having like a hybrid acoustic kit and then triggering clicks and samples … I feel like the Spitfire piece in the first trimester probably benefited me more than the second trimester piece that we had to do, only because I have not been in a situation where I have had to use it [SPD-20] as a MIDI controller and make all my own stuff [samples] even though I think it is so beneficial. Participant 2 (Year 4)

While the notation method used to communicate the physical coordination, rhythmic phrasing and pad numbers is clearly effective and enables students to learn pieces quickly, students described their experience of checking the accuracy of their own PAD scores using the notation software as challenging.

The only thing I wish is that you can actually hear [the samples produced by Logic X] … when you are playing it [the score] in Sibelius, it was crazy … If you could choose each of the numbered sounds even if it wasn’t what you were actually programming. If you could choose something that was kinda close I think that would be really useful cause you had no idea if you had put it all in right just by looking at this page of numbers. Participant 1 (Year 3)

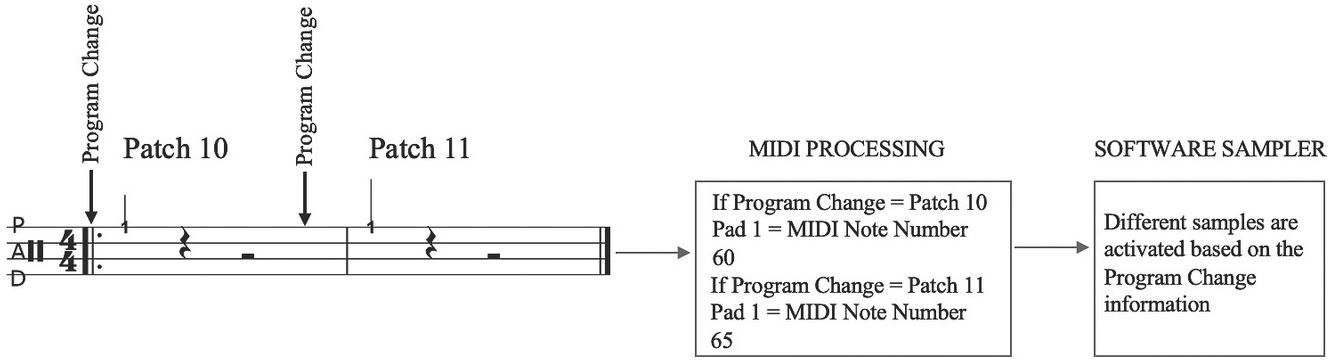

The problem experienced by this student defines one of the key challenges associated with the scoring and playback process. Traditional scoring software provides a visual representation of programmed MIDI information. The software uses MIDI information to play back the specific pitch or tone that is notated (melodic or harmonic), or mapped (drums and percussion), i.e. each piece of notation links to a specific pitch or sound for the duration of the score. The numbering system used in the PAD notation only gives a visual representation of the pad to play, the coordination to be used and the rhythmic phrasing. The score does not produce MIDI information that maps directly to the sounds used across an entire performance as the sounds that need to be activated are constantly changing based on the patch.

The PAD score has to be generated by typing in the pad numbers on the music scoring software. Currently it is impossible to capture a live performance that will automatically map directly onto the PAD music notation in the scoring software. This is because the additional information needed to produce the score, pad number and the limb it is played with, is not represented by a MIDI message and therefore cannot be recorded in the scoring software.

Reflection

Based on the research findings presented, this course is clearly deemed as valuable by students in that they feel they are learning important skills that will support their future career. Much of the music that these students play and listen to is production-led and many of them are turning to technology to extend the sonic palette available to them, recreate sounds produced in the studio, and in turn, enhance their role within their bands. Students recognised that the tasks set for summative assessment posed significant challenge and encouraged them to learn and make use of the technology in ways that stretched their abilities as a drummer, producer, and arranger of music. It is evident that they feel the learning experience is valuable not only in terms of their development as a drummer, but also in terms of the development of wider skill sets relating to group work, autodidactic learning practices and problem solving. The learning and teaching methods used to support the delivery and consolidation of core knowledge have motivated and enthused learners to engage with complex and somewhat abstract concepts. The course has provided an opportunity to explore these concepts to a deep level within a structured curriculum that scaffolds learning and provides opportunities for personalization.29 The learning experiences in Term 1 enable students to develop an understanding of, and familiarity with, the PAD notation system. This approach ensures that when students create their own PAD scores, they are able to accurately capture the coordination and pad positions required to recreate a performance of their chosen song.

Performances using drum kit technologies in hybrid and fully electronic settings pose significant challenge to the coordination that these students have developed on the traditional acoustic drum kit. This is an exciting finding, as this alternative approach to teaching and developing coordination may provide a new avenue for drummers to develop what Cameron describes as ‘multi-dexterity’ and freedom of movement that can affect improvement in all areas of their drum kit performance.30 The change of mindset students experienced when performing in hybrid settings where they are now playing a new instrument is an interesting finding that requires further examination and research.

Student responses identified opportunities to further develop the course and explore other ways of using the drum kit technology. In particular, the findings suggested that two parts of the course need to be examined: (1) the setting of performance tasks that mirror how the technology is commonly used by drummers in industry and (2) how the PAD notation might be manipulated to activate the correct sounds in the music software.

Point 1 is straightforward to address through course revision. It is clear that students are keen to explore ways in which they might use the technology in more recognisable performance settings that might enable what Joseph Pignato describes as ‘identity expression’ and ‘idiosyncratic purposeful creation’, where students have the freedom to use the technology in their own desired musical setting.31 Reflecting on the feedback, providing an opportunity to explore how student choice can be factored into the course design is an exciting prospect. Performing with technology in a band setting has been largely neglected based on the assumption that by studying the course as is, and through developing the advanced skills required to address the needs of the solo hybrid and fully electronic performance assessments, students will have covertly developed the skills to use the technology in an ensemble.

Point 2 presents a set of more significant challenges. Firstly, capturing a performance through the recording of MIDI information would not be possible as the MIDI note that is recorded for a single pad varies based on the active patch. Therefore, the scoring software would represent the pad differently each time the patch changed. The information that needs to be captured by the software is the pad number and the limb to be used to activate it. However, this problem poses an exciting challenge as no manufacturer currently offers a feature that enables the pad number to be captured by the software during recording. If this problem could be overcome, the information captured during a MIDI-based recording would be an accurate representation of the performance.

Secondly, the challenge of being able to check the accuracy of a PAD score presents a complex, but not insurmountable, problem. If there was a way to use the programme change information to alter the MIDI notes output by the software, then it would be possible to play back the correct sounds using the PAD software score. This could be achieved through the use of an intermediary software program that enables MIDI note information to be remapped to a different note number based on Program Change information (Figure 10.4).

The drum kit has evolved and extended to meet the needs of the musics in which it is used. Drum kit technologies now enable drummers to accurately replicate the sounds heard in recordings and to extend the creative and musical possibilities of the instrument. With any development of the drum kit, we witness an advancement of the technique(s) associated with said development; for example, the development of the bass drum pedal has spawned techniques such as heel down, heel up, slide, swivel and heel-toe. The associated pedagogies then follow, with educators developing methods of teaching and sharing said techniques. We are now in an era where teaching the fundamentals of technique and musicianship are still central to a drummer’s development, but as educators responsible for training and mentoring the next generation of drummers, drum kit technologies provide a new and exciting area of study to explore in our curricula.

Introduction

In this chapter we examine how drummers are taught and learn to conceptualize and execute expressive variations of familiar drumming patterns, i.e. ‘feel’-based aspects, and the enabling conditions that underlie them. We draw from multiple sources including analysis of sound recordings, theoretical models proposed by philosophers, psychologists, and educators, interviews with experienced drummers, and our own teaching and performing experiences and reflections. We explain the conditions under which these technical nuances develop in the early-stage drummers we have worked with, and despite the resistance of these nuances to straightforward or specifiable instruction, their indispensability to ensemble leadership and drumming success. We first begin by exploring some of the creative and interpersonal characteristics that are beneficial to drumming success, then analyse the teaching and learning of some of the techniques themselves. We then conclude with recommendations for teaching drum kit in music classrooms and private tuition studios.

Creative Framework

Curiosity, Creativity, and Musical Expression

While straightforward to isolate drumming skills and understandings facilitating discrimination between drummers of different ability levels, it is comparatively more challenging to account for how and why some drummers learn more quickly and achieve more than others. We have observed that some learners progress by demonstrating a natural affinity for the drum kit – historically conceptualized as talent in music education and psychology – while others rely more significantly on tenacious effort. An alternative perspective might consider what helps someone maximize one’s talents or efforts, suggesting that motivation for high achievement is the critical attribute, in which case curiosity might well be the best explanation for effective learning. According to Jordan Litman, curiosity is a desire to understand something that motivates exploratory behavior to acquire new information, which is pleasurable whether done for its own sake or to reduce uncertainty.1 Curious individuals learn better and faster than those who are less curious. Curiosity is also a prerequisite condition of creativity, which in turn drives musical expression as well as many conceptions of intelligence. We will now take a closer view of intelligence, creativity, and musical expression as they pertain to drumming performance.

Robert Sternberg’s multifaceted theory of successful intelligence is well-suited to explain the complex actions of drum kit playing.2 According to Sternberg’s theory, an intelligent person optimizes four types of skills: creative, analytical, practical, and wisdom-based. Drummers must be creative in order to extend their personality through their instrument – what allows one to recognize a drummer by listening to his or her playing. They must be analytical to understand what works best, and why, from the entire range of potentially useful ideas. They must be practical in order to convincingly unify ideation with muscular motion. They must be wise to marshal these skills in such a way that they favourably serve the interests and ensure the success of the ensemble.

The creative skill of drummers is mediated within the social matrix of an ensemble, with motivation commingling among intrinsic and extrinsic sources. At least since Teresa Amabile’s study focusing on creative situations there is widespread acceptance that creativity is best achieved through intrinsic motivation, suggesting that drummers must negotiate their contributions in a resilient manner even while making themselves vulnerable to praise and criticism, neither of which are necessarily supportive of creative behaviour.3 Illustrating this point, the 1997 CD reissue of The Byrds’ LP The Notorious Byrd Brothers, the final bonus track, entitled ‘Universal Mind Decoder’, contains an extended dialogue in the recording studio between guitarist and singer David Crosby and drummer Mike Clarke, in which Crosby attempts to inspire Clarke to improve his performance using various approaches, all unsuccessful.4 Sternberg and Lubart’s investment theory of creativity is another applicable explanation of how drummers function creatively within ensembles – they often ‘buy low, sell high’, i.e. introduce ideas that are initially unfamiliar and unusual, persist and adjust until they are consensually accepted as part of the ensemble’s ‘sound’, then begin the process anew.5 Thus, drummers must be prepared to fail whilst prospecting for successful pathways.

Creativity additionally provides the foundation for musical expression, defined by Roger Scruton as ‘those elements of a musical performance that depend on personal response and which vary between different interpretations’.6 Introduced in Carl Seashore’s pioneering work in the psychology of music, musical expression comprises deviations from mechanical performances of time, pitch, loudness, and timbre.7 The feel-based constructs we review later fall neatly into these categories: using them promotes musical expression, which is essential for communicating one’s personal understanding of the music. In the philosophical literature, John Dewey’s Art as Experience provided a convincing explanation of how expression is at the core of creative reasoning, delineating expressive acts and objects as the processes and products of artistic self-definition.8 And in the psychological literature, Alf Gabrielsson’s development of systematic variation of duration (SYVAR-D) revealed that deviations from mechanical regularity are rarely either random or the same: rather, they are undertaken to emphasize the perceived importance of structural features.9 Therefore, while drummers might enjoy the freedom to experiment with various rhythmic possibilities, they ultimately are bound by musical genres styles, and forms, and the skills and attitudes of other ensemble members.

Leveraging the Roles of Drummers in Ensembles

If drummers do enjoy some creative autonomy in their ensemble as musicians, they also inherit some responsibility as a focal point of ensemble collaboration: drummers actively negotiate and enact adjustments that benefit group cohesion. In our extensive teaching novice rock band members, we note their perceptions that drummers are considered somewhat less suitable for singing duties. Their reasons include that drummers must listen to everyone more closely than other band members, that they carry the burden of executing structural cues, and that they are more physically involved, i.e. playing with both hands and feet, making singing too difficult. While these reasons may not be limiting of singing ability, they suggest how novice band members tend to view the roles of drummers and the demands of the drum kit.

In a performance by the group Three Friends of the song ‘Prologue’, drummer Malcom Mortimer counts off the tune, ‘leading’ the group in at a pace he immediately realizes is too fast, given the complex melodic figures played by the other five performers, thus he adjusts the tempo down, momentarily ‘following’ the group.10 One characteristic of a more advanced drummer is to make such adjustments without compromising personal, expressive technique. Honing and Bas de Haas studied the performances of experienced jazz drummers, finding the long-short subdivision of the beat commonly known as ‘swing’ is not related linearly to tempo, i.e. expressive timing is adapted to tempo variations.11 Alternatively, John Churchville, a professional drummer, teacher, and recording artist, believes that while drummers might represent the ‘swing’ by first providing the beat on the ride cymbal, and round out appropriate beat divisions with the other hand, the success of the effect is group-determined, i.e. ‘swing’ is not initiated, controlled, or achieved solely by the drummer: rather, all ensemble members mutually participate in the process, which is mediated primarily by the level of their listening skills.12 The extent to which creativity is encouraged, required, or exercised by drummers is contingent upon the specific performance environments. Bill Bruford characterized different ‘contexts’ in which experts perform, which differ in the relationship of the drummer to a group leader, whether there is a leader in the first place, and the level of creative freedom available, either ‘functional’ or ‘compositional’.13 It should be noted that even when drummers are performing for a leader who commands complete stylistic control over the music, there is still some room for creative thinking. Brazilian jazz drummer Airto Moreira, describing the process of finding a percussion part whilst everyone else in the group is scrambling to occupy every available space in the musical texture, said ‘you just have to find a place that no one else is using, even if it is an unusual space, and fill it up and keep playing there so no one can take it away from you’.14 Moreira further explained that performance situations which offer formative roles are attractive to drummers, since most ensembles ‘need someone to help everyone else make sense of time’.15

The demands on drummers are varied and complex, and it requires manipulative skill, tenacity, and strong interpersonal skills to confront them. There is additionally the need for drummers to simultaneously conform to tradition while incorporating their trademark sound through selected techniques. Peter Abbs described a hypothetical aesthetic balance between tradition and innovation, which is achieved through instruction and reflection.16 It is therefore perhaps optimal that drummers be purposefully mindful of such aesthetic balance in their playing, and search for evidence of such balance in the playing of successful drummers. For example, the late drumming legend Jeff Porcaro was perhaps best known for his much imitated ‘half-time shuffle’ groove, a modified rendition of Bernard Purdie’s earlier ‘Purdie Shuffle’, and already familiar to music listeners, thus likely related to the success of Porcaro’s signature sound. He further combined this element with a kick-drum rhythm – the legendary ‘Bo Diddley Beat’, perhaps the best-known syncopated pattern in popular music. Porcaro’s effort was a perfect example of combinational thinking – fusing established sounds to produce a captivating beat pattern. Despite the literature and recordings that highlight the independently creative roles of drummers, some performance tendencies have emerged in drummers’ efforts to create unique musical grooves. Danielsen et al. asked ten expert drummers to play a rock pattern at three different tempi using three timing styles – ‘laid-back’, ‘on-the-beat’, and ‘pushed’ – and noted systematic variances in intensity and timbre of snare drum strokes between tempi and styles.17 These findings suggest the gradual formation of normative sound cues which accompany a drummer’s efforts to create groove.

We now turn our attention to the practice routines and techniques associated with drum kit instruction, intending to link them to the aforementioned personal habits and challenges of successful drumming. Specifically, we identify skills associated with effective drum kit playing, map the cognitive understandings required for their execution, consider the dynamics of ensemble playing and their influence on drumming technique, and invoke the advice of expert teachers as to the optimal ways to educate young drummers. We also reintroduce the idea of aesthetics and how it may relate to the concept of timekeeping.

Technical Framework

Background

Before discussing drum kit method book literature, we first look briefly to some psychology research,18 as well as computer modeling of neurological processes to establish some aspects of conceptual modeling for rhythm in the human mind.19 Human beings undergo a process of informal musical learning as they grow up in a cultural setting; this includes implicit understanding of how tonal and rhythmic aspects of music ‘work’. Rhythmic aspects of this framework include beat induction, meter induction, and architectonic relationships between multilayered timescales. Conceptual modeling of rhythm is significant for the teaching and learning of drum kit from multiple angles. On the one hand, recorded and live performance of drum kit playing is rooted in performers’ conceptual modeling of rhythm; conversely, the ensemble members with whom they perform, as well as listeners, map the experienced music onto their own conceptual models and frameworks.

Procedural Aspects from Method Books

Method books have addressed the role of the drummer in musical settings. These books have focused on challenges facing drummers as well as recommendations for how developing drummers can work towards meeting those challenges. Jazz drumming expert John Riley addressed the need for a drummer’s playing to appeal to a bandleader, stating that, ‘The bottom line is, people hire drummers who make them sound good – period’.20 Ron Spagnardi described how big band drummers cannot depend on written notation in a drum chart to tell them all details about what or how to play. ‘With just a basic sketch to go by, you need to depend on your musical instinct and creativity to decide what to play, how to phrase, where to fill, and how to accompany the soloists’.21 Daniel ‘Zoro’ Donnelly and Daniel Glass described common challenges facing developing drummers in the rhythm and blues idiom, citing, ‘poor understanding of swung eighth notes … improper sound balance … misdirected motion … lack of understanding’.22 These challenges address the necessity of creativity, identity, and effectively fulfilling a timekeeping role with a rhythm section.

Additionally, method books have used language as an analogy to describe drummers’ abilities to function authentically in diverse stylistic contexts. Towards the development of properly grooving within R&B, soul, funk, and hip-hop styles, Mike Adamo stated, ‘breakbeat drumming has its own vocabulary, just as any language does’.23 In discussing grooves particular to Afro-Cuban drumming, Ed Uribe wrote, ‘your final goal in the study of a musical style should be … strive to play this music as if you had learned it in its purest, handed-down, oral tradition … There is a big difference between playing a beat and playing a style … You are, in essence, learning a language’.24 Riley emphasized the importance of listening to examples from musical styles in order to develop idiomatic understanding. ‘To be fluent in any style of music, you must know the “dialect” … All the great players we know have studied hundreds of recordings and have listened to and probably own a thousand or more jazz recordings’.25

Method books have also offered suggestions for how developing drummers ought to meet these challenges. Donnelly and Glass insisted on the importance of understanding historical context. ‘In order to reign and rule over the groove (of rhythm and blues) and play it convincingly, you must first understand how it got there in the first place and how it evolved into what it is today’.26 One stylistic example that they cited towards effectively grooving in early R&B idioms was the shuffle: ‘When it comes to early R&B, there are three important tools that a drummer can’t live without: a good shuffle, a good shuffle, and a good shuffle! … If you start simple, focusing on sound and balance (as opposed to technique), you can develop a basic shuffle that will get you through just about any musical challenge that comes your way’.27 Towards drummers’ development of groove, individual creativity and musicianship, and effective ensemble performance, Riley’s suggestions included, ‘open your ears to the other players. Play together … think like a musician. Make the other players sound good … play your own time, not your idol’s … think consistent spacing and volume. Hypnotize with your groove … when there are problems (with ensemble cohesion), play strong but become more supple, not more rigid’.28 Adamo’s suggestion for drummers’ development of groove and pocket was ‘playing along with recorded songs … playing along with a metronome/click track … feeling an underlying half-note or whole-note pulse as you practice/play various grooves’.29

Towards an Aesthetic of Timekeeping

If we propose there is an ‘aesthetics of timekeeping’ in the first place, it must be predicated on, yet transcend, requisite skills and techniques. What renders the timekeeping ‘aesthetic’ is a transformation from purely functional actions and executions to apprehend the expressive qualities of the activity, to engage the communicative potential of music. Drum teachers spend a lot of time, informed by method book authors, teaching students how to strike the drum, count, play four-way coordination, read charts, listen to music for dialectic fluency, balance the various instruments of the drum set, and function appropriately in music ensemble settings. Drum teachers teach these techniques and skills, hoping that creativity emerges from students’ practice as they work to attain them. Our position is that these techniques and skills emerge in confluence with students’ developing creativity. The most effective teaching and learning of drumming maintains focus on the aforementioned techniques and skills, executed using strategies that additionally help students develop the dispositions that are associated with creative reasoning and action. These include embracing the centrality of listening as the key to learning and ensemble performance, awareness of rhythm framework, improving negotiation of the social dynamics of being a drummer, and a personal creative style that balances tradition and innovation while continually testing new ideas amidst various enabling and inhibiting conditions.

We therefore recommend a practice repertoire of actual musical examples to supplement method book use, in which teachers saliently indicate the history and innovations of drummers from prior eras.30 Two examples of such practice repertoire include listening and playing along to jazz standards and break beats. These two bodies of repertoire represent much of the relevant drumming idiom in the twenty-first century. Jazz drummers from the early to mid-twentieth century influenced drummers across many styles of popular music from the latter half of the twentieth century to the early twenty-first century.31 Sampling and recreation (through performance or programming) of R&B and soul break beats has been prevalent in popular music of the past forty years. In addition to assimilating a repertoire of relevant beats and songs, study of this repertoire might well refine developing drummers’ conceptual modelling for rhythm towards an increasingly detailed template for groove and pocket that includes swing, centeredness on the beat, and elasticity of time.

Given the aural tradition of the drum kit, and that ideas about swing and pocket differ among various musical styles, we recommend use of listening and play-along to help drummers develop intuitions towards idiomatic performance of musical styles. In this regard, developing a sense of pocket is akin to achieving a colloquial and conversational fluency in various musical genres and styles. Developing drummers should assimilate repertoire aurally, only using notation when necessary to achieve optimal comprehension. Learning break beats and songs by ear will engage the developing drummer in a process of disequilibrium and reconciliation, interacting as directly as possible with the music.32 While notational skills are important in professionalizing drummers, superb aural skills are foundational in virtually every aspect of drumming, thus need not be tied to note-reading. The practice of reading musical notation should focus on norms of reading charts as musical ‘road maps’ with important clues about how to engage with and lead the ensemble: the details of musical interpretation should be left largely to drummers’ intuitions, developed through listening and play-along repertoire. As John Churchville reports, early-stage drummers tend to be consumed with striking drums and making as much sound as possible through intense exertion, and only once they realize how this practice interferes with increasing demands on their listening, their technique can become more efficient and varied. The late drumming educator John Bergamo, one of Churchville’s teachers, encouraged improved technique through examining the natural mechanics of the body (the basic ‘throwing’ motion), making better use of gravity, and incorporating various parts of the striking surfaces for expanded timbral range.

Indeed, developing drummers are typically preoccupied with the physical act of playing drums. Consequently, one of the challenges for a drum kit teacher is to help channel this preoccupation towards a more developed musicality and musicianship. Two groups developing drummers must learn how to please are other musicians with whom they perform, and audience members. Groove and pocket are particularly important in both instances: fellow rhythm section members judge drummers’ ability to groove in a group setting (based on cognitive conceptual models of groove), and listeners’ experiences of popular music include groove and pocket as well, though perhaps based on more generalized conceptual models.

Developing drummers are also listeners, however. When they commence systematic study of the drum kit, they do not do so in a musico-technical vacuum. Therefore, much of what we emphasize in teaching developing drummers about groove and pocket may be a process of making salient, thereby more consciously present, the conceptual models they bring to the studio setting as advanced listeners. This supports a student-centred model of teaching and learning, whereby we encourage students to bring their whole selves into the classroom setting. We meet them where they are as learners, developing their understanding that listening is key, guiding them towards a professional level of fluency within popular music dialects.

Feel-Based Drumming Constructs

For drummers to develop awareness of rhythmic framework, they should develop fluency within the overlapping, abstract, feel-based constructs of swing, groove, and pocket. These constructs break down into several aspects, such as beat subdivision, centredness on the beat, elasticity in interpretation of time, and dynamic balance among voices on the drum kit. Beat subdivision is also sometimes referred to as ‘depth of swing’. Usually, a drummer is described as playing ‘in the pocket’ in relation to one or more other players, often other rhythm section players. A groove that is pocketed in one context may be completely out of the pocket in another. In this regard, pocket is an agreement among several players, often the rhythm section, as to how hard the music will swing. While there is widespread acceptance for these constructs in the Western music world and in some parts of Asia,33 the practices themselves are familiar even when the constructs are not, as in the case of ‘groove’ in England.34

Centredness on the beat refers to how ‘on top’ of the beat the drummer plays, versus how far ahead or behind, meanwhile not rushing or dragging to the point of tearing from the pocket. A drummer simultaneously must match the beat-centredness of the rest of the rhythm section, but also inherits a greater responsibility than other rhythm section players in determining the beat-centredness of the entire rhythm section. Such considerations concerning micro timing signal the influence of popular music genres in modern rhythmic discourse and analysis.35

Elasticity refers to the dynamic pushing and pulling of time: sometimes when entering or exiting phrases, playing fills, set-ups, or ensemble hits, the time seems to organically stretch to aesthetic effect.36 Skilled drummers strike a balance between strict adherence to metronomic time and related time scales or subdivisions versus allowing the time to ‘breathe’ to enhance the feel of the shared pocket. Sometimes these adjustments are significant enough to be considered displacements or grouping ‘dissonances’ in the meter.37

The dynamic balance among voices on the drum kit contributes to the pocket of the groove. Sometimes, for example, a groove may go from un-pocketed to pocketed by adjusting the balance of timekeeping in the hi-hat in relation to the kick and snare drum. By properly ‘mixing’, the entire drum kit part can ‘sit better’ in the groove. The ability to create and adjust such balance is acquired through a combination of experimentation and performance experience.38

These aspects occur in the social context of ensemble music making. However, in addition to the drummer’s ability to creatively utilize them towards aesthetic effect, the drummer’s social role in the band also impacts how freely the role of time steward is fulfilled. If the time is off, the rest of the band first blames the drummer, as the drummer is perceived as a de facto conductor who controls tempo and other time-related parameters. A drummer who is a new addition to a rhythm section may subordinate his or her timekeeping intuitions to another, more senior member of the rhythm section, usually the bass player. Indeed, drummers are commonly advised to follow the bass player during a group audition, a practice that demonstrates the physiological tendency to allow lower-sounding ensemble instruments to establish the temporal foundation of music.39 These and other considerations are abundantly clear in drummers’ verbal reports of their ensemble experiences.

Looking Forward in Teaching and Learning Drum Kit

Throughout this chapter, we have attempted to synthesize ideas from philosophy, psychology, pedagogy, and applied literature, as well as our own professional experience as musicians and educators. We have interrogated established norms for teaching and learning of the drums, and suggest a comprehensive and productive model of teaching and learning based on these norms while informed by the conceptual lens of creativity. In summary, we have substantiated the following points:

1. Curiosity, creativity, and musical expression are necessary attributes for pursuing a personal drum kit style, and they function interdependently and actively in a drummer’s interactions with other ensemble members.

2. Theories of curiosity, creativity, and musical expression are relevant to the ongoing work of drum kit learning, experimentation, and ensemble performance and recording.

3. Philosophical and psychological writings support the complex work of articulating a personal style of drum kit playing while conforming to well-known styles and genres, i.e. of striking an imperceptible balance between tradition and innovation, which comprises an important aesthetic dimension of musical experience.

4. Negotiating one’s individuality as a drummer is mediated by the belief systems of other group members regarding the traditional roles of drummers in groups.

Given these findings, the most effective drum kit instruction, while continuing to emphasize performance techniques and skills, should also incorporate expanded focus on creativity. We believe this can occur in the following ways:

1. Feel-based aspects of drumming technique should remain central to the instructional process.

2. Mentoring relationships between early and later-career drummers, which naturally includes transmission of generational knowledge in aural traditions, is essential.

3. Strategies helping students explore and develop the personality traits relevant to creative reasoning and execution are central to a comprehensive didactic approach to the drum kit.

The challenge of achieving a balance between tradition and innovation by drummers in ensemble practice and performance provides an opportunity for them to assimilate a repertoire that spans multiple decades of popular music history, and which recurs in contemporary popular music.40 We believe music philosophy, having evolved through the postmodern era, can still be quite useful to developing musicians, as they seek a meaningful core for guiding their aesthetic judgements in drum kit playing.

Introduction

Jazz music has long been understood as a generational practice, one where older musicians mentor, encourage, and teach younger, aspiring players.1 That tradition of tutelage is often evident in the long lineages of musicians who have graduated from the ensembles of noted bandleaders. Historical examples of such ensembles include those of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and most germane to this volume, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, an ensemble celebrated for its famous alumni as much as for its spirited drummer and leader.2

In this chapter, I consider this tradition as it relates to two specific drum kit players: Jack DeJohnette, a major figure in the history of jazz drumming and a bandleader recognized for his history of nurturing younger musicians, and Terri Lyne Carrington, a premiere figure in contemporary jazz drumming and a celebrated leader of ensembles that feature young, developing musicians.

Specific themes include: (a) the importance of mentors in the lives of the participants, (b) challenges of learning to play the drum kit, particular to the instrument itself, (c) the unique place and space of drummers, behind kits, on band stands, and in the roles of leader or leader/mentor, and (d) ‘something bigger than just the music’, the larger contexts of learning to play, of connecting to a community and lineage of jazz drummers.

The Participants

Although both participants are quite renowned, and full details of their extensive recording, performing, and education careers are readily available to readers elsewhere, in order to provide context for this chapter contribution, short profiles of each participant are in order. I will start with Jack DeJohnette, whom I have known for some 30 years, and who led me to Terri Lyne Carrington, and eventually to the ideas that informed this writing.

Jack DeJohnette, a name likely familiar to drum kit players reading this volume, has played with some of the most storied figures in jazz and improvised music. DeJohnette’s credits include recordings, performances, and long-time associations with Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Stan Getz, Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, Dave Holland, Joe Henderson, Freddy Hubbard, Betty Carter, and Pat Metheny among many others.

Jack’s creative drumming in jazz, avant-garde, fusion, and new age styles has been recognized by critics, associations, institutions, and peers so often as to preclude listing every honour in this chapter text. A quick summary of recognitions includes a Grammy Award, perennial inclusion in readers and critics polls published by each of the major US jazz magazines, Down Beat and Jazz Times, Hall of Fame status in the Modern Drummer Magazine readers poll, recognition with the French Grand Prix du Disc award, and induction into the Percussive Arts Society’s Hall of Fame.

The honour most relevant to this chapter is a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Fellowship. This award is the highest honour awarded by the US Federal Government in recognition of the life’s work and contributions of notable jazz musicians. The Jazz Master designation noted Jack DeJohnette’s remarkable career achievements, life-long contributions to jazz music as a cultural and artistic form, and his commitment to mentoring younger generations of aspiring jazz musicians.

Terri Lyne Carrington, one of the most highly regarded musicians of her generation, has been playing the drum kit since childhood, manifesting prodigious talent as early as ten years old. In a career that spans some 40 years, Terri Lyne Carrington has played drums, sang, and produced music for record, for television, and for marquis live events affording her opportunities to collaborate with the likes of Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, George Duke, Carlos Santana, John Scofield, David Sanborn, Stan Getz, Geri Allen, Esperanza Spalding, Christian McBride, and vocalists Cassandra Wilson, Dee Dee Bridgewater, and Dianne Reeves, among countless others. A three-time Grammy Award winner, Terri Lyne Carrington is the first female recipient of the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Jazz Album. In 2019, Carrington was awarded the Doris Duke Award in recognition of and in support of her outstanding record of achievements in jazz performance.

One hallmark of Terri Lyne Carrington’s work has been the ways in which she features young musicians in her ensembles, providing opportunities early in the careers of Ambrose Akinmusire, Tineka Postma, and Morgan Guerin, among many others. Accordingly, Carrington is an esteemed educator, lauded for her work at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, where she founded and, at the time of this writing, serves as Artistic Director for the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice,3 an organization that has mentoring young musicians as part of its stated mission.4

Finally, it is important for me to contextualize my own background so that readers might better understand the experiences and perspectives that have informed my analysis of the participants’ expressions. I am a drummer, composer, and music education researcher. In my research, I have considered improvisation education,5 popular music education,6 technology in music education,7 and music teaching and learning as it occurs outside of schools.8 I am also an educator, holding the position of full professor at the State University of New York Oneonta, where I teach music industry courses, beat production, and direct ensembles that perform experimental music and improvised rock.

Lastly, I have extensive experience working in the jazz recording industry, including tenures at notable labels such as CMP Records, ECM Records, and RCA Victor. More recently, I am a band leader and recording artist, leading the jazz fusion group Bright Dog Red, which records for the influential Philadelphia label, Ropeadope Records. The views of and interpretations of the participant expressions presented in this chapter reflect and have been informed by these various identities, experiences, and professional activities.

Method

Given the nature of what I sought to understand, the dynamic personal and professional relationships between two expert practitioners, the phenomenon of generational mentoring, and the role of mentoring in jazz music, I selected qualitative research methods. Qualitative inquiry afforded me the opportunity to interpret the themes explored in this chapter, as they emerged and as I engaged the participants in discussion about mentoring in jazz drumming, the drum kit itself, and our collective experiences learning and teaching the instrument.9

I conducted two stages of data collection, both based on a protocol developed for the Music Learning Profiles Project.10 For the first stage, I shared the twelve-question protocol with the participants and asked them to freely respond, either in writing or in spoken and recorded voice, individually and without discussing their answers. For the second stage, I interviewed both participants simultaneously, using the protocol to structure the interview. Although the protocol helped start the discussion, the participants’ responses drove the discussion,11 illuminating key themes, ideas, and expressions reflective of the participants’ understandings of their relationship, of mentoring in jazz and in drumming, and of the project itself.

After conducting both stages of data collection, I reviewed the transcripts of participant responses, expressions, and thoughts. That review process allowed me to code themes, concepts, and recurrent notions, in an emergent and evolving manner.12 As I came to understand the data, I simultaneously rethought the themes and points of focus. That iterative approach led me to the understandings, analyses, and conclusion offered in this chapter contribution.

Finally, after transcribing the data, I shared transcriptions, emerging themes, and the final draft of this chapter with Jack DeJohnette and Terri Lyne Carrington to ensure that the final work represented their perspectives, their participation, and the points they wished to communicate. The analyses, discussion, and conclusions reflect my understandings, responses to, and interpretations of Jack DeJohnette’s and Terri Lyne Carrington’s statements.13

Discussion

I have known Jack DeJohnette for some 30 years, first meeting him when I worked for the drum manufacturer Latin Percussion. A few years after working for Latin Percussion, I got to know Jack well during my time working for ECM Records, home to much of Mr. DeJohnette’s recorded output. To describe Jack as a friend would not suffice. He’s been a mentor, a figure of wise council, and a role model in drumming and in life. I am grateful to have gotten to know him in these ways, to have grown close to his family, and to learn so much from him over the years.

Some years ago, Jack introduced me to Terri Lyne Carrington with the aim of planning an educational endeavour, a summer camp, a school program, something that would bring the three of us together to, as Jack put it at the time, ‘to work with kids and the power of music’.14 That project did not come to fruition; however, I learned more about Jack’s relationship with Terri. Already very much aware of Terri Lyne Carrington’s professional accomplishments, I also learned more about her exemplary teaching and long history of mentoring younger musicians, something she shared in common with Jack DeJohnette.

Mentoring has a long history in the jazz tradition, one that has been explored at length in music education research15 and jazz history research.16 In the early to mid-twentieth century, jazz music was developed and learned by and among jazz musicians. Andrew Goodrich, who has written much about mentoring in the context of contemporary jazz education, explains:

Jazz musicians originally learned to play jazz in a variety of ways: listening to and transcribing recordings, listening to live performances, and asking questions of each other. From this aural and verbal communication with each other came the development of mentoring, or the social language of jazz. As jazz musicians hung out with each other, they shared ideas for learning that increased their knowledge of jazz music and elevated their level of musicianship. This type of conversation, both verbal and aural, occurred before, during, and after gigs. These conversations centered around how to learn. (emphasis added)17

In the United States, during the latter part of the twentieth century, jazz education programs became a staple among collegiate and university music departments, professional associations such as the International Association for Jazz Education formed, and music publishers began publishing jazz charts and method and instrumental technique books expressly for school jazz contexts.18

Although speaking in the early twenty-first century, some seventy years since jazz music first entered the academy, the participants in this study described learning in many of the same terms as those described by Andrew Goodrich and the others I have referenced. In describing their experiences with learning the drum kit, the participants kept returning to the following themes: (a) the importance of mentors in their lives and in the jazz tradition, (b) challenges of learning to play the drum kit, particular to the instrument itself, (c) the unique place and space of drummers, behind kits, on band stands, and in the role of leader or leader / mentor, and (d) ‘something bigger than just the music’, the larger contexts of learning to play, of connecting to a community and lineage of jazz drummers. The following sections explore those themes as they emerged in the responses of the participants.

The Importance of Mentors

Throughout our conversations, Jack DeJohnette repeatedly expressed gratitude that he was ‘fortunate enough to be around other musicians, players, and you know, a mentor that’ could teach and inspire him.19 DeJohnette explained his early musical life in his hometown: ‘I got guidance, what you’re calling mentoring, from Chicago musicians, let’s see, Von Freeman, who else, yeah, Muhal Richard Abrams was really good, a lot of others too’. As Jack recalled other Chicago area musicians, he noted some of the players he had only heard on recordings, viewing them as de facto mentors. Similarly, DeJohnette counted many of the musicians whom he had observed playing live or had worked with on bandstands as mentors:

You know, a lot of that guidance came from listening to musicians, recordings, going to hear people play, and then playing with Roscoe Mitchell, almost every day, free improvisation, drums and piano. Playing with Muhal [Richard Abrams], Joseph Jarman, a variety of music professionals that were just very helpful in my development, and inspired me to do my very best, and playing with musicians of, you know, the best quality, top quality, and playing also with some of the greatest jazz artists and musicians on the planet. That helped a lot. Jackie McLean was a great help for me, of course Coltrane, and, who else, Miles Davis, of course, Bill Evans, just to name a few.

Much of Jack’s drum kit learning, however, was self-directed. He started as a piano player, taking lessons, and playing that instrument with a combo of his own. The drummer in that combo left a drum kit at the DeJohnette household and between rehearsals, Jack would sit behind the kit:

So, I got started playing the drum kit when I had a combo and I had a drummer who was a part time drummer, so we used to rehearse in my house in Chicago, and he left his drum kit there. My uncle was a DJ so I had access to the latest jazz LPs and so, it took me about a month, I would go down in my basement, in a studio, and play with the LPs, jazz LPs and It took me about two weeks to get my coordination together and the other two weeks, I would actually play pretty decent. Drums came to me very naturally.

Mentoring also figured prominently in Terri Lyne’s biographical narrative. She explained, ‘drumming ran in the family. My grandfather was a drummer and my dad played sax and drums. So, the drums were there and the music was always playing in the house’.

Carrington’s father, Matt Carrington, introduced Terri to a slew of iconic jazz musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie and Clark Terry, among many others, affording her the opportunity to sit in and ‘learn while doing it’. Many of Matt Carrington’s associates became mentors for young Terri Lyne. She recalled the importance of those mentors during a particularly musical childhood, ‘learning from mentors is the most important way to get the needed inside information. You learn by default just by being around the right people’.

In addition to those de facto mentors, Carrington mentioned some of her teachers, each of whom transcended their role, going above and beyond teaching how to play the drum kit to becoming important life mentors, ‘my Dad was my first teacher, but I also studied with Keith Copeland and Alan Dawson, as well as Tony Tedesco and John Wooley’. Owing to her precocious talents, Terri Lyne began studying at the Berklee College of Music as early as ten years of age. As noted earlier in this chapter, Ms. Carrington is a well-regarded and innovative educator at her alma mater. During the interviews for this chapter, Mr. DeJohnette regularly remarked on Terri Lyne’s ‘amazing’ expertise in teaching drum kit at Berklee. Despite her commitment to and expertise in jazz education, Carrington described an extra ‘element’, unique to the mentor / mentee relationship, that often eludes institutionalized jazz education contexts:

And now we have institutionalized jazz education, so people are getting a lot of the things more quickly. But there’s still that element of apprenticeship in the art form, that element of needing to be apprenticed, and needing to be mentored to really get into the nuances of the music that you won’t necessarily get in jazz education.

Terri Lyne described the importance of Jack to her development as a drummer, musician, and ‘most importantly, as a human being’. Carrington has a nearly forty-year relationship with Jack DeJohnette, whom she identified as, ‘my biggest mentor … critical to my development’. She explained:

For me, Jack was definitely, and still is, that person who came to be so important on so many levels when I was 17 or 18. I remember being pretty close-minded about music, life, things in general, and I remember Jack saying, ‘we have to open you up,’ because I was really a jazz head, in a way, which was great to start, but there were all these other things about music and about life that I really needed to embrace. I moved to NY when I was 18 and I had some friends, people that were a little older than me, but nobody who took that much interest who could pass the important things on to me, other than my parents, or that I could go to if I needed advice or help. And, I think that for me this was crucial to my development and it also made me see how important it is for me to do the same thing. I know that in my own way, I’m trying to do the same for some other young people. And because I’m teaching, seeing so many young people, I can’t do that for everybody, but I do pick a few. And another thing I really learned from Jack is how to pick the ones you help. You know, it’s not something that you just give away. You can’t give a gift to somebody that doesn’t know what to do with it.

At this point, as Carrington and I began discussing the vast numbers of students we see each academic year, the conversation switched focus to the specific challenges posed by teaching and learning to play drum kits in jazz education.

Challenges of Learning to Play the Drum Kit

In discussing the ‘learn while doing it’ approach, the nature of the drum kit and the particular role of drummers became points of focus. The drum kit is essential to much of contemporary jazz and improvised music. Drummers are relied upon for time, support, and direction. While all instrumentalists must learn a fair amount before hitting the bandstand, the participants agreed that drummers had to contend with being more of a critical focus while learning on the bandstand. Terri Lyne summed up this challenge:

I don’t think you can go on stage and play without a certain amount of experience, but then you’re right, you have to get the experience. If the drummer’s horrible, then the band’s not great. You could have a mediocre bass player or soloist, but a good drummer, and the band still sounds and feels good, for the most part. So, there’s a lot of weight on the drummer for making a band sound good.

The participants then recalled the ways in which they dealt with this conundrum in their own lives. Some of their approaches are likely familiar to readers of this volume and echo those that have been documented in the literature: listening to recordings, watching more established drummers, asking questions, and transcribing parts. One approach, however, stood out.

Both participants recalled learning to think about time from listening to instrumentalists charged with phrasing, such as horn players, other frontline instrumentalists, or singers. Jack DeJohnette explained, ‘I listened to the melodies. Learning the melody can actually improve your time because you have to follow the phrasing, understand where things end up’. Terri Lyne Carrington concurred, ‘to this day, I listen to the horn soloists, the singers, sometimes more than I do the bass player. In fact, I don’t even really want to listen to the bass player so much, at least not as the start’.

Honing in on melodic instruments or singers, as a gauge to mark time, figured into the learning processes for both participants. Terri Lyne Carrington recalled taking this approach in her earliest days, while playing with records:

When I would play with records, and even today, I would listen to the phrasing and the rhythm of the horn, so if I’m playing with somebody who’s phrasing and time is impeccable, I’m playing with that and it makes me play different. So, it’s all kinds of elements coming together. When you’re playing with great records, you’re playing with great people that had great time, and that helps you to learn what to listen for. And if you’re playing along with great pianists, that comp in the right places, you know what it sounds like when somebody’s comping good.

These discussions led the participants to think about other approaches to learning that helped them develop on the drum kit prior to ‘learning by doing it’ on bandstands.