Introduction

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on

Music is ubiquitous in Romantic literature. To wander through its poetry and prose is to encounter a landscape crowded with obscure village minstrels, prophetic bards, carefree improvisors, cruelly disfigured and rejected castrati, and enthusiastic kapellmeisters ready to cruise the job market.1 Genius composers draw us into infinite nocturnal kingdoms (Beethoven), die listening to their own sublime creations (Haydn), and return to life to haunt pubs and opera houses (Gluck).2 Here, Sappho’s song echoes as she leaps from a cliff; there, a ‘Hindoo’ girl sings a prediction of her love match; Albanian soldiers ‘half-scream’ war-ballads in the mountains; medievalising lutes sound mysteriously through the darkness to heroines imprisoned in castles; caged birds sing in praise of Waldeinsamkeit, while nightingales vie for airtime with the silent pipers on an antique urn.3

And this din largely covers just one dimension of the relationship between literature and music: the representation of music in literary texts. Just as significant for Romanticism was the new twilight zone between literature and music theory or criticism, epitomised by E. T. A. Hoffmann’s publications of the same material in music journals and collections of ‘literary’ Fantasiestücke. Finally, there is the enormous territory of Romantic literature in music, most strikingly poetry settings in lieder, and adaptations of prose for operas, melodramas, and instrumental works (Mérimée’s novella for Bizet’s Carmen; De Quincey’s autobiography via Musset for Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique; Dumas fils’s play for Verdi’s La traviata; Hugo’s novel for Claude-Michel Schönberg’s Les Misérables).

The task of this chapter is not to survey this vast field, but to ask what work music does for literature in Romanticism. The question is difficult enough, not least given the problems of periodisation endemic to studies of Romanticism. Romanticism is not contemporaneous across European traditions, and nor is literary Romanticism easily synchronised with musical Romanticism. Thus ‘Romantic’ debates over sublimity, virtuosity and naturalness, spontaneous creativity, and fidelity to the musical work are fought over ‘baroque’ and ‘classical’ compositions by Handel, Arne, Mozart, or Gluck.4 Related to periodisation are broader definitional problems, not infrequently scorned by Romantic writers themselves (‘one feels the Romantic, one does not define it’, wrote one).5 Should we talk of Romantic movements (centred on social groupings and affiliations, and often on canonical artists), Romantic eras and generations (at the risk of implying that a spirit of the age permeates all cultural productions), or of Romantic aesthetics, more or less temporally limited (since, for instance, Friedrich Schlegel famously believed ‘all poetry is or should be Romantic’, a statement difficult to fathom outside the particular moment and milieu of Jena Romanticism (1798–1804))?6

As a cluster of values, tendencies, and theories, Romantic aesthetics include engagement with philosophical Idealism, absolutes, and ideals – both ‘normative’, in the sense that art represented ideals, and ‘categorial’, in the sense that making and reflecting on art might enact ideals such as freedom, spontaneity, infinite play, indeterminacy, or autonomy.7 As autonomous, art was imagined to be non-utilitarian (not difficult in a world where personal patronage was increasingly unreliable), although it could be deeply politically and socially engaged. Romanticism was not, of course, concerned with ‘emotion’ above ‘reason’ or ‘enlightenment’, nor with individual subjectivity against community or society. It was, however, bound up with new understandings of such categories: the dominant paradigm of ‘emotions’ was crystallising in our period (alongside claims that aesthetic responses are not passionate); and eighteenth-century ideas about the shaping power of the subject’s imagination and perception took on new dimensions and urgency, leading some texts to despair of accessing reality through the ‘green spectacles’ of our own perceptual apparatus (Kleist’s letters), others to revere imagination as a ‘power’ revealing an ‘invisible world’ superior to empirical experience (Wordsworth’s Prelude), and still more to create dialectics between experience as given and self-created.8 Although metaphors surrounding imagination were often visual, the (for Romantic authors) emotionally charged and time-saturated medium of music was increasingly both a model for literary production, and a source of metaphors for subjectivity – as when Coleridge calls ‘Joy’ a ‘strong music in the soul’, given to us by ‘Nature’, but becoming ‘the life and element’ ‘Of all sweet sounds’ available to perception, ‘All melodies the echoes of that voice’ (lines 64, 68, 58, 74). These words, from ‘Dejection: An Ode’ (1802), suggest a final Romantic concern: the idea of a malady – melancholy, madness, solipsism, incurable longing – sometimes seen as a universal human asset, but often identified with specific problems of modernity, be they despotic revolutions, repressive old orders, urban and utilitarian pressures, idleness and loss of old meanings, or alienation – a mal du siècle.

Other chapters in this book help explain music’s distinctive and exalted place in this aesthetic, in particular its connection with origins, of languages and peoples, and with ends, the telos of humans’ connection with the infinite and undetermined. For our purposes, it suffices to recall the musicological argument that the failures of music within (narrowly) representational artistic paradigms became a strength when representation was seen as limited and determined, making music, in Hoffmann’s words, ‘the most Romantic of all the arts … for only the infinite is its object’.9 This leaves verbal arts in an uncomfortable position. They not only habitually represent and refer (although texts like Novalis’s Monolog (1798) will dispute this), but do so using arbitrary signs which differ between places and times, suggesting language’s ‘determination’ by society, and moreover subjectivity’s determination by language, so long as we cannot fully prise apart thought and word. Thus while Romantic theory makes expansive claims for literature – the best known being Schlegel’s that ‘Romantic poetry’, aka literature, is ‘a progressive universal poetry’ which is ‘alone infinite, as she alone is free’ – literature also faces problems which, I suggest, music helps to navigate.10

The following is shaped by two methodological approaches to the question of the work of music for literature: word and music studies, and the somewhat newer field of sound studies. The former often concentrates on representations of music and on word–music relations in text settings. It is shaped by modernist understandings of the specificity and separateness of the arts, and the poignant gaps between them (for instance, literature is silent and textual; literature aspires to but never achieves polyphony).11 Sound studies, meanwhile, following postmodern media and cultural studies, tend to assume the constructed and so changeable nature of divides between media and senses, while striking an anti-elitist stance which can sideline the ‘elite’ sources and close musical and textual analysis often found in word and music studies. Both approaches resonate with Romantic-era and pre-Romantic aesthetics – think, on one hand, of the gulf between visual and verbal arts in Lessing, on the other of Romantic ideals of synaesthesia or the reunification of the faculties (split by modern divisions of labour) in Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk. But it is sound studies’ stronger questioning of the division between the arts which particularly informs this chapter’s two broad answers to the question of the work of music.

First, ‘music’ has a strong role in forming ‘literature’, as an art, discipline, and institution whose contemporary form emerges in the latter part of the eighteenth century. A well-known marker in this process is a new division between imaginative and non-imaginative literature: in Johnson’s 1755 dictionary, ‘literature’ means ‘Learning, skill in letters’, but the term has roughly its modern scope around 1800 (for instance, in the English translation of Madame du Staël’s De la littérature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales (The Influence of Literature on Society, 1812)). Other markers include the establishment in Edinburgh of the first chair in rhetoric and belles lettres, in 1762, held by Hugh Blair, the principal champion of the supposed primitive bard Ossian; and the establishment in the 1780s of ‘philology’ in German universities (roughly equivalent to Anglo-Saxon language and literature departments). There are also new pedagogical practices, including a stress on learning reading through motherly oral instruction; changing emotional and imaginative investments in reading; and marked rises in literacy and print.12 These coincide with longings for a lost oral immediacy that supposedly existed before modern print culture, with ballad crazes, stylings of poetry as songs, lyrical ballads, or odes, and fashions for improvisation – alongside justifications of written literature as the most comprehensive art after all, reuniting sight, gesture, and sound under the aegis of imagination.13

Second, the remainder of this chapter suggests, music helps Romantic literature to fail. Perhaps paradoxically, failure is a key way of responding to and evoking ideals. What is sometimes called the ‘literary absolute’ flourished in literary theory – a genre, if not separate from, then athwart literary ‘works’. Poetry and imaginative prose meanwhile employ music to suggest ideals without needing fully to instantiate or capture them, a hubristic task and a self-defeating one insofar as these ideals are infinite and indeterminate. Failure, like music, has varied meanings and uses for Romantic literature, and one of the chief conclusions of this chapter is that, while music often evokes the universal and/or indistinct, there is also a strong alignment between music and particularity. Within the limits of any particular set of aesthetic characteristics or functions, failure thus proves a useful and wide-ranging thread running through the work of music for Romantic literature.

Loss of Sound and Certainty: Blake, Hoffmann, Kleist

The ‘Introduction’ to William Blake’s 1789 Songs of Innocence (later, following the French Revolutionary Terror, expanded as Songs of Innocence and Experience) is not a prose preface but an energetic poem. Voiced by a rural ‘Piper’ (line 7), it suggests simple oral origins through compact lines, straightforward and repetitive syntax, an elementary and rough rhyme scheme (abab) and frequently recurring sounds (especially chear, hear, clear (6, 8, 10, 12, 18, 20)). But the song – if such it is – does not insist on oral purity. It is an apparently cheerful parable about the emergence of writing from absolute music, and simultaneously about the genesis and fate of the Songs as a text.14 The piper first ‘Pip[es] songs of pleasant glee’, then, upon the request of a genius- or Christ-like child, gives these songs a programme: ‘Pipe a song about a Lamb’ (2, 5). He is next told to ‘Drop [his] pipe’ and ‘Sing’, and finally to ‘sit … and write / In a book that all may read’ (9, 13–14). Making a ‘rural pen’ from a ‘reed’, the piper ‘wrote [his] happy songs, / Every child may joy to hear’ (16–17, 19–20), creating a text that has print’s ease of dissemination (all may read) and writing’s function as record and script for performance (children may hear).

We might wonder, however, what tune the words will take, if any, and whether something has been lost in the piper’s descent from wandering to sitting, from ‘valleys wild’ to tamer stream (1), from pipe to pen, and from an immediate audience with a seraphic child to a merely potential audience of distant children. The poem does not strongly invite a suspicious reading, yet many experienced readers stumble over such questions, and particularly the ambiguity of the piper ‘stain[ing] the water clear’ (18), apparently with his pen: does writing stain the water dirty, or ‘clear’ and repristinate it? Moreover, what stains the flowing water, so suggestive of pure origins, and what is the stream’s place in writing? Is the water itself an ink, or a writing surface for the dabbling reed? In the absence of Blake or the piper to answer such questions – so the ideal of immediate presence goes – readers are free to disagree, freer and less certain than in an oral and musical ‘beforehand’. The poem thus constructs not just one ‘oral-literate conjunction’, in Maureen McLane’s words, but several.15 It allows us to imagine literature’s all-encompassing nature – its paths out of and back into orality and song – but also to question the idyll presented on the page.

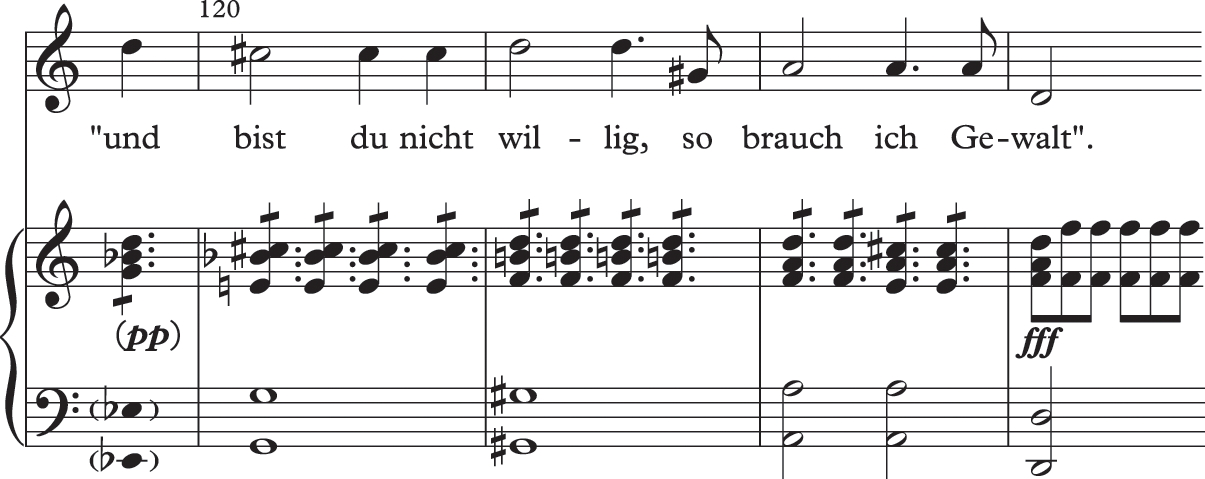

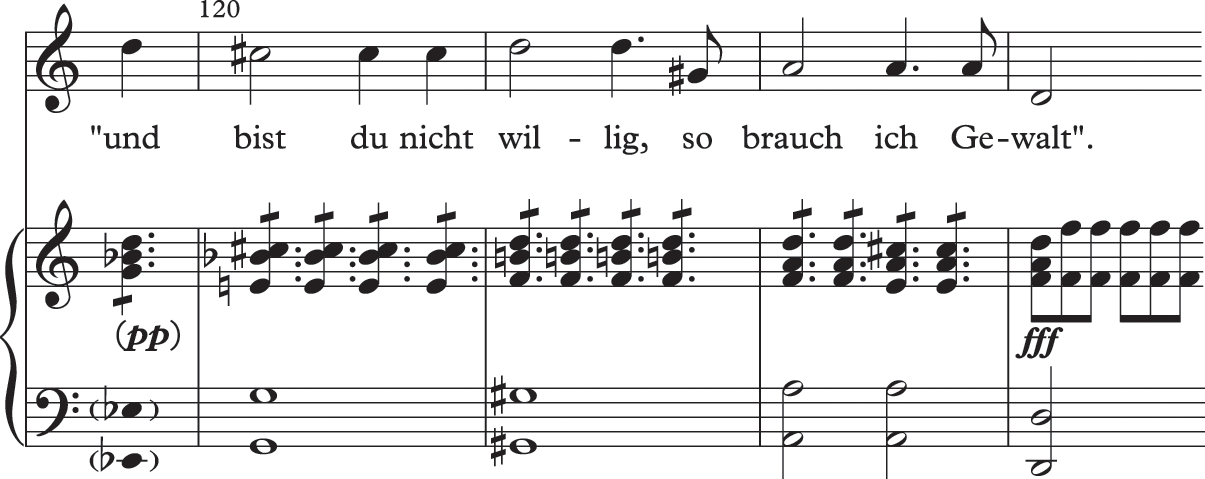

A loss of innocence is deepened in German Romantic texts which complicate their oral-literate conjunctions by acknowledging that music, as well as words, can be written, creating complex matrices of music, word, sound, and text. Kleist’s ‘Die heilige Cäcilie oder die Gewalt der Musik (eine Legende)’ (St Cecilia or the Power/Violence of Music (a Legend), 1810) and Hoffmann’s ‘Ritter Gluck’ (Sir Gluck, 1814), like Grillparzer’s Biedermeier novella Der arme Spielmann (The Poor Player, 1847), all turn on unreadable scores. In Kleist’s case, a maternal detective-figure approaches the manuscript of a mass by an ‘old master’, hoping to unlock the secret to the musical experience which miraculously converted her iconoclast sons to Catholicism. But she is musically illiterate, or at least cannot decipher this old notation. Seeing the score’s ‘unknown magical signs, with which a fearsome spirit seemed mysteriously to define its circle’, she ‘thought she would sink into the earth’.16 She, too, soon converts. What the mother, a truth-seeking Protestant, fails to read is legible by others – namely, the nuns of the apparently wealthy and well-connected convent of St Cecilia – and the reader is left wondering about the roles of divine intervention as against worldly power plays and obfuscation in the Protestants’ return to the old faith. In Hoffmann’s case, an apparition of the dead composer Gluck plays from a richly bound and printed score, yet its notes are invisible to the dilettante narrator – either a sign of his musical-philosophical tone-deafness (for he misunderstands the genius), or the sheer impossibility of translating the infinite, teeming, polymorphous ‘forms’ (Gestalten) of ideal creativity into quotidian life on the page, the letter that kills while the spirit gives life. With Grillparzer, we meet a musical text as botched and cramped as the aspirations of its atrocious ‘beggar-musician’ to unstained personal and musical harmony in a fallen world.17

In each story, music represents for some characters an ideal experience which, to others, looks or sounds incomprehensible. The fact that music is not immediately present within these literary prose texts – as sound or as writing – allows them to stage a gap between the ideal and the prosaic (the latter aligned with the writer-narrator), and furthermore to pass on this gap to the reader as a failure of certainty, the impossibility of contact with a musical ‘source’ which might prove whether the ideal was an illusion all along or not. This kind of useful failure, created by writers who were themselves composers, players, or commentators on music, contrasts sharply with the desirable failure of musical ideals with a Romantic such as Coleridge.

Avoiding the Ideal: Coleridge

One of Coleridge’s best-known treatments of music is ‘The Eolian Harp’ (1796). This rural and domestic idyll sees the poet sitting with his future wife, musing on the philosophical implications of sounds emanating from an aeolian harp. This instrument fascinated Romantic listeners because it was played by the wind, seeming to activate and manifest the creativity and harmony of nature (even ‘the mute still air / Is Music slumbering on her instrument’ (lines 33–34)). For Coleridge, the harp suggests first eroticism (‘caress’d, / Like some coy maid’ (15–16)); then the supernatural (‘a soft floating witchery of sound’ (20)); then more elevated philosophical materialism, influenced by Enlightenment nerve theory – Coleridge engaged especially with Hartley’s idea that solid nerves, vibrating like instrument strings, grounded all sense perception, movement, and thought – theory tainted by association with scepticism and pantheism.18 The speaker distances his philosophising from scepticism, and recalls the Neoplatonic Christian imagery of a world soul (long associated with music) as well as Romantic scientific work on the underlying unity of sensation and life: there is

Yet still he imagines his ‘passive brain’ being given thoughts, as the harp is given melodies by ‘random gales’, and wonders ‘what if all of animated nature / Be but organic Harps diversely fram’d, / That tremble into thought, as’ they are swept by ‘one intellectual breeze’, ‘the Soul of each, and God of all?’ (42–3, 45–9). All this looks ideal: a vision of organic and spiritual unity, and one not only formulated intellectually, but suggested by, even on a continuum with, an empirical musical experience. Moved by music, as harp strings are moved by the wind, the poem seems to enact that flow between individual and universal, mechanical ‘motion’ and ‘soul’, which it describes (28). Similar musical visions appear in Schlegel’s Abendröte (Sunset, 1802; 1.1.15–18) – where ‘Everything seems to speak to the poet / For he has found the meaning, / And the universe [seems] a single choir, / Many songs from One mouth’ – or Eichendorff’s miniature ‘Wünschelrute’ (Divining Rod, 1838):

With Coleridge, however, the ideal and the aural idyll are not the final word. In the last stanza, the speaker accepts the ‘mild reproof’ of his beloved’s ‘more serious eye’, and abandons his ‘unhallow’d’ speculations (or, perhaps better, ‘auscultations’, since this is philosophy as listening) (50, 52).19 Joy and contentment – the poet’s ‘Peace, and this Cot, and thee, heart-honour’d Maid!’ (65) – arise not from musical nature revealing itself naturally to poet-philosophers, but from the intervention of the biblical God, ‘saving’ broken natures and revealed, partially, in scripture (62). Likewise, proper poetry emerges not as enthusiastic invention, flowing from ‘vain Philosophy’s aye-babbling spring’, but humble ‘praise’ of God, ‘The Incomprehensible!’ (58, 60–61). Readers may regard the final stanza as marring the poem’s shape and sentiments. But, for the speaker, claims to ideal plenitude are dangerous, and failure to embody it a saving grace. Poetry responds to the pressures of the given: not a world spirit but actual community (the female companion), revealed religion (and its limits), and, more mutedly, an inherited poetic tradition of rural contentment, taken from Virgil’s Georgics. In this long tradition, philosophical speculation on nature is situated within quiet rural landscapes, like the one with which Coleridge begins (where ‘The stilly murmur of the distant Sea / Tells us of silence’ (11–12)); and, while Virgil’s poet-speaker asks the muses for philosophical enlightenment and elevation, he then falls back into the more humble request for a quiet life and unspectacular contentment (Georgics 2.475–89). An internal tension between sound, music, and quiet thus runs through the poem, and prepares the well-tuned reader for the fact that ‘wild’, ‘delicious’, exuberant music will help poetry to reach its necessary domestication and falling-short (25, 20).

Music plays a no less pivotal role in perhaps the best-known Romantic failure in poetry, Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’ (1797/1816). In a preface which by its nature underscores the poem’s lack of self-sufficiency (as will the marginal notes in ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’), Coleridge reports that he published this ‘fragment’ at the request of Byron, ‘rather as a psychological curiosity, than on the ground of any supposed poetic merits’.20 Romantic tropes of the exotic or ‘other’, spontaneous, and ideal are on full display. During a vivid opium dream, inspired by reading an antique travelogue which narrated the still older history of the Mongol khan Kublai, the author experienced a spell of spontaneous ‘composition’. This original poem was composed in an ideal psycho-physiological state, ‘without any sensation or consciousness of effort’, and an ideal quasi-Adamic language, whose ‘expressions’ ‘correspond[ed]’ perfectly with the ‘things’ they represented. Seeming ‘to have a distinct recollection of the whole’ upon awakening, Coleridge ‘instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines’ we know as ‘Kubla Khan’ before being interrupted by a visitor from the quotidian world.21 Fled was the vision, and the remaining 150–250-odd lines of poetry Coleridge imagined himself to have composed in his altered state. ‘Kubla Khan’ is thus presented as a monument to a lost ideal poetic experience – a witness to a ‘whole’ that is all the more evocative of perfection for being itself broken. The imaginative stakes are high, but the pressures on the words on the page relatively low. Internally, the poem also describes imperilled, utopian perfection. First, there is the ‘miracle of rare device’ that is Kubla Khan’s heterotopic ‘pleasure-dome’, arising as if by magic through his creative ‘decree’ and seemingly channelling the violent forces of nature (35, 2). Yet its pleasures and musical ‘mingled measure’ cannot drown out the labours of kingship, the sound of ‘Ancestral voices prophesying war!’ (33, 30).

Third-person description now breaks off, replaced by a first-person reflection on a past ‘vision’ of an ‘Abyssinian’ ‘damsel with a dulcimer’ (37–9). She sings of another artificial paradise, Abyssinia’s ‘Mount Abora’ (41). The speaker’s now-indistinct ‘vision’ was apparently sonic – although the visual term builds in extra distance between reader and music – since its (non)sounds become a stimulus for his own potential construction of an artificial paradise:

This conditional act of creation with its lost possible ground – music – is bracketed one further step by the hypothetical reaction of ‘all who heard’ the music: ‘all should cry, Beware! Beware!’ at the enthusiastic (and implicitly opiated) creator, should enclose him in a quasi-magical, protective triple ‘circle’ and close their eyes to him (48–9, 51). The underlying structure here is significant: an exotic woman, singing about a legendary mountain in her native land – one long associated with the hidden source of the sacred river Nile – represents poetic creation’s lost source of plenitude (a ‘loud and long’ ‘symphony’, or sounding-together (45, 43)). Moreover, as lost, the singer represents the stimulus for the existing poetic fragment, in its mode of imperfect recollection, wish, or lament, strategically distanced from an encircled ideal.

Coleridge’s very different treatments of strange stringed instruments in these poems use music to figure an ideal which it is actually in the poem’s interests to avoid. ‘Kubla Khan’ arguably has a pragmatic rationale for avoidance: the perfection of altered states cannot be communicated directly, and gesturing towards their loss becomes a good bet in persuading readers something was really there. But in both poems there is a dimension of moral danger and delusion in the ideal that makes failure to reach it valuable. What explains this danger and its alignment with music? It should be acknowledged that the scenario does not fully capture the range of music’s work for Coleridge, let alone for other English Romantics, and figures including Fanny Burney, Leigh Hunt, William Hazlitt, the Shelleys, and Thomas De Quincey engaged more closely and positively with musical culture. Nonetheless, the lurking suspicion of music in the two poems perhaps holds some trace of broader English Protestant suspicions of music as sensual distraction and self-display.22 If not typical, the poems find many echoes elsewhere. The moral questions raised in ‘The Eolian Harp’ are shared by Wordsworth’s ambivalent depiction of excessive musical absorption in ‘The Power of Music’. Meanwhile, the less clearly denounced artificial paradise of Coleridge’s opium vision is echoed by De Quincey’s depiction of the ‘Pleasures of Opium’ in his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) – recalled from the other side of this ‘Paradise’, when he has suffered and apparently overcome the ‘Pains of Opium’. Opium’s pleasures are epitomised by visits to the opera, where he heard alongside opera singers the passionate ‘music’ of Italian women speaking in the audience, a musicality enhanced by its separation from utilitarian signification – since De Quincey understood no Italian – and which he compared with the musicality of ‘Indian’ women’s speech, as recounted by a contemporary traveller to Canada.23

The connection of music with exotic women’s language deserves further exploration. It suggests associations of music with the non-semantic, a- or irrational, undetermined and vague; with passion, sensuality, wildness; and with racial, national, epistemological, and gendered otherness. These are alterities that modern male European authors might claim to harness and mediate to readers without embodying them, making music a useful ‘constitutive other’ for literature. But the exotic woman can also suggest music’s associations with things more particular, determinate, and grounded, leading us to a final and complex case of literary failure.

Exoticism and Philological Failure: Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée’s novella Carmen (1845/47) is not always counted amongst the Romantic works of this archaeologist, historical conservationist, and master of short fiction. Yet it reflects and interrogates key developments stemming from Romantic-era literature and literary-critical method, still important to the discipline today – namely historicism and hermeneutical philology. Nor is Carmen obviously concerned with music: despite her name, and unlike Bizet’s gypsy, Mérimée’s does not seduce through song. Music is incidental, scattered through the novella, integrated into larger soundscapes and broader depictions of character, custom, and place.

This is as it should be in a novella shaped by historicism, a term coined by Friedrich Schlegel but with roots in Enlightenment-era philosophy and its reception by Herder and others.24 Historicism assumed that character and action vary across nations and their specific stages of historical development; influenced by history, national languages are great repositories and transmitters of cultural specificity, revealing a people’s nature and pointing to its origins. For Herder, the origins of language and song were conjoined. The first language indeed was song, and present-day orally preserved folk songs offered a better insight into the spirit of a people than more alienated modern languages. Within the historicist paradigm, consciously or not (self-consciously in Mérimée’s case), literary authors will show the organic connection between language, social milieu, and individual plots. Literary historians and critics will give close attention to the specificities of language (philology) in order to interpret or divine a text’s original meaning (the hermeneutic task). While German Romantics are usually held to have concentrated on the specificities of distant lands or times, especially the Middle Ages, Mérimée’s friend Stendhal is credited with applying historicism to the here and now, showing in his realist novels how both unremarkable everyday mores and apparently idiosyncratic individual fates are shaped by larger socio-historical forces.25 Tellingly, Stendhal connected music with national origins and specificities in his Memoirs of Rossini (1824), recounting how the changeable timbres of Giuditta Pasta’s voice inspired in an exiled Neapolitan a vivid moonlit vision of his ‘unhappy homeland’.

Set in near-modern-day Spain, Mérimée’s Carmen combines realism with a romanticising, exotic location. Philology and historical interpretation are built into its premise: the narrator is a travelling French dilettante-scholar who comes across Carmen’s lover and murderer, Don José, during an archaeological ‘excursion’ which he hopes will prove the exact site of the classical Battle of Munda, a ‘fascinating question’ supposedly ‘holding all learned Europe in suspense’.26 The narrator recounts the ‘little story’ of Carmen to fill in time before his dissertation on Munda’s origin takes the scholarly world by storm. We soon find he is also a keen linguist and ethnographer, recording in footnotes details of language use (Carmen switches between Spanish, Basque, and ‘chipe calli’), pronunciation, and telling idioms, and using his observations in faltering attempts to discern the geographical and ‘national’ origins of Don José and Carmen herself (mistaken for an Andalusian, a Moor, or a Jew).

Music and sound are crucial here. The undercover bandit José is initially taciturn (a stance affirmed in the novella’s last sentence, which quotes a ‘gypsy’ proverb, ‘A closed mouth, no fly can enter’ (339)). The pronunciation of José’s ‘first words’ marks him as a stranger in Andalusia (3). But only his singing to a mandolin, with incomprehensible words and a ‘melody plaintive and exotic’, suggests to the narrator that he is specifically Basque (7). The song – a characteristic ‘zortziko’ – affects José in a way that on one hand reveals his ethnic traits and origins, and on the other hints at his individual character and fate. José grows ‘sombre’, ‘profound[ly] melancholy’, and resembles ‘Milton’s Satan’. ‘Perhaps, like’ that Romantic antihero, he is brooding on ‘the abode he had left behind [Heaven/Navarre], and of the exile he had earned by some transgression’ (7). (The same is true of Carmen’s only conventional musical performance, a romalis dance for a high-society party. Glimpsing this dance accompanied by ‘tambourine’ and ‘guitar’, José ‘fell in love with her in earnest’ – yet he introduces this pivotal personal moment in quasi-historicist, sociological terms, as generally characteristic of gypsies and their place in Spanish society: ‘They always have an old woman … and an old man with a guitar … . As you know, Gypsies are often invited to social gatherings to entertain guests’ (27–8).27)

José’s melancholy seems not simply associative, but directly prompted by sound’s affective and aesthetic qualities. For, much later, he tells the narrator: ‘Our language is so beautiful, señor, that when we hear it spoken far from home our hearts leap at the sound of it’ (23). Rousseau had linked sound with nostalgia – originally a longing for a specific place, one’s homeland – citing Swiss soldiers’ propensity to fall fatally ill if they heard their native (verbally incomprehensible) cow-herding songs in distant lands. This trope has a decisive narrative function in Carmen: when José, then a soldier, arrests Carmen for attacking her fellow worker, it is Carmen’s recognition of José’s Basque accent, her ability as a polyglot gypsy to speak Basque, and her false claim to be José’s compatriot which persuade him to let her escape. This plunges him into a series of punishments and transgressions ending in the lovers’ isolation and deaths. The sonic effect is double-pronged, specific and general; since not only Basque, but Carmen’s vocalising in any language (along with her laughter) always overpowers José’s reason, he claims, making him a ‘fool’, ‘drunken’, ‘mad’, bending him irresistibly to her will (24).

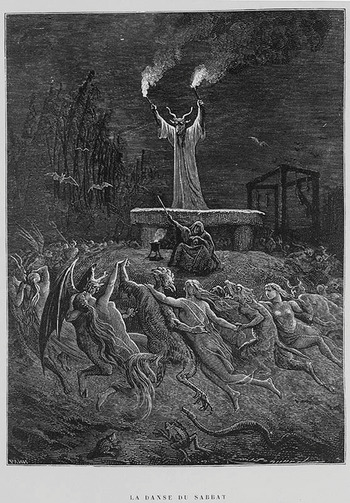

José’s response to Carmen’s voice suggests a kind of sympathetic magic: sound makes him resemble her wild and exotic character. The cluster of associations – madness, drunkenness, magic, transgression, passion, exoticism – belongs to cultural clichés about music as ‘other’ to modern rationality and rule-bound civilisation. Music represents an alluring ideal of sorts – freedoms, extremes, and rebellions in an age of staid moderation, inertia, and inward-looking pedantry (recall the ‘fascinating’ question of Munda) – but not an ideal realist literature can straightforwardly embrace. Mérimée deploys these associations in Carmen’s incidental uses of music. The lovers’ first orgiastic one-night stand begins with Carmen ‘danc[ing] and laugh[ing] like a madwoman, singing, “You are my rom [husband], I am your romi [wife]”’, before violently smashing an old woman’s ‘only plate’ to fashion makeshift castanets (30). Like her other words, Carmen’s song lies: she is already married. But on another level the music is incantatory and interpellative, helping to effect José’s deracination and transformation from an honour-bound Basque-speaker into something like a Roma. After the resurfacing of Carmen’s real rom, she will idly sing and ‘rattl[e] her castanets’ as a cover for kissing José at their shared campsite (prompting his accusation, ‘You are the Devil incarnate’, to which she replies, ‘Yes’ (39)). She ‘clack[s] her castanets’ like protective talismans or noisy carnival instruments to ‘banish’ any ‘disturbing idea’ (46), and just before her death, ‘engrossed’ in a weird mental state as she undertakes rituals that predict her murder, she ‘sing[s]’ ‘magic songs invoking’ the original ‘great Queen of the Gypsies’ (51).

This is a world where sounds are identifiers and signatures, typifying characters and groups like the timbre of an instrument. José has his Basque accent; the narrator a repeating watch (a novelty in Spain, leading Carmen to misidentify him as an upper-crust Englishman); even King Pedro I, a footnote claims, was easily recognised in a dark alley by an old woman through his ‘extraordinary disability’ of ‘loudly’ ‘crack[ing]’ ‘knee-joints’ (29). Carmen has her castanets, but gypsy sounds are also an anomaly and problem for the narrator’s methods. Polyglot, code-switching, wild, magical – these sounds of course delocalise and exoticise gypsies, failing to specify their origins or locality. The novella’s belated fourth instalment, a free-standing ethnographic sketch of the gypsies, hammers home the anomaly. Their pre-European origins are unknown; their reasons for migrating unknown; ‘strangest of all, no one knows how … their numbers soon increased so prodigiously in several countries so far apart’ (337) – in other words, even the assumption that peoples emanate from single origins is undermined. Finally, the origin of gypsy language is unsettled, and, flouting the logic of hermeneutic philology and the tie between nation and speech, ‘[e]verywhere they speak the language of their adopted country in preference to their own’ (337).

These anomalies help the novella to stage its failures and instal its central character as, not merely an enigmatic femme fatale in the tradition of French literature, but an inscrutable force of resistance and autonomy who tells her lover, ‘you have the right to kill your romi. But Carmen will always be free’ (52). José’s failure to control Carmen, and the narrator’s scholarly failure fully to place the gypsies in general and Carmen in particular, join a series of imperfections: the lovers’ deaths and failed relationship; half-accidental murders; incomplete linguistic crossings (Basque and ‘chipe calli’ are essentially closed to the narrator, and even Carmen speaks the former ‘atrociously’ (24)); the forever-suspended proof that the narrator has located Munda; incomplete plot arcs (characteristic of modern short fiction) concerning José’s death and the narrator’s promise to return a medallion to José’s mother at home – narrative promises of closure or return to origins left hanging by the focus on Carmen’s end. As in ‘Kubla Khan’, music helps to evoke lost origins, wholeness, and creative freedoms not possessed by the literary work itself judged as a set of words on the page. It creates something like a ‘transcendence’ or ‘ideality effect’, a sense of something further that literature can strive to become and represent.

Conclusion

However unappealing the stereotypes of music in a text like Carmen, the work of music within this novella and the other examples discussed aligns it with the aspirations of Romantic literature as defined by Schlegel:

Other kinds of poetry are complete and can now be fully analysed. The romantic kind of poetry is still becoming; indeed, that is its actual essence, that it can only eternally become, never be complete. … Only she is infinite, because only she is free and acknowledges, as her first law, that the caprice of the poet suffers no law above itself.28

Schlegel’s definition is both infinitely demanding and absolves literary works of embodying any perfections – classically associated with completeness – or living up to any particular ideal, since standards would make poetry determined and unfree. The ‘ideal’ of Romantic poetry can only be provided by ‘a divinatory criticism’ like Schlegel’s, not by analysing a canon of extant exemplary works.29 Romantic poetry is great in theory; in practice, in order to ‘never be complete’ it frequently cultivates smallness, showy incompleteness, and failure. Although Schlegel claims that Romantic literature has no real boundaries – ‘encompass[ing]’ multiple arts, non-arts like philosophy, and the ‘artless song’ breathed out by a ‘child’ – nevertheless one of the most effective ‘caprices’ of Romantic writers is precisely to construct limits and acknowledge laws above and outside literature – perhaps above all the law of music.

Methodologically, this observation brings home a foundational argument of media studies, now also important for sound studies and musicology, that different media have porous and changing boundaries, and, in Georgina Born’s words, exist ‘relationally’.30 This insight encourages us to see relationships between literature and music within the broader framework of sound, and to attend to matters as seemingly external to music as hermeneutic philology. This reinforces the fact that the ‘work’ of music for literature extends beyond any trope or structure such as failure, to forming the institution and discipline of literature itself. Nonetheless, the uses and timbres of failure are manifold and revealing. It might spur melancholy, frustration, madness, longing, humility, suspicion, or an awareness of interdependence. Its flipside is promise and possibility – the sense taken from Romanticism into the commonplaces of later culture: that life and art are epitomised by ‘Effort, and expectation, and desire, / And something ever more about to be’ (Wordsworth);31 the drive ‘To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield’ (Tennyson);32 that the failure of pleasure drives the formation of civilisation and individual psyches (Freud); or that, in words claimed by postmodernist ironists and popular self-help books alike, we are condemned and free to ‘Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better’ (Beckett).33 Even E. M. Forster has a little of it when he declares in ‘Not Listening to Music’ – a celebration of his failure to concentrate on or write about music – that while his ‘own performances upon the piano’ (usually Beethoven) ‘grow worse yearly’, ‘never will [he] give them up’: ‘Even when people play as badly as I do, they should continue: it will help them to listen.’34

Long regarded as the paradigmatic example of Romantic musical landscape, Felix Mendelssohn’s overture The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave), Op. 26, remains unique insofar as the surviving evidence related to its composition allows us to trace the inspiration for the work’s distinctive opening contours to a specific time and place. The broad outlines of this story are well known.1 During the summer of 1829 Mendelssohn travelled to Scotland with the diplomat and writer Karl Klingemann, a trip that included a walking tour of the Highlands and the Hebridean archipelago. On the afternoon of 7 August near the small town of Oban on the Scottish mainland, Mendelssohn attempted to document his impressions of the surrounding landscape in a pencil drawing that offers a tantalising glimpse of the archipelago for which the composer was about set sail (see Fig. 4.1). Arriving later that evening on the Isle of Mull, Mendelssohn continued to record his impressions, this time in the form of a twenty-one-bar sketch whose musical substance closely resembles the opening of the completed overture. Of particular interest here is Mendelssohn’s prefatory note in which he claims a direct connection between his own reaction to the landscape of the Hebrides and the music that he immediately felt compelled to jot down. Indeed, it is precisely the directness of this claim that demonstrates why the overture in its final form has continued to serve as an important point of reference for anyone wrestling with the fraught question of how a musical work can be said to evoke a particular landscape or, indeed, the idea of landscape more generally.2

Figure 4.1 Felix Mendelssohn (1809–47), Ein Blick auf die Hebriden und Morven (A View of the Hebrides and Morven), graphite, pen, and ink on paper, Tobermory, 7 August 1829

In the case of The Hebrides, discussions concerning its presumed connection to the place by which it was inspired have naturally been informed by other factors including, most prominently, the suggestive power of the work’s title.3 This serves to remind us that while in recent years our understanding of Mendelssohn’s overture as a ‘landscape’ has been shaped by the musical sketch and accompanying commentary described above, as is the case for many Romantic works, the perceived presence of visual and scenic elements has for most listeners been determined largely by the overture’s more immediately accessible ‘programmatic’ layer. With respect to Romantic instrumental music more generally, such programmatic layers have traditionally included work and movement titles, as well as printed programmes and other kinds of programmatic descriptions. In vocal and choral music, it is the poetry itself that has tended to play the most important role in establishing a sense of place, while in opera a similar role has been played by libretti, staging manuals, and the like. Of course, there are other kinds of texts that have been used to make interpretive claims about the relationship between music and landscape in the nineteenth century, including (1) a composer’s letters, diaries, and other writings; (2) paratexts, including autograph annotations in a composer’s sketches, manuscripts, and printed scores; and (3) contemporary performance reviews and other forms of written commentary and analysis. Whereas our understanding of the relationship between music and landscape continues to be shaped by such texts, the question of how this relationship is manifested in specifically musical terms continues to pose considerable interpretive challenges. With this in mind, I will focus my attention in what follows on two larger issues raised by Mendelssohn’s overture, both of which are relevant to the perceived presence of the visual and scenic in Romantic music in all its manifestations. I will begin by considering the claim that a musical work has the ability to evoke landscape in the first place, whether in general or specific terms. Following a brief exploration of the depiction of music and music making in Romantic art, I will turn my attention to the notion of landscape as an object of contemplation, considering it both as an activity from which composers frequently drew creative inspiration, and as a metaphor that has often been used to make sense of individual works whose musical identity is in some way bound up with the idea of landscape broadly construed.

Evoking Landscape

When Mendelssohn jotted down his musical impressions of the Hebrides in 1829, the notion that instrumental music had the potential to illustrate already had a long and distinguished history. Amongst the most important precedents are the pièces de caractère of François Couperin (1668–1733), works whose evocative titles often seem to align closely with their musical character. Of more immediate relevance is the characteristic symphony, the illustrative genre par excellence that emerged during the second half of the eighteenth century. Often remembered for their vivid depictions of storms, battles, hunts, and pastoral idylls, these works also frequently gave musical expression to a range of national and regional characters.4 While not programmatic in the Listzian sense, such works anticipate the Romantic conception of programme music insofar as their descriptive titles are often supplemented by elaborate prose descriptions. But to the extent that the characteristic symphony draws on an established tradition involving the musical representation of things or events, it is important to remember that the genre also placed a strong emphasis on human emotions and expressive content. Indeed, it is precisely this duality that allows us to make sense of Beethoven’s own contribution to the genre in his Sixth Symphony (1808), a work whose title he gave in a letter to his publisher as Pastoral Symphony or Recollections of Country Life: More the Expression of Feeling than Tone-Painting.5 Yet, as it turns out, Beethoven’s apparent rejection of Tonmalerei as suggested by this subtitle is not borne out by the completed symphony. For in addition to the numerous examples of musical illustration that can be found throughout the work, the very form of the second movement (‘Scene by the brook’) appears to have been determined by the kind of landscape it purports to evoke. In his discussion of an early sketch containing material for this movement, Lewis Lockwood has observed that underneath a preliminary version of the 12/8 figure, which in its final form has been widely understood to represent the motion of the brook, Beethoven wrote: ‘je grosser der Bach je tiefer der Ton’ (the greater the brook the deeper the tone). For Lockwood the significance of this annotation as it relates to the movement as a whole is that Beethoven ultimately went on to establish a ‘correlation between the image of the widening and deepening brook and the orchestral forces that develop the form of the movement’.6 We might even go so far as to say that it is precisely the movement’s sense of motion that ultimately informs Beethoven’s attempt to evoke this particular landscape. Indeed, as Benedict Taylor has recently proposed, ‘music can successfully model a landscape to the extent that it implicates its moving, dynamic aspects, its temporal processes’.7

Whereas the early reception of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony reflects the competing aesthetic claims embedded in the work’s subtitle, the first half of the nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of a critical vocabulary that revealed another kind of tension in the reception of Romantic music: namely, between musical works that were understood to illustrate and those that were thought to possess narrative qualities. In his discussion of the role of metaphor in nineteenth-century music criticism, Thomas Grey identifies a ‘“pictorial” mode (appealing to a range of “natural”, rather than abstract, imagery), and a “narrative” mode, which ascribes to a composition the teleological character of an interrelated series of events leading to a certain goal, or perhaps a number of intermittent goals that together make up a more or less coherent story’.8 But as Grey goes on to argue, these modes are by no means mutually exclusive:

[t]he ‘story’ conveyed by an instrumental work might, for some critics, have more in common with the kind of story conveyed by a series of images: a story expressed in mimetic rather than diegetic terms, in which levels of ‘discourse’ cannot be distinguished from the medium itself, and in which the events ‘depicted’ resist verbal summary. Furthermore, the categories of ‘pictorial’ or ‘descriptive’ music – malende Musik – most often embraced concepts of musical narration as well, at least in the critical vocabulary of the earlier nineteenth century.9

The extent to which these metaphorical modes often overlapped is made plain in a rarely discussed passage that Grey cites from the second part of Franz Liszt’s essay on Berlioz’s Harold in Italy first published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1855. This overlap is particularly evident in the context of Liszt’s discussion of the emerging interpretive tradition around the symphonies, sonatas, and quartets of Beethoven, in which critics had endeavoured, in Liszt’s words, ‘to fix in the form of picturesque, poetic, or philosophical commentaries the images aroused in the listener’s mind’ by these works.10

At first glance Franz Brendel’s often-cited tribute to Robert Schumann’s early piano works appears to offer a straightforward example of the ‘pictorial mode’. Upon closer examination, however, it becomes apparent that the way in which Brendel uses the metaphor of landscape to illuminate specific musical features in Schumann’s music does not, strictly speaking, draw on ‘natural imagery’, but rather on the representation of such images.

Schumann’s compositions can often be compared to landscape paintings in which the foreground gains prominence in sharply delineated, clear contours while the background becomes blurred and vanishes in a limitless perspective. They may be compared to fog-covered landscapes from which only now and then an object emerges glowing in the sunlight. Thus the compositions contain certain, clear primary sections and others that do not protrude clearly at all but rather serve merely as backgrounds. Some passages are like points made prominent by the rays of the sun, whereas others vanish in blurry contours. These internal characteristics find their correlate in a technical device: Schumann likes to play with open pedal to let the harmonies appear in blurred contours.11

If, for Brendel, this description pertained most directly to the Fantasiestücke, Op. 12, Berthold Hoeckner has shown that it applies equally well to Schumann’s celebrated evocation of distant sound in his Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837), specifically at the beginning of the cycle’s penultimate number, ‘Wie aus der Ferne’, where the use of the damper pedal gives rise to a distinctive texture that ‘easily compares to Brendel’s image of a landscape with a blurred harmonic background against which melodic shapes stand out like sunlit objects’.12 Given that the relationship between music and landscape being proposed here is more precisely a relationship between music and the visual representation of landscape, it is worth considering whether the desire to draw technical and formal parallels between musical composition and painting risks overinterpreting the presumed visual dimension of the works under discussion, especially given that Schumann was not attempting to compose landscape in the way that would become increasingly common in the decades that followed.

During the second half of the nineteenth century conscious attempts to compose landscape often drew on a compositional device referred to as a Klangfläche (sound sheet), a device that as Carl Dahlhaus has noted gave rise to the most ‘outstanding musical renditions of nature’ in Romantic music.13 Dahlhaus provides three examples (the ‘Forest Murmurs’ from Act II of Richard Wagner’s Siegfried, the ‘Nile Scene’ from Act III of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, and the ‘Riverbank Scene’ from Act III of Charles Gounod’s Mirielle), each of which functions as a self-contained musical tableau. Characterised by outward stasis and inward motion, these passages are suggestive of landscape in part because the Klangfläche is ‘exempted both from the principle of teleological progression and from the rule of musical texture which nineteenth-century musical theorists referred to, by no means simply metaphorically, as “thematic-motivic manipulation”, taking Beethoven’s development sections as their locus classicus’.14 Indeed, Dahlhaus goes on to observe that ‘musical landscapes arise less from direct tone-painting than from “definite negation” of the character of musical form as a process’, something that is particularly evident in the later nineteenth-century use of the Klangfläche where the status of the resulting tableaux is determined partly in relation to the larger symphonic narratives in which they are embedded.15

Perhaps even more common during the latter half of the nineteenth century are those works whose relationship to landscape is bound up with the claim that their creation has been inspired by an actual geographical locale. Amongst the most ambitious attempts to compose a large-scale instrumental work in these terms is Franz Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage (composed between 1837 and 1877), a sort of musical travelogue inspired by the composer’s ‘pilgrimages’ to Switzerland and Italy. As Liszt writes in the preface to the work’s first volume, ‘Suisse’, his aim was to give ‘musical utterance’ both to the ‘sensations’ (sensations) and ‘impressions’ (perceptions) that he encountered during his travels. How precisely this is conveyed to the listener in terms of specificity of place is, of course, more complicated. Whereas in the earliest published editions of the work each individual piece is preceded by a full-page engraving that was presumably meant to put the performer in mind of the specific locales being evoked, for most contemporary listeners the work of musical illustration would have been carried out by the individual movement titles, as well as through the use of well-established musical topics.

This desire to draw connections between musical works and the places in which they were composed has long played an important role in accounts of one composer in particular: Gustav Mahler. The history of this interpretive tradition can be traced, in part, to the testimony of the conductor Bruno Walter. In the summer of 1896 Walter visited Mahler at his lakeside retreat in the Austrian village of Steinbach am Attersee where the composer was at work on his Third Symphony. Walter later reported that as he stepped off the boat and glanced up towards the surrounding mountains Mahler offered a most unconventional greeting: ‘You don’t need to look – I have composed this all already’ (‘Sie brauchen gar nicht mehr hinzusehen, das habe ich alles schon wegkomponiert’).16 Earlier that year Mahler provided a more detailed account of his belief in the mimetic power of his own music. Commenting on the Third Symphony’s minuet, which at the time still bore the title ‘What the flowers in the meadow tell me’ (Was mir die Blumen auf der Wiese erzählen), Mahler reportedly said:

You can’t imagine how it will sound! It is the most carefree thing that I have ever written – as carefree as only flowers are. It all sways and waves in the air, as light and graceful as can be, like the flowers bending on their stems in the wind. … As you might imagine, the mood doesn’t remain one of innocent, flower-like serenity, but suddenly becomes serious and oppressive. A stormy wind blows across the meadow and shakes the leaves and blossoms, which groan and whimper on their stems, as if imploring release into a higher realm.17

In addition to his belief that this landscape served as the primary source of inspiration for the movement as a whole, Mahler also went one step further by suggesting that the listener would be able to envision Steinbach and its surroundings in the music’s very fabric: ‘Anybody who doesn’t actually know the place … will practically be able to visualise it from the music, so unique is its charm, as if made just to provide the inspiration for a piece such as this.’18 While connections of this sort have remained an important thread in the reception of Mahler’s music, such interpretive moves have also been treated with scepticism. Theodor W. Adorno was amongst the first to resist the idea that these works might reflect specific features of the landscapes in which they were composed. And while it is true that his discussion of Das Lied von der Erde makes reference to its place of composition amongst the ‘artificially red cliffs of the Dolomites’, Adorno is careful not to propose any direct link between this singular landscape and the musical fabric of this remarkable work.19 It is nevertheless worth remembering that Mahler’s symphonies have long been thought to aspire to the visual, an aspiration that is particularly evident in those passages that invoke the rich tradition of the operatic landscape tableau.

Of course, the presence of landscape imagery in Romantic music was not always bound up with these illustrative modes. Daniel Grimley has been particularly attentive to this issue as it relates to questions of landscape and nationhood in the music of Edvard Grieg, Carl Nielsen, Jean Sibelius, and Frederick Delius. And while for Grimley the idea of landscape in this music is closely tied to broader cultural formations of national identity, he also substantially broadens our understanding of this topic by drawing on perspectives from historical-cultural geography and environmental studies, including a range of ecocritical discourses. In the context of Grieg’s music, for example, he has argued persuasively that landscape is not ‘merely concerned with pictorial evocation, but is a more broadly environmental discourse, a representation of the sense of being within a particular time and space’.20 Grimley also encourages us to think of the function of landscape here both as a spatial phenomenon (through associations with pictorial images connected to the Norwegian landscape and the folk traditions of its inhabitants) and as a temporal one (involving historical memory and attempts to recover or reconstruct past events). In his close readings of individual works, he also interrogates their formal properties in a way that forces us to think about landscape not only in terms of the evocation of a particular place, but also in terms of a ‘more abstract mode of musical discourse, one grounded in Grieg’s music with a particular grammar and syntax’.21

Excursus: Making Music in Romantic Art

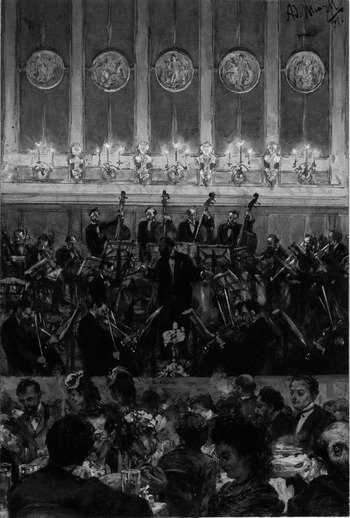

Nowhere are the connections between nineteenth-century musical culture and the visual and scenic manifested more clearly than in the depiction of music making in Romantic art. Prominent examples include Moritz von Schwind’s Eine Symphonie (1852) and Gustav Klimt’s Schubert at the Piano (1899), the former depicting a performance of Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, and the latter offering an idealised portrait of Franz Schubert. In contrast to these composer-centric canvases, the works of the German painter Adolph Menzel are particularly notable for their emphasis on the social dimension of music making. In The Interruption (1846), Menzel captures the moment in which a group of unannounced house guests interrupt two young women who have been making music in a lavish drawing room, while in Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim in Concert (1854, Fig. 4.2) the focus is entirely on the two musicians whose studied concentration reflects the intensity of an unfolding performance.22 More explicit in its diagnosis of music as a social phenomenon is Menzel’s Bilse Concert (1871, Fig. 4.3). Although the orchestra here occupies a prominent position in the middle of the canvas, Menzel devotes equal space to the audience (at the bottom of the frame) and the candlelit busts of composers who keep silent watch over the performers and their audience (at the top).23 Finally, in Flute Concert of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci (1852, Fig. 4.4), Menzel draws our attention both to the elaborate setting in which the performance takes place and to the absorption of the musicians and auditors in attendance. So popular was this painting that on the occasion of Menzel’s seventieth and eightieth birthdays it was transformed into a tableau vivant, demonstrating the continued vitality of a tradition that flourished during the nineteenth century as entertainment for the educated middle class.

Figure 4.2 Adolph Menzel (1815–1905), Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim in Concert (1854), coloured chalks, 27 × 33 cm, Private Collection

Figure 4.3 Adolph Menzel, Bilse Concert (1871), gouache, 17.8 × 12 cm, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

Contemplating Landscape

Amongst the most important functions of Romantic landscape painting was to provide the viewer with an opportunity to (re)experience the sublimity of the natural world through an act of private contemplation. So central was this impulse to the painterly imagination in the nineteenth century that the act of contemplation would itself become the focus of numerous canvases. This is particularly evident in the tradition of the Rückenfigur, in which the depicted figure is seen from behind. Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) remains the most representative example of this tradition, while Carl Gustav Carus’s Pilgrim in a Rocky Valley (c. 1820) offers a useful point of comparison in that it makes explicit the religious dimension often associated with this mode of solitary contemplation. Composers were often depicted in similarly contemplative poses, including in the Rückenfigur of Beethoven by Joseph Weidner and Arnold Schoenberg’s Self-Portrait from Behind (1911).

In the context of nineteenth-century compositional traditions this mode of private contemplation occupies a particular place of prominence in the genre of the lied. Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (1816) offers a particularly compelling manifestation of this tendency. In the first song the speaker contemplates the landscape that separates him from his beloved, a present-tense reflection shot through with a sense of melancholy that is carefully matched by Beethoven’s setting of the poem’s first stanza: ‘Upon the hill I sit / Gazing into the blue land of mist / Looking towards the far pastures / Where I found thee, beloved.’ But as the speaker begins to dwell on his own isolation, the music takes on an increasing urgency; not in the vocal line, which remains largely the same from stanza to stanza, but rather in the accompaniment, which undergoes a further intensification midway through the final stanza.

This isolation is further highlighted in the cycle’s second song, above all in the unusual treatment of the vocal line in the middle stanza. Here the melody is transferred to the piano while the singer declaims the text on a single pitch: ‘There in the peaceful valley / Grief and suffering are silenced: / Where in the mass of rocks / The primrose dreams quietly there / The wind blows so lightly / Would I be.’ To the extent that this hushed meditation reflects the experience of someone lost in thought, this moment represents a deepening of the cycle’s contemplative mode. Yet as we bear witness to the speaker’s innermost thoughts, we are also provided with an opportunity to experience the stillness of the landscape by which he is surrounded.

Although the contemplation of nature is often understood to be an act of communion that requires the subject to be quiet, reverent, and immobile, many composers had an active relationship to the landscapes they inhabited. While these composers rarely ‘worked’ outside in the manner of the plein-air painters, they often sketched as they walked. Beethoven’s pocket sketchbooks, for example, reveal the extent to which the composer’s surroundings inspired creative activity. Mahler, too, is reported to have composed in this manner, sketching out Das Lied von der Erde (1908) during the course of his daily walks through the mountain landscapes of the eastern Dolomites.24 Of course, the idea of traversing a given landscape was thematised in many nineteenth-century works, from Schubert’s Winterreise (1827) to Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (1899). In the case of Verklärte Nacht our understanding of the sextet’s narrative power is shaped in part by the eponymous poem by Richard Dehmel that was included in the first published edition of the score. Indeed, the music ultimately seems to convey the spirit and the sweep of Dehmel’s goal-oriented narrative, which begins with an unnamed woman confessing to her partner that the child she is carrying is not his. And while at the outset the night is cold and the landscape bare, through an act of forgiveness and acceptance the night is transfigured and transformed into something that is at once lofty and bright. That the narrative is presented as a nocturnal walk, recounted alternately by the narrator and the unnamed couple, is relevant insofar as the piece not only appears to reflect Dehmel’s imagery, but also possesses a musical trajectory that conveys the shifting moods of the poem. Schoenberg would later provide a detailed programme note that offers a literal mapping of poetic image and musical gesture, demonstrating the extent to which he understood this work to operate both at the level of the pictorial and the narrative.25

Whereas the musical personae devoted to the contemplation of landscape in Romantic music commonly occupied an elevated perspective (a tradition that runs from Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte to Richard Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie a century later), there is also a parallel tradition running from Schubert to Schoenberg in which the wanderers and walkers are more properly earthbound creatures, far removed from the lofty perspectives of hill and mountaintop. In the early twentieth century this tradition found an unlikely continuation in the music of Charles Ives, a composer whose embrace of the quotidian often seems to suggest a ground-level view of the world as filtered through the eyes and ears of the modern urban subject. Ives’s interest in the evocation of place is particularly evident in his orchestral works, where the use of programmatic titles making reference to specific geographical locales is often supplemented by detailed prose descriptions. In Central Park in the Dark (1906), Ives’s self-described ‘picture-in-sounds’, the composer aims to capture what might have been heard by an attentive listener ‘some thirty or so years ago (before the combustion engine and radio monopolized the earth and air), when sitting on a bench in Central Park on a hot summer night’.26 In spite of the obvious emphasis here on listening, Ives also provides a succession of richly detailed images that allow the listener to envision the source of the sounds that are being attended to so carefully by the work’s unnamed subject.

In ‘The “St. Gaudens” in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment)’, from Ives’s Orchestral Set No. 1: Three Places in New England (c. 1911–14), the act of contemplation once again plays out in the context of an urban landscape. Here the object of contemplation is Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment, a high-relief bronze that pays tribute to Shaw and his soldiers, who comprised one of the first African-American regiments to fight for the Union Army during the American Civil War. Perhaps the greatest interpretive challenge posed by Ives’s work concerns the question of what exactly this music is attempting to depict. While it is possible to identify a narrative dimension (one that reflects the ill-fated battle at Fort Wagner that culminated in the deaths of Shaw and more than half of his soldiers), when taken together with Ives’s accompanying poem this piece might also be heard as a musical response to the memorial itself, one that reflects the ‘auditory image of men moving together’.27

Finally, in ‘From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voice of the People Again Arose’ from Orchestral Set No. 2, we are presented with a composition that purports to describe an event witnessed by Ives in New York City on the morning of 7 May 1915: namely, the spontaneous reaction of a large crowd of New Yorkers to the reported loss of 1,198 lives in the tragic sinking of the British passenger ship RMS Lusitania. The illustrative power of Ives’s accompanying note makes it worth quoting at length.

I remember, going downtown to business, the people on the streets and on the elevated train had something in their faces that was not the usual something. Everybody who came into the office, whether they spoke about the disaster or not, showed a realization of seriously experiencing something. (That it meant war is what the faces said, if the tongues didn’t.) Leaving the office and going uptown about six o’clock, I took the Third Avenue ‘L’ at Hanover Square Station. As I came on the platform, there was quite a crowd waiting for the trains, which had been blocked lower down, and while waiting there, a hand-organ or hurdy-gurdy was playing in the street below. Some workmen sitting on the side of the tracks began to whistle the tune, and others began to sing or hum the refrain. A workman with a shovel over his shoulder came on the platform and joined in the chorus, and the next man, a Wall Street banker with white spats and a cane, joined in it, and finally it seemed to me that everybody was singing this tune, and they didn’t seem to be singing in fun, but as a natural outlet for what their feelings had been going through all day long. There was a feeling of dignity all through this. The hand-organ man seemed to sense this and wheeled the organ nearer the platform and kept it up fortissimo (and the chorus sounded out as though every man in New York must be joining in it). Then the first train came in and everybody crowded in, and the song gradually died out, but the effect on the crowd still showed. Almost nobody talked – the people acted as though they might be coming out of a church service. In going uptown, occasionally little groups would start singing or humming the tune.28

As was the case with Central Park in the Dark, there is a clear relationship here between the note’s descriptive detail and the work’s chaotic surface. But whereas Central Park in the Dark looks to an imagined past, From Hanover Square North attempts to capture Ives’s own lived experience as an eye- and ear-witness to the remarkable event he so eloquently describes in his note. Indeed, Ives creates a musical analogue to the ‘multiple, competing aspects of the city’ in part by dividing the orchestra into a distant choir and a main orchestra, two distinct ensembles whose relative autonomy creates a ‘visual perspective’ that allows us to ‘hear behind the foreground sounds’.29 Equally remarkable is the presence of narrative elements that foreground what Ives went on to describe as a desire to convey the ‘ever changing multitudinous feeling of life that one senses in the city’.

The Persistence of Romantic Landscape

Whereas Ives’s unique approach to the evocation of place may have found few immediate followers, the same cannot be said about the music of his British contemporaries, including Edward Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Frederick Delius, who together engaged with this tradition in a particularly influential way during the first half of the twentieth century. Indeed, it is hardly coincidental that more recent generations of British composers have continued to breathe new life into that tradition, including Peter Maxwell Davies (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise and Antarctic Symphony), and Thea Musgrave, whose Turbulent Landscapes offers an extension of the Lisztian programmatic ideal. Less obviously illustrative is Jonathan Harvey’s … towards a pure land, a work that nevertheless takes the listener on a journey towards an imagined place that Harvey has described as

a state of mind beyond suffering where there is no grasping. It has also been described in Buddhist literature as landscape – a model of the world to which we can aspire. Those who live there do not experience ageing, sickness or any other suffering … The environment is completely pure, clean, and very beautiful, with mountains, lakes, trees and delightful birds.30

Despite the staggering plurality of compositional and aesthetic priorities represented by the works of this eclectic group of composers, what binds them together is the extent to which they are part of an ongoing dialogue with musical Romanticism writ large. Indeed, their renewed exploration of the visual and scenic, as well as their engagement with questions surrounding the narrative and expressive qualities of individual works that once dominated discussions of musical representation in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, make clear the continued relevance of these traditions amongst twentieth- and twenty-first-century composers, audiences, and critics.

Less ink has been spilled over musical nationalism than blood over political nationalism – but a great deal of ink nonetheless. And arguably some blood, for the two phenomena are closely linked. Musical nationalism has supported and been supported by political nationalism: in the nineteenth century an opera performance could be the catalyst for a revolution, or a tone poem could rally the pride of a politically prostrate nation. Musical nationalism is clearly a Romantic concept – not just because modern nationalism and musical Romanticism are systems of thought that emerged contemporaneously, but because of a common idea at their nexus: ‘the folk’. It is a concept that depends on both Romanticism and nationalism to make sense, and which in return has undergirded musical nationalism. Indeed, in English, German, Russian, and other languages, ‘national music’ and ‘folk music’ began as synonyms. Over the long nineteenth century ‘national’ and ‘nationalist’ music were terms that frequently came to apply to types of art music. Yet they never separated fully from ‘folk music’. Evaluations of the ‘national’ characteristics of art composers such as Grieg or Glinka have frequently fastened on the perceived connection to folk music in their work. At other times, the connection is less direct. The iconic national status of Beethoven or Verdi, for example, has nominally been built on carrying forward traditions rather removed from folk music. And yet ‘the folk’ still lurk underneath, an indelible legacy of Romanticism.

The Nation

To unravel this knot, we should begin by tracing the history of the ideas themselves. Most historians agree that, in the form in which it has been disseminated around the world, nationalism was a phenomenon born in the eighteenth century.1 Earlier ideas of ‘nation’, ‘liberty’, and ‘self-government’ were tied to feudal fealty and competition. It was only when the idea of divine right was rejected that those who would govern had to find new answers to the question of what united ‘a people’ under their government. If, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued, government was a social contract, then who should be bound together by or excluded from such an arrangement? The answer came in appeals to (and sometimes dogged invention of) a shared culture that could become central to ‘national’ identities: languages, laws, religious customs, literature – and artistic products. ‘Cultural’ and ‘political’ nationalism have thus always been two sides of the same coin, the latter reliant on identities built up by the former. Since these identities included music, the first real assertions of ethno-national ownership of musical styles, techniques, and traditions date to the early eighteenth century.2

Such appeals to shared culture became many times stronger, however, when they could evoke ancient, mythical origins. By the second half of the eighteenth century, Europeans were increasingly encountering cultures very different from their own. More importantly, they had begun conceiving such cultures not simply as heathen outsiders of a divine order they themselves represented, but as frozen earlier stages of humanity on its fixed path away from ‘nature’ and towards modernity – stages they believed their own cultures to have passed through as well. These European ethnocentric understandings of human development were shared by so-called pro- and anti-Enlightenment thinkers, despite the fact that the former saw ‘progress’ towards the European present as positive and the latter saw it as an intangible loss. In terms of nationalism, however, it was the latter ‘Romantic’ viewpoint that most frequently shaped the discourse, because when proto-Romantic thinkers such as Rousseau began to envision modern civilisation as representing a breach with a purer, more natural human past – for which they yearned nostalgically – the idea of ‘authenticity’ emerged.3 Tracing cultural traditions backwards towards hoary natural ethnic roots could add a great essentialist force to any national claims.

The Folk and Their Music

The idea of ‘the folk’ originates from just this urge. Europeans found ‘the folk’ the moment they conceived of the natural, ‘primitive’ Other not abroad but within their own midst: as pure peasants untouched by the corrupting forces of industrialisation, urbanisation, and modernity in general. These people, seen as living preservations of any nation’s past, were first ‘discovered in plain sight’ on the geographic edge of Europe, in the Scottish Highlands. The apparent unearthing by James Macpherson of pre-Christian epics by the Celtic bard Ossian still living in oral tradition catalysed a discussion across Europe about the potential of isolated groups to create and to preserve delicate literature and music without writing. From a modern point of view, Macpherson was a fraud. He had assembled into a coherent whole his English ‘translations’ from diverse oral fragments of Gaelic poetry he had picked up, modifying them and adding the connective tissue to make them narrative epics. But these facts did not diminish the cultural earthquake caused by the Ossian publications in the 1760s. The debates they immediately spurred about non-literate creativity, collective creation versus modern reproduction, and the reliability and power of oral tradition spread across the continent, playing a prominent role in establishing modern standards of authorship and authenticity in the first place.