George Edwardes, one of the most influential theatrical entrepreneurs in the decades before and after the turn of the twentieth century, twice detected a change of taste in the public’s appetite for the musical stage. In the 1890s, he had noted a decline in enthusiasm for the type of comic opera associated with Gilbert and Sullivan. It was then that he commissioned and encouraged a fresh type of stage entertainment, which he called ‘musical comedy’.1 In the early twentieth century, he sensed another change in mood and took a chance with The Merry Widow, a modern operetta from Vienna that has come to be regarded as the foundation stone of the silver age of continental European operetta.

The musical comedies produced by Edwardes were in competition not only with the burlesques popular at the Gaiety Theatre, such as Faust Up to Date, but also with comic operas at the Savoy Theatre. This explains why a mixture of styles from the operatic to music hall is found in musical comedies, especially in early examples such as In Town (book and lyrics by Adrian Ross and James Tanner, music by F. Osmond Carr) and A Gaiety Girl (book and lyrics by Owen Hall, music by Sidney Jones). Gilbert and Sullivan’s Utopia Limited opened at the Savoy the week before A Gaiety Girl in October 1893, following in the wake of successful runs at that theatre for Edward Solomon’s The Nautch Girl (1891–2), and Sullivan and Sydney Grundy’s Haddon Hall (1892–3). Edwardes’s initial experiments with musical comedy took place at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre, which had been home to a successful run of Alfred Cellier’s Dorothy, an operetta that had had a disappointing premiere at the Gaiety in 1886, when Edwardes first took over management of that theatre. It had been a premature attempt by Edwardes to change the Gaiety audience’s expectations.

In 1894, he had acquired sufficient confidence to produce The Shop Girl at the Gaiety Theatre, perhaps because In Town had transferred successfully there the year before. The book was by H. J. W. Dam, who claimed to have researched his subject in Whiteley’s department store and the Army and Navy stores in order to capture ‘the life of today’.2 The music was by Ivan Caryll, with additional numbers by Lionel Monckton to lyrics by Adrian Ross. Caryll was born Félix Tilkin in Belgium and had studied at the Paris Conservatoire. Monckton’s training was rather different; while a law student at the University of Oxford, he had acquired experience composing music for the university’s dramatic society. The Shop Girl was a great success, running to 546 performances, and it established musical comedy as the most popular stage entertainment in the West End. ‘Her Golden Hair Was Hanging Down Her Back’, a risqué interpolated song by music-hall artist Felix McGlennon, became immensely popular. The variety elements present in musical comedy meant that a song reminiscent of the style of the music hall or American vaudeville did not jar as it would have done in a stage work more closely associated with comic opera or operetta.

The description ‘musical play’ was used for the first time in advertising The Geisha (Owen Hall and Sidney Jones) at Daly’s Theatre in 1896. This label became common as a synonym for ‘operetta’ in the next decade and beyond. In a musical play, romance took precedence over comedy, and a higher standard of singing was expected. A lot of performers in musical comedy were actor-singers with little or no operatic vocal training or experience. The lead singers in The Geisha were Marie Tempest and Hayden Coffin, who were both up to the demands of its lyrical score. To a certain extent the interest in Japanese culture in this piece was genuine: Edwardes hired Arthur Diósy, the founder of London’s Japanese Society, as a consultant,3 and the choreographer was at pains to study dances at the Japanese exhibition village in London.4 However, a British imperialist commitment to modernity and progress is present, for, even as it served up escapism and romance, it did so by means of the latest stage technology.

Sidney Jones made his international reputation with The Geisha. Statistics for numbers of performances on the German stage show that, of works composed between 1855 and 1900, it was second only to Die Fledermaus in popularity during the first two decades of the twentieth century.5 It also enjoyed great success in France and the USA, and throughout the British Empire. Perhaps more unexpectedly, it was a hit in South America, Italy, Russia, Scandinavia and Spain.6 Its character illustrates some of the typical differences between earlier operetta and musical comedy. Unlike The Mikado (1885), the foreign in The Geisha is a source of entertainment, rather than an allegoric means by which members of the audience recognize their own follies and prejudices. The satire of sentimentality is also more crudely handled in the song ‘The Amorous Goldfish’ from The Geisha, than in ‘Tit-Willow’ from The Mikado.

Another enormously successful show was Jones’s San Toy (book by Edward Morton, lyrics by Adrian Ross and Harry Greenbank). It opened at Daly’s in 1899, running for 768 performances, just ten short of the number The Merry Widow was to achieve there between 1907 and 1909. In San Toy, Jones exchanged Japanese exoticism for Chinese. Two years later, Howard Talbot, who was born in New York but had moved to London as a child, mined Chinese exoticism to even greater commercial success in A Chinese Honeymoon, the first musical stage work to exceed 1,000 performances. It was at the Strand Theatre from early October 1901 until the middle of May 1904. At the Casino Theatre in New York, where it was produced in 1902, it ran to 364 performances, a number denoting an incontrovertible hit in that city. It was advertised as a musical play, but David Ewen calls it ‘more of a vaudeville show than an operetta’.7 That may be because it relied strongly on spectacle or because of songs such as ‘Martha Spanks the Grand Pianner’.

The choice of the label ‘musical play’, ‘musical comedy’ or ‘operetta’, is often motivated by marketing decisions, but there is a general expectation that a theatre work described as an operetta will contain more than tuneful songs and that ensembles and concerted finales will engage with the dramatic action so as to create an integrated musical stage work. The presence of such features makes it easy to categorize Ivan Caryll’s The Duchess of Dantzic (1903) as an operetta. Caryll returned to musical comedy, however, and, after moving to New York, was to take pleasure at the sight of audiences flocking to see the Broadway production of his The Pink Lady in 1911.

A Chinese Honeymoon was one of the prolonged theatrical successes of turn-of-the-century London that did not spring from the Edwardes stable. Two others were Gustave Kerker’s American operetta The Belle of New York (1897), produced in London in 1898, and Leslie Stuart’s Florodora (1899). In a rare error of judgement, Edwardes had turned down the opportunity to buy the rights to Kerker’s operetta at a cheap price after it managed only sixty-four performances at New York’s Casino Theatre.8 Unexpectedly, it ran for 693 performances at the Shaftesbury Theatre. Stuart’s Florodora was an enormous hit on Broadway in 1900 and spent eight years on the road touring American cities.9 The opening words of the sextet, ‘Tell me, pretty maiden, are there any more at home like you?’, are still widely known, even if the tune is only vaguely remembered. The song ‘The Shade of the Palm’, which begins with the words ‘Oh My Dolores, Queen of the Eastern Sea’, is referenced in the Sirens chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Three songs in Florodora were by Paul Rubens, who was to enjoy considerable success with Miss Hook of Holland in London in 1907 (it was also produced in New York that year).

The appetite for musical comedy in the West End of the 1890s and 1900s made Edward German’s operettas seem outdated in style. The reasons for this are not difficult to find and may be put down to his concern for moral and musical propriety.10 In terms of content, this translates as an eradication of anything too saucy in the book or lyrics and an avoidance of music-hall idioms in the music. Musical comedies were less inhibited about occasional lapses into vulgarity if the strength of the comedy provided justification. German was given the task of completing the unfinished score of Sullivan’s The Emerald Isle, which was performed at the Savoy Theatre in the spring of 1901 and had a respectable run of 195 performances. Basil Hood had written the libretto of The Emerald Isle, a mythical historical romance set in Ireland, and he also provided the libretto for German’s operetta of the following year, Merrie England. It was another historical romance, this time set in the Elizabethan period. Its run of 119 performances at the Savoy was enough to bring the composer to public attention, and it became popular with amateur operatic societies. Indeed, it was assumed by some that Sullivan’s mantle had fallen on German’s shoulders.11 In 1946, it was produced at the Princes Theatre, London, with a revised libretto by Edward Knoblock, and enjoyed a highly successful run of 367 performances.

German had slightly less success with A Princess of Kensington (1903) and Tom Jones (1907), but both had more than 100 performances. At this time, musical comedy was still going strong, and, in 1907, Tom Jones had to compete not only with the likes of Miss Hook of Holland and Caryll and Monckton’s The Girls of Gothenburg but also with Lehár’s The Merry Widow. In 1909, German’s musical version of W. S. Gilbert’s play The Wicked World (1873) was given as Fallen Fairies at the Savoy but proved something of disappointment, closing after fifty performances. Liza Lehman worked with musical comedy librettist Owen Hall (real name, Jimmy Davis) on her operetta Sergeant Brue (lyrics by J. Hickory Wood), which met with considerable success at the Strand Theatre in 1904. In fact, it transferred from there to the Prince of Wales Theatre and back again as it progressed to an unanticipated run of 243 performances.

It was common for musical comedy to involve composer collaborations, and Lionel Monckton and Howard Talbot created together one of the most enduring musical comedies in The Arcadians (1909), which had a book by Mark Ambient and Alexander Thompson, and lyrics by Arthur Wimperis. Monckton and Talbot composed musical numbers separately, although the latter was probably responsible for all of the orchestration. The West End production was by actor-manager Robert Courtneidge, and on Broadway it was presented by Charles Frohman. It was Monckton and Talbot’s finest joint achievement, praised by critics and public alike, and became one of the few works of this period to be revived with any regularity in the second half of the century. It is by no means easy in this instance to decide whether the category of ‘musical comedy’ or ‘operetta’ suits it best.

Among other triumphs for Monckton were A Country Girl, composed with Rubens (1902), and The Quaker Girl (1910). They both make much of the friction between the country and town (London in the former and Paris in the latter). Our Miss Gibbs, composed with Caryll (1909), is somewhat different, because its department-store heroine hails from Yorkshire’s largest city, Leeds. The title character, who was played by Yorkshire-born Gertie Millar, has a no-nonsense attitude in contrast to the sophisticated Londoner, and that is particularly evident when she sings her song ‘In Yorkshire’, for which Monckton supplied the lyrics and Caryll composed the music.

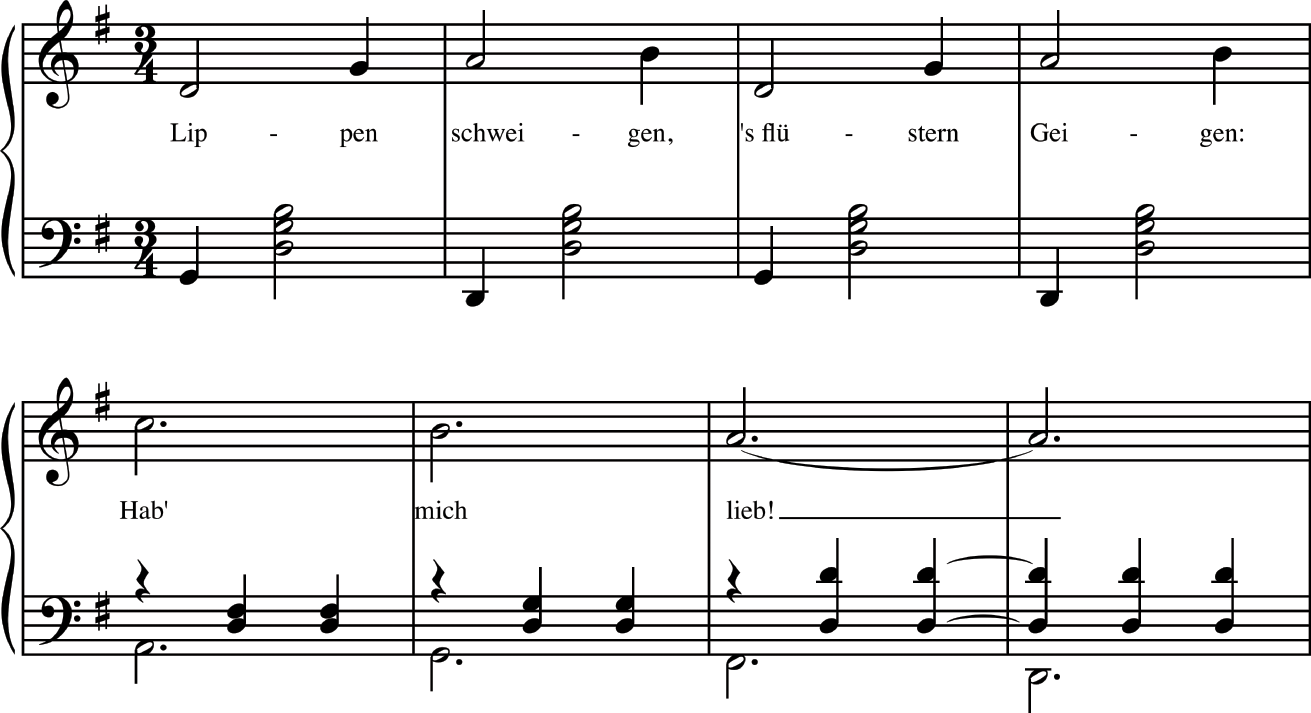

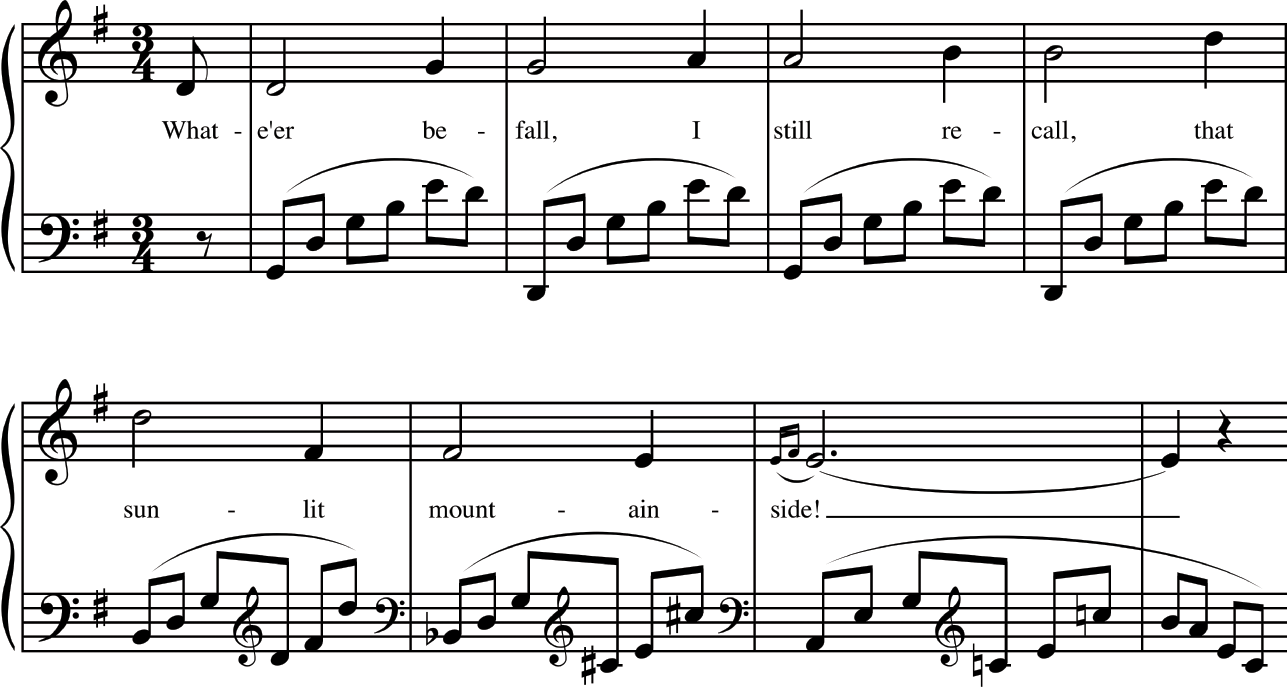

Just before World War I, operetta began to face a challenge from revue, which made use of a general theme to give loose cohesion to a varied bill of comic sketches, songs and dances. It was growing increasingly popular after Hullo, Ragtime (1912) and Hullo, Tango (1913). The most celebrated of the wartime revues in London was The Bing Boys Are Here with music by American composer Nat D. Ayer (1916). Operetta productions declined because so many necessitated the purchase of English rights from theatrical agents in Berlin, but there were two operetta-like entertainments that broke box-office records: Chu Chin Chow (book and lyrics by Oscar Asche, music by Frederick Norton), which opened at His Majesty’s in 1916 and ran for 2,238 performances, and The Maid of the Mountains (book by Frederick Lonsdale, lyrics by Harry Graham and music by Harold Fraser-Simson), which opened at Daly’s in 1917 and ran for 1353 performances. Both were examples of theatrical escapism, the first to a fantasy Orient and the second to the mountains of Italy. José Collins became forever associated with Teresa, the title role of The Maid of the Mountains. Her singing ability was an advantage in music that had, in places, clearly been influenced by the operettas from the German stage heard in the previous decade. Compare the melody of ‘Love Will Find a Way’ with the famous waltz from The Merry Widow (Examples 16.1 and 16.2).

Example 16.1 ‘Lippen schweigen’ from Die lustige Witwe

Example 16.2 ‘Love Will Find a Way’ from The Maid of the Mountains

Collins’s success as Teresa meant she became a highly paid star, and in 1920, when she undertook the role of Dolores in Fraser-Simson’s A Southern Maid, her salary rose from £50 to £300 a week (an equivalent of around £11,840 in 2018).12

In the 1920s, operettas such as Montague Phillips’s The Rebel Maid (1921), with its much-loved song ‘The Fishermen of England’, and Fraser-Simson’s The Street Singer (1924) held the stage.13 There is a tendency, however, to see the twin triumphs in 1925 of Vincent Youmans’s No, No, Nanette at the Palace Theatre, and Rudolf Friml’s Rose-Marie at Drury Lane, as marking the beginning of Broadway conquering all. In fact, Thomas Dunhill, Walter Leigh and Alfred Reynolds each composed a well-received operetta in the early 1930s (Tantivy Towers, The Pride of the Regiment and Derby Day, respectively).

Noël Coward, who had already built a reputation in revue, established himself as a British operetta composer when Charles B. Cochran presented Bitter Sweet to huge success at His Majesty’s Theatre in 1929, with American Peggy Wood making her London debut as Sari Linden. The orchestration of Coward’s operetta was by J. A. de Orellana, an experienced West End musical director who had obliged in a similar capacity for Monckton and Rubens.14 Bitter Sweet began playing simultaneously in New York from November, and films were made of the operetta in 1933 and 1940. Conversation Piece followed at His Majesty’s in 1934 (and also in New York that year). It was set in nineteenth-century Brighton and raised issues of social class. It starred Yvonne Printemps as Melanie, and her hit song was ‘I’ll Follow My Secret Heart’. In Operette, which opened at His Majesty’s in 1938, Coward created a role for Fritzi Massary, one of the most famous stars of the German musical stage, who, being Jewish, had fled to London to avoid Nazi persecution. Its best-known song is ‘The Stately Homes of England’. Coward continued to be productive: his musical romance Pacific 1860 was given at Drury Lane in 1946, and his musical play After the Ball (based on Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan) opened at the Globe in 1954.

Mark Steyn names Noël Coward as ‘the most famous British theatrical composer in America’ before Andrew Lloyd Webber arrived on the scene.15 However, it was the Welsh composer Ivor Novello who did most to keep English operetta alive in the late 1930s and the decade after. He was born in Cardiff in 1898 as David Ivor Davies and changed his name to Ivor Novello, using the middle name of his mother (who had been named after the celebrated soprano Clara Novello). His mother was a highly regarded singing teacher, and George Edwardes often sent performers to be coached by her at the Salle Erard during her visits to London. Novello began writing songs while a scholar and choir boy at Magdalen College School, Oxford.16 He developed a love of opera and theatre during visits to London as a young man and, in 1913, moved into an apartment rented by his mother at the top of the Strand Theatre in the Aldwych. It was to be his London home for the rest of his life.17

In 1914, he achieved fame as the composer of ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’, to lyrics by Lena Guilbert Ford, and his first commissioned musical play was Theodore and Co., given at the Gaiety in 1916, with additional music by Jerome Kern. In 1921, he composed a hit comic song, ‘And Her Mother Came Too’ (lyrics by Dion Titheradge) for the revue A to Z. In this song, the restaurant that once functioned as an escape for Danilo in The Merry Widow no longer offers any refuge for the vexed lover.

Novello became a silent film actor. He was asked by the renowned American film director D. W. Griffith to appear in The White Rose (1923) and was chosen by Alfred Hitchcock to star in The Lodger (1926).18 He was also an actor in, and writer of, spoken drama. Lily Elsie, the star of The Merry Widow whom he adored,19 performed with him in his play The Truth Game (1928) at the Globe, one of several dramas he authored. When, in 1934, The Three Sisters was a surprise flop at Drury Lane, despite lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein and music by Jerome Kern, it opened up an opportunity for Novello. He had not composed a musical score for several years, having been occupied with films and plays. Now, he embarked on Glamorous Night, the first of his works that can be called an operetta. He wrote the leading female role for the versatile American star Mary Ellis, who had played the title role of Rose-Marie on Broadway, but who now lived in London with her English husband. He asked Christopher Hassall to write the lyrics, and it was the beginning of a long-term partnership. To direct the operetta, he chose Viennese producer Leontine Sagan, who had worked for the acclaimed Austrian theatre director Max Reinhardt. Despite the hot summer of 1935, Glamorous Night attracted large audiences and did much to restore Drury Lane’s status as a premier theatre for operettas and musical plays. The plot had a sad ending, however, and so did the production. The manager had booked performers for a Christmas pantomime well in advance, and the operetta had to be terminated to make way for it.

At £25,000, the production expenses of Glamorous Night were large, and the running costs meant only a small profit was made, even though it ran for 243 performances.20 This may explain why the board of Drury Lane rejected Novello’s next operetta Careless Rapture. Drury Lane has a large stage and, in keeping with the audience’s appetite for spectacle, Glamorous Night had an expensive scene in which an ocean liner sank; ominously, the new work contained an earthquake. Novello was catering to the audience’s appetite for romance and spectacle, but the last stage earthquake was in Monckton and Talbot’s The Mousmé at the Shaftesbury in 1911, and that production made a loss of £20,000.21

The pieces chosen instead of Careless Rapture turned out to be disappointments, and this put Novello in a position to dictate his own terms: he was prepared to finance 75 per cent of the costs of production if Drury Lane would cover the remaining 25 per cent. The consequence was that he was now working as composer, writer, actor and manager. It seemed he could do anything except sing, this ability having deserted him in his sixteenth year.22 He circumvented the problem by playing roles in which he accompanied another singer at the piano. Careless Rapture was a huge success, and the board offered no objection to housing the next Novello operetta, Crest of the Wave, even if they noticed it, too, was strong on spectacle and included a train crash.

With a run of 205 performances, Crest of the Wave fell into the category of success, but not at the magnitude hoped for. That was to be achieved, after a bumpy start, with the next offering by Novello and Hassall, The Dancing Years. It opened in March 1939, but all London theatres were ordered to close on 3 September, the day the British and French declared war on Germany. A decision was taken to produce it again in March 1942 at the Adelphi Theatre, and it became the surprise hit of the war years, running there until July 1944. By then it had notched up a total of 1,158 performances.

Arc de Triomphe of 1943 was intended to be more operatic in character, and, indeed, contained within it a one-act operetta, Joan of Arc. It was produced at the Phoenix Theatre, running for 222 performances. Novello could play no part in it, because he was appearing in The Dancing Years. As it happened, he had to quit his role in the latter for other reasons. He was found guilty of a breach of the wartime regulations governing the use of petrol and private cars and was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. The case was complex, and his term was reduced on appeal to one month.23 Novello’s successes continued unabated after the war: Perchance to Dream, which opened at the London Hippodrome in 1945, ran for over a thousand performances, and King’s Rhapsody of 1949 notched up 842 performances.

Novello commented on the difference between his working methods and those of Coward: ‘even his lightest comedies have been written with most meticulous care … I work the other way. If a thing does not come out at once, quite spontaneously, I scrap it.’24 Yet, Coward, like Novello, could work at speed: despite having other obligations, writing and composing the whole of Bitter Sweet took him around six months, and, in his first autobiography, he tells of composing its hit song ‘I’ll See You Again’ in a taxi during a twenty-minute traffic jam.25 He and Novello had much else in common: they were both actor-managers, playwrights, author-composers and both gay. There was gossip in the theatre world about Novello’s sexual orientation, but his relationships with men seem to have had no negative effects career-wise, save for a suspicion that his harsh sentence for breach of traffic regulations may have owed something to a judge who had a ‘marked dislike for the acting profession and for gay men in particular’.26 Novello had many male friends and in their company was relaxed enough to refer to The Dancing Years as The Prancing Queers.27 His affectionate partnership with Hassall continued after the latter’s marriage.28 Hassall supplied the lyrics to every Novello operetta from Glamorous Night on, with two exceptions. One was Perchance to Dream, which has lyrics by Novello himself, because Hassall was serving in the army at that time. The other was Novello’s final stage work, Gay’s the Word, which had lyrics by Alan Melville. It starred Cicely Courtneidge as Gay, an ex-stage performer who had set up a drama school. It opened on 16 February 1951 and was described as ‘quintessentially English’ by the New Statesman.29 Gay’s the Word burlesques his earlier work in places, taking a shot at his Ruritanian operettas Glamorous Night and King’s Rhapsody.30

Ruritania in Glamorous Night is Krasnia, and in King’s Rhapsody it is Murania. Frederick Lonsdale had popularized Ruritanian settings in his librettos for King of Cadonia of 1908 (lyrics by Adrian Ross, music by Sidney Jones), and The Balkan Princess of 1910 (lyrics by Arthur Wimperis, music by Paul Rubens). Novello admitted to Lonsdale that the Ruritanian exoticism of the former had influenced King’s Rhapsody.31 Old-fashioned as such settings now were, the press coverage of the premiere indicated a widespread conviction that Novello had challenged the dominance of the American musical in London.32 On 6 March 1951, however, aged fifty-eight, Novello suffered a fatal heart attack, a few hours after he had been performing in King’s Rhapsody at the Palace Theatre.

Statistics showing performance runs, outstanding as they often are, cannot be regarded as a reliable gauge of Novello’s success. The Dancing Years, for example, came to a premature end twice because of bombing raids, and he took off Perchance to Dream while it was still filling the theatre, simply because he had other plans to fulfil. In the case of his Drury Lane operettas, it must be borne in mind that this theatre was twice the size of many other West End theatres. Furthermore, London performance statistics do not take account of the many productions elsewhere. In the late 1940s, Novello’s operettas were being performed by touring companies, repertory theatres and amateur societies all over the UK. Yet none of them made it to Broadway although some of his plays had been successful there and in Hollywood. Only Glamorous Night and The Dancing Years were given productions in the USA, and both were one-week outdoor performances given by St Louis Municipal Opera (in 1936 and 1947).33 Perhaps, his biggest triumphs in London came at an awkward time, during and immediately after World War II.

Novello preferred to label his operettas ‘musical plays’ or ‘musical romances’, but, as noted earlier, labels were often chosen for marketing reasons. He relied on others to orchestrate his music: the musical director at Drury Lane, Charles Prentice, obliged in that capacity for Glamorous Night, and, later, Harry Dacres was a trusted orchestrator. Novello’s style was influenced by Viennese music and Hungarian-Gipsy music but also carried qualities associated with British drawing-room ballads, as can be detected in ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’, ‘Rose of England’ (from Crest of the Wave) and ‘We’ll Gather Lilacs’ (from Perchance to Dream). There is, too, a flavour of music hall in a song such as ‘Winnie, Get Off the Colonel’s Knee’ from Careless Rapture, and the enduring influence on Novello of British musical comedy is recognizable in ‘Primrose’ from The Dancing Years. Novello claimed that, as a young man, Lehár was his guide.34 Thus, it is a matter of some irony that Novello composed the last ‘Viennese’ operetta to be given in London before World War II: The Dancing Years. The Jewish protagonist was played by Novello himself. The idea of the persecuted composer came to him after a friend related to him what he had seen happening in Vienna following the Nazi occupation of the city.35 The Dancing Years contained a controversial scene of Nazi officers arresting Rudi. There is a letter in the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays collection in the British Library, which shows that hostility to the Third Reich was not unanimous in Britain, even in March 1939. The writer complains about the anti-Nazi scene: ‘It undoubtedly pleased a certain section of the audience and was wildly applauded, but it jarred others and some of the people booed.’36

The last figure to receive attention in this chapter is Vivian Ellis, who began as a composer for revues, but had a resounding success with the musical comedy Mister Cinders (1929), co-composed with Richard Myers. Ellis describes his stage works Big Ben (1946), Bless the Bride (1947) and Tough at the Top (1949) as ‘light operas’, but explains that this was not a label that would draw an audience, and so the term ‘musical show’ was chosen.37 Despite that precaution, the first and third of these were modest successes only. Ellis was not an imitator of Coward or Novello: he sometimes looks back stylistically to Edwardian musical comedy and Paul Rubens in particular, but often spices up his music with elements of a syncopated style reminiscent of Jerome Kern. Sometimes, a French character can be detected, indicating Ellis’s regard for André Messager and Reynaldo Hahn.38 In composing Bless the Bride, he claims to have often turned to the score of Carina by Julia Woolf, his maternal grandmother, which had been performed at the Opera Comique, London, in 1888.39 Whereas Novello wrote music to which Hassall added lyrics, Ellis worked on all of his three ‘light operas’ with A[lan]P[atrick] Herbert, who preferred writing the words first.40 Although A. P. Herbert – as he was usually known – has been praised as ‘one of Britain’s cleverest, wittiest wordsmiths’,41 he has also been criticized for lyrics that fall ‘too frequently into the same dreary ABAB pattern, alternating feminine and masculine rhymes: ‘doing/done/brewing/sun’, and so on’, leading Ellis to compose ‘predictable tumpty-tumpty music’.42 Ellis asserts, on the contrary, that his settings were, in fact, ‘no compliant tumpty-tumpty music’ and that he ‘opened up the words for the music’.43 Ellis was not normally a fast worker, explaining that the simplest composition was the result of hours of work spent ‘altering, erasing, and eradicating any signs of effort’.44

Novello apart, Bless the Bride, with its 886 performances at the Adelphi, seems to mark the end of British operetta as a popular West End genre. Shortly after it opened, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! was produced in London, and the massive success of the latter heralded a new era of dominance of the West End by Broadway musicals. Few home-grown products could withstand this incursion, but there were two notable triumphs in 1954: Sandy Wilson’s The Boy Friend at Wyndham’s Theatre (1,740 performances) and Julian Slade’s Salad Days at the Vaudeville Theatre (2,289 performances).

Afterword

It might easily be argued that British, American and German operetta of the early twentieth century became absorbed into the modern Broadway musical. Less persuasively, perhaps, twentieth-century ballad operas, such as Ethel Smyth’s The Boatswain’s Mate (1916) and Vaughan Williams’s Hugh the Drover (1924), might be seen as precursors of the modern musical that relies on existing songs, such as Mama Mia! Most difficult of all, however, is to decide what befell comic opera. When this term is taken to be synonymous with ‘light opera’ or ‘operetta’, a case can also be made for its having been absorbed into the modern musical. Problems arise when ‘comic opera’ is intended to suggest a kinship with the high-art status of operas such as Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro or Verdi’s Falstaff. Vaughan Williams must have had this kind of distinction between art and entertainment in mind when he labelled Sir John in Love a comic opera, but The Poisoned Kiss, which he called a ‘romantic extravaganza’, has been described as an ‘uncertain cross between operetta and musical comedy’.45 High-status comic opera does not appear to have survived into the second half of the century with any degree of strength, despite the success of Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring in 1947, and Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress in 1951. Coincidentally, each of those years saw the premieres of two acclaimed productions in the West End that could be labelled operettas: Ellis’s Bless the Bride and Novello’s Gay’s the Word. After this, the descriptions ‘comic opera’ or ‘operetta’ for new stage works became a rarity.