Amy Beach was a prolific composer for the piano. As a teenager, she had a blossoming career as a concert pianist curtailed by her mother, who did not wish her to tour, and her husband, who encouraged her to compose. Beach herself wrote that while she made the switch to focusing on composition upon her marriage at the age of eighteen, she, at the time, had thought herself “a pianist first and foremost.”1 This aptitude as a pianist comes through in her piano compositions: Beach wrote fluidly for the piano, knowing the instrument intimately herself. Her pieces range from simple, more pedagogic works, through to character pieces and virtuosic works requiring an advanced piano technique. This chapter will explore Beach’s prodigious oeuvre for piano solo, concluding with a brief discussion of her pieces for organ, piano duet, and two pianos.

The Early Piano Pieces

Beach’s musical gifts were obvious from an early age: she was singing before she could speak, had perfect pitch, and had a remarkable musical memory. Her mother kept her away from the family piano until she was four, as she did not want Beach to have the life of a musical prodigy. Mamma’s Waltz, her earliest extant piece for piano, along with Snowflake Waltz and Marlborough Waltz, were “written in her head” while visiting her grandfather’s farm in Maine.2 Beach herself notated Mamma’s Waltz several years later in the manuscript that survives, with the annotation, “Composed at the age of four years.”3 Mamma’s Waltz is in simple rondo form, with two interspersed sections contrasting with the opening material.4

Beach’s mother limited her time at the piano and began to teach her piano formally only at the age of six. By seven, Beach was playing Bach fugues, Chopin waltzes, and a Beethoven sonata, as well as performing in public. She was offered contracts by several concert managers, all turned down by her parents. In 1875 her family moved to Boston, and in 1876 Beach began to study privately with the pianist Ernst Perabo, who taught at the New England Conservatory of Music.

Several pieces survive from this period. Menuetto (1877), Romanza (1877), and Air and Variations (1877) were all written when Beach was ten years old. Menuetto is a precursor of the Menuet italien, op. 28, no. 2. The first half of the piece is in rounded binary form, followed by the main theme presented in the parallel minor. A short harmonic progression leads to the final phrase, a restatement of the theme that ended the binary section. Romanza shows Beach experimenting with modulation as she moves skillfully from the opening key of D major into F-sharp major eight bars later.

Air and Variations is a larger work and evidence of Beach’s technical development as a pianist. The theme is first presented simply in A minor. The variation that follows requires repeated-note facility in the right hand. The second variation moves into F major with sextuplet patterns and then returns to A minor for an energetic presto variation. A final variation, with the melody in the left hand accompanied by groups of four running up and down the keyboard, brings the set to conclusion.

Petite Valse (1878) is a charming waltz in D-flat major, a forerunner of the Danse des fleurs, op. 28, no. 3. Beach uses a structural organization similar to Menuetto: a binary form is followed by a move to the parallel minor, with a nicely handled modulatory sequence back to a statement of the opening melody in D-flat major.

Moderato, an undated piece in handwriting similar to the pieces just mentioned, so perhaps of a similar date, survives in manuscript with a single bar at the bottom of the first page lost due to a torn corner (completed by the author on her recording of this piece).5 The mood Beach creates with Moderato is magical: the static writing, with a rising arpeggio in the first part of every bar leading to longer melodic notes, and subtle shifts of harmonic color come together to form a miniature gem.

In 1882, Beach began studying piano in Boston with Carl Baermann, a pupil of Liszt’s. Her mother permitted her to make her debut in 1883 at the age of sixteen with Ignaz Moscheles’s Concerto No. 2 in G minor in Boston’s Music Hall. Beach performed as a recitalist and concerto soloist in and around Boston for the next several years, though her mother did not allow her to tour extensively, nor would she permit her to go to Europe for further study.6

Piano Pieces Composed After Her Marriage

Upon her marriage in 1885, Amy Marcy Cheney became Mrs. H. H. A. Beach. Her husband did not wish for her to accept performance fees, but he did allow her to play in aid of charities and encouraged her development as a composer. Beach’s next surviving work for piano is an excellent Cadenza (1887, published 1888) written for the first movement of Beethoven’s third piano concerto.7 Nine pages in length, it uses scales, octaves, and trills to explore Beethoven’s motives in a most effective manner, requiring virtuoso technique.

Beach’s next solo work, Valse Caprice, op. 4, was premiered in 1889 by the composer herself. The figuration of the opening introduction is as if a curtain is being raised at a ballet. And then the dance begins. Beach decorates the melody with light grace notes, lending an improvisatory and capricious air to the work. The piece was championed by the pianist Josef Hofmann (1876–1957), who used it frequently as an encore.

Beach uses her song, “O my luve is like a red, red rose,” op. 12, no. 3, as a basis for her wonderful Ballade, op. 6 (published 1894). Following a brief introduction, the melody enters, accompanied with flowing triplets between the hands. After setting out the theme, Beach begins again, initially in D-flat minor, with the melody in the left hand. The decoration in the right hand becomes more elaborate and passionate, with beautiful piano writing. An Allegro con vigore ensues, portraying Robert Burns’ words of the third stanza of Beach’s art song: “Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear; And the rocks melt wi’ the sun; I will luve thee still, my dear; While the sands of life shall run.”8 Bold and tempestuous, this builds in a fervor of emotion to a climax. From the sustained unison octaves emerges a pianississimo Lento, a quasi-cadenza on the opening melody. The material from both sections is combined, building to a final statement of the theme in large chords and octaves. Utterly depleted, Ballade winds down, fading into the distance, ending exquisitely still.

Sketches, op. 15 (published 1892), is a four-movement work, each piece preceded with a line of poetry. The first, “In Autumn,” is annotated, “Feuillages jaunissants sur les gazons épars” [“Yellowed leaves are scattered on the grass”], an excerpt from a poem by Alphonse de Lamartine. In F-sharp minor, it is jaunty and light, reminiscent of Schubert. At the beginning of the second piece, “Phantoms,” Beach quotes a line by Victor Hugo: “Toutes fragiles fleurs, sitôt mortes que nées” [“All the fragile flowers die as soon as they are born”]. “Phantoms” is in 3/8, in ABA form, with an emphasis on the second beat of the bar, lending a mazurka-like feel.9 “Dreaming” quotes another excerpt by Hugo, “Tu me parles du fond d’un rêve” [“You speak to me from the depths of a dream”]. It opens with triplet figuration between the hands, which continues throughout, with long notes conveying the melody. Another quotation from Lamartine is used under the title of the virtuosic final piece, “Fireflies”: “Naître avec le printemps, mourir avec les roses” [“To be born with the spring, to die with the roses”]. Passages in double thirds in the right hand convey the flitting of fireflies as they light up the night sky. This piece was played by Ferruccio Busoni, Josef Hofmann, and Moritz Rosenthal, giving evidence of the spread of Beach’s works during her lifetime.

Bal Masque, op. 22 (1893, published 1894), is a waltz in the Viennese tradition. It demonstrates Beach’s affinity with the form, having heard her mother play Strauss waltzes at the piano from her infancy. In ABA form, the first section is preceded by a short introduction establishing the key of G major. The middle section in E-flat major is warmer and more intimate in sound. Beach decorates the “A” material in the restatement of the theme, imitating various woodwind instruments in her working of the material. Her orchestral arrangement of this work is discussed in Chapter 8.10

Trois morceaux caractéristiques, op. 28 (1894), opens with “Barcarolle,” a lovely evocation of a boat-song. In 6/8 time, the undulating left-hand accompaniment provides an ongoing support for the cantabile melody. Set in ABA form, the middle section introduces a new melody in the left hand, which is developed expansively with full chords. After reaching a climax, Beach backs away, with a tranquillo setting of this melody ushering in an embellished restatement of the opening theme. The second piece, “Menuet italien,” is an expanded version of Beach’s childhood Menuetto. Beach uses much of the same material, but in a more complex way, adding passing tones and secondary lines. It is a larger work: there is now a middle section in C minor, with artfully written passagework decorating the line. “Danse des fleurs,” marked Tempo di Valse, is the final morceau. In D-flat major, the opening theme dances between the hands. The second theme, with a longer line, is beautifully presented in the key of C-sharp minor. Clever motivic development, requiring pianistic dexterity, builds to a climax before Beach returns to the opening melody to finish lightly.

Some Pedagogic Pieces

Often the line is blurred between pedagogic and concert repertoire, epitomized by Beach’s two sets of pieces for “children.” While they may be less complex than her longer and technically challenging larger works, the pieces are worthy and appealing as concert program fillers or encores. It takes a master to write simply but effectively, and Beach shows her skill in these charming, delicate, and nuanced pieces.

Children’s Carnival, op. 25 (1894), is a set of miniatures that depict a carnival festival using characters whose roots lie in the Italian commedia dell’arte. The set opens with a march, “Promenade”: the procession of entertainers through city streets. Next is “Columbine,” a quiet piece inspired by the character of a young woman, sometimes portrayed as the lover of Harlequin. “Pantalon,” the next movement, is based on the eponymous character, an older man who is often cast as the father of Columbine. “Pierrot and Pierrette” follows, a gentle waltz in two parts, each section repeated. Pierrot and Pierrette are two clowns: Pierrot is desperately in love with Pierrette, but she falls in and out of love with him. “Secrets” is a lovely andantino with the melody hidden between the hands, a duet of two voices juxtaposed on different parts of the beat. Children’s Carnival concludes with “Harlequin,” the acrobat of the menagerie, conveyed in a quick, light melody that dances around the keyboard.

Children’s Album, op. 36, was written in 1897,11 the year after the premiere of Beach’s “Gaelic” Symphony and the composition of Sonata in A minor for piano and violin. A suite of pieces in classic musical forms, it opens with “Minuet,” a charming composition in three parts. The first section is in rounded binary form, followed by a trio and then the return of the opening section. The next movement, “Gavotte,” harks back to the French court dance of the same name. In “Waltz,” Beach sets a long melody over a waltz pattern in the left hand for this gentle reminiscence in ABA form. The fourth movement, “March,” is a sprightly dance of dotted rhythms with the odd three-bar phrase thrown in to set the marchers off-kilter. A lively “Polka” ends Children’s Album: marked scherzando, a sense of fun pervades as the phrases bubble one after the other.12

The Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Beach’s first solo piano piece of the twentieth century is Serenade (1902), a beautiful transcription of Richard Strauss’s Ständchen, op. 17, no. 2.13 Beach’s handling of Strauss’s material transforms the original work in a highly compelling transcription for piano. She cleverly incorporates the sung line in among the rippling accompaniment, beautifully rendering Strauss’s setting of the words by nineteenth-century German poet Adolf Friedrich von Schack. The opening stanza is in the same register as Strauss’s original, but the second verse is set down an octave by Beach, with occasional forays into the upper register of the piano to end vocal phrases. In the next section, when Strauss moves into D major, Beach begins with the melody in octaves in the bass of the piano to take the listener into “the twilight mysterious under the lime trees.” The piece is mostly faithful to the original score except at the climax, where Beach expands the material in a most effective way: she includes extra bars of arpeggiation and doubles the duration of the vocal pitches, as well as adding a pianistic flourish at the end.

Beach had a keen interest in folk music, evidenced in many of her compositions, including the first of the Two Compositions, op. 54 (1903). “Scottish Legend” is an original melody, evocative of Celtic origins, rising thrice as it builds to a peak before a denouement to the tonic D minor. The solemnity of the first section is juxtaposed with the slightly more animated middle section, in D major. “Scottish Legend” concludes with a truncated restatement of the opening, marked dolcissimo. The second piece, “Gavotte fantastique,” is based on the “Gavotte” of Children’s Album, op. 36: Beach uses this as a springboard for a more advanced showpiece. Trills and octaves enhance the template already established to make this a fantastical tour de force.

Variations on Balkan Themes, op. 60 (1904), is one of Beach’s seminal works for piano. Written in 1904, it is a substantial piece based on folk melodies that were introduced to Beach by Reverend William Washburn Sleeper and his wife, missionaries to Bulgaria. At a talk that Beach organized, Rev. Sleeper played some folk melodies that the couple had collected in their travels. Beach transcribed four of the melodies from memory several days after the presentation and used them as the basis for Variations, which she took just over a week to write.14 Beach wrote an orchestral version of the variations in 1906, including an extra variation.15 She revised the piano score of Variations in 1936 for her publisher, taking out repeats, transposing the funeral march and final statement into E-flat minor, and shortening the coda. Beach arranged the work for two pianos in 1937, using the 1936 version and including two extra variations. The following discussion is on the original version of 1904.16

The piece opens in C-sharp minor with a quiet chordal setting of the main theme, a Serbian folk melody entitled “O Maiko moyá.”

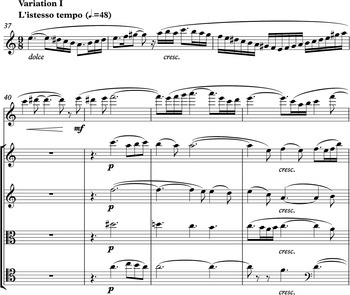

Beach restates the last line again, “Over whose fresh grave moanest thou so?” painting an especially bleak picture of utter melancholy. Beach continues in C-sharp minor for the first three variations. Variation I is a canon, with the left hand following the right in imitation; the second variation is a grand expansion of the theme, marked maestoso, with three beats to the bar; and the third variation is a light allegro in duple meter. For the next variation, a barcarolle, Beach moves to B-flat minor: beautifully set in binary form, parallel thirds and sixths support the melody over a simple accompaniment. The fifth variation, in G-flat major, begins with the left hand alone. In the tenth bar the right hand enters with decorative trills. The next phrase, now in E-flat minor, is again for left hand alone, with the right hand joining in after eight bars in a descant trill.

Variation VI opens in F-sharp minor with another Balkan melody, “Stara Planina.” Translated as “Old Mountain,” Stara Planina is the mountain range that divides northern and southern Bulgaria. This folk tune acts as an introduction, “quasi-fantasia,” to the actual variation on “O Maiko moyá,” which is marked Allegro all’ Ongarese [in Hungarian style]. As the sixth variation continues, Beach moves to F-sharp major and introduces a new melody, “Nasadil e dado” [“Grandpa has planted a little garden”]. This tune is taken into A major before returning to F-sharp minor to conclude the variation.

Beach returns to “O Maiko moyá” for variation VII, a slow waltz in E major. Variation VIII is a funeral march. There is a long introduction to the march based on the folk melody “Macedonian!” a mountain cry for help. “Macedonian” provides a desolate backdrop for the entry of a low trill, the rumble of which undergirds the funeral march. “O Maiko moyá” is stated simply in E minor, becoming grander and more tragic as the variation develops. The dotted rhythms of the march, coupled with full chords and tremolo in both hands, make the funeral procession a momentous occasion that builds to a climax before unraveling down to low trills in the bass of the piano, ending as quietly as it began.

An extensive cadenza follows, heralded by a quiet reflection on “Stara Planina.” Lovely arpeggios and passages in thirds ensue, leading to a section alluding to the maestoso of Variation II. Octaves and massive chords usher in a grand presentation of “Stara Planina,” which then winds its way down to a beautiful, still restatement of “Macedonian!” The opening theme returns, with Beach diverging from the original at the end of the third phrase, moving seamlessly into C-sharp major for the final cadence.

Beach’s interest in folk music continues to be evident in her use of Alaskan Inuit tunes in Eskimos, op. 64 (published 1907, revised 1943).17 The four pieces are based on melodies Beach found in a discourse by anthropologist Franz Boas (1858–1942).18 “Arctic Night” opens starkly, with the melody “Amna gat amnaya” first in unison between the hands and then supported by lush harmonies. Beach references “Song of a Padlimio” as the second melody, with its distinctive outlining of a minor seventh chord. The sprightly energy of “The Returning Hunter” comes in contrast, again beginning simply with an Inuit melody of the same name before being harmonized. A second Inuit tune, “Haja-jaja,” comes partway through, celebrating the nourishment brought by the returning hunter. In “Exiles,” headed lento con amore, Beach sets the folk tune “Song of the Tornit” and later uses “The Fox and the Woman” as a second melody. “With Dog-teams” opens with “Oxaitoq’s Song,” then races ahead in a lively presto based on “Pilitai, avata vat,” painting a brilliant picture of huskies skimming across a snowy landscape.

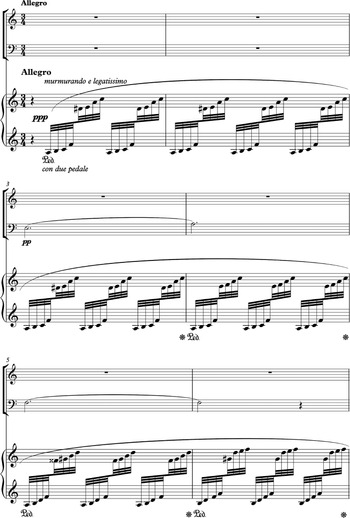

Begun in 1906, Les Rêves de Colombine: Suite française, op. 65, was completed in the spring of 1907, the same year in which she later finished her masterful Quintet for Piano and Strings in F-sharp minor.19 In Les Rêves de Colombine, Beach takes the French pantomime character Columbine, usually depicted as the daughter or servant of Pantalon and in love with Harlequin, as her inspiration. Beach uses traditional forms (prelude – gavotte – waltz – adagio – finale: dance) in the organization of her suite of Columbine’s dreams. In the first of these pieces, “La Fée de la fontaine,” Beach has Columbine visualizing the fairy of the fountain. Beach remarked that it was about “a capricious, a fierce and sullen as well as gracious fairy.” This is followed by “Le Prince gracieux,” a gavotte that imitates a prince who has caught Columbine’s eye dancing gracefully and lightly. The next piece, “Valse amoureuse,” is a romantic waltz, where Columbine dreams of “a sweetheart with whom she is dancing.”20 Beach used material from her song, “Le Secret,” op. 14, no. 2, as a basis for the waltz. This is followed by “Sous les étoiles,” a slow serenade in which Columbine gazes at the stars and dreams of love. The final movement, “Danse d’Arlequin,” opens with a snippet of “Valse amoureuse,” and then Harlequin jumps in, whirling about in a light, high-spirited dance. A more dreamlike transition follows with arpeggiation between the hands, leading to material from the first movement. Harlequin then returns in his dance, building to a frenzied climax. Columbine is reminded of her sweetheart with material from “Valse amoureuse” before Harlequin finishes the movement with a flourish of his dance.

After Her Husband’s Death

The second decade of the twentieth century was a pivotal time in Beach’s life: her husband of twenty-five years died in 1910 and her mother died soon after, in February 1911. Later that year Beach left for Europe, not returning until 1914. Several of her piano pieces were written in Europe. The Tyrolean Valse-Fantaisie, op. 116, was begun in the Tyrol in 1911 and completed in Munich in 1914.21 It was performed in Boston in December 1914 upon Beach’s return from Europe and was published much later, in 1926. This concert piece begins in descending unisons, the bare bones of the fantasy melody, which soon emerges pianissimo in the right hand. Beach explores this simple motif sequentially, using extended harmonies and chromatic decoration. This improvisatory section ushers in the first waltz melody, related to the opening fantasy melody in the descending minor third outlined by the upper notes. The second waltz melody is the folk song, “Kommt ein Vogel geflogen.” The two melodies are then combined, with the first waltz in the right hand and the second in the left. The third melody in this quasi-rondo form of waltz melodies is “Rosestock Holderblüh.”22 This tune is introduced on its own, then combined with “Kommt ein Vogel,” before the return of the first melody. After a pause, Beach writes a grandiose section of full chords and octaves, which leads to a passage around the opening fantasy figure. “Kommt ein Vogel” is heard once again, accompanied by trills this time, before the music returns to the expansive chordal melody for more development. The opening material reappears, now introducing the coda – a masterfully constructed tour de force that includes all the main waltz themes in a final dance frenzy.

Prelude and Fugue, op. 81, was begun in 1912 during Beach’s stay in Germany, performed in Boston in 1914, then published by Schirmer in 1918. The letters of Amy Beach’s name (A. BEACH) inspire the piece, referencing Liszt’s Fantasy and Fugue on B-A-C-H (1871), with four letters shared between Liszt’s theme and Beach’s (B flat, A, C and B natural [designated H in German]).23 Notably, Beach studied with Carl Baermann, a pupil of Liszt’s, in Boston from 1882 to 1885. In her work, Beach uses A-B-E-A-C-H both in opening the Prelude, written like a fantasy, and in the fugue subject. The prelude is sectional, and the theme is first presented in low octaves with sextuplet flourishes following in both hands. The theme is then set in full chords over sustained bass A octaves, marked fortissimo. This leads to a dolce cantabile section of development, first in arpeggiated figures, then in chromatic thirds, followed by more left-hand figuration accompanying the transposed theme in the right hand. A bombastic octave sequence follows, which builds to a climax followed by silence. Then beautiful ppp arpeggios in both hands usher in a quiet chordal reminiscence of the theme. Beach creates a very special moment, and in that mesmerizing stillness comes the fugue. In four voices, Beach presents the subject very simply with eighth-note accompaniment patterns. The tempo then becomes slightly faster, and a triplet underlying rhythm is introduced, with each voice again brought in in layers. The next section uses a sixteenth-note accompanying pattern with a lively countermelody, which is then developed. After a build-up using this material, Beach brings the whole piece down to ppp, with an octave ostinato pattern in the left hand (based on the countermelody) undergirding a choral development of the subject. This grows, and maestoso octaves of mounting fury lead to a grand statement of the theme in low octaves, the countermelody second subject in upper right-hand chords, and sixteenth-note octaves running between the two voices. Truly Lisztian in both technique and the way three hands are suggested but only two employed, Beach is in her finest compositional form writing the passagework that brings this work to culmination. It is an impressive concert work and one of her most important piano compositions.

Return to the United States

Having worked through her grief, traveled, and promoted her music through public performance, Beach came back to the US sure of herself and with newfound zeal for her work. Under management, she toured the country playing her chamber music, vocal pieces, piano solos, and the piano concerto. In 1916, Beach made her permanent base in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, the birthplace of her mother, living with her cousin and aunt. She had an article published in The Etude magazine later that year, detailing her perspective on piano performance and technique.24 In it she advocated for intuition in interpretation: “one’s technical equipment in any art should be sufficiently elastic to allow free adaptation in whatever direction our tasks lead us.” She encouraged developing the tools of the trade: “Of course, we must have technic, and plenty of it. In order to express our own thoughts, or adequately those of others, we must first acquire a sufficient command of language.” Beach was a natural pianist and was opposed to “hard and fast” rules in imposing particular techniques; indeed, the ultimate goal was to purvey musical meaning: “We must adapt the method used to each separate phrase, according to its musical and emotional significance.” It is worth keeping that in mind in approaching her pieces – that she herself would wish pianists to become intimately acquainted with the notes, finding their own way of bringing the music to life. “Each one [piece] has its own story to tell, and the technic must be suited to the telling. Here we come to the real value of technic: a means of expression.”

From Blackbird Hills, op. 83 (published 1922), subtitled “An Omaha Tribal Dance,” is another adroit piece based on folk material. The Omaha are a Native American tribe of the American Midwest. From Blackbird Hills is based on a children’s song, “Follow my leader.”25 It opens with the tune in duple meter, lively and quick, the melody first in the right hand and then in the left. This is followed by an Adagio that uses the same folk melody, but in an expanded rhythm with underlying harmonic development. The opening section returns but then falls into a sequential development that leads to a truncated return of the Adagio. A presto coda based on the opening of the piece brings From Blackbird Hills to a brilliant finish.

Fantasia fugata, op. 87 (published 1923), is a larger work, a concert fantasy based on the traditional prelude and fugue format. It opens with a flourish of octaves preceded by grace notes, a motive that later forms the basis of the fugue subject. Beach wrote that this gesture was inspired by Hamlet, “a large black Angora who had been placed on the keyboard with the hope that he might emulate Scarlatti’s cat and improvise a fugue theme.”26 The extended opening section uses the grace note motif to explore harmonic sequences with arpeggiation. This section acts as a “prelude” to the more extensive fugal section that follows. In three voices, the fugue begins with underlying eighth-note rhythms supporting the theme. The next section uses sixteenth notes to develop the material sequentially. This is followed by a second theme, a rising subject with a somewhat jazzy rhythm, also presented in three voices. The earlier sequential development of the first theme returns, moving through different harmonies, to lead to a grand final statement of the fugal theme in left-hand octaves, followed by the second subject in right-hand octaves. Fantasia fugata ends with a tremendous final cadence, a satisfying conclusion to a well-crafted concert piece.

Beach penned a piano transcription of “Caprice” from The Water-Sprites, op. 90 (1921), originally written for flute, cello, and piano. Just under a minute long, Beach’s transcription effectively amalgamates the three instrumental parts, with the right hand covering the running sixteenth figuration and some of the flute interspersions, and the left hand imitating the pizzicato cello line. The transcription is two bars longer than the original and deviates slightly toward the end, becoming in its own right a piece beautifully written for piano.27

The MacDowell Colony

In 1921, Beach began her long relationship with the MacDowell Colony, spending the summer composing at their retreat in Peterborough, New Hampshire. She found the quiet and closeness to nature inspiring and the contact with other artists, writers, and musicians at the Colony refreshing.

The Fair Hills of Éiré, O!, op. 91 (1922), takes as its melody the Irish American folk tune “Beautiful and Wide are the Green Fields of Erin,” which Beach was introduced to by Padraic Colum while at the MacDowell Colony in 1921.28 “Ban Chnuic Eireann O” begins: “Take a blessing from my heart to the land of my birth, And the fair hills of Eire, O!” Beach sets the melody first with a simple accompaniment, then she writes a quiet chordal triplet pattern for the right hand and lets the left take the melody. The piece becomes more virtuosic with thirty-second-note figuration introduced. The melody first comes in the middle voice, then in big chords with arpeggio sweeps in the left hand. A simple, evocative statement of the folk tune ends this lament for the homeland.

A Hermit Thrush at Eve, op. 92, no. 1, and A Hermit Thrush at Morn, op. 92, no. 2, were composed in 1921 at the MacDowell Colony. Beach writes in a footnote that the birdcalls “are exact notations of hermit thrush songs, in the original key but an octave lower,” heard at the MacDowell Colony. At the top of A Hermit Thrush at Eve are lines by John Vance Cheney:

The piece, in E-flat minor, begins in the depths of the piano and rises, with an undulating triplet pattern of great beauty emerging over an eighth-note accompaniment. The melody comes in, sweetly singing above the gentle movement, to create an atmosphere of utter tranquility, a prayerlike state suggested by the poem. The song of the thrush enters, freely notated in grace notes, floating on the dusk air. Beach brings the main tune back in, and then more thrush song, creating an absolutely gorgeous piece of music with profound depth. A Hermit Thrush at Morn quotes J. Clarke: “I heard from morn to morn a merry thrush sing hymns of rapture, while I drank the sound with joy.” In D minor, this piece is written as a slow waltz. The thrush song is evident from the start, being part of the melodic impetus. It is in quasi-rondo form, with the second and fourth sections being more dramatic and developmental, moving through extended harmonies.

From Grandmother’s Garden, op. 97, also written at the MacDowell Colony in 1921, is a suite of five pieces in which each movement represents a wildflower. The first, “Morning Glories,” has fast arpeggiation between the hands with the melody set in the first note of each left-hand group as it sweeps up. The ripples depict the flower by the same name, which is fleeting and short-lived: the blossom usually lasts just for the morning. “Heartsease” is quiet and beautiful, painting a picture of the flower also known as Viola tricolor. The soothing melody comes three times, first in the middle register, then an octave lower, and finally in the right hand over a beautifully written descending bass line. “Mignonette” is translated “little darling” and is a plant with tiny, fragrant flowers growing on tall spikes. Yellowish white in color, its Latin name is Reseda, “to calm,” and it was utilized by the Romans to treat bruises. Beach writes this exquisite little piece in the style of a minuet, apropos for its title, “Mignonette.” “Rosemary and Rue” are flowers that connote remembrance. A nostalgic movement, Beach sets a gentle chromatic melody over a simple left-hand chordal pattern to represent rosemary. Beach uses rue for her second theme, written as a sustained melody in the left hand with quiet eighth-note accompaniment in thirds. “Honeysuckle” is a fast waltz, à la Chopin’s Minute Waltz. Honeysuckle as a plant is a climber, with long tendrils that twine around anything handy. Beach twines the melody round and round, like the honeysuckle, in running right-hand patterns.

Two Pieces, op. 102, was published in 1924 and dedicated to Olga Samaroff (1880–1948). The first piece, “Farewell, Summer,” has at the top lines that read, “O last of the free-born wildflower nation! Thy bright hours gone and thy starry crest: Three names are thine, and they fit thy station, Frost Flower, Aster and Farewell Summer, But Farewell Summer suits thee best!” The title of the piece, therefore, has a double meaning: it is saying goodbye to the summer months as well as depicting the flower of the aster family called Farewell Summer. Beach writes the first section of the piece in the style of a gavotte, with a light, playful character. The middle section is more introspective and marked legatissimo, with the melody in the middle voice and an eighth-note accompaniment in both hands lulling the listener in a dreamlike manner, remembering the days of the summer. The second piece, “Dancing Leaves,” is exactly that, a cascade of leaves dancing in the autumnal breeze. Marking the tempo molto vivace, Beach uses chromaticism, a light accompaniment, and staccato patterns of parallel thirds and fourths to paint the picture perfectly.

One of the retreats at the MacDowell Colony, the Alexander Studio, provided inspiration for the Old Chapel by Moonlight, op. 106 (published 1924).29 Crafted in stone, with arched windows and doorway, the building sits in the wooded landscape, much as the simple chorale tune that comes in the middle of the piece sits among the elegant parallel seventh chords that form the opening and closing sections.

Amy Beach’s affinity with the piano as a performer comes through in her writing of Nocturne, op. 107 (1924).30 The piece opens on the dominant octave and takes four bars of progression using seventh, diminished, and augmented harmonies to arrive at E major. The melody is introduced in the middle voice with low bass notes tolling the first beat of the bar and supporting chords on the second half of each beat. Beach moves the melody between the voices, building to an appassionato climax of full chords in both hands, making this a very wakeful “night piece” indeed! The dreams or passions of the night having subsided, the piece ends quietly in slumber.

A Cradle Song of the Lonely Mother, op. 108 (published 1924), is, as the title suggests, a lullaby from a mother who is lonely, caring for her baby on her own. The rocking accompaniment undergirds the melody that Beach develops freely in the right hand. This undulating motion subsides, and the middle section of the piece emerges ppp. A lovely pattern of two notes in the left hand against three in the right supports the new melody in the middle voice. Trills usher in the return of the opening theme, which becomes fuller and more decorated. The melody of the middle section returns as the coda in this most atmospheric piece.

From Olden Times, op. 111, a gavotte for piano, is unfortunately lost. The title is included on two lists of works, in Beach’s own hand, as a manuscript and unpublished.31

By the Still Waters, op. 114 (1925), refers to Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters …” Beach was baptized into the Episcopal church in 1910 several months after her husband’s death. She wrote, “the greatest function of all creative work is to try to bring even a little of the eternal into the temporal life.”32 This piece is a tranquil portrayal of the still waters of Psalm 23 and the reassurance that comes later in the Psalm of one’s soul being restored, with no fear of evil, and goodness and mercy pervading the rest of life.33

Another Set of Pedagogic Pieces

In 1922, Beach and two local teachers started a Beach Club for children in Hillsborough, NH.34 She dedicated From Six to Twelve, op. 119, nos. 1–6 (1927), to “the Junior and Juvenile Beach Clubs of Hillsborough, N.H.”35 The pieces are character studies, with the titles indicative of the music that follows. The first and last, “Sliding on the Ice” and “Boy Scouts March,” are in rondo form, with lively patterns depicting children frolicking on the ice and marching jauntily in step respectively. “The First May Flowers” is a simple waltz in ABA form. “Canoeing” conveys the gliding of a boat through water with the melody in longer notes surrounded by the moving water of broken chords. “Secrets of the Attic,” in three-part form, has outer sections that whisper, “I have a secret …,” and a middle section that insists it will not divulge the secret no matter what! “A Camp-fire Ceremonial” is solemn, with a low A gong sounding under the still chordal melody of the first and last sections. The middle section of the piece is perhaps the rite itself, conducted in moonlight in a circle around the campfire.

The Second European Visit

Beach visited Europe once again in 1926–27, beginning in Italy and finishing with six weeks in Paris. Her writing of A Bit of Cairo (published 1928) was perhaps influenced by seeing the Egyptian treasures at the Louvre and also by the success of the Harvard University–Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition to Egypt in 1927. The piece alludes to Debussy’s Golliwogg’s Cake-walk in the main theme and stylized accompaniment, with the opening jaunty melody taken through a myriad of keys.36

Three Pianoforte Pieces, op. 128, and Out of the Depths, op. 130, were both written at the MacDowell Colony in June 1928. The Three Pianoforte Pieces (published 1932) are dedicated to Marian MacDowell, wife of composer Edward MacDowell and good friend of Amy Beach. The pieces are reminiscent of the woods in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where the MacDowell Colony is located. Beach herself performed the pieces for Eleanor Roosevelt at a White House concert in 1936. The first, “Scherzino: A Peterboro Chipmunk,” is a character piece with an energetic chipmunk scampering to and fro, up and down, in and out of the trees. The second, “Young Birches,” impressionistic, with parallel fourths and extended harmonies, paints a picture of the breeze caressing the leaves of the birches, shimmering and calm. “A Humming Bird” finishes the set, with Beach using fast notes between the hands to capture the little bird flitting from flower to flower, collecting nectar in a blaze of color.

Out of the Depths, op. 130 (published 1932), carries the subtitle “Psalm 130,” which begins, “Out of the depths I have cried unto thee, O Lord. Lord, hear my voice: let thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications.”37 The beginning of this piano piece evokes the hopelessness and cry for help that open Psalm 130. The development of this melody perhaps portrays verse five, “I wait for the Lord, my soul doth wait, and in His word do I hope.” Beach builds to a climax of petition, with a flurry of notes adding weight to the plea for help. The piece ends quietly, in full submission to a greater will beyond human understanding.

Later Solo Works

A September Forest was most likely composed in 1930 during a stay at the MacDowell Colony.38 The rising theme of the opening bars paints the picture of a quiet, beautiful woodland haven. The serenity and inner peace she must have felt at her retreat are revealed in the hymn-like melody that comes halfway through the piece. This melody builds to a ff climax of grandeur with full chords and resonating bass octaves. It then winds down to a simple restatement of the opening woodland theme. Beach used A September Forest as the basis for Christ in the Universe, op. 132, a vocal work with orchestra.

The Lotos Isles (c. 1930) is based on Beach’s song of the same title for soprano and piano published in 1914 as Op. 76, No. 2.39 The text for the song is from Alfred Tennyson’s “The Lotos-Eaters.” Beach writes an additional introduction and coda for her piano piece and only obliquely refers to the melody of the song. The piano piece uses the accompaniment pattern from the song, but here it is developed as melodic material. Also, the piano piece is in ¾ time, while the song is in 4/4. So, while there are strong similarities, the piano piece stands on its own as a work and is not a transcription of the vocal piece.

Beach arranged Far Awa’, the fourth of her Five Burns Songs, op. 43, for piano in 1936.40 The song text is from Robert Burns’ poem of 1788, “Talk of Him That’s Far Awa’,” and is about a woman longing for her sailor lover. In the piano version, Beach first states the vocal melody in the middle voice, with right-hand chords on the offbeat in syncopated accompaniment. The same melancholic tune is then presented in the top voice and developed sequentially with full chords that build to a climax. The loneliness of the woman left behind is captured beautifully, with the piece ending in quiet resignation after her plea for rest: “Gentle night, do thou befriend me, Downy sleep, the curtain draw; Spirits kind, again attend me, Talk of him that’s far awa!”

The Improvisations, op. 148 (1937, published 1938), were composed by Amy Beach at the MacDowell Colony, writing to a friend that they were “really improvised” and that each “seemed to come from a different source.” The first, in ternary form, atmospherically explores augmented and diminished harmonies, the phrases sequentially moving forward yet seemingly suspended in time. About the second improvisation Beach said she was remembering how she “many years ago sat with friends in an out-door garden outside Vienna and heard Strauss waltzes played.”41 The third is marked Allegro con delicatezza and consists of a playful melodic pattern over a light chordal accompaniment featuring extended harmonies with quartal implications. This is followed by a very slow piece of three long phrases, each beginning the same but then diverging in their quest, a pure G-flat major resolution being found only at the end. The last improvisation is a sort of kujawiak, a slow mazurka, with the emphasis in this piece being primarily on the second beat of the bar. The grandeur of the opening develops with broad chords and full use of the range of the piano, the fff climax subsiding into a pp restatement of the opening.

Music for Piano Duet

Allegro appassionata, Moderato, and Allegro con fuoco are three pieces Beach wrote for piano duet as a teenager.42 With youthful exuberance, the theme from Allegro appassionata is later developed by Beach in her solo piece, “In Autumn,” op. 15, no. 1. The second piece, Moderato, is marked “cantabile” and is beautifully introspective, evidencing Beach’s early skill in harmonic nuance as she begins in D-flat major and deftly moves to G major before returning to the tonic. Allegro con fuoco is in 6/8, with a continual eighth-note pattern in the left hand undergirding a lyrical melody in the right.

Beach arranged Largo, the second movement of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1, for piano duet as a gift to her husband on their second wedding anniversary, December 2, 1887.43

Summer Dreams, op. 47 (1901), is a set of six character pieces for piano duet. “The Brownies” refers to a girls’ club of that name; “Robin Redbreast” “reproduces exactly the song of a robin”; “Twilight,” marked largo religioso, is preceded by a poem by Beach’s husband; “Katy-dids” is a light imitation of jumping grasshoppers; “Elfin Tarantelle” is a lively dance of the fairies in 6/8; and lastly “Good Night,” a quiet closing piece.

Music for More Than One Piano

Variations on Balkan Themes, op. 60, for two pianos, as referenced earlier, was arranged in 1937 using the 1936 version and including two extra variations. Published in 1942, it is in two halves: both parts start with the theme and then are followed by a set of variations each.44

The score to Iverniana for two pianos, op. 70 (1910), is unfortunately lost, but there is evidence that it was later rewritten as Beach’s Suite for Two Pianos Founded upon Old Irish Melodies, op. 104 (1924). This is a large-scale work in four movements. The first, “Prelude,” is marked Lento quasi una fantasia. Exploratory in nature, there is beautiful interplay between the pianos with advanced technique required. “Old-time Peasant-dance” follows, an Allegro con spirito where the dance melody is presented in Piano II, with Piano I then entering with a second, more lyrical Irish melody. The third movement, “The Ancient Cabin,” with trills, arpeggiations, scales, and octaves, is an expansive fantasy around its Irish folk melody. The concluding movement, “Finale,” is a demanding piece, with the theme alluded to in introductory material, then set between the pianos in fugal fashion and effectively developed with compositional aplomb.45

Organ

The organ was used to accompany many of Amy Beach’s choral compositions, but there is very little for solo organ. Beach wrote an organ version of Far Awa’ in 1936, in the afternoon of the same day she wrote her piano arrangement (discussed earlier).46 The organ version is very similar to the piano, though Beach here uses sustained pedal tones to underlay harmonic structures, and the left-hand accompaniment from bar 31 is more pressing, with continued emphasis on the offbeat.

Prelude on an Old Folk Tune (“The Fair Hills of Éiré, O!”) (1942, published 1943) was based on the same Irish folk melody as her earlier piano piece, op. 91.47 However, the organ work is a completely new setting of this melody, with expansive harmonies and much chromaticism in the accompaniment.48

Summary

Beach wrote, “I never remember when I didn’t compose. … Family anecdotes have it that I began at the age of four.”49 Music was a first language to Beach, and this innate ability to communicate musically comes throughout her entire oeuvre, from Mamma’s Waltz to the Improvisations, op. 148. She heard music in her head; melodies naturally came to her and were not contrived. Beach’s harmonic language developed from the simple progressions in her early keyboard work, through a broader romantic harmonic base, and then into more expressionistic tonalities. Her piano writing grew from basic Alberti bass patterns and chordal accompaniments to pieces requiring advanced piano technique and bravura performance. Throughout, Beach’s love of melody shone through with long lines and overarching shape, making her music captivating, appealing, and listenable.

The keyboard works range from small character pieces to the large Balkan Variations, but what there isn’t per se is a sonata, set of etudes, or series of preludes. Beach was a Romantic at heart and reveled in creating pictures with her music, using themes from nature, folk traditions, and the world around her to produce masterpieces. Her particular skill in shaping and developing melodies with rich harmonic language enabled Beach to paint snapshots of life as she experienced it, whether in the woods of New Hampshire or in the Tyrol, Austria. Beach’s contribution to the keyboard literature is immense and should be celebrated for the wonderful treasure chest of piano gems that are a pleasure to hear and play.

Beach had her own keyboard voice – she was not trying to mimic the masters but brought to life music of her own making. She certainly was inspired by traditional forms such as waltzes, gavottes and minuets, and paid homage to the mainstay piano repertoire in contributing, for example, a beautiful Barcarolle, op. 28, no. 1, a passionate Ballade, op. 6, and an extraordinary Prelude and Fugue, op. 81. While similar to Liszt in being a composer/pianist, akin to Schumann in her character pieces, with technical writing versed in Chopin and expansive harmonies influenced by Brahms, Beach breathed into life music essentially her own, the synthesis of natural ability, schooled pianism, study of the masters, and disciplined dedication. Her wonderful keyboard music is testament to her greatness.

Songs were the foundation of Amy Beach’s musical world. Her mother reported that by the age of one, she could hum forty songs. By age two, she could sing harmony to any tune her mother sang. She insisted that her mother and maternal grandmother sing daily – but only songs she liked. Harmonizing with her mother’s singing was a bedtime ritual. This love of singing led to mental composition of melodies, later harmonized during her first experiences playing the piano. It was natural that she felt all music-making was “singing,” be it vocal or instrumental. Appropriately, her first publication was a song, and songwriting led to her initial fame as a composer. For decades after her death, she was best remembered for her songs. They are well crafted, most with singable melodies and integrated piano accompaniments, satisfying to both musicians and audiences.

Songs predominate her total compositional output. She composed them prolifically, even during the years she was occupied primarily with writing larger compositions. Between 1887 and 1915, several songs were published each year, almost all shortly after their composition. Performances by some of the United States’ most prominent musicians furthered the songs’ remarkable popularity and contributed to their quickly becoming standard concert, recital, and teaching repertoire. She and her primary publisher, Arthur P. Schmidt, worked diligently to promote the songs and ensure they stayed in print. Despite their popularity during her lifetime, they fell into neglect when ill health precluded her extensive travels and performances around the United States to promote them.

In the 1970s, despite a resurgence of interest in women composers, only two of her songs were available in print.1 Renewed interest in her oeuvre focused primarily on her importance as the first successful American woman composer to create large-scale orchestral, choral, and piano works, leading to a revival of performances of her major works. Largely because it was not unusual for women of her day to compose in smaller forms, her songs remained in obscurity a bit longer. Only after several were reprinted in the mid-1980s did they begin to reclaim their well-deserved attention. As of this writing, almost all of her published songs in the public domain are available through www.imslp.org, and many songs have been republished in scholarly editions. Numerous autographs used by publishers to prepare printed editions are housed in the Library of Congress’s A. P. Schmidt Collection (www.loc.gov/collections/a-p-schmidt-collection/).

Stylistic Characteristics

From 1880 to 1941, Beach composed 121 art songs with keyboard accompaniment, of which 111 were published during her lifetime. They demonstrate her exceptionally insightful understanding of texts, mastery of the form, and awareness of trends in current European musical styles. The assumption that Beach’s songs are overly Romantic in nature, unnecessarily elaborate, and excessively sentimental has sometimes led to their cursory dismissal as being mere parlor songs. While those descriptions might be appropriate for many songs by her female contemporaries, Beach’s songs were composed as art songs. Even though the vocal lines and accompaniments of some of her songs are complex and technically demanding, they were intended to be sung and played by both amateur and professional musicians.

She believed that the mission of all art is to uplift: “to try to bring even a little of the eternal into the temporal life.”2 She strove for musical expression people would understand, believing that songs should be inspired, creative, musical responses to texts – incorporation of both intellect and emotion.

Even though some critics have accused her of imitating other composers, or of composing in the style to which she had been most recently exposed, very few songs bear resemblances to those of her peers, a fact recognized early in her career. In a 1904 article on Beach’s songs, critic Berenice Thompson wrote,

She is not a poet dreamer, nor are her instincts those of the morbid or fastidious impressionist. Her artistic personality is entirely distinct from the schools of the day. She is neither a disciple of Richard Strauss, nor an exponent of the peculiar theories of d’Indy, Debussy, and the other Frenchmen. Nor are her ideas affiliated with the decadence which programmatic music and the mixture of arts is bringing upon the music of the century.3

Any similarities between her songs and those of other composers are more a reflection of her manifold interests and experiences than of plagiarism. Several poem settings actually predate those of her contemporaries.

Other critics have implied that her songs are all more or less alike. Closer examination reveals that, while many songs share similarities in structure, sentiment, and methods of text setting, all are quite distinctive. A hallmark of her music is extensive use of chromaticism, rooted in the ideals of German Romanticism. The application of this chromaticism was increasingly implemented within the context of more modern musical idioms, including impressionism and quasi-atonalism.

Song composition played a major role in the development of her unique musical language, providing her with opportunities for small-scale experimentation incorporating a wide variety of musical influences. Their use within this small form was subtle and controlled in comparison with more obvious inclusion of increasingly modern musical influences in her larger works. Several quotations from her writings will provide a basis for understanding her goals in song composition.

“Music should be the poem translated into tone, with due care for every emotional detail.”4

From earliest childhood, poetry was the foundation of Beach’s songs. Well before she could read or write music, children’s poems inspired spontaneous creation of accompanied songs. Memorizing texts came easily, as by age four, she was able to recite many long, difficult poems. This remarkable memory served her in good stead later in her method of songwriting: “In vocal music, the initial impulse grows out of the poem to be set; it is the poem which gives the song its shape, its mood, its rhythm, its very being. Sacred music requires an even deeper emotional impulse.”5

“I believe that a composer, like anyone else, is influenced by what he studies and reads, because literature cannot fail to react upon artistic expression in any other form.”6

Avid reading and continuing social contact with some of the United States’ most esteemed writers refined her literary discernment. An eclectic taste in poetry is apparent in the wide range of authors whose texts she set. Her husband may have suggested settings of poems by historically significant authors, including Shakespeare and Burns, but the majority of the songs were settings of works by living authors, many of whom were friends. More than one-third of the texts were by female writers.

French and German poetry from anthologies, newspapers, and popular magazines inspired eleven German and seven French songs. These texts provided a means for experimentation with inclusion of elements of current trends in the styles of German Lied and French chanson, as well as an opportunity to hone her skills in text settings in those languages.

Much poetry of her early songs appealed to Victorian ideals and may seem dated today. She was drawn to poems about love and nature. Love song texts in the first person were most commonly from a female perspective. Other favorite topics were times of day (most frequently twilight or night), flowers, and birds. Several songs quote or are based on birdcalls, including “The Blackbird,” op. 11, no. 3 (1889); “The Thrush,” op. 14, no. 4 (1890); and “Meadowlarks,” op. 78, no. 1 (1917).

“In vocal writing, the initial impulse grows out of the poem to be set; it is the poem which gives the song its shape, its mood, its rhythm, its very being.”7

Beach fervently believed that in order to interpret a song effectively, a singer must fully understand a poem’s meaning and character. To this end, she preferred that a song’s text be printed on the page before the musical score, as she shared with her publisher in a 1908 letter: “A singer can get at a glance a better idea of the character of a song by this means than by a prolonged study of words scattered thro’ [sic] several pages of music.”8 She expanded on her views of the importance of the text to interpretation in a 1916 article:

Each song is a complete drama, be it ever so small or light in character, and no two are interpreted in the same way. Even the quality of the voice may change absolutely in order to bring out some salient characteristic of the composition. Technical perfection may indeed be there, but so completely subordinated to the emotional character of the song that we lose all consciousness of its existence.9

“A composer must give himself time to live with what he is creating.”10 “It may happen that, for instance, that one has a ‘perfect’ theme for a song. … It is quite possible that the melodic line may not seem at all suitable for the voice … the original theme may develop into something quite different from the song that was first planned.”11

Songwriting was recreation for Beach. When she felt a roadblock while working on a larger piece, she sometimes wrote a song, viewing it as a special treat: “It has happened to me more than once that a composition comes to me, ready-made as it were, between the demands of other work.”12 Her songs may have seemed to flow quickly and spontaneously from her pen, yet they often evolved unconsciously over a longer period of time, although this was not always the case.

“In writing a song, the composer considers the voice as an instrument, and that the song shall be singable should be the fundamental principle underlying its creation. Many an otherwise magnificent work lies on the shelf, unused, because it is not suitable for the voice.”13

What makes most of Beach’s songs so singable? Why do they practically sing themselves? The answer is most likely her remarkable sensitivity to languages’ natural inflections, even though this may not be consciously perceived by the musician or listener. Her songwriting process began by careful contemplation of the poem to be set. After memorization, mental repetition of the words’ spoken inflection led to the melody, phrase by phrase. The result: melodies that are musical representations of the text’s natural inflections, as if the pitches of the spoken word were given musical notes (Example 6.1). Division of poetic lines into two- or three-measure phrases enhances the songs’ singability as well.

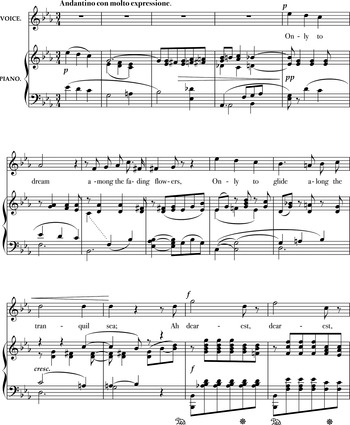

Example 6.1 “Ecstasy,” op. 19, no. 2, mm. 1–14.

It is worthwhile to consider the voice types Beach had in mind for each song. This can frequently be determined by a song’s dedication. Most early songs were composed for light, high, female voices. Later in life, she favored large, dramatic female voices.

About 60 percent of the songs, most of which were for high voice, were published in only one key (much to the chagrin of those with lower voices). Because her musical response to poetry emerged in specific tonalities, with their associated timbres in both piano and vocal parts, it is preferable to sing them in their original keys. Even so, modern performers and audiences are not able to experience the exact, original, intended sonorities of the early songs, as pianos in Boston were tuned slightly lower in the late nineteenth century than they are today.

Most of her songs are in major keys, with F major, A-flat major, and E-flat major predominating. She perceived the latter two of these as blue and pink, respectively. Three lullabies composed for friends’ newborn babies made use of these color associations, with blue for male and pink for female. Curiously, given her childhood aversion to music in minor keys, thirty-three of her songs represent ten different minor modes. With very few exceptions, songs in minor modes end with (sometimes quite abrupt) major cadences.

She was highly opposed to unauthorized transpositions of her songs, as her timbral intent would be obliterated. In order to fulfill and/or increase their demand, Schmidt requested transpositions of several songs (beginning with “Ecstasy” in 1893). Alternate keys were usually lowered by a minor third. Popularity of “Ah, Love, but a Day!” and “Shena Van” warranted three transpositions. Songs with expansive ranges and high tessiture not lending themselves to acceptable transpositions were published in one key, with alternate pitches for highest and/or lowest notes.

“A composer who has something to say must say it in a fashion that people will listen to, or his works will lie in obscurity on dusty shelves.”14

Beach understood the publishing industry was purely a business matter, regulated by supply and demand. As her compositional career blossomed, she and Schmidt employed a variety of strategies to create broader demand for her music. Marketing efforts focused on songs and short piano pieces, music that would please the amateur musician and be performed frequently because of its accessibility. To appeal to this demographic, songs in foreign languages were published with English titles and singing translations printed above the original language, a common practice at the time.

Schmidt published notices and advertisements in newspapers and magazines. He also distributed his own promotional pamphlets containing effusive (sometimes misrepresentative) descriptions of Beach’s songwriting prowess. He took advantage of publicity garnered by performances of her larger works by coordinating publication of her newest songs with those events. Their inclusion on subsequent high-profile concerts furthered sales. To satisfy and increase demand, arrangements of her biggest sellers were published with violin obbligati and for various combinations of voices.15 “A Song of Liberty,” op. 49, and “The Year’s at the Spring,” op. 44, no. 1, were issued in Braille (in 1922 and 1931, respectively).

Magazines offered another effective means for promoting songs. Several were composed expressly for them, usually published with an accompanying biography and/or interview. These songs are short, with simple melodies within limited ranges and easy accompaniments.

When programming Beach’s songs, one should be aware that most of her early songs were composed as individual entities, with highly varying topics, usually unrelated. As soon as she had produced three to five songs, Schmidt published them in an opus, deciding on the order of the songs within the opus.

In 1891, after publishing eighteen of her songs, Schmidt assembled fourteen, issuing them as part of a series of song anthologies. All were subtitled “a Cyclus of Songs,” even though none of them contained song cycles. Schmidt likely hoped these publications would increase profits, as customers wanting to purchase one or two songs might be likely to pay a little more to buy a collection that included songs that had not sold well singly. After publishing another thirty-nine songs, a second anthology of fourteen songs (also part of the “Cyclus” series) was issued in 1906. Plans for a third anthology in the 1930s never came to fruition due to high costs of printing during the Depression.

It is often misconstrued that since several of Beach’s better-known songs are slow, they all share that trait. Actually, an equal number of fast and slow tempi are represented in her song output. All tempo designations are in Italian, most with added directives for their interpretation, commonly including the adverbs espressivo or espressione; tranquillo or tranquillamente.

Early songs exhibit somewhat of a formula for setting up a melody’s climactic note, usually at or near a piece’s end: an ascending vocal line leading to the highest tone is interrupted by descending movement, either stepwise or a skip, that precedes an ascending leap of at least a minor third to the high note. A song’s highest (and either loudest or softest) tone is usually set on an open vowel ([a] or [ɔ], for example), sustained for one or two measures. She certainly sensed that these open vowels are the most conducive for optimum vocal resonance in singers’ higher ranges. Frequently, though, the tone preceding the highest one is also on an open vowel. As these ascending intervals straddle singers’ upper passaggi, it is more challenging to maintain forward placement than if the high note were preceded by a closed vowel (such as [e] or [i]). These highest tones and their accompanying chords were usually assigned sudden, extreme dynamic changes, sometimes pianissimo, but more often a jolting forte or fortissimo. Musicians should consider that these sustained tones were intended to have as much “life” as the preceding material, not beginning and maintaining the same dynamic from outset to completion. For effective interpretation, to give the music shape and carry expressive movement forward, pianissimo notes should begin as a slightly louder dynamic level than specified, making a decrescendo to the level indicated. As it can be strenuous for the singer to sing and sustain a loud tone “going nowhere” expressively for several measures, as well as unsettling to the listener to be bombarded by such an abrupt, loud dynamic change, the loudest notes should begin more softly than designated, making a crescendo to the indicated fortissimo.

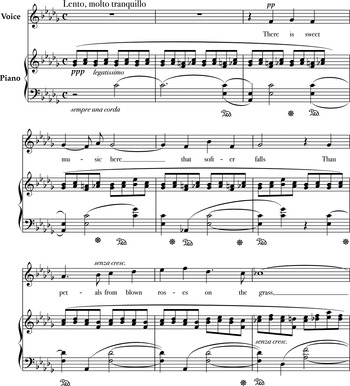

Facility at the piano likely contributed to her technically challenging accompaniments. Continual use of octaves and complex chords with quite differing distributions of notes in quick succession requires long fingers and comfortable hand spans of more than an octave. Accompaniments rarely double vocal melodies. Occasionally during measures of rest between vocal phrases in earlier songs, what promises to be an effective countermelody emerges, only to disappear at the voice’s reentrance. Her preference for triple and compound meters (especially 6/8) facilitated the incorporation of repeated eighth note or triplet chords/figures to increase intensity and forward motion, a device also found in her solo piano works (Example 6.2). While used to great effect in several songs, its implementation for measures (or pages) at a time resulted in their monotonous similarities.16 Endings of three chords or with ascending arpeggiated flourishes (often in sixths) became somewhat cliché (Example 6.3).

Example 6.2 “After,” op. 68, mm. 71–78.

Example 6.3 “Forget-me-not,” op. 35, no. 4, mm. 55–59.

Clearcut variations in Beach’s songs delineate three distinct compositional style periods. These correspond with three important periods of her life. The first style period begins with her first published work in 1883, “The Rainy Day” (composed 1880), and ends with the deaths of her husband and mother in 1910 and 1911, respectively. Songs composed in 1914 in Europe comprise a second style period. A third style period begins in 1916 and continues through 1941.

First Style Period (1883–1911)

As a girl, and later as the wife of a socially connected, wealthy Boston surgeon, Beach had extensive time to devote to piano practice and composing, making this her most productive period of song composition. She composed seventy-two songs during these thirty years, many of which became her best known. Notably, “The Rainy Day,” her first published song, begins with a direct quotation of the first eight notes of the third movement of Beethoven’s “Pathétique” Sonata, op. 13, transposed from C minor to F minor.

After marrying in 1885, her program of autodidactic musical study was supplemented inestimably by her husband’s careful guidance. An amateur singer and accomplished pianist, Dr. Beach had extensive knowledge and appreciation of art song literature. He shared his expertise with Amy, introducing her to masterworks of song. This deepened her understanding of basic structural elements, including forms, text settings, sensitively crafted accompaniments, modulations, shaping of phrases, and appropriate ranges and tessiture.

Dr. Beach was also an amateur poet. Amy set seven of his poems, all composed within his lifetime and dedicated “To H,” with authorship attributed to H. H. A. B. The first of these settings were the three op. 2 songs. They were certainly composed for him, as relatively low and limited ranges would have suited his baritone voice. She composed settings of his poems on his birthday (December 18), presumably as birthday presents. Manuscripts dated December 25 suggest that, after being given poems for Christmas, she made settings immediately.

It should be taken into account that late nineteenth-century pianos were usually tuned slightly lower than modern ones. The prevailing pitch standard in Boston from at least 1863 to 1900 was A = 435.17 A = 440 was not officially adopted as the universal pitch standard until the International Standardizing Organization (ISO) meeting in London in May 1939.18 As a result, many songs composed for medium voice may be deceptively difficult for today’s amateur singers, as their highest notes fall slightly in voices’ upper passaggi.

From the outset, strophic, modified strophic, and ternary forms predominated Amy Beach’s song output. All but a handful follow this uniform pattern: minimally varied melodic material for repetitions of A sections are supported by accompaniments’ substantially different harmonies. Most early songs are marked by expansive, flowing melodies and accompaniments that reflect the influence of contemporary European compositional styles.

Interspersed are several songs described as enjoyable, “if not fully apprehended at first hearing.”19 This type of song begins with four to eight measures of a memorable melody that subsequently evolves into a seemingly jagged chain of notes. This is caused by vocal parts’ frequent extraction from (or burial within) their accompaniments’ relentlessly changing harmonies. The voice sometimes provides counterpoint for the accompaniment or serves as an inner part to complete a complex chord. Rapidly changing harmonies rarely lead to predictable vocal entrances after measures of rests.20 Several songs’ introductions contain descriptive figures that are repeated between vocal phrases, yet the vocal lines that follow are disjunct and bear no correlation with an accompaniment’s motive. Her usual sensitivity to natural speech inflection is absent in these songs.21 These rambling, pianistic songs that lack perceptible melodies show no apparent compositional models. They bring into question her later statement that she always composed away from the piano.22

Vacillation between (often remote) tonalities necessitated the persistent use of accidentals (including frequent double sharps/flats) and enharmonic spellings (alternating between correct and incorrect spellings), making them difficult for an accompanist to read. Critic Rupert Hughes even described one of her more accessible songs as “bizarre.”23

Prominent nineteenth-century American and European song composers generally employed evident melodies and sparse accompaniments with slow harmonic movement within conventional chord progressions. She hit her stride around 1894, composing increasingly marketable songs containing the streamlined accompaniments and flowing melodies for which she is best known.

The 1890s were her most productive years of songwriting, with publication of thirty-seven songs during the decade. Her first big seller was a modified strophic setting of her own two-verse poem, “Ecstasy” (1893). Its moderate range and simple, memorable melody in two-measure phrases (helpful for amateurs with limited breath control) made it appealing to the average musician. Its popularity prompted the first publication in an alternate key. The poem was included in The Poetry Digest: Annual Anthology of Verse for 1939 (New York: The Poetry Digest, 1939). As most of the subsequent songs of this period are in this accessible style, the success of “Ecstasy” may have given her better insight into the type of song that might please the general public.

In his 1893 Harper’s Magazine article, Antonín Dvořák proposed that in order to create a truly American art form, composers should incorporate “plantation melodies” and minstrel show music. The article prompted Beach’s immediate Boston Herald rebuttal: the opposing idea that American composers should look to their own heritages for inspiration.24 There is no evidence that they met personally during his 1892–95 stay in the United States, but she was clearly aware of his views and had thought deeply about them. Whether coincidental or not, it was around this time that Beach began inclusion of musical ideas reminiscent of traditional folk music of the British Isles, as evidenced by the stark contrast between her op. 12 (1887) and op. 43 (1899) settings of Robert Burns’ poems. The 1887 songs number among the long, rambling, piano-heavy songs of her youth. In stark contrast, with inclusion of dotted rhythms and “Scotch snaps,” the 1899 settings could be mistaken for folk songs. These songs appealed to the market: strophic with short, easily remembered melodies and simple accompaniments. The most popular of these, “Far Awa’!,” was later published in six arrangements for various groupings of singers and instruments between 1918 and 1936.

Following the 1899 Burns songs’ success, Beach employed the same formula for the highly successful “Shena Van,” op. 56, no. 4 (1904), a setting of William Black’s poem from his 1883 romance novel, Yolande. The melody’s pentatonic melisma contributes to the song’s folklike qualities, while a simple chordal accompaniment mimics a bagpipe with an open fifth drone. Similarities with Edvard Grieg’s “Solveig’s Song” suggest it might have been the model for “Shena Van.”

Among the handful of Beach’s most popular and enduring songs are the Three Browning Songs, op. 44 (1900), composed and dedicated to the Browning Society of Boston. Their high tessiture and manner in which vocal lines approach climactic high notes contribute to these being the most vocally demanding of her songs. “The Year’s at the Spring” and “Ah, Love, but a Day!” are the best known and most frequently performed of the three. In 1932, “Ah, Love, but a Day!” was reportedly the popular choice in a nationwide survey of the most standard American songs.25

By far the most popular of her songs, “The Year’s at the Spring,” was a staple of recital repertoire throughout the first half of the twentieth century. She later recalled: “It was composed while travelling by train between New York and Boston. I did nothing whatever in a conscious way. I simply sat still in the train, thinking of Browning’s poem and allowing it and the rhythm of the wheels to take possession of me.”26 She also recalled, “I had no writing materials with me, and so I went over and over it in my mind – learned my own composition by heart, so to speak, and as soon as I got to New York, wrote it down in twenty minutes. That, practically unchanged, was the song I gave them.”27

Robert Browning’s son was intensely moved upon hearing it, saying it could hardly be called a “setting:” the music and words seemed to form one entity; that one could not imagine anything more perfectly “married” than her music to his father’s words.28 Audiences’ enthusiastic responses to it (and a length of less than a minute) often prompted singers to repeat it several times. Interestingly, it holds the distinction of being the first song transmitted over the telephone.29

Although published as no. 1 of op. 44, “The Year’s at the Spring” is most effective at the end of the group when all three songs are performed together as a set. Its exuberance and animated tempo create a dramatic contrast with the two other songs’ slower tempi, bringing the set to a jubilant end. This reordering (2, 3, 1) also preserves the intended harmonic progression.

Only in her first style period did Beach set French texts, with varying degrees of success. Of these seven, “Jeune fille et jeune fleur,” op. 1, no. 3, and “Chanson d’amour,” op. 21, no. 2, are more varied versions of the rambling, fast harmonic rhythm songs, as they contain occasional measures with slower harmonic rhythms supporting “melodies.” These melodies appear as opening statements of verses or as short refrains. The four most appealing French songs show influences of the café chantant style of Charles Gounod and Eva dell’Acqua: “Le Secret,” op. 14, no. 2 (1891); “Elle et moi,” op. 21, no. 3 (1893); “Canzonetta,” op. 48, no. 4 (1902); and “Je demande á l’Oiseau,” op. 51, no. 4 (1903). Melodies reflecting the texts’ inflection are absent in these songs, perhaps a result of her unfamiliarity with the language.

In contrast, the melodies of her eleven German songs are excellent examples of melodies mirroring their texts’ spoken inflections. Both lighthearted songs and those with long, flowing melodies are among their number. They show her awareness of the most recent German song compositions, especially those of Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss. Her admiration for Strauss’ song “Ständchen” inspired her to compose a piano transcription in 1902. Around the same time, she produced the masterpiece, “Juni,” op. 51, no. 3. Given her recent preoccupation with Strauss’ song, one might expect to find similarities between their melodies (Examples 6.4 and 6.5).

Example 6.4 Richard Strauss, “Ständchen,” op. 17, no. 2, mm. 10–12.

Example 6.5 Beach, “Juni,” op. 51, no. 3, mm. 7–8.

The text’s sole topic of blooming spring flowers is perfectly expressed through the melding of melody and accompaniment, which become increasingly effusive throughout the piece, ending with a burst of joy. Overutilized in some songs to the extent of being a trademark, implementation of repeated triplets in “Juni” is the precise element needed to heighten the song’s intensity to its final chord.

Second Style Period (1914)

During most of her time in Europe from 1911 to 1914, a busy travel and performance schedule precluded time for composition. This lull was broken in 1914, her most prolific year of song composition. The ten songs composed in Munich in May–June (opuses 72–73 and 75–76) comprise her second style period.