Kim Young-min (Gim Yeong-min), the former CEO of SM Entertainment, at a conference in 2015, remarked, “The business of SM Entertainment ranges from scouting and training talents, artist management, and promotion to music marketing and publishing, recording production and distribution, and concert production, etc.” Then he turned to the audience with an improvised question without necessarily expecting meaningful responses: “What kind of company is SM?”1 Even the impresarios of K-pop did not know how to define the specific characteristics of K-pop companies.

In fact, K-pop companies wear multiple hats, and their functions have evolved over several decades, shaping their versatile practices today. The main focus of this chapter is to provide a close study of the forms, characteristics, and operations of music-related companies during the 1990s, which paved the way for the current K-pop companies’ global emergence and their star-making practices. Korean companies have insisted on their international outlook and labeled their products “global,” although the organizations, functions, and business range of K-pop companies such as SM Entertainment differ significantly from those of their counterparts in North America, Europe, and Japan. Some scholars uncritically agree, dubbing K-pop a “global music genre.”2 Yet, given that the major K-pop companies widely known today entered the global music market only in the 2000s, there is need to examine how their predecessors, generally known as record companies (eumbansa), operated when the market for Korean pop was largely domestic.

In order to address the rapidly evolving Korean popular music industry of the 1990s, I first investigate various names that were used to address the industry participants and what they connoted in terms of power dynamics and working relations among them. The terms “K-pop” and “entertainment companies” here apply only to postmillennial Korean pop. The music producers in a literal sense were officially named “enterprise companies” (gihoeksa) and each company was called an “enterprise” (gihoek).3 Sun Jung chose “entertainment planning company,” which seems to be the direct translation of yeonye gihoeksa. But the word “planning” is not entirely suitable to reflect the nuances of gihoek. The producers even had a vernacular name, jejakja, which denotes “executive producer.” I will adhere to “enterprise” as a way to respect how the constantly morphing business was addressed both officially and colloquially prior to the new millennium.

Of the major players in the music industry throughout the 1990s, I will focus on three artists and their companies that are arguably the precursors of present-day K-pop: Hyun Jin-young and Wawa, Kim Gun Mo, and Seo Taiji and Boys, who were managed by SM Enterprise (SM Gihoek), Line Enterprise (Line Gihoek), and Yoyo Enterprise (Yoyo Gihoek), respectively. After providing a general overview of these artists and companies, I will tease out distinctive characteristics of each company while paying particular attention to how prevalent metaphors used to describe today’s K-pop industry, such as “machine,” “factory,” and “manufacturing,” originated in the 1990s.

Thus, the focus of this chapter is on what kinds of business strategies, sounds, images, and performances actually worked (or not) in the Korean popular music industry of the 1990s, without being bogged down by the judgmental debate on the genre’s aesthetic and moral valence. The chapter provides a critical discourse on how the Korean music industry evolved before the new millennium – in conjunction with the changing sociopolitical environment – that created the conditions for the present-day K-pop to emerge as a global phenomenon.

The 1990s: Big Shifts in the Music Industry

Referencing the 1990s as the time of changes might be redundant, since all periods are marked by changes either big or small. In the Korean popular music industry, however, the period bookended by the late 1980s and the early 1990s is remembered as a time of seismic shifts. The political democratization of the June Struggle in 1987 brought about directly elected state power, which then enabled the open-door policy (gaebanghwa) and globalization (segyehwa). In popular culture and mass media, deregulation took place in various fields. In the case of popular music, three noteworthy changes took place.

First, the multinational major music corporations, the so-called Big 6 (Universal, Sony, Warner Music, BMG, EMI, and Polygram), set up Korean branches in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Following soon after were the Korean conglomerates (chaebol), who ventured into manufacturing and distribution of records (CDs, VCDs, and LDs). The record market became wide open for a fierce competition among domestic and foreign labels, old and new business players, after the amendment of the Law on Records and Videos (Eumban mit bidioe gwanhan beomnyul) in 1991.

Second, a private terrestrial television and radio network, SBS, was set up in 1990, and several other radio stations emerged around the turn of the decade. Moreover, two cable television channels, Mnet and KMTV, started broadcasting by 1993. These newcomers challenged the virtual monopoly of two broadcasting corporations, the state-controlled KBS and the quasi-public MBC. As a result, music-related media became much more competitive during the 1990s, dubbed as the time of the multichannel and/or multimedia.

Third, the strict and notorious pre-censorship in the name of review by the Public Performance Ethics Committee (Gongyeonyulliwiwonhoe) was gradually losing its regulatory power and abolished in 1996. Although censorship by the Broadcasting Ethics Committee (Bangsongyulliwiwonhoe) continued, bans on record production and distribution were all lifted in 1996. Even moral regulations, such as the banning of the so-called undesirable artists on terrestrial television programs, were gradually disappearing throughout the 1990s.

It is reasonable to claim that foundational changes took place in three different instances in the circuits of culture: production, mediation, and regulation. Contrary to the assumption that they all collaborated in “neoliberal deregulation” in the global context, the political and cultural contexts in Korea differed from those in the so-called developed countries. While the deregulation policies often coincided with the processes of dismantling the public welfare regime in the developed countries, in the case of Korea, the deregulation policies were rather taken for granted and expected to reform the pervasive state-led authoritarian system.

However, a system based on the big shift toward deregulation can hardly be called a “free and fair market.” Regarding the distinctive characteristics of the music industry in the 1990s, complicated power relations between the principal actors in the music industry need to be investigated more in detail.

Most of all, the broadcasting corporations, especially terrestrial television, still had strong power vis-à-vis record and production companies. Music-related companies were much smaller in terms of size, scale, and negotiating power. The rankings of top-of-the-chart programs on TV had been determined by a combination of fan voting (“electoral college”) and expert voting (“selection committee”). That is why Lee Keewoong (Yi Gi-ung) argued that “hit charts were apparently based on public votes or requests; music awards were given to singers who were considered most popular that year.”4 Lee Jung-yup (Yi Jeong-yeop) also described popular music in the 1980s–1990s as “a television event.”5 It is no secret that the selection committee composed of “experts” had the largest share of power.

I would like to call this the “television regime” – a term coined by Hiromu Nagahara in reference to the Japanese media regime in which “a single medium could rightfully boast of a truly national audience” for several decades in the mid- to late twentieth century.6 Nagahara’s term applies well to the Korean circumstances, except that the regime existed for a relatively shorter period because color television broadcasting had a late start in 1980. It was taken for granted that the record sales as well as the popularity of the singers heavily relied on their television appearances on not only music programs but also other entertainment programs. Considering that the television regime has already been replaced by a different regime (I will tentatively call it the “digital-mobile platforms regime”), the 1990s was the last period in which the nationwide mass media such as terrestrial television exerted its omnipotence.

On a practical level, the negotiating power of the managers depended on their formal and informal connections with the television industry, especially the entertainment producers (yeneung PD) of music programs. The prevalence of the television regime brought a considerable shift inside the music business. Managers for singers and musicians until the early 1980s basically focused on booking their talents. Most of them were self-employed small businesspeople who functioned as simple intermediaries among record companies and wholesalers, television and radio stations, and commercial live venues. After the mid-1980s, however, they became staff members of specialized companies that managed everything related to stars and their relationship with fans. In the late 1990s, neither multinationals nor domestic conglomerates turned out to be the winners. The true winners of the music industry were the managers working in the name of executive producers.

From the Power of Distribution to the Power of Management

The 1990s were the last decade to witness the power of the television regime as well as the physical sales of recorded music. The sales of records significantly contributed to the income of artists and their managers. Million-selling records appeared during the 1990s for the first time in the history of the Korean music industry, but the economic importance of record production and distribution during the period was much higher than in the following decades. This is related to another shifting power dynamic in the music industry: the relationship between record companies (and distributors) and artists (and managers). The companies that could manage several stars could have greater negotiating power vis-à-vis record companies, big or small, domestic or international. In the late 1980s, the exclusive contracts between record companies and artists became ineffective. Record companies did not choose artists and managers anymore; the reverse happened, with managers as intermediaries. At the end of the 1990s, the record companies had become nothing more than record distributors or manufacturing plants based on outsourcing and subcontracting.

Accompanying this shift in the music industry was a regulatory change: the virtual expiration of the aforementioned Law on Records and Videos, which required record companies to be the official owners of the production facilities, especially the recording studios and record-pressing plants. Starting in 1991, some cultural activists staged protests against the legal straitjacket, and as a result, on May 1993, Article 3 of the law was declared in violation of the Constitution. The record producers did not need to “own” the facilities any longer. The legal transition explains why numerous companies were officially “registered” as record companies in the 1990s. Most had been called independent record producers – “PD makers” in the industry jargon – since the mid-1980s, but some already had negotiating power vis-à-vis record distributors and wholesalers. A significant number of the record producers employed managers, the so-called road managers, as hired staff for the artists with whom they signed contracts.

Thus, Korean music enterprises filled the dual role of record production and artist management. These entities have been called talent agencies in the music industry in the developed world; their counterparts in Korea differ because they retain the publishing rights to the recorded music. One of the important tasks of the enterprises was (and is) organizing fan clubs and monetizing their activities.

Thus, it is understandable that companies’ names transformed from “productions” to “enterprises” (gihoek). During the 1980s time of transition, the two were used interchangeably. For instance, the company that managed Cho Yong Pil (Jo Yong-pil), the 1980s male superstar, was Haeseon Enterprise (sometimes dubbed Pil Enterprise), while Na Mi, one of the iconic female singers of the same period, was managed by Samho Production.7 Despite the interchangeability between “Ent.” and “Pro,” an abbreviation for “Production,” during the 1980s, the two companies differed in one regard: while the star hired the producer-cum-manager in the former, the manager hired the star in the latter.

To sum up, the Korean music industry in the 1990s was reorganized around artist management or “star management.”8 Small companies consisting of five or six employees became the pioneers of the present-day K-pop companies. These companies were not only passive intermediaries between the artists and media but also active “makers” of stars who recruited and trained them from obscurity. Not only singing stars but also acting stars were under their management – a business model captured in the vernacular expression of “total entertainment companies.”

However, there has been virtually no significant shift in the dominant music genres of Korean pop since the 1990s. What John Lie awkwardly called “postdisco, post–Michael Jackson dance pop,” locally and nationally branded as “the new generation dance pop” or “generation X dance pop,” are the umbrella terms for the genre. Yet the changes in dominant music genres are not explained solely by the changes in the business model. The interactions between artistic creativity and the commercial business need to be examined in detail without reducing one to the other.

To explain the creation of dance pop, it is necessary to address the co-option of subculture by the mainstream culture. Throughout the 1980s, dancers and DJs at nightclubs across Seoul and other major cities emulated dance music from North America, Europe, and Japan, and constructed their own authentic genre by emulating African American dance music, notably new jack swing or rap dance, popular in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. The genre colloquially called “black dance music” was built on funky and syncopated beats and rhythm and was valued more highly than “Eurodance music” built on steadfast four-to-the-floor beats.

Among different areas in Seoul, Itaewon was definitely the most important place where DJs and dancers from all over the city gathered. The east edge of Yongsan Garrison and the physical center of metropolitan Seoul have demarcated the boundaries of Itaewon since the 1980s. One crummy dance club called Moon Night where dance battles were regularly performed has already become the legendary subject of a 2011 documentary drama series produced by cable channel Mnet – the most powerful broadcaster of Korean popular music.

Itaewon Class, the title of a 2020 Netflix drama, can be creatively applied to this subculture, although the drama is neither about music nor about the 1980s. “Itaewon class” denoted a high class in the subcultural scene of dancers and DJs but looked hopeless and futureless to the mainstream society. Ironically, the regulation of “decadent” nightclubs and discotheques starting in 1990 in the name of “the war on crime” and “the crackdown on overnight business” elevated this underground subculture into mainstream entertainment. The next destination for those who wanted to make a breakthrough in entertainment was definitely Yeouido, where TV broadcasters were clustered. The transformation of the subculture began in the late 1980s when dancers started their professional careers as backup dancers for the established singers in television programs. Choe Jin-yeol, the former manager of Hyun and, later, Seo, noted, “Starting in the late 1980s, quite a few ‘Itaewon families’ moved on to the Yeouido scene either as singers, dancing teams, or choreographers in the broadcasting stations.”9 He even used the term “Yeouido pop scene” (Yeouido gayogye)”10 and “Yeouido manager scene” (Yeouido maenijeo segye)”11 to refer to these clusters of music industry workers.

Some DJs also appeared on those programs and performed live remixing, which was very unusual at that time. Some famous DJs dreamed of becoming record producers who created dance-oriented pop music, distinct from mixed and remixed sound played at nightclubs and also suitable for performance on television programs. Simply put, their ambition was to replace melody-centered pop ballads with rhythm-centered dance pop. As will be explored later in this chapter, the dichotomy is not clear-cut due to the genre diversification strategy consciously designed by the industry. Yet it is obvious that constructing, packaging, and branding dance pop as a new trend became effective by linking the genre with the (sub)cultural codes of the new generation (sinsedae) born in the 1970s.

SM Enterprise: The Rise of the “New Dance”

Hyun Jin-young and Wawa (sometimes spelled Wawaoowa!) was the pioneer of 1990s dance pop (see Figure 2.1). Son of a jazz pianist, Hyun grew up in the Itaewon area and began to make money by dancing in nightclubs in his teens. It is said that a rival was Lee Juno (Yi Juno), who would become one of the “boys” in Seo Taiji and Boys. His troubled and hopeless life as a nameless underground dancer ended when he was singled out by Lee Soo-man (Yi Su-man), who was not in the subculture but was interested in selling it to the wider public.

Figure 2.1 Record covers of three full-length albums by Hyun Jin-young produced by SM Enterprise in 1990, 1992, and 1993. Wawa disappeared from the second one.

That is exactly the moment when Lee Soo-man officially founded SM Enterprise and built a house studio on the eastern fringe of the Gangnam area. Though a tiny company with three or four staff members, SM Enterprise showed the basic characteristics of the divisions within an entertainment company. Choe Jin-yeol, who had experience in the nightclub business throughout the 1980s, was schedule manager; Heo Jeong-hoe (aka DJ Kat), who worked as a DJ playing African American dance music at nightclubs in Itaewon, was recruited as house engineer; and Hong Jong-hwa, a talented musician and computer-savvy producer, worked as an exclusive songwriter even before the company was launched. The in-house production12 and management that still characterize the gigantic K-pop companies were already nascent in the late 1980s, prior to Hyun’s debut.

The format of Hyun Jin-young and Wawa was definitely similar to Bobby Brown backed by two dancers or Guy fronted by Teddy Riley. Brown and Riley were household names to those who were familiar with African American dance pop in the late 1980s, but they were not so well known to Korean pop fans, who were into balladeers and, to a lesser degree, rock bands.13

Wawa was not an anonymous dance duo backing the star singer but an organic part of the group that formed the dance pop trio. Even to those familiar with Korean pop in the 1990s, it was not well known that the first formation of Wawa evolved into Clon and its second formation into Deux, after they quit Wawa and signed with different management companies, respectively.

Hyun Jin-young and Wawa released their first full album in August 1990, the second in October 1992, and the third in September 1993. The song “You in the Faint Memory” (Heurin gieoksogui geudae) in particular was a smash hit around the time of the fourteenth presidential election in December 1992, when a civilian politician, Kim Young-sam (Gim Yeong-sam), took power, replacing the thirty-year military dictatorship. The song topped the chart at the weekly Gayo Top 10 during December. It would not be an exaggeration to claim that the cultural transition epitomized by branding the music genre as “new dance” was symbolically associated with the political transition. Though not the focus of this chapter, it was also connected to the broader “new generation culture” (sinsedae munhwa) and its affluent and hedonistic protagonists called orange tribe (orenji-jok) or Apgujeong clan (Apgujeong-pa).

Yet Hyun could not continue to enjoy his success due to drug scandals. Even during his heyday, he was arrested at least twice due to the illegal use of drugs. The last arrest trailed the release of the third album and was regarded a serious offense due to his consumption of hard drugs. His sudden fall from grace badly affected SM’s business, which was able to recover only after launching a male idol group, H.O.T., in 1996. A quintet boy group, H.O.T. flaunted a much more sanitized public image and was modeled on Japanese boy groups such as SMAP rather than American rap dance groups. The switch in the aesthetic and cultural codes of SM Enterprise became more visible when it signed a licensing deal with Avex Trax in 2000, which promoted S.E.S. and BoA for the Japanese market. These moves signaled the beginning of K-pop as we know it today. SM’s pioneering moves included the change of its official name to SM Entertainment in 1995, just before the launching of H.O.T.

Returning to the second album of Hyun Jin-young and Wawa, two cover versions of Korean rock classics written by legendary figures Shin Joong-hyun (Sin Jung-hyeon) and Lee Jang-hee (Yi Jang-hi) were included. Lee had a career as a solo singer and vocalist in rock bands, and the inclusion of the rock songs in Hyun’s album showcases the versatility of the budding K-pop genre. To this point, another song was cowritten by Kim Chang-hwan (Gim Chang-hwan) and Sin Jae-hong, who were the driving engine of Line Enterprise, the main subject of the next section, and had connections to both the dance music community and the rock music community in the 1980s.

SM’s post–Hyun Jin-young and Wawa products were Major, a band branded as “easy rock,” and a duo, J&J, branded as “guitar and dance.” R&B singer-songwriter Yoo Young-Jin (Yu Yeong-jin), who would become a prolific house songwriter for SM Enterprise, also released records in the mid-1990s. Unfortunately, these SM Enterprise artists who debuted during the mid-1990s did not command much public attention. Contrary to the impression that SM has always been a successful industry leader, the company’s trajectory spanning nearly thirty years was marked by trial and error as well as a series of crises. In this regard, the rhetoric of “success,” which has frequently and uncritically been used in the K-pop discourse, needs to be carefully rectified.

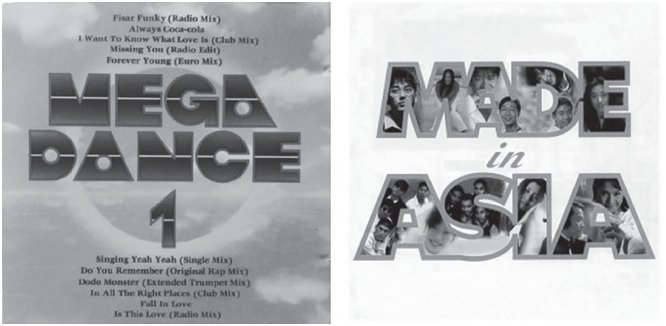

SM retained old-type business practices of recording and distribution in the 1990s. Although the company presided over the entire process of recording, for manufacturing and distribution of the records, it relied on Seorabeol Records, one of the mainstays in the industry since the 1970s. In this sense, SM Enterprise before the launching of H.O.T. was definitely different from SM Entertainment as well as other K-pop companies after the millennium. It is no coincidence that “new dance” included layers of preceding pop genres such as folk, soul, and rock that had been highly indigenized during the 1970s–1980s (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 The first “best albums” compiled by SM: Vol. 1 (left, 1994) and Vol. 2 (right, 2001). In Vol. 1, many songs are folk-tinged ballads performed by the artists who signed contracts with SM preceding Hyun Jin-young and Wawa’s debut. Vol. 2 consists of recordings by SM idols such as H.O.T., S.E.S., Shinhwa, and BoA.

To sum up, SM in the early days developed a profitable model by selling a subculture to a wider mainstream audience. It was proved that the model would not be feasible without domesticating edgy subcultural elements. The future of then-emergent dance pop had to rely on recruiting boys and girls from nightclubs or from the street dance scene, but the recruits had to be disciplined by the company – an important hallmark of K-pop industry training.

In 2004, Lee Soo-man noted that “if Japan has forged J-pop by digesting [Anglo-]American rock, Korea has forged K-pop by digesting black [African American] music.”14 Although the SM music produced after Hyun hardly sounds “black,” there are SM artists and producers who claim they pursued “black music.” What did “black music” sound like when created and performed by Korean artists?

Line Enterprise: The Rise and Fall of the Empire of Genres

As of 2021, BTS has broken all music sales records by Korean artists. But before the age of BTS, there were two veteran artists who sold more than 10 million records: Shin Seung-hun (Sin Seung-hun) and Kim Gunmo (Gim Geon-mo). Kim’s third regular album (1994) and Shin’s fifth regular album (1996) in particular are estimated to have sold more than two million copies each.

These two chart-topping and multimillion-selling artists belonged to the same company, Line Enterprise, directed by Kim Chang-hwan, nicknamed KC Harmony (hereafter KCH). Having worked as a discotheque DJ in Seocho in the Greater Gangnam area throughout the 1980s, he transformed himself into a record producer of Shin, who was looking for the right person in the industry. Shin was followed by Kim, who was discovered by KCH during a visit to a live music venue where Kim was singing and playing the keyboard. All three of them were born in the 1960s.

The genre and style of the two singers are (mis)labeled as pop ballad and dance pop, respectively. If we were to consider their megahit songs only, the labels would not be entirely wrong. But closer scrutiny reveals that their albums mixed pop ballad and dance pop in different proportions. While Shin recorded and performed some upbeat and danceable songs, Kim recorded and crooned some mid-tempo sentimental ballads. This is how Shin could differentiate himself from formulaic balladeers, and Kim from tawdry dance singers. Another strategy to diversify the two was to brand Kim’s music as “black music” (heugin eumak) and Shin’s music as generic pop. The two superstars were conventional to a certain extent, but definitely eclectic and versatile in ways that distinguished them from the rest (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Multimillion-selling records in the 1990s. The back cover of Kim’s third album (left, 1994) and the front cover of Shin’s fifth album (right, 1996). Kim’s face color and fashion style are dark and playful, whereas Shin’s appear light and dandy. Quite problematically, no criticism was directed at Kim’s album image reminiscent of minstrel shows, although it appears that the artist and producers were unaware of potentially projecting a pejorative image of a black entertainer.

From the perspective of Line Enterprise, it was a part of the risk management strategy to diversify its portfolio. Line was by no means the only company that pursued this strategy, but its implementation was so unique and effective because KCH deployed what urbanist Ryan Centner called “spatial capital,” or the “power to take place.”15 KCH and his colleagues represented the 1990s “Gangnam style”: KCH hung out around Bangbae Café alley, worked as a DJ in the Seocho discotheque scene, and became a professional musician in his company located in Dogok, all of which are neighborhoods in the Gangnam area. He was not only a producer but also a songwriter who provided artists, including Kim, with quite a few songs that ended up becoming hits. Only Shin, a talented singer-songwriter, was not assisted by KCH’s songwriting talent.

KCH created the pool of songwriters by mobilizing young and aspiring musicians, such as Sin Jae-hong, Bak Gwang-hyeon, and Kim Hyeong-seok, all of whom majored in music at prestigious universities in Seoul. What started as a personal network based on neighborhoods and schools transformed into a powerful force in the industry in a few years. It is well known that Gim Hyeong-seok taught songwriting and producing to Park Jin-young (Bak Jin-yeong), who would become JYP, one of the key impresarios of the K-pop industry today.

KCH’s company started as Moa Enterprise, which was part of Dukyun Records, one of the latecomers to the industry in the mid-1980s. After breaking off from Dukyun in 1994, Moa Enterprise founded Line Sound as a record distribution company and Line Enterprise as a production company. Thus Line was a rare case that combined distribution and production under the same roof. Located in Dogok, a relatively quiet neighborhood in Gangnam, Line Enterprise featured a production system that was closer to the in-house production by K-pop companies in the new millennium than any other companies of its day.

Another act produced by Line Enterprise was Noise, a dance pop group led by talented artist Cheon Seong-il. As seen on the cover of their album, they were ambitious, perhaps too much so, to the extent that various genres – techno, rave, hip hop, and house – were mixed on one album. Moreover, each track proudly claimed the hybridity of the genres: rave dance, reggae house, European hip hop, slow dance, techno rave, disco house, new wave rock, funk bossa nova, and others (see Figure 2.4).

The proliferation of genres continued on other records produced by Line Enterprise. This included the platinum-selling record by Kim, featuring R&B ballad, reggae dance, jazz funky (sic), reggae ballad, hip hop, disco house, Latin funky (sic), a cappella, and twenty-four-beat funky (sic). This was not unusual for 1990s mainstream Korean pop, but Line was definitely the pioneer of condensing various genres into one record album. The custom of “one genre for one song” persists after all those years, as can be gleaned from the liner notes of the recent BTS albums. I was among those music critics who at the time thought that it did not make sense at all and that the albums were far from authentic genre music. However, the “empire of genres” would be conceptualized as an extension of compressed globalization and digitalization: the wild, uncontrollable, and disjunctive global flows pushed by digital technology.

The subject of digitalization of popular music, particularly of 1990s Korean pop, is too wide of a topic to be discussed here. It could be summarized that the digital production of music was already due to appear way before the advent of digital distribution and consumption of music. Digital recording equipment (recorder and mixer) and digital musical instruments (synthesizer, sequencer, and sampler) began to be used heavily in the early 1990s by some early adopters in the industry.

Line Enterprise used the digital technology in an eclectic way by combining digital/“virtual” instruments with analog/“real” instruments, which explains the wide accessibility of the musical sounds produced. However, the innovative aspect of the sound lay in its heavy usage of digital beats and rhythms, which can be compared to Eurobeat in Japan – the invention of the famous producer Komuro Tetsuya and Avex divas such as Amuro Namie and Hamasaki Ayumi (see Figure 2.5). I will not go into detail on this delicate issue, but it is interesting that the highlight of Komuro’s career in Japan evolved simultaneously with that of KCH in Korea.

Thus, the signature sound of Line Enterprise was represented by what the company called “disco house,” which was epitomized by the megahit song “The Wrong Encounters” (Jalmotdoen mannam) by Kim Gunmo and other hits by a soulful dance diva, Bak Mi-gyeong, and a hip-hop–tinged dance pop duo, Clon. The soundscape of Line Enterprise’s hit songs was based on heavy, machinic, and insistent kick drumbeats: Eurobeat or Eurodance or Eurodisco or Eurohouse. This eloquently shows that the spatial and temporal trajectories of K-pop cannot be simply and easily explained by “American influence” or “global flows.” They were and remain much more complicated (see Figure 2.6).

Other influences and flows were discovered when Clon debuted in Taiwan in 1997. One of the intermediaries behind the process was Wang Bae-young, an ethnic Chinese businessman based in Korea. Before becoming the CEO of the Korean subsidiary of Valentine Music based in Singapore – an act followed by serving as the CEO of the Korean subsidiary of Taiwan-based Rock Records – he contributed to the club dance music scene in East Asia by importing and licensing records for DJs, including KCH. In the 1990s, he was skillful at releasing club dance music compilation discs and tried to make connections across East Asia. Clon was just one of the cases of then-emerging inter-Asia business connections, which exploded after the 2000s.

The Line empire did not last long because the CEO of Line Sound was charged with tax evasion and embezzlement in 1998, just a year after the financial crisis erupted in late 1997. After the crisis, Line Enterprise could not make a comeback in its own name, although KCH continued with a not-so-successful career as a producer and songwriter. But even before the financial crisis of 1997, there was a sign of crisis when Kim left the company in 1995. Line Enterprise was not big and solid enough to manage the million-selling superstar. The following section illustrates how “becoming a superstar overnight” was not so unusual in the 1990s, which eventually paved the way for the global explosion of K-pop in the new millennium.

Yoyo Enterprise: Of the President, by the President, and for the President

Very few will challenge that the most explosive artists to have emerged in the 1990s Korean pop scene were Seo Taiji and Boys. A dance pop trio, they debuted in April 1992 with the release of their eponymous album, which brought them an instant colossal success. They disbanded in January 199616 when they announced their retirement just two months after releasing their fourth full-length album. Throughout their career, which lasted three years and eight months, they stirred hysteria among fans, often referenced as “Taijimania,” which is still used as a nickname for their fan club. It is safe to say that they radically transformed the existing modes of operation in the music industry in that short span of time.

The trio was formed on the ground of the aforementioned Itaewon-based subculture. However, Seo Taiji himself was not a core member of the subculture of dancers and DJs, but a bass player in the rock band Sinawi (aka Sinawe). His association with rock music was more visible than Hyun Jin-young’s. Even on the debut album of Seo Taiji and Boys, his old bandmates Shin Daechul (Sin Dae-cheol) and Kim Jong-seo (Gim Jong-seo) were featured on guitar and as a guest vocalist, respectively, in recording sessions for some tracks. He also invited a rock guitarist and bassist to the studio when he self-produced the second album, Seotaiji and Boys II (1993), and third album, Seotaiji and Boys III (1994) (see Figure 2.7).

Although the roots of rock were reprised more clearly in some recordings on the later albums, the trio rarely performed live backed even by a session band, let alone a nominal band. The recorded music came from North American rap (later transformed into hip hop) and European techno pop. In short, the blending of rock, rap, and techno in different proportions was their musical formula.

According to the record credits, the first album was produced by Yoo Dae-young (Yu Dae-yeong), who was then working as a mixing DJ in the broadcasting and record industries and was credited as “Scratch” on the first album by Hyun Jin-young and Wawa. However, he was fired by Seo Taiji just after two songs, “I Know” (Nan Arayo) and “You in the Fantasy” (Hwansang sogui geudae), became phenomenal megahits. He was replaced by Choe Jin-yeol, who formed Yoyo Enterprise after quitting his job at SM.

The least important actor in the process of making the Seo Taiji and Boys phenomenon was the record company Bando Records (Bandoeumban), signaling the shifting power dynamics between the recording companies and the enterprise companies involved in music production. Its role was limited to providing a “label” in the literal sense when the Law on Records and Videos was gradually phasing out to become only a nominal practice. Bando Records was one of the latecomers in the industry, officially registered as late as 1985, and did not have impressive hit records. This virtually unknown record company was consciously chosen by the artist as a way to minimize interference in his creativity. This was a harbinger of the shifting power relations between record companies and enterprise companies in the days to come.

What made this shift plausible was the digitalization of the recording process. Seo heavily used “synthesizer” and “computer programming” on the first album. Starting with the second album, he produced the whole sound in his home studio. The unrivaled position Seo occupied in Korean pop history was enabled by this shifting trend in music making toward widely employing digital technology. Pop music based on a rock idiom while also being heavily infused with rap and techno would not have been made before the 1990s. This new type of music suited well the format of television music shows that preferred playing prerecorded music to real-time live performance. Even lip-synching was legitimized in the chart programs, where different artists had to quickly rotate after performing one song.

There had been questions about the originality and authenticity of the recording and performances of Seo’s group. Some even accused him of plagiarism (“unoriginality”) and lip-syncing (“inauthenticity”). Rather than directly confronting the sensitive issue of originality and authenticity, I believe it is more productive to focus on Seo Taiji’s music-making process. Seo Taiji’s music was neither rock and heavy metal nor rap and hip hop. On the one hand, the recorded sound was different from conventional rock music because it was heavily based on computer programming and was difficult to perform live. On the other hand, the music style was not close to rap or hip hop, even though he frequently employed rapping skills, to the extent of creating a strange vernacular “rap song.” It would not be an exaggeration to say that Seo Taiji and Boys’ music is a savage anomaly constituting a genre unto itself.

After the disbanding of the group and the automatic relinquishing of Yoyo, two dancer “boys” started their respective businesses by launching their own enterprises: ING enterprise by Juno Lee, and Hyun Enterprise by Yang Hyun Suk (Yang Hyeon-seok). Neither of them minded the convention of television entertainment and enjoyed commercial success in the mid- to late 1990s. It is well known that Yang Hyun Suk transformed from a dancer into a record producer, eventually becoming one of the major impresarios of K-pop. His brainchild, YG Entertainment, positioned itself as a “hip hop label” and became a powerhouse of genre music.

Meanwhile, Seo made a comeback in 2000 by reinventing himself as a solo rock artist. Genius of both music making and music marketing, he ended up founding Seotaiji Company in 2001. It is not the only company that manages a single artist; superstars like Cho Yong-pil and Lee Seung-hwan (Yi Seung-hwan) also had their own companies exclusively in charge of their own careers. Yet Seotaiji Company is the most secretive in its business activities. It also failed to cross borders into other genres of music.

Thus is the history of the Korean popular music scene leading up to today’s K-pop world. Yoyo Enterprise was a dream destination for artists who were artistically focused and commercially viable, but it did not provide any model for the next generation of artists and companies to emulate. In other words, the company, dominated by one person, became neither culturally subversive nor financially competitive. Seo neither restored his connections to the declining but still existent rock scene nor joined the wildly exploding hip-hop scene. To be fair, assuming leadership in the music scene was not part of Seo’s agenda. He is often referred to as the “cultural president” (munhwa daetongryeong), but his presidential term was not renewed and lasted for only four years (1993–1997).

The last point about the case of Seo Taiji and Boys is that they had no substantial connections to the overseas music industry except the record release and concert tour in Japan. Yet the music and public image of the group mix American rap dance, European techno pop, and Japanese metal (often referred to as “visual rock”). Despite Seo’s creativity in mixing heterogeneous sources, references from Milli Vanilli, a French-German R&B duo, and X-Japan, a Japanese rock band, are felt here and there in the group’s soundscape and fashion choices. Here again, the “American influences” are not the only ones that matter, and multiple border-crossing cultural flows were already working in the early phase of globalization.

Many parallel circumstances existed between Korea and Taiwan. In the same year that Seo Taiji and Boys made their debut, another boy group, LA Boyz, emerged in Taiwan. Despite no direct connection, both groups were labeled the first rap group in their respective countries. But the latter was different from the former because the members were Taiwanese American returnees from Los Angeles. These overseas Taiwanese had close connections to Korean American returnees who debuted as Solid in 1993.

Solid was one of the rare boy groups that were highly regarded as creative artists, as the leader, Jae Chong (Jeong Jae-yun), wrote all the songs and produced all their records. The group was managed by Seoin Enterprise, another company set up by a former employee of Line Production, and signed a contract with Kim Gun Mo, who left Line in 1995. Too many complicated criss-crossings there may be, but that is characteristic of the pop entertainment industry in South Korea and East Asia at large.

Conclusion: The Road toward the K-Pop Companies

I hop across three places in Seoul that appear in the title of this chapter – Itaewon, Gangnam, and Yeouido – that have already proven their significance in the history that preceded today’s K-pop world. Yeouido was the place to work for the promotion of stars, and Gangnam was the place for producing stars and music making. Itaewon, where youngsters hung out, was the place for the nightclub industry. Despite the variations among them, they all stand as pillars of the Seoul-based music industry.

The changes that took place after the 2000s are beyond the scope of this chapter, but I have no hesitation in calling the emergence of 1990s dance pop a revolution. However, there has been virtually no research on the industrial side of this revolution. While there are quite a few studies highlighting the cultural perspectives, this chapter has focused on the processes of music making that were symbiotically linked to the morphing relationship among creative artists, production-cum-management companies, and recording companies (or labels). Without any qualifications, the transformation of the discursive subculture based in nightclubs into a lucrative business associated with the music industry was revolutionary.

I assume that such a revolution would not have been possible in the countries in North America, Western Europe, or Japan. To my knowledge, in those regions with a highly consolidated music industry, breakthroughs by little-known pop singers or groups was (and still is) almost impossible without promotion and distribution by major labels. In South Korea in the 1990s, the enterprises operated on the principle of “high risk and high return.” That is one reason some companies that dominated the market in the 1990s virtually disappeared in the midst of further digital disruption in the early to mid-2000s.

The enterprises had to further readjust themselves during and after the economic crisis of 1997–1998. Many changed their name once again to “entertainment companies.” This reflected the increasing business volume, size of company facilities, and scope of their business activities. The winners in the music industry eventually went public on the stock market. As expected, they are what we call K-pop companies today and clearly take the form of multidivisional corporations that have established a distinct system of in-house production. As we know, the winners take it all and the losers have to fall.

However, even the big winners of K-pop are dubbed “indie”17 in the global music industry, as evidenced by Billboard, which chose Bang Si-hyuk and Jimmy Jeong as two “2020 indie power players.” If “indie” is simply defined as not part of the multinational majors, or the so-called Big 3 (Universal, Warner Music, Sony), then it makes sense at a global level. Yet, at least to South Koreans, it is hard to agree with the labeling, as the K-pop companies have never taken anticorporate stances and K-pop has got rid of “local” characteristics since the millennium. International illusion persists, and that is the “globe” we now live in.

If K-pop is the machine, there has been a ghost in the machine. The ghost was born in the early 1990s, and its protocol was formulated in the late 2000s and has kept evolving. That is the subject of other chapters in this volume.