Long regarded as the paradigmatic example of Romantic musical landscape, Felix Mendelssohn’s overture The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave), Op. 26, remains unique insofar as the surviving evidence related to its composition allows us to trace the inspiration for the work’s distinctive opening contours to a specific time and place. The broad outlines of this story are well known.1 During the summer of 1829 Mendelssohn travelled to Scotland with the diplomat and writer Karl Klingemann, a trip that included a walking tour of the Highlands and the Hebridean archipelago. On the afternoon of 7 August near the small town of Oban on the Scottish mainland, Mendelssohn attempted to document his impressions of the surrounding landscape in a pencil drawing that offers a tantalising glimpse of the archipelago for which the composer was about set sail (see Fig. 4.1). Arriving later that evening on the Isle of Mull, Mendelssohn continued to record his impressions, this time in the form of a twenty-one-bar sketch whose musical substance closely resembles the opening of the completed overture. Of particular interest here is Mendelssohn’s prefatory note in which he claims a direct connection between his own reaction to the landscape of the Hebrides and the music that he immediately felt compelled to jot down. Indeed, it is precisely the directness of this claim that demonstrates why the overture in its final form has continued to serve as an important point of reference for anyone wrestling with the fraught question of how a musical work can be said to evoke a particular landscape or, indeed, the idea of landscape more generally.2

Figure 4.1 Felix Mendelssohn (1809–47), Ein Blick auf die Hebriden und Morven (A View of the Hebrides and Morven), graphite, pen, and ink on paper, Tobermory, 7 August 1829

In the case of The Hebrides, discussions concerning its presumed connection to the place by which it was inspired have naturally been informed by other factors including, most prominently, the suggestive power of the work’s title.3 This serves to remind us that while in recent years our understanding of Mendelssohn’s overture as a ‘landscape’ has been shaped by the musical sketch and accompanying commentary described above, as is the case for many Romantic works, the perceived presence of visual and scenic elements has for most listeners been determined largely by the overture’s more immediately accessible ‘programmatic’ layer. With respect to Romantic instrumental music more generally, such programmatic layers have traditionally included work and movement titles, as well as printed programmes and other kinds of programmatic descriptions. In vocal and choral music, it is the poetry itself that has tended to play the most important role in establishing a sense of place, while in opera a similar role has been played by libretti, staging manuals, and the like. Of course, there are other kinds of texts that have been used to make interpretive claims about the relationship between music and landscape in the nineteenth century, including (1) a composer’s letters, diaries, and other writings; (2) paratexts, including autograph annotations in a composer’s sketches, manuscripts, and printed scores; and (3) contemporary performance reviews and other forms of written commentary and analysis. Whereas our understanding of the relationship between music and landscape continues to be shaped by such texts, the question of how this relationship is manifested in specifically musical terms continues to pose considerable interpretive challenges. With this in mind, I will focus my attention in what follows on two larger issues raised by Mendelssohn’s overture, both of which are relevant to the perceived presence of the visual and scenic in Romantic music in all its manifestations. I will begin by considering the claim that a musical work has the ability to evoke landscape in the first place, whether in general or specific terms. Following a brief exploration of the depiction of music and music making in Romantic art, I will turn my attention to the notion of landscape as an object of contemplation, considering it both as an activity from which composers frequently drew creative inspiration, and as a metaphor that has often been used to make sense of individual works whose musical identity is in some way bound up with the idea of landscape broadly construed.

Evoking Landscape

When Mendelssohn jotted down his musical impressions of the Hebrides in 1829, the notion that instrumental music had the potential to illustrate already had a long and distinguished history. Amongst the most important precedents are the pièces de caractère of François Couperin (1668–1733), works whose evocative titles often seem to align closely with their musical character. Of more immediate relevance is the characteristic symphony, the illustrative genre par excellence that emerged during the second half of the eighteenth century. Often remembered for their vivid depictions of storms, battles, hunts, and pastoral idylls, these works also frequently gave musical expression to a range of national and regional characters.4 While not programmatic in the Listzian sense, such works anticipate the Romantic conception of programme music insofar as their descriptive titles are often supplemented by elaborate prose descriptions. But to the extent that the characteristic symphony draws on an established tradition involving the musical representation of things or events, it is important to remember that the genre also placed a strong emphasis on human emotions and expressive content. Indeed, it is precisely this duality that allows us to make sense of Beethoven’s own contribution to the genre in his Sixth Symphony (1808), a work whose title he gave in a letter to his publisher as Pastoral Symphony or Recollections of Country Life: More the Expression of Feeling than Tone-Painting.5 Yet, as it turns out, Beethoven’s apparent rejection of Tonmalerei as suggested by this subtitle is not borne out by the completed symphony. For in addition to the numerous examples of musical illustration that can be found throughout the work, the very form of the second movement (‘Scene by the brook’) appears to have been determined by the kind of landscape it purports to evoke. In his discussion of an early sketch containing material for this movement, Lewis Lockwood has observed that underneath a preliminary version of the 12/8 figure, which in its final form has been widely understood to represent the motion of the brook, Beethoven wrote: ‘je grosser der Bach je tiefer der Ton’ (the greater the brook the deeper the tone). For Lockwood the significance of this annotation as it relates to the movement as a whole is that Beethoven ultimately went on to establish a ‘correlation between the image of the widening and deepening brook and the orchestral forces that develop the form of the movement’.6 We might even go so far as to say that it is precisely the movement’s sense of motion that ultimately informs Beethoven’s attempt to evoke this particular landscape. Indeed, as Benedict Taylor has recently proposed, ‘music can successfully model a landscape to the extent that it implicates its moving, dynamic aspects, its temporal processes’.7

Whereas the early reception of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony reflects the competing aesthetic claims embedded in the work’s subtitle, the first half of the nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of a critical vocabulary that revealed another kind of tension in the reception of Romantic music: namely, between musical works that were understood to illustrate and those that were thought to possess narrative qualities. In his discussion of the role of metaphor in nineteenth-century music criticism, Thomas Grey identifies a ‘“pictorial” mode (appealing to a range of “natural”, rather than abstract, imagery), and a “narrative” mode, which ascribes to a composition the teleological character of an interrelated series of events leading to a certain goal, or perhaps a number of intermittent goals that together make up a more or less coherent story’.8 But as Grey goes on to argue, these modes are by no means mutually exclusive:

[t]he ‘story’ conveyed by an instrumental work might, for some critics, have more in common with the kind of story conveyed by a series of images: a story expressed in mimetic rather than diegetic terms, in which levels of ‘discourse’ cannot be distinguished from the medium itself, and in which the events ‘depicted’ resist verbal summary. Furthermore, the categories of ‘pictorial’ or ‘descriptive’ music – malende Musik – most often embraced concepts of musical narration as well, at least in the critical vocabulary of the earlier nineteenth century.9

The extent to which these metaphorical modes often overlapped is made plain in a rarely discussed passage that Grey cites from the second part of Franz Liszt’s essay on Berlioz’s Harold in Italy first published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1855. This overlap is particularly evident in the context of Liszt’s discussion of the emerging interpretive tradition around the symphonies, sonatas, and quartets of Beethoven, in which critics had endeavoured, in Liszt’s words, ‘to fix in the form of picturesque, poetic, or philosophical commentaries the images aroused in the listener’s mind’ by these works.10

At first glance Franz Brendel’s often-cited tribute to Robert Schumann’s early piano works appears to offer a straightforward example of the ‘pictorial mode’. Upon closer examination, however, it becomes apparent that the way in which Brendel uses the metaphor of landscape to illuminate specific musical features in Schumann’s music does not, strictly speaking, draw on ‘natural imagery’, but rather on the representation of such images.

Schumann’s compositions can often be compared to landscape paintings in which the foreground gains prominence in sharply delineated, clear contours while the background becomes blurred and vanishes in a limitless perspective. They may be compared to fog-covered landscapes from which only now and then an object emerges glowing in the sunlight. Thus the compositions contain certain, clear primary sections and others that do not protrude clearly at all but rather serve merely as backgrounds. Some passages are like points made prominent by the rays of the sun, whereas others vanish in blurry contours. These internal characteristics find their correlate in a technical device: Schumann likes to play with open pedal to let the harmonies appear in blurred contours.11

If, for Brendel, this description pertained most directly to the Fantasiestücke, Op. 12, Berthold Hoeckner has shown that it applies equally well to Schumann’s celebrated evocation of distant sound in his Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837), specifically at the beginning of the cycle’s penultimate number, ‘Wie aus der Ferne’, where the use of the damper pedal gives rise to a distinctive texture that ‘easily compares to Brendel’s image of a landscape with a blurred harmonic background against which melodic shapes stand out like sunlit objects’.12 Given that the relationship between music and landscape being proposed here is more precisely a relationship between music and the visual representation of landscape, it is worth considering whether the desire to draw technical and formal parallels between musical composition and painting risks overinterpreting the presumed visual dimension of the works under discussion, especially given that Schumann was not attempting to compose landscape in the way that would become increasingly common in the decades that followed.

During the second half of the nineteenth century conscious attempts to compose landscape often drew on a compositional device referred to as a Klangfläche (sound sheet), a device that as Carl Dahlhaus has noted gave rise to the most ‘outstanding musical renditions of nature’ in Romantic music.13 Dahlhaus provides three examples (the ‘Forest Murmurs’ from Act II of Richard Wagner’s Siegfried, the ‘Nile Scene’ from Act III of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, and the ‘Riverbank Scene’ from Act III of Charles Gounod’s Mirielle), each of which functions as a self-contained musical tableau. Characterised by outward stasis and inward motion, these passages are suggestive of landscape in part because the Klangfläche is ‘exempted both from the principle of teleological progression and from the rule of musical texture which nineteenth-century musical theorists referred to, by no means simply metaphorically, as “thematic-motivic manipulation”, taking Beethoven’s development sections as their locus classicus’.14 Indeed, Dahlhaus goes on to observe that ‘musical landscapes arise less from direct tone-painting than from “definite negation” of the character of musical form as a process’, something that is particularly evident in the later nineteenth-century use of the Klangfläche where the status of the resulting tableaux is determined partly in relation to the larger symphonic narratives in which they are embedded.15

Perhaps even more common during the latter half of the nineteenth century are those works whose relationship to landscape is bound up with the claim that their creation has been inspired by an actual geographical locale. Amongst the most ambitious attempts to compose a large-scale instrumental work in these terms is Franz Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage (composed between 1837 and 1877), a sort of musical travelogue inspired by the composer’s ‘pilgrimages’ to Switzerland and Italy. As Liszt writes in the preface to the work’s first volume, ‘Suisse’, his aim was to give ‘musical utterance’ both to the ‘sensations’ (sensations) and ‘impressions’ (perceptions) that he encountered during his travels. How precisely this is conveyed to the listener in terms of specificity of place is, of course, more complicated. Whereas in the earliest published editions of the work each individual piece is preceded by a full-page engraving that was presumably meant to put the performer in mind of the specific locales being evoked, for most contemporary listeners the work of musical illustration would have been carried out by the individual movement titles, as well as through the use of well-established musical topics.

This desire to draw connections between musical works and the places in which they were composed has long played an important role in accounts of one composer in particular: Gustav Mahler. The history of this interpretive tradition can be traced, in part, to the testimony of the conductor Bruno Walter. In the summer of 1896 Walter visited Mahler at his lakeside retreat in the Austrian village of Steinbach am Attersee where the composer was at work on his Third Symphony. Walter later reported that as he stepped off the boat and glanced up towards the surrounding mountains Mahler offered a most unconventional greeting: ‘You don’t need to look – I have composed this all already’ (‘Sie brauchen gar nicht mehr hinzusehen, das habe ich alles schon wegkomponiert’).16 Earlier that year Mahler provided a more detailed account of his belief in the mimetic power of his own music. Commenting on the Third Symphony’s minuet, which at the time still bore the title ‘What the flowers in the meadow tell me’ (Was mir die Blumen auf der Wiese erzählen), Mahler reportedly said:

You can’t imagine how it will sound! It is the most carefree thing that I have ever written – as carefree as only flowers are. It all sways and waves in the air, as light and graceful as can be, like the flowers bending on their stems in the wind. … As you might imagine, the mood doesn’t remain one of innocent, flower-like serenity, but suddenly becomes serious and oppressive. A stormy wind blows across the meadow and shakes the leaves and blossoms, which groan and whimper on their stems, as if imploring release into a higher realm.17

In addition to his belief that this landscape served as the primary source of inspiration for the movement as a whole, Mahler also went one step further by suggesting that the listener would be able to envision Steinbach and its surroundings in the music’s very fabric: ‘Anybody who doesn’t actually know the place … will practically be able to visualise it from the music, so unique is its charm, as if made just to provide the inspiration for a piece such as this.’18 While connections of this sort have remained an important thread in the reception of Mahler’s music, such interpretive moves have also been treated with scepticism. Theodor W. Adorno was amongst the first to resist the idea that these works might reflect specific features of the landscapes in which they were composed. And while it is true that his discussion of Das Lied von der Erde makes reference to its place of composition amongst the ‘artificially red cliffs of the Dolomites’, Adorno is careful not to propose any direct link between this singular landscape and the musical fabric of this remarkable work.19 It is nevertheless worth remembering that Mahler’s symphonies have long been thought to aspire to the visual, an aspiration that is particularly evident in those passages that invoke the rich tradition of the operatic landscape tableau.

Of course, the presence of landscape imagery in Romantic music was not always bound up with these illustrative modes. Daniel Grimley has been particularly attentive to this issue as it relates to questions of landscape and nationhood in the music of Edvard Grieg, Carl Nielsen, Jean Sibelius, and Frederick Delius. And while for Grimley the idea of landscape in this music is closely tied to broader cultural formations of national identity, he also substantially broadens our understanding of this topic by drawing on perspectives from historical-cultural geography and environmental studies, including a range of ecocritical discourses. In the context of Grieg’s music, for example, he has argued persuasively that landscape is not ‘merely concerned with pictorial evocation, but is a more broadly environmental discourse, a representation of the sense of being within a particular time and space’.20 Grimley also encourages us to think of the function of landscape here both as a spatial phenomenon (through associations with pictorial images connected to the Norwegian landscape and the folk traditions of its inhabitants) and as a temporal one (involving historical memory and attempts to recover or reconstruct past events). In his close readings of individual works, he also interrogates their formal properties in a way that forces us to think about landscape not only in terms of the evocation of a particular place, but also in terms of a ‘more abstract mode of musical discourse, one grounded in Grieg’s music with a particular grammar and syntax’.21

Excursus: Making Music in Romantic Art

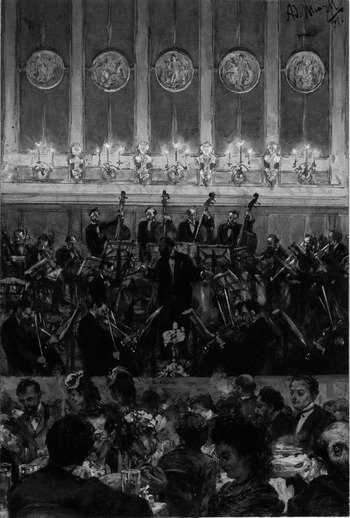

Nowhere are the connections between nineteenth-century musical culture and the visual and scenic manifested more clearly than in the depiction of music making in Romantic art. Prominent examples include Moritz von Schwind’s Eine Symphonie (1852) and Gustav Klimt’s Schubert at the Piano (1899), the former depicting a performance of Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, and the latter offering an idealised portrait of Franz Schubert. In contrast to these composer-centric canvases, the works of the German painter Adolph Menzel are particularly notable for their emphasis on the social dimension of music making. In The Interruption (1846), Menzel captures the moment in which a group of unannounced house guests interrupt two young women who have been making music in a lavish drawing room, while in Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim in Concert (1854, Fig. 4.2) the focus is entirely on the two musicians whose studied concentration reflects the intensity of an unfolding performance.22 More explicit in its diagnosis of music as a social phenomenon is Menzel’s Bilse Concert (1871, Fig. 4.3). Although the orchestra here occupies a prominent position in the middle of the canvas, Menzel devotes equal space to the audience (at the bottom of the frame) and the candlelit busts of composers who keep silent watch over the performers and their audience (at the top).23 Finally, in Flute Concert of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci (1852, Fig. 4.4), Menzel draws our attention both to the elaborate setting in which the performance takes place and to the absorption of the musicians and auditors in attendance. So popular was this painting that on the occasion of Menzel’s seventieth and eightieth birthdays it was transformed into a tableau vivant, demonstrating the continued vitality of a tradition that flourished during the nineteenth century as entertainment for the educated middle class.

Figure 4.2 Adolph Menzel (1815–1905), Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim in Concert (1854), coloured chalks, 27 × 33 cm, Private Collection

Figure 4.3 Adolph Menzel, Bilse Concert (1871), gouache, 17.8 × 12 cm, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

Contemplating Landscape

Amongst the most important functions of Romantic landscape painting was to provide the viewer with an opportunity to (re)experience the sublimity of the natural world through an act of private contemplation. So central was this impulse to the painterly imagination in the nineteenth century that the act of contemplation would itself become the focus of numerous canvases. This is particularly evident in the tradition of the Rückenfigur, in which the depicted figure is seen from behind. Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) remains the most representative example of this tradition, while Carl Gustav Carus’s Pilgrim in a Rocky Valley (c. 1820) offers a useful point of comparison in that it makes explicit the religious dimension often associated with this mode of solitary contemplation. Composers were often depicted in similarly contemplative poses, including in the Rückenfigur of Beethoven by Joseph Weidner and Arnold Schoenberg’s Self-Portrait from Behind (1911).

In the context of nineteenth-century compositional traditions this mode of private contemplation occupies a particular place of prominence in the genre of the lied. Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (1816) offers a particularly compelling manifestation of this tendency. In the first song the speaker contemplates the landscape that separates him from his beloved, a present-tense reflection shot through with a sense of melancholy that is carefully matched by Beethoven’s setting of the poem’s first stanza: ‘Upon the hill I sit / Gazing into the blue land of mist / Looking towards the far pastures / Where I found thee, beloved.’ But as the speaker begins to dwell on his own isolation, the music takes on an increasing urgency; not in the vocal line, which remains largely the same from stanza to stanza, but rather in the accompaniment, which undergoes a further intensification midway through the final stanza.

This isolation is further highlighted in the cycle’s second song, above all in the unusual treatment of the vocal line in the middle stanza. Here the melody is transferred to the piano while the singer declaims the text on a single pitch: ‘There in the peaceful valley / Grief and suffering are silenced: / Where in the mass of rocks / The primrose dreams quietly there / The wind blows so lightly / Would I be.’ To the extent that this hushed meditation reflects the experience of someone lost in thought, this moment represents a deepening of the cycle’s contemplative mode. Yet as we bear witness to the speaker’s innermost thoughts, we are also provided with an opportunity to experience the stillness of the landscape by which he is surrounded.

Although the contemplation of nature is often understood to be an act of communion that requires the subject to be quiet, reverent, and immobile, many composers had an active relationship to the landscapes they inhabited. While these composers rarely ‘worked’ outside in the manner of the plein-air painters, they often sketched as they walked. Beethoven’s pocket sketchbooks, for example, reveal the extent to which the composer’s surroundings inspired creative activity. Mahler, too, is reported to have composed in this manner, sketching out Das Lied von der Erde (1908) during the course of his daily walks through the mountain landscapes of the eastern Dolomites.24 Of course, the idea of traversing a given landscape was thematised in many nineteenth-century works, from Schubert’s Winterreise (1827) to Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (1899). In the case of Verklärte Nacht our understanding of the sextet’s narrative power is shaped in part by the eponymous poem by Richard Dehmel that was included in the first published edition of the score. Indeed, the music ultimately seems to convey the spirit and the sweep of Dehmel’s goal-oriented narrative, which begins with an unnamed woman confessing to her partner that the child she is carrying is not his. And while at the outset the night is cold and the landscape bare, through an act of forgiveness and acceptance the night is transfigured and transformed into something that is at once lofty and bright. That the narrative is presented as a nocturnal walk, recounted alternately by the narrator and the unnamed couple, is relevant insofar as the piece not only appears to reflect Dehmel’s imagery, but also possesses a musical trajectory that conveys the shifting moods of the poem. Schoenberg would later provide a detailed programme note that offers a literal mapping of poetic image and musical gesture, demonstrating the extent to which he understood this work to operate both at the level of the pictorial and the narrative.25

Whereas the musical personae devoted to the contemplation of landscape in Romantic music commonly occupied an elevated perspective (a tradition that runs from Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte to Richard Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie a century later), there is also a parallel tradition running from Schubert to Schoenberg in which the wanderers and walkers are more properly earthbound creatures, far removed from the lofty perspectives of hill and mountaintop. In the early twentieth century this tradition found an unlikely continuation in the music of Charles Ives, a composer whose embrace of the quotidian often seems to suggest a ground-level view of the world as filtered through the eyes and ears of the modern urban subject. Ives’s interest in the evocation of place is particularly evident in his orchestral works, where the use of programmatic titles making reference to specific geographical locales is often supplemented by detailed prose descriptions. In Central Park in the Dark (1906), Ives’s self-described ‘picture-in-sounds’, the composer aims to capture what might have been heard by an attentive listener ‘some thirty or so years ago (before the combustion engine and radio monopolized the earth and air), when sitting on a bench in Central Park on a hot summer night’.26 In spite of the obvious emphasis here on listening, Ives also provides a succession of richly detailed images that allow the listener to envision the source of the sounds that are being attended to so carefully by the work’s unnamed subject.

In ‘The “St. Gaudens” in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment)’, from Ives’s Orchestral Set No. 1: Three Places in New England (c. 1911–14), the act of contemplation once again plays out in the context of an urban landscape. Here the object of contemplation is Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment, a high-relief bronze that pays tribute to Shaw and his soldiers, who comprised one of the first African-American regiments to fight for the Union Army during the American Civil War. Perhaps the greatest interpretive challenge posed by Ives’s work concerns the question of what exactly this music is attempting to depict. While it is possible to identify a narrative dimension (one that reflects the ill-fated battle at Fort Wagner that culminated in the deaths of Shaw and more than half of his soldiers), when taken together with Ives’s accompanying poem this piece might also be heard as a musical response to the memorial itself, one that reflects the ‘auditory image of men moving together’.27

Finally, in ‘From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voice of the People Again Arose’ from Orchestral Set No. 2, we are presented with a composition that purports to describe an event witnessed by Ives in New York City on the morning of 7 May 1915: namely, the spontaneous reaction of a large crowd of New Yorkers to the reported loss of 1,198 lives in the tragic sinking of the British passenger ship RMS Lusitania. The illustrative power of Ives’s accompanying note makes it worth quoting at length.

I remember, going downtown to business, the people on the streets and on the elevated train had something in their faces that was not the usual something. Everybody who came into the office, whether they spoke about the disaster or not, showed a realization of seriously experiencing something. (That it meant war is what the faces said, if the tongues didn’t.) Leaving the office and going uptown about six o’clock, I took the Third Avenue ‘L’ at Hanover Square Station. As I came on the platform, there was quite a crowd waiting for the trains, which had been blocked lower down, and while waiting there, a hand-organ or hurdy-gurdy was playing in the street below. Some workmen sitting on the side of the tracks began to whistle the tune, and others began to sing or hum the refrain. A workman with a shovel over his shoulder came on the platform and joined in the chorus, and the next man, a Wall Street banker with white spats and a cane, joined in it, and finally it seemed to me that everybody was singing this tune, and they didn’t seem to be singing in fun, but as a natural outlet for what their feelings had been going through all day long. There was a feeling of dignity all through this. The hand-organ man seemed to sense this and wheeled the organ nearer the platform and kept it up fortissimo (and the chorus sounded out as though every man in New York must be joining in it). Then the first train came in and everybody crowded in, and the song gradually died out, but the effect on the crowd still showed. Almost nobody talked – the people acted as though they might be coming out of a church service. In going uptown, occasionally little groups would start singing or humming the tune.28

As was the case with Central Park in the Dark, there is a clear relationship here between the note’s descriptive detail and the work’s chaotic surface. But whereas Central Park in the Dark looks to an imagined past, From Hanover Square North attempts to capture Ives’s own lived experience as an eye- and ear-witness to the remarkable event he so eloquently describes in his note. Indeed, Ives creates a musical analogue to the ‘multiple, competing aspects of the city’ in part by dividing the orchestra into a distant choir and a main orchestra, two distinct ensembles whose relative autonomy creates a ‘visual perspective’ that allows us to ‘hear behind the foreground sounds’.29 Equally remarkable is the presence of narrative elements that foreground what Ives went on to describe as a desire to convey the ‘ever changing multitudinous feeling of life that one senses in the city’.

The Persistence of Romantic Landscape

Whereas Ives’s unique approach to the evocation of place may have found few immediate followers, the same cannot be said about the music of his British contemporaries, including Edward Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Frederick Delius, who together engaged with this tradition in a particularly influential way during the first half of the twentieth century. Indeed, it is hardly coincidental that more recent generations of British composers have continued to breathe new life into that tradition, including Peter Maxwell Davies (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise and Antarctic Symphony), and Thea Musgrave, whose Turbulent Landscapes offers an extension of the Lisztian programmatic ideal. Less obviously illustrative is Jonathan Harvey’s … towards a pure land, a work that nevertheless takes the listener on a journey towards an imagined place that Harvey has described as

a state of mind beyond suffering where there is no grasping. It has also been described in Buddhist literature as landscape – a model of the world to which we can aspire. Those who live there do not experience ageing, sickness or any other suffering … The environment is completely pure, clean, and very beautiful, with mountains, lakes, trees and delightful birds.30

Despite the staggering plurality of compositional and aesthetic priorities represented by the works of this eclectic group of composers, what binds them together is the extent to which they are part of an ongoing dialogue with musical Romanticism writ large. Indeed, their renewed exploration of the visual and scenic, as well as their engagement with questions surrounding the narrative and expressive qualities of individual works that once dominated discussions of musical representation in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, make clear the continued relevance of these traditions amongst twentieth- and twenty-first-century composers, audiences, and critics.