4 Music under Louis XIII and XIV, 1610–1715

After the domestic religious wars of the sixteenth century, seventeenth-century France saw a period of relative internal stability during the reigns of Louis XIII (r. 1610–43) and Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715), though religious conflict with the Huguenots was never far from the surface, and external wars occupied both Louis XIII (the Thirty Years War, 1618–48) and Louis XIV (particularly the War of Spanish Succession, 1701–14) for much of their reigns. With the help of his premier ministreCardinal Richelieu, Louis XIII worked to consolidate and centralise the power of the Bourbon dynasty; Louis XIV continued this process with Cardinal Mazarin until 1661, and then alone, from Paris and later Versailles. Although recent scholars have questioned the concept of ‘absolute power’ or ‘absolutism’, Louis XIV, through a programme of image-making and the arts, as well as through political means, probably did more than any other single ruler to create a mystique of grandiloquence and glory that posterity has not effaced.

Tendencies towards centralisation and a resulting isolation were reflected in seventeenth-century French music.1 In contrast to Italy, where the near-simultaneous appearance of the first solo-monody publication and the first opera production signalled the rise of what later became known as the Baroque period, France witnessed no such dramatic shift in aesthetic, and in France the term has generally been applied less frequently. Instead, for much of the early part of the seventeenth century, French musicians remained strongly influenced by the practice of so-called musique mesurée (the practice of declaiming text in ‘syllabic homophony’ in supposed imitation of classical metres), with polyphony remaining more attractive to the French than monody: as Claude Le Jeune (c. 1530–1600) stated in the preface to his Printemps (1603), the French retained the ‘improvements’ of polyphony attained over the past centuries, rather than discarding them as the Italians had done. In broader musical terms, this influence was expressed in the continuing multi-voiced character of the air de cour, liturgical music and instrumental ensemble music. Although this character was often homophonic (especially in instrumental music based on the dance), liturgical music often looked back to the counterpoint of the sixteenth century, and some instrumental works adopted a self-consciously archaic contrapuntal style. By the middle of the century, the solo voice had gained in importance, both airs sérieux for domestic performance and opera airs now being conceived as ‘solo with accompaniment’ rather than as homophony; but in contrast to Italy, where opera choruses were rare, the homophonic chorus never lost its attraction for Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–87), the most important composer of the second half of the century. French music continued to remain relatively isolated for much of the seventeenth century, as it tended to exhibit a tuneful directness and to eschew virtuosity. This style held sway in all genres until the late seventeenth century, when Italian influence began to be felt through the use of abstract forms such as the sonata, virtuosity and the rise of Italian-influenced opera. The incorporation of Italian influences into French music preoccupied critics and theorists in the early years of the eighteenth century, and through these debates over the comparative merits of the French versus the Italian style, modern musical criticism began to develop. Finally, French musicians learned to incorporate and reconcile these Italian elements to produce the famous goûts réunis of figures such as François Couperin (1668–1733).2

Music under Louis XIII

When the eight-year-old Louis succeeded to the French throne after the assassination of his father Henri IV in 1610, the outward organisation of the musical establishment at court and the roles it played did not change, nor would they for the remainder of the century. As Louis XIII tightened his grip on power, however (he assumed personal rule in 1617, after the regency of his mother, Marie de Médicis), music at court became as much directed to political ends as to entertainment and worship. Although the most obvious examples of a political role for music were the frequent performances of ballets de cour (court ballets), which featured thinly disguised allegories of Louis as victorious over adversity, most famously in the Ballet de la délivrance de Renaud in 1617, in other ways too music served, and was subject to, the growth of Louis’s absolutist rule. Only forty years earlier, Charles IX’s Académie de Poésie et de Musique had made explicit the Platonic conception of the harmony inherent in music reflecting and reinforcing the harmony of a well-governed state. Under Louis too, all genres of music, from liturgical and devotional to court entertainment and music for entrées (ceremonial entrances into towns and cities), were engaged to serve the political needs of the king.3

As part of Louis’s controlling influence, musical activity became centralised at court. This centralisation extended to music publishing, with the king continuing to grant a monopoly (known as a privilège) to members of the Ballard family, during most of this period Pierre. From his appointment in 1607 until his death in 1639, Pierre Ballard’s musical tastes and commercial interests dominated music publishing in Paris and indeed France more widely, with only the occasional threat to his hegemony emerging from figures such as the composer Nicolas Métru (c. 1610–c. 1663) in 1635. After that threat, in 1637 Ballard was granted an even more exclusive monopoly in a decree from Louis XIII which also extravagantly praised the quality of his work, but on Ballard’s death the king nevertheless complicated matters by granting a privilège to Jacques Senlecque for the printing of plainchant, as well as to Pierre’s son and successor, Robert. The Ballards were eager to publish popular and fashionable repertoires (such as the books of airs de cour by the court composers Pierre Guédron, after 1564–c. 1620, and Antoine Boësset, 1586–1643), but less inclined towards sacred or instrumental ensemble music, though the firm was responsible for the publication of Jehan Titelouze’s Hymnes de l’église pour toucher sur l’orgue (1623), the only printed keyboard music to survive from the entire era. In the context of musical activity already centralised at court (a hallmark of absolutist rule, continuing with the reign of Louis XIV), Ballard’s selective choices and commercial impulses, together with the favourable survival of manuscripts from royal circles, preserve a historical picture of musical activity almost completely dominated by the royal household.

The musicians of the royal household were distributed among a number of performing ensembles (some musicians being members of more than one). The musique de la chambre was controlled by a surintendant (probably the most important musician at court) and participated in all aspects of the court’s musical life – sacred, secular and ceremonial. Under the direction of the surintendant (during Louis XIII’s reign Pierre Guédron, Henry Le Bailly, d. 1637, Paul Auget, c. 1592–1660, and Boësset), a small vocal ensemble (one elite singer to a part, with three boys taking the top line) together with a few instruments (lute, harpsichord, flute and viols) provided both secular and devotional entertainment for the court, while the Violons du Roi, considerably enlarged in the early years of Louis XIII’s reign with players from the Paris violin guilds, provided music for both social dancing and ballets de cour. While the musicians of the grande écurie (literally ‘large stable’), which consisted of trumpets, oboes and drums, provided ceremonial music for processions and large-scale events such as the entrées, the Chapelle Royale (sixteen men singing the lower parts and eight boys singing the top line, all under the direction of a sous-maître) performed music for the daily liturgy at court, and combined with the singers of the musique de la chambre on special occasions.

Music and ceremony

Music was an essential component of a number of royal ceremonies, and was clearly intended to heighten their effectiveness as projections of royal power both in Paris and throughout the country. In particular, as an absolute monarch ruling by divine right, Louis wished to be identified with God himself (or to be a ‘Vice-God’, as Godeau, bishop of Grasse, later put it). To that end, biblical (particularly psalm) texts featured prominently in ceremonial musical settings: just as David, the king-musician and author of many psalms, wisely ruled over the Israelites (God’s chosen people), so Louis (incidentally also in reality a proficient musician) ruled over the French (also supposedly God’s chosen people) with the help of music.

As Louis travelled through France consolidating power, ceremonial entrées, accompanied by music, were often organised to celebrate his arrival at a particular town or city. Although none of the music used on these occasions has survived, eye-witness accounts describe the kinds of performances that took place. During the entrée into Paris in 1628 following the military success against the Huguenots at La Rochelle, for example, the procession stopped at numerous ‘Arcs de Triomphe’. At the St Jacques gate the ‘Trompettes & les Tambours’ performed; at the arch of St Benedict, the ‘Hauts-bois’ (loud wind instruments); at the arch of St Severin, the ‘Musetes de Poictou’ (a consort of bagpipe-like instruments, part of the grande écurie); at the ‘Petit Pont’, ‘la Musique douce de voix, & d’Instruments’ (probably a description of the musique de la chambre); at the New Market, ‘le concert de Violons’; and at the Arch of Glory, ‘two choirs of musicians answered each other back and forth: one of wind instruments, the other of violins’.4

Music as a vehicle for biblical text was inevitably an important feature of Louis’s coronation at the cathedral of Notre-Dame, Reims, on 17 October 1610. Early in the ceremony the archbishop of Rheims sang the verse ‘Domine salvum fac Regem’, to which the people responded ‘Et exaudi nos in die qua invocaverimus te’ (Psalm 20: ‘O Lord save the King’, ‘And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee’), a text that played on the ambiguity of the psalmist and portrayed Louis as ‘king’ in the heavenly sense. Musical settings of this text would become ubiquitous during the later reign of Louis XIII and that of Louis XIV, forming an integral part of the daily Low Mass at Versailles. Later, the canons of the cathedral sang, in fauxbourdon, ‘Domine in virtute tua letabitur Rex’ (Psalm 21: ‘The King shall rejoice in thy strength, O Lord’), another psalm text highlighting the parallels between King David and King Louis. At the end of the coronation, the assembled gathering sang the Te Deum; this was also used frequently for other celebrations such as peace treaties and the culmination of entrées, including the one in 1628. According to the account preserved by Godefroy, ‘all the people made their acclamation and cried “Long live the King!”, while trumpets, shawms and other instruments sounded: and then the bishop of Reims began the Te Deum accompanied by the organ and other musicians’.5

Sacred music

Sacred music was clearly influenced by the musical and religious currents of the day.6 Although later in the century a strong desire to retain independence from Rome would manifest itself in the adoption of a Neo-Gallican liturgy and chant, under Louis XIII the revised Tridentine Roman liturgy was officially adopted as the liturgy of France in 1615. By contrast, the specific reforms of the Council of Trent were never formally adopted, but their spirit, and that of the entire Counter-Reformation, could be felt in much sacred music. Figures such as François de Sales, with their message of personal devotion and individual piety, were widely revered in France, and sacred music reflected this individualism. Sacred music also became more open to secular influences, with devotional music in particular adopting characteristics of the air de cour.

Under Louis XIII, the Chapelle Royale lost its pre-eminent position as a musical establishment. Virtually no music survives from this period, but what little there is suggests a conservative repertoire based almost entirely on sixteenth-century compositional practices, using instruments (cornets and sackbuts) only to double the voices. The music of Eustache Du Caurroy (1549–1609), chapel composer or sous-maître until 1609, exemplifies this conservative style, and a surviving set of eight Magnificats by Nicolas Formé from the middle of Louis XIII’s reign shows little advance in technique. Only in Formé’s Mass Aeternae Henrici Magni … (1638) do we see any hint of the compositional procedures later used there under Louis XIV, with the vocal forces divided into two contrasting choirs.7

If the Chapelle Royale remained primarily conservative, the musique de la chambre was quicker to adopt more progressive musical practices. According to contemporary accounts the musique de la chambre was required to sing ‘graces’ after the king’s meals, and the influence of the polyphonic air de cour (which they otherwise regularly sang) on these devotional works is clear. Setting Latin texts based on psalms or from the Song of Solomon, these works were often imbued with allegorical meaning: the anonymous Egredimini filiae Sion, for example, makes reference to the coronation of King Solomon by his mother, a clear allusion to the regency of Marie de Médicis, Louis’s mother. More clearly dependent on the air de cour is Veni, sponsa mea, a dialogue between Christ and his Bride (a common Counter-Reformation analogy for the church), which makes use of the musique mesurée rhythms and the variable scoring found in the air de cour.

Elsewhere in Paris, and indeed in the rest of France, most secular (i.e. non-monastic) churches remained conservative in outlook. The cathedral of Notre-Dame remained so throughout the seventeenth century, with polyphonic Mass settings by figures such as Henri Frémart (d. after 1646) forming the core of the repertoire. The Sainte-Chapelle maintained a similar musical staff and performed similarly conservative repertoire. Under the composer André Pechon (c. 1600–after 1683) much of the liturgy was sung in fauxbourdon at the royal parish church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, as in other major churches. Only in the south-west of France, where a school of composers including Guillaume Bouzignac (c. 1587–after 1642) developed a more madrigalian and dramatic style, did church music break free from sixteenth-century practices. It was left to the monastic institutions, freed from the control of the diocese of Paris, to embrace more progressive ideas from Italy, although music from only one of these survives: the royal Benedictine abbey of Montmartre.

During the reign of Louis XIII, the abbey of Montmartre witnessed a flourishing of sacred music under Abbess Marie de Beauvilliers and her maître de musique, Boësset (also surintendant de la musique de la chambre).8Boësset composed for the unusual combination of three or four high voices (sung by the nuns), bass (probably sung by Boësset himself) and basso continuo of organ and bass viol (the earliest use of the basso continuo in France). Often referred to as ‘transitional’ in style, this repertoire made use of the learned polyphonic techniques of the sixteenth century (in France and elsewhere seen as a symbol of ‘church music’) softened by the influence of the air de cour. The works skilfully juxtapose supple melodic solos accompanied by basso continuo with full choruses and points of strict imitation. Montmartre, together with the church of the Congregation of the Oratory next to the Louvre, also saw the instigation of a particularly French phenomenon, so-called plain-chant musical. Under the influence of the Counter-Reformation, the air de cour and humanist impulses surviving from the end of the sixteenth century, the Gregorian chant used for the majority of the liturgy was considered too melismatic and complex. In the early decades of Louis’s rule, the leader of the Oratorian Order, François Bourgoing, and an anonymous nun at Montmartre independently developed simpler, syllabic repertoires of chant which embodied the new trends. At Montmartre this body of chant (particularly the hymns) was subsequently incorporated into Boësset’s polyphonic repertoire.

Secular music

During the reign of Louis XIII, vocal music was more highly valued than abstract instrumental music. Accordingly, instrumental music, though of course widely performed, remained firmly rooted in dance, with the lute and later the harpsichord the most popular solo instruments. (The Ballard house published numerous collections of lute music during this period.) Ensemble music for the chamber remained particularly conservative: only a few works such as the polyphonic fantasias of Métru survive, although the fantasias of Le Jeune and Du Caurroy were probably also still being performed. Thus it was to the air de cour that the great composers of the day (those generally associated with the musique de la chambre) turned their attention. Based on models from the late sixteenth century (most notably Le Roy’s 1571 collection Livre d’airs de cour, which set poetry by Ronsard and others), the air de cour set strophic ‘courtly’ poetry to a simple and singable melody (the air). Like the sixteenth-century models, the air under Louis XIII remained essentially a polyphonic genre, with versions for solo voice and lute intabulation appearing only after the polyphonic original (generally four or five voices with or without lute accompaniment).

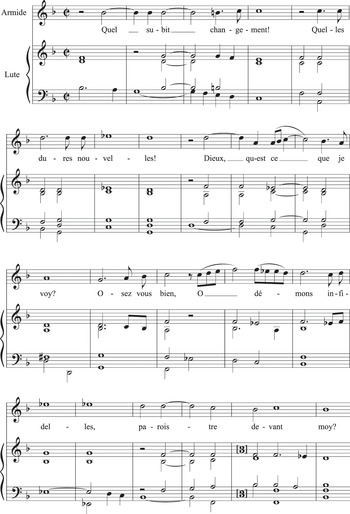

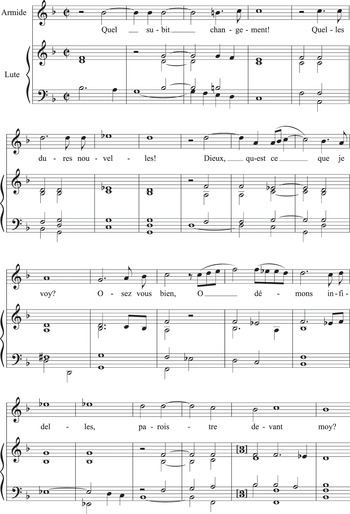

The most important composer of the early years of Louis’s reign, Guédron, published five volumes of airs for four and five voices (Ballard, 1602–20).9 Guédron’s earliest airs (setting poetry by contemporary poets such as Du Perron, Malherbe and Durand) remained influenced by musique mesurée: while their rhythmic motion was often restricted to homophonic crotchets and minims, their melodies eschewed all melisma and virtuosity in an effort to declaim the poetry clearly and correctly. By the time of Guédron’s later collections, however, the influence of musique mesurée had waned. Instead, a sensitive and supple approach was taken to text setting, and a complex patchwork of scoring was used to highlight the text: one line of text for treble and bass, the next for lower parts only, the next for upper two only and so on. Later volumes also introduced a particularly declamatory style, the récit, in which the line between theatrical declamation and singing was blurred. Sometimes unaccompanied, these works were generally composed for ballets de cour before being made available to a wider audience in the published volume (see Example 4.1).

Example 4.1 Authors’ transcription of a Guédron récit from the Ballet de la délivrance de Renaud

The better-known and more widely distributed versions of Guédron’s airs de cour appeared in a parallel series of publications from the Ballard house, the Airs de différents autheurs mis en tablature de luth (16 vols, Ballard, 1608–43: Guédron’s works appear in vols III–VI, 1611–15), a series in which (like the 1571 publication) the melodic voice was reproduced, accompanied by an intabulation for lute (at this time by Gabriel Bataille) of the other voices. In an era in which the song for solo voice and continuo (or monody) was becoming prevalent in Italy, these more ‘modern’ versions found a receptive audience among the French elite; also more practical and convenient, they are the arrangements generally heard today.

After Guédron’s death, the most widely renowned composer of airs de cour, and probably the most influential composer of Louis XIII’s reign, was his son-in-law Antoine Boësset. Like Guédron’s, Boësset’s airs were originally composed for four to five voices (9 vols, Ballard, 1617–42), but from 1632 onwards, a basso continuo or basse-continue accompaniment began to be specified for some works. More widely disseminated were the versions for solo voice and lute intabulation, these versions being arranged by Bataille and then Boësset himself (9 vols, Ballard, 1614–43). Boësset’s airs (now setting formulaic texts by minor and largely anonymous poets) no longer exhibited any obvious musique mesurée influence or the exaggerated declamatory style of some Guédron. Instead, he took Guédron’s ‘patchwork’ approach to scoring but developed an easy melodic style (now much more frequently moving in triple time), which remained influential throughout the remainder of the century. The critic Le Cerf de la Viéville (1674–1707) in the early eighteenth century distinguished Antoine from his son Jean-Baptiste thus: ‘The Boësset you knew was the younger, a very mediocre musician. Everything good written under this name is by his father, whom we call the “old” Boësset, and whom we have always talked about. It was the father Lully esteemed, a man whose memory will be immortal because of his famous air Si c’est un crime de l’aimer, etc.’10 This simple ‘classical’ style was subject to a practice of elaborate ornamentation and diminution, as documented by the principal music theorist of the period (and one of its foremost mathematicians), Marin Mersenne.11 Although the French style avoided technical display, the diminutions on Boësset’s air N’esperez plus mes yeux (by Boësset himself and Le Bailly, his colleague at court) represent the height of veiled virtuosity, at the same time retaining the French interest in correct declamation.

Music under Louis XIV

Under Louis XIV, music and music patronage, building on the model of Louis XIII, set a standard for magnificence that was emulated throughout Europe. On the death of Louis XIII in 1643, France entered into the regency of the queen mother, Anne of Austria, who ruled with the aid of her premier ministre, the Italian Cardinal Mazarin. As a young man, Louis XIV showed little interest in the government of the kingdom, devoting himself instead to his education in the courtly arts. Like his father, he became quite proficient as a dancer and instrumentalist, but unlike Louis XIII, who excelled on the lute, Louis XIV chose the guitar – formerly associated with the lower classes – as his primary instrument, which contributed to a new acceptance for that instrument among the aristocracy. With the death of the cardinal in 1661, Louis unexpectedly chose to reign alone rather than appointing another premier ministre. From that date forward he took an active interest in the government of the kingdom and in the creation of a body of music that would reflect his glory as monarch and his patronage of the artistic production of Europe’s pre-eminent court.12

Music under Louis XIV may be divided into periods of emphasis according to the king’s shifting musical interests. During the 1650s and 1660s, Louis himself danced in the court ballet, to which he committed an enormous amount of time, energy and financial resources. In the 1670s and 1680s, after his retirement as a dancer, emphasis shifted to the creation of a uniquely French version of opera called the tragédie en musique or tragédie lyrique. In his late years, under the influence of his devout second wife, Françoise de Maintenon, the king’s increasing religious devotion entailed a further shift away from the theatre and towards sacred music.

Until the death of Lully in 1687, musical taste in Paris and the rest of France was influenced by that of the king and the court. Chamber music was developed in the salon in imitation of the elegance and refinement of a courtly style. Ceremonial music, which continued at court and in the king’s public entrances and other royal celebrations, also left its stamp on the adulatory prologues and heroic plots of French opera. In the last two decades of the century, the centre of music production began to shift away from Versailles to the urban arena and commercial market. From that time onwards, musical taste tended more to be imported from Paris, rather than set by the court, in a process that would only intensify in later years. The development of the opéra-ballet and the enthusiastic importation of the Italian style around the turn of the century defined a clear demarcation between the conservative taste of the king and a developing public taste for a more modern style.

Secular music

The most illustrious composer of France under Louis XIV, Lully, came to France from his native Italy to serve as a garçon de chambre in the household of Louis’s cousin, the duchesse de Montpensier (La Grande Mademoiselle). When she was exiled for her participation in a series of civil wars (the wars of the Fronde), Lully entered the service of the king as a violinist and dancer in the court ballet, and in 1653 he was appointed compositeur de la musique instrumentale. Not long after this he became the leader of the Petits Violons, an instrumental group in the king’s personal service that augmented the official orchestra known as the Vingt-Quatre Violons du Roi. In 1661 Lully was named surintendant de la musique de la chambre du roi, a post that effectively assured his control over the development of French music for the next quarter of a century. In the court ballet, Lully developed a style that, assimilated from a variety of elements including the music of his native country, came to be perceived as uniquely French. Dance music for the ballet was mostly freely composed, but also referenced a seventeenth-century ballroom repertoire including the bourrée, minuet, sarabande, gavotte, canaries and courante. Vocal récits, used atmospherically rather than dramatically, opened the major parts (parties) of the ballet and also appeared within many of its entrées. Lully’s first fully developed example of what later became known as the French overture, with its pompous dotted rhythms combined with a lively Italian fugato, was introduced as early as the Ballet d’Alcidiane of 1657. With the expansion of its vocal portions and the addition of large choruses of monarchical praise in the 1660s, the music of the court ballet had a strong influence on the tragédie en musique of the following decade. Except for isolated productions for special occasions, the court ballet virtually ended with the retirement of its librettist, Isaac de Benserade, in 1669 and with the decision of Louis XIV to give up dancing around that time. The French affinity for the ballet continued, however, in the divertissements of the later tragédie en musique and opéra-ballet.13

Parallel to the development of the court ballet of the 1660s, Lully collaborated with the comic playwright Molière to develop the comédie-ballet, a genre that had made its debut in Les fâcheux by Molière, with music and choreography by the ballet master Pierre Beauchamps. Created as a means of allowing the actors of the play to rest between scenes, the danced portions of the comédie-ballet, far from mere interludes, are tightly integrated into the comic action. The comedy or ‘burlesque’ style in this genre grows directly out of the court ballet’s burlesque scenes, which are designed to set off the noble character of the court through the contrasting ridicule of foreigners, the bourgeoisie and persons in the professions. The comédie-ballet makes no such class distinctions, targeting everyone including the nobility and at times even the king. The comédie-ballets of Molière and Lully were performed at court and at Molière’s theatre in Paris; after Lully left the collaboration with Molière to take over the Opéra, the playwright collaborated with the composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704) in a final work entitled Le malade imaginaire (1673).14

Lully’s father-in-law, Michel Lambert (c. 1610–96), served, like Lully, as both a dancer and musician in the court ballet. Lambert, along with his contemporaries Jean-Baptiste Boësset (1614–85, son of Antoine Boësset), Bénigne de Bacilly (c. 1625–90) and Sébastien Le Camus (c. 1610–c. 1677), brought the air sérieux to its apogee. As a singer and lutenist, Lambert was famous for his nuanced text-setting, his expressiveness and the delicate filigree of his doubles, the ornamented strophes following the first strophe of the air. With his sister-in-law, the well-known soprano Hilaire Dupuis, Lambert performed both at court and in the salons of the précieuses, enclaves of society women who sought to transfer the appurtenances of an elegant and noble life from the court to Parisian society.15

Instrumental chamber music was also very much a part of the life of these salon gatherings. The late seventeenth century represented a period of decline for the lute, which at mid-century was already beginning to be replaced by the harpsichord. (The bass instrument of the lute family, known as the théorbe or theorbo, had greater carrying power and remained in use well into the eighteenth century, especially as an accompanying instrument.) The lute’s vaporous, improvisatory style, filled with ornaments, arpeggios and unexpected turns, strongly influenced the first generation of harpsichord composers, including Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (c. 1602–72), Louis Couperin (c. 1626–61) and Jean-Henri D’Anglebert (1629–91). Although linked to the dance repertoire, dances composed for harpsichord, like those for lute, tended towards extreme stylisation. Allemandes and gigues commonly incorporated points of imitation, while the courante could be quite rhythmically complex and irregular in phrase structure. As in the ballet, chaconnes and passacailles provided the opportunity for larger architectural structures. The unmeasured prelude, especially as exemplified by Louis Couperin, represents a richly textured, deeply expressive statement of an improvisatory nature. Much of the lute and early harpsichord literature had an effect of discontinuity and timelessness, undermining any clear sense of tonal direction or rhythmic drive. This aesthetic suited the salon, which like the court valued sensuousness and pleasure for their own sake, suitable for passing leisure time without pressing goals or the need for forceful or pointed rhetoric.16

Private concerts had arisen at least as early as the sixteenth century. In the seventeenth century they became a requisite component of social life not only at court, but also in the homes of the lesser nobility and bourgeoisie. Parisian concert life is described in the journals of Madeleine de Scudéry, La Grande Mademoiselle, Madame de Sévigné and others, as well as in Jean Loret’s Muze historique and in the fashionable periodical Le Mercure galant. Musicians such as the bass viol player Jean de Sainte-Colombe (fl. 1670–1700) and the lutenist Jacques Gallot, as well as Lambert and Dupuis, gave concerts in their homes on a regular basis. In her early career, the harpsichordist and composer Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665–1729) was associated with the court; in the last decades of the century she gave concerts to great acclaim in her home and throughout Paris. Viols and lutes, the staple instruments of chamber-music performance in the early seventeenth century, continued in use through the late seventeenth century and into the eighteenth, giving way to the violin family much later than in Italy. Important viol composers included Sainte-Colombe, Marin Marais (1656–1728) and Antoine Forqueray (1672–1745). In early seventeenth-century France the violin, associated with open-air performance and with dance instruction, was rejected as an instrument for chamber music. In the late seventeenth century violins, along with flutes, recorders and oboes, gradually began to replace viols as treble instruments.17

The main forms of instrumental chamber and ensemble music in seventeenth-century France were the overture and dance suite, reflecting the continuing influence of dance and the ballet. The last decade of the century saw an influx of Italian instrumental music in the form of solo and trio sonatas (respectively for one and two solo instruments with basse-continue) and concertos (either solo concertos for solo and orchestra or concerti grossi for multiple soloists). The genres of sonata and concerto (called sonade and concert in France) were not clearly separated, as sonatas were often expanded to include more than one player to a part, and orchestral pieces could be performed by soloists as well. François Couperin incorporated Italian elements through both absorption and juxtaposition. These elements included more idiomatic writing, contrapuntal textures, driving rhythms, Italian dances, virtuosity and more directional harmonies defined by devices such as the circle of fifths. Several of Couperin’s early sonatas were included in a later collection, Les nations: sonades et suites de simphonies en trio (1726). His fourteen concerts were divided into two groups. The first four of these, entitled Concerts royaux, were performed at Versailles in Louis XIV’s last years (1714–15, published 1722). While incorporating some Italian elements, they mainly adhered to the king’s preference for a French style. The slightly later Les goûts réunis, ou Nouveaux concerts (1724) reflect a deeper assimilation of the Italian style associated with the Regency. At the end of this collection, Couperin appended his famous Le Parnasse, ou L’apothéose de Corelli, a tribute to Corelli and Italian music; a parallel Concert instrumental sous le titre d’Apothéose composé à la mémoire immortelle de l’incomparable Monsieur de Lully, emphasising French elements, followed in 1725.18

An Italian vocal style, in the form of the secular cantata, also invaded France and influenced French music around the turn of the century. Examples of early French cantates include those by Jean-Baptiste Morin (1677–1745), Nicolas Bernier (1665–1734) and Jean-Baptiste Stuck (1680–1755). In his first book of cantates (1708), André Campra (1660–1744) claimed to have mixed French ‘gentleness’ with Italian ‘vivacity’. Campra’s second and third books (1714, 1728) began to incorporate a more operatic idiom. This was taken up by Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1676–1749), whose five books of cantates (1710–26) were particularly revered. The famous quarrels over French and Italian music, initiated in François Raguenet’s Paralèle des italiens et des françois, en ce qui regarde la musique et les opéras in 1702 and answered by Le Cerf de la Viéville’s Comparaison de la musique italienne et de la musique françoise (1704–6), represented the larger debate between an eighteenth-century cosmopolitan modernism as it challenged traditional modes of thought in France.19

Sacred music

Sacred music during Louis XIV’s reign was still characterised by a clear division between the conservative polyphony that continued to be composed into the eighteenth century for secular parish churches and the cathedral of Notre-Dame (composers such as François Cosset, c. 1610–after 1664, Jean Mignon, c. 1640–c. 1707, and Campra) and the more progressive music for monastic churches (such as the church of the Feuillants, Notre-Dame des Victoires and the Jesuits of Saint-Louis), noble households (including Marie de Lorraine, known as Mademoiselle de Guise) and the Chapelle Royale, which in contrast to earlier in the century was now in the vanguard of sacred music.

The most important figure of the early years of Louis XIV’s reign was Henry Du Mont (c. 1610–84), a composer trained in a more progressive style in the Low Countries around Liège and Maastricht.20 Although the devotional music of the musique de la chambre and Boësset’s liturgical works for Montmartre had made use of the basse-continue, Du Mont’s arrival in Paris, and his first publication, the Cantica sacra of 1652 (a publication intended for performance by nuns, according to Du Mont, even though the works are mainly scored for mixed voices), introduced other Italian elements into French sacred music. Du Mont used a much more expressive and affective style than Boësset: it included dramatic dialogues, independent instrumental parts and a figured basse-continue.

After the stagnation under Louis XIII and the disruption of the Fronde (1648–53), the Chapelle Royale underwent something of a renaissance in the 1650s. A new chapel was built at the Louvre in 1655–9, the Chapelle de Notre-Dame de la Paix (until then the court had used the chapel of the Petit Bourbon, the church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois or various small chapels in the Louvre). Around the same time the sous-maîtreJean Veillot (d. 1662) began to compose on a larger scale than his predecessors, providing the occasional works Alleluia, o filii and Sacris solemnis (1659), the first to use independent ‘symphonies’ in addition to two choirs. (Otherwise, virtually no music survives from this period.) But it was with the appointment of Du Mont as Veillot’s successor at the Chapelle Royale, in 1663, that the era of the systematic composition of grands motets was inaugurated. Formalising a practice dating from the late sixteenth century, in which the singers of the musique de la chambre collaborated with the singers of the Chapelle Royale at important ceremonial events, Du Mont ‘created’ the grand motet, in which a choir of soloists (the petit choeur), a larger choir (the grand choeur) and an orchestra (the Violons du Roi) combined to set a text (either neo-Latin poetry or a psalm) verse by verse in a combination of solos, ensembles, tuttis and instrumental interludes.21 The grand motet was then performed in conjunction with a petit motet (for the elevation) and a Domine salvum fac regem (to conclude) as part of the celebration of Low Mass, a rite in which a priest spoke the liturgy to himself while the king listened to the music. Lully contributed to the genre only occasionally; his use of orchestra and choir remained less sophisticated and varied than that of Du Mont, though many of his works are more dramatic. After the court moved permanently to Versailles and after Du Mont’s death in 1684, Du Mont’s successor Michel-Richard de Lalande (1657–1726) continued the tradition, expanding the motet into a long work with individual ‘numbers’ and more advanced scoring and compositional techniques. Even so, the basic principle and function of the grand motet remained the same well into the middle of the eighteenth century.22

Elsewhere in Paris the petit motet for soloists and basse-continue flourished. While figures such as Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers (c. 1632–1714), André Raison (before 1650–1719) and Nicolas Lebègue (c. 1631–1702) published collections for the expanding market of monastic institutions, François Couperin provided few-voiced settings of Holy Week Lamentations for the same market. Couperin also contributed short organ pieces (versets) to the genre of the ‘organ Mass’, which could be substituted for portions of the liturgy. Active in several different circles, the Italian-trained Charpentier was at the forefront of musical developments, bringing the Italian oratorio to France as the histoire sacrée and producing grands motets for the Sainte-Chapelle and the Jesuit church of Saint-Louis. More generally, the reforms of the Neo-Gallican movement (primarily concerned with asserting French independence from Rome) led to the composition of new chants and modifications to the liturgy, a trend that would continue apace throughout the eighteenth century.

Ideology, aesthetics, society

In the seventeenth century a number of royal academies were formed with the aim of centralising and controlling the arts. The Académie Royale de Musique was founded in 1669, following the models of the Académie Française (founded 1634), the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (1648) and the Académie Royale de Danse (1661). Lully is well known as the director of the Opéra (as the Académie Royale de Musique was informally known), for which, with the king’s support, he wrested the monopoly or privilège from Pierre Perrin in 1672. With his librettist Philippe Quinault, Lully produced a series of tragédies en musique that, both through the overt praise contained in their prologues and through the glorious heroism of their plots, served as a keystone of monarchical representation during the 1660s and 1670s, when Louis XIV was at the height of his power.

Lully and a number of his fellow artists, while contributing to an ideology and aesthetic of sovereign power, also belonged to a loosely knit community of French libertines, a group of individuals who combined in varying degrees transgressive sexual behaviour with political free thought. In the last years of his life (1685–7), Lully fell into disgrace with the king, at least in part because of his libertine behaviour. During these years he was patronised by the duc de Vendôme and his brother Philippe, leaders of a community lying outside police jurisdiction, within and around an old castle known as the Temple.23Lully’s final stage works, Acis et Galathée (1687) and Achilles et Polixène (1687, completed by Pascal Collasse), were settings of librettos by Jean de Campistron, a playwright who was also part of this community. These works, along with two operas by Lully’s sons, Jean and Jean-Louis, may be read as a stringent critique of Louis XIV in the late years of his reign. Treating themes of tyranny, victimisation of the artist and the sacrifice of the arts to an overweening militarism, they use an imagery of the abandoned theatre and deprived audiences as metaphors for a crisis in the arts in the last decades of the century. Similarly, the Muses appear in Lully’s last, uncompleted opera, as well as in several operas of his successors, as the voice of Louis’s artists, complaining that the ‘greatest hero’ has forgotten their games and pleasures. A similar critique, cast in a more utopian tone of optimism, characterises the new genre of the opéra-ballet developed by Campra and his librettists Antoine Houdar de La Motte and Antoine Danchet at the turn of the century. Campra’s opéra-ballet Les Muses (1703) may be read as a satire on a court ballet of Louis XIV, Le ballet des Muses (1666). It also represents a tribute to the genres of comedy and satire itself over the outworn gestures of monarchical praise. Likewise, Les fêtes vénitiennes presents the arts of a public, libertine Paris under the transparent mask of Venetian carnival. The music of these opéras-ballets, like their dances, light-hearted scenarios and Italianate idiom, exemplifies the galanterie, hedonistic spirit and anti-authoritarianism that audiences craved during the dismal late years of the Sun King.24

Lully, his sons and Campra all had connections with Louis, the Dauphin of France (‘le Grand Dauphin’), who patronised and protected Lully during the period of his disgrace. During these years a cabal arose around the dauphin, later known as the ‘cabal de Vendôme’ because of the leadership of that libertine duke. The Grand Dauphin, who attended the Paris Opéra on a regular basis (to the extent that it became a kind of counter-court), was favoured by libertines and artists because of his hedonism and love of the arts, particularly opera. The French fascination with italianisme was not shared by the king. Recent scholarship has shown, however, that an Italianate repertoire was performed at court in the chambers of the Grand Dauphin.25

It can be argued that despite its importance for French art and identity, a seventeenth-century aesthetic of sovereign power, reflected in a literary classicism paralleling the apex of the reign of Louis XIV, merely obscured rather than effaced a more long-standing aesthetic of galanterie equated with an aristocratic taste. It is true that ceremonial music, associated with conquest and glory through large choruses, heavy instrumentation, trumpet fanfares, drumrolls and other military motifs, branded the European imagination with the grandeur of Louis XIII and Louis XIV. At the same time, another form of power could be discerned in the king’s ability to make of the court a ‘society of pleasures’ dependent on his patronage. In the late seventeenth century, the high nobility (les grands seigneurs), largely divested of their former feudal powers, were constrained to live at court and to fashion a new identity from the pleasures it afforded. The king traditionally partook of these diversions, but as Louis XIV aged he withdrew from the social life of the court for a variety of reasons, including illness, a turn to religious devotion, military losses, a worsening economy and continuing tensions with his nobility. If the king was associated in his late years with grandeur, his nobility was associated with the quality of galanterie, a term evoking games of love, satiric wit and chic fashionability. This quality was absorbed by the bourgeoisie, who were eager to develop a taste for music, dance and the other arts as the reflection of an enhanced social status accompanying the wealth that had begun to accrue to their class.

The style galant, codified by German theorists in the eighteenth century, had its roots in the delicate ornamentation of the air de cour and the lute and harpsichord repertoire, as well as in the more brilliant coloratura of Italian opera. The qualities of galanterie and a light-hearted joie de vivre pervade the harpsichord music as well as much of the chamber music of Couperin. Like Campra’s opéras-ballets, these works shun the profound, majestic and grand for the topical, satirical and fashionable. The insouciant spirit of galanterie paralleled more serious philosophies of pleasure. In the early seventeenth century a group known as libertins érudits espoused a doctrine derived from the writings of Epicurus, which had been transmitted by the Roman philosopher Lucretius. The libertine movement tended to go underground in the late seventeenth century, though its tenets, overlapping with Epicureanism, were encoded in various doctrines of love as most particularly embodied in the goddess Venus.26

These ideas challenged the emphasis on reason that had come to France via the rediscovery of Aristotle in late Renaissance Italy, which thrived in the local soil of Cartesian rationalism and political absolutism. Another challenge came from across the Channel, in England, where John Locke and Thomas Hobbes formulated theories of cognition through the senses. In the early eighteenth century, French philosophers began to eke out a place for sensory perception in a field that around mid-century would come to be known as aesthetics. Jean-Pierre de Crousaz, a follower of Descartes, formulated a system in which the senses could function without disrupting reason. The abbé Dubos, who went the furthest in developing an aesthetic dependent on the senses, also developed the concept of ‘the sixth sense’, a direct physical apprehension of beauty circumventing reason altogether. Instead of imitating Descartes’s ‘passions of the soul’, the arts were now seen as setting in motion more delicate sensibilities, with the aim of touching lightly rather than moving forcibly. This appeal to the senses allowed the appreciation of the arts to bypass reason, so that the message of the text was now overshadowed by the direct apprehension of musical sound. This aesthetic, then, opened the way for a full appreciation of instrumental music. Finally, Dubos’s connection of this sixth sense with good taste, bon goût, illustrates the change that had come about since the height of seventeenth-century classicism, which had equated good taste with reason and the rules. Dubos in effect allowed the substitution of a relative taste, in which an individual could manifest preferences according to personal sensitivities. All these philosophies, in supporting a relative taste at the expense of a universal standard, undermined the authority of the academies, and indirectly the power of the king, to set the standards by which art should be created and judged.27

Notes

1 The distinctive character of French music during this century is described in probably the best survey of the seventeenth century: , French Baroque Music from Beaujoyeulx to Rameau, rev. and expanded edn (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1997).

2 On the querelles over French and Italian music, see , The Origins of Modern Musical Criticism: French and Italian Music, 1600–1750 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1981); and , ‘The honnête homme as music critic: taste, rhetoric, and politesse in the 17th-century reception of Italian music’, Journal of Musicology, 20 (2003), 3–44.

3 For important cultural background and context, see , Music, Discipline, and Arms in Early Modern France (University of Chicago Press, 2005).

4 , Le cérémonial françois (Paris: Cramoisy, 1649), 998.

5 Reference GodefroyIbid., 72.

6 The most exhaustive general description of sacred music during the century remains , La musique réligieuse en France du Concile de Trente à 1804 (Paris: Société Française de Musicologie, 1993). For a more detailed discussion of specific repertoires under Louis XIII, see , Sacred Repertories in Paris under Louis XIII: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Vma rés. 571 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009).

7 See , ‘Collaborations between the Musique de la Chambre and the Musique de la Chapelle at the court of Louis XIII: Nicolas Formé’s Missa Æternae Henrici Magni (1638) and the rise of the grand motet’, Early Music, 38 (2010), 369–86.

8 See , ‘Antoine Boësset’s sacred music for the royal abbey of Montmartre: newly identified polyphony and plain-chant musical from the “Deslauriers” manuscript (F-Pn Vma ms. rés. 571)’, Revue de musicologie, 91 (2005), 321–67.

9 The most detailed study of the air de cour is , L’air de cour en France, 1571–1655 (Liège: Mardaga, 1991). See also , Music and the Language of Love: Seventeenth-Century French Airs (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011).

10 , Comparaison de la musique italienne et de la musique françoise, 3 vols (1704–6; repr. Geneva: Minkoff, 1972), vol. II, 123–4.

11 , ‘Traitez des consonances, des dissonances, des genres, des modes, & de la composition’, in Harmonie universelle (Paris: Cramoisy, 1636), 411–15.

12 The standard work on music at Louis XIV’s court is , Music in the Service of the King: France in the Seventeenth Century (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1973). On Louis XIV as a musician, see , Louis XIV, artiste (Paris: Payot, 1999).

13 An excellent recent study of the life and works of Lully is , Jean-Baptiste Lully (Paris: Fayard, 2002).

14 On the comédie-ballet, see , Music, Dance, and Laughter: Comic Creation in Molière’s Comedy-Ballets, PFSCL-Biblio, 17 88 (Tübingen, 1995).

15 On Lambert, see , L’art de bien chanter: Michel Lambert, 1610–1696 (Paris: Société Française de Musicologie, 1999).

16 On the ‘timeless’ quality of music in this period, see , ‘Temporality and ideology: qualities of motion in seventeenth-century France’, ECHO: A Music-Centered Journal, 2 (2000), www.humnet.ucla.edu/echo (accessed 22 May 2014).

17 On concert life in early modern France, a classic text is , Les concerts en France sous l’ancien régime (Paris: Fischbacher, 1900).

18 On Couperin, see , François Couperin, trans. (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1990).

19 On Campra, see , André Campra, 1660–1744: étude biographique et musicologique (Arles: Actes Sud, 1995). On the quarrels over French and Italian Music, see Cowart, The Origins of Modern Musical Criticism.

20 For an important study of Du Mont and sacred music in the middle years of the century see , Un musicien en France au XVIIe siècle: Henry Du Mont (Paris: Mercure de France, 1906).

21 For a number of contributions to the early history of the grand motet, see the essays in (ed.), Jean-Baptiste Lully and the Music of the French Baroque: Essays in Honor of James R. Anthony (Cambridge University Press, 1989); and in and (eds), Actes du Colloque International de Musicologie sur le grand motet français, 1663–1792 (Paris: Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1986).

22 For an account of the development of the grand motet, see Anthony, French Baroque Music, 216–46, 247–69; see also , Le motet à grand choeur (1660–1792): gloria in Gallia Deo (Paris: Fayard, 2009).

23 , The Triumph of Pleasure: Louis XIV and the Politics of Spectacle (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 139–44.

24 On the politics of the ballet and opera in the era of Louis XIV, see Reference Cowartibid.

25 , ‘The “Cabale du Dauphin”, Campra, and Italian comedy: the courtly politics of musical patronage around 1700’, Music and Letters, 86 (2005), 380–413.

26 Cowart, The Triumph of Pleasure, 51–4.

27 On musical aesthetics in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, see , Aesthetics of Opera in the Ancien Régime, 1647–1785 (Cambridge University Press, 2002); and (ed.), French Musical Thought, 1600–1800 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1989).