During his lifetime he was a leading member of the avant-garde and would have never felt himself to be anything else.

We remain incorrigible romantics!

If there is a single, enduring quality in Alban Berg’s serial works (c. 1925–35), it is his ability to use the twelve-tone method of composition as a form of exegesis for his personal, intellectual, and musical heritage in musical narratives suffused with apparent contradictions. From his first twelve-tone composition, the second version of his song ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’ (1925), to his last work, the Violin Concerto (1935), Berg grappled with efforts to establish his own identity as a modern composer while dealing with issues related to personal and artistic influences from individuals such as Wagner, Mahler, Wedekind, and Kraus, as well as the overbearing figure of Schoenberg. In contrast to his former teacher, who was openly averse to external influences, Berg embraced an array of individuals as ‘ideal identities’ (Reference SantosSantos 2014), to be played out in his creative process. In doing so, Berg combined what have been generally understood as antithetical ideas in an attempt to elevate his method of composition as an overarching system that brings together his modernistic aesthetics and the art of the past through textures in which twelve-tone serialism and tonality are interwoven.

Such an approach to composition was bound to be controversial from the very beginning, as serialism was supposed to be a logical antidote to the excesses of tonality as practised by the late Romantic composers. Because Berg’s approach to serialism embraced gestures of tonality, it also attracted criticism even from members of his own circle. In 1946, Schoenberg wrote an addendum to his essay ‘Composition with Twelve-Tones’, where he engaged in a blistering judgement of Berg’s approach:

I have to admit that Alban Berg, who was perhaps the least orthodox of us three – Webern, Berg and I – in his operas mixed pieces or parts of pieces of a distinctive tonality with those which were distinctively non-tonal. He explained this, apologetically, by contending that as an opera composer he could not, for reasons of dramatic expression and characterization, renounce the contrast furnished by a change from major to minor.

Not accepting Berg’s explanation, Schoenberg continued: ‘Though [Berg] was right as a composer, he was wrong theoretically’ (Reference Schoenberg and SteinSchoenberg 1975a: 245). It is difficult to assess Schoenberg’s sincerity when he considered Berg to be ‘right’ as a composer while mixing serialism with tonality, as Schoenberg’s main concern as a composer was to establish relational events based on the initial idea of a composition. A piece that starts with a twelve-tone series would logically develop configurations afforded by the series, and these configurations would not be tonal. His consistent position on this issue is well documented. Schoenberg’s statement puts forward, nevertheless, a conflict between the notion of the composer as composer versus the composer as theorist, and the implication that, because Berg used tonality for ‘dramatic expression’, he was less systematic in his compositional process. Such a view has helped perpetuate the notion that Berg was ‘more Romantic’ than the other members of his circle – a view that has slowly been challenged since the autograph sources preserved at the Austrian National Library were opened to scholars in 1981.

Compounding the problem discussed above is the pervasive concept of a ‘Second Viennese School’ with the figurehead of Schoenberg followed by his ostensibly faithful pupils (Reference Auner and SimmsAuner 1999). As a result, Schoenberg’s shadow remains a long one. As Taruskin puts it, Berg was ‘formerly a pupil – and still very much a disciple – of Schoenberg’ (Reference TaruskinTaruskin 2005a: 193; my emphasis). Taruskin is not alone in subjugating Berg to Schoenberg. Berg did it himself. While dedicating his opera Lulu to Schoenberg on 28 August 1934, Berg wrote:

Please accept it, not only as a product of years of work most devoutly consecrated to you, but also as an outward document: the whole world – the German world, too – is to recognise in the dedication that this German opera – like all my works – is indigenous to the realm of that most German music, which will bear your name for all eternity.

Such expression certainly contributed to cementing Schoenberg’s approach to twelve-tone composition as the standard for analyses, a point of departure and constant reference in the interpretation of Berg’s musical language. George Perle, who established one of the most groundbreaking frameworks for analysing Berg’s music, argues defensively that ‘Berg’s characteristic practice … significantly distinguishes his twelve-tone technique from Schoenberg’s and Webern’s’ (Reference 392PerlePerle 1989: 9). In his book Serialism, Whittall argues that ‘like his fellow Schoenberg pupil Anton Webern, Berg had followed the master into the brave new world of post-tonal and total chromaticism’ (Reference WhittallWhittall 2008: 65). While there is no denying Berg’s indebtedness to Schoenberg’s musical and intellectual mentoring in his early years, the extent to which Berg followed Schoenberg in his mature years is certainly debatable, especially after the success of his opera Wozzeck (1914–22). Moreover, Berg’s differences are evident in the ways in which his twelve-tone compositions do not fit – and surely were never meant to fit – Schoenberg’s model. Berg was keenly aware of his position and approached his method of composition as a means of establishing ‘something more genuinely Berg’ (Reference BergBerg 2014). Adorno was one of the first to recognise the unique qualities in Berg’s music and openly expressed his goal of separating him from the other members of the so-called Second Viennese School. In a parenthetical comment on a letter to Berg on 23 November 1925, he put it bluntly: ‘this prattling about the “Schoenberg pupil” must stop’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 28).

Another important feature in Berg’s music is his penchant for inscribing his works with a multiplicity of extra-musical narratives, especially programmatic and autobiographical references (Reference FlorosFloros 1994; Reference PerlePerle 2001). From Adorno’s early description of the Lyric Suite as a ‘latent opera’ to the numerous essays written about Berg’s so-called ‘secret programmes’ (Reference Jarman and PopleJarman 1997; Reference PerlePerle 2001), it is clear that these features are ingrained in his approach to the compositional process. By now, it is impossible to dissociate Berg’s compositional choices from the extra-musical significations.

Together, these features encode Berg’s music with apparent antinomies that prove to be challenging to any method of analysis. Hailey puts it best:

Contradiction and paradox are central ingredients to Berg’s persona and of his music. He was a man of open amicability and of many secrets; a faithful friend and an eager consumer of malicious gossip; a composer of fierce modernism who courted popular appeal. The elusive qualities of his character make it easy to be sucked into a vortex of eternal regress and self-absorption. Berg, the man, we follow at our own peril. Berg the composer, however, transformed the spinning vortex of his unknowable self into extraordinary music that reaches beyond the self toward a common understanding of the human condition.

While contradiction and paradox may seem problematic, they are the modus operandi in Berg’s compositional process and must be considered as such. Perhaps these are the features that resonated most with Adorno and may explain in part his championing and defence of Berg’s music throughout his life. For Adorno, as Morgan Rich has demonstrated, Berg’s approach to twelve-tone serialism corresponds to his working out the concept of negative dialectics – a concept usually associated with Adorno’s late thought – and the ways in which his reflections on twelve-tone music were integral to his philosophical work. In Adorno’s view, Rich observes, ‘the strict twelve-tone style stopped the dialectical process in music. Schoenberg’s “laws” stopped the work from making a way forward’ (Reference RichRich 2016: 81). As Adorno expressed it to Berg, ‘there is only a “negative” dodecaphony, being the utmost rational borderline case of dissolution of tonality (even when tonal elements appear within dodecaphony; for then they, as a construction, are coincidental in their tonality, being simply dictated by the row!)’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 71–2). Ultimately, the apparent contradictions in Berg’s music correspond to what Adorno terms a ‘category of reflection’ (Reference AdornoAdorno 2007: 144). While Geuss has argued that Berg was not interested in Adorno’s philosophical thought (Reference Geuss and PopleGeuss 1997: 38), the possibility that a two-way exchange existed between them, and that Adorno, like many others, may have influenced Berg as well is worth considering.

Theory and Practice

As I have suggested, one of the most pervasive problems in the various analytical studies of Berg’s music relates to the ways in which Berg handles serialism and tonality in his mature works. In one of the most comprehensive analysis of Berg’s music, while favouring cyclic constructions, Headlam adopts a provocative tone: ‘Berg’s later music … is not truly twelve-tone – except for the second version of the song ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’ – despite the presence of rows and characteristic twelve-tone techniques. It is also not the case that Berg “fused” twelve-tone techniques with tonality’ (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 195). Referring to the Bach chorale ‘Es ist genug’ in the Violin Concerto, for instance, Headlam argues that ‘its tonal language seamlessly emerges from and dissolves into the surrounding cyclically-based passages’ (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 199–200). Whittall, arguing that we cannot ignore the highly recognisable tonal passages in Berg’s music, suggests ‘the possibility that [Berg] liked the idea of using such dramatic oppositions in non-arbitrary but still potentially disorientating ways should not be rejected out of hand’ (Reference WhittallWhittall 2008: 74–5). Clearly, as Ashby has argued, ‘serialism has become more important and specific as a historiographical marker for us than it was as a compositional device for anyone in the Schoenberg circle’ (Reference AshbyAshby 2002: 399; emphasis in original). Indeed, it should not be forgotten that, when Berg started exploring serial techniques, there was no ‘theory’ of twelve-tone music, and Berg learned from an eclectic array of sources as were available to him. A set of autograph manuscripts held at the Austrian National Library, for example, demonstrates the lengths to which Berg went in analysing Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano op. 25. Of particular significance is the way in which Berg isolates the second tetrachord of the row [G♭, E♭, A♭, D] and labels it ‘tonika’ (ÖNB Musiksammlung F21 Berg 107/i, fol. 2 v), reordering the other elements so as to form a chromatic ordered set (F21 Berg 107/i, fol. 1). In another page, Berg experiments with cyclic formations, more closely associated with his own practice than with Schoenberg’s (F21 Berg 107/i, fols. 4 and 4 v).

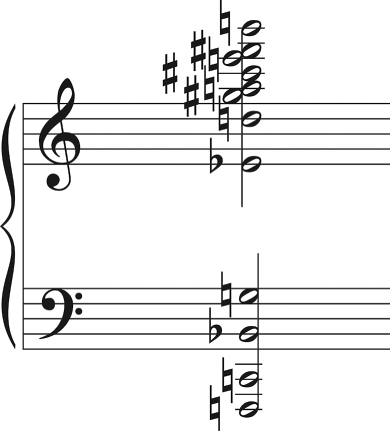

While revisiting the origins of Berg’s approach to twelve-tone composition, Ashby has compellingly demonstrated that Berg’s approach to serialism has close affinities with the discoveries of his student Fritz Klein, who, like Josef Matthias Hauer, may stake a claim to have generated a model of dodecaphony independent, at least to begin with, from Schoenberg’s (Reference AshbyAshby 1995). In a letter to Schoenberg on 13 July 1926 (located in Box 29, Folder 11, Arnold Schoenberg Correspondence and Other Papers, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington DC), while explaining his conception and use of the row in the Lyric Suite, which is the same one used in ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’, Berg was remarkably upfront about his indebtedness to Klein, particularly his borrowing the all-interval set (Figure 5.1) and the ‘Mutterakkord’, an all-interval twelve-tone chord (Figure 5.2) (see Reference Berg, Schoenberg, Brand, Hailey and HarrisBerg and Schoenberg 1987: 349–51; Reference BergBerg 2014: 203). For Berg, the axis of symmetry and the potential tonal references within the row were particularly attractive, even if they restricted the number of possible transpositions of the series (Figure 5.3). Of significance is Berg’s concern with the hexachordal content of the series and its potential for generating cyclic structures and invariant segments, which became defining traits in his musical language.

Figure 5.1 Berg’s illustration of the row set in the Lyric Suite, borrowed from F. H. Klein (Reference BergBerg 2014: 203)

Figure 5.2 Berg’s illustration of the all-notes and all-intervals chord

Figure 5.3 Berg’s illustration of axis of rotation generating the C major and G♭ chords and scales

While Berg’s use of Klein’s all-interval set and the all-interval twelve-tone chord are the most visible markers of his influence, it was perhaps Klein’s aesthetics that provided the intellectual foundation for Berg’s approach to his later compositions. Consider Klein’s statement about the results of what he called Musikstatistik [statistics of music]: ‘Since in my statistics of music all chords, from the simple triad to the complex Mutterakkord, are equal citizens in a realm of tones (the only fair estimation!), their consequences, namely tonality and extonality, are also to be considered equal manners of expression’ (quoted in Reference AshbyAshby 1995: 72–3). This comment seems to neutralise the notion of a conflict between tonality and atonality, even suggesting a lineage between the ‘simple triad’ and the all-interval twelve-tone chord. While Berg had explored some proto-serial features in his music before 1925 (Reference 392PerlePerle 1989: 1–6; Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 194–216), his earliest attempt at the twelve-tone method of composition was his second setting of Theodor Storm’s poem ‘Schliesse mir die Augen beide’. The first setting, composed in C major in 1907, was dedicated to Helene Nahowsky, his future wife; the second setting was dedicated to Hanna Fuchs, after a liaison that started in 1925 (Reference Floros, Berg and FuchsFloros, Berg, and Fuchs 2008: 54). The two pieces were originally published side by side in the periodical Die Musik in 1930 and included a dedicatory note to Emil Hertzka, in celebration of Universal Edition’s twenty-fifth anniversary, in which Berg describes the works as representing the progression of music in a quarter of a century, from tonality to twelve-tone serialism (Reference ReichReich 1930). Together, the two versions capture Berg’s teleological perspective on twelve-tone serialism, from interwoven traits of tonality latent in the formation of the series to the use of musical gestures as expressions of his autobiographical impulses. Berg’s motive for publishing the two versions side by side appears to be both an affirmation of Klein’s aesthetics and a justification for his own musical language.

Berg’s extraordinary explanation of his method advances some of the theoretical precepts that underlie both Perle’s and Headlam’s approach to analysis of his music but, more importantly, positions him, to borrow Allan Janik’s concept, as a ‘critical modernist’ (Reference JanikJanik 2001: 15–36). Although Janik applies this concept to Schoenberg, it is no less applicable to Berg, as critical modernists found it necessary to become cultural critics in order to defend the principles of logic behind musical composition and appreciation and to confront the art of the past and present as major intellectual figures had done at the time. As Born argues, such a theoretical impulse, at the onset of twelve-tone serialism, was also a defining trait of German modernism (Reference BornBorn 1995: 42). Indeed, as Hall has demonstrated, Berg’s deliberately explanatory attitude towards his compositional process and musical choices is illustrated in his numerous annotations throughout the autograph manuscripts (Reference HallHall 1997). When Adorno entitled his book Alban Berg: The Master of the Smallest Link, he had a point (Reference AdornoAdorno 1991), for it is now clear that everything in Berg’s music is set with deliberate calculation, even to the smallest detail. In his Sound Figures, Adorno goes further, claiming: ‘That means that there is not a single movement, no section, no theme, no period, no motive, nor even a single note that fails to fulfill its wholly unambiguous and unmistakable formal meaning even in the most complex contexts’ (Reference AdornoAdorno 1999a: 75–6).

The Hermeneutical Impulse

If Berg’s attention to the smallest details in the composition – and, I would add, an architectonic control over the large-scale formal structures – granted him the title of ‘master of the smallest link’, then the composition of the Violin Concerto made him the master of contradictions. The context of the composition is important. Composed at a moment of great distress in the composer’s life, when he found himself in poor health and felt rejected by his own Vienna after the rise of the National Socialist Party – performances of his work had been all but banned in the Germanic world – he felt compelled to stop working on his opera Lulu and accept the commission for the concerto from the American violinist Louis Krasner. The sum of US$1,500.00 would have been a welcome relief for his financial stress. This commission also carried the promise of future performances by the well-known virtuoso as well as the possibility for Berg to validate his own compositional techniques, particularly the juxtaposition of tonality and twelve-tone serialism.

As is well known, this work is fraught with extra-musical associations. Chief among them is the dedication to Manon Gropius, the daughter of Alma Mahler and Walter Gropius, who died in April 1935. Because of Berg’s insertion of the chorale ‘Es ist genug’ from Bach’s Cantata BWV 60 and the dedication of the concerto to ‘the memory of an angel’, the work has been interpreted as a sort of requiem, as well as a premonition of Berg’s own death, which occurred on 24 December 1935 (Reference Pople and PoplePople 1997: 224).

Since the discovery of the so-called ‘secret programmes’ in Berg’s mature works, however, it is also clear that he inscribed the concerto with autobiographical narratives, connecting his present and past experiences. As Douglas Jarman has persuasively demonstrated, the concerto contains a secret programme related to Berg’s affair with Hanna Fuchs, which had started in 1925 and presumably continued up to 1935 (Reference Jarman and PopleJarman 1997; Reference Floros, Berg and FuchsFloros, Berg, and Fuchs 2008). And much as he had done in most of his twelve-tone works from the Lyric Suite to Lulu, Berg encoded both the formal and serial structures of the concerto with elements recalling and retelling that affair. In addition, as if nostalgically referring to his past experiences, Berg included a quotation from a Carinthian folk song apparently related to his past affair with Marie Scheuchl, a maid at his family estate, with whom he had a child at the beginning of the century (Reference PoplePople 1991: 34). These features alone reaffirm Berg’s compulsion to include autobiographical inscriptions in his works. More recently, Jarman has also discussed Berg’s potential overture to the National Socialists, by incorporating the motto ‘Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei’ (‘Fresh, Devout, Happy, Free’) as descriptors of the different sections in the Violin Concerto; he also inscribed its acrostic formed by the letters ‘FFFF’ in a manuscript for the concerto. As Jarman argues, the presence of a symbol with a close relation to German Nationalism in the sketches is deeply problematic, especially after the Nazi electoral success in 1933 and their subsequent attempt to overthrow the Austrian government in July of 1934. Whether Berg used ‘FFFF’ as a symbol of resistance, as Jarman has suggested (Reference JarmanJarman 2017), or as a ‘calculated’, opportunistic ‘rapprochement’ to the Nazi Party, as Walton has argued (Reference WaltonWalton 2014: 75), its inscription in the concerto points to a network of contradictions with different layers of meaning that defies any single interpretation.

Between the private inscriptions and public messages in the Violin Concerto, it is the highly recognisable chorale ‘Es ist genug’, presented as an instrumental reinterpretation of the original message of redemption and transcendence, that keeps inviting interpretations, because it juxtaposes the musical language of the past and present, while representing the most powerful of human experiences: fear, loss, and hope. In its original context, as Eric Chafe has demonstrated, ‘O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort’, BWV 60 occupies a special place amongst Bach’s cantatas because of its message of redemption in death, but also because of its intricate, if not unique, tonal allegory (Reference ChafeChafe 2000: 220–40). Composed for the twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity, this cantata presents a dialogue between two of the most extreme, and perhaps most important, human feelings embodied in the voices of ‘Fear’ and ‘Hope’ in the first three movements. Following the hermeneutics of salvation, the conflict between Fear and Hope can only be resolved through acceptance of death in Christ, whose voice in the fourth movement (‘Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herrn sterben, von nun an’) marks the shift towards the believer’s acceptance of death and life in eternity. The final movement, ‘Es ist genug’, depicts the new consciousness of the believer, who, now with his hope restored, is ready to leave everything behind and enter ‘heaven’s house’ (‘Himmelshaus’). The original text of the chorale, written by Franz Joaquim Burmeister (1633–72) and set to music by Johann Rudolph Ahle (1625–73), reads:

In light of the conflict between Hope and Fear in the initial movements, the concluding chorale characterises, in Chafe’s words, ‘the return of the believer’s viewpoint to the world below as one that has been transformed by that vision into a new sense of peace and security’ (Reference ChafeChafe 2000: 238).

While Berg described his borrowing from ‘Es ist genug’ only briefly in a letter to Schoenberg (Reference Berg, Schoenberg, Brand, Hailey and HarrisBerg and Schoenberg 1987: 466), where he indicated the relationship between the whole-tone tetrachord of the opening melody [A, B, C♯, D♯] and the last four tones of the series (transposed, of course), he must have been aware of the message of the work as a whole. In fact, the setting of the chorale in the concerto, with the alternation between the solo violin and the clarinet ensemble (Part ii, bb. 136–54), seems to reinscribe the conflict between Fear and Hope, and the new ‘consciousness’ of the believer at the end. Berg even provides the original text underlying the orchestration of the chorale.

But even here, Berg includes contradictory elements. As Walton has observed, Berg adds expressive instructions in the score that change the eschatological message of this passage in significant ways. The clarinets, whose sound emulates an organ, are instructed to play ‘Poco più mosso, ma religioso’ whereas the solo violin, portraying the inner conflicts of the individual, undergoes a shift from ‘deciso’, ‘doloroso’, and ‘dolce’, at the beginning, to ‘risoluto’ in the middle section, and finally to ‘molto espr[essivo] e amoroso’ at the end. With these instructions, Berg effectively transforms the dialogue between Fear and Hope into expressions of spiritual and sensual love.

In effect, Berg secularised the cantata just as Oskar Kokoschka had done with a series of eleven lithographs entitled O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort based on Bach’s Cantata BWV 60 (1914) (Reference Hüneke, Heinemann and HinrichsenHüneke 2000: 388; cf. Reference KokoschkaKokoschka 1984: 39). In the sequence of illustrations, the figures of Fear and Hope are replaced with images of Kokoschka and Alma Mahler, with whom he had a relationship around that time (Reference WeidingerWeidinger 1996: 70–1). The series is therefore an allegory of life experience. As Joseph Paul Hodin points out, in Kokoschka’s O Ewigkeit, ‘art and existence are two contradictory worlds closely linked nevertheless by the mediation of man, whose condition vacillates unceasingly between being, becoming, and fulfilment’ (Reference HodinHodin 1966: 131). Ultimately, the series represents a journey of self-knowledge. In Kokoschka’s words: ‘The knowledge that comes from personal experience has an inner force. That experience which releases man from the bondage of transient existence brings the moment of eternal truth comparable to an act of birth. It is the expression of this inner truth which is socially valuable’ (quoted in Reference HodinHodin 1966: 143). Arguably, it is this journey of self-knowledge through mediation of personal experience in art that proved attractive to Berg.

And Berg would not have missed an opportunity to meditate on matters of suffering and transcendence in the second half of the concerto, which begins with a twelve-tone chord that leads to the presentation of the chorale and the set of variations that follows. This section also allowed Berg to convey not only his musical aesthetics, one that embraces serialism and tonality as equals, but also what he considered to be his musical heritage. Of particular significance is the transition to the final section of the Concerto, the ‘Höhepunkt’ of the Allegro (bb. 125–35), which functions as a bridge to the chorale. As Headlam has observed, this section is formed by a ‘monumental combination of pitch and rhythmic cycles’ where Berg lays out eighteen chords, whose top notes comprise eleven pitches, which is complemented by the F held as a pedal in the bass (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 372). In this transition, the solo violin performs seven trichords [024] transposed cyclically at a perfect fourth while unfolding the melody of the chorale [0246]. This passage leads to the initial statement of the Bach chorale and the beginning of the Adagio section (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Pitch reduction of Berg’s Violin Concerto, Part ii, bb. 125–37; after Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Musiksammlung F21 Berg 27, fols. 20 v–21 r

More important, however, is the narrative this passage conveys. In the programme notes Berg provided to Willi Reich, he described the dramatic aspects of the concerto and the role of the solo violin in the following terms: ‘Groans and strident cries for help are heard in the orchestra, choked off by the suffocating rhythmic pressure of destruction. Finally: over a long pedal point – gradual collapse’ (Reference ReichReich 1974: 179). The solo violin unfolding the whole-tone tetrachord that opens the chorale suggests an answer to the cries for help and the important role the solo violin plays in the narrative of salvation.

Indeed, Berg makes clear that in the variations that follow the entrance of the chorale, ‘the soloist with a visible gesture, takes over the leadership of the whole body of violins and violas; gradually they all join in with his melody and rise to a mighty climax before separating back into their own parts’ (quoted in Reference ReichReich 1974: 179). Starting at bar 170, the soloist is gradually joined by the strings until the concerto reaches its climax (the ‘Höhepunkt’) in bar 186 of the Adagio. At the moment of the climax, the solo violin is indistinguishable from the rest of the strings. Then, from bar 193 to 196, the reverse occurs. The strings drop one by one until the solo violin emerges again with the series P9 (7–11 then 0–6) above statements of ‘Es ist genug’ in the violoncellos.

While Pople has related these passages to autobiographical narratives (Reference PoplePople 1991: 37), I suggest that it is a musical rendering of Schopenhauer’s concept of compassion (Mitleid), much as Wagner had done in his opera Parsifal. An excerpt from The Basis of Morality will provide a way of framing the musical narrative of the passages discussed above, particularly with regard to the relational aspect of suffering:

I suffer directly with him [Ich … geradezu mit leide], I feel his woe as I ordinarily feel only my own; and, likewise, I directly desire his weal in the same way I otherwise desire only my own. But this requires that I am in some way identified with him, in other words, that this entire difference between me and everyone else, which is the very basis of my egoism, is eliminated, to a certain extent at least.

The transition to the chorale suggests a complete identification between solo violin and the other strings and a sudden loss of self-identification, realising the ‘pain’ reflected in the orchestra and feeling it as its own, hence the unfolding of the whole-tone tetrachord in anticipation of the chorale. Even here, Berg meditates on his musical heritage, especially his indebtedness to Wagner’s Parsifal. In many respects, the passages above are a sort of instrumental resignification of the transformation that Parsifal undergoes as he resists Kundry’s temptation in Act Two of the opera and feels Amfortas’s pain as his own, after which he realises that only through his leadership would the order of the Knights of the Grail be redeemed. In Berg’s Violin Concerto, the soloist takes the leadership by completely identifying with the string section of the orchestra. In the ‘Höhepunkt’ all differences are eliminated, and the path to ‘redemption’ is reinforced by the variations on ‘Es ist genug’. As Nicholas Baragwanath has argued, Berg’s fascination with Parsifal was instrumental in his understanding of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony and may have been even more instrumental in the ways he conceived symmetries in his post-tonal music (Reference BaragwanathBaragwanath 2004; Reference BaragwanathBaragwanath 1999). Berg also must have understood the narrative of redemption in the opera, which informed the way he wanted the solo violin to ‘act’ in the musical narrative of redemption.

While the Violin Concerto continues to reveal extra-musical meanings and acquire new ones, the sincerity of Berg’s public dedication to Manon should not be easily dismissed (Reference WaltonWalton 2014: 85). If anything, the dedication is an indication of the close relationship between the Bergs and Alma Mahler. Writing to express her condolences to Alma Mahler after the loss of her daughter, Helene Berg made a profound statement – one that captures Berg’s own sentiments towards Alma Mahler and her daughter: ‘Mutzi was not only your child – She was also mine’ (quoted in Reference StephanStephan 1988: 36). This comment reflects not only a strong empathy but also the philosophical concept of compassion (Mitleid) that underlies the narrative of suffering and transcendence of the concerto.

The apparent contradictions, if not the eclectic nature of Berg’s music, his malleable treatment of the series, and the intersections of serialism and tonality in his mature musical language continue to cause uneasiness, especially because his music does not fit any stable analytical models available to us. Headlam’s denial ‘that Berg “fused” twelve-tone techniques with tonality’ (Reference HeadlamHeadlam 1996: 195), Pople’s notion of a ‘synthesis’ of ‘various aspects of his musical world’ (Reference Pople and PoplePople 1997: 220), Ashby’s suggestion that Berg’s use of tonality in his twelve-tone works is ‘performative’ (Reference AshbyAshby 2002: 386), and Walton’s suggestion that Berg was a calculating, opportunistic individual and that aspects of his music were possibly insincere seem to confirm the inherent ambiguity in all aspects of Berg’s mature work. Whittall provides a possible way forward, arguing that ‘Berg provided incontrovertible evidence that the “mechanics” of twelve-tone technique need not inhibit the kind of intense and personal musical expression that maintained recognizable and positive links with the expressive gestures of pre-serial composition’ (Reference WhittallWhittall 2008: 84). It is arguable, as Whittall has suggested, whether Berg saw what we perceive as contradictions to be incongruous at all, in which case the problem would be ours, depending on our set of expectations and whether we are willing to overlook aspects of Berg’s music or biography.