One can observe two trends in music theory and analysis in recent decades, partly in response to the criticism of New Musicology in the 1990s: increased attention to the topic of rhythm and meter and increased attention to repertoires of popular music.1 These two trends have been mutually reinforcing. In the 1980s and 1990s, scholars argued that engaging with popular music would push music scholarship beyond its traditional focus on pitch organization. The impetus for this expansion was popular music’s distinctive rhythms endowed by the influences (or appropriations) of the musics of the African diaspora. These rhythmic features include pervasive anticipatory syncopation,2 unequal and often maximally even rhythmic groupings,3 and a tendency toward metric saturation.4 Given these trends, it would seem that rap music would hold particular interest to music scholars, and indeed, the study of rap music’s sonic organization has also flourished.5 Yet it still stands somewhat apart, a redux of the relationship of popular music vis-à-vis classical music a generation ago: existing analytic methods (rhythmic or otherwise) are either incompatible with rap music or provide seemingly little illumination. Kyle Adams has documented some ontological reasons for this disconnect: rap music always has a texted component, but the kinds of text-music correspondences analysts find so appealing are scant. Rap music also has an instrumental component (termed “the beat”), but that beat, often with many creators and composed of disparate samples of previous recordings, synthesizers, and programmed drums, would seem not to “work toward a singular expressive purpose.”6

I would add other hindrances of particular concern for theories and analyses of rhythm and meter in rap music. At the risk of broadly generalizing, recent scholarship on popular music has addressed primarily metric or hypermetric additions or truncations at the macro-level.7 At the meso-level, it has addressed primarily rhythmic complexities such as non-isochronous meters8 and durations or groupings with interesting mathematical features such as maximal evenness or Euclidean rhythms at the meso-level.9 At the micro-level, it has addressed the deployment of swing10 and minute temporal relationships among collaborating musicians.11

Most rap music simply does not partake of these complexities. Instead, rap music has a way of disguising its complexities in aspects of organization that rap discourse presents as simple. In this chapter I will address two such aspects: patterning of the kick and snare streams in rap’s instrumental beats and alignment of rap’s syllables with the meter. In each case, rap music discourse would suggest little to hear here. As with the backbeat in pop-rock music, the kick and snare in rap music are thought to alternate, with kick events on beats 1 and 3 and snare events on beats 2 and 4. This feature is considered so invariant that the kick and snare of any rap track is given a single, onomatopoeic name, the boom-bap. Similarly, the placement of syllables in a rap verse is thought to align with meter in predictable ways, so much so that a rapper who does not align with the meter is delegitimized as “off-beat.” In what follows, I will challenge the conventional account of both of these features by discussing selected tracks of a single recent album of rap music, Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. from 2017. This album has the distinction of being the only musical work to win both the Grammy Award for album of the year across all genres and the Pulitzer Prize in Music, an award previously given to contemporary classical or jazz composers. My aim in this undertaking is twofold: first, to demonstrate some subtle rhythmic organization in contemporary rap music, and, second, to demonstrate how an engagement with contemporary rap music might refine methods for the analysis of popular music that has, to date, been primarily focused on pop-rock.12

Drum Textures in DAMN.

Percussive sounds, whether sampled, programmed, or performed, form the rhythmic skeleton of rap music. Some tracks, such as Mobb Deep’s “The Infamous” and much of A Tribe Called Quest’s “Can I Kick It?,” contain nothing else. Existing scholarship on the backbeat, drawing heavily on Christopher Hasty’s Meter as Rhythm, mostly in reference to pop-rock music, focuses on the quality of motion between successive beats within the meter the backbeat pattern engenders. In Hasty’s approach, indebted to earlier theorists like Moritz Hauptmann and Victor Zuckerkandl, each duration experienced in ongoing music conveys a quality of beginning, anticipation, or continuation. Theorists of the backbeat generally conceive of the low-pitch kick events on beats 1 and 3 as beginning a longer duration. This quality of the kick emerges both from a top-down interpretation that beats 1 and 3 are typically “strong” in a four-beat meter13 and also from a bottom-up perception that the kick is lower and more resonant than the snare. The metric quality of the snare is more contentious. Robin Attas, following Matthew Butterfield, describes the snare as an anacrusis to the kick because its shorter duration and higher pitch contradicts the kick, creating a metric uncertainty that the return of the kick resolves.14

While not drawing on Hasty’s approach, David Temperley also hears the snare as an anticipatory, syncopated displacement of the kick, a syncopation at the half-note level related to the pervasive displacement of rhythms of pop-rock melodies at the quarter-note level.15 In a contrary view, Nicole Biamonte argues that the resonance of the kick links it to the following snare, rendering the snare continuational, not anticipatory.16 Other events in the snare or kick stream might impact the quality of the snare with respect to the kick. If the snare is subdivided (i.e., “boom…bap-bap-boom” rather than “boom…bap…boom”), the relatively longer duration of kick renders the snare anticipatory; if the kick is subdivided (i.e., “boom-boom-bap” rather than “boom-bap”), the relatively longer duration of the snare is continuational. Finally, microtiming variation in the snare might also impact its continuational or anticipatory quality; relatively “late” snares are more anticipatory of the next kick; relatively “early” snares are more continuational of the previous one.17

Here I would stress the extent to which discussion of the quality of the backbeat relies on features of pop-rock music that are diminished or absent in contemporary rap music and other genres influenced by it. Rap music only rarely employs sustained displaced-quarter-note rhythms, the hallmark of pop and rock melodies that provides Temperley’s frame of “backbeat as syncopation,” and, generally, only in sung hooks. And in the era of studio production and digital audio workstations, the backbeat is usually quantized, and thus microtiming has little impact on the character of the snare.18 Most importantly, the drum textures of contemporary rap music differ from those of pop-rock in their sheer number of events. No track on DAMN. has an unadorned backbeat, nor are the ornamentations confined to eighth-note subdivisions. This may be because production of contemporary rap drum textures generally does not require the coordination of skilled drum set players.19

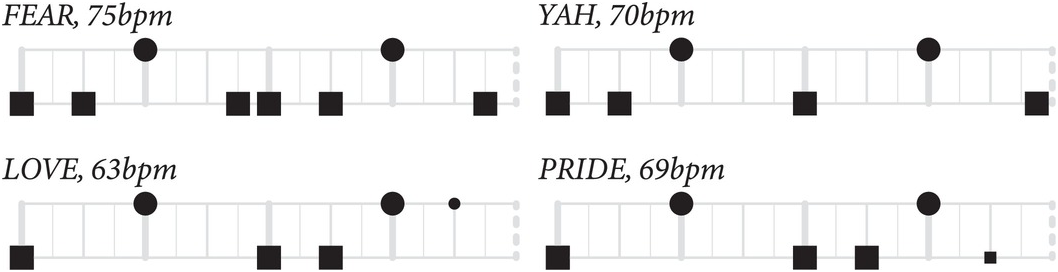

At the most basic level, contemporary rap music complicates the description of the backbeat’s structure of kick-snare alternation. Figure 12.1 visualizes the snare and kick streams of four tracks on the album, all of which are similar. Each plot represents one measure; thicker gray vertical lines represent beats; thinner gray vertical lines represent sixteenth-note positions. Squares represent kick events; circles represent snare events. The size of dot reflects proportion of measures in which the event is heard. Instruments occurring on a particular metric position in only one of each four measures have been discarded. These tracks most closely resemble the typical pop-rock backbeat. They have all the expected events in the kick and snare, but they also have subdividing events in the kick that, according to Biamonte, renders the snare more continuational than anticipatory. Yet none of them exactly repeats the first half of the measure in the second half. Thus, if one argues, like Attas and Butterfield, that the snare of the backbeat is normatively anacrustic, and, like Biamonte, that subdivided kicks render snares continuational, then all of these patterns create one beginning in the measure more prominent than any other. For example, beat 2 in “LOVE.” (and also in the nearly identical “PRIDE.”) anticipates beat 3 because beat 1 is not subdivided, and beat 4 continues beat 3 because beat 3 is subdivided; thus beat 3 (not beat 1!) is the locus of metric energy. Similarly, in “FEAR.” the anticipation of the beat 3 kick on the preceding position again focuses greater attention on beat 3 rather than the downbeat. Only “YAH.,” which is the same as “FEAR.” two beats later, focuses attention on the downbeat. Indeed, none of the drum patterns on DAMN. replicates the first half in their second half. This lends weight to Hasty’s view of meter-as-rhythm: the quality of meter differs from track to track. It also undercuts arguments in prior work that the backbeat can be characterized in any particular way if, at least in contemporary rap music, the prototypical backbeat is rarely heard in an actual track.

12.1 Kick and snare patterning on “FEAR.,” “YAH.,” “LOVE.,” and “PRIDE.” from Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. (2017)

Figure 12.2 uses the same plotting method to show kick and snare patterning in the first two verses of “XXX.” (beginning at 0:26) and the very similar patterning in “DUCKWORTH.”20 These verses of “XXX.” would seem to have anticipatory backbeats because beats 2 and 3 are subdivided, but the kick does the subdividing, not the snare. Biamonte does not address how timbre impacts the quality of a subdividing event, instead assuming (as is reasonable in pop-rock music) that the on-beat and subdividing event will have the same timbre. But in the patterns of “XXX.” and “DUCKWORTH.,” the snare begins to compete with the kick as the locus of attention. In “XXX.,” the longest uninterrupted duration begins with the snare on beat 4, an event that also has an anticipating kick event. Divorced from expectations that beats 1 and 3 are “strong,” one could claim that beats 2 and 4 here have more of the features we associate with loci of metric attention: they are predictable, equally spaced, and begin long durations.

12.2 Kick and snare patterning in “XXX.” (starting at 0:26) and “DUCKWORTH.” Compare to Figure 12.1.

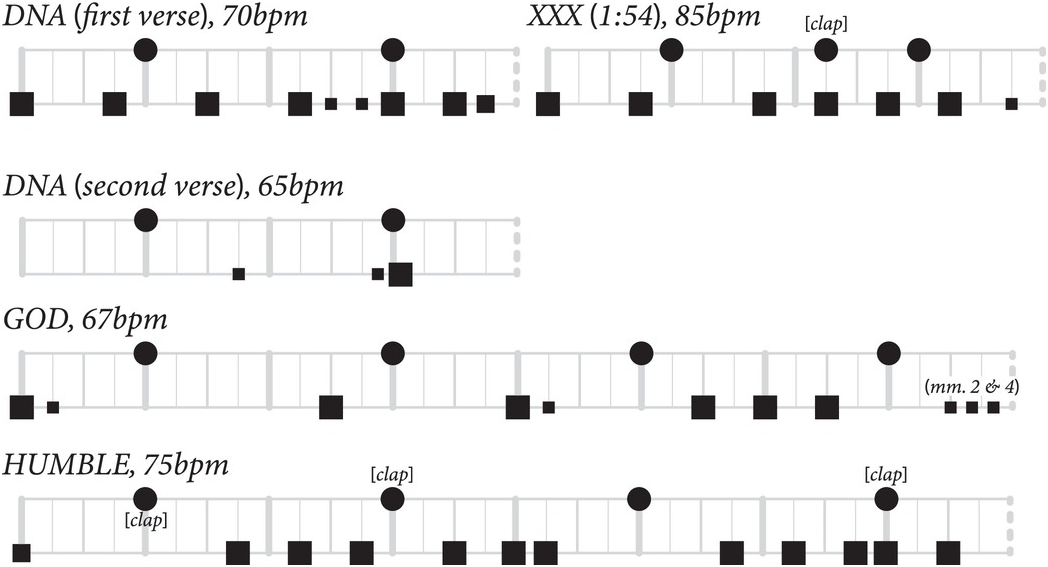

Figure 12.3 shows five other patterns that focus attention more toward the snare than the kick and thereby undermine conventional notions of 1- and 3-weighted quadruple meter. All four have typical snare patterns, and none has typical kick patterns. In the first verse of “DNA.,” the kick approximates the “double tresillo” rhythm (i.e., 16 divided into 3+3+3+3+2+2) described by Butler, Biamonte, Cohn, and others.21 Because this starts on the downbeat, the snare of beat 2 has an anticipatory kick event. A kick fill lends the same to beat 4 in the even-numbered measures. In the last verse of “XXX.,” the kick is highly unpredictable, beginning by suggesting a tresillo before placing four events on the weakest parts of the beat in the middle of the measure. The second verse of “DNA.” has hardly any kick events at all and none on the expected 1 and 3. Finally, the patterns of “GOD.” and “HUMBLE.,” which repeat every two measures rather than every measure, similarly have a standard snare and an unpredictable kick. All these examples undercut many aspects of the current framing of the backbeat: that the kick is an anchoring presence on 1 and 3, that the low register of the kick implies an uninterrupted resonance, and that the snare either anticipates or continues the attentional energy of the kick. I should stress here that I am not suggesting the cumulative metric experience of these tracks undercuts the ![]() meter. Other aspects, especially changes in harmony, bass note, and vocal phrasing, clearly support the meter. What I am suggesting is that contemporary rap drumming does not play the same meter-defining role as in pop-rock music.

meter. Other aspects, especially changes in harmony, bass note, and vocal phrasing, clearly support the meter. What I am suggesting is that contemporary rap drumming does not play the same meter-defining role as in pop-rock music.

12.3 Kick and snare patterning in the first verse of “DNA.,” the last verse of “XXX.,” the second verse of “DNA.,” “GOD.,” and “HUMBLE.” The plots for “GOD.” and “HUMBLE.” show a repeating two-measure pattern.

The patterns discussed thus far account for less than half of those on the album. The rest, to varying degrees, resist explanation as “backbeats” of any kind. Figure 12.4 shows the pattern of “LUST.” Here, the snare is typical. The kick presents two pairs of events, as in a subdivided kick pattern, but the second pair of events is half a beat early, creating an uneven division of the measure, a kind of warped backbeat. Indeed, since neither event is on the beat, it is unclear which takes metric priority: is this a 3+5 grouping in eighth notes? Or perhaps a 7+9 grouping in sixteenths? Figure 12.5 visualizes the streams of “ELEMENT.” Like “LUST.,” there are two pairs of kick events that do not divide the measure evenly; here the second is a half beat late rather than a half beat early. Mirroring the kick, the snare presents two pairs of events, but these do not alternate with the kick. With neither evenly spaced events nor registral alternation, it is unclear what “backbeat” means in this context.

12.4 Kick and snare patterning in “LUST.”

12.5 Kick and snare patterning in “ELEMENT.”

In summary, the “boom-bap” of earlier rap lives on more in discourse around rap than in contemporary practice. Rap’s backbeats have become highly varied in response to changing technologies. Much of the texture is now created in digital audio workstations, and much of the human-generated performance is recorded to a click track, often in different locations. These shifts have seemingly diminished the timekeeping function of the backbeat in pop-rock. I would argue that although prior approaches to the backbeat are not as useful in contemporary repertoires, these changes in drum patterning highlight the utility of Hasty’s contingent and affective approach to meter even more so.

Microtiming in DAMN.

The rhythm of the rapping voice also calls out for an expansion in analytic approaches to microrhythm. To reiterate, the focus of microrhythmic research in popular music has emphasized swing (where events on weak parts of the beat are delayed) and persistent delays in certain parts of the texture (where events on all parts of the beat are delayed). Because of the widespread use of quantized, sampled sounds, one might expect limited microrhythmic play in the rapping voice. Accordingly, in this section, I will demonstrate Lamar’s capacity for near-quantization, but I will also show how his practices can amplify microrhythmic variety and, in some cases, approach the limits of what we understand as musical rhythm.

Alignment in “HUMBLE.,” First Verse

Figure 12.6 plots a transcription of the voice in the first four measures of the first verse of “HUMBLE.,” the lead single of DAMN. Dots in the transcription represent syllables and larger dots represent syllables that are relatively prominent (i.e., accented). I have quantized each syllable to a metric grid of 16 parts per measure (i.e., sixteenth notes); I number these beat classes 0 through 15. As I will show below, this quantization should not be controversial. I consider a syllable accented if it falls on a relatively strong part of the beat (i.e., an even beat class) or if it is a relatively accented syllable in a multisyllabic word such as the first and third syllables of “sandwiches,” “counterfeits,” and “accountant.” Pitch height and syllable duration also play a role in perceived accent.22 Notice that every accented syllable falls either on the beat or at the midpoint of the beat; this total alignment of accent to the stronger parts of the beat extends through the entire verse until the statement of the title word of the song as the last word of the verse at the end of m. 16.

12.6 “HUMBLE.,” mm. 1–4, vocal transcription. Each line transcribes one measure. Points represent syllables quantized to the nearest sixteenth note (i.e., beat class); larger points represent relatively accented syllables.

Lamar extends his alignment of accent with the beat at the macrorhythmic level by precisely aligning syllables with the beat at the microrhythmic level. Figure 12.7 replots the transcription and adds upper rows of dots reflecting the more precise placement of syllables.23 And precise they are: in absolute terms, the vowel onsets of syllables differ from the onset of the nearest beat class, on average, by 20 ms; only a fifth of syllables surpass the 30 ms perceptual threshold proposed by Bregman and Pinker.24 Previous studies can contextualize this degree of alignment with the beat. In a small corpus of thirteen tracks by a variety of rappers, I found an average absolute non-alignment of 89 ms, more than four times that of Lamar’s non-alignment in the first verse of “HUMBLE.”25 What is all the more surprising is that in a corpus of thirty-two other verses by Lamar, the average mean non-alignment is 170 ms, greater than other rap artists and much greater than “HUMBLE.”26 (The discussions of “YAH.” and “ELEMENT.” below will show why Lamar’s average aside from this verse is so high.)

12.7 “HUMBLE.,” mm. 1–4, vocal transcription depicting non-alignment. Upper row of points represents the onset of the vowel of the syllable.

It might seem that there is little of rhythmic or metric interest in “HUMBLE.” – what more could be said of a verse that places accents on every eighth-note position and places syllables on the beat? Figure 12.8 plots the first four measures again, this time annotating rhyme. This placement of rhyme disrupts the rhythmic squareness of other aspects of the flow. In much rap delivery, if there are to be two instances of rhymes in each measure, they typically align with the snare on beats 2 and 4. Here, Lamar rhymes on 1 and 4 and, moreover, terminates the rhyme at a different part of the beat, ending on beat 4 but at the midpoint of beat 1. This use of rhyme to disrupt the regularity of syllable delivery also serves to permeate the meter with prominent events. Figure 12.9 shows a transcription of kick and snare below as in Figure 12.1, as well as the piano riff, the other stream in the accompaniment. Between these three streams, every eighth-note position of the measure is emphasized except for beat class 10. (There is an event in the piano on beat class 10, the first short duration of the <21212> tresillo-like rhythm of the second half of the measure, but I do not consider that “emphasized.”) To saturate the meter at the eighth-note level, Lamar lends prominence to beat class 10 by beginning a rhyme there.

12.8 “HUMBLE.,” mm. 1–4, vocal transcription with rhyme. Black dots represent returning three-syllable rhyme.

12.9 Piano loop (in conventional notation) and kick-and-snare patterning in the loop of “HUMBLE.” Beat class of prominent events also given.

Lateness in “YAH.,” First Verse

Much of the commentary on microtiming in Afri-diasporic music has emphasized swing (see Butterfield, this volume), and “YAH.” would be a compelling place to look for swing in the voice. In a general sense, Lamar is among the contemporary rappers most associated with jazz. His 2015 release To Pimp a Butterfly features collaborations with many noted jazz musicians such as saxophonist Kamasi Washington, pianist Robert Glasper, and bassist Thundercat. More specifically, the kick part of the “YAH.” drum pattern includes a swung anacrusis at the very end of every measure.27 But Lamar’s use of swing is very slight, producing a “beat-upbeat ratio”28 of 1.13:1, far below the typical ratio of 2:1.29 Instead, “YAH.” emphasizes a different aspect of microtiming, that of phase complementarity.

Figure 12.10 shows the last measure of the verse. There is some limited evidence of swing here: the weak parts of the beat do seem shorter than the strong ones, especially the “to-” of “together” and “for-” of “forever,” but it is more apparent that each syllable is substantially late, some by an entire sixteenth note. In absolute terms, the syllables of the line sound, on average, 145 ms after their imputed quantized position, and as much as 225 ms late. This degree of delay is far greater than encountered in previous literature.30 Figure 12.11 shows a boxplot of lateness in the verse, with syllables grouped by measure. The dark line shows the median value of each measure, while the box shows the range of values in the middle half of the data. Here, positive values (in seconds) mean “late” and negative values mean “early.” Most measures average significantly above zero. This persistent lateness amplifies the relaxed vibe of the rest of the track; “YAH.” is one of the slowest tracks on the album and features a resonant but spare accompaniment of just drums, bass guitar contributing two notes per measure, and some sustained synthesizer. Further, a general trend toward beat alignment in the middle is apparent; mm. 3–5 all move toward the beat, while mm. 14–16 move away from it. This might suggest a formal functionality to lateness, with later syllables more likely at the beginnings and endings of verses.

12.10 “YAH.,” mm. 16–17, vocal transcription depicting non-alignment. Compare to Figure 12.7.

12.11 Boxplot of syllable delay with respect to the meter in “YAH.,” second verse, grouped by measure.

The boxplot also reveals an outlier in mm. 8 and 9 that invites interpretation. Much of the verse addresses Lamar’s fame, a standard topic in rap’s braggadocious lyrics. But mm. 8 and 9 stick out: “I’m a Israelite, don’t call me black no more. That word is only a color, it ain’t facts no more.” These lines could be read as an attempt to escape the United States’ persistent racial frame, though I would place more emphasis on the “Israelite” detail. Here, Lamar aligns himself with the Black Israelites movement, whose members see themselves as descendants of the “Lost Tribes” of Israel and typically do not accept the deity of Jesus Christ. Lamar’s cousin Carl Duckworth, mentioned in the following lines, is an adherent. Lamar’s previous music has included frequent allusions to Christianity, and thus these lines would seem to refute, or at least complicate, his Christian allegiances. That these lines include a sudden alignment with the beat might heighten listeners’ attention and inject a note of seriousness in contrast to the relaxed atmosphere of the rest of the verse. Some readers might find this claim ad hoc or unconvincing, but I would argue that whatever its merits, documenting rhythmic structure in this way opens a path to hermeneutic analysis of the interaction of lyric and music (or at least rhythm), topics frequently brought together in analysis of other repertoires but often kept at a distance in considerations of contemporary popular music.

Speech Rhythm in “ELEMENT.,” Third Verse

Finally, I turn attention to the last verse from “ELEMENT.,” one that questions whether Lamar’s voice is persistently rhythmic in the musical sense of the word, that is, a sequence of durations in integral proportions aligned with a beat (see Figure 12.12). The first four lines of the verse are epistrophic, each ending in the questioning “huh?”31 None of these lines aligns with the beat as seen in the first verse of “HUMBLE.,” nor are they displaced from the beat in any predictable way as seen in “YAH.” Instead, the syllables of each have a distinctive pattern. Those of the first measure fan out away from the beat, those of the second are more aligned, those of the third start late and end early, and those of the fourth start very early and end less so. The ambiguity of Lamar’s placement is matched in the reduced beat of these measures, consisting of just the off-kilter kick on beats 1 and 4 (not 3!), with an echo on the “and” of 1 and anticipation on the “and” of 3. The earliness or lateness of a syllable depends on its imputed quantization, which is analytically interpretive. Some readers might dispute the quantization of these measures and thus dispute my characterization of their relation to the metric grid. Here, two simple priorities guide my quantization. The first is to place in a 16-division meter because rappers avow its importance in their practice (Ice-T 2012); the second is to place the last accented syllable of the line (the one before “huh?”) on an even-numbered beat class.

12.12 “ELEMENT.,” third verse, mm. 1–4. Compare to Figures 12.7 and 12.10.

These gradations of alignment suggest that the tempo of the accompanying streams does little to organize Lamar’s placement of syllables. In m. 3, Lamar rushes 15 syllables in the space of 14 sixteenth notes; in the following measure he drags out 13 in the space of nearly 14. Within the lines, the length of consonants affects the durations of syllables more so than would be expected. The longest syllables of mm. 3 and 4 are those that precede the syllable “free,” suggesting that their duration comes in larger part from the necessary time for the fricative “F” and the approximant “R.” Lamar demonstrates through rapping like that heard in “HUMBLE.” that he can place the vowels of successive syllables on divisions of the beat regardless of their initial consonants, but here he seems not to make the effort to do so. Rather than the proportional durations of musical rhythm, Lamar here more closely approaches the rhythms of speech: there is lengthening toward the end of the phrase, but the rhythm of interior syllables is determined more by their phonetic structure and degree of prominence than by an attempt to align with a beat.

Figure 12.13 shows the final eight measures of the verse. Here one sees a gradual return to the kind of rapping evident in “YAH.,” that is, in clear relation to the beat if somewhat behind it. Other aspects of Lamar’s rhythm become more consistent here as well, especially his placement of accent. Figure 12.14 plots all 12 measures of the verse, but shows only the beat classes that receive accents in each measure. While the first four measures are chaotic, the last eight are highly patterned, projecting a kind of groove through accents on beat classes (2, 4, 7, 10, 12, 15).32 Figure 12.15 maps this groove onto the kick-and-snare pattern of the verse and documents Lamar’s complementarity with the instrumental streams. He answers the skewed “boom-bap” with his own patterned groove, while for the most part avoiding beat classes that the instrumental streams also avoid. Taken as a whole, these verses demonstrate the remarkable wealth of rhythmic approaches in the contemporary rapping voice, one that calls for scholarly emphasis beyond swing and phase relationships.

12.13 “ELEMENT.,” third verse, mm. 5–12. Compare to Figures 12.7 and 12.10.

12.14 “ELEMENT.,” entire third verse, metric position of accented syllables

12.15 “ELEMENT.,” third verse, mm. 5–12, rhythmic structure of kick, snare, and accented vocal syllables (top)

Conclusion

In this chapter I have selected two features of contemporary rap music that distinguish it from conventional approaches to rhythm in popular music – Kendrick Lamar’s use of varied backbeats at the meso-level and substantial phase non-alignment and speech-like rhythm at the micro-level. The differences between contemporary rap music and pop-rock music in these regards have their roots in differing technologies, communities, and life histories of contemporary rappers. Yet these distinctions, in my view, are not isolated or marginal. Instead, they have become central to the rhythmic organization of music that extends well beyond rap and hip-hop.

In their study of trajectories and life cycles of music genres, Jennifer Lena and Richard Peterson distinguish between genred and non-genred music; the former is associated with a community and initiated by a small clique of musicians unsatisfied with existing genres.33 Rock music and rap music are genres. Pop music is not: “At its core, pop music is music found in Billboard magazine’s Hot 100 Singles chart. … Artists making such music may think of their performances in terms of genre, but the organizations that assist them in reaching the chart most certainly do not.” Over the past several decades, scholarship on “pop-rock” has made profound contributions to music analysis, not only in the ways that repertoire is understood, but also in the methods analysts bring to the study of many other genres (including “classical” music). But Lena and Peterson’s framework suggests that these studies are not of “pop-rock,” but rather rock music, much of which was also, for a time, very popular. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the genres co-opted by the mainstream music industry as “pop music” have shifted decisively from rock music toward hip-hop and electronic dance music.34 It is therefore necessary to consider how the influence of these genres impacts the appropriate analytic methods for describing them. This reconsideration, in a sense, is a revival of the impetus for pop-rock scholarship beginning in the 1990s: to describe contemporary popular music on its own terms and see what that project can do for music analysis more generally. I can only hope it will be as fruitful.