Ancient Israelite culture and music

Music is a ubiquitous means of expression and communication and an indelible part of nearly every ancient and modern culture. It transcends spoken language, ethnicity, and chronology. People craft musical sounds in multiple creative ways, including to match the sounds heard in nature. These organized sounds become features of a culture. Sometimes combined with words or other unique human sounds, music becomes a way of life, and people use music to mark cultural and life cycle events such as birth, death, illness, war, travel, and entertainment. Moreover, the objects used to create music come from nature. They are often organic materials such as various types of wood (e.g., bamboo, acacia), clay, and animal remains (e.g., bone, sinew, teeth), and at times nature itself may be the instrument – for example in stomping or beating on the ground, the slapping of bodies of water, and the manipulation of the air to make tones by twirling overhead instruments like prehistoric bullroarers.1

Music sets the mood of an event or activity. For instance, in past cultures and some today, wailing women and men assist in the mourning process and in honoring the dead (Celtic, Africa), celebratory songs uplift soldiers returning from victorious battles, and mnemonic lyrics help to teach valuable school lessons to children, convey clandestine messages, and preserve family lineages and cultural history.

The geographical focus of this chapter is the land of Israel during the Iron Age (1200–586 BCE), a time identified by many as the biblical period. Ancient Israelites used music in many similar ways. Unfortunately the exact sounds and most intricate details regarding early Israelite music are lost and unrecoverable at this point. Ancient texts, however, in particular the Hebrew Bible and archaeological artifacts, give insight regarding performers, the types of instruments used, and possible performance contexts. Scholars continue to discover and research informative aspects of ancient Near Eastern cultures in general and the Israelites in particular. The relatively new field of archaeomusicology contributes to our understanding of the development and use of music in early societies. This chapter employs the discipline to explore the roles of music in Israelite culture, the primary characteristics of the music, the types of instruments used, and the questions of who served as musicians and where these musicians performed.

Types of instruments in early Israel

Ancient and modern instruments are typically classified using the Sachs-Hornbostel system of chordophone, aerophone, membranophone, and idiophone, which is also referred to as the CAMI system. The following is a brief description of each instrument classification, modern equivalents, and early Israelite examples.

I Chordophones

These are stringed instruments. A string or strings are often stretched across a surface, and the player strikes or plucks the string with the hand or object (e.g., pick, plectrum). The player may also rub a bow across the string to produce sound. The vibration of the string creates the sound, and the tautness of the string determines the pitch. In some chordophones, the strings are stretched across a box, gourd, or other hollow body with an opening and connect to pegs usually at the opposite end of the instrument. When the player strikes the strings stretched across the opening, the sound is amplified. Modern examples of chordophones include the acoustic guitar and violin.

Chordophones in Early Israel. The lyre (Hebrew: kinnor) and harp (Hebrew: nevel) were the primary chordophones in ancient Israel. While these instruments are very close in design, there are important differences. The Israelite lyre has a basic U-shaped body. The arms are parallel, for the most part, and attach to a bar that lies across the top and connects them. Ornamentation or decoration of the wood often appears at the top of each arm (e.g., the head of an animal, a flower), and there are tuning pegs along the top of the cross-bar. The tuning pegs control the tautness and intonation of the strings, which extend down over the body of the instrument and connect the lower portion. The body of the lyre is usually hollow. The harp is angular in shape, resembling a sideways “V” or the letter “L.” The strings attach to the upper and lower arms, and like the lyre, there are tuning pegs on the upper arm. Israelite harps do not have a hollow body or sound box.

Archaeological artifacts and the Hebrew Bible show the popularity of these instruments, as they appear frequently in both. Hebrew Bible writers mention the lyre most often (in over twenty-four verses), and there are instances in which the lyre and harp appear together (Psalm 57:8). Likewise, the lyre is most prevalent in artifacts, often included in artists’ depictions or displayed with figures in figurines. It is important to note that in all of the examples available to us, no two are exactly alike, which suggests that the instruments were not mass-produced. The lute may have been an instrument played at specific times or in select events in Israelite culture, but many questions remain regarding its consistency among the instruments used and its identification in ancient texts.

II Aerophones

These are wind-blown instruments; Israelite aerophones included the pipe, flute, shofar, and trumpet. Generally speaking, the player blows air directly into the instrument, sometimes with the aid of a mouthpiece. Some aerophones have single and double reeds, which vibrate when air passes over them. Examples of modern aerophones include trumpets, tubas, oboes (double-reed), and saxophones (single-reed).

Aerophones in early Israel. The most popular aerophone in ancient Israel was the pipe (ḥalil), sometimes referred to as the flute. Because of the materials used in their construction (typically animal bone or clay), flutes do not survive well in the archaeological record. There are, however, remains of single and double pipes. The single pipe is similar to a whistle. It usually has one or two holes in the body of the instrument. The player blows into one end and covers or opens the holes on the body. The double pipe is the same type of instrument, but there are two pipes side by side or in a “V” shape, joined by string, clay, or other adhesive. The pipes typically have reeds, through which the player blows. One pipe may sound a drone, while melodic lines can be played on the other.

The Israelites also used the trumpet (ḥatsotsera) and the shofar. It appears that the Israelite trumpet was similar to the modern bugle in the way it was played. There were no valves or additional tubes like those found on the modern instrument; the player manipulated the sound with the lips. To date, archaeologists have not discovered any physical remains of the trumpet. The shofar, an aerophone constructed from an animal's horn, usually from a ram or bovine, is played in the same manner as the Israelite trumpet or bugle. While both instruments were a part of musical performance, they were also symbols of Israelite culture and were used as signalers and conveyors of information.

III Membranophones

These are instruments in which a membrane is stretched over an opening and the surface is struck with the hand or a stick or other object. There are many examples of modern membranophones (e.g., snare drum, congas).

Membranophones in early Israel. Membranophones often suffer the natural fate of artifacts made of organic materials, thus most of the examples available to us appear in drawings and figurines. The most popular membranophone in ancient Israel is the frame drum. The frame drum is similar to the tambourine, but the membranophones of ancient Israel did not have the metal jingles around the edges. There are questions regarding whether the drums were struck with the hand, or with a stick or other device. All of these possibilities are plausible and should be considered.

IV Idiophones

These are self-sounding instruments or instruments that sound within themselves. Modern examples include rattles and cymbals.

Idiophones in early Israel. Rattles and cymbals were the primary idiophones in ancient Israel. Rattles were made from clay and have been discovered in anthropomorphic and geometric shapes, as well as representations of vegetables and other objects. Peas, seeds, or hardened clay enclosed inside the rattle hit the walls and create a sound when the player shakes or strikes the instrument. Cymbals are usually played when struck against each other or with a stick. These discs average eight inches in diameter and are typically made of bronze.

V Miscellaneous instruments in early Israel

Some instruments can span more than a single category, but generally are placed in only one of them. Although not yet found in ancient Israel, tambourines, of which Middle Eastern types are known as the duff or daff, have jingles and a membrane, which place them in the membranophone and idiophone categories. Excavations have revealed that the Israelites used an Egyptian instrument called the sistrum. The sistrum is shaped like a paddle. A handle connects to an oval- or ankh-shaped frame. Jingles hang on wire strings that extend to each side of the body. When the player shakes or strikes the instrument, the jingles strike each other to produce sound. The sistrum was a favorite instrument of the Egyptian goddess Bastet.

General music of the Israelites via the Bible and archeology

The Hebrew Bible and archaeological artifacts paint a picture of an Israel in which people wove music into daily life, and because music was an integral part of the culture, everyone participated. The biblical writers describe inclusive musical activities in events such as Moses and the Israelites singing together following their daring escape from Egypt (Exodus 15:1); the celebration of a king once he is anointed (1 Kings 1:39–40; 2 Kings 9:13); and the sound of the shofar to praise an Israelite deity (Psalm 150:3). Music was a useful element that entertained, aided in teaching, and conveyed information.

Israelite musical performers

It is clear that music was essential in Israelite culture and a part of people's lives in numerous ways. Yuval is the first person the biblical writers mention who is connected specifically with musical instruments and musical performance, as well as with the etiology of music: “His brother's name was Yuval; he was the ancestor of all those who play the lyre and the pipe” (Genesis 4:21, New Revised Standard Version). The writers also describe cultural events involving music in which large groups of people or “all of Israel” participated (e.g., 1 Kings 1:40; 2 Samuel 6:5). Singing, chanting, clapping, blowing whistles, and shaking rattles are ways that were inclusive, but there were some individuals that had more specialized roles in musical performance.

Portrayals of the temple in Jerusalem present men working in several capacities (e.g., as priests, prophets, and gatekeepers), but in addition to these duties, some were musicians. The Chronicler explains that when David – who served as court musician for King Saul and was a popular psalmist – established a working system of assignments in the temple, he charged Asaph, Heman, and Jeduthun to prophesy with cymbals (1 Chronicles 25:1). They were also leaders in the performance of temple music. A number of singers and musicians were under their direction (1 Chron. 25:6). Music in the temple was elaborate and the relationships between participants were intricate. Musicians played trumpets, cymbals, harps, and lyres. There were choirs. Everyone had a specific location, and activities were carefully choreographed and synched.

In most musical scenes in the Hebrew Bible, it is implied or accepted that men were the primary performers. Women were a major part of ancient Israelite musical performance, however, and archaeology and the biblical text offer valuable information regarding their involvement. One of the first instances concerns Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron. Following Moses’ singing with the Israelites (“Song of Moses,” Ex. 15:1–19), Miriam leads the women of Israel in celebration of their escape from oppression. Miriam begins singing and dancing with a frame drum, and “all the women” follow her (Ex. 15:20–1). It is interesting to note that the writers state that all of the women in this celebration had drums. Women with frame drums dancing and singing together to celebrate victories appear to have been a traditional part of Israelite culture. A similar event takes place when David returns home with Saul and the rest of the Israelite army following his famous encounter with and slaying of the infamous Philistine giant Goliath. Women with frame drums and other instruments gather to meet the young warrior and King Saul as they make their way home following war with the Philistines. As the women play their instruments they sing a song, slightly disparaging to Saul, about the heroic accomplishments of David and the King (1 Sam. 18:6–7).

These women were participants in what Eunice Poethig calls the Victory Song Tradition.2 Women with instruments such as the frame drum serenaded victorious soldiers returning from battle. Jephthah's daughter also performs with drums and sings for her father as he returns home from a successful war. The victory song troupes and this type of performance appear to have been established cultural activities during this period in ancient Israel.

There are numerous female figurines dating to the time identified as the biblical period that display frame drums. For the most part, there are two styles of figurines: figurines in the round and plaque figurines. Figurines in the round are similar to small statues. Parts of them are made from molds and other parts are fashioned by hand. They typically stand on their own, and one can walk around them and view them from all sides. Plaque figurines are made from a mold and are usually leaned against a wall or some other object. Excavations at the coastal sites of Shikmona and Achzib have produced excellent examples of figurines in the round with frame drums and double pipes. Although the archaeological data and a host of figurines indicate that women played the frame drum primarily, men played this instrument as well. Plaque figurines with frame drums have been discovered at Tel Tanaach and Megiddo.

There are questions regarding the involvement of women and musical performance in the Israelite temple. For instance, the Chronicler states after listing the family members of Heman the seer:

All of these were the sons of Heman the king's seer, according to the promise of God to exalt him; for God had given Heman fourteen sons and three daughters. They were all under the direction of their father for the music in the house of the LORD with cymbals, harps, and lyres for the service of the house of God. Asaph, Jeduthun, and Heman were under the order of the king.

This passage suggests that the daughters of Heman along with the men were involved in temple musical performance. There is also a psalmist's description: “Your solemn processions are seen, O god. The processions of my God, my King, into the sanctuary – the singers in front, the musicians last, between them girls playing frame drums” (Ps. 68:24–5).

Early Israelite culture and musical performance

Music and musical instruments were a part of important decisions and actions in Israelite culture. After the Israelites escape from Egypt, Moses is scheduled to speak with the deity of Israel on Mt. Sinai (Ex. 19:1–19). The deity and Moses converse in the midst of smoke that engulfs the mountain. While they are together, someone sounds a trumpet or shofar or ram's horn, often translated as “trumpet,” possibly indicating the god's presence. The writers describe a similar instance with two priests as trumpeters, Benaiah and Jahaziel. David instructs them to blow their trumpets continuously before the Ark of the Covenant, an act that may let the people know the deity was among them.

The Israelites used the trumpet as a signal to act, move, assemble, or disperse. In the destruction of Jericho, the Israelites have the task of taking the major city that is surrounded by a massive wall. Instead of brute force, the people march around the city seven times, and on the seventh they blow trumpets and shout. The wall falls flat, and they are able to take the city and destroy its inhabitants. The people listen the sound of the trumpet as an indicator of battle and act accordingly (Numbers 9:10). The prophet Jeremiah exemplifies this: “for I hear the sound of the trumpet, the alarm for war” (Jeremiah 4:19).

Music was also a means to inquire and comprehend the will of the deity, particularly in prophesy. When King Jehoshaphat requests divine instruction from the deity by way of prophet Elisha, the prophet says, “get me a musician” (2 Kings 3:15). As the musician plays, he makes a connection with the deity to reveal the prophecy. The writers do not indicate what kind of instrument was involved, but the musician plays to aid the prophet. Note that in this instance, the prophet is an active participant, one who seeks the will of the deity, using music to achieve a certain elevated or enhanced state. According to the text, there may have been times when bystanders became passive participants in prophetic activity that involved music. This happens to King Saul. As he and Samuel are speaking, a band of musicians (lyre, harp, frame drum, cymbals, and pipe) are coming down from the high place. The prophets are in a prophetic frenzy from the deity. Samuel tells Saul that he will soon be caught up in the frenzy with them. As the musicians and prophets pass, Saul is pulled to their group, which causes people to ask, “Is Saul also among the prophets?” (1 Sam. 10:5–11).

The Israelites treated illnesses with the sounds of music. At the beginning of his downfall, Saul, Israel's first king, receives an evil spirit from the deity, which torments him with psychotic problems and causes him to act violently. His servants enlist the musical services of David the lyre player. The young musician temporarily relieves Saul's illness with his skillful lyre playing (1 Sam. 19:9).

Music was a part of birth and death in Israel. Specific songs sung at or during the birthing process are not in the text, but a child entering the world would have been welcomed and serenaded at some point by music. It is also clear that music was part of death. Wailing was a part of the grieving process, as specific individuals sang wails and laments for the deceased (Judges 11:40; 2 Chron. 35:25). It is not clear whether instruments other than the voice were used in singing laments, but both men and women sang them in Israelite culture (2 Chron. 35:25).

Ideas about the sound of music in Ancient Israel

The most perplexing enigma regarding music in early Israel is the question: What did the music sound like? An accurate answer to this query would be a priceless discovery, but finding such a thing is highly unlikely. First, there is no concrete reference point regarding how the music of antiquity sounded. Second, how will we know when or if we have achieved it? Unfortunately, there are a host of subtleties that are unrecoverable. This is one of the issues that comes with studying the past. Voices, some colors, tastes, smells, and sounds are essential but fragile parts of life that do not survive in the archaeological record and critical details about them cannot be found in ancient texts. While it is an asset to have artifacts and ancient texts, we have to remember that we were not the intended audience and writers were not writing for posterity. Thus, how these objects are used in the study of the past is crucial and will affect the questions we ask as well as the outcomes of the research.

When it comes to the sounds of the music of early Israel, we can say conclusively that musicians used many types of instruments. Employing our present knowledge, we can explore ideas regarding the sounds created through reconstructions, virtual instruments, and other means. Yet matters such as the different colors a player may have been able to produce on a lyre or harp with different strings or plectrums, or the sounds of instruments made from various woods, the timbres of drums with skins from different animals, and their thickness and other variable attributes, remain elusive. These types of subtleties make music come alive. It tells us about preferences and likes and dislikes within the culture. When we hear singers and musicians today in most genres, we can detect so much information from their voices and their color, depth, vibrato, and strength. These characteristics were present in antiquity, but sadly are now lost to us. Even with all of the technical information we can derive from the text and archaeology, we are limited in our attempts to reproduce such an organic artistry from the past.

Although these obstacles are indelible in the study of how early Israelite music may have sounded, a number of groups have offered unique ideas and interpretations in the ancient Near East in general and Israel in particular. Many of these are well-researched and excellent productions. One of the earliest works is the album entitled Sounds from Silence.3 Anne Kilmer and her team recorded information regarding Babylonian chordophone tunings and a musical interpretation of a Hurrian Cult song. Kilmer sang this hymn with lyre accompaniment. Their musical ideas came from translations of mathematical and musical tablets.

Among the literature on the subject of early Israelite music is The Music of the Bible Revealed, by Suzanne Haïk-Vantoura, a world-renown organist and composer.4 Haïk-Vantoura presents the musical system called the te'amim, which allows one who understands the system to sing most of the Masoretic text (for further discussion, see Chapter 6 in this volume). She also completed recordings of the musical ideas she discusses. There are numerous questions and controversies regarding her work, as she was not a trained biblical scholar; however, she was a world-class musician who presents a thorough discussion of the system and very intriguing recordings of her ideas. Ancient texts and artifacts show the importance of music to the Israelites. This pervasive art form provides an insightful perspective about this enigmatic culture.

Introduction

The study of Jewish music is a challenging endeavor. One typically expects the liturgical music of a cultural group to be homogeneous and definable through melodic or rhythmic characteristics. But Jewish music is neither homogeneous nor definable. Due to the complex history of the Jewish people in the diaspora, Jewish music reflects a variety of contacts with local cultures throughout time. Therefore, the musical traits found in Jewish music are often characterized as adaptations of music from various local cultures, within a Jewish context. This is not to say that Jewish music is only made up of adapting music from other sources. Many genres, such as cantorial recitatives, Hasidic songs, klezmer repertories, Ladino songs, and piyyutim (the singing of religious poems), are unique to and centrally a part of Jewish culture. The fact that there is no universal feature to Jewish music does not diminish its value or importance. Rather, it is a reflection of the richness and development of Jewish musical culture. Jewish music needs to be considered within the context of the culture in which it is found, and situated within its place in history.

This chapter approaches the use of music in Jewish religious, liturgical, and paraliturgical situations (events for religious enrichment that are not mandated services). Both Ashkenazic and Sephardi/Mizrahi traditions are discussed in several geographic contexts.

Sources and challenges

The history of Jewish music is based upon a variety of sources: written, non-written, and oral. Each source provides a piece of a puzzle that creates an overall picture of Jewish music's past. The written sources include the Jewish textual tradition: Bible, midrash, Mishnah, Talmud, and responsa. These sources provide the primary basis from which to derive an understanding of the role of music during ancient, biblical, temple, and medieval Jewish life. Non-written sources include physical evidence of musical instruments found through archeological explorations. In addition, iconography (pictorial representations) from frescoes, mosaics, pottery decorations, and images on coins make up the many visual representations of music's use during the same early period of the written textual sources (ancient, biblical, and medieval times). Notated musical sources provide the most concrete record. Unfortunately, notation of Jewish music prior to 1700 is minimal, as only a few manuscripts are extant.1 The oral tradition provides the richest source of melodic materials. Several regional traditions are represented in Abraham Zvi Idelsohn's monumental collection Thesaurus of Hebrew-Oriental Melodies, which was published in ten volumes between 1914 and 1932.2 The regions represented in this collection include Yemen, Iraq, Persia, Syria, the “Jerusalem-Sephardic” tradition,3 Morocco, eastern Europe, and central Europe. This collection provided the basis for study throughout the twentieth century. Present-day recordings of scholars and private collections from individuals and institutions have added a vast dimension available for examination.

Some scholars have tried to uncover the sound of Jewish music from antiquity. However, any attempt to connect modern practice with historic sources is wrought with dilemmas. For example, although rabbinic sources dating back two thousand years refer to the practice of the melodic recitation of the Bible, we still do not know the sound of that recitation. Some scholars imagine that Jews from Yemen have faithfully practiced their tradition of cantillation throughout this two-thousand-year period and insist that Yemenite biblical recitation in the twentieth century is an exact replication of the past.4 Such claims are without merit. They are based on conjecture and are not provable.

An ongoing question that needs to be addressed involves the usefulness of contemporary oral traditions to understanding music of the past.5 To what extent do present Ashkenazic and Sephardic traditions represent the continuation of oral traditions rooted in the past or the establishment of new practices? Each situation must be considered on its own merits. Today, ethnomusicology, the academic discipline that seeks to explore music and culture, stresses the in-depth understanding and unraveling of the complexities of a single tradition rather than trying to postulate broad, and often unprovable, theories about the universal nature of music in various cultures or across time. Documentation of an oral tradition should be placed in perspective and any attempts to project the antiquity of an oral musical tradition should be carefully considered.

History

I Contexts of music in the Bible and Temple

There are hundreds of references to music in the Bible and rabbinic sources related to the Temple in Jerusalem. The biblical references discussed below provide a few examples (for further discussion, see Chapter 5 in this volume). Events that refer to music include miraculous moments where God's power is praised and exalted, for example Moses's and Miriam's songs after the Egyptians were destroyed in the Red Sea (Exodus 15:1–18, 21). Important events accompanied by musical instruments include the transport of the ark to Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6:5; 1 Chronicles 13:8), the establishment and reconstitution of the Temple service (2 Kings 12:14; 1 Chron. 15:16–28), and the anointment of kings (1 Sam. 10:5; 1 Kings 1:34, 19–41; 2 Kings 11:14). Music's role in prophecy is deduced from David's playing of the harp, which cured Saul's depression (1 Sam. 16:14–23). Biblical passages also mention mourning (1 Kings 13:30; Jeremiah 48:36), newly composed laments by men and women (2 Chron. 35:25), and the ceasing of music after the destruction of the Temple (Lamentation 5:14; for a discussion in the Mishnah see Shabbat 23:4; Baba Metzia 6:1; Ketubot 4:4; Moed Katan 3:8). Other contexts of music include entertainment for the rich and the kings’ courts (2 Sam. 19:36; Amos 6:5; Ecclesiastes 2:8), the inclusion of bells on the tunic of the high priest (Ex. 28:33–4, 39:25–6), and farewell ceremonies (Genesis 31:27). Although these and other references mention music, no specific detail is given about the type of music or its sound.

Music's role in the Temple is discussed in rabbinic literature as well. Surprisingly, no description of music's use for the avodah (worship or Temple sacrifice) is given in the Bible. Statements can be made concerning the following aspects of music in the Temple: instrumental and vocal practices, music's role in the service, and the application of the psalms. Instrumental playing and vocal singing constituted the medium of music in the Temple. The Bible names King David's chief musician as Asaph (1 Chron. 16:5). Many references are given to the number and type of instruments and voices used in the service (Arachin 2:3–6). The instruments can be divided into three categories: percussion, wind, and string. The one percussion instrument used was the tsiltselim (a pair of cymbals). The tof (drum) was not played in the Temple, most likely due to its use during noisy celebratory purposes.6 The wind instruments include the shofar and ḥatsotserah (trumpet) to signal events. The ḥalil (flute) was also used but restricted to the twelve festal days (Ar. 2:3). The ugav (reed pipe), mentioned in Genesis 4:21, was not played in the Temple, perhaps due to the plethora of post-biblical references to the use of the ugav for ritually unclean purposes. String instruments include the kinnor and the nevel. Both are forms of lyre, with strings fastened to a frame, and most likely originated in Asia Minor. The nevel was the larger of the two, with a deeper tone,7 and the kinnor was considered more regal because it was played by David (1 Sam. 16:23, 18:10, 19:9). The singers of the Temple were the Levites. During the Temple services this included adults between the ages of thirty and fifty, and young boys who added “sweetness” (Ar. 2:6). It is unclear if the Levites sang with the instruments or if they sang a cappella. Discussion is given to the training of Temple singers (Hullin 24a), vocal tricks (Yoma 3:11), and responsorial singing style (Sotah 5:4, B. 30b; Sukkah 3:11, B. 38b). The rabbinic sources for the Temple service dictate a minimum of twelve instruments for a regular weekday service: two nevel, nine kinnor, and one cymbal. This was matched by a minimum of twelve Levitical singers; the balance of instruments to singers was intentional (Ar. 2: 3–6).

The Mishnah Tamid (chapters 5–7) illustrates music's use within the service. After opening benedictions from the priests, sacrifices were offered. The magrepha (a large rake used for clearing the ashes) was thrown forcefully to the ground to summon other priests and Levites into the Temple, and ritually unclean members were sent to the east gate. Two priests stood by the altar and blew trumpets with the sounds of tekiah, teruah, and tekiah (tekiah is a single deep, sustained blast; teruah consists of nine short notes). The priests stood on both sides of the cymbal player, who sounded the instrument after the trumpet blasts. The Levites next sang a text from the Psalms. The trumpet blowing was then repeated, participants prostrated themselves, and the Levites continued singing. The psalm texts of the daily singing are indicated in Tamid 7:4. A psalm's incipit (introductory line) can provide a possible clue to the use of that psalm within the service, and may also offer evidence of melodic description, direction or place of use, and performance practice. Melodic description includes psalms beginning with indications of a song of a particular person or group, for example Korah (Psalm 87) and Asaph (Ps. 77); a style of performance in the melodic scale al ha-sheminit (Pss. 6, 12), or the use of an instrument such as nehilot (flute) (Ps. 5), shigayon (Ps. 7), gitit (Pss. 8 and 81), or alamot (Ps. 46);8 and cue words of a known song, such as “Ayelet ha-shaḥar” (The Hind of the Dawn) (Ps. 22) or “Shoshanim” (Roses) (Pss. 45, 80). The issue of the performance practice of psalms is inferred from the portions of psalm texts that indicate a specific use, such as responsorial psalmody (leader-group alternation), as seen in the verse parallelism of Psalm 47, the antiphonal psalmody (alternation between two groups) suggested in certain passages (see Ps. 103 verses 20–2), and the litanies with repeated refrains such as Psalm 80 verses 4, 8, and 20. The 150 psalm texts are a rich source of material awaiting further analysis to reveal more about music's role in the Temple.9

II Development of liturgy and the ḥazzan

Music's role in liturgy was developed during the same period of time as the canonization of the liturgy text (between 100 and 1000 CE). After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE the focus of Jewish ritual practices shifted to the synagogue. Even during the latter period of the Second Temple synagogue rituals had begun to develop, and the practice intensified after the Temple's destruction. The recitation of the liturgical text replaced the requirement for ritual sacrifices. The primary canonization of the text of the liturgy was a process that developed between the eighth and eleventh centuries CE. The earliest compilation of prayer, known as Seder Rav Amram, dates to the ninth century, and includes biblical (particularly psalmodic), rabbinic, and poetic texts.

Passages drawn from the Bible and rabbinical prayers encompass the core of Jewish liturgy. Two portions of the morning service, the Shema and the Amidah, and the prayers of their environs are mandatory according to Jewish Law. The Shema, taken from three biblical passages (Deuteronomy 6:4–9, 11:13–21; Numbers 15:37–41), is the creed affirming the unity of one God. The Amidah is said in place of the daily sacrifices once performed in the Temple; this text evolved slowly and was defined, as it is known today, in the seventh century CE.

In general, the history of Jewish liturgy is divided into two rites: Ashkenazic and Sephardic.10 The major distinguishing features between the two rites entail small changes in the order of the prayers and in the inclusion or exclusion of psalms and liturgical poems. The statutory prayers of the two major rites are the same, with only slight differences in wording. The Sephardic rite, a development originally from Spain, influenced the local rites of those European and Middle Eastern communities that received an influx of Spanish Jews after the expulsion from Spain in the sixteenth century.

Prior to the circulation of known settings of liturgical texts in the seventh century and thereafter, the non-statutory positions of the liturgy were textually improvised. Presumably the melodic recitation was also improvised. It was the task of the ḥazzan to create texts spontaneously. The term ḥazzan is presently applied to the leader of the prayers. The term first appeared in Mishnah sources and was used variously to indicate the teacher of children (Shabbath 1:3), the superintendent of prayer (Yoma 7:1, Sot. 7:8), and the one who announces the order of the proceedings (y. Berakoth 4:7d). Some speculate that the term ḥazzan comes from the word ḥarzan (to versify).11 It was not until the ninth century that the ḥazzan became the religious officiant who led prayers. Interestingly, the role of the office of the ḥazzan was standardized at the same time that the liturgical text was codified (the eighth to eleventh centuries). Thus, the musical expression of the liturgy grew out of liturgical need, function, and aesthetics.

Three musical types in the reading of sacred texts

Cantillation, psalmody, and liturgical chant are liturgical musical practices formed in the medieval period. Cantillation refers to the melodic recitation of biblical texts during the service. Psalmody refers to the practice of reciting psalm texts within the liturgy that could include a single text or a grouping of multiple texts. Liturgical chant encompasses a broad range of melodic styles set to the non-biblical portions of the liturgy. The melodic styles mentioned here include rhythmic and non-rhythmic melodies. Later generations built upon these three types in culturally specific musical styles.

I Cantillation: Recitation of Torah

Biblical cantillation occurs whenever the Bible is read publicly. The indication that the Bible was read publicly is inferred from Deuteronomy 31:12: “Gather the people – men, women, children, and the strangers in your communities – that they may hear and so learn to revere the Lord your God and to observe faithfully every word of this Teaching.” The yearly cycle of the biblical reading begins on the Sabbath following the Simchat Torah holiday. The process of cantillation was formalized into a system by Aaron Ben Moses Ben Asher during 900–30 CE. Ben Asher lived in Tiber and his system of cantillation symbols, te'amei ha'mikrah, is referred to as the “Ben Asher” or “Tiberian” system. These signs (te'amim), placed above or below the biblical text, were intended to provide grammatical indications for proper syntax and sentence division. The shapes of the signs indicate grammatical or musical function, visual representations of melodic contour, or the shapes of hand signs used to indicate the melody.12 This later practice of hand signals is mentioned in the Gemara (Ber. 62a), and Rashi comments that even in his time, the eleventh century, the practice remained in effect. The practice is still found in some Yemenite communities.

Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities differ in their melodic interpretation of these cantillation symbols. The shape of the sign does not determine a fixed pitch or melodic phrase. Avigdor Herzog defines five regional styles in cantillation: Yemenite, Ashkenazic, Middle Eastern, North African, Jerusalem-Sephardic, and North Mediterranean.13 Some traditions supply the specific melodic unit for each sign, while others use larger melodic units for a phrase. The Yemenite, Middle Eastern, North African, and Jerusalem-Sephardic are more recitative in style and some follow an Arabic maqām (mode) and are not in a Western scale. The Ashkenazic and North Mediterranean have the broadest melodic contours and most commonly have a different musical phrase for each melodic sign.

II Nusaḥ

Psalmody is the practice of melodically rendering psalm texts mostly used within the introductory part of the liturgy. The melodies are known as pesuke dezimrah in Ashkenazic liturgy and zemirot in Sephardic liturgy for the Sabbath morning service. Typically, psalm chanting consists of an introductory phrase, a medial recitation note, and a final phrase. The use of psalms in Christian liturgy led many scholars to believe that the early music of the church based itself on Jewish models.14 Eric Werner expounded upon this topic in his seminal work The Sacred Bridge.15 Werner's conclusions have been the subject of greater scrutiny by chant scholars who see his work as speculative.16 Several attempts have been made to note the similarities of Jewish and Christian traditions without specific focus on the uncertain origins of these practices, due to the lack of sufficient evidence.17

The mainstay of Ashkenazic liturgy is made up of the Jewish prayer modes, referred to as nusaḥ.18 The prayer modes operate like other musical modes, which are defined by two parameters: scalar definition and a stock of melodies variously applied. The number of modes used in the Jewish tradition is a matter of scholarly debate.19 The generally accepted practice today that is a part of the pedagogy in American cantorial schools is the adoption of three prayer modes, named HaShem Malakh (The Lord Reigns), Magen Avot (Shield of Our Fathers), and Ahavah Rabbah (Great Love).20 The name of each prayer mode is taken from the opening words of the liturgical passage that marks one of the first usages of that particular mode in the Sabbath liturgy. Hence, music and text are closely associated.

The HaShem Malakh mode is similar intervallically to the Western major scale, but with a lowered seventh scale degree (Example 6.1). In most instances the four lowest notes (or tetrachord) of a melody's scale pattern determine a Jewish prayer mode. As the ḥazzan continues reciting Kabbalat Shabbat, the HaShem Malakh prayer mode is developed. An additional feature of the musical modes is an affective association, and grandeur and God's strength are connotations of the HaShem Malakh.

Example 6.1 HaShem Malakh mode.

Magen Avot has intervallic similarity to the Western minor scale (Example 6.2). Recited towards the end of the Friday evening Sabbath prayer, the text of Magen Avot refers to the forefathers guarding the Sabbath. The mode is also heard in cantor's prayers on the Sabbath morning service, in the setting of the text Shokhen Ad Maron (He Who Dwells Forever). The typical ending of this mode emphasizes the fourth and final notes of the mode (F to C). Magen Avot is known as the didactic mode because it is used for extended declamations of text and does not make use of melodic elaboration.

Example 6.2 Magen Avot mode.

Ahavah Rabbah has often been called the most “Jewish” of the Jewish Prayer modes, because of its distinctive sound. The essential feature is the augmented second interval between the second and third notes of the mode (Example 6.3). There is no Western equivalent to this mode. The broad augmented second is produced by the lowering of the second scale degree (here, from D, as it appears in HaShem Malakh and Magen Avot, to Db) while the third scale degree remains in place (here, on E). Expressive liturgical texts use this mode. The common example is heard on the Shabbat morning in the setting of the text Tsur Yisrael (Rock of Israel) that precedes the Amidah. Ahavah Rabbah means “great love,” aptly reflecting the affective association of this mode, which musically expresses the “great love” for God through a unique musical sound.

Example 6.3 Ahavah Rabbah mode.

In other sections of the cantor's recitation of prayers, all three Jewish prayer modes are used. The differing quality of each mode expresses the unique subtleties of the text. This modal modulation helps to heighten the meaning of the text through emotional expression associated with the use of the nusaḥ. The three modes are used to express the text of the Sabbath morning Kedushah, recited during the ḥazzan's repetition of the Amidah, making it an important liturgical highlight. Ashkenazic liturgical music without harmony, performed by solo voice, demonstrates how the Jewish prayer modes aptly express the meaning of the text and provide a symbolic commentary. Ḥazzanut (the cantorial repertoire) is filled with intricate details combining textual and musical meaning.

III Liturgical chant

As the ḥazzan's role became formalized with the development of the liturgy, so too did the liturgical chant. It is important to view the standardization of the texts, the need for the ḥazzan, and the growth of liturgical chant as coterminous, because they were simultaneous developments. The ḥazzan became the prayer leader for the congregation, known as sheliaḥ tsibur in Hebrew, who facilitated the prayers through musical recitation. This role was established during the eighth to tenth centuries CE. Musical developments kept pace with textual innovations, although we know more about the latter than the former. The development of the piyyut during this period saw the growth of new poetic forms to include the use of rhyme and meter. Music served as a means to express the text.

Attitudes about music began to change. Although there is quite limited musical notation from the year 1000 to 1750, we do know from written evidence that ḥazzanim and community members wanted to create new tunes while others, most notably rabbis, desired the preservation of older tunes, presumably to slow the rate of continued influence from surrounding non-Jewish musical practices. Cantors were known by name for the individual musical personalities that they brought to their musical recitation of prayers, and in some communities composers of music were identifiable.

Liturgical melodies in the Ashkenazic practice can be divided into two categories: Mi-Sinai nigunim (melodies from Mount Sinai) and metrical tunes. These two categories contain known melodies that are sung by the ḥazzan, the congregation, or both, and are associated with particular liturgical sections at specific times during the calendar year. The Mi-Sinai nigunim represent the oldest body of melodies in the Ashkenazic tradition and encompass the recurrent melodies of the High Holidays and the Three Festivals. No collection or tabulation of all the melodies exists. The term Mi-Sinai nigunim is not fully understood by cantors. Many have noted the similarity to the phrase “halakhah le-Moshe mi-Sinai” (a law given to Moses at Mount Sinai); in Talmudic discourse this phrase is used to denote a law put into Jewish practice with no originating biblical source. Hanoch Avenary has stated that the present musical application of the term Mi-Sinai nigunim is attributed to Abraham Zvi Idelsohn.21 Mi-Sinai nigunim differ from Jewish prayer modes in that the former comprise set tunes of greater length whereas the latter are shorter musical fragments. Both musical types are similar in that they flexibly apply the melody or melodic fragment to the text. There is no exact correspondence between text and melody, so interpretations vary.

Ashkenazic tradition

I Pre-modern practices

During various periods preceding the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), different communities sought unique musical innovations in Jewish prayer. Most noteworthy are the Italian Jewish composers of the early seventeenth century and the Amsterdam composers of the early eighteenth century. These two communities provide the first examples of metrical tunes. Leon Modena (1571–1648), a rabbi in Ferrara, sought to reestablish artistic beauty in the synagogue, fueled by his enthusiasm for the ancient Temple music, and he supported a number of musical innovations. In 1605, for example, eight singers in the synagogue performed polyphonic (multi-voiced) music, a style that was contemporary for his time. The best-known composer of Jewish religious music during this era was Salamone Rossi (c. 1570–c. 1630), whose synagogue composition Ha-shirim asher lishlomo (Venice, 1622–3) displays the High Renaissance musical style (see Chapter 9). Rossi interweaves polyphonic musical lines with block chords in a manner similar to that found in the works of Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1554–1612). The composers of music for Jewish occasions in Amsterdam, principally Christian Joseph Lidarti (1730–after 1793) and Abraham Caceres (Casseres, fl. early eighteenth century), were not Jewish. Although the development of Jewish music in Italy and Amsterdam during these eras was short-lived and the repertoire was not maintained in the tradition, the music shows the desire of those in Jewish religious circles to engage in the creation and performance of artistic music like that of their Christian contemporaries. Later generations continued to draw from the outside as a basis for innovation in synagogue music, and this music reached new heights.

II The early Haskalah

Ideological proponents of the Haskalah, who resided in large central European cities, sought to integrate the totality of Judaism (philosophy, culture, and religious practice) into the Western sphere of knowledge. Opponents favored an inward approach to Judaism seeking to solidify traditional Jewish practices with greater intensity. Musical practices, likewise, reflected a desire for incorporating external influence while, at the same time, keeping elements of traditional Jewish music, such as the Mi-Sinai nigunim. Synagogue compositions of this period added Baroque-like musical interludes to traditional melodies. These interludes were excesses and can be seen as an elaboration of the meshorerim practice – in which two assistants, a boy soprano and a male bass, traveled and sang with the cantor – with each of the three participants given an opportunity for melodic embellishments. Most often the boy soprano and bass were given this role in the interludes. An important individual who sought to incorporate secular musical practices was Israel Levy (1773–1832), also known by the last name Lowy and Lovy in France. Synagogue music gradually grew to include occasional harmonizations, and finally choral settings. Choral music for the synagogue originated in Italy and France and later moved into Germany, where it spread quickly.

During this time Hasidim sought spiritual beauty not through culturally elite practices but through ecstatic experience intent on elevating the soul. Hasidic music also borrowed from its cultural surroundings, incorporating folk tunes and many other sources, but artistry was not the goal. For Hasidim, singing in the synagogue, at home, and at other occasions offered opportunities to engage in a deeper commitment to Judaism.

III Central European cantorial and synagogue music

The most significant development in central European cantorial and synagogue music resulted from the liturgical and aesthetic changes of the Reform movement (see Chapter 12). Although changes in various central European cities began in the late 1700s and early 1800s, reform did not take shape in an established fashion until the mid-nineteenth century. Israel Jacobson (1768–1829), a merchant by profession, initiated various changes to the synagogue service. These included the elimination of the ḥazzan, the use of Protestant hymns with Hebrew words, sermons in German, confirmation for boys and girls, and the reading, not cantillation, of the Bible. With the exception of the elimination of the ḥazzan, most of Jacobson's changes were incorporated into the Reform service later in the nineteenth century and thereafter. Many congregations replaced traditional Jewish music with hymnal singing in the Protestant style and in some cases literally supplanted known German Protestant hymns with Hebrew words. Jacobson introduced the first organ in Seesen in 1810. These reforms were initially seen as too drastic and later further developed with the central European cantorial style of Salomon Sulzer (1804–90) who from 1926 officiated at the New Synagogue in Vienna. Further developments took shape in the work of synagogue composer Louis Lewandowski (1821–94). Together with Samuel Naumbourg (1815–80), Lewandowski had a significant impact on central European synagogue music. Eastern European cantors also developed synagogue music from the nineteenth into the twentieth century. This includes the work of Nissan Blumenthal (1805–1903), Abraham Baer Birnbaum (1864–1922), and Eliezer Gerovich (1844–1913), a student of Blumenthal. Where the central European cantors were more innovative using secular musical styles of the Classical and early Romantic eras, the eastern European cantors retained modal influences of nusaḥ with modal harmonization. The eastern European synagogue tradition can also be distinguished from the central European tradition by the use of more vocal embellishments.

American Reform synagogues in the nineteenth century drew on the work of contemporary European composers, predominantly Sulzer and Lewandowski, as well as of American composers. Nineteenth-century American synagogue innovators included Sigmund Schlesinger (1835–1906) and Edward Stark (1863–1918), whose music was devoid of traditional prayer modes. An organist at a synagogue in Mobile, Alabama, Schlesinger set texts for the synagogue service to operatic excerpts from Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini. Stark, a cantor at Temple Emanuel in San Francisco, used some traditional melodies. The Hungarian-born Alois Kaiser (1840–1908), an apprentice to Sulzer who had performed stints in Vienna (1859–63) and Prague (1863–6), immigrated to Baltimore, where he served as cantor to Congregation Ohab Shalom. His collections of synagogue music include hymnal compositions, melodies with four-part chorale settings following the Lutheran model of J. S. Bach.

These cantors and composers, though largely forgotten today, were instrumental in the emergence of Minhag America, a term coined by Isaac Mayer Wise, the mid-nineteenth-century progenitor of American Reform Judaism, to refer to a new and specifically American form of Jewish tradition. Originally the title of a prayerbook in 1856, Minhag America has been adopted more generally to refer to the Americanization of European Jewish traditions. Convinced that the communal singing of hymns was the quintessential religious experience, the Central Conference of American Rabbis resolved in 1892 to adopt Wise's publication as the official hymnbook of American Jewish Reform Congregations. Abraham W. Binder (1895–1966), professor of Jewish liturgical music at Hebrew Union College and founder of the Jewish Music Forum, became the editor of the third edition of the hymnal, which appeared in 1932. Although a part of many Reform congregations through the 1950s, hymn singing eventually fell out of fashion. The new approach in America was to write in a more modern idiom while still retaining elements from the past. Binder championed this approach, found in some of his liturgical settings for the Friday night service and Three Festivals. He also encouraged other aspiring composers in America to apply their talents to the synagogue. These included Herbert Fromm (1905–55) and Isadore Freed (1900–60). Freed was trained in America but spent some time studying in Europe, including as a composition pupil of Ernest Bloch (1880–1959), whose own major contribution to synagogue music, the Sacred Service (1933), was a monumental work for cantor, choir, orchestra, and narrator. The Sacred Service showed the most advanced musical styling in composition for the synagogue, inspiring synagogue composers for decades.

Music in Sephardic liturgy

Due to the diversity of Sephardic liturgical music, its study presents significant difficulties. The problem is compounded when one considers that the Sephardic practices are still maintained orally and only a limited amount of the repertoire has been notated and collected. In addition, Sephardic liturgical music has not received the same amount of study as Ashkenazic liturgical music and, hence, the research to draw upon is limited.

One other point deserves discussion. The term “Sephardic” has been variously understood in Judaic studies. The word Sepharad appears in the Bible in Obadiah 1:20 and is thought to refer to the Iberian Peninsula. The term “Sephardic” refers to Spanish Jews and their descendants in various points of relocation. Use of the term becomes problematic when these descendants relocated to other existing communities. In some cases the Spanish Jewish traditions replaced existing practices, while over time these immigrant Jews intermixed with the local Jewish culture. Through the remainder of this entry the term “Sephardic” may be better understood to refer to non-Ashkenazic Jews, as Sephardic Jewry has never been a single community that has remained unchanged over time.

I Influences of Arabic music and poetry

Arabic culture richly influenced medieval Jewish life in Spain, most significantly during the Spanish Golden Age (the eleventh to thirteenth centuries), a period in which Jewish culture flourished in an unprecedented way. Every dimension of Jewish religious and cultural life during this time drew from free interaction with non-Jewish cultures, which provided a fertile source of traditions that could be adapted for Jewish purposes.

Most notably, theoretical writings on the nature of music had a lasting influence on the manner in which music was viewed. Islamic scholars followed the ancient Greeks in conceiving of musical phenomena namely through acoustics and other abstract principles. In his Emunot ve-Deot (Beliefs and Opinions), from 933, Saadiah Goan wrote that there are eight types of musical rhythm that affect the human temper and mood. Similar concepts can be found in the works of Arabic writers on music including Al-Kindi (died c. 874). Other Jewish writers applied Saadiah's ideas to overlapping musical and moral phenomena and biblical events such as David's harp playing for Saul. In such ways, the discussion on the nature of music by Arabic music theorists was fused with Jewish concepts.

An area of innovation that significantly impacted music was the creation of liturgical poetry, the piyyutim. Arabic poetry increased in prominence through new rhyme schemes and a consistent use of meter. Hebrew poetry was likewise influenced through the poetry of Dunsah Labrat (tenth century) and others. After the 1492 expulsion from Spain, descendants of this rich tradition brought these cultural processes of creation with them. One significant figure was Israel Najara (1550–1620), who created new Jewish songs by replacing the lyrics of Turkish, Arabic, Spanish, and Greek songs with Hebrew. In this process of adaptation some of the sounds or assonances of the text were incorporated into his Hebrew poetry. The melody was often adapted to fit this new text. Thus, Sephardic music, both past and present, is comprised of adaptation. The adaptation of thought in theoretical writings about music parallels the adaptation of music and text found in the piyyutim. The wealth of Sephardic musical material to study is taken from the piyyut and paraliturgical traditions. The few purely liturgical sources have only been available recently due to new ethnographic studies.

II Musical influences and major regional styles

The discernable musical styles of Sephardic cantillation, liturgical prayers, and piyyutim can be classified according to four geographic regions: Spanish and Portuguese, Moroccan, Edot hamizraḥ (Middle Eastern or Arabic), and Yemenite.22 The first two of these styles are more Westernized than the others. Spanish and Portuguese descendants who traveled to Western Europe, England, and Amsterdam, as well as the Americas, both North and South, brought their traditions with them and began to adapt them in their new homes. Moroccan Jewry received a large number of Spanish Jewish refugees during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Jewish musical traditions from Morocco have been continually influenced by regional Spanish traditions such as Andalusian. The two other musical styles, Edot hamizraḥ and Yemenite, are marked by the influence of Arabic music. Spanish elements within these two traditions are faint or nonexistent. The Edot hamizraḥ include the Jews of the Levant (Syrian, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, and other neighboring locales). The Arabic modal system, known as maqāmāt, is deeply incorporated into their liturgical and paraliturgical practices. The Yemenite tradition also makes use of Arabic musical practices. Other traditions, such as Turkish, a practice that perpetuates Jewry from the Ottoman period, combine some of these styles. The geographic position between Morocco and the Middle East also characterizes Turkish Jewish music, which contains Spanish and Arabic elements.

The practice of lively congregational singing describes Sephardic liturgy. While many portions are recited by the ḥazzan as required by Jewish law, congregational participation is enthusiastic and joyful. Unlike the Ashkenazic practice, which intones the last two to three lines of a liturgical text, known as a hatima, Sephardic ḥazzanim recite the entire liturgical text out loud. Congregants may join in the recitation, and some do so in an undertone. The unique quality of the Sephardic tradition is displayed not only by the melodies they use, but also by the liturgical performance practice, which combines both active and passive participation from the congregation.

III Music in paraliturgical contexts

Many liturgical melodies are adaptations of melodies used elsewhere within each tradition. Most often the melodies are adapted from piyyutim. The venerable tradition initiated by Najara has been kept alive in Yemenite, Moroccan, Turkish, and Syrian communities up to the present. In many of these regions, Jewish practices involve adaptations of local melodies from the surrounding cultures. Only recently have the musical practices of piyyutim been studied.23 In many instances, liturgical melodies, following the past practices of Najara, were taken from known non-Jewish melodies, but these tunes became so popular that one finds their use in a variety of secular and religious contexts. In general, distinctions between sacred and secular use are arbitrary, since many melodies are used in both contexts.

The singing of piyyutim occurs mainly in celebrations of holiday and life-cycle events. Specific texts are associated with particular holidays and are sung in the synagogue or at home during meals. On some recurring paraliturgical occasions, the singing of piyyutim is the main source of the ritual. One such occasion, the baqqashot, or nuba in the Moroccan tradition, is practiced in some Syrian and Moroccan communities. Participants go to the synagogue at midnight or early in the morning before sunrise and sing supplications to elevate their spirits prior to the formal morning prayers.

A venerable tradition among Sephardic Jews, whose ancestry is from Spain, is their Ladino culture. The Judeo-Spanish written and spoken dialect of Jews of Spanish descent, Ladino represents the synthesis of Jewish and Spanish culture for Sephardic Jews (see Chapter 7). The rich tradition of this cultural interconnection from the Golden Age of Spain has continued. The amount of preservation versus new influence varies among Sephardic Jews over the past 500 years. The Spanish influence has been ongoing for Jews in Morocco, whereas Jews in Turkey and Greece have incorporated more Middle Eastern influence. Some historians hold that the venerable musical forms of these Sephardic Jews, namely the ballad and romancero, were time-honored traditions untouched by new cultural influence and thus faithfully transmitted. Modern scholars, however, have been unable to validate this claim.24 Nevertheless, Ladino music has deep historic roots, and as with other forms of Jewish music, this musical tradition is both perpetuated and innovatively revitalized by modern performers.

Ladino music has long been conserved by women. In fact, many of the song texts of the romancero and ballad deal with women's experiences in life-cycle events, passionate or erotic courtly poetry, and epic tales or stories. Dirges related to the death of individuals in untimely and other circumstances are known as endechas. The coplas, short holiday songs, also complement the Ladino musical repertoire. The wedding context in particular has been a rich source of music for Sephardic women. The preparation of the bride for the mikva (ritual bath) prior to the wedding, the bride's dowry, and her relationship with her mother-in-law are some subjects of the texts of Ladino wedding songs.

Each performer has personalized the Ladino repertoire because no standard forms exist. Musicologist Israel Katz has devoted his scholarly efforts to understanding Ladino songs through viewing present manifestations of this tradition. He sees a distinction between two musical types with respect to the ballad. The Western Mediterranean, or Moroccan, Ladino singing style includes regular phrases and rhythms with few embellishments. Many performers of Judeo-Spanish music within this style incorporate Spanish and Moorish musical styles into their song renditions. The Eastern Mediterranean, or Turkish and Balkan, Ladino singing style includes more melodic embellishments in a freer and, often, less regular rhythm. Over time these two styles have merged.

The role of new music in modern synagogue life

The music of the American synagogue has undergone distinct changes in the last century. The present musical traditions of the synagogue can be seen as both a continuation of their European legacy and a reaction to influences from America culture. Although the seventeenth-century settlers in America were Sephardic, their influence was overshadowed by the European immigration of the nineteenth century. German Jews were the first to arrive after 1820. It was the mass migration of eastern European Jews in 1880 that led them to dominate American Judaism at the turn of the century. The predominant liturgical music during this immigrant period was known as the Golden Age of the Cantorate, which lasted from 1880 until around 1930, when it began to wane. Most of the cantors associated with the Golden Age were born and trained in eastern Europe and then came to America around the turn of the century through the 1930s. Some had regular pulpits for the entire year and others were only engaged for the High Holidays, when they commanded large salaries. Radio broadcasts, in addition to 78-rpm recordings and live concerts, proliferated this musical liturgical artistry. The discs provide a lasting record, freezing the sound of the Golden Age of the Cantorate for future generations. Great cantors of this period include Yossele Rosenblatt (1882–1933), Leib Glantz (1898–1964), Mordecai Hershman (1888–1940), Leibele Waldman (1907–69), Pierre Pinchik (1900–71), and Moshe Koussevitzky (1899–1966) and his brother David (1891–1985). So admired were these cantors that people came from long distances to hear them sing at concerts and services. The Golden Age of the Cantorate was a brief but significant period in the history of Jewish liturgical music that uniquely fused vocal artistry and impassioned prayer in a distinctive style that has become the definitive form of ḥazzanut.

As described above, the Reform movement that began in central Europe, and the music of Sulzer and Lewandowski, came to America and spread throughout the country. In the second quarter of the twentieth century, American composers sought to innovate the music of the synagogue according to contemporary styles. Musicians such as Binder, Freed, and Lazar Weiner (1897–1982) arranged traditional European melodies in accordance with the Jewish prayer modes, producing harmonies not typically found in Western music. Towards the middle of the twentieth century, two composers, Max Helfman (1901–63) and Max Janowski (1912–91), wrote compositions that have become standards for the High Holidays, Helfman's Sh'ma Koleinu (Hear Our Voice, Lord) and Janowski's Avinu Malkeinu (Our Father, Our King). During the second half of the twentieth century musical tastes have preferred more accessible music. In this context, Michael Isaacson adapts a variety of musical styles, both classical and contemporary, for his synagogue compositions. He and others also borrow from folk, popular, and Israeli-style songs. Cantors in Reform synagogues today draw from these diverse musical compositions encompassing the last 150 years, to provide interest and variety to their congregations.

The three denominations of American Judaism, Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox, deal with similar concerns with respect to new music in the synagogue. At issue are congregational involvement and the role of the cantor as prayer facilitator. The history of the rhythmically precise central European and the rhythmically free eastern European traditions have been combined in varying practices in American congregations. Where Reform synagogues were once the source of artistic innovation, the trend has diminished in favor of participatory services. Trained cantors and some congregants seek to draw from the rich musical history of the Jewish tradition. Other congregants desire a more accessible musical service that facilitates their participation in an idiom they prefer. Music within this sphere may draw from the Jewish tradition, including the use of Hasidic and Israeli melodies, but folk and popular styles are predominant. The songs of Debbie Friedman (1951–2011), whose popularity increased in the 1980s and 1990s, amply represent this trend.

The dynamics of the use of music in Conservative synagogues is similar. Traditional melodies may be more commonly heard in Conservative synagogues, but these melodies are less than one hundred years old. Abraham Goldfarb (1879–1956) arrived in the United States in 1893 from Poland and studied at the Jewish Theological Seminary. He produced many books and pamphlets of synagogue melodies that are regularly sung today in synagogues and at home rituals. The Havurah movement, begun in the 1970s, sought to empower laity to participate in services and further their education. The result has been an increase in congregational involvement throughout a service. The cantor often functions as an educator and facilitator of congregational participation. But, particularly on the High Holidays and for special events, the rich legacy of liturgical music can be heard combining the artistry of cantorial recitatives, taken from or inspired by the Golden Age of the Cantorate, in compositions based on the traditional use of prayer modes and liturgical chants. Volunteer and professional choirs are also used.

Within Orthodox synagogues music serves a more functional purpose. A paid professional cantor is rare in these synagogues, whereas it is much more common in Reform and Conservative synagogues. The prayer leader in an Orthodox synagogue assumes the role of baal tefilah, and vocal embellishments are kept to a minimum. Congregational involvement is interspersed throughout the service. Like in the other movements, traditional melodies are more commonly heard on the high holidays. In many Orthodox synagogues, a ḥazzan may only be employed during the holidays and on the other days of the year a congregant serves in this role. Orthodox congregations also differ in their incorporation of nusaḥ. Some prefer the use of Israeli melodies or tunes from songs popular in the community for the highlighted portions of the prayer such as the Kedushah in the Sabbath morning service.

While some are critical of the lack of artistry in the continual influence of popular genres on liturgical music, others embrace it as a way of encouraging synagogue attendance. The popular trends and changes reflect the influences and gradual adaptation of contemporary American cultural surroundings. The process of adapting musical influences has long been a part of Jewish synagogue music's history.

Prior to the formation of cantorial training programs after World War II, individuals learned ḥazzanut through apprenticeship and life experience, and many sang in synagogue choirs during their youth. The first program to be developed was the Reform movement's School of Sacred Music at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion New York Campus, founded in 1948. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, affiliated with the Conservative movement, opened its Cantors Institute in 1952. The Cantorial Training Institute at Yeshiva University began training cantors to serve Orthodox synagogues in 1964.

Other examples include a wide variety of folk and art contexts. Religious and secular summer camps and programs throughout the year make use of a wide variety of music to educate children and teenagers in Jewish concepts and religious practices. For nearly sixty years new religious music has been composed in Israel. The range of music includes children's songs, popular music, and folk songs associated with Zionist themes. Folk singer Naomi Shemer captivated the feeling of solidarity in the country and the enduring importance of Israel as the home of the Jewish people with her songs “Al kol eleh” (All These Things) and “Yerushalayim shel zahav” (Jerusalem of Gold). The synthesis of traditional Jewish musical styles and forms in both sacred and secular contexts, combined with a contemporary classical idiom, has been the goal of several noted composers in Israel (see Chapter 15). The most significant figure was Paul Ben-Haim (1897–1984) who drew from a wide variety of Jewish and non-Jewish musical styles. Many have debated the “Jewish” elements in Israeli music, raising the question whether Israeli music is a national or Jewish musical form. The same debate is cast in regards to American Jewish composers of note such as Leonard Bernstein (1918–90), whose “Jeremiah” (1942) and “Kaddish” (1963) Symphonies make use of Jewish themes but also seek acceptance as works of mainstream Western art music.

Many art music composers and popular songwriters seek the goal today that has long been a part of Jewish music history: to compose music that draws from the Jewish tradition and that respects the past and inspires one in the present to perpetuate Judaism.

Introduction

In trying to understand how the Sephardic musical repertoire was performed in the past, we must take into consideration the relationship of each song to two important defining parameters: genre and social function. This question arises in the study of the repertoire in the two main areas of the Sephardic diaspora, namely, the Eastern Mediterranean (the Ottoman area, later Turkey and the Balkan countries, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Greece) and the Western Mediterranean (Northern Morocco), as well as in Israel and the many places to which Sephardim later dispersed, and where the Judeo-Spanish musico-poetic repertoire has been maintained until the present day. The subject of the performance practices associated with Sephardic music involves both the traditional ways the repertoire was once performed, and the ongoing styles and techniques of its performance today.1

This chapter explores the songs that are either secular (non-religious in content) or paraliturgical (related to religious matters but with texts that are not in Hebrew but in Judeo-Spanish). The repertoire is predominantly vocal, sung in the Judeo-Spanish language, which is a Spanish dialect based on the language that the Jews spoke in Medieval Spain, where they had lived for many centuries before their final expulsion in 1492. The Judeo-Spanish language developed as its speakers borrowed from Hebrew and from the languages of their new surroundings. It flourished in two parallel dialects, one called “Judezmo” or “Ladino” in the Eastern area (with additions from Turkish, Greek, and Slavic languages), and the other called “Haketia” (with additions from Berber, Arabic, and Moroccan Arabic dialect) in the Western area.

In this chapter, we will consider the following questions in regard to the performance of Sephardic songs: What is the genre of the song? Who sings it, men or women? Where is it sung? When is it sung? And how is it sung, as a solo or in group singing, and with or without instrumental accompaniment? We will consider the function of examples from each genre in the lives of the individual and of the community, and as part of the repertoires of songs for the year cycle and for the life cycle.

Traditional performance

Modes of performance, as well as characteristics of text and music, differ in the cases of each of the Sephardic traditional genres, the romance, copla, and cantiga, collections of which are known as the romancero, coplas, and cancionero. These genres vary in: 1) their rendering, whether by solo or group; 2) the presence or absence of instrumental accompaniment; and 3) their gender definition, that is, whether they belong to the male or the female repertoire.2

I Romancero

The term “Romancero” means a collection or corpus of romances, which are narrative poems with a well-defined textual and musical structure.3 Their texts typically relate to the Spanish Middle Ages, involving kings, queens, princesses and galant knights, prisoners, and faithful (or unfaithful) wives. Other romances’ texts involve classical, historical, and even biblical themes.

Several old romances reflecting historical events have been forgotten in Spain but preserved in the oral tradition of the Sephardic Jews. One such romance relates the struggle between the children of King Fernando I of Castile and León (1016/18–65), Sancho, Alfonso, and Urraca: Sancho II from Castile puts his brother Alfonso (King of León) in prison, and his sister Urraca (of Zamora) intervenes to achieve Alfonso's freedom (Song 1).4

Romances are rendered as solo songs, with no instrumental accompaniment, and it is predominantly women who perform the repertoire and are responsible for its transmission. The music of the romances often has an ornamented melody and uses Eastern modes (the Arabic and Turkish makamat) that include microtonal intervals (narrower than the half-step) not found in the Western diatonic scale.

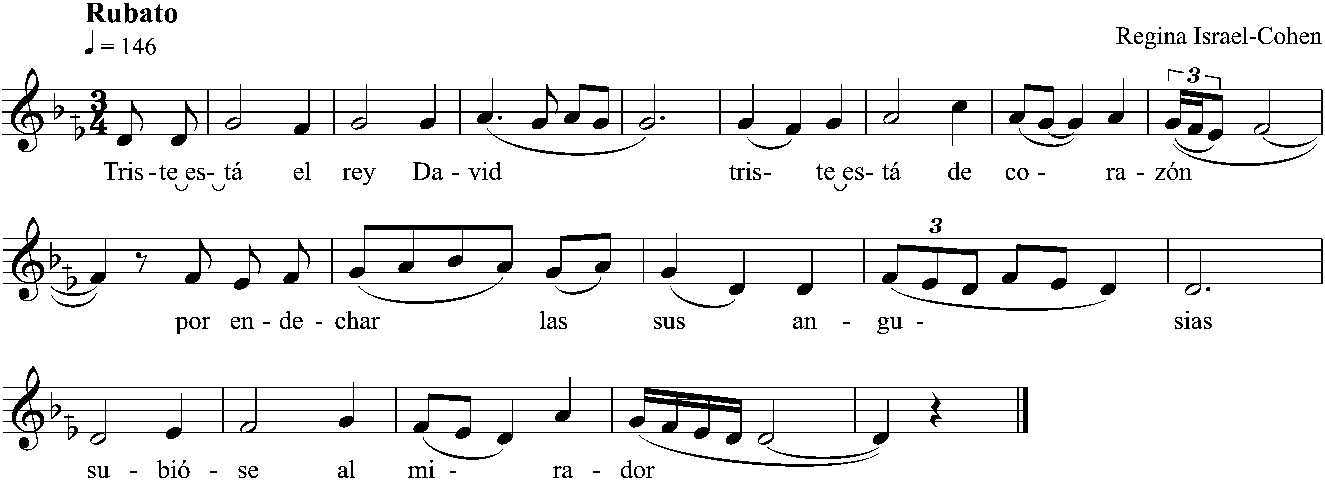

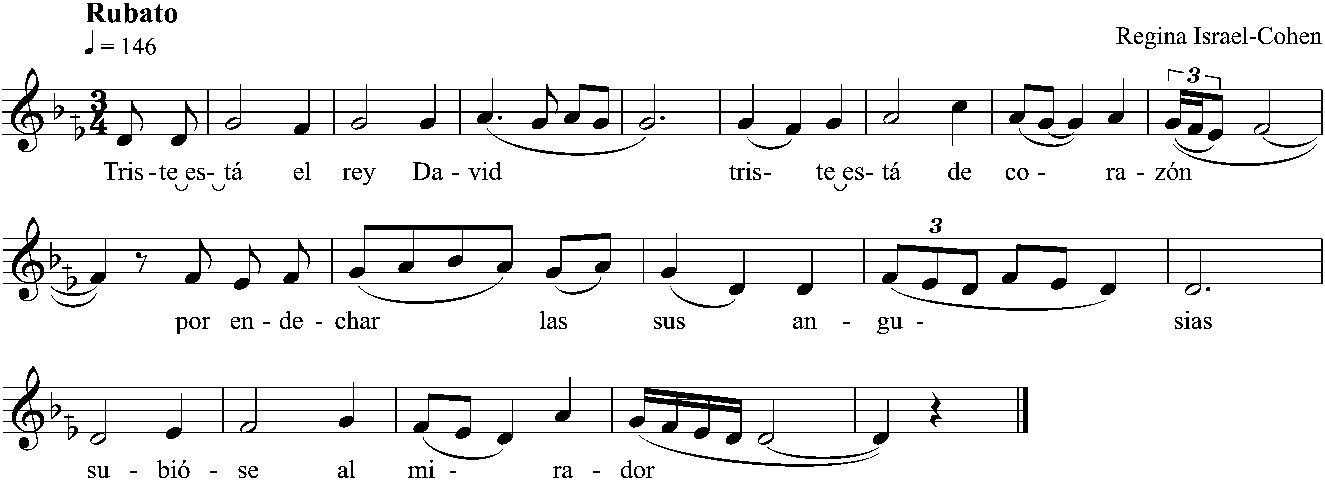

The next example, from Saloniki, Greece, has a melody in a free rhythm (without repeating accent patterns) built on a makam called Husseyni (with a lowered second degree), and features melismas (series of different pitches sung to a single syllable) at the end of each musical phrase (Song 2; Example 7.1). The romance tells the story of a fidelity test. A husband returns after many years away at war and asks a woman washing at a well for a cup of water; he asks why she is crying, and she explains that her husband has not returned from battle. She gives him her husband's description, after which he declares that her husband has died and told him to marry her. When she refuses, he reveals that he is her long-lost husband.6

Example 7.1 “The Husband's Return.”

The Romancero belongs to the women's repertoire, and its most common function is that of a lullaby, except in the case of a few romances that are included in the wedding repertoire, sung by groups and accompanied by percussion instruments. The previous example was a romance sung on the occasion of the preparations for the new couple, when the wool for the pillows and mattresses was washed by members of the community. The following song is also from the wedding repertoire, and its text relates the story of a married woman wooed by a young man who sends her love letters and presents, but she sends all of them back and remains true to her husband (Song 3). This narrative seems appropriate as advice for a bride. (Because the whole group sang it, men knew this song as well as women, as is evident from the name of the singer of this romance.) The romance closes by quoting a liturgical text with verses in Hebrew and their translation into Spanish.