By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion. There by the willows we hung up our harps…How could we sing the Lord's song on foreign soil?

For centuries, the musical soundscape of the Ashkenazi synagogue remained essentially insular. The core of the service was the “reading” of the Bible utilizing a set of fixed traditional cantillation motifs, performed modally and monophonically by a soloist in free rhythm. The rest of the service, the chanting of prayers, allowed for slightly more improvisation, but, like biblical cantillation, was based on traditional modes, in free rhythm, with no harmony or instrumental accompaniment.1 The emphasis was on piety rather than on beauty. At the same time, music in Catholic churches was evolving in a strikingly different direction, with the addition of new compositions by professional composers complementing the ancient chant, with harmony and counterpoint in performances by trained choirs, organists, and other instrumentalists.

Christians visiting synagogues were often puzzled by a music that seemed primitive, alien, even ugly in comparison with what they were used to hearing in church. The Frenchman François Tissard wrote of his experience visiting a synagogue in Ferrara, Italy, around 1502, “One might hear one man howling, another braying and another bellowing. Such a cacophony of discordant sounds do they make! Weighing this with the rest of their rites, I was almost brought to nausea.”2

The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Enlightenment (Haskalah) would bring tremendous changes to the synagogue ritual and its music. But several centuries before that, in the early modern era, there were a few isolated instances of musical innovation in Jewish worship, the most striking of which occurred in Mantua, Italy, at the end of the sixteenth century. Italy had a relatively large Jewish population, and was home to the oldest diaspora community in Europe. The original indigenous population had recently been enlarged by immigrations from Spain and from the lands of Ashkenaz. In the city of Mantua at the beginning of the seventeenth century there were nine synagogues for a population of 2,325 Jews, representing about 4 percent of the general population.3

Under the influence of the humanistic spirit of the Renaissance, many Italian Christians expressed more tolerant attitudes towards their Jewish neighbors. There was also a growing amount of commerce connecting the two communities, with Jews rising to significant positions as bankers, moneylenders, pawnbrokers, and traders of second-hand merchandise. In 1516 Jews were permitted for the first time to establish permanent residences in the city of Venice, on an island that was the former site of a foundry, called “ghetto” in Italian (or “getto” in the Venetian dialect).

Many Jews were becoming increasingly bicultural, fluent in the language, customs, literature, dance, and music of Italy, while at the same time retaining adherence to their ancestral religious traditions. Perhaps the most famous of these bicultural Jews was Rabbi Leon Modena (1571–1648), who served as an intermediary between the Jewish and Christian communities.4 Modena was a skilled author of poetry and prose in both Hebrew and Italian. He was well-versed in rabbinic literature, as well as the Christian Bible, philosophy, scientific theory, and Renaissance literature. He advocated for reforms in the synagogue liturgy but also passionately defended traditional Jewish practice. His Historia de gli riti hebraici, commissioned by an English lord, was the first book to explain the Jewish religion to a general audience. He experimented with alchemy, magic, and astrology, and was a compulsive gambler. Modena was also an accomplished amateur musician, and is credited with encouraging his friend, Salamone Rossi, to compose an unprecedented collection of polyphonic motets in Hebrew for the synagogue.

We don't know very much about Salamone Rossi. He was born circa 1570. His first published music is a book of nineteen canzonets printed in 1589.5 His last published music is dated 1628, a book of two-part madrigaletti. And after that there is nothing. Perhaps he died in the plague of 1628. Perhaps he died during the Austrian invasion in 1630. We just don't know. His published output consists of six books of madrigals, one book of canzonets, one balletto from an opera, one book of madrigaletti, four books of instrumental works (sonatas, sinfonias, and various dance pieces), and a path-breaking book of synagogue motets – in all, some 313 compositions between 1589 and 1628.

***

Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that – to borrow a phrase from music – is contrapuntal.

In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy, religion was a significant marker of identity. And those who were not situated within the borders of Catholicism were required to signify their status of alterity in their clothing, in their locus of residence, and in their name. Salamone Rossi enjoyed a contrapuntal life in two distinct domains, each set off by its boundaries, both physical and political.

Rossi was employed at the ducal palace in Mantua, where he served as a violinist and composer. He was quite the avant-garde composer. He was the first composer to publish trio sonatas.7 Rossi's madrigals are based on texts by the most modern poets of his time, and he was the first composer to publish madrigals with continuo accompaniment.8 There were many other notable musicians at the Mantuan court, including Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) and Giovanni Gastoldi (1554–1609). But as far as we know, Rossi was the only Jew. In August 1606, acknowledging Rossi's stature, the Mantuan Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga (1562–1612) issued an edict that stated, “As we wish to express our gratitude for the services in composing and performing provided for many years by Salamone Rossi Ebreo, we grant him unrestricted freedom to move about town without the customary orange mark on his hat.”9 And yet, as we see in the edict, Rossi still bore the epithet “Ebreo” – Jew.

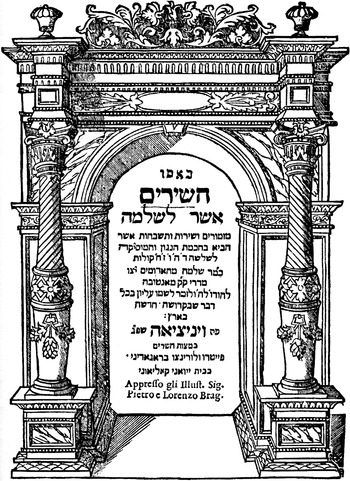

At the Mantuan court, Rossi worked alongside as many as thirty Christian composers, instrumentalists, and singers. Then each night Rossi switched to his Jewish identity, returning to his home in the Jewish ghetto of Mantua, where he lived, and where he worshipped.10 But influenced by Rabbi Modena, Rossi would poke a hole in the cultural boundary line. In a daring innovation, Rossi introduced polyphonic music into the synagogue, bringing the extramural music of the Christian world into the ghetto. In 1622, thirty-three of Rossi's Hebrew motets were published in Venice. The title of the collection, Ha-shirim asher lishlomo (The Songs of Solomon), not only refers to the name of the author (Salamone is the Italian form of Shelomo, or Solomon), but also, by playing on the name of a book of the Hebrew Bible, Shir ha-shirim asher lishlomo (The Song of Songs of Solomon), gives the music an implied intertextual stamp of approval.

As far as we know there were no precedents for Rossi's innovation. Certainly the composer himself believed that was the case. Figure 9.1 shows the title page of Rossi's 1622 publication of his thirty-three polyphonic motets for the synagogue. Notice the words “an innovation (Hebrew: ḥadashah) in the land.” The title page, like the rest of the book, is written almost totally in Hebrew. Here is a translation:

Figure 9.1 Title page of Salamone Rossi, Ha-shirim asher lishlomo (1622).

We can see on this title page some of the challenges of a bi-cultural identity. To describe what they were creating, the authors had to borrow or invent words that did not exist in the Hebrew language. The first word on the page is basso, the Italian word meaning bass, spelled out in Hebrew letters.11 There was no word for harmony or polyphony in Hebrew, so the authors used the Italian word “musica,” again spelled with Hebrew letters. Elsewhere in the book, in order to express musical terminology, Hebrew words were given new meanings. Thus meter was translated as mishkal and music theory as hokhmat ha-shir. This macaronic text with its linguistic code-switching reflected a radical change of culture and musical style.

Indeed the very concept of this book is predicated on both its authors’ and its readers’ ability to negotiate multiple identities. In these polyphonic motets the lyrics are in Hebrew, and the context is the synagogue worship service. But the musical styles, the convention of notation, the musical terminology, and the performative aspect are all borrowed from the culture of Christian Europe.

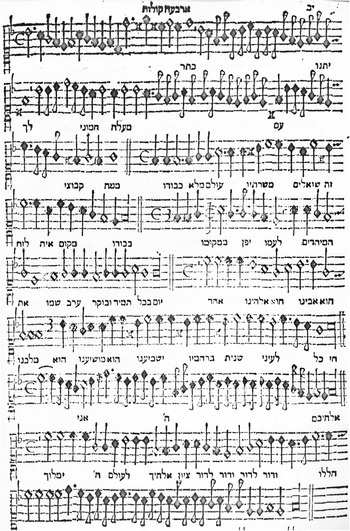

Rossi's bilingual (or bi-directional) identity can be seen most strikingly in a page of music from the 1622 publication (Example 9.1). The musical notation is read from left to right; each word of the Hebrew lyrics, however, must be read from right to left. This manifestation of battling orthographies made for very complicated code-switching.

Example 9.1 Rossi, Keter, canto part book.

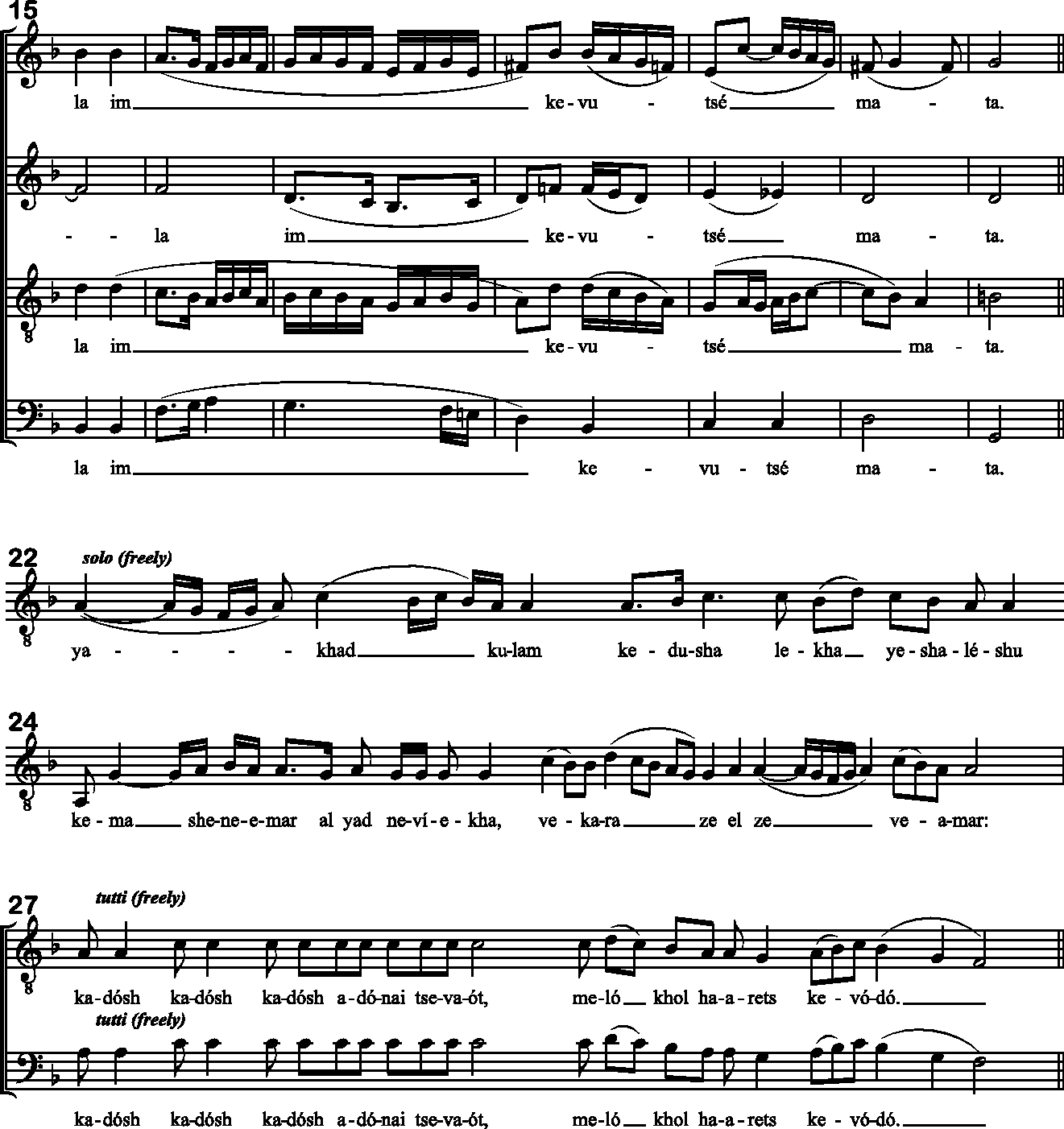

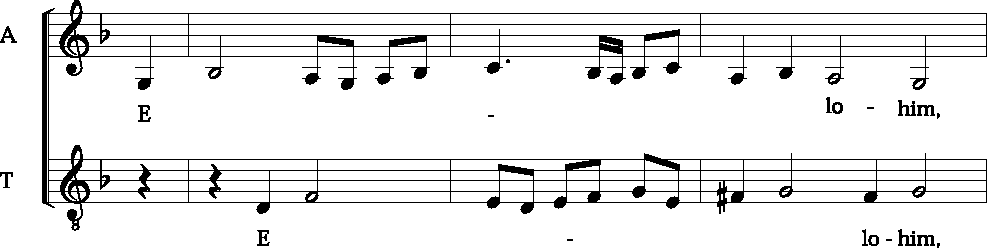

Code-switching also occurs in several of the motets in which the choir would sing certain parts of the prayer in the new polyphonic Italian style, while other sections of the prayer would be chanted by the congregation or the cantor using the traditional monophonic modal melodies. In accordance with the conventions of church music of his time, Rossi inserted double bar lines in the middle of a composition as a signal for the choir to pause while the cantor or the congregation sang the traditional chant. Example 9.2 shows a portion of the present author's attempt to reconstruct a performance of Rossi's Keter.12 Rossi composed music for only a portion of the liturgical text, leaving the rest to be chanted by cantor and congregation in the traditional manner. Rossi's original is shown in Example 9.1.

Example 9.2 Pages 1 and 2 of Rossi's Keter, edited by Joshua Jacobson. Reproduced by permission of Broude Brothers Limited.

Other conventions of Italian polyphony can be found in Ha-shirim. Nine of the thirty-three motets are in the style of cori spezzati, a polychoral format in which singers are divided into two groups in physical opposition, singing at times in alternation, and at times together. This style is commonly associated with the Cathedral of San Marco in Venice, and was widespread in churches throughout Italy and beyond. One of Rossi's polychoral motets, the wedding ode Lemi eḥpots, is set in the “echo” format, well known to choral singers from Orlando di Lasso's “Echo Song” (1581). Lemi eḥpots also features intriguing wordplay between its Hebrew lyrics and Italian homophones. For example, one of the Hebrew lines ends with the phrase kegever be'alma, “as a man with a maid.” The echo chorus then repeats just the last two syllables, alma, which in Italian means “soul.”

One of Rossi's motets suggests a style of dance music that was extremely popular in his time. The Kaddish a5 was composed as a balletto, modeled after his colleague Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi's 1591 collection Balletti a cinque voci con li suoi versi per cantare, sonare e ballare, which was among the best-selling sheet music of the sixteenth century. Like many balletti, but unique among Rossi's motets, Kaddish is in strophic form, with sharply defined rhythms in a largely homophonic texture. It is also the only motet in the collection in triple meter, which was often used for joyous dancing.

Some of Rossi's melodies link him to his Christian contemporaries. The main theme of Rossi's Elohim hashivenu bears a strong resemblance to Lasso's Cum essem parvulus (Examples 9.3a–b). And the bass line of Rossi's Al naharot bavel is nearly identical to that of his colleague Lodovico Viadana's Super flumina Babylonis, a setting of the same text (Psalm 137) in Latin (Examples 9.4a–b).

Example 9.3a Rossi, Elohim Hashivenu (first phrase).

Example 9.3b Orlando Lasso, Cum essem parvulus (first phrase).

Example 9.4a Rossi, Al naharot bavel, basso (first phrase).

Example 9.4b Lodovico Viadana, Super flumina Babylonis (first phrase).

There was bound to be a conflict between modern Jews who had been influenced by the Italian Renaissance, and those with a more conservative theology and praxis. Rabbi Leon Modena described what happened when Rossi's choral music was sung in a synagogue in Ferrara in 1605:13

We have six or eight knowledgeable men who know something about the science of song, i.e. “[polyphonic] music,” men of our congregation (may their Rock keep and save them), who on holidays and festivals raise their voices in the synagogue and joyfully sing songs, praises, hymns, and melodies such as Ein keloheinu, Aleinu leshabeah, Yigdal, Adon olam, etc. to the glory of the Lord in an orderly relationship of the voices according to this science [music].

Now a man stood up to drive them out with the utterance of his lips, answering [those who enjoyed the music], saying that it is not proper to do this, for rejoicing is forbidden, and song is forbidden, and hymns set to artful music have been forbidden since the Temple was destroyed.14

The objections to choral singing were based on several rabbinic rulings. Living as a tiny minority community in exile, Jews were expected to maintain their unique ancestral culture, and refrain from imitating the practices of the Gentiles among whom they lived. Furthermore, as a sign of mourning for the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and its renowned music, Jews were expected to refrain from performing or listening to any joyous music. Mar ‘Ukba (early third century) is quoted in the Talmud decreeing, “it is forbidden to sing [at parties].”15 And his contemporary, Rav, ruled, “The ear that listens to song should be torn off.”16

The great philosopher Moses Maimonides (late twelfth-century Spain and Egypt) stressed the historical reasons for Jews refraining from music:

[The rabbis at the time of the destruction of the Second Temple] prohibited playing all musical instruments, any kind of instrument, and anything that makes any kind of music. It is forbidden to have any pleasure therein, and it is forbidden to listen to them because of the destruction [of the Temple].17

But there were exceptions to this ban on music. Music was allowed, even required, to enhance a religious imperative (mitzvah). The medieval Rabbis known as the Tosafists clarified that there are no restrictions on singing at a wedding: “Singing which is associated with a mitzvah is permitted: for example, rejoicing with bride and groom at the wedding feast.”18 Nor would there be any restriction on singing God's praises in a liturgical service, as this Midrash makes clear: “If you have a pleasant voice, chant the liturgy and stand before the Ark [as leader], for it is written, ‘Honor the Lord with your wealth’ (Proverbs 3:9), i.e. with that [talent] which God has endowed you.”19

But the antagonism towards music, especially non-traditional music, remained strong. Anticipating objections over the publication of Rossi's music, Rabbi Modena wrote a lengthy preface in which he refuted the arguments against polyphony in the synagogue:

To remove all criticism from misguided hearts, should there be among our exiles some over-pious soul (of the kind who reject everything new and seek to forbid all knowledge which they cannot share) who may declare this [style of sacred music] forbidden because of things he has learned without understanding, I have found it advisable to include in this book a responsum that I wrote eighteen years ago when I taught the Torah in the Holy Congregation of Ferrara (may He protect them, Amen) to silence one who made confused statements about the same matter.20

He immediately cites the liturgical exception to the ban on music:

Who does not know that all authorities agree that all forms of singing are completely permissible in connection with the observance of the ritual commandments? I do not see how anyone with a brain in his skull could cast any doubt on the propriety of praising God in song in the synagogue on special Sabbaths and on festivals. The cantor is urged to intone his prayers in a pleasant voice. If he were able to make his one voice sound like ten singers, would this not be desirable?…And if it happens that they harmonize well with him, should this be considered a sin? Are these individuals on whom the Lord has bestowed the talent to master the technique of music to be condemned if they use it for His glory? For if they are, then cantors should bray like asses and refrain from singing sweetly lest we invoke the prohibition against vocal music.21

But Modena goes even further in his defense. He argues that if Jews are imitating the music of Christians, it is only to reclaim their own lost heritage. Modena is using here a classic Renaissance argument. Restoring the glorious culture of antiquity was at the heart of the Italian Renaissance. The Florentines who invented opera claimed that they were reviving the art of ancient Greek theater. Modena claimed that Rossi was actually reviving the musical practice of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, “restoring the crown of music to its original state as in the days of the Levites on their platforms.”22 Modena asserted that the music of Christian churches was derived from the practice of the Levitical choir and orchestra in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. He quotes Immanuel of Rome, who wrote that Christian music “was stolen from the land of the Hebrews.”23 Therefore, he and Rossi were merely reclaiming the lost heritage of the ancient Israelites.24

Modena indulges in hyperbolic praise in his description of the culture of ancient Israel:

For wise men in all fields of learning flourished in Israel in former times. All noble sciences sprang from them; therefore the nations honored them and held them in high esteem so that they soared as if on eagles’ wings. Music was not lacking among these sciences; they possessed it in all its perfection and others learned it from them. However, when it became their lot to dwell among strangers and to wander to distant lands where they were dispersed among alien peoples, these vicissitudes caused them to forget all their knowledge and to be devoid of all wisdom.25

There is no record of Rossi after 1628, when there was an outbreak of the plague in Mantua. In 1630 the ghetto was evacuated during the Austrian invasion, and some of the residents relocated to Venice. Leon Modena established a Jewish musical academy in Venice that functioned from 1628 until around 1638, but there is no mention of Salamone Rossi.

There is no evidence of any other collection of polyphonic synagogue music of the size and quality of Ha-shirim until the nineteenth century. The musicologist Israel Adler discovered several isolated instances of art music that were performed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the synagogues of Venice, Siena, Casale Monferrato, Amsterdam, and Comtat Venaissin.26 These are delightful works, most of them composed by Christian musicians for special occasions, but none having the depth of Rossi's Ha-shirim.

Ha-shirim seems to have been largely forgotten after Rossi's death until the middle of the nineteenth century. While on vacation in Italy, Baron Edmond de Rothschild was given an unusual collection of old part books of music with Hebrew lyrics. Rothschild thought they might be of interest to his synagogue choir director Samuel David, who passed them along to Samuel Naumbourg, Cantor of the Great Synagogue of Paris. With the assistance of a young music student named Vincent D'Indy, Naumbourg prepared the first modern edition of Rossi's music in an anthology that included thirty of the thirty-three motets and was published in 1876. Naumbourg chose modernization over historical accuracy. In accord with nineteenth-century standards, he felt free to add his interpretations for tempo and dynamics, transpose to a different key, rearrange for a different number of voice parts, alter rhythms, even substitute different lyrics. But his edition did instigate a revival and brought Rossi's music to a wider audience. In the twentieth century several new editions of Ha-shirim were published, for both scholars and performers, and numerous recordings were issued. The most significant scholarship on Rossi to date has come from musicologist Don Harrán, who has written an impressive monograph, and edited all of Rossi's music for the American Institute of Musicology's Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae.