The Real Supernatural

Amongst the best-known supernatural evocations of the nineteenth century is Franz Schubert’s setting of Goethe’s ‘Der Erlkönig’, a piece that catapults us headlong into a wild scene: a father’s desperate ride on horseback, a boy terrorised by unseen forces, and the spirit-whisper of the malevolent Erlking (see Fig. 8.1). In and beyond Schubert’s own time the song was received as strikingly original, notable for its recasting of Goethe’s narrative (such that a storm is raging from the outset) and its tendency towards genre-bending (a conflation of ballad and lied traditions). But most novel of all, according to critics, was the character of the Erlking himself, whom Schubert depicted not as a distant phantasmagorical creature, as in Goethe’s poem, but instead as an uncannily human figure crooning a lullaby-like melody.1 The Erlking’s song is first heard pianissimo, separated from the musical world of father and son by its higher range, major mode, and rounded lyricism. But slowly, as the lied unfolds, his vocal compass begins to expand, deepening in range, absorbing motives from the two ‘real’ characters and finally breaking out of the make-believe stasis of the major mode into minor-mode actuality. His final D-minor cadence (b. 123) marks the moment when the supernatural explodes irrevocably into the natural, severing the father’s hold on his son and claiming the boy’s life (Ex. 8.1).2 The Erlking proves uncontainable, an ontological blur of human/inhuman, masculine/feminine, real/imagined, a creature hovering on the boundary between phenomena and noumena. It was for this reason that nineteenth-century listeners feared Schubert’s song – but it was also why they revered it. Indeed, the German novelist Jean Paul (Johann Paul Friedrich Richter) asked to hear the piece on his deathbed, particularly the passages of the Erlking, which ‘drew him, like everyone else, with magic power towards a transfigured, fairer existence’.3 What attracted Jean Paul was also what made Schubert’s supernatural world quintessentially ‘Romantic’: its erosion of stable distinctions between this world and the next, its promise of an enchanted real.

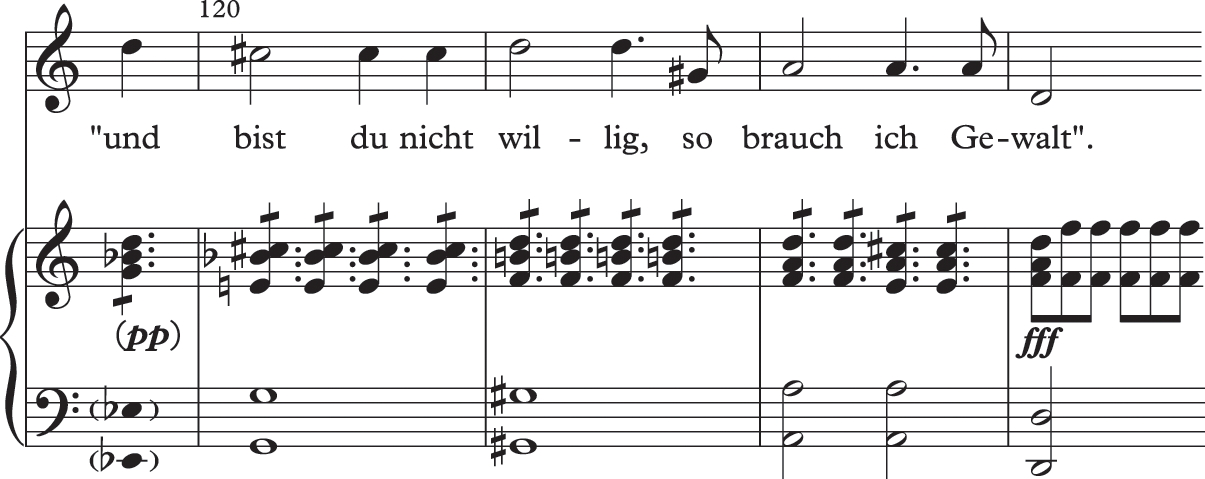

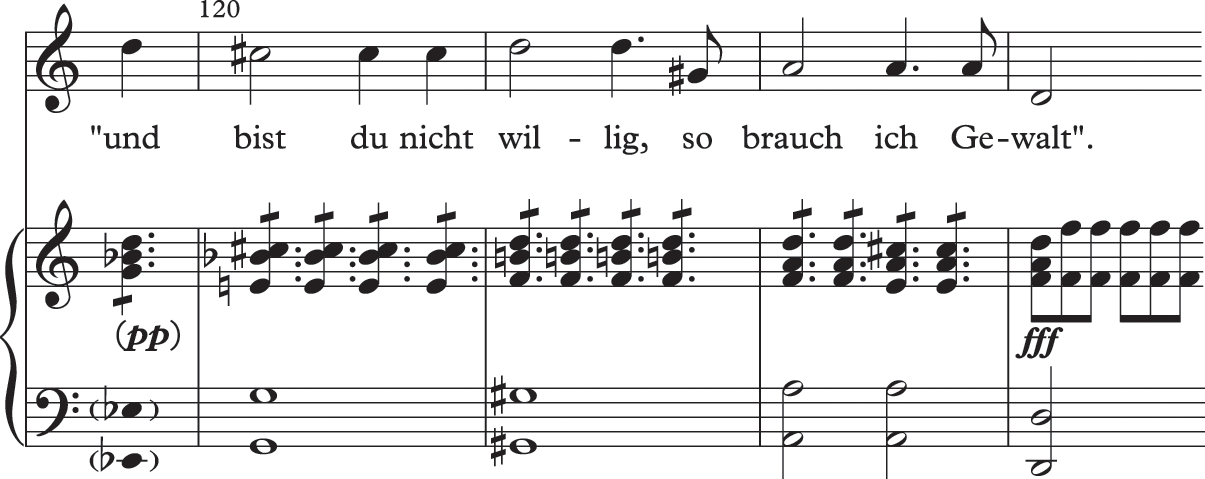

Figure 8.1 Moritz von Schwind (1804–71), Der Erlkönig (c. 1830). Oil on canvas, 32 × 44.5 cm, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna

Example 8.1 Schubert, ‘Der Erlkönig’, D. 328 (1815): the Erlking’s final minor-mode cadence ‘And if you are not willing, I shall use force’, bb. 119–23.

To understand more clearly the shift in musico-magical ontology exemplified by ‘Der Erlkönig’, and by other supernatural evocations of the period, it is helpful to start by widening our lens – considering the backdrops against which Romanticism’s newly tangible enchantment emerged. Of course, a comprehensive history of musical magic is not our aim here, but we might begin a concise overview by considering the critical terminology associated with the reception of Schubert’s song. It was, as many listeners argued, a piece whose Romanticism was rooted in modern forms of ‘fantasy’.4 This reference was not casual but gestured towards a wide and rich discourse on the fantastic, associated with the literary theory of Friedrich Schlegel, the tales of E. T. A. Hoffmann, Novalis, and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, and (later) the fiction of Charles Nodier, Théophile Gautier, and Jules Janin. As Gautier put it in 1836, the fantastic was a newly forged mode that jettisoned the make-believe wands, castles, and spells of eighteenth-century fairy tales in favour of a surnaturel vrai, a ‘true’ or ‘real’ supernatural reconciling imagination with science, dream visions with physical realities, the material with the ethereal.5

A generation earlier, Friedrich Schlegel, in his ‘Letter About the Novel’ (1799), had provided the foundation for such a definition, introducing the fantastic as a revolutionary impulse eliminating all boundaries and classifications, uniting fictional and factual narratives in an arabesque-like mixture of ‘storytelling, song, and other forms’. Fantasy dissolved not only generic constraints, but also entrenched epistemological boundaries. The source of its supernaturalism, for Schlegel, was a ‘sentimental’ or ‘spiritual’ force, a spirit of divine love permeating the created universe itself. Not otherworldly or elusive, divine magic was immanent, expressed ‘in the sphere of nature’.6 Though palpable, it was not easily captured or described; indeed, only art could apprehend it. And of all the arts, according to Schlegel, music was best suited to achieve this:

Painting is no longer as fantastic. … Modern music, on the other hand … has remained true on the whole to its character, so that I would dare to call it without reservation a sentimental art. … [The spiritual] is the sacred breath which, in the tones of music, moves us. It cannot be grasped forcibly and comprehended mechanically, but it can be amiably lured by mortal beauty and veiled in it. The magic words of poetry can be infused with and inspired by its power.7

Poetry, for Schlegel, was fantastic only when animated by spiritual sound; the two are united in his theory of Romantic fantasy in an inextricable pairing, together providing an intimation of true magic: ‘something higher, the infinite, a hieroglyph of the one eternal love and the sacred fullness of life or creative nature’.8

Backdrops for Romantic Fantasy

Schlegel’s natural conception of enchantment was not entirely novel but, as he acknowledged, recuperative, ‘tending toward antiquity in spirit and in kind’.9 His fantastic ontology represented a partial return to an earlier magical paradigm: that of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when visible and invisible, physical and metaphysical realms were conceived as parts of a resonant whole. Mingling Platonic ideas with Pythagorean and Christian tenets, Renaissance cosmologists had conceived an all-encompassing enchantment, a network of harmonic concordances flowing downwards from God, linking celestial, intellectual, and mundane planes in sacred musico-mathematical logic. Every facet of the created universe was animated by divine sound, connected to every other via resonant sympathies. The result was an organic unity – a spiritus mundi – animated by ubiquitous musical magic. Magician-philosophers harnessed its power by penetrating the secrets of the universal sympathies, the occult relationships between macrocosm and microcosm. In doing so, they achieved Orphic sway, translating divine resonance into composed melody, which could bring bodies into (or out of) tune with the surrounding universe. Spoken poetry, clothed in cosmic music, had similar powers, vibrating within material bodies to transform and illuminate. Magic was real, powerful, and proximate, intimately connected to the pursuit of natural science and philosophy.10

For Schlegel and the early German Romantics, the intellectual-magical unity of this world seemed a lost utopia, a golden age that had slowly dissipated through the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, eroded by the forces of secularism, scepticism, and materialism. Natural magic, as Friedrich Schiller put it, had been repressed by ‘the faith of reason’.11 Of course, occult beliefs did not disappear suddenly or entirely during the so-called Enlightenment, but were marginalised, no longer associated openly with reliable philosophical and scientific knowledge. Enchantment itself ceased to be regarded as ‘real’, emerging instead as imaginary, the stuff of entertainment, fraud, or childhood whimsy. The epoch of natural magic gave way to what eighteenth- and nineteenth-century critics alike referred to as the age of the ‘marvellous’.12 Amongst the key literary signals of this shift was an explosion of fairy-tale literature beginning around 1700, ushered in by collections including the Comtesse d’Aulnoy’s Les contes de fees (1696) and Antoine Galland’s free translation of Arabic stories, Les mille et un nuits (1704). Emanating largely from France, these fictions relocated enchantment to make-believe and foreign places, demoting spirits and genies (old harbingers of natural magic) to the status of illusions, pedagogical instruments, or vehicles for satire. Such tales were widely translated and imitated, establishing an ‘enlightened’ form of fictional magic, a rationalist bulwark against antiquated (but still latent) forces of superstition.

A similar trend emerged in the theatrical world: an outpouring of operatic tales of make-believe and exoticism, which shored up the idea of magic as illusory, the province of entertainment rather than serious intellectual enquiry. Music, once a key agent of magic, suffered a parallel loss in status. No longer linked to mystical mathematics or cosmic resonance, it was associated instead with the production of theatrical effects. David J. Buch describes this shift as the moment when ‘composers, theorists, and critics could define music in purely rational terms’, when sound was no longer inherently divine but simply aesthetic. By the mid-eighteenth century, this transformation had allowed ‘a distinct category for magical topics’ to emerge, a sounding marvellous.13 Jean-François Marmontel, in an entry for the famous Encyclopédie, identified ‘le théâtre du merveilleux’ as a broad category of supernatural representation defined in contrast to ‘simple nature’. His compatriot, Louis de Cahusac, in an article on ‘Féerie’, located it as a style of music distinguished by ‘an enchanting sound productive of illusions’.14 These ‘illusions’ were generated by a collection of musical topics carefully cordoned off from the realm of the actual, designed to evoke imaginary domains: muted registers, modal harmonies, and wind instruments to invoke scenes of dream or sleep; diminished harmonies and low brass scoring to conjure the underworld; static harmony and unison scoring for oracle scenes; and so forth. Such devices defined and constrained magic, which emerged as the ‘Other’ against which reason and reality were constructed.15

As the marvellous paradigm solidified through the last half of the eighteenth century, the authors and composers with whom it was associated began to strain against its boundaries, resisting the idea of magic as superficial or purely illusory. Their reaction was motivated in part by a sense of loss, a nostalgia for direct human access to mystery, enchantment, and spiritual experience, often yoked in modern criticism to burgeoning Romanticism.16 With it came early signs of a renegotiation of magic’s status. Schlegel’s real supernatural, as he described it in 1799, was clearly not just recollective, meant to reanimate aspects of Neoplatonic natural magic, but also reactive, a rejection of the constraints associated with eighteenth-century illusions. But how did the new fantastic ontology emerge? How was the domain of reason reconnected with that of enchantment? Answers to these questions are many and complex, but two major catalysts may be noted here.

The Recuperation of Magic

The first involves philosophical innovations proposed by a group of young German Romantics – the Frühromantiker – centred in Jena and Berlin in the last decade of the eighteenth century. These included Friedrich Schlegel himself, his brother August Wilhelm Schlegel, Friedrich Hölderlin, Novalis, Friedrich Schelling, and Friedrich Schleiermacher (amongst others). Amongst the primary achievements of this group was a reassessment of the ideas of Immanuel Kant, whose system of critical idealism had aimed, in part, to reconcile old Enlightenment tensions between rationalism and empiricism. Though it had done much to breach this divide, Kant’s work had, in so doing, generated a new and equally problematic separation between understanding and sensibility, phenomena and noumena. The new ‘Romantic’ or ‘Absolute’ Idealism of the young Romantics sought to eliminate this dualism, generating a philosophical model uniting real and ideal, natural and supernatural in a logical whole.17 Key to such a project was an embrace of pantheistic impulses inherited from the seventeenth-century thinker Baruch Spinoza, and updated by Gottfried Herder. Drawing on these tenets, the forgers of Romantic Idealism dismantled the idea of divine magic as emanating from a personal, removed God, replacing it with the notion of divinity as an organic force, a metaphysical animator of the natural world. Their work combined Spinoza’s monism (the notion of God as the abstract, underlying Substance of all creation) with the tenets of vital materialism (the concept of matter as enlivened, invested with active power) to produce a dynamic deity, ‘the infinite, substantial force … that underlies all finite, organic forces’.18 The result was an integration of spirituality and materiality, imaginary and actual worlds, which were subsumed into ‘an organic whole, where the identity of each part depends on every other … [as] aspects of a single living force’.19 Recast in this form, divine enchantment became compatible with – indeed, inextricable from – the material world. Perceiving magic again meant looking at and listening to God’s physical creation, the voice of nature itself, whose sound was re-endowed with magical efficacy. What emerged, as we have seen in Schlegel, was the notion of God-through-nature: the idea of a real or natural supernatural.

The second catalyst was the series of major political upheavals roiling the last decades of the eighteenth century, emanating from (though not confined to) France. These clashes, which led up to and followed the 1789 revolution, destabilised the intellectual structures that had sustained the Age of Reason; in particular, as Michel Foucault has influentially argued, they dismantled systems of marginalisation that had confined poor, ill, mad, and criminal populations to the fringes of cities and therefore the outskirts of social discourse. As the impulses of revolution gathered impetus, these populations came flooding back, crowding the streets of Paris, demanding recognition and representation. They brought with them many of the old magical beliefs that had been contained and disciplined by reason: the demons of a repressed past.20

The sense of encroaching menace that preceded the events of 1789 was felt not just in France but across Europe; indeed, the return of dark supernaturalism was anticipated in England as early as the 1760s by the rise of Gothic culture. Ushered in by Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) and extended through the late eighteenth century by the novels of Ann Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis, Gothic tales feature monsters of all sorts, from vampires to succubi and ghouls, which hover on the peripheries of the known world in medieval castles, underground caverns, and foreign locales. From these (worryingly close) places, they terrorise the domain of reason, morality, and order, suggesting a world under threat. But in the final hour, Gothic supernaturalism is almost always explained away as illusion or misconception, demons are vanquished, and order restored. The pattern is linked, in modern literary criticism, to the idea of a world teetering on the edge of collapse, a last-ditch attempt to shore up the crumbling intellectual and political structures of rationalism.21

As the century drew to a close, Gothic containment began to erode and, rather than hovering on the margins, literary monsters began to infiltrate the centre, escaping from distant or underground hiding places into the space of the modern real. It was this ontological conflation that characterised the emerging fantastic culture, which recuperated not just divine forms of enchantment but also demonic impulses.22 Post-revolutionary tales of fantasy are replete with doppelgängers, emblems of supernatural darkness who are also characters of the ‘actual’ world: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s demonic seductress Giulia in ‘A New Year’s Eve Adventure’ is also the young girl Julietta; Alexandre Dumas’s enchanting socialite in ‘La femme au collier de velours’ is also a dead guillotine victim. No resolution or explanation for these doubles is offered. In fantastic worlds, the dark supernatural is placed alongside the natural as its inescapable, inevitable counterpart, the signal of a newly integrated but also fractured world.

And it was not just the forces of revolution that produced the new ‘real’ demonism, but also those of burgeoning imperialism. From Napoleon’s continental incursions of the early 1800s to the rapid colonisation of India, Africa, and America by the major European powers, the nineteenth century was a time of unstable (expanding, contracting, collapsing) borders. Cultures of reason were threatened not just by ill and mad spectres on the edges of cities, but by the idea of monsters in more remote places which, once distant and separate, now became real and proximate. Foreign – babbling, threatening, illegible – bodies were increasingly wedded to legible ‘enlightened’ ones, the ‘civilised’ self to an imperial shadow.23 Small wonder, then, that theorists of the fantastic often describe the mode in terms of grotesque conflation or paradox. It was a mode of rupture, a recuperation of magic that was rooted not just in Romantic Idealism (including the pantheistic recovery of divine nature) but in political dislocation and violence (the return of repressed demonism). Its surnaturel vrai was enticing as well as threatening and had a marked impact on all the arts, especially, as Schlegel suggested, on cultures of musical production and reception.

We have already examined ‘Der Erlkönig’ as a symptom of the new fantastic ontology, but Schubert’s supernaturalism was by no means unique; nor was the idea of ‘real’ enchantment confined to German-speaking lands, as it extended across Continental Europe, the British Isles, Russia, and America. Magical worlds of all sorts were naturalised, rendered compatible with both reason and science in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, from fairy lands to angelic domains and hellish invocations. Below, we take brief tours of two such spaces, though it is important to note that many others existed, and that the influence of the surnaturel vrai was neither total nor unchallenged. Rather than a universal shift, the rise of Romantic fantasy might be understood as a general cultural drift which coexisted with fragments of the older marvellous and Gothic traditions, taking a variety of forms depending on local circumstances and conventions.

Fairies, Science, and Natural Magic

The naturalisation of the supernatural may be seen especially clearly in Romantic fairy evocations, especially those of Felix Mendelssohn, which showcase the new interweaving of magic, reality, and reason.24 Like Schubert, Mendelssohn forged an early reputation by writing supernatural music, focusing in particular on Shakespearean elfin scenes. The most widely known of these was the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21 (1826), although the sound world of this piece had been anticipated less than a year before in the scherzo of the Octet, Op. 20 (1825), and would be invoked again in another scherzo – the opening piece in Mendelssohn’s collection of incidental music for Shakespeare’s play (1842). In all three works, we encounter presto, pianissimo wind and string textures, breathless motivic exchange, and an array of virtuosic whirring and fluttering figures. These effects were received by critics as strikingly original; indeed, the Overture seemed so new that it was deemed by one reviewer to have ‘no sisters, no family resemblance’.25 And, as in the case of ‘Der Erlkönig’, the work’s novelty was yoked explicitly to the new aesthetics of fantasy (the term is highlighted in a number of nineteenth-century reviews of the Overture, including those of Ludwig Rellstab and Gottfried Wilhelm Fink).26

Of course, Mendelssohn’s fairy music was not entirely unmoored from tradition. It owed a debt to earlier operatic and theatrical scores, which often cast fairy music in dance forms featuring quick tempi, quiet dynamic levels, and contrapuntal writing. But his scherzo sound departs from the elfin ‘topic’ established during the eighteenth-century marvellous epoch in that it is too quick to operate as dance music, and lacks what Buch calls the ‘elegant’ or ornamental aesthetic of such pieces, tending instead towards microscopic buzzing and humming.27 It was Fanny Mendelssohn who revealed the template for Felix’s new elfin sound in a letter describing the origins of the Octet’s scherzo. The piece, she revealed, took its direction not from musical models but from literary description and natural sound: a passage from Part I of Goethe’s Faust called the Walpurgisnacht Dream, which describes a celebratory masquerade performed in honour of Shakespeare’s fairy king and queen, Oberon and Titania.28 The music for their performance is furnished by a miniature orchestra composed largely of insects: ‘Fly-Snout and Gnat-Nose, here we are, / With kith and kin on duty / Frog-in-the-Leaves and Grasshopper – / The instrumental tutti!’29 To their buzzing and whirring, Puck dances, Ariel sings, and other supernatural creatures flit and hover. This was the imagined entomological soundscape that inspired Mendelssohn’s fairy scherzo; indeed, his insect effects were what made Fanny feel, as she put it, ‘so near the world of spirits, carried away in the air, half inclined to snatch up a broomstick and follow the aerial procession’.30 For both her and her brother, the sound of fairies was inextricable from that of bees and grasshoppers, captured and rendered into music by Felix’s novel orchestral textures.

The same close attention to nature also shaped Mendelssohn’s elfin supernaturalism in the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture. According to Julius Schubring, Felix spent much of the summer of the Overture’s composition outside, observing botanical forms and textures and listening to insect song:

On the sole occasion I rode with him, we went to Pankow, walking thence to the Schönhauser Garden. It was about that time when he was busy with the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The weather was beautiful, and we were engaged in animated conversation as we lay in the shade on the grass when, all of a sudden, he seized me firmly by the arm, and whispered: ‘Hush!’ He afterwards informed me that a large fly had just then gone buzzing by, and he wanted to hear the sound it produced gradually die away. When the Overture was completed, he showed me the passage in the progression, where the violoncello modulates in the chord of the seventh of a descending scale from B minor to F sharp minor [Ex. 8.2], and said: ‘There, that’s the fly that buzzed past us at Schönhauser!’31

Example 8.2 Mendelssohn’s ‘buzzing fly’: A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, Op. 21 (1826), bb. 264–70

Audiences (as reported in numerous reviews) heard not only flies but other small creatures including gnats in the Overture, whose textures seemed to them to vibrate with insect sound. The piece hovered in a space between natural imitation and poetic expression – in the uncertain domain of the fantastic. Its effects were borrowed and extended in a host of other ‘fantastique’ scherzi, so labelled by composers from Berlioz to Stravinsky.32

An intersection between fairy magic and entomological life was apparent not just in musical works but in literature and popular science. A survey of nineteenth-century fairy stories (including the fantastic tales of E. T. A. Hoffmann, Charles Nodier, and George Sand) reveals that elfin creatures were pervasively figured as insects, their magical miniaturism shading fluidly into microscopic realism as if one world might be housed secretly within the other. And texts on entomology made the same link, interspersing images of butterflies, beetles, and flies with fanciful renderings of fairies, sometimes to appeal to children and in other cases to personify nature’s ‘magic’.33 Across disciplines, there was a sense that looking at nature and listening closely its voice could reveal enchanted realities – a hint of the pantheistic magic that Schlegel and other Idealist thinkers associated with the organic world. Modern technology was crucial to this venture. Microscopes, newly affordable and available, promised to reveal hidden botanical and entomological wonders, and virtuosic orchestras functioned similarly, capturing ever-more delicate and inaccessible soundscapes. New instruments, both scientific and musical, breached the gap between science and magic, generating a characteristically fantastic blurring.34

But access to enchanted realities was not available to all; only the special few were gifted with senses sufficiently honed to perceive the magical sights and sounds at the heart of the created world. Acute, quasi-divine perception was the province of artistic genius, the basis of a new hierarchy elevating poets, painters, and especially composers to priest-like status. Revered, though often depicted as tortured or mad, the fantastic musician was suspended between the material and ethereal, apprehending both physical surfaces and supernatural (Platonic or vitalist) essences. This model for the inspired listener was, in some regards, a reanimation of the old Renaissance magus, though rather than manipulating the inaudible mathematical resonances of a Pythagorean universe, the Romantic composer harnessed the real sounds of a pantheistic world. Preserving these in composed ‘hieroglyphs’, he wielded not just aesthetic but metaphysical power, producing works with the capacity to transform, enliven, and elevate.35

Imperial Demons

If fairies were rationalised, given new life, by fantasy’s surnaturel vrai, so too were demons. From Goethe’s Mephistopheles (in Faust settings by Berlioz, Liszt, Gounod, Boito, and others) to Carl Maria von Weber’s Samiel in Der Freischütz and the bloodthirsty Lord Ruthven in Heinrich Marschner’s Der Vampyr, figures of supernatural evil loomed large in Romantic theatrical and instrumental repertories. Their proliferation can be dated, in part, to the rise of Gothic culture (mentioned above) as well as to burgeoning fears of political violence during the years surrounding the French Revolution. However, on the musical stage, demonic evocation also had an older provenance, hearkening back to depictions of monsters, spectres, and the underworld in opera since the seventeenth century. What was new and compelling about Romantic demons – what set them apart from older theatrical horrors – was their partial release from the imaginary world into the realm of the scientific real. Like fairies, sylphs, and angels, they were naturalised, but not by the Idealist longing and pantheistic belief that recalled benevolent magic; instead, the ‘nature’ with which demons became associated was manufactured by theories of physiological difference emanating from the human and social sciences.36

In marvellous opera of the eighteenth century from Niccolò Jommelli to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, scenes of dark supernaturalism were associated with the so-called ‘terrifying style’ (later also called the ombra topic), marked by low brass outbursts, the minor mode, diminished harmonies, bare octave or unison sonorities, rhythmic disruption, and sudden dynamic contrasts.37 This collection of gestures served to depict a range of horrors from witches to flying dragons and hell itself, acting as a carefully cordoned-off magical semiotics separating dark imaginings from ‘actual’ life. Such effects were not lost in the Romantic period, but they began to coexist with another set of topical markers: those of the exotic. These included noisy percussion (especially the janissary combination of cymbals, triangle, and drum), downbeat thumping, syllabic text-setting, static rhythms, and non-progressive harmonic structures associated with the (alleged) primitivism and ferocity of Turks, Scythians, and other heathen groups.38 Gradually, the markers of otherworldly demons began to blur into the sounds of these human ‘savages’ in a new convergence of ‘real’ and mythological malevolence.

This shift took root towards the end of the eighteenth century, when belief in the dark aspects of Christian supernaturalism (including hell and the devil) had been almost completely dismantled, rejected as medieval superstition. There was no room, amongst the educated classes, for the old demons – creatures who had once contained and focused fantasies of sadism, violence, and depravity. Such fantasies persisted, however, floating around in the collective consciousness, attaching to the poor fringes of society and increasingly, to colonial bodies on the edges of expanding Western empires. The new sciences of anthropology and ethnology fuelled this transference, generating theories of racial difference that demoted European peasants along with colonial Others to inferior status. Both populations were categorised as physically and morally inferior, inclined towards violence, gluttony, and lasciviousness. The result was a justification of imperial incursion and domestic oppression as well as the invention of what H. L. Malchow terms the ‘racialized Gothic’, a class of human fiends.39

The sonic markers of the new demonism appear clearly in Meyerbeer’s grand opera Robert le diable (1831), a work that influenced virtually every infernal evocation of the following three decades. The most famous portion of this opera was (and remains) the Act 3 finale, the dance of the damned nuns, which takes place in a quintessentially Gothic landscape: a graveyard in the courtyard of an ancient moonlit monastery. The evil Bertram has lured the opera’s hero, Robert (Duke of Normandy), to the spot, convincing him to commit a sacrilege – to pluck the evergreen branch on the tomb of Saint Rosalie, which will grant him immortality and unlimited power. The traditional signals of the ‘terrifying style’ (low brass, tremolo, minor mode, and diminished harmonies) accompany Bertram’s recitative as he calls the faithless nuns sleeping beneath the monastery stones to awake and aid him in his plan. As they come slowly back to life, however, a different set of effects begins to creep into the orchestra: a ringing triangle and a quiet, staccato motive in the upper strings. To this accompaniment, the nuns rediscover the objects of pleasure to which they had succumbed during their lives, including wine and dice. They urge Robert to complete his task and, when he plucks the fatal branch, the topical convergence already underway is fully realised: the scene shifts from minor mode to a raucous D major marked by noise, percussive clashing, and downbeat thumping. Gone are the sonic effects of Meyerbeer’s airy wraiths, replaced by those of savage revellers. The nuns are joined by demons shouting a jerky, syllabic message, and together they form ‘a disordered circle’, commencing a fortissimo bacchanale. Over the course of the scene, ghostly spirits become exotic primitives. The otherworldly collapses into the Other.

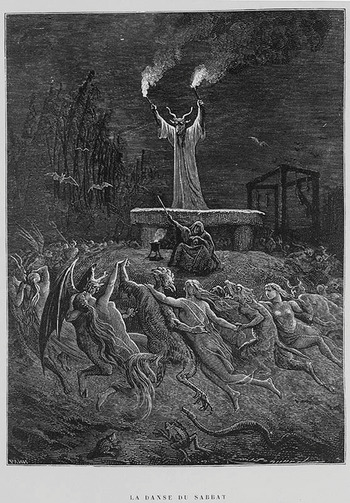

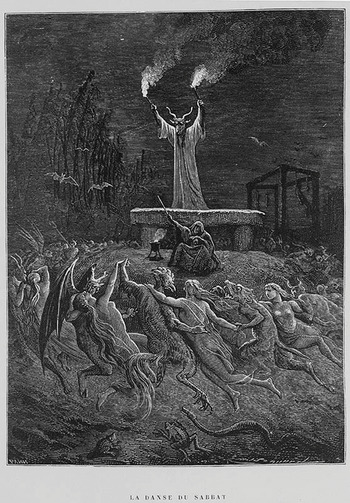

Berlioz, in one of several essays on Robert, wrote that Meyerbeer’s use of percussion signalled a newly savage ‘fantastique’ aesthetic. And the critic François-Joseph Fétis deemed the whole third act a ‘monde fantastique’, an infernal vision unlike any that had come before.40 Especially memorable, for him (as for many reviewers), was the bacchanale, a dance originally associated with Greek pagan ritual but long since appropriated by Western travel writers as a signal of primitive societies. Its telltale circle of revellers appeared in numerous nineteenth-century depictions of native African, American, Australian, and Mexican cultures. Differentiated from one another only superficially, the ring-dances associated with these places became inextricable, for many Western readers, from pagan abandon and debauchery (see Fig. 8.2).41 Meyerbeer was the first to employ the form in an infernal evocation, but he was by no means the last. In the wake of Robert le diable, a host of other composers invoked bacchanalian circles and related exotic effects in demonic scenes, including Adolphe Adam in the ballet Giselle (the ‘Bacchanale des Wilis’), Berlioz in the Pandemonium scene of La Damnation de Faust, and Liszt in the Mephisto Waltz No. 1 (‘Der Tanz in der Dorfschenke’).

Figure 8.2 La danse du sabbat, an infernal bacchanale. Metal engraving, in Paul Christian, Histoire de la magie

In these pieces, as in Meyerbeer, ombra markers intermingle vertiginously with the images and sounds of an ‘undeveloped’ colonial world, and demons themselves hesitate, like Hoffmann’s menacing doppelgängers, between mythology and ethnography. The fear they articulate is no longer that of biblical devils or eternal damnation but of vengeful slaves and savage colonies – a threat born of guilt, racial prejudice, and the terrors of modern empire.

Further Threads

The above sketches are points of departure, meant to encourage a wider consideration of music’s interface with Romantic forms of natural or scientific magic, several of which are discussed in other chapters of the present volume. We could, for instance, contemplate enchantments produced via composerly interactions with new electrical, optical, and telegraphic technologies;42 intersections amongst sound, vitalist magic, and physiology forged by instruments including the aeolian harp and glass harmonica;43 or forms of magical-musical embodiment bound up with nineteenth-century theories of sex and gender.44 Understanding Romantic sound worlds means, in many senses, tracing the history of magic – documenting music’s reinstatement as an agent of puissant enchantment, a conduit between material and metaphysical domains. The ‘end’ of the Romantic period (in so far as we can identify such a thing) might be understood as the moment when sound was, once again, divested of such power, slipping back to the status of the aesthetic, rational, or merely marvellous.