Introduction

Applying linguistic analogies to music is inevitably a precarious activity. The idea that we can usefully characterise a composer’s musical ‘language’ is a musicological commonplace; the analogy has variously encompassed melodic style, harmony, approaches to form and genre, and expressive means and objectives, as well as more ambitious claims that music and language are somehow synonymous. Yet few commentators accept the functional synonymy of music and language uncritically. Research in the fields of musical semiotics, expression, and narrativity has not established any precise linguistic function for music; and linguistic models of musical meaning of the sort attempted by Deryck Cooke seem doomed to failure.1

This analogy is nevertheless crucial to any consideration of music and Romanticism. As Benedict Taylor makes clear in this volume’s opening chapter, a new interest in the relationship between music and literature and a belief that music can fulfil poetic, dramatic, and narrative aspirations without the need for written language are defining factors of music’s Romantic turn. These convictions rely on a complex mediation of musical and extra-musical factors. In one sense, Romantic music is marked by a retreat from extra-musical meaning: Beethoven, above all, comes to be associated with the concept of autonomy, by which is generally meant the liberation of music from textual and social dependencies and a consequent freedom to pursue its own self-reflective ambitions.2 At the same time, autonomy facilitates a perception of music as the purveyor of higher meanings: precisely because instrumental music coheres without textual support, it can convey conceptual essences without the intervention of written or spoken language. This is absolute music’s aesthetic precept: textless music accesses narrative and poetic ideas directly, without recourse to language.

This chapter offers three case studies of Romanticism’s musical ‘language’, understood as the melodic, harmonic, and formal means that composers deployed to expressive ends. The first and second case studies – melody in Beethoven and Field, and harmony from Schubert to Brahms – deal with aspects of what could, by analogy, be called Romanticism’s vocabulary and grammar, paying attention to compositional materials, the logic of their employment, and the sources from which they arise. The third – the Finale of Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 – turns to matters of form specifically to address the relationship with literature, and therefore isolates narrative as well as purely formal strategies (questions of Romantic form are addressed by Steven Vande Moortele in Chapter 15). Connecting these studies is the common theme of Romanticism’s new-found musical self-awareness. The thematic habits of Beethoven’s middle period betray a degree of overt intellectual self-reflection in excess of eighteenth-century precedent; harmonic experimentation develops alongside an emerging theoretical understanding of music’s systems as well its practices; and Schumann’s symphonic-literary sensibility is enabled by reflection on the idea of a symphony as well as its generic requirements.

Melody, Theme, and Texture

Romanticism’s attitude towards melody is characterised by contrasted, if not contradictory, tendencies. Composers accorded new importance to lyric and rhapsodic styles, emphasising a degree of freedom that went beyond classical conventions and devising novel vehicles for its expression. At the same time, they also placed a heightened value on thematic and motivic coherence, pursuing cyclical integration and developmental processes in instrumental compositions especially. To an extent, these tendencies evidence the polarised priorities of vocal and instrumental music, which Carl Dahlhaus housed under the contentious ‘style dualism’ of Rossinian opera and Beethovenian instrumental music.3 Yet this duality conceals a more nuanced reality: composers in Beethoven’s shadow found new ways of imitating vocality; and lyrically inclined genres emerged, which are impossible to classify into straightforward national schools.

That the lyric strain of Romantic melody evades simple explanation is aptly demonstrated by the development of the nocturne. Credit for its invention as an instrumental genre is invariably given to John Field, whose sixteen contributions were published between 1812 and 1836, but this origin myth masks complex circumstances: Field did not ‘invent’ the nocturne in an act of Romantic innovation. Many of the pieces he eventually published as nocturnes began life under other titles, which sometimes indicate a debt to the eighteenth-century notturno (‘serenade’) and sometimes do not (‘pastorale’, ‘romance’).4 In some cases, stand-alone nocturnes migrated from other genres entirely: the Nocturne No. 12 in G is, for example, also a slow episode in the first movement of Field’s Piano Concerto No. 7. More properly, we can see the piano nocturne as coalescing from various generic and stylistic sources. Its melody-and-accompaniment idiom derives from the high-classical singing style, crucially augmented by the pedalling technology that allowed pianists to displace the bassline from the interior texture by more than an octave.5 Vocal precedents are folded into the genre – the operatic serenade and bel canto fioritura are often cited – but in Chopin’s hands especially, the title accommodates a broad range of implied genres.6

The nocturne’s Romantic credentials, and Field’s status as its progenitor, were secured by Franz Liszt, whose preface to the first collected edition nominated the pieces as seminal for musical Romanticism. For Liszt, it was to Field’s unique sensibility that ‘we owe the first essays which feeling and revery ventured to make on the piano, to free themselves from the constraints exercised over them by the regular and official model imposed until that time on all compositions’. Before Field, ‘It was formally necessary that they should be either Sonatas or Rondos etc.; Field was the first to introduce a species which belonged to none of the established classes, and in which feeling and melody reigned alone, liberated from the fetters and encumbrances of a coercive form.’7 Liszt’s claims are hard to categorise within Dahlhaus’s dualism. Field’s style is clearly vocal, but also distant from Rossinian opera’s formulae and overt display. Liszt subsequently emphasises Field’s lyricism, thereby associating him more closely with Schubert; but there is nothing in Field that suggests poetic dependency or an anchorage in art song. And Liszt’s Field is even more distant from the instrumental style that Dahlhaus valorised in Beethoven. Field also falls outside Dahlhaus’s geographical remit, as a representative of the so-called ‘London pianoforte school’, the influence of which was both widespread and distinct from both Austro-German and Franco-Italian genealogies. Nevertheless, as a progenitor of Romanticism, Field is arguably more important than any of these precursors, since, for Liszt, it is to Field that Romanticism owes all of those genres that are specifically post-classical.

Brief comparison of Field’s Nocturne No. 1 in E flat of 1811 with the first movement of Beethoven’s ‘Tempest’ Sonata, Op. 31 No. 2 of 1801 makes clear the sheer distance between Field’s aesthetic and Beethoven’s motivic style. The first movement of the ‘Tempest’ has become an exemplar of Beethoven’s middle-period intellectualism. Dahlhaus repeatedly observed the novelty of its opening, shown in Ex. 14.1, which moves from introduction to transition without ever establishing a stable main theme.8 More recently, Janet Schmalfeldt has explained this as an example of ‘becoming’, or the retrospective reinterpretation of formal function. On first hearing, bar 21 seems to initiate a main theme, because it is the first unequivocal downbeat, which establishes a root-position tonic. By bar 41, however, it has become clear that bar 21 initiates a transition, not a theme, which means that we have to mentally revisit bars 1–21 and reinterpret them as thematic.9

Example 14.1 Beethoven, ‘Tempest’ Sonata, Op. 31 No. 2 (1801), i, bb. 1–41

Dahlhaus and Schmalfeldt consider Beethoven’s innovation here to be the creation of a dialectical formal concept, which collapses formal function into process. The material’s identity is not confirmed with its presentation; instead, Beethoven forces his listener to reconsider and discard perceptions of formal function as the music proceeds. Because we have to convert a main theme into a transition, we also have to convert an introduction into a main theme. All of this happens retrospectively and speaks to a kind of form, in which the listener is an active participant. As a result, the ‘Tempest’ transforms the formal functions of sonata form from genre markers (‘I know we are listening to a piano sonata, because I hear a main theme and transition’) into objects of conscious reflection (‘I am invited to participate in the construction of the main theme and transition as I hear them, as well as acknowledging their generic circumstances’). Both Dahlhaus and Schmalfeldt are quick to point out the parallels with contemporaneous philosophy. The notion of a consciously critical art was central to Friedrich Schlegel’s idea of the Romantic fragment; and it is easy to see resonances with Hegel’s coming-to-self-consciousness of the spirit, as narrated in the Phenomenology.10 In effect, Beethoven’s ‘Tempest’ composes the coming-to-self-consciousness of sonata form, as a musical experience that folds the form’s identity into the listener’s emerging consciousness of it.

As Dahlhaus points out, Beethoven compensates for the resulting loss of formal stability by retaining a single, concise motive across the passage (the arpeggiated figure with which the piece begins). More important than the development of this motive, however, is the new status that its formal context attains. There is an important sense in which Beethoven composes music which is about the idea of first-movement form more than it is about confirming those features that the genre requires. In Beethoven’s music, this is what autonomy means: the music’s meaning resides in what it has to say about musical composition in sonata form, in addition to its expressive and generic responsibilities.

Numerous scholars have since identified this notion of becoming as a crucial feature of Romantic music; but even cursory appraisal of Field’s Nocturne (Ex. 14.2 shows bars 1–21; Table 14.1 appraises its form) reveals its distance from both Beethovenian and classical frames of reference.11 The piece’s form is ternary, to the extent that bars 1–19 form a closed unit, which is reprised in bars 43–66, between which new music is inserted. All three of the Nocturne’s sections however culminate with perfect-cadential closure in the tonic, violating William Caplin’s precondition that classical ternary forms should conclude their contrasting middle sections half-cadentially.12 Moreover, the second section offers only limited material contrast, since it sustains the A section’s texture and loosely varies its material in V and ii. The music’s self-containment bespeaks lyricism, but the form is not strophic in a way that encourages poetic analogies, and its recursive features occasion neither variation in any strict classical sense nor simple recurrence.13

Example 14.2 Field, Nocturne No. 1 in E flat (1811), bb. 1–22

Table 14.1 Field, Nocturne No. 1, form

| Bars: | 1 | 15 | 20 | 43 | 57 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form: | A | (codetta) | B | A1 | Coda |

| Keys: | I | V→ii→I | I | ||

| Cadences: | PAC | PAC | PAC | ||

Crucially, what Field offers is in the first instance a texture, not a theme; or rather, the theme gives architectonic substance to the texture. The first few bars establish a melody-and-accompaniment division of labour, which is maintained throughout, and the left-hand triplet figuration remains consistent for the entire piece, in its rhythmic patterning and internal division into registrally disjunct bass and registrally invariant inner voices. Details of Field’s voicing are classically aberrant but have clear textural motivation. This is apparent in bar 2, where, as Ex. 14.2 shows, the alto doubles the soprano’s leading note at the octave, while clearly supplying a distinct voice. This is contrapuntally obtuse, but texturally intelligent, since the net effect, especially taken in conjunction with the pedalling, is to create a specifically resonant sonority.14 Above this, the melody trades in free, fioritura elaboration, which is not variation as such, because the accompaniment never changes, but a kind of bel canto improvisation. The results are undeniably vocal, to the extent that they resemble a cantabile topic, but Field’s germinal source of material is the instrument itself, and more specifically the fashioning of texture from sonority, and of melody from texture. To this extent, the vocal analogy is fortuitous rather than essential: the music is about the piano, not about the piano imagined as a voice.

There is an enticing dualism here, which is quite different from the dichotomy of the dramatic and the lyric usually observed between Beethoven and Schubert, or the style dualism of Beethoven and Rossini conjured by Dahlhaus. Beethoven’s germinal idea is abstract and, in a sense, pianistically indifferent: the initial arpeggio could in principle occur on any instrument. In Field’s case, the instrument’s sonority generates the material: the piece’s ‘idea’ is not the progress of a theme, but the elaboration of a texture. In this respect at least, Liszt is right to see Field’s nocturnes as the ancestors of Romanticism’s post-classical, poetic forms, but what he misses is a preoccupation with sonority, which tracks through Chopin to Fauré and Debussy, and on into the twentieth century.

Harmony and Tonality

A further, critical feature of Romanticism’s musical language is its attitude towards tonality. The very idea that harmony can be classified within an evolving tonal system is an early nineteenth-century invention. The term itself (‘tonalité’) was first coined by Alexandre Choron in 1810 in his ‘Sommaire de l’histoire de la musique’, the introduction to Volume I of his Dictionnaire historique des musicien, in order to describe the practice, originating with Monteverdi, of establishing a tonic in relation to its dominant and subdominant triads.15 The idea that music is based on an historically evolving tonal system was further elaborated in François-Joseph Fétis’s Traité complet de la théorie et de la pratique de l’harmonie of 1844. Fétis interpreted musical history in terms of tonality’s evolution, splitting the period from the Renaissance to his own time into four tonal ‘orders’, from the ‘unitonic’, non-modulatory tonality of the sixteenth century through the ‘transitonic’ tonality established by Monteverdi – which replaces the modal system with modulation between diatonic keys – and the eighteenth century’s ‘pluritonic’ elision of major and minor modes, to the nineteenth century’s ‘omnitonic’ order, which ‘frustrates’ tonal unity by permitting complete chromatic modulation.16

This theoretical self-consciousness supplies both a context and a prerequisite for harmonic diversity. Romanticism’s most overt innovations involve the unseating of classical conventions, above all the cadence’s syntactic primacy. William Caplin has noted Romantic composers’ tendency to favour non-cadential phrase endings, usually by replacing classical cadential progressions with what he terms ‘prolongational closure’.17 Ex. 14.3 shows an instance in the ‘Valse Allemande’ from Schumann’s Carnaval . The excerpt is in rounded binary form, but neither the A nor A1 sections end with a conventional cadence. Bars 5–8 are weakly cadential at best, comprising a V43–V7–I progression in the dominant, the security of which is immediately undone by the alto D♭ in bar 8. The end of A1 secures the tonic but is not cadential at all. Schumann alights on IV63 in bar 21 as a potential predominant, but before V is attained in bar 23, the music passes through three potential chromatic predominants – an Italian augmented sixth, an inversion of vii/V, and V7/V – only the last of which resolves in an orthodox way (to V). Having reached V, Schumann then progresses to I via a bass arpeggiation, thereby undermining any sense of cadential root motion. There is closure on the tonic, but no authentic-cadential confirmation.

Example 14.3 Robert Schumann, ‘Valse Allemande’, from Carnaval, Op. 9 (1835)

Schubert’s ‘Ihr Bild’ from Schwanengesang (Ex. 14.4) adjusts other aspects of classical practice. The mixture of major and minor modes penetrates the music to an extent that unseats classical orthodoxy, even though Schubert’s harmonic palette is overwhelmingly classical in its details. Modal mixture emerges in the interaction of cadential and pre-cadential harmony. In the setting of stanza 1 in bars 1–12, Schubert slips between an initially established B flat minor and a B flat major secured by a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in bars 11–12, a setting that recurs verbatim in the final stanza, thereby securing a ternary design, in which stanzas 1 and 3 enfold a middle section in G flat, which sets stanza 2. The pianist’s postlude however undoes the voice’s ostensibly decisive tonic-major PAC, completed by bar 34, by returning to B flat minor, in which mode the song concludes. The methods of prolongation and cadence Schubert employs are wholly classical, but the balance of modes is such that arbitrating between them becomes virtually impossible. If we think that B flat minor is the tonic, then we have to confront the problem that no structural cadence establishes it. If we think B flat major is the tonic, then we need to discount the fact that the song neither begins nor ends in this mode. The frame qualifies the cadences, and the cadences qualify the frame.

Example 14.4 Schubert, ‘Ihr Bild’, from Schwanengesang, D. 957 (1828)

The return to B flat minor for stanza 3 in bars 23–4 moreover discloses a harmonic detail, boxed in Ex. 14.4, which clearly signals Schubert’s post-classical intent. Schubert deploys a chord in bar 23 which has the pitch content of a German augmented sixth but is arranged with B♭ rather than G♭ in the bass, creating an augmented fourth chord defined by the interval between B♭ and E♮. In orthodox circumstances, this chord would resolve onto a cadential 6–4, which then corrects to V. Schubert instead holds the B♭ bass as a common tone and propels the E♮ upwards to F, producing a strongly implied root-position triad of B flat minor, which, however, contains no third. No dominant of B flat minor is subsequently forthcoming: stanza 3 reprises the music of stanza 1 directly in the minor mode. Schubert’s innovation here is not the sonority itself, but its contextual treatment: the augmented sixth is rethought and so, in consequence, is the retransitional approach to the tonic.

By the mid-century, the reconception of classical means had annexed other sonorities. The opening of Liszt’s Faust-Symphonie, first performed in 1857 and quoted in Ex. 14.5, famously liberates the augmented triad from its diatonic constraints. The initial twelve-note theme, comprising the statement and three descending semitonal transpositions of an augmented triad, is, like Schubert’s augmented fourth, radical not because of the triad’s presence, but because of its de-contextualisation. In common-practice usage, augmented triads are formed from the motion either of a chromatic passing note or a suspension, which temporarily generates a triad comprising two major thirds. Ex. 14.6 shows an instance in Mendelssohn’s Lied ohne Worte, Op. 30 No. 3. This is really a progression from V42/ii to ii6 in E, but Mendelssohn delays the leading note’s resolution, creating a downbeat suspension, which temporarily emphasises the augmented triad A-C♯-E♯, before the E♯ moves correctly to its note of resolution, F♯. This is not a triad in its own right, but a sonority formed contrapuntally from the motion of parts between two functional chords.

Example 14.6 Mendelssohn, Lied ohne Worte, Op. 30 No. 3 (1834), bb. 7–11

Liszt’s augmented triads, however, have no diatonic anchorage. They descend in stepwise sequence; and at no point is any pitch revealed as a passing note or suspension in search of resolution towards a major or minor triad. More than this, one particular augmented triad – that founded on E, on which the opening material comes to rest in bar 2 – is effectively the centre of gravity for the introduction’s first thematic paragraph. As Ex. 14.5 reveals, this triad is prolonged, with elaboration, from bar 2 to bar 11, as a simultaneity until bar 7, and then in descending arpeggiation thereafter. Liszt in effect makes a dissonance (the augmented triad) perform a role analogous to the tonic triad in the diatonic common practice.18

The diversity of practices after Faust is clarified by comparison of passages from Brahms’s Violin Sonata, Op. 100, and Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, completed in 1887 and 1872, respectively. Opus 100’s first theme (Ex. 14.7) confirms Dahlhaus’s perception that Brahms ‘enriches’ rather than endangers diatonic tonality.19 A major’s tonic status is never in dispute and none of the progressions employed would be out of place in a Mozart sonata. And yet the theme’s idiom is incomprehensible in late-classical terms. Its opening statement, bars 1–5, initiates an entirely orthodox ascending step progression from I to ii; V/ii anticipates a B-minor harmony, which duly arrives at the start of the response phrase in bar 6. Bar 7 finds B minor’s Neapolitan, C major; by bar 8, this has been treated pivotally as IV of G, which is confirmed via its V42 on the last beat of bar 7. The step progression, which at the start was mobilised to produce a I–ii progression, now returns us to A, V of which is attained in bars 9–10. Within ten bars, and without ever threatening A’s stability, Brahms has moved through an interior region of G major which has no close diatonic connection to the tonic.

Example 14.7 Brahms, Violin Sonata in A major, Op. 100 (1886), i, bb. 1–10

The Coronation Scene from Boris Godunov’s Prologue contrasts with Brahms in almost every respect. The entire orchestral introduction, totalling some thirty-eight bars, consists of the alternation of two chords, quoted in Ex. 14.8. According to the notation, these chords are V42 of G, or at least a D dominant seventh chord in its last inversion, and a German augmented sixth chord in C major, spelled with its third in the bass, that is, as an augmented fourth chord. With effort, we could hear this progression in C major, as the alternation of a secondary dominant and an augmented sixth; but nothing in the progression’s context supports this reading. The harmonic oscillation robs both chords of their functional identities; after a while, any expectation that V42/V should resolve to V disperses, as does the perception that the augmented fourth should resolve to V64 in C.

Example 14.8 Mussorgsky, Coronation Scene from Boris Godunov (1872), bb. 1–45

Two factors cause the progression to cohere in the absence of a functional milieu. The first is the common-tone C, which sits beneath the entire passage as a pedal point. The second is the two chords’ membership of the same octatonic collection; as Ex. 14.8 explains, although tritonally distant – their roots are D and A♭ – they both derive from octatonic Collection II, applying Pieter van den Toorn’s terminology, and together comprise a six-note subset of the Collection.20 In a sense, we do not hear this music as diatonically tonal at all, but as projecting a single sonority over time, which is a six-note octatonic surrogate. The music breaks out of this oscillation at bar 40 and becomes wholly triadic, but the sense of diatonic indeterminacy persists, because the progression (E major, C major, A major, E major) favours third relations over any attempt to confirm a tonic via V–I motion.

Taken together, the habits of these composers instantiate many of Romanticism’s major harmonic innovations. Schubert merges major and minor modes; Schubert, Liszt, and Mussorgsky decontextualise common-practice sonorities; Liszt and Mussorgsky liberate dissonances (the augmented triad and the dominant seventh) from tonal functionality; Liszt and Mussorgsky seek alternative foundations for triadic harmony (octatonic and hexatonic); and Brahms exploits diatonic harmony’s multivalence to create chromatic relationships. This new harmonic language is of course also aesthetic, feeding the nineteenth century’s appetite for poetic and programmatic representation and its concern for sonority over functionality. Like Beethoven’s motives and Field’s textures, it instantiates a strikingly post-classical self-reflective musical consciousness, which in this case is a consciousness of tonal harmony as a system subject to historical change.

Form and Narrative

Romanticism’s formal and tonal self-consciousness merges with its literary aspirations in the adaptation of classical forms and genres to poetic and narrative ends. This is especially clear in the development of programme music, most obviously the programme symphonies of Berlioz, which reimagine classical precedents in order to portray the progress of a central protagonist, and Liszt’s symphonic poems, in which he professed to subordinate classical form to the conveyance of a poetic idea.21 Literature’s influence is, however, more pervasive than this: the idea that classical forms could function in analogy with literary or dramatic narratives is, for example, widespread in nineteenth-century symphonies, which nevertheless shun overt programmatic intent. The literary ambitions Schumann nursed for his instrumental forms are especially well documented; as John Daverio argues, the single factor relating all of his output, from the piano cycles of the 1830s to the Faust music and the ‘Rhenish’ Symphony in the 1850s, is ‘the notion that music should be imbued with the same intellectual substance as literature’.22 Daverio sees this mentality emerging in the Papillons of 1831, which rethink the piano cycle as a vehicle for expressing aspects of Jean-Paul Richter’s novel Flegeljahre. As Daverio explains: ‘Papillons shows us a young composer in the process of construing music as literature.’23

In Schumann’s Symphony No. 2, composed in 1845, poetic and narrative impulses jostle with the work’s generic inheritance, resulting in a dense web of musical and extra-musical references. The finale has attracted particular attention in this respect, prompted by its chequered reception history and the difficulty of explaining its form in terms of any one classical paradigm. Anthony Newcomb sought to restore the Symphony’s reputation by pointing out the finale’s narrative implications. For Newcomb, attempts to describe its form in terms of any one model inevitably fail, because they overlook its narrative as well as formal hybridity: ‘the mistake comes in wanting to claim that the finale is in any single form. It starts as one thing and becomes another, and this formal transformation is part of its meaning.’24

Newcomb contends that the movement’s two halves, described in Table 14.2, align with two plot archetypes as well as two possible forms. At the start, the main theme wrong-foots the narrative expectations established by the first, second, and third movements, by moving straight from the tragedy voiced by the C-minor Adagio to an uncomplicated happy ending or lieto fine in C major. Having tended increasingly towards the struggle–victory narrative currency of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, Schumann seems at the finale’s outset to have moved to an affirmation of structural security before any moment of overcoming has occurred:

Table 14.2 Schumann, Symphony No. 2, Finale, form (after Newcomb)

If the plot archetype is that of Beethoven’s Fifth – suffering finding its way to strength and health – Schumann’s beginning here may seem an unsatisfactory way of making the crucial move. To bring the strands so carefully together at the end of the third movement only to break them, it seems, with the sharp reversal that greets us at the beginning of the last is much less subtle even than Beethoven’s obvious transition from ghostly lack of vigor at the end of his third movement to triumph at the beginning of the finale.25

In Newcomb’s reading, Schumann’s strategy is to undo the lieto fine as the movement progresses, replacing it with a grand summative finale in Beethoven’s manner. The development sinks to an expressive low point in C minor, recalling the Adagio’s main theme as well as its key, after which the finale’s refrain and its associated rondo form are rejected in favour of a recapitulation and coda dwelling more substantially on the chorale introduced from bar 280, which simultaneously quotes the sixth song of Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte and the first movement of Schumann’s own Fantasie, Op. 17. As Newcomb argues: ‘This thematic replacement is paralleled by a formal and generic one. Formally, in the process of the development, rondo elements retreat into the background, and weightier sonata elements … replace them. Generically, the last movement as modest-sized lieto fine becomes the last movement as weighty, reflective summary.’26

Crucial to Newcomb’s reading is the vital role narrativity plays in grasping Schumann’s finale. It is not enough to hear a contribution to the symphony as a musical genre; we have also to hear it as a quasi-literary genre, which engages its generic history in part as a system of plot archetypes. Schumann assumes that his audience will hear the piece in this pseudo-novelistic or dramatic way: as the story of a protagonist, whose ultimate fate can be grasped as the outcome of a narrative. The quotation from An die ferne Geliebte is critical in this respect because it performs several tasks at once. By citing Beethoven, Schumann acknowledges his symphonic precedent; but the fact that his Beethovenian source is a song not a symphony connects the work to a lyric rather than a symphonic heritage, on which Newcomb does not dwell. It is telling in this respect that the Symphony’s other major precedent is Schubert ‘Great’ C major, a piece in the revival of which Schumann played a critical role. Schubert’s model is apparent across Schumann’s Symphony, being evident in the tonality itself, the first movement’s lengthy slow introduction, the focal role played by dance rhythms in the outer movements, and the presence of a minor-mode processional slow movement. The Beethovenian plot archetype to which Newcomb refers coexists with a Schubertian paradigm, the aesthetic of which is ‘lyric-epic’ rather than dramatic, as Dahlhaus says.27 Schumann’s Symphony, in other words, is both a dramatic Beethovenian symphony and a lyric-epic Schubertian symphony; it conflates these two precedents and attempts their synthesis. The quotation from An die ferne Geliebte makes this explicit: Beethoven, Schumann tells us, is a source for the lyric as well as the dramatic. A symphonic transformation of Beethoven’s song is the agent of the Symphony’s formal salvation. It is through the lyric’s intervention that the premature lieto fine is undone.

The song reference allows Schumann to address another precedent, on which Newcomb is also mute. The Symphony No. 2 has an instrumental finale, but its vocal resonances inevitably raise the spectre of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. Like Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 thirty years later, Schumann alludes to a vocal Beethovenian source in order to legitimise a purely instrumental finale. The lyric, Schumann suggests, is the means by which the instrumental symphony can transcend Beethoven’s transcendence of the instrumental in his Ninth. At a single stroke, Schumann fuses Beethovenian and Schubertian precedents in a strategy that also confirms the instrumental symphony’s aesthetic legitimacy. This manoeuvre is confirmed in bars 544–51 in the coda, where, as Douglass Seaton notes, the falling thirds with which Beethoven twice sets ‘alle Menschen’ towards the end of the Ninth’s finale are retrieved as purely instrumental material.28

Conclusions

Of course, Romanticism’s heightened awareness of means and meaning is attended by broader historical discourses, which it is now commonplace to treat with scepticism, if not outright condemnation. Schoenberg’s argument for the historical necessity of atonality is perhaps their most well-known outcome. Its problematic Hegelianism has long been acknowledged: Richard Taruskin dismisses it as a kind of myth-making, in which ‘ontogeny’ (the development of Schoenberg’s musical style) is mistaken for ‘phylogeny’ (the development of Western music in general).29 More controversial still in light of recent decolonial scholarship is the intersection of music and race in nineteenth-century discourse. Fétis’s tonal theory was, for example, partnered with a conception of history which qualitatively differentiated musical practices according to ‘innate’ racial capacities. By this argument, European music emerged as superior, thanks to the superior cranial and mental capacities of ‘Aryan’ peoples.30 The Romantic tendency to historicise and taxonomise music in a racially hierarchical way supplies an epistemic context in which accelerating experimentation with music’s ‘language’ takes place. As Gary Tomlinson has stressed, this context is ultimately grounded in Europe’s developing tendency to perceive its culture and polity as ‘unique and superior’, a self-perception that also underwrote its burgeoning colonialism.31

Respectively problematic and repugnant as these modes of thought now seem, the wholesale critique of Romantic music on decolonial grounds is hard to sustain, because its cultural diversity resists classification under a monolithic notion of imperialism. The Bonn into which Beethoven was born was an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, a loose polity at best, which had dissolved by the time of Beethoven’s death in 1827 in Vienna, itself the capital of a wholly European empire that had little in common with the colonial trading empires of Britain, France, and the Netherlands. The duress of French imperialism was a recurrent feature of Beethoven’s adult life. The threat of French invasion hung over Bonn in 1792, when Beethoven left for Vienna, and the city was incorporated into the First French Empire in 1794; Vienna was twice captured by Napoleon while Beethoven lived there, in 1805 and 1809. Field, in contrast, was born in Dublin in 1782, during a period of increasing parliamentary independence from England, but left Ireland for London in 1793 and London for St Petersburg in 1802, remaining in Russia until his death in 1837, by which time the Acts of Union had quashed fledgling Irish independence. There is no binding concept of ‘empire’, which contains Beethoven and Field, notwithstanding a reception history that sees Beethoven especially as the world-historical Western European composer. And it is very unclear how Field’s Anglo-Hibernian/Russian contexts and Beethoven’s Hapsburg context could be merged with that of Fétis, whose Traité was published in 1844 during the period of the July Monarchy in France.

Even if Beethoven, Field, Schubert, Liszt, Brahms, Mussorgsky, and Schumann could all be ramified within an encompassing imperialism, an awareness of this context does not help us to decode the particularity of Romanticism’s musical languages, because the connections between ideology and technique are associative, not causative: historical research will never demonstrate that Fétis’s European supremacism or any comparable ideology motivates all Romantic harmonic, formal, or textural innovations beyond classical precedent. We can and should recognise the complicity of musical Romanticism’s discourses with colonialism where it is manifest. But the sheer diversity of Romanticism’s musical languages frustrates explanation in terms of any totalising disciplinary imperative.

‘On the whole’, Robert Schumann wrote in a review of a number of newly published sonatas in 1839, ‘it would seem that [classical] form has run its life course, and this is surely in the order of things, for we should not repeat the same things for centuries but rather have an open mind to what is new’.1 Schumann, the arch-Romantic, is presenting here in nuce his view of what a responsible composer should do: something ‘new’. In doing so, he pitches the Romantic (the ‘new’) against the classical (‘the same things’ that should not be repeated forever), casting the Romantic as non-classical, perhaps even as anti-classical. This familiar rhetoric is common amongst Schumann’s contemporaries; about a decade and a half later, for instance, Liszt would similarly insist on ‘new forms for new ideas, new skins for new wine’.2

This anti-classical rhetoric, however, contrasts starkly with what actually happens in Romantic music, including Schumann’s and (at least until 1860) even Liszt’s. Much of what composers wrote between, say, 1820 and 1890 shows a surprisingly high level of continuity with the formal language of earlier generations. One wouldn’t want to go so far as to claim, with the mid-twentieth-century German musicologist Friedrich Blume, that classicism and Romanticism are ‘no[t] discernible styles’, but ‘just two aspects of one and the same musical phenomenon’; when taken literally this verges on the nonsensical – there obviously are stylistic differences between classical and Romantic music.3 Yet when Blume later elaborates that ‘genres and forms are common to both and subject only to amplification, specialization, and modification’, then that opens a much more nuanced perspective.4 The picture of Romantic music that comes into focus here is of something that is not anti-classical, but post-classical: rather than abandoning what existed before, it engages in a creative dialogue with the classical tradition, especially the one often associated with the works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.

When it comes specifically to musical form, classical formal types by and large survive throughout the nineteenth century. This applies to both the large and the smaller scale – from the form of an entire movement to the internal organisation of one of its themes. In this sense, the musical forms of Romanticism are often the same as those of classicism: sonata form or sonata-rondo, small ternary or sentence, and so on. Those same forms are, however, treated differently in the nineteenth century than they were in the late eighteenth century – and, in fact, treated differently at different times and places in the nineteenth century as well. Indeed, although Romantic form obviously is a nineteenth-century phenomenon, it would be wrong to equate it with nineteenth-century form as such. For the purposes of this chapter, Romantic form is understood narrowly as a set of practices that is especially prevalent in the works of a group of composers working in Germany between 1825 and 1850, commonly termed the ‘Romantic Generation’, and that survives in the music of selected composers until the final years of the century. Formal practices at other times and places in the nineteenth century (for instance in primo ottocento Italian opera) are often very different from the ones described here. Using examples drawn from vocal and instrumental works by five different composers (in chronological order: Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Richard Wagner, Clara Schumann, and Antonín Dvořák), this chapter explores some of these typically Romantic formal tendencies as well as the ways they relate to theoretical models that have been developed for classical music. The chapter is organised in two sections. The first addresses matters of formal syntax, that is, the construction and interrelation of musical phrases, under the rubric ‘Proliferation, Expansion, and Form as Process’; the second (‘Fragments and Cycles’) explores issues of formal incompleteness as well as connections that go beyond the single-movement level.

Proliferation, Expansion, and Form as Process

When looking closely at Romantic music, the analyst with a working knowledge of recent theories of classical form will find that many of its building blocks are similar to those in the music of earlier composers.5 This is true for all levels of musical form. For two- or four-bar units no less than for passages of several dozen bars long, it is often immediately obvious what their formal function is – their role in the larger form, for example the basic idea of a sentence, or the subordinate theme of a sonata-form exposition. The way in which different levels of form are related in Romantic music, however, can be quite different from what one finds in classical form.

One way this manifests itself is in more complex thematic structures. An instructive (even though perhaps unexpected) example of a Romantic theme comes from the fast portion of the Dutchman’s aria ‘Die Frist ist um’ from Wagner’s ‘Romantic opera’ Der fliegende Holländer (1840–1, see Ex. 15.1). The theme begins with an eight-bar sentence that could hardly be clearer in its internal organisation (even though its tonal organisation may seem quite outlandish): a two-bar basic idea and its repetition, together prolonging tonic harmony, followed by four bars of continuation (with contrasting material and a faster harmonic rhythm) that lead to a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the dominant minor. In the next eight bars, this sentence is restated, now with its continuation modified so that it modulates to flat-V. In classical form, the only common situation in which a modulating sentence is combined with its parallel restatement is in a compound period, where the former, leading to a weaker cadence (usually in or on the dominant), functions as an antecedent and the latter, leading to a stronger cadence, as a consequent. But such a reading is difficult to support here: the cadence in the dominant at b. 16 is in the minor mode, thus resisting automatic reinterpretation as a half cadence (HC) in the tonic, and the consequent, rather than returning to the home key, moves even farther away from it. Instead, the two parallel sentences function as the presentation of a much larger overarching sentence. The following sixteen bars indeed take the form of a continuation, starting with a repeated four-bar fragment and closing with a four-bar cadential unit (note the cadential progression V6/iv – iv – V7 – i) that is also repeated and leads to a PAC in the supertonic. Echoing the internal formal structure of each of the two halves of the presentation, this continuation can itself be heard as loosely sentential, with its first eight bars taking the place of a presentation and the next eight as a double continuation.

Example 15.1 Wagner, ‘Die Frist ist um’, from Der fliegende Holländer, Act 1 (1840–1), bb. 1–34

What this analysis shows is that there is little in this theme at the two-, four-, or eight-bar level that we cannot accurately describe with a concept familiar from classical form, and that those concepts are readily applicable with only minimal modifications. The larger constellations in which those building blocks appear, however, are different. They illustrate a mode of formal organisation characteristic of much Romantic music and for which Julian Horton has coined the term ‘proliferation’.6 Units of the length of a simple classical theme (i.e., of approximately eight bars in length) are nested within relatively long and hierarchically complex thematic units. In Wagner’s theme, the eight-bar sentence appears at the lowest level of formal organisation. It is not the whole theme (as in a simple sentence); it is not at the level of the antecedent and consequent (as in a compound period); it is at the level of the basic idea – that is, what in classical practice is the two-bar level. This degree of hierarchical complexity is virtually non-existent in classical music. And the form-functional proliferation that leads to the hierarchical complexity is itself a form of expansion: a technique used to generate larger structures. In one respect Wagner’s theme is somewhat atypical. In spite of its expansion and hierarchical complexity, it maintains a classical balance in its internal proportions, so that there is something architectonic about it. On the basis of its first building block (the opening eight-bar sentence), one can accurately predict the length of the entire thirty-two-bar theme, just like in a textbook classical sentence.

More often than not, expansion in Romantic music distorts a theme’s internal proportions. An example of what this can look like is the finale of Mendelssohn’s Piano Sonata in E major, Op. 6 (1826). This movement juxtaposes classical and Romantic modes of formal organisation with almost didactic clarity. The exposition stands out for its formal transparency. Both its interthematic layout and its cadential structure could hardly be more straightforward: main theme in bb. 1–16 concluding with a PAC in the tonic; modulating transition (bb. 16–38) leading to an HC in v; subordinate theme group in bb. 39–69 ending with a PAC in V, codetta turning into a link to the development (the exposition is not repeated) in bb. 69–76. The recapitulation, by contrast, is much more formally adventurous. Rather than by and large replicating the exposition’s modular succession, it thoroughly recomposes it. This recomposition itself as well as the specific techniques Mendelssohn uses are highly characteristic of Romantic form.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the recapitulation’s subordinate theme. In the exposition, the subordinate theme group consisted of two distinct thematic units: a highly regular compound period concluding with a PAC (bb. 39–54) and its repetition, structurally identical but with the right and left hands exchanging roles (bb. 55–69). In the recapitulation, by contrast, there is only a single, but hugely expanded, subordinate theme. At b. 154, the compound period from bb. 39–54 returns, with one crucial difference: in the very last instant, the PAC that concluded the theme in the exposition is evaded (note the telltale V42–I6 in bb. 169–70). This evaded cadence (EC) launches a process of expansion that postpones the eventual arrival of the PAC by no fewer than seventy-three bars all the way to b. 243.

The expansion happens in several steps, shown in Ex. 15.2. The EC at b. 170 is immediately followed by two renewed approaches to the cadence. The first (bb. 170–3) is swift but abandons the cadential progression before ever reaching the required dominant in root position. The second (bb. 174–86) proceeds in broader strokes and does lead to a PAC. As if to reinforce the arrival of the cadence, the progression leading up to it is immediately repeated. Yet the repetition instead undoes the closure that was previously achieved when the expected PAC is evaded at b. 190. The next attempt at a cadence (now using material derived from the main theme) does not lead to a PAC either, but to a deceptive cadence (DC, b. 199). The DC is elided with a full-on return of the main theme that culminates in a very long and promising expanded dominant at b. 206. Instead of resolving to the tonic, however, the dominant goes into overdrive (note the change in time signature and tempo at b. 217) before losing steam. Only the unexpected return of the main theme from the first movement leads to a successful cadence, first an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC; b. 232), then a PAC (b. 243).7

Example 15.2 Mendelssohn, Piano Sonata in E major, Op. 6 (1826), iv, cadential approaches between bb. 167 and 243

The cadence at b. 243 is the end point of the thematic process that started at b. 155. The subordinate theme in Mendelssohn’s recapitulation is thus considerably longer than expected – both in comparison to the original subordinate theme from the exposition, and measured against the dimensions the beginning of the subordinate theme in the recapitulation suggest. In contrast to Wagner’s theme, it is impossible to predict how long it will be; rather than architectonic, the expansion in Mendelssohn’s theme presents itself as a process that unfolds over time. Step by step, the theme grows longer, before the listener’s ear, as it were.

It would be too simple to call all of the music between bb. 155 and 243 a subordinate theme, however. Especially the change in tempo and metre, as well as the return of material from the first movement, are distinct features of a coda. Yet the structural position of a coda is, by definition, post-cadential. It comes ‘after the end’, when the recapitulation, and with it the sonata form as a whole, has achieved structural closure by means of a PAC in the home key at the end of the subordinate theme. What is remarkable about the end of Mendelssohn’s movement is that the coda begins before the subordinate theme has ended; both functions, which normally appear consecutively, temporarily overlap. The technical term for this is ‘formal fusion’: subordinate theme and coda are fused together within one formal unit, without it being possible to determine where one ends and the other begins. A listener attuned to formal functions may perceive this fusion as a gradual transformation from one function to another, a ‘process of becoming’, to use the phrase coined by Janet Schmalfeldt.8

Proliferation, expansion, and processual form remain important characteristics of Romantic form throughout the nineteenth century. The procedures used in the subordinate theme in the first-movement recapitulation of Dvořák’s Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81 (1888) are strikingly similar to the ones Mendelssohn used more than half a century before. The subordinate theme begins with a large-scale antecedent in bb. 335–52 (this unit is also another example of proliferation, since it consists of two smaller parallel phrases that each have the structure of an antecedent). At b. 353, the large-scale antecedent is answered by a parallel consequent that initially seems to be compressed, heading for a PAC already at b. 356. The anticipated cadence is, however, evaded, and only materialises thirty-five bars later, at b. 391 (the PAC in the piano is covered by the first violin). Yet being in the submediant rather than the tonic, the cadence at b. 391 cannot be the structural end point of the recapitulation. A PAC in the home key arrives only at b. 422, well into coda territory. A process that would normally take place within the recapitulation (the attainment of structural closure) thus spills over into the coda. Like in the Mendelssohn movement, the recapitulation and coda are fused.

A difference between Mendelssohn’s and Dvořák’s movements is that in the latter, expansion is not limited to the recapitulation, but plays a role in the exposition as well, most notably in the main theme. After a two-bar introductory vamp, the exposition begins with a broadly proportioned periodic hybrid (compound basic idea+continuation) leading to a PAC at b. 17. The sudden changes in thematic-motivic content, dynamics, mode, and texture at the moment the cadence arrives all suggest the beginning of a transition. This impression is confirmed when an HC in the dominant arrives at b. 37, followed by a standing on the dominant and a medial caesura; it is not hard to imagine how the unison caesura-fill in the piano right hand could have served as an extended pickup to a subordinate theme in the dominant around b. 47. But this is not what happens. Instead the music makes a volte-face, turning the tonic of the dominant back into the dominant of the tonic and leading, via a dreamy transformation of the opening theme, to a full restatement of bb. 3–17. Like the one at b. 17, the PAC at b. 75 is elided with a transition (again there is a change of mode, texture, thematic-motivic content, and, to an extent, dynamics) that first leads to an HC in the tonic and then, in the last instant, to an HC in iii, the key in which the subordinate theme finally enters at b. 93.

The first ninety-two bars of Dvořák’s exposition are an example of the specific type of processual form that Schmalfeldt calls ‘retrospective reinterpretation’: the listener who initially interpreted the unit starting at b. 17 as a transition is forced to reinterpret that same unit as part of a complex main theme when it is not followed by a subordinate theme but by a return of the opening melody. Like in the subordinate theme, the scope of the form is enlarged before the listener’s ears, in real time. The initial impression is that of a modestly sized main theme, and a ‘sonata-form clock’ – the speed at which we move through the different way stations along the sonata-form trajectory – that is ticking fast.9 The reinterpretation of the seeming transition turns the clock back, as it were: we are not yet where we thought we were, and the main theme group is much larger than we initially thought it was. The expansion thus emphatically takes the form of a process that plays out over time, and that is difficult to capture in a schematic overview (this is true of much music, but it has been argued that it is especially characteristic of Romantic form).

Fragments and Cycles

The most remarkable feature of Clara Schumann’s song ‘Die stille Lotosblume’ (the final of the Sechs Lieder, Op. 13, from 1844, see Ex. 15.3) is its ending: a dominant seventh chord with a double ˆ9–ˆ8 and ˆ4–ˆ3 appoggiatura.10 Its second most remarkable feature is its beginning: the same dominant seventh chord, the same appoggiatura. An unusual emphasis on dominant harmony permeates the song. The opening of its vocal portion takes the form of the antecedent of a compound period: bb. 3–4 function as a basic idea that groups together with a contrasting idea into a simple (four-bar) antecedent, which is in turn complemented by a four-bar continuation phrase to form a higher-level eight-bar antecedent ending with an HC at b. 10. This eight-bar antecedent sets the first textual strophe, and when the second strophe is set to a near-identical repetition of the same antecedent (the HC at b. 18 now followed by a brief post-cadential expansion in the piano), the song starts to unfold as a simple strophic form. This impression is initially confirmed at the beginning of the third strophe, until an inspired move into the region of flat-III at b. 26 completely abandons the strophic plan. Yet even though the song’s second half is more freely organised than the first, the cadential behaviour remains constant. In the second half, too, each unit ends with an HC: the move to the flat side leads to an HC in flat-III at b. 33, and when the music moves back to the home key, it again leads to two HCs, first in the piano at b. 35, then in the voice at b. 43 (replicating the cadential formula from the original compound antecedent).

Example 15.3 Clara Schumann, ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, from Sechs Lieder, Op. 13 No. 6 (1844), bb. 1–10, 42–7

‘Die stille Lotosblume’ thus remains curiously incomplete, literally open-ended. In the same way that the dominant at the end never resolves to a tonic chord, the entire song consists of a series of antecedents that are never answered by a parallel consequent – or even a concluding authentic cadence. The form, moreover, is circular: its end is like its beginning. Applied to this song, the terms ‘beginning’ and ‘end’ are in fact already problematic. Theories of musical form consider a complete formal utterance at any level (a theme, section, or movement) to consists of a beginning, a middle, and an end.11 Each of those temporal functions is expressed by a specific combination of formal and harmonic characteristics. At the level of the theme, for instance, a beginning takes the form of a basic idea with tonic-prolongation, whereas an ending takes the form of a cadential progression. In that sense, the song’s first two bars are not a beginning, and its last two not an ending. And whereas one could argue that the song’s real beginning is at b. 3, with the first two bars as an introductory or anacrustic gesture, the sense of openness at the end is irreducible: an HC is a possible ending function at the intermediate level, but not at the end of a complete form.

Forms that, like ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, are left intentionally incomplete are called fragments, and they constitute one of the most characteristic ways in which Romantic composers treated form differently than did their classical counterparts.12 In addition to incompleteness, the term fragment also implies a larger whole to which the fragment belongs (and of which it is, literally, a fragment). The openness of a fragment can be a way to create connections between different songs, pieces, or movements that belong together. Because of its inherent incompleteness, the fragment makes sense only in the context of the larger whole. When that is the case, the level of coherence between those songs, pieces, and movements transcends that of the mere ‘collection’: they form a cycle.

In ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, the relation between the fragment and the whole of the song set it concludes is not so clear. To be sure, the song immediately before ends on a tonic chord in the same key, to which the dominant at the beginning orients itself; in context, the opening bars sound significantly less puzzling than in isolation. But since ‘Die schöne Lotosblume’ comes at the end of the set, the dominant in the final bars does not obviously establish a connection to a larger whole – or, if it does, then it would be to a whole that is abstract or implied rather than concrete.13

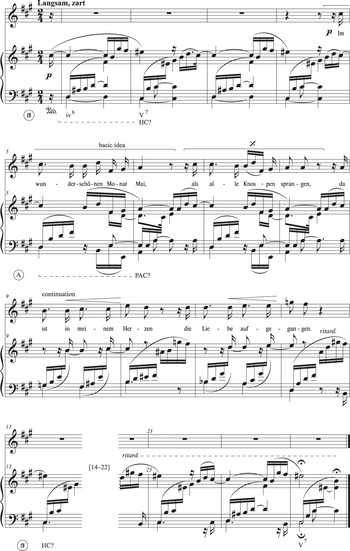

In what is perhaps the most cited example of a Romantic fragment in music, ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’ (composed in 1840 by Clara Schumann’s husband Robert as the opening of the song cycle Dichterliebe, Op. 48), the formal openness more obviously serves to connect the individual song to the cycle as a whole. Like ‘Die stille Lotosblume’, ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’ ends on a dominant seventh chord, and as in that song, the last two bars are identical to the first (see Ex. 15.4). And here as well, those first two bars are, form-functionally speaking, not a beginning. Moreover, they cannot be explained as an introduction either. Considered by themselves, they constitute a half-cadential gesture (iv6–V7 in F sharp minor), and therefore an (intermediary) ending function, that is immediately repeated. As the music theorist Nathan Martin has shown, that apparent cadential function is recast as a continuation when in bb. 5–6 the piano produces a stronger cadential gesture, a PAC in A major, using the same motivic material.14 At the same time, b. 5 clearly stands out as a new beginning, if only because this is where the voice enters. From this perspective, bb. 5–6 form a basic idea that is immediately repeated and then gives way to a continuation, thus suggesting a sentence. Yet at the end of the continuation that sentence slips back into F sharp minor and into a return of the opening four bars, which now effectively function as the half-cadential conclusion to the theme. This entire process then starts over, so that the song is circular on two levels: the individual strophe and the song as a whole.

Example 15.4 Robert Schumann, ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’, from Dichterliebe, Op. 48 No. 1 (1840), bb. 1–13, 23–5

The song’s formal openness is compounded by a fundamental (and much commented upon) ambiguity between the keys of F sharp minor and A major – the key on the dominant of which the song begins and ends, and the key of the song’s only (but, as we saw, qualified) PACs. The combination of formal openness and tonal ambiguity contributes to the almost seamless connection between the cycle’s opening song and the next, ‘Aus meinen Thränen’. On the surface of it, the second song is in A major. Upon closer inspection, however, its opening wavers between the two keys that were at play in the first song: in isolation, it is impossible to tell whether the first three harmonies prolong A or F sharp. And coming from the dominant at the end of the first song, the song’s beginning arguably sounds like (or at least can be heard in) F sharp minor; only at the end of b. 1 does it settle in A major.

Tonal instability does not end here: at b. 12, the second song seems temporarily to lapse back into F sharp, with the HC at the end of the contrasting B section reconnecting with the cadence at the end of the first song. And while the beginning of the A′ section (bb. 13–17) returns to A major, the tonic appears as V7 of IV. Tonicisations of vi and IV are, of course, hardly unheard of. Yet here they gain additional significance because of their connection to the surrounding songs: the HC in F sharp at b. 12 reconnects with the cadence at the end of the first song, and the tonicisation of IV in the final section in turn looks forward to the third song (‘Die Rose, die Lilie’), which is in D major. Even though ‘Aus meinen Thränen’ is formally closed – much more so, at least, than the previous two examples – it can still be considered a fragment, not only because it is so short that a performance in isolation would make little sense, but also because its internal details are intimately connected to the larger whole of which it is part.

One characteristic the songs discussed so far have in common is their small scale. They are, in addition to fragments, also miniatures: apart from the missing beginnings and endings, their basic formal structure is relatively classical but would, within the classical style, be part of a larger form rather than a complete piece or movement. This is particularly clear in ‘Aus meinen Thränen’: the song is easily recognised as quatrain (or AABA‘) form, not fundamentally different from the way in which that theme type would have appeared in a late eighteenth or early nineteenth-century composition except for a few harmonic details. But whereas there, it would have acted as a theme within larger form, here it forms the complete song.

While such miniatures (usually grouped into collections or cycles) are indeed characteristic of Romantic music, and while many fragments are indeed miniatures, it would be wrong to conclude that fragments cannot have larger proportions. Schumann’s Fourth Symphony (originally composed in 1841, here discussed in its 1851 revision) is a good counterexample. This piece is often cited as an example of a ‘cyclic’ symphony in the sense that a high number of thematic ideas and their variants recur across its various movements.15 This unusually dense thematic cyclicism, however, works in tandem with an equally uncommon degree of formal cyclicism. The first three of the symphony’s four movements are all fragments, remaining formally incomplete and thus creating an openness towards the larger whole of which they are part.

The most obviously open-ended movement is the third, which begins in D minor and ends in B flat major. Initially the movement unfolds as a standard scherzo form, with a scherzo proper (bb. 1–64), a trio (bb. 65–112), and a complete recapitulation of the scherzo (bb. 113–76). When the trio begins a second time at b. 177, this increases the dimensions of the form: instead of a ternary format, we now seem to be dealing with a five-part scherzo, in which the second appearance of the trio would normally be followed by a final recapitulation of the scherzo proper. Yet this concluding scherzo section never materialises, so that the movement as a whole remains a fragment that is connected by an eight-bar link to the slow introduction to the finale.

The slow second movement (Romanze) is a large ternary form. Its A section (bb. 1–26), itself in the form of a small ternary (a bb. 3–12, b bb. 13–22, a′ bb. 23–6) is in the tonic A minor, its contrasting B section (bb. 27–42) in the subdominant major. When the A′ section arrives in bb. 43–53, it is curtailed, preserving only the a section of the original small ternary. This in itself is hardly unusual: compressed reprises in ternary forms are common both in the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. What is noteworthy is that the A′ section is transposed up a perfect fourth, and thus starts in D minor. The result of this subdominant reprise is that the same modulation that in the original a section led away from the tonic (i.e., from A minor to E minor/major) now leads back to it (from D minor to A minor/major). From the local perspective of the slow movement, the form may therefore appear to be closed. Within the broader context of the symphony as a whole, however, the final harmony of the Romanze functions not as a concluding tonic, but as the dominant of the D minor in which the next movement begins.

The most complex fragment is the first movement. It comprises a slow introduction (bb. 1–29), a compact exposition (bb. 29–86), and a comparatively sprawling development (bb. 87–296), the end of which is signalled by the pedal point on the dominant A in bb. 285ff. The return of the tonic major that follows, however, is not accompanied by anything that comes even close to a formal recapitulation, and what little recapitulation there is is not the recapitulation that goes with the exposition from earlier in the movement. Phrase-structurally, bb. 297–337 are most reminiscent of the final stages of a subordinate theme, leading to the cadence that concludes the recapitulation that is, as such, largely missing; and the thematic material in these bars is derived not from the exposition, but from the second of two new themes that were first presented in the development (bb. 121ff. and 147ff., respectively). Only at b. 337 does motivic material from the exposition’s main theme return, now clearly with post-cadential function (i.e., as a codetta or coda). The formal openness of the first movement is answered in the finale, the exposition of which begins, paradoxically, with a recapitulatory gesture: its main theme combines a close variant of the first new theme from the first movement’s development (the one from bb. 121ff.) with the head motive of the first movement’s main theme, thus to a certain extent providing compensation for the missing recapitulation of these themes in the first movement.

***

As all these examples illustrate, Romantic form does not exist in a universe separate from classical form, but rather maintains a state of perpetual dialogue with it. Forms both small and large are, to repeat Blume’s words cited above, ‘common to both’ even if they are ‘subject … to amplification, specialization, and modification’.16 From the perspective of the music analyst, there are obvious advantages to this: if duly modified, established theories of classical form – theories that are at least somewhat familiar to most undergraduate music students – can go a long way in explaining what happens in this music. But there is also a drawback. Because theories of classical form are so readily applicable to Romantic music, the risk is to treat them as a standard – a norm – to which everything that is different (and in Romantic music, a lot is different) relates as a deviation. Yet in the context of Romantic music, that which by classical standards would be a deviation can be the norm, rather than the exception, and should be interpreted accordingly. Finding a balance between the continuing presence of classical formal types and the self-sufficiency of the Romantic style is perhaps the greatest challenge to the analyst of Romantic form.

Expression as the Purpose of Song

On first hearing a typical eighteenth-century German song, perhaps by Christian Gottfried Krause or Beethoven’s early teacher Christian Gottlob Neefe, and comparing it to a Romantic song by a composer such as Schubert or Fauré, one might first be struck by their differences. The earlier work would be short and simple, designed for an amateur performer, requiring only a small vocal range and minimal accompaniment, while the later one might be longer, more taxing for both singer and pianist, and much more sophisticated in melody, harmony, and musical design. Despite these differences, in some ways the earlier piece would hold the kernel of what came later: the goal of expressing human experience through sung poetry.

During the eighteenth century, aesthetic preferences shifted away from the intricacy of late baroque style. Philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (who was also a novelist and composer) asserted the value of simple expressive art that was closer to nature. Intellectuals began to value and seek out folk culture (however unclearly that was defined). Music was seen as an important tool for educating and shaping children, and hence it was important to provide mothers with singable material for that purpose. All these factors combined to encourage the production of songs that could be performed by amateurs, as exemplified in collections such as Oden mit Melodien, published in Berlin in the early 1750s. Somewhat later in the century, composers such as Carl Friedrich Zelter and Johann Friedrich Reichardt began to write songs that blended the simple folk-like tone with virtuosity, creating a hybrid style: for example, a relatively simple melody might conclude with a cadenza reminiscent of opera.

Broadly acknowledged as the master whose oeuvre redefined art song, the Viennese composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828) developed a new approach to the genre. While Schubert was well aware of earlier models and wrote many strophic songs with folk-like melodies, he also used other musical forms. He was a master of modified strophic form, in which significant variation is added to the basic strophic structure. ‘Im Frühling’ (D. 882, 1826), on a poem by Ernst Schulze, provides a powerful example. A wistful but calm first stanza portraying springtime is followed by one with a more florid accompaniment, and then by a mini-storm scene that accompanies the same melody – but in the minor mode – for the third stanza, expressing the poetic character’s despair over lost love. The final stanza brings a return to major with new ornamentation. In through-composed songs modelled in part on ballads by Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg (1760–1802), Schubert abandoned strophic repetition altogether in favour of new music to go along with shifting poetic situations.

Schubert was frequently hailed for his ability to internalise and reproduce a poet’s intention, as though he could magically convert verbal into musical meaning. His friend Joseph von Spaun commented that ‘Whatever filled the poet’s breast Schubert faithfully reflected and transfigured. … Every one of his song compositions is in reality a poem on the poem he set to music.’1 Schubert used many musical techniques to express what he found through his sensitive readings of poetry. He made the piano an equal partner to the singer, often writing figurations to represent something about the outward scene, such as rippling water or a galloping horse, while the vocal part portrayed the inward experience of the poetic persona. He employed many kinds of musical nuance – altering harmonies, rhythms, phrase lengths, and more – to bring out particular words or moments of change in the text.

Schubert altered and deepened the art song in many ways – yet even as the means of musical expression grew more complex, the central goal of song remained the same: to convey textual meaning through music. Song was still idealised as being natural and unaffected, portraying the character’s experience in a direct way in order to arouse empathy and understanding in listeners.

Nevertheless, some literary figures, notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, did not like to see the symmetrical qualities of their verbal creations altered to fit new musical structures, which might seem to obscure the lyric voice. Goethe seemingly preferred the compositions of Zelter (a personal friend of his) to those of the young Schubert – at least, the poet never replied when Spaun, in 1816, sent him a carefully copied group of Schubert’s settings of his poems. Goethe’s taste reflected Weimar Classicism even as the literary world had already begun its shift towards Romanticism. Already in the 1790s, the young Friedrich Schlegel, leader of the Jena Romantic circle, had sought Goethe’s approval while also teasing and mocking some aspects of Weimar Classicism.

The genre of art song came into its own in the nineteenth century, becoming valued as a worthy art form on a par with larger works such as operas. This development paralleled the rise of the stand-alone character piece for piano. It is no coincidence that Felix Mendelssohn chose the title Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words) for several collections of piano works, paying a sort of backhanded compliment to the vocal genre by implying that music did not need a sung text to express something equivalent to poetry.

Early Romantic Concepts: Interdisciplinarity, Symphilosophy, the Fragment, and Subjectivity

Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829) was the guiding intellect of the early Romantic movement in Germany, or Frühromantik. This movement took shape during the 1790s in intellectual and social circles of Berlin and the small university city of Jena, not far from Weimar. The early Romantic ideas were intertwined with the intense personal relationships of those who first expressed them. Other key members of these Romantic circles included Schlegel’s brother August Wilhelm; Friedrich’s wife, Dorothea (a daughter of the important Jewish thinker Moses Mendelssohn; Felix Mendelssohn was her nephew) and August Wilhelm’s wife, Caroline; Friedrich von Hardenberg, who wrote poetry under the name Novalis; and the theologian and translator Friedrich Schleiermacher. The group placed high value on what Schlegel called ‘Symphilosophy’, meaning ideas that grew from shared interdisciplinary creativity.

The early Romantics were pioneers in the study of drama, literature, and the visual arts, though they had little to say about music. Moving away from the sole emphasis on ancient classics, they looked closely at European literature from the Middle Ages and beyond, disseminating their thoughts through lecture series and translations. While they deeply appreciated art in various styles, the Romantics strove to escape whatever they found overly self-contained and conventional; in their own time, they advocated what Schlegel labelled ‘Romantic irony’, meaning a kind of self-awareness within the artwork that both acknowledges and breaks away from artificiality.

Schlegel pioneered a genre he called the fragment. He wrote many of these pithy comments, and also recruited his friends as contributors, publishing fragments in sets without revealing who had written which ones (though later editors have worked out attributions). This mix of materials, ideas, and authors was intended to symbolise the interconnectedness of the universe. One of Schlegel’s fragments stated that ‘A fragment, like a miniature work of art, has to be entirely isolated from the surrounding world and complete in itself like a hedgehog.’2 Yet he also made a point of grouping fragments, creating a clear sense of relationship amongst them. This opposition between independence and connectedness was later mirrored in the art-song genre.

One of the most influential fragments was a fairly long one by Friedrich Schlegel himself on the nature of Romantic poetry. He begins by writing that

Romantic poetry is a progressive universal poetry. … It tries to and should mix and fuse poetry and prose, inspiration and criticism, the poetry of art and the poetry of nature; and make poetry lively and sociable, and life and society poetical … .

Schlegel emphasises the universality of Romantic poetry by showing how it unites opposites. Later in the passage, he focuses on the progressiveness of Romantic poetry by showing it to be an ongoing process rather than a finished product.

Other kinds of poetry are finished and are now capable of being fully analyzed. The romantic kind of poetry is still in the state of becoming; that, in fact, is its real essence: that it should forever be becoming and never be perfected.3

On first encounter, these ideas may seem contradictory. How can something called a fragment be complete in itself? What does it mean for a work of art to be a process rather than a thing? All these apparent contradictions, though, are conscious and deliberate, and they reflect the central Romantic idea of infinite striving or yearning (Sehnsucht in German). This conception of constant growth and development as a goal was drawn from other late-eighteenth-century thinkers. Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy, rather than laying out a set of rules, concludes that what humans should do is continually to seek the moral law. In Goethe’s drama Faust, Mephistopheles sets conditions stating that Faust will forfeit his soul only when he expresses complete satisfaction with a particular moment and wants to remain there rather than quest eternally onward. The belief that the answer consists of more questions was central to early Romantic thought.

These central Romantic ideas – interdisciplinarity, shared intellectual work, and the interplay between fragment and larger structure – should help clarify why, as explained in the opening chapter to this volume, Romantic aesthetics preferred art to be ‘incomplete, fragmentary, open, evolving, [and] stylistically heterogeneous, in contrast to the perceived formal unity of the works of classical antiquity’.4

Romantic poetry also strongly emphasised individual experience expressed in the first person, known as the ‘lyric I’. It should be noted that this ‘I’ can but does not always represent the poet in an autobiographical sense. A poet may write in the first person while presenting the experiences of some other character. For this reason, the phrase ‘poetic persona’ is often used to stand for the character represented by this lyric I.

Paradoxically, the individual experience portrayed in Romantic literature was frequently understood as universal. While the scenes and events of a novel or poem belong in a narrow sense to its story and main character, those particulars partake in broader archetypal experiences that were assumed to be universal, such as leaving home, falling in love, growing old, and so on. This perspective strongly contrasts the idea of our time that literature should emphasise difference and identity, showing how various individuals are set apart through their gender, class, ethnicity, race, or place of origin, and thus may experience the world in vastly different ways. The Romantic assumption of universality helps to explain why both poetry and song were intended and expected to arouse understanding and empathy.