2 Cathedral and court: music under the late Capetian and Valois kings, to Louis XI

The period extending from the end of the twelfth century to the middle of the fifteenth marks the highpoint of French influence on European music. French composers contributed brilliantly to contemporary genres after 1450, but it was in the earlier period that northern French composers steered a path forward in an environment that paradoxically admitted both constant renewal – a normal participatory music-making – and an aesthetic of authority and fixity, the legacy of Carolingian liturgical chant. The coordination of active musical creativity with constructivist techniques of polyphonic elaboration in rational synthesis (is that what ‘French’ is?) created the fundamental profile of what we recognise as ‘Western’ music in the first place.

The Notre-Dame school

In the years from 1163 to 1250, a new cathedral of Notre-Dame was built on the central island in Paris. Remarkably, the construction paralleled the development of a new polyphonic music, the first to be regulated by metrical rhythm. Much of what we know about the so-called Notre-Dame school of composers comes from a music treatise penned perhaps in the 1270s by ‘Anonymous IV’, an unnamed English student who had once studied in Paris.1 He records the achievements of two composers, Leonin, organista, author of a great book (magnus liber) of organa, and Perotin, discantor, who made ‘better clausulae’ than Leonin.

Extant musical manuscripts confirm that the first great achievement of the Notre-Dame composers lay in a collection of two-part organa (settings of the Gregorian cantus firmus plus one added voice, the duplum). For the most part, three plainchant genres were subject to elaboration: the Gradual and Alleluia from the Mass, and the Great Responsory from the Divine Office. As monophony, these are ‘responsorial’ chants, alternating virtuosic solo passages with unison choral passages. In the new organa, segments originally delivered by the soloist provide the cantus firmus, as another soloist sings new music above. Segments originally delivered by the choir remained the domain of the choir.

Theorists distinguished two styles of polyphony, organum purum and discant. Broadly speaking, the two styles respond to two patterns of text declamation in the original plainchant. Segments of syllabic text were set in organum purum, sustaining the individual pitches of the cantus firmus in the long tones of the tenor, above which the added voice would rhapsodise freely. Melismatic segments were set in faster-moving discant, one or two notes in counterpoint against the cantus firmus. At first probably unmeasured, by around 1200 discant segments exhibited metrical rhythm based on a regular pulse. In these isolated discant segments of Leonin’s two-part organa, a fateful step towards a fundamental prerequisite of Western music occurs: the ability to control polyphonic voices in rhythm. Examples 2.1a and b illustrate excerpts from a Notre-Dame organum purum and discant, extracted from the organum Alleluia Nativitas for the Nativity of the Virgin.2

Example 2.1a Alleluia Nativitas, organum purum (beginning) by Leonin(?)

Example 2.1b Alleluia Nativitas, discant on ‘Ex semine’ (beginning) by Leonin(?)

Craig Wright has shown that Leonin may be identified with a canon at the cathedral of Notre-Dame who lived from around 1135 to after 1201.3Anonymous IV credits Leonin as the best organista, a specialist in organum purum. Does he mean a skilled singer capable of negotiating a new work as a performance unfolds or a figure closer to what we would label a ‘composer’, someone who literally puts together a work, which is then notated and transmitted as an entity? The question is currently debated.4

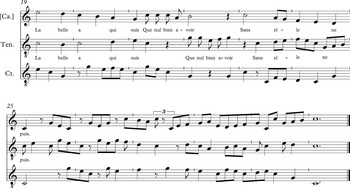

Anonymous IV has much more to say about Perotin (d. c. 1238?). First, his superior skill as discantor produced better clausulae (phrases), discant segments that can replace corresponding segments in Leonin’s settings. Such ‘substitute clausulae’ utilise the same snippet of chant, but exhibit increasing rhythmic sophistication. Our most complete source of music of the Notre-Dame school, the Florence Codex, finished in 1248 for the dedication of Louis IX’s Sainte-Chapelle, has a fascicle of no fewer than 462 of these two-voice substitute discant segments.5Example 2.1c illustrates a modernised reworking of Example 2.1b, presumably by Perotin.6

Example 2.1c Alleluia Nativitas, discant on ‘Ex semine’ (beginning) by Perotin(?)

Unlike most chansonniers of the troubadours and trouvères, manuscripts of polyphony in this period lack composer attributions, but thanks to Anonymous IV seven specific works preserved in the extant manuscripts can be attributed to Perotin. Two highly sophisticated four-part works can even be dated: the Viderunt (Gradual for the third Christmas Mass) of 1198 and the Sederunt (Gradual for St Stephen’s Day) of 1199. Three of the attributions involve a second genre cultivated by the Notre-Dame school, the conductus, a freely composed setting of strophic Latin poetry in one to three voices. Several conductus texts can be attributed to Philip the Chancellor (b. c. 1160–70; d. 1236), a direct contemporary of Perotin, and in fact Beata viscera, a monophonic conductus, is a collaboration between them.

The early motet

Notre-Dame organa and conductus soon receded from compositional history, but a third genre, the motet, became the crucible for all advances in polyphony for at least the next 125 years. Unfortunately, our informant Anonymous IV is completely silent on its origins. The usual musicological narrative links the earliest motets to the active development of discant in the early thirteenth century: the initial step that created the motet was the application of a poetic text to the most modern rhythmised music of the time, pre-existing discant clausulae.

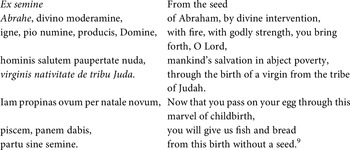

Consider again the Alleluia for the Nativity of the Virgin (Example 2.1a). Our earliest source, W1 (c. 1230), transmits a rudimentary discant setting the words ex semine (Example 2.1b), modernised in the Florence Codex (Example 2.1c).7 Indeed this modernised clausula saw double duty in a work that Anonymous IV attributed to Perotin, the three-voice Alleluia Nativitas, with the addition of a triplum voice. Both as a two- and three-voice form we can count this segment one of the ‘better clausulae’ composed by Perotin. The text, probably by Philip the Chancellor, fits Perotin’s music and makes the segment into a motet (Example 2.2).8

Example 2.2 Perotin(?) and Philip the Chancellor(?), motet Ex semine Abrahe/Ex semine

In explicating the mysteries of the birth of the Virgin Mary, Philip framed his text with the words of the cantus firmus, and skilfully incorporated bits of text from elsewhere in the Alleluia verse (these connections are set in italic type). Note that the poetic impulse behind the motet has a different emphasis from that of a purely occasional conductus text. Because of its ultimate origins in liturgical organum, the motet’s text glosses the original liturgical context of the parent organum; indeed, it is possible that early motets, like tropes, were used liturgically.

Besides responding to the liturgical moment, a poet faced a special challenge, for it happens that the discant clausula was not a kind of music suited to traditional poetic forms, which build strophes out of regular patterns of rhyme and syllable count. The melody of the cantus firmus is usually broken into groups of two or three notes, separated by rests and set in rhythmic ostinato, as in Example 2.2. Phrases in the duplum voice play off the recurring patterns, now bridging across rests, now pausing with the tenor. The text given above divides lines according to their distribution across each statement of the five-note ostinato. One might also print the text observing rhymes, which produces a flood of irregular short lines: neither option produces an orthodox piece of poetry, because musical exigencies generated ad hoc poetic designs.

Thomas Payne argues that the creation of the motet was a product of collaboration between Perotin and Philip the Chancellor: its conceptual beginnings lie in surviving organum prosulas (texting just the duplum of the four-voice Viderunt and Sederunt) whose texts can be ascribed to Philip.10 One might push Payne’s thesis a step further and seek the earliest notation of rhythm itself in the application of text, for this simple means was available well before modal rhythmic notation, first attested in W1.11 The motet texts themselves suggest musical rhythm, a sing-song that results from the alternation of strong and weak word accents organised into lines of specific syllable count, and from the chiming of the frequent rhymes. The texted form of the duplum voice of Perotin’s Viderunt is thus a surviving remnant of compositional process: each phrase of text preserves the rhythms of a phrase of music right from the start – a true collaboration of a skilled musician and a skilled poet. The other two voices, the triplum and quadruplum, did not require separate notation, for they operated closely in tandem with the texted duplum through voice exchange, and could apply the same words. Guided by Philip’s text, performers learned Perotin’s music. Such a scenario allows us to imagine the construction of Perotin’s organum as a ‘work’, even before an efficient notation was devised to fix it onto parchment.

The motet in the mid-thirteenth century

Motets of the early and middle years of the thirteenth century are protean works, products of collective and collaborative creative efforts. The ‘case history’ of motets based on Perotin’s Ex semineclausula in its two forms, a two-voice discant updating Leonin’s Alleluia Nativitas and a three-voice discant taking its proper place in Perotin’s new three-voice Alleluia Nativitas, can serve as a simple example. We have seen that Philip’s poem Ex semine Abrahe was key to the initial fixing of the rhythms of the new work, and thus motet and clausula were interlinked from the beginning. Once the music was set, it was available for further use. For example, the three-voice version appears with a new text for the triplum, again alluding to a liturgical context by borrowing words from the parent Alleluia.12

Crucial to the explosive development of the motet was its quick acceptance of vernacular French texts. Two use Perotin’s discant as their musical source: Se j’ai amé/Ex semine and Hier main trespensis/Ex semine.13 Most often, new vernacular texts are in no way tied to the liturgical context of the tenor cantus firmus, but the tenor text may relate emblematically or ironically to the texts of the upper voices. In general, the direction of development is towards more phrase overlap between the voices than we observe in Example 2.2, a musical characteristic confirmed by poly-textuality (a separate poem for each upper voice) and different verse structures in each text. Often new music as well as new text can replace an existing voice.

Once the motet entered the world of vernacular literature, it began to participate in a highly ramified and interconnected cultural endeavour. Its polyphonic and poly-textual nature made it the ideal form for the synchronous juxtaposition of diverse materials (the French motet can draw upon the wide variety of contemporary trouvère genres, such as the gran chant, chanson de mal mariée, chanson de toile, pastourelle and rondet, as well as the ubiquitous refrain), which in turn stand in dialogue with the sacred associations of the tenor. For example, one could juxtapose a male and a female voice, or different voices that represent different sides of a single persona, or place courtly love conceits side by side with Marian adoration and with earthy pastoral high jinks.14

The French motet epitomises in miniature the most characteristic large-scale literary production of this period: the narrative with lyrical insertions (‘hybrid narrative’). Indeed, the first hybrid narrative, Jean Renart’s Roman de la rose (c. 1210?), which includes forty-six lyrics of diverse genres cited in the course of the narrative, appeared about the same time as the first French motets. The most familiar of the hybrid narratives is Le jeu de Robin et de Marion (c. 1283, seventeen refrains and chansons), a pastoral drama by Adam de la Halle (b. c. 1245–50; d. 1285–8?), working at a French outpost, the Angevin court at Naples. Integration and unity were not artistically desirable traits in this aesthetic: its essence lies in the unexpected and ingenious juxtaposition of dissimilar materials. Intertextual citations, cross-references within and between genres (especially prominent in French motets that cite refrains), can be bewilderingly complex.15

For us today the most elusive aspect of the mid-thirteenth-century motet is its social context.16 Hybrid narratives, such as Renart’s Roman de la rose, often present credible social contexts for the lyrical insertions. No one in a hybrid narrative stands up at a banquet to sing a polyphonic motet, however. The best information we have is the statement of the Norman theorist Johannes Grocheio, writing in Paris around 1300: ‘This kind of music should not be set before a lay public because they are not alert to its refinement nor are they delighted by hearing it, but [it should only be performed] before the clergy and those who look for the refinements of skills.’17 Yet the clerics, in creating works for their peers, proved themselves thoroughly conversant with the vernacular courtly-popular literary culture of the day. In the French motet, the elite clerical culture transforms ‘lewd entertainment’ into ‘spiritual performance’.18

The late thirteenth-century motet

By the end of the thirteenth century the motet had assumed a level of complexity that excluded the casual contribution of a new poem or the revision of a single musical voice, favouring instead skilled individual creators of unique works. The new diversity meant that the mensural system needed to be regularised. For a time, the old ostinato patterns of the Notre-Dame tenors held sway along with the Notre-Dame cantus firmi (cf. Example 2.2). But when a refrain with pre-existing music was incorporated into the upper voices, it meant that the tenor required more flexibility so that the tenor pitches could be adjusted as needed to fit with the refrain, and hence there was a growing urgency for the exact specification of rhythmic values. The new system of mensural notation drew upon the notational figures of Gregorian chant, utilising three traditional shapes, but now assigning them the durations of long (![]() ), breve (

), breve (![]() ) and semibreve (

) and semibreve (![]() ). A definitive and rational mensural notation was codified by the theorist Franco of Cologne around 1280.19

). A definitive and rational mensural notation was codified by the theorist Franco of Cologne around 1280.19

The late thirteenth century was a period of great experimentation. For example, the motet Mout me fu grief/Robin m’aime/Portare incorporates Marion’s well-known opening song from Adam de la Halle’s pastoral drama Jeu de Robin et de Marion as its duplum.

Maintaining the song’s original rhythms, it is the duplum’s phrase structure and irregular repeating patterns (ABaabAB, rondeau-like) that shape the overall structure of the motet, not the tenor. Yet the composer was also able to incorporate a second bit of pre-existing music, a Gregorian cantus firmus carried by the tenor.20 This was but one experiment among many.

Beginning with collective and collaborative creative efforts, the motet underwent enormous expansion in the thirteenth-century creative nexus, more and more delighting in connections that touched every sort of literary and musical creation until the emergence at the end of the century of individual works. The late thirteenth-century motet exhibits a striking variety of organisational techniques, each aiming at a new flexibility in handling long-range structural articulation that had not been possible with the short ostinatos that structured the earliest motets. In the early fourteenth century, by dint of powerful intellectual application, this quest for variety converged in a new approach, which created a concentrated and reflexive form that would overturn the old aesthetic of rupture.

The ars nova and the Roman de Fauvel

Until this point, musical rhythm had been largely based on triple metre (‘perfect time’). The potentialities of duple metre (‘imperfect time’) were first rationally worked out in the early fourteenth century. The new notation, epitomising a dawning new age of music, is a product of the ars nova, a term attested by four witnesses of around 1325. While two music-theory treatises celebrate the new developments, a third treatise and a papal document deride them. Regardless of opinion, the ars nova brought an enormous expansion to the possibilities of organising and notating rhythm, best expressed by the music theorist Johannis des Muris: ‘whatever can be sung can be written down’.21

The most important musical monument of the early ars nova is a version of theRoman de Fauvel found in only one manuscript, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fr. 146.22 It expands two earlier allegorical hybrid narratives (of 1310 and 1314) critiquing the government of King Philip IV and admonishing his heirs Louis X and Philip V. The revised Fauvel of fr. 146 (c. 1318) incorporates seventy-two miniatures as well as 169 musical insertions, including items of Gregorian chant, newly composed pseudo-Gregorian chant, conductus (some with newly composed music), motets, French refrains, ars nova chansons, lais and satirical or obscene sottes chansons.

Perhaps compiled with the patronage of a prince in the king’s council, the Roman de Fauvel gives satiric artistic expression to the discontent felt by officials of the royal chancery over a government in crisis. It is a topsy-turvy world ruled by Fauvel, a corrupt half-man-half-horse creature; here, the sort of grotesqueries formerly relegated to the margins of a manuscript have been transformed into the principal players, front and centre.23

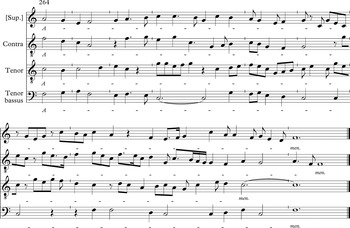

Though we lack certain proof, for no music is attributed in the manuscript, it appears likely that the young Philippe de Vitry (1291–1361) was the principal composer of new music for the Fauvel project. Arguably the most progressive musical work of the entire manuscript is his ingenious motet Garrit Gallus/In nova fert/Neuma.24 The quotation of the opening of Ovid’s Metamorphoses at the start of the duplum voice – ‘In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas’ (‘I am moved to speak of forms changed into new bodies’) – epitomises the work’s message, an expression of the political transformations that threatened society. In this motet Vitry brilliantly succeeds in transferring the essence of this message – the abstract notion of transformation – into the very core of the musical structure. He accomplishes this first through the absolutely unprecedented rhythmic design of the tenor, which transforms itself from perfect to imperfect time and back again, employing red ink for the imperfect notes and rests, an ars nova innovation (Example 2.3). (In the original notation, the note shapes form a palindrome.)

Example 2.3 Periodic structure in Philippe de Vitry(?), motet Garrit gallus/In nova fert/[Tenor]

Further, in composing out the poetic idea, Vitry drew on a new aesthetic of integration. We have seen that the Roman de Fauvel as a whole incorporates both old and new works among the musical insertions. Sometimes they stand in loose juxtaposition with the narrative, an extreme expression of thirteenth-century discontinuity, while at other times they form coherent episodes. In a performative sense, they are ‘staged’.25 The same can be said of the motet. Since its inception, the form had exhibited discontinuities: a stratification of voices and especially poly-textuality, which before had allowed for a refreshing independence in phrase lengths between the different voices. In this motet, Vitry ‘stages’ these discontinuities by coordinating the phrase lengths of both upper voices with the tenor. In Example 2.3, the rests above the tenor talea indicate the placement of rests in the duplum and triplum (there are no other rests in these voices).26 Except at the very beginning and at the very end, rests always recur at the beginning and end of the tenor segment transformed into imperfect time. By means of this ‘periodicity’, the whole musical structure is subject to transformation, not just the tenor. The poetic message is integrated into the deepest structure of the work, permeating it.

The polyphonic chanson

The motet was not the only genre revolutionised by the Roman de Fauvel. The Roman de Fauvel also turned vernacular song on its head. Although it took longer to accomplish the full measure of change in the chanson than it did in the motet, eventually the transformation set in motion in the early fourteenth century came to fruition with polyphonic chansons in ‘fixed forms’ that saw their first maturity in the 1340s in the works of Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377) and his contemporaries. Ultimately built on thirteenth-century dance genres, the three fixed forms – ballade, rondeau and virelai – each incorporate the text and music of refrain and stanza in a different pattern.

The emergence of the Machaut-style chanson involved at least three steps.27 First, the projection of rhythm through syllabic declamation at times dissolves in melismatic passages. In the monophonic fixed-form chansons inserted into the Roman de Fauvel, melismas can sever the direct tie to the sung dance, for now syllabic declamation no longer animates the rhythm; further, the melismas effectively slow the text delivery, or relegate it to isolated active patches. At the same time, melismatic melody imbues the refrain form with an unaccustomed highbrow artifice.

Another stage of development, which we can follow in early fourteenth-century hybrid narratives, lends the ballade a certain dignity stemming from long poetic lines, as had been characteristic of the most precious chansons of the trouvères. Finally, the chanson takes on polyphony, a new disjunctive polyphony rare in the chanson before Machaut. Earlier essays in the polyphonic setting of refrain lyrics, such as those of Adam de la Halle, exhibit an integrated projection of the poetic structure, too uniform to command sustained compositional interest.28 Rendered fully independent by the new notation, now the tenor operates freely, creating discant-based counterpoint with the texted cantus voice. Other parameters that may be in play, and which may be staged with disjunction or with integration depending on the needs of the moment, include text projection (syllabic or melismatic, normal or syncopated declamation patterns), tonal centres (degree of tonal unity, use of directed progressions) and sonorities.

As with the motet, our role as attentive listeners in coming to terms with this aesthetic is to discover the poetic image that the work reifies. Examples are legion in Machaut: the harsh leaps and unexpected turns, as well as the wholly unorthodox cadence formation of the ballade Honte, paour, represent the contortions a faithful lover must endure; the fragrance of the rose in the rondeau Rose, lis, which is sensed in sonorous descending progressions, now with E♮, now with E♭; the ‘sweet’ opening sonority of the rondeau Douce, viare, which concludes on a soft B♭; one might continue such examples at will.29

Guillaume de Machaut and the Remede de Fortune

The figure of Guillaume de Machaut looms large in any discussion of fourteenth-century music. Equally distinguished as a poet and musician, he was unusual for the care he took in the preservation of well-organised manuscript collections of his works.30

Machaut’s early works were written in the service of John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia (r. 1311–46), son of an emperor and father of another emperor, an itinerant king active in political affairs throughout Europe. A favourable marriage sealed an alliance with King Philip VI of France: in 1332, John’s daughter Bonne married John, Duke of Normandy (the future King John II the Good, r. 1350–64). Bonne spent most of her time at Vincennes, the royal manor just east of Paris. It was here that most of the royal children were born and raised, including Charles (the future King Charles V, r. 1364–80) and his siblings, many of them patrons of music of the next generation.

Although full documentation does not survive, it appears likely that Machaut served Bonne at Vincennes at least from around 1340 until she succumbed to the Black Death in 1349. It was at her court that Machaut produced the hybrid narrative Remede de Fortune, a didactic treatise on poetic forms couched in a love story that waxes and seems to wane (one rotation of Fortune’s wheel?).31 The seven interlarded model genres, all supplied with music, include a lai, complainte, chanson royale, duplex ballade, ballade, virelai and rondeau, that is, the three fixed forms (with two forms of ballade) as well as the lyric lai (itself newly ‘fixed’). All of the fixed-form chansons are radically new, to the point that a thirteenth-century courtier would scarcely recognise them as music. Dame de qui toute ma joie vient, the second of the two ballades, is typical of the new style, now holding back and lingering on a syllable, now pushing rambunctiously ahead, always playfully unpredictable and yet affording a satisfying whole (Example 2.4).32

Example 2.4 Guillaume de Machaut, ballade Dame de qui toute ma joie vient, beginning

In the Remede de Fortune Machaut created his own universe, a self-contained world of allusion and intertextual complexity. While he does cite from past authorities such as Adam de la Halle, more frequently he cites himself.33 Like the complete works themselves, it is a world ruled by Machaut, the professional author.

The motet after the Roman de Fauvel

Philippe de Vitry had a particular expressive purpose in mind in composing the motet Garrit/In nova fert/Neuma. In realising that purpose, he hit upon the new concept of periodicity, a systematic coordination of long-range phrase articulation in all voices. Once such a powerful organisational technique was discovered, it soon transformed the motet. In so far as we can tell, all subsequent motets of Vitry, and most of the twenty-three motets of Machaut, are stamped with periodicity, always in the service of a particular poetic image.

As the century progressed, further developments continued to serve a poetic focus. For example, many ars nova motets have two sections, with an additional statement or more of the color (melody of the cantus firmus) in a different rhythmicisation, usually in diminution by one-half. The second section frequently incorporates hocket, the ‘hiccup’ effect of an isolated note in one part emphasised by a rest in the other part, a striking texture that enhances articulation of periodicity in the diminished taleae, thus making relationships clear that had been obscure in the section of long rhythmic values. An early example, Vitry’s O canenda vulgo/Rex quem metrorum/Rex regum (1330s?), leaves the diminished section without text. Yet the unusual texture is justified by a poetic image, announced in the final lines of the duplum, which speak of ‘[the king] whose virtues, mores, race, and the deeds of his son I cannot write; may they be written above the heavens’.34 What more fitting response to follow than pure music, an evocation of the music of the spheres?

After around 1360, motets might appear in three or four sections, with proportional reduction of tenor rhythms, as in Ida capillorum/Portio nature/[Ante tronum], in four sections in the proportions 6:4:3:2.35 Further, the periodicity of the upper voices often extends itself well beyond rests (as in Example 2.3), even to ‘isorhythm’ throughout each talea, in which each iteration is absolutely identical, as regards rhythm, from one talea to the next.36

Isorhythm in this literal sense has often been regarded as a desirable, even inevitable, consequence of periodicity. Paradoxically, however, isorhythm is a symptom of the breakdown of the founding principles of the ars nova motet, for it tends towards disintegration – strophic projection – instead of the integration and accumulation of poetic and musical expression that had been the ideal of the motet since Philippe de Vitry. More and more the motet tends to represent a certain generic model, a series of sections, each culminating in imposing washes of hocket sonorities. The gain was a form of polyphony impressive for public display, since a motet effectively cast in movements, with regular pockets of sublime sonorities, could be appreciated for an overall effect, as an assertion of power. This, along with easy adaptability to dedicatory or celebratory Latin texts in a variety of forms, made the motet useful in state functions in grand architectural settings.37 Later examples of grand political motets include works by Ciconia (a native of Liège) as well as many by Guillaume Du Fay.

Towards a new synthesis

The years from 1360 to 1450 saw palpable increases both in the functions assigned to polyphony and in the diffusion of works. In terms of French music, the period begins with the consolidation of the motet and polyphonic chanson within the French orbit, and the first applications of compositional techniques learned in those genres to sacred art music. It ends with the cultivation over a wide geographical area of a broadened spectrum of forms, for use in a variety of sacred and political contexts, in which the French input, decisive at the beginning, was tempered and merged with streams from the Low Countries, Italy and England in new syntheses, which eventually consolidated into the pan-European ‘international’ style that we associate with the Josquin generation of the late fifteenth century.38

Despite enormous social instability, a number of historical developments contributed to an environment in which musicians and music circulated freely, leading to the diffusion of the advanced French polyphonic style beyond Francophone limits and allowing cross-pollination with indigenous elements. Among these factors were (1) a weakened and unstable central French government under Charles VI and the increased influence of outlying courts; (2) the cultivation and development of sophisticated art polyphony at the courts of the pope and cardinals in Avignon, with a new centre opening in Rome as a consequence of the Great Schism; (3) the international diplomatic missions, with full musical retinues, that gathered at the early fifteenth-century church councils designed to lift the Schism; and (4) an increase in private endowments for polyphony in side chapels of churches, giving rise to service works in sets and cycles. It would be a long and uneven process to establish artistic polyphony at court and church; indeed, the process was far from finished at the end of the period covered in this chapter.

France under Charles VI and the Valois princes

The death of Charles V marked the beginning of a long period of decline for France as a central power. Charles VI (r. 1380–1422), at first too young to rule, then subject to intermittent bouts of insanity, stood by as his brother and his uncles vied for power. This phase of the Hundred Years War saw the English gain traction, with the victory of King Henry V at Agincourt (1415) and the occupation until 1435 of northern France by the English.39 Slow recovery, with the encouragement of Joan of Arc and the forces she rallied, came with Charles VII (r. 1422–61), crowned at Reims in 1429. The princely power centres, particularly Burgundy and Berry, stood in fierce competition with each other for the best performers and composers, although a given ruler’s active support for music might vary in times of peace or war, depending on financial resources. Dynastic marriages of Charles V’s sisters and their progeny brought French influence even further afield, to Aragon and northern Italy. One further important princely patron important for the diffusion of northern French culture, with close ties to Aragon, was Gaston Fébus, comte de Foix and vicomte de Béarn (r. 1343–91). Froissart reported that Fébus not only ‘took great pleasure in minstrelsy, for he was well versed in it’, but also ‘gladly had his clerks sing polyphonic chansons, rondeaux and virelais in his presence’.40 As musicians moved around, the cultivation of French polyphony radiated further.

Music at court

The favourable survival of archival sources for the Valois dukes of Burgundy have made it possible to form a detailed picture of courtly musical activities in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries.41 Servants of widely varying musical skills provided a broad range of musical functions. Trumpeters played an essential role, conveying military orders in the din of battle (indeed they were issued with armour). Their fanfares, along with the blare of the minstrels, also contributed to the pomp accompanying the duke’s grand entry into a city, or added to the clangour of the tournament, or to the ceremonial tattoo at diplomatic gatherings and peace conferences.

Closer to the duke (and also issued with armour in war) was his harper, a courtier who not only provided soft music as an ornament to the chamber or to the duke’s immediate proximity in the banquet hall, but was also essential for the duke’s diversion over his numerous displacements between Flanders, Burgundy and Paris. Sometimes such virtuosos of harp and song can be identified as known composers (for example, Jaquemin de Senleches, fl. 1382–3, and later Gilles Binchois, c. 1400–60), allowing us to imagine a social context for a portion of the extant written repertoire. Other chamber valets serving the duke (or ladies-in-waiting serving the duchess) might cultivate musical skills as a singer-poet (faiseur), or play estampies on the portative organ or clavichord (eschequier).42

Chapel singers and choirboys were essential to the cultivation of the holy rites, even when the court was in transit. While plainsong sufficed for church processions as well as the day-to-day Office, Philip the Bold’s chapel performed polyphony for special expanded celebrations at Christmas, Easter, Pentecost and All Saints’ Day, as well as New Year’s Day.

Finally, among the musicians serving at court were minstrels skilled in strings, winds, percussion, portative organ and clavichord, who played for the entries, banquets and balls that accompanied weddings, baptisms and important political gatherings. Minstrels performed music learned by memory, perhaps employing strategies worked out in meetings – the so-called minstrel schools – held yearly in different cities during Lent.43 The grandest occasions were supported by the full range of court musicians, at times massing the forces of several separate courts with town musicians. Perhaps the most notorious large gathering, occasioned by a planned crusade against the Turks after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, was Duke Philip the Good’s ‘Feast of the Pheasant’ held the next year in Lille, which enacted musical entremets between chapel musicians in a miniature church at one end of the hall and minstrels performing from an enormous pastry at the other.44

The Avignon papacy and the Great Schism

Pope Benedict XII (r. 1334–42) had established a college of some dozen singers for papal Masses, a group that subsequent popes maintained throughout the fourteenth century.45 Although solemn feasts, bound more rigidly by tradition and often officiated or at least attended by the pope, were sung in plainchant, polyphony was probably introduced in lesser feasts and left to the direction of the college of singers. Polyphonic Mass Ordinaries could be performed for most of the year. It was also possible, at least by the early fifteenth century, to use the organ in hymns, probably in alternatim practice (alternating verses, one in the choir, unaccompanied, the next in the organ, instrumentally elaborating the cantus firmus).

The importance of Avignon as a musical centre in the fourteenth century was due not merely to the pope’s singers, but also to the chaplains and clerks in the retinues of the many resident cardinals, whose households rivalled those of secular princes in splendour. Grand festivals celebrating visits of kings and great princes offered ample occasion for musical exchanges and interaction. Surviving written polyphony celebrates particularly the more luxury-loving popes.46

The emergence of the pope and ambient cardinals as patrons of music came to a head with the return to Rome and the Great Schism (1378–1417). The reconstituted Roman papacy maintained the Avignonese model of bureaucracy and patronage, as well as a chapel of skilled singers from northern dioceses. In addition, the Roman pope controlled lucrative benefices in territories that aligned with Rome, notably the county of Hainault and bishopric of Liège, which would funnel skilled musicians to Rome. Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370–1412) of Liège, who journeyed to Rome around 1390, was one of the first of a long line that would include Du Fay and later Josquin des Prez.47 Ciconia is best known for a series of political motets that synthesise French and Italian elements, and for his Italian songs.48 A significant work in French is his virelai Sus un’ fontayne, perhaps written for the Visconti court at Pavia, which quotes the opening passages of three French ballades of Philipoctus de Caserta, an Italian composer who wrote exclusively in the most complex French style.49

Musical styles in the years around 1400: an ars subtilior

The style of motet and chanson that consolidated around 1360 was well known in the courts and curia of the late fourteenth century. An example – the most widely transmitted work of the entire fourteenth century – is the ballade De ce que fols pense (‘What a fool thinks’) by Pierre des Molins, a chaplain of John II who served the captured French king in English exile during the years 1357–9. (He is later found in the service of the duc de Berry.) To judge from its refrain, ‘d’ainsi languir en estrange contree’ (‘thus to languish in a foreign country’), the ballade was written in England. Works of a core ars nova repertoire such as this one seem to have been cultivated for many years: to judge from transmission patterns, perhaps as late as around 1420.

Another popular style of artistic polyphony cultivated in these courts (one with no precedent in Machaut) is the mimetic chanson, particularly the so-called ‘bird-call virelai’, such as Jean de Vaillant’s widely known Par maintes foys (‘Many times’). Here the disruptive call of the envious cuckoo competes with the complex song of the nightingale, providing a neat justification for a rhythmic innovation, in which four fast minims can replace three, in effect shifting between quaver triplets and groups of four semiquavers.

The confrontation and combination of disjunct elements that polyphony makes possible occasionally affords a glimpse of a realm of music normally left unwritten. For example, the anonymous virelai Contre le temps et la sason jolye/He! Mari, mari! (‘Against the pretty weather and season/Hey, husband, husband!’) pits a virtuosic and rhythmically complex upper voice against a simple dance-song in the tenor. (The opening text of the upper voice is a pun, with the additional meaning of ‘against the time’ or ‘against the measure’.) We can only be grateful that a window on what must have been a large and vital phenomenon at court survives in such a work: the performance of a sung dance on the sort of refrain known since the thirteenth century. This and a few similar works delight in a stylistic disjunction between ultra-refinement and a continuing oral tradition, a rupture savoured in high French courts as an outward manifestation of cultural sophistication. Such works became even more common in the course of the fifteenth century, for instance the charming Filles a marier (‘Girls to be married’) by Binchois on a popular song tenor Se tu t’en marias, tu t’en repentiras (‘If you get married you’ll regret it’).50

By the 1380s some works display an ars subtilior, a fever pitch of complexity, the ultimate expression of high French culture.51 Justification for extreme compositional virtuosity sometimes lies in mimesis, of which Par maintes foys is a modest example. At other times, a work may comment in apparent irony on the current woeful state of music, as in the very complex ballade by Guido, Or voit tout en aventure (‘Now everything is run amok’), which employs three different note shapes to express the same duration, seeming to prompt the refrain ‘Certes ce n’est pas bien fayt’ (‘Certainly this is not well made’). On the one hand this navel-gazing may appear to focus on musical developments of restricted value and function, but on the other such works manifest a growing focus on the individual artist.52

The most skilled of these ars subtilior musicians also played games of one-upmanship with each other, multiplying intertextual citations and allusions in their works. A good example is the ‘En attendant’ series, involving at least two rondeaux and three ballades by various composers, works that have been related to the ill-fated Neapolitan campaign of Louis I, duc d’Anjou, of the early 1380s, aided by Pope Clement VII and Bernabò Visconti.53

The complex style also manifests itself in many dedicatory songs, such as ballades for Pope Clement VII, ballades celebrating Gaston Fébus and ballades celebrating the wedding of John, duc de Berry, and Jeanne de Boulogne (a princess raised by Fébus) in 1389. Characteristics of the style include fast ornamental passages in complex cross-rhythms, motet-like hocket segments and held notes to set off the refrain rhetorically. Long after simpler styles had begun to dominate the scene, such highly refined and hyper-virtuosic display was prized in aristocratic circles quite far afield, as for example in Du Fay’s ballade Resvelliés vous (‘Rouse yourselves’) for the wedding of Carlo Malatesta da Pesaro and Vittoria di Lorenzo Colonna at Rimini in 1423.

Church councils and papal politics

An effort to end the Schism at the brief Council of Pisa (1409) succeeded only in electing a third pope. It was the Council of Constance (1414–18), culminating in the election of Martin V in 1417, that finally deposed the pretenders. Countless receptions and ceremonies of high officials of church and state, processions and grand Masses gave thousands of participants ample opportunity to hear diverse practices, both the unwritten musical collaborations of trumpeters and minstrels and the artistic polyphony of chapel singers.

One index of the reception specifically of French music at Constance is seen in the contrafacts (new textings of old music) of the poet and composer Oswald von Wolkenstein (c. 1376–1445), in the service of King Sigismund of Luxembourg, an architect of the Council. Among several popular French works that Oswald heard was Vaillant’s Par maintes foys, reworked as Der mai mit lieber zal (‘May, with a lovely throng’).54 Vaillant’s virelai also appeared in the Strasbourg manuscript (Bibliothèque Municipale, 222 C.22, burned in 1871) with a sacred contrafact text Ave virgo gloriosa. It must have been jarring for French clerics to hear familiar vernacular chansons subjected to Latin sacred contrafacture by German and Bohemian clerics, let alone the amusingly incomprehensible prolixity of von Wolkenstein’s South Tyrolian dialect. Thus did foreigners reimagine French musical art. Even so, the new Latin sacred settings were attractive vehicles, communicating their messages in the appealing garb of a chanson rather than the high formality of a motet. It is worth considering this and other possible scenarios (including English input at the re-established papal chapel in Rome, and the English occupation of Paris and northern France) to ground the development of the cantilena motet (more like a chanson with sacred text than a traditional motet), a new genre emerging in the 1420s.55

Several manuscripts document the widespread transmission of English music to the Continent during the extended period of the Council of Basel (1431–49).56 By now the cantilena motet was a well-established fact; at this point the most useful lesson for further development lay in the enormous potential of undergirding several movements of the Mass Ordinary with a single cantus firmus, a technique first found in some English Masses of the 1420s.57 The compositional (and aesthetic) lessons of the old motet were brought to bear in this multi-movement ‘tenor Mass’, a form increasingly employed in Mass cycles composed for special functions.

Votive Masses and anniversaries, sets and cycles

Even at large churches throughout a good part of the fifteenth century, High Mass in the choir remained hidebound, celebrated in monophonic plainchant. Nevertheless, manuscripts show that as the fifteenth century unfolded, there was a growing demand for polyphonic service music, answered more and more by sets or cycles of works, for both Mass (Propers, Sequences, Ordinaries) and Office (especially hymns, antiphons and Magnificat settings for Vespers).58 Two tendencies are present. On the one hand, a composer might fill out feasts in the liturgical year with workaday elaborations of plainchant cantus firmi, often paraphrased (rendered into modern-sounding melodies) in the upper voice or tenor of a three-voice setting. For example, Du Fay wrote large cycles of hymn and Kyrie settings, products of his many years of service to the papal chapel and to princely chapels.59 On a far larger scale, Du Fay supervised the collection of polyphonic service music – both Ordinaries and Propers – for the entire liturgical year at Cambrai Cathedral in the 1440s.

On the other hand, a composer might write a set of Propers, or most usually a polyphonic Mass, a cycle of Ordinaries, for special-purpose endowments.60 Members of elite social strata, at first princes and rich churchmen, and increasingly rich merchants and guilds, endowed such private devotions in side chapels, most usually a Mass to the Virgin performed in a lady chapel, to ease the path of their souls to salvation. Such ‘anniversary’ services were not restricted to yearly observance, as the name seems to imply, but might be observed weekly or even daily; it depended on the revenues made available by the patron to pay the singers. An early example is the Machaut Mass (c. 1364), the composer’s own memorial to be sung at the Saturday Lady Mass at Reims Cathedral.61Reinhard Strohm has proposed an analogous commemorative function for Du Fay’s last Mass, the Missa Ave regina celorum (c. 1470–1), replaced after his death by a three-voice Requiem (not extant).62

Guillaume Du Fay

At the close of this chapter, it is appropriate to focus on Du Fay (c. 1397–1474), a figure who not only sums up the principal stylistic heritage of the fourteenth century, the motet and the fixed-form chanson, but also, in absorbing contemporary influences and tendencies, materially contributed to a new beginning, broadening the domain of art music with the cantilena motet and a vastly expanded repertoire of simple service music for Mass and Office, as well as contributing model cantus-firmus Masses, which synthesised English and Continental tendencies.63 No other composer of polyphony, from any previous period, composed as much music in as many different styles. Yet despite this new beginning, Du Fay at the same time marked a point of termination in that his music had a short shelf life: what he helped to begin was continued in new directions after his death.

Educated as a choirboy at Cambrai Cathedral, Du Fay probably figured among the some 19,000 clerics and church dignitaries who in 1414 descended on Constance, where he would have observed written and unwritten local practices of ecclesiastical and courtly chapels from all over Europe. From there he proceeded to Italy, one of the most distinguished of the French-speaking northerners to forge a new style in that land. Over the next twenty-five years, Du Fay established himself as a leading composer whose works were actively sought by ecclesiastical and secular patrons alike, including an Italian noble family, the Malatesta, two popes and finally duc Amédée VIII de Savoie. By hiring Du Fay, the duke in one stroke raised the level of his musical establishment to such a degree that in 1434, at the marriage of his son Louis with Anne of Cyprus, he could without embarrassment greet the visiting Burgundian Duke Philip the Good, who had travelled to Chambéry with a retinue of some 200, among them the distinguished composer Binchois.

The marriage was doubtless the occasion for the meeting of Du Fay and Binchois celebrated by the Savoyard poet Martin Le Franc in his Champion des dames (c. 1438–42). The passage, well known in music history, proclaims a shift in musical style, occasioned by Du Fay and Binchois, who in some sense ‘followed’ the English composer Dunstable and adopted the ‘English manner’ (contenance angloise). Many music historians have associated Le Franc’s commentary, as well as some related statements in the music theorist Tinctoris, with the watershed of a musical ‘Renaissance’.64 In the end, the attempt to find some occasion or other to justify such an apocalyptic label is not helpful, but it is certainly true that these years of stylistic assimilation served a rapid transformation of music.

The music of this first period of Du Fay’s compositional career, which exhibits maturity from the start, counts major works in the full range of genres he cultivated. Solemn occasions found expression in the learned style of the political and dedicatory motet, of which the best known is Nuper rosarum flores, celebrating the consecration of Florence Cathedral in 1436. The proportional lengths of its four sections – 6:4:2:3 – represent the model church, Solomon’s temple.65

Probably a little more than fifty of around eighty extant songs belong to these early years. Among them is the ars subtilior dedicatory ballade Resvelliés vous (1423), mentioned earlier. By contrast, smooth and flowing rhythms (some consider this quality a matter of English influence) dominate the ballade Se la face ay pale, perhaps originally destined for the 1434 Savoy wedding and popular for many years thereafter (the last section is given in Example 2.5a).66 French-language songs enjoyed an overwhelming preponderance in Italian sources until at least 1440, and there exist only a handful of works in Italian from these years in Italy, notably Du Fay’s own setting of the Petrarchan canzona Vergine bella.67

Example 2.5a Guillaume Du Fay, ballade Se la face ay pale, last phrase

Du Fay returned to Cambrai in 1439, now as a resident at his home church, enjoying the canonicate that papal service had netted. The next decade saw the completion of some large-scale sacred projects, including a thorough-going reorganisation of liturgical music at Cambrai Cathedral, encompassing both plainchant and polyphony.

A good part of the 1450s found Du Fay back in the south, mostly at Savoy. One important work of this period, the Missa Se la face ay pale, creates a uniquely Continental response to the English cantus firmus Mass cycle, building especially on the anonymous Missa Caput.68 The reception of the relic known today as the Shroud of Turin (held at Chambéry from 1453 until 1578) was probably the occasion for Du Fay’s Mass. The cantus firmus, the tenor of the ballade Se la face ay pale, which Du Fay had composed for Savoy twenty years earlier, infuses each of the five movements of the Mass with the musical emblem of Christ’s pale face.69 Musically, Du Fay’s cyclic Mass draws on form-defining aspects of the grand motet: cantus firmus iterations in proportional diminution prefaced by introductory duets, and culminating in rhythmically animated segments. For example, both the Gloria and Credo movements of the Missa Se la face ay pale are laid out in three colores, with the cantus firmus subject to proportional diminution (3:2:1); see Example 2.5b for the last phrase, and compare Example 2.5a.71

Example 2.5b Guillaume Du Fay, Missa Se la face ay pale, Gloria, last phrase

As far as we know, Du Fay spent his last sixteen years at Cambrai. By the late 1450s, the composition of Mass cycles on the Continent had exploded. Du Fay’s own Missa L’homme armé was composed then, perhaps becoming the first of a long line of Mass settings on that tune.72 But the work that best sums up the moment is a devotional motet that Du Fay had asked to be sung at his deathbed, a work that combines a setting of the Marian antiphon Ave regina celorum (‘Hail Queen of Heaven’) with a personal prayer. Table 2.1 shows the interlocking layout of the texts in the first section, as the antiphon is interrupted by Du Fay’s prayer (italic text). As in the earliest polyphony, the tenor (shown in the right-hand column) carries only the cantus firmus, first entering at the point when the other voices intone Du Fay’s prayer. Du Fay exhibits his fluid mastery of cantus firmus paraphrase in this work, for the borrowed melody may appear in voices besides the tenor, always recognisable at the beginning of a phrase, but free to break into florid melisma to drive to an important cadence, thereby supplying the excitement of the old hocket segments without the hard edges. The tenor statement in Example 2.6 is by contrast rather literal (cantus firmus pitches are indicated by ‘x’).73

Table 2.1 Text distribution in Du Fay’s Ave regina celorum (III), first section

Example 2.6 Guillaume Du Fay, Marian antiphon Ave regina celorum (III), end of first section

Gradually over the course of the first half of the fifteenth century, itinerant performers and composers, in restlessly absorbing new influences as they responded to demands from new centres of activity, effectively transformed musical genres, broadening uses and venues for polyphony. The new syntheses and diversity of forms made a preponderantly rhetorical music possible later in the century, a new emphasis that would shake the foundations of expression.74 This, however, was a matter for the future. A familiar Marian antiphon resounds throughout Du Fay’s funeral motet, directing his personal prayer; despite some modern details, it remains emblematic of the ‘totalising’ aesthetic set in place in the early fourteenth century.

Notes

1 (ed.), Scriptorum de musica medii aevi: novam seriem a Gerbertina alteram, 4 vols (1864; repr. Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), vol. I, 327–64, designates the writer ‘Anonymous IV’. See the English translation in The Music Treatise of Anonymous IV: A New Translation, ed. and trans. (Stuttgart: Hänssler, 1985).

2 Example 2.1a is based on Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, 628, fol. 36r (old fol. 42r); image accessed from http://diglib.hab.de/wdb.php?dir=mss/628-helmst (accessed 22 May 2014); slurs indicate ligatures in the source. Example 2.1b is based on the same manuscript, fol. 36v (old fol. 42v); ligatures in the source are not indicated in the edition. Example 2.1b presents the rhythmic shape of the discant segment as it was transmitted c. 1230 in our earliest extant source (see n. 7 below). A complete edition is in Le Magnus Liber organi de Notre-Dame de Paris, vol. IV: Les organa à deux voix pour la messe (de l’Assomption au Commun des Saints) du manuscrit de Florence, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Plut. 29.1 ed. (Monaco: L’Oiseau-Lyre, 2002), 50–7.

3 On the dates, see , Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge University Press, 1989), 281–8.

4 , Medieval Music and the Art of Memory (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 161–97.

5 Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 29.1. On the date, see and , ‘Magnus liber – maius munus: origine et destinée du manuscript F’, Revue de musicologie, 90 (2004), 193–230.

6 Example 2.1c is based on Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 29.1, fol. 129v (online image fol. 112v); image accessed from http://teca.bmlonline.it/TecaViewer/index.jsp?RisIdr=TECA0000342136 (accessed 22 May 2014); ligatures in the source are not indicated in the edition.

7 Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, 628. On the date, see , ‘From Paris to St. Andrews: the origins of W1’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 43 (1990), 1–42.

8 Example 2.2 is based on Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, 1099, fols 146v–147r; image accessed from http://diglib.hab.de/wdb.php?dir=mss/1099-helmst (accessed 22 May 2014); ligatures in the source are not indicated in the edition.

9 Text and translation from Philip the Chancellor: Motets and Prosulas, ed. , Recent Researches in the Music of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance, 41 (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2011), 91–3 (I have altered the line divisions in the example). Payne attributes this text to Philip the Chancellor. See also (ed.), Anthology of Medieval Music (New York: Norton, 1978), 72–4.

10 See Philip the Chancellor: Motets and Prosulas, ed. Payne, xi–xxx.

11 Two early treatises on modal notation are in (ed.), Source Readings in Music History, rev. edn (New York: Norton, 1998), 218–26.

12 The three-voice form, Ex semine rosa / Ex semine Abrahe/Ex semine, is edited in Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. I: Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century (Oxford University Press, 2005), 209–13, with facsimiles of some sources.

13 The texts and music of Se j’ai amé (‘If I have loved I should not be blamed for it if I am committed to the most courtly little thing in the city of Paris’) and Hier main trespensis (‘Yesterday morning, deep in thought, I wandered along my way, I saw beneath a pine a shepherdess, who was calling Robin with a pure heart’) are in Hoppin (ed.), Anthology of Medieval Music, 72–4.

14 See , Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet: The Sacred and the Profane in Thirteenth-Century Polyphony (Stanford University Press, 1997); and , Poetry and Music in Medieval France: From Jean Renart to Guillaume de Machaut (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

15 , Rondeaux et refrains du XIIe siècle au début du XIVe (Paris: Klincksieck, 1969), 14–15. Butterfield, Poetry and Music in Medieval France, is an important recent study of the refrain, with full bibliography.

16 See , The Owl and the Nightingale: Musical Life and Ideas in France, 1100–1300 (London: Dent, 1989), 144–54; , Discarding Images: Reflections on Music and Culture in Medieval France (Oxford University Press, 1993), 43–111; and Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. I, 207–8, 226.

17 Trans. in , ‘Johannes de Grocheio on secular music: a corrected text and a new translation’, Plainsong and Medieval Music, 2 (1993), 36 (footnotes omitted).

18 Quoting Butterfield, Poetry and Music in Medieval France, 105. See also Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 187–207.

19 Franco of Cologne, Ars cantus mensurabilis, in Strunk (ed.), Source Readings, 226–45.

20 Edition in The Montpellier Codex, ed. (Madison: A-R Editions, 1978), vol. III, 88–9. For a complete analysis, see , ‘Beyond glossing: the old made new in Mout me fu grief/Robin m’aime/Portare’, in (ed.), Hearing the Motet: Essays on the Motet of the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 1997), 28–51.

21 Jehan des Murs, Notitia artis musicae, in Strunk (ed.), Source Readings, 268.

22 Facsimile and commentary in in the Edition of Mesire Chaillou de Pesstain: A Reproduction in Facsimile of the Complete Manuscript, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds français 146 ed. , and (New York: Broude Brothers, 1990).

23 , ‘Hybridity, monstrosity, and bestiality in the Roman de Fauvel’, in and (eds), Fauvel Studies: Allegory, Chronicle, Music, and Image in Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Français 146 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 161–74.

24 Hoppin (ed.), Anthology of Medieval Music, 120–6.

25 See Ardis Butterfield, ‘The refrain and the transformation of genre in the Roman de Fauvel’, in Bent and Wathey (eds), Fauvel Studies: Allegory, Chronicle, Music, and Image in Paris, 105–59; and , Medieval Music-Making and the (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 216–82.

26 Each crotchet of the music in Example 2.3, corresponding to a breve in the original, is equal to one full bar (dotted minim) of the transcription in Hoppin, Anthology of Medieval Music, No. 59 (bar numbers reflect that edition). Each line of the example is one talea (repeating rhythmic unit) of the tenor – the entire motet is made up of six taleae. There are two repetitions of the color (melody of the cantus firmus), each taking up three taleae (6T = 2C). Notes and rests of the tenor in red notation, indicating a change from modus perfectus to modus imperfectus, are set between angle brackets. The rhythmic values of the complete tenor are indicated, but little beyond the location of rests in the upper voices (blank spaces in the upper voices are filled with free music).

27 , ‘Lyrics for reading and lyrics for singing in late medieval France: the development of the dance lyric from Adam de la Halle to Guillaume de Machaut’, in , and (eds), The Union of Words and Music in Medieval Poetry (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991), 101–31; see also Butterfield, Poetry and Music in Medieval France, 273–90.

28 studies the polyphonic chanson before Machaut in three articles: ‘The polyphonic “rondeau” c. 1300: repertory and context’, Early Music History, 15 (1996), 59–96; ‘Motets, French tenors, and the polyphonic chanson ca. 1300’, Journal of Musicology, 24 (2007), 365–406; and ‘“Souspirant en terre estrainge”: the polyphonic rondeau from Adam de la Halle to Guillaume de Machaut’, Early Music History, 26 (2007), 1–42.

29 On Honte, paour, see , ‘Tendencies and resolutions: the directed progression in “ars nova” music’, Journal of Music Theory, 36 (1992), 240–6; on Rose, lis, see , ‘Machaut’s Rose, lis and the problem of early music analysis’, Music Analysis, 3 (1984), 9–28.

30 , ‘Machaut’s role in the production of manuscripts of his works’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 42 (1989), 461–503.

31 For an edition and translation of the Remede de Fortune, see , Le Jugement du roy de Behaigne and Remede de Fortune, ed. and (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988).

32 Example 2.4 is based on Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, fr. 1584, fols 70v–71r; image accessed from http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84490444/f162.image.r=francais%201584%20machaut.langEN; ligatures in the source are not indicated in the edition.

33 On citation in Machaut, see , The Art of Grafted Song: Citation and Allusion in the Age of Machaut (Oxford University Press, 2013).

34 Trans. in booklet for CD recording, Philippe de Vitry and the Ars Nova: 14th-Century Motets, The Orlando Consort, Amon Ra CD-SAR 49 (1991).

35 Motets of French Provenance, ed. , Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century, 5 (Monaco: L’Oiseau-Lyre, 1968), Nos. 5 and 5a, 24–35.

36 On the modern historiography of this term, see , ‘What is isorhythm?’, in et al. (eds), Quomodo cantabimus canticum? Studies in Honor of Edward H. Roesner (Middleton, WI: American Institute of Musicology, 2008), 121–43.

37 Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. I, 277–81.

38 In The Rise of European Music, 1380–1500 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), Reinhard Strohm studies traditions in all parts of Europe as they intermingled and transformed themselves.

39 On the possible repercussions of the English occupation, see ibid., 239.

40 , Chroniques: Livre III (du voyage en Béarn à la compagne de Gascogne) et Livre IV (années 1389–1400), ed. and , Le livre de Poche ‘Lettres Gothiques’ (Paris: Librairie Générale Française, 2004), book 3, §13, 176–7.

41 For Philip the Bold and John the Fearless, see , Music at the Court of Burgundy, 1364–1419: A Documentary History, Musicological Studies, 28 (Henryville, PA: Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1979). For Philip the Good and Charles the Bold, see , Histoire de la musique et des musiciens de la cour de Bourgogne sous le règne de Philippe le Bon (1420–1467) (Strasbourg: Heitz, 1939). On the other Valois dukes, see, for John of Berry, Wright, Music at the Court of Burgundy; and , ‘Music and musicians at the Sainte-Chapelle of the Bourges palace, 1405–1515’, in Atti del XIV congresso della Società Internazionale di Musicologia, 3 vols (Turin, 1990), vol. III, 689–701; and for Louis of Anjou, , ‘Music for Louis of Anjou’, in and (eds), Borderline Areas in Fourteenth and Fifteenth-Century Music (Münster and Middleton, WI: American Institute of Musicology, 2009), 15–32. On the urban context for music in the most important northern centre of the Burgundian realm, see , Music in Late Medieval Bruges, rev. edn (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 1–9, 74–101.

42 On ladies-in-waiting, see , ‘Parisian nobles, a Scottish princess, and the woman’s voice in late medieval song’, Early Music History, 10 (1991), 145–200.

43 On ‘unwritten’ strategies of realising music, see Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 348–9, 357–67 and 557–8. On minstrel schools, see Wright, Music at the Court of Burgundy, 32–4; and Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 307–8.

44 See the account of Olivier de la Marche in Strunk (ed.), Source Readings, 312–16.

45 The best treatment of music at Avignon is , Music and Ritual at Papal Avignon, 1309–1403 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1983).

46 , ‘Early papal motets’, in (ed.), Papal Music and Musicians in Late Medieval and Renaissance Rome (Oxford University Press, 1998), 5–43.

47 See Giuliano Di Bacco and John Nádas, ‘The papal chapels and Italian sources of polyphony during the Great Schism’, in Sherr (ed.), Papal Music and Musicians, 50–6.

48 On Ciconia’s motets, see , ‘The fourteenth-century Italian motet’, in and (eds), L’ars nova italiana del Trecento VI: Atti del congresso internazionale ‘L’Europa e la musica del Trecento’ (Certaldo: Polis, 1992), 85–125; and Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 96–9.

49 See , ‘Ciconia’s Sus un’ fontayne and the legacy of Philipoctus de Caserta’, in (ed.), Johannes Ciconia, musicien de la transition (Turnhout: Brepols, 2003), 131–68.

50 On Filles a marier, see Strohm, Music in Late Medieval Bruges, 85.

51 , ‘Das Ende der ars nova’, Musikforschung, 16 (1963), 105–21; , ‘Che cosa c’è di più sottile? riguardo l’ars subtilior?’, Rivista italiana di musicologia, 31 (1996), 3–31.

52 On music about music, see Anne Stone, ‘The composer’s voice in the late-medieval song: four case studies’, in Vendrix (ed.), Johannes Ciconia, musicien de la transition, 169–94; and , ‘Criticism of music and music as criticism in the Chantilly Codex’, in and (eds), A Late Medieval Songbook and its Context: New Perspectives on the Chantilly Codex (Bibliothèque du Château de Chantilly, Ms. 564) (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009), 133–59. For the case of Or voit, see Dorit Tanay, ‘Between the fig tree and the laurel: Or voit tout en aventure revisited’, in Plumley and Stone (eds), A Late Medieval Songbook and its Context, 161–78.

53 See , ‘Citation and allusion in the late ars nova: the case of Esperance and the En attendant songs’, Early Music History, 18 (1999), 287–363; and Reinhard Strohm, ‘Diplomatic relationships between Chantilly and Cividale?’, in Plumley and Stone (eds), A Late Medieval Songbook and its Context, 238–40.

54 Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 119–21. Nine of the eleven songs in Strohm’s list of contrafacts were originally French.

55 On Rome, see Di Bacco and Nádas, ‘The papal chapels’, 58–87; on the English in Paris, see Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 197–206, 239.

56 Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 251–60.

57 On the development of the cantus firmus Mass cycle, see ibid., 228–38.

58 The formulation ‘sets and cycles’ is Strohm’s. Ibid., 435–40.

59 Alejandro Enrique Planchart, ‘Music for the papal chapel in the early fifteenth century’, in Sherr (ed.), Papal Music and Musicians, 109–17.

60 , ‘Guillaume Du Fay’s benefices and his relationship to the Court of Burgundy’, Early Music History, 8 (1988), 117–71; Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 170–81, 273–81; and , The Cultural Life of the Early Polyphonic Mass: Medieval Context to Modern Revival (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 39, 270 n. 2.

61 On the Machaut Mass, see , Guillaume de Machaut and Reims: Context and Meaning in his Musical Works (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 257–75.

62 Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 283–7.

63 , Dufay, The Master Musicians, rev. edn (London: Dent, 1987), remains a superb longer study of the composer.

64 The passage in Martin Le Franc has been much discussed; see , Music in the Renaissance, rev. edn (New York: Norton, 1959), 12–14; , ‘Dufay at Cambrai: discoveries and revisions’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 28 (1975), 180; , ‘Dunstable in France’, Music and Letters, 67 (1986), 1–3; , ‘The contenance angloise: English influence on Continental composers of the fifteenth century’, Renaissance Studies, 1 (1987), 189–208; Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 127–9; , ‘The musical stanzas in Martin Le Franc’s Le champion des dames’, in and (eds), Music and Medieval Manuscripts: Paleography and Performance: Essays Dedicated to Andrew Hughes (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 91–127; , ‘New music for a world grown old: Martin Le Franc and the “contenance angloise”’, Acta musicologica, 75 (2003), 201–41; , ‘Neue Aspekte von Musik und Humanismus im 15. Jahrhundert’, Acta musicologica, 76 (2004), 135–57. For Tinctoris, see the dedication of the Proportionale musices (1473–4), in Strunk (ed.), Source Readings, 291–3.

65 See , ‘Dufay’s Nuper rosarum flores, King Solomon’s temple, and the veneration of the Virgin’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 47 (1994), 395–441.

66 Example 2.5a is based on Guglielmi Dufay opera omnia, ed. , vol. VI, rev. (Middleton, WI: American Institute of Musicology/Hänssler, 2006), p. 38; numerous emendations.

67 See , ‘French as a courtly language in fifteenth-century Italy: the musical evidence’, Renaissance Studies, 3 (1989), 429–41.

68 , ‘The Savior, the woman, and the head of the dragon in the Caput Masses and motet’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 59 (2006), 537–630.

69 , ‘The man with the pale face, the shroud, and Du Fay’s Missa Se la face ay pale’, Journal of Musicology, 27 (2010), 377–434.

70 Antiphon: ‘Hail Queen of Heaven, Hail mistress over the angels’; prayer: ‘Have mercy on thy dying Dufay Lest, a sinner, he be hurled down into seething hot hellfire.’ Trans. in (ed.), The European Musical Heritage, 800–1750, rev. edn (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006), 159–60, with musical edn, 153–9.

71 Example 2.5b is based on Guglielmi Dufay opera omnia, ed. , vol. III (Neuhausen Stuttgart: American Institute of Musicology/Hänssler, 1951), 12–13; numerous emendations. On the influence of ‘isorhythmic’ techniques in Mass movements, see Bent, ‘What is isorhythm?’; and Kirkman, The Cultural Life of the Early Polyphonic Mass, 264 n. 66.

72 , The Maze and the Warrior: Symbols in Architecture, Theology, and Music (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 175–205.

73 Example 2.6 is based on Guglielmi Dufay opera omnia, ed. , vol. V (Neuhausen Stuttgart: American Institute of Musicology/Hänssler, 1966), 124–5; numerous emendations.

74 On the change in musical expression from a ‘medieval’ symbolism to a ‘Renaissance’ mimesis, see Wright, The Maze and the Warrior, 203–5.