Introduction

The devastating impact of Franz Schubert’s Winterreise arises from our identification with its primary persona. We walk with the wanderer, privy to his thoughts, and imagine ourselves in his shoes, psychologically associating ourselves with the authorial creation. Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin also inspires identification, but our rapport with its central character gradually grows tenuous. We witness the journeyman’s1 enthusiasm, but become troubled by his choices and perceptions, wondering why common sense or rationality do not intervene. Both cycles set Wilhelm Müller’s poetry, feature rejected unfortunates, and address mortality. Yet we regard and respond to their focal figures differently. Die schöne Müllerin solicits sympathy for its greenhorn, encouraging us to understand his feelings and regret his unhappiness. Nevertheless, as Die schöne Müllerin unfolds, we gradually retreat, distancing ourselves from the journeyman. In contrast, Winterreise elicits empathy for its outcast, inducing us to share his emotions and experience similar distress. Consequently, Winterreise evokes our own existential fears as we are drawn near to the wanderer.

Our identification with the protagonists of Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise depends on Müller’s portrayals. But Schubert’s music reifies Müller’s characters and reveals their interiority. Studied side by side, the cycles mutually inform and illuminate.

To begin, narrative summaries of Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise will establish the cycles’ dramatic foundations for identification and enable comparison.2 Next, three factors that influence identification will be explored: form, texture, and contextual processes. Surveys of the cycles’ song forms suggest that formal diversity and structural complexity, rather than simplicity, may enhance identification by demanding and gaining more involved interpretation. Similarly, textural change and complexity appear to promote identification through heightened engagement. Finally, characteristic contextual processes manipulate expectation and enhance dramatic climaxes in certain songs, intensifying identification. Given the richness of Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, comprehensive analysis is impossible. And superiority won’t be decided. But the framework and observations provided here should prompt further inquiry into identification as well as new investigations of narrative, form, texture, and contextual processes within these monuments. Let’s start with their stories.

The Narratives of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise

In Die schöne Müllerin, a miller’s helper with wanderlust leaves his master and encounters a babbling brook that leads him to another mill. The journeyman finds work there, plus a maiden who infatuates him. Grateful but curious, he wonders if the maiden or the brook had drawn him. At the mill, his tiring labor dispirits him because it doesn’t gain the maiden’s attention. So he asks the brook if she loves him, since he’s sure she should have seen his interest. No answer arises. One morning when the eager admirer greets the maiden at her window, she turns away. Undeterred, he plants forget-me-nots below her window as a gentle gesture. Perhaps it works, for one evening, the two sit beside the brook, observing the moon and the stars mirrored in its flow. But the simple swain, who watches her eyes move from the water to him within its reflections while she waits for a word, is too shy to speak and becomes spellbound by the brook’s babbling. When rain falls, all blurs, she says goodbye, then ups and leaves. Daylight finds him not disheartened but ecstatic, wishing to silence the stream, millwheels, and birds to proclaim that the maiden is his. His heart bursting with joy, the young man can’t sing, fearing self-revelation, so he ties a green ribbon around his lute and hangs it on a wall to avoid temptation. When the maiden admires the ribbon (green is her favorite color), the fellow sends it to her, hoping she ties it in her hair. Unfortunately, a passing hunter attracts the maiden, vexing the journeyman. Perceiving rejection, hating the color green, and fixated on hunting, he becomes preoccupied with death, wishing for a verdant grave. Morose, the unfortunate consoles himself with the thought that if he were buried with the maiden’s flowers, her remorseful tears would raise new blooms over his grassy mound in spring. Conversing with the brook, the sad soul ventures that when a lovesick heart dies, everything mourns. But the brook differs, asserting such death provides release from sorrow and brings new life. Persuaded of the brook’s good will, while wondering how it knows love, the fellow perceives its flow’s relief. So, he bids it to continue. Ultimately, only the brook remains, having welcomed the journeyman to watery rest with a lullaby.

In Winterreise, an ardent suitor, mortified by his beloved’s marriage to a rich man, slips away from the scene of his rejection, leaving “good night” traced in snow on her gate. With the wind-whipped weathervane mockingly creaking atop her house, he realizes it’d earlier signaled her fickleness and her family’s indifference. Frozen tears fall from the outcast’s cheeks, surprising him, for he’s unaware of his weeping and his waning sensitivity. Curiously, he imagines, the freezing weather has dulled his pain yet preserved the woman’s image within his now-numb heart as a souvenir. Should his heart thaw, he muses, her image would drain away. Passing a familiar linden tree, which seems to bid him to stay and rest, the fugitive closes his eyes and resists consolation, shunning the tree’s warm memories and sheltering comfort for a cold road. Yet its rustle continues calling after he leaves. While the glacial chill freezes his burning tears as they fall into the snow, he is sure that their fervent glow will return when they melt and run into the brook by his beloved’s house. Like the nearby river, now ice-encrusted, the exile suspects that his now hardened heart also might hide a torrent, and wonders if it, too, sees its reflection in the river’s frozen flow. Anxious to leave town and escape its memories, yet sorely tempted to glance backward toward his ex-sweetheart’s house, he doesn’t succumb. Instead, the fugitive follows a flickering “will-o’-the-wisp” into rocky chasms below the town, wending his way in the dark along a dry stream bed into wilderness. Later, an abandoned hut provides refuge though no respite, for his body aches and his heart stings. Nevertheless, he sleeps, dreaming of spring and his beloved, only to wake up cold and alone, ever more wretched in the morning stillness. A distant posthorn makes his heart pound, reminding of the town and prompting him to seek news, but he doesn’t respond. Three omens – including frost that greyed the young man’s black hair, a crow that trailed him as if he were prey, and a leaf that clung to a tree branch and fluttered like his hope – all forewarn but don’t daunt him. Barking dogs in a nearby village, the poor fellow figures, might disturb its residents’ dreams, but he has no more dreams nor any need for further delay. So he ventures into the now-stormy morning, led on by another illusory light. Following disused paths and ignoring city signposts, the outcast relentlessly pursues solitude, reaching a graveyard where he might rest for a while, yet the cemetery holds none for him. Without sleep, and without any particular goal, he pushes forward against wind and storm, driven by faithless and fatalistic courage. Phantom suns at the morning horizon transfix him, prompting the figment that since his beloved’s bright eyes are gone from his life, his last source of light might as well follow. Outside another village, the wanderer sees a barefoot and benumbed hurdy-gurdy player grinding alone, ignored except by snarling dogs. Perceiving their similar situations and parallel prospects, the wanderer asks: “Shall I go with you? Will you play your organ to my songs?”

The Journeyman, the Wanderer, and Us

Today, some aspects of these stories seem senseless. Who abandons family, friends, community, connections, and job for utter uncertainty? Who chats with a brook or naps in a boneyard? Even assuming dysfunction, certain parts of these narratives remain foreign, incomprehensible, or indeterminate. Each protagonist transforms from naïf to reject to wretch, a progression few of us know. Which conclusion is more tragic – a suicide or a shattering – is debatable. So is whether either story offers catharsis. Yet somehow these tales prompt us to suspend disbelief and identify with their characters, albeit in different ways and to varying degrees.

In Die schöne Müllerin, portrayal of a detailed past, unexpected immaturity, extreme behavior, and a supernatural context suppresses identification in favor of observation. Winterreise also presents extreme behavior, but its narrative’s absorbing events and compelling interiority prompt self-projection. With fewer historical specifics and no supernatural presence, Winterreise’s evocative context elicits imaginative compensation that augments engagement. Die schöne Müllerin features a more traditional plot, variations on common characters, familiar situational elements, foreshadowing, decisive action, plus an epilogue, all of which would induce and reinforce an observational mindset. But it would seem that the focus on thoughts, feelings, and reactions in Winterreise hits home hard by eliciting deep-seated resonances within unguarded and receptive listeners. In any event, certain traits and choices of the central characters induce identification within us. The more we share with a character, the more we identify with and self-project upon him or her. The more that is alien to our nature and experience, the more we disassociate.

All of us can recall being anxious and curious about the future like the journeyman of Die schöne Müllerin. We also can remember being excited by our attraction to another while being uncertain about reciprocation and impatient to be noticed. So it’s easy to accept the fellow’s initial anthropomorphizing of the brook as idle reverie. And it’s easy to recall feeling ignored or rebuffed by a heartthrob, hoping that a small kindness might help, as well as being too shy to respond at an opportune moment. Our resonance corresponds to identification. However, the young man’s misinterpretation of the maiden’s abrupt departure during their rendezvous represents an unsettling and alienating development. And while we may understand the journeyman’s jealousy of the hunter and perceive his depression about the maiden’s new fascination, his death wish and delusion regarding the young woman’s remorse are too much to bear. His final conversation with the brook elicits rue, as does his irrevocable choice, though both distance us. Serious questions arise. Was that last exchange between the journeyman and the brook imaginary … or was it real? Even more disconcerting is the sneaking suspicion that an apparently benign yet possibly malevolent being may have been present all along. Was the brook stalking him from the start? As engaged auditors of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, we gradually distance ourselves in self-defense, pitying the fellow more than identifying with him. When the brook provides the song cycle’s epilogue in “Des Baches Wiegenlied,” with the journeyman nowhere near, we are left with a character we neither know nor trust – the brook – and feel pulled back into the scene while the longest song of the cycle unfolds. Although the narrative’s primary persona is no longer there, our identification with him continues, causing us to feel uneasy in the brook’s presence.

While few of us have suffered the humiliation endured by the wanderer in Winterreise, many have felt the need to escape after rejection or betrayal, recognizing signals of imminent rupture only in retrospect. In such situations, one is overwhelmed by emotions of differing intensities – unaware of some because others obscured, unsure what each was, uncertain how to respond, unclear what to do next – and one spurns solace to sublimate pain by whatever works. Of course, seeking seclusion in a nocturnal forest isn’t something most would do, nor is staying overnight in a derelict dwelling. However, we can accept these conceits for the sake of the story, the flow of the music, and our own curiosity. Surely sleep’s relief is a familiar experience, as is the shock of reality’s return at dawn. So is the inability to anticipate welling memories, along with the need for sidestepping situations that summon them. What Winterreise does so well in its second half is portray the wanderer’s gradual, inexorable descent into a much darker place, one that all of us have glimpsed or can imagine: a depressive and disoriented state in which perceptions and judgement should become suspect, but do not, wherein one steels oneself to press ahead, yet without a clear goal, and through which wellbeing is not a priority, though it should be. While the wanderer doesn’t determinedly pursue oblivion, one senses that if Death, Fate, Nature, or some other claimant came for him, he wouldn’t resist. The “will-o’-the-wisps,” ominous indications, and phantom suns – all readily-explainable sights – seem more immediate and serious than they really are. But to the despondent outcast who’s not slept for twenty-four-plus hours, they’re plausible parts of his mental landscape. Happening upon an apparently similar soul at the end of Winterreise, he senses kinship and directly addresses another human for the first time. But serious questions arise here too. Is the hurdy-gurdy player real? What happens next? Unlike with Die schöne Müllerin, we do not feel drawn back into the final scene of Winterreise because we never really left. Instead, our identification becomes ever more intense, for we, from our vantage point, cannot fully fathom what’s going on in the winter wanderer’s mind or grasp what his future holds, only guess.

It’s not imperative that Müller and Schubert answer any open questions regarding Winterreise or Die schöne Müllerin. Posing them was the point. By providing a shared aesthetic experience to audiences, the artists increase affiliation, initiate conversation, and perhaps inspire kindness. Clear conclusions constrain cordial conversation! So, how does Schubert enhance our identification with Müller’s characters? Form, texture, and contextual processes assist.

Song Forms and Identification in Schubert’s Song Cycles

Formal diversity and structural complexity influence identification in Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise. How they do so may surprise. Let’s examine the song forms.

Within Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, eight Lieder exhibit simple strophic form, a design primarily founded on the principle of repetition. Each features a repeat-sign-bound span supportive of two to five sections, symbolizable as ||:A(+A′,[etc.]):||.3 These include “Das Wandern,” “Ungeduld,” “Morgengruss,” “Des Müllers Blumen,” “Mit dem grünen Lautenbande,” “Der Jäger,” “Die liebe Farbe,” and “Des Baches Wiegenlied.” Additionally, “Tränenregen” is semi-strophic. It begins with three sections involving repeated music but concludes with an abbreviated variation of that material that serves as a coda, representable as ||:A(+A′,A″):||A‴.

Four Lieder in Die schöne Müllerin employ the principles of contrast, return, and variation to produce ternary forms representable as ABA′. These include “Am Feierabend,” “Mein!,” “Pause,” and “Der Müller und der Bach.” “Der Neugierige,” portrayable as ABB′, just stresses the principles of contrast and variation, while “Trockne Blumen,” expressible as AB, only features contrast. Finally, five may be considered through-composed, including “Wohin?,” “Halt!,” “Danksagung an den Bach,” “Eifersucht und Stolz,” and “Die böse Farbe.” While these through-composed Lieder certainly draw upon the principles of contrast, return, and variation, plus that of development, all impress more as unique designs rather than instances of a common pattern.

Schubert’s Winterreise includes only one simple strophic song, “Wasserflut,” representable as ||:A(+A′):||. Another, “Gute Nacht,” features modified strophic form expressible as ||:A(+A′):||A″A‴. Its opening sections present the same accompanimental music, the third incorporates significant variation, while the last bears even more substantial developmental changes. “Der Lindenbaum” lacks repeat signs and stresses variation, presenting a structure symbolizable as AA′A″ that mixes strophic, ternary, and variational characteristics. Its second section presents a change of mode as well as reinterpreted material with a substantial extension, while the third features further reinterpretation, a brief extension, plus a postlude.

Even more diverse designs that draw upon the principles of contrast, return, variation, and development appear within Winterreise, including these thirteen:

- ABA′B′

- ABA′B′coda

- ABA′

“Rückblick,” “Der greise Kopf,” “Die Krähe,” “Im Dorfe,” “Täuschung,” “Die Nebensonnen”

- AA′

- ABCA′B′C′

- AA′B

The preceding summary highlights two factors involving formal diversity and structural complexity in Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise. One pertains to strophic form, the other to structural design distribution.

Strophic form, characteristic of folk-songs and ballads, bears a bardic impression and elicits a corresponding listening posture. We settle in for an intriguing tale or moralistic story with repeated music and predictable breaks in the action that permit brief relaxation. One might assume that predictable, familiar music, plus time for reflection, would assure automatic and deep immersion in the narrative, but that’s not always nor necessarily true. Strophic form’s archaic aura distances us, diminishing identification by regular reminding that its recitation relates to a character from the past. Strophic form is interruptive – our concentration recedes, then ramps – and this cannot help but affect our focus, and in turn, the intensity of our identification with the protagonist. And of course, some stories in strophic forms chafe at their repeated musical vehicles, with later verses not fitting as well as earlier.

Sectional and through-composed songs are less predictable in nature, and their unfolding structures often are more extended in length, more internally complex, and more responsive to their texts. One might assume because they require more continuous attention and sustained interpretation, even over divisions and pauses, that we become overwhelmed. However, their increased interpretive demands actually appear to intensify identification by immersing us in detail, encouraging recognition and association, both consciously and subliminally. Of course, Schubert’s engaging musical style contributes too!

Eight of the twenty Lieder in Die schöne Müllerin express simple strophic form, while just one of twenty-four in Winterreise does. With limited emphasis on that familiar form – which distracts by drawing attention to itself – and a great diversity of forms whose structural complexity requires a consistently high level of focus and interpretation, Winterreise seems to promote a correspondingly high level of identification with its primary persona. Engrossing us, Winterreise prompts perception of personal connection with its central character.

To sense how this is so, we may begin by comparing and contrasting increasingly complex Lieder from the two cycles, starting with two songs from Die schöne Müllerin. “Ungeduld” – a strophic song representable as ||:A(+A′,A″,A‴):|| – and “Tränenregen”– a semi-strophic song representable as ||:A(+A′,A″):||A‴. Both begin in A major and present outdoor vignettes sketched by the journeyman miller. In “Ungeduld,” the young man’s exuberant expression of love is infectious and unyielding, a portrait of bottled impatience. In “Tränenregen,” which recounts the rendezvous by the brook, his ardor remains, though more subdued as it is sustained through the first three spans. However, “Tränenregen” takes a surprising turn within its final section, where initially familiar material briefly tonicizes C major (m. 28), quickly returns to A major (m. 32), and closes in A minor (m. 36) to underscore the young man’s shattered reverie and his beloved’s abrupt departure. Its narrative and musical shifts demand more, and we contribute more while perceiving more.

“Gute Nacht,” the first Lied of Winterreise, offers an even greater interpretive challenge. Embodying modified strophic form – ||:A(+A′):||A″A‴ – its first three sections all feature tonal flow from D minor, to F major, to B♭ major before D minor returns, underscoring the fluidly shifting moods of the ex-suitor in front of his beloved’s house. The third presents changes in the main melody, plus an extension with a more prominent piano part, to portray rising regret as the protagonist prepares to leave. The final section brings a surprising switch to D major to convey rueful acceptance, though the postlude’s minor close bears (and bares!) genuine grief. For engaged listeners, the changes require more, we invest more, and we gain more.

“Der Lindenbaum,” from Winterreise, presents a design – AA′A″ – that might be considered either modified strophic or three-part form. Its piano part becomes increasingly energetic and expansive to portray enveloping elements and emotions as the wanderer weighs the tree’s offer of rest. The song’s contrasting central variant, which starts in minor, moves to major, and concludes with an extension (mm. 45–58), communicates the wanderer’s determination to reject the linden tree’s comfort and move on, even as cold winds blow off his hat. The final section of “Der Lindenbaum,” all in major, captures the diminishing pull of memory dominated by the ex-suitor’s desire to get away. The composition’s individuality and suggestiveness impel us to seek meaning, infer, recognize, connect, and understand. In turn, we cannot help but resonate with the emotions expressed by the wanderer character.

While the formal diversity and structural complexity of Schubert’s song cycles may only be generally compared, it would seem that Winterreise’s interpretive demands require considerable conscious concentration from engaged listeners and are apt to elicit substantial background processing of its narrative that may encourage identification with its protagonist. Texture appears to bear similar implications.

Texture and Identification in Schubert’s Song Cycles

The textures of Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, like much Western art music, may be characterized using visual terms. More specifically, textural elements within a given span of music may be interpreted as belonging to its foreground, middleground, or background.4 A Lied’s vocal melody, when present, predominates in the foreground. We focus on it like a painting’s subject. A bass line in the piano’s accompaniment, when conceived as a counterpoint to the vocal melody, belongs to the song’s middleground. It complements the more prominent part, enriching the structure while informing interpretation. If the bass is less distinguished, it may recede into the Lied’s background. Yet a bass line or an upper accompaniment strand may project into the foreground when the voice is absent or when the bass doubles the voice, or strive for attention within the middleground when interacting with the vocal melody. Harmonic accompaniment elements belong to the background. As this general overview suggests, the components of a song’s aural field may change roles rapidly in real time – they’re not always static. Texture enhances identification with the primary personae in various ways within Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, usually in conjunction with other elements, and sometimes achieves remarkable effects through brief and/or inconspicuous details in the middleground or even in the background. Let’s see how.

For instance, at the start of Die schöne Müllerin, the journeyman’s infectious energy may be perceived within the opening vocal phrases in mm. 4–7 and 8–11 of the first Lied, “Das Wandern,” which seem a bit rushed at three measures plus a pickup. Example 9.1 offers illustration.

Example 9.1 Die schöne Müllerin, “Das Wandern,” mm. 1–125

Answered by the piano’s brief melodic responses (dʹ-fʹ-dʹ) that emerge from the rolling background in the right-hand part of mm. 7–8 and 11–12, these foreground/middleground textural alternations communicate youthful enthusiasm anyone can sense. The third phrase brings textural contrast through a seemingly more expansive and invigorating voice/bass duet that’s sequential in nature, while the last phrase highlights the voice’s repetitive and diminishing melody with undulating harmony in the background. Repeated four more times via the song’s strophic structure, the music of this song, with its jaunty physicality, visual suggestion, and textural variety, snags us for the rest of the cycle. Yes, there’s more than just texture involved here, but the shifts within “Das Wandern” contribute to its engaging and exhilarating impression.

Surely the shifting textures of “Der Neugierige” intimate the journeyman’s interiority in ways that inspire identification. Example 9.2 offers its first twelve measures.

Example 9.2 Die schöne Müllerin, “Der Neugierige,” mm. 1–126

Gradually moving three times in its opening section (mm. 1–22) from a relatively thin, high, and delicate texture to a thicker, lower, and more resonant one, the Lied initially communicates his fluctuating curiosity by textural expansions in the middleground and background. The texture expands, flourishes, and then recedes. With the emergence of triple meter and undulating arpeggios of the second section, ushered in by the void of m. 22 which conveys a shift of focus that heightens tension, we can virtually see and share in the character’s contemplation as he queries the brook about his beloved’s feelings. And the recitative-like texture of mm. 33–40 seems to come out of nowhere, portraying a dramatic flight of imagination as he asks for a “yes” or “no” whether the miller’s daughter loves him, turning the request over and over in his mind as he wonders. Varying and evolving texture tells what’s going on inside the young man, which, in turn, encourages our identification with him.

Other textural features within Die schöne Müllerin portray interiority. For instance, the delicate, charming, and unexpected echo in the middleground of mm. 16–21 of “Morgengruss” would seem to suggest an ethereal image passing through the journeyman’s mind, at least on first hearing. The accompaniment of “Pause” evokes the lute, much of it unfolding so independently of the voice, mostly within the middleground, that the latter gains a distant, lost-in-thought quality indicative of the character’s reverie. Yet on three occasions (see mm. 33–35, 53–55, and 63–69), the piano part of “Pause” defers to the voice by retreating into the background, supporting brief recitative-like spans that suggest clear-minded thought. And while the accompaniment of “Mit dem grünen Lautenbande” also evokes the lute, its closer relationship with the foregrounded vocal line gives the Lied a more retrospective, even archaic quality, as if the young man had imagined himself somewhere in ages past. In contrast, the continuously-reiterated f♯ʹ of “Die liebe Farbe,” a persistent, even obsessive textural detail in the background, contributes to that song’s striking immediacy and savage irony. The series of changing and contrasting two-measure textural units within the first third of “Die böse Farbe” surely suggests internal anxiety – through texture we sense restlessness and anger. Finally, the inner-voice motion through most of “Des Baches Wiegenlied” surely portrays the murmuring and gentle flow associable with a lullaby, and because of its melodic independence, seems to reside in the middleground. Yet the compound perfect fifths and perfect octaves, expressed via half notes in mm. 1–15 and 20–25 within the background, are no less important to the closing Lied’s effect. Indeed, they produce an ambient spatiality unlike any heard earlier in the cycle, perhaps providing a hint of the journeyman’s repose. We sense some of what the fellow would seem to perceive through texture within the middlegrounds and backgrounds of Die schöne Müllerin. Winterreise exploits texture similarly.

However, the middlegrounds conveyed by the piano within Schubert’s second song cycle may seem even more teeming and individuated than those of Die schöne Müllerin. Their contents may change frequently and unpredictably, interacting with their foregrounds while maintaining considerable independence. Indeed, at times the middlegrounds of Winterreise even seem to provide competition with and distraction from the voice. Curiously, this seems to increase our focus on the Lied’s texted content and its nuances in the foreground. Engaged by the compelling narrative, the rich content, and Schubert’s intriguing style, we lean in. Remarkably, this seems to enhance our engagement and intensify our identification with the wanderer. Let’s examine evidence with illustrations.

Consider Example 9.3, a selective excerpt drawn from “Gute Nacht,” the first Lied of Winterreise, that presents essential foreground and middleground elements from an early span.

Example 9.3 Winterreise, “Gute Nacht,” mm. 15–26 (selective excerpt)7

As this suggests, separate accompanimental strands, each with its own melodic integrity, compete with the voice for our attention. The contrapuntal web they create with the foregrounded vocal melody places demands on the listener similar to that of fugue. Here, the aural portrait would seem to reflect the soon-to-be wanderer’s internal debate and anxiety as he prepares to leave. Our aural filtering here provides an analogous experience.

In Example 9.4, a full-content excerpt drawn from “Irrlicht,” the ninth Lied of Winterreise, the piano’s music certainly defers to the voice, yet is so individuated, as well as interactive with its more prominent partner, that their sum seems to represent concurrent dialogue.

Example 9.4 Winterreise, “Irrlicht,” mm. 17–288

Here, the registrally shifting, distinctively articulated, texturally fluctuating, and orchestrally conceived piano part – much of which sounds higher than the tenor voice – attracts so much attention to itself in the middleground, that we must apply considerable concentration just to follow the quickly unfolding and densely expressive text. In this passage, which presents the second stanza of Müller’s poem, we’re able to share the wanderer’s perception of the darting will-o’-the-wisp as well as his recognition of its correspondence to the randomness of Fate. Our aural experience offers a hint of the journeyman’s visual experience.

In “Letzte Hoffnung,” the first vocal phrases almost seem to unfold in a separate channel, enveloped by metrically ambiguous activity in the middleground. Example 9.5 illustrates this.

Example 9.5 Winterreise, “Letzte Hoffnung,” mm. 4–159

A listener’s ear is attracted from register to register in this span as the voice’s largely conjunct line holds sway. Capturing the wanderer’s visual observations and internal musings about the fate of leaves whipped by the wind and about to fall from their trees, which strike him as parallel to his own, this music demonstrates Schubert’s profound understanding of human psychology as well as any other in Winterreise.

Contrary to what one might imagine, increased textural complexity in Schubert’s Lieder seems to engage and intrigue more than it deters or fatigues, and this may have something to do with the composer’s personal style, which seems endlessly innovative and intrinsically evocative. However, his music also elicits expectations whose fulfillment is less immediate and more cumulative. Let’s look closer.

Contextual Processes and Identification in Schubert’s Song Cycles

Contextual processes – structural sequences that generate anticipation in advance of a climactic fulfilling event – appear more commonly in Schubert’s music than one might imagine.10 Within Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, contextual processes enhance identification in intriguing and idiosyncratic ways as they contribute to perceptions of momentum and unity.11 Let’s observe several.

For instance, certain contextual processes feature a gradually ascending vocal ceiling.12 In “Wohin?,” the second Lied of Die schöne Müllerin, the initially highest vocal pitch, notated as dʺ in m. 3, soon is exceeded by the notated eʺ in m. 13, which later is surpassed by the notated f♯ʺ in m. 33.13 But the then-expected gʺ that would complete this rising perfect fourth and resolve the leading tone in the voice of m. 33 waits until m. 71, just ten from the end. During this span, sensitive listeners experience their own subliminal expectation that parallels the uncertainty being conveyed by the character of the journeyman, portrayed by the singer, who describes being led along by a babbling brook, unsure where he is going, only to realize near the Lied’s conclusion that the water may be guiding him to another mill. Complemented by other musical factors, of course, this rising registral ceiling adds to the Lied’s dramatic momentum while encouraging listeners to identify with the character’s anticipation.14

In the next Lied, “Halt!,” an ascent from a notated eʺ in m. 12 to an fʺ in m. 16 would seem to have stalled by m. 35 with a repetition of that fʺ. However, the pitch gʺ, reached in m. 40 and reiterated in m. 44, enables a coincidence of the vocal line’s apex with the word “Himmel” (sky). There within the text’s narrative, a shining sun seems to confirm that the millhouse where the still-searching young man has stopped is where he was meant to be. As listeners, we experience an arrival effect contributed in part by this rising vocal ceiling.

And in the seventh Lied of Die schöne Müllerin, “Ungeduld,” an even more anxious and agitated stepwise rise in the vocal ceiling from a notated c♯ʺ (m. 9) to dʺ (m. 11) to eʺ (m. 13) to f♯ʺ (m. 14) to g♮ʺ (m. 15) and – after a bit of a delay – finally to aʺ (mm. 21, 23), conveys the fellow’s waves of impatience that unfold over the four verses. In these songs from Die schöne Müllerin, rising vocal ceilings elicit subtle effects of anticipation and arrival, portraying the persona’s interiority via expectations whose fulfillment we may share.

Contextual processes founded on rising vocal ceilings communicate interiority within Winterreise too. For instance, in “Letzte Hoffnung,” a gradual ascent involving the notated pitches c♭ʺ, cʺ, dʺ, (e♭ʺ’s skipped!), fʺ, g♭ʺ, and gʺ communicates the height of anguish as the wanderer speaks (via the singer!) of weeping on the grave of his hopes as he waits to see if a leaf will fall. And in “Der Wegweiser,” a determined rise over a longer span involving the sequence gʹ-aʹ-b♭ʹ-cʺ-dʺ-eʺ-g♭ʺ(=f♯ʺ)-gʺ reaches its height in m. 52 as the character speaks of wandering on relentlessly and restlessly, seeking yet not finding rest. There the final pitch sounds over a climactic cadential six-four, never to be stabilized through harmonization by the tonic triad within the space of the song. We, as listeners, can identify with the wanderer’s anxiety through our own unfulfilled expectations, since the resolution of the song’s expansive ascent only may be imagined over a later instance of the tonic triad.

Certain other rising vocal ceilings, including those in “Die Wetterfahne” and “Gefror’ne Tränen,” fade without ever reaching climactic arrivals at anticipated tonic triad tones in the voice. Similarly, all four sections of “Die Post” seem to suggest that the voice eventually will achieve the notated pitch gʺ – the third of the E♭ major tonic triad – yet the goal remains tantalizingly out of reach. Frustrating expectations to communicate impressions of inadequacy, these ascents underscore the cycle’s narrative as they reflect the wanderer’s dejection. It would seem that, following Die schöne Müllerin, Schubert continued to explore the expectation-engendering potential of rising registral ceilings in Winterreise, creating ever more subtle instances that communicate frustration felt by the wanderer by not providing anticipated arrivals within the music. Along with the matters of form and texture, it seems clear that much remains to be discovered regarding Schubert’s rising registral ceilings, as well as his incorporation of contextual processes more generally.

A master of manipulating his listener’s responses, Franz Schubert employs subtle musical means in his song cycles to enable us to sense emotions and reactions similar to those portrayed by his characters. If we’re engaged, we identify with them even more through what we perceive as shared experience. In turn, our immersion within his narratives is all the more vivid.15

Afterthoughts

Perhaps the most admirable achievements of Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise are their persuasive prompts to sympathize and empathize with their central characters. Each encourages us to descend deeper into our own imaginations and reflect upon our own responses to their stories. In turn, these masterpieces may be interpreted as entreaties to become more sympathetic and empathetic human beings. Within today’s turbulent world and dimming future, such sensitivity seems in short supply. Indeed, the pleas for compassion within Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise may be among the greatest legacies of Franz Schubert’s Romanticism.

This chapter explores Schubert’s Winterreise from a number of angles. First, under the heading of “Connecting Threads,” I consider overarching elements in text and music. Text and music do not necessarily coincide in all dimensions (such as their timeframe, or their structure), but may gain added power from being non-congruent. Secondly, I examine Schubert’s deployment of the “fingerprints” of his personal style: these too contribute to the intense impact of Winterreise.1 In setting the twenty-four poems of the finished cycle, Schubert not only created an alliance between music newly conceived for the purpose and Müller’s words; he also, importantly, formed an alliance of the words with core features of his compositional style at a ripe stage of its development.

In highlighting the detail of Schubert’s settings, I identify in some songs what I call the “crux,” containing the nub of what is expressed in the poetic text. Where the musical response to the poetry coincides with the crucial words uttered by the voice, such examples are among the most powerful in this category. Under various headings, I pinpoint specific topical references that help form the fabric of text and music.2 The intricacy of that combined fabric means that only a selection of examples can be discussed in detail. Table 10.1 provides an overview of all twenty-four songs for reference.

Table 10.1 Overview of text and music

| Song number/ Title | Key/Tempo | Mood/Musical topics | Motifs/Devices (text) | Motifs/Devices (music) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gute Nacht (Good Night) | d / Mässig | Somber/slow march; hymn-like (F, B flat); dreams (D) |

| Drone/trudging footsteps; neighbor-note motif (“x”); falling third motif (“y”); falling fourths; arpeggiation; minor/major |

| 2 Die Wetterfahne (The Weathervane) | a / Ziemlich geschwind | Ominous; grotesque; dance (Konzertstück) | Wind blowing; her house; mockery; faithlessness | Arpeggiation; trills; motif x; chromatic thread; minor/major |

| 3 Gefror’ne Tränen (Frozen Tears) | f / Nicht zu langsam | Grotesque march; Viennoiserie/dance; recitative | Tears falling; ice/heat; his heart | Semitonal motif; aug./dim. intervals |

| 4 Erstarrung (Numbness) | c / Ziemlich schnell | Antique style/canon, augmentation (mm. 26 ff.) | Ice and snow; frozen/melting; tears; his heart; past/present/memory | Motif x; moto perpetuo; chromatic threads; cadential delaying (v. 2); Neapolitan figure |

| 5 Der Lindenbaum (The Linden Tree) | E / Mässig | Hymnlike (E); storm; lullaby | Linden tree; dreaming; love; wind blowing | Major/minor |

| 6 Wasserflut (Flood Water) | e / Langsam | Slow quasi-march/dirge; lullaby | Ice and snow, wind; burning, melting; tears; her house | Arpeggiation; cadential delaying |

| 7 Auf dem Flusse (On the River) | e / Langsam | Slow march; antique style; lyrical (central episode) | [Water] rushing/still; past/present; memories; his heart | Partimento-type bass; remote modulations; motif x; minor/major |

| 8 Rückblick (A Look Backward) | g / Nicht zu geschwind | Impulsive motion (vs. 1 & 2, v. 5 ); fragility/ lullaby (vs. 3 & 4) | Ice and snow; birds, linden trees; past/present; inconstancy; her house | Rocking octaves; chromatic threads; motif y; hemiola; minor/major |

| 9 Irrlicht (Will-o’-the-Wisp) | b / Langsam | Grotesque march | Illusion (ignis fatuus); mockery; the grave |

|

| 10 Rast (Rest) | c / Mässig | Dirge/antique style/ground; “folk” style (voice, vs. 1, 3) | Freezing/burning; storm; his heart | Chromatic threads; cadential delaying |

| 11 Frühlingstraum (Dream of Spring) | A / Etwas bewegt/Schnell/Langsam | Musical box/ Viennoiserie/dance; dreams; grotesque; lullaby | Dreaming/awakening; birds; illusion; his heart | Motif x; dissonance; rocking octaves; major/minor |

| 12 Einsamkeit (Solitude) | b / Langsam | Dirge, “folk” style; storm (v. 3) | Alienation; gentle breeze/raging storms | Drone/slow footsteps; accompanied recit. |

| 13 Die Post (The Post) | E flat / Etwas geschwind | Horn calls (posthorn) |

| Moto perpetuo |

| 14 Der greise Kopf (The Old Man’s Head) | c / Etwas langsam | Antique style/ground; recit. (v. 2) | Illusion; frost/melting; death | Arpeggiation/ dim. sevenths |

| 15 Die Krähe (The Crow) | c / Etwas langsam | “Folk” style (v. 1, v. 3 ll. 1–2) | Faithfulness; the grave | Moto perpetuo; motif x; drama (v. 2, v. 3 ll. 3–4) |

| 16 Letzte Hoffnung (Last Hope) | E flat / Nicht zu geschwind | “Pizzicato”-style acc.; aria (v. 3, final line) | Wind/fall of a leaf; loss of hope | Arpeggiation/ dim. sevenths; semitonal motif; major/minor |

| 17 Im Dorfe (In the Village) | D / Etwas langsam | Hymn-like/antique style (final line) | Barking dogs; dreams; alienation | Tremolo figuration; 4-3 suspensions; Mozartian buffo style |

| 18 Der stürmische Morgen (The Stormy Morning) | d / Ziemlich geschwind, doch kräftig | March; theatricality/impulsiveness | Extreme weather; his heart | Arpeggiation/dim. sevenths; Neapolitan figure (v. 3 ll. 3–4) |

| 19 Täuschung (Illusion) | A / Etwas geschwind | Waltz/Viennoiserie /barcarolle | Illusion; ice; warm house/beloved soul | Ostinato; motif x; chromatic thread |

| 20 Der Wegweiser (The Sign Post) | g / Mässig | Dirge; antique style incl. “lament bass” and “wedge,” chant (v. 4) | Isolation; death | Trudging footsteps; chromatic thread; remote modulations; Neapolitan figure |

| 21 Das Wirtshaus (The Inn) | F / Sehr langsam | Hymn-like, slow march | Mortally wounded (v. 3, l. 4); the graveyard (“no room at the inn”) | Motif y; dactylic figure; major/minor incl. echo (v. 3, l. 4) |

| 22 Mut (Courage) | g / Ziemlich geschwind, kräftig | March/“folk dance” | Defiance; snow/wind; his heart; singing | Major/minor |

| 23 Die Nebensonnen (The False Suns) | A / Nicht zu langsam | Hymn-like, antique style/sarabande | Illusion; death wish | Major/minor |

| 24 Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man) | a / Etwas langsam | “Folk” style; grotesque lullaby | Ice; dogs growling; traveler/musician; singing | Drone; ostinato |

Key

Acc. = accompaniment; Capitals for major, lower case for minor keys; aug. = augmented; dim. = diminished; l. = line, ll. = lines; v. = verse, vs. = verses. In “Mood/Musical topics,” “Konzertstück” indicates “brilliant” topic (virtuoso display); “Viennoiserie” denotes stylised Viennese dance figures. In “Motifs/Devices (music),” “chromatic thread” refers to the melodic line; “minor/major” (or vice versa) is indicated only in cases of parallel rather than relative keys; “motif x” refers to its original or inverted form; “Neapolitan figure” is the three- or four-note motif with flattened supertonic and leading-note turning around the tonic note or flattened sixth and augmented fourth turning around the dominant note.

We might pause to consider the characters peopling the narrative of Winterreise. The cycle is remarkable in its intensive focus on the protagonist, so that as listeners we may feel almost as if we experience something of the hardship he goes through on his journey. The landscape itself is a quasi-figure in the narrative, its features vividly delineated; its presence is constantly impressed on our senses, as it is on the protagonist’s. In a work founded on paired opposites, this strenuous winter’s journey represents a negative version of the Grand Tour (in the sense of a photographic negative). In place of the kind of Bildung whereby the traveler on the Grand Tour absorbs the culture of the wider world beyond his own experience, the landscape traversed by the protagonist in Winterreise makes his awareness turn inward onto his private feelings and experiences.3

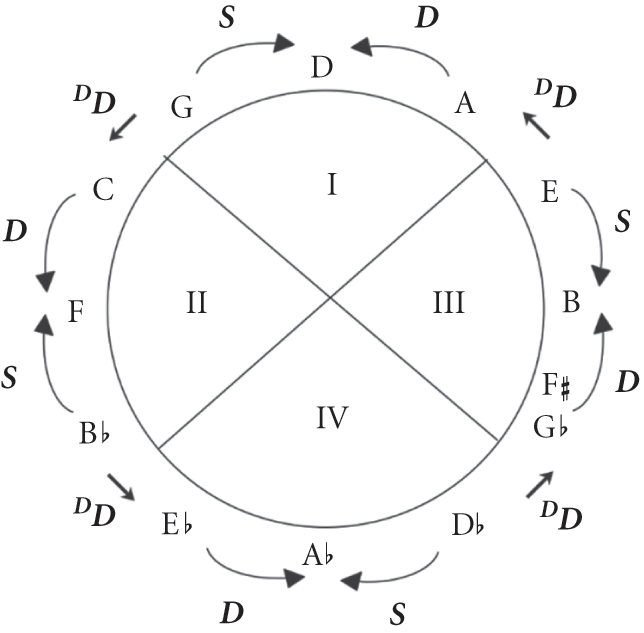

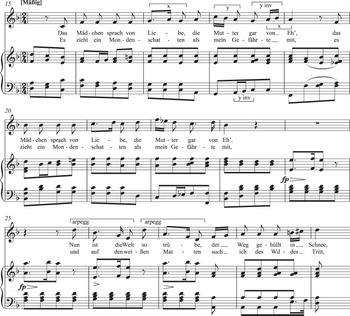

Other characters are figures from the past: the girl he longs for, her mother, and by implication her father, and the bridegroom who has replaced the protagonist in her affections. Those telling lines in “Gute Nacht,” “Das Mädchen sprach von Liebe, / Die Mutter gar von Eh’” (The girl spoke of love, / Her mother even of marriage), accompanied in the music by the turn to the relative major, have the power to remain imprinted on our minds. Indicative of a poetic thread running through the cycle, their import is full of hope, yet weighted with the danger of hope’s defeat. We might recognize their echo in “Die Post” at the start of Part II, when the sound of the posthorn raises hopes doomed to be betrayed. There too Schubert matches the opposing states by contrast of mode, in the parallel minor at the start of verse 2 where the traveler imagines that the post brings him no letter.4

While the girl and her family remain in his memory, the only other characters introduced during the course of the winter journey belong to the present rather than the past. First of these is the charcoal-burner in “Rast,” whose cramped home the wanderer enters for shelter. This character apparently exists only in absentia, or – if he is in residence – as a silent and unseen presence.5 The hurdy-gurdy man introduced in the final song (“Der Leiermann”) provokes speculation as to whether he represents an illusory or a real figure, and whether he functions literally as a traveling performer, or symbolically as a manifestation of Death. The Leiermann’s instrument suggests that he could represent an immigrant, set apart, like the protagonist. Susan Youens characterizes him as the protagonist’s Doppelgänger, a figure traditionally taken to be a premonition of death;6 this chimes with the duality in the constructions of both text and music throughout the cycle.

Connecting Threads

Arguably the most fundamental element linking text and music across the cycle is the intimation that the central figure is a musician. His appeal to the hurdy-gurdy man in the final three lines: “Soll ich mit dir geh’n? / Willst zu meinen Liedern / Deine Leier dreh’n?” (Shall I go with you? / Will you play your organ / To my songs?), can be taken as an indication of the protagonist’s calling rather than as metaphorical. Ian Bostridge has explored the traveler’s possible status as a music tutor in the girl’s household, while emphasizing Müller’s wish to avoid defining the character too precisely.7 Further indication is planted in “Mut!,” where the protagonist sings in defiance of the harsh conditions through which he journeys (and the depressive side of his own feelings): “Wenn mein Herz im Busen spricht, / Sing’ ich hell und munter” (When my heart speaks in my breast, / I sing loudly and gaily).

Another overarching element is the intensity with which the poet’s words portray the winter journey. The effects involved include extreme contrast and the evocation of startling images. Schubert’s setting creates a comparable intensity from across the spectrum at his disposal, including rhythmic profile, melodic shaping, motivic usage, harmony, texture, dynamics, relationship of voice and piano, and function of the piano accompaniment. All these, overlapping with topical reference, have the power to convey what words alone could not achieve, and to enhance or affirm what the words express. Additional details such as a specific contrapuntal device, or fragment of word-painting, can throw a spotlight on the text at individual moments.

Used in these ways, the music may add to the text Schubert’s personal reading of it, especially where the poet has created ambiguity or uncertainty rather than giving explicit definition to his ideas. In “Gute Nacht,” where the girl speaks of love and the mother “even of marriage,” with the move from the tonic minor to the relative major and then into its subdominant (see Example 10.1, mm. 15–23), Schubert allies the major mode with a diatonic chordal style of hymn-like serenity.8 This passage gains a touching hopefulness, expressed musically in the upwards reach of the melody and its sequentially related phrases. Notably absent from Schubert’s setting here is any trace of the bitterness associated with the betrayal that followed those promising signals from mother and daughter. Schubert’s music recaptures the moments of pure hope, untainted by hindsight.

Example 10.1 “Gute Nacht,” mm. 15–299

That excursus into the major throws into sharper relief the return to the tonic minor for the ensuing lines: “Nun ist die Welt so trübe, / Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee” (Now the world is so gloomy, / The road shrouded in snow). Here Schubert’s repeat of the paired lines is unable to move in key, remaining mired in the protagonist’s mood and the surrounding scene. In both text and music, “Gute Nacht” prepares us for many other instances where references to past happiness and comfort are contrasted with present hardship and misery. Schubert’s musical treatment gives love remembered a distinctive profile, as he does variously with the other main themes of Winterreise: loss, loneliness, death, and the winter journey itself. “Gute Nacht” introduces elements in both words and music that will be fundamental to the cycle as a whole.

Altogether a sense of the magnitude of the protagonist’s situation, and of the epic journey he undertakes, issues from the cycle in both text and music. The prolonging of harmonic progressions, as in “Rast,” at the matching ends of verses 2 and 4 in each paired set of verses, corresponds to the prolonged agony the wanderer carries with him. The extended diminished seventh chord heard at mm. 21–23 (see Example 10.2) and again at mm. 51–53, prefacing the approach to the cadence, is exploited for its disturbing properties. Its configuration, with notes crowded low in the piano accompaniment, together with the dissonant appoggiaturas in the voice (arrowed on Example 10.2), contributes to the harsh, grinding effect.

Example 10.2 “Rast,” mm. 20–31

Within each of these passages, the harmony is twice denied resolution before it is accomplished. Delay first sets in with the prolongation of the diminished seventh beyond normal expectations (as indicated on Example 10.2). An escape route is offered by the move to an augmented sixth (marked on the example in m. 23), with potential to trigger the cadential progression towards closure; but the music stalls, forming an interrupted rather than perfect cadence at m. 25. Only after a varied rerun, to a repeat of the last two lines of text, now prolonging the augmented sixth harmony (at mm. 26–29), does it finally resolve in a perfect cadence. In tandem with these proceedings, the vocal line soars beyond the confines of its contours earlier in the song. Schubert adds a tiny, affecting detail to the vocal part in the final version of the passage, inserting an anticipatory note at m. 55, before the upwards resolution of the appoggiatura on the word “regen” (stir).

These tactics lift the music of “Rast” above the level of the quasi-folk style with which Schubert delineated the humble scene in the vocal melody at the start. (That folk-like idiom forms another recurrent feature of the cycle, matching the equivalent element in Müller’s poetry). At the same time, and a measure of Schubert’s mastery, the disruptive surface created here rests on an underlying harmonic logic. Schubert’s dynamics add to the dramatic effect. He marks pianissimo for those uncertain approaches to the cadence, poised in each case on an enigmatic chord. Forte is marked for each of the postponed cadential resolutions, where in verse 2 the storm blows the traveler uncomfortably, even dangerously, along (a sensation he later tells us he welcomes), and where in the painful closing words of the final verse, his heart burns with the serpent that stirs within his breast.

At the opposite end of the spectrum from this drawn-out effect is the sudden stab of pain, as in “Wasserflut” towards the end of verse 1 in the repeated double-verse setting. After climbing precipitately through a tenth (m. 11), the vocal line seems to overshoot its target. What could have been the expected end of the phrase, on the E, is harmonized not with the tonic chord but with a dominant seventh of A minor transformed to a diminished seventh, against which the voice utters an anguished cry (m. 12) on the word “Weh” (woe). The melisma here, tracing the interval of a descending minor third over the sustained dissonant harmony, leaves the music open, responding to the sound of the word, which with its soft ending rather than hard consonant leaves the line of poetry similarly open-ended. (This plangent minor third was predicted at the start of the cycle in the opening three notes of the piano’s RH melody, echoed in the voice, filling in the interval stepwise in what constitutes the recurrent motif marked “y” in Example 10.3.) Schubert’s sensitivity to what Stephen Rodgers has referred to as the “sonic dimension of poetry” is a feature in evidence throughout D911.10

Example 10.3 “Gute Nacht,” mm. 1–11

In “Wasserflut,” with the ensuing repetition of the text, the vocal line plummets towards closure (mm. 13–14), a gesture that can be seen as reflecting the traveler’s volatile mood. At the end of the second half, the vocal line achieves closure on the e″ but approaches it differently, in a passage marked forte. With these strongly projected passages we can imagine the wanderer shouting into the snow-covered landscape as he conjures up first a vision of the snow melting away (verse 2), and finally his hot tears flowing with the brook past his beloved’s house (verse 4). Throughout the cycle Schubert uses the directional curve of his melodic lines (sometimes, as here, looping round as they climb up or plunge down) to dramatic effect. In “Der greise Kopf,” the piano introduction is launched with a precipitate ascent, followed by an abrupt descent tracing the outline of a diminished seventh, a harmony that resonates through the cycle. It featured as the first dissonant harmony at the opening of “Gute Nacht,” associated with the semitonal fall formed by the first two notes of motif y′ (see Example 10.3, m. 2). That two-note fragment creates the lamenting “sigh” figure noted by Youens; it too threads its way through the songs.

Unexpectedly, in “Der greise Kopf,” the voice takes up the piano’s sweeping opening gesture, peaking a third lower. This unlocks the theatrical character of the music that follows. Its expressive zone, drawing on the language of recitative, matches the drama enacted in the words. The traveler thinks jubilantly that he has grown old suddenly, and is horrified to realize that the white sheen spread by the frost over his hair has melted away. This strange reversal of the wish to stay young, resisting the encroachment of old age, is destabilizing and yet understandable in the context of his longing for death. The build up to the crux at the words “Wie weit noch bis zur Bahre!” (How long still to the grave!) is couched in the ominous chromatic language with which Schubert portrayed elements of plot and character in his early dramatic Lieder.11 More ominous still is the octave/unison texture that follows in piano and voice for that crucial line where the traveler contemplates the grave.

Allied to the intensity felt in both text and music at a single moment is the prevailing sense of obsessiveness and circularity characterizing the protagonist’s pronouncements as he reflects on his condition. Schubert’s setting produces an equivalent to this poetic trope. The devices of ostinato and moto perpetuo, hallowed by centuries of use and finding new life in the nineteenth-century Lied, are exploited to this purpose throughout Winterreise (see Table 10.1 for songs employing the techniques). Schubert draws on them in a myriad of ways. (Examples discussed under the heading of “Topical Genres” below include “Gute Nacht” and “Wasserflut”.)

Besides its psychological implications, circularity serves in Winterreise to reinforce the work’s cyclic status, linking individual songs more than casually within the whole structure. Schubert’s compositional choices enable the music to support this element in the poetry, as well as building a strong overall structure in itself. At its most readily perceptible, this process operates where melodic and rhythmic figures heard at the end of one song are picked up at the beginning of the next. As Bostridge puts it, these connections create “an elective affinity between certain songs (the way the impetuous triplets of “Erstarrung” segue into the rustling triplets of “Der Lindenbaum” … [and] the repetitive … dotted figure of the last verse of “Lindenbaum” is transmuted into the opening of “Wasserflut”).”12

Schubert’s Fingerprints

By the time of writing Winterreise, Schubert had the elements of his style well-honed and readily at his disposal. Traces of intertextuality are threaded through in tandem with these Schubertian “fingerprints.” They range from the innermost connections within the cycle through analogies with others of his Lieder; further across his oeuvre to parallels with his instrumental and sacred vocal works; and also, beyond all those, to echoes of other composers. Mozart is in the background to Schubert’s music throughout his oeuvre. Mozartian echoes in Winterreise include the repeated-note patter (on the note D) in “Im Dorfe” at mm. 19–23, with the playful vocal interjections against it, and the bass in parallel with the voice, which sounds like a passage from the Act II finale of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro.13 The choice of key for a song also sets up associations. By Schubert’s time, the key of “Gute Nacht,” D minor, carried with it an aura of tragedy, horror, and death from its usage in opera and requiem: Mozart again comes to mind.

Beginnings and Endings

Schubert invests the opening and closing music of Winterreise with special significance. Songs 1–5 and 20–24 provide in many respects a microcosm of the cycle. The two bookends (songs 1 and 24) resonate with each other, possessing musical figures rich with import. As Youens put it, the closing measures of “Letzte Hoffnung” present a “gesture with a history that begins in the first measures of the cycle.”14 This certainly applies to the final song. The drone bass at the start of “Gute Nacht,” with its topical reference to rustic culture, evokes the traveler’s footsteps as he trudges across the wintry landscape. In retrospect it can be seen as prophesying the hurdy-gurdy man’s music at the end of the cycle. (As commentators have noted, Schubert plants references to it in the intervening songs.)15 Heard in the opening measures of “Gute Nacht,” this trudging drone has an inexorable quality reflecting the traveler’s intense compulsion to embark on the journey. In one possible reading of the final song, it may indicate the transformation of his journey into a life of eternal wandering.

Within the casing formed by the songs at start and finish, each individual song contains a sharply drawn vignette, in some cases focusing more steadily on a particular scene, in others more hectically dramatic, and typically framed by both piano introduction and postlude. As Youens notes, only one song, “Rückblick,” lacks a postlude.16 The purposes to which these textless opening and closing passages lend themselves are rich with possibilities in relation to structure and expression. When the piano postlude in “Gute Nacht” echoes the voice’s closing phrases, where the traveler wants his beloved to know he thought of her as he departed (“an dich hab’ ich gedacht”), those echoes in the piano are placed in an inner voice within the trudging chords, as if to indicate the persistence of her presence deep in his mind. They convey his ambivalence: while he knows he must leave, he nurtures an abiding reluctance to part from her.

These psychological implications resurface later, for instance in “Rückblick,” where at the end he wants to stand still outside her house (hence, as Youens observes, the lack of a piano postlude, since the music too must stand still).17 Here the crux comes at the end (as in “Erlkönig,” D328): the ensuing silence, shorn of a postlude, is telling. Those last wishful thoughts the protagonist expresses contain the seeds of what would now be called stalking; the urge remains in his imagination, where it contributes to the burden of emotional pressure he carries. The words and music at the end of “Rückblick” tell us that he has not yet managed to separate from her psychologically. When he does so, in Part II (which, as commentators have noted, remains free of direct reference to the beloved after the first song, “Die Post”), it is a sign that his obsession with her has been replaced by an equally strong fixation on a desire for death. The words of Death personified in Schubert’s “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (D531) come to mind, when he reassures the maiden that he comes to comfort and not to punish her. The traveler in Part II of Winterreise, contemplating death, pleads that he is not deserving of punishment: “Habe ja doch nichts begangen, / Dass ich Menschen sollte scheu’n” (I’ve committed no crime / That I should hide from other men).18 The songs towards the close, bringing to the fore intimations planted earlier, suggest that his hopes are increasingly fixed on the release from suffering offered by eternal rest.

Motivic Networking

From the start, with “Gute Nacht,” Schubert’s characteristic fashioning of melodic lines from a few intervallic cells helps to give the opening measures an intensity that not only sets up the mood of the whole cycle, but also introduces significant motivic elements. The motifs packed into those measures suggest in miniature a kinship with the principle of “developing variation” that has been attributed to Brahms.19 The falling fourths (numbered on Example 10.3) already contained in the continuation of motif y and its variant form y′, are detached in mm. 4–5, then heard in diminution and filled-in at m. 52. Schubert’s song melodies, far from spreading luxuriantly, tend to make economical use of tiny seeds that grow into a unified yet variegated line.

The genre of song cycle lends itself to the creation of a network of motivic material linking individual songs and responding to the intertextuality within the poetic sequence.20 While a motif may not necessarily be associated with the same or similar poetic ideas on its recurrence, there may be a shared poetic context among its appearances. A particularly prominent Schubertian fingerprint heard at the beginning of Winterreise is the palindromic neighbor-note motif (marked “x” on Example 10.1) which, together with its inverted form, recurs in voice and piano throughout “Gute Nacht.” The motif is found among songs from earlier in Schubert’s life. The obsessive quality that infuses his remarkable setting of “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (D118; 1814) derives partly from its use in both the spinning piano accompaniment and the vocal line, in its original (here with lower neighbor-note) as well as its inverted form, throughout. Among a plethora of examples in the instrumental works, the late string quartets show a similarly obsessive use of this motif. In Winterreise, its occurrence in a variety of contexts mirrors the protagonist’s obsessive musings at different stages of his journey (see Table 10.1, shown as “motif x”).

Major–Minor Juxtapositions

The most familiar major–minor effect, the echo, where a passage in the major is repeated in the parallel minor (or vice versa), has the power to transform mood as well as mode. This is but one of an array of devices along the spectrum Schubert explored with regard to modal mixture. In his Lieder, he used the major–minor echo with sensitivity to the implications of a variety of textual prompts.21 Some of its most powerful manifestations occur with the reverse Picardy third, a Schubertian specialty (inherited by Brahms) whereby after apparently signaling closure, the major is followed by a minor resolution, as in two of D911’s “dream songs”: “Gute Nacht” and “Frühlingstraum,” conveying the return from the dream-world (or thoughts of it) to reality.

During the course of a song, Schubert’s injection of major into minor-key surroundings ranges from a brief flash of color (as occurs towards the end of “Die Wetterfahne”) to an extended section, as in verse 7 of “Gute Nacht.” Its adaptability as an emotional signifier ranges from the bitter resentment expressed in the final lines of “Die Wetterfahne” (“Was fragen sie nach meinen Schmerzen? / Ihr Kind ist eine reiche Braut.” [Why should they care about my grief? / Their child is a rich bride.]) to the tenderness with which the music in “Gute Nacht” suggests that the traveler imagines her sleeping and dreaming.

Variations and Transformations

In Schubert’s songs, as well as his instrumental works, variation principles at their most sophisticated reflect his vision of a range of possibilities operating at different levels of the music.22 Among the song-structures Schubert builds (exercising some flexibility in relation to Müller’s verse structures), the modified strophic form (as in “Gute Nacht”) and bar form (AA′B, as in “Irrlicht”) can accommodate variations in voice and piano responding to nuances, or more extended changes of mood, in the text. This applies also to more freely built song forms possessing an element of refrain, such as those in “Die Wetterfahne” and “Der Lindenbaum,” with their varied treatment of the recurring passages.

Among Schubert’s characteristic ploys is the playfulness he brings to varying his material. In Winterreise, this is manifested not in the lighter vein of such works as the “Trout” Quintet (D667), but in cruel travesty. The trickery that characterizes the ignis fatuus in “Irrlicht” is established at the start in the piano introduction with its consequent at mm. 3–4 mocking the falling fourths of mm. 1–2. That falling fourth motif is subjected to further mockery in the voice’s entry, first with the dotted rhythm developed into a kind of anti-march figure at m. 5, filtering into a grotesquely leaping figure in m. 6; then on its next appearance turned into a misshapen diminished fourth (m. 9). These proceedings constitute a distortion of Schubert’s customary practice of echoing the piano’s introductory melody in variant form in the voice’s first entry (as in “Gute Nacht,” to the enrichment of the motivic network). In “Irrlicht,” what follows in m. 11 distorts the arpeggio figure from mm. 25–26 of “Gute Nacht.” It is as if in his febrile state the traveler takes on something of the character of the Irrlicht as he describes its effect on him. In the verses that follow, Schubert develops the bar form, featuring a variant A section for verse 2; the B section for verse 3 responds with a new, profound seriousness to the text (its crux in the final lines introducing the first reference to the grave in the cycle). The piano postlude allows the Irrlicht to have the last word.

Like the musical motifs, recurrent motifs in the poetic text appear in different contexts. The memory of the “green meadow” through which the protagonist walked with his sweetheart, recalled in “Erstarrung,” verse 1, triggers a move to the relative major (E♭) at mm. 20–23. His (fruitless) wish in verse 3 to recapture it (“wo find ich grünes Gras?”) again triggers a passage in a related major key, this time the submediant (A♭). “Frühlingstraum” allows him the idyllic vision of green meadows in his dreams, set in a brightly configured A major. The color green appears transformed in Part II. In “Das Wirtshaus,” instead of the association with happier memories of lush meadows, he sees green wreaths (“grüne Totenkränze”) as a sign inviting him into the graveyard: the setting moves at this point from F major into G minor, as it did at the beginning of the song when his steps turned towards the graveyard.

A particular Schubertian speciality is the transformation of lyrical into dramatic and violent expression, found among the late instrumental works at its most extreme in the slow movement of the A Major Sonata (D959).23 In Winterreise, this aspect of the music, like Schubert’s major–minor juxtapositions, is harnessed to Müller’s penchant for binary constructions. In verse 1 of “Frühlingstraum,” the idealized dream scene painted by the poet is matched by the artificiality of the Viennese waltz, fashioned in music-box style, its only chromatic touch a fleeting neighbor-note decoration. Birds reappear grotesquely transformed, when the twittering creatures incorporated gracefully into the opening section’s dance topic find their alter egos in the stormy B section that follows, with the harsh cockcrow, and the ravens shrieking from the roof, marking the abrupt awakening from the dream. Here the elegant neighbor-note motif associated with major-key sweetness in the opening section is embedded within the language of dissonance and distortion, as the music rises hectically in pitch and volume.24

Topical Genres: March, Dance, and Lullaby

Schubert’s contribution to the genres of march and waltz belongs largely to the sociable, popular side of his oeuvre.25 Their infiltration into the late chamber and piano works involves the expression of darker moods. In Winterreise, too, they take on a sinister character. The pressure on the protagonist to pursue his journey, reinforced musically by the recurrent march topic initiated in “Gute Nacht,” and poetically by the winter imagery, has echoes in the forced marches made throughout history. Also recurrent is the dirge or funeral march topic, linked with oppressive ostinato patterns and antique style, and evoked in a variety of contexts, ranging from “Wasserflut” to “Der Wegweiser” (see Table 10.1). The Viennese waltz topic characterizing the A sections of “Frühlingstraum,” with its air of unreality, extends to grotesque effect in “Täuschung,” where it persists manically throughout the song, prefiguring the glittering ball scene in the same key in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, and confirming the sentiment that concludes Müller’s text: “Nur Täuschung ist für mich Gewinn!” (Only illusion lets me win!).

Besides the handful of songs Schubert produced under the title of “Wiegenlied” (Cradle Song) or “Schlaflied” (Lullaby), this topic is discernible in numerous others of his Lieder. While the final song of Winterreise (“Der Leiermann”) is less obviously a lullaby than that of Die schöne Müllerin (“Des Baches Wiegenlied,” D795/20), it possesses the hypnotic qualities associated with that genre, with its steady harmonic grounding and the repetitive looping figures in the melodic line. But in its angularity and eschewal of comfort, “Der Leiermann” forms a grotesque version of lullaby.26 In more muted form, lullaby is threaded through the cycle. “Wasserflut” mixes its piano LH topic (its dotted-rhythm dirge conveying an aura of funeral march, albeit in triple time) with a distinctly different RH topic, whose hypnotic rocking arpeggio figures signal lullaby, demonstrating the power of music to express two or more contrasting items simultaneously. Bostridge’s argument for non-assimilation of the differing rhythmic elements in the piano LH and RH receives support from the presence of these two topics.27

Schubert has taken his cue for the more restful lullaby topic in “Wasserflut” and in the final verse of its predecessor, “Der Lindenbaum,” from the protagonist’s expressions of yearning for peace and rest (“Ruh”). These form a poetic motif throughout the cycle. In the ABCABC form of “Frühlingstraum,” the C section exhibits lullaby properties as the protagonist reflects on his dreams with a profound sense of loss: “Wann halt’ ich mein Liebchen im Arm?” (When will I hold my love in my arms?). The rocking octaves in the piano accompaniment soothe rather than disturb. Here, as elsewhere, the piano is a sympathetic responder to the protagonist’s mood.

Antique Style

Contributing to the profundity of Winterreise is Schubert’s frequent turning toward antique models of musical material, a phenomenon rife also in the instrumental music of his last decade. In D911, such references appear in a variety of shapes and contexts: some instances are clearly audible on the surface, while others are embedded more subliminally. Their use contributes to the dual-facing impression that pervades Winterreise. Both Müller and Schubert show allegiance to inherited forms of expression, as well as an experimental modernity. The ancient formulae come loaded with meaning. Most loaded of all is the chromatic fourth, the lament bass familiar from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, and widely used in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century instrumental as well as vocal genres. The chromatically filled-in fourth, or fragments of it, threaded through the musical texture in D911 (see Table 10.1 and Example 10.4) is a constant reminder of the protagonist’s incurable sense of loss. In Part II its traditional association with death emerges more strongly.

Example 10.4 “Der Wegweiser,” mm. 65–83

Linked to antique style is the religioso topic present from the start of the cycle with the turn to F major (and its subdominant B♭) in verse 1 of “Gute Nacht.” The hymn-like veneer added to a variant of the trudging motif in the accompaniment there comes to the surface (like much else) towards the end of the cycle. Graham Johnson sees the key of F major, inflected with subdominant color, that Schubert chose for “Das Wirtshaus” as an anomaly, illogically poised between the G minor songs on either side.28 But we could interpret it as a reference to the original manifestation of that topic in “Gute Nacht,” in those same keys (F and B♭). Seen in this light, in “Das Wirtshaus,” they serve simultaneously as a reminder of the hope of lasting love that was lost at the origin of the journey, and a signal of the hope for death that has replaced it.

Commentators have not failed to notice parallels in the poetic text of “Das Wirtshaus” to the Nativity story, and also in that text, as in the winter journey altogether, to the Passion story. Schubert’s music in “Das Wirtshaus” endows the funereal scene, and the protagonist’s response to it, with dignity, reinforcing the idea conveyed in the words of the preceding song, “Der Wegweiser,” of his purity of character. Whatever the protagonist’s theological stance may be, reference to antique models, and hymn-like style, confer a seemingly genuine aura of the sacred on the music of Winterreise. It gains added gravitas when infused with counterpoint. Among Schubert’s references to antique style, and a personal fingerprint shared across the range of genres he cultivated, is the 4–3 suspension, first heard in “Gute Nacht” together with the hymn-like topic at mm. 16–17 (Example 10.1). This ancient contrapuntal formation becomes a pervasive element thereafter.

Schubert’s penchant for canonic technique contributes to the seriousness evoked in particularly portentous passages of the text. The archaic references in “Der Wegweiser” present the most intense example, ranging from the canonic reflections of the funereal opening phrases between voice and piano, threaded through the minor-key A sections (the brief memory of the traveler’s blameless past in the central B section is free of such artifice), to the building of tension in the final measures, with their combination of chromatic fourth (lament figure) and wedge (chromatic contrary motion), as marked on Example 10.4. Both those figures are weighted with a history of fugal counterpoint. Their inexorable move towards collapse, followed by the unmistakable quotation from “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (the dactylic repeated-note figure associated with death), forms one of the most ominous endings in Winterreise.

Epilogue

Schubert’s scene-painting in Winterreise has a vividness fueled by his evident belief in music’s power to bring words to life – a belief shared by Müller. In joining his art to Müller’s, Schubert conjured up the swinging weathervane (sign of the girl’s faithlessness) in “Die Wetterfahne,” the descent to the rocky depths in “Irrlicht,” the shrieking ravens in “Frühlingstraum,” the falling leaves in “Letzte Hoffnung,” the dogs barking in “Im Dorfe,” the hurdy-gurdy playing in “Der Leiermann,” and much else. Beyond this, Schubert’s settings convey his profound feeling for the central character. Because Schubert was deeply moved by the protagonist’s sufferings, his music for Winterreise, working with the poetry, has the power to move us.

Noticeable in Müller’s text is the evidence of the human urge to leave some trace of a person and a life, expressed in the traveler’s memories of carving names in happier times into tree bark, and his wish, as he makes his winter journey, to etch them on the icy surface of the water. Schubert, writing his name as a composer on the surface of the poetry, allows us access to the depths that lie beneath.