5 The fifth element: knowledge

Introduction: doggs, lions, and neo-liberalism

Calvin Broadus Jr.’s career as Snoop (Doggy) Dogg1 gestures to the death of socially conscious hip-hop2 and the birth of the 1990s gangsta rap era in which gun-play, violence against women, and political nihilism were branded as ghetto authenticity.3 Indeed, the years 1992 and 1993 – marked by Snoop Dogg’s appearance on Dr. Dre’s The Chronic and his solo debut album DoggyStyle – delineate what scholars now call the “neo-liberal turn” in hip-hop: the corporate consolidation of independent music labels, the silencing of Black Nationalist politics, and the commodification of human suffering as one of America’s most profitable global exports.4 “The extraordinary commercial penetration of hip-hop,” Tricia Rose argues, has destroyed a “Black cultural form designed to liberate and to create critical consciousness and turned it into the cultural arm of predatory capitalism.”5 As historian and hip-hop activist Kevin Powell laments, Snoop Dogg helped “destroy a culture and art created to save lives, pointed it toward death, and marketed it to the children and grandchildren of its originators.”6

Twenty years ago, the skinny gangsta rapper from Long Beach, California, helped engineer hip-hop’s cross-over from “Black music” to an all-encompassing media lifestyle.7 Long before 50 Cent used his nine bullet wounds to brand a “get rich or die trying” music, video game, clothing, and film franchise, Snoop Dogg brilliantly used his murder trial to market his debut albumDoggyStyle. DoggyStyle’s dense mix of Parliament Funkadelic, Isaac Hayes, and Curtis Mayfield funky samples – combined with Snoop Dogg’s melodic lyrical flow – ushered in the “G-Funk” (Gangsta Funk) subgenre of West Coast rap.8 Unfortunately, as Eithne Quinn observes, the album also “captures in vigorous terms the values of an increasingly nonpoliticized generation” and “a new brand of Black economic empowerment: the ruthless gangsta or enterprising ‘nigga’.”9 Snoop Dogg rebranded rap songs and music videos as infomercials for 40 oz St. Ides malt liquor and Tanqueray Gin, paving the way for artists like Jay-Z and Rick Ross to peddle black Mercedes Benz Maybachs and black American Express “Centurion” cards as the new vision of Black Power politics.10

Beyond rhyming that “bitches ain’t shit, but hoes and tricks,” Snoop Dogg formalized the connections between hip-hop and the pornography industry with his Hustler-produced film Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle (2000).11 His music videos and live performances often promoted and glamorized the pimp lifestyle (i.e. Boss N’ Up [2005]), encouraged sexual tourism in Brazil (e.g. “Beautiful”), and at the 2003 MTV music awards, he walked two Black “bitches” (women) around on dog leashes to promote his animated cartoon series, “Where’s My Dogs At?” While sonically pleasurable, Snoop Dogg’s performances symbolize the crisis of hegemonic masculinity and the betrayal of African American oral and literary traditions.12 Historically, rappers have disguised critiques of white supremacy and state-sanctioned violence in subversive racial performances known as “badman” and “trickster” tales.13 Snoop Dogg, however, was an early adopter of “keeping it real,” the reenactment of racial caricature without the satirical or political edge. He used his Crips Street gang membership and real-life legal troubles, including multiple federal charges for illegal firearms and drugs, to fetishize predatory Black masculinity as all-American entertainment. The result has been global fame and infamy. Over the years, the UK, Australia, and Norway have issued temporary travel bans on Snoop Dogg and his entourage.

Yet, after a three-week trip to Jamaica in 2012, Snoop Dogg has been reborn as “Snoop Lion,” a hip-hop, reggae-infused advocate of Black consciousness, peace, and universal love. The documentary film Reincarnated (2012) chronicles his spiritual journey in Jamaica. Under the tutelage of Rastafarian priests – and under the influence of a copious amount of mari-juana – he learns about the histories of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, the great kingdoms of Africa, and other “truths” not taught in American public schools. Reconnecting with the African diaspora opens his “third eye” to alternative images of Black manhood beyond the streets. By the end of the film, he is renamed after the Lion of Judah, the most sacred symbol of Rastafari culture. Snoop Lion’s Reincarnated (2012) album oozes positivity, with tracks about love, unity, non-violence, and even the healthiness of drinking natural fruit juice without the Tanqueray Gin. Over dancehall beats and Miley Cyrus vocals, he apologizes for selling death to kids and vows to use his music to heal the world.

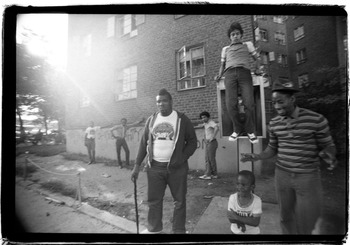

Snoop’s journey for the truth echoes what Afrika Bambaataa (Figure 5.1) coined the fifth element of hip-hop: knowledge. “Knowledge of self” refers to the Afro-diasporic mix of spiritual and political consciousness designed to empower members of oppressed groups. The performance arts of MCing (“rapping”), DJing (“spinning”), breakdancing (“b-girling”), and graffiti (“writing”) are often identified as the “four core elements” of hip-hop, but less attention has been given to the central role of knowledge in the cultural formation of hip-hop culture. This chapter provides a revisionist historio-graphy of hip-hop knowledge, specifically its early normative development within the socio-economic realities of the 1970s’ South Bronx. Building on the spatial theories of Murray Forman and Cheryl Keyes, special attention is given to how Afrika Bambaataa attempted to move hip-hop from street consciousness to Afrocentric empowerment.14 Woven throughout the narrative of this chapter is the theme of tension between knowledge and the commercial impetus of hip-hop. Money, whether from the streets and/or multinational corporations, has helped spread hip-hop culture, but has also served as a major roadblock to making hip-hop part of an emancipatory politic.

Figure 5.1 Afrika Bambaataa and Charlie Chase at the Kips Bay Boys Club, Bronx, New York, 1981.

Afrika Bambaataa’s reincarnation

Snoop Dogg’s reincarnation is reminiscent of the improbable birth of hip-hop culture forty years ago. In the early 1970s, Kevin Donovan, a warlord of the notorious South Bronx Black Spades gang, saw the movie Zulu (1964) on television, won a trip to Africa, and changed his name to Afrika Bambaataa Aasim, an Afro-Islamic name that means “affectionate leader” or “protector.” As Bambaataa (Figure 5.2), Donovan co-opted the Black Spades into the Universal Zulu Nation, and created a global organization dedicated to knowledge, non-violence, and healthy living.15 Bambaataa’s most important contribution to hip-hop culture, beyond coining the phrase “hip-hop” and introducing electronic-funk music into DJing, is his insistence that “knowledge of self” be considered the official fifth element of hip-hop culture.16 Pioneering hip-hop groups of the late 1970s and early 1980s occasionally espoused sociopolitical messages. Brother D and the Collective Effort’s “How We Gonna Make the Black Nation Rise?” (1981) and the Treacherous Three’s “Yes We Can Can” (1982) are two early examples of recorded songs that advocated knowledge of self. However, according to Bambaataa, a coherent ideological movement of beats, rhymes, dance, art, and politics could empower oppressed people around the world.

Figure 5.2 Afrika Bambaataa at Bronx River Projects, February 2, 1982.

Romanticized retellings of hip-hop history tend to describe block parties as mini-revolutions spontaneously born out of the ashes of the failing Civil Rights and Black Power eras. Hip-hop’s “original myth,” as H. Samy Alim calls the narrative of hip-hop’s genesis in the 1970s’ New York ghettos, involves some truth, nostalgia, and wishful thinking. A serious, revisionist hip-hop history, Alim continues, should acknowledge “the immense cultural labor that hip-hop heads engage in as they make a ‘culture’ with a ‘history’ and ‘traditions,’ and of course, ‘an origin.’”17

Afrika Bambaataa, the “Amen-Ra” and “Godfather” of hip-hop culture, has spent a lifetime (re)inventing hip-hop as a coherent, social movement.18 In America, Bambaataa was the chief architect who merged DJs, b-boys, graffiti artists, and rappers into a unified community culture. As breakdance pioneer Jorge “Popmaster Fabel” Pabon recounts, before Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation brought these various art forms together, “each element in this culture had its own history and terminology contributing to the development of a cultural movement.”19

Amid post-industrial destruction of labor market opportunities for young Black and Latino males, middle-class flight from inner cities, and an unsuccessful war on drugs, few social supports were available for urban youth.20 Based on the belief that social problems were caused by the moral irresponsibility of teenage mothers (“welfare queens”) and violent youth (“street thugs”), the neo-liberal social policies of presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan cut domestic spending on healthcare, aid for needy families, and funding for public education programs. Amid the violence and joblessness, the streets became the primary social structure for youth. As Jeff Chang writes:

Gangs structured the chaos. For immigrant latchkey kids, foster children outside the system, girls running away from abusive environments, and thousands of others, the gangs provided shelter, comfort, and protection. They channeled energies and provided enemies. They warded off boredom and gave meaning to the hours. They turned the wasteland into a playground.21

Bambaataa believed that unifying the four core elements under the same cultural tent would provide a sense of identity and purpose for a new generation. His idea to combat the chaos of urban life with music came from watching the film Zulu (1964). In the movie, a small group of Zulu warriors use the sound of beating shields and song to terrify, and then defeat, the powerful British army in pre-colonial South Africa. In the same way, Bambaataa envisioned that music, dance, and a renewed sense of African pride could defeat drug dealers and hopelessness in the South Bronx.

One irony, though, is that gang warfare was the necessary basis of the hip-hop revolution. In order to overthrow the psychological chains of ghetto colonization, Bambaataa had to first merge opposing gangs into a unified Zulu Nation. Inspired perhaps by the early rhetoric of Malcolm X, the answer was the intelligent use of violence. As an early member of the Zulu Nation recalls, Bambaataa systematically grew his movement through “peace treaties” which forced rival gangs and crews to join: “if you resisted, sometimes peace came to you violently. We demanded peace.”22 The reputation of the Black Spades gang kept the drug dealers at bay and the violence to a minimum. The newfound peace allowed former enemies, breakdance crews, DJs, and graffiti writers to congregate at the same park jams and house parties (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Party Flyer, “The Message: Don’t Waste Your Mind on Dust or Any Drugs That Harm Your Body,” Bronx, New York, 1981.

Street consciousness and the music hustle

The early hip-hop “jams” provided reprieve from gang wars, and good times for those who could not afford entry into the relatively expensive funk-disco scene.23 However, the first hip-hop parties were not venues for raising consciousness or examining African identity. Oral history interviews with the “founding fathers,” such as Grandmaster Flash, the Cold Crush Brothers, Crazy Legs (of the R.S.C.), Kool Herc, and Chief Rocker Busy Bee provide a realistic portrayal of hip-hop’s formative years. Sex with “fly girls,” drugs, and alcohol and, of course, music and dancing, were part of the early parties. But so too were gunshots, armed robberies, and fights.24 Most pioneers were focused on throwing parties to make quick money, not educating the masses. The party culture primarily offered an alternative revenue stream for (former) street gangsters, a way to turn skills learned on the streets into a legal music hustle.

The South Bronx was no “Garden of Eden,” untouched by the impetus of capital. The same economic forces that created poverty created hip-hop. As Jeff Chang describes, the Bronx was “blood and fire with occasional music,” a war zone overrun with gangs and thugs who were marginally better than the slumlords, corrupt cops, and politicians.25 One of the greatest ironies is that the crisis in capitalism created both the street hustler and global communications and technology – such as the influx of less expensive Japanese-made turntables, cassette decks, and equalizers – that would eventually give rise to the hip-hop generation.26 If not for the collapse of the industrial economy and shift to service-sector production in the 1970s, hip-hop pioneers would have been at work instead of b-boying in the park or tagging subway cars. In the vacuum of sustainable job opportunities, kids merged street savvy with music to create a grassroots music economy.

In her exhaustive study of hip-hop, Rap Music and Street Consciousness, Cheryl Keyes argues that the streets are key to understanding the aesthetics and performances of rap music. She writes:

The streets nurture, shape, and embody the hip-hop music aesthetic, creating a genre distinct from other forms of black popular music that evolved after World War II. Through a critical assessment of this tradition from within the culture of its birth, we can begin to adequately analyze rap’s performance and aesthetic qualities, interpret its lyrics, and define its height of style.27

Street consciousness, including how corporate moguls reimagine the ’hood, has shaped the historical development of hip-hop culture.28 Beginning with the street economies of the late 1970s, hip-hop refashioned the marketing, branding, and monetizing strategies of organized gang-life, numbers racketeering (illegal lotteries), and drug dealing into a profitable party culture.

Thinking back on the start of his DJing career, Afrika Bambaataa recalls that the early pioneers were “young entrepreneurs, when we didn’t even know we was entrepreneurs.”29 It was the allure of getting money through the relatively safer music scene that attracted the early spinners. Kool Herc (Clive Campbell), considered the father of DJing, explains how he created the “music hustle” in 1974–1975:

I was giving parties to make money, to better my sound system. I was never a DJ for hire. I was the guy who rent the place. I was the guy who got flyers made. I was the guy who went out there in the streets and promoted it. You know? Some nights it’d be packed…less money; some nights it’d be more people…more money. And after that they would say, “Kool Herc and Coke La Rock [his partner and MC] is makin’ money with that music, up in the Bronx.” We was recognized for hustlin’ with music.30

Organizing and marketing these volatile events became an important part of the hustle in the emerging hip-hop business. While there were occasional free block parties and community center jams in the summer, the Bronx’s northeastern climate meant breaking into high school gymnasiums and staging illegal jams. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, as hip-hop became more established, the party scene merged with established discotheque culture at clubs like the Ecstasy Garage and the Black Door.

The music hustlers of the “bombed out” Bronx established a multi-faceted economic structure around music, dance, fashion, and art. The flyer designers of the early and late 1970s, such as “Flyer King” Buddy Esquire, were paid street graffiti artists hired to publicize the weekend parties. Cash incentives for performers and partygoers were commonplace. Importantly, none of this was separate from the street economy. Local criminals provided the prize money for DJ/MC battles and best-dressed contests. Gang members and stick-up kids freelanced as security guards at the door and protected the talent and their equipment from harm. MC El Bee (Larry Boatright), a forgotten pioneer of 1970s’ hip-hop (and childhood friend of members of Public Enemy), argues that the hustlers who funded the early jams, provided physical protection for artists, and paid for the iconic gear should be regarded as the “invisible legends” of hip-hop.

The hustler’s mantra of getting money “by any means necessary,” as KRS-One argues while alluding to the famous Malcolm X slogan, might be considered the sixth element of hip-hop culture. He defines the street entrepreneur as:

Street trade, having game, the natural salesman, or the smooth diplomat. It is the readiness in the creation of a business venture that brings about grassroots business practices…Its practitioners are known as hustlers and self-starters. Entrepreneur – a self-motivated creative person who undertakes a commercial venture.31

Few seem to espouse their love of hip-hop more than KRS-One, yet he acknowledges that money is a core component of the culture. This should not be surprising: “smooth hustling,” “running game,” and “getting over” are compulsory survival adaptations on the margins of society where gainful employment opportunities and safety are scarce. In terms of abstract values, street entrepreneurs demonstrate the Protestant work ethic and spirit of capitalism. On the streets, the hustler grinds through sleepless nights with a stubborn-against-all-odds fortitude to make money. Marketing research firms have attempted to replicate this “get rich or die trying” approach that former street hustlers use to mass-produce hip-hop coolness.32 The problem, though, is that the quest for liberation is rarely popular, profitable, or cool.

Edutainment for knowledge of self

In its first decade (1973–1982), hip-hop was primarily a party culture. The early MC specialized in making announcements, bragging-boasting-and-toasting on the microphone, and performing dirty versions of nursery rhymes. DJs looped and transformed breakbeats, the instrumental or drum section of a song, to keep the b-boys and b-girls dancing to the break of dawn. At best, these parties were successful in making money and redirecting real violence and crime into scripted dance floor performances of the streets.

Grey-haired hip-hoppers should recall that rappers of the pre-crack 1980s era appropriated the alter egos of local cocaine dealers. Kurtis Blow, Lovebug Starkski, J-Ski, and Kool Rock-ski (of the Fat Boys) are a few examples.33 Sugar Hill’s “Rapper’s Delight” (1979) invokes the same trite narratives about luxury cars (e.g. “a Lincoln Continental and a sunroof Cadillac”), money (e.g. Big Bank Hank), and pimping “fly girls” (e.g. “hotel, motel, Holiday Inn/If your girl starts actin’ up/then you take her friend”) found in contemporary rap. Taking women from the club, to the limo, to the hotel for a champagne orgy is a prominent scene in Charlie Ahern’s Wild Style (1982), perhaps the most acclaimed film on early hip-hop.

Bambaataa redesigned the hip-hop party scene as “edutainment,”34 a mix of fun and socially conscious music and discourse. Unique was Bambaataa’s attempt to educate partygoers with a pro-Black soundtrack of James Brown (i.e. “I’m Black and I’m proud”), Sly & The Family Stone (“Everyday People”), and Earth, Wind, & Fire (“Keep Your Head to the Sky”). During one of his signature jams, Bambaataa would bait partygoers with the familiar dance tracks, then once the dance floor was full, switch to the German electropop of Kraftwerk and the Nigerian Afro-beats of Fela Kuti. “During long music segments when Bam was deejaying,” his official biography recalls, “he would sometimes mix in recorded speeches from Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and, later, Louis Farrakhan.”35 Back then the freshest b-boys emulated the expensive athletic gear and leather jumpsuits worn by corner dealers. To combat the street culture, Bambaataa and the Zulus would rock parties dressed as ancient Egyptian pharaohs, indigenous Native Americans, or Afro-futuristic space aliens inspired by Parliament Funkadelic. Borrowing from the strategies of pan-African leader Marcus Garvey, Bambaataa bestowed partygoers with African-inspired titles of royalty. “Fly girls” were to be called “queens,” and treated as such, while b-boys became reformed “kings.”

Through his jams, Bambaataa slowly converted paying partygoers into loyal followers, and eventually, into the world’s first and largest hip-hop political organization known as the Universal Zulu Nation. The Zulu Nation appropriated snippets of the political youth movements of the 1960s and 1970s, including the anti-Vietnam War movement, the hippie-infused flower power movement, and the Muslim teachings of the Nation of Islam and the Nation of Gods and Earths (the “Five Percenters”; see Chapter 6).36 Rather than focusing on a specific political agenda, Bambaataa’s notion of hip-hop knowledge involves “factology,” an all-inclusive hodgepodge of any and all spiritual beliefs, metaphysics, science and mathematics, world history, and hidden insights from alien conspiracy theories and Hollywood movies.37 Knowledge of self, according to the Zulu Nation’s literature, can be derived from the critical and self-reflective study of anything in the universe, as long as knowledge is deployed toward peace, unity, love, and having fun. “The Infinity Lessons,” the basic teachings of the Zulu Nation, emphasize a lack of substantive and methodological limits to knowledge. As Aine McGlynn writes:

One of the most beautiful and appealing aspects of the lessons is that they are never complete. They can always, at any time, by any member, be added to…Hip-hop at its best is about the creativity that can happen within a specific moment; this is the legacy of the street corner ciphers, freestyle sessions where the beatboxer provided the rhythm and the rapper came up with rhymes right on the spot. In its purest form, hip-hop is dynamic and constantly morphing in the same way as the Infinity Lessons do.38

The all-inclusive universalism of the group is inherently anti-race and anti-racist, as it focuses on the commonality of humanity. “We believe in truth whatever it is. If the truth or idea you bring us is backed by facts, then we as Amazulu [Zulus] bare witness to this truth. Truth is Truth.”39 Still, the group’s primary website on factology shows the influence of Black Nationalist ideology and the explicit rejection of the Western, “white supremacist” knowledge found in schools and official textbooks:

We believe that through white supremacy many of the history books which are used to teach around the world in schools, colleges and other places of learning have been distorted, are full of lies and foster hate when teaching about other races in the human family. We believe that all history books that contain falsehoods should be destroyed and that there should be history books based on true facts of what every race has contributed to the civilization of Human Beings. Teach true history, not falsehood, only then can all races, and nationalities respect, like or maybe love each other for what our people did for the human race as a whole.40

Bambaataa’s Universal Zulu Nation has created a global movement dedicated to peace, healthy eating, spirituality, and environmentalism. In the last forty years, the Zulu Nation has forcibly removed drug dealers from neighborhoods, rallied around political prisoners, and recently, warned WorldStarHipHop.com to stop pandering violent and sexual images to youth. Bambaataa was nominated to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2007, and his song “Planet Rock” is considered one of Rolling Stone’s greatest 500 songs of all time. However, commercial success and wealth have both evaded Bambaataa. His last chart-topping hits (in the USA and UK), “Planet Rock” (1982), “Looking for the Perfect Beat” (1983), and “Renegades of Funk” (1984), are now three decades old. A renegade of funk, to be sure, Bambaataa became marginalized by eschewing what Watkins calls hip-hop’s Faustian bargain: “In exchange for global celebrity, pop prestige, and cultural influence hip-hop’s top performers had to immerse themselves into a world of urban villainy.”41 Bambaataa refused, settling instead for a career as a working-class DJ and spiritual leader.

Conclusion: hip-hop knowledge beyond the beats and streets

The notion of a fifth element of hip-hop was briefly made popular (and profitable) in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Acts like Public Enemy and KRS-One, and hip-hop’s “Native Tongues” movement including A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, and the Jungle Brothers reintroduced Afro-centric edutainment into mainstream hip-hop.42 However, in the USA, conscious hip-hop continues to be segregated in niche, “underground” markets. Jay-Z has offered these classic lines on the relationship between knowledge and the hip-hop industry: “If skills sold, truth be told, I’d probably be/Lyrically Talib Kweli/Truthfully I wanna rhyme like Common Sense/But I did 5 mill’ – I ain’t been rhyming like Common since.”43 The influx of neo-liberal logic makes it difficult for commercial rap music to nurture intellectual or spiritual growth. The current journeys of Snoop Lion and Afrika Bambaataa speak to the surmounting difficulties of commerce, and the potential of hip-hop knowledge outside of music.

Mr. Broadus’s reincarnation from Dogg to Lion encapsulates the chapter’s overall assertion that commercial entertainment and emancipatory politics make uncomfortable bedfellows. Music critics lambasted his Reincarnated album and film, labeling his Jamaican trip a misguided “cultural safari” and elaborate moneymaking scam.44 Bunny Wailer, an original member of Bob Marley and the Wailers, along with the Ethio-Africa Diaspora Union Millennium Council, issued a cease-and-desist letter to Snoop Lion, claiming that his Rastafarian conversion was an attempt to cash in on their religion. “Smoking weed and loving Bob Marley and reggae music,” according to the group, “is not what defines the Rastafari Indigenous Culture.”45 In response to Bunny Wailer, Snoop Lion fired back, “Fuck that nigga. Bitch-ass nigga. I’m still a gangsta don’t get it fucked up. I’m growing to a man, so as a man, do I wanna revert back to my old ways and fuck this nigga up, or move forward, shine with the light?”46

To fully complete his transformation from gangster to spiritual leader, Snoop Lion may have to focus on community service initiatives and philanthropy outside of the music industry. In a partnership with the League of Young Voters, Snoop Lion now uses his celebrity to speak out against gun violence, while his “Snoop Youth Football League” teaches inner-city youth the “values of teamwork, good sportsmanship, discipline, and self-respect, while also stressing the importance of academics.”47

DJ Afrika Bambaataa has added “professor” to his many designations, after being appointed as a visiting scholar at my home institution Cornell University. Years ago, the former Black Spades warlord transformed ghetto street entertainment and entrepreneurship into a social movement. Now, as Ivy League professor, he is at the center, remaking elite educational spaces. College students have been reading hip-hop textbooks since the early 1990s, and Arizona University students can now earn a minor in hip-hop studies. However, Bambaataa is pioneering a new phase of the artist-centered hip-hop studies movement, in which hip-hop knowledge is created and transmitted through the unmediated collision of instrumentation, lyricism, and experience.48 He joins artists like Bun-B of UGK (Rice University), M-1 of dead prez (Haverford College), Wyclef Jean (Brown University), 9th Wonder (Harvard University), and the Roots’s ?uestlove (New York University) in this new phase of hip-hop knowledge.

Hip-hop knowledge, the fifth element of the culture, has migrated from dislocated ghettos, to corporate boardrooms, to the corridors of the ivy towers. While this is an exciting innovation in formal education, this move is likely to antagonize the integrity of hip-hop knowledge.49 What place, if any, will radical, counter-hegemonic thought, Afrocentricism, or street knowledge have in spaces that operate primarily for the reproduction of race-gender-social class advantage? What does “knowledge of self” mean for students training to become future owners of Wall Street hedge funds? Timely is Houston Baker’s early declaration that the ultimate goal of hip-hop studies should be to disrupt the “fundamental whiteness and harmonious Westerness of higher education” concerned only with “tweed-jacketed white men.”50 Likewise, time will tell how hip-hop’s fifth element will adapt to the increasing corporatization and privatization of American education. The college and university hustle may prove to be more vicious than the streets or music industry.

Notes

1 Due to contractual agreements, Snoop Doggy Dogg shortened his name to “Snoop Dogg” in 1998 after leaving Death Row Records for Master P’s No Limit Records.

2 In this chapter, I use the words “rap” and “hip-hop” interchangeably. Rap music and hip-hop are the same thing in colloquial, everyday speech. But for hardcore aficionados and fans (known as “hip-hop heads,” “true-schoolers,” and “purists”) the rap–hip-hop conflation is tantamount to blasphemy. In what H. Samy Alim has coined “hip-hop linguistics,” the politics of language surrounding the rather synonymous words involve a complex battle over race–gender–social class, authenticity, identity, cultural ownership, and belonging. I acknowledge these debates as sociologically interesting. See , Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip-Hop Culture (London: Routledge, 2006).

3 and , When Rap Music Had a Conscience: The Artists, Organizations, and Historic Events That Inspired and Influenced the “Golden Age” of Hip-Hop from 1987 to 1996 (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2007); , Nuthin’ but a “G” Thang: The Culture and Commerce of Gangsta Rap (Popular Cultures, Everyday Lives) (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005); , Everything but the Burden: What White People are Taking from Black Culture (New York: Broadway Books, 2003).

4 , I Mix What I Like! A Mixtape Manifesto (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011); , Stare in the Darkness: The Limits of Hip-Hop and Black Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). Cultural critic Greg Tate poetically describes hip-hop’s neo-liberal turn as “the marriage of heaven and hell, of New World African ingenuity and that trick of the devil known as global hyper-capitalism.” See , “Hiphop Turns 30: Whatcha Celebratin’ For?,” Village Voice, December 8, 2004. Available at www.villagevoice.com/2004-12-28/news/hiphop-turns-30/ (accessed June 28, 2013).

5 , “Hip-Hop on Trial: Hip-Hop Doesn’t Enhance Society, It Degrades it,” Intelligence Squared and Google+ “Versus Liberating Opinion” Debate Series, June 27, 2012. Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3-7Y0xG89Q (accessed May 13, 2013).

6 On the hip-hop industry and Snoop Dogg, Kevin Powell writes, “Hip-hop culture has been assassinated by the hip-hop industry’s desire to make money by any means necessary. It’s the record and radio execs, the network producers, the publicists, the handlers, and the magazine writers and editors, of all persuasions, who push these images with no conscience whatsoever.” See , “Hip-Hop Culture Has Been Murdered,” Ebony, June 2007, p. 61.

7 Craig S. Watkins, “The Hip-hop Lifestyle: Exploring the Perils and Possibilities of Black Youth’s Media Environment,” paper presented at Getting Real: The Future of Hip-Hop Scholarship, University of Wisconsin-Madison, September 21, 2009.

8 Justin Williams provides an in-depth analysis of the sonic and geographical significance of Dr. Dre’s “G-Funk” production during the early 1990s, including the layering of electro-funk and synthesizers. See , “‘You Never Been on a Ride Like this Befo’: Los Angeles, Automotive Listening, and Dr. Dre’s ‘G-Funk,’” Popular Music History4/2 (2009): 160–176.

9 Quinn, Nuthin’ but a “G” Thang, pp. 15–16.

10 James Peterson, “All Black Everything: Exceptionalism and Suffering,” TedX Lehigh University, April 23, 2013. Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=ay0tKg9DyEw (accessed May 10, 2013). While the original “merchants of cool” Run-D.M.C. (backed by Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin) had teens everywhere pulling the laces out of Adidas shell-toes in the mid-1980s, their sneaker endorsement paled in comparison to the corporatization of Snoop Dogg’s music and image. The Run-D.M.C. lyrics “Calvin Klein’s no friend of mine/Don’t want nobody’s name on my behind” captures their limited willingness to use music to sell products.

11 In the USA, Hustler magazine is known for its explicit pictures of sexual intercourse, and in recent years the Hustler branding has extended to strip clubs, sex toys, and film.

12 Snoop Dogg’s lyrics, Robin D. G. Kelley writes, “represent nothing but senseless, banal nihilism. The misogyny is so dense that it sounds more like little kids discovering nasty words for the first time than full-blown male pathos. It is pure profanity bereft of the rich story telling and use of metaphor and simile that have been cornerstones of rap music since its origins.” , “Kickin’ Reality, Kickin’ Ballistics,” in (ed.), Droppin’ Science: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hip-Hop Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), p. 147.

13 , To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic (New York: New York University Press, 2007); , Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).

14 , The ’Hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip-Hop (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2002); , Rap Music and Street Consciousness: Music in American Life (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

15 , Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), pp. 89–166.

16 In 1982, a reporter for the Village Voice newspaper asked Afrika Bambaataa to name the party culture that was starting to become big business outside of New York. As Bam recounts, his choice of the word “hip-hop” was arbitrary. He chose “hip-hop” because it was a cool phrase that some of his favorite MCs would use on the mic. “I could have easily picked ‘boing boing,’ ‘going off’ or any other nonsensical word.” The incident speaks to a fascinating aspect of hip-hop’s first decade. Until then, no one had bothered to name the music or culture. Afrika Bambaataa, “Hip Hop: Unbound from the Underground,” Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, April 5, 2013.

17 , “Straight Outta Compton, Straight aus Munchen: Global Linguistic Flows, Identities, and the Politics of Language in a Global Hip-Hop Nation,” in , , and (eds.), Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language (New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 7.

18 The locomotion of hip-hop history cannot be reduced to the actions of great Black men, and the discussion of Afrika Bambaataa is not meant to marginalize the contributions of women. See , The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop (New York University Press, 2006). Likewise, hip-hop’s fundamental “Blackness” has become a major point of contention, as some argue that the emphasis on Blackness devalues the contributions of Latinos, especially Puerto Ricans. See , New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

19 “Popmaster Fabel” Pabon, “Physical Graffiti: The History of Hip Hop Dance,” in (ed.), Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop (New York: Basic Civitas, 2006), p. 19.

20 , The Hip Hop Generation: Young Blacks and the Crisis in African American Culture (New York: Basic Civitas, 2002).

21 Chang, Can’t Stop, p. 49.

22 Emphasis added, as quoted in , Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap Oybonna Green (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2007), p. 4.

23 , , and , Born in the Bronx: A Visual Record of the Early Days of Hip-Hop (New York: Rizzoli, 2007).

24 and (eds.), Yes Yes Y’all: The Experience Music Project Oral History of Hip-Hop’s First Decade (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002).

25 Chang, Can’t Stop, pp. 41–65. Chang’s study of the early 1970s’ ghettoscape chronicles the creation of hip-hop by gangs. The streets provided socialization for youth – family, education, and entertainment – when traditional social structures failed or were destroyed by social policies.

26 Kelley, “Kickin’ Reality, Kickin’ Ballistics”; Quinn, Nuthin’ but a “G” Thang.

27 Keyes, Rap Music and Street Consciousness, p. 122.

28 Forman, The ’Hood Comes First.

29 Fricke and Ahearn, Yes Yes Y’all, p. 45.

30 Ibid., pp. 28–29.

31 , The Gospel of Hip-Hop: First Instrument (Brooklyn, NY: powerHouse Books, 2009), pp. 122–123, emphasis in the original.

32 and , The Tanning of America: How Hip-Hop Created a Culture That Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy (New York: Gotham Books, 2011).

33 The “ski” moniker is an allusion to having so much cocaine that one could ski on the white powder.

34 Edutainment is also the title of an album by Boogie Down Productions released in 1990.

35 Universal Zulu Nation, “UZN Beliefs,” available at Zulunation.com.

36 Known as the “Five Percenters,” the Nation of Gods and Earths is an offshoot of the Nation of Islam that recruits heavily in prisons and on street corners. Core to the belief system is that 85 percent of the world is ignorant, 10 percent knows the truth, but uses it to exploit others, while the other 5 percent uses “knowledge of self„ to teach others how to live peaceful, spiritual lives.

37 , “Counterknowledge, Racial Paranoia, and the Cultic Milieu: Decoding Hip-hop Conspiracy Theory,” Poetics39/3 (2011): 187–204.

38 , “The Native Tongues,” in (ed.), Icons of Hip-Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, vol. 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLO, 2007), pp. 269–270.

39 Zulunation.com, “UZN Beliefs.”

40 Ibid.

41 , Hip Hop Matters: Politics, Pop Culture, and the Struggle for the Soul of a Movement (Boston: Beacon Press, 2005), p. 2.

42 McGlynn, “The Native Tongues.”

43 Jay-Z, “Moment of Clarity,” The Black Album.

44 , “Snoop Lion Reincarnated Review,” Pitchfork, April 24, 2013. Available at http://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/17920-snoop-lion-reincarnated/ (accessed June 28, 2013). Likewise, music critic Derek Staples advises that listeners embrace the new Snoop Lion with a healthy skepticism. “Before falling into Snoop’s Rastafari renaissance, remember that this is also the man who claimed to be a member of the Nation of Islam in 2009 and tried reaching into the R&B world with his project Nine Inch Dicks in ’06.” See , “Album Review: Snoop Lion – Reincarnated,” Consequence of Sound, April 25, 2013. Available at http://consequenceofsound.net/2013/04/album-review-snoop-lion-reincarnated/ (accessed June 28, 2013).

45 , “Snoop Lion: Old Dogg, New Tricks from the World’s Most Recognisable Gangsta Rapper,” The Independent, April 19, 2013. Available at www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/snoop-lion-old-dogg-new-tricks-from-the-worlds-most-recognisable-gangsta-rapper-8580837.html (accessed July 10, 2013).

46 As quoted in , “Q&A: Snoop Lion Strikes Back at ‘Reincarnated’ Collaborator Bunny Wailer,” Rolling Stone, April 24, 2013. Available at www.rollingstone.com/music/news/q-a-snoop-lion-strikes-back-at-reincarnated-collaborator-bunny-wailer-20130424 (accessed July 9, 2013).

47 Snoop Football League, “About Us,” Snoopfl.net, retrieved July 19, 2013 from http://snoopyfl.net/page.php?page_id=39811 (accessed July 19, 2013).

48 , “Love and Hip Hop: (Re)Gendering the Debate over Hip Hop Studies,” Sounding Out! Available at http://soundstudiesblog.com/2013/04/01/love-and-hip-hop-regendering-the-debate-over-hip-hop-studies/ (accessed July 10, 2013).

49 and , “Is Hip-Hop Education Another Hustle? The (Ir)Responsible Use of Hip-Hop as Pedagogy,” in and (eds.), Hip-Hop(e): The Cultural Practice and Critical Pedagogy of International Hip-Hop (New York: Peter Lang, 2012), pp. 195–210.

50 , Black Studies, Rap, and the Academy (University of Chicago Press, 1993), p. 8.