Introduction

This chapter aims to present the history and the main features of operetta in Greece from the mid-nineteenth century until today. The introduction, dissemination and success of this musical genre, both in Greece and in Europe, is inherently connected to the development of an urban audience and the establishment of organized evening entertainment. Given that it is a genre cultivated exclusively in urban centres, its evolutionary path will be followed within the special historical and cultural framework of a new European state, which is recovering and struggling to reconnect with the Western world after 400 years of Ottoman occupation. As is the case with all related cultural phenomena in Greece, operetta too belongs to the area of the history of European theatre and European music; consequently, its trajectory in Greece needs first to be connected with the development of Greek urban life and the continuous trend for westernization and Europeanization characterizing nineteenth-century Greece. Secondly, in order to better approach the genre and follow its evolution, a brief sketch of its historical, social and cultural background is required.

Socio-historical Reality in Greece before the Appearance of Operetta

The Greek state was founded in 1830 and covered a very small territory at the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula. Its first period (1830–64), termed ‘Ottonian’ after the name of the first King of Greece, the Bavarian prince Otto, witnessed the foundation of the first state structures, originally in the city of Nauplion, and then in Athens, where the capital of the new state was subsequently transferred. During this period, the urban class was still unformed, and the dominant social group consists of Bavarian officials, rich expatriates, old landowners and military leaders of the successful revolution against the Ottoman Empire.

From the very first days of the establishment of modern Greece in 1830, catching up with lost time and getting into alignment with European cultural ways were tasks considered more than necessary. As a consequence, all eyes were turned to the West and a new, bourgeois lifestyle was adopted. Until the end of the century, rapid progress took place in Athens, the new capital of the independent Greek state, in the spread of western European habits, always within the general framework of conscious and hurried westernization.1

From the 1840s until the end of the 1860s, Italian opera reigned in the nightlife of the major Greek urban centres. Italian troupes established themselves in Athenian theatres, as well as in the tried and true ‘hotspots’ of the Ionian Islands, populated by Greeks but not yet annexed to the Greek state. These troupes received state funding on a regular basis and enjoyed a very wide audience. It is hard to imagine the impression of the first performances of European opera on ears accustomed, until then, only to monophonic Byzantine choral music, folk songs and oriental amane songs. Italian opera was even more scandalizing on a visual level, since it brought for the first time women performers on stage, and on a content level, with its focus on sensuality, erotic passion, romantic death and other extreme emotional situations.2

The second period (1865–1900), the reign of the next (this time Danish) king, George I, brought about major social reforms and a rapid urbanization of Greek society. The country’s borders expanded with the annexation of new lands (Ionian Islands, Thessaly, Epirus); the social make-up of the population changed with the incorporation of the extremely advanced Ionian society; and local cultural life knew a new development, thanks to the rise of native artistic creation, which included a large spectrum of musical and theatrical compositions, containing, as a high point, the operas by Ionian composers. Meanwhile, three booming trade centres, the city-ports of Piraeus, Patras and Hermoupolis in Syros brought an increase to the country’s urban population. This population was the audience which thronged the new theatres, built in Athens, the Ionian Islands and the three-above-mentioned new dynamic cultural markets.

In the same period, the total rule of Italian opera was threatened by the first French operetta and vaudeville companies who knocked hesitantly on the door of the Athens Winter Theatre in 1868, only to completely conquer, by the beginning of the next decade, the capital’s theatrical market and draw the immature nouveau-bourgeois society, including King George I, into a Bacchic trance in the rhythm of cordax, i.e., the cancan. Along with their intriguing repertoire, the French artists who arrived in the Greek capital brought with them outlandish theatrical morals, and therefore created a novel sensation in the Athenian audience – but also provoked a storm of reactions from the socially and aesthetically inexperienced Athenian public.3 Also in the same period, a new local genre of music theatre was born, termed ‘comic idyll’, while the distinction of cultural life between urban genres (opera, operetta, vaudeville, café chantant, variété, prose theatre) and folk/popular ones (open-air spectacles, shadow-theatre, café-aman) became stronger.

Already, by the start of the 1870s, the new king clearly showed his preference for la culture française. For the first time, sources of the period made mention of French comedies and vaudevilles performed in the palace. At the same time, the café chantant was promoted as the latest thing in bourgeois fashion. The first café chantant in the city opened in 1871, on the banks of the river Ilissos. It achieved success and deeply influenced the city’s theatre life, as it signalled the beginning of organized music entertainment in Athenian cafés and opened the way for the first Athenian open-air theatres.4 There, French and German beauties drove the audience crazy with their airs and graces, as well as with their light, coquettish and scandalizing repertoire.

The official advent of the operetta, with a royal seal to boot, must be placed in the autumn of the same year (1871). Since the summer, in view of the visit of King George’s Danish family in the coming October, the government and major private sponsors had been collaborating to collect sufficient funds in a hurry and had sent two Greek impresarios to Paris in order to form a French operetta group. As soon as the French company started to perform, staging La vie parisienne, ‘a drama of well-known plot and performance, serious, decent, educative on many levels, enforcing the most noble sentiments of human heart’,5 the first grumbles began against the ‘vaudevillian mania which had taken over our youth and part of our society’.6 Hervé’s, Lecocq’s and Offenbach’s operettas, along with naughty French vaudeville plays provoked virulent reactions of the conservative press, which railed against the indecent spectacles, the bedroom tales, infidelities and divorces, the frenzied dances and the scandalous verbal obscenities.

A major scandal was created by the two great hits of the Bouffes-Parisiens, Orphée aux enfers and La belle Hélène, which were viewed as tasteless parodies of antiquity. What primarily offended some of the Athenians of the 1870s was not the affront to propriety and to bourgeois morality. It was the blasphemy against classical antiquity, a taboo period for the Greeks of the nineteenth century, for whom the antique marble pillars were the main support of their newly built but still feeble national identity. Nevertheless, most of the art-loving Athenian public, irrespective of gender and age (including the high-born guests of the palace), instead of being revolted by the ‘moral poison of Greek civilization’, rushed to secure their theatre boxes in order to enjoy Zeus, dressed up as an insect, buzzing the ‘Fly Duet’ and the whole pantheon squealing in delirium during the ‘Gallop of Hell’.7

The triumphant course of French operetta continued over the next few years, spreading to the theatrical scenes of smaller cities, like those of Patras, Hermoupolis and Zakynthos. The most popular play by far was La fille de Madame Angot by Charles Lecocq. The popularity of the genre grew even more, when, in 1883, Armenian operetta troupes visited Athens to perform the oriental, Turkish-language operetta Leblebici Horhor Aga (Horhor Aga the Chickpea Seller) by Tigran Tsouhadjian, a play which caused a great impression on the Greek audience, thanks to ‘the great originality of its oriental characters’, and the ‘peculiar’ and ‘strange’ harmony of its music, which distantly evoked European melodies intermingled with ‘intoxicating and sensual oriental melodies’.8 In total, more than fifty French troupes visited Greece between 1872 and 1899, performing more than 300 different plays.9 The most important troupes are those of Lavergne, Alaïzat, Moreau and Lassalle-Charlet.10 French and Viennese operettas performed by foreign touring companies were all sung in their original languages; they were translated into Greek only when performed by Greek troupes.

The First Greek Operetta and Related Genres

The addiction to light musical theatre soon bore fruit, as a series of new musical theatrical genres were born out of this systematic contact during the period of the fin de siècle: singing comedy, comic idyll, revue and local Greek operetta. However, there is an early native genre which should be considered as a forerunner of Greek operetta: the Ionian comic idyll. It appeared as early as 1832 and constituted a mixed genre of Ionian musical singing comedy, mainly a comedy of manners, but occasionally also verging on political satire, which flourished in the islands of Cephallonia and Zakynthos. It is set to music often borrowed from well-known operatic melodies but may also include original pieces. Ionian comic idylls seem to have been performed throughout the nineteenth century both in Ionian theatres and as open-air spectacles, by amateur troupes.11

In any case, the Ionian tradition of the comic idyll lies at the root of the first conscious attempt to compose a Greek operetta, by the Zakynthian composer Paulos Carrer, and his compatriot idyll-writer Ioannis Tsakasianos. Carrer, was the most productive and most important Greek opera composer of the mid-nineteenth century and a sensitive receiver of new trends in the international field of musical theatre. He must have sensed the decline of Italian opera and the rise of French musical theatre on the Greek stage, and he was probably the first who felt the necessity to create a local operetta production. The thought of trying his hand at a new genre must have occurred to him around the end of the 1870s, when he had the opportunity to see French operetta close up. His first taste of it took place through Italian mediation, when, in 1879, he watched, at the Apollo Municipal Theatre of Patras, a performance of the popular La fille de Madame Angot by an Italian troupe in Italian translation. The ‘clandestine’, as it was termed due to its Italian guise, introduction of ‘this prancing and intoxicated genre was received with unadulterated and drunken enthusiasm’ by the public of Patras.12

His idea of a Greek operetta solidified when he met the naïve satire de moeurs rhymed plays, with a strong couleur locale, published from 1884 onwards by the Zakynthian poet Ioannis Tsakasianos, which featured the local character of Sparrow. The Sparrow poems of Tsakasianos, which represented everyday life in Zakynthos in vivid colours and with satiric intent, provided Carrer with the fitting subject matter for his first operetta, entitled Count Sparrow or, Swoons and tantrums, on which he worked for two years, from 1886 until 1888. Carrer’s words, when asking Tsakasianos to write him a libretto, in a letter dated July 1886 are characteristic: ‘I shall propose to you, if you are interested, to inaugurate with me the genre of Greek operetta – a kind of Madame Angot … Write for me a libretto for the Sparrow of Zakythos.’13

The action of the ‘one-act melodrama (operetta) in two parts’ takes place in Zakynthos. Its plot is more reminiscent of a comic idyll of manners than of a saucy operetta. It is the love story of two young people belonging to different social classes who eventually come together despite all those opposing their union. The libretto is mostly in rhymed verse, except for a few short dialogue sections in prose. The separate singing numbers, namely the arias, duets, ensembles and male and female choruses, are composed in simple metres and are full of repetitions of stanzas and refrains. Count Sparrow is divided in two parts and consists of twelve short scenes. Its language is vernacular, with several dialectal elements.

Having expressed doubts about the quality of the libretto, in terms of both structure and content, Carrer set the first act to music and planned the second and third acts but never completed his composition. The only surviving part of the play is one of the musical pieces, the duet of the young lovers Tonis and Marina, which was published in the illustrated magazine To Asty in December 1888 (Figure 11.1). Since then, the fortune of this one act of Count Sparrow set to music is unknown. The ‘first Greek operetta’ has been left, in Carrer’s own words ‘to sleep the big sleep in the library’. Let us hope that it will one day awaken, upon its discovery in some Ionian archive.14

Figure 11.1 The duet ‘My star-born love’ from the operetta Count Sparrow by Pavlos Carrer as published in To Asty, 18 December 1888

In any case, at the same time, during 1887–9, musical theatre – sometimes in the form of singing comedy, as in the caustic General Secretary by Elias Kapetanakis (1893), and sometimes in the form of comic idyll of manners (though not operetta), as in, for example, The Millers, of unknown authorship (1888), the Fortunes of Maroula by Demetrios Koromilas (1889) and The Solution of the Oriental Question by Demetrios Kokkos (1889) – underwent a period of triumphant success.15 These plays have Greek plots but follow the familiar recipe of rearranging the music of popular European tunes in combination with folk-music motifs, by composers such as the Bavarian Andrea Seiller. The comic idyll enjoyed a monopoly on Greek stage production for about twenty years and constituted the training ground for the cultivation of the two most popular genres of musical theatre in Greece, operetta and revue.

At this point, a passing mention should be made of a Greek composer of light musical theatre who achieved considerable success on the London stage during the fin de siècle. This is Corfiot Napoleon Lambelet, who, after a relatively successful career as a composer, conductor and music teacher in Athens and in Alexandria, emigrated to London in 1898 and met with resounding success on the British musical stage with plays such as Yashmak: A Story of the East (1897), The Transit of Venus (1898) and Valentine (1918).16

The Advent of the Twentieth Century

The first four decades of the twentieth century up to the outbreak of World War II are marked by two major movements: urbanization and emigration, especially towards the USA. The victorious Balkan wars, and World War I expanded Greek territory even more, and added new urban centres, namely the vigorous multi-cultural Thessaloniki, while the Goudi Coup strengthened a new social power, the working class. The Asia Minor disaster, and the integration of 1.5 million refugees from the cosmopolitan cities of the western Asia Minor coast (Ionia) in Greek society is the most important event of the period, and had a tremendous impact on Greek social structure.

The rich cultural harvest of this period includes Athenian revue and operetta, two musical theatre genres that enjoyed great fortune. This period also sees the cultivation, in many forms, of urban popular song, the expansion of which is linked to the development of the record industry and is connected to the dominance of musical theatre on the Greek stage. Finally, the social osmosis with the Asia Minor refugees, with their urban background and oriental music tradition redefined the dividing lines between Western and oriental and had a determining impact on artistic production and cultural life in Greece. As will be demonstrated later, operetta would function as a meeting point between the different aesthetic trends of the period.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the reigning queens of Athenian evening entertainment were operetta and revue. The high point of Athenian revue is to be placed in the period 1907–21, while operetta takes over from 1920 until the mid-1930s. The two genres share many common features but also present several differences. Revue has an episodic structure, with ‘numbered acts’, and aims to comment on and satirize current events,17 while operetta possesses a stronger dramatic unity and a more developed plot. Although revue may be considered more ‘popular’ and operetta more ‘urban’, they are in fact two communicating vessels, which allow the free movement of composers, orchestras, soloists, dancers, producers and troupe leaders from one to the other. In general, one may describe the evolution of light theatre in twentieth-century Greece as initially a transition from the comedy of manners to cosmopolitanism, and subsequently to popular entertainment. So, one may observe, during the first phase of evolution of the genre, from the beginnings to the 1920s, the protagonists of comic idyll abandoning their traditional folk costumes to adopt elegant Western attire and European dances in order to enter the salons of the European elite and the royal courts. The silly country girls with their naïve cunning transform into modern women who dance the Charleston at dancing clubs, flirt, smoke and vote.

The first decades can be considered as the Viennese phase of Greek operetta, which thrilled Athenian audiences and represented the ‘imperial dream’ of the inhabitants of a small country on the fringes of Europe. At the same time, Greek troupes attempted for the first time to stage European operettas, starting with Mlle Nitouche by Hervé, which was performed by the troupe of Antonis Nikas in 1908, with a thirty-member orchestra and the collaboration of well-known revue composer Theophrastos Sakellaridis, who was destined to become one of the most distinguished Greek operetta composers.18 Soon after, Evangelos Pantopoulos, a successful comic actor and troupe leader, well remembered by the Athenian public thanks to his smash-hit performance as a miller in love in the comic idyll of the same name (The Millers), contended for and earned the right to stage the first performance of The Merry Widow in 1909, while also staging a number of Greek operettas with a strong popular element, such as Pharaoh Pasha and his Harem by Dimitris Aravantinos (1906) and The Devils (1909).19 From 1908 onwards, several Greek operetta troupes were formed, competing with each other and with foreign troupes touring in Greece. Among the most memorable and active ones, one may mention the troupe ‘Operetta Papaioannou’, which toured in Greece and abroad for more than twenty years (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 A scene from the Greek version (entitled Gingolette) of the Viennese operetta Libellentanz by Franz Lehár printed on the cover of the musical score. This publication is related to the production by the celebrated troupe ‘Operetta Papaioannou’.

The first Greek operetta with pretensions of quality was staged in May 1909 by the Nikas troupe. It is entitled Land-ho or Thalatta, thalatta and was set to music by Theophrastos Sakellaridis, with a libretto by Stephanos Granitsas and Polybios Dimitrakopoulos. Thanks to its plot, which is set in the Greek Navy, the play has a strong sociopolitical message, as it expresses an indirect criticism of favouritism in the armed forces. This play caused displeasure to the authorities and was cancelled, only to be staged again in a censored version. But the first truly great hit was the operetta In the Barracks, performed on 9 May 1914, which crowned Theophrastos Sakellaridis as the king of operetta, a title that he would have to share, after a few years, with his colleague Nikos Hadjiapostolou. The play In the Barracks was directly linked to the political situation and the Greek victories in the Balkan wars, as well as to World War I. The plot (a young woman disguises herself as a soldier and enlists, so as to remain in the barracks in Athens, near her sweetheart) was the cause for both national and artistic enthusiasm.20

Two more operettas, written by the internationally acclaimed composer Spyros Samaras were connected to historical and political events of the period. The first, entitled The Princess of Sasson (1915) had to do with the small island of Sasson near Corfu, ceded by Albania to Greece in 1914, while the second, The Cretan Girl (1916), was connected to the foundation of the Cretan State and the Union of Crete with Greece in 1913. The works of Samaras combine European and Greek musical idioms and belong, in comparison to the other operettas of the time, to a higher artistic register.21

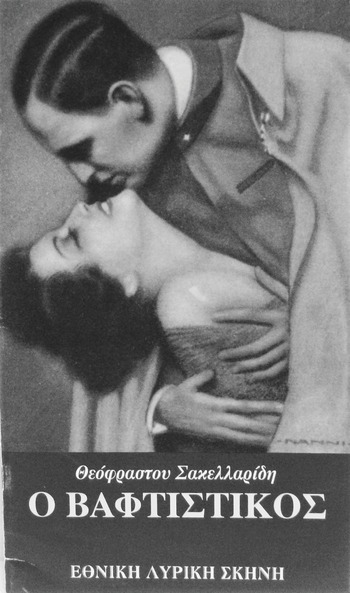

Just before the end of World War I, on 18 July 1918, one of the two most popular Greek operettas ever was staged: The Godson, by Theophrastos Sakellaridis (Figure 11.3). From its opening night, the play caused a sensation with its unconventional representation of military officers: one of the characters, a full colonel, flirted on stage wearing his military uniform. The play was censored by the authorities, the police intervened and the producers were forced to revise it by removing the offending passages.22 Its libretto was based on a French farce, but it was ‘immersed’ in Greek reality, and was characterized by clever dialogues, memorable lines, hilarious characters, catchy music and an indomitable national spirit. Thanks to these qualities, the Godson remains until today the most-performed Greek operetta.23

This first phase of evolution ended with the mass production of plays and performances of Greek operetta during the interwar period. Within the atmosphere of European belle-époque euphoria, insouciance and wild revelry between the two wars, operetta in Greece now experienced the zenith of its popularity, while original Greek operetta plays dominated the stage and public taste. Fermented by the political events of the two wars, which had taken place in the previous period, the comedy of manners made a comeback, now in the guise of urban working-class culture of the big cities. The popular element was now prominent in the plays, interlaced (often literally, since many plays end in a cross-class marriage) with the world of the bourgeoisie and the upper classes.

The most representative play of the period is undoubtedly The Apaches of Athens by Nikos Hadjiapostolou, performed at the Alhambra Theatre on 19 August 1921. Boasting ‘one hundred and fifty nights in a row’ of continuous performance and almost mythical box-office turnout, it achieved the greatest theatrical success of the interwar period and caused the envy of all theatre producers in Greece, who vainly tried to repeat its magic recipe.24 What was the secret of such success? Probably the appearance on the urban operetta stage of a company of original, true-to-life, low-class characters of Athens: the Prince, Karoumbas and Karkaletsos. With their direct, unpretentious idiomatic language, their unaffected behaviour, their sterling character, their code of honour and their true feelings, which the nouveau riche and the high-society people lack, the play’s heroes, namely the low-class streetwise toughs, the urchins, the spivs, the princes of the street, speak to the heart of the people and bring the operetta genre closer to the masses. The simplistic dual schema of the Apaches’ ‘honest poverty–dishonest wealth’ revitalized the genre and the composer reached the top.25

It is not easy to calculate the number of plays written and performed during this period in Athens and Thessaloniki, nor the number of active troupes. It is equally difficult to categorize most of the plays as operettas or revues. There is even a new hybrid genre, the operetta-revue, which incorporates the element of critique of current affairs. But an estimation of about a thousand new original works, performances and troupes is not far from reality: a veritable operetta mania. Apart from the unbeatable duo of Sakellaridis and Hadjiapostolou, other successful creators include Giannis Konstantinidis/Kostas Giannidis – a composer who signed his work using two different pen names and two personalities, one for art music and one for light music – with the cabaret-operetta Der Liebesbazillus (Berlin, 1927);26 Stathis Mastoras, later destined to become a martyr of the nation, with Our Girl Ririka (1934); and a number of women composers, such as Eleni Lambiri and Carolina Mastrakini.

Even major historical events such as the Asia Minor disaster did not put a stop to the rise of the operetta, which continued to dominate the stage, with expensive productions generously offering an escape from sordid reality. At the end of the decade, the economic crisis of 1929 and the American market crash would turn the public’s interest towards the USA and towards the American cinema musical, which breathed new life into the operetta genre. The success story of Greek light musical theatre was interrupted only by the establishment of the junta regime of 4 August 1936, which inaugurated a period of political intervention and persecution. Many artists sought to escape to theatrical stages abroad, in diaspora cities like Constantinople or Alexandria.

The foundation of the National Opera (1939) marked the return of Athens to the tradition of Viennese operetta, which was unanimously viewed by the critics of the period as too heavy and outdated. Die Fledermaus by Strauss, which inaugurated the first artistic period of the new organization (5 March 1940) was perhaps the only foreign play by a Greek troupe during the interwar period. With the declaration of war just a few months later (28 October 1940), the genre seemed to disappear entirely, with wartime revue taking over. Until the end of the twentieth century, the National Opera cultivated operetta, not by producing new plays but by repeating old successes of the French and the Viennese school, as well the two greatest Greek operetta hits, The Godson and The Apaches of Athens, which was also translated as The Gays of Athens.27

Apart from revue, which maintained a dynamic presence on the Greek stage, the audience’s need for musical theatrical entertainment is thereafter covered by the cinema of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. This includes the filming of operetta performances and the cinema adaptation of well-known operettas, but also a new genre, the Greek cinema musical, which captured the audience thanks to the fresh faces of a host of young actors, its colourful sets dominated by the Aegean Islands and the ‘bouzoukia’ stages; its flashy costumes with sequins, feathers, tulles and very little fabric indeed; its daring choreography; the slender bodies of its female protagonists and the remarkable voice and brio of the ex-operetta singer Rena Vlachopoulou.28 In the next decades, operettas were only very rarely staged by mainstream commercial troupes and protagonists; a notable exception was The Merry Widow, starring the ‘national star’ Aliki Vougiouklaki in 1980, and its TV serialization in 1991.29

The Cultural Contribution of Operetta

The above historical overview aimed to show that operetta was a genre which brought with it a renovation of the Modern Greek theatrical stage and life, invigorating it with a new repertoire and forming a new theatrical tradition. The key features of operetta, such as its directness, familiarity, easily consumed and memorable lines, rendered it almost addictive for more than forty years. In an attempt to discuss more deeply its meaning and contribution to Greek culture, one comes up against a multiform core consisting of a series of binary oppositions.

East and West

The new original operetta creations provided the frame for Greece’s twofold cultural identity: Western and oriental. Although the incorporation of the oriental and the exotic element in Greek music and Greek lyric theatre dates to the second half of the nineteenth century, with works such as the opera Frossini by Pavlos Carrer (1868) and the great favourite of Armenian origin, Horhor Aga, this tendency runs strong in the Greek operetta production of the 1920s. Works like Halima by Theophrastos Sakellaridis (1926) are based on the rearrangement of Western music in a minor key and with oriental tunes. The contact with melodies from Asia Minor and Smyrna via the refugees from Asia Minor enhances this aesthetic, which takes the form of an idealized oriental romanticism.

Art and Pop

At the same time, operetta succeeded in functioning as a social melting pot between ‘high’ and ‘popular’ musical creation. It was the source of a great number of very widely known songs which were sung for decades as bourgeois and popular hits. So, the Greek repertoire includes works with varying degrees of art-type or pop-like music. There are waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, csárdás, jazz, music-hall hits, Latin songs, Italian cantatas, pop songs, folk dances, even oriental music and rembetika songs … Theophrastos Sakellaridis admitted that he kept ‘musical stenographic minutes’ of any melody he heard, so that he might later adapt it in his compositions, and included as his sources of inspiration even tarantella, café chantant music and tunes from the Gipsy encampments and the open-air popular spectacles performed in the western fringes of the capital. Many composers, librettists and soloists deserve the characterization of ‘Janus’, as they follow careers both in the ‘high/art’ and in the ‘low/light’ or even the ‘popular’ repertory.

Up and Down

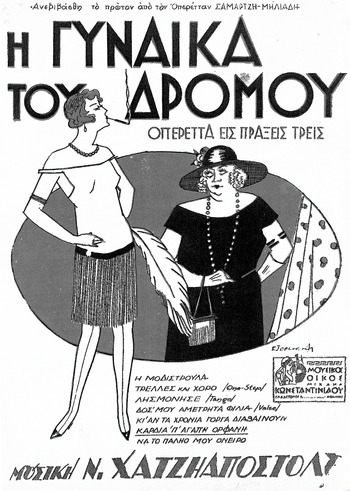

Cross-class marriages, popular elements, low-class characters and apaches abound in Greek operetta. The satire against nouveau-riche attitudes, xenomania, and the fake aristocratic manners of the Athenians, is very strong. The stereotypical bipolar antithesis ‘rich and poor’ has an added dimension of ‘modernity vs Greekness’. So, comedy of manners and cosmopolitanism are merged in one and the same performance, satisfying the tastes of all audiences. The moral-didactic element is also frequent: the girl that has gone astray, the honour of the poor but virtuous girl vs the corrupted nouveau-riche women of the urban classes. The emblematic play of this tendency, The Apaches of Athens (1921), brings with it an air of subversion: it is no longer the bourgeois characters who dominate the plot but three low-class characters, something which would be inconceivable in European operetta. The Greek operetta milieu includes not only upper-class salons but also night-clubs and cabarets of ill-repute, lowly front yards of poor people’s houses and servants’ quarters. It also sets on stage ‘common’ women with a sinful past and a golden heart, like the heroines of The Girl of the Neighbourhood (1922) or The Woman of the Streets (1923) by Hadjiapostolou (see Figure 11.4), or the public’s favourite, the night-dancer Plou-Plou or Blou-Blou, who appeared in several plays, such as The Daughter of the Storm and Christina (1928) by Sakellaridis and Blou-Blou (1933) by Hadjiapostolou.

Figure 11.4 The cover of the musical score of the Greek operetta The Woman of the Streets by Nikos Hadjiapostolou

Modern Tunes and Dances

Another important aspect of Greek operetta was its contribution as an incentive for the development of the art of dancing, especially modern dance, in Greece. New rhythms were imported from America and Europe, such as the one-step, foxtrot, shimmy, Charleston and black-bottom. Dancing masters from abroad were employed to provide teaching for the supporting dance acts. The operetta and revue led to the establishment in Greece of the new profession of choreographer, whose first representative in Greek light theatre was the German Elsa Enkel.30 Young Greek artists chose to study in western Europe in order to specialize in the art of dancing; among them were Paraskevas Oikonomou and Angelos Grimanis, who soon took over as choreographers from their European colleagues. In the 1930s new dances were added to the operetta repertoire, such as the Argentinian tango and Cuban rumba.

Lifestyle

The enormous artistic production of the interwar period popularized not only songs but a whole aesthetic and more: dances, dress codes, manners, lifestyle. A strong asset of operetta, from its first appearance, was its patently European air, with its opulent costumes and spectacular sets, exactly like those of the theatres abroad. Operetta was the means of informing the public concerning new dance trends, light music-hall music, clubs and dancing, fashion and European or American lifestyle in general. At the same time, the cinema exercised a strong influence: sometimes operetta performances were filmed and watched as cinema spectacles, and sometimes films included full orchestras (the so-called filmoperettas), while frequently the plots of Hollywood films were adapted as operettas. In any case, the cinema effected an approach between operetta and the American musical.31

Actοrs and Singers

Operetta was the formative ground for a number of major actors who made a name for themselves not only in the field of musical theatre but also in the new artistic field of cinema. The protagonists of Greek operetta were mostly self-taught actors of comic idyll or agile actors of prose theatre with good voices; real classical soloists who had engaged in musical studies were rare. Among the biggest names, one should mention Rosalia Nika, Melpomeni Kolyva (Figure 11.5), Yiannis Papaioannou, Elsa Enkel, Soso Kandyli, Aphrodite Laoutari and Yiorgos Dramalis. Later, operetta and revue protagonists found their way into the cinema, as was the case with Rena Vlachopoulou, Zozo Sapountzaki and Sperantza Vrana among others.

Figure 11.5 The operetta protagonist Melpomeni Kolyva, c.1910.

Sociopolitical Messages

On a different note, Greek operetta proved itself several times as the carrier of forceful sociopolitical messages, especially during periods of political tension (World Wars I and II, the Goudi coup, the Asia Minor Disaster). Many plays made reference to contemporary political realities. The composers presented an idealized view of war and especially the bravery and military exploits of the Greek army as an achievement of the lower classes, while the representatives of the upper classes were invariably represented as namby-pamby and effeminate, devoid of any trace of dignity or national pride, only concerned with purchasing an exemption from military service.

Finally, Greek operetta production numbers a long list of original stage creations, some of which are still quite popular. The two composers who stood out among the rest thanks to the quality and the popularity of their works, Theophrastos Sakellaridis and Nikos Hadjiapostolou, still retain the leading role in the Greek scene of the twenty-first century. These are two very prolific composers, who produced about two original operettas per year, from the mid-1910s until World War II. Sakellaridis, especially, was an extremely versatile composer who wrote music for operas, operettas, revues and for the cinema. Even important composers of art music, such as Pavlos Carrer, Spyros Samaras, Dionysios Lavrangas and Napoleon Lambelet fell victim to the charm and direct appeal of operetta and composed original operetta works. It is obvious that the enormous productivity and commercial success of the operetta in the interwar years was not a short pyrotechnic boom but the result of a long tradition in lyrical and light musical theatre in Greece.

To conclude, operetta underwent many transitional phases throughout its century-long history in Greece (from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century) until it gained the leading role in Greek theatre and the preference of the Greek public. It initially stormed in with French verve and coyness; it then acquired a veneer of Viennese grace and superficiality, until it was eventually Hellenized, claiming its right to both urban and popular form and to the double aesthetic character of its new homeland, and ended up becoming the quintessence of urban evening entertainment, extravaganza, sophistication and fashion. Later, the devastating events of the mid-twentieth century, namely the outbreak of World War II, and the dark years of the German Occupation and of the Civil War, led to its decline. During the second half of the twentieth century, operetta was in effect a period genre, considered old-fashioned and rather quaint, almost completely overshadowed by theatrical and cinema musicals. However, from 2000 onwards, there developed a tendency for rediscovering forgotten plays and performing them anew, with modern directors and contemporary staging. At the same time, tribute performances are staged, such as the nostalgic compilation Remember Those Years (2007–8),32 inaugurating a new phase of revival of Greek operetta, warmly embraced by the public and even younger audiences.