‘On the whole’, Robert Schumann wrote in a review of a number of newly published sonatas in 1839, ‘it would seem that [classical] form has run its life course, and this is surely in the order of things, for we should not repeat the same things for centuries but rather have an open mind to what is new’.1 Schumann, the arch-Romantic, is presenting here in nuce his view of what a responsible composer should do: something ‘new’. In doing so, he pitches the Romantic (the ‘new’) against the classical (‘the same things’ that should not be repeated forever), casting the Romantic as non-classical, perhaps even as anti-classical. This familiar rhetoric is common amongst Schumann’s contemporaries; about a decade and a half later, for instance, Liszt would similarly insist on ‘new forms for new ideas, new skins for new wine’.2

This anti-classical rhetoric, however, contrasts starkly with what actually happens in Romantic music, including Schumann’s and (at least until 1860) even Liszt’s. Much of what composers wrote between, say, 1820 and 1890 shows a surprisingly high level of continuity with the formal language of earlier generations. One wouldn’t want to go so far as to claim, with the mid-twentieth-century German musicologist Friedrich Blume, that classicism and Romanticism are ‘no[t] discernible styles’, but ‘just two aspects of one and the same musical phenomenon’; when taken literally this verges on the nonsensical – there obviously are stylistic differences between classical and Romantic music.3 Yet when Blume later elaborates that ‘genres and forms are common to both and subject only to amplification, specialization, and modification’, then that opens a much more nuanced perspective.4 The picture of Romantic music that comes into focus here is of something that is not anti-classical, but post-classical: rather than abandoning what existed before, it engages in a creative dialogue with the classical tradition, especially the one often associated with the works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.

When it comes specifically to musical form, classical formal types by and large survive throughout the nineteenth century. This applies to both the large and the smaller scale – from the form of an entire movement to the internal organisation of one of its themes. In this sense, the musical forms of Romanticism are often the same as those of classicism: sonata form or sonata-rondo, small ternary or sentence, and so on. Those same forms are, however, treated differently in the nineteenth century than they were in the late eighteenth century – and, in fact, treated differently at different times and places in the nineteenth century as well. Indeed, although Romantic form obviously is a nineteenth-century phenomenon, it would be wrong to equate it with nineteenth-century form as such. For the purposes of this chapter, Romantic form is understood narrowly as a set of practices that is especially prevalent in the works of a group of composers working in Germany between 1825 and 1850, commonly termed the ‘Romantic Generation’, and that survives in the music of selected composers until the final years of the century. Formal practices at other times and places in the nineteenth century (for instance in primo ottocento Italian opera) are often very different from the ones described here. Using examples drawn from vocal and instrumental works by five different composers (in chronological order: Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Richard Wagner, Clara Schumann, and Antonín Dvořák), this chapter explores some of these typically Romantic formal tendencies as well as the ways they relate to theoretical models that have been developed for classical music. The chapter is organised in two sections. The first addresses matters of formal syntax, that is, the construction and interrelation of musical phrases, under the rubric ‘Proliferation, Expansion, and Form as Process’; the second (‘Fragments and Cycles’) explores issues of formal incompleteness as well as connections that go beyond the single-movement level.

Proliferation, Expansion, and Form as Process

When looking closely at Romantic music, the analyst with a working knowledge of recent theories of classical form will find that many of its building blocks are similar to those in the music of earlier composers.5 This is true for all levels of musical form. For two- or four-bar units no less than for passages of several dozen bars long, it is often immediately obvious what their formal function is – their role in the larger form, for example the basic idea of a sentence, or the subordinate theme of a sonata-form exposition. The way in which different levels of form are related in Romantic music, however, can be quite different from what one finds in classical form.

One way this manifests itself is in more complex thematic structures. An instructive (even though perhaps unexpected) example of a Romantic theme comes from the fast portion of the Dutchman’s aria ‘Die Frist ist um’ from Wagner’s ‘Romantic opera’ Der fliegende Holländer (1840–1, see Ex. 15.1). The theme begins with an eight-bar sentence that could hardly be clearer in its internal organisation (even though its tonal organisation may seem quite outlandish): a two-bar basic idea and its repetition, together prolonging tonic harmony, followed by four bars of continuation (with contrasting material and a faster harmonic rhythm) that lead to a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the dominant minor. In the next eight bars, this sentence is restated, now with its continuation modified so that it modulates to flat-V. In classical form, the only common situation in which a modulating sentence is combined with its parallel restatement is in a compound period, where the former, leading to a weaker cadence (usually in or on the dominant), functions as an antecedent and the latter, leading to a stronger cadence, as a consequent. But such a reading is difficult to support here: the cadence in the dominant at b. 16 is in the minor mode, thus resisting automatic reinterpretation as a half cadence (HC) in the tonic, and the consequent, rather than returning to the home key, moves even farther away from it. Instead, the two parallel sentences function as the presentation of a much larger overarching sentence. The following sixteen bars indeed take the form of a continuation, starting with a repeated four-bar fragment and closing with a four-bar cadential unit (note the cadential progression V6/iv – iv – V7 – i) that is also repeated and leads to a PAC in the supertonic. Echoing the internal formal structure of each of the two halves of the presentation, this continuation can itself be heard as loosely sentential, with its first eight bars taking the place of a presentation and the next eight as a double continuation.

Example 15.1 Wagner, ‘Die Frist ist um’, from Der fliegende Holländer, Act 1 (1840–1), bb. 1–34

What this analysis shows is that there is little in this theme at the two-, four-, or eight-bar level that we cannot accurately describe with a concept familiar from classical form, and that those concepts are readily applicable with only minimal modifications. The larger constellations in which those building blocks appear, however, are different. They illustrate a mode of formal organisation characteristic of much Romantic music and for which Julian Horton has coined the term ‘proliferation’.6 Units of the length of a simple classical theme (i.e., of approximately eight bars in length) are nested within relatively long and hierarchically complex thematic units. In Wagner’s theme, the eight-bar sentence appears at the lowest level of formal organisation. It is not the whole theme (as in a simple sentence); it is not at the level of the antecedent and consequent (as in a compound period); it is at the level of the basic idea – that is, what in classical practice is the two-bar level. This degree of hierarchical complexity is virtually non-existent in classical music. And the form-functional proliferation that leads to the hierarchical complexity is itself a form of expansion: a technique used to generate larger structures. In one respect Wagner’s theme is somewhat atypical. In spite of its expansion and hierarchical complexity, it maintains a classical balance in its internal proportions, so that there is something architectonic about it. On the basis of its first building block (the opening eight-bar sentence), one can accurately predict the length of the entire thirty-two-bar theme, just like in a textbook classical sentence.

More often than not, expansion in Romantic music distorts a theme’s internal proportions. An example of what this can look like is the finale of Mendelssohn’s Piano Sonata in E major, Op. 6 (1826). This movement juxtaposes classical and Romantic modes of formal organisation with almost didactic clarity. The exposition stands out for its formal transparency. Both its interthematic layout and its cadential structure could hardly be more straightforward: main theme in bb. 1–16 concluding with a PAC in the tonic; modulating transition (bb. 16–38) leading to an HC in v; subordinate theme group in bb. 39–69 ending with a PAC in V, codetta turning into a link to the development (the exposition is not repeated) in bb. 69–76. The recapitulation, by contrast, is much more formally adventurous. Rather than by and large replicating the exposition’s modular succession, it thoroughly recomposes it. This recomposition itself as well as the specific techniques Mendelssohn uses are highly characteristic of Romantic form.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the recapitulation’s subordinate theme. In the exposition, the subordinate theme group consisted of two distinct thematic units: a highly regular compound period concluding with a PAC (bb. 39–54) and its repetition, structurally identical but with the right and left hands exchanging roles (bb. 55–69). In the recapitulation, by contrast, there is only a single, but hugely expanded, subordinate theme. At b. 154, the compound period from bb. 39–54 returns, with one crucial difference: in the very last instant, the PAC that concluded the theme in the exposition is evaded (note the telltale V42–I6 in bb. 169–70). This evaded cadence (EC) launches a process of expansion that postpones the eventual arrival of the PAC by no fewer than seventy-three bars all the way to b. 243.

The expansion happens in several steps, shown in Ex. 15.2. The EC at b. 170 is immediately followed by two renewed approaches to the cadence. The first (bb. 170–3) is swift but abandons the cadential progression before ever reaching the required dominant in root position. The second (bb. 174–86) proceeds in broader strokes and does lead to a PAC. As if to reinforce the arrival of the cadence, the progression leading up to it is immediately repeated. Yet the repetition instead undoes the closure that was previously achieved when the expected PAC is evaded at b. 190. The next attempt at a cadence (now using material derived from the main theme) does not lead to a PAC either, but to a deceptive cadence (DC, b. 199). The DC is elided with a full-on return of the main theme that culminates in a very long and promising expanded dominant at b. 206. Instead of resolving to the tonic, however, the dominant goes into overdrive (note the change in time signature and tempo at b. 217) before losing steam. Only the unexpected return of the main theme from the first movement leads to a successful cadence, first an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC; b. 232), then a PAC (b. 243).7

Example 15.2 Mendelssohn, Piano Sonata in E major, Op. 6 (1826), iv, cadential approaches between bb. 167 and 243

The cadence at b. 243 is the end point of the thematic process that started at b. 155. The subordinate theme in Mendelssohn’s recapitulation is thus considerably longer than expected – both in comparison to the original subordinate theme from the exposition, and measured against the dimensions the beginning of the subordinate theme in the recapitulation suggest. In contrast to Wagner’s theme, it is impossible to predict how long it will be; rather than architectonic, the expansion in Mendelssohn’s theme presents itself as a process that unfolds over time. Step by step, the theme grows longer, before the listener’s ear, as it were.

It would be too simple to call all of the music between bb. 155 and 243 a subordinate theme, however. Especially the change in tempo and metre, as well as the return of material from the first movement, are distinct features of a coda. Yet the structural position of a coda is, by definition, post-cadential. It comes ‘after the end’, when the recapitulation, and with it the sonata form as a whole, has achieved structural closure by means of a PAC in the home key at the end of the subordinate theme. What is remarkable about the end of Mendelssohn’s movement is that the coda begins before the subordinate theme has ended; both functions, which normally appear consecutively, temporarily overlap. The technical term for this is ‘formal fusion’: subordinate theme and coda are fused together within one formal unit, without it being possible to determine where one ends and the other begins. A listener attuned to formal functions may perceive this fusion as a gradual transformation from one function to another, a ‘process of becoming’, to use the phrase coined by Janet Schmalfeldt.8

Proliferation, expansion, and processual form remain important characteristics of Romantic form throughout the nineteenth century. The procedures used in the subordinate theme in the first-movement recapitulation of Dvořák’s Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81 (1888) are strikingly similar to the ones Mendelssohn used more than half a century before. The subordinate theme begins with a large-scale antecedent in bb. 335–52 (this unit is also another example of proliferation, since it consists of two smaller parallel phrases that each have the structure of an antecedent). At b. 353, the large-scale antecedent is answered by a parallel consequent that initially seems to be compressed, heading for a PAC already at b. 356. The anticipated cadence is, however, evaded, and only materialises thirty-five bars later, at b. 391 (the PAC in the piano is covered by the first violin). Yet being in the submediant rather than the tonic, the cadence at b. 391 cannot be the structural end point of the recapitulation. A PAC in the home key arrives only at b. 422, well into coda territory. A process that would normally take place within the recapitulation (the attainment of structural closure) thus spills over into the coda. Like in the Mendelssohn movement, the recapitulation and coda are fused.

A difference between Mendelssohn’s and Dvořák’s movements is that in the latter, expansion is not limited to the recapitulation, but plays a role in the exposition as well, most notably in the main theme. After a two-bar introductory vamp, the exposition begins with a broadly proportioned periodic hybrid (compound basic idea+continuation) leading to a PAC at b. 17. The sudden changes in thematic-motivic content, dynamics, mode, and texture at the moment the cadence arrives all suggest the beginning of a transition. This impression is confirmed when an HC in the dominant arrives at b. 37, followed by a standing on the dominant and a medial caesura; it is not hard to imagine how the unison caesura-fill in the piano right hand could have served as an extended pickup to a subordinate theme in the dominant around b. 47. But this is not what happens. Instead the music makes a volte-face, turning the tonic of the dominant back into the dominant of the tonic and leading, via a dreamy transformation of the opening theme, to a full restatement of bb. 3–17. Like the one at b. 17, the PAC at b. 75 is elided with a transition (again there is a change of mode, texture, thematic-motivic content, and, to an extent, dynamics) that first leads to an HC in the tonic and then, in the last instant, to an HC in iii, the key in which the subordinate theme finally enters at b. 93.

The first ninety-two bars of Dvořák’s exposition are an example of the specific type of processual form that Schmalfeldt calls ‘retrospective reinterpretation’: the listener who initially interpreted the unit starting at b. 17 as a transition is forced to reinterpret that same unit as part of a complex main theme when it is not followed by a subordinate theme but by a return of the opening melody. Like in the subordinate theme, the scope of the form is enlarged before the listener’s ears, in real time. The initial impression is that of a modestly sized main theme, and a ‘sonata-form clock’ – the speed at which we move through the different way stations along the sonata-form trajectory – that is ticking fast.9 The reinterpretation of the seeming transition turns the clock back, as it were: we are not yet where we thought we were, and the main theme group is much larger than we initially thought it was. The expansion thus emphatically takes the form of a process that plays out over time, and that is difficult to capture in a schematic overview (this is true of much music, but it has been argued that it is especially characteristic of Romantic form).

Fragments and Cycles

The most remarkable feature of Clara Schumann’s song ‘Die stille Lotosblume’ (the final of the Sechs Lieder, Op. 13, from 1844, see Ex. 15.3) is its ending: a dominant seventh chord with a double ˆ9–ˆ8 and ˆ4–ˆ3 appoggiatura.10 Its second most remarkable feature is its beginning: the same dominant seventh chord, the same appoggiatura. An unusual emphasis on dominant harmony permeates the song. The opening of its vocal portion takes the form of the antecedent of a compound period: bb. 3–4 function as a basic idea that groups together with a contrasting idea into a simple (four-bar) antecedent, which is in turn complemented by a four-bar continuation phrase to form a higher-level eight-bar antecedent ending with an HC at b. 10. This eight-bar antecedent sets the first textual strophe, and when the second strophe is set to a near-identical repetition of the same antecedent (the HC at b. 18 now followed by a brief post-cadential expansion in the piano), the song starts to unfold as a simple strophic form. This impression is initially confirmed at the beginning of the third strophe, until an inspired move into the region of flat-III at b. 26 completely abandons the strophic plan. Yet even though the song’s second half is more freely organised than the first, the cadential behaviour remains constant. In the second half, too, each unit ends with an HC: the move to the flat side leads to an HC in flat-III at b. 33, and when the music moves back to the home key, it again leads to two HCs, first in the piano at b. 35, then in the voice at b. 43 (replicating the cadential formula from the original compound antecedent).

Example 15.3 Clara Schumann, ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, from Sechs Lieder, Op. 13 No. 6 (1844), bb. 1–10, 42–7

‘Die stille Lotosblume’ thus remains curiously incomplete, literally open-ended. In the same way that the dominant at the end never resolves to a tonic chord, the entire song consists of a series of antecedents that are never answered by a parallel consequent – or even a concluding authentic cadence. The form, moreover, is circular: its end is like its beginning. Applied to this song, the terms ‘beginning’ and ‘end’ are in fact already problematic. Theories of musical form consider a complete formal utterance at any level (a theme, section, or movement) to consists of a beginning, a middle, and an end.11 Each of those temporal functions is expressed by a specific combination of formal and harmonic characteristics. At the level of the theme, for instance, a beginning takes the form of a basic idea with tonic-prolongation, whereas an ending takes the form of a cadential progression. In that sense, the song’s first two bars are not a beginning, and its last two not an ending. And whereas one could argue that the song’s real beginning is at b. 3, with the first two bars as an introductory or anacrustic gesture, the sense of openness at the end is irreducible: an HC is a possible ending function at the intermediate level, but not at the end of a complete form.

Forms that, like ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, are left intentionally incomplete are called fragments, and they constitute one of the most characteristic ways in which Romantic composers treated form differently than did their classical counterparts.12 In addition to incompleteness, the term fragment also implies a larger whole to which the fragment belongs (and of which it is, literally, a fragment). The openness of a fragment can be a way to create connections between different songs, pieces, or movements that belong together. Because of its inherent incompleteness, the fragment makes sense only in the context of the larger whole. When that is the case, the level of coherence between those songs, pieces, and movements transcends that of the mere ‘collection’: they form a cycle.

In ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, the relation between the fragment and the whole of the song set it concludes is not so clear. To be sure, the song immediately before ends on a tonic chord in the same key, to which the dominant at the beginning orients itself; in context, the opening bars sound significantly less puzzling than in isolation. But since ‘Die schöne Lotosblume’ comes at the end of the set, the dominant in the final bars does not obviously establish a connection to a larger whole – or, if it does, then it would be to a whole that is abstract or implied rather than concrete.13

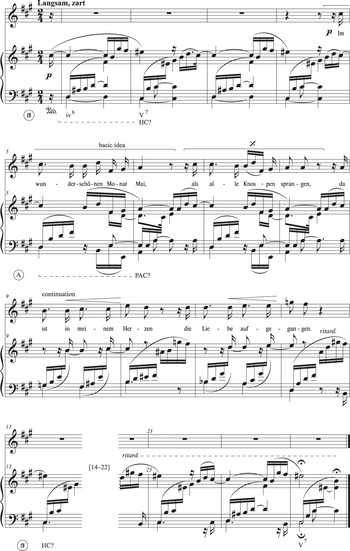

In what is perhaps the most cited example of a Romantic fragment in music, ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’ (composed in 1840 by Clara Schumann’s husband Robert as the opening of the song cycle Dichterliebe, Op. 48), the formal openness more obviously serves to connect the individual song to the cycle as a whole. Like ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’ ends on a dominant seventh chord, and as in that song, the last two bars are identical to the first (see Ex. 15.4). And here as well, those first two bars are, form-functionally speaking, not a beginning. Moreover, they cannot be explained as an introduction either. Considered by themselves, they constitute a half-cadential gesture (iv6–V7 in F sharp minor), and therefore an (intermediary) ending function, that is immediately repeated. As the music theorist Nathan Martin has shown, that apparent cadential function is recast as a continuation when in bb. 5–6 the piano produces a stronger cadential gesture, a PAC in A major, using the same motivic material.14 At the same time, b. 5 clearly stands out as a new beginning, if only because this is where the voice enters. From this perspective, bb. 5–6 form a basic idea that is immediately repeated and then gives way to a continuation, thus suggesting a sentence. Yet at the end of the continuation that sentence slips back into F sharp minor and into a return of the opening four bars, which now effectively function as the half-cadential conclusion to the theme. This entire process then starts over, so that the song is circular on two levels: the individual strophe and the song as a whole.

Example 15.4 Robert Schumann, ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’, from Dichterliebe, Op. 48 No. 1 (1840), bb. 1–13, 23–5

The song’s formal openness is compounded by a fundamental (and much commented upon) ambiguity between the keys of F sharp minor and A major – the key on the dominant of which the song begins and ends, and the key of the song’s only (but, as we saw, qualified) PACs. The combination of formal openness and tonal ambiguity contributes to the almost seamless connection between the cycle’s opening song and the next, ‘Aus meinen Thränen’. On the surface of it, the second song is in A major. Upon closer inspection, however, its opening wavers between the two keys that were at play in the first song: in isolation, it is impossible to tell whether the first three harmonies prolong A or F sharp. And coming from the dominant at the end of the first song, the song’s beginning arguably sounds like (or at least can be heard in) F sharp minor; only at the end of b. 1 does it settle in A major.

Tonal instability does not end here: at b. 12, the second song seems temporarily to lapse back into F sharp, with the HC at the end of the contrasting B section reconnecting with the cadence at the end of the first song. And while the beginning of the A′ section (bb. 13–17) returns to A major, the tonic appears as V7 of IV. Tonicisations of vi and IV are, of course, hardly unheard of. Yet here they gain additional significance because of their connection to the surrounding songs: the HC in F sharp at b. 12 reconnects with the cadence at the end of the first song, and the tonicisation of IV in the final section in turn looks forward to the third song (‘Die Rose, die Lilie’), which is in D major. Even though ‘Aus meinen Thränen’ is formally closed – much more so, at least, than the previous two examples – it can still be considered a fragment, not only because it is so short that a performance in isolation would make little sense, but also because its internal details are intimately connected to the larger whole of which it is part.

One characteristic the songs discussed so far have in common is their small scale. They are, in addition to fragments, also miniatures: apart from the missing beginnings and endings, their basic formal structure is relatively classical but would, within the classical style, be part of a larger form rather than a complete piece or movement. This is particularly clear in ‘Aus meinen Thränen’: the song is easily recognised as quatrain (or AABA‘) form, not fundamentally different from the way in which that theme type would have appeared in a late eighteenth or early nineteenth-century composition except for a few harmonic details. But whereas there, it would have acted as a theme within larger form, here it forms the complete song.

While such miniatures (usually grouped into collections or cycles) are indeed characteristic of Romantic music, and while many fragments are indeed miniatures, it would be wrong to conclude that fragments cannot have larger proportions. Schumann’s Fourth Symphony (originally composed in 1841, here discussed in its 1851 revision) is a good counterexample. This piece is often cited as an example of a ‘cyclic’ symphony in the sense that a high number of thematic ideas and their variants recur across its various movements.15 This unusually dense thematic cyclicism, however, works in tandem with an equally uncommon degree of formal cyclicism. The first three of the symphony’s four movements are all fragments, remaining formally incomplete and thus creating an openness towards the larger whole of which they are part.

The most obviously open-ended movement is the third, which begins in D minor and ends in B flat major. Initially the movement unfolds as a standard scherzo form, with a scherzo proper (bb. 1–64), a trio (bb. 65–112), and a complete recapitulation of the scherzo (bb. 113–76). When the trio begins a second time at b. 177, this increases the dimensions of the form: instead of a ternary format, we now seem to be dealing with a five-part scherzo, in which the second appearance of the trio would normally be followed by a final recapitulation of the scherzo proper. Yet this concluding scherzo section never materialises, so that the movement as a whole remains a fragment that is connected by an eight-bar link to the slow introduction to the finale.

The slow second movement (Romanze) is a large ternary form. Its A section (bb. 1–26), itself in the form of a small ternary (a bb. 3–12, b bb. 13–22, a′ bb. 23–6) is in the tonic A minor, its contrasting B section (bb. 27–42) in the subdominant major. When the A′ section arrives in bb. 43–53, it is curtailed, preserving only the a section of the original small ternary. This in itself is hardly unusual: compressed reprises in ternary forms are common both in the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. What is noteworthy is that the A′ section is transposed up a perfect fourth, and thus starts in D minor. The result of this subdominant reprise is that the same modulation that in the original a section led away from the tonic (i.e., from A minor to E minor/major) now leads back to it (from D minor to A minor/major). From the local perspective of the slow movement, the form may therefore appear to be closed. Within the broader context of the symphony as a whole, however, the final harmony of the Romanze functions not as a concluding tonic, but as the dominant of the D minor in which the next movement begins.

The most complex fragment is the first movement. It comprises a slow introduction (bb. 1–29), a compact exposition (bb. 29–86), and a comparatively sprawling development (bb. 87–296), the end of which is signalled by the pedal point on the dominant A in bb. 285ff. The return of the tonic major that follows, however, is not accompanied by anything that comes even close to a formal recapitulation, and what little recapitulation there is is not the recapitulation that goes with the exposition from earlier in the movement. Phrase-structurally, bb. 297–337 are most reminiscent of the final stages of a subordinate theme, leading to the cadence that concludes the recapitulation that is, as such, largely missing; and the thematic material in these bars is derived not from the exposition, but from the second of two new themes that were first presented in the development (bb. 121ff. and 147ff., respectively). Only at b. 337 does motivic material from the exposition’s main theme return, now clearly with post-cadential function (i.e., as a codetta or coda). The formal openness of the first movement is answered in the finale, the exposition of which begins, paradoxically, with a recapitulatory gesture: its main theme combines a close variant of the first new theme from the first movement’s development (the one from bb. 121ff.) with the head motive of the first movement’s main theme, thus to a certain extent providing compensation for the missing recapitulation of these themes in the first movement.

***

As all these examples illustrate, Romantic form does not exist in a universe separate from classical form, but rather maintains a state of perpetual dialogue with it. Forms both small and large are, to repeat Blume’s words cited above, ‘common to both’ even if they are ‘subject … to amplification, specialization, and modification’.16 From the perspective of the music analyst, there are obvious advantages to this: if duly modified, established theories of classical form – theories that are at least somewhat familiar to most undergraduate music students – can go a long way in explaining what happens in this music. But there is also a drawback. Because theories of classical form are so readily applicable to Romantic music, the risk is to treat them as a standard – a norm – to which everything that is different (and in Romantic music, a lot is different) relates as a deviation. Yet in the context of Romantic music, that which by classical standards would be a deviation can be the norm, rather than the exception, and should be interpreted accordingly. Finding a balance between the continuing presence of classical formal types and the self-sufficiency of the Romantic style is perhaps the greatest challenge to the analyst of Romantic form.