Introduction

In trying to understand how the Sephardic musical repertoire was performed in the past, we must take into consideration the relationship of each song to two important defining parameters: genre and social function. This question arises in the study of the repertoire in the two main areas of the Sephardic diaspora, namely, the Eastern Mediterranean (the Ottoman area, later Turkey and the Balkan countries, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Greece) and the Western Mediterranean (Northern Morocco), as well as in Israel and the many places to which Sephardim later dispersed, and where the Judeo-Spanish musico-poetic repertoire has been maintained until the present day. The subject of the performance practices associated with Sephardic music involves both the traditional ways the repertoire was once performed, and the ongoing styles and techniques of its performance today.1

This chapter explores the songs that are either secular (non-religious in content) or paraliturgical (related to religious matters but with texts that are not in Hebrew but in Judeo-Spanish). The repertoire is predominantly vocal, sung in the Judeo-Spanish language, which is a Spanish dialect based on the language that the Jews spoke in Medieval Spain, where they had lived for many centuries before their final expulsion in 1492. The Judeo-Spanish language developed as its speakers borrowed from Hebrew and from the languages of their new surroundings. It flourished in two parallel dialects, one called “Judezmo” or “Ladino” in the Eastern area (with additions from Turkish, Greek, and Slavic languages), and the other called “Haketia” (with additions from Berber, Arabic, and Moroccan Arabic dialect) in the Western area.

In this chapter, we will consider the following questions in regard to the performance of Sephardic songs: What is the genre of the song? Who sings it, men or women? Where is it sung? When is it sung? And how is it sung, as a solo or in group singing, and with or without instrumental accompaniment? We will consider the function of examples from each genre in the lives of the individual and of the community, and as part of the repertoires of songs for the year cycle and for the life cycle.

Traditional performance

Modes of performance, as well as characteristics of text and music, differ in the cases of each of the Sephardic traditional genres, the romance, copla, and cantiga, collections of which are known as the romancero, coplas, and cancionero. These genres vary in: 1) their rendering, whether by solo or group; 2) the presence or absence of instrumental accompaniment; and 3) their gender definition, that is, whether they belong to the male or the female repertoire.2

I Romancero

The term “Romancero” means a collection or corpus of romances, which are narrative poems with a well-defined textual and musical structure.3 Their texts typically relate to the Spanish Middle Ages, involving kings, queens, princesses and galant knights, prisoners, and faithful (or unfaithful) wives. Other romances’ texts involve classical, historical, and even biblical themes.

Several old romances reflecting historical events have been forgotten in Spain but preserved in the oral tradition of the Sephardic Jews. One such romance relates the struggle between the children of King Fernando I of Castile and León (1016/18–65), Sancho, Alfonso, and Urraca: Sancho II from Castile puts his brother Alfonso (King of León) in prison, and his sister Urraca (of Zamora) intervenes to achieve Alfonso's freedom (Song 1).4

Romances are rendered as solo songs, with no instrumental accompaniment, and it is predominantly women who perform the repertoire and are responsible for its transmission. The music of the romances often has an ornamented melody and uses Eastern modes (the Arabic and Turkish makamat) that include microtonal intervals (narrower than the half-step) not found in the Western diatonic scale.

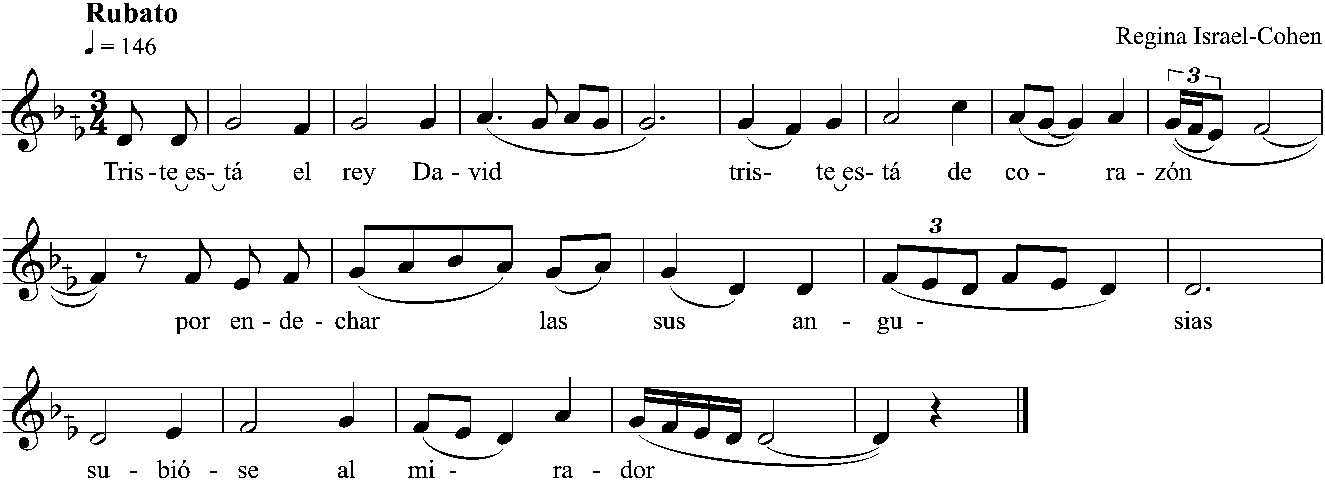

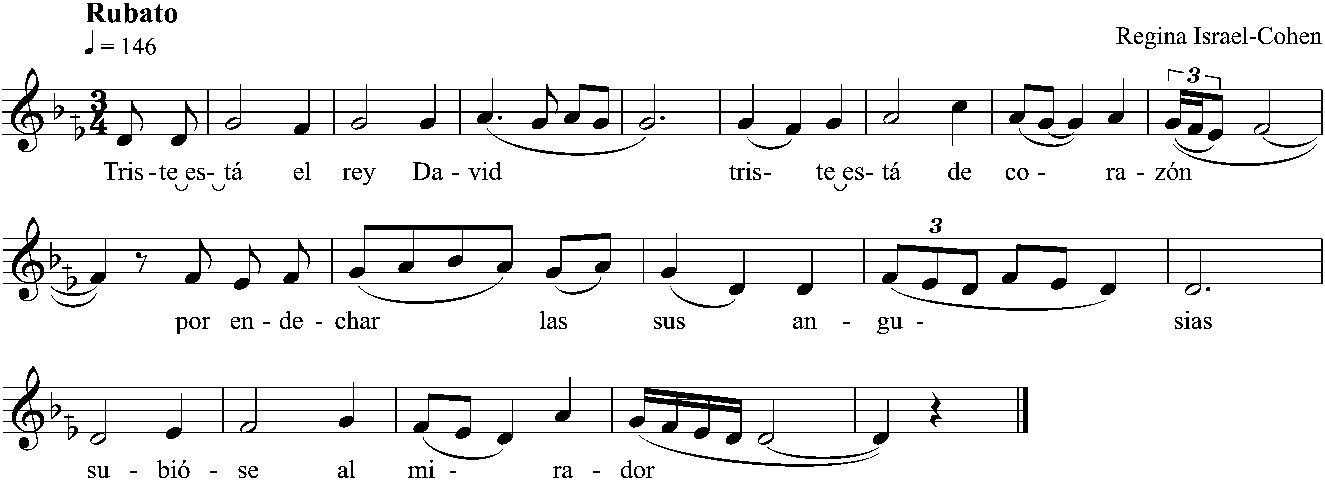

The next example, from Saloniki, Greece, has a melody in a free rhythm (without repeating accent patterns) built on a makam called Husseyni (with a lowered second degree), and features melismas (series of different pitches sung to a single syllable) at the end of each musical phrase (Song 2; Example 7.1). The romance tells the story of a fidelity test. A husband returns after many years away at war and asks a woman washing at a well for a cup of water; he asks why she is crying, and she explains that her husband has not returned from battle. She gives him her husband's description, after which he declares that her husband has died and told him to marry her. When she refuses, he reveals that he is her long-lost husband.6

Example 7.1 “The Husband's Return.”

The Romancero belongs to the women's repertoire, and its most common function is that of a lullaby, except in the case of a few romances that are included in the wedding repertoire, sung by groups and accompanied by percussion instruments. The previous example was a romance sung on the occasion of the preparations for the new couple, when the wool for the pillows and mattresses was washed by members of the community. The following song is also from the wedding repertoire, and its text relates the story of a married woman wooed by a young man who sends her love letters and presents, but she sends all of them back and remains true to her husband (Song 3). This narrative seems appropriate as advice for a bride. (Because the whole group sang it, men knew this song as well as women, as is evident from the name of the singer of this romance.) The romance closes by quoting a liturgical text with verses in Hebrew and their translation into Spanish.

An interesting trait of the performance of the previous two examples is that they are sung in a special manner referred to as “concatenation.” To demonstrate this technique clearly we can consider two musical strophes of the Saloniki romance, “Lavaba la blanca niña,” in which the second half of the text in one strophe is repeated at the beginning of the next. (Thus, the music is structured in four phrases, repeated, as usual: abcd, abcd…; but the text, with its repetitions, follows the scheme 1234, 3456…) In this way the listener can participate every time the text is repeated in the next strophe.

A few other romances may be sung as dirges or for Tisha B'Av (literally, the ninth of the month of Av, a day of fasting to commemorate the destruction of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem). On the occasion of a death in the family, professional women referred to as endechaderas or oinaderas used to perform a special repertoire of dirges called endechas or oínas. From this repertoire the endechadera selected those dirges whose subjects were the most appropriate to be dedicated to the deceased's memory.9 More recently, in Israel as well as abroad, this function declined, dislocated by the uniformity of the official death rites in modern times. According to my informants, in the late 1980s the last endechadera, from Alcazarquivir (Morocco), died in Eilat. The endechas as such became obsolete songs, seldom performed, and then only on request and not by everyone, for it is considered a bad omen to sing them.10 Some of the endechas, such as “David Mourns for Absalon” (Song 4, about King David's grief for the death of his rebel son Absalom) have retained part of their function as dirges: they are kept among the corpus of endechas or qinot for Tisha B'Av and are still sung on this fast day (Example 7.2). The text of “David Mourns for Absalom” describes a scene in which King David receives a messenger who brings sad news: David's son Absalom, who took arms against his father, died when his long hair became caught in a tree and he was stabbed there. David calls upon each of his family members to mourn for Absalom.11

Example 7.2 “David Mourns for Absalon.”

II Coplas

Coplas (or complas) represent a distinct repertoire, clearly differentiated from the Romancero and the Cancionero. They are strophic songs, with varied but consistently patterned textual structures, sung to repeating melodies that show clearly the influence of the surrounding musical cultures. Their textual content, unlike the romances’, is related to Jewish tradition, history, and social and political events, and it always exhibits characteristics of continuity and coherence – a feature shared with the romances – but in strophic structures (in which the poetry is divided into stanzas of the same repeated form, and the music is equivalent for each stanza of poetry), a point of difference from the romances. This genre flourished in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when many coplas were published in Constantinople, Saloniki, Vienna, and Livorno.13

In regard to their performance, the coplas are mostly rendered in group singing, often accompanied by hand-clapping. Since many coplas are passed down in writing, they belong to the realm of men, unlike the Romancero, which, being mostly of oral transmission, belongs to the female repertoire. Thus, the coplas are mostly sung by men or, when the group participates, it is led by a man, as it is the men who are (or were) able to read the Hebrew Rashi letters (a Sephardic semi-cursive script) used for writing Ladino in printed texts. This is most evident in the repertoire of paraliturgical coplas for the festivities of the Jewish year cycle, sung from printed booklets and performed at home, in performances led by the man in the family. The main goal of the coplas was didactic, to provide information about the Jewish festivities and the transmission of Jewish knowledge and values to those (predominantly women and children) who could not read Hebrew and therefore had no access to original sources.

The Jewish feast most often celebrated in the coplas repertoire is Purim, a holiday in the Jewish month of Adar (around February) that commemorates the salvation of the Persian Jews by the intervention of the Jewish queen Esther, following her uncle Mordechai's advice. Even the duties to drink and be merry on Purim are reflected in the copla texts.14 Coplas are very long, especially when they are sung from printed texts, and in the following example only a few strophes are presented (Song 5). The text is structured in four-line strophes, in which three lines rhyme (they have the same vowels at the end of each line), while the fourth rhymes with the fourth line of each of the other strophes.15

III Cancionero

The songs of the cancionero are called canticas or cantigas by the Eastern (Ottoman Balkan) Sephardim, and cantares or cantes by the Moroccan Sephardim. Like the coplas, they have great versatility of texts and music, and are deeply influenced by the surrounding local cultures. Some Sephardic songs are known to be translations or adaptations of Turkish, Greek, or Bulgarian songs.

The songs of the cancionero differ from the two other genres – romancero and coplas – in textual and musical structure, involving mostly quatrains (four-line strophes, with a rhyme scheme of abab or with only the second and fourth lines rhyming), very often with a refrain; accordingly, the melodies are strophic, with a different tune for the refrain. The texts of these songs are not continuous, either according to a narrative or by any other means, and the order of the strophes is not fixed (as in the Turkish şarkı). Their subject matter is mostly lyric.

In its performance the Cancionero has more variable traits. The canticas or cantigas are sung either as solos or by groups, and by men and women. A distinct corpus of songs from the Cancionero forms an important part of the nuptial repertoire (cantigas de novia or de boda), as they are performed at the various ceremonies of the Sephardic wedding and are accompanied, in both Eastern and Western communities, by percussion instruments, especially the tambourine, which is called pandero or panderico in the Eastern area and sonaja in Morocco. The most common metric pattern for the accompaniment in both areas is the duple 2/4; in the Balkan states, 7/8 and 9/8 are more typical, and in the Moroccan repertoire, 6/8 is found (often in the “hemiola” type: 3/8 + 3/8 + 2/8 + 2/8 + 2/8).

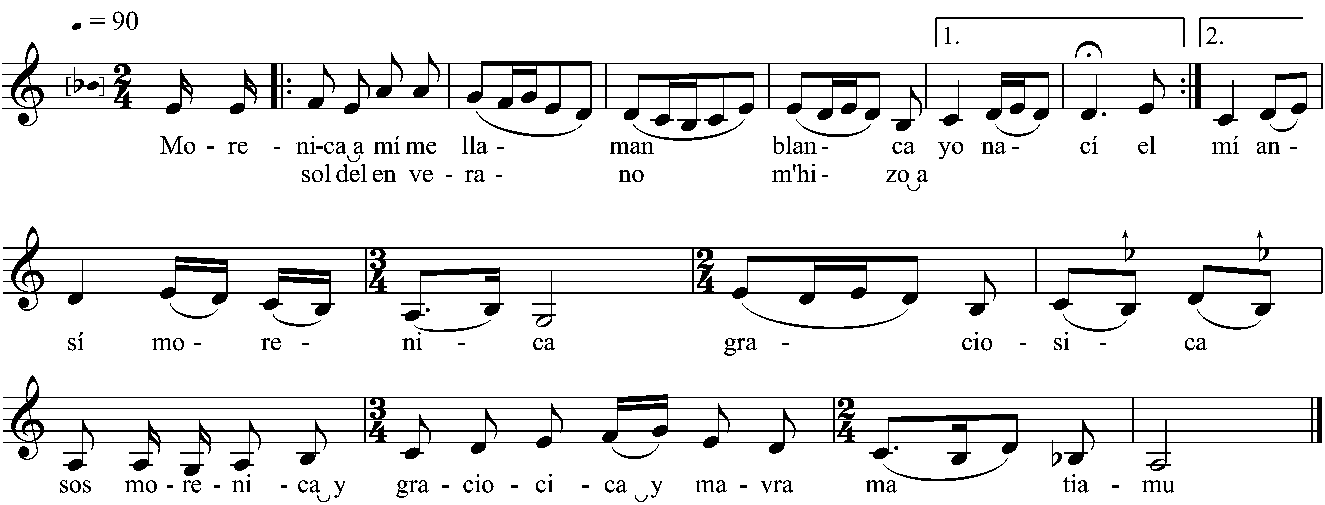

The wedding songs are sung or led mostly by the women, especially those for specific wedding rituals at which only women are present, such as the bathing or dressing of the bride. A common manner of performing the wedding repertoire in both the Ottoman and the Moroccan areas is to sing a series of different songs that share a common rhythmic organization. One well-known song in this genre is about a beautiful brunette (morena or morenica) who, as is described in the biblical Song of Songs, had white skin that darkened in the summer sun (Song 6; Example 7.3). The many strophes (only some of them are presented here) have no specific relationship to one another and may be sung in any order, although there are parallel subjects and similar enunciations in some pairs of strophes (and in other versions, even in more than two strophes) in a serial literary structure: as can be observed in the text, the first two stanzas have the same first line (the call to the brunette); likewise, in the third and fourth stanzas, we find the same first line (“tell the brunette”); and the fifth and sixth stanzas again share the same opening line (“the brunette gets dressed”) and a similar formulation about what colors the brunette wears, with comparisons to different varieties of fruit. Each strophe is followed by a refrain ending in the Greek words mavra matiamu, meaning “black eyes” (probably inherited from a Greek song). The melody is in makam Bayati (a mode with the second scaled degree, lowered to half mol – an interval smaller than the half-step – with the dominant occurring on the fourth degree).

Example 7.3 “Morenica.”

Weddings commonly involved the participation of a semi-professional female singer called a cantadera, and the accompaniment of pandero-players called tañederas. These performers were specially invited to every joyful event, such as weddings and circumcisions. They were not payed directly for their participation, but cash donations from the public were collected during their performances to benefit causes such as the dowry of a poor bride, or the purchase of children's clothing for families in need. In terms of status, there was great pride in being a cantadera or a tañedera.

In addition to playing the tambourine as instrumental accompaniment, Moroccan Sephardic women add the castanets, which are often held on the middle finger of one hand and stroked by the fingers of the other hand. In the Turkish area the women often use the parmak zili (in Turkish: finger-cymbals), two pairs of tiny cymbals attached to the thumb and middle finger of each hand. The darbuka or dumbelek (a cup-shaped drum made of clay or metal, with one skin) are played in both regions, and Bulgarian Sephardic men also play a large cylindrical double-skin drum called a baraban.

The last example is from Bulgaria (Song 7). It is a wedding song performed at the marriage feast, and its music has a rhythmic structure in 9/8 meter, ordered as 2+2+2+3, a pattern widely used in Balkan folklore.

In Jewish wedding feasts, celebrants hired professional musicians, some of whom were gentile performers. In such cases, instrumentalists (violin, ’ud, daire, kanun) of different origins participated: there were ensembles of gypsies, known as ziganos, or of Greeks, called banda de gregos, or Turkish players called chalguí (Tur.: çalgı) or chalguigís (Tur.: çalgıcı) who, through their frequent participation at such occasions, knew the Judeo-Spanish repertoire and could accompany the cantigas de boda in addition to playing dance music (including Turkish dances, as well as the waltz, foxtrot, tango, and other Western genres).

Performance of Sephardic songs today

The preceding descriptions of traditions associated with the performance of Sephardic songs reflect musical practices in Sephardic communities before the twentieth century, when modernity and European influence brought about changes in the preservation and performance of Sephardic songs, and, in most cases, caused the tradition to be almost forgotten. As is well known, the preservation and continued performance of any musical tradition depends on its functionality, but the practices sustaining the Sephardic musico-poetic repertoire began to decline by the middle of the nineteenth century, with the modernization of society. The new generations, especially those born in the new settings to which their parents had immigrated, tried to fit in amid their new surroundings, learning the local languages and customs, and in most cases they did not maintain the Judeo-Spanish languages or the cultural treasures of their elders. It seemed that there would be no continuity to the Sephardic musico-poetic tradition. Thus, the performance of the Judeo-Spanish repertoire found its place on stage, in the renditions of professional artists interested in this repertoire in a great wave of Sephardic renaissance.

The deep interest in the Sephardic musico-poetic repertoire inspired the appearance of an astonishing number of professional performers. Many soloists and ensembles (mostly not of Sephardic descent) chose to specialize in the Sephardic repertoire in stage performances and on sound recordings. I will not get into a discussion about the necessity, importance, or desirability (questioned by some scholars and even entirely denied by others) of this phenomenon, nor shall I touch on its sociological aspect (including its impact on the public and questions of the cultural backgrounds and ages of audiences, etc.), but its buoyant and thriving existence must be acknowledged.

Such performances of the Sephardic repertoire on the stage and in sound media often involved a very small part of the rich Judeo-Spanish repertoire and were based on careless transcriptions of the authentic sources. Furthermore, these performances were accompanied by instrumental arrangements for ensembles that were absolutely alien to the original style and required (and – alas! – achieved) a pitiful simplification of the rich melodic ornamentation and varied rhythmic structures that characterized the music of the Sephardic repertoire, ignoring even the Oriental modal organization that was the basis of its melodies.

I will consider here some of the aspects of this phenomenon that I might name the “stage-recycling of the Sephardic repertoire,” and point out its problems. In order to understand the problematics of stage performance it is important to consider the wide gap between what we could call “the natural situation of the traditional event,” and this “stage-recycling of the repertoire.” This gap is related to the dichotomy between performer and public in contemporary performance, a dichotomy that does not exist in the traditional setting, where, even if the audience members do not know all the songs performed, they feel a sense of belonging in relation to the event. Even if they cannot sing along to every verse, they are involved in a sort of “passive participation,” based, 1) on the general knowledge of the repertoire and the outline of its contents; and 2) on the learned ability to recognize the context of and feelings expressed in each song.

Especially important among the general traits of contemporary “stage-recycling” performances is the loss of the musical context, through the separation of the songs from the activities they used to accompany. An example of this decontextualization is the romance of “The husband's return,” with the incipit “Lavaba la blanca niña” (see Song 2 above), which used to be sung in Saloniki when the women of the bride's family assembled to wash the wool for the mattresses and pillows for the new couple; this romance has now become a nostalgic souvenir, as this activity is no longer necessary and all the dowry can be bought ready-made. Despite the ethnomusicologist's expectations of professional performers, it is certainly very difficult for them to build a new bridge over the abyss opened by the loss of context.

The question of how close one can come to reproducing the original performance practice is not an easy one. Two aspects are to be considered here: voice and instruments. The first is the most difficult, because the professional artist probably had vocal training that does not correspond to the typical vibrant singing voice of the Sephardim. Recognizing this challenge, I most enthusiastically applaud the efforts of some contemporary groups to lower the register of their voices and change their timbre. The second aspect, instrumental accompaniment, is one method by which professional artists attempt to make their Sephardic songs more likeable for their audiences. The accompaniment practices of today's professional performers of this song repertoire can be classified into four groups:

1) those that prefer the “old look,” with medieval or Renaissance instruments and corresponding vocal settings (and sometimes even costumes from those eras);

2) those that turn to the eastern sources, using instruments such as the ’ud, qanun, darbuqa (a globlet-shaped drum), and, of course, tambourines of different sizes;

3) those that perform solo and do not budge, setting all kinds of Sephardic tunes to the ill-suited and limiting chords of the guitar; and

4) those that choose their instrumental accompaniment according to the song, considering its social function, its original mode of performance, and the time of its origin: medieval instruments for epic romances, ’ud for certain songs and coplas from the life-cycle repertoire, guitar for the more modern canzonetta-style love songs, or just panderos (tambourines) for the eastern Sephardic wedding songs, with the addition of castanets for the Moroccan Sephardic wedding repertoire.

Thus the contemporary professional performance of this repertoire is varied, and the performers’ choices testify to their musical sensibility and historical and cultural knowledge.

The impossibility of recreating the tightly knit form of communication between the singer and the group (as it occurred in the traditional performance settings) has led professional performers to seek different solutions, many of which are ill-advised. One technique for attracting the public's attention, shared by stage performers of all sorts, involves the use of lighting to define the spaces of the performer and the public. We know, however, that lighting, most certainly, does not bring the audience any closer to the singer on stage, nor does it enhance the feeling of belonging that characterizes the traditional setting. Many performers also sing selections of a reduced and stereotyped repertoire, ignoring the best jewels of the Sephardic musico-poetic heritage in favor of a set of five or six well-known pieces, almost all of them lyric songs (about the sufferings and joys of love), and learned mostly from earlier commercial records.

One bright light shines from those groups that, having a greater sensibility for the tradition, have started to look for authentic sources, renewing the repertoire on stage with songs from local repertoires, with no fear concerning the acceptance of this “new” material by their audience.19 Audiences, following these groups’ choices with interest, seem to have begun to open up and enjoy gratefully the “new” gifts from the Sephardic repertoire. And here we will conclude this chapter by allowing the subject of how to perform Sephardic songs on stage today to remain an open question.