Genre is complicated. Musical genres at once seem intuitive, yet any closer examination of them yields contradictions and uncertainties. Disagreements inevitably arise surrounding genre labels, boundaries, levels of generality, properties, connotations, chronologies, and any other tangible evidence that genres exist in a meaningful way. Despite these traps, genre categories continue to facilitate communication as much as confuse it and, as much as musicians may insist on not being funnelled into them, there remains a pervasive fascination with them among anyone who wishes to make sense of music. Rather than do away with genre, or strive to demarcate its details with increasingly Herculean taxonomies, I have found that the most meaningful discussions of musical categories tease out the sometimes counterintuitive ways that they behave in practice. How do genres come to exist? How do they compare with one another? Why are some relationships between genres and texts more complicated than others? This chapter aims to introduce readers to debates about musical genres through a historiographical study of metalcore, a particularly slippery genre term and thus an instructive one.

My understanding of metalcore (a genre portmanteau of ‘[heavy] metal’ and ‘hardcore [punk]’) differs somewhat from other authors, whose historical narratives and timelines will be outlined further below. For one, I understand it to be an umbrella category that encompasses other genre terms such as the New Wave of American Heavy Metal (widely abbreviated NWOAHM), screamo and deathcore. As Lewis Kennedy has shown,1 many metalcore enthusiasts separate these categories entirely or assign the term metalcore to different repertories covering different time periods than I do. I treat metalcore as an umbrella term that combines those subtypes because they overlap somewhat in style traits and audience demographics, and because they have comparable reception histories. With reception history in mind, I view metalcore as an especially challenging example of what I call an abject genre of metal music.2

To introduce readers to this concept, my chapter begins with an overview of commonalities that metalcore shares with other abject genres. It then outlines diverse historical accounts by other authors to argue for a more complex view of chronological and conceptual boundaries than an individual narrative might allow. Finally, an analysis of Currents’ ‘Silence’ (2017) provides an example of metalcore as an amalgamation of stylistic qualities from multiple sources, following Kennedy.3 This chapter demonstrates the utility of abject genres as a concept for understanding metalcore from multiple angles. Using metalcore as a particularly challenging case study in genre historiography, it argues that metalcore’s complexity as a genre can teach broad lessons about genre in popular music.

Metalcore as an Abject Genre Category

Setting aside momentarily what abjection entails, abject genres may be thought of as categories of metal music that are frequently viewed with suspicion by metal fans as inauthentic imitations of ‘real’ metal, which gain popularity as fashionable trends. Moreover, in their derision of these genres, fans tend to invoke groups of people who face discrimination in the metal scene and broader society.4 Thus, abject genres involve several key concepts that reveal aesthetic beliefs within the metal scene and socio-political relations between fans. These concepts and their associated traits are summarised in Table 20.1.

Table 20.1 Abject genres and their characteristics

| Abject Genre | Glam metal | Nu metal | Metalcore5 | ||

| NWOAHM | Screamo | Deathcore | |||

| Time Range | Mid-’80s to Late-’90s | Mid-’90s to Early-’00s | Early-’00s | Mid-’00s | Late-’00s |

| Examples | Poison, Mötley Crüe | Korn, Limp Bizkit | Lamb of God, Killswitch Engage | The Devil Wears Prada, Attack Attack! | Emmure, The Acacia Strain |

| Stylistic Traits | Verse-chorus form, radio-friendly length | ||||

| Diatonic harmony, catchy tunes | Downtuned grooves, high-register dissonances, rap | Melodic death metal riffs, roared6 verse with sung chorus | Stark contrast between screamed7 verse and sung chorus | Downtuning, especially low roars, breakdowns | |

| Lyrical Themes | Hedonism | Trauma and catharsis | Conflict, loyalty, empowerment | Romantic strife | Conflict, casual misogyny8 |

| Sartorial Trends | Teased hair, tight clothes, makeup | Baggy clothes, tracksuits, jewellery, dreadlocks | Short hair, tight clothes | Asymmetrical hair, styled with clay, tight clothes | Short hair, gauged earlobes, sportswear |

| Aesthetic Goals | Rebellious appropriation of women’s glamour | Aesthetic of affliction | Down-to-earth, blue-collar, toughness | Emotional intensity, sensitivity | Cathartic aggression, intensified NWOAHM |

| Social Connotations | Male appropriations of female ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’9 (‘glam’, ‘lite’, ‘hair’) | Teenage, white suburban appropriations of Black styles | Masculine, tough, violent | Teenage scenesters, Christian, feminine | Fraternity ‘bros’, intensified NWOAHM |

A time dimension subtends an abject genre’s emergence and fall from popularity. While, in practice, this is more complicated than simply assigning a chronological start and end date to a genre, rough timeframes of decades do align with the three major instances that I argue characterise metal history since the 1980s: glam metal during the 1980s, nu metal during the 1990s, and metalcore during the 2000s. These may each be thought of as moments in time when certain styles of metal gained mass popularity with audiences that may not otherwise listen to metal. Such popularity draws a well-documented suspicion amongst metal fans towards the apparent inauthenticity of mass commerce.10 While a full exploration of this value system lies outside the scope of this chapter, it is common among fans of more traditional forms of metal to perceive abject genres, like metalcore, as a diluted misinterpretation of metal’s stylistic codes by non-fans.

Stylistically, abject genres are frequently dismissed as simplified metal with an exaggerated gimmick. All three instances involve verse-chorus forms that fit within a radio-friendly four-minute format. Nu metal eliminated guitar solos while exaggerating downtuned guitars for groove-driven riffs. That is, while bands like Pantera were routinely lowering their tunings by as much as one-and-a-half steps, nu metal bands like Korn added a seventh string to accommodate tunings as low as a perfect fifth below standard tuning. Metalcore, especially deathcore, became known for its ‘breakdown’ sections that conventionalised the slowed sections that thrash and death metal bands had explored in the late 1980s to early 1990s11 and that Suffocation had especially developed in the early 1990s for death metal.12 In contrast to the chromatically shifting power chords of Suffocation’s breakdowns, deathcore breakdowns nearly dispense with pitch changes altogether, emphasising rhythm, sometimes on a single, low open guitar string. In a particularly extreme example, ‘Word of Intulo’ (2011) by Emmure is a breakdown-like track that consists entirely of a single note for over a minute. Despite exhibiting multiple forms of rhythmic complexity – syncopations, hemiolas, cross rhythms, motivic extensions – it has been mocked over YouTube by fans who sarcastically cover it with apathetic expressions and provide ‘guitar tablatures’ consisting of strings of zeros. While such covers are done affectionately by fans of deathcore, the punchline about apparent simplicity draws from the same critiques made by its detractors.

A lyrical dimension can be observed that unifies each of the abject genres in opposition to other forms of metal. As I have shown in more detail elsewhere, this difference can be thought of as a split between heavy metal’s traditional emphasis on supernatural themes and abject genres’ emphasis on quotidian lyrics.13 While Iron Maiden’s ‘The Number of the Beast’ (1982) epitomises heavy metal’s fantastical lyrical imagery, glam metal band Poison’s ‘Nothin’ but a Good Time’ (1988) focuses its fantasy escape around themes of everyday life. In contrast to the black metal lyrics of Emperor’s ‘I am the Black Wizards’ (1993), Korn’s ‘Faget’ (1994) presents its audiences with relatable nu metal lyrics about high-school bullying. The death metal lyrics of Hate Eternal’s ‘Two Demons’ (2005), rife with archaisms (‘reveal thyself’) and references to ‘beings’ and ‘souls’, cultivates a decidedly supernatural feel compared to the NWOAHM band Lamb of God’s ‘Laid to Rest’ (2004), which depicts the potentially supernatural theme of a murder victim’s revenge with everyday slang. As Marcus Erbe notes in his analysis of male frustrations in deathcore lyrics, metalcore vocalists construct authenticity around their lyrics being expressions of personal experience14 in contrast to what Michelle Phillipov sees as a lack of personal identification in 1990s death metal lyrics.15 I have argued elsewhere that death metal vocalists do undergo a more figurative kind of identification in their physiological imitations of large beasts.16 One might infer then that this figurative identification with beasts would also apply to deathcore vocalists whose growls are similar to those used in death metal. However, lyrical differences between death metal and deathcore parallel how the two genres construct authenticity differently. And it is that difference between quotidian, personal identification and supernatural, figurative identification that generally distinguishes abject genres from more traditional forms of metal.

A social dimension characterises each of the abject genres, reflective of socio-political tensions within the metal scene. Glam metal, as Robert Walser’s pioneering study of gender-play within the style demonstrates, dealt with male anxieties towards women by appropriating the spectacle of androgyny to express control over women and rebel against dominant men.17 Nu metal incorporated musical and visual codes of Black cultures through its use of rap and DJ scratching from hip hop as well as its baggy clothes and visual celebration of commodities (i.e., jewellery, cars); dreadlocks became increasingly fashionable during the 1990s as worn by the members of Korn, Soulfly and Coal Chamber. Screamo, whose loose status as a ‘-core’ genre can be seen in derisive nicknames like ‘Christcore’,18 bears a connection to the demographic category of teenage youth, as did nu metal with the nickname ‘mallcore’ (which is sardonically gendered as well). In music journalism of the 2000s and retrospective writings more currently, one finds screamo (and its root term ‘emo’) associated with terms like ‘scene kids’ that accompany fashion stereotypes associated with dark, asymmetrical hairstyles, black eyeliner and Myspace selfies.19 Thus, in their criticisms of why they find abject genres uncool, metal fans frequently invoke subtle antagonisms towards three categories of identity: women, racial Blackness and teenage youth. Tensions around these demographics reflect continuing forms of discrimination broadly found within the metal scene and are an important reason why I unify those genres with the descriptor ‘abject’.

Abjection, a concept analysed in Julia Kristeva’s The Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, refers to something unknown and threatening that provokes disgust and terror.20 While its literal manifestation might lie in various forms of human waste, the urge it provokes to destroy it can be transferred psychically to social entities such as threatening demographics of people, upsetting kinds of discourses, or troubling categories of music. Intense discomfort, essentially, is the experience of abjection, coupled with the need to obliterate it and rid oneself of the threat. Such an explanation may bring to mind some of the darkest examples, such as mass genocides and hate crimes. Indeed, as metal studies have shown during the past two decades,21 serious forms of discrimination continue to affect the global metal scene, and the ways that abject genres are denigrated within fan discourses is one useful window into those often subtle prejudices.

Historiography of Metalcore

As one might expect with any genre of popular music, authors have presented conflicting accounts of what the term metalcore means. In some ways, acknowledging this diversity of accounts is almost a historiographical truism, not merely because different authors inevitably harbour different subjective viewpoints. More subtly, it also relates to the unstable ways in which genres emerge. As one finds with hard rock and heavy metal during the 1970s – terms that were used inconsistently and interchangeably at the time – authors writing about metalcore during its emergence write about it differently than those writing a decade or more later. But even speaking of an emergence of metalcore, as though such a time reference exists within a stable time frame, oversimplifies the history of the term. Any time frame, such as the one I provisionally gave above, will conflict with some accounts that give other dates. A bounded numerical range like 2004–2007 also simplifies chronological boundaries, not merely because one might debate whether a point of origin ought to be placed at 2003 or 2004, but also because genres, as a rule, do not emerge from the head of Medusa without precedent. Rather, they gradually coalesce in a process of discursive iteration and citation. That is, with every new iteration – such as a recording, concert review, rock interview and conversation among fans – the existence of a genre category becomes cited and re-cited, and thus more recognisable. This process occurs inconsistently over long or short spans of time, more in certain spaces (geographical, subcultural, discursive) than others, and variously among different agents (e.g., fans, critics and musicians) who engage with music in sometimes separate ways with differing levels of intensity. As a result of this rather chaotic soup of communication, any historical origin must be stipulated with some arbitrariness and any time span necessarily represents an approximation.22

While this is true of genre in general, metalcore is especially messy. To begin with, the term itself suggests hybridity and points to its roots in speed metal and hardcore punk, known in combination during the mid-1980s as ‘crossover’.23 Ian Christe, a music journalist writing in 2003, frames metalcore as being interchangeable with crossover: ‘in 1987 most new names played a cross-pollinated S.O.D.-style hybrid called metalcore, or simply crossover’.24 Each of the examples he lists comes from the 1980s, an early chronological focus that fits the relatively early date of his publication. More so than authors writing in the late 2000s and in contrast to those of the 2010s, Christe’s perspective took place when metalcore was beginning to be recognised in the form that later authors know it. In other words, the emergence of the NWOAHM and its growing popularity as an abject subgenre (i.e., broadly popular, yet suspect in the metal scene for that popularity) would likely have seemed to be a curious but vague development at the time of writing. However, one does get a fascinating glimpse at Christe’s view of these bands in his afterword, where he intriguingly positions a wide range of 2000s metalcore as an authentic antidote to inauthentic pop punk. For Christe, the ‘new breed metalcore scene’ – represented by the more melodic strand of Himsa, Freya, (early) Poison the Well; and the more aggressive strand of Hatebreed and Converge – functions as a response to pop punk in the same way that 1980s crossover bands rebelled against glam metal (‘hair metal’ for Christe) in the mid-1980s.25 The inauthentic status of an abject genre, it is clear, is relative to the observer.

Jon Wiederhorn and Katherine Turman’s Definitive Oral History of Metal gives a precise time range for metalcore (1992–2006) and mentions a start date for deathcore (2007).26 Such an account indicates that they view the genre terms as separate categories, ones that have a historiographical relationship of chronological succession. In Wiederhorn and Turman’s oral history, metalcore ends as deathcore takes its place. Like Christe above, Wiederhorn and Turman trace the history of these genres back to crossover in the 1980s, providing an end date for that music in 1992, the same year that they state metalcore begins.

Another notable aspect of their history is their framing of subgenre tributaries. Their chapter on metalcore begins by alerting readers to how metalcore cannot simply be a combination of metal and hardcore punk but rather should be viewed as a collection of influences, among them ‘American post-punk and noise-rock’, as well as ‘avant-garde prog rock, straight-edge, and/or screamo’.27 For Wiederhorn and Turman, then, these subgenres represent related influences but not metalcore proper. Rather than debate whether these subgenres belong inside or outside metalcore, a better point might be to acknowledge the porousness of genre boundaries in general and observe how Wiederhorn and Turman’s account reveals the richness of different subgenres that make metalcore a complex concept. Certain subgenres may seem more centrally relevant to metalcore, depending on one’s vantage point: straight-edge might seem most pertinent if one views metalcore in terms of lifestyle and attitude, American post-punk might seem more related than avant-garde prog rock if one thinks chronologically and geographically with the NWOAHM in mind (more on that below), and from a reception standpoint of abject genres, screamo appears most targeted for ridicule, which is why my earlier work on abject genres treats it as a subgenre of metalcore.28

Lewis Kennedy’s research on metalcore represents the most theoretically sophisticated and complete account of the genre to date. An expert on its bands and recordings as a fan and musician, his dissertation29 and publications related to it30 synthesise research on hardcore punk and metal and offer compelling historical narratives that take current genre theory into account. One of his arguments is that metal and hardcore punk exist in a symbiotic relationship. Despite uneasy tensions existing for decades between fans and musicians devoted to one tradition or the other, Kennedy observes that metal and punk are ‘very difficult to separate from one another’ due to their reliance ‘upon one another for continued influence and inspiration’,31 and that factions from within both traditions continuously fail to. Some genre purists within hardcore attempt to resist what they see as the stylistic dilution of hardcore within hybrid styles like crossover and metalcore. Thus, he cites the members of hardcore band Madball affirming their allegiance to hardcore in their lyrics and titles.32 This gatekeeping by hardcore fans and musicians mirrors similar discourses among metal fans.33 From both sides, metalcore is viewed with suspicion in a futile attempt to police the mixing of styles and ideologies. It is also against that suspicion that crossover and metalcore bands – metalcore positioned as potentially the ‘spiritual successor of crossover’ – construct a narrative of themselves as struggling in opposition to genre purists.34

The other important argument Kennedy makes is that metalcore became recognisable in its present form due to a stylistic process he calls codification, involving the so-called New Wave of American Heavy Metal. A loose nod to the more widely known NWOBHM (New Wave of British Heavy Metal), the NWOAHM is a subgenre of metal that emerged in popularity around 2004. It combined stylistic traits taken from melodic death metal, thrash metal and groove-oriented bands like Pantera with the tough, no-nonsense sensibilities (e.g., titles and band names, ideals of authenticity) and quotidian lyrics of hardcore punk. In a way suited to its awkward acronym, the NWOAHM was only loosely recognised as an emerging style, debated by fans and critics as to its significance. The codification taking place is the retrospectively recognisable process of moving from an initially loose observation that comparable bands like Lamb of God, Shadows Fall and Killswitch Engage were gaining popularity towards a ‘reification of certain elements of style and the simultaneous diminution of others’.35 Kennedy cites how writers around 2005 were including the odd time signatures and non-standard song forms of The Dillinger Escape Plan as representative of metalcore, while later authors such as Wiederhorn and Turman exclude those as precursor traits.36 Gradually, the most recognisable musical features of metalcore became breakdowns, riffs influenced by melodic death metal, high-fidelity production and clean singing alternating with vocal roars (a distorted style communicative of quotidian anger more than the inhuman stylisations of death metal grunts). The codification of these traits, I would argue, stylistically unites subgenres like deathcore, screamo and the NWOAHM, which is another reason why I treat metalcore as an umbrella term.

The Sound of Metalcore

‘Silence’ (2017), a song by the metalcore band Currents, offers an example of metalcore understood in its post-codified sense, as an exemplar of narrowed stylistic traits,37 as well as its abject sense, as a mixture of genre markers associated with different abject subgenres. Some of these markers are extramusical and exemplify the lyrical divide between the supernatural themes of extreme metal and the quotidian themes of metalcore. According to an interview with vocalist Brian Wille, the lyrics of ‘Silence’ focus on the relatable, everyday theme of different pressures he and his fans might encounter in life:

It’s basically about feeling that pressure to impress other people and having that pressure of expectation from all different parts of your life. You know you got your parents, they have an idea of where they want you to be or what they want you to do. You have your job, you know, and you have people that expect things of you. And then even with like the band and stuff like that, there’s pressure to like, you know, do certain things and play a certain way and all of this. So it’s kind of a song about me dealing with all of those pressures and trying to just bounce them off.38

In ways seldom encountered in death and black metal lyrics, ‘Silence’ is thus partly autobiographical and, if the nod to parents is significant, relatable to a youth audience. This aspect bears emphasis when speaking of metalcore as an abject genre. Much scholarship on metal treats the music as an emblem of youth cultures.39 Rarely is youth discussed in metal scholarship as a target for discrimination.

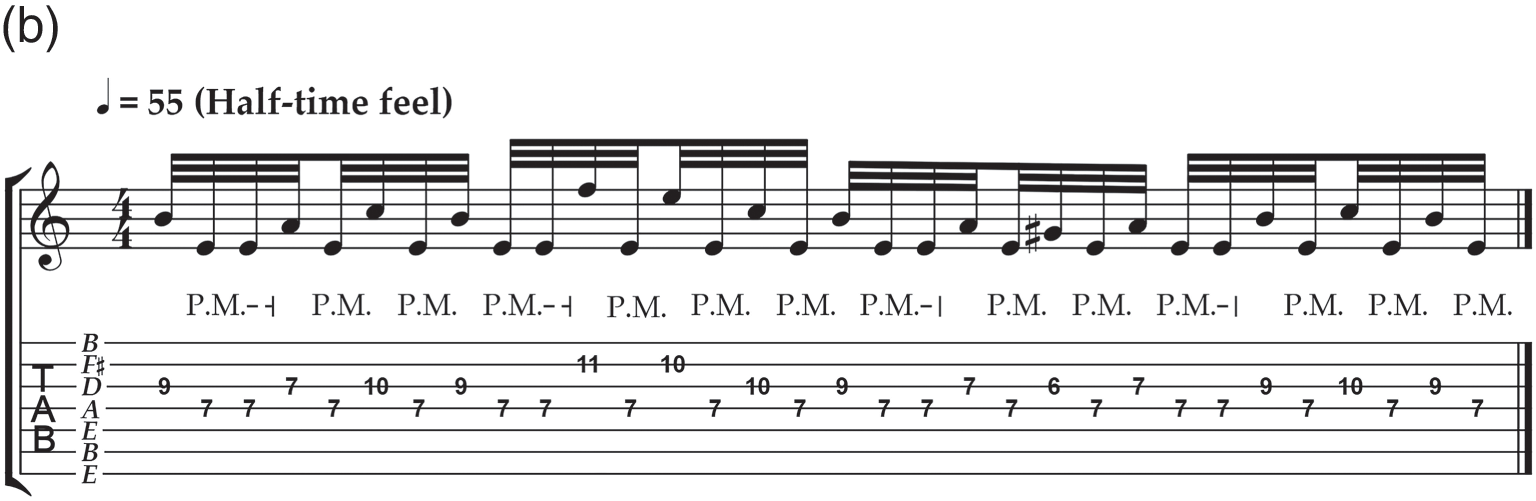

Musically, the song contains all the elements of metalcore cited by Kennedy: ‘the combination of clean and distorted vocals, high-fidelity, polished production, and a clear influence from melodic death metal’.40 That clear influence is partially found in the verse-chorus song form shown in Table 20.2. Familiar verse-chorus song structures are, as I have shown,41 one of the features of melodic death metal that contribute to its reputation for being ‘melodic’, or musically accessible. Another influence from melodic death metal can be heard in some of the song’s diatonic guitar riffs that focus on higher-register melodic figurations (Figures 20.1a, 20.1b).

Table 20.2 Song form for Currents’ ‘Silence’ (2017)

| Intro | Verse 1 | Chorus A | Verse 2 | Chorus B | Breakdown 1 | Chorus A | Verse 2 | Chorus B | Bridge | Breakdown 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | 0:17 | 0:37 | 0:55 | 1:19 | 1:46 | 2:12 | 2:30 | 2:47 | 3:13 | 3:30 |

Figure 20.1a Melodic figuration during the first verse (0:20)

Figure 20.1b Melodic figuration during Breakdown 1 (2:03)

Looking at other features in Kennedy’s quote above, the song’s use of clean and distorted vocals demarcates the change from screamed verse to sung chorus, changing the mood from frustration to vulnerable, emotive reflection. Such introspection, and the characteristic shifts in song form that accommodate it, are strong markers of related abject subgenres like screamo and nu metal.42 When combined with a second-person lyrical address, screamed and sung settings dramatise romantic conflict, emotional exasperation and intensity with a highly personal feel. Indeed, all of those things can be heard at the pivotal, stop-time moment that ends the song’s bridge at 3:29 and acts as a pickup to the final breakdown section. At this moment, the accompaniment stops to emphasise the roared words, ‘f**k you, I’m moving on!’. This is the kind of direct, quotidian catharsis that I argue is generally antithetical to extreme metal and more traditional forms of metal centred around supernatural or mythological themes. Even the obsession with murder found in death metal tends towards exaggerated, ‘brutal’ violence rather than personal, relatable disputes.

Lastly, the song does indeed boast a hi-fi, polished production with a careful mix of sounds, balanced throughout different registers and skilfully varied for rhetorical effect as the song moves through different sections.

Perhaps the most dramatic instance of this rhetorical effect comes in the song’s two breakdown sections. In metalcore, the breakdown represents a song’s sectional climax,43 the peak of a song understood as a sectional plateau rather than a brief instance. Breakdowns represent moments of climactic contrast during a song that emphasise slower tempos and unison rhythmic playing between the guitars and kick drums while vocals perform independently of the rhythmic groove. In his article devoted to exploring the breakdown and its varied meanings in twenty-first-century metal, Steven Gamble explains that breakdowns serve a communal and cathartic function during live shows, when vocalists sometimes create anticipation for them during stage banter and prompt fans to mosh extra hard when they happen.44 To demonstrate their primacy for fans, Gamble points to the significance of online curatorial collections of breakdowns extracted from their song contexts in ‘best-of’ compilations. As Gamble notes, ‘no such curatorial practice exists around the best metalcore verses’ or other metalcore song sections, demonstrating that ‘it is clearly the breakdown which constitutes the climax and key section of [metalcore] tracks’.45 He observes that fans in YouTube comment sections provide time stamps for breakdowns, singling out those sections for discussion.46 In fact, according to YouTube’s ‘most replayed’ feature, the most replayed moment of ‘Silence’ is the beginning of Breakdown 2 at 3:30, about which I will say more further below.47

While the breakdown normally functions similarly to the bridge section of a verse-chorus song, that is, as a contrasting section two-thirds of the way through the song, it is arguably even more prominent in ‘Silence’. Here, two breakdowns occur in important places, midway through the song and at the end, each punctuating the end of a verse-chorus grouping. One significance of this double appearance is that the song breaks from its usual atmosphere twice to rhetorically intensify the song. In other words, what happens during these sections is marked for semiotic importance because fans recognise that breakdowns are meant to be extra heavy. The other aspect of significance is that the song’s two separate breakdowns draw their semiotic codes from different subgenres – nu metal, melodic death metal, NWOAHM and djent – providing an opportunity to analyse how codes from different subgenres can operate within the same song and contribute to metalcore in similar ways.

The first breakdown is quite representative of the kinds of deathcore breakdowns that gained popularity in the mid-to-late 2000s. Like the Emmure track ‘Word of Intulo’ mentioned above, the beginning of the breakdown distils the guitar to a single low pitch (or power chord) that stutters through a syncopated rhythm (Figure 20.2).48 This is the characteristic, low open-string approach to breakdowns in deathcore in contrast to the shifting power chords of earlier precedents in the 1990s.49 That reduction in pitch activity focuses attention on rhythm and creates a jarring, strobe-like effect through the guitar’s syncopations. Even though there is plenty of musical activity throughout, the breakdown is arranged in such a way as to make time feel like it has slowed. If one measures tempo through snare pacing on beats two and four, the breakdown occurs in half-time relative to the previous chorus. That contrast between sections is further dramatised through the impact of the breakdown’s initial downbeat. Heard best with headphones, it involves a diving low pitch, likely made by a drum trigger, which makes the power of the downbeat linger until the syncopations take over on beat two. That combination of half-time and an explosive downbeat that lingers through a pitch descent creates the extra slow, weighty feel of the breakdown conducive to moshing.

Figure 20.2 Single-note, syncopated rhythm Breakdown 1 (1:46)

Some genre markers further colour the atmosphere of this breakdown as well. The middle-register melodic pull-offs heard near the end of the breakdown (2:03) suggest an influence from melodic death metal, typical of the NWOAHM. The minor-second dissonances that serve as a pickup to the initial downbeat and that recur as a momentary slide (1:50; see also the later instance marked ‘loco’ in Figure 20.3) and as a background effect (1:55) recall the aesthetic of affliction characteristic of nu metal bands like Slipknot and Korn before them. The voice as well carries signifiers of genre through the roared vocals heard in the verse. Its appearance in the breakdown continues the earlier alternation between intensity (verse roars) and introspection (chorus singing) typical of metalcore. In this particular breakdown, one can even hear a simultaneous contrast between the more lyrically decipherable roars of metalcore and the less decipherable growls of death metal partway through (1:55), useful for comparing the two vocal styles.

The second breakdown, which ends the song, involves a similar punctuation of the downbeat and stuttering low guitar, much like the first breakdown. However, here one can hear markers of djent, arguably a newer abject subgenre that emerged following deathcore at the beginning of the 2010s.50 Djent, a genre term that onomatopoetically imitates the sound of its guitars, focuses on rhythmic and metric complexity, influenced by the style traits of the progressive metal band Meshuggah, its progenitor. Like Meshuggah, djent bands eschew power chords in favour of single-note riffs around one octave below standard tuning. This extra-low pitch makes an appearance in the second breakdown of ‘Silence’ and is perhaps most noticeable in the slow, Meshuggah-like bend at 3:39 (see Figure 20.3). Djent sounds in the second breakdown not only contribute to the section’s sense of heaviness but also continue earlier instances where the genre can be heard: the clean-tone introduction is reminiscent of djent/progressive-metal band Animals as Leaders’ ‘CAFO’ (2009); the first verse (0:17) also involves the extra low E, which provides it with a djent feel; the muted rhythm guitar during Chorus A (0:37) also resembles Meshuggah.

Finally, the rap-like delivery of the roars in Verse 2 (0:59) and Chorus B (1:22) suggests the influence of nu metal; and the gang vocals – collective shouting (or singing in this case) to accent particular lyrics – that occur in Chorus B (1:18) recall conventions from hardcore punk.

All of these strong markers of different genres mix together to reveal how metalcore in 2017 had assimilated numerous earlier styles. Most notably, with the exception of the gang vocals from hardcore punk, each of these styles could be said to come from abject subgenres. Thus, stylistically, as well as lyrically – and sartorially as a glance at the band’s short haircuts and skinny jeans will show – Currents break from the generic conventions of metal in ways that better suit metalcore, understood broadly as a combination of multiple abject subgenres.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided a condensed overview of metalcore in terms of genre theory, historiography and musical style. I began with some theoretical observations about genre in general, noting that metalcore represents an especially tangled instance of genre that can be instructive for learning about popular music genres more broadly. The notion of an ‘abject genre’ served as a conceptual lens throughout the chapter, necessitating an extended review of how metalcore fits within a decades-long, ongoing history of abject genres in metal. One of the reasons why that frame is pedagogically helpful is that it foregrounds the importance of nuance and uncertainty in historiography. Questions of what counts as an abject genre and what time frames apply to an example naturally arise when investigating trends in mass popularity, and their answers tend to be more elusive the closer one’s example gets to the present. More than other abject genres, metalcore has proven to be slippery for assigning dates and delimiting what subgenres count within it as an umbrella category. While I have stipulated some provisional answers – namely NWOAHM, screamo and deathcore for subcategories and a terminus post quem of 2003 or 2004 – a closer examination of other authors’ historiographies reveals those answers to be one among several narratives. Indeed, those authors have unique explanations for how the above subgenres relate to metalcore historically: Kennedy views the NWOAHM as codifying metalcore during the mid-2000s, and Wiederhorn and Turman view deathcore separately from metalcore, suggesting an upper limit around 2006, just prior to deathcore’s early popularity. The advent of djent at the end of the 2000s may be another upper limit, depending on whether one sees a shift taking place at that time, from metalcore to djent, comparable to the shift that took place during the early 2000s from nu metal to metalcore. Arguably, in both instances, metal fans redirected their suspicions from one ‘inauthentic’ trend to similarly dismissing the newer one that replaced it in mass popularity.

My analysis of ‘Silence’ reveals a musical side to that possibility by exploring a track that involves both the stylistic features of metalcore and some djent traits within the same song. Within the span of a single track, one can hear multiple markers of abject genres: a verse-chorus format within a radio-friendly timespan, breakdown sections, lyrics involving introspection and vulnerability, rap-like vocal delivery reminiscent of nu metal, melodic guitar riffs that were central to the NWOAHM’s codification of metalcore, and markers of djent in multiple sections. Taken together, these features demonstrate metalcore’s assimilation of earlier metal styles, especially traits associated with other abject genres.

Throughout, I argued for reasons why I conceive of metalcore as an umbrella term and an example of what I call ‘abject genres’. Those reasons involve key intersections with other abject metal subgenres, detailed throughout the chapter, and key differences between metalcore and more traditional forms of metal. Importantly, those observations are not limited to musical sound but extend to traits such as lyrical subject matter, sartorial fashions and sometimes implied audience demographics. While the scope of this chapter does not permit a thorough investigation of fan statements, reception studies reveal that their discussions of genre and value judgment are frequently framed with categories of identity.51 It is this broad range of observations – musical, lyrical, sartorial, verbal/discursive – that reveals the social importance of abject genres as a concept. My application of the term is not meant to be a personal value judgment about metalcore but rather a recognition of metalcore’s turbulent reception within the broader metal community.