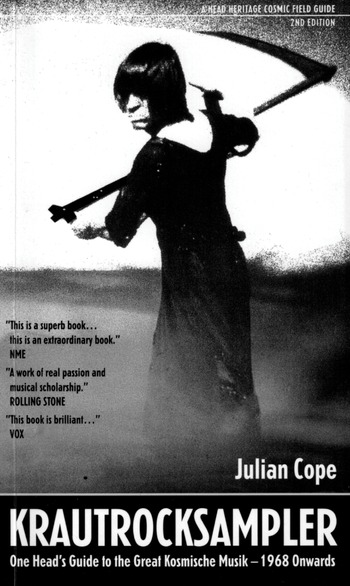

Within the realm of Krautrock, a number of notable artists – Can, Faust, Neu!, Cluster, Harmonia, Tangerine Dream, and a few others – are frequently heralded for providing ‘a sonic template for younger musicians’Footnote 1 with their ground-breaking approaches to music-making that have proven influential to successive generations of both avant-garde and mainstream musicians. Somewhat outside of this sphere of musical futurists are two interconnected bands – Amon Düül and Amon Düül II – whose stature and influence within Krautrock derive more from their conceptual underpinnings as a commune-based musical project and their recontextualization of rock music as a mechanism for examining a German cultural identity than from any particular musical innovation. Julian Cope, who used the artwork of their album Yeti for the cover of his Krautrocksampler, identifies Amon Düül II as ‘the group whose music continued to feel the pain of post-war Europe’,Footnote 2 while Ulrich Adelt describes their music as ‘a deterritorialized musical hybrid, challenging essentialized Germanness through its cosmopolitanism’.Footnote 3

Amon Düül II were also one of the Krautrock groups most able to transmit their ideals to an international audience – Lester Bangs declared their album Yeti ‘one of the finest recordings of psychedelic music in all of human history’Footnote 4 at a time when the prevailing critical attitude in the Anglosphere towards Krautrock was one of mild condescension. Yet Amon Düül (both I and II) were not significant merely for their reception abroad, for they were also highly public representatives of trends and legitimate social movements of the post-1968 West German counterculture, particularly the commune movement, while also engaging in alternative lifestyle practices collectively described as ‘the alternative concept of the politics of the self’.Footnote 5

Illustration 14.1 Cover of Krautrocksampler by Julian Cope.

Simultaneously, they engaged with their German cultural identity in ways both clever and problematic, embodying ‘both [the] promise and failure of the communal as a counter-model to the nationalist’.Footnote 6 Throughout the initial run of their career, from 1967 to 1981, Amon Düül and Amon Düül II typified each phase of the Krautrock movement, starting with the highly conceptual avant-gardism of the early days, the innovative and influential ‘classic’ period of 1969 to 1972, and the genre’s slow subsumption into the mainstream of modern rock music from 1972 onwards.

The Founding of a Musical Commune: 1967

Amon Düül was formed in a flat on Munich’s Klopstockstraße in 1967. The core founding members included brothers Peter and Uli Leopold, Chris Karrer, Falk Rogner, and Christian ‘Shrat’ Thiele, all of whom came from affluent families and were acquainted from their boarding school days. They also shared an interest in the popular rock and beat music of the day as well as avant-garde jazz and traditional music from various cultures. By the end of 1967, this core group of flatmates moved into a stately house on Prinzregentenstraße, a location that would provide an expanded sense of communal possibilities. By April of 1968, the loose collection of amateur musicians living in the house had begun performing under the name ‘Amon Düül’.

Munich in the late 1960’s was not particularly receptive to radical musical happenings, and the members of the Prinzregentenstraße commune frequently found themselves at odds with the suffocating conservatism of the region. Band members were disturbed by the hostility they faced in their home city, with Shrat recalling people screaming ‘you ought to be gassed!’ from open windows.Footnote 7 Guitarist John Weinzierl explains how this stark cultural divide informed the politics of a musical commune: ‘In those days, there were bloody Nazis around all over the place. … We didn’t have guns or the tools to chase them away, but we could make music, and we could draw audiences, we could draw people, with the same understanding, with the same desires.’Footnote 8 These desires corresponded to ‘a violent catharsis’ in the musical expression of the German counterculture, ‘a sometimes unacknowledged sense of wanting to purge the past and to establish a new youth cultural formation through experimental music’.Footnote 9

Amon Düül was not conceived as a rock band as such, but as an alternative lifestyle in and of itself, with the earliest Amon Düül performances taking the form of multimedia exhibitions involving all members of the commune, even the handful of children living there. Peter Leopold recalls, not entirely fondly, the concept’s genesis: ‘The ideologues [in the commune] came and said “now everyone has to make music”. … That was at first a social requirement. … Then we tried to transpose it to the stage.’Footnote 10 The concept of a commune of like-minded individuals who lived and made art together proved an attractive alternative for young people seeking to escape a staid traditionalism. Even the name Amon Düül demonstrates the group’s desire to shatter conventions: ‘Amon’ derives from the ancient Egyptian deity, while the band had this to say about ‘Düül’ in a 1969 interview with Underground magazine: ‘“Düül”, well, that’s a word that’s never existed before, with two ü’s – not in German, nor English or Japanese or anywhere else.’Footnote 11

Amon Düül’s riotous and shockingly loud early performances immediately brought them notoriety in their home city of Munich. The presence of supermodel and underground sex symbol Uschi Obermaier, who sang and played maracas in the group’s early days, also boosted their fame, and established perhaps the first link between Amon Düül and some of the more politically engaged communes in West Germany. Obermaier and her boyfriend Rainer Langhans were the public faces of Kommune 1, originally founded in Berlin, which engaged in both serious-minded political actions as well as provocative pranks. Kommune 1 shared some members as well as a certain political impetus with the Amon Düül commune.

Kommune 1 favoured attention-grabbing demonstrations and performances over direct armed engagement with the establishment. Similarly, Amon Düül commune member and occasional band manager Peter Kaiser describes the political leanings of the band as ‘anarchists, but only verbally’.Footnote 12 Kaiser, a member of the left-wing Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (Socialist German Student Union, or SDS), also claims that Amon Düül’s first public performance took place at a demonstration in which the SDS occupied Munich’s Academy of Fine Arts, and that the band’s performance in particular served as a catalysing moment for the nascent commune movement.

Sabine von Dirke’s analysis of the unified personal-political approach that characterized the West German counterculture at this time proves apt in explaining Amon Düül’s appeal as a uniquely multifaceted musical, political, and cultural entity: The counterculture

combined a revolution of lifestyles with new cultural and aesthetic paradigms as well as with political demands. … Mainstream culture viewed even explicitly non-political aspects of this middle-class counterculture – for example, a hippie lifestyle – as political and potentially dangerous for the hegemony.Footnote 13

Peter Kaiser’s comment about Amon Düül’s ‘verbal’ anarchism overlooks the band’s desire and ability to transmit a political ideology, albeit a vague one, through their music itself. Alexander Simmeth describes this as ‘a political self-conception, expressed through the breaking of established musical structures’,Footnote 14 while the band members themselves explain in a 1971 press release: ‘We were able to achieve an articulation of a fundamental critique of the existing system because we had set out a model of the counterculture with the music.’Footnote 15 While this model overlaps with that of Kommune 1 or the SDS, who similarly promoted alternative lifestyles, the arts, and engagement in political demonstrations as the most pragmatic and effective courses for effecting social change, Amon Düül’s standing as Germany’s most famous commune band (perhaps barring Berlin’s Ton Steine Scherben) and their wide network of occasional members and fellow travellers sometimes brought the band into contact with the armed terrorists at the extremist end of the West German counterculture.

Like Kommune 1, whose co-founder Dieter Kunzelmann eventually tired of non-violent pranks and actions and joined the militant Tupamaros West-Berlin,Footnote 16 members of Amon Düül held political beliefs spanning the spectrum of radicalisation. Chris Karrer was once arrested for something as innocent as throwing bonbons during a university demonstration, while producer Olaf Kübler once remarked of Peter Leopold, ‘If he hadn’t been a drummer, he probably would have become a terrorist.’Footnote 17 It is unclear to what extent any members of Amon Düül held militant views or sympathised with the ‘Rote Armee Fraktion’ (Red Army Faction, or RAF), a radical left-wing terrorist faction also known as the Baader-Meinhof Group, but the band was, at the very least, acquainted with the leaders of the RAF. Singer Renate Knaup recalls an incident from 1969, when RAF leaders Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, and Ulrike Meinhof attempted to hide out with the band while on the run following an arson conviction.Footnote 18 She angrily ejected them from the property, suggesting that the band’s radicalism stopped short of abetting accused terrorists.

Two Bands, Two Concepts: 1968

Band logistics and varying levels of musical proficiency determined that most of the members of the early incarnations of Amon Düül wound up playing some kind of percussion instrument, and it is a distorted wave of crashing, clattering percussion that dominates the early Düül sound. The consistently jagged and abrasive nature of the music reflected the chaos of the band members’ lifestyles and personal relationships, and by the time the group was ready to enter the recording studio, it had split into two acrimonious factions. Uli Leopold became the de facto leader of Amon Düül, while Karrer, Rogner, Shrat, and a handful of other members were ejected from the commune just before the group was set to record the jam session that would provide the material for four of the five albums released under the Amon Düül name. Those members also missed out on the group’s performance at the Internationale Essener Songtage, a landmark festival that served as a major catalyst for Krautrock and the West German counterculture in general. Peter Leopold, one of the most tempestuous personalities in a group filled with them, was the only member to keep one foot in both camps.

Rather than embarking on a different musical project altogether, the cast-off Düüls decided to continue to expand and refine the concept of commune-based rock music. Though the names Amon Düül and Amon Düül II suggest two distinct eras of a single group, the two formations actually recorded and performed concurrently, and pursued two different conceptual goals. The original Amon Düül was conceived of first and foremost as a commune, and to prohibit certain unmusical communards from participating in the music-making would have violated the commune ethos: as biographer and friend of the band, Ingeborg Schober explains, ‘That was the story of Amon Düül – that the people who made music there really couldn’t [make music] at all, but they had the desire to do so.’Footnote 19 It is questionable whether one can even definitively categorise Amon Düül as rock music, given that typical verse–chorus–verse song structures are entirely absent, the largely wordless vocals are shrieking and wailing, and the rhythms are pounding and monotonous.

Amon Düül’s first album, Psychedelic Underground, was released in 1969, though the recordings date from 1968, just after the departure of the future members of Amon Düül II. The album’s rhythmic monotony and loose-yet-controlled sense of propulsive energy puts it in contention for the title of first true Krautrock album. Schober asserts that the very term ‘Krautrock’ originated in the German rock scene and derived from the album’s track ‘Mama Düül und ihre Sauerkrautband spielt auf’ (Mama Düül and her Sauerkraut-Band Start to Play),Footnote 20 though surviving band members like John Weinzierl vigorously reject the notion that the band’s music ought to be included under this label.Footnote 21 The recordings from that single 1968 jam would later be edited and spliced together for three more Amon Düül albums – Collapsing Singvögel Rückwärts & Co. (1969), Disaster (1972), and Experimente (1982). This musique concrète-like reassembly of disparate bits of music aligns Amon Düül with other significant studio tinkerers of the era, such as Can and Faust.

The Amon Düül commune continued to exist in varying configurations until the mid-1970s, but the group would record only once more, in 1970, and this session would form the basis of Paradieswärts Düül, released in 1971 by Ohr. This album finds the band in a somewhat more subdued mood than on the 1968 session, with a largely acoustic psychedelic folk sound. Shrat and Weinzierl of Amon Düül II are credited as guest musicians on the album, while Leopold appears as a guest on Amon Düül II’s album Yeti from the same year, suggesting that the initial prickliness between the two Düüls following their split did not take long to soften. By 1973, the original Amon Düül had splintered even further, and only Amon Düül II remained to carry forwards the musical impetus engendered in the flat on Klopstockstraße in 1967.

Emblemising the Counterculture: 1969–1972

While the original Amon Düül was a resolutely avant-garde musical project and would never have been likely to attain much mainstream attention or credibility in any music scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Amon Düül II’s sheer countercultural force of personality and visceral ‘acid rock’ sound engaged a record-buying public far outside the worlds of political communes and academic avant-gardism. The release of their first LP, Phallus Dei, in 1969 immediately established them as one of the forerunners in the wave of young German musicians exploring ‘a new legacy in sound that reconnected with older German traditions’Footnote 22 – a sound that would soon come to be known as Krautrock.

Phallus Dei, with its incendiary title (God’s Penis in Latin) seeming especially galling for a band from the heart of Catholic Bavaria, was an act of musical provocation that thrilled increasingly agitated countercultural types throughout Germany. That the album was warmly received in these circles speaks to a growing pessimism and paranoia in the German counterculture – the lyrics, album artwork, and overall tone of the album are decidedly violent and forbidding. Though by 1969 many rock artists had moved on from the simple pleasures and lysergic silliness of the Summer of Love’s first wave of psychedelic rock and begun to plumb darker sounds and lyrical themes, Amon Düül II’s complete indulgence of these trends in their lyrics sets them apart from their peers. From ‘Phallus Dei’: ‘The raper he is raping / The victim is crying still / The priest he is escaping / He’s creeping ‘round the mill.’

That these lyrics appear on the title track of the first album ever released under the Amon Düül II name is no fluke. The band’s fascination with scenes of violence and the macabre prevails throughout their discography, though it is rarely articulated as audaciously as on Phallus Dei. Another track on the album, ‘Dem Guten, Schönen, Wahren’ (Dedicated to the Good, the Beautiful, the True) is narrated from the perspective of a child rapist and murderer, and pointedly features German lyrics, ‘recalling traditions of German murder ballads’.Footnote 23

It is not only the lyrics that mark Phallus Dei as a conspicuously sinister outing for a late 1960s rock group. The music itself is ferocious, challenging, and much like the sound of Amon Düül, vaguely ritualistic. Percussion still figures heavily in shaping the Düül sound, with frantic tablas and bongos augmenting Peter Leopold’s propulsive fills, with which he shapes lengthy cycles of riffing and improvisation into something raga-like. Meanwhile, melodies are carried by an array of electric and acoustic guitars, violins, twelve-string bass, and organ, sometimes all played in unison in moments of stormy intensity. The album’s occult mood and sense of mystery is taken further by producer Olaf Kübler’s studio manipulations – isolated vocal and instrumental tracks echo and slice through the mix, inducing a feeling of creeping paranoia.

By the recording of Phallus Dei, Peter Leopold, Chris Karrer, Shrat, and Falk Rogner had been joined by a number of additional members who would be influential parts of Amon Düül II’s creative nucleus on-and-off throughout the band’s career. Guitarist John Weinzierl would prove a stalwart, if occasionally combative, contributor across most of the band’s albums, while Olaf Kübler, a more polished and professional musician than most of the other members, would make his presence felt as a producer and occasional saxophonist for years to come. However, it was the introduction of Renate Knaup, vocalist and the closest thing Amon Düül II ever had to a frontperson, that would perhaps most distinctively shape the future Düül sound.

Her ability to marry her operatic tendencies to rock’s power lent the band a grandiosity that the former Amon Düül never could have, nor would have, attained. Knaup’s influence also had a hand in gradually pushing the band closer to the rock mainstream during the 1970s: ‘I had really beautiful songs in my head, but “beautiful” in the sense of normal, not this freak stuff we produced in the beginning.’Footnote 24 Her talents are under-utilized on the band’s early, more experimental albums, where she is largely constrained to wordless whooping and shrieking, though on later albums she stands out as a commanding vocalist in the context of a somewhat less avant-garde rock group.

Since the split between the two Düüls had occurred, most of the core members of Amon Düül II had been half-heartedly pursuing another attempt at a communal coexistence in a run-down villa in Herrsching am Ammersee, a posh lake resort town outside Munich. Visitors to Herrsching noted that any pretence of unity and oneness had gone out of the band, and explosive arguments became more and more frequent as garbage and filth accumulated in the villa. Eventually, the band decided to abandon Herrsching for the tiny village of Kronwinkl near Landshut, also on the outskirts of Munich, a pastoral setting that would acquire an almost legendary reputation as the location where Amon Düül II would ensconce themselves to produce some of their finest work, including their second album, Yeti, released in March 1970.

Yeti opens with the thundering riffs of ‘Soap Shop Rock’, one of Amon Düül II’s most iconic tracks, and an encapsulation of the band’s cataclysmic energy during this period. Once again, the listener is treated/subjected to a scene of disarming violence: ‘Down on the football place / I saw my sister burning / They tied her on a railroad track / And made her blue eyes burning.’

‘Soap Shop Rock’ runs to nearly fourteen minutes, spans several movements and codas, and could well function as a primer on everything that characterises Amon Düül II: phantasmagorical lyrical scenes, a blend of passages of free improvisation and operatic structure, a richly textured and varied auditory experience, and simply rocking out. Yeti showcases a guitar-driven hard rock sound akin to that of British space rock pioneers Hawkwind, with whom Amon Düül II shared a bassist – Englishman Dave Anderson played on both Phallus Dei and Yeti – as well as Black Sabbath and some of the lesser-known groups in the nascent heavy metal scene, who also toyed with similarly macabre lyrical themes. Indeed, while various Krautrock groups are regularly cited as influences on electronica and indie rock, Amon Düül II is one of the few that also left a significant mark on heavy metal. Weinzierl recalls his pleasant surprise at a festival with Slayer in Sweden in recent years, when ‘all these metal guys … just wanted to say, “You inspired me!”’Footnote 25

‘Soap Shop Rock’ is an imposing set piece, but the rest of Yeti is no less impressive – it contains all of the same components as Phallus Dei, but they are tighter, more coherent, and more accomplished than before. The album also gave the band their first single, ‘Archangels Thunderbird’, the most conventional rock track on the album, but a masterful piece of expressionistic hard rock nonetheless, thanks to Renate Knaup’s commanding vocals (comparing Knaup’s vocals with the bizarrely electronically processed vocals on ‘Eye-Shaking King’ three tracks later, the two polarities of Amon Düül II become apparent). Tracks like ‘Archangels Thunderbird’ also helped the band garner attention outside of West Germany – write-ups about the band had already appeared in Melody Maker by 1970,Footnote 26 and American rock critic Lester Bangs wrote about them as early as 1971.Footnote 27 Though Amon Düül II were one of the first groups pasted with the faintly condescending ‘Krautrock’ label in Britain, they drew a devoted following there and shared a fanbase with similarly avant-garde-leaning progressive rock groups such as Hawkwind and Van der Graaf Generator.

Over the next two years, Amon Düül II would release three studio albums in quick succession – Tanz der Lemminge (Dance of the Lem-mings) in 1971, and Carnival in Babylon as well as Wolf City in 1972. This run of albums would solidify the band’s reputation as one of the premier progressive rock groups in continental Europe. Meanwhile, chaos continued to reign behind the scenes, as interpersonal conflicts at the Kronwinkl house led to yet another series of personnel changes – producer and DJ Gerhard Augustin estimates that over 120 different members passed through the two Amon Düüls over the yearsFootnote 28 – and arguments about songwriter credits and copyrights persisted throughout those years.

A number of unsettling events further exacerbated the turmoil: in March 1971, a fire broke out during an Amon Düül II concert in the Cologne nightclub KEKS. Two concert-goers were killed, another 500 were injured, and almost all the band’s instruments and equipment were destroyed. In December of the same year, several band members were held at gunpoint by police under suspicion of being members of the RAF. Only days after the run-in with the police, Amon Düül II shared a bill with Hawkwind at the Olympia in Paris. Following Hawkwind’s set, a spontaneous political demonstration in the crowd rapidly turned into a riot, which culminated in Amon Düül II bassist Lothar Meid hurling a drum at some unruly audience members. The band then launched into one of the most well-reviewed sets of their career, prompting Ingeborg Schober to note that: ‘[O]ne is inclined to believe that as long as chaos existed around the band, they were instantaneously able to reach soaring heights, and as long as order and calm reigned around them, the chaos broke out amongst themselves.’Footnote 29

Schober’s assertion is proven correct by the excellent run of albums Amon Düül II put out around this time. Tanz der Lemminge is more varied, more proficient, and more representative of trends in progressive rock than the two albums that preceded it. The double album features three extended suites, which are further divided into seventeen movements ranging in length from under one minute to over eighteen minutes. The suite taking up the first side, ‘Syntelman’s March of the Roaring Seventies’, was composed primarily by Karrer, and his appreciation for folk music shines through more buoyantly than on previous recordings. The B-side, ‘Restless Skylight-Transistor-Child’, composed mainly by Weinzierl, finds the band exploring new territory, as electronically processed organs and a Mellotron – listed in the album notes simply as ‘electronics’ – introduces a new layer of the Amon Düül II sound that they would embrace more fully on future albums. This side also blends hard rock guitars, sitar, and droning violins into the heady mix, marking the nearly twenty-minute suite as one of the most creative and inspired moments of the band’s career. The C- and D-sides are taken up by ‘Chamsin Soundtrack’, a largely improvised thirty-three-minute feast of psychedelic indulgence that serves as a signpost moment for the band: this is essentially the band’s last dalliance with ‘acid rock’. That is to say, the raw, untutored, largely improvisational sound of the first two albums would now come to be replaced by more polished, progressive and compositionally bound structures, as heard on the band’s next two albums, Carnival in Babylon and Wolf City.

Due to one of the band’s countless personnel shakeups, Renate Knaup is credited only as a guest vocalist on one brief track on Tanz der Lemminge, but she would return as a full member on Carnival in Babylon and Wolf City and become an essential part of the band’s sound and identity from then on. So too would bassist and vocalist Lothar Meid, who first appeared as a full member on Tanz der Lemminge, though he had previously toured with the band. Meid was an experienced musician who had played with jazz musician Klaus Doldinger and co-founded Embryo, the jazz- and world music-inspired Krautrock ensemble from Munich. Meid’s compositions tended to be somewhat more pop-oriented than those of the founding members, as evidenced by his later work with mainstream German classic rockers Peter Maffay and Marius Müller-Westernhagen.

Carnival in Babylon, released in January 1972, is a transitional album with some satisfying moments, though it feels like a relatively minor entry in the Amon Düül II catalogue. It does, however, set the stage for the shimmering progressive elegance of Wolf City, an inspired synthesis of the laissez-faire experimentation of earlier albums and the tighter, more song-oriented path the band was starting to tread. ‘Wie der Wind am Ende einer Straße’ (Like the Wind at the End of a Street), an instrumental from the second side, is a mellifluously layered blend of proto–New Age kosmische Musik and Indian influences, and, according to Falk Rogner, represents the only time that the band actually recorded while under the influence of LSD.Footnote 30 The album closes with the serene ‘Sleepwalker’s Timeless Bridge’, a minor masterpiece of progressive rock, spanning several movements within just five minutes, with Mellotron textures that single this out as one of Amon Düül II’s gentlest and most forward-looking compositions.

Exploring National and International Identities: 1973 until Today

Wolf City is not the last notable Amon Düül II album – their next three studio albums, Vive la Trance (1973), Hijack (1974), and Made in Germany (1975), all have strong moments. Vive la Trance gloomily predicts a sci-fi apocalypse and describes horrific bloodshed in the Mozambican War of Independence on the fearsome ‘Mozambique’, perhaps the band’s most obviously political track, with lyrical depictions of ‘the white beast … in the villages, dealing only in death’, and an exhortation to ‘unite and fight’. Hijack, on the other hand, is upbeat and accessible for an Amon Düül II record and is clearly inspired by Roxy Music and Ziggy Stardust–era David Bowie. Meid’s influence is apparent throughout the album, which bears similarities with his side projects Utopia and 18 Karat Gold from 1973, both of which also feature a number of other Amon Düül II members.

One release from this era that satisfyingly captures some of the visceral energy of the old Düül is the band’s first live album, Live in London (1973). Consisting of spirited adaptations of fan favourites from Yeti and Tanz der Lemminge, it draws a stark contrast between the psychedelic freak-outs of the band’s earlier work and their more polished contemporary studio work. The album is also significant for its provocative cover art: a militarized, Stahlhelm-clad demon looms threateningly over Big Ben and the Tower Bridge. Such an obvious reference to the Third Reich seems uncharacteristic of a band as outspokenly opposed to Nazism as Amon Düül II, though the satirical intent of the artwork is made clearer in the context of a disagreeable incident from 1972: the band’s first ever performance in Britain was marred by an attendee who loudly shouted ‘Heil Hitler!’ and gave a Nazi salute during every song break.Footnote 31 Recent reissues of Live in London have featured different, less incendiary cover art.

It may have been this incident that started the group contemplating their identity as a German band and the stereotypes and ignorant jokes they could expect to face from international audiences. Their last notable album, Made in Germany, is an odd, amusing exercise in grappling with German national pride and shame. Originally intended as a concept album based on German history, it was aimed mainly at the American market, an audience for whom Amon Düül II and Krautrock in general were still largely unknown. Olaf Kübler claims to have previously presented the Düül side project Utopia to some American record label executives under the name Olaf & His Electric Nazis.Footnote 32 That idea was ultimately canned, but it seems that the band had fixated on a satirical embrace of German history as the way to reach a broader international audience.

Made in Germany features humorous songs about Kaiser Wilhelm II, Ludwig II of Bavaria, and Fritz Lang, along with many playful references to the ‘kraut’ label – ‘the krauts are coming to the USA’ – as the band gleefully exclaims on the country-tinged ‘Emigrant Song’. The album is musically diverse, drawing heavily from glam rock and musical theatre, with a sense of whimsy that is dampened somewhat by the inclusion of a skit featuring a mock ‘interview’ with Adolf Hitler. Ironically, the edgy double concept album the band was sure would pique the interest of American audiences was trimmed to a single LP for the American release, with the Hitler skit being removed altogether.

Following Made in Germany, Amon Düül II released four more largely lacklustre albums before disbanding in 1981. The final album of the band’s original run, Vortex (1981), is somewhat of a return to the sinister Düül sound of yore, though it sounds overproduced and rather lifeless. Two years later, in 1983, the album Experimente appeared under the original Amon Düül name, featuring the last of the studio floor cuttings from the 1968 session that spawned four of their five albums. Comparing Vortex and Experimente is jarring in that the chaotic, amateurish jamming of the early Amon Düül actually sounds timelier and more ground-breaking in the context of post-punk and early industrial music in 1983 than the bloated prog pop of latter-period Amon Düül II.

After the band’s initial breakup in 1981, Weinzierl forged onward with a new incarnation of Amon Düül II, often referred to as Amon Düül UK, featuring members of Hawkwind, Van der Graaf Generator, and Ozric Tentacles, while a more complete version of the band has reunited from time to time for short tours and two new studio albums in 1995 and 2010. Karrer, Weinzierl, and Knaup all remain involved with the group and perform occasionally to this day.

As a Liberty Records press release for Phallus Dei explained in 1969: ‘Amon Düül II understands itself as a community. … The music of Amon Düül II is inseparable from the history of the group, their sociological basis, and their societal experiences.’Footnote 33 Or, as the members themselves put it in a later press release for Tanz der Lemminge:

We want to show with our group that it’s possible to live together, work together, and overcome difficulties together and nevertheless remain an autonomous individual. We want this truth, which dictates our conscious and collective action, to be conveyed through the music and to reach the public.Footnote 34

Judging by the successive generations of fans and musicians who continue to rediscover this music, the message has been received.

Essential Listening

Amon Düül, Psychedelic Underground (Metronome, 1969)

Amon Düül II, Phallus Dei (Liberty, 1969)

Amon Düül II, Yeti (Liberty, 1970)

Amon Düül II, Wolf City (United Artists, 1972)