9 Tippett and the concerto: from Double to Triple

This chapter focuses on works by Tippett that, as defined by their titles, indicate a relationship to the concerto genre. Such works do not trace a direct line throughout Tippett’s career, nor can they necessarily be seen to coalesce into a coherent grouping. However, they do appear at important points. The Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1938–9) is a significant moment in the formation of Tippett’s early style. While the defining lyricism of that style reaches its point of fulfilment in the opera The Midsummer Marriage (1946–52), the Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1953–5), in part through its close proximity to the opera, is a work that provides further reflections of that lyricism in a purely instrumental context. In contrast, the Concerto for Orchestra (1962–3) forms an important part of the group of works that comes in the aftermath of Tippett’s next opera King Priam (1958–61) and which signify a new, radical direction. The final work to be titled concerto, the Triple Concerto for Violin, Viola, Cello and Orchestra (1978–9), makes a highly distinctive contribution to the identification of Tippett’s late period, however that may be defined.

In an essay titled ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’, written in 1970 and then added to in 1995, Tippett outlined his understanding of certain forms and genres, primarily the symphony, and the important distinction that he drew between ‘historical’ and ‘notional’ archetypes.1 In this essay Tippett also reflected on the nature of the concerto and the differing meanings and usages that have emerged from it and been attached to it: from the concerti grossi of Vivaldi and Handel through the classical three-movement concerto of Mozart and Beethoven to, finally, Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. This historical trajectory of the concerto is reflected in Tippett’s own concerto-based works: from the concerto grosso reference in his Concerto for Double String Orchestra through the adherence to the classical model in the Piano Concerto to the Concerto for Orchestra and its seemingly obvious reflection of Bartók’s work of that title. If these three works make such recognizable generic references, then it is also possible to hear the Triple Concerto as alluding to, in its own distinctive way, both the concerto grosso (albeit a rather distant allusion) and the orchestral concerto.

Concerto for Double String Orchestra

The Concerto for Double String Orchestra was composed during 1938–9 and, along with the First String Quartet (1934–5, rev. 1943) and the First Piano Sonata (1936–8, rev. 1942), was the first defining moment in Tippett’s career. In the Double Concerto he established a distinct and confident compositional voice that projected individual, imaginative ideas about musical form and the development and transformation of thematic materials.

As already indicated, the title is a reference to the baroque concerto grosso and the importance of textural and dramatic contrast in such works. As Tippett later recalled: ‘In calling the piece a “concerto”, I was harking back to the Concerti grossi of Handel, which I knew and loved.’2 However, Tippett was also relating to specific works from a rather different context:

I attached myself partly to a special English tradition – that of the ElgarIntroduction and Allegro and Vaughan Williams’sFantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, both of which intermingle the intimacy of the solo string writing with the rich sonority of the full string ensemble.3

This ‘special English tradition’, which also includes Benjamin Britten’s then recent Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge among other examples, is based on the texture of, as Tippett suggests, the relatively homogenous sound of a string orchestra, but also permits individual lines and specific dialogues to come to the surface. However, Tippett’s ensemble is of two string orchestras (hence the ‘double’ of the work’s title), a rather unique combination that suggests, of the works mentioned as part of this ‘tradition’, Vaughan Williams’sFantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (also composed for a double string orchestra) was of particular interest.4

The two orchestras of the Double Concerto are considered by Tippett to be ‘antiphonal groups’ rather than ‘vehicles for concertante writing, such as might be found in the concertino groups of Handel’sConcerti grossi’.5 The Double Concerto is, as the concerto grosso archetype suggests, in three movements, with the outer movements in fast tempi framing a central slow movement. While the use of folksong material will be significant, as will the sonority of the ensemble, Tippett’s acknowledgement of the importance the music of Beethoven held for him, and would continue to do so throughout his career, is a central factor in shaping the unique identity of this work:

But the musical forms deployed in my Double Concerto were those of Beethoven: a succinct dramatic sonata allegro, a slow movement virtually modelled on the song-fugue-song layout of the Andante of Beethoven’s String Quartet in F minor, Op. 95, and finally a sonata rondo with coda.6

The first movement may, through its ‘succinct dramatic sonata allegro’ formal shape, suggest a Beethovenian model, but it is realized in a highly distinct, individual way. The movement begins without introduction, moving directly and dramatically into the opening thematic statement (see Ex. 9.1). This moment also immediately indicates the separation of the two orchestral groups, with each having their own distinctive harmonic and thematic materials. The first orchestral group (hereafter orchestra 1) begins with a bold, assertive theme based around A (see Ex. 9.1 (a)). In contrast, the second orchestra (hereafter orchestra 2), whose introduction is slightly delayed in order to make clear the double effect of both texture and material, begins with a contrasting theme clearly centred on D, with the ornamental C♯ in the second bar helping to suggest D major as does the rise through F♯ in bar 4 (see Ex. 9.1 (b)).7 The coexistence of the two proposed pitch centres, A and D, results in an ambiguity about what the initial tonal centre of the movement might actually be. The distance between them is also accentuated through the articulation of the material as defined by performance indications. The theme of orchestra 1 is directed to be played marcato, which is contrasted by the espressivo instruction given to orchestra 2, resulting in a distinct difference in character between the two themes and their implied centres.

Ex. 9.1 (a) and (b) Concerto for Double String Orchestra, first movement, opening

The difference may have implications for an understanding of this opening material as constituting a first subject of a sonata form (the ‘succinct dramatic sonata allegro’), implications that lead Ian Kemp to the following conclusion:

If a sonata-allegro consists of an argument between the passionate and the lyrical, the question arises as to how these two elements are to be presented. In the Beethovenian model they appear successively. In the opening theme of the Double Concerto they appear simultaneously. By his immediate telescoping of the dramatic, marcato ‘first subject’ of orchestra 1 with the lyrical, espressivo ‘second subject’ of orchestra 2 Tippett forfeits conventional means of structural articulation.8

On the basis of Kemp’s description it becomes possible to hear both thematic statements, and implied harmonic centres, as coming together, layering the first subject over the second, which is a radical difference to the succession of themes and keys within a classical sonata-form movement. However, there are moments of convergence between the two themes. The first arrives on D in bar 4 while both gravitate towards a point of arrival on A in the eighth bar. They are also effectively ‘unified’ through the dynamic energy of the music as signified by the Allegro con brio tempo indication that envelops both themes and their articulations.

In practice the interpretation of these initial events, and the movement as a whole, must remain to some extent influenced by the composer’s own comments concerning the movement as being ‘mostly in A to start with, a kind of . . . [modal] A minor’.9 While Tippett does not provide a full justification for this description, it does direct our interpretation towards the importance of A in contrast to the reference to D, even if it is difficult to hear this opening, or the subsequent events (including the conclusion of the movement) in terms of A minor as such.

If the combination of both harmonic and thematic gestures can now be identified as the first subject of a sonata form then the emergence of a second subject is now anticipated, but where it may come, and how it is recognized, is loaded with ambiguity. From Fig. 1 there is a sense of transition that leads to the introduction of seemingly new thematic material at Fig. 1:6 (see Ex. 9.1 (c)). This thematic gesture (orchestra 1) initially outlines a D major triadic shape which is later clarified by the vertical realization of a D major harmony at Fig. 2:11. These D references construct a frame around the G-based theme that emerges from Fig. 2:7. This thematic statement comes closest to providing a second subject, but it is clearly derived from the first subject material, in terms of rhythmic shape as well as pitch, as presented by orchestra 1 (see Ex. 9.1 (a)).

Ex. 9.1 (c) Concerto for Double String Orchestra, first movement, Fig. 1:6–10

Following the apparent clarity of the initial contrast of themes within the first subject group the music has moved into a more seamless flow that actually begins to negate expectations of contrast. The resulting ‘absence of fully developed thematic contrast’ becomes, according to Arnold Whittall, one of two determining factors in the early, expositional stage of this movement, the other being the already highlighted ‘avoidance of firmly established tonal centrality’.10 The absence of such contrasts makes the identification of the subsequent stages of the proposed sonata form difficult, and also perhaps unnecessary. But the ongoing transformation of both thematic components of the first subject (see Exx. 9.1 (a) and (b)) from Fig. 4 intensifies the developmental process, while the return of this material to its original harmonic context around Fig. 8 surely indicates a process of recapitulation that is an expected feature of the form.

Tippett’s description of this movement as being in ‘a kind of . . . [modal] A minor’ leads us to anticipate a move towards A as a means of concluding the movement. The first real evidence of this possibility comes with the powerful realization of an A major harmony at Fig. 11:4, and A is articulated as the melodic focal point. But the importance of A, however it may be qualified, is not defined until the very end of the movement, when it appears, somewhat belatedly, as the final harmonic event (see Ex. 9.2). Its positioning here has been preceded by the alternation of G and D as the bassline, with the repeated focus on G♮, rather than G♯, as the expected leading note within an explicit tonal context, reflecting Tippett’s own understanding of the final centring of A as ‘modal’. But it is also notable that the proposal of A minor needs to be qualified because of the avoidance of C in the chord, which would be required in order to confirm A minor, with A supported only by its fifth, E.

Ex. 9.2 Concerto for Double String Orchestra, first movement, ending

If this suggested modal character of this final A indicates some form of relationship to an English folk tradition then the melodic material of the central slow movement asserts that relationship in a more transparently obvious way. For Clarke, there are only two themes in the work that ‘explicitly adopt folksong models’, the first of which is the main theme of this movement, the other being saved for the conclusion to the work.11

This defining theme is based on the folksong ‘Ca’ the yowes’, which is in fact a traditional Scottish ballad. It is introduced by orchestra 1 as the first sounds of the movement and receives complementary support from orchestra 2. However, this only sets the scene for the introduction of a solo violin, with its individual ‘voice’ directly rendering the melody as lyrical song (see Ex. 9.3). This introduction has a certain harmonic ambiguity. The folksong material again suggests a modal quality and there is no defining harmonic progression as such. However, the melodic line gravitates towards D as its high point, and the motion around D in the violin 2 and cello parts of orchestra 1 provides a meaningful degree of focus on this pitch, which will eventually provide the first real point of harmonic clarification (see Ex. 9.3).

Ex. 9.3 Concerto for Double String Orchestra, second movement, bars 9–24

Although D is the melodically defined harmonic centre it is surrounded by semitone clashes: C♯ against D (bars 10 and 12), C♯ against C♮ (bar 15). For Kemp, the ‘Englishness’ of ‘this gravely beautiful theme’ is derived from such clashes,12 while Andrew Burn is more specific, stating that ‘the aching semitonal clashes that underlie it [the theme] are peculiarly English, harkening back to Purcell and beyond’.13 While it is difficult to fully substantiate such claims, these clashes are important, not just because of any such implications and associations, but because they enhance the colour of the music and provide an, albeit subdued, sense of tension.

We have already encountered Tippett’s own description of the layout of this movement as ‘song-fugue-song’ and the suggestion of the slow movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in F minor, Op. 95, which follows this sequence of events, as a model. The relevance of this model becomes immediately evident. Following the arrival on the D major harmony as highlighted above, the music moves into a fugal texture (Ex. 9.4). From this point the remainder of the movement is conditioned by the development of the fugue subject until five bars after Fig. 18, when the end of the fugue and the return of the (folk) theme neatly overlap and intersect. This point of return begins to complete the tripartite ‘song-fugue-song’ shape of the movement. The ending is signified by a final statement of a D major harmony, but in a move that is similar to the conclusion of the first movement this is anticipated by C♮ rather than C♯ (Ex. 9.5).

Ex. 9.4 Concerto for Double String Orchestra, second movement, Figs. 15:11–16:7

Ex. 9.5 Concerto for Double String Orchestra, second movement, ending

This central slow movement forms a powerful statement of Tippett’s increasing attraction to, and ability to spin, strong, elongated melodic lines which become a defining essence of his musical style at this point. This movement also, in retrospect, becomes the first in what Clarke describes as a ‘great series of orchestral slow movements’ that extend through the symphonies, and includes both the Concerto for Orchestra and Triple Concerto and culminates in The Rose Lake (1991–3). Such movements ‘translate the humanising power of song into the language of instrumental music’,14 a description that is also a highly apposite summary of this particular movement.

While the reference to C that participates in the conclusion of the slow movement may be essentially local, indicating a modal avoidance of the leading-note motion of common-practice tonality, it is notable that the conclusion of the third movement, and the work as a whole, is built on a sustained statement of C major. To retrospectively hear the previous reference to C as a long-range anticipation of this conclusion may be something of an over-interpretation, but it does provide an indication that Tippett did carefully conceive the work as a totality.

Further indications of such compositional logic are also evident in the opening of this final movement. In contrast to the slow-moving textures of the second movement and its somewhat static conclusion, the final movement now begins with a bright, decisive gesture. Defined by a brief thematic motive, it is clearly centred on A as reflected by the repetitions of this pitch in the fourth bar. Although rather different in character to the opening events of the first movement, the now more explicit projection of A presents a harmonic association to that earlier moment. However, this A reference also acts as a prelude to the introduction of a main theme centred on G (Fig. 22:5), which brings both orchestras together and which can retrospectively be heard as a dominant preparation for the final C. The introduction of another new theme, now centred on A♭ as indicated by the change of key signature (Fig. 24:10), acts as a point of contrast to both the opening of the movement and the G-based thematic area, but it also conveys a sense of the familiar through its broad, lyrical contours.

These moments, their thematic materials and harmonic centres, all of which are more clearly defined than the somewhat blurred formal parameters of the first movement, are part of an overall formal shape that Tippett described as a ‘sonata rondo with coda’. The sonata element is reflected through the contrast of two themes, that based on G and that on A♭ as outlined above and which correspond to first and second subjects of sonata form. However, Tippett’s suggestion of the rondo also captures something of the energy of this music as well as reflecting contrast of, and returns to, specific thematic gestures. The ‘coda’ part of this formal outline is provided by the big, broad theme that sings through the final moments of the movement and in doing so it helps confirm C as the harmonic conclusion to the work.

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra

Tippett composed his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra between 1953 and 1955. This is his only concerto for solo instrument and orchestra, the earlier Fantasia on a Theme of Handel for piano and orchestra (1939–41) being one notable exception for this combination of instruments, with the avoidance of such forces reflecting his lack of interest in virtuosic display, Tippett later writing that he ‘was not terribly in sympathy with the late Romantic confrontation of soloist and orchestra’.15

According to Tippett, the Piano Concerto ‘proceeds directly out of the world of The Midsummer Marriage’ and he goes on to describe the music of the Concerto as ‘rich, linear, lyrical, as in that opera’,16 while Whittall hears it, and also the Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli for string orchestra which was composed during the same period (1953), as being ‘touched by the same lyric spirit as the opera’.17

If the association with The Midsummer Marriage presents one context from which the Piano Concerto can be seen to emerge, then Tippett’s relationship to the music of Beethoven presents another, equally meaningful, starting point. Tippett recalled the initial motivation for the Piano Concerto, describing ‘its precise moment of conception’, which occurred ‘when listening to a rehearsal of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto as played by [Walter] Gieseking on his return to England after the war. I felt moved to create a concerto in which once again the piano may sing.’18

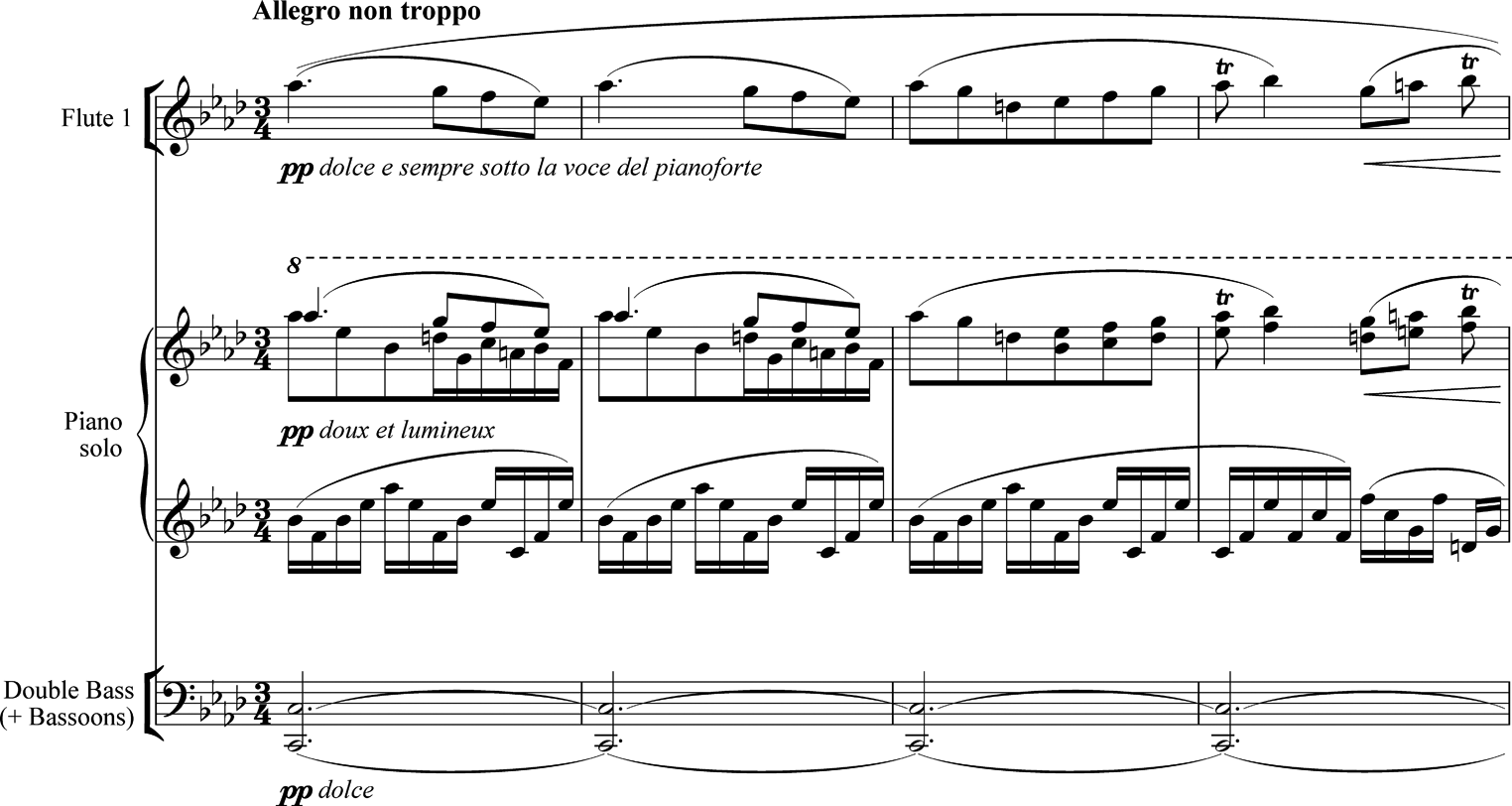

Tippett’s Piano Concerto adheres to the formal and generic conventions of the concerto, consisting of three movements: the first is marked Allegro non troppo, the second (as expected) is the central slow movement and a fast finale concludes the work. However, it is notable that it is the experience of Beethoven’sFourth Piano Concerto that provides what Tippett defines as the ‘precise moment of conception’. The most notable feature of Beethoven’s concerto is its opening gesture. Eschewing the standard orchestral introduction it starts instead with the piano. Not in an obviously dramatic and virtuosic way, but quietly with the piano’s soft reiteration of a G major harmony. This gesture has a distinct lyrical quality that is surely a significant part of what captured Tippett’s attention and which is reflected in the opening of his own concerto.

Tippett’s first movement also begins with the piano (see Ex. 9.6), which presents a quiet and subdued thematic statement that, unlike the Beethoven example, is supported by other instruments, albeit lightly. The flute also plays the upper line melody of the piano part while the bassoon and double basses provide harmonic support. The melody, which is based around a sequence of four notes – A♭, G, F, E♭ – and which is repeated to sustain a focus on A♭, provides an initial source idea that can be described as ‘germinal’ and which is subject to processes of expansion and accumulation as the movement unfolds. It is the singing, lyrical quality of this theme that brings The Midsummer Marriage to mind, as does the texture, the combination of instrumental sonorities, which is suggestive of certain ‘magical’ moments in the opera, such as the opening of the second act.

Ex. 9.6 Piano Concerto, first movement, opening

This initial gesture, through its returns to A♭, participates in establishing this pitch as the harmonic centre for the movement as indicated by the key signature of A♭ major, which in part reflects Tippett’s engagement with Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 110 in that key. However, it is C as a sustained pedal note that provides the harmonic support given to the lyrical melody of the piano and flute parts. While this is consistent with an A♭ major tonality, indicating a first inversion of the tonic harmony, it does suggest a degree of instability and implied mobility. The conclusion of the movement returns to an A♭ harmony but C is still presented as the bass, having been sustained throughout the concluding bars.

The final movement of the Piano Concerto transforms C from part of the initial A♭ harmonic context of the first movement into its own moment of radiant power. From Fig. 162 the piano part repeatedly returns to C as part of an arpeggio gesture that also involves an implied dominant harmony (G–D–G). C is repeated as a harmonic bass (Fig. 167), which then moves to repeated statements of G as dominant that extends to the final cadential gesture from G to C as the concluding event of the movement and the work. However, the clarity and security of this final C is obscured and questioned by the descending minor scale patterns and results in an ending that is ‘distinctly unstable’.19

It is the central slow movement that brings the suggested associations with both Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto and The Midsummer Marriage most clearly into focus. The movement begins softly, with an introduction played by bassoons and horns. The rising motion of the individual lines creates a quiet but dramatic gesture that is again evocative of the often magical and mysterious sounds of The Midsummer Marriage. If this is dramatic so too is the contrast provided by the introduction of the piano which is marked by dynamic and textural contrast (Fig. 75). The piano part at this stage is decorative, continually moving but with little sense of what the melodic line or its harmonic direction may be.20 The melody is in fact carried by the flute, increasingly in dialogue with other instruments, and is another telling example of Tippett’s predilection for long melodic lines that have a strong suggestion of instrumental ‘voice’, even if, in this instance, its effect is somewhat obscured by the activity of the piano part.

These reflections of The Midsummer Marriage coexist with the suggested reference to Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. This reference is at its most clear, although still far from explicit, in the passage from Fig. 83 (see Ex. 9.7). At this point Tippett establishes a dialogue of contrast between the piano and blocks of orchestral sound provided by the strings. In this moment he translates the gestural, rhetorical qualities of the slow movement of Beethoven’s concerto, which is defined by a stark juxtaposition of piano and strings, into the context of his own soundworld.

Ex. 9.7 Piano Concerto, second movement, Figs. 83–84:1

Concerto for Orchestra

While the Piano Concerto is in part shaped by its close proximity to The Midsummer Marriage, the Concerto for Orchestra, completed and first performed in 1963, forms part of a new direction initiated by the opera King Priam, which had been premiered the previous year. The opera has been described as marking a ‘radical change in Tippett’s development’, resulting in a ‘change of style’ that was ‘deliberate’ as well as ‘radical’.21 The works that come in the aftermath of the change signified by King Priam, including the Second Piano Sonata (1962) and The Vision of Saint Augustine (1963–5), as well as the Concerto for Orchestra, delineate this change. The earlier defining elements of Tippett’s style – lyricism, classical forms, tonal centres – are replaced by new interests, including fragmentation of texture, discontinuity of form, more harsh, astringent sonorities, as part of a new, more modernist context. The music of Stravinsky is now more evident as a reference point, which is first clearly articulated in Tippett’s Second Symphony (1956–7) with its reflections of Stravinsky’s own neoclassical symphonies; but, while it looks backwards to the innovative formal discontinuities of Stravinsky’sSymphonies of Wind Instruments, it is Stravinsky’s then more recent music, principally his ballet Agon, that is the most obvious source for Tippett’s post-Priam music, including the Concerto for Orchestra.22

Tippett described the Concerto for Orchestra as having some form of association with the traditional connotations and expectations of the concerto genre in that it is a ‘three-movement work with obvious references to both concerti grossi and display concertos’.23 The concerto grosso is suggested because of the importance given to specific groupings of instruments within the orchestra. While the references to ‘display concertos’ are perhaps less obvious than Tippett suggests, the various instrumental groups display their sounds, individually and in combination, in an often virtuosic manner.

There are nine instrumental groups, ‘concertini’, that form Tippett’s restructuring of the orchestra.24 These groups, and their distribution throughout the first movement, are summarized in Table 9.1. In this table the instrumental group is defined and identified (a, b, c, etc.) and related to a specific position in the movement in terms of rehearsal figures.25 The first group consists of flutes and harp (a), the second of tuba and piano (b) and the third of three horns (c). Tippett describes them as being ‘concerned with melodic line’,26 which, for Kemp, ‘creates lyricism’.27 The operation of these groups is evident from the opening moments of the work. It begins with the combination of two flutes and harp (Ex. 9.8 (a)), which is then replaced by tuba and piano at Fig. 4 (Ex. 9.8 (b)). There is clearly a sense of disconnection between each group, with one ending before the next begins. This is already evident at the point at which the first combination – that between flutes and harp – concludes (see Ex. 9.8 (b), one bar before Fig. 4). Here the lines come together into a vertical harmony consisting of C♯, D and E, while the second group, tuba and piano, begins with new material that seems to be initially centred on B♭ (see Ex. 9.8 (b), Fig. 4). Following the presentation of each group they are then combined into what Tippett defined as a ‘development’ episode (from Fig. 11) – not the kind of development associated with Beethoven as a historical model: such episodes are ‘chiefly a matter of effective juxtaposition and “jam sessions” ’.28 They do not carry the improvisational associations of the jam session from within the practices of jazz music, but such episodes do pit the already familiar groupings against each other through the retention of the identity of each group within the new process of juxtaposition.

Table 9.1 Concerto for Orchestra, first movement, formal outline (opening to Fig. 38)

Ex. 9.8 Concerto for Orchestra: (a) first movement, opening; (b) first movement, Figs. 3:6–4:5

If moments of textural contrast suggest a new conception of formal discontinuity in comparison with the development of thematic ideas in the Double Concerto, then, conversely, the initial concern with ‘melodic line’ does provide a degree of continuity with Tippett’s earlier music. This concern cannot be described as an expansive lyricism as such. But, at least at the outset, the flute part presents a clear sense of shape and direction to the line as it unfolds through a coherent six-bar phrase (see Ex. 9.8 (a)). It begins with C♯ falling to A and concludes with C♯ moving to D, albeit downwards. This pitch content suggests a move from A major to D, which could be heard as a reflection of a V–I progression in D, an interpretation that is reinforced by the beginning of the next phrase (Fig. 1), which now begins on D. However, when this line is situated against the background of the harp part, which is not congruent with such an interpretation, it is only possible to hear these tonal implications as suggestive hints that cannot be fully substantiated. Such hints continue at the conclusion to this initial grouping. The arrival on the aforementioned collection of C♯, D and E sustains a focus on D as part of this collection (see Ex. 9.8 (b)). It is also surrounded by neighbour-note motion – E♭ moving to D (flute 2) – while the harp part features C♯ as an implied movement upwards to D.

The first three instrumental groupings and their role in defining a form predicated on textural contrast are, as already indicated, part of a larger picture – a ‘collage’,29 or ‘an elaborate kaleidoscope of superimpositions’,30 with the relevance of the proposed visual metaphors already evident from the synopsis given in Table 9.1. The second stage in this changing image is that presented by the next sequence of three groups, which involve timpani and piano (d) followed by a grouping of oboe, cor anglais, bassoon and contrabassoon (e) and then two trombones (f). For Tippett these combinations, and the music composed for them, are ‘concerned with rhythm and dynamic punch’,31 which Kemp hears as ‘rhetoric’.32 The three instrumental groups that form the third stage consist of xylophone and piano (g), clarinet and bass clarinet (and piano) (h) and finally two trumpets and side drum (i). For Tippett these three groups share a concern for ‘speed’, with this concern reflected in the now even faster change of ideas.33

In moving through these various instrumental groupings and the points at which they merge, or more accurately collide (groups a, b and c between Figs. 11 and 14, and then d, e and f between Figs. 23 and 25), there is always a sense of flux, with the form of the music defined through juxtaposition and contrast rather than continuity and development.

The clarity of the processes summarized in Table 9.1, following the coming together of groups g, h and i between Figs. 35 and 38, breaks down at Fig. 38, which marks a point of formal division in the movement. This point, and its difference to what has come before, is defined by the brief return to the opening material of the movement (see Table 9.1 (group a) and Ex. 9.8(a)). The return of this material is obvious. However, although this return is quite literal it is not complete, using only the first two bars of what was a larger melodic statement. It does not therefore signify a return to beginning as a moment of recapitulation but rather announces the start of another process of fragmentation and juxtaposition that does not follow the sequence of events established at the outset of the movement. This highly truncated version of instrumental group a and its material overlaps with group d (timpani and piano) and is followed in a sharp, abrupt juxtaposition with group e (oboe, cor anglais, bassoon, contrabassoon). This process of juxtaposing and superimposing fragments of the now familiar sonorities and material continues and intensifies throughout the remainder of the movement resulting in increasingly dense and complex textures. Of course, this could be a process without end; with such juxtaposition potentially endless the outcome is an essentially non-, or anti-, teleological formal structure. The moment of ending, not closure, is therefore somewhat arbitrary. When it comes it does so in the shape of another partial articulation of the opening gesture of the movement (see Table 9.1 (group a) and Ex. 9.8 (a)). It now feels as if it is suspended in midair, with the pitches held over as if still seeking some sense of resolution that can never come (see Ex. 9.9). The inconclusive nature of this ending is repeated at the end of the final movement, with sustained pitches (B♭ and E) contained within a diminuendo gesture that gives the impression of the music fading away to silence.

Ex. 9.9 Concerto for Orchestra, first movement, ending

The importance of contrast within the first movement can be extended to include the contrast between movements. Within the expectations of the genre contrast from one movement to the next is usually realized. However, the contrast between the first and second movements of the Concerto for Orchestra is more than just contrast of tempo and character. The central slow movement defines its difference to what has come before through the introduction of the strings and their domination of the sound of this music, with piano and harp being the only other instruments involved. As no string instruments have participated in the various instrumental groups of the first movement the power of contrast is assured. However, it is not a full body of strings as in a standard symphony orchestra, but a reduced force that again breaks down into specific combinations. This string sonority articulates another of Tippett’s long melodic lines, what Kemp effectively describes as ‘one long, continuous melodic line’ that is ‘very human music’.34 Although this is a highly appropriate account of what we hear in terms of a melodic line that is yet another suggestive hint of Tippett’s lyrical gestures from his earlier music, Kemp does not really define what he means by a ‘very human music’. But it may signify the vocal quality of melody, the instrumental song that has already been mentioned as a key characteristic of Tippett’s slow movements. Contrast is again generated by the move from second to third movement, with the final movement returning to a fast, assertive sound that utilizes juxtaposition of instrumental textures and which is based in part on material derived directly from King Priam.35

Triple Concerto for Violin, Viola, Cello and Orchestra

The Triple Concerto for Violin, Viola, Cello and Orchestra was composed between 1978 and 1979 and was first performed in 1980. It is therefore contemporary with the Fourth Symphony (1976–7) and Fourth String Quartet (1977–8) and forms part of Tippett’s late, final period of creative activity.

In his ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ essay Tippett articulated the problems he encountered in attempting to renew the concerto and, as we have already seen, his lack of instinctive sympathy for what he describes as the ‘late Romantic confrontation of soloist and orchestra’.36 In contrast to the perceived predictability of this ‘confrontation’ Tippett was more interested in ‘the idea of using more than one soloist’,37 an interest that relates back to the Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli but also to the instrumental groupings of the first movement of the Concerto for Orchestra. The decision to have three solo instrumental parts may suggest that Beethoven’s Triple Concerto acted as a historical precedent and model for Tippett. However, in Beethoven’s Triple Concerto the three solo parts are that of the piano trio (piano, violin, cello), an already formed, recognizable chamber music grouping. For Tippett his three solo parts – violin, viola, cello – were not a string trio as such (‘the three players were to be real soloists, not a chamber music ensemble’38), and in part reflected his experience of works such as Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, which features violin and viola solo parts, and Brahms’s Double Concerto for violin, cello and orchestra. The other significant, formative factor in the Triple Concerto was provided by Tippett’s experience of visiting Java and Bali shortly before commencing work on the concerto and the experience of hearing live performances of gamelan music, which is reflected in specific, primarily percussive, instrumental sonorities in the work.

Tippett’s Triple Concerto consists of three movements, which suggests the historical archetype of the concerto genre, but they are linked by two interludes into a continually unfolding work. This concern with connection is also evident in the Fourth String Quartet and the Fourth Symphony, with all three late works reflecting what Kemp defines as the ‘cyclic archetype’,39 in that each work features linking of sections, or movements, into an unfolding whole while also being concerned with a metaphorical cycle; in the case of the Triple Concerto that cycle is described as ‘a natural cycle from one day to the next’,40 although it is perhaps difficult to always hear the formal and thematic processes of the work as leading inevitably towards interpretation via that particular metaphor.

The Triple Concerto begins with a brief orchestral introduction based on E as its point of harmonic focus, which will also act as the concluding harmonic centre of the work. This is quickly followed by the introduction of the solo viola at Fig. 1. As well as introducing the viola as an individual ‘voice’, this is also the point at which Tippett introduces an inconspicuous descending motive that will gain in significance as the work progresses.41 It is notable that the initial expositional moments of the concerto feature each of the three solo instruments as individuals rather than in dialogue or as a group, with Tippett’s description of this beginning as a sequence of ‘three cadenzas’ accurately reflected in what we hear in the music.42 The first point at which they come together occurs at Fig. 6 (see Ex. 9.10) which is also a direct reference to a key moment in the Fourth String Quartet (Fig. 124 of the quartet), with this reference to the quartet being an intentional strategy on Tippett’s part and one which he draws attention to in his ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ essay.43 For Tippett this becomes a very important passage in the Triple Concerto. It comes again towards the end of the first movement (Fig. 57) and returns towards the end of the concerto (Fig. 155) in order to signify ending through return to beginning, which does give some substance to the metaphorical description of the ‘natural cycle from one day to the next’.

Ex. 9.10 Triple Concerto, first movement, Fig. 6:1–4

Between this beginning and end of the work, and the cyclic process that connects them, the central slow movement provides the conceptual and musical core. Beginning at Fig. 79, this very slow, still texture is defined through an F major tonality. The theme played together by the solo violin, viola and cello (at Fig. 80) circles around the pitches of an F major triad – F, A and C – with B♭ added as a passing decoration (see Ex. 9.11). The sustained F as the harmonic bass supports this beautiful, lyrical theme. This material, both melodically and harmonically, could not be simpler. But the transparent simplicity of this moment not only provides a point of central contrast to the rest of the work, it also, more significantly, suggests a gesture of nostalgia through which Tippett looks back to his own earlier – tonally centred, thematically lyrical – musical language.

Ex. 9.11 Triple Concerto, first movement, Figs. 80–81:2

If this is the central point of the work it is not the only one to articulate such retrospection. In the second interlude, as preparation for the beginning of the third movement, Tippett quotes directly from The Midsummer Marriage. At Fig. 123 the solo violin part restates the theme from the conclusion of The Midsummer Marriage, also played by solo violin, which represents the ‘dawn chorus’ (Fig. 498 of the opera). For Clarke, through this quotation ‘the concerto stages a rapprochement with Tippett’s past’.44

In making these gestures towards Tippett’s own past the status of the Triple Concerto as a late work is confirmed, but they do not necessarily position it as a summation and nor do they in any way weaken the individual identity of this work. These moments of retrospection remind us of the plurality of Tippett’s musical world as, in the context of this discussion, defined through the intermittent but meaningful engagement with the concerto as a historical, generic archetype.

Notes

1 See , ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), pp. 89–108.

2 Ibid., p. 92.

3 Ibid.

4 However, more generally, Tippett remained highly ambivalent about the influence of Vaughan Williams. He declined the opportunity to study with the older composer while a student at the Royal College of Music and suggested a greater interest in the music of Holst. For some further commentary on Tippett’s relationship to the music of both Vaughan Williams and Holst see David Clarke, ‘“Only Half Rebelling”: Tonal Strategies, Folksong and “Englishness” in Tippett’s Concerto for Double String Orchestra’ in Clarke (ed.), Tippett Studies (Cambridge University Press, Reference Clarke1999), pp. 3–4; see also Tippett’s essay on Holst in Tippett on Music, pp. 73–5.

5 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 92.

6 Ibid.

7 In this chapter individual bar numbers are inserted only to aid discussion of specific points at the beginning of movements. Elsewhere references are based on the rehearsal numbers in the scores.

8 , Tippett: The Composer and his Music (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 139–40.

9 As cited in Clarke, ‘“Only Half Rebelling”’ in Clarke (ed.), Tippett Studies, p. 12.

10 , The Music of Britten and Tippett: Studies in Themes and Techniques, 2nd edn (Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 53–4.

11 Clarke, ‘“Only Half Rebelling”’ in Clarke (ed.), Tippett Studies, p. 20. Clarke also makes the point that while there are only two such examples of folksong models in the work, ‘many of its remaining thematic constituents are based on related melodic configurations, whose common source is the pentatonic scale’ (ibid.).

12 Kemp, Tippett, p. 143.

13 , CD liner notes to Tippett: Concerto for Double String Orchestra, Chandos (Chan 9409) (1995).

14 Clarke, ‘Between Hermeneutics and Formalism: The Lento from Tippett’s Concerto for Orchestra (Or: Music Analysis after Lawrence Kramer)’, Music Analysis, 30/2–3 (July/October Reference Clarke2011), 315.

15 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 101.

16 Cited in Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, p. 155.

17 Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, p. 153.

18 Cited in Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, p. 155.

19 Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, p. 158.

20 For an interesting perspective on decoration in this work see Kemp, Tippett, pp. 282–5.

21 Ibid., p. 322.

22 For further discussion of Tippett’s Second Symphony in relation to Stravinsky see my ‘Tippett’s Second Symphony, Stravinsky and the Language of Neoclassicism: Towards a Critical Framework’ in Clarke (ed.), Tippett Studies, pp. 78–94.

23 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 93.

24 Ibid., p. 94.

25 Whittall uses a similar labelling system to identify and define this material. See The Music of Britten and Tippett, pp. 194–6.

26 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 94.

27 Kemp, Tippett, p. 381.

28 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 94.

29 Kemp, Tippett, p. 380.

30 Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, p. 194.

31 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 94.

32 Kemp, Tippett, p. 381.

33 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 94.

34 Kemp, Tippett, p. 385.

35 For comments on the King Priam references see Kemp, Tippett, p. 385 and , Michael Tippett, 2nd edn (London: Robson Books, 1997), p. 178.

36 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 101.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Kemp, Tippett, p. 478.

40 Ibid.

41 For further analytical discussion of such details in this work see Stephen Collisson, ‘“Significant Gestures to the Past”: Formal Processes and Visionary Moments in Tippett’s Triple Concerto’ in Tippett Studies, pp. 145–65.

42 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 102.

43 See ibid., pp. 101–4.

44 , The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett: Modern Times and Metaphysics (Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 213.