Expression as the Purpose of Song

On first hearing a typical eighteenth-century German song, perhaps by Christian Gottfried Krause or Beethoven’s early teacher Christian Gottlob Neefe, and comparing it to a Romantic song by a composer such as Schubert or Fauré, one might first be struck by their differences. The earlier work would be short and simple, designed for an amateur performer, requiring only a small vocal range and minimal accompaniment, while the later one might be longer, more taxing for both singer and pianist, and much more sophisticated in melody, harmony, and musical design. Despite these differences, in some ways the earlier piece would hold the kernel of what came later: the goal of expressing human experience through sung poetry.

During the eighteenth century, aesthetic preferences shifted away from the intricacy of late baroque style. Philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (who was also a novelist and composer) asserted the value of simple expressive art that was closer to nature. Intellectuals began to value and seek out folk culture (however unclearly that was defined). Music was seen as an important tool for educating and shaping children, and hence it was important to provide mothers with singable material for that purpose. All these factors combined to encourage the production of songs that could be performed by amateurs, as exemplified in collections such as Oden mit Melodien, published in Berlin in the early 1750s. Somewhat later in the century, composers such as Carl Friedrich Zelter and Johann Friedrich Reichardt began to write songs that blended the simple folk-like tone with virtuosity, creating a hybrid style: for example, a relatively simple melody might conclude with a cadenza reminiscent of opera.

Broadly acknowledged as the master whose oeuvre redefined art song, the Viennese composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828) developed a new approach to the genre. While Schubert was well aware of earlier models and wrote many strophic songs with folk-like melodies, he also used other musical forms. He was a master of modified strophic form, in which significant variation is added to the basic strophic structure. ‘Im Frühling’ (D. 882, 1826), on a poem by Ernst Schulze, provides a powerful example. A wistful but calm first stanza portraying springtime is followed by one with a more florid accompaniment, and then by a mini-storm scene that accompanies the same melody – but in the minor mode – for the third stanza, expressing the poetic character’s despair over lost love. The final stanza brings a return to major with new ornamentation. In through-composed songs modelled in part on ballads by Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg (1760–1802), Schubert abandoned strophic repetition altogether in favour of new music to go along with shifting poetic situations.

Schubert was frequently hailed for his ability to internalise and reproduce a poet’s intention, as though he could magically convert verbal into musical meaning. His friend Joseph von Spaun commented that ‘Whatever filled the poet’s breast Schubert faithfully reflected and transfigured. … Every one of his song compositions is in reality a poem on the poem he set to music.’1 Schubert used many musical techniques to express what he found through his sensitive readings of poetry. He made the piano an equal partner to the singer, often writing figurations to represent something about the outward scene, such as rippling water or a galloping horse, while the vocal part portrayed the inward experience of the poetic persona. He employed many kinds of musical nuance – altering harmonies, rhythms, phrase lengths, and more – to bring out particular words or moments of change in the text.

Schubert altered and deepened the art song in many ways – yet even as the means of musical expression grew more complex, the central goal of song remained the same: to convey textual meaning through music. Song was still idealised as being natural and unaffected, portraying the character’s experience in a direct way in order to arouse empathy and understanding in listeners.

Nevertheless, some literary figures, notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, did not like to see the symmetrical qualities of their verbal creations altered to fit new musical structures, which might seem to obscure the lyric voice. Goethe seemingly preferred the compositions of Zelter (a personal friend of his) to those of the young Schubert – at least, the poet never replied when Spaun, in 1816, sent him a carefully copied group of Schubert’s settings of his poems. Goethe’s taste reflected Weimar Classicism even as the literary world had already begun its shift towards Romanticism. Already in the 1790s, the young Friedrich Schlegel, leader of the Jena Romantic circle, had sought Goethe’s approval while also teasing and mocking some aspects of Weimar Classicism.

The genre of art song came into its own in the nineteenth century, becoming valued as a worthy art form on a par with larger works such as operas. This development paralleled the rise of the stand-alone character piece for piano. It is no coincidence that Felix Mendelssohn chose the title Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words) for several collections of piano works, paying a sort of backhanded compliment to the vocal genre by implying that music did not need a sung text to express something equivalent to poetry.

Early Romantic Concepts: Interdisciplinarity, Symphilosophy, the Fragment, and Subjectivity

Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829) was the guiding intellect of the early Romantic movement in Germany, or Frühromantik. This movement took shape during the 1790s in intellectual and social circles of Berlin and the small university city of Jena, not far from Weimar. The early Romantic ideas were intertwined with the intense personal relationships of those who first expressed them. Other key members of these Romantic circles included Schlegel’s brother August Wilhelm; Friedrich’s wife, Dorothea (a daughter of the important Jewish thinker Moses Mendelssohn; Felix Mendelssohn was her nephew) and August Wilhelm’s wife, Caroline; Friedrich von Hardenberg, who wrote poetry under the name Novalis; and the theologian and translator Friedrich Schleiermacher. The group placed high value on what Schlegel called ‘Symphilosophy’, meaning ideas that grew from shared interdisciplinary creativity.

The early Romantics were pioneers in the study of drama, literature, and the visual arts, though they had little to say about music. Moving away from the sole emphasis on ancient classics, they looked closely at European literature from the Middle Ages and beyond, disseminating their thoughts through lecture series and translations. While they deeply appreciated art in various styles, the Romantics strove to escape whatever they found overly self-contained and conventional; in their own time, they advocated what Schlegel labelled ‘Romantic irony’, meaning a kind of self-awareness within the artwork that both acknowledges and breaks away from artificiality.

Schlegel pioneered a genre he called the fragment. He wrote many of these pithy comments, and also recruited his friends as contributors, publishing fragments in sets without revealing who had written which ones (though later editors have worked out attributions). This mix of materials, ideas, and authors was intended to symbolise the interconnectedness of the universe. One of Schlegel’s fragments stated that ‘A fragment, like a miniature work of art, has to be entirely isolated from the surrounding world and complete in itself like a hedgehog.’2 Yet he also made a point of grouping fragments, creating a clear sense of relationship amongst them. This opposition between independence and connectedness was later mirrored in the art-song genre.

One of the most influential fragments was a fairly long one by Friedrich Schlegel himself on the nature of Romantic poetry. He begins by writing that

Romantic poetry is a progressive universal poetry. … It tries to and should mix and fuse poetry and prose, inspiration and criticism, the poetry of art and the poetry of nature; and make poetry lively and sociable, and life and society poetical … .

Schlegel emphasises the universality of Romantic poetry by showing how it unites opposites. Later in the passage, he focuses on the progressiveness of Romantic poetry by showing it to be an ongoing process rather than a finished product.

Other kinds of poetry are finished and are now capable of being fully analyzed. The romantic kind of poetry is still in the state of becoming; that, in fact, is its real essence: that it should forever be becoming and never be perfected.3

On first encounter, these ideas may seem contradictory. How can something called a fragment be complete in itself? What does it mean for a work of art to be a process rather than a thing? All these apparent contradictions, though, are conscious and deliberate, and they reflect the central Romantic idea of infinite striving or yearning (Sehnsucht in German). This conception of constant growth and development as a goal was drawn from other late-eighteenth-century thinkers. Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy, rather than laying out a set of rules, concludes that what humans should do is continually to seek the moral law. In Goethe’s drama Faust, Mephistopheles sets conditions stating that Faust will forfeit his soul only when he expresses complete satisfaction with a particular moment and wants to remain there rather than quest eternally onward. The belief that the answer consists of more questions was central to early Romantic thought.

These central Romantic ideas – interdisciplinarity, shared intellectual work, and the interplay between fragment and larger structure – should help clarify why, as explained in the opening chapter to this volume, Romantic aesthetics preferred art to be ‘incomplete, fragmentary, open, evolving, [and] stylistically heterogeneous, in contrast to the perceived formal unity of the works of classical antiquity’.4

Romantic poetry also strongly emphasised individual experience expressed in the first person, known as the ‘lyric I’. It should be noted that this ‘I’ can but does not always represent the poet in an autobiographical sense. A poet may write in the first person while presenting the experiences of some other character. For this reason, the phrase ‘poetic persona’ is often used to stand for the character represented by this lyric I.

Paradoxically, the individual experience portrayed in Romantic literature was frequently understood as universal. While the scenes and events of a novel or poem belong in a narrow sense to its story and main character, those particulars partake in broader archetypal experiences that were assumed to be universal, such as leaving home, falling in love, growing old, and so on. This perspective strongly contrasts the idea of our time that literature should emphasise difference and identity, showing how various individuals are set apart through their gender, class, ethnicity, race, or place of origin, and thus may experience the world in vastly different ways. The Romantic assumption of universality helps to explain why both poetry and song were intended and expected to arouse understanding and empathy.

As songs expanded beyond comfortable domestic music suitable to be sung and played by amateurs, various song types developed, ranging from tiny vignettes just a page or two long to lengthy episodic ballads. Although most were settings of lyric poetry, there were song texts in the category of epics told by a narrator, and even occasional dramatic scenas. Some songs embraced the ideal of fragmentariness by presenting a moment with no broader plot or context, while others were joined into longer sets or song cycles. Like one of Schlegel’s fragments, a song could exist in its own prickly self-sufficiency or could be combined with others into a larger collection that might or might not present a connected narrative.

Poets and Subject Matter

Schubert’s approach to song composition became a model for many Austrian and German composers, including Robert and Clara Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny Hensel, Robert Franz, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, and Gustav Mahler. Works by dozens of poets were set to music, including writers who were famous in their own right and minor literary figures whose works became renowned through their use for music. Some German poets whose works were frequently set to music were the two central figures of Weimar Classicism, Goethe (1749–1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805); others included Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), and Friedrich Rückert (1788–1866). Wilhelm Müller (1794–1827) is significant as the poet of Franz Schubert’s two song cycles Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise. Some composers, such as Robert Schumann and Hugo Wolf, preferred poetry at the most elevated level. For others, including Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Brahms, literary acclaim was not the primary concern. Both Schubert and Mendelssohn set some poems by the most renowned poets and others written by their personal friends.

Eventually, as German songs were translated and performed elsewhere, Romantic song based on these models developed in other countries. Significant composers included Gabriel Fauré, Henri Duparc, and Ernest Chausson in France; Edvard Grieg in Norway; Jean Sibelius in Finland; and Modest Mussorgsky in Russia. These later composers selected poetry that reflected the middle and late nineteenth century. For example, some French poets often used in song included Victor Hugo (1802–85), Théophile Gautier (1811–72), Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle (1818–94), Charles Baudelaire (1821–67), Sully Prudhomme (1839–1907), and Paul Verlaine (1844–96).

One inexhaustible source of poetic subject matter was nature as viewed by the lyrical subject. In his Naturphilosophie, Jena circle member Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling (1775–1854) proposed a model in which natural entities, such as rocks, mountains, or trees, are governed by something like consciousness or a soul. Just as a poetic character wandering through a natural landscape experiences it through the subjective lens of his or her own experiences and emotions, the birds or flowers also perceive that person through their own subjectivities. This is particularly evident in poetry by Heine, in which natural beings voice their own thoughts and emotions. (See, e.g., the poem ‘Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen’, set by Robert Schumann in his Heine Liederkreis, Op. 24.) Romantic poets sometimes present nature as a mirror of the poetic character’s emotional state, sometimes as an ironic contrast.

Romantic poets also addressed philosophical issues, one significant theme being the unquenchable Sehnsucht mentioned earlier. The quintessential figure of the Romantic wanderer, often represented in Romantic literature and visual art, symbolises this eternal quest, represented in poems such as Schiller’s ‘Der Pilgrim’ (The Pilgrim) and Schmidt von Lübeck’s ‘Der Wanderer’ (The Wanderer). Another topic addressed in poetry was the fleeting nature of time, linked to the notion that any moment is also eternal; this theme is found in Friedrich Leopold Stolberg’s ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen’ (To Be Sung on the Water) and Friedrich Schlegel’s ‘Der Fluß’ (The River). The Petrarchan paradoxes of love – mixing joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain – also preoccupied poets, for example in Rückert’s poem ‘Du bist die Ruh’ (Thou art Rest). All the poems mentioned in this paragraph were set by Schubert.

Many intellectuals of the period were inspired by the ideas of the American and French revolutions, so it is not surprising to find political texts and subtexts in poetry. Political commentary could be expressed openly at times – for example, nationalistic German poetry was common during the Napoleonic Wars – but for most of the nineteenth century dissent was dangerous, and political content had to be disguised to appear innocent and uncontroversial. Another important tendency was a growing interest in folk culture, grounded in the work of Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) and reflected in publications of folk-song texts and folk tales. Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn), a significant collection of German folk poetry, was published by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano in 1805 and 1808. Influenced by these writers, the Brothers Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm) published a set of 200 German folk tales, inspiring similar collections in other countries.

Metaphorical Uses of Nature in Three Songs

The following case studies explore three songs, along with the cycle from which one is drawn. Each poem uses a natural scene in both a descriptive and metaphorical way. Through these examples, one can absorb some of the central elements of how the Romantics understood and experienced the world around them.

Schubert’s ‘Am See’, D. 746: Pantheistic Reflections on Nature

This song, composed around 1822 or 1823, is on a poem by Schubert’s friend Franz Ritter von Bruchmann (1798–1867). Though not primarily a poet, here Bruchmann invents an ingenious two-layered metaphor combined with a play on words. The poem evidently captured Schubert’s imagination, as shown by his evocative musical response.

Note first that lines 1–3 of the first stanza are very similar to lines 2–4 of the second, with two changes. The word ‘See’ (lake – here in the possessive form) is replaced by ‘Seele’ (soul). In German, these two words sound very similar, so there is a play on words (Wortspiel) to match the poem’s playing waves (Wogenspiele). Second, instead of falling ‘through the sunshine’, the stars are described as falling ‘from heaven’s gate’. These three lines and their varied repetition set up a developing metaphor in two layers. The ‘stars’ that fall into the sparkling water in the first four-line stanza are not actual stars, which cannot be seen in the daytime. Instead, the word ‘stars’ stands for the dancing particles of light that bounce off the lake’s rippling water, something most people have experienced when at the shore. While grounded in the physical world, this image strongly hints at some kind of deeper significance, which is offered by the second quatrain. Beginning with the mysterious phrase ‘When man has become lake’, this stanza sets up a spiritual metaphor parallel to the earlier physical one: just as the reflected light pours into the lake, so do heaven’s stars fall into the transmuted soul.

The phrase ‘when man has become lake’ might mean all humans merging together into a single consciousness, like the drops of water in a lake, or might represent the idea that when we die, our souls join the natural world. There are other possible interpretations as well; Bruchmann leaves this open for each reader to interpret. No matter what specific meaning one reads into the poem, the image of human souls flowing into the cosmos is closely linked with a religious outlook dating back to ancient times. Pantheism – the belief that the divine is distributed throughout the world, rather than only in a god or gods – fit very naturally into the Romantics’ perspective and their strong bond with nature. Just as the arts became somewhat of a substitute for formal religion in the nineteenth century, so did the beauties of nature, and this poem’s implication that a human soul can merge into the lake is part of this outlook.5

In Schubert’s musical setting, the piano accompaniment replicates the lake’s waves in a way that is both visible and audible. In each of the first eight bars, a wave begins low in the left hand, arches up through an arpeggio continued by the right hand, and then crests, falling by a tritone as another wave begins in the left hand. This figuration aptly represents the unceasing pattern of waves: as each one crashes onto the shore, its successors are already growing and approaching from farther away.

The vocal line also mimics the arching pattern of waves and uses descending tritones in two inverted forms: A♭3–D3 and D4–A♭3. The repetition of this dissonant interval creates a sense of yearning that is especially poignant when D, the leading tone, descends by a tritone rather than ascending a half-step to the tonic. Schubert sets up a drive towards ascent when the voice part leaps a third up to F4 (a seventh above the bass) on the expressive word ‘ach’, preceding an overall descent to the tonic E♭3 at the end of the phrase (see Ex. 16.1).

Example 16.1 Schubert, ‘Am See’, D. 746 (1822/3), bb. 1–13

In the middle section (not shown), there are two more arrivals on F4, which remains the highest pitch of the vocal line. In the song’s final eight bars, as the word ‘ach’ sounds once more, an upward leap of a perfect fourth lands on G4, bringing a gratifying sense of culmination. The first quatrain’s physical metaphor about light on the lake presses upward as far as F (scale degree 2); the metaphysical metaphor of stars penetrating the soul alights on G (scale degree 3), which reveals itself to be the aural goal (see Ex. 16.2). Schubert chooses to repeat the final line of text, though – and to finish off the song, he twice repeats the stepwise descent from F4 to E♭4 on the word ‘viele’, so that the song’s final expressive declaration returns from that great climax to the earlier experience of incompleteness and Sehnsucht.

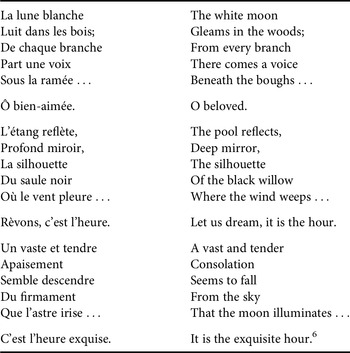

Fauré’s ‘La Lune Blanche’: Nature as a Setting for Love

This song is part of the cycle La Bonne chanson (The Good Song, composed 1892–4), which sets nine poems by Paul Verlaine, but it will be discussed on its own for the purposes of this chapter. Here, nature is a setting for intimacy, bliss, and fulfilment. This song differs greatly from ‘Am See’ in both musical and poetic language. The poem is divided into three parts, each with two layers. In each part, a set of five lines describes the outward scene, followed by a single line addressed directly to the poet’s beloved. Those three separated lines make up their own brief poem describing the subjective experience of the lovers.6

Whereas the piano prelude to ‘Am See’ introduces those falling tritones that prefigure the vocal line, Fauré begins here with shimmering, static triplets played pianissimo. Along with the key of F sharp major, this opening establishes a sense of nature’s fragile beauty, preparing us for the lovers’ expectation and readiness for this ecstatic experience. The triplet motif, moving through various chords, continues for much of the song, tapering off only in the last stanza, soon after the metre changes from 9/8 to 3/4. Both piano and voice live in a world of constantly shifting harmony. Shifting accidentals and enharmonic reinterpretation of notes (e.g., B♭ respelled as A♯) reinforce the musical ambiguity and evanescence. Subtle shifts in accidentals and chords create slight alterations in atmosphere. As Graham Johnson writes, ‘[t]he deep mirror of the pool glints with the colours of many different changing harmonies … a kaleidoscope of sound’.7 We find a remarkable example of this in the song’s last twelve bars (see Ex. 16.3). Focusing simply on the melodic line in the right hand, we see the same basic figure four times: a stepwise line ascending from F3 or F♯3 to D4 or C♯4. Each of the first three melodies is slightly different, though, until the last occurrence finally repeats what we have just heard. Analysis of the specific chords and ‘reasons’ for these variants would be of some interest, but ultimately the kaleidoscope exists for its own sake rather than that of some larger harmonic plan.

Example 16.3 Fauré, ‘La Lune blanche’, from La Bonne chanson, Op. 61 No. 3 (1892–4), bb. 38–49

Except through pauses and a shift of metre the first time, Fauré does not clearly separate the two poetic layers. (For the sixth song in La Bonne chanson, ‘Avant que tu ne t’en ailles’, whose text also presents two separate and converging stories, he made a different choice, using changes of both key and metre to distinguish the layers.) In ‘La Lune blanche’ the composer unites the two layers of text, as if to show how their contemplation of external beauty intensifies the intimate experience of the two lovers.

Like ‘Am See’, this song illustrates the Romantic affinity with nature. It might be argued that the song and poem together also demonstrate the ambiguous potential of the fragment. While Verlaine separates the poem into two layers that could be thought of as intersecting fragments, Fauré transforms them through his music into a more unified experience.

Schumann’s Eichendorff Liederkreis, Op. 39: An Assemblage of Fragments – Nature as Soulmate

This set of twelve songs, dating from 1840, is linked through the authorship of Joseph von Eichendorff. Many of the poems were originally written for various characters in Eichendorff’s fictional works, making this a very clear example of how the ‘lyric I’ is not necessarily equivalent to the poet. Eichendorff later published them in a poetry collection in 1837, separated from the specific circumstances of the fiction – but even so, Schumann’s decision to combine them into a set to be performed together altered their intent and meaning. Any connectivity or narrative in the set originates primarily from Schumann – and also from a shared tone and spirit belonging to Eichendorff’s work. Barbara Turchin, citing critics Theodor Adorno and Karl Wörner, writes of a ‘poetic structure based on mood and feeling’ that ties the Liederkreis together, offering the idea of ‘two expressive arches’, songs 1–6 and 7–12, that unfold in parallel ways.8 Benedict Taylor proposes, on the other hand, that the lack of clarity as to whether these songs are connected or separate is a central part of our experience: ‘the tension between the two alternatives is the most crucial factor in coming to an aesthetic understanding of the work’.9 This quality of being separate yet linked can be tied to Schlegel’s ideal of the fragment and his practice of grouping fragments and publishing them as sets. While each poem and song has autonomy, it is also presented within a set, enticing and perhaps compelling listeners to seek relationships amongst the individual members. The following discussion points out a few possible connections.

One strong factor that may predispose listeners to seek a narrative trajectory in the set is that the persona of the first song is melancholy and isolated, while the persona of the last song is in a joyful partnership. In each of these poems, metaphors drawn from nature express the situation. In the first poem, a threatening storm symbolises the persona’s alienation and separation from home, and in the final one the poet declares that a group of natural entities (moon, stars, grove, and nightingales) is crying out that ‘she is yours!’ Also, the cycle is framed by a tonal bond between these two, as the first song is in F sharp minor and the last in F sharp major. These correlations encourage the idea that the set tells a story about moving from loneliness to a fulfilling love, even though it is difficult to account for some of the intervening songs.

The songs are held together in shifting combinations through a network of related themes, ideas, and musical qualities. For example, song 7, ‘Auf einer Burg’ (In a Fortress), shares a contrapuntal, fugue-like texture with song 10, ‘Zwielicht’ (Twilight), while its text seems more related to song 3, ‘Waldesgespräch’ (Forest Conversation) and song 11, ‘Im Walde’ (In the Forest). ‘Zwielicht’ warns that twilight is a dangerous time when no one can be trusted. Reflecting the Romantic interest in folklore, the other three songs (3, 7, and 11) depict legends and traditions with a mix of nostalgia and dread. ‘Waldesgespräch’ tells of a man who rescues a lost woman in the forest, only to discover that she is a witch; she calls herself ‘Lorelei’, referring to a related story of a mermaid or siren in the Rhine River. This song is in the ballad tradition; to conjure up a sense of narration, Schumann constructs a lulling piano part that combines octaves and fifths in the left hand with horn calls in the right. ‘Auf einer Burg’ describes a knight turned to stone who silently witnesses events of the present time; it refers to the legend that Friedrich Barbarossa, a Holy Roman Emperor in the twelfth century, is sleeping in a cave and will awake in Germany’s hour of need. The poem ends ominously with a picturesque wedding at which the bride is weeping, suggesting that modernity has spoiled the old sacred rituals. ‘Im Walde’ also questions traditional customs: after describing a wedding and a merry hunt with bouncy, fanfare-like piano figurations, it ends slowly and legato, in the first person, on the line ‘Und mich schauert’s im Herzensgrunde’ (And I shuddered in the depths of my heart).10

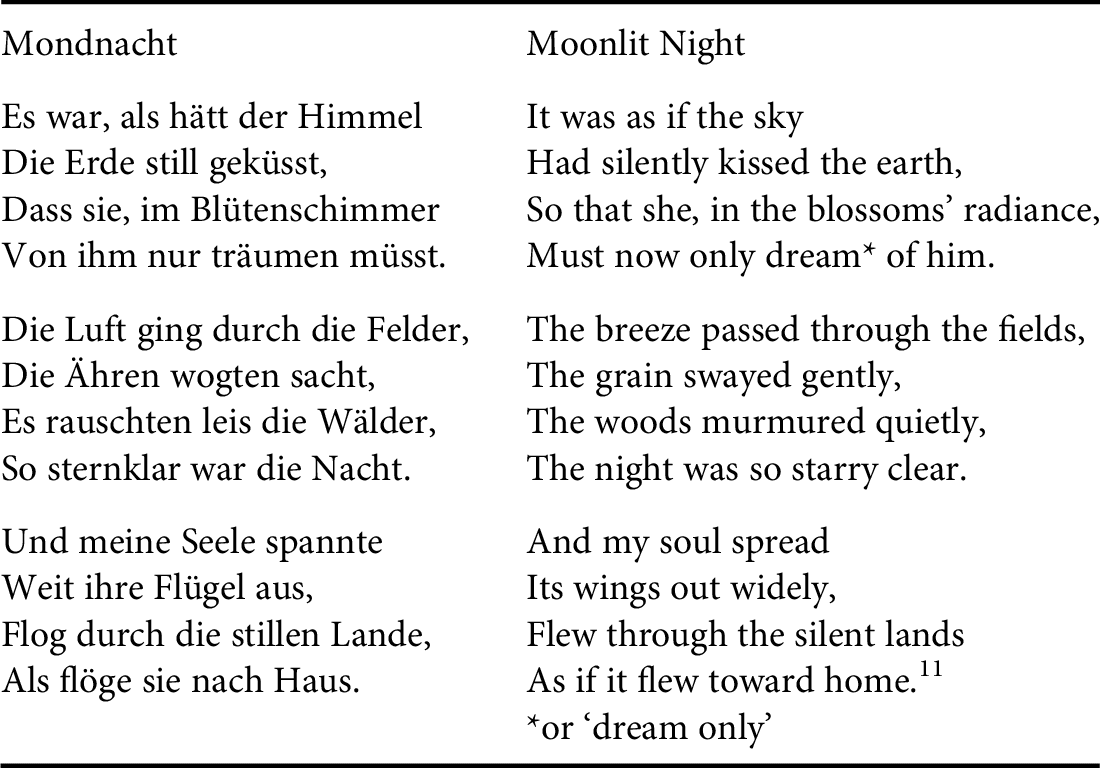

For a closer look, consider the song ‘Mondnacht’, the fifth in the Liederkreis. Like ‘La Lune blanche’, this song describes a moon-illuminated landscape, but here there is only one viewer rather than two.11

This atmospheric poem is typical of Eichendorff, combining his interests in the special qualities of particular landscapes and times of day. After two stanzas of third-person description, the text suddenly reveals the existence of a lyric I who shifts from being an observer to a participant in the exquisitely tranquil scene. Eichendorff also creates compound words, as one can easily do in German: the expressive quality of ‘Blütenschimmer’ (blossom-shimmer) and ‘sternklar’ (star-clear) cannot be fully rendered in normal English.

For Schumann, the poem inspired a structure based largely on variants of one phrase:

P – AA – P – A′A″ – BA‴ – P′

The phrase P represents the piano prelude, interlude, and postlude, while A and B are phrases for voice and piano together. Each poetic stanza is presented in two musical phrases, with five of these six phrases being very similar (here marked ‘A’ in various forms). After the first stanza, each iteration of A adds harmonic notes that thicken the texture. Stanza 3 begins with the new B phrase – this significant arrival of unexpected new music reflects the presence of the lyrical subject – and then returns to the central phrase of the song with yet another version of the accompaniment. Just as the poem begins with the personified earth and sky and then adds specific elements of fields, woods, and so on, the harmonic landscape is similarly altered and enriched by new chord tones.

Example 16.4 shows the P and A phrases. Schumann begins with an unusual five-bar phrase that should perhaps be considered as four bars of action followed by a held breath that suspends time. The left hand plays B1, followed by a C♯6 in the right hand: two notes, just over four octaves apart, that symbolise the earth and the sky; the descending melodic lines then suggest the sky leaning far down to kiss the earth even before that text has been sung. In b. 5, the right hand begins a repeated semiquaver pedal tone on B that continues for much of the song, though occasionally replaced by the notes on either side, A and C♯. It is also noteworthy that Schumann pairs the B with those two adjacent notes, creating gentle dissonances that may signify the ‘shimmer’ of the flowers. This impressionistic depiction is only intensified by his addition of chord tones as the song progresses.

Example 16.4 Robert Schumann, ‘Mondnacht’, from the Eichendorff Liederkreis, Op. 39 No. 5 (1840), bb. 1–22

Conclusion: Song as Mystic Unity

In the eighteenth-century model of song, the addition of music supported the expression of a poetic text without overshadowing the original. During the nineteenth century, Romantic composers deepened the expressive qualities of the genre. They devised many ways to go beyond simple supportive depiction of the poetry, adding new layers of meaning. A Romantic song might develop musical symbols and processes to illustrate and intensify poetic metaphors. It might reshape our understanding of a poem in a way the poet did not foresee. It might draw on chords and pitches that are easier to understand intuitively than to explain through a music-theoretical model. Romantic song epitomises the intermingling of the verbal and musical realms, bringing out the interconnectedness of the universe that the Frühromantiker celebrated. Whether standing alone in its prickly individuality or combined with others into a cycle, any Romantic song embodies the mystic unity of thought, image, and sound.