Listed among the handful of prominent Krautrock groups lies Faust, who were a self-described ‘amalgam of eight people, and the only thing they had in common was the fact that they belonged to the male species’.Footnote 1 They are the first band after Can and Neu! on leading American online music publication Pitchfork‘s Best Krautrock list (an aggregate ranking compiled from reviews as far back as 2001).Footnote 2 Academic research on the band is non-existent prior to Arne Koch’s 2009 article, and critical efforts before that, such as Julian Cope’s Krautrocksampler, have disseminated either false or highly exaggerated information often perpetuated by the band members’ elusive and contradictory responses to direct questions. It is therefore a challenge to academically assess the band based on any solid statement, researchers like Koch, Wilson, and Adelt having been left to speculate both Faust’s history and intentions based on scattered anecdotes.

Furthermore, Faust’s abrasive sound is unlike other Krautrock bands. Rather than the driving motorik beats and kosmische synthesiser soundscapes, Faust created experimental cut-ups incorporating any noise imaginable, reaching solipsistically for ‘the sound of yourself listening’.Footnote 3 The reactions of listeners to Faust’s dissonance range from surreal laughter to horrified confusion; Faust’s music is not social music, and tracing the lineage of their influence creates a complicated path with no easily distinguished progenitors and inheritors.

While their acclaim was not immediately felt, Faust would be appreciated for decades to come. The band’s legacy leaves a fractured gaze into a world of invention that reacted against the contemporary prevailing norms of Anglo-American rock music. Faust aimed to find a specifically German approach to inject the established rock mythos with avant-garde experimentation, mixing noise, and radical aesthetics within a Romantic-Dada spirit.

Chance Encounters: Formation, 1969

In 1969, Polydor approached journalist Uwe Nettelbeck to create a German rival to The Beatles. In Hamburg, Nettelbeck found Nukleus (Jean-Hervé Péron on bass, Rudolf Sosna on guitar, and Gunther Wüsthoff on saxophone) and suggested adding drums, contacting Campylognatus Citelli (Werner ‘Zappi’ Diermaier and Arnulf Meifert on drums and Hans-Joachim Irmler on organ).

For a name, Nettelbeck suggested Richard Wagner’s Norse-influenced opera ‘Götterdämmerung’ (Twilight of the Gods). Band members rejected this by stabbing a note with the name onto Nettelbeck’s front door.Footnote 4 Instead, they settled on Faust, which translates as ‘fist’ and references the Faust folk tale, their decision to sign a deal with a major label suggesting they ‘sold their souls’, much as Faust does to Mephistopheles as portrayed most famously in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1808 play. These foundations, and Nettelbeck’s love of Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick,Footnote 5 suggest a Romanticist mindset nestled within their musical experimentation.

In 1970, Faust recorded two tracks for a demo in an abandoned air-raid shelter: ‘Baby’, a psychedelic jam sung in falsetto, and ‘Lieber Herr Deutschland’ (Dear Mr Germany), a collage of protest shouts and improvised noise, followed by steady rock accompanying a mumbled recitation of a washing machine manual. The political reaction against consumerism targets the machine’s destruction of conscious thought, comparing political organisation with mechanic automation and illustrating the necessity of individual autonomy.Footnote 6

Polydor signed the group after hearing the demo, providing full studio equipment in a converted schoolhouse/commune in small-town Wümme in north Germany. Kurt Graupner (described as ‘a straight mind’Footnote 7 when compared to the rest of the odd cohort) sat beside Uwe Nettelbeck and tinkered behind the production desk, finding new ways to process and organise the chaotic sounds. Equipment was wired through the house so members could record new sounds from the comfort of their beds. Television and radio were prohibited, blocking outside influences. Artists and girlfriends occasionally visited the site, which was a hotspot for ‘hippie’ living and far-left politics. Nevertheless, Faust’s ethos could not easily be defined as ‘hippie’ or ‘radical’. The music often attacked ‘flower-power’ sensibilities with claustrophobic noise, and Irmler claimed later that while ‘you can’t make music while being political’, he felt that they ‘were not really a political group’.Footnote 8 Even though the protest recordings and the clenched fist of their debut’s cover art lampshade a flirtation with the political, ideological unity is erased in the large band’s multiplicity of potential intentions and perspectives.

Their German heritage contributed to what commune frequenter (and later collaborator) Peter Blegvad described as ‘a need for a radical exorcism of their [the German peoples’] recent past’.Footnote 9 Faust were of a generation shielded from the horrors of Nazism yet living in the shadow it had left over perceptions of German culture. Faust acknowledged the paradoxes of these cultural tensions but sought past it to discover new states of being. Critic Pierro Scaruffi stated, ‘Faust had little or no interest in psychedelia, and even less interest in the universe. They were (morbidly) fascinated by the human psyche in the 20th century.’Footnote 10 Support for this claim runs deep, such as in a manifesto issued in 1972, wherein they claimed they were influenced by ‘the Heisenberg principle, anti-matter, relativity, Hitler, relativity, cybernetics, D.N.A., game theory, etc.’.Footnote 11 While several ‘influences’ directly reference German identity, some are purely physical or biological, each reflecting an aspect of that over-arching nature from which the individual could never free itself, against which the individual is found helpless in the world.

The band’s music comes out of the limitations of each member’s socio-psychological states, but also resists these limits through collaboration, all in search of new frontiers of expression and being. Much like Dada and Fluxus artists, Faust acted on a need to eschew all authority and form, to react to the constraints of modernity and industrialised society with not only a recognition of but a commitment to the absurd. Indeed, this quest was always Romantic in nature. Tzara claimed: ‘Dada was born of a moral need … that man, at the centre of all creations of the spirit, must affirm his primacy over notions emptied of all substance.’Footnote 12

This relates to Northrop Frye’s claim that the Romantic hero gains his individualist power from nature as separated from civilisation, a power that civilisation supposedly lacks.Footnote 13 Similarly, Faust wished to rediscover man’s supposed primacy in reaction to modernist nihilism. Escaping to their commune and combining psychoactive drugs with ‘hippie’ spirituality, Faust were in search of thought at the edge of the eternally fleeting present, lacking essence and meaning, but embodying momentum and physicality. To explain, Faust wrote an English manifesto (with the help of fellow musician Peter Blegvad) on their 1973 tour, wherein they declared:

this is the time we are in love with. The Absurd was ushered in & seated in the place of honour … [it] has medicinal properties, the Absurd, it is now discovered, decides! but that was now, learning to eat time with one’s ears. savouring each moment – distinct as a dot of braille.Footnote 14

The goal was not only to discover the enlightened state of present awareness and absurdity but to create music that destroys the constraints limiting the individual from achieving that state. A group consciousness takes hold both in the communal living style and introduction of mechanical ‘black boxes’ to the musical processes, whereby any musician could alter another’s sound by the quick flip of a switch, with effects such as ring modulation and extreme echoes rendering instruments’ timbre and performance unrecognisable.Footnote 15 Musicianship was purposefully removed from the performance, distorted and filtered through Graupner and Nettelbeck’s chaotic mixes.

That said, the role of these overseers adds composition to the chaos. The futurist aesthetics of fascist spirit in the sounds of machinery and protest (‘Why Don’t You Eat Carrots?’) clash with moments of pastoral folk (‘Chère Chambre’) and psychedelic improvisations (‘Krautrock’), but nevertheless, the aesthetics function on their own logic outside the crutch of exploiting associative signs. Rather than create a spectacle of disorientation, Faust make music that functions, as if ideological, as a cohesive whole, composing noise to avoid pop music’s repetition of timbres and forms. What monomania this ‘wholeness’ points to is without a singular rhetoric, instead opening itself up to multiplicities of differing meanings. Ian MacDonald, in his review in the New Musical Express, once described this paradoxical form by claiming:

Faust aren’t, like Zappa, trying to piece together a jigsaw with the parts taken from several different jigsaw sets; they’re taking a single picture (which may be extremely unorthodox in its virgin state), chopping it into jigsaw-pieces, and fitting it together again in a different way.Footnote 16

This suggests an acousmatic process, blurring this original ‘picture’ to make sounds displaced with new states of reference. As Péron suggests, approaching the albums in chronological order both mirrors the development of 1970s upheaval and Faust’s own philosophy and artistry.Footnote 17

Experiments in Sound and Spirit: Faust (1971)

Polydor announced the band’s debut as follows: ‘Faust have taken the search for new sounds farther than any other group.’Footnote 18 As if in defence, Cope argued, ‘Faust were brought up with middle-European dances and a staple of folk and tradition which was not 4/4 … German bands could get far more complex than U.S. and British bands would ever dare.’Footnote 19 While his description displays a tendency to exoticism, it aligns with the band’s own postures, tapping into clichéd half-thoughts of Germanic pagan roots uncomfortably associated with Nazi imagery, reclaiming rather than abandoning their presence.

The opening song ‘Why Don’t You Eat Carrots?’ fades in with a thick, distorted wall of radio hum, washing out hooks from The Beatles’ ‘All You Need is Love’ and The Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction’, and reworking them into a fluid whole while ironically quoting them to contrast the mess of dissonant marches and foghorns to follow. Deranged, drunken voices join in, clapping and chanting or screaming into the torment of industrial hell. Analysing the lyrics here seems futile, the words forming an exquisite cadaver. Being mostly written in English, the album’s lyrics were meant to be heard by English-speaking audiences abroad, creating a denied expectation for meaning and creating confusion. It is not the conscious semantics, but language’s unconscious energy – the rhyme and meter – that end up possessing the listener.

The next two tracks carry the album’s visceral, psychedelic flow through messy jams and abstract soundscapes, deconstructing the boundaries of music and noise in composition. Field recordings give attention to space, pairing ‘private’ sounds of creaking doors and clinking dishes with ‘public’ sounds of machinery, producing an indistinguishable mass that, as in Adelt’s applied analysis of Lipsitz to Krautrock, creates a hybrid space that both offers revolution and creates culture anew.Footnote 20 Lyrics dismantle the supposed difference between the primitive and modern: for example, on ‘Meadow Meal’, Faust state that to avoid becoming ‘a meadow meal’ eaten by wild beasts, man industrialises, wherein he must ‘stand in line, keep in line’, only to ‘lose [his] hand’ in a red (i.e. blood-stained) accident. Faust suggests that industrialisation, rather than solving man’s problems, simply rearranges them into new, obfuscated forms. Even these more serious moments are interrupted by humour, pitch-shifted voices, and jarring dynamic shifts, resisting even their own systems in a carnival of Bakhtinian-Dionysian gestures.

Most explanatory perhaps of the band’s whole project are the closing lyrics of ‘Miss Fortune’, a deadpan manifesto bouncing across the stereo image, quipping ‘Are we to be or not to be?’ and ‘Voltaire … told you to be free / and you obeyed’. In consequence of these questions and demands, Faust conclude: ‘We have to decide which is important: … / A system and a theory, / or our wish to be free?’

Faust confronts the listener here, rhetorically pointing to a humanist liberation from disillusioning societal expectations, supporting inaction in the final line’s attack on praxis, reaffirming the purpose of Faust’s music: to liberate the listener from those contexts and expectations to which he is enslaved, and invent new values. To experience ‘the sound of yourself listening’ is to understand how to experience reality. This single proclamation does not explain the music in an all-too singular narrative, but it does invite the listener to participate in Faust’s ‘here and now’.

The album went up for sale in October 1971 and sold less than 1,000 copies in Germany. To promote their music, the group would play at Hamburg’s Musikhalle, fifty speakers surrounding the audience as if geared to play Stockhausen. Critics and locals prepared for the show, but equipment malfunctioned, and the performance devolved into ‘an improvised happening’.Footnote 21

English sales of the record comparatively succeeded, mostly thanks to the unique packaging. Radio DJ John Peel fondly described his encounter: ‘When I saw their extraordinary first LP with its equally extraordinary sleeve and felt that, regardless of the music within, I had to acquire one.’Footnote 22 The sleeve and vinyl disc were transparent except for a black and white X-ray image of a hand clenched into a fist, communicating revolt or an industrial-zen look into man’s (and, being an album cover, advertising’s) emptiness, making the cover into one of Krautrock’s definitive images.

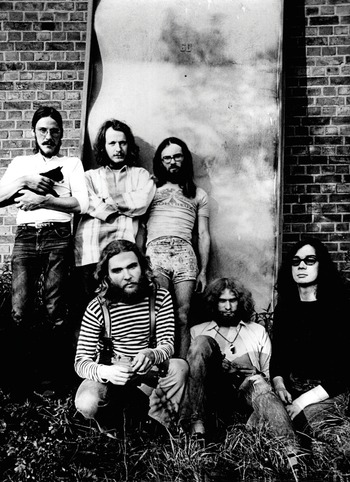

Illustration 10.1 Faust in Wümme, 1971.

Stepping Backwards: So Far (1972)

In response to Polydor’s dismay at the poor sales, Faust made quick changes, kicking out Meifert for being too ‘conventionally con-scientious’,Footnote 23 and making their second release far more accessible. In place of dizzying cut-ups and massive suites are songs with melodies and riff-focused, yet subversive jams. In the pastoral piece ‘On the Way to Abamäe’, listeners find they have been deceived by a flute revealing itself to be a synthesiser, complicating the boundary of mechanic and organic. Chord progressions throughout are complex, yet harmonious, comparable to Soft Machine’s particular style of jazz-rock. But snuck into the B-Side where Polydor might not be listening as closely, ‘Mamie is Blue’ assaults the listener with metallic percussion, radio buzzes, and distorted guitar, foreshadowing 1980s industrial and EBM.

The lyrics on So Far are naive and silly, yet subtly hint at their debut’s themes of alienation. ‘I’ve got my Car and my TV’ echoes Zappa’s critiques of consumerism, while ‘Mamie is Blue’ comments on Germany’s generational issues stemming from an inability to discuss denazification.Footnote 24 Most direct, lyrics from ‘ … In the Spirit’ read: ‘It’s never you / it must be others / sleeping tight / thinking of the past / I wonder how long / is this gonna last?’ While some may ask this question in relation to the track’s obnoxious, parodic Schlager-jazz, Faust attacks Germany’s inability to reconcile with its past. The lyrics attack individuals living in blissful ignorance, further problematising German identity rather than addressing Nazi issues.

So Far contains the Krautrock hit ‘It’s a Rainy Day, Sunshine Girl’. For seven minutes, the track features Diermaier’s monotonous quarter-note tom pattern, played on a deliberately dented drum,Footnote 25 before the introduction of jangly guitar, keyboards, and a chanted repetition of the title lyric. The naturalist lyrics and mantra of ‘A-Ohm’ at the end of each line suggest an imitation of Native American music. Bluesy harmonica and saxophone, a shift from Wüsthoff’s cacophonous, yet mathematically patterned free jazz (‘typical of the dry humour and systematic thinking of the northern German’,Footnote 26 said Péron) to a pastiche of Afro-jazz, are heard partway through the track, transporting listeners to an America of Faust’s making.

This is not the only example of Krautrock’s fetishistic interest in Native Americans, most recognisable when Gila named their 1973 album Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee after Dee Brown’s 1970 book. While motivations vary, one that held appeal for these German bands was the discovery of a common identity in ‘primal man’, idealising a connection between America’s Natives and Germany’s pagans. The reference brings awareness to the horrors of British and American colonialism, horrors that Brits and Americans supposed their own culture to have avoided – and are still less acknowledged than the Holocaust – and horrors that were topical to the unrest leading up to 1973’s Wounded Knee massacre. Recognition of this controversial appropriation is fundamental to understanding Krautrock’s goals and cultural context.

Perhaps due to the song’s length, Polydor didn’t think ‘Rainy Day’ would be a hit, instead releasing the album’s title track as a single. The album and single hit the press and, even with favourable reviews, sold worse than the debut.

The Eternal Now: Outside the Dream Syndicate (1973)

With tensions rising, the band distanced themselves from the label and sought to collaborate. Tony Conrad was in New York, playing violin in La Monte Young’s renowned minimalist band The Dream Syndicate. However, he was disillusioned, stating the scene was ‘too boring’.Footnote 27 By this time, he had gained some notoriety for his 1966 short film The Flicker, which consisted of strobing black-and-white frames for thirty minutes. The movie often made viewers sick, even giving them seizures, so Conrad justified: ‘I had felt that my own experience with flicker was a transporting experience in the way that movies affect the imagination at their best by sweeping one away from reality into a completely different psychic environment.’Footnote 28 This transcendental minimalism informed Faust’s jam-oriented aesthetics in their collaboration.

Outside the Dream Syndicate was recorded over three days in semi-improvised sessions led by Conrad, who found time to visit Wümme between showing his films and helping La Monte Young perform in Berlin. The songs were basic in construction, the first starting with a steady, monotonous drum and bass paired with long, buzzing drones. These drones would hardly change throughout the song, but Péron played ‘a deep bass note tuned to the tonic on Conrad’s violin and … the drummer “tuned” to a rhythm that corresponded to the vibrations’,Footnote 29 invoking the kind of harmonic and rhythmic interplay that would inform the Totalist-rock of Glenn Branca and Rhys Chrystham. The B-side is more energetic, but the harmonic content never shifts from the initial tonic key, the composition driven by atmosphere rather than any melody or riff.

Many listeners and critics argue the album expresses Conrad’s creative voice louder than Faust’s, but said evaluation fails to recognise in it Faust’s ethos: the embodiment of an eternal present. Outside the Dream Syndicate is The Velvet Underground’s drone-rock taken to a transcendental extreme, melody denied and exchanged for a complete focus on soundscape. The effect is a joined expression of Faust’s and Conrad’s ethos, pushing art’s boundaries to transform the mind.

Surprising Success: The Faust Tapes (1973)

With Polydor refusing to support Faust any longer, Uwe Nettelbeck reached out to Simon Draper and Richard Branson of the up-and-coming Virgin Records in London. The label started as a shop and mailing service importing Krautrock releases, but after finding success, became a professional label.Footnote 30 Mike Oldfield’s classic Tubular Bells was released alongside records by Gong, Tangerine Dream, and the new Faust release, which sold for forty-eight pence, the price of a seven-inch single. The radical idea: Nettelbeck would offer the tapes ‘for nothing’ if the label would sell the record for no profit.Footnote 31 The price would be just enough for the label to cover pressing costs, and the action would not increase profit, but notoriety for the band and label.

Part of the record deal allowed Faust to record at Virgin’s studio in Oxfordshire, forcing the band to leave for England. While the liner notes claim the tapes were compiled from Wümme recording sessions, Irmler claimed the collection ‘was not old material’.Footnote 32 Songs interrupt each other constantly, tracks often less than thirty seconds in length earmarking lengthier ones. This approach allowed Faust to introduce musical moments without concern for an over-arching continuity, compiling a barrage of experimental feats not to be reproduced until a decade later by post-punk bands like Swell Maps and This Heat.

The Faust Tapes’ longer songs are among Faust’s most lyrical. The laid-back psychedelia of So Far returns with the mature balladry of ‘Flashback Caruso’ and the softly plucked chanson of ‘Chère Chambre’, while ‘J’ai Mal Aux Dents’ screeches and noisily stumbles along. Lyrics beckon to a counter-cultural hope for peace and love, inviting listeners ‘bring our minds together’ and ‘stretch out time / dive into my mind’. A dichotomy forms between nature and industry. Nature evokes sensuality, as in the ‘rainbow bridge’ and ‘dancing girls’ of ‘Flashback Caruso’, or, in ‘Der Baum’ (The Tree), the description of a woman’s ‘bum’ (‘see her lying on the grass / must be a nice feeling for her ass’) and winter’s cold winds leading said ‘bum’ to bed. It is notable that ‘Baum’ translates to the phallic ‘tree’, the title’s pun joining the ‘bum’ with the ‘tree’.

Meanwhile, industry awakens an individualist apathy, as in the ‘man hard working song’ on ‘J’ai Mal Aux Dents’, the singer imitating a factory manager, snarling ‘If it means money / this is time … because you are crying and I don’t listen / because you are dying and I just whistle’, all behind the lamentation of pained teeth and feet. This is Faust’s strongest anti-capitalist statement, the singer mocking working-class listeners buying into an alienating, middle-class ideal.

The song’s refrain seems to change with repetition’s desensitisation, with Cope proposing the alternative interpretation ‘Chet-vah Buddha, Cherr-loopiz’ before Faust accepted another fan’s ‘Schempal Buddah, ship on a better sea!’Footnote 33 Phrases are de-territorialised from meaning and re-territorialised into idyllic nonsense, as if to suggest, even in the subtext of a joke, a hidden liberation in industry’s mechanical repetition only if its meanings can be reclaimed from selfishness and exploitation. The Faust Tapes concludes with ‘Chère Chambre’. Its French poetic prose suggests that – as society’s limits fail at the whim of human will – rather than to rely on empty promises of an easy life of creature comforts, we have to connect our pasts, both socio-culturally, and introspectively, to the changes that make up our selves.

Bearing a sleeve of reviews and a note claiming it was ‘not intended for release’ with ‘no post-production work’, the record was released in May 1973. Owing to the cheap price, the record was a hit, reaching number eighteen on Melody Maker’s chart before controversially being removed. Virgin Records did not calculate taxes into the cost of production, and 60,000 records lost the label and band 2,000 pounds.Footnote 34 Not all the listeners enjoyed the strange music, but many did, and with rave reviews and a (pre-recorded) performance on John Peel’s radio programme in March,Footnote 35 Faust toured England and France to promote the album.

The reputation of these live performances is legendary. Following the academic-inclined opener Henry Cow, Faust would clutter the stage with machinery, TVs, and pinball machines, upon which members might contribute a barrage of balls and bells into the soundscape. Sets would shift from written songs to more improvised, playful material, and would often stretch to over two hours in length, with varying sound quality. Members were noted to have been shy and nervous at times, perhaps owing to their history of fault-ridden shows, but were nevertheless a hit. Some shows were still a disaster, with hydraulic drills dangerously firing cement chips into an unsuspecting audience,Footnote 36 but these incidents only added to the band’s rising prominence.

Under Pressure: Faust IV (1973)

Faust’s fourth and final 1970s album was created out of demand for a new release to market with the band’s fresh surge in popularity. Members of Faust felt alienated, living in England and facing the stress of their first tour, contributing to a notable departure from their previous work’s abrasive experiments into conventional song structures, at least by Faust’s standards. This change in sound estranged Faust’s fans, who considered Faust IV a ‘sell-out’.Footnote 37

The album was recorded in June 1973, only one month after the last album’s release. Richard Branson invited the band to The Manor in Oxfordshire, his residential studio for the label. But all was not well, as band members disagreed with Branson’s desire for a marketable product, and recordings stretched further beyond the intended schedule. Nettelbeck dismissed the band to finish the album himself. Making up for lost time, ‘Picnic on a Frozen River’ from So Far was reworked with an increased tempo and intricate multitracking, and the previously performed ‘Krautrock’ and previously released ‘It’s a Bit of Pain’ bookend the album.

‘Krautrock’ opens with walls of pulsing fuzz, mixing various instruments into an indecipherable sound-mass. After a timeless seven minutes, the drums kick in, and the song, like Neu! before it, creates a simultaneous feeling of motion and stillness. Contrastingly, ‘Krautrock’ is neither meditative nor utopian, but violent and noisy. As Irmler said of the song, ‘We are not those “krauts” that you think we are and who you hate so much but we also don’t play that “rock” that you want to force upon us. So we said, let’s play a really heavy song and then we’ll call it “Krautrock”.’Footnote 38

The album continues with the dreamy ‘Jennifer’. Lyrics describe the titular woman with ‘burning hair’ and ‘yellow jokes’, while the bass follows with a laid-back, two-note jam. The sparse repetition creates a sense of unease, which collapses into cacophony. The Summer of Love has died, and in its wake grows a claustrophobic ennui, tension without the release of a cadence. Noise floods the composition before disappearing in a mess of detuned piano. The song is a bridge between the naïveté of the 1960s and the moody introspection of the 1990s.

The rest of the album consists of focused, energetic jams. Gone are the cut-ups, replaced instead by cohesive, melodic riffs interspersed by clouds of atmosphere. ‘Run’ (mistitled ‘Läuft … Läuft’) reminds one of Terry Riley’s minimalist synths, while anticipating Eno’s ambience, while ‘Läuft … Läuft’ (mistitled ‘Giggy Smile’) anticipates the orchestration of 2000s indie-folk. It’s hard to say the music is inventive, but Faust’s unique, playful style distinguishes these jams from blander jazz-rock stylings. The closer, ‘It’s a Bit of Pain’, incorporates a painful screeching noise to comically interrupt what sounds like The Byrds’ psychedelic country rock over a Swedish reading of Germaine Greer’s feminist manifesto The Female Eunuch.

Released with a cover of empty musical staffs, Faust IV was a commercial failure, Faust’s reputation and change in sound inhibiting new listeners and discouraging old fans respectively from buying the album. But to quote Pitchfork’s retroactive review, ‘the record’s rep has mostly recouped … it’s an easy starting point [into the band’s music]’.Footnote 39

Epilogue, or: The Death and Return of a Legend (1986) and Other Releases

After Faust IV’s commercial failure, Virgin Records was not happy with Faust’s refusal to create a marketable product. Some band members were bitter with Nettelbeck’s musical and packaging decisions, made without consulting the band. This caused Irmler and Sosna to quit and Nettelbeck to return to Hamburg. The remaining members replaced the missing musicians to tour again and, sensing their demise, returned to Germany.

Without Nettelbeck, Faust attempted one last recording and entered Musicland Studios in Munich, where Irmler recounts meeting the owner Giorgio Moroder, who had recently produced and co-written Donna Summer’s international disco hit ‘Love to Love You Baby’.Footnote 40 The band claimed to be from Virgin, directing any hotel and recording costs to the label, and recorded for a couple weeks. When Virgin received the bill, the band attempted to escape with the tapes, but were arrested by police and bailed out by their parents. A low-quality promotional cassette later surfaced as a bootleg.

Faust subsequently disappeared. Chris Cutler (Henry Cow) opted to re-release several Faust records on his Recommended Records label along with unreleased material, compiling 71 Minutes of Faust. The compilation is a notable addition to the band’s legacy, documenting quality songs from their demo up to their initial demise. Cutler also released Return of a Legend (1986) and The Last LP (1988), each repurposing material released through bootlegs or to be released on the BBC Sessions (2001).

Interest in Faust grew as more popular musicians (i.e. Merzbow, Joy Division, Radiohead etc.) cited them as an influence. Some members returned to record 1994’s Rien, an industrial-tinged take on their older material. The band have released albums since then, touring in two separate configurations and often collaborating with guest musicians. They have resumed elaborate live shows, providing a soundtrack for Nosferatu, or droning while separated by miles of desert in Death Valley, California.Footnote 41

It appears the band are not trying to surpass the historical impact their old material has had, nor repackage the music for a new generation, but are simply, as they always have done, making music for themselves. Indeed, if anything, the band are often attempting to solidify the legacy of their old material, playing fan favourites and keeping the music in circulation. Independent record label Bureau B has re-released nearly all 1970s Faust releases in 2021 in one box set, including the original Polydor demo, higher-quality and more complete recordings of the fifth album, and previously unreleased tracks from the original Wümme tapes, displaying the band’s obfuscated penchant for the space-rock jams of Pink Floyd or Gong. The release will prove essential to any efforts, scholastic or fan-driven, to understand the band’s explorations.

Throughout their career, Faust have functioned within the constraints of the contemporary popular rock band’s mythos, mirroring The Beatles’ studio experimentation, Jimi Hendrix’s use of noise, and The Beach Boys’ symphonic approach to composition. But Faust are remembered not for meeting the paradigms established by these bands, but by creating a new syntax that extended these paradigms, creating something recognisable, yet extreme and disruptive, a new space where the Romantic hero flourishes in poetic expression divorced from civilisation’s rigid repetitions and where a new identity, both German and international, can thrive. While not as technological as Kraftwerk, as professional as Can, or as cosmic as Ash Ra Tempel, Faust pushed a playfully experimental, yet existential edge into the fringes of experimental rock music.

Essential Listening

Faust, Faust (Polydor, 1971)

Faust, Outside the Dream Syndicate (Caroline, 1973)

Faust, The Faust Tapes (Virgin, 1973)

Faust, Faust IV (Virgin, 1973)