When we think about the musical features most characteristic of jazz, those that particularize its style and distinguish it from other kinds of music, we almost always think of rhythm first. There are other important features, to be sure – the centrality of improvisation, for example, or the blues foundation of jazz melodic practice. But rhythm has typically been the feature addressed first in most writings on jazz since its origins early in the twentieth century, pride of place signaling its significance to jazz fans, critics, and historians.

The word most centrally associated with the rhythmic component of jazz, of course, is swing. The term has a few interrelated meanings today. It is used rather superficially to designate a particular way of articulating eighth notes (understood in contrast to “straight” eighth notes), or to refer to the underlying “groove” of what has come to be called “straight-ahead” or “mainstream” jazz.1 More substantively, however, swing refers to a mysterious but fundamental rhythmic quality historically thought to be the essence of true jazz; absent swing – irrespective of eighth-note articulation or the syntactical features of the rhythm section’s groove – one presumably does not have jazz.2

And yet, characterizing this rhythmic quality, let alone explaining it, has proven to be extremely difficult, if not impossible. Definitions have varied widely, as have the connotations it carries. Prior to its use with jazz, the term referred to a lively, danceable rhythmic cadence in virtually any kind of music, as well as poetry. It came to be associated exclusively with jazz only in the 1930s, when it acquired an implicit racial meaning that it has never fully shaken.3 Since then, scholars have taken a variety of approaches to defining swing and explaining its effects. Some have understood swing as the product of timing relationships between the instruments in a jazz ensemble, especially the rhythm section. Others have investigated the “swing ratio,” seeking to better differentiate the timing profiles of individual artists or to generalize across instruments or historical periods. Ample data have been gathered, and yet we seem to be no closer to understanding the nature of swing than we were during the Swing Era itself.

Why is swing so difficult to explain? It was intractable by design, a means of establishing a foundational and indisputable criterion of value for jazz as a whole, but also serving as a measuring stick by which to distinguish true jazz from false, good from bad. It emerged in the 1930s as the term to describe jazz rhythm, designating a rhythmic quality belonging to no other music, recognizable to those in the know and quantifiable in the sense of less or more, but otherwise, indefinable. As such, it answered a need in jazz criticism of that time as a defense against those who had claimed that jazz offered nothing new, nothing unique, to music.

Prior to the 1930s, discussion of rhythm in jazz differed little from that of its predecessor, ragtime – hardly surprising, since jazz was built on the rhythmic foundation of ragtime. Commentary on both tended to focus on two principal features: (1) the relentlessly steady pulse of the music (what Richard Waterman later famously described as the “metronome sense”), and (2) the extensive use of syncopation.4 These were indeed the most salient rhythmic characteristics of both ragtime and early jazz, but there was nothing particularly distinctive or original about either one: most kinds of dance music required a fairly metronomic pulse, and syncopation was certainly not unique to jazz or other forms of African American music. Critics of ragtime and jazz frequently seized upon these facts as evidence of the music’s lack of artistic merit. The reliance on syncopation was purportedly due to a lack of imagination, and thus the music was about rhythmic excess, not the exercise of good taste, as the anonymous author of an 1899 essay published in The Étude makes clear:

Ragtime music has a respectable old genesis; an old, venerable one indeed. We need not go farther back than to the music of the god-like Beethoven to find examples of ragtime music; though formerly known under a more respectable technical name, that of syncopation. So ragtime music is simply syncopated rhythm maddened into a desperate iterativeness; a rhythm overdone, to please the present public music taste.5

David Stanley Smith, Dean of the Yale School of Music, said much the same thing about jazz in 1924:

What is bound eventually to deaden the inventiveness of the “great American composer” is the fact that jazz is the exploitation of just one rhythm. This rhythm is the original rag-time of thirty years ago. There have been occasional captivating additions to it in the form of elaborate counterpoints in jarring rhythmic dissonance, but the fundamental “um-paugh, um-paugh” and the characteristic syncopation persist through the years. Without these there is no jazz.6

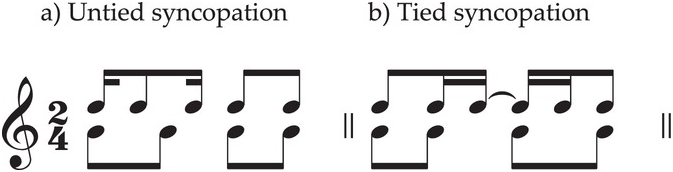

Contrary to such criticisms, ragtime historian Edward A. Berlin finds it significant that “these rhythms were used with sufficient consistency to define the ragtime idiom, and that the intent of such rhythms, an intent made abundantly clear from the sheet-music covers and titles, was to reproduce the character of ‘quaint’ black music.”7 To that end, ragtime composers made extensive use of two specific varieties of syncopation thought to typify black rhythm, which Berlin refers to as “untied” and “tied,” illustrated in Example 10.1.8

10.1 Conventional ragtime syncopations

Untied syncopations remain within the separate halves of a measure, and are thus minimally disruptive to the perception of metric regularity. Whatever destabilization of the meter emerges on the weak second eighth-note beat is quickly dispelled through a return to metric congruence on the strong third beat, further confirmed on the fourth. Tied syncopations, by contrast, offer greater potential for disrupting perception of metric regularity over a greater span of time. Here, it is the strong third beat that is destabilized with syncopation; metric congruence returns on the weak fourth beat, and thus the ensuing downbeat is required for further stabilization.

Drawing data from a sample of 1,035 piano rags published between 1897 and 1920, Berlin found that untied syncopations were considerably more common than tied syncopations through about 1900. As the decade wore on, however, tied syncopations came to predominate. In 1900, the ratio of untied-to-tied-syncopation rags in Berlin’s sample was 3:1. By 1902, it had flipped to 1:3, and then dropped to 1:7 by 1905 and 1:20 in 1908.9 The untied syncopation figure was a relic of blackface minstrelsy, a rhythmic convention found in innumerable late nineteenth-century character pieces referencing antebellum black folk dances. The decline of its frequency correlates to the disappearance of “the more flagrantly abusive form of coon song” and a “deracialization” of ragtime song by 1906.10

Meanwhile, as the frequency of tied syncopations grew, they came increasingly to be used at the tail end of the “secondary rag” figure, another common feature in early ragtime first identified by Don Knowlton in 1926.11 Essentially a 3×2 polyrhythm, the secondary rag generates what Harald Krebs describes as a grouping dissonance.12 The opening measures of the A strain of George Botsford’s Black and White Rag, shown in Example 10.2, provide a typical example.13 In mm. 5–6, a 3-line (1=16th) is superimposed over a 2-line through four iterations over dominant harmony, at which time the pattern breaks with a tied syncopation. This pattern is repeated over tonic harmony in mm. 7–8.

10.2 Botsford, Black and White Rag, mm. 5–8

Berlin also reports the growing use of dotted rhythms in the published rag repertory of the 1910s. In the first decade of the century, dotted rhythms appeared in less than 6 percent of published rags. This figure would grow to 12 percent in 1911, 23 percent in 1912, 46 percent in 1913, and 58 percent in 1916. Meanwhile, syncopation remained common in the ragtime repertory throughout this decade, but it was seldom used in dotted-rhythm passages.14

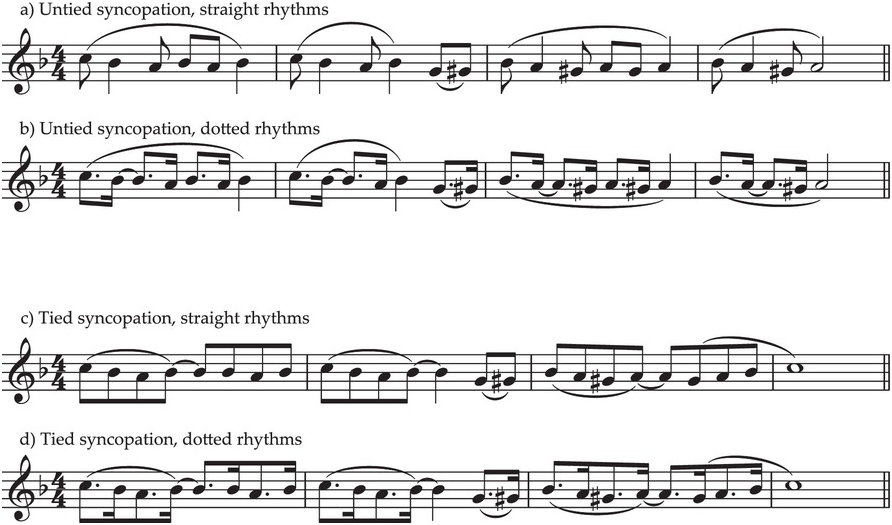

This increase in the use of dotted rhythms suggests an effort by ragtime composers to reflect in music notation the performance practices of itinerant black piano players like Jelly Roll Morton. By this time, these musicians were likely making use of what would later be termed “swing eighth notes,” a practice hinted at a decade earlier in some of the few extent banjo recordings of rag tunes made in the early 1900s.15 Dotted notation is simply an early effort to capture in writing the long-short durational patterning of swing eighth notes. Contrary to Berlin, I suggest the absence of syncopations in dotted-note passages is less indicative of a stylistic difference between dotted and non-dotted passages than a consequence of the difficulty of notating (and reading) both untied and tied syncopations in dotted rhythms. Compare, in Example 10.3, the ease of reading the untied syncopations in the passage shown in (a), as opposed to the same passaged rendered in dotted notation in (b). Parts (c) and (d) present a similar passage involving tied syncopations in straight and dotted rhythms, respectively. The notation of (b) and (d) is visually too busy and simply cumbersome. On the other hand, though examples (a) and (c) are notated “straight,” as it were, it is easy enough to perform them in swing eighth notes.

10.3 Comparison of syncopated passages using “straight” rhythms and dotted rhythms

Though ragtime and early jazz composers avoided rendering syncopations in dotted rhythms in the 1910s and beyond, they did not hesitate to write secondary rag passages in dotted rhythms, as can be seen in the A strain of Zez Confrey’s Kitten on the Keys, shown in Example 10.4.16 In notation, this passage appears to involve a very complex grouping dissonance seemingly impossible to define in terms of an intelligible ratio. But if the dotted rhythms are understood as swing eighth notes, it is clear enough that this is simply a durationally embellished version of a simple 3/2 grouping dissonance (1=8th). Confrey avoids writing dotted rhythms for the tied syncopations in the ensuing passage (Example 10.5), but in his recorded performance, the durational relationships of the notated eighth notes are indistinguishable from those of the dotted rhythms in the preceding passage.17 Confrey was clearly working in terms of swing eighth notes. He used dotted rhythms in non-syncopated passages to convey this, but simplified the notation to plain eighth notes for clarity in the syncopated passages.

10.4 Confrey, Kitten on the Keys, mm. 7–10

10.5 Confrey, Kitten on the Keys, mm. 11–14

10.6 Possible representations of beat division in jazz performance from Waterman’s Piano Forms

The term swing eighth notes would not enter the jazz vernacular for another few decades, but a few astute observers did recognize both the distinct character of beat division in late ragtime and early jazz and the inadequacy of dotted rhythms to convey the long-short durational relationship between downbeat/upbeat pairs. In 1923, Gilbert Seldes observed that the “fixed groups of uneven notes” in Zez Confrey’s Stumbling, published in 1922, “are really triplets with the first note held or omitted for a time, then with the third note omitted and so on.”18 Seldes seems to be referring to the quarter-eighth (2:1) triplet rhythm that would later become a standard (if inaccurate) way of describing the “swing ratio.” Glenn Waterman was more explicit a year later in rendering jazz rhythm explicitly in terms of triplets. In an explanation of how to syncopate a simple quarter-note melody, he describes dotted rhythms as “too jerky.” Good jazz performance, according to Waterman, depends on “[t]he exact ‘way’ of striking these two-eighths (also written as dotted eighth and sixteenth). … They must be played as a triplet with the first note tied.”19

Another early commentator, Don Knowlton, retained dotted notes in his discussion of jazz rhythm, but emphasized the difference between what he referred to as the “–um-pa-tee-dle” pattern of “the real jazz tune” and “the old one-two, one-two rhythm” of the march, found in much popular music of the day. The “–um-pa-tee-dle” pattern, according to Knowlton, serves as the real foundation upon which “are superimposed certain alterations of rhythm which are the true components of jazz.”20 Knowlton, like other advocates of jazz in the mid-1920s, recognized there was something truly distinctive about jazz rhythm, something non-jazz musicians, or even non-Americans, found very difficult to produce. Paul Whiteman, for example, found that “only Americans can really play syncopated music. Musicians of other countries do not seem able to get into the swing of it. They fail to accomplish by training what we do by nature.”21 Virgil Thomson, too, felt there was something quite particular about jazz rhythm. In a detailed discussion of the expressive effects of jazz syncopation, he proposed that “the peculiar character of jazz is a rhythm, and that that rhythm is one which provokes motions of the body.”22

Statements like these, which acknowledge the distinctiveness of jazz rhythm and seek to explain its expressive effects, stand in sharp contrast to the contemptuous writings of those like Oscar Thompson, who found little value in jazz and less still of interest in its rhythms:

There was never a greater absurdity than the talk of rhythmic variety in jazz. Jazz is rhythm in a straight-jacket. Its so-called “variety” is the apogee of monotonous periodicity. … It is this very regularity that gives jazz its propulsively forward movement. Its measures are marked with the deadly certainty of a piston rod. Its rhythm is that of the exhaust of a noisy gas engine. No other music the world has known has so approached the mechanics of driven wheels.23

Thompson, like other critics, focused his ire on obvious surface features of jazz rhythm – the relentlessly steady pulse or the overabundance of syncopation. Advocates of jazz, however, felt there was something more to it, something deeper about its rhythm that was irreducible, undefinable, unrepresentable; they simply lacked the vocabulary to talk about it, and thus continued to refer to things like syncopation or the use of dotted rhythms – features that could easily be identified, belittled, and dismissed.

At any rate, Thompson’s brand of criticism would largely disappear in the 1930s, at least in the United States. Changes in the jazz rhythm section and a more melodic style of performance less reliant on syncopation led to a music less raucous in its rhythmic effects. Jazz entered the commercial mainstream in the 1930s, as well, and with the repeal of Prohibition, its associations with illicit nightlife largely disappeared. Under these conditions, jazz appeared less of a threat to the social order, and its rhythms were no longer invested with as much anxiety.

Meanwhile, on the critical front, the emergence in the 1930s of the modern concept of swing through the activities of French jazz critic Hugues Panassié and the American impresario John Hammond served to redirect criticism of jazz rhythm from the superficiality of surface features to a deeper, more profound rhythmic core, a generative impulse presumably available and accessible only to a gifted elite.

The word swing had been employed in writing about music since at least the 1870s to refer to a danceable rhythmic cadence in styles as widely disparate as Verdi operas and Sousa marches. This breadth of usage continued into the 1930s, but by decade’s end, the term had come to be associated exclusively with jazz.

There is evidence the word swing had entered American jazz musicians’ argot by 1933 (it shows up in spoken passages on a few Louis Armstrong records recorded that spring),24 but no indication they understood it to be a kind of foundational rhythmic essence, Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing” notwithstanding. Though premiered in August 1931, recorded in February 1932, and widely popular by 1933, the “swing” of its subtitle and opening line, belted out with such verve by Ivie Anderson, generated virtually no commentary until well into 1935. Rather, its specialized meaning for jazz came from the efforts of Hugues Panassié to translate it into French around the time of Ellington’s visit to Paris in July 1933. Finding no suitable French equivalent, Panassié used swing as a technical term, conceptually altering an American colloquialism to serve as a critical filter for distinguishing true jazz from false. His notion of swing was then re-integrated into the American understanding by his colleague and friend John Hammond, who wrote about it repeatedly in his column for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in early 1935, when he was actively promoting Benny Goodman’s band. By year’s end, “What is ‘swing’?” would be the question on everyone’s lips.

In truth, no one had a good answer – and no one ever has. The problem of definition started with Panassié, who is most responsible for introducing the term to jazz critical discourse through his book Le Jazz Hot, published in 1934. Panassié’s conception of swing was built on a constellation of five assumptions. First was the notion that swing was a rhythmic quality foundational to good jazz, what Panassié describes as “that essential element of jazz found in no other music.” “All true jazz must have swing,” he writes. “Where there is no swing, there can be no authentic jazz.” Second, though ultimately undefinable according to Panassié, swing was nevertheless an “entirely objective” property, such that “there is almost always complete agreement among competent critics” regarding its presence and intensity in any given performance. Third, swing is a “gift.” It is something innate, something a musician is born with: “either you have it deep within yourself,” writes Panassié, “or you don’t have it at all.” Moreover, it cannot be learned: “neither long study nor hard work will get you anywhere in jazz if you do not naturally know how to play with a swing. You can’t learn swing.” Fourth, there is no single way to swing: “swing varies according to the instrument played,” writes Panassié, but even “on the very same instrument, each musician will have his own ways of getting swing.” And finally, for Panassié, swing was short for Negro swing, a property that “belongs to jazz alone and derives from those Negro musicians who first created it.” Swing, in other words, was a rhythmic quality that was ultimately the expression of a black racial essence.25

There is plenty to argue with in Panassié’s formulation of the swing concept, but by and large, the five basic claims he lays out about swing in Le Jazz Hot in 1934, summarized above, continue to serve as the underlying assumptions of our everyday understanding of that concept even today – though most critics wouldn’t be so baldly essentialist. This is the modern concept of swing in a nutshell. It crystallized in the popular imagination around 1935, largely as a consequence of Panassié’s writings and promotional activities, along with those of his American counterpart, John Hammond.

As an explanation of swing or a guide to how to recognize it or produce it, Panassié’s account was an utter failure. But what it made possible was the consolidation of thought about jazz rhythm around a single foundational concept. Swing offered an explanation for the rhythmic particularity of jazz that went beyond surface-level phenomena like syncopation. Swing was not the kind of thing that could be notated and thus co-opted by other forms of music. Syncopation wasn’t unique to jazz, of course; it was ubiquitous in the music, to be sure, but not the thing that really distinguished it from other kinds of music. But swing did. It was a deep phenomenon, something rooted in racial essence, and thus something that particularized jazz and explained what made it categorically different from other kinds of music. Never mind that it couldn’t be defined; it could be believed. Syncopation was a feature, an effect; swing was an essence, a prime cause.

Panassié’s conceptual framework for swing – the five assumptions adumbrated above – served as the critical foundation for discussions of jazz rhythm for decades. Subsequent critics, historians, and scholars repeatedly sought to explain swing and the means of its production, but no one seemed to question Panassié’s claim that swing was the essential element of jazz or that it was an objectively real rhythmic phenomenon – or that it was situated in a domain that is difficult, and perhaps even impossible, to access through the intellect. Its power, in Panassié’s framework, lies in the mystery of its source and the means whereby it generates its effects, a process hidden from conscious awareness that good musicians can nevertheless actualize without thought or deliberate intention. For Panassié, that source was ultimately to be found in the putative rhythmic effects of race. Countless other scholars have followed his lead in that direction, some more explicitly essentialist than others.

Among the most important post-Panassié critics to undertake an explanation of the swing phenomenon was André Hodeir, who devoted an entire chapter of his book Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence to outlining “the five optimal conditions for the production of swing.” These included:

1. the right infrastructure

2. the right superstructure

3. getting the notes and accents in the right place

4. relaxation

5. vital drive26

The last of these, “vital drive,” was Hodeir’s most unique contribution to Panassié’s conceptual framework, though his explanation of its character and source is as murky as his predecessor’s explanation of swing. Hodeir described vital drive as “an element in swing that resists analysis.” It stems from “a combination of undefined forces that creates a kind of ‘rhythmic fluidity’ without which the music’s swing is markedly attenuated.” It is, moreover, a “manifestation of personal magnetism, which is somehow expressed – I couldn’t say exactly how – in the domain of rhythm.” Like Panassié, however, Hodeir saw race as a relevant factor in the production of vital drive; white bands, he found, fail to swing adequately because “their vital drive is weak.”27

In 1966, ethnomusicologist Charles Keil introduced perhaps the most consequential transformation of the Panassié model.28 Keil abandoned the racial essentialism of earlier writers, but retained the mysterious nature of swing by situating it in a quality he called “engendered feeling,” that certain something beyond notation that performers add to music to generate “vital drive.” Engendered feeling, Keil proposed, stems not from syntactical processes – i.e., processes that can be represented in standard musical notation, in quarter notes or eighth notes, for example. It emerges rather from musicians’ use of expressive microtiming at the sub-syntactical level in sustaining a rhythmic groove, a phenomenon he later dubbed “participatory discrepancies,” or PDs.29 PDs are a form of rhythmic displacement different from offbeat rhythms, syncopations, or anticipations. In the PD framework, engendered feeling (i.e., swing or vital drive) results from the cumulative tension acquired through “pulling against the pulse.”30 Onset discrepancies, typically on the order of less than about 50 milliseconds (about 1/20th of a second), between the pluck of the walking bass and the drummer’s ride cymbal taps in their shared articulation of the beat purportedly generate some qualitative feeling of either rhythmic drive (“push”) on the one hand, or relaxation (“layback”) on the other.

PD theory thus assigns responsibility for the production of swing to the sub-syntactical realm of microtiming and downplays the significance of more tangible and visceral events that take place on the syntactical plane of notatable musical phenomena.31 Whether or not such discrepancies are robust and powerful enough to drive the groove and generate swing remains an open question, however.32 At any rate, the belief that expressive microtiming has consequential effects in the realm of jazz rhythm has driven a good deal of scholarship in the last few decades. Studies have concerned two types of timing discrepancies in jazz performance: (1) those within a single instrument or part; and (2) those between the instruments of an ensemble. Research on the former has generally concerned the “swing ratio,” whereas research on the latter has addressed the “hookup” between bass and drums in sustaining a steady groove, as well as soloists’ timing in relation to the drummer’s ride rhythm. Most of these studies, incidentally, have concerned timing in straight-ahead jazz, with the bulk of their data coming from laboratory contexts with currently active professional musicians or from recordings drawn from the hard bop repertory of the 1950s.

The “swing ratio” expresses the durational relationship between the long, downbeat eighth note and the short upbeat that follows it. The conventional assumption that successive swing eighth notes stand in a durational relationship of 2:1, traditionally represented in notation as a quarter-eighth triplet pair, has been shown to be largely inaccurate. In practice, swing ratios vary widely, ranging from an even 1:1 to as high as 3.5:1, varying with tempo and ensemble function (i.e., soloist vs. accompaniment).33 Soloists tend to play minimally uneven swing eighths, typically ranging from about 1.2:1 to 1.5:1. They often vary their swing ratios over the course of a phrase for expressive purposes, either to drive momentum forward or to dissipate motional energy.34 Soloist swing ratios tend to be most even in the middle of a phrase, but then frequently increase in value toward the end of a phrase, where what Fernando Benadon has referred to as a “BUR surge” tends to serve a closural function.35

By contrast, drummers tend to use relatively large swing ratios, particularly in maintaining time on the ride cymbal. Swing ratios in the “ride rhythm,” the standard “ding-ding-a-ding” figure played on the ride cymbal since the bebop era, are typically in the neighborhood of 2:1. They tend to be larger at slow and medium tempos, but approach 1:1 in the fastest tempos.36 Drummers also sustain remarkably consistent swing ratios in the ride rhythm, especially at moderate to fast tempos.37

Studies of timing relationships between instruments have revealed interesting practices also related to ensemble function. The “hookup” between bass and drums, in particular, has received a great deal of attention. Bass players tend to synchronize their downbeat attacks quite tightly with the drummer’s ride tap, with generally no more than a 20-ms gap between them.38 Bass and drums may take turns in the lead, as it were, switching places on occasion for expressive purposes.39

Soloists tend to time their attacks with considerably greater flexibility in relation to the drummer’s ride tap. They typically lay back on the beat by about 50–80 ms, but then synchronize their offbeat eighth notes quite tightly with the drummer’s short tap. Consequently, the degree of delay varies inversely with the swing ratio they employ at any given moment: more delay entails a smaller swing ratio, indicative of more even eighth notes, while less delay entails a higher swing ratio, with greater unevenness.40

Eighty-five years have passed since Hugues Panassié published the first comprehensive account of swing in Le Jazz Hot. And yet it remains unclear what exactly swing is. Perhaps the most we can say is that it is a word we use to describe an attractive rhythmic quality in jazz, one that is often characterized by a sense of forward propulsion and that presumably has the effect of inducing movement on the part of the listener. However, the fact that no consensus has yet emerged on what exactly swing is or how it is produced suggests that the term has perhaps outlived its usefulness in designating the core component of jazz rhythm. It might be more productive to use Keil’s term “engendered feeling,” or even Hodeir’s “vital drive,” to refer to the motional qualities of jazz and other forms of groove-based music – qualities conditioned by the action of “participatory discrepancies.” Microtiming studies of both the swing ratio and intra-ensemble “hookup” have begun to clarify at least some of the expressive features of jazz rhythm. But much work remains to be done in integrating the data, most often produced by specialists in music cognition, into a music-theoretical framework of use for music analysis. How do soloists, for example, manipulate microtiming over the course of a single phrase or through an entire solo to expressive effect? How do PDs in the domain of timing interact with those in the realm of timbre and articulation? And to what extent do the data gathered from studies of straight-ahead jazz translate into generalizable features of other jazz styles, or other forms of groove-based music beyond jazz? These and other questions suggest a promising future for the study of jazz rhythm.

Introduction

Following the Second World War, the West – especially the United States – experienced a period of sustained economic growth. In tandem, birth rates peaked such that by the mid-1950s, a strong youth culture began to take shape, fueling a great expansion of mass media. Television, radio, movies, and music became increasingly ubiquitous elements of society as consumers, especially young consumers, sought ways to spend their leisure time and disposable income. This cultural sea change engendered a revolution in musical style, with rock and roll – or simply “rock” as it later became known – emerging as a dominant force in popular music.

The musical characteristics of early rock and roll can be seen as an amalgam of styles prevalent during the 1930s and 1940s, including blues, country, and jazz. The fusion of these disparate styles into a single “super-style” involved importing traits from each, of course, but also a comprehensive streamlining to make the fusion appeal to a broad audience. The rhythm section, for example, became codified into the conventional arrangement of drums, bass, and guitar; meter became distilled into a regular back-and-forth pattern of kick and snare; and song forms began to follow formulaic templates.

But while the norms of 1950s rock and roll can appear to simplify earlier practices, these structures laid the groundwork for decades of stylistic evolution. Indeed, while present-day rock music often involves highly complex rhythmic structures, it grows out of fundamental rhythmic principles already widespread by the 1960s. The current chapter provides an overview of these principles, spanning from the dawn of rock and roll to modern pop/rock.

The chapter is arranged into three main sections. The first, on tactus and tempo, examines what is meant by the “beat” in rock. Although many songs have only one primary pulse layer, others exhibit conflicting levels of pulse. The second section, on meter and measures, offers an overview of the typical organizational schemes for rhythm and meter. Unlike traditional time-signature-based approaches, meter in rock warrants some classification mechanism for swing at various levels and different drum feels. The third section, on syncopation and stress, discusses some of the most common rhythmic patterns in melody and harmony. In particular, the pervasive metric displacement of stressed pitch events away from strong beats creates a rhythmic texture emblematic of the rock style.

Tactus and Tempo

The most central rhythmic element of any musical style is the beat. In traditional understandings, the beat – or tactus – is the most perceptually salient pulse layer, i.e., the steady rate at which a listener will bob their head or tap their foot. Given this understanding, beat is essentially synonymous with tempo, as measured in beats per minute (hereafter, BPM).

In the parlance of rock musicians, though, “the beat” can take on additional meanings. Foremost, it can serve as shorthand for “the drumbeat,” i.e., the drum pattern of a song. The standard rock beat, for example, is a drum pattern in ![]() with the kick on beats 1 and 3, the snare on beats 2 and 4 (the “backbeat”), and the hi-hat or ride playing some metrically congruent division of the measure into equal parts. This conflation of “beat” and “drumbeat” is no coincidence, since the regular occurrence of the kick and snare on primary divisions of the measure strongly conveys one layer of pulse to the listener.

with the kick on beats 1 and 3, the snare on beats 2 and 4 (the “backbeat”), and the hi-hat or ride playing some metrically congruent division of the measure into equal parts. This conflation of “beat” and “drumbeat” is no coincidence, since the regular occurrence of the kick and snare on primary divisions of the measure strongly conveys one layer of pulse to the listener.

An even further generalization of “beat” exists as well. Although the drum pattern is an important factor in assessing tempo, other instruments (including the vocal) typically convey information related to tempo perception. For example, when a listener says, “This song has a good beat,” they mean at least three separate things: (1) that it is easy to synchronize body motions with the song’s primary pulse rate, implying it is not too fast or too slow; (2) that the drumbeat is consonant with this pulse rate; and (3) that all of the instrumental elements facilitate body motions, not only at the primary pulse layer but also other metric levels. In this third sense, “the beat” is somewhat synonymous with “groove” or rhythmic “feel,” i.e., the overall rhythmic fabric of a song.

The relationship between body motions and the rock beat is a seminal component of rock rhythm, because a regular role of rock music is something for people to dance to. The goodness of a rock beat thus relates to its danceability, especially the type of energetic dancing that symbolizes youthfulness. Perhaps not surprisingly, average tempos for rock exceed those of other musical styles. Musicologists, for example, posit that tempos for classical music are most often in the range of 60–80 BPM, corresponding to an adult’s resting heart rate.1 In contrast, average tempos for rock lie within the 110–125 BPM range, corresponding to an elevated heart rate associated with physical activity.2

Given that the lower end of the range for typical tempos in classical music (60 BPM) is about half the upper end of the range for rock (125 BPM), it may be that classical and rock musicians will sometimes disagree on the primary pulse layer of a musical work due to different expectations. Which metric level, for example, represents the main beat at the beginning of the second movement to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C Minor, Op. 13 (Example 11.1)? As a timing reference, consider Arthur Rubinstein’s 1962 RCA recording. Despite the ![]() time signature that Beethoven indicates, the quarter note cannot be the primary pulse layer, for it is too slow to be a viable beat; in Rubinstein’s performance, the quarter-note rate is about 29 BPM, which lies below the 30 BPM threshold for beat perception noted by music cognition researchers.3 More likely, a classical musician will feel the eighth note as tactus, which in Rubinstein’s performance is around 58 BPM, since this rate aligns more closely with tempo norms in classical music.

time signature that Beethoven indicates, the quarter note cannot be the primary pulse layer, for it is too slow to be a viable beat; in Rubinstein’s performance, the quarter-note rate is about 29 BPM, which lies below the 30 BPM threshold for beat perception noted by music cognition researchers.3 More likely, a classical musician will feel the eighth note as tactus, which in Rubinstein’s performance is around 58 BPM, since this rate aligns more closely with tempo norms in classical music.

11.1 Beethoven, Piano Sonata in C Minor, Op. 13, II, mm. 1–4

For a rock musician, however, the sixteenth note may be the preferred tactus, as it engenders a more typical rock tempo. Indeed, it is in this way that the band Kiss conceptualizes Beethoven’s theme, which is featured at the beginning of their song “Great Expectations” (1976). In particular, when the Beethoven theme appears at 2:24, the drumbeat implies a tempo of 116 BPM. Note that the pacing of harmonic and melodic content in Kiss’s arrangement is almost identical to that in Rubinstein’s performance; the opening tonic chord, for example, lasts about two seconds in both versions. The Kiss arrangement thus does not alter the rate at which musical content is disbursed; rather, it offers a different hearing of the tactus, one corresponding better with an upbeat, danceable tempo.

The preference in rock for danceable tempos is so intrinsic to the style that experienced listeners may feel tempos nearer the 110–125 BPM ideal even when the drum pattern gives conflicting information. A good example of this scenario is the song “Human Nature” by Michael Jackson (1983). If the kick and snare in this song are taken to indicate beats 1 and 2 in ![]() the tempo would be 47 BPM. While this tempo lies above the 30 BPM lower limit for beat perception noted earlier, it seems too slow to animate lively body movement. As a result, most listeners will synchronize with a tempo twice that speed, 93 BPM, which comes closer to a typical rock tempo. Indeed, Michael Jackson can be seen in live performances to bounce his leg at this 93 BPM rate. In this song, there thus exists a tension between the tactus more preferred for dancing and the pulse implied by the kick and snare.

the tempo would be 47 BPM. While this tempo lies above the 30 BPM lower limit for beat perception noted earlier, it seems too slow to animate lively body movement. As a result, most listeners will synchronize with a tempo twice that speed, 93 BPM, which comes closer to a typical rock tempo. Indeed, Michael Jackson can be seen in live performances to bounce his leg at this 93 BPM rate. In this song, there thus exists a tension between the tactus more preferred for dancing and the pulse implied by the kick and snare.

What, then, is the tempo of “Human Nature”? Some musicologists suggest that tempo should always be determined by the kick and snare (thus 47 BPM here).4 But this hard-and-fast rule often ignores the beat rate most listeners prefer. An alternative is to say that the tempo of “Human Nature” is 93 BPM, while the kick and snare alternate at half that rate. Rock musicians refer to this metric organization as a “half-time feel.” During a half-time feel, there exists a divorce of the drum pattern from the primary tactus. Thus, while drum patterns traditionally align with the primary beat, the existence of a separate musical layer (the drums) dedicated to rhythmic information allows for a more complex arrangement in which the drumbeat operates on a different level of the metric hierarchy than the tactus.

While some songs like “Human Nature” are in a half-time feel throughout, other songs will change between a normal and half-time feel (and vice versa). For most of the Ne-Yo song “Closer” (2008), for example, the drum pattern is congruent with the song’s tempo, 126 BPM in ![]() with the hand-claps on beats 2 and 4 substituting for the snare. In the last chorus (3:33), however, the hand claps move to beat 3, creating a half-time shift that breaks up the monotony of yet another chorus. Note that this new drum feel at the song’s end does not affect the pacing of the harmonic and melodic material, which repeats earlier content verbatim.

with the hand-claps on beats 2 and 4 substituting for the snare. In the last chorus (3:33), however, the hand claps move to beat 3, creating a half-time shift that breaks up the monotony of yet another chorus. Note that this new drum feel at the song’s end does not affect the pacing of the harmonic and melodic material, which repeats earlier content verbatim.

In addition to half-time feels, songs may employ a double-time feel, where the kick and snare alternate at twice the primary pulse rate. The song “Should I Stay or Should I Go” by the Clash (1982) provides a good illustration of this scenario. The verse material (0:17) is a variation on the standard twelve-bar blues pattern at a comfortable tempo of 112 BPM in ![]() with the normal snare backbeat on beats 2 and 4. In the chorus (1:08), though, the drum pattern changes such that the snare occurs regularly on the “and” of every beat, assuming the same tempo. Admittedly, the increased rate of kick and snare alternations gives the feeling of a faster tempo, 224 BPM. But it is rather uncomfortable to sustain head-bobbing or foot-tapping at this rapid pace. Moreover, the chorus is basically a repeat of the same twelve-bar blues pattern of the verse, with the same pacing of melodic and harmonic content. As a result, it seems more analytically robust to describe the chorus as having a tempo of 112 BPM with a double-time feel – thereby capturing the conflict between the drum pattern and the implied beat based on the unaltered pacing of harmonic and melodic content – rather than to simply say the tempo has increased to 224 BPM, which does not account for the lack of speed change in the harmony and melody.

with the normal snare backbeat on beats 2 and 4. In the chorus (1:08), though, the drum pattern changes such that the snare occurs regularly on the “and” of every beat, assuming the same tempo. Admittedly, the increased rate of kick and snare alternations gives the feeling of a faster tempo, 224 BPM. But it is rather uncomfortable to sustain head-bobbing or foot-tapping at this rapid pace. Moreover, the chorus is basically a repeat of the same twelve-bar blues pattern of the verse, with the same pacing of melodic and harmonic content. As a result, it seems more analytically robust to describe the chorus as having a tempo of 112 BPM with a double-time feel – thereby capturing the conflict between the drum pattern and the implied beat based on the unaltered pacing of harmonic and melodic content – rather than to simply say the tempo has increased to 224 BPM, which does not account for the lack of speed change in the harmony and melody.

The notion that the tactus of a song tends to stay close to the 110–125 BPM range may seem overly restrictive, perhaps no less so than the alternative of saying the kick-snare rate always determines tempo. But unlike other musical styles that have primarily instrumental textures, rock texture is almost exclusively based around a vocal melody. Perhaps because the pacing of lyrics is constrained by ideal rates of speech delivery, the pacing of melodic content in rock turns out to be relatively stable. Thus, while music cognition researchers report that the range of tactus perception lies between 30 BPM and 240 BPM (an eightfold increase), the range of variation for the pacing of pitch-based content in rock is much more narrow. As evidence, cover versions of songs rarely shift the speed of the vocal melody more than a small amount, much less than twice or half the original rate. For example, Cream’s original version of “Sunshine of Your Love” (1967) has a clear tempo of 116 BPM in ![]() with a normal drum feel. In contrast, the cover by Fudge Tunnel (1991) may at first sound extremely slower, but the rate of vocal delivery in Fudge Tunnel’s cover is not much slower than the original. The reason Fudge Tunnel’s version sounds especially slow is the lumbering drum pattern, which conveys a half-time feel against the more moderate pacing of the melodic and harmonic material. Thus, by referring to the cover as a half-time

with a normal drum feel. In contrast, the cover by Fudge Tunnel (1991) may at first sound extremely slower, but the rate of vocal delivery in Fudge Tunnel’s cover is not much slower than the original. The reason Fudge Tunnel’s version sounds especially slow is the lumbering drum pattern, which conveys a half-time feel against the more moderate pacing of the melodic and harmonic material. Thus, by referring to the cover as a half-time ![]() at 100 BPM, we capture both the change in the drum feel as well as the only moderate change in harmonic and melodic pacing.

at 100 BPM, we capture both the change in the drum feel as well as the only moderate change in harmonic and melodic pacing.

Meter and Measures

While the tactus is the most central pulse layer, also of interest is the entire hierarchy of pulse layers, i.e., meter. The meter of a musical composition is traditionally conveyed through its time signature, usually classified into two categories based on (1) the number of beats per measure, usually duple, triple, or quadruple; and (2) the number of regularly occurring, equal divisions of this beat, either two (simple) or three (compound). This scheme results in six standard time signatures: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Although it is not impossible to classify meter in rock using only this basic system, some addendums are useful to better capture typical pulse hierarchies. We have already seen, for example, that the rhythmic framework of some songs involves conflicting pulse information, such as half-time or double-time feels. Time signatures could be adapted to account for this conflict, such as labeling half-time as ![]() or double-time as 8/8. But trying to incorporate drum feels into the time signature becomes problematic in cases other than

or double-time as 8/8. But trying to incorporate drum feels into the time signature becomes problematic in cases other than ![]() , such as

, such as ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

The other complicating factor is the widespread use of swing at different metric levels. Swing, which divides the beat into two unequal values, is a common feature of jazz and related styles that predate rock, of course. In jazz, the unevenness of the swing – which primarily occurs between eighth notes – can range from ratios of 1.05:1 to 3.5:1 or higher.5 In contrast, swing in rock generally conforms to a 2:1 ratio, equivalent to a quarter-note triplet followed by an eighth-note triplet. In this regard, swing in rock represents another standardization of rhythmic parameters from earlier styles.

Because swing in rock typically follows a 2:1 ratio, it can be difficult to distinguish between swing and compound meter. The Elvis Presley song “Stuck on You” (1960), for example, is a rolling twelve-bar blues with a quadruple beat at 132 BPM. It is possible to consider this song as in ![]() , with the drum fill at 1:04 confirming the division of the beat into three equal parts. But the pervasive “long-short” division of the beat, most noticeable in the hi-hat and piano parts, exemplifies a classic “shuffle” rhythm, which rock musicians understand as a type of triplet division of

, with the drum fill at 1:04 confirming the division of the beat into three equal parts. But the pervasive “long-short” division of the beat, most noticeable in the hi-hat and piano parts, exemplifies a classic “shuffle” rhythm, which rock musicians understand as a type of triplet division of ![]() with the middle triplet missing. The pervasive use of shuffle in rock songs leads to a general trend by rock musicians to conceptualize triply divided quadruple meters not as

with the middle triplet missing. The pervasive use of shuffle in rock songs leads to a general trend by rock musicians to conceptualize triply divided quadruple meters not as ![]() but rather as

but rather as ![]() with swung eighth notes. Consequently,

with swung eighth notes. Consequently, ![]() has become a deprecated meter in rock, even when a consistent underlying triple subdivision exists.6

has become a deprecated meter in rock, even when a consistent underlying triple subdivision exists.6

The deprecation of ![]() in favor of a swung

in favor of a swung ![]() does not mean that compound meters in rock are deprecated as a rule. To the contrary,

does not mean that compound meters in rock are deprecated as a rule. To the contrary, ![]() is the most appropriate time signature for many songs. In rock, though,

is the most appropriate time signature for many songs. In rock, though, ![]() and

and ![]() are dissimilar types of compound meter. Although we could think of a

are dissimilar types of compound meter. Although we could think of a ![]() measure as twice as long as a

measure as twice as long as a ![]() measure, the fairly consistent pacing of harmonic and melodic material in rock (discussed above) suggests that it is preferable to maintain consistent measure lengths in terms of absolute time when possible. In other words, given a chunk of time that we are calling a measure, dividing that time into four triply divided beats is very different from dividing that same amount of time into two triply divided beats.

measure, the fairly consistent pacing of harmonic and melodic material in rock (discussed above) suggests that it is preferable to maintain consistent measure lengths in terms of absolute time when possible. In other words, given a chunk of time that we are calling a measure, dividing that time into four triply divided beats is very different from dividing that same amount of time into two triply divided beats.

As an illustration, consider two versions of the song “With a Little Help From My Friends.” The original version by the Beatles (1967) is a clear ![]() shuffle – or

shuffle – or ![]() perhaps – at a tempo of 110 BPM and measure lengths of 2.2 seconds. In his 1968 cover, Joe Cocker sings the melody at only a slightly slower pace, the same amount of music now lasting 2.5 seconds. If we take bar lengths to be the same between these two versions because the melodic pacing is roughly the same, Cocker’s version indicates a

perhaps – at a tempo of 110 BPM and measure lengths of 2.2 seconds. In his 1968 cover, Joe Cocker sings the melody at only a slightly slower pace, the same amount of music now lasting 2.5 seconds. If we take bar lengths to be the same between these two versions because the melodic pacing is roughly the same, Cocker’s version indicates a ![]() time signature, with only one kick and snare per bar. Note that if we consider the Beatles version as in

time signature, with only one kick and snare per bar. Note that if we consider the Beatles version as in ![]() , it would be unreasonable to hear the eighth note as tactus, since its rate of 330 BPM lies well above the ceiling for tempo perception. Yet in Cocker’s version, the metric level that aligns most closely with tempo norms for rock is the eighth note, at 145 BPM. That said, the kick-snare rate in Cocker’s version is around 48 BPM, which still lies within the range of tempo perception. This conflict between an eighth-note tactus and a kick-snare pattern at a slower yet still viable rate is a hallmark of

, it would be unreasonable to hear the eighth note as tactus, since its rate of 330 BPM lies well above the ceiling for tempo perception. Yet in Cocker’s version, the metric level that aligns most closely with tempo norms for rock is the eighth note, at 145 BPM. That said, the kick-snare rate in Cocker’s version is around 48 BPM, which still lies within the range of tempo perception. This conflict between an eighth-note tactus and a kick-snare pattern at a slower yet still viable rate is a hallmark of ![]() time signatures in rock, paralleling similar conflict between metric layers found in a half-time

time signatures in rock, paralleling similar conflict between metric layers found in a half-time ![]() .

.

Another subtle but important aspect of the rhythmic organization in Cocker’s cover is the pervasive swing on the sixteenth-note level, most noticeable in the ride cymbal. Whereas eighth-note swing in ![]() can be captured by the time signature (as

can be captured by the time signature (as ![]() ), it is impossible to represent sixteenth-note swing in

), it is impossible to represent sixteenth-note swing in ![]() via some alternative time signature. Because sixteenth-note swing is not possible to designate through the time signature alone, rock musicians typically consider swing overall as a separate aspect of meter than the time signature. Sixteenth-note swing may also occur in

via some alternative time signature. Because sixteenth-note swing is not possible to designate through the time signature alone, rock musicians typically consider swing overall as a separate aspect of meter than the time signature. Sixteenth-note swing may also occur in ![]() , as heard in “Rag Doll” by Aerosmith (1987), “Sunday Morning” by Maroon 5 (2002), and “Say You’re Sorry” by Sara Bareilles (2010). When sixteenth-note swing occurs in

, as heard in “Rag Doll” by Aerosmith (1987), “Sunday Morning” by Maroon 5 (2002), and “Say You’re Sorry” by Sara Bareilles (2010). When sixteenth-note swing occurs in ![]() , the first and third sixteenth notes of each beat are longer than the second and fourth sixteenth notes, while the eighth notes evenly divide the quarter-note beat. (Eighth-note swing and sixteenth-note swing are thus mutually exclusive.)

, the first and third sixteenth notes of each beat are longer than the second and fourth sixteenth notes, while the eighth notes evenly divide the quarter-note beat. (Eighth-note swing and sixteenth-note swing are thus mutually exclusive.)

In addition to ![]() and

and ![]() , the next most useful time signature for rock is

, the next most useful time signature for rock is ![]() . These three time signatures –

. These three time signatures – ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() – form the core set of time signatures suitable for classifying meter in rock, since they represent the three most maximally contrasting ways to divide a measure: two parts divided into two subparts (

– form the core set of time signatures suitable for classifying meter in rock, since they represent the three most maximally contrasting ways to divide a measure: two parts divided into two subparts (![]() ), two parts divided into three subparts (

), two parts divided into three subparts (![]() ), and three parts divided into two subparts (

), and three parts divided into two subparts (![]() ). Theoretically, it is possible to consider a fourth category that divides the measure into three parts and three subparts, i.e.,

). Theoretically, it is possible to consider a fourth category that divides the measure into three parts and three subparts, i.e., ![]() . But potential cases of

. But potential cases of ![]() in rock, such as “A Taste of Honey” by the Beatles (1963) or “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” by Neil Young (1970), are more commonly conceptualized as songs in

in rock, such as “A Taste of Honey” by the Beatles (1963) or “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” by Neil Young (1970), are more commonly conceptualized as songs in ![]() with eighth-note swing, since (as with

with eighth-note swing, since (as with ![]() ) the eight-note layer is typically too fast to be felt as a viable tactus.

) the eight-note layer is typically too fast to be felt as a viable tactus.

Rock songs in ![]() are far less common than those in

are far less common than those in ![]() or

or ![]() , perhaps because of the difficulty in reconciling a standard drumbeat with the odd number of beats in a measure. The normal drum pattern in

, perhaps because of the difficulty in reconciling a standard drumbeat with the odd number of beats in a measure. The normal drum pattern in ![]() , for example, is a kick on beat 1 and snare on beat 3, which lacks the evenly spaced alternation between kick and snare found in other meters. As a workaround, drummers can shift the kick-snare pattern to a higher or lower level of the metric hierarchy, akin to a half-time or double-time feel. The song “Take It to the Limit” by the Eagles (1975), for example, has a strong tactus at 90 BPM, yet the kick and snare at the beginning occur every three beats. It is doubtful that the kick and snare distance is perceived as the true beat rate here, given it lies on the threshold of beat perception, so it makes more sense to consider the song in

, for example, is a kick on beat 1 and snare on beat 3, which lacks the evenly spaced alternation between kick and snare found in other meters. As a workaround, drummers can shift the kick-snare pattern to a higher or lower level of the metric hierarchy, akin to a half-time or double-time feel. The song “Take It to the Limit” by the Eagles (1975), for example, has a strong tactus at 90 BPM, yet the kick and snare at the beginning occur every three beats. It is doubtful that the kick and snare distance is perceived as the true beat rate here, given it lies on the threshold of beat perception, so it makes more sense to consider the song in ![]() with a half-time feel rather than a slow

with a half-time feel rather than a slow ![]() . Further support for the

. Further support for the ![]() hearing appears later in the leadup to the chorus (1:12), where the drums revert to a normal

hearing appears later in the leadup to the chorus (1:12), where the drums revert to a normal ![]() pattern.

pattern.

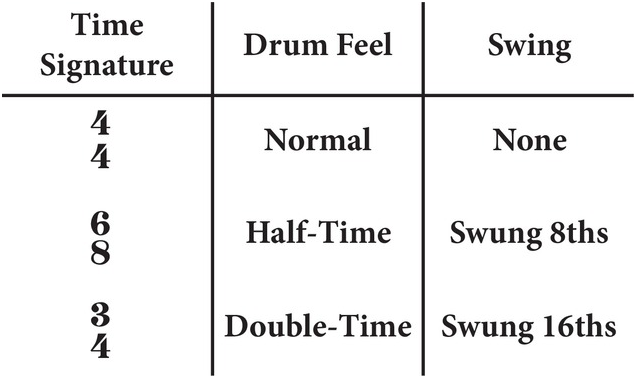

Taking a global view, Figure 11.1 provides a chart of the most common metric parameters found in rock. This chart classifies typical rhythmic organizations via three categories, each of which has three options: (1) the time signature, which is usually ![]() ,

, ![]() , or

, or ![]() ; (2) the drum feel, which may be normal time, half time, or double time; and (3) the level of swing, which may be none, eighth notes, or sixteenths. A song could thus be a double-time

; (2) the drum feel, which may be normal time, half time, or double time; and (3) the level of swing, which may be none, eighth notes, or sixteenths. A song could thus be a double-time ![]() with sixteenth-note swing, such as “Up from Below” by Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros (2009); a half-time

with sixteenth-note swing, such as “Up from Below” by Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros (2009); a half-time ![]() with eighth-note swing, such as “Grapevine Fires” by Death Cab for Cutie (2008); or a double-time

with eighth-note swing, such as “Grapevine Fires” by Death Cab for Cutie (2008); or a double-time ![]() with no swing, such as “Synchronicity I” by the Police (1983). From the standpoint of traditional time signatures, the chart in Figure 11.1 may seem like a radical simplification, but it represents over twenty viable combinations – far more than the six basic time signatures of

with no swing, such as “Synchronicity I” by the Police (1983). From the standpoint of traditional time signatures, the chart in Figure 11.1 may seem like a radical simplification, but it represents over twenty viable combinations – far more than the six basic time signatures of ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() – before the consideration of irregular meters.

– before the consideration of irregular meters.

11.1 Chart of common metric parameters found in rock

An in-depth discussion of irregular meters in rock, such as complex or changing meters, is beyond the scope of the current chapter. That said, it seems worth providing one example to model a general approach. The song “Whipping Post” by the Allman Brothers Band (1969) is famous for the odd rhythmic structure of its main riff, which involves some grouping of eleven. This metric irregularity disappears once the vocals enter (0:26), as the verse material settles into a repeated grouping pattern of three at 200 BPM. This fast tempo is somewhat uncomfortable to sustain as a regular tactus, so many listeners may find themselves conflicted between this rate and the slower rate of 67 BPM. This tactus conflict is the hallmark of a ![]() meter, and, perhaps not surprisingly, the leadup to the chorus and the chorus itself (0:56) present a standard

meter, and, perhaps not surprisingly, the leadup to the chorus and the chorus itself (0:56) present a standard ![]() drum pattern. The song overall, therefore, seems to be in

drum pattern. The song overall, therefore, seems to be in ![]() , with the verse feeling more energetic due to the surface rhythms of the bass and drum parts. More importantly, we can understand the opening riff not as some long span of eleven beats but rather as a bar of

, with the verse feeling more energetic due to the surface rhythms of the bass and drum parts. More importantly, we can understand the opening riff not as some long span of eleven beats but rather as a bar of ![]() followed by a bar of

followed by a bar of ![]() – this

– this ![]() bar resulting from the deletion of an eighth note – which reconciles the riff’s 3+3+3+2 grouping with typical metric organizations found in rock. The additional complicating factor arises from the double-time pattern that the drums play against this

bar resulting from the deletion of an eighth note – which reconciles the riff’s 3+3+3+2 grouping with typical metric organizations found in rock. The additional complicating factor arises from the double-time pattern that the drums play against this ![]() meter, with the kick on the first of every three eighth notes. In general, irregular meters in rock can be understood as some variation on the strategy seen here, where a beat or sub-beat is deleted from or added to one of the more regular metric organizations shown in Figure 11.1.

meter, with the kick on the first of every three eighth notes. In general, irregular meters in rock can be understood as some variation on the strategy seen here, where a beat or sub-beat is deleted from or added to one of the more regular metric organizations shown in Figure 11.1.

Syncopation and Stress

In traditional conceptions of meter, an important distinction exists between strong and weak beats. In ![]() , for example, beats 1 and 3 are considered strong – i.e., the metric locations that are normally accented – while beats 2 and 4 are weak – i.e., those that are normally unaccented.7 A similar pattern of strong and weak is understood to continue through higher and lower levels of the metric hierarchy. The first eighth note of a beat, for example, is considered strong while the second is weak. The musical surface typically reinforces these patterns of strong and weak so as to clearly convey the meter; otherwise, metric confusion may occur.

, for example, beats 1 and 3 are considered strong – i.e., the metric locations that are normally accented – while beats 2 and 4 are weak – i.e., those that are normally unaccented.7 A similar pattern of strong and weak is understood to continue through higher and lower levels of the metric hierarchy. The first eighth note of a beat, for example, is considered strong while the second is weak. The musical surface typically reinforces these patterns of strong and weak so as to clearly convey the meter; otherwise, metric confusion may occur.

In contrast, meter in rock can appear organized in a somewhat opposite manner. In a standard ![]() drumbeat, for example, the snare is almost always louder than the kick, and the spectral energy of a snare lies within a frequency range to which the human ear is especially sensitive. As a result, beats 2 and 4 are arguably more accented in rock on a regular basis than beats 1 and 3. This is not to imply that rock musicians do not recognize the structural importance of the downbeat. Rather, expectations in rock with regard to recurring patterns of stress and accent are often different from traditional norms. (This difference is highlighted by the familiar joke among popular musicians that “friends don’t let friends clap on beats 1 and 3.”)

drumbeat, for example, the snare is almost always louder than the kick, and the spectral energy of a snare lies within a frequency range to which the human ear is especially sensitive. As a result, beats 2 and 4 are arguably more accented in rock on a regular basis than beats 1 and 3. This is not to imply that rock musicians do not recognize the structural importance of the downbeat. Rather, expectations in rock with regard to recurring patterns of stress and accent are often different from traditional norms. (This difference is highlighted by the familiar joke among popular musicians that “friends don’t let friends clap on beats 1 and 3.”)

Off-beat accents are not exclusive to rock music, of course. Styles ranging from jazz to bluegrass have long traditions of putting stress on what are traditionally considered weak beats or weak portions of the beat. More broadly, syncopation – as a rhythmic pattern that goes against the beat structure – dates back in European music to at least the Middle Ages. That said, certain types of syncopation and non-traditional accent patterns are particularly endemic to rock, as found in its melodic and harmonic material.

Perhaps the most characteristic rhythmic feature of a rock melody is the anticipatory syncopation. In essence, an anticipatory syncopation is an event that occurs prior to a relatively stronger beat but, unlike a regular anticipation, without a new event on that stronger beat. The length of the anticipation is most typically an eighth note, although sixteenth-note anticipatory syncopations are also common. One example can be found in the song “Sweet Caroline” by Neil Diamond (1969). When the title line is sung at the beginning of the famously anthemic chorus (1:02), linguistic stress occurs on the word “sweet” and the first and third syllables of “Caroline.” But while “sweet” and the first syllable of “Caroline” are sung on the beat, the last syllable of “Caroline” is sung on an eighth note prior to the following downbeat, without any new melodic content on that downbeat. From the standpoint of traditional text setting, this anticipation by the syllable “–line” may seem odd, since the linguistic stress does not align with the metric stress.

What are we to make of this situation? One view is that rock melodies regularly displace linguistically stressed syllables, typically forward in time, from locations of metric stress. In other words, the third syllable of “Caroline” belongs to the next downbeat on a deeper level, but the musical surface shifts that linguistically stressed note away from the location of metric stress. The reason for this forward shift, we might hypothesize, is perhaps to make the melody more rhythmically interesting. Another view is that rock simply has no priority for aligning linguistically stressed events with strong metric locations. In ![]() , for example, the metric distribution of note onsets in rock melodies appears to be essentially uniform, with equal probability of a note occurring on any eighth note of the measure.8 By this view, the last syllable of “Caroline” does not belong to the following downbeat in any sense; instead, it simply belongs where it is. The metric location of melodic notes may be a function of speech patterns. It certainly seems more natural to sing the word “Caroline” as it is in this chorus, rather than evenly spacing out each syllable.

, for example, the metric distribution of note onsets in rock melodies appears to be essentially uniform, with equal probability of a note occurring on any eighth note of the measure.8 By this view, the last syllable of “Caroline” does not belong to the following downbeat in any sense; instead, it simply belongs where it is. The metric location of melodic notes may be a function of speech patterns. It certainly seems more natural to sing the word “Caroline” as it is in this chorus, rather than evenly spacing out each syllable.

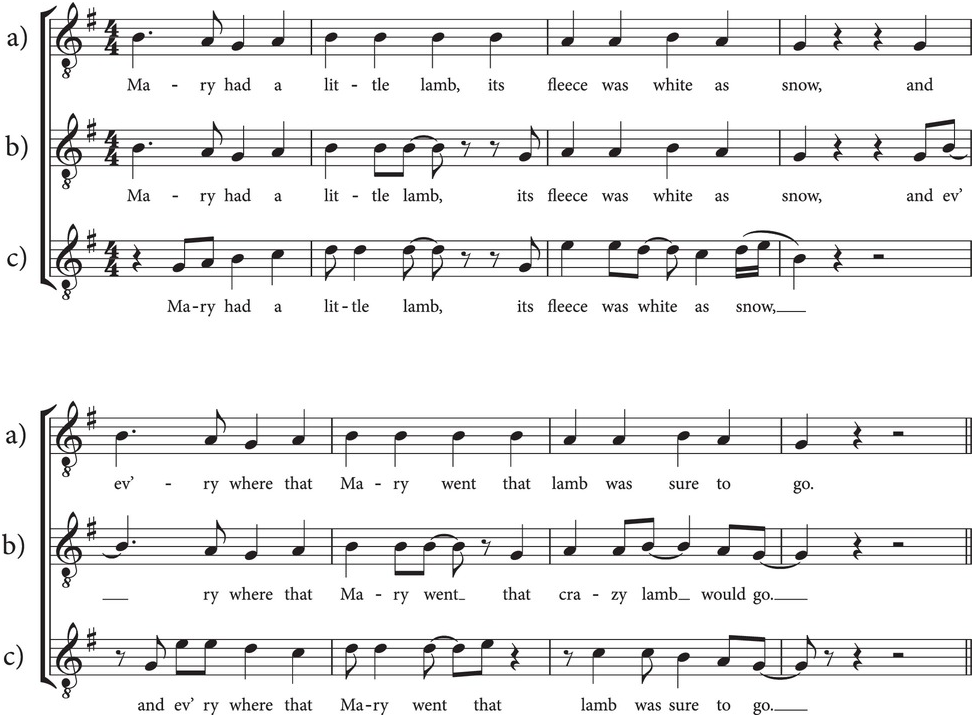

Some evidence for the first view can be found when examining how rock musicians treat traditional melodies. The nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” is a useful case study, since its melody (Example 11.2a) is well known and simple, and has been the basis of more than one rock song. Consider, for example, the version heard on Chubby Checker’s 1959 song “The Class” (0:22; Example 11.2b), which hews closely to the original melody. The biggest differences are within the rhythmic domain. In particular, all but one of the rhythmic divergences involve anticipatory syncopation: “lamb” in the second measure, the first syllable of “ev’ry” in the fifth measure, “went” in the sixth measure, “lamb” in the seventh measure, and “go” in the last measure – each has been displaced forward in time by an eighth note. Generally speaking, there appears to be a preference for anticipatory syncopation at the beginning of a phrase but especially at the end of a phrase, similar to the strategy found in “Sweet Caroline.” The consequent effect is a lack of finality, as the misalignment of linguistic stress with metric strong points thwarts a solid sense of resolution.

11.2 Three versions of the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

(a) Traditional version

(b) Version from Chubby Checker’s song “The Class” (1959)

(c) Version from the Wings’ song “Mary Had a Little Lamb” (1972)

A similar strategy can be found in Paul McCartney’s version (Example 11.2c), released by Wings in 1972. McCartney significantly changes the pitch structure of the melody, but the rhythmic relationship between his version and the original remains clear. Like Chubby Checker’s version, anticipatory syncopations are most commonly found at the ends of phrases or subphrases. But in McCartney’s setting, the anticipatory syncopations cascade further back toward the beginning of each phrasal unit. Rather than just syncopating “lamb” in the second measure, for example, McCartney syncopates the second syllable of “little” as well as “lamb.” Similarly, each syllable of “white as snow” now occurs an eighth note earlier than in the original version. By enlarging the zone of anticipatory syncopation prior to phrase endings, McCartney’s version further increases the sense of being off-balance, thereby avoiding strong melodic closure.

Many melodies in rock employ anticipatory syncopation to such an extreme that almost every note occurs between beats. Examples include the verse material to “Taxman” by the Beatles (1966), “Wrapped Around Your Finger” by the Police (1983), and “Smells Like Teen Spirit” by Nirvana (1991). Similar to how the standard rock drumbeat puts stress on beat locations traditionally considered weak, therefore, rock melodies often put stress on divisions of the beat that are traditionally considered weak. In an unaccompanied setting, such high levels of melodic syncopation might be untenable, causing confusion as to the beat location. Since the metric structure of the song is so clearly conveyed by the drumbeat, though, perhaps there is less onus in rock for the melody to express the meter and more freedom to play against it. In other words, the evolution of typical rhythmic patterns in rock melodies may be the result of having the beat clearly expressed by the dedicated rhythmic layer of the drums.

In contrast to melodic events, harmonic events in rock align fairly closely with traditional rhythmic norms. Generally speaking, chords in rock change every half measure, measure, or two measures. In the overwhelming majority of cases, moreover, these chord changes occur on the beat. Indeed, the downbeat is by far the most common metric location for a new harmony in rock. Because there are so many other counterforces in rock creating stress on traditionally weak beats and weak divisions of the beat, perhaps it is imperative for the harmonic layer to stress the beginnings of measures.

That said, syncopation – particularly anticipatory syncopation – is not uncommon for harmonies in rock. These are sometimes referred to as a “push” by rock musicians, since the chord seems “pushed” forward by an eighth note prior to the beat. In general, anticipatory syncopation in rock harmony tends to occur on weaker portions of the measure or hypermeasure. For example, if a song section has a harmonic rhythm of one chord per measure, the push usually occurs on the harmony in the second and fourth measure, as heard in the verses of “She Will Be Loved” by Maroon 5 (2002) and “Fire Meet Gasoline” by Sia (2014). Similarly, if a song section has a harmonic rhythm of two chords per measure, the push usually occurs on the chord midway through the measure, as heard in the chorus of “Peace of Mind” by Boston (1976) and the verse of “Jesus Take the Wheel” by Carrie Underwood (2005). Note that this more limited approach to anticipatory syncopation in the harmonic domain shows a preference for aligning harmonies with the beginnings of measures and hypermeasures, presumably so as not to overly disturb the underlying metric structure.

Another type of syncopation frequently encountered in the accompanimental pattern of a rock song is the cross rhythm. Typically, cross rhythms involve multiple groupings of three eighth notes in a ![]() meter with one or two groupings of two eighth notes that create a repeating one-bar or two-bar unit. A common example is the 3+3+2 “tresillo” rhythm (also found in African and Latin American music), such as at the beginning of “Swingtown” by the Steve Miller Band (1977) and “She Goes Down” by Mötley Crüe (1989). Note that the 3+3+2 cross rhythm is similar to a push on beat 3 in

meter with one or two groupings of two eighth notes that create a repeating one-bar or two-bar unit. A common example is the 3+3+2 “tresillo” rhythm (also found in African and Latin American music), such as at the beginning of “Swingtown” by the Steve Miller Band (1977) and “She Goes Down” by Mötley Crüe (1989). Note that the 3+3+2 cross rhythm is similar to a push on beat 3 in ![]() , which causes the second chord to enter on the “and” of beat 2. The groupings of threes can also be extended to create a 3+3+3+3+2+2 “double tresillo” pattern, as heard at the beginning of “Shoot to Thrill” by AC/DC (1980) and “Runaway” by Bon Jovi (1984). Rotations of the double tresillo are also possible, such as the 2+3+3+3+3+2 pattern heard at the beginning of “Faithfully” by Journey (1983). Note that in all these cases, the groupings of three do not cut across important structural boundaries, such as the beginning of a hypermeasure or two-bar unit. Instead, the syncopation created by the cross rhythm is regularly resolved on every downbeat or every other downbeat, which helps maintain the clarity of the underlying metric organization within the harmonic domain.

, which causes the second chord to enter on the “and” of beat 2. The groupings of threes can also be extended to create a 3+3+3+3+2+2 “double tresillo” pattern, as heard at the beginning of “Shoot to Thrill” by AC/DC (1980) and “Runaway” by Bon Jovi (1984). Rotations of the double tresillo are also possible, such as the 2+3+3+3+3+2 pattern heard at the beginning of “Faithfully” by Journey (1983). Note that in all these cases, the groupings of three do not cut across important structural boundaries, such as the beginning of a hypermeasure or two-bar unit. Instead, the syncopation created by the cross rhythm is regularly resolved on every downbeat or every other downbeat, which helps maintain the clarity of the underlying metric organization within the harmonic domain.

Conclusion

As put forward here, rhythm and meter in rock involve different norms than do other musical styles, especially as compared to classical music. These differences include expectations about typical beat rates, ways in which the beat is divided, and patterns of stress. Many of these normative characteristics can be traced to earlier popular styles, such as jazz, bluegrass, blues, and gospel. But as a musical melting pot, paralleling similar trends of cultural assimilation in the United States, rock music can be viewed as a homogenization of these tributary styles into an amalgam meant for mass-market appeal.

It would be remiss to close without some mention of the role technology played in this process. Not coincidentally, the birth of rock and roll occurred in tandem with the birth of the multitrack recording studio. Rock musicians were thus able to create arrangements and performances entirely free from musical notation. Other styles – such as folk and blues music – existed primarily as oral traditions prior to rock, of course. But it was in the cauldron of the recording studio where these styles came together. The lack of any requirement to notate the music allowed, arguably, for more complex rhythmic and metric structures to proliferate, most notably in the heavily syncopated melodies of rock. Looking forward, as computer-based digital audio workstations (e.g., Ableton Live, Logic Pro) increasingly supplant the traditional recording studio as the primary setting for musiccreation, technological changes will undoubtedly continue to transform the rhythmic and metric organization of popular music in new and revolutionary ways.

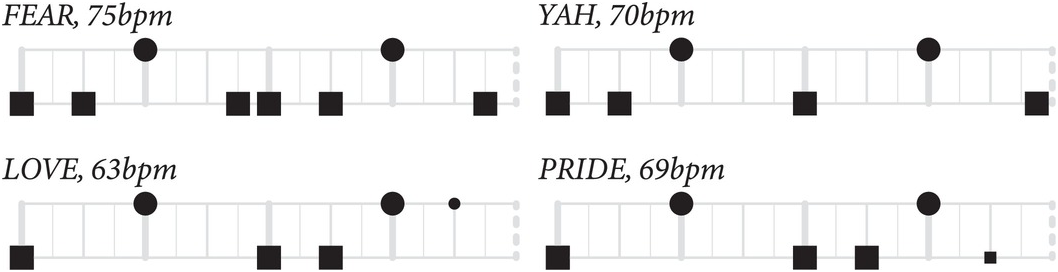

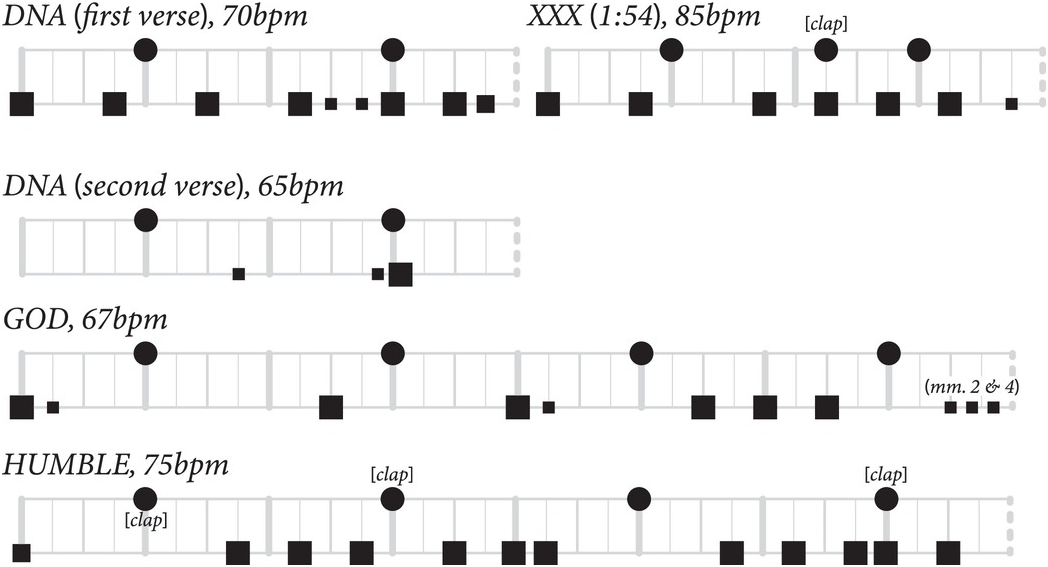

One can observe two trends in music theory and analysis in recent decades, partly in response to the criticism of New Musicology in the 1990s: increased attention to the topic of rhythm and meter and increased attention to repertoires of popular music.1 These two trends have been mutually reinforcing. In the 1980s and 1990s, scholars argued that engaging with popular music would push music scholarship beyond its traditional focus on pitch organization. The impetus for this expansion was popular music’s distinctive rhythms endowed by the influences (or appropriations) of the musics of the African diaspora. These rhythmic features include pervasive anticipatory syncopation,2 unequal and often maximally even rhythmic groupings,3 and a tendency toward metric saturation.4 Given these trends, it would seem that rap music would hold particular interest to music scholars, and indeed, the study of rap music’s sonic organization has also flourished.5 Yet it still stands somewhat apart, a redux of the relationship of popular music vis-à-vis classical music a generation ago: existing analytic methods (rhythmic or otherwise) are either incompatible with rap music or provide seemingly little illumination. Kyle Adams has documented some ontological reasons for this disconnect: rap music always has a texted component, but the kinds of text-music correspondences analysts find so appealing are scant. Rap music also has an instrumental component (termed “the beat”), but that beat, often with many creators and composed of disparate samples of previous recordings, synthesizers, and programmed drums, would seem not to “work toward a singular expressive purpose.”6