Since the industry-wide adoption of computer-generated (CG) animation in the mid-1990s – starting with Pixar’s Toy Story in 1995 – full-length animations have been among the most commercially successful features made or financed by Hollywood in the twenty-first century (Box Office Mojo 2015). The associated merchandizing is also hugely lucrative, capable of generating vastly more income than the films themselves. (For instance, the Disney Brand Corporation generated $40.9 billion from their licensed merchandizing in 2013; see Graser Reference Graser2014.) As consumers, we are constantly being encouraged to enhance our cinematic ‘experience’ through branded toys, clothing, food and other ‘lifestyle products’. The over-abundance of merchandise aimed at very young children lulls many parents into thinking that the associated films are suitable for their offspring, yet many of these CG animations have not been designed with pre-schoolers (or even under-tens) in mind. This is because digital technology has diminished many of the traditional distinctions between live action and animation, enabling the films to be ‘shot with the speed, allusiveness, and impact of movies for adults … [making them] too noisy, dazzling, and confusing for very young brains to take in’ (Kirby Reference Kirby2009, 128). Advances in motion-capture technologies have also made these films ‘less identifiably “cartoonish” and therefore less apt to be defined automatically as juvenile entertainment’ (N. Brown Reference Brown2012, 295).

There are other adult enticements. Many of the scripts for CG animations rely on copious amounts of dialogue to tell the story and deliver the comedy (the latter through tongue-in-cheek humour and meta-textual references) rather than visual, non-textual means which younger children can more easily follow. Moreover, these scripts are often delivered by leading names from the movie and music industries, and some catchy pop songs are included on the soundtrack. Whilst overtly adult sexual behaviour is still strictly avoided, allusive references typically manifest themselves through this use of pop music, which has become ‘the semi-sublimated packaging of adult sexuality for young children’ (Kirby Reference Kirby2009, 134). George Miller’s digitally animated feature Happy Feet (Animal Logic Film, 2006; a co-production for Warner Bros. and Village Roadshow Pictures) – set largely among a colony of Emperor penguins in Antarctica – is a prime example. Beneath Happy Feet’s surface pleasures, there are some ugly aspects concerning sex and race with which the pop songs on the soundtrack are inescapably entwined. This chapter will examine two short sequences of pop-song mash-ups which are at the core of debates regarding the film’s efficacy.

Miller approached the animation as if it were a live-action movie, aiming for a photo-realistic aesthetic and simulating ambitious fast-moving camera techniques. Although the penguins are anthropomorphized, they also exhibit many traits of real penguin behaviour. The director drew much of his initial inspiration and knowledge about Emperor penguin society from the wildlife documentary series Life in the Freezer (BBC, 1993) and was particularly fascinated to discover that each Emperor penguin has a unique display song which it uses to attract and thereafter locate its mate within a noisy colony. From this biological fact, Miller’s ideas grew into ‘an accidental musical’ about a colony of singing penguins, each of which had an individual ‘heartsong’, and a misfit hero – Mumble – who can’t sing, but is compelled to tap dance (Maddox Reference Maddox2006). The penguins’ heartsongs were culled from pre-existing pop classics about love, relationships and lonely hearts, whilst their movements – both naturalistic and choreographed – were generated by human performers wearing motion-capture body suits. A low-resolution of these digitized performances was available for viewing in real-time – like live-action shooting – before being manipulated and refined in post-production (Leadley Reference Leadley2006, 52). (In a similar manner to the principles of motion-capture, Disney’s animators from the 1930s onwards often used live action of humans and animals as an expedient way of drawing more intricate aspects of anatomy and locomotion; see Thomas and Johnston Reference Thomas and Johnston1981, chapter 13.) Savion Glover, considered amongst the world’s greatest tap-dancers, furnished Mumble’s tap dancing whilst Elijah Wood provided his voice; the other lead penguins were voiced by well-known Hollywood actors with demonstrable singing abilities (Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman, Robin Williams and Brittany Murphy) or by recording artists (Fat Joe, Chrissie Hynde). The British composer John Powell had executive control of the entire soundtrack: he wrote the original orchestral score and was also responsible for the arrangement and production of most of the pre-existing pop songs, adding some of his own material in an appropriate vein where necessary to piece everything together. Powell has scored or co-scored an impressive list of live-action and animated films since the late 1990s – the latter mainly for DreamWorks Pictures/DreamWorks Animations (including the How to Train Your Dragon franchise, since 2010) and Blue Sky Studios (for example, the Rio franchise, since 2011).

The plot of Happy Feet concerns Mumble’s struggle for acceptance within the colony. Unable to develop an individual heartsong with which to woo a mate, he expresses himself through tap dancing and grows up an embarrassing misfit. The elders exile him, claiming that his offensive toe-tapping is responsible for the lean fishing season. Mumble – accompanied by a Rockhopper penguin-guru called Lovelace (Williams) and a motley crew of Adélie penguins led by the sex-crazed Ramon (also Williams) – sets off on a perilous quest to find those truly responsible for the reduction in fish: the rumoured ‘aliens’ (humans) at the ‘Forbidden Shore’. Ultimately, Mumble returns with some humans in tow and persuades his colony to unite in a mass display of tap dancing; the subsequent TV footage of this spectacle compels mankind to stop destroying the food and habitat upon which the colony depends, restoring ecological balance.

The digital technology used in Happy Feet allowed for breathtakingly accurate renditions of the Antarctic landscapes, and also the flexibility to animate individual penguins independently during shots of the entire Emperor colony dancing (one scene showing half a million birds) or to animate any of Mumble’s six million feathers during close-ups (Byrnes Reference Byrnes2015). These stunning visual details led to the animation winning an Oscar and a BAFTA award in 2007 for Best Animated Feature. The actual content of the film proved more controversial than its technical artistry. On the film’s release in November 2006, some right-wing media commentators in the United States roundly condemned it as subversive propaganda because of its overtly anti-religious/anti-authoritarian stance, its pro-environmental messages regarding the impact of overfishing and man-made pollution and its pro-gay subtext – the latter due to Mumble’s being ‘different’. (For a sample of such reports, see Dietz Reference Dietz2006 and Boehlert Reference Boehlert2006.) There are also many dark aspects to the story: Mumble is attacked by a series of increasingly larger predators and other dangers (skuas, a leopard seal, killer whales and the propeller of a fishing vessel) and ‘loses his mind’ when captive in a zoo. Scary moments in children’s animation are not a new phenomenon – for example, they occur in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Watership Down (1978) – and Miller had already demonstrated in his earlier screenplays for Babe (1995) and Babe: Pig in the City (1998) that he was not afraid to incorporate challenging topics within family-oriented fare. Yet there was an obvious disparity between the cinema marketing campaign for Happy Feet and the film’s actual content. The official trailers glossed over the excessively nightmarish aspects and completely omitted the environmental topics; the only ‘warning’ on film posters was ‘May cause toe-tapping’. Many parents with very young children were therefore completely unprepared for the film’s true content, which was understandable given the G (General) or U (Universal) ratings it received in Australia and the United Kingdom, respectively, but perhaps less so in the United States, where the film was given the stronger PG rating due to scenes of ‘mild peril and rude humor’. The New Zealand film classification agency also swiftly changed the film’s initial rating from G to PG after receiving complaints from the public (see New Zealand Government 2015).

Happy Feet has received little attention from academic writers. It has been included in some ‘ecocritical’ studies of US animations from the 1930s onwards (Murray and Heumann Reference Murray and Heumann2011; Pike Reference Pike2012), which conclude that pro-environmental messages in ‘enviro-toons’ like Happy Feet and The Simpsons Movie (2007) can be a more effective way to instigate public debate than environmental journalism, but they do not result in environmental activism. Philip Hayward (Reference Hayward and Coyle2010) has written a brief survey of Powell’s original score and the pop songs interspersed within it either as diegetic performance by the animated characters (singing and dancing) or as nondiegetic underscore. His concluding remarks highlight how the sonic text often undermines the ‘notionally liberal [and] eco-progressive’ stance of the film, easily enabling it to ‘be read in terms of … entrenched racial stereotyping in US society’, with the Emperor penguins representing the WASP mainstream and the wily Adélies as parodic Hispanics (Hayward Reference Hayward and Coyle2010, 101). He also draws attention to the white appropriation of black culture:

Musically, many of the featured songs originate from African American performers and/or genre traditions [soul, R&B, rap], yet the most prominent vocal performers are Euro-Americans … [Moreover,] Glover’s tap dance routines … do not register in the film’s copyright music credits. His work is heard but invisible, rendered incidental, unheralded and unremunerated by royalties despite its central role in the film and its soundtrack – an unfortunate endnote to a film about tolerance, inclusivity and equality of creative expression.

Tanine Allison has expanded upon this theme, suggesting that ‘motion capture acts as a medium through which African American performance can be detached from black bodies and applied to white ones, making it akin to digital blackface’ (Reference Allison and North2015, 115), and citing the conglomeration of Glover’s tap dancing with Wood’s voice as the prime example. (The social/racial stratification of the penguins in Happy Feet does have some positive elements: for example, the Adélie penguins wholeheartedly embrace Mumble as one of their own, despite his obvious differences.)

Popular song has been omnipresent in the soundtracks of animated features financed by US studios since the 1930s. Whereas Disney continues its longstanding tradition of commissioning original songs, many other animation studios have opted to raid the twentieth century’s back catalogue of commercial hits from the US and UK charts. This trend parallels the advent of fully computer-generated animations in the 1990s; DreamWorks’ Antz (1998) and Shrek (2001) are early examples. As in their use in live-action film soundtracks, these songs are chosen for the appropriateness of their lyrics to the scene in question, the general cultural vibe which they evoke or the expedient way in which they can act as a surrogate for unstated sentiment; they can appear as part of the underscore or be performed directly by the characters; they often have a humorous intent; and they invoke nostalgia in those who recognize the sources (typically the older members of the audience). Such uses of pre-existing popular song were also endemic to the anarchic cartoon shorts issued by Warner Bros. from the 1930s onwards. Also in keeping with the tradition of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck et al. is the penchant for modern-day animated characters (at least one per film) who break into song mid-speech and pepper their dialogue with identifiable song lyrics and other pop-culture references (say Donkey in Shrek and Ramon in Happy Feet). The Simpsons (airing on television since 1989) and Pixar’s Toy Story franchise (since 1995) have proved to be highly influential templates for re-introducing this approach, tapping into (and helping to create/propagate) the accumulating database of postmodern pop-culture.

The Happy Feet soundtrack is demonstrably more musically intricate and varied than those in many animated feature films, being a complex weave of forty-one (credited) pre-existing songs – a mixture of ‘popular’ and ‘pop’ spanning just over a century from 1892 to 1999 – and Powell’s orchestral score. (There are also the now ubiquitous new pop-song tie-ins placed in the end credits to promote the film, namely Prince’s ‘Song of the Heart’ and Gia Farrell’s ‘Hit Me Up’; other occasional song lyrics, uncredited, have influenced the dialogue.) Around half of the songs are concentrated into two mating scenes in the form of mashed-up song lyrics sung by the penguin characters, the first (in the opening sequence) showing how Mumble’s parents met and the second Mumble’s clumsy attempts at attracting his childhood sweetheart Gloria (Murphy). During the four-year gestation of Happy Feet, Miller and Powell collaborated closely over the selection of pre-existing music, which accounts for about twenty-five minutes of the soundtrack. Much time and effort was expended in choosing and re-working pop songs in order to fit the dramatic requirements and most ideas were discarded in the process – Powell estimated that their success rate was probably only five per cent (Goldwasser Reference Goldwasser2006). It can therefore be assumed that these two mating scenes, though accounting for about 11 minutes of the finished film length (108 minutes), took a disproportionate amount of Powell’s time in production and development.

Introducing the ‘Lullaby of Antarctica’

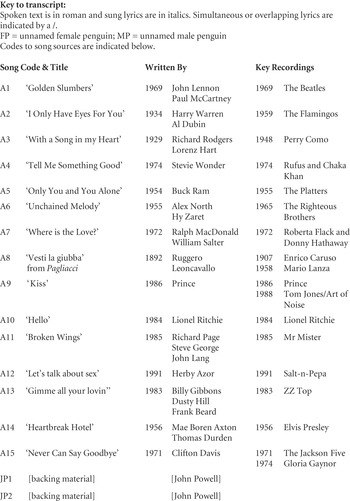

Happy Feet has one of the most ambitious and arresting opening sequences in a feature-length animation. It sets the scene on a cosmic scale, going from the macrocosm of outer space to the microcosm of the penguin colony. (Similar openings can be found in Miller’s Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome from 1985 and Pixar’s WALL-E from 2008.) In less than four minutes, the audience is shown how Mumble’s parents Norma Jean (Kidman) and Memphis (Jackman) met and created his egg. The dialogue is minimal; instead the narrative impetus is provided by a collage of fourteen song quotations, plus a fifteenth in a short coda joined by some bridging material written by Powell. For a transcript of the scene, together with the sources of the songs, see Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Transcript of the first mating sequence and song sources in Happy Feet.

|

|

|

|

|

A voice-over in a trailer to Happy Feet made it clear that ‘In the heart of the South Pole, every penguin is born with a song to sing – everyone except Mumble’. It helps to be aware of this basic premise in advance and to be acquainted with how Emperor penguins find a mate – the latter supposedly common knowledge since Luc Jacquet’s documentary March of the Penguins (La marche de l’empereur) was released in 2005 – in order to understand the primary narrative function of the (sometimes disembodied) song lyrics in the opening scene. The initial lack of action gives the soundtrack beneath the title sequence a special prominence. As the shape of a giant penguin amidst a galaxy of stars emerges from the blackness, we hear the melodies of two intertwined songs with minimal accompaniment. These are k. d. lang singing ‘Golden Slumbers’ (in what proves to be the role of a narrator) and a male voice singing lines from ‘I Only Have Eyes for You’, the latter written for Dames (1934). At this point it is unclear whether or not we are hearing underscore. This opening is reminiscent of the number ‘Lullaby of Broadway’ (Harry Warren and Al Dubin, 1935) in Busby Berkeley’s Gold Diggers of 1935, which begins (and ends) in total blackness with the title song emanating from an invisible source. In Happy Feet, lang’s lines ‘Sleep pretty darling do not cry / And I will sing a lullaby’ also suggest that what follows will be a spectacular and musical fantasy: a ‘Lullaby of Antarctica’. (Miller pays homage to Berkeley’s distinctive choreographic style elsewhere in the film where the penguins’ underwater formations briefly make kaleidoscopic patterns typical of those in the ‘By a Waterfall’ routine from the 1933 backstage musical Footlight Parade.)

The ‘camera’ then hurtles us through space – past a red-hot planet emblazoned with the film title – and through Earth’s atmosphere into the penguin colony. En route we hear more fragments of songs from unseen voices (mostly male) intertwined with some spoken lines from a female – soon to be revealed as Mumble’s mother Norma Jean – who is overwhelmed at hearing ‘So many songs’. The line ‘Ridi, Pagliacci’ from the famous tenor aria ‘Vesti la giubba’ ends the final cacophony with a dash of late nineteenth-century Italian opera before the penguins finally come into view. Only now does it become apparent that we have been overhearing Norma Jean as she wanders around the colony (as a real Emperor penguin would), listening to the heartsongs of various males in the hope of finding her one true love. She launches into her own heartsong, an upbeat rendition of the opening verse and chorus from ‘Kiss’. The accompaniment is rendered through minimal rhythm and bass, throwing the vocal lines into sharper relief. Heartsong incipits (typically only one or two lines long) from more male suitors are expertly woven around her phrases in the manner of a Club DJ using multiple turntables. Norma Jean ignores them all until her attention is finally grabbed by Memphis and his rendition of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’; their union was pre-destined in her spoken line from this song (‘I’m feeling so lonely’) before she even met him. As Memphis stands before her on a mound of ice, he sings his courtship call (first verse and chorus) and stretches out his wings in an obvious impersonation of Elvis Presley. In time-honoured fashion from opera, operetta and musical, the pair signify their mutual attraction and impending union by instinctively being able to sing lines from each other’s songs in the manner of a love duet.

The official soundtrack recording (Warner Sunset/Atlantic 756783998–2, 2006) features a version of the ‘Kiss’/‘Heartbreak Hotel’ duet which is different from the film soundtrack in two key aspects. First, the breadth of the film’s opening has been curtailed, the track starting just before Norma Jean’s first spoken line (‘But how can you know for sure?’); and, second, the pre-existing pop songs interwoven with ‘Kiss’ have been entirely replaced by innocuous backing material supplied by Powell and his team, presumably for copyright reasons. This makes the album track anodyne in comparison with the opening of the film soundtrack.

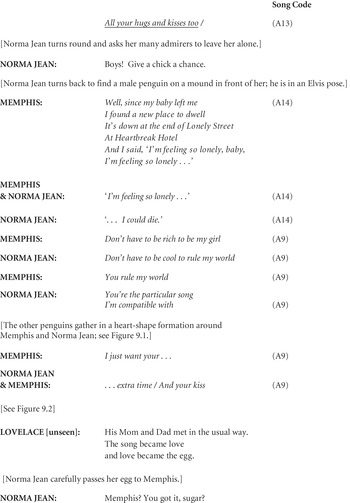

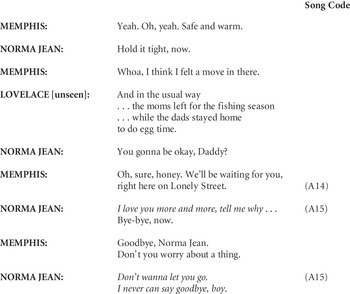

The sophisticated beauty of the opening scene was lost on the reviewer in Sight & Sound, who reckoned that it ‘may put some viewers off the picture, as we’re thrust into the midst of CGI penguins mouthing pop and rock numbers in a kitsch parody of Moulin Rouge (2001)’ (Osmond Reference Osmond2007, 56). Hayward also noted how the presence of Kidman and the ‘use of disjunctured, “mashed-up” song dialogues between romantically aligned characters’ has marked similarities to Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Elephant Love Medley’ sequence in Moulin Rouge! when Christian (Ewan MacGregor) and Satine (Kidman) ‘exchange snippets of seminal popular love songs’ (Reference Hayward and Coyle2010, 95). Miller’s reference to this iconic love duet is much more than a kitsch parody or a token acknowledgement of fellow Australian artistry: it is dramatically apposite for the union of Mumble’s parents and constitutes a beautiful, albeit extremely brief, celebration of romantic love. Miller draws deliberate visual parallels by using Luhrmann’s trademark heart shapes (Armour Reference Armour2001, 9). Just as the romance between Satine and Christian is framed by a heart-shaped window and culminates in a kiss, so Norma Jean’s and Memphis’s courtship takes place within a heart-shaped space formed by the other penguins (see Figure 9.1) and the pair mark their union in accordance with real Emperor penguins by throwing back their heads, bowing and bringing their beaks together in a heart shape (see Figure 9.2). For real Emperor penguins, this ‘bowing’ often precedes copulation and is also associated with egg-laying (T. Williams Reference Williams1995, 157). Sure enough, as a coda to the first mating scene the narrative moves swiftly to the new parents with their egg, which Norma Jean entrusts to Memphis, singing ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’ as she and the other ‘wives’ bid farewell and leave for a fishing trip.

Figure 9.1 Happy Feet: the penguins make a heart-shaped formation around Norma Jean and Memphis.

Figure 9.2 Happy Feet: Norma Jean and Memphis bring their beaks together, forming a heart shape.

The essential purpose and necessity of heartsongs is only explained once the film is well underway, when a young Mumble and the other penguin chicks attend a special singing class. Here, the teacher, Miss Viola (Magda Szubanski), encourages her young charges to try out the song they can hear inside themselves, informing them that ‘Without our Heartsong, we can’t be truly penguin, can we?’ (Thus Mumble’s fate as a misfit is sealed.) The audience is given a foretaste of the second mating scene when two chicks, Gloria (Alyssa Schafer) and Seymour (Cesar Flores), attempt their heartsongs in embryonic form (the first verse of ‘Boogie Wonderland’ and the chorus from ‘The Message’, respectively; for song sources, see Table 9.2).

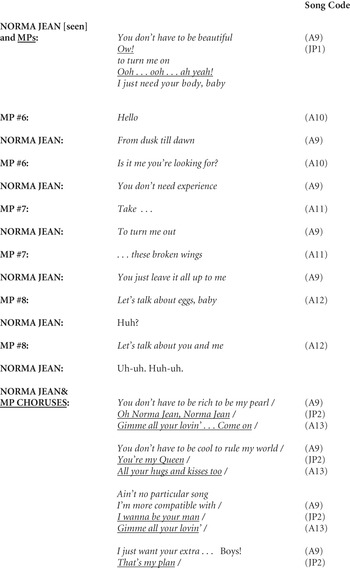

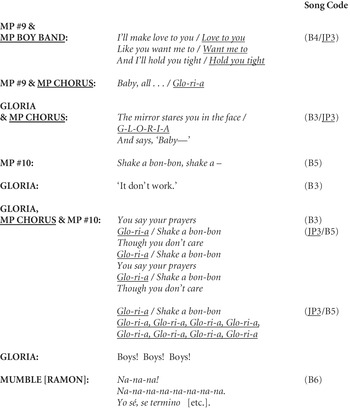

Table 9.2 Transcript of the second mating sequence and song sources in Happy Feet.

|

|

With the audience now fully conversant in the courtship rituals of these singing penguins, it seems entirely natural for the adult Gloria to be bombarded with lyrics from different songs when she is looking for a mate in the second mating sequence. Whilst the introduction and structure mirrors the opening sequence from the extreme-long shot of the colony onwards, in other ways this second sequence is the complete opposite of the first. It uses far fewer songs (six) yet is longer (over seven minutes) because it concludes with large quantities of dialogue and a mass dance extravaganza. Crucially, the narrative outcome is different because the anticipated union of Mumble and Gloria is thwarted. For a transcript of this scene (up to the point at which Mumble ‘sings’) and a list of song sources, see Table 9.2. Gloria – singing the first verse from ‘Boogie Wonderland’ in a slower, more soulful tempo than the original recording by Earth, Wind and Fire – meanders through bands of male penguins who compete for her attention by bombarding her with their heartsong incipits. Again, the accompaniment is an embryonic rhythm and bass; the harmonies are mostly provided by the choruses of male penguins. Gloria quickly stops and turns to scold her suitors (as Norma Jean did) and then is confronted by Mumble on a mound of ice, just as his father had appeared before Norma Jean. He attempts to woo her with a rendition of ‘My Way’ in Spanish, backed by his Adélie friends, but she quickly realizes that he is only miming – Ramon is the real singer – and turns away in dismay. Mumble then persuades Gloria to sing to the rhythm of his tap dancing, and she reprises the verse of her heartsong at a faster tempo, leading to a rousing uptempo version of the chorus which ‘featur[es] Mumble’s tap patterns as a polyrhythm’ (Hayward Reference Hayward and Coyle2010, 96). Unable to resist the ‘groove’, their entire generation of penguins joins in the dance until the elders put a stop to the frivolities and exile the aberrant toe-tapper.

Soft-Porn Penguins?

Whilst the soundtrack consists of an eclectic mélange of songs from several decades, the majority are a mix of iconic R&B, Motown and hip-hop numbers, originally recorded by non-white solo artists and vocal groups (see song sources in Tables 9.1 and 9.2) – hence the criticism that Happy Feet narrates, ‘however indirectly, the white appropriation of black culture’ (Allison Reference Allison and North2015, 114). Many of the animated penguins adopt the choreographed movements associated with their particular artist and the original performance context of the song, on stage or in music videos. This ranges from Memphis striking an Elvis pose before singing ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ in the first mating scene to a penguin ‘boy band’ in the second, who pester Gloria with their Boyz II Men parody (‘I’ll make love to you’) after which a male penguin wiggles his behind like Ricky Martin and entreats her to ‘Shake a bon-bon’. Certain characters carry over their musical personae into their dialogue and general demeanour: Memphis is clearly a ‘Southern boy’ with conservative views; and Seymour – even as a chick – has a bigger build than all the other penguins, like the American rapper Fat Joe who provides his adult voice. Such stereotyping can seem crude and offensive, but these rapid audiovisual cameos are a particularly efficient means of differentiating the main characters when the majority of penguins are indistinguishable from each other.

Miller and Powell made no attempt in these mating scenes to assign songs from one chronological period to a particular generation of penguins. Norma Jean sang ‘Kiss’ from the 1980s alongside Memphis’s ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ from the 1950s, whilst the next generation, Seymour and Gloria, had classics from the early 1980s and late 1970s, respectively. Older members of the audience should easily recognize the mashed-up pop-song selections and find them comic in their juxtaposition and in the incongruity of their new context; younger viewers need only follow the basic narrative, drawn in by the novelty of cute penguins singing and dancing to a groovy beat. Powell produced the two mash-up sequences to an exceptionally high standard; they are slick and have seamless transitions between the disparate elements. Despite the confines of working with other peoples’ song materials, there is still much originality evident in their combinations and production. Although all the song fragments are performances in the sense that the penguins are putting on a display to attract a mate, their function is categorically narrative and the song mash-ups are an expedient and apposite means of rendering the mating rituals musically. (The mating displays are also clear examples of how sound – particularly music – is often the catalyst driving the creation of the animated image and is at the core of its meaning and affect: see Paul Wells in Chapter 16 of this volume.) Indeed, it would be easy to re-imagine the first mating scene in the context of Moulin Rouge!, with Satine searching for her true love amidst a lascivious throng of men (appropriately dressed like penguins in black tie and tails) at the eponymous nightclub. However, the racy lyrics and choreography in this – and the second – mating scene are much more challenging within the context of an animation aimed at a family audience. (Christian commentators in the United States have picked up on this aspect more than mainstream reviewers: see Greydanus Reference Greydanus2006.)

The content of some songs was rendered more innocent chiefly by avoiding the narratives in the verses, sticking instead to the more memorable hook of a catchy chorus (for example, ‘I’ll make love to you’; ‘Gimme all your lovin’ ’; Shake your bon-bon’). In the case of ‘The Message’, using only the chorus avoided its grim narrative about inner-city violence, drugs and poverty. Other songs were tweaked to fit better with penguin society (and avoid receiving a higher-rated certification): ‘Let’s talk about sex’ became ‘Let’s talk about eggs’. Less easily dismissed are the heartsongs chosen for Norma Jean and Gloria (‘Kiss’ and ‘Boogie Wonderland’), whose lyrics received only minimal changes. For example, the opening verse of ‘Boogie Wonderland’: ‘Midnight creeps so slowly into hearts of those [men] who need more than they get, Daylight deals a bad hand to a penguin [woman] who has laid too many bets’ (the original words are indicated in square brackets). Whilst the message in the chorus is straightforward and appropriate to Happy Feet (‘Dance, Boogie Wonderland’), the opening verse seems a bizarre choice, given its narrative about a woman who is constantly searching for romance on the dance floor to dull the pain of her many loveless relationships with men; this also creates a gratuitous and unlikely backstory for Gloria.

Both female protagonists have human-like buxom, curvaceous bodies which are in stark contrast to the more penguin-like males surrounding them, and both give highly sensualized performances of their songs. Gloria, in particular, seems to be overtly aroused by Mumble’s tap dancing and is inescapably drawn to his ‘groove’. Norma Jean is patently cast in the mould of Marilyn Monroe by using the screen siren’s real forenames and through Kidman’s breathy singing style. Edward Rhymes (Reference Rhymes2007) has noted how celebrity status and artistic legitimacy have been accorded to certain white females like Monroe who are allegedly recognized more for their sexual assets than for any innate talent, yet black women (say in hip-hop videos) acting out the same behaviour are demonized for their sexual promiscuity and immodesty. It is therefore a strong statement for the ultra-white Kidman in the guise of Monroe to sing the extremely raunchy lyrics in ‘Kiss’, a song generally associated with male singers (Prince and Tom Jones). Rhymes would regard such a decision as having ‘“deified” and normalized white female explicitness and promiscuity’ (ibid.), despite the cloak of ‘digital blackface’ (Allison Reference Allison and North2015, 115) provided through the filter of an animated penguin.

The two mating sequences in Happy Feet, in appropriating ‘sexed-up’ songs and choreography from the music industry to portray lone, hypersensualized female penguins being pursued by groups of clamouring males, typify the soft-porn styling that is now endemic to many media forms. Concerns about the increasing ‘pornification’ of popular culture and the negative effects this is having on young people had already been raised by commentators in the United States prior to the release of Happy Feet. For example, Don Aucoin wrote in the Boston Globe:

Not too long ago, pornography was a furtive profession, its products created and consumed in the shadows. But it has steadily elbowed its way into the limelight, with an impact that can be measured not just by the Internet-fed ubiquity of pornography itself but by the way aspects of the porn sensibility now inform movies, music videos, fashion, magazines, and celebrity culture …

What is new and troubling, critics suggest, is that the porn aesthetic has become so pervasive that it now serves as a kind of sensory wallpaper, something that many people don’t even notice anymore …

But it is perhaps the world of popular music where the lines between entertainment and soft-core porn seem to have been most thoroughly blurred. It is now routine for female performers to cater to male fantasies with sex-drenched songs and videos.

It is telling that Happy Feet received classifications for theatrical release in Europe and North America which overlooked the raciness inherent in the lyrics and choreography. Moreover, the film examiners appear to have missed (or ignored) a latent porn reference: the Rockhopper penguin guru is called Lovelace – after Linda Lovelace in Deep Throat (1972) – and wears a ‘sacred necklace’ (a set of plastic six-pack rings) which eventually begins to choke him (see Massawyrm Reference Massawyrm2006; Osmond Reference Osmond2007, 56). The use of (barely disguised) sexual content in Happy Feet is merely part of an ongoing market trend. A 2004 study by the Harvard School of Public Health, reported in the New York Times, highlighted how ‘a movie rated PG or PG-13 today has more sexual or violent content than a similarly related movie in the past’ (cited in N. Brown Reference Brown2012, 278). Soft-porn styling and barely disguised racy lyrics in supposedly family-friendly fare are also present in Miller’s sequel Happy Feet Two (2011; again scored by Powell). This begins with a grand song-and-dance medley of pop songs performed by different sections of the Emperor penguin colony, in which the next generation of male chicks, led by Seymour’s son Atticus (Benjamin Flores Jr), do a break dance to the hip-hop song ‘Mama said knock you out’ (LL Cool J, 1990) – re-worded ‘Papa said knock them out’ – and the irresistible snow-covered female chicks respond with ‘We’re bringing fluffy back’, wiggling their behinds and urging us to ‘Get your fluffy on / Shake your tail’ in a brief mash-up of Justin Timberlake’s ‘Sexyback’ (2006) and Mystikal’s ‘Shake it Fast [Shake ya ass]’ (2000).

Who, exactly, was the target audience for Happy Feet? Walt Disney aimed his early animated features at an undifferentiated ‘child of all ages’ (a child-adult amalgam later identified by the American TV industry in the early 1950s as the ‘kidult’), whereas his live-action family movies gradually introduced a change in focus to an adult, middlebrow audience (N. Brown Reference Brown2012, 153 and 195). Arguably, films such as Happy Feet and its sequel also virtually ignore the young children at whom much of the merchandizing and marketing is aimed. Instead, the main target audience comprises adolescents and youth-obsessed middle-aged adults, the latter group now forming the biggest demographic in the Western world (and hence the one with the greatest potential spending power).

The annual Theatrical Market Statistics for the US entertainment industry (issued by the Motion Picture Association of America) since 2001 show a marked trend towards standardization of product, with films rated PG-13 (typically the blockbuster franchises based on comic books and toys) and PG accounting for around 80 per cent of the twenty-five top grossing films each year. (PG-13 films have supplanted films rated R (Restricted), which require a parental presence for any viewers under the age of 17, as the dominant group.) Notably, the vast majority of animated features receive a PG rating in the United States; the G rating is virtually obsolete. This in itself is indicative that many films nominally suitable for young children now regularly contain more adult content. In the case of Happy Feet, there are obvious aspects of its script, soundtrack and visual styling which may even suggest a PG-13 rating. Robin Murray and Joseph Heumann might suggest that these aspects are ultimately counterproductive and damage Miller’s heartfelt pro-environmental message, because in ‘enviro-toons’ such as Happy Feet, ‘the call to [environmental] action is diluted by the ongoing call to buy’ (Reference Murray and Heumann2011, 244).

Miller strengthened his warning about impending environmental disaster in Happy Feet Two, urging us all to unite in our aim to stop the effects of climate change. Jacquet also returned to the Antarctic to make the documentary Ice and the Sky (La glace et le ciel; 2015) about the career of veteran French glaciologist and climate-change expert Claude Lorius.The French director was shocked to see how, since his last trip to the continent, climate change has increased temperatures, introducing unprecedented rainfall – with devastating effects on the survival of penguin chicks (MacNab Reference MacNab2015). The giant panda might be the best-known ‘poster animal’ for environmental conservation, but in the world of cinema another black and white animal, the Emperor penguin, is the one still trying to get our attention.