Part I Contexts and concepts

1 Tippett and twentieth-century polarities

1998 and all that

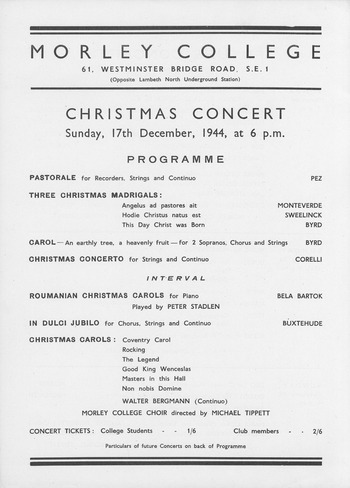

Michael Tippett’s death, on 8 January 1998, six days after his ninety-third birthday, came at a time when performers’ interest in his music was buoyant, and scholarly writing about his life and work was flourishing. A comprehensive collection of his own writings, Tippett on Music, appeared in 1995, the year of his ninetieth birthday, and this was soon followed by the second edition of Meirion Bowen’s relatively brief survey of his life and works (1997); then came Tippett Studies (edited by David Clarke) and Kenneth Gloag’s book on A Child of Our Time (both Reference Gloag1999), Clarke’s own monograph on The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett (Reference Clarke2001), and a further collection of essays, Michael Tippett: Music and Literature, edited by Suzanne Robinson (Reference Robinson2002).1 By then it was only three years to 2005 and the Tippett centenary, an event less well marked than it might have been had his death been less recent. The only major publication of that year was Thomas Schuttenhelm’s edition of Selected Letters, with its fervent prefatory declaration by David Matthews that Tippett ‘was such a central figure in our musical life that his absence is still strongly felt, not simply as a composer but as a man whose integrity and conviction were evident in everything he said and did’.2

Since then, there has been little or nothing. Performances and recordings have also tailed off, and it has not been difficult for those who sincerely believed that Tippett’s prominence in the last quarter-century of his life was more to do with the premature death of Benjamin Britten in 1976 than with the positive qualities of his actual compositions to declare ‘I told you so!’, and point to the contrast in the way in which ‘the Britten industry’ has continued to flourish.3 The argument that such speedy and summary dismissal bore out the verdict handed down by Robin Holloway in his brief obituary notice, where the ‘marvellous personal synthesis’ of the ‘two visionary song cycles, two masterpieces for string orchestra, the first two symphonies, The Midsummer Marriage’ was the prelude to ‘a long, slow decline’ in which ‘feckless eclecticism and reckless trendiness’ ruled,4 is less persuasive than it might be simply because of the melancholy fact that the earlier music has been sidelined as much as the later.

Consideration of possible reasons why the cultural practice of British music has evolved in the way it has between 1998 and today cannot sensibly be confined to statistical tabulations claiming to measure degrees of prominence and obscurity. It is nevertheless natural to speculate about whether some composers have a definable ‘staying power’ denied to others, and whether it is reasonable to consider ‘eclecticism and . . . trendiness’ as proof of ephemerality – at least when proven to be ‘feckless’ and ‘reckless’ respectively. Since this chapter is concerned, among other things, with arguing that Tippett is more properly considered in terms of dialogues between eclecticism and consistency, trendiness and ‘classic’ timelessness, it should be clear that I tend to the view that in his case recent neglect is not an infallible index of musical value, any more than it was for Sibelius in the first decades after his death in 1957. It follows that now is not the time to pursue a topic that needs a longer timeframe: so, rather than continue with the subject of ‘Tippett since his lifetime’ I will take a fresh look at the rich cultural practice of that lifetime, so nearly coinciding with the twentieth century, and explore Tippett’s relationship with that practice.

The background in outline

To list the British composers born between 1900 and 1914 is to establish a rough-and-ready context for Tippett himself (born in 1905) and for the century within which he and his contemporaries lived and worked. Born just before 1905, Alan Bush (1900–95), Gerald Finzi (1901–56), Edmund Rubbra (1901–86), William Walton (1902–83) and Lennox Berkeley (1903–89) were all involved to varying degrees with reinforcing rather than radically challenging the generic and stylistic predispositions of earlier generations. If – apart from Finzi – none of them could be thought of as essentially English in idiom after the model of Elgar, Vaughan Williams, or even Holst, their engagement with more radical (non-British) initiatives did not on the whole generate compositions as radically progressive as many in continental Europe or America before 1939.

Of those born alongside Tippett in 1905 itself, William Alwyn (d. 1985) would prove to be the most traditionally orientated symphonic composer of this vintage, while Alan Rawsthorne (d. 1971) would embody a more determinedly gritty reaction against what many perceived as the rather flabby effusions of Vaughan Williams or Arnold Bax. Likewise, both Walter Leigh (a casualty of the war in 1942) and Constant Lambert (who also died young, in 1951) found continental neoclassicism attractive as a means of evading the more pious and passive aspects of their national musical heritage – the kind of tensions Tippett himself would deal with so resourcefully during the 1930s and 1940s. (Lambert was also very perceptive about the significance of Sibelius in his book Music Ho! (1934)5 – but it was Walton’s music which grew closer to Sibelius’s during these years, not Lambert’s.)

Among composers born between 1906 and 1913 the only clear sign of those stronger disparities between radical and conservative which would define twentieth-century musical life and compositional practice is provided by Elisabeth Lutyens (1906–83); it would be another ten years before two other composers of comparable progressiveness, Humphrey Searle (1915–82) and Denis ApIvor (1916–2004), came along. Nevertheless, while Arnold Cooke (1906–2005), Grace Williams (1906–77), William Wordsworth (1908–88), Robin Orr (1909–2006), Stanley Bate (1911–59), Daniel Jones (1912–93) and George Lloyd (1913–98) were all in their different and in some cases quite distinctive ways on the conservative end of the formal and stylistic spectrum, Elizabeth Maconchy (1907–94) would show particular skill in crafting a progressive path leading closer to Bartók as model than to her teacher Vaughan Williams, and by this means to a kind of ‘mainstream’ engagement with modernism after 1950 that was as personable as Tippett’s own. By the early 1930s, of course, it was Benjamin Britten (1913–76) who was the most promising and successful exponent of mainstream progressiveness, his various ‘continental’ affinities – Mahler, Berg, Ravel, Stravinsky, Prokofiev – and the internationalist sympathies of his most important teacher, Frank Bridge, proving no hindrance to the rapid forging of a well-integrated personal language.

Britten was a challenge to those like Tippett, Rawsthorne and Maconchy who might have had comparable instincts and ambitions in relation to the British inheritance as it seemed to define itself after the watershed year of 1934, when Elgar, Delius and Holst all died. Tippett may never have been likely to strive for a less explicitly mainstream stylistic and technical amalgam than that which Britten was deploying to such effect immediately after 1935, but he seems gradually to have defined his own relation to the established and emerging polarities between radical and conservative in ways which reinforced the differences between his own personal compositional voice and that of his contemporaries, especially Britten. Nowhere was the contrast between Britten’s economical intensity and Tippett’s more flamboyantly decorative idiom greater than in two compositions written for Peter Pears and Britten to perform – Britten’sSeven Sonnets of Michelangelo (1940) and Tippett’s Boyhood’s End (1943). By the mid-1950s, with the first performances of The Turn of the Screw (1954) and The Midsummer Marriage (1955), the contrast in opera was even more apparent: and contrast remained of the essence, as Tippett’s dedication of his notably progressive Concerto for Orchestra to Britten in 1963 was complemented the following year by Britten’s dedication to Tippett of one of his most intensely constrained later works, the first parable for church performance, Curlew River.

In the years immediately after 1945, it was evident that British musical life was robust enough to sustain a diversity of styles, embracing Vaughan Williams, Britten and a younger, more internationalist figure like Peter Racine Fricker (1920–90), who, together with others born during the 1920s, including Malcolm Arnold (1921–2006), Robert Simpson (1921–97), Kenneth Leighton (1929–88) and Alun Hoddinott (1929–2008), bridged the divide between the 1900–14 generation and the new radicals born in the 1930s – Alexander Goehr (b. 1932), Peter Maxwell Davies (b. 1934), Harrison Birtwistle (b. 1934) and Jonathan Harvey (b. 1939). It was from within this pluralism that Tippett emerged as something more than just another distinctively English composer born in the years between 1900 and 1914. Yet it was only with Britten’s premature death in 1976 that he achieved the unambiguous prominence of a leader within a spectrum of compositional activity in which the generation of the 1930s was in turn finding itself complemented by younger minimalists – John Tavener (b. 1944) and Michael Nyman (b. 1944) – and those more conservative (Robin Holloway, b. 1943) and more radical (Brian Ferneyhough, b. 1943). This context of supreme heterogeneity suited Tippett’s own probingly pragmatic aesthetic, as well as his consistently internationalist outlook.

Interactive oppositions

There is perhaps more than a touch of irony in the fact that, had Tippett died at Britten’s age of (barely) 63 – in 1968 – he would be seen in terms of a career that ended with one of his most demanding scores, The Vision of Saint Augustine (1963–5), a work which showed him beginning to reassert his belief in the positively visionary – and blues-healing – nature of music after the upheavals occasioned by the stark tragedy shown in the opera King Priam (1958–61). As it was, Tippett survived and prospered for thirty years after 1968, and David Clarke encapsulated that near-century of life with admirable percipience in 2001, declaring that ‘one result of his longevity was an engagement with the radically different social and cultural climates across the century, particularly reflected in a dramatic, modernist change of style in the 1960s’.6 That ‘engagement’ with radical difference is also a crucial theme in Clarke’s book of the same year, the most penetrating and far-reaching critical study of the composer yet published, whose blurb sonorously declares that ‘Tippett’s complex creative imagination’ involves a ‘dialogue between a romantic’s aspirations to the ideal and absolute, and a modernist’s sceptical realism’. The book itself ends with the declaration that ‘Tippett’s is a music that contains a continuing and salutary reminder to face up to contradictions and to keep our minds and imaginations open’.7 ‘Contradictions’ can be another term for ‘polarities’, and facing up to them realistically, as they are, is a clear alternative to seeking compromise. If fusing – integrating – rather than merely balancing out the opposites is the most fundamental quality of a classicist aesthetic, then maintaining, even revelling in the persistent polarity of centrifugal superimpositions would seem to be the essence of modernism, celebrating twentieth-century culture’s distinctive embrace of fragmentation, stratification and disparity.

For some commentators, the pursuit of fragmentation and juxtaposition, at the expense of unity and connectedness, amounts to something ‘post-modern’ – especially when materials and stylistic associations with ‘pre-modern’ art materials are involved. While it is a symptom of current terminological diversity to note that what, for some, is ‘post-modern’ is, for others, ‘late modernist’, there is still likely to be broad agreement that the stylistic heterogeneity this kind of music displays demonstrates the willingness of the composer in question to challenge conventional concepts of stylistic consistency and ‘integrity’. Such issues became very relevant to Tippett’s later compositions. Indeed, of all the images that have clung to him, that of the magpie maverick is probably the most persistent. It allows for Robin Holloway’s pejoratively slanted ‘eclecticism’ as well as Clarke’s more positive ‘empiricism’;8 but, more importantly, it lays the foundations for a productive dialogue between the ‘formative’ and the ‘found’ – something whose varied manifestations helped to determine the Tippett ethos and the Tippett idiom. Since for Tippett the found – from spirituals and blues to Renaissance polyphony and the music of Beethoven or Schubert – tends to be tonal, and the formative to question the basics of tonality as much as to reinscribe them, it is by means of such very basic binary oppositions – or complements – that a critical and theoretical context for the informed reception of Tippett’s compositions in terms of meaningfully deployed polarities has been forged.

Tonality and polarity: a theoretical interlude

In the Poetics of Music lectures delivered by Igor Stravinsky at Harvard University in 1939 there is a straightforward statement showing how thinking about tonality had evolved since the earliest, nineteenth-century attempts to systematize those processes which were primarily concerned to enrich (if also to undermine) the essential stability of ‘classical’ diatonicism: ‘our chief concern is not so much what is known as tonality as what one might term the polar attraction of sound, of an interval, or even of a complex of tones . . . In view of the fact that our poles of attraction are no longer within the closed system which was the diatonic system, we can bring the poles together without being compelled to conform to the exigencies of tonality.’9

Had the great twentieth-century theorist of classical tonality, Heinrich Schenker, still been alive to read those comments they would have reinforced his conviction that Stravinsky was a destroyer of music’s most fundamental, most natural materials, not a real composer at all.10 However, by the 1930s such anti-progressive views were far less salient than the more enlightened and progressive understanding of post-Beethovenian processes of change found in such prominent twentieth-century composer-theorists as Vincent d’Indy, Paul Hindemith and Arnold Schoenberg.11 Indeed, despite the obvious and strong contrasts in style between Schoenberg and Stravinsky during the inter-war decades, the ideas about tonal harmony set out in The Poetics of Music demonstrate considerable convergence with Schoenbergian beliefs about the need to retain tonality as a flexible conceptual basis for meaningful composition, and to reject the wholly negative concept of ‘atonality’. In his Harmonielehre, Schoenberg had forcefully declared that ‘a piece of music will always have to be tonal, at least in so far as a relation has to exist from tone to tone by virtue of which the tones, placed next to or above one another, yield a perceptible continuity. The tonality itself may perhaps be neither perceptible nor provable . . . Nevertheless, to call any relation of tones atonal is just as far-fetched as it would be to designate a relation of colours aspectral . . . If one insists on looking for a name, “polytonal” or “pantonal” could be considered.’12

Music theorists have not been slow to seize on the implications of these statements and to try to tease out the terminological and technical consequences of regarding ‘polar attraction’ as a factor in the establishment of ‘pantonality’ or – alternatively – ‘suspended tonality’.13 For Tippett, who responded to and wrote about both Stravinsky and Schoenberg,14 the possibility that they might have significant similarities as well as essential differences could have been part of the attraction to an aesthetic instinct that acknowledged and worked with the tensions between two very fundamental artistic categories – classicism and modernism – both of which were accessible by way of the kind of thinking about harmony and principles of formation that the views on tonality of Stravinsky and Schoenberg exemplified.

Classicism, modernism, modern classicism

When work on The Midsummer Marriage was drawing to a close, Tippett wrote that he considered ‘the general classicizing tendency of our day [the 1930s and 40s] less as evidence of a new classic period than as a fresh endeavour . . . to contain and clarify inchoate material. We must both submit to the overwhelming experience and clarify it into a magical unity. In the event, sometimes Dionysus wins, sometimes Apollo.’15 The blithe self-confidence of this declaration is very much of a piece with the thumpingly upbeat tone of the Yeats couplet that ends the opera’s text – ‘All things fall and are built again, and those that build them again are gay’ – and it strongly suggests that any possible confrontation between such ‘classicizing’ and Schoenbergian modernism (which around 1950 meant, essentially, ‘atonal’ twelve-tone technique) was of much less significance than a continuingly productive contest between Dionysian romanticism and Apollonian classicism.

Such formulations reflect the general reluctance before the mid-1950s – particularly strong in British music – to follow through on the consequences of the expressionist, avant-garde initiatives, primarily in Schoenberg and Webern, which had emerged before 1914. These initiatives had been countered in the years after the First World War by a neoclassicism much more far-reaching than that developed by Stravinsky alone (it can also be traced in such twelve-tone exercises as Schoenberg’s Third and Fourth String Quartets). In addition, many of the most established and successful composers of the time – seniors like Richard Strauss, Sibelius and Janáček (even if his music was much less well-known until the second half of the century), the younger generation around Bartók, Hindemith and Prokofiev, and juniors like Britten and Shostakovich – refused to embrace fully that ‘emancipation of the dissonance’ which, coupled with resistance to harmonic centredness, was proving to be the most fundamental strategy in modernism’s principled resistance to classicism’s dissonance-resolving, unity-prioritizing qualities. While it is true that these composers often adopted harmonic characteristics that replaced simple major and minor triads with less standard chordal formations, such characteristics did not require the complete abandonment of degrees of relative consonance and dissonance, any more than the textures in which they appeared required the rejection of all points of contact with harmonic and contrapuntal techniques that had flourished in the time of diatonicism – the kind of chords, like those with which Tippett ended his First String Quartet (1934–5, rev. 1943) (Ex. 1.1), that are sometimes termed ‘higher consonances’.16 This ending is not a ‘perfect cadence’ in A major of the precise, traditional kind, but its relationship with such a cadence is unambiguous and depends for its meaning and function on recognition of that relationship.

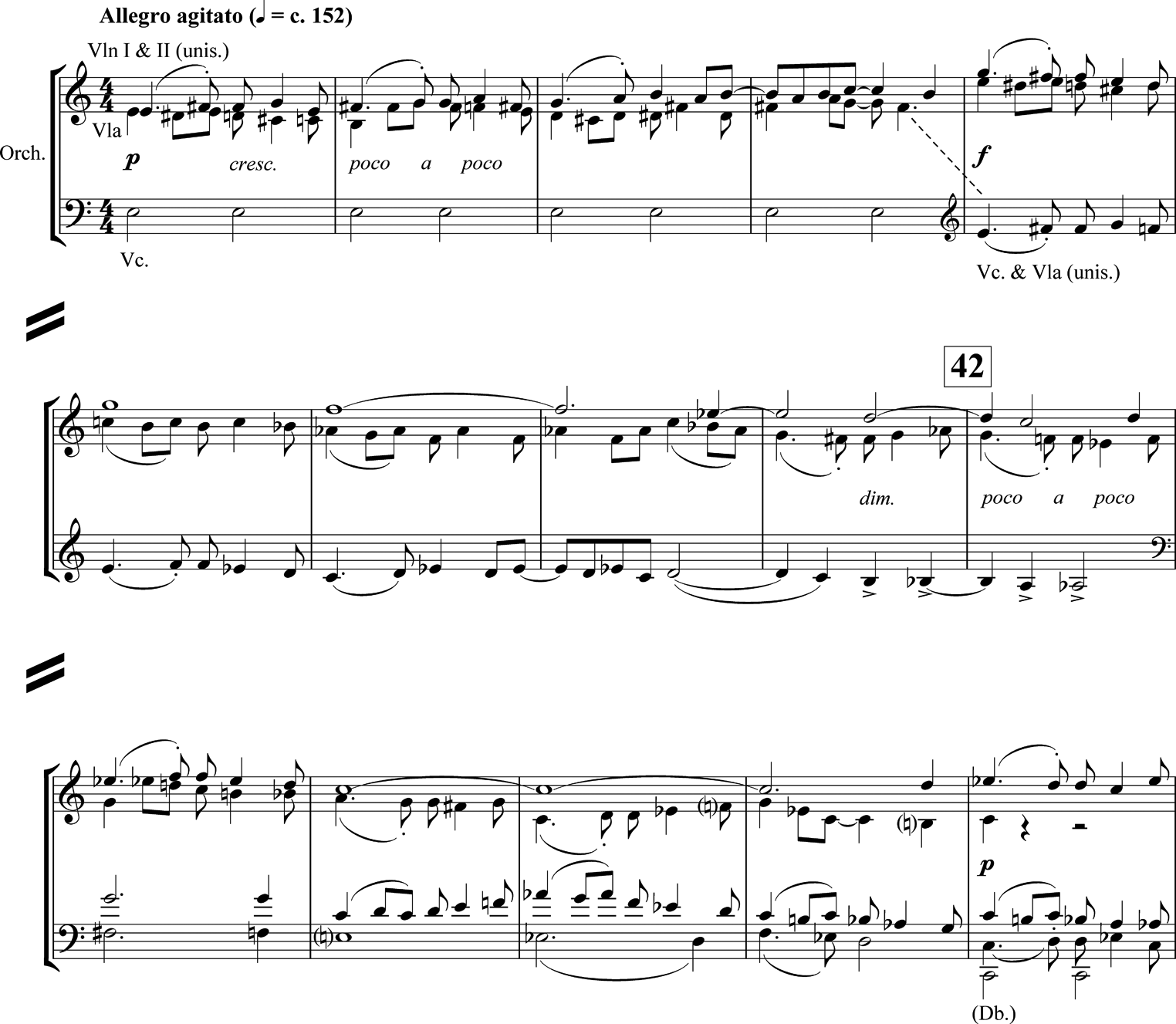

Ex. 1.1 String Quartet No. 1, third movement, ending

Tippett might well have been prepared to concede that the kind of unsparingly sordid modern expression found in Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck (1914–22) could provide a humanly compassionate as well as psychologically penetrating experience, thereby to a degree cathartically transcending the unrelievedly tragic aura of its subject matter. But he himself needed a stronger degree of idealism, and he was never more determined than in his early years to equate the musical representation of the visionary, the transcendent, with the triumphantly ‘cohesive . . . mingling of disparate ingredients’ he admired in Holst, and (eventually) in Ives: in both Holst’sThe Hymn of Jesus and Ives’s Fourth Symphony, he would eventually argue, ‘the constituent elements and methods may be disparate, but their essence is one of distillation’.17Berg might have been a master when it came to distillations of the disparate, but a modernism that downplayed the cohesive – the aspiration to renewal that was also an advance socially, politically and culturally – was initially far less appealing to Tippett than an aesthetic that retained enough of classical and romantic qualities to give space to his sense of how the modern world of the 1930s and 1940s needed to evolve if its political and spiritual crises were not to prove terminally destructive.

The heady mix of Marxist political progressiveness and Jungian psychological self-exploration, so typical of the 1930s, fuelled Tippett’s conviction that the ‘everyday’ world in itself was an inadequate environment for properly aspirational and inspiring art. Even Stravinsky’sThe Rite of Spring had to be seen as something other than an unsparingly vivid portrait of human cruelty and social repression: it was ‘a drama of renewal’, and ‘deadly serious’ as such.18 But even if the cultural climate of the years between 1920 and 1945 did little to promote the positive qualities of an absolute, avant-garde rejection of tonality and traditional formal models (hence the strong admiration of the Mahler-worshipping Britten for Berg’s Bach-quoting, Bach-subverting Violin Concerto of 1935),19 it did allow for the kind of more mainstream modernism that worked with a heady blend of celebration and subversion to bring elements of traditional aesthetics and compositional technique into a newer world of scepticism and potential fragmentation – a world in which the belief that ‘renewal’ was a wholly positive and realistic proposition was countered, if not actually contradicted.

Precarious balances: before 1945

In British music of the inter-war decades the kind of deconstructive response to Purcellian counterpoint found in Elisabeth Lutyens’sFive-Part Fantasia for Strings (1937) was a rare and flawed attempt at truly radical reappraisal of ‘classical’ traditions.20 Nevertheless, as the recent studies of Vaughan Williams’s Third (Pastoral) and Fourth Symphonies by Daniel Grimley and J. P. E. Harper-Scott have argued, even in a music that remained ‘classical rather than modern’, a deeply rooted ‘mingling of classical and modernist processes’ could function effectively.21 Most significantly, despite its relatively unprogressive kind of extended tonality, Vaughan Williams’sPastoral Symphony (completed in 1921) was able to project an unusual degree of ambivalence in reaching back to the remembered horrors of the First World War with something of a ‘nihilist’ trajectory, offering ‘a complex and often fractured vision’ in place of a ‘magical unity’.22 It was Tippett’s resistance to such nihilism which did most to determine the relatively traditional style of his music up to A Child of Our Time (1939–41) – his own first, mature attempt at ‘a drama of renewal’ in which the very immediate evidence of human weakness and social cruelty is distanced and ritualized, the work of art offering spiritual consolation or psychotherapeutic counselling as well as political instruction.

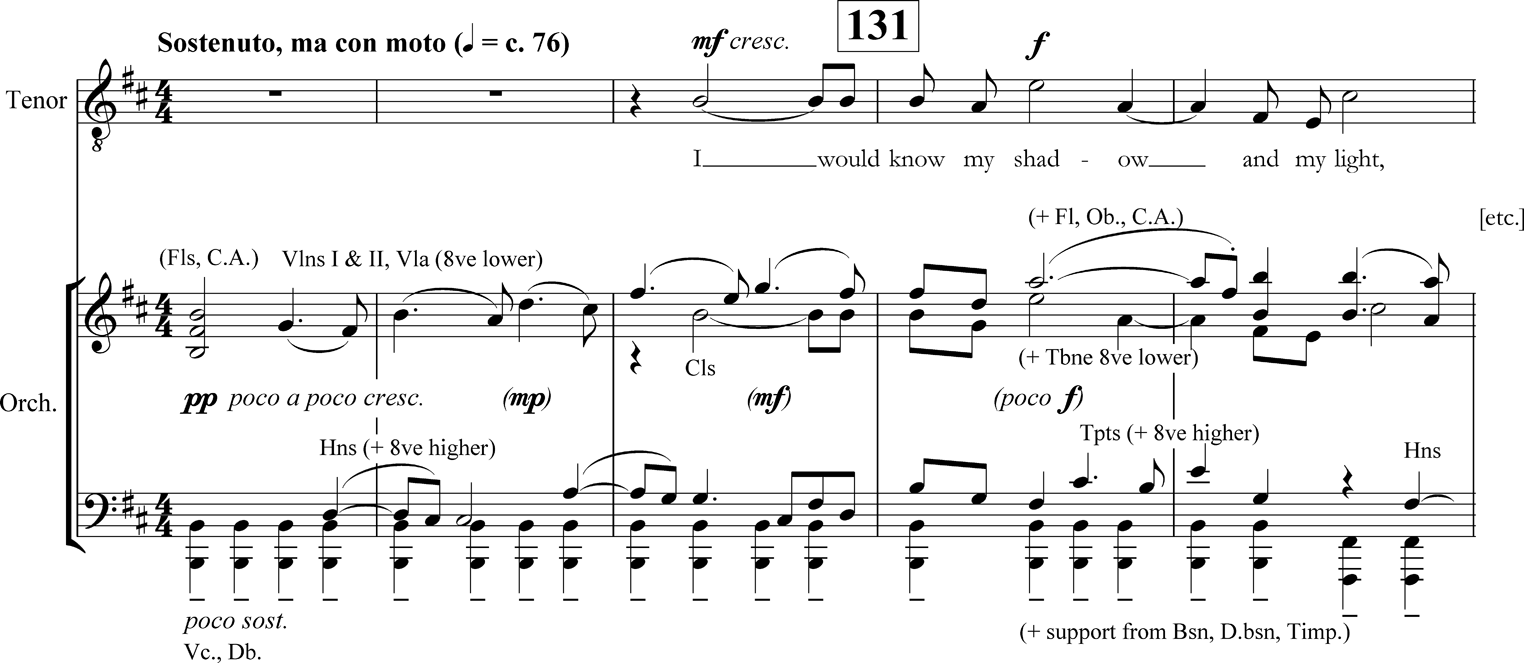

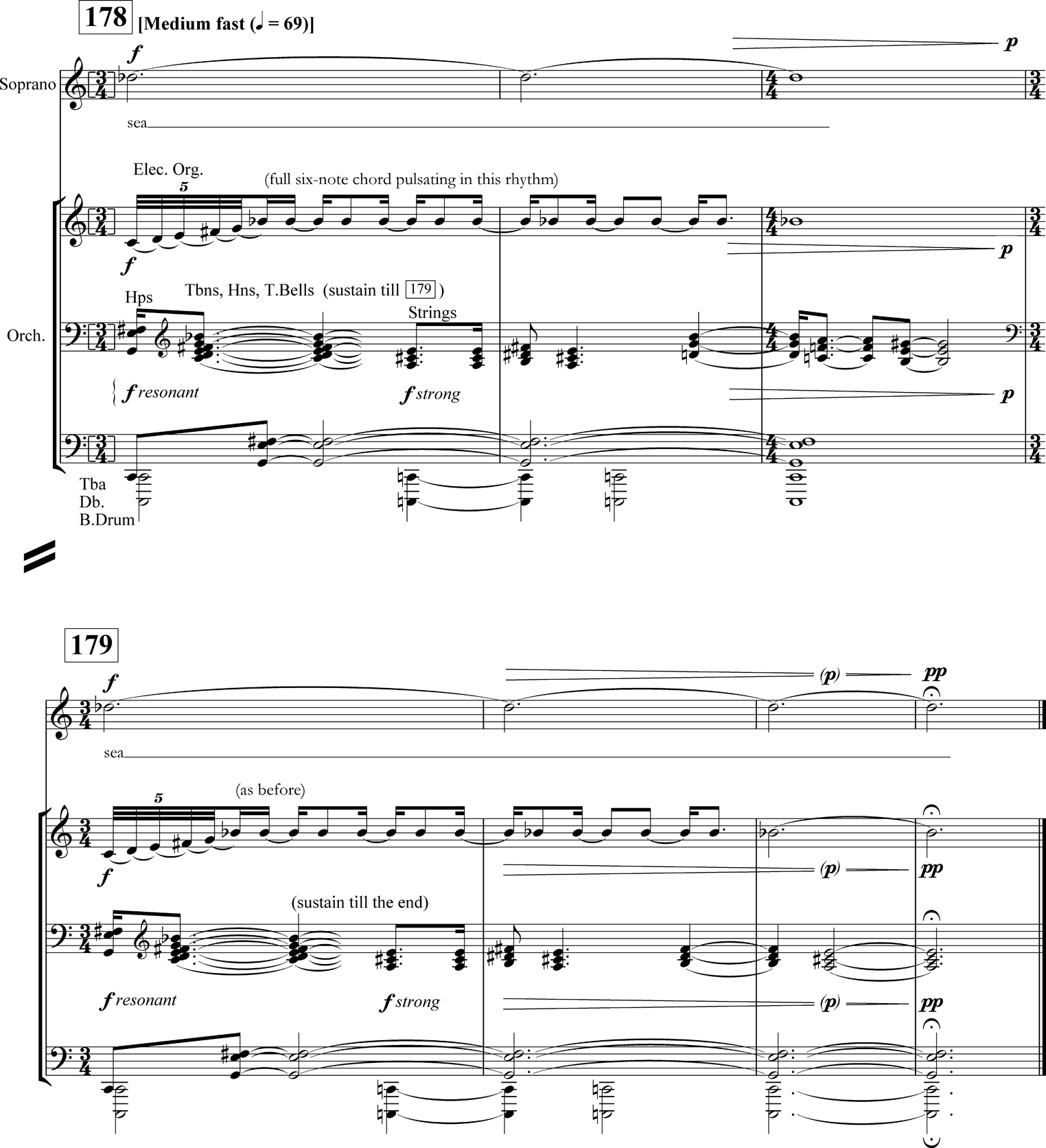

A Child of Our Time does not work as a productive dialogue between old and new, classical and modern, sacred and secular. If anything, it seems more concerned with failures of communication, and with disparities that can be lived with, accommodated, as long as they do not seriously inhibit that natural process of resistance to annihilation (and therefore of healing, renewal) that underpins the drama. Undoubtedly, pious aspirations to ‘know one’s shadow and one’s light’ as a sure means of effecting personal wellbeing are the most dated, least convincing aspect of the work from a twenty-first-century perspective. Because the continuing status of Jung is as problematic and unresolved an issue as the continuing status of Karl Marx, A Child of Our Time might be more of a problem piece today than it was in the 1940s. But it served the important purpose, for Tippett, of making him wary of using musical materials – the spirituals – whose social, religious function was so unambiguously explicit, so profoundly at odds with the more innately aesthetic purposes of art. When, at the end of The Midsummer Marriage, he alludes to a (purely instrumental) hymn-like chorale the atmosphere is perfectly poised between the ironic and the elevated, refining rather than simply underlining the ritualized collectivity of the generic association. And A Child of Our Time itself is redeemed aesthetically, to a degree, by the downbeat austerity of the way its concluding spiritual, ‘Deep River’, fades away (Ex. 1.2). The build-up of affirmative regeneration, the ‘rite of spring’ that precedes it, is countered, not transcended or given emphatic closure, and the fact that Tippett never seems to have considered bringing back the soaringly upbeat music which begins the finale (No. 29: Ex. 1.3) to round off and resolve the work as a whole leaves it polarized between two very different expressions of hopefulness in a way that not only seems relevant to the zeitgeist of 1941, but also lays a foundation for the methods Tippett would later employ to intensify the representation of polarities.

Ex. 1.2 A Child of Our Time, No. 30, chorus and soli, ‘Deep River’, ending

Ex. 1.3 A Child of Our Time, No. 29, chorus and soli, ‘I would know my shadow and my light’, opening

Precarious balances: after the war

As I have argued elsewhere, by the time he came to compose the ending of The Midsummer Marriage, Tippett was capable of ‘refining and intensifying the work’s dramatic themes without dissolving all traces of darkness, or even of scepticism’ – despite that Yeatsian textual assertion about ‘all things’ being ‘built again’.23 To this extent, Tippett was already on the road that would lead, in his late Yeats setting Byzantium, to the use ‘of symbol and myth to further the process of human self-understanding in a far more sceptical, circumspect and (on the face of it) realistic manner’ than in the opera.24 Arguably, however, that journey took the form and character it did in part at least because of being rooted so firmly in the relatively unambiguous classical ideals of his earlier years – ideals that remained conspicuous in the works composed immediately after The Midsummer Marriage – the Piano Concerto (1953–5) and the Symphony No. 2 (1956–7). The continued presence of a Stravinskian aura in the symphony has often been highlighted, and in 1999 Kenneth Gloag added a distinctive gloss on the music’s modern classicism – or ‘classicised modernism’ – in aligning his own analysis of it with Stephen Walsh’s comments on Stravinsky’s Concerto for Two Pianos: ‘here Stravinsky seems less and less to be confronting us with the irreconcilable nature of classicism and modernism and more and more to be synthesising a sort of personal classicism out of precisely their reconciliation’. As a result, ‘neo-classicism dissolves into a classicised modernism’,25 and Gloag surveys a range of analytical attempts to interpret Tippett’s version of ‘classicised modernism’ in terms of polarities or oppositions whose potential for reconciliation was clearly a vital aesthetic issue for him.

Remaining faithful to Tippett’s aesthetic instincts has required commentators to acknowledge his commitment to ‘fusion’. Elliott Carter once famously acclaimed Stravinsky for his mastery of the paradoxical yet supremely contemporary technique of ‘unified fragmentation’, in keeping with his ‘classicising’ declaration that ‘music gains its strength in the measure that it does not succumb to the seductions of variety’.26 Yet it seems to have been exactly this commitment to connectedness that Tippett came to challenge as he moved from the Second Symphony to its immediate successor, the opera King Priam. If the Stravinskian equivalent is that most potent of Greek tragedies, Oedipus Rex, the composer’s claim that he had assembled the work ‘from whatever came to hand’, making ‘these bits and snatches my own, I think, and of them a unity’ might lie behind Ian Kemp’s suggestion that Tippett’s opera offers a ‘unity of pluralities’.27 My own 1995 gloss on Kemp’s conclusion was to suggest that ‘as a post-romantic modernist, Tippett is led to problematize the synthesis of old and new’, seeking out ‘the deep relationship between all the dualities’ and making musical drama out of a search whose successful conclusion cannot be taken for granted.28

A specific and very basic technical factor supported this conclusion: ‘the role Tippett assigned to the perfect fifth in a post-tonal context is the strongest evidence we have of his refusal to let irony and ambiguity destroy all optimism, all dreams of Utopia’29 – even when violence and death appear to sweep all before them, as in King Priam’s final stages. Focusing on the role of a particular ‘triadic’ formation – semitone plus perfect fourth (set-class [0,1,6]) – and its motivic, metaphoric significance in the opera, suggests an implicit contrast with those more directly tonal, fifth-based cadential triads central to Tippett’s earlier music: set-class [0,3,7] – the major or minor triad, as at the end of The Midsummer Marriage or (in a different formation) the Second Symphony; and set-class [0,2,7] – the major second plus perfect fourth – that ended the First String Quartet.30 It was polarities acknowledged yet questioned – challenged, rather than wholeheartedly embraced and underlined – that remained the core quality of Tippett’s gradual retreat from the possible extreme that the starkly dissonant, fractured conclusion of Priam and its satellite successor, the Piano Sonata No. 2 (1962), represented.

The centre under threat: after King Priam

In his later years Tippett admitted to being ‘unsettled’ by the presence of what he termed ‘solid cadences’ in ‘one or two’ of his ‘earlier pieces’.31 Nevertheless, the extremes of ‘unsolidity’ to be found in the dissolving endings of King Priam and the Piano Sonata No. 2 were even more unsettling, confirming his wariness that such musical metaphors for unsparing and unrelieved tragedy might constrain, or even lame, the expressive contours of music which sought to acknowledge the realities of a modernist cultural position while not completely abandoning the more affirmative elements endemic to classicism. As early as the sonata’s immediate successor, the Concerto for Orchestra (1962–3), his chosen conclusion, while avoiding any hint of higher consonance, seems to involve stopping in the middle of the rediscovery of rhythmically regular melodic counterpoint – a wholeheartedly traditional texture given fresh post-tonal perspectives, and expressively more Apollonian than Dionysian in its imposing gravity. If, here, ‘a romantic’s aspiration to the ideal’ is tempered, held at bay, the polar opposite – ‘a more sceptical realism’ – seems also to be in question. And even if the abrupt termination of the concerto’s mosaic design was as much to do with a looming performance deadline as with deep aesthetic pondering, it seems to have reinforced the creative self-confidence that, over the next decade or so, would see Tippett’s most ambitious and controversial solutions to the paradox of polarities that demanded to be connected even as their contrasts were most starkly delineated.

The Vision of Saint Augustine, following hard on the heels of the Concerto for Orchestra, might almost have been conceived as a direct response to the utterly dark moment of vision that Priam describes just before his death – a vision whose mysterious exaltedness has little of Utopian euphoria about it. But in The Vision of Saint Augustine the prophetic human voice – in awe of inaccessible transcendence, and glorying in nature rather than worshipping the image of some all-powerful divinity – links the post-tonal jubilation and awe-struck speech at the end of the work with the ‘floating’ final vision of Boyhood’s End – something whose triadic purity, Purcellian ornateness and ecstatic sensuality, coming so soon after the more brittle rhetoric of A Child of Our Time, seems perilously close to aesthetic escapism, fantasy divorced from rather than polarized against reality.

Twenty years after Boyhood’s End, jubilation was even more uninhibited, but reconciliation much harder to achieve. As David Clarke’s extended and complex analysis of The Vision of Saint Augustine argues, ‘the work in which he most relentlessly pursues the transcendental is also his most uncompromisingly modernist statement’, ‘the resistance of each section to synthesis’ being ‘a measure of the extent to which it offers itself to the transcendental’.32 In aligning modernism with the transcendent in this way, Tippett for once foregoes the more far-reaching polarities to which his usual texts, dramatic themes and compositional priorities accustomed him. Augustine’s visionary voice, even though alternating between the singular solo baritone and the collective choir, has a monolithic insistence that fixes it in its own time and yet distances it from those adumbrations of the twentieth century’s real world to which Tippett would return in his next pair of major works, the opera The Knot Garden (1966–9) and the Symphony No. 3 (1970–2).

Here the prophetic voice becomes more sharply delineated as Dionysian idealism resisting the kind of Apollonian sobriety heard at the end of the Concerto for Orchestra. The challenge, it might be thought, was to find a Dionysian rhetoric that did not float away into the clouds of Utopian fantasy, as idealism pure and simple, unchallenged and unrealistic. In The Knot Garden the freedom fighter Denise’s resistance to idyll, in a powerfully austere account of torture, sets up the kind of psychological nexus for the drama which Tippett would soon encapsulate in what he thought of as the Third Symphony’s confrontation between the diametrically opposed human attitudes of aggressiveness and sympathy – violence and compassion. In relation to the symphony, Tippett wrote eloquently of polarities as ‘fundamental to my temperament’: ‘I was living in the twentieth century, which had seen two world wars, numerous revolutions, the concentration camps, the Siberian camps, Hiroshima, Vietnam, and much else’, and this meant that ‘affirmation had to be balanced by irony . . . And at the very end, I wanted to preserve the underlying polarities, concentrating all the violence into strong, sharp, rather acid wind chords, but matching them with string chords, representing some kind of compassionate answer from behind.’33

Tippett’s resolutely non-technical language here has opened up a fathomless space in which commentator after commentator has attempted to specify exactly how ‘the underlying polarities’ result in particular pitches in particular registers. The first three ‘violent’ chords, alternating with the first three ‘compassionate’ chords, seem determined to suspend any clear-cut tonal character or direction, although each of them in different ways – and often because of the ‘perfect fifth with other intervals’ aspect of their construction – can be shown to anticipate the content of the decisive final pair (Ex. 1.4). Whether Tippett’s choice of C major and A major triads for the lowest pitches of these closing sonorities was a conscious allusion to the rich romantic tradition of third-related harmonic structures, to the idealistic yet uncertain juxtaposition of C major and A major at the end of The Midsummer Marriage (Ex. 1.5), or to these tonalities as standing for his First (A major) and Second (C major) Symphonies at the end of his Third can never be known; nor can we determine whether he saw the climactic, cadential fusion of the two in his late Yeats scena Byzantium (1989–90) (Ex. 1.6) as a decisively ambivalent image of the numinous for the modern(ist) age. Where the Third Symphony is concerned, the evolution of theoretical thinking over the past half-century might favour the argument that the suspension rather than elimination of these two tonalities stands as a metaphor for the conjunction of conflicting human attitudes – the violent and the compassionate – that Tippett’s own sense of the music’s most fundamental polarity provides. Whatever explanation is preferred, the evidence of the music Tippett composed after the Third Symphony is that the polarized imagery that stimulated his creative imagination – shadow and light, violence and compassion, scepticism and idealism, the humanly real and the transcendentally ideal – continued to lead him to dramatic themes, musical ideas and cadential conclusions that explored comparable elements and evoked comparable states of mind.

Ex. 1.4 Symphony No. 3, Part II, ending

Ex. 1.5 The Midsummer Marriage, Act 3, ending

Ex. 1.6 Byzantium, ending

Towards an ending: integrity and irony

Tippett’s poet-prophets would continue to embody the essence of that doubting visionary, represented most poignantly in his texts for the Third Symphony, who senses ‘a huge compassionate power to heal, to love’,34 and who is prevented from succumbing to sentimental self-indulgence by the abrasive environment in which she is obliged to function. Such issues also help to define the role of the exiled writer Lev in The Ice Break (1973–6), who achieves a fragile yet hopeful reconciliation with his son after the death of his wife, and also of the trainee children’s doctor Jo Ann in New Year (1986–8), whose experience of love leaves her feeling able to face a dangerous and probably hostile urban world for the first time.

The mix of fantasy and realism, the transcendental and the earthly, in both these operas might not have worn particularly well, if only because of the continued prominence of comparable dramatic themes in contemporary fiction and cinema. But Tippett made a still more ambitious foray into the mythologizing dramatization of the human condition in his third large-scale choral and orchestral composition, The Mask of Time (1980–2). The struggle in this turbulently energetic score to balance positive and negative, human and inhuman, compassion and violence, has been well summarized by David Clarke, writing of how ‘the sublimity of the final moments . . . asserts a transcendent humanity over negative experience through a partial assimilation of it . . . Here the sublime is used in a spirit that is essentially modernist, pointing forward to the possibility of a different order, and suggesting that for Tippett images of the visionary signify not escape into a different world, but a challenge to the existing one.’35 In 2002 I aligned this with Ian Kemp’s no-less-penetrating comments about Tippett’s personal brand of expressionism, which

is not a mere repeat of its early twentieth-century counterpart. It is not so self-sufficient, its terms of reference are wider and it neither wages war against a hostile world nor presumes that music can embrace the abstract essence of things by means of an ‘absolute’ metaphor. On the contrary, it seeks a covenant with real life and is always conditioned by Tippett’s preoccupation with the integration of the individual – the individual with himself, with others and with society at large. In addition, it is coloured by an irony which questions its whole basis.36

Together, these assessments convey much of what makes Tippett’s way with twentieth-century – and other – polarities difficult to pin down yet impossible to escape. He seems consistently to be seeking to celebrate something timeless, archetypal, and to combine it with something elusive, even ephemeral. At one extreme, the archetypal musical states of singing and dancing provide the perfectly balanced complementation from which a satisfying classical synthesis can be forged. At the other extreme, challenges to such idealized integration are shown to be the more effective as their disruptive, dissonant identities ironically absorb fundamentals from those very factors to which they are most productively hostile. Nowhere are these diverse balances shown to more powerful effect than in the last work in which Tippett alluded to his beloved A-centred harmony, the Fifth String Quartet (1990–1), the ending of which – quite unlike that of Tippett’s actual swansong, The Rose Lake (1991–3), which relishes making something downbeat and understated of something that is nevertheless decisively conclusive – discovers the ‘rich’ unanimity of this fifth-based higher consonance with a freshness that belies its deep roots in the composer’s past (Ex. 1.7).

Ex. 1.7 String Quartet No. 5, second movement, ending

In 1998 I interpreted this ending in terms of ‘the pervasive tensions and ambiguities of an idiom which has abandoned extended tonality for a harmonic world which is altogether more mobile, but in which there is still a polyphonic equality of line and a “classicising” use of repetition, imitation and sequence as the principal tools in the search for a sufficient closural stability . . . In late Tippett intensification does not secure a trouble-free stability. A sense of strain, doubt and openness remains, even though the prevailing mood is one of hope.’37

That element of ‘even though’ ambivalence is no less apparent in those later Tippett endings which require a sudden, unresolving shutting off of sound, as with The Mask of Time and New Year, where the upbeat but possibly over-optimistic tone of the Presenter’s final message – ‘one humanity, one justice’ – does not prompt an unambiguously affirmative musical coda. Rather, as I concluded in 1990 after seeing New Year’s British premiere:

the irresolvable tensions in Tippett’s music surely reflect the fact that even the most confidently integrated individual still has to function in a society that is likely to be notable for its lack of unanimity. It is characteristic of the essential honesty of Tippett’s continued desire to weld what he has termed the ‘marvellous’ and the ‘everyday’ into viable drama that, despite the happy ending, the sheer abruptness with which the music of New Year stops makes it clear how uncertain the future actually is.38

The archetypal blues

Having chosen a particular title, courtesy of Noel Coward, for his autobiography, Tippett brought its generic allusion to the surface in a final section headed ‘Singing the Blues’, in which he attributed two vital topics to LeRoi Jones’s book Blues People: Negro Music in White America:39 firstly, ‘the blues is the most fundamental musical form of our time’; and secondly, ‘when you sing the blues, you do so not just because you are “blue”, but to relieve the blue emotions. When I heard Noel Coward sing, “Those twentieth-century blues are getting me down” he sang because the blues were doing exactly that and the singing of them is his means of discharging their effect: simultaneous involvement and detachment, in other words – which is how artefacts are made.’40

Tippett was quite clear that his own objective was never simply to reproduce or imitate the jazz and popular derivatives of the blues: for him it was an ‘archetype’, reinforcing in a special, twentieth-century way the possibility that artefacts (like successful psychoanalysis) can purge the negative emotions of despair – along with the fear that comes from lack of self-awareness. Perhaps it is best to interpret his hyperbolic assertion that ‘the blues is the most fundamental musical form of our time’ as a declaration of his belief that it was the ‘musical form’ best suited to this therapeutic role – and certainly better suited than ‘Schoenberg’s twelve-note method’, with which he compares it, thereby failing to distinguish ‘method’ from ‘form’, or indeed to consider whether these two musical archetypes might not be complementary in their capacity for presenting extended tonal statements of great expressive intensity.

Tippett’s mindset in this autobiography reveals the persistence of his neo-romantic commitment to idealization, his need to be upbeat (however sceptically or insecurely), in ways which contrast notably with the capacity of more outright modernists like Carter and Boulez to avoid pessimistic despair without going beyond that into suggesting that music can actually purge pessimism and despair in a great, consolatory outpouring of ‘relieving’ emotional discharge. Tippett in this respect contrasts even more fundamentally with the thoroughgoing English late-modernism of a Harrison Birtwistle, for whom the purpose of music is to inspire, and therefore also to console, by the aesthetic, expressive strength and power with which it represents its own stark resistance to consolatory rhetoric. It is therefore no surprise that, to the end, Tippett would speak of ‘fusion’ as much as of ‘polarity’. In what Clarke defined as that ‘dialogue between a romantic’s aspiration to the ideal and absolute, and a modernist’s sceptical realism’, Tippett’s instinct was, by and large, to move the latter into the field of the former. In this way, his personal angle on twentieth-century polarities was unfailingly rich, challenging and memorable. As was said – presciently – of Sibelius in the 1960s: his time will surely come again.

Notes

1 , Tippett on Music, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995);, Michael Tippett, 1st edn (London: Robson Books, 1982), 2nd edn (London: Robson Books, 1997); (ed.), Tippett Studies (Cambridge University Press, 1999);, Tippett: A Child of Our Time (Cambridge University Press, 1999);, The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett: Modern Times and Metaphysics (Cambridge University Press, 2001); (ed.), Michael Tippett: Music and Literature (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002).

2 , Foreword to Thomas Schuttenhelm (ed.), The Selected Letters of Michael Tippett (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), p. xiv.

3 See , Selling Britten: Music and the Market Place (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

4 , On Music: Essays and Diversions (Brinkworth, Wilts: Claridge Press, 2003), pp. 241–2 (originally published in The Spectator, 31 January 1998).

5 , Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline (London: Faber and Faber, 1934), p. 264 .

6 , ‘Tippett, Sir Michael’ in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edn, ed. and (London: Macmillan, 2001), vol. xxv, p. 505.

7 Clarke, The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett, p. 269.

8 Clarke, ‘Tippett, Sir Michael’, p. 505.

9 , Poetics of Music (New York: Vintage, 1947), p. 39.

10 For Heinrich Schenker’s discussion of a fifteen-bar passage from Stravinsky’s Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1923–4), see ‘Further Consideration of the Urlinie II’ in The Masterwork in Music: A Yearbook, Volume 2 (1926), ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 17–18 .

11 ’s Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony) was first published in 1911 (Vienna; first Eng. trans. (New York: Philosophical Library, 1948)) . The four volumes of ’s Cours de composition musicale appeared between 1903 and 1950 (Paris; vol. iv ed. G. de Lioncourt). The two volumes of ’s Unterweisung im Tonsatz (The Craft of Musical Composition) were originally published in 1937 and 1939 (Mainz; Eng. trans. Arthur Mendel, vol. i (New York: Associated Musical Publishers; London: Schott & Co., 1942); Eng. trans. Otto Ortmann, vol. ii (New York: Associated Musical Publishers; London: Schott & Co., 1941).

12 , Theory of Harmony, trans. (London: Faber and Faber, 1978), p. 432.

13 On this topic see , ‘Suspended Tonalities in Schoenberg’s Twelve-Tone Compositions’, Journal of the Arnold Schoenberg Center, 3 (2001), 239–66 , and , Introduction to Serialism (Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 110–11.

14 See, for instance, Tippett’s pair of articles in Tippett on Music, pp. 25–46 (Schoenberg) and pp. 47–56 (Stravinsky).

15 Tippett, ‘The Midsummer Marriage’ in Tippett on Music, p. 208.

16 For further discussion of this term, see , The Music of Britten and Tippett: Studies in Themes and Techniques, 2nd edn (Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 5.

17 Tippett, ‘St Augustine and His Visions’ in Tippett on Music, p. 236.

18 Tippett, ‘Stravinsky and Les Noces’ in Tippett on Music, p. 51.

19 See (ed.), Journeying Boy: The Diaries of the Young Benjamin Britten 1928–1938 (London: Faber and Faber, 2009), pp. 348, 391, 393 .

20 See , ‘Early Music and the Ambivalent Origins of Elizabeth Lutyens’s Modernism’ in (ed.), British Music and Modernism 1895–1960 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), pp. 269–91 .

21 J. P. E. Harper-Scott, ‘Vaughan Williams’s Antic Symphony’ in British Music and Modernism, ibid., p. 187.

22 Daniel M. Grimley, ‘Landscape and Distance: Vaughan Williams, Modernism and the Symphonic Pastoral’ in British Music and Modernism, ibid., p. 174.

23 , ‘New Opera, Old Opera: Perspectives on Critical Interpretation’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 21/2 (July 2009), 193.

24 , ‘“Byzantium”: Tippett, Yeats and the Limitations of Affinity’, Music & Letters, 74/3 (August 1993), 398.

25 , The Music of Stravinsky (Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 175, as cited in Kenneth Gloag, ‘Tippett’s Second Symphony, Stravinsky and the Language of Neoclassicism: Towards a Critical Framework’ in Clarke (ed.), Tippett Studies, p. 93.

26 , ‘Igor Stravinsky, 1882–1971: Two Tributes’ in Elliott Carter: Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937–1995, ed. (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), p. 143; Stravinsky, Poetics of Music, p. 33.

27 and , Dialogues (London: Faber and Faber, 1982), p. 27 ; , Tippett: The Composer and his Music (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 340.

28 Arnold Whittall, ‘“Is There a Choice at All?” King Priam and Motives for Analysis’ in Clarke (ed.), Tippett Studies, p. 77; the reference is to ‘Too Many Choices’ in Tippett on Music, p. 296.

29 Whittall, ‘“Is There a Choice at All?”’, ibid.

30 For detailed information on pitch-class set theory, see , The Structure of Atonal Music (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1973) . Introductions to the subject can be found in , A Guide to Musical Analysis, pbk edn (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1989) , Ch. 4, and and , Music Analysis in Theory and Practice (London: Faber Music, 1988) , Ch. 12.

31 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, p. 101.

32 Clarke, The Music and Thought of Michael Tippett, pp. 126, 141.

33 Tippett, ‘Archetypes of Concert Music’ in Tippett on Music, pp. 96, 100.

34 Ibid., p. 99.

35 , ‘Visionary Images: Tippett’s Transcendental Aspirations’, Musical Times, 136 (January 1995), 21.

36 Kemp, Tippett, p. 402; Arnold Whittall, ‘Transcending Song: Tippett’s Play with Genre in Vocal Composition’ in Robinson (ed.), Michael Tippett: Music and Literature, p. 196.

37 , ‘Sir Michael Tippett 1905–98: Acts of Renewal’, Musical Times, 139 (March 1998), 9.

38 , ‘Facing an Uncertain Future’, The Times Literary Supplement, 13–17 July 1990, 755.

39 , Blues People: Negro Music in White America (New York: William Morrow, 1963) .

40 , Those Twentieth Century Blues (London: Hutchinson, 1991), pp. 274–5.

2 Tippett and the English traditions

Much in the complex, eclectic mix of Tippett’s artistic persona portrays an internationalist stance: his key musical exemplars were Stravinsky, Hindemith, Schoenberg (in terms of ideas if not, particularly, style), Ives and Beethoven; an important music-theoretical influence was Vincent d’Indy; politically, he aligned himself with the international left; key literary influences such as T. S. Eliot and George Bernard Shaw had overseas origins; later in life he developed a fascination for North American culture (including Black American popular music forms); he had a German publisher, Schott; and so on. He was also apparently concerned to distance himself from the preceding generation of English composers, viewing them (as did his contemporary, Benjamin Britten) as insular and amateurish. Yet he also exhibited traits that can be recognized as being in common with other English composers of the twentieth century and he actively engaged with English music of the Renaissance and baroque, especially the madrigalists and Purcell. Commencing with a discussion of what an ‘English tradition’ might mean in the twentieth century, this chapter focuses on Tippett’s indebtedness to English musical forms and procedures, highlighting in particular the role of ‘fantasy’ – an approach to musical thinking derived from Purcell and his Renaissance forebears that, I shall argue, informs Tippett’s output from the earliest of his acknowledged compositions through to the mosaic-based works of the sixties and seventies and beyond.

I

Let us first start with a dictionary’s definitions of ‘tradition’:

- 1:

a): an inherited, established, or customary pattern of thought, action, or behavior (as a religious practice or a social custom)

b): a belief or story or a body of stories relating to the past that are commonly accepted as historical though not verifiable

2: the handing down of information, beliefs, and customs by word of mouth or by example from one generation to another without written instruction

3: cultural continuity in social attitudes, customs, and institutions

4: characteristic manner, method, or style <in the best liberal tradition>.1

All four of these are relevant to musical tradition, which is a complex business with different types and sub-branches continually interacting. To take a relatively straightforward example: traditions of compositional practice normally arise reciprocally with traditions of performance, but while notations of the pitches and rhythms in the music of, say, Bach have remained more or less fixed (subject to generations of editorial interventions, which of course have their own traditions), ways of performing have changed markedly, leading in Bach’s case to a romantic style of performance in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (enshrined in the latter part of this period in recordings, but also in phrase and dynamic markings in many editions of his scores). In the second half of the twentieth century a burgeoning number of performers reacted against this romantic manner by making what they believed to be a reconnection with the lost performing tradition. But as Richard Taruskin has persuasively argued, this was subject no less to the (essentially modernist) ideology of the reconnectionists’ own time.2 The later volumes of Taruskin’s largest project, The Oxford History of Western Music,3 and more of his writings besides, are much concerned with the interrogation of assumed notions of tradition, and in particular the hegemonic value placed upon the Austro-German tradition and the distortions of Hegelian and neo-Hegelian historiography that sustain it.4 The constructedness of tradition is also emphasized by the historian Eric Hobsbawm through his notion of the ‘invented tradition’, which ‘is taken to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past. In fact, where possible, they normally attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past.’5 As we shall see, establishing continuity with ‘a suitable historic past’ was of some concern to the generations of English composers born in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth. Clearly, this chapter needs to try to identify whose ‘English tradition’ we are talking about, as well as interpreting what it consists of.

We might start by asking: what can be determined of Tippett’s notion of ‘tradition’ and, in particular, the ‘English tradition’? The word ‘tradition’ occurs a few times in his published writings and letters, though it has to be said that the composer does not always express himself with the greatest clarity, and a fair amount of speculation has to be employed in order to determine both localized meanings and what his overall view of tradition might be. One of the earliest occurrences of the word is in a letter to Francesca Allinson of March 1942. Tippett is initially concerned with some criticisms of his Fantasia on a Theme of Handel (1939–41), but he soon turns to tradition, suggesting this was very much on his mind when he was composing what might be called his breakthrough work, A Child of Our Time (1939–41), which is exactly contemporary with the Fantasia:

Your feeling that the work was Continental is really my feeling too. And I think it’s come for good. It’s a sort of growing up inside. And it goes hand in hand with my increasing knowledge of the English tradition! I think the oratorio [A Child of Our Time] will sound even more Continental too – the point is that the temper is of that order, irrespective of myself. I am quite happy about this, and indeed welcome it. Not but what the English ancestry is really there all the time – it’s the technical equipment that is growing intellectually maturer and consequently then English, as per Bax, V.W. [Vaughan Williams] and Ireland etc.6

What exactly does he mean by ‘English ancestry’ and ‘Continental’ approaches? The former almost certainly refers to Purcell and the earlier generations of composers including Orlando Gibbons and Thomas Morley, whose music he had been exploring since the early 1930s with the various choirs he conducted: in a letter to Alan Bush dated 6 February 1940 (two years earlier than the letter to Allinson) he states that ‘The recitative [in A Child of Our Time] in principle goes back to Lawes and Purcell.’7 Tippett began to explore his responses to Purcell in various BBC radio talks and programme notes during the 1940s and early 1950s, and I will discuss these further below.8 This is not to say, though, that the influence of more recent English composers is insignificant (as we shall see presently). And the English tradition was not the only one in play: in the same letter to Bush Tippett writes that ‘The question of assimilation of the “classical” tradition is the point I’ve just got to, having lived out the jejune romanticism of my adolescence.’9 This might suggest some kind of engagement with neoclassicism, which might be partly what he means by a ‘Continental’ feeling: he goes on to refer to A Child of Our Time as ‘Almost a resuscitation of a traditional form. There are choruses, arias, recitative (!) and chorale. It is only the content and one or two more subtle means of expression which are modern.’10 The oratorio genre, though, suggests more strongly an engagement with the English tradition that starts with Handel (who could be said to have been adopted by the English) and is then sustained by Mendelssohn and numerous minor composers (with performances at provincial festivals) through to Elgar and Walton (in the form of Belshazzar’s Feast (1930–1)). With Handel incorporating various aspects of Purcell’s style himself,11 the oratorio tradition could almost be seen as a thread of continuity from Purcell to Tippett. The point is, though, that Tippett sees a break in the tradition, such that it has to be ‘resuscitated’. Writing to Robert Ponsonby on 28 July 1972 about his (Tippett’s) ideas about British music, having declined to collaborate with Ponsonby on the 1974 Proms season (Ponsonby had just been appointed Director of the Proms), he says:

Might I suggest, however, since the matter of British music is in general very near my heart, that we have a talk about it over lunch, when you are settled in the south. I have ideas on this theme, that is, what kind of voice our national music is, at its best, and how it can find its true place in the general variety of our Western musical experience. I mean, why the Tallis 40-part motet is probably the most extraordinary piece of European music of its period; what can be successfully performed of Purcell in the concert hall; the real gap in the English tradition during the 18th and 19th centuries; why, at the return, Elgar is a creative genius and Bax is second rate; what is the core of Vaughan Williams? And earlier of Delius? And so on.12

The existence of the oratorio tradition and recent research into music in nineteenth-century Britain give the lie to this gap.13 What Tippett seems to have been latching onto, along with most composers, performers, historians and listeners (including the Germans who viewed Britain, famously, as Das Land ohne Musik), was the lack of composers of the front rank.

One of the most interesting of Tippett’s comments about tradition is to be found in another letter roughly contemporaneous with A Child of Our Time (actually written two years later, on 7 February 1943). This time the recipient is William Glock, and the subject is the promotion of ‘the moderns’:

I can’t help feeling what we want most is an artistically discriminate public somewhere, even if a small one, that has some sense of a much larger and more living tradition than the usual notion of a few great names down from which, as it were, we scale to the small fry. I am sure the way around is to have a sense of a tremendous tradition within which the great men are great; in part or virtue of which they are great. And when it comes to the moderns I just feel it’s impertinence on our part to try and ‘put them across’, like a disagreeable political policy. No – they are there, and praise heaven there are such active minds alive – let us be thankful for them and do our best to see what they are up to – their works will fall into place soon enough, and if they are of the true tradition, then they will ever so little alter our view of the whole mass of stuff gone before. Stravinsky, Hindemith, Bartók are all of this and I’m pretty certain to speak of the living. And each of them without exception has the strongest sense of tradition and the music of all sorts of pasts.14

Key in this is the notion of what Tippett calls ‘the true tradition’, the ‘whole mass of stuff’ which is constantly (if only ‘ever so little’) given new perspective by subsequent generations of composers. This reflects some comments made by T. S. Eliot (a significant influence on Tippett15) about tradition in his essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ published in 1919, which Tippett quotes in his article ‘Schoenberg’, first published in 1965, though it seems likely that he had come across it many years earlier: ‘The existing monuments [of art] form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new, the really new work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives. For order to persist out of the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered.’16 Glossing this, Tippett writes:

Eliot’s point is that the new and the old, the revolutionary and the traditional, is a two-way traffic. The old affects the new; that is obvious. But Eliot believed that what he calls the really new affects the old. If this is so, and leaving anti-art and Dada aside, then the really new works of art are only those by which our view of the whole pre-existing order of works of art is ever so slightly altered. The greatest works of Schoenberg and Stravinsky are in this category.17

If all this suggests that, for Tippett, a sense of tradition provided the means of ensuring coherence and meaningfulness in the face of the profusion of allusions which are part and parcel of his compositional approach from A Child of Our Time onwards, the evidence of his scores is that tradition was at least as importantly a straightforward matter of resource.

II

Rarely in the Tippett literature is the influence of English composers immediately after the ‘gap’ – the composers of the so-called English Musical Renaissance – regarded as being of much importance. Meirion Bowen’s assertion is typical of many commentators:

At the outset of his career as a composer, Tippett steered a fairly independent musical course. He was not in sympathy with the aspirations of Vaughan Williams towards a national school of composition rooted in English folk song. He rejected Elgar and many of the other late-romantic figures such as Mahler and Bruckner, though later he came to value and learn something from all three.18

But as David Clarke has shown in an essay on the Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1938–9), Tippett’s relationship with his national environment was not so straightforward. Clarke’s view is that while ‘Tippett seemed to have projected onto [Vaughan Williams and Holst] the different aspects of a personal ambivalence towards Englishness and English music’, the composer’s ‘stance towards these various aspects of English musical culture was in fact far from one of rejection. We might surmise that his reservations were directed less to the actual sound the music made, so to speak, than to its perceived technical limitations and ideological connotations.’19 In this regard, he took a rather softer approach than his contemporary, Benjamin Britten, whose judgements were much more severe.20

Tippett’s attitude to one of the best-known proclivities of the previous generation, the use of folksong, was also not simply one of rejection, as evidenced by the incorporation of instances of it into the Concerto for Double String Orchestra and the derivation of much of the work’s thematic material from folk-like shapes.21 He seems to have had some sort of role in Francesca Allinson’s researches, written up in an unpublished monograph entitled The Irish Contribution to English Traditional Tunes, which represent a ‘challenge to [Cecil] Sharp’s beliefs (and the whole nationalist edifice built on it) that these songs represented pure, quintessential Englishness’.22 But as Clarke points out:

It is significant, though, that the Allinson-Tippett critique entails not a dismissal of the folksong enterprise, but an attempt to reconceive it from within. This finds a parallel in Tippett’s attitude towards English musical traditions, which are not to be rejected in favour of some kind of internationalist agenda, but to be embraced without specious, nostalgic distinctions between urban and rural cultures.23

As for any influence of the first wave of the English Musical Renaissance, we have seen that Tippett himself sees the Concerto for Double String Orchestra as springing partly from ‘a special English tradition – that of Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro and Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis’.24 But the possibility of Elgar and Parry playing even a minor role in the composer’s development has hardly been entertained. And when these composers are mentioned in the literature, it is usually with a negative tone. Thus Kemp sees the influence of Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens in Tippett’s unpublished A Song of Liberty (1937) as detrimental,25 and is at best equivocal about the small number of indebtednesses to Elgar he identifies – in, for example, the slow movement of the String Quartet No. 1 (1934–5, rev. 1943) (‘The G [major] in the second section . . . creates a fresh, open sound (albeit unpleasantly suggestive of Elgar . . .’26)) and the beginning of the Scena for solo quartet (No. 15) in A Child of Our Time (‘. . . it is difficult to see precisely what Tippett intended here [No. 15] by conjuring up the spirit of the Enigma Variations, unless it was simply that Elgar’s theme crystallizes a universal mood of valedictory sorrow’27). Yet certain practices that can be identified as originating in nineteenth-century English church music and culminating in Parry and Elgar are still important elements in the stylistic mix of the music through which Tippett first achieved recognition, as Peter Evans suggests in his passing observation that those passages exhibiting ‘traditional harmony’ in the Concerto for Double String Orchestra are ‘very English in [their] ardent appoggiaturas – see the finale’s second subject’.28

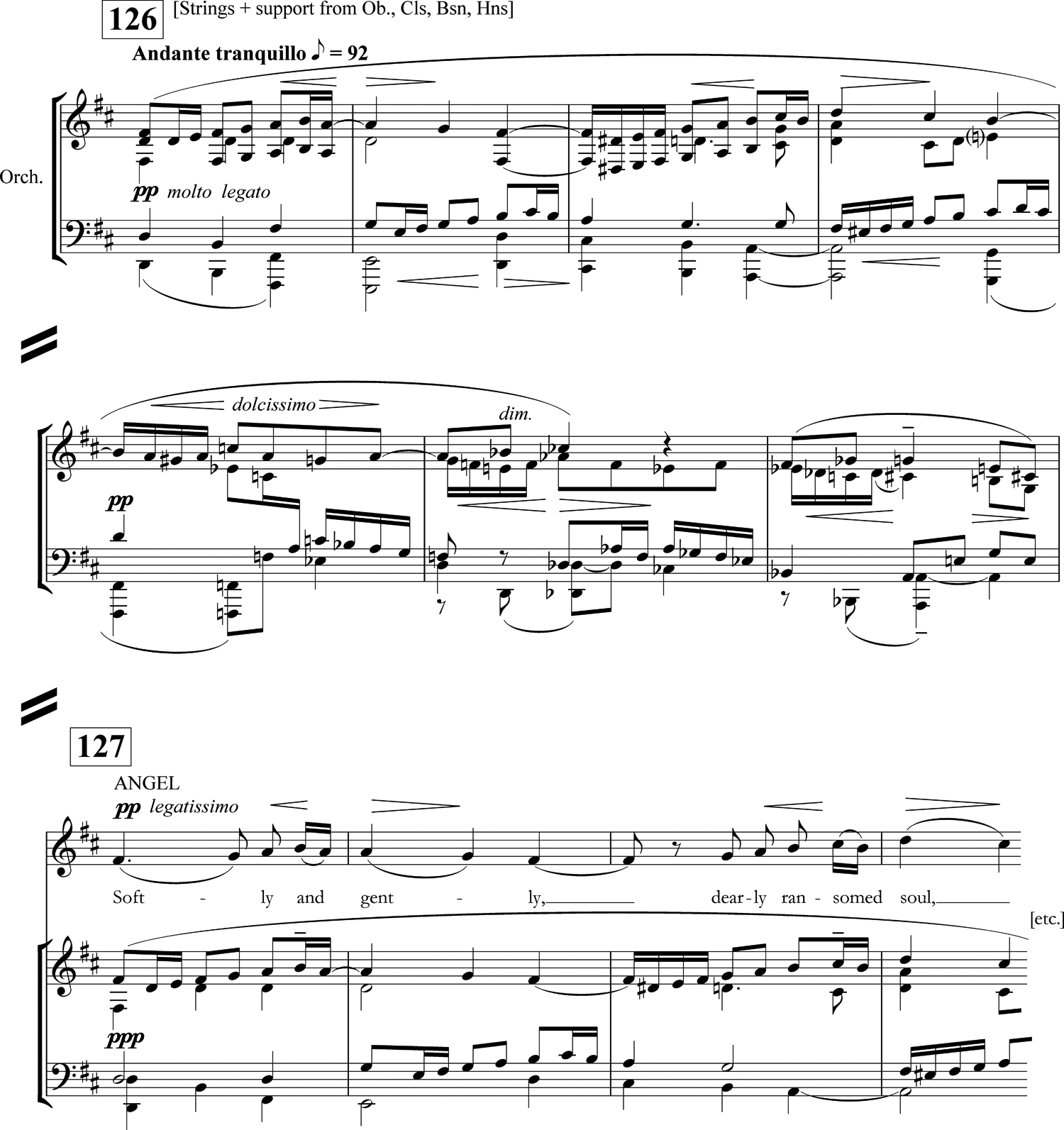

Although chromaticism is not eschewed, the opening of A Child of Our Time is characterized by the abundance of ‘“clean” diatonic dissonance’ that was one of the principal means of expression in the work of composers from S. S. Wesley to Parry and beyond:29 see, for example, the appoggiatura in bar 6 (F♯–G), the 4–3 suspension in bar 8, and in particular the 9–8 suspensions over minor-seventh chords in the sequence in Fig. 1:1–2 (see Ex. 2.1). Meanwhile, the more chromatic opening bars display the obliquity that Evans has identified as a Parry trait:30 the E minor triad that begins the work is a prime candidate for tonic (the opening paragraph ends on V of E at Fig. 1:7 and the music begins again on the same E triad, while the chorus’s initial entries are all over a V pedal in E), but this status is immediately fudged by the bass C♯; and while the subsequent movement to the putative dominant in bar 2 (via C♮) is conventional enough, the D above that resolves the suspended E is the flattened leading note. The opening is in fact a descending series of seventh chords ending on ii7. The movement on to the E-based chord in bar 6 almost confirms E as tonic, but the C above the bass, which displaces B, sustains the obliquity. To be sure, the obliquity is mild, for the tonic is not seriously in doubt; indeed, it is its very undemonstrativeness that points to the source. The beginning of the penultimate number, General Ensemble (No. 29) – the most expansive music in the work – also has its origins in Parry, again through the yearning appoggiaturas in a context that remains diatonic, at least for the tenor’s opening statement.

Ex. 2.1 A Child of Our Time, opening

The rather less restrained late romanticism of Elgar is, perhaps inevitably, less apparent. As noted above, Kemp finds a section of the central slow movement of Tippett’s String Quartet No. 1 ‘unpleasantly suggestive of Elgar’, though he does not actually say what is unpleasant about it. It seems to me that more than just this bit of the movement (which, from his comments, I take to be Fig. 23:1–3) has links with Elgar: Ex. 2.2 reproduces the beginning of the movement alongside the beginning of the slow movement of Elgar’s Symphony No. 1, which is scored for strings with telling reinforcement of the inner voices and melodic peak from the wind. I would not claim it was a conscious model – to my knowledge there is no evidence of this, and clearly much of the harmonic structuring is very different – but what Kemp describes as ‘that long soaring melodic line characteristic of so much of Tippett’s music’ (he sees this as the first example of it)31 has a clear precedent in Elgar (where it is born of Wagner’s endless melody), as does the diatonic dissonance that is again prominent.

Ex. 2.2 (a) String Quartet No. 1, second movement, opening bar to Fig. 23:3; (b) Elgar, Symphony No. 1 in A♭, third movement, opening

Closer to Elgar stylistically is the central section of Madame Sosostris’s aria in The Midsummer Marriage (1946–52; Act 3, Scene 5, from Fig. 380), the beginning of which is reproduced in Ex. 2.3 (a).32 Once again, the expressive burden falls on diatonic appoggiaturas, at the beginning of bars. Also finding a parallel in Elgar is the harmonic parenthesis from Fig. 381 (a flatwards deflection via triads of G and F before folding back through V7 of E at Fig. 381:8 – though it is linear movement, particularly in the outer parts, rather than functional progression, that is the principal agent here); compare this with Ex. 2.3 (b), the beginning of the ‘big tune’ in the final section of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius (from Fig. 126), which has a similar kind of deflection. There are also melodic figures in common between these examples (compare Fig. 380:3, last beat in the Tippett with 126:3, first beat in the Elgar), and the tempo indications are similar (Andante espressivo and Andante tranquillo; the metronome markings are exactly the same). But it is the expressive mien born of the particular use of diatonicism that is the clearest link. There is little else in Sosostris’s aria (which is very wide-ranging stylistically), or indeed in the opera as a whole, that could be said to be so clearly of English Musical Renaissance provenance: the first part of the aria (from Fig. 367 to Fig. 380) seems, for example, to point more to one of Elgar’s main sources, Wagner.33

Ex. 2.3 (a) The Midsummer Marriage, Act 3, Scene 5, Figs. 380–382:4

Ex. 2.3 (b) Elgar, Dream of Gerontius, Part II, Figs. 126–127:4 (choral parts of first two bars omitted)

The main substance of the aria is Sosostris’s presentation of her visionary credentials – or, as Kemp puts it, ‘a classic account of the creative process, laid out in four sections, each describing a particular stage’.34 The ‘Elgarian’ section introduces relative calm and luminosity after the darkened, angst-ridden descriptions of her condition in previous sections: the voice-part is cantabile, with none of the tortured intervals that have characterized much of her music thus far; the phrasing is regular (the initial statement is 4 + 4); and the harmonic rhythm is also regular and relatively conventional (Arnold Whittall sees here ‘a more orthodox extension of a tonic triad’35). Kemp’s interpretation, continuing from the point where the previous quotation leaves off, identifies Sosostris with the composer and is worth quoting at length:

From inchoate beginnings illuminated by sudden flashes of insight a struggle develops to give shape to ideas intractable yet clamouring for fulfilment, whose very fulfilment denies the humanity of their creator. The second section culminates in a magnificent but terrible acceptance of this destiny [this is the stentorian setting of the text ‘I am what has been, is and shall be, no mortal ever lifted my garment’]. Once such struggles are over something is both given and taken away. The composer is given the lucidity through which his visions of the soul can be formed and at the same time he is deprived of his identity. As himself he dies: he becomes an instrument. Tippett’s music of lucidity [from Fig. 380] is as serene as any he has written. It moves in a state of rapt spirituality, impervious to fashionable conceptions of ‘contemporary’ music, yet unmistakably original in voice, quietly asserting that the sources from which Handel and Mozart drew their inspiration are as fresh as the air we breathe.36

Ex. 2.3 (a) does indeed come across as lucid and serene. It is actually the shortest of the four sections Kemp identifies, but achieves far more ‘presence’ than this might suggest. I have already mentioned some of the features that promote this. Possibly the most important, though, is the use of a conventional V7 to stabilize the key at the beginning and again just before the varied repeat at Fig. 381:8. When the opening paragraph is repeated (transposed, and considerably varied after the initial chromaticism), the harmonic parenthesis is not, this time, closed: Kemp’s serenity is interrupted by a drastic change of tone – literally, since Sosostris is instructed to sing ‘in an altered voice’, accompanied by more astringent harmony. It is certainly the case that the music is far from ‘fashionable conceptions of “contemporary” music’, though clearly I disagree with Kemp that this particular passage is as ‘original in voice’ as he asserts. It is, though, a testament to Tippett’s skill that the section is integrated so smoothly into the heterogeneous mix of styles.

The final section of the aria, from Fig. 387, introduces another kind of music again that presents a different ‘take’ on pastoralism from that of Vaughan Williams and Holst. Sosostris’s vision is a pastoral idyll (actually marked by Tippett ‘tranquilmente à la pastorale’) that gradually becomes disturbed. The voice parts (Sosostris describing what she sees, with interjections from King Fisher) are essentially arioso, over a texture consisting of ‘a fabric of short ostinati, interrelated but of varying lengths, which combine into sound patterns at once the same and always different – a marvellously apt symbol of the infinite, timeless nature of Sosostris’s vision’.37 As Kemp observes, there are parallels here with Stravinsky’s layered ostinati and with medieval isorhythm. There is no hint of the folksong generally associated with English pastoralism, though the modal usage (which in Vaughan Williams’s and Holst’s cases is prompted by folksong) has similarities. A broad modal field is set up in which emphasizes shift: thus A♭ is the referential pitch for Sosostris at the outset, whilst F is for the orchestra, though at Figs. 388 and 389 the orchestra supports King Fisher’s interjections with an A♭ triad in the bass ‘layer’; then from Fig. 389:3, without any change to the ‘collection’ in play apart from a brief chromatic A♮, the voice shifts allegiance to B♭; and so on.

The highest stratum of the ostinato texture (the scalic descent from B♭ to F, paralleled at a fourth below) is derived from the music that presages the Ancients’ appearance in Act 1, Scene 1 at Fig. 14. Thus the original association between pastoralism and Ancient Greek culture is evoked, for, as a note at the beginning of the score of The Midsummer Marriage instructs, ‘the costumes are of the present day, except for those of the Ancients and Dancers, which are old Greek’. The note draws further attention to the opera’s pastoral setting and its use of classical symbols:

When fully lighted the stage, as seen from the audience, presents a clearing in a wood, perhaps at the top of a hill, against the sky. At the back of the stage is an architectural group of buildings, a kind of sanctuary, whose centre appears to be an ancient Greek temple.38