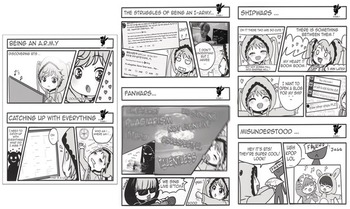

Within a webcomic published in early 2018 (Figure 13.1), a passionate fan of Korean boy band BTS who identifies online as Myra (@MyraKM9597) charts the process by which she came to identify as a member of ARMY, the BTS fandom group. Beginning with her enraptured discovery of BTS, continuing with her learning to be part of ARMY through engaging with the band’s social media, and ending with a rebuffed attempt to convert her friend into a supporter of the global superstars, Myra’s webcomic depicts a narrative that would be easily recognizable to most K-pop fans.1 From exploring the struggles of international fans who lack Korean-language proficiency to strong feelings of wonderment and attraction to the handsome and talented members of BTS, Myra’s webcomic also dramatizes the pleasures and pains central to the fandom culture that has emerged around K-pop idols both within and without South Korea. But one section is particularly interesting. In the fifth portion, entitled “Shipwars,” Myra explores an aspect of K-pop fandom called “shipping” that may seem somewhat confusing to outside observers but is integral to the celebration and consumption of K-pop idol culture. In this artistic retelling of her journey, Myra explores how her strong attraction toward how two of the boy band’s members interact produced an immense affective response that led her to begin “a blog for her ship.” Via the narrative she creates within this comic, Myra argues that the phenomenon termed “shipping” is integral not only to becoming part of ARMY but also to becoming a K-pop fan.

Known variously as “coupling” in South Korea (keoppeuling) and Japan (kappuringu) and “slash,” “real person shipping,” or simply “shipping” in Anglophone contexts, the practice to which Myra alludes is the fannish celebration of the relationship – the word from which the term “shipping” derives – between two members of a K-pop idol group. More than just referring to the celebration of idols’ real-world friendships, however, the terms “coupling” and “shipping” are more commonly utilized by K-pop fans to refer to the practice of imagining the members of their favorite bands in romantic or sexual relationships.2 As idol shippers, fans like Myra create visual art such as comics or illustrations and write fan fiction in which they explore the erotic potentials of imaginary same-sex idol relationships.3 Indeed, shipping practices that reimagine the members of popular K-pop boy groups such as H.O.T., TVXQ, and BTS within romantic or homoerotic relationships are especially common among both heterosexual female fans and fans from queer communities.4 As Myra’s webcomic suggests, shipping is a common practice within K-pop fandom culture. Ultimately, it is a social practice whereby fans deploy homoerotic imaginaries, or what theorist Jungmin Kwon terms “gay FANtasy,”5 not only to explore their sexual desires for the attractive idols but also to express the intensely affective experience of fandom itself.

In this chapter, I explore the homoerotic practice of shipping idols as a lens into the broader study of gender and sexuality in relation to K-pop, demonstrating the importance of fans’ sexual desires to fandom culture. I draw on ethnographic research into K-pop fandom in Australia, Japan, and the Philippines that I conducted between 2015 and 2020 to theorize the role queer sexuality plays within fandom culture. These three countries represent under-researched contexts for the reception of transnational K-pop, and my hypothesis was that the significant cultural differences among them would strongly influence shipping, allowing for interesting contrastive analysis. I pay especially careful attention to how societal norms influence both fans’ shipping practices and their understandings of shipping itself. In focusing on queer sexuality, I go beyond a simple exploration of sexual orientation and deploy queer as a radical hermeneutic focused on “whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant” to account for sexual desires and practices that foundationally challenge the societal status quo.6 Although the desires and beliefs of fans from queer communities form an important part of the analysis, my main focus in this chapter is to explicate how the sexual desires evoked through shipping challenge and subvert both patriarchy and heteronormativity within the myriad cultural contexts in which K-pop fans are embedded around the globe.

I begin by charting the emergence of shipping practices within South Korean fandom, exploring how K-pop production companies strategically encourage young women to consume K-pop through shipping, thus producing spaces within the patriarchal society where women’s sexual desires can be safely explored. The chapter then turns to an analysis of international shipping practices, presenting a comparative case study of BTS shipping within Japanese and Anglophone (Australian and the Philippines) fandom spaces. While BTS shipping in Japan tends to draw on rigid logics that conceptualize homoerotic relationships between men via sexual practices and behaviors divorced from identity, Anglophone shipping tends to instead overtly deploy LGBTQ identity politics to make sense of fantasy relationships between band members. Nevertheless, I argue that both practices possess queer potentials that allow fans to affectively explore their sexuality, affirming their sexual desires for K-pop idols. This process, I suggest, is particularly important for fans from queer communities seeking visibility within the global K-pop fan community.

The Emergence of Idol Shipping in South Korea: A Queer Feminist Practice

The practice of imagining idols within homoerotic pairings developed together with the broader emergence of K-pop and idol culture in the early 1990s as South Korea’s entertainment industries underwent reforms tied to the democratization of society and the concomitant liberalization of the Korean popular culture landscape.7 That is to say, from the very genesis of K-pop, shipping was central to the development of fandom culture. Kwon identifies the emergence of idol shipping in the 1990s as part of a broader social phenomenon where young heterosexual female consumers became increasingly interested in “gay FANtasy,” a term Kwon coined to denote “female fans’ interest in and desire for gay male erotic relationships” and “the subjectivity and cultural power of these enthusiastic media consumers.”8 Other examples of this influential culture include South Korean young women’s investment in Japanese Boys Love manga comics – a genre I discuss further in the following section which is also sometimes called yaoi – and gay-themed American sitcoms such as Will and Grace.9 As these further examples make clear, South Korean young women’s interest in male homoeroticism emerged in the 1990s partly as a result of the gradual removal of the nationalist protectionism that had typified the postwar South Korean media landscape until the late 1980s.

The historical emergence of idol shipping thus owes much to the ideology of globalization known as segyehwa and resultant policies aimed at structurally reforming the Korean economy implemented by the administration of President Kim Young-sam (Gim Yeongsam). As Suk-Young Kim highlights, despite the economic failure of these structural reforms, segyehwa was ideologically instrumental in the historical development of K-pop, particularly through policies lifting the ban on the importation of Japanese cultural products.10 This opening up to Japan played a crucial role in introducing South Korean women to the pleasures inherent to shipping. Almost at the same time as entertainment companies began producing idol boy bands in the 1990s, a fandom for the homoerotic Boys Love manga of Japan exploded among young women in South Korea.11 Thus, as these young women were enthusiastically supporting and discussing the handsome idols from the so-called first generation of K-pop bands such as H.O.T., Sechs Kies, and Shinhwa on online forums, they were also enthusiastically consuming the fan-translated Boys Love manga from Japan that were available on these sites.12 Unsurprisingly, these two fandoms merged as young women began to ship handsome male idols from their favorite bands together, imagining them in romantic or sexual relationships similar to those depicted on the pages of translated homoerotic manga as a way to express both their fannish devotion and their sexual desires.13

The literacies from these Boys Love manga, which I introduce more fully below, strongly affected the ways that young female consumers learned to “read” interactions between the handsome idols central to K-pop’s emerging performance norms in the 1990s and thus educated K-pop fans about the affective and erotic potentials of male-male intimacy.14 Within the heteronormative social context of South Korea, where expressions of same-sex desire are socially censured, the importation of Japanese popular culture queered young women’s viewing habits, introducing a queer gaze that celebrated radical sexual expression and continues to challenge the conservative gender ideologies of the society. But shipping also represents a queer transformative practice in other important ways. South Korea’s patriarchal society has traditionally denied women the ability to express their sexual desires actively, instead positioning them as objects upon which the desires of heterosexual men are enacted.15 For Kwon, shipping represents a radical feminist act since its explicit facilitation of women’s exploration of their attraction to handsome male idols provides young female fans the sexual agency to express their desires within a social context where such expression is often routinely silenced.16 Thus shipping centers women’s sexual desires at the heart of K-pop fandom culture.

As businesses chiefly targeting young female consumers, K-pop production companies strategically manage the star personae of their idols. Historically, this has meant implementing dating bans and controlling media reporting through their considerable economic clout to ensure that idols remain unattached and thus potentially available as objects of romantic investment to their fans. As the K-pop industry matured, Kwon argues, shipping was co-opted into the developmental logics of South Korea’s idol culture as a safe way for female fans to consume media about their idols without compromising this theoretical availability.17 K-pop production companies now explicitly support shipping practices, such as when SM Entertainment invited fans of their megagroup TVXQ to participate in an officially sanctioned fanfic contest focused on imagining members of the band in romantic relationships (sexually explicit fictions were, however, strictly banned).18 In strategically deploying shipping in their marketing and production practices, Korea’s popular culture industries have expanded and diversified their markets by absorbing what was once an underground subculture into the mainstream.19 It has become routine for K-pop idols to perform “fan service,” often involving “skinship” and other acts of “performed intimacy” that passionate fans subsequently draw on in the production of fan fiction and fan art.20 In so doing, K-pop production companies are borrowing already well-established fan service practices from the Japanese idol industry (most notably from Johnny’s and Associates, the largest producer of boy bands in Japan).21 Further, as a result of the cultural influence of K-pop idol shipping, in recent years companies have created “bromance films” wherein handsome idol actors perform “intimate but not sexual” relationships designed to attract young female fans of gay FANtasy while not alienating more conservative audiences.22

The above historical narrative reveals that shipping is primarily practiced by female fans of male idols, the chief market in South Korea for K-pop. But emerging research by anthropologist Layoung Shin reveals that shipping also initially informed the practices of same-sex-desiring female fans active within the “fancos” (fan costuming) community. Many lesbian-identified K-pop fans would enjoy cross-dressing as their favorite male idols in the 1990s not only to celebrate their fandom but also to express their own sexual attraction to members of the same sex through the strategic embodied performance of shipping through costume play.23 Kwon’s interviews with gay Korean men show that many view gay FANtasy culture such as idol shipping positively, recognizing its potential to shift public attitudes toward homosexuality in positive directions, although none of Kwon’s gay interlocutors actively participated in such practices.24 There is a dearth in research into queer fans of K-pop within South Korea itself, but, as my research in Australia and the Philippines reveals, idol shipping has become increasingly popular among queer communities around the globe. It is thus likely that shipping is practiced by queer fans in contemporary South Korea.

Shipping BTS in Japan: The Influence of Boys Love Manga

In the early 2000s, a passionate Japanese fandom for Korean popular culture developed; anthropologist Millie Creighton identified the ratings success of Winter Sonata (Gyeoul Yeonga) in 2004 and the subsequent domination of Japan’s pop music charts by South Korean superstars BoA and TVXQ as catalysts for the Korean Wave in Japan.25 By the mid-2010s, Japanese fandom for Korean popular culture had become embedded within preexisting women’s consumer cultures, with female teenagers and women in their twenties emerging as the primary fans of K-pop idol groups.26 Discussions I had with young women fans during a trip to Tokyo in 2020 revealed that they did not see K-pop fandom as separate from their broader consumption of Japanese women’s media.27 In fact, many indicated that it was “obvious” (atarimae) that Japanese women would be attracted to Korean popular culture since it represents just one facet of what one interlocutor termed “girls’ culture” (shōjo bunka).28 My observations and conversations with fans between 2015 and 2020 revealed that K-pop fandom had entered into dialogue not only with Japan’s own established idol culture but also with the shōjo manga (girls’ comics) at the heart of Japanese girls’ culture.29

One genre of shōjo manga played an especially prominent role in influencing how young women consumed and enjoyed media about K-pop idols in Japan: the aforementioned Boys Love manga. It is via Japanese fans’ engagement with this popular culture form that they learn about and begin to practice shipping. The connection is unsurprising since K-pop developed in part due to production companies’ earlier adaptation of these very practices to the South Korean context. Indeed, in a book focused on the lasting appeal of TVXQ in Japan, cultural critic Ono Toshirō points to “K-pop idol yaoi” among female fans of the boy band as one reason for the group’s continued success in the Japanese market.30 Highlighting that Japan’s long tradition of Boys Love manga provided women the “necessary knowledge” to produce homoerotic fantasies, Ono notes that “playing with yaoi” (yaoi de asobu) represents an important “method of experiencing pleasure” through K-pop idol consumption.31 Interestingly, the Japanese character that Ono uses in his writing to refer to pleasure (愉) typically connotes sexual forms of pleasure, especially orgasm. Just as idol shipping allows women in South Korea to explore their sexual desires, Ono argues, shipping idols through the logics of Boys Love provides young Japanese women a form of sexual release often denied them within Japan’s patriarchal society.32

Emerging out of shōjo manga in the mid-1970s, Boys Love focuses on intimate relationships between beautiful male youths and possesses narrative logics born out of Japanese conceptualizations of gender and sexuality.33 One particularly important narrative trope is the so-called seme-uke rule, which stipulates that one member of a male-male couple is characterized as an uke (receiver) who is passively initiated into male-male romance by an aggressive seme (attacker) who subsequently “leads” their relationship.34 Cultural critic Nishimura Mari argues that this seme-uke relationship is typified by a power imbalance usually signaled to readers via set representational strategies known in Japanese as the “noble path” (ōdō).35 First, the seme is typically depicted as taller, older, and considerably stronger than the uke.36 Second, the seme is regularly characterized as reserved and stoic, but with a strong and uncontrollable sexual desire that is awakened by the virginal innocence of the uke.37 Third, the uke represents the partner who is penetrated during sex and is typically presented as “soft” and “effeminate” compared to the penetrating seme, usually depicted as comparatively “harder” and more “masculine.”38 This seme-uke rule was transplanted to South Korea, where K-pop idol shippers similarly position couples as containing a gong (seme) and a su (uke) member.

When examining how the members of BTS are typically shipped in Japan, it becomes apparent that this seme-uke rule also strongly influences how Japanese fans of K-pop both practice and understand idol shipping. According to a representative chapter on shipping in The BTS Fanatic’s Manual, one of fifteen BTS “mooks” (magazine books) I have gathered during trips to Japan between 2018 and 2020, all of which contain a section addressing shipping, the so-called love-love relationships between the members naturally fall into seme-uke couples.39 The “mook” lists eleven particularly popular ships, providing a brief introductory text as well as ratings for each potential couple’s “love level” and “likelihood of appearance.” The following ships are presented to the reader in order of apparent popularity among Japanese fans: Jimin x Jungkook, RM x J-Hope, Jin x V, Suga x Jungkook, Jimin x V, Suga x V, V x Jungkook, J-Hope x Jungkook, Jin x J-Hope, J-Hope x Jimin, and RM x Suga. The use of the “member x member” method of framing the ships is significant and ultimately derives from Boys Love fan practices where “seme x uke” has become the standard way of naming a male-male couple.40 Speaking about the role of the seme-uke rule with three Japanese idol shippers I met at a K-pop merchandise store in Ikebukuro in 2020, I learned that it was rare for the authors of Japanese shipping fan fiction or comics to position members as switching their sexual roles. Further, these women reinforced the idea that an uke is somehow “feminine” (onnarashii), with one fan suggesting that the youngest member of BTS, Jungkook, was like a “young princess (ohime-sama kyara) protected by six knights.”41

Except for two prominent examples both involving RM, the leader of BTS, an older member of BTS is always presented as the seme and a younger member is presented as the uke within each of the BTS ships listed above. The texts in the “mook” stress the brotherly nature of each pairing, such as in the following description of the Jimin x Jungkook couple: “whenever he has free time, somehow Jimin nii-san (older brother) comes over to Jungkook. Usually Jungkook treats Jimin as if he is some kind of nuisance, but it is clear that Jungkook enjoys being spoiled by this loving older brother.”42 Following the narrative and characterization conventions of the seme-uke rule, the status of one member as an “older brother” provides him with power and thus positions him as a logical seme for Japanese fans. Further, the focus on “watching over” (mimamoru) and “spoiling” (amaeru) in the descriptions in this “mook” of each couple’s uke replicates common-sense understandings of romantic relationships in Japan, where a man (or “masculine” seme) is expected to take charge of a relationship with an innocent woman (or “feminine” uke). The two cases where this age-based shipping is not practiced in the eleven potential couples from The BTS Fanatic’s Manual are where the group’s leader RM is positioned as the seme. Within the texts of these two ships, rather than RM’s age, it is his status as leader of BTS that positions him as a powerful seme, particularly in the description of the RM x Suga couple, where the two members are described as the group’s “father and mother” (fūfu kappuru) figures, respectively.43

This brief example shows that Japanese idol shippers follow logics that appear somewhat rigid, slotting K-pop band members into a predetermined gendered formula based on traits such as age or position in the band. What appears most important within the Japanese context is the broader positioning of boy band members as either seme or uke, which in turn influences how consumers present the gendered identities of the characters within their derivative fan works. It is for this reason that the fans I met in Ikebukuro fantasized about Jungkook being a “princess” protected by six older “knights.” The categories of seme and uke are not understood by fans as identities, however; many young women I interviewed strongly disavowed the idea that the characters appearing within fan works were gay men defined by their sexual desires. Rather, our conversations revealed that the descriptors seme and uke were used to make sense of idol behaviors, either in reality or within fan works, with debates over who represents a seme or an uke producing an affective response known in Japanese as moe. Indeed, these K-pop shipping practices mimic how Japanese Boys Love manga fans also derive explicit pleasure from their supposed “moe talk” (moebanashi).44 Fans thus creatively manipulate the character tropes of the seme and uke to produce homoerotic relationships between male idols that are charged with romantic or erotic potential, providing meaningful ways for them to celebrate the K-pop idols they adore.

While the logics of Boys Love manga have rightly been criticized as replicating heteronormative relationship structures by implicitly positioning the seme and uke as figurative men and women,45 I do not want to dismiss the queer potentials of such fandom practices. Through fantasies of homoeroticism created through the manipulation of the seme-uke rule, Japanese female fans mobilize queer sexuality as an important method to express their own attraction to K-pop idols and thus produce pleasures that theorists such as Ono acknowledge as explicitly sexual.46 The seme-uke rule therefore provides a framework and vocabulary with which to vocalize and celebrate the inherently erotic affects induced by K-pop fandom. Ultimately, Japanese fans draw on a preexisting tradition with a long history in Japanese girls’ culture as one of many methods to make sense of their attraction to the members of popular K-pop groups. K-pop idol shipping thus represents a significant emerging practice in Japan’s girls’ culture that deploys queer sexual expression to conceptualize young Japanese female fans’ sexual and gendered identities.

Shipping BTS in Anglophone Fandom: Queer Sexuality and the Politics of Identity

One Saturday in January 2020, I joined over a hundred passionate fans of BTS at an inner-city gallery in Sydney to attend a photography exhibition dedicated to members Jimin and Jungkook that had been collaboratively organized by Australian and South Korean social media fan sites. As I wandered and interacted with fans throughout the day, I learned that many of those who had gathered in the gallery had come to celebrate what an organizer termed the “close relationship” between Jungkook and Jimin,47 as well as to purchase fan-produced merchandise featuring this popular pair. Although the event was advertised as targeting all ARMY, a significant portion of the attendees with whom I interacted identified as shippers of Jimin and Jungkook, a pairing known in Anglophone fandom as “Jikook.” Unlike in Japan, however, many of the shippers I met at this Sydney gallery were gay men who viewed their K-pop fandom as intrinsically tied to their queer sexual identities (throughout the day I met eight such fans). This did not surprise me, as previous research I had conducted among LGBTQ consumers of Japanese and Korean popular culture in the Philippines, where K-pop fandom is particularly prevalent in the LGBTQ community,48 showed that queer Philippine fans also practice K-pop idol shipping. My experiences with English-speaking BTS fans in Australia and the Philippines confirmed that K-pop idol shipping was common in Anglophone fandom spaces.

Unlike in Japanese and South Korean fandom, where the logics of the seme-uke rule and influence from Boys Love manga fandom have strongly shaped shipping practices, idol shipping within Anglophone contexts appears more closely aligned to an identity-based conceptualization of queer sexuality born out of LGBTQ identity politics. By LGBTQ identity politics, I refer to the common tactic within Western queer liberation activism where concrete identity categories such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender are deployed as a form of strategic collective action.49 My conversations with fans in Australia and the Philippines who actively participate in idol shipping culture online – typically reading and writing fan fiction or engaging in shipping debates on social media such as Twitter – found that Anglophone fans tend to conceptualize shipping as an explicit reimagining of idols as identifying as members of the LGBT community. Marcus,50 a gay Australian fan of both K-pop and Japanese manga, explained to me during a conversation in 2019, “When I ship BTS, it’s kind of like a fantasy where I imagine my bias [favorite member] is gay and likes boys.”51 Likewise, a bisexual fan of BTS in the Philippines named Maria noted that she liked “taking the members of BTS and making them gay,” explaining that shipping was a process of “turning the boys queer.”52 Interestingly, Maria viewed idol shipping as a political act that helped to “raise the visibility” of “queer identity” in the context of the “heteronormative culture of the Philippines.”53

Another queer Filipino fan named Leon likened K-pop idol shipping to “gay porn,” noting that both queer and straight fans “imagine our favorite members fucking” as a way to enjoy explicit sexual fantasies of “hot boys who turn us on.”54 I also encountered this positioning of K-pop idol shipping as a form of pornography during a conversation with a gay male fan and his heterosexual female friend at the gallery event in Sydney, with both suggesting that the “power” of “shipping Jikook” came from repurposing the two members’ close “brotherly” relationship as a “hot gay fantasy.”55 Even many heterosexual female fans I met in Australia made similar comments. For instance, a Chinese Australian K-pop fan named Lisa explained to me in 2018 that while she did not practice shipping herself, she understood it as a form of “gay porn” among some Australian fans.56 As these narratives suggest, K-pop idol shipping is one method through which fans celebrate and express sexual attraction to idols through erotic fantasy play. In so doing, they consciously utilize the language of LGBTQ identity politics to label the members as explicitly same-sex attracted, making this the central focus of the fantasy.

In English-language fan fiction for BTS on Archive of Our Own, one of the world’s largest online fan fiction repositories,57 most of the uploaded shipping fics position at least one of the members as directly identifying with their same-sex attraction (e.g., identifying as gay, bisexual, queer, or poly[amorous]). A search for the word “gay” reveals that 60.3 percent (61,497/101,964) of male-male BTS fan fiction hosted on the site deliberately deploy the term to either identify a character or describe the sex acts that occur between members. A minority of BTS fan fiction takes this even further, strongly tying the shipping of idols within erotic, romantic, or pornographic contexts to explicit LGBTQ activism. One example is a fan fiction entitled The Paradiso Lounge, which explicitly situates a highly pornographic romance between BTS members Suga and Jimin within the context of New York City’s 1990s BDSM community. Tagged as specifically concerned with “social justice,” the fic reimagines Yoongi (Suga’s real name) as a queer activist photographer who eventually falls in love with Jimin, a sex worker at an underground leather bar. The following excerpt provides an example of how The Paradiso Lounge ties K-pop idol shipping to broader LGBT activism:

“Oh, you document the community?” Jimin asked in an interested tone, retrieving an ashtray from the edge of the table to place it down in the middle for them to share. “Does that mean you travel around the city a lot? Snapping photographs of gay establishments and safe spaces? Going to the HIV and AIDS protests, and all the other marches and protests? Is that what you document?”

“I’ve been ’round,” Yoongi said with a lazy nod, finding it far easier to study the glowing cherry of his cigarette than to hold the other man’s gaze. “I’ve been right to the heart of the community, y’know, the protests, the condom and needle drives, the fundraisers – the social aspect that keeps us going in this toxic society. But I’ve been to the fringes too like, uh, the radicals, the militants. The radical feminist lesbians, the pinko faggots; the kinda gays that exist in our community that the gatekeepers don’t talk ’bout ’cos they’re a threat to the heteronormative society far too many think we should accept a part in, rather than refuse to conform to.”58

Throughout my conversations with Anglophone fans, I learned that most who practiced idol shipping were keenly aware that it was based in fantasy, and none believed that the members of BTS who they shipped together were actually attracted to the same sex. Rather, as Marcus explained to me, idol shipping was a kind of “play” designed to enjoy their fandom for BTS in “exciting and sexy ways.”59 In this sense, despite the logics that influenced their conceptualization of shipping being radically different, both Japanese and Anglophone BTS shippers are involved in a highly creative and affective practice tied to their desires as fans. For Sandy, a bisexual female fan in Australia, shipping BTS (and she noted that she also shipped members of the K-pop girl group 2NE1) represented just one of many methods to “express my love for the members of the band.”60 She explained it was a “release valve” for the sexual tension that fans of BTS often express, suggesting rather humorously that “you have to do something to scratch that itch when you see the boys grinding against each other on stage!”61 Ultimately, K-pop idol shipping possesses queer potentials through its celebration of male-male erotica, which allow fans to vocalize and explore their sexual attraction, acknowledging that sexual desire plays an important role in broader K-pop fandom.

Not all fans of BTS in Anglophone contexts view K-pop idol shipping positively. Within Western fandom spaces there have been long-running historical debates concerning the ethics of “real person shipping.”62 In an article polemically titled “Your OTP Is Not Real: Why Idol ‘Shipping’ Has No Place in K-Pop,” a contributor to the K-pop blog Seoulbeats argues that shipping is “a potentially harmful activity to both the fans and idols in question” because it supposedly promotes skewed understandings of same-sex relationships among fans.63 The author concludes by arguing that shipping is a “self-indulgent activity when real people with real feelings are the ones being manipulated for the sake of entertainment and fantasy,” suggesting that instances where K-pop production companies produce content aligned with shipping represent “a step too far.”64 This is a pervasive discourse within Anglophone spaces that seems to be absent within both South Korean and Japanese K-pop fandom, and some BTS shippers I interviewed in the Philippines had strong criticisms for those who held such views. A bisexual fan named Zoe argued that such critiques neglected the fact that fans understand that they are involved in fantasy play, strongly disassociating shipping from reality.65 As Maria strongly believed shipping was a queer political act, she likewise viewed such attempts to censure shipping as a form of heteronormative backlash designed to silence fans engaged in subversive practices.66 While there are important ethical debates to be held over shipping real people, especially within highly pornographic fan fiction, this does not negate the fact that the fantasy shipping produces is a legitimate way to explore the sexual desires central to K-pop fandom.

Concluding Remarks

As Myra suggests in the webcomic that opens this chapter, idol shipping is a fundamental element of global K-pop fandom that deploys queer sexuality to produce affective responses among fans. Initially emerging as a bottom-up fan practice that allowed young women in South Korea to express and play with their sexual desires safely in the context of societal patriarchy, idol shipping was soon co-opted into the production processes of K-pop by entertainment companies keen to exploit young women’s significant economic clout. Through a case study of shipping practices among fans of BTS in Japan, Australia, and the Philippines, this chapter has demonstrated that while the cultural context in which a fan is situated shapes shipping practices, fans around the globe practice idol shipping as a method to explore the sexual desires for the handsome idols that sit at the heart of the K-pop industry. Whether understanding the imagined homoerotic relationships as tied to the seme-uke rule central to Boys Love manga in Japan or drawing on the logics of LGBTQ identity politics in Anglophone contexts, fans are united in their commitment to idol shipping as a form of fantasy play. This fantasy play, I argue, both queers dominant social understandings of sex and gender and allows for the expression of fans’ own gendered and sexual identities as desiring subjects.

To conclude this chapter, I wish to briefly reflect on the importance of K-pop idol shipping to the LGBTQ community. My conversations with queer fans of K-pop in Australia and the Philippines routinely raised the issue that while K-pop fandom is often considered to be a safe space for same-sex desiring and gender-nonconforming individuals, the contents of mainstream K-pop production often lack explicit queer visibility. Sandy, for instance, recognized that while her K-pop fandom had helped her to understand her sexuality as a bisexual woman, South Korea remains a homophobic society and there are very few openly queer idols (Sandy spoke positively of Holland, however, who is an indie idol famous for explicitly centering his identity as a gay man within his performance).67 For such fans, idol shipping injects a necessary corrective into K-pop fandom. Sandy drew on the logics of the LGBTQ identity politics that influence Anglophone fans’ conceptualizations of shipping to suggest that the practice helps ameliorate the lack of queer representation within the K-pop industry and would eventually lead to changes to social attitudes in South Korea.68 In this way she echoed the opinions of my Philippine interlocutor Maria, who viewed idol shipping as a necessary queer political act.

Within her work on gay FANtasy, Kwon celebrates the potential of K-pop idol shipping to transform the heteronormative nature of the South Korean media landscape through increasing positive visibility of queer communities.69 She finds through her interviews with gay men in South Korea that many view practices such as idol shipping as positively shifting the conversation on queer sexuality among K-pop fans.70 I have encountered similar beliefs among gay Japanese men who are fans of K-pop. As Aki, a twenty-two-year-old man, explained to me in 2015, K-pop idol shipping “bridged the considerable gap” between heterosexual female and gay male fans in Japan.71 Although he did not practice shipping himself, Aki firmly believed that such fan practices among the “typical female fans of K-pop” would “open their minds to the presence of gay fans” and thus produce a more inclusive fandom culture.72 More investigation of the entanglements of K-pop idol shipping and LGBTQ fans will be necessary to fully understand the transformative potentials of shipping in increasing queer visibility within this global fandom. Nevertheless, K-pop idol shipping plays a transformative queer role in a variety of cultural contexts, demonstrating how queer sexuality is fundamental to K-pop fandom culture.