As one of the inventors of the twelve-tone technique and the first well-known composer of twelve-tone music, it makes eminent sense that Arnold Schoenberg would be understood by scholars and musicians as a traditionalist, in both the positive and negative senses. Much fruitful work has been done that shows ways in which Schoenberg carried over elements of classical and Romantic form and harmony into his twelve-tone compositions. To mention a few examples, one thinks of Richard Kurth’s illustrations of analogies to classical phrase types and tonic-dominant harmonic progressions in the opening of the Menuett from the Suite op. 25, or Ethan Haimo’s demonstration of how Schoenberg preserves the typical modulation schemes of sonata form using regions of twelve-tone rows in the opening movement of the Fourth Quartet op. 37 (Reference KurthKurth 1996: 105; Reference HaimoHaimo 2002: 225–6). On the other hand, it was Schoenberg’s obstinate tendency to hold on to classical and Romantic conventions of rhythm, form, and texture that caused Pierre Boulez the irritation he so vehemently expressed in ‘Schoenberg Is Dead’ (Reference BoulezBoulez 1952). But there is one way in which Schoenberg’s music preserved musical tradition that previous commentators and critics have hardly mentioned, perhaps the one with the most significance for long-range coherence in his twelve-tone music: what he called ‘musical idea’.

What exactly is a musical idea? Schoenberg’s explications of it in his writings were less than systematic, and, unfortunately, he never illustrated the concept with one of his own pieces, tonal, atonal, or twelve-tone, so there is room for disagreement on how to understand the term. The closest thing he provided to a textbook definition is found in the essay ‘New Music, Outmoded Music, Style and Idea’ (Reference Schoenberg, Black and SteinSchoenberg 1975c):

In its most common meaning, the term idea is used as a synonym for theme, melody, phrase or motive. I myself consider the totality of a piece as the idea: the idea which its creator wanted to present. But because of the lack of better terms I am forced to define the term idea in the following manner: Every tone which is added to a beginning tone makes the meaning of that tone doubtful. If for instance, G follows after C, the ear may not be sure whether this expresses C major or G major, or even F major or E minor, and the addition of other tones may or may not clarify this problem. In this manner there is produced a state of unrest, of imbalance which grows throughout most of the piece, and is enforced further by similar functions of the rhythm. The method by which balance is restored seems to me the real idea of the composition.

Note that here a musical idea is defined as a tonal piece: the initial problem which causes imbalance that grows through the course of the piece, and is eventually resolved at or near the end, is defined as an uncertainty regarding the tonal context of pitch classes C and G. And, not surprisingly, the literature that attempts to illustrate ‘musical idea’ through analysis, primarily by Schoenberg’s student Patricia Carpenter and her own students, deals almost exclusively with tonal music: Carpenter’s article ‘Grundgestalt as Tonal Function’, an insightful study of tonal problems, elaborations, and solutions in the first movement of Beethoven’s op. 57 piano sonata, is the first and one of the best examples of analytic work in this vein (Reference CarpenterCarpenter 1983).

Since the notions of ‘tonal context’ or ‘tonal problem’ are not possible in twelve-tone music, however, it is more difficult to grasp how a musical idea might serve as the framework for a twelve-tone piece. Since, in the twelve-tone style, no note should be considered any more central than any other, how can one perceive a note as foreign or distant from the centre? In my Schoenberg’s Twelve-Tone Music, I explored a number of ways in which pitch classes, intervals, and set classes can participate in narratives that involve creating an ideal state, setting another state in opposition to it, allowing that opposition to elaborate itself and branch out in various ways through the piece, and finally resolving it. Some of my analyses highlighted problems and elaborations that stem from the differences between a symmetrical pitch-class or interval pattern (presented or implied at the beginning) and various close or distant approximations of it. The symmetrical pattern is then reasserted at or near the end, and the approximations are connected to it in significant ways, as a solution. In other cases, the initial opposition and elaboration involve different partitions of different rows that create what seem like irreconcilable pitch-class or set-class elements. The solution will then consist of demonstrating how the conflicting partitions and their clashing consequences can be traced back to the original source row. Finally, a number of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone pieces, particularly later ones, include a struggle between various source row forms for primacy, which is resolved in favour of one of the potential sources at piece’s end.

The bulk of this chapter will be devoted to illustrating how musical idea is manifested in two of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone piano pieces: the Prelude from the Suite for Piano op. 25, written right at the beginning of his twelve-tone period in 1921–3, and the Piano Piece op. 33a, written in 1928–9 after Schoenberg had gained some facility at working with row pairs related by combinatoriality; ‘hexachordal inversional combinatoriality’ refers to a property between inversionally related row forms in which the corresponding hexachords have no notes in common and may be combined vertically into other orderings of the twelve-note universe. Both the Prelude and the Piano Piece express their musical idea by elaborating and resolving an opposition between a symmetrical ideal and close or distant approximations of it: the symmetrical pattern consists of pitch classes in the Prelude, and of pitch intervals in op. 33a. Given the limits of this chapter, I will not be able to give these pieces thorough section-by-section analyses, as I do in chapters 2 and 5 of Schoenberg’s Twelve-Tone Music, but instead will highlight how their problems are posed, elaborated, and resolved with a few snapshots.

Suite for Piano Op. 25, Prelude

The Prelude was the first piece by Schoenberg to be written in the twelve-tone style throughout, and a number of scholars have claimed that it does not use the row according to the conventional notion, as a single, consistent linear ordering of all twelve pitch classes. Ethan Haimo argues for what he calls a ‘tetrachordal polyphonic complex’, a division of the row into its three discrete tetrachords, which are then ordered freely between themselves (but usually preserve ordering within themselves) and often appear simultaneously (Reference HaimoHaimo 1990: 85–6). In what follows, I will sometimes count twelve-tone rows using ‘order positions’ (meaning first, second, third, etc., notes in the row), starting with 0 and ending with 11, and will highlight them in bold, so that tetrachords ordered within themselves but not between themselves might read: 4–5–6–7, 0–1–2–3, 8–9–10–11; or 8–9–10–11, 0–1–2–3, 4–5–6–7; or other such combinations. However, when these same twelve numbers (0–11) are not in bold, they represent the different pitches of the chromatic scale, regardless of octave. Therefore, C is represented as 0, C♯/D♭ as 1, D as 2, and so on. Hence, a C major triad could be represented as [047].

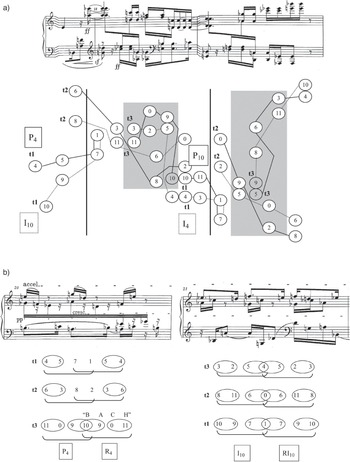

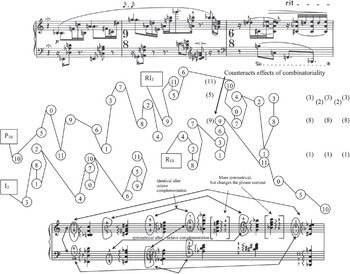

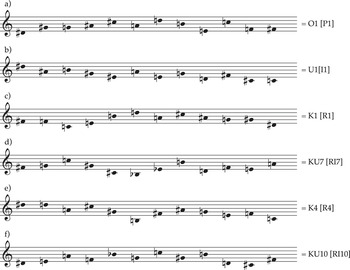

Part of Schoenberg’s set table for the piece, in the transcription provided by Reinhold Brinkmann for the collected edition of Schoenberg’s works, is reproduced in Figure 4.1, to which I have added a pitch-class map (Reference 396Schoenberg and BrinkmannSchoenberg 1975d: 77), while the autograph version of the table appears earlier in this volume as Figure 1.2. Haimo also reproduces this same set table, to provide evidence that Schoenberg had not yet conceived of the source row of the Prelude as a linearly ordered twelve-tone row – but I am interested in it for a completely different reason. Namely, it sets the discrete tetrachords of P4 (the prime form beginning on pitch class 4) and R4 (the retrograde of that same form) against one another, tetrachord by tetrachord, so that each line of the configuration creates a palindrome, and the whole also creates a symmetrical pitch-class structure. This structure then becomes the ‘ideal state’ in the piece, which is only approximated at the beginning (creating a problem), approached more closely but then completely abandoned for a different symmetrical structure in the middle (the elaboration of the problem), and finally realised in its perfect form near the end as a solution.

Figure 4.1 Part of Schoenberg’s set tables for the Suite, op. 25, with a pitch-class map

Figure 4.2 illustrates the opening of the piece, in which the ideal symmetrical shape is hinted at but not realised. The pitch-class map at the top of the example shows that when P4 and P10 are divided into discrete tetrachords and the corresponding tetrachords placed against one another, instead of the full collection of six contiguous dyad palindromes that P4 and R4 had created, only two are realised contiguously (<7, 1> – <1, 7> and <8, 2> – <2, 8>), while two are realised by a contiguous dyad and a non-contiguous one: <4, 5> – <5, 4> and <11, 10> – <10, 11>. In this way, the combination of P4 and P10 can only hint at the perfect symmetry that P4 and R4 would have created. Looking now at how these four palindromic dyads are projected in the score itself, it seems that Schoenberg has in fact attempted to highlight the available symmetries in a variety of ways: <7, 1> – <1, 7> through proximity and similar contours and articulations (accents), <8, 2> – <2, 8> through similar contours and articulations, <4, 5> – <5, 4> by means of similar dynamics and articulations, and finally <11, 10> – <10, 11> with similar articulations. These dyads account for much of the ‘balance’ that Kurth celebrates in this opening phrase’s ‘mosaic polyphony’ (Reference KurthKurth 1992: 190–6). But they still fall short of a completely symmetrical state, and that creates a problem – with its associated opportunities for elaboration and solution.

Figure 4.2 Schoenberg, Prelude op. 25, bb. 1–3

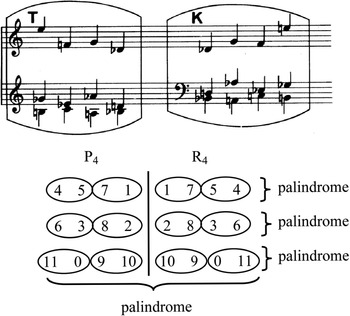

As the Prelude continues, it breaks up into subsections of the overall binary form’s A section (bb. 1–16a) that contain pairs and sometimes trios of row forms, in bb. 3b–5a, 5b–7a, 7b–9a, 9b–11a, and 11b–13a. These early sections fluctuate between pairings that yield fewer palindromic dyads and those that yield more, and also vary the number of potential two-note palindromes that are emphasised as audible motives within the texture. With b. 13, however, comes a passage that approximates the ideal more closely than anything heard before – but falls just short. It is shown in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Schoenberg, Prelude op. 25, b. 13

The lower right-hand corner of the example shows that I4 (the inversion of the prime form that starts on pitch class 4, around that pitch class) and RI4 (the retrograde of I4), the row pair featured in this passage, have the potential for six palindromic dyads because they are retrogrades of one another. But only three of these dyads are highlighted in the music itself (shaded in the example): <0, 6> – <6, 0>, <4, 3> – <3, 4>, and <1, 7> – <7, 1>, the last of which is realised by using an overlap to create a three-note horizontal mirror in the middle of the left-hand part. As the registrally sensitive pitch-class map in the lower left-hand corner and the marked score at the top of the example show, the other three potential dyad palindromes are all obscured in some way. <9, 8> and <11, 10> are given as verticals in the right hand of b. 13a and answered in the left hand of b. 13b by horizontal renditions of <10, 11> and <8, 9> that have parts of other dyads interleaved between them. And the second dyad in <2, 5> – <5, 2> is reversed within the tremolo figure (marked in the score, together with the three highlighted palindromes). This is not a solution quite yet, though it comes close.

Before finding its eventual solution, however, the Prelude wanders off into one more subsection that elaborates the problem more radically than anything heard before, the climactic passage near the beginning of the large A′ section at bb. 17b–19. It is portrayed, with its rather complex pitch-class map, in Figure 4.4a. As the pitch-class map shows (once it is untangled), there are a number of contiguous and non-contiguous dyad invariances between P4, I10, P10, and I4 that enable Schoenberg to assign various pitch pairs to more than one tetrachord, and, in addition, within both row pairs the second and third tetrachords routinely begin before the first and second finish, creating multiple overlaps. All four rows contain pitch classes 1 and 7 in order positions 2 and 3, and the first tetrachords of P4 and I10 link to one another on the downbeat of b. 18 through this invariance, as do the first tetrachords of P10 and I4 on the downbeat of b. 19. The non-contiguous dyad invariances begin with pitch classes 3 and 11, which appear in order position 5 of P4 and I10, and then swap places in order position 8 of the same rows. Schoenberg uses this to create a link (expressed as repeating notes Cb5 and Eb5 in the left hand of b. 18a) between the second and third tetrachords of P4 and I10. Other tetrachords that are linked in similar ways are the third tetrachords of P4 and I10 with the first tetrachords of P10 and I4, through {4, 10} (left hand of b. 18b), the second tetrachords of P4 and I10 with the second tetrachords of P10 and I4, through {0, 2} (right hand of bb. 18b–19a), and the second and third tetrachords of P10 and I4, through {5, 9} (left hand of b. 19a).

Figures 4.4a and b Schoenberg, Prelude op. 25, bb. 17b–21

The ensuing tangle of tetrachords and pitch classes with dual meanings, so much more complicated than the simple palindromic ideal of Figure 4.1, nevertheless creates its own symmetrical shape. It is highlighted within Figure 4.4a’s pitch-class map by the white circles inside the two shaded boxes: the verticals {3, 11}, {0, 2}, {6, 8}, and {5, 9} in b. 18, balanced by {5, 9}, {6, 8}, {0, 2}, and {3, 11} in b. 19. Kurth calls this the ‘gamma palindrome’ and highlights it as the most important and perceptible of three pitch palindromes in the passage, which do not synchronise with each other and together ‘motivate [a] drive toward some greater stability’ (the loud dynamics and registral extremes also mark this passage as unsettled) (Reference KurthKurth 1992: 200–6). But in the larger context of the subsections that have preceded it, we can also understand Kurth’s ‘gamma’ as the ultimate elaboration of the work’s problem, which follows all the approaches to and departures from complete horizontal symmetry of all twelve contiguous dyads in bb. 1–17 with a completely different approach to dyad symmetry involving non-contiguous verticals. It is almost as if the piece is saying: ‘I’ve tried to attain this piece’s ideal pitch-class palindrome for seventeen bars and failed. I’m going to try a completely different kind of palindrome.’

This ultimate elaboration of the problem, this high point of instability, is followed immediately by a passage that Kurth claims to bring ‘desired stability’ (Reference KurthKurth 1992: 205), and that I understand as the solution to the work’s problem: bb. 20–21, portrayed in Figure 4.4b. In each of these measures, since retrograde-related rows are again pushed up against one another, tetrachord by tetrachord, P4/R4 and I10/RI10, there is the potential for six dyad palindromes – the ideal shape. In b. 20, this potential is not fully realised, because <7, 1> and <8, 2> do not reverse themselves. But the other four dyads in the configuration not only reverse their pitch classes, but also their pitches, so that the music takes a large step closer to perfect symmetry. In b. 21, it gets all the way to perfect pitch-class symmetry, as the middle dyad pairs overlap in a single note, <5, 4, 5>, <6, 0, 6>, and <7, 1, 7>. The one detail preventing complete pitch symmetry is Schoenberg’s transposition of A and B♭ in the left hand at the end of the measure down one octave. The passage’s function as a solution following bb. 17–19’s ultimate elaboration is made clearer, I think, by Schoenberg’s drastic reduction in dynamics from ff to pp and narrowing of the register.

Piano Piece Op. 33a

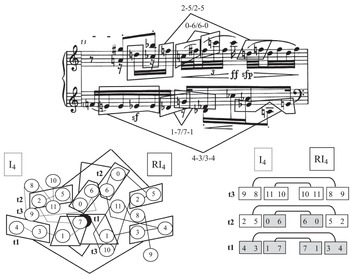

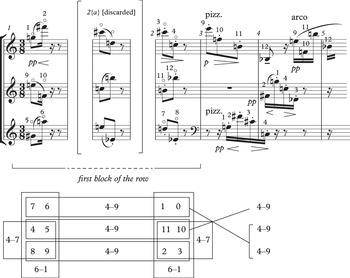

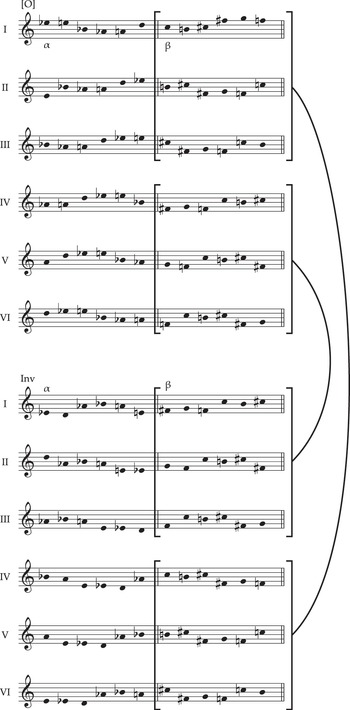

I have shown how, at the very beginning of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone period, he created a narrative spanning the op. 25 Prelude which manifests the ‘musical idea’, by suggesting a symmetrical pitch-class pattern, obscuring it further, and bringing it back into closer focus, then presenting an alternative symmetry that is nothing like the first in a climax, and, finally, realising the symmetry that was originally only suggested in a denouement. Five years later, after discovering and developing the hexachordal-combinatorial relationship between rows, he would return to the same sort of idea presentation in the op. 33a Piano Piece, expressing an old narrative in a new way. Op. 33a’s initial problem has to do with an incompatibility it presents between intervallic symmetry and row order, as shown in Figure 4.5a.

Figures 4.5a and b Schoenberg, Piano Piece op. 33a, bb. 1–9

As the example shows, the two principal (and combinatorial) rows of the piece, P10 and I3, are first presented out of order as a series of six discrete tetrachord sonorities (with the second row’s tetrachords in retrograde) in bb. 1–2, then both of them in linear order, but reversed with RI3 above R10, in bb. 3–5. The extensive reordering of notes in bb. 1–2 enables a pattern between the unordered pitch intervals of the six chords that is both horizontally and vertically symmetrical. (Schoenberg associated simultaneous horizontal and vertical symmetry with perfection in a number of his other pieces, and it even portrayed God’s perfection in Moses und Aron (cf. Reference BossBoss 2014: 332–41).) Counting intervals up from the bottom produces <1, 5, 5>, <4, 2, 3>, <6, 2, 3>, followed by a sequence of chords that reverses the previous elements and simultaneously flips them upside down: <3, 2, 6>, <3, 2, 4>, <5, 5, 1>. I call this the ‘palindromic ideal’ in Figure 4.5a. Once row order regains control in bb. 3–5, however, the pitch-interval symmetry of the opening measures disappears and is replaced by a less immediately audible symmetry, that caused by set classes: 4–23 (0257), 4–1 (0123), 4–10 (0235), 4–10, 4–1, 4–23. I call this the more abstract ‘echo’ of the ‘palindromic ideal’. The problem that op. 33a poses in its opening measures has to do with the seeming incompatibility of vertical and horizontal symmetry on the one hand and row order on the other: can both coexist? Or must row order necessarily weaken perfect intervallic symmetry?

Before answers to these questions are produced near the end of the piece, the first step in the realisation of the musical idea in op. 33a is progressively to obscure both the palindromic idea and the echo, similar to the way the Prelude op. 25 blurred its palindromic pitch-class pattern in its opening measures. Figure 4.5b shows how bb. 6–9 obfuscate the symmetries of the previous example through rhythmic displacement, as well as moving certain notes up or down by octave. (In the larger sonata form that spans op. 33a, bb. 6–9 constitute the first variation of bb. 1–5’s first theme.) In b. 6’s variation of the first chord of the palindromic ideal, C3, F3, and B♭3 rise an octave and B2 is delayed an eighth note, forming unordered pitch-interval stack <5, 5> followed by −13 (rather than <1, 5, 5>). The second chord delays its top three notes by an eighth, changing <4, 2, 3> to <+4, 2, 3>. And the rhythmic displacements and octave transfers carry on through the remaining four chords, changing what had been six horizontally and vertically symmetrical tetrachords into six conglomerations of chords and melodic intervals, all of which are unique and some of which are not even tetrachords (at the end of b. 7).

Bars 8–9 perform the same kind of obfuscation through rhythmic displacement of the set-class symmetrical ‘echo’ of bb. 3–5. To produce something like the original passage’s palindrome (4–23, 4–1, 4–10, 4–10, 4–1, 4–23), I had to group notes from different parts of the measure and from overlapping parts of the texture, creating a pitch-class segmentation that calls to mind the gerrymander – that is, manipulating the boundary line of a legislative district to favour a particular party – from partisan politics. Even with the gerrymanders, though, the sequence of set classes does not form a pure horizontal mirror: the initial pair (4–23 and 4–1) repeats. Through rhythmic and registral changes, but also through repeating parts of the row out of order, Schoenberg begins to obscure the perfect and imperfect symmetries of his opening.

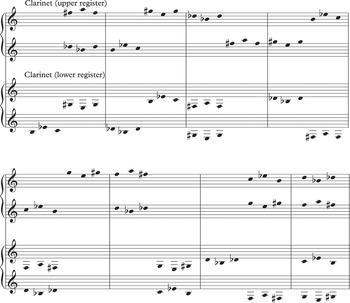

After a second variation of the P theme in bb. 10–13 that continues the process of obfuscation, the subsidiary theme enters in bb. 14–18, shown in Figure 4.6a. This passage and the one that immediately follows (Figure 4.6b) play an elaborating role within op. 33a’s ‘musical idea’ that is closely analogous to the part bb. 17–19 (Figure 4.4a) played in the Prelude – after the initial symmetry is progressively obscured, the S theme casts it aside and tries to attain symmetrical perfection in a completely different way (but still using the main pair of combinatorial rows, P10 and I3). Namely, the subsidiary theme abandons the intervallic and set-class symmetry of the opening measures in favour of horizontal pitch symmetry, particularly in the right hand of the piano. Bars 14 and 15 present the first hexachord of P10 as the complete palindrome <B♭4, F4, C4, B3, A3, F♯4, A3, B3, C4, F4, B♭4> (some pairs of notes are grouped vertically) followed by an incomplete version of the same. Bars 16–18 then supply the second hexachord of P10, split into two pitch palindromes: <D♭5, E♭4, G5, A♭4, G5, E♭4, D♭5> and <D5, E4, G5, A♭4, G5, E4, D5>. The left hand accompanies with the corresponding hexachords of I3 mostly in linear arrangements, forming aggregates between the hands in bb. 14–16a and 16b–18.

Figures 4.6a and b Schoenberg, Piano Piece op. 33a, bb. 14–22

This attempt to create horizontal pitch symmetry does a certain amount of violence to the ordered presentation of P10 in bb. 14–18. In the following closing section, shown in Figure 4.6b, the same incentive results in even more confusion with respect to the linearity of the row form. Not only are parts of rows taken forward and backward, but also notes of the complete linear presentations of R10, RI3, and the second hexachords of P10 and I3 are missing. Bars 19–20 set R10 in the right hand against RI3 in the left, using rhythms and textures reminiscent of first theme material (this abbreviation of thematic material is my main justification for calling this section ‘closing’). R10 progresses as far as order position 9, pitch class 0, and then that pitch class with its predecessors, <9, 6, 11, 0>, gets caught up in another pitch palindrome, <A6, F♯6, B5, C5, B5, F♯6, A6>, which repeats. Meanwhile, RI3 also only progresses as far as its order position 9, pitch class 1, which likewise takes part in a smaller pitch palindrome, <D3, C♯2, D3>. In both cases, it is the emergence of the pitch palindromes that causes the row to be incomplete. Likewise, the second hexachord of I3 that counterpoints with the second hexachord of P10 in bb. 20–23a, using the rhythms and textures of the S theme, stops one note short, not reaching all the way to pitch class 9, because it gets entangled in a small palindrome, <B♭3, F3, B2, F3, B♭3>. The C theme elaborates the problem within the Piano Piece’s musical idea by showing, repeatedly and forcefully, that the alternative way of making palindromes proposed by the S theme is not an acceptable substitute, because it destroys the integrity of the ordered row. The violence it does in the pitch-class realm is made much more tangible by the forte dynamic marking and ‘martellato’ of bb. 19–20.

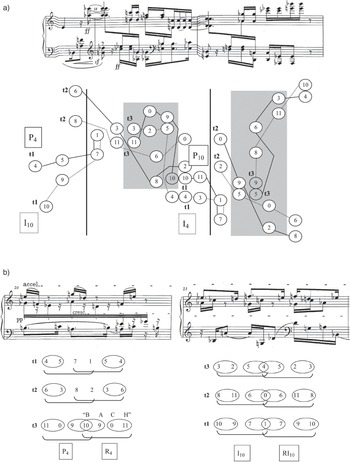

So now that it has become clear that pitch palindromes cannot reconcile the piece’s initial conflict between symmetry and row order, but in fact have the completely opposite effect, it remains for Schoenberg to show how those two properties can coexist within the same texture. After a fairly long development section (bb. 25–32a) where he gradually rebuilds the palindromic ideal of bb. 1–2, interval by interval, bb. 32b–34 presents the recapitulation of the P theme – portrayed in Figure 4.7. Instructors of undergraduate core theory who use op. 33a as an introduction to twelve-tone music will certainly recognise the right hand in bb. 32–33a as that place to which they send their students to find the source row of the piece in its pure, unadulterated form, presented without order changes, missing notes, or verticals to confuse the analytic process. RI3 follows it in bb. 33b–34, but with several verticals and a short palindrome involving the third discrete tetrachord in b. 34b. The left hand in this section accompanies with the combinatorial forms I3, followed by R10 – in order between the tetrachords, but with the order within the tetrachords compromised by verticals.

Figure 4.7 Schoenberg, Piano Piece op. 33a, bb. 32b–34

Still, these measures present one of their row forms in proper order, and the other three in something relatively close to proper order. It is remarkable, then, that at the same time they are able to preserve some (but not all) of the palindromic ideal, the horizontally and vertically symmetrical pattern, of bb. 1–2. At the bottom of Figure 4.7, the discrete tetrachords of P10 and RI3 in the right hand as well as I3 and R10 in the left are stacked vertically so as to preserve the register of each note, and unordered pitch intervals between the pitches are listed. The intervals of P10 and RI3 (from the bottom up) are: <1, 6, 7>, <5, 3, 6>, <4, 6, 5>, <8, 6, 7>, <5, 4, 6>, and <7, 6, 1> – different intervals from bb. 1–2, but preserving some of the same symmetries. Most salient is the inverted relationship between verticals 1 and 6, which replicates the outside chords of the palindromic ideal in a different form. But verticals 2 and 5 also share pitch intervals 5 and 6 in corresponding locations (not inverted), preserving some of their horizontal symmetry; as do verticals 3 and 5, which preserve interval 6 in the middle position and octave-complement the intervals on the outside: 4 and 5 become 8 and 7. Finally, there are also a few vertical symmetries between the hands, marked at the bottom of Figure 4.7 with circles and arrows.

This passage constitutes the solution to op. 33a’s problem, the demonstration that vertical and horizontal symmetry and row order can indeed coexist. It is certainly true that it could have done a more thorough job of mirroring its interval stacks in the right hand. The bracketed chords after verticals 4 and 5 at the bottom of Figure 4.7 show what those verticals would have looked like had Schoenberg created an exact horizontal and vertical palindrome like the one in bb. 1–2. It would indeed have been possible for the right hand to play through these bracketed verticals in the order prescribed by RI3, <A5, B4, F5, F♯4> and <B♭4, C6, G5, E5>, forming a perfect union of intervallic symmetry and row order. But that would have made the arch contour in the right hand less clear, obscuring an important feature that makes a connection between this passage and the opening measures.

Not every twelve-tone piece Schoenberg wrote expresses a complete musical idea – problem, elaborations, and solution – as the two examples I have discussed in this chapter do. Moses und Aron, because of its subject – Moses’s failed attempt to communicate God to his people – organises itself around an incomplete musical idea: an initial problem, representing the conflict between Moses’s words and Aron’s images, which continues to elaborate itself without ever coming to resolution (see Reference BossBoss 2014, 330–94). Other pieces with texts – for example ‘Tot’ from the Drei Lieder op. 48 – abstract a ‘basic image’ from the text and use that as an organising principle rather than an idea (Stephen Peles explains quite well how the image of a unitary entity with two opposite sides controls the partitions and intervallic and pitch-class patterns of that song) (Reference PelesPeles 2004). But, in general, the ‘musical idea’, adapted for use as an analytic framework, is an invaluable tool for understanding how Schoenberg’s music coheres and exactly how he carried on the tradition of his German and Austrian predecessors.

During his lifetime he was a leading member of the avant-garde and would have never felt himself to be anything else.

We remain incorrigible romantics!

If there is a single, enduring quality in Alban Berg’s serial works (c. 1925–35), it is his ability to use the twelve-tone method of composition as a form of exegesis for his personal, intellectual, and musical heritage in musical narratives suffused with apparent contradictions. From his first twelve-tone composition, the second version of his song ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’ (1925), to his last work, the Violin Concerto (1935), Berg grappled with efforts to establish his own identity as a modern composer while dealing with issues related to personal and artistic influences from individuals such as Wagner, Mahler, Wedekind, and Kraus, as well as the overbearing figure of Schoenberg. In contrast to his former teacher, who was openly averse to external influences, Berg embraced an array of individuals as ‘ideal identities’ (Reference SantosSantos 2014), to be played out in his creative process. In doing so, Berg combined what have been generally understood as antithetical ideas in an attempt to elevate his method of composition as an overarching system that brings together his modernistic aesthetics and the art of the past through textures in which twelve-tone serialism and tonality are interwoven.

Such an approach to composition was bound to be controversial from the very beginning, as serialism was supposed to be a logical antidote to the excesses of tonality as practised by the late Romantic composers. Because Berg’s approach to serialism embraced gestures of tonality, it also attracted criticism even from members of his own circle. In 1946, Schoenberg wrote an addendum to his essay ‘Composition with Twelve-Tones’, where he engaged in a blistering judgement of Berg’s approach:

I have to admit that Alban Berg, who was perhaps the least orthodox of us three – Webern, Berg and I – in his operas mixed pieces or parts of pieces of a distinctive tonality with those which were distinctively non-tonal. He explained this, apologetically, by contending that as an opera composer he could not, for reasons of dramatic expression and characterization, renounce the contrast furnished by a change from major to minor.

Not accepting Berg’s explanation, Schoenberg continued: ‘Though [Berg] was right as a composer, he was wrong theoretically’ (Reference Schoenberg and SteinSchoenberg 1975a: 245). It is difficult to assess Schoenberg’s sincerity when he considered Berg to be ‘right’ as a composer while mixing serialism with tonality, as Schoenberg’s main concern as a composer was to establish relational events based on the initial idea of a composition. A piece that starts with a twelve-tone series would logically develop configurations afforded by the series, and these configurations would not be tonal. His consistent position on this issue is well documented. Schoenberg’s statement puts forward, nevertheless, a conflict between the notion of the composer as composer versus the composer as theorist, and the implication that, because Berg used tonality for ‘dramatic expression’, he was less systematic in his compositional process. Such a view has helped perpetuate the notion that Berg was ‘more Romantic’ than the other members of his circle – a view that has slowly been challenged since the autograph sources preserved at the Austrian National Library were opened to scholars in 1981.

Compounding the problem discussed above is the pervasive concept of a ‘Second Viennese School’ with the figurehead of Schoenberg followed by his ostensibly faithful pupils (Reference Auner and SimmsAuner 1999). As a result, Schoenberg’s shadow remains a long one. As Taruskin puts it, Berg was ‘formerly a pupil – and still very much a disciple – of Schoenberg’ (Reference TaruskinTaruskin 2005a: 193; my emphasis). Taruskin is not alone in subjugating Berg to Schoenberg. Berg did it himself. While dedicating his opera Lulu to Schoenberg on 28 August 1934, Berg wrote:

Please accept it, not only as a product of years of work most devoutly consecrated to you, but also as an outward document: the whole world – the German world, too – is to recognise in the dedication that this German opera – like all my works – is indigenous to the realm of that most German music, which will bear your name for all eternity.

Such expression certainly contributed to cementing Schoenberg’s approach to twelve-tone composition as the standard for analyses, a point of departure and constant reference in the interpretation of Berg’s musical language. George Perle, who established one of the most groundbreaking frameworks for analysing Berg’s music, argues defensively that ‘Berg’s characteristic practice … significantly distinguishes his twelve-tone technique from Schoenberg’s and Webern’s’ (Reference 392PerlePerle 1989: 9). In his book Serialism, Whittall argues that ‘like his fellow Schoenberg pupil Anton Webern, Berg had followed the master into the brave new world of post-tonal and total chromaticism’ (Reference WhittallWhittall 2008: 65). While there is no denying Berg’s indebtedness to Schoenberg’s musical and intellectual mentoring in his early years, the extent to which Berg followed Schoenberg in his mature years is certainly debatable, especially after the success of his opera Wozzeck (1914–22). Moreover, Berg’s differences are evident in the ways in which his twelve-tone compositions do not fit – and surely were never meant to fit – Schoenberg’s model. Berg was keenly aware of his position and approached his method of composition as a means of establishing ‘something more genuinely Berg’ (Reference BergBerg 2014). Adorno was one of the first to recognise the unique qualities in Berg’s music and openly expressed his goal of separating him from the other members of the so-called Second Viennese School. In a parenthetical comment on a letter to Berg on 23 November 1925, he put it bluntly: ‘this prattling about the “Schoenberg pupil” must stop’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 28).

Another important feature in Berg’s music is his penchant for inscribing his works with a multiplicity of extra-musical narratives, especially programmatic and autobiographical references (Reference FlorosFloros 1994; Reference PerlePerle 2001). From Adorno’s early description of the Lyric Suite as a ‘latent opera’ to the numerous essays written about Berg’s so-called ‘secret programmes’ (Reference Jarman and PopleJarman 1997; Reference PerlePerle 2001), it is clear that these features are ingrained in his approach to the compositional process. By now, it is impossible to dissociate Berg’s compositional choices from the extra-musical significations.

Together, these features encode Berg’s music with apparent antinomies that prove to be challenging to any method of analysis. Hailey puts it best:

Contradiction and paradox are central ingredients to Berg’s persona and of his music. He was a man of open amicability and of many secrets; a faithful friend and an eager consumer of malicious gossip; a composer of fierce modernism who courted popular appeal. The elusive qualities of his character make it easy to be sucked into a vortex of eternal regress and self-absorption. Berg, the man, we follow at our own peril. Berg the composer, however, transformed the spinning vortex of his unknowable self into extraordinary music that reaches beyond the self toward a common understanding of the human condition.

While contradiction and paradox may seem problematic, they are the modus operandi in Berg’s compositional process and must be considered as such. Perhaps these are the features that resonated most with Adorno and may explain in part his championing and defence of Berg’s music throughout his life. For Adorno, as Morgan Rich has demonstrated, Berg’s approach to twelve-tone serialism corresponds to his working out the concept of negative dialectics – a concept usually associated with Adorno’s late thought – and the ways in which his reflections on twelve-tone music were integral to his philosophical work. In Adorno’s view, Rich observes, ‘the strict twelve-tone style stopped the dialectical process in music. Schoenberg’s “laws” stopped the work from making a way forward’ (Reference RichRich 2016: 81). As Adorno expressed it to Berg, ‘there is only a “negative” dodecaphony, being the utmost rational borderline case of dissolution of tonality (even when tonal elements appear within dodecaphony; for then they, as a construction, are coincidental in their tonality, being simply dictated by the row!)’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 71–2). Ultimately, the apparent contradictions in Berg’s music correspond to what Adorno terms a ‘category of reflection’ (Reference AdornoAdorno 2007: 144). While Geuss has argued that Berg was not interested in Adorno’s philosophical thought (Reference Geuss and PopleGeuss 1997: 38), the possibility that a two-way exchange existed between them, and that Adorno, like many others, may have influenced Berg as well is worth considering.

Theory and Practice

As I have suggested, one of the most pervasive problems in the various analytical studies of Berg’s music relates to the ways in which Berg handles serialism and tonality in his mature works. In one of the most comprehensive analysis of Berg’s music, while favouring cyclic constructions, Headlam adopts a provocative tone: ‘Berg’s later music … is not truly twelve-tone – except for the second version of the song ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’ – despite the presence of rows and characteristic twelve-tone techniques. It is also not the case that Berg “fused” twelve-tone techniques with tonality’ (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 195). Referring to the Bach chorale ‘Es ist genug’ in the Violin Concerto, for instance, Headlam argues that ‘its tonal language seamlessly emerges from and dissolves into the surrounding cyclically-based passages’ (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 199–200). Whittall, arguing that we cannot ignore the highly recognisable tonal passages in Berg’s music, suggests ‘the possibility that [Berg] liked the idea of using such dramatic oppositions in non-arbitrary but still potentially disorientating ways should not be rejected out of hand’ (Reference WhittallWhittall 2008: 74–5). Clearly, as Ashby has argued, ‘serialism has become more important and specific as a historiographical marker for us than it was as a compositional device for anyone in the Schoenberg circle’ (Reference AshbyAshby 2002: 399; emphasis in original). Indeed, it should not be forgotten that, when Berg started exploring serial techniques, there was no ‘theory’ of twelve-tone music, and Berg learned from an eclectic array of sources as were available to him. A set of autograph manuscripts held at the Austrian National Library, for example, demonstrates the lengths to which Berg went in analysing Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano op. 25. Of particular significance is the way in which Berg isolates the second tetrachord of the row [G♭, E♭, A♭, D] and labels it ‘tonika’ (ÖNB Musiksammlung F21 Berg 107/i, fol. 2 v), reordering the other elements so as to form a chromatic ordered set (F21 Berg 107/i, fol. 1). In another page, Berg experiments with cyclic formations, more closely associated with his own practice than with Schoenberg’s (F21 Berg 107/i, fols. 4 and 4 v).

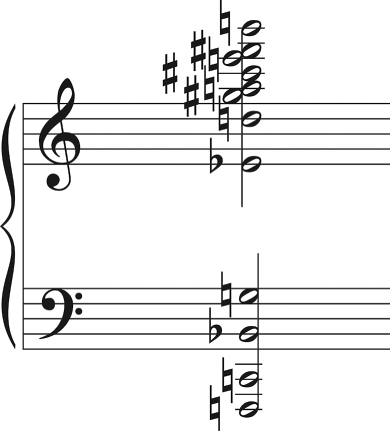

While revisiting the origins of Berg’s approach to twelve-tone composition, Ashby has compellingly demonstrated that Berg’s approach to serialism has close affinities with the discoveries of his student Fritz Klein, who, like Josef Matthias Hauer, may stake a claim to have generated a model of dodecaphony independent, at least to begin with, from Schoenberg’s (Reference AshbyAshby 1995). In a letter to Schoenberg on 13 July 1926 (located in Box 29, Folder 11, Arnold Schoenberg Correspondence and Other Papers, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington DC), while explaining his conception and use of the row in the Lyric Suite, which is the same one used in ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’, Berg was remarkably upfront about his indebtedness to Klein, particularly his borrowing the all-interval set (Figure 5.1) and the ‘Mutterakkord’, an all-interval twelve-tone chord (Figure 5.2) (see Reference Berg, Schoenberg, Brand, Hailey and HarrisBerg and Schoenberg 1987: 349–51; Reference BergBerg 2014: 203). For Berg, the axis of symmetry and the potential tonal references within the row were particularly attractive, even if they restricted the number of possible transpositions of the series (Figure 5.3). Of significance is Berg’s concern with the hexachordal content of the series and its potential for generating cyclic structures and invariant segments, which became defining traits in his musical language.

Figure 5.1 Berg’s illustration of the row set in the Lyric Suite, borrowed from F. H. Klein (Reference BergBerg 2014: 203)

Figure 5.2 Berg’s illustration of the all-notes and all-intervals chord

Figure 5.3 Berg’s illustration of axis of rotation generating the C major and G♭ chords and scales

While Berg’s use of Klein’s all-interval set and the all-interval twelve-tone chord are the most visible markers of his influence, it was perhaps Klein’s aesthetics that provided the intellectual foundation for Berg’s approach to his later compositions. Consider Klein’s statement about the results of what he called Musikstatistik [statistics of music]: ‘Since in my statistics of music all chords, from the simple triad to the complex Mutterakkord, are equal citizens in a realm of tones (the only fair estimation!), their consequences, namely tonality and extonality, are also to be considered equal manners of expression’ (quoted in Reference AshbyAshby 1995: 72–3). This comment seems to neutralise the notion of a conflict between tonality and atonality, even suggesting a lineage between the ‘simple triad’ and the all-interval twelve-tone chord. While Berg had explored some proto-serial features in his music before 1925 (Reference 392PerlePerle 1989: 1–6; Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 194–216), his earliest attempt at the twelve-tone method of composition was his second setting of Theodor Storm’s poem ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’. The first setting, composed in C major in 1907, was dedicated to Helene Nahowsky, his future wife; the second setting was dedicated to Hanna Fuchs, after a liaison that started in 1925 (Reference Floros, Berg and FuchsFloros, Berg, and Fuchs 2008: 54). The two pieces were originally published side by side in the periodical Die Musik in 1930 and included a dedicatory note to Emil Hertzka, in celebration of Universal Edition’s twenty-fifth anniversary, in which Berg describes the works as representing the progression of music in a quarter of a century, from tonality to twelve-tone serialism (Reference ReichReich 1930). Together, the two versions capture Berg’s teleological perspective on twelve-tone serialism, from interwoven traits of tonality latent in the formation of the series to the use of musical gestures as expressions of his autobiographical impulses. Berg’s motive for publishing the two versions side by side appears to be both an affirmation of Klein’s aesthetics and a justification for his own musical language.

Berg’s extraordinary explanation of his method advances some of the theoretical precepts that underlie both Perle’s and Headlam’s approach to analysis of his music but, more importantly, positions him, to borrow Allan Janik’s concept, as a ‘critical modernist’ (Reference JanikJanik 2001: 15–36). Although Janik applies this concept to Schoenberg, it is no less applicable to Berg, as critical modernists found it necessary to become cultural critics in order to defend the principles of logic behind musical composition and appreciation and to confront the art of the past and present as major intellectual figures had done at the time. As Born argues, such a theoretical impulse, at the onset of twelve-tone serialism, was also a defining trait of German modernism (Reference BornBorn 1995: 42). Indeed, as Hall has demonstrated, Berg’s deliberately explanatory attitude towards his compositional process and musical choices is illustrated in his numerous annotations throughout the autograph manuscripts (Reference HallHall 1997). When Adorno entitled his book Alban Berg: The Master of the Smallest Link, he had a point (Reference AdornoAdorno 1991), for it is now clear that everything in Berg’s music is set with deliberate calculation, even to the smallest detail. In his Sound Figures, Adorno goes further, claiming: ‘That means that there is not a single movement, no section, no theme, no period, no motive, nor even a single note that fails to fulfill its wholly unambiguous and unmistakable formal meaning even in the most complex contexts’ (Reference AdornoAdorno 1999a: 75–6).

The Hermeneutical Impulse

If Berg’s attention to the smallest details in the composition – and, I would add, an architectonic control over the large-scale formal structures – granted him the title of ‘master of the smallest link’, then the composition of the Violin Concerto made him the master of contradictions. The context of the composition is important. Composed at a moment of great distress in the composer’s life, when he found himself in poor health and felt rejected by his own Vienna after the rise of the National Socialist Party – performances of his work had been all but banned in the Germanic world – he felt compelled to stop working on his opera Lulu and accept the commission for the concerto from the American violinist Louis Krasner. The sum of US$1,500.00 would have been a welcome relief for his financial stress. This commission also carried the promise of future performances by the well-known virtuoso as well as the possibility for Berg to validate his own compositional techniques, particularly the juxtaposition of tonality and twelve-tone serialism.

As is well known, this work is fraught with extra-musical associations. Chief among them is the dedication to Manon Gropius, the daughter of Alma Mahler and Walter Gropius, who died in April 1935. Because of Berg’s insertion of the chorale ‘Es ist genug’ from Bach’s Cantata BWV 60 and the dedication of the concerto to ‘the memory of an angel’, the work has been interpreted as a sort of requiem, as well as a premonition of Berg’s own death, which occurred on 24 December 1935 (Reference Pople and PoplePople 1997: 224).

Since the discovery of the so-called ‘secret programmes’ in Berg’s mature works, however, it is also clear that he inscribed the concerto with autobiographical narratives, connecting his present and past experiences. As Douglas Jarman has persuasively demonstrated, the concerto contains a secret programme related to Berg’s affair with Hanna Fuchs, which had started in 1925 and presumably continued up to 1935 (Reference Jarman and PopleJarman 1997; Reference Floros, Berg and FuchsFloros, Berg, and Fuchs 2008). And much as he had done in most of his twelve-tone works from the Lyric Suite to Lulu, Berg encoded both the formal and serial structures of the concerto with elements recalling and retelling that affair. In addition, as if nostalgically referring to his past experiences, Berg included a quotation from a Carinthian folk song apparently related to his past affair with Marie Scheuchl, a maid at his family estate, with whom he had a child at the beginning of the century (Reference PoplePople 1991: 34). These features alone reaffirm Berg’s compulsion to include autobiographical inscriptions in his works. More recently, Jarman has also discussed Berg’s potential overture to the National Socialists, by incorporating the motto ‘Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei’ (‘Fresh, Devout, Happy, Free’) as descriptors of the different sections in the Violin Concerto; he also inscribed its acrostic formed by the letters ‘FFFF’ in a manuscript for the concerto. As Jarman argues, the presence of a symbol with a close relation to German Nationalism in the sketches is deeply problematic, especially after the Nazi electoral success in 1933 and their subsequent attempt to overthrow the Austrian government in July of 1934. Whether Berg used ‘FFFF’ as a symbol of resistance, as Jarman has suggested (Reference JarmanJarman 2017), or as a ‘calculated’, opportunistic ‘rapprochement’ to the Nazi Party, as Walton has argued (Reference WaltonWalton 2014: 75), its inscription in the concerto points to a network of contradictions with different layers of meaning that defies any single interpretation.

Between the private inscriptions and public messages in the Violin Concerto, it is the highly recognisable chorale ‘Es ist genug’, presented as an instrumental reinterpretation of the original message of redemption and transcendence, that keeps inviting interpretations, because it juxtaposes the musical language of the past and present, while representing the most powerful of human experiences: fear, loss, and hope. In its original context, as Eric Chafe has demonstrated, ‘O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort’, BWV 60 occupies a special place amongst Bach’s cantatas because of its message of redemption in death, but also because of its intricate, if not unique, tonal allegory (Reference ChafeChafe 2000: 220–40). Composed for the twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity, this cantata presents a dialogue between two of the most extreme, and perhaps most important, human feelings embodied in the voices of ‘Fear’ and ‘Hope’ in the first three movements. Following the hermeneutics of salvation, the conflict between Fear and Hope can only be resolved through acceptance of death in Christ, whose voice in the fourth movement (‘Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herrn sterben, von nun an’) marks the shift towards the believer’s acceptance of death and life in eternity. The final movement, ‘Es ist genug’, depicts the new consciousness of the believer, who, now with his hope restored, is ready to leave everything behind and enter ‘heaven’s house’ (‘Himmelshaus’). The original text of the chorale, written by Franz Joaquim Burmeister (1633–72) and set to music by Johann Rudolph Ahle (1625–73), reads:

In light of the conflict between Hope and Fear in the initial movements, the concluding chorale characterises, in Chafe’s words, ‘the return of the believer’s viewpoint to the world below as one that has been transformed by that vision into a new sense of peace and security’ (Reference ChafeChafe 2000: 238).

While Berg described his borrowing from ‘Es ist genug’ only briefly in a letter to Schoenberg (Reference Berg, Schoenberg, Brand, Hailey and HarrisBerg and Schoenberg 1987: 466), where he indicated the relationship between the whole-tone tetrachord of the opening melody [A, B, C♯, D♯] and the last four tones of the series (transposed, of course), he must have been aware of the message of the work as a whole. In fact, the setting of the chorale in the concerto, with the alternation between the solo violin and the clarinet ensemble (Part ii, bb. 136–54), seems to reinscribe the conflict between Fear and Hope, and the new ‘consciousness’ of the believer at the end. Berg even provides the original text underlying the orchestration of the chorale.

But even here, Berg includes contradictory elements. As Walton has observed, Berg adds expressive instructions in the score that change the eschatological message of this passage in significant ways. The clarinets, whose sound emulates an organ, are instructed to play ‘Poco più mosso, ma religioso’ whereas the solo violin, portraying the inner conflicts of the individual, undergoes a shift from ‘deciso’, ‘doloroso’, and ‘dolce’, at the beginning, to ‘risoluto’ in the middle section, and finally to ‘molto espr[essivo] e amoroso’ at the end. With these instructions, Berg effectively transforms the dialogue between Fear and Hope into expressions of spiritual and sensual love.

In effect, Berg secularised the cantata just as Oskar Kokoschka had done with a series of eleven lithographs entitled O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort based on Bach’s Cantata BWV 60 (1914) (Reference Hüneke, Heinemann and HinrichsenHüneke 2000: 388; cf. Reference KokoschkaKokoschka 1984: 39). In the sequence of illustrations, the figures of Fear and Hope are replaced with images of Kokoschka and Alma Mahler, with whom he had a relationship around that time (Reference WeidingerWeidinger 1996: 70–1). The series is therefore an allegory of life experience. As Joseph Paul Hodin points out, in Kokoschka’s O Ewigkeit, ‘art and existence are two contradictory worlds closely linked nevertheless by the mediation of man, whose condition vacillates unceasingly between being, becoming, and fulfilment’ (Reference HodinHodin 1966: 131). Ultimately, the series represents a journey of self-knowledge. In Kokoschka’s words: ‘The knowledge that comes from personal experience has an inner force. That experience which releases man from the bondage of transient existence brings the moment of eternal truth comparable to an act of birth. It is the expression of this inner truth which is socially valuable’ (quoted in Reference HodinHodin 1966: 143). Arguably, it is this journey of self-knowledge through mediation of personal experience in art that proved attractive to Berg.

And Berg would not have missed an opportunity to meditate on matters of suffering and transcendence in the second half of the concerto, which begins with a twelve-tone chord that leads to the presentation of the chorale and the set of variations that follows. This section also allowed Berg to convey not only his musical aesthetics, one that embraces serialism and tonality as equals, but also what he considered to be his musical heritage. Of particular significance is the transition to the final section of the Concerto, the ‘Höhepunkt’ of the Allegro (bb. 125–35), which functions as a bridge to the chorale. As Headlam has observed, this section is formed by a ‘monumental combination of pitch and rhythmic cycles’ where Berg lays out eighteen chords, whose top notes comprise eleven pitches, which is complemented by the F held as a pedal in the bass (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 372). In this transition, the solo violin performs seven trichords [024] transposed cyclically at a perfect fourth while unfolding the melody of the chorale [0246]. This passage leads to the initial statement of the Bach chorale and the beginning of the Adagio section (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Pitch reduction of Berg’s Violin Concerto, Part ii, bb. 125–37; after Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Musiksammlung F21 Berg 27, fols. 20 v–21 r

More important, however, is the narrative this passage conveys. In the programme notes Berg provided to Willi Reich, he described the dramatic aspects of the concerto and the role of the solo violin in the following terms: ‘Groans and strident cries for help are heard in the orchestra, choked off by the suffocating rhythmic pressure of destruction. Finally: over a long pedal point – gradual collapse’ (Reference ReichReich 1974: 179). The solo violin unfolding the whole-tone tetrachord that opens the chorale suggests an answer to the cries for help and the important role the solo violin plays in the narrative of salvation.

Indeed, Berg makes clear that in the variations that follow the entrance of the chorale, ‘the soloist with a visible gesture, takes over the leadership of the whole body of violins and violas; gradually they all join in with his melody and rise to a mighty climax before separating back into their own parts’ (quoted in Reference ReichReich 1974: 179). Starting at bar 170, the soloist is gradually joined by the strings until the concerto reaches its climax (the ‘Höhepunkt’) in bar 186 of the Adagio. At the moment of the climax, the solo violin is indistinguishable from the rest of the strings. Then, from bar 193 to 196, the reverse occurs. The strings drop one by one until the solo violin emerges again with the series P9 (7–11 then 0–6) above statements of ‘Es ist genug’ in the violoncellos.

While Pople has related these passages to autobiographical narratives (Reference PoplePople 1991: 37), I suggest that it is a musical rendering of Schopenhauer’s concept of compassion (Mitleid), much as Wagner had done in his opera Parsifal. An excerpt from The Basis of Morality will provide a way of framing the musical narrative of the passages discussed above, particularly with regard to the relational aspect of suffering:

I suffer directly with him [Ich … geradezu mit leide], I feel his woe as I ordinarily feel only my own; and, likewise, I directly desire his weal in the same way I otherwise desire only my own. But this requires that I am in some way identified with him, in other words, that this entire difference between me and everyone else, which is the very basis of my egoism, is eliminated, to a certain extent at least.

The transition to the chorale suggests a complete identification between solo violin and the other strings and a sudden loss of self-identification, realising the ‘pain’ reflected in the orchestra and feeling it as its own, hence the unfolding of the whole-tone tetrachord in anticipation of the chorale. Even here, Berg meditates on his musical heritage, especially his indebtedness to Wagner’s Parsifal. In many respects, the passages above are a sort of instrumental resignification of the transformation that Parsifal undergoes as he resists Kundry’s temptation in Act Two of the opera and feels Amfortas’s pain as his own, after which he realises that only through his leadership would the order of the Knights of the Grail be redeemed. In Berg’s Violin Concerto, the soloist takes the leadership by completely identifying with the string section of the orchestra. In the ‘Höhepunkt’ all differences are eliminated, and the path to ‘redemption’ is reinforced by the variations on ‘Es ist genug’. As Nicholas Baragwanath has argued, Berg’s fascination with Parsifal was instrumental in his understanding of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony and may have been even more instrumental in the ways he conceived symmetries in his post-tonal music (Reference BaragwanathBaragwanath 2004; Reference BaragwanathBaragwanath 1999). Berg also must have understood the narrative of redemption in the opera, which informed the way he wanted the solo violin to ‘act’ in the musical narrative of redemption.

While the Violin Concerto continues to reveal extra-musical meanings and acquire new ones, the sincerity of Berg’s public dedication to Manon should not be easily dismissed (Reference WaltonWalton 2014: 85). If anything, the dedication is an indication of the close relationship between the Bergs and Alma Mahler. Writing to express her condolences to Alma Mahler after the loss of her daughter, Helene Berg made a profound statement – one that captures Berg’s own sentiments towards Alma Mahler and her daughter: ‘Mutzi was not only your child – She was also mine’ (quoted in Reference StephanStephan 1988: 36). This comment reflects not only a strong empathy but also the philosophical concept of compassion (Mitleid) that underlies the narrative of suffering and transcendence of the concerto.

The apparent contradictions, if not the eclectic nature of Berg’s music, his malleable treatment of the series, and the intersections of serialism and tonality in his mature musical language continue to cause uneasiness, especially because his music does not fit any stable analytical models available to us. Headlam’s denial ‘that Berg “fused” twelve-tone techniques with tonality’ (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 195), Pople’s notion of a ‘synthesis’ of ‘various aspects of his musical world’ (Reference Pople and PoplePople 1997: 220), Ashby’s suggestion that Berg’s use of tonality in his twelve-tone works is ‘performative’ (Reference AshbyAshby 2002: 386), and Walton’s suggestion that Berg was a calculating, opportunistic individual and that aspects of his music were possibly insincere seem to confirm the inherent ambiguity in all aspects of Berg’s mature work. Whittall provides a possible way forward, arguing that ‘Berg provided incontrovertible evidence that the “mechanics” of twelve-tone technique need not inhibit the kind of intense and personal musical expression that maintained recognizable and positive links with the expressive gestures of pre-serial composition’ (Reference WhittallWhittall 2008: 84). It is arguable, as Whittall has suggested, whether Berg saw what we perceive as contradictions to be incongruous at all, in which case the problem would be ours, depending on our set of expectations and whether we are willing to overlook aspects of Berg’s music or biography.

Entering into Anton Webern’s twelve-tone music and its complex reception history is like entering into combat with the Hydra: cleave off one head of the Webern myth, and two more grow in its place, often swinging at you from opposite directions. Understandings of late Webern range widely, from that of an intrepid pioneer who, invigorated by his amicable rivalry with his former teacher Arnold Schoenberg, like the ‘Sphinx’ paved the way for the post-war avant-garde (Reference Stravinsky and CraftStravinsky and Craft 1959: 79), to a staunch preserver and guardian of the Austro-German musical tradition committed to pouring ‘new’ music into ‘old’ forms (see Reference BaileyBailey 1991); from an abstractionist with affinities with the cubism familiar from the paintings of Paul Klee (see Reference PerloffPerloff 1983), to a composer deeply inspired by the programmatic landscape tropes evoked in so many of the poems that he chose to set to music (see Reference JohnsonJohnson 1998 and Reference Johnson1999); from a frigid and elitist rationalist looking through the falseness of Romantic subjectivity (see Reference EimertEimert 1955: 37), preoccupied by ‘logic’, ‘order’, and ‘comprehensibility’ (see Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963), to a relentless ‘expressionist’ (see Reference QuickQuick 2011; Reference CookCook 2017) and ‘middle-brow modernist’ (see Reference MillerMiller 2020), with a heightened concern for the sensuous, ephemeral, ineffable qualities of music as sound and for whom reportedly ‘knowledge of [the] serial implications was not required for a full appreciation of [his] music’ (Reference StadlenStadlen 1958: 16); or, from a fairly apolitical citizen, to someone who forsook his support for the social-democratic movement as conductor of the Labour Symphony Concerts to become ‘an unashamed Hitler enthusiast’ (Reference RossRoss 2008: 323).

So how, then, to face the Hydra of mythologies surrounding Webern’s twelve-tone work? Taking the view that, as the polemical clamour in the halls of Darmstadt and beyond has long faded away, it is otiose to keep chopping heads in an attempt to kill off the Hydra once and for all, in this chapter I wish to lay down the sword and take a step back from the embattled scenes of the past in search of a broader vantage point. Bringing biographical insights into dialogue with analytical, philological and philosophical perspectives, this chapter argues that the crux in understanding late Webern lies in understanding that the competing, often contradictory images of the composer that have emerged pose no real contradictions after all. Instead, in the same way that the Hydra’s separate heads are essentially connected entities, these different images are best understood as mediated with one another on a deeper level, representing different aspects of one and the same all-pervasive aesthetic concern: musical lyricism.

A critical shibboleth in Webern scholarship, the category of the lyric is notoriously difficult to define. Cutting across different musical styles and genres, the lyric permeates all levels of Webern’s compositional thinking, posing considerable methodological and interpretative challenges. That said, these challenges can be reframed as heuristic opportunities and a chance to rethink the very essence of Webern’s musical imagination. As Reference AdornoTheodor W. Adorno (1999b: 93) once succinctly noted: ‘Webern never departed from [the] idea [of absolute lyricism], whether consciously or not’. In this chapter, I seek to explore, in a perhaps appropriately Webernian manner of ‘six aphorisms’, how the concept of the lyric can be understood to operate in the context of Webern’s twelve-tone music. My aim is thus not to provide a systematic overview of Webern’s late repertoire, nor do I wish to put forward any interpretations of individual works. Instead, I seek to bring into focus and trace out some of the discursive levels of the lyric as a category that arguably, indeed, strikes right at the heart of the Hydra.

Lyricism as Aesthetic Self-Identity

I wish to begin with a rather curious fact: although it seems uncontroversial to regard Webern as a genuine musical lyricist – Adornians might be inclined even to say the most important musical lyricist after Franz Schubert – interestingly Webern only began to brand himself publicly as such when Schoenberg had disclosed to the members of his circle the method of twelve-tone composition in the early 1920s (see Reference HamaoHamao 2011). That Webern would forge a public identity as a musical lyricist while simultaneously developing a new identity as a twelve-tone composer is not a purely historical contingency. At the time Webern started to experiment with Schoenberg’s new method (see Reference ShrefflerShreffler 1994: 285), he was preparing many of his earlier works for publication, following his signing with Universal Edition in 1921, including the Six Bagatelles for string quartet (to become op. 9). The score appeared in print in the summer of 1924, accompanied by an evocative and often cited preface by Schoenberg. In it, Schoenberg, pre-empting potential reservations against the bagatelles’ extreme brevity, asserted that their aphoristic nature is the result of an attempt to ‘express a novel in a single gesture, joy in a single breath’, before concluding that ‘such concentration can only be present in proportion to the absence of self-indulgence’. Built into these lines is an emphatic claim. In juxtaposing the brevity of Webern’s ‘poems’ with the lengths of ‘novels’ (all quotes cited after Reference MoldenhauerMoldenhauer 1978: 193), Schoenberg advocated for an understanding of the bagatelles as valid contributions to the formation of the musical aphorism as a genre in its own right (see Reference ObertObert 2008).

Schoenberg’s preface, albeit itself somewhat elusive and not devoid of inconsistencies (see Reference Schmusch and ObertSchmusch 2012), may have made some impression on the members of the Schoenberg circle, especially on Adorno. In 1926, the year after he had joined the circle as a private student of Alban Berg and Eduard Steuermann, Adorno published a review essay on the premiere of the Five Pieces for Orchestra op. 10, conducted by Webern himself on 22 June in Zurich, which – with explicit reference to Schoenberg’s preface – identified the concern for ‘absolute lyricism’ as the linchpin of Webern’s aesthetic (Reference Adorno, Tiedemann and SchultzAdorno 1984: 513). Adorno’s essay, initially projected as a ‘theory of the miniature’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 35), can thus be read as an attempt to reinforce the interpretative vision proffered in Schoenberg’s preface and to put it on sturdy philosophical legs.

Yet despite this intellectual kinship, Adorno was quite anxious about how Webern and Schoenberg might respond to his essay. This was for a good reason, as glimpses into his correspondence with Berg reveal. Well before the premiere took place, on 25 December 1925, Adorno had shared with Berg that he was keen to ‘measure the tragic depth of his [Webern’s] [aesthetic] position’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 35), which he was later to locate in his essay in Webern’s tendency to contract the dialectical principle into the semblance of immediate expression (Reference Adorno, Tiedemann and SchultzAdorno 1984). (It is quite conceivable that Adorno is here taking his cue from G. W. F. Hegel, who in his Lectures on Aesthetics (Reference Hegel1975: 1133–4, emphasis in the original) discussed the concept of ‘concentration’ as the ‘principle’ for the lyric, admonishing that ‘between an almost dumb conciseness and the eloquent clarity of an idea that has been fully worked out, there remains open to the lyric poet the greatest wealth of steps and nuances’.) When he did not receive any feedback from Berg on this specific matter, Adorno increasingly feared that his critical take on Webern may have led to some serious irritations, possibly alienations between him and the Schoenberg circle. It was thus ‘particularly gratifying’ to him to eventually see that Berg, ever generous in his judgements and support, had only kind and approving things to say about the essay upon its publication. Reading between the lines of Berg’s response indicates, however, that Webern and Schoenberg may have been less enthusiastic. Alluding to past frictions and tensions, Berg warned Adorno that ‘a few words and turns of phrase … will once more cause offence’. In his reply, aiming to smooth potentially agitated waters, Adorno assured Berg that he had ‘increasingly warmed to his [Webern’s] works’ over the course of time and that ‘some of them … truly contain some of the purest, most beautiful lyricism that there is’, before setting great store by the fact that it is ‘precisely’ the ‘forlornness’ so palpable in Webern’s music, both at a ‘private’ and ‘historical’ level, ‘that lends it its radiance’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 57–60). It is in this sense, he implied, that his (few) critical remarks would be misconstrued if taken as self-indulgent cavilling. Instead, his initial instinct to cast Webern’s concern for ‘absolute lyricism’ in an ambivalent – to recall his own choice of wording, ‘tragic’ – light, pace Schoenberg’s much more affirmative interpretation, is undergirded by the hope that his review may actually help bolster (rather than damage) Webern’s reputation. As Adorno once envisioned with confidence, his work on Webern, not despite but because of its critical overtones, would ‘tactically … certainly be of advantage to him [Webern]’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 35, emphasis in original).

Indeed, there is good evidence that Webern recognised the ‘tactical’ value of Schoenberg and Adorno’s writings on his aphoristic music and in fact aligned himself with their interpretations in moments where he found himself cast in a defensive position. So, for instance, in a letter to his publisher Emil Hertzka from 6 December 1927, Reference WebernWebern (1959: 15) used an expression that palpably echoes Adorno’s phrase of ‘absolute lyricism’: ‘I know, of course, that my work has very little importance regarded purely commercially. The cause of this lies in its almost exclusively lyrical nature [!] up to now; poems do not bring in much money, but after all they still have to be written.’ And in a letter dated 4 September 1931 to the conductor Hermann Scherchen, Reference WebernWebern (1945/6: 390) launched an apologetic defence of his aphoristic works clearly alluding to Schoenberg’s preface: ‘sometimes it takes a whole novel to express a single thought; and sometimes no less substantial or few thoughts are condensed into a single short poem’.

The striking confidence with which Webern, at this critical stage in his creative development, projected a public image of himself as a musical lyricist opens up some wide-ranging perspectives. Perhaps the question about Webern’s lyrical style is not one of ‘style’ at all, but rather his attitude towards the stylistic means and devices available to him at a given time and the ‘ideas’ he sought to express. In this precise sense, Webern did not compose in a certain ‘style’ – the style of ‘dodecaphony’, ‘free atonality’, or ‘late Romanticism’ – but in the ambit of lyricism. Much of the fascination that thus comes with Webern’s music lies in the sheer plethora of unique strategies that it presents to articulate highly expressive and distinctive physiognomies of the lyric.

Lyricism as Space

For the purpose of studying the ways the category of the lyric has shaped Webern’s twelve-tone thinking, his famous lecture series on The Path to the New Music (1932–3) provides some first insights. Although the lyric finds no mention in it, Webern can be shown to interpret some of the key concepts and ideas therein expounded in a decisively ‘lyrical’ light. To illustrate this issue, Webern’s curious ashtray example, presented in his lecture of 26 February 1932, is a particularly pertinent case in point. Having advocated the view that the ‘urge to create coherence [Zusammenhang] has … been felt by all the masters of the past’ (a view iterated at various stages), Webern (once again) finds himself in a position where he feels pressed to offer an explanation of what the concept of musical coherence means. Not a man of words, Webern, apparently impromptu, seeks to illuminate the issue as follows: ‘An ashtray, seen from all sides, is always the same, and yet different.’ And he adds: ‘So an idea should be presented in the most multifarious way possible’ (Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963: 53).

While one might imagine (with some delight) Webern swirling an ashtray through the air – first holding it up still, before flipping it around again and again – the question begins to emerge what this discussion really reveals about his understanding of musical coherence. Indeed, many of the examples that Webern presents – the treatment of fugal subjects in J. S. Bach’s Musical Offering, the motivic-thematic processes in the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and the developing variations characterising Schoenberg’s First String Quartet op. 7 – suggest a reading of the term that renders it essentially a linear-developmental principle hingeing on the notion of becoming (see Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963: 35, 52, and 58). Positing these examples with respect to Webern’s discussion might thus lead to an expectation that he would describe the ashtray as the subject of an (irreversible) temporal process – for example, by pondering what it would take for it to be transformed into a different object, say, a pile of fragments. This, however, is not the case. Instead, Webern’s discussion implies that it is the observer’s perspective on the ashtray that changes, while the ashtray itself remains the same. Thus, for Webern, the ‘multifariousness’ that he contends should arise from the presentation of a single musical ‘idea’ does not – in contrast to his many music examples – originate from a genealogical but a perspectival mode of musical thinking, a mode of thinking that Reference Ligeti, Metzger and RiehnGyörgy Ligeti (1984: 104) saw as the fundamental crux of Webern’s late aesthetic: the tendency ‘to treat musical time in such a way as to treat it as a spatial phenomenon’.

These nested inconsistencies can also be discerned in other parts of Webern’s lectures, such as in his famous discussion of Goethe’s ‘primeval plant’ (Urpflanze). Enshrouded in some esoteric-philosophical ideas about nature and art’s relationship to it, in Webern’s hands the Goethean primeval plant shines forth as nothing less than a (vexed) mirror of aesthetic self-legitimation. On some level, Webern conveniently exploits the genealogical epistemology built into it, both in historical and musical terms. In particular, he avers that the development of the twelve-tone method is the logical consequence of music history as evolutionary progress, and he moreover contends that the concern of past composers ‘to create unity in the accompaniment, to work thematically, to derive everything from one thing’ breathes new air in the domain of twelve-tone composition. However, in other moments of his discussion he, inexplicitly, reverses this genealogical notion into its opposite, a static one. Insomuch as the twelve-tone technique, as an ‘underlying’ method, always already guarantees ‘unity’ and ‘comprehensibility’, he argues, for instance, it has become possible to ‘treat thematic technique much more freely’, before once more making recourse to Goethe’s primeval plant but now – notably – as a paradigmatic model of structural identity: ‘the root is in fact no different from the stalk, the stalk no different from the leaf, and the leaf no different from the flower: variations of the same’ (Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963: 40 and 53).

By pointing out these subtle yet fundamental shifts in his explications, I do not wish to suggest that there is anything wrong (or right) with Webern’s discussion. My concern is rather with the ways in which these shifts reveal a constitutive tension in Webern’s musical thinking, one that arguably tends to become all too quickly obfuscated once the categories and ideas expounded in his lectures are taken at face value or considered no more than blueprints of Schoenberg’s theorisation of the concept of musikalischer Gedanke (see Reference Schoenberg, Carpenter and NeffSchoenberg 1995). To rephrase the issue in a heretical way: what would be gained, what would be lost, by taking the sceptical-contemplative view that the late Webern may not have understood himself – or, for that matter, Schoenberg?

Lyricism as ‘Variations of the Same’

In seeking to explore the implications of his ashtray example and his discussion of the Goethean primeval plant, it seems apt to attend to Webern’s ubiquitous use of structural symmetries and permutations. Often couched in terms of a complex dialectic between ‘construction’ and ‘expression’, these salient features in Webern’s music have been the subject of enormous analytical efforts. In the following, I will draw upon two theoretical conceptions of harmonic space – the intervallic and transformational ones – as ways of exploring how Webern’s axiomatic concern for ‘variations of the same’ can be considered in analytical terms.