Ash Ra Tempel represent an archetypal kosmische Musik and psychedelic rock group, an ensemble who became strongly associated with the desire for musical experimentation and detachment from the Anglo-American rock of the 1960s. The original band and later solo projects have gained a cult following over five decades. Their music has inspired musicians in space rock as well as electronic ambient, techno, and trance. This chapter focuses on the original line-up of the band Ash Ra Tempel (1970–73), and Ashra, who have continued their legacy. In addition, the essay offers an overview of the solo production and collaborations of two founding members of the band, Manuel Göttsching and Klaus Schulze (1947–2022).

Manuel Göttsching, who studied classical guitar for years as a youngster,Footnote 1 grew up with rock music in the late 1960s, listening to Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton. With his friend Hartmut Enke (1952–2005), Göttsching played in various school bands, later the Steeple Chase Blues Band, which was inspired by blues but played more ‘free’ self-expression and psychedelic rock.Footnote 2

In 1969–70, a Swiss composer, Thomas Kessler, who had his own electronic music studio in Berlin, mentored Göttsching. Beat Studio was located on Pfalzburger Strasse, in the premises of a publicly funded music school. From Kessler, Göttsching received both a spark for electronic music and the basic skills of improvising and composing.

Another musician who wished to escape from Anglo-American formulas was Klaus Schulze, who had played drums in several rock bands in the late 1960s. The most notable of these was Tangerine Dream, in whose early line-up Schulze played until summer 1970, then joining Ash Ra Tempel. Like Göttsching, Schulze was also interested in electronics, sound manipulation, and recording.Footnote 3

Kessler’s guidance strongly affected the emergence of the ‘Berlin School’.Footnote 4 Although Kessler was not so enthusiastic about the bands’ aspirations to abandon the idea of composition, he continued channelling the musicians’ youthful energies. By autumn 1970, Ash Ra Tempel had already existed for three months, and Göttsching and Schulze joined the live sessions of Eruption, formed by Conrad Schnitzler and Klaus Freudig-mann. The experience gave them extra confidence since Eruption’s goal was to create music completely free of the hierarchies and conventions of existing styles.Footnote 5

Already in summer 1970, Enke had travelled to London to look for inexpensive used music equipment that was hard to find in Germany. He returned to Berlin with four large WEM amplifiers, which had been touring with Pink Floyd. Only the wealthiest bands and biggest festivals in Britain used similar cabinets. Schulze, who had just parted from Tangerine Dream, saw the towering amplifier set in the Beat Studio and suggested to Enke and Göttsching that they should form a band with him. Two weeks later, the band played their first gig.Footnote 6 Enke and Göttsching were only seventeen at the time.

Göttsching (guitar), Schulze (drums), and Enke (bass) formed a trio with the outlandish name Ash Ra Tempel, which translates as ‘the remnants of the temple of Ra’ (the sun god in ancient Egyptian mythology). The group positioned themselves in the emerging scene of new German rock as a band of psychedelia and experimental music. According to Göttsching, the activities of the band were intensive, creative, and free, but rather unprofessional.Footnote 7

In the latter half of the 1970s, Ash Ra Tempel performed regularly in Berlin, two or three times a week. The band gained a reputation as musicians who were able to improvise in front of an audience for several hours, communicating with each other only through their instruments.Footnote 8 In addition, they played at exceptionally high volume. According to Göttsching, the performances of Ash Ra Tempel were always long – from forty-five minutes to three hours – and purely improvisational. The only thing the members agreed on in advance was who would start playing. The band performed in restaurants as well as at community centres, galleries, and the Academy of Arts: ‘The audience liked that. We didn’t have any big advertisements, word got around. Perhaps the actual music was not that important at our first concerts. There were a lot of people and something happened, that’s why you went there.’Footnote 9

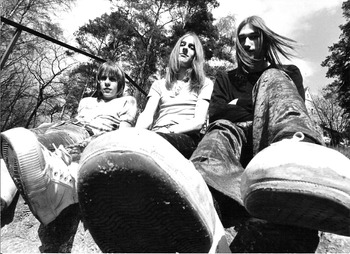

Illustration 13.1 Hartmut Enke, Manuel Göttsching, and Klaus Schulze of Ash Ra Tempel, 1971.

Entering the Empire of Kaiser

Overall, the music circles in Berlin were remarkably informal; jazz and rock musicians as well as experimental sound artists met and formed short-lived gig ensembles.Footnote 10 In his subsequent interviews, Göttsching has emphasised that from the beginning, Ash Ra Tempel were one of the bands who tried to get rid of the influence of Anglo-American blues structures and create new sounds and music.Footnote 11

With the help of label manager Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser, who was seeking out new bands in Berlin, Ash Ra Tempel were able to record their debut album for the Ohr label, founded in 1970 by Kaiser.Footnote 12 In early 1971, after overcoming many obstacles, sound engineer Konrad ‘Conny’ Plank helped Ash Ra Tempel in a recording studio in Hamburg. Göttsching remembers that Plank was very excited and proposed all sorts of technical experiments.Footnote 13

The self-titled Ash Ra Tempel album, released in June 1971, consisted of two improvised instrumental tracks.Footnote 14 Both ‘Amboss’ (Anvil) and ‘Traummaschine’ (Dream Machine) are intense but distinct works that transport the listener into the post-rock world. ‘Amboss’ progresses with Schulze’s hectic rhythm and Göttsching’s guitar playing, which distances the listener from rock and blues conventions. ‘Traummaschine’ is a twenty-five-minute jam that initially pulsates very softly, soothing the listener with gentle sounds and the ethereal vocals of Göttsching. After that, the trio cautiously wake up the listener while the rhythm becomes stronger. Supported by bongos and bass, the rhythm finally reaches a timeless cosmic sphere. Plank managed to create a strong sense of space for the whole album. Inspired by ancient Egyptian culture, the cover art of the LP’s very special folded front cover attracted attention.

Ash Ra Tempel continued playing to full venues in Berlin and elsewhere. The band also toured in Switzerland.Footnote 15 Their performances were much more intense than the studio sessions, as can be heard in a few surviving concert recordings from summer 1971, which Göttsching released in the 1990s. They used to immerse themselves in extended improvisations, based on Schulze’s fast drumming and Enke’s distorted bass-playing. On top of those, Göttsching played solos, roaring feedback, and rhythmic parts with the help of delay effects.Footnote 16 Schulze left Ash Ra Tempel right after the Swiss Tour in September 1971 and was replaced by drummer Wolfgang Müller. In interviews, Schulze stated that he would rather create music than play as a member of a band. However, his relationship with the other members remained close.Footnote 17

Ash Ra Tempel’s second album Schwingungen (1972) was recorded with a different line-up. Wolfgang Müller, a partner of Göttsching and Enke from the Steeple Chase Blues Band, joined the core group on drums and percussion. The change is particularly noticeable in the album’s first track, ‘Light: Look at Your Sun’, which introduced Manfred Peter Brück (a.k.a. John L.) as a guest vocalist. He was a former member of Agitation Free and a famous figure in the rock circles of Berlin. ‘Darkness: Flowers Must Die’ takes the listener into psychedelic despair and aggression, where both Göttsching’s guitar and John L.’s roaring vocals are processed with a heavy phaser effect. Additional guest musicians Matthias Wehler (saxophones) and Uli Popp (bongos) bring fresh overtones to an increasingly chaotic song.

The B-side of the album is very different. The seamlessly segued songs ‘Suche’ (Search) and ‘Liebe’ (Love) fill the entire side with cosmic ambiance. ‘Suche’ begins with Müller’s low-key vibraphone. Gradually rising from the background, Göttsching’s organ and guitar complement the band’s gauze-like weaving, slightly reminiscent of ‘Traummaschine’. The ethereal atmosphere is broken by Müller‘s drum beat, which rises from the distance in the front, restlessly wandering and then fading again. Göttsching’s occasional glissandos on guitar and his whining organ, as well as Müller’s cymbals, suggest an ascent such as in ‘Traummaschine’, but the album ends with a melodic ballad flavoured by Göttsching’s wordless singing and Müller’s cymbals. Kaiser’s trusted engineer Dieter DierksFootnote 18 recorded the album.

Psychedelic Encounters and Collaborations

In 1972, Kaiser and his partner Gerlinde ‘Gille’ Lettmann commercialised the concept of kosmische Musik and associated it with German electronic rock. The concept smoothly mixed the escapism and esotericism of psychedelic rock with the dreams of the space age, science fiction, and the soundscapes of electronic music. In particular, Ash Ra Tempel, Klaus Schulze and Popul Vuh, Wallenstein, and Mythos were labelled as cosmic music, through the marketing efforts of Ohr.Footnote 19

According to Harald Grosskopf, a drummer from Wallenstein who later played with both Göttsching and Schulze, the musicians involved in Kaiser‘s projects were people who, instead of radical political activism, chose to withdraw from society and focus instead on philosophy, drugs, and esotericism.Footnote 20 Hence, it was not a big surprise that in 1972, Ash Ra Tempel ended up in one of the most peculiar ventures in the history of German rock.

The band had dreamed of collaborating with Allen Ginsberg, but their attempts at establishing contact had not succeeded.Footnote 21 In 1972, Timothy Leary, a former professor of psychology at Harvard University and an evangelist for LSD, had ended up in Switzerland after escaping from prison in the United States. He had to hide and change his whereabouts to remain free, but he received help from the Swiss author and esotericist Sergius Golowin. Leary’s travelling companion included the British writer Brian Barritt, who considered himself a forerunner of the psychedelic counterculture.Footnote 22

Enke travelled to Switzerland to give Leary and Barritt the album Schwingungen. Neither of them knew of the band before, but they considered the music appropriate to advance their agenda and outlined the concept of the release with Enke. The goal was an album built on Leary’s theory of the seven steps of consciousness. Leary felt that Ash Ra Tempel could produce an appropriate soundtrack for his lyrics. Klaus D. Müller, the road manager of Ash Ra Tempel and a later collaborator with Göttsching, recalled that throughout the recording project, everything but the music was chaotic. A wide variety of people gathered around Leary and Barritt, and drug-driven parties and general unrest disrupted the project. Neither Leary nor Kaiser knew how the album would be structured and produced. At some point, Edgar Froese made an offer to Kaiser to step in for Ash Ra Tempel.Footnote 23

However, Göttsching and Enke had ideas about the music and their own role. With the help of Dierks, they managed to finish the recordings in three days at the Sinus Studio in Bern. Appropriately titled Seven-Up, the album featured various guest musicians. Micki Duwe took the lead vocals. Göttsching and Enke created the songs on A-side (‘Space’) in response to Leary’s recitations, but gradually the players got a grip, and the B-side of the album (‘Time’) sounds like the more familiar Ash Ra Tempel.Footnote 24 According to Göttsching, Leary was initially only supposed to write the text and recite a little on tape, but eventually he emerged as the leading vocalist.Footnote 25

At his studio near Cologne, Dierks mixed in some new instrument and vocal parts with various session musicians and singers and added electronic effects. Göttsching and Enke, along with lead vocalist Duwe, finalised the album with the help of several session musicians. In the end, as many as thirteen musicians and singers appeared on the album.Footnote 26 Released in 1973 under the Kosmische Kuriere sub-label, Seven-Up gained a reputation as a somewhat failed project the ideas of which looked better on paper than the music actually sounded. Furthermore, Leary’s desire to harness rock music as a vehicle of the LSD revolution, as was to be expected, did not lead to a societal breakthrough.Footnote 27

Reunion, the End of the Original Line-Up, and Schulze Solo

In 1972, Göttsching, Schulze, and Enke also became involved in Kaiser’s second collaborative project, where they, along with other musicians including Schulze, made music for Walter Wegmüller’s Tarot (1973) album. The Swiss-born artist drew inspiration from Tarot cards, and the album contained plenty of spoken words.Footnote 28 Released in 1973, Tarot remains Wegmüller’s only album, and many commentators, such as Julian Cope and David Stubbs, have valued its jam sessions.Footnote 29

Ash Ra Tempel’s fourth album, Join Inn, was released in 1973 and grew out of the hazy sessions of Tarot. Schulze played not only the drums but brought also his Farfisa organ and EMS Synthi A synthesiser to the studio. The album again consisted of a pair of long tracks. ‘Freak and Roll’ begins with wild jamming. Schulze’s hyperactive drumbeat is both dynamic and precise. Göttsching’s guitar moves seamlessly from blues solos to ethereal moods. Enke’s bass mourns mostly in the lowest register. Electronic glissandos and noises from the synthesiser pop up here and there.

The contrast with the song ‘Jenseits’ (Beyond) on the first side is enormous. The band take listeners into a dream space filled with vibrating guitar, organ, and synthesiser sounds, all coloured with tremolo, wah-wah, phaser, and delay effects. Enke joins the sonic landscaping with very slow bass patterns. On top of it all, Rosi Müller, Göttsching’s partner and muse at the time, slowly recites her text: ‘Let us dance on the wet grass. Look at me, please. Do you believe in peace? Sometimes it is so incredibly beautiful. Take me with you. Far away, you hear? The road is so long. Do you know the way – a little?’Footnote 30 Join Inn epitomises both sides of Ash Ra Tempel, with psychedelic visions and distressing bursts of energy, as well as serene sound spaces that invite the listener’s own imagination and emotions.

In February 1973, Ash Ra Tempel performed three concerts in West Germany and France. At these concerts, Schulze’s synthesisers seasoned the overall sound of the band and Göttsching’s playing was more sophisticated than earlier.Footnote 31 However, these concerts also marked the end of the original line-up. In the middle of the last concert in Cologne, Enke gave up his bass guitar and sat down on the edge of the stage. Afterwards, Enke stated: ‘Yeah, the music you played was just so beautiful I didn’t know what to play. I preferred listen to it.’Footnote 32 Troubled by many personal problems, Enke resigned from Ash Ra Tempel and never played again. He died in 2005 at the age of fifty-three.Footnote 33

Klaus Schulze embarked on a solo career at about the same time. His solo works allowed him to transcend the role of a drummer in a way that set free his creativity, which was not quite possible in his former bands.Footnote 34 Irrlicht: Quadrophonische Symphonie für Orchester und E-Maschinen (Will-o’-the-Wisp: Quadrophonic Symphony for Orchestra and E-Machines, 1972) is a dark pseudo-classical album, populated by treated orchestral recordings, organ sounds, and electronic droning. His music is both restless and static and manages to escape the conventions of musical time. Irrlicht somewhat approaches to Tangerine Dream’s Zeit (1972) but is even more alienating. Cyborg (1973) is perhaps his most radical work. It introduces the EMS VCS 3 synthesiser, which Schulze elaborates on intensively, creating soundscapes and pulses. Cyborg, which takes up the man-machine trope later to be developed by Kraftwerk, consists of four tracks, all exceeding twenty minutes in length. As in Irrlicht, the strongly meditative organ parts and the orchestral sections create a strong sense of murky cosmic ambience.Footnote 35

In these two albums, Schulze’s distinctive musical qualities began to take shape. Both build on soundscapes and moods created at the mixing desk. Obtrusive electronic sounds and a mysterious atmosphere distinguish Schulze’s early releases from the later ambient. Carefully created panning, delays, and echoes build Schulze’s space in an exceptionally vivid manner for the time. However, his early records still strongly divide opinions among his fans; some see them as experimental masterpieces, while others find them too extreme and challenging.

Cosmic Superfluity and the Departure from Ohr

In spring 1973, Schulze and Göttsching took part in recording sessions organised by Kaiser and Lettmann. The all-night, drug-driven jam sessions produced about sixty hours of recorded music for the future releases of the Kosmische Kuriere sub-label.Footnote 36 In 1972, Kaiser had run into trouble with his early Ohr partners, Bruno Wendel and Günter Körber, who, after leaving the company, had formed a competing record label, Brain Records. Kaiser and Lettmann sought to raise the profile of their releases with glaring slogans and marketing, merging psychedelia and LSD culture into music. Schulze and Tangerine Dream’s Edgar Froese especially disliked Kaiser’s marketing style.Footnote 37

Despite that, Schulze and Göttsching, and a few other musicians, such as Wallenstein’s Grosskopf and Jürgen Dollase, surrendered their jam sessions to Ohr. In 1974, Kaiser and Lettmann released some parts of the sessions on a series of albums entitled Cosmic Jokers, Galactic Supermarket, Planeten Sit In, and Sci-Fi Party.Footnote 38 After Kaiser edited the session tapes to a proper length, Lettmann added her own vocal parts to some of the songs. Despite receiving monetary compensation for the sales, many of the musicians, and Schulze in particular, protested against Kaiser and Lettmann’s arbitrary actions.Footnote 39 Flamboyant words and sci-fi tropes became a routine in the marketing. For example: ‘The time ship floats through the Galaxy of Joy. In the sounds of electronics. In the flashes of light. Here you will discover Science Fiction, the planet of COSMIC JOKERS, the GALACTIC SUPERMARKET and the SCI FI PARTY: That is the new sound, Space. Telepathy. Melodies, Joy.’Footnote 40

Such verbally overbearing marketing of Ash Ra Tempel’s music put the band in a strange light. Even their musician friends began to worry. For example, Froese thought Ash Ra Tempel lived ‘in a dream world’: ‘They think that everything will turn out okay, that the explosion of consciousness will conquer the world and all the problems will solve themselves.’Footnote 41 Göttsching had no problems with Kaiser, but he did not appreciate the idea about the mind-expanding effect of musical awareness, while Enke kept tirelessly explaining the matter to outsiders. Later, Göttsching associated the talk about a higher consciousness as part of the West German music culture of the early 1970s, where all rock music had to have some political content or social purpose. Göttsching himself just wanted to play his guitar.Footnote 42 Eventually, he also began to disassociate himself from the influence of Kaiser and Lettmann.

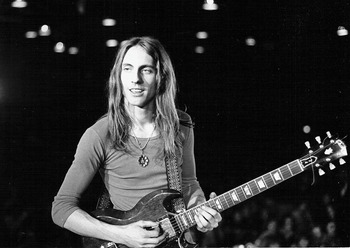

Illustration 13.2 Manuel Göttsching, 1973.

The Final Band Album and Innovations with Tape Machines

The last Ash Ra Tempel album on Ohr was Starring Rosi (1973). Featuring Göttsching on vocals, guitars, bass, mellotron, synthesiser, electric piano, and congas and Rosi Müller on vocals, speech, vibraphone, and concert harp, the album also featured Grosskopf on drums. In addition, Dierks played bass and percussion on a few tracks. This relaxed-sounding album is closer to New Age-inspired folk rock and light progressive rock than the band’s previous recordings.Footnote 43

In 1974, Kaiser’s cosmic empire was collapsing because of debts, lawsuits, and the departure of bands. Göttsching’s first solo album, Inventions for Electric Guitar (1975), remains one of the last releases by Ohr, which initially marketed the album as Ash Ra Tempel’s sixth album.Footnote 44 Later, it was re-released as Göttsching’s solo album. He recorded the album at home using only his electric guitar, a few pedals, and two open-reel tape recorders. The tape machine became a revolutionary musical instrument for Göttsching; with a two-track recorder and a guitar, he could create rhythmic delays, while a four-tracker captured his playing one track at a time.Footnote 45 This is how Göttsching made use of the skills of tape manipulation that he had learned from Kessler. Pulsating guitar playing and harmonious interaction of melodies layered on top of the rhythmic parts revealed the inspiration Göttsching took from minimalist composers, especially Steve Reich and Terry Riley.Footnote 46

Filling the entire A-side of the album, the track ‘Echo Waves’ is quite experimental with its rhythmic patterns and panning guitars. Still, it is unobtrusively captivating. The only guitar part that is classifiable as a proper solo only emerges at the end of a nearly eighteen-minute piece. The second track, ‘Quasarsphere’, is a subtle, melodic recollection of the early years of Ash Ra Tempel. On the B-side, ‘Pluralis’ weaves a swinging, discreetly evolving pattern of delayed rhythm guitars. The album features many of the elements upon which Göttsching has created music, especially in his solo career. These elements include repetitive patterns and theme variations, as well as melodic and rhythmic loops.Footnote 47

In December 1974, Göttsching and guitarist-keyboardist Lutz ‘Lüül’ Ulbrich from Agitation Free began to perform together as Ash Ra Tempel. In 1975, the duo played in West Germany, France, and Britain to audiences of up to several thousand people.Footnote 48 Especially in France, the band was still very popular. Contrary to Starring Rosi, the music of these concerts sprouted from the band’s earlier style. This especially applies to the songs that Göttsching and Ulbrich composed for the soundtrack of Philippe Garrel’s Le berceau de Cristal (The Crystal Cradle, 1976), a French experimental film that featured Nico, Dominique Sanda, and Anita Pallenberg.Footnote 49

The base of the soundtrack consisted of ethereal guitar patterns that cruise between organ and synthesiser sounds, sometimes merging into a harmonic aural environment. The overall sound is rather electronic, as the duo also played guitar synthesiser and a programmable rhythm machine. The film music remarkably resembles the style that Göttsching, Ulbrich, and Grosskopf adopted later in Ashra. The recording was issued only in 1993 as an Ash Ra Tempel release.

The Electronic Minimalism of Ashra

From 1974 onwards, the music of both Göttsching and Schulze is impossible to associate with the Krautrock of the early 1970s. Both artists moved further away from psychedelic rock and found inspiration in synthesisers and various genres of music. However, if we understand Krautrock not as a style category but rather as a quest for new means of expression, the same desire to experiment and discover still drove both musicians in the latter part of the decade.

Göttsching continued making music at his Berlin-based Studio Roma and began collecting ARP, Moog, and EMS synthesisers and sequencers. His first distinctively electronic album was New Age of Earth, released by French label Isadora in 1976. For this album, Göttsching played all synthesiser parts by hand.Footnote 50 However, at his 1976 solo concerts in France, he performed with pre-programmed sequencers and synthesisers.Footnote 51 The initial release was credited to Ash Ra Tempel, but after Göttsching obtained a record deal with Virgin in 1977, he shortened the band name to Ashra to avoid confusion. The new moniker was intended to serve all future projects, both solo and band efforts.

New Age of Earth and the following Blackouts (1977) were both solo albums, but for Correlations (1979) and Belle Alliance (1980), Göttsching invited his former partners Ulbrich (guitar and synthesiser) and Grosskopf (drums and synthesiser) to form a trio. Initially, the Ashra trio only assembled for a concert in London in August 1977. However, they would remain the heart of the band until the first decade of the twenty-first century.Footnote 52 New Age of Earth combined Göttsching’s interest in minimalism and the use of synthesisers. His arpeggios, chord progression, shimmering chords, and propulsive rhythms created an uplifting atmosphere. Songs such as ‘Sunrise’ and ‘Deep Distance’ push the listener forward. In ‘Ocean of Tenderness’, he created an ethereal sphere upon which the sound of guitar was able to float freely. The difference from Inventions for Electric Guitar is significant, as the guitars now played only a minor role. The album received a lot of praise from the music reviewers.Footnote 53

Göttsching has said that he wanted to get rid of the limitations of guitars.Footnote 54 However, in Blackouts, his guitar returned to the forefront and the synthesisers were to create a base for Göttsching’s long solos and other guitar parts. His playing not only echoed the Krautrock era, but it had also elements of jazz and funk. The side-long ‘Lotus Parts 1–4’ initially resembles the slowly evolving melodies and hypnotic groove of Inventions for Electric Guitar, but in the middle of the piece, electronic sounds are set free and tonal harmonies become supressed by sudden distortions and dissonance. Many reviewers also welcomed Blackouts.Footnote 55 These two albums started Göttsching’s intense home studio period. In addition, he toured with Schulze and Ashra and made music with Michael Hoenig (Agitation Free).Footnote 56 With the help of sequencers, Göttsching began to play long improvisations at concerts as well as at fashion shows.Footnote 57

Ashra fused pop elements into Correlations and Belle Alliance yet did not forget their psychedelic roots. Electronic instruments still played an important role in Ashra’s music, but in balance with the band’s playing. Many of the songs relied on funk and disco rhythms and bass lines, which Göttsching became mesmerised with while visiting the United States in the late seventies. Good examples of this are the tracks ‘Club Cannibal’ and ‘Phantasus’ from Correlations. The tracks ‘Screamer’ and ‘Aerogen’ from Belle Alliance are faster and more rocking. Not surprisingly, Virgin requested more material that could attract the pop audiences.Footnote 58

An Ambassador from the Synthetic Spheres: Klaus Schulze

In the mid-1970s, Klaus Schulze released many albums such as Blackdance (1974), Timewind (1974), Picture Music (1974), and Moondawn (1976). His music evolved to be more rhythmic and structured than his earlier output, and to some extent, it also began to resemble Tangerine Dream’s style in their early Virgin era. In the media, his music – along with Ashra’s and Tangerine Dream’s production – became labelled the Berlin School, which also referred to their common background as the apprentices of Thomas Kessler’s Beat Studio. From 1974 onwards, Brain and Virgin started to release Schulze’s works.Footnote 59 Gradually, his sound palette expanded to include acoustic instruments, such as flute, trumpet, acoustic guitar, drums, piano, and percussion, as well as the human voice.

For Blackdance, Schulze used a rhythm machine and a guest singer for the first time. On Timewind, he introduced a Synthanorma sequencer, an ELKA string machine, and EMS Synthi A and ARP 2600 synthesisers. Picture Music and Moondawn were coloured by the then-famous Minimoog synthesiser. As a live performer, Schulze was very conscious about the power of electronic instruments as visual and material attractors and used them extensively; he became famous for piling the stage set with synthesisers, string machines, and sequencers.Footnote 60

Schulze dedicated Timewind to his favourite composer, Richard Wagner. Later, Schulze returned many times to Wagner’s music with his electronic interpretations and compositions inspired by Wagner. The role of melodies, harmonies, and rhythm in Schulze’s music grew larger. However, a certain structural inertia and rhythmic immobilism remained his musical hallmarks through the seventies. The casting of vast sonic layers and building tensions without surrendering to a cathartic climax was typical of his musical language.

In the late seventies, Schulze expanded his repertoire to soundtracks in erotic films (Body Love, vols. 1 and 2 (1977)), historical figures (X (1978)), and works drawing on scientific fiction and fantasy (Dune (1979)). Mirage (1978) strongly manifested the liberating force of electronic music. For Schulze, the synthesiser represented a universal music machine that could overcome all restrictions of time, place, and social limitations. Schulze assured that electronic music could bridge the mind and the universe in a way that is neither a dream nor a hallucination. In the late seventies, Schulze achieved fame as a proponent of both electronic music and New Age music, which allowed him to build a relatively large and enduring fan base. In 1979, Schulze began releasing albums under the pseudonym Richard Wahnfried. With Time Actor (1979), he joined forces with the eccentric singer-musician Arthur Brown. In the 1990s, Wahnfried’s style began to resemble the electronic ambient and trance music of the time, and since then Schulze has gained recognition as one of the pioneers of trance.

From a New Opening to the Second Coming of Ashra

Göttsching’s first solo offering New Age Of Earth (1976) proved commercially successful upon initial release in France. This led Virgin to offer a lucrative nine-album deal and release the album worldwide in 1977. Blackouts (1978), too, sold very well. It was only with Correlations (1979) that sales figures stagnated, causing Virgin to release Belle Alliance (1979) in Germany only.

Göttsching’s home sessions did lead to an unpredictable and far-reaching acclaim. In December 1981, he recorded a piece in which a couple of synthesiser sequences revolved around two chords and a drum computer set the pace for the other machines. On top of that, Göttsching played guitar solos and riffs. He recorded a nearly hour-long piece directly on a tape without any doubling, mixing, or editing. A few years later, Göttsching offered the recording to Schulze’s Inteam label, which released E2–E4 in 1984.Footnote 61 Named after a typical opening move in chess and the droid R2–D2 of the Star Wars franchise, the release anticipated the rise of electronic dance music and influenced its evolution.

In 1984, German newspapers downplayed the release as an example of the inability of the vintage Krautrockers to regenerate.Footnote 62 Coincidentally or not, E2–E4 became a small hit on a radio, trendy stores, and DJs playlists in Europe and the United States. Surprised by the success, Göttsching assured that he had never thought of it as a dance piece.Footnote 63 Ultimately, Sueño Latino (1989), an album two Italian producers built upon the ‘E2–E4’ sample, established the song’s status as one of the early cornerstones of house and trance. Despite that, Göttsching, like many other Krautrockers, found himself on the margins, playing as a guest on other artists’ records and making soundtracks for fashion shows and television. Only in the late 1990s did the legacy and influence of the German electronic musicians of the 1970s became widely acknowledged.Footnote 64

In the 1980s, Ashra recorded only two albums. On Walkin’ the Desert (1989), Göttsching and Ulbrich revived their minimalist ambitions. The release of the exotica-style pop album Tropical Heat (1991) was delayed for five years. In the mid-1990s, a handful of companies began to reissue Krautrock albums, which by then had become rarities but increasingly attracted young fans of techno, ambient, and progressive rock. Interestingly, it was a French label that showed interest in the branch of the Berlin School under discussion here, with Spalax re-releasing the majority of the albums by Ash Ra Tempel, Ashra, and Manuel Göttsching.

Ashra’s second coming began in 1996, when Steve Baltes joined the line-up and helped to update the band’s sounds and live performances. Ashra updated their rhythms with electronic dance beats that brought plenty of new fans, for example in Japan where the quartet toured in 1997. Concerts in Germany and the Netherlands re-mobilised thousands of Ashra’s older fans.Footnote 65 Ashra released three concert albums between 1998 and 2002, as well as a compilation in 1996.

Göttsching has been active throughout the last three decades. In 1991, he released a previously unreleased solo album, Dream & Desire, recorded in 1977. Since the early 2000s, samplers and music software have allowed Göttsching to perform solo concerts with a guitar, portable computer, and keyboards.Footnote 66 In 2000, Schulze and Göttsching reunited to play in London at the Cornucopia Festival. The duo performed as Ash Ra Tempel and released a live recording, Gin Rosé (2000). In addition, they made even more music together and released an album entitled Friendship (2000). Also worth noting is the live DVD Ashra: Correlations in Concert from 2013. Göttsching remains very much active today, with several albums released in 2019 and 2021.

Conclusion

Ash Ra Tempel have gained their place in the history of rock music as a group of three musicians who did not compromise their vision but challenged many of the rock conventions of their time. Since the break-up of the original line-up, both Manuel Göttsching and Klaus Schulze have proved that the most intense and chaotic years of Krautrock in 1970–73 were eventually a fertile breeding ground for experimental and ambitious musicians – despite the volatility of the rock music trends, conflicting ideas, and disappointments in the music business.

In the music of Ash Ra Tempel, the influence of electronic music has especially manifested itself as an innovative mind-set and experimentalism. Exploration of new sounds and musical structures started even before actual synthesisers entered the studios and stage. Göttsching’s and Schulze’s solo careers have also introduced their earliest musical output to new generations of fans. Ash Ra Tempel’s fame as acclaimed pioneers of psychedelic and experimental rock has remained among musicians, rock journalists, and reviewers.

Essential Listening

Ash Ra Tempel, Ash Ra Tempel (Ohr, 1971)

Ashra, New Age of Earth (Isadora, 1976)

Manuel Göttsching, Inventions for Electric Guitar (Kosmische Musik, 1975)

Manuel Göttsching, E2–E4 (Inteam, 1984)

Klaus Schulze, Irrlicht (Ohr, 1972)

Klaus Schulze, Mirage (Brain, 1978)