INTRODUCTION

It was early April 2018, the end of the rainy season was finally approaching, and I was sitting in a wicker chair on a shaded veranda in Lilongwe. Opposite me sat a female Senior Chief telling a detailed story. Several years previously she worked for months with chiefs, religious officials, NGOs, district government officials and local police to formulate and enact a comprehensive set of new bylaws – which included detailed laws prohibiting child marriage. Roughly five months after the bylaws were enacted, religious officials informed the Senior Chief that six of her village headmen (VHs) were trying to bribe them with money and goats to perform underage marriages.

Feeling frustrated, and determined to make an example of these VHs, the Senior Chief formulated a plan to invite all her chiefs to attend the monthly Area Development Committee (ADC) meeting, to include the six errant VHs. At the end of the meeting, she called all six to stand before her. Then she called forward one of the pastors who had informed on them. ‘These chiefs tried to bribe me and force me to do a child marriage, but I said no!’ he cried out to the room. The Senior Chief turned to the six VHs and said, ‘Recite the last bylaw’.

To paraphrase, the last bylaw states that if any parent goes to the chief and requests permission to hold a marriage, the chief must verify the age of the prospective bride and groom. The Senior Chief narrowed her eyes accusingly at her chiefs: ‘What is the last line of that bylaw?’ The chiefs shuffled from foot to foot, nervous. They knew what was about to happen because they knew that the last line of the bylaw states that if any chief is found to have allowed a child marriage, they must be removed immediately. In front of all those assembled, the Senior Chief declared: ‘You chiefs, from today, you are dismissed until you obey my laws.’

It took the VHs nearly six months to track all the families down, terminate the marriages, and guarantee that the girls were sent back to school. Then they went to the house of the Senior Chief to formally apologise and beg to be reinstated. Before reinstating the VHs, the Senior Chief called the headmaster of each school to check on the status of every child. Only when she was satisfied that all the marriages were indeed broken and all the children returned to school, could the VHs resume their duties (Senior Chief 2017 Int.).

This is a useful vignette because it highlights several important observations. First, the Senior Chief made it clear that the passing of the bylaws was a community-based effort. These laws are clear, with an outline of steps citizens can follow to ensure all marriages are legal. Second, there was enough buy-in from the community that the pastors felt compelled to inform on the chiefs. A third observation is the importance of training. Under this Senior Chief, all chiefs have received training on the contents of the bylaws. A fourth observation is her deft use of punishment. She knew that making an example of just these six VHs would be enough to prove to all other chiefs that she was serious: the bylaws must be followed and there are swift and harsh consequences for breaking the laws. One final observation is the importance of follow-through. The Senior Chief refused to take the VHs at their word that the children had been returned to school.

This article has two aims. First, I outline existing literature to argue that reforms like those on child marriage occur on two levels: the political level and the cultural level. For political reform to have any efficacy when it comes to culturally embedded practices such as child marriage, cultural reform must also be addressed. To this end, chiefs – who are invested with both political and cultural authority – have the potential to be important champions of ending child marriage. Across the continent, the power of chiefs to address cultural reform is rooted in their positioning within society, their knowledge of current cultural practices and norms, and the respect they enjoy from the people as legitimate political authorities (Muriaas Reference Muriaas2009; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Kern and Kromrey2016). Furthermore, chiefs have a national network with a rigid hierarchy that can be quickly mobilised (Eggen Reference Eggen2011). As the ‘custodians of culture’, chiefs are the only actors authorised to make decisions on which sociocultural practices are allowed and which are prohibited. In many countries, chiefs also enjoy legitimacy from members of society as political authorities with the right to design, implement and enforce laws (even if these laws differ from national laws).

My second aim is to use evidence from interviews with chiefs, as well as supporting evidence gathered from focus groups and additional interviews, to outline the myriad ways chiefs work as intermediaries between state and local populations to end child marriages. How does a chief end a child marriage? What strategies are effective and why? Offering this evidence adds significantly to the growing set of literature on chiefs that examines their political embeddedness, adding to these studies the importance of chiefs as useful and necessary cultural change agents.

THE COEXISTENCE OF CHIEFTANCY AND THE STATE

Current literature on chiefs recognises them as knowledgeable, influential, and helpful gatekeepers of politics, particularly at the local level. Rather than working against elected officials and local-level bureaucrats, a broad literature points to the coexistence of chiefs with other institutions (Muriaas Reference Muriaas2009; Eggen Reference Eggen2011; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Kern and Kromrey2016). Research by scholars such as Eggen (Reference Eggen2011) highlights the continuing importance of chief systems operating in rural areas, which are often beyond the reach of central governments.

To date, scholars have examined the political embeddedness of chiefs across three broad categories: (1) voting, (2) development and (3) health. In terms of brokering votes and/or promoting elections, Baldwin (Reference Baldwin2013) and Koter (Reference Koter2013, Reference Koter2016) both find that chiefs act as useful electoral intermediaries who can influence the voting preferences of their dependents. Politicians know this and many will form close clientelistic bonds with chiefs as one way to ensure their (re)election (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2013, Reference Baldwin2016). In her lab-in-the-field experiment in Senegal, Gottlieb (Reference Gottlieb2018) finds that brokers who have the credible power to punish or sanction are most likely to sway the votes of their dependents away from their personal preferences.

Chiefs are also central figures at the local level as development agents. For example, in Zambia politicians looked to the chiefs first for information and ideas about new development projects (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2013). A third area of research involves understanding the usefulness of chiefs in promoting improved health outcomes. For example, Eng et al. (Reference Eng, Glik and Parker1990) find that chiefs in Togo use their influence to increase social pressure to encourage mothers to vaccinate their children. Using household survey data in DRC, van der Windt & Vandoros (Reference van der Windt and Vandoros2017) found no effect in health outcomes between villages run by elected officials and those led by a chief, arguing that the chiefs are just as capable of promoting health services. More recently, Dionne's (Reference Dionne2018) work on AIDS policy in Malawi finds that chiefs are central actors in leading local level responses.

I add to these studies a new dimension: chiefs acting as intermediaries between state and local populations to enact cultural reforms. I use the case of child marriage reform to explicate the central role chiefs can play in promoting both political and cultural change, particularly when the reform in question is deeply rooted in cultural practices. Drawing on the work of scholars like Eggen (Reference Eggen2011), I argue that, in countries such as Malawi, lasting reform of culturally embedded practices will not occur unless chiefs are the primary drivers of such change.

CHIEFS AND CULTURAL CHANGE

Culture typically changes either through a process of natural evolution (Smith Reference Smith2003) or ‘forced’ revolution (Harris & Ogbonna Reference Harris and Ogbonna2002). When we imagine the natural evolution of culture, we think of processes such as cultural diffusion and acculturation, or the steady exchanging and/or borrowing of traits from other cultures. By comparison, a ‘forced’ revolution typically requires the aid of a set of actors who have the power to persuade or threaten people into accepting the change. In many cases, culture is forced to change through legal reform(s).

African societies have proven resistant to amending cultural practices, even when these practices are proven to promote violence and human rights abuses (World Health Organization 2009). Laws that promote women's, children's and LGBT rights are particularly difficult to pass and, more importantly, enforce (Villalón Reference Villalón2010; Kang Reference Kang2015). Actors central to blocking the progress of these laws have primarily been traditional and religious elites. Htun & Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2013: 10) argue that if a gender status issue ‘contradicts the explicit doctrine, codified tradition, or sacred discourse of the dominant religious or cultural group’, then it is more likely that religious and traditional leaders will counter-mobilise against this reform. For example, Villalón's (Reference Villalón2010) study in the Sahel found that religious elites in particular were responsible for blocking gender reforms. Kang (Reference Kang2015) found a similar result in Niger, where religious leaders organised actors to mobilise against proposed changes to family law. Other studies in countries such as Sudan and Zambia find similar results (Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Tonnessen and Wang2018).

In this sense, the work of Malawi's chiefs to combat child marriage practices is something of a paradox. I find that most chiefs fully embrace the political reform of banning child marriage, with many chiefs choosing to pass local level bylaws that carry harsher punishments for anyone engaging in the practice, harsher even than national laws. Taking their activism a step further, many chiefs are also committed to promoting cultural reform to systematically address underlying cultural practices that make child marriage acceptable. Two important questions emerge: First, why are chiefs so invested in ending child marriage? Second, how are chiefs changing and/or challenging culture to end child marriage?

RESEARCH DESIGN

This project uses original interview data gathered in Malawi (February 2017, July 2017–April 2018, August 2018). Using a mixed-methods approach, I conducted: (1) 121 interviews with chiefs from the village to the district level; (2) 19 focus groups with approximately 124 women that gauged perceptions of chiefs and elected officials; (3) a few dozen additional interviews with ward councillors, teachers, social welfare officers, NGOs and police officers; and (4) indirect and participant observation.

Sample districts

At the sub-national level, Malawi is divided into three regions: Northern, Central and Southern. The Southern and Northern regions have a statistically higher rate of child marriage than districts in the Central region. Rural areas have higher rates of early marriage than urban areas. For example, in the capital district, Lilongwe, which is in the Central region, 40–45% of girls are married before they turn 18 years old. In comparison, between 55–60% of girls in the Southern district of Mangochi are married before they turn 18 (Malawi DHS 2015/2016).

I selected seven districts in which I conducted surveys, interviews, focus groups, and/or participant and indirect observation (see Figure 1). In the Southern region, I worked in Zomba and Mangochi districts. These districts are home to the Yao, Chewa and Lomwe tribes. In the Central region, I selected Dowa (2), Lilongwe (4), Salima (9) and Nkhotakota (6). Across these districts, I interviewed chiefs representing the Chewa, Yao and Ngoni tribes. Finally, in the Northern region I selected Nkhata Bay (14). This is one of the wealthier districts of Malawi due to fishing, trade and tourism. Nkhata Bay is the primary seat of the Tonga people.

Figure 1. Map of Malawi. Research Districts include: Zomba (27), Mangochi (21), Lilongwe (4), Dowa (2), Salima (9), Nkhotakota (6), Nkhata Bay (14).

Chief interviews

My interviews with chiefs were conducted in all three regions of Malawi. The goal was to achieve a representative sample so I interviewed the most chiefs at the level of Village Headman (VH) and moved up the hierarchy from there with fewer and fewer interviews, as each position up the hierarchy becomes rarer (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chief hierarchical structure in Malawi.

In some cases, I explained to the Traditional Authority (TA) the sampling of chiefs I wanted to meet so they could help me arrange visits. In other cases, I worked directly with hired research assistant(s) to arrange visits. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the interviews conducted by rank and gender. Interviews were individual and semi-structured.Footnote 1

Table I Breakdown of interviews conducted by rank and gender in seven districts, Malawi (2017–2018)

SOURCE: Interviews conducted in Malawi from 2017–2018.

Additional interviews

Aside from interviews with chiefs, from July 2017 to March 2018 I conducted additional interviews with ward councillors, social welfare officers, NGOs, religious leaders, teachers, mothers’ groups and police officers. All additional interviews were individual and semi-structured.

Focus groups

For a civilian perspective on the work of the chiefs and government officials on combating child marriage practices, I conducted focus groups with approximately 124 women at 19 sites in Lilongwe, Dowa, Salima and Nkhotakota. These focus groups gauged women's perceptions of their chiefs and elected officials, particularly as they relate to campaigns to end child marriage. Each focus group was conducted with 3–10 women. Participation in the focus groups was voluntary and unpaid.Footnote 2

CHIEFS AND CULTURAL CHANGE IN MALAWI

In Malawi today, over 18,000 chiefs wield significant power. Historically, powers of the chief included political and administrative powers such as allocating government aid, assisting in the collection of taxes, mitigating conflicts like land disputes, promoting development, assisting in the conducting of the national census, managing all sub-chiefs and protecting the peace (Eggen Reference Eggen2011; Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Wang, Benstead, Dulani and Rakner2019). However, the political power and influence of Malawi's chiefs have waxed and waned over time. While the early colonial government sought to co-opt the political and cultural authority of the chiefs (Cammack et al. Reference Cammack, Kanyongolo and O'Neil2009; Eggen Reference Eggen2011), by 1953 bureaucratic power was ostensibly shifted away from them and given to district-level authorities. Under the 30-year, single-party regime of H. Kamuzu Banda, chiefs loyal to the Malawi Congress Party (MCP) found favour, financial support and freedom (Cammack et al. Reference Cammack, Kanyongolo and O'Neil2009). While most chiefs were largely stripped of many of their administrative powers, their sociocultural powers were left intact.

The year 1994 ushered in a new era of multiparty democracy, and with it came more changes for the chiefs. The new ruling party, the United Democratic Front (UDF), stripped chiefs of their powers to administer land. Furthermore, Malawi's decentralisation policy in 2000 created a host of new district-level elected government positions to include ward councillors, area development committees (ADCs) and village development committees (VDCs). Now, chiefs must navigate a complicated political landscape. Scholars such as Muriaas (Reference Muriaas2009) and Eggen (Reference Eggen2011) find that, rather than creating a rigid structure of two parallel forms of government – national and traditional – the structures are quite porous, with chiefs working in and across their own structure and that of the state to provide necessary goods and services to their people.

No matter the changes made to chiefs’ political powers, their position as cultural authorities remains uncontested. From overseeing weddings and festivals, to initiations and political rallies, to allowing families the rights to bury their loved ones, chiefs continue to control most aspects of daily life. This is particularly true in the rural areas of Malawi, where over 80% of the population continues to reside.

Chiefs as custodians of culture

According to Chinsinga (Reference Chinsinga2006: 258), chieftaincy is ‘predominately defined in terms of tradition’. Senyonjo (Reference Senyonjo2004) defines tradition as any cultural product that was created or pursued by past generations and, having been accepted and preserved in whole or in part by successive generations, has been maintained to the present. Traditions might include a society's general outlook on life, institutions, their values and practices, their ways of relating to one another and of resolving disputes (Chinsinga Reference Chinsinga2006). If culture and tradition are the treasures of a society, then chiefs are: ‘[The] guardians of traditional norms, values and practices that are respected in particular communities from generation to generation – and as such [they] are an important channel through which social and cultural change can be realised' (Senjonyo Reference Senyonjo2004: 2).

In my interviews with chiefs, I asked each one what it meant to be a ‘custodian of culture’. A Senior Chief in Nkhata Bay summarised it well:

What it means is every country has got its own culture. Culture is usually … the way you marry, the way you demarcate land, your dances, it is anything to do with the life you live. Our responsibility [as chiefs] is mainly to see that our culture is not diluted. Mostly we are having problems with people who are coming from the outside and bringing other cultures, like the way they dress. My role … is to see that some of the things that are coming [in] are not bad and that some elements of our culture [are] not good. (Senior Chief #89 2017 Int.)

Across Malawi, chiefs take a leading role in enforcing the prohibition of harmful cultural practices, educating people about their harmfulness, and punishing those caught practicing them. A Group Village Headman (GVH) in Zomba explained, ‘If someone is continuing bad practices in secret and I find out, I will call them here and punish them. If someone is found doing such practices, they are to pay a goat’ (GVH #3 2017 Int.). A goat costs approximately 25,000 MWK (£26/US$34), so if a chief makes an example of just one family, most people will take the prohibition seriously.

Other cultural practices are being altered, rather than prohibited. For example, Yao tribes in the Southern region practice initiation ceremonies for boys which include circumcision. A chilangizo, initiation leader, explained to me that this used to be done on every boy child by a traditional healer using the same razor blade. Many Yao chiefs in Zomba and Mangochi are now working with local clinics and chilangizos to allow for a separate blade to be used on each person. Similar practices are being amended elsewhere on the continent, including South Africa, where citizens are encouraged to have circumcisions performed in hospitals (Nuxumalo & Mchunu Reference Nuxumalo and Mchunu2020).

One of the most deeply embedded cultural powers of the chief is their authority to perform funerary rites. The chiefs’ role is both social and economic. For example, it is the responsibility of the chiefs to announce the death of a citizen. Chiefs hold the sole authority to ‘open the graveyard’ and have a grave dug. The chief must lead an investigation into the death to determine that it was natural and not a crime (Van Breugal Reference Van Breugal2001; Cammack et al. Reference Cammack, Kanyongolo and O'Neil2009). One VH in Zomba explained, ‘If someone has passed today, before even crying, [the family] needs to come to [me] and tell [me] he or she has died. The chief can give them the authority to start crying. They cannot shed a single tear until they tell me’ (VH #39 2017 Int.).

Chiefs can also punish people using their power over death rituals. For example, if a person dies of an illness and the family did not tell the chief about the illness, especially if it is a contagious illness, the chief may delay burial as a punishment (Cammack et al. Reference Cammack, Kanyongolo and O'Neil2009). More commonly, chiefs will deny offenders the right to attend a funeral. When I asked a focus group to explain why exclusion is such an effective punishment, one woman said: ‘In our culture, we are a community and you want to be part of the community. If one does not attend funerals, he or she becomes isolated. If you isolate yourself other people are not going to attend your funeral … Who will mourn for you when you pass if you never mourned for someone else?’ (Senga Bay #8 2018, focus group).

Ultimately, if culture is defined as the practices that dictate how you live your daily life, and chiefs are the custodians of these practices, with the power to change, end or invent new ways of practicing culture, it is easy to see why chiefs wield such control in the villages. Without the support of the chiefs, changes to the culture will not be supported. NGOs know this is the reality on the ground in Malawi. Many NGO and religious representatives remarked that cultural change simply won't happen at the grassroots level unless the chief is on your side. As a representative from the NGO CARE-Malawi explained: ‘[Chiefs] are the gatekeepers to the changes we want, so we can't bypass them. There is no activity that can happen without the chief knowing it … Engaging them right from the beginning makes your job easier. They are the ones that will be the first to champion your cause’ (CARE Malawi representative #1 2017 Int.).

Chiefs combating child marriage

Given the power and influence of chiefs at the local level in Malawi, they are the actors most actively engaged with raising awareness about the dangers of child marriage, educating communities about changes to marriage laws, even forcibly breaking marriages. Importantly, chiefs want to engage in this work. Most chiefs I spoke to argued that child marriage is the single most important contributor to poverty and lack of development in their villages. Chiefs witness firsthand the devastating effects of child marriage: they comfort the families of girls who die in childbirth; they provide food and shelter to young mothers who have no education or skills; they engage in conflict resolution when a young bride is abused by her older husband. Even when faced with threats and maltreatment from their communities, chiefs persist.

This is an important finding. Many scholars argue that patriarchal institutions like the chieftaincy do not readily understand or appreciate the importance of promoting progressive values such as gender equality (Charrard Reference Charrard2001; Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Bowen and Nielsen2015). In my interviews with 121 chiefs, every chief could recite a long list of harms that accompany early marriage. In the absence of any tangible national presence, chiefs work with local partners to pass bylaws prohibiting domestic violence, child labour and early marriage. In areas where NGOs are active, the chiefs have help in this work. But there are large geographic swaths of the country where no NGOs specialising in human rights, youth or girls’ empowerment operate (Eggen Reference Eggen2011). Likewise, in villages close to a trading centre, chiefs might have the assistance of police officers, victim support units, and social welfare officers. However, for most of the chiefs living in rural, hard-to-access areas of the country, they must rely on themselves and people in their communities to promote public support for what is often seen as a radical cultural and political norm change.

With so many chiefs and community members confident in the ability of the chiefs to act as cultural and political brokers to end child marriage practices, we should ask the question: How many chiefs are actively engaged in this work? In my study of 121 chiefs, 86 chiefs (72%) have ended at least one child marriage (see Table II).

Table II Breakdown of chiefs ending child marriages, Malawi (2017–2018)

Source: Interviews conducted in Malawi by the author from August 2017–April 2018. Note: The N size is for the total of each category. So, a total of 33 chiefs have never ended a child marriage.

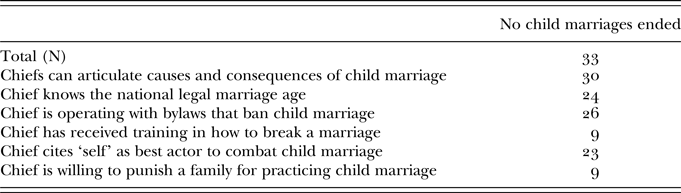

As shown in Table II, most chiefs in this study have ended between 1–5 child marriages during their tenure as chief. It is important to note that, even if a chief has not personally intervened and broken a child marriage, it does not mean they are not actively working to curb the practice, through passing bylaws, educating the community about the laws and the harms of child marriage, and working with community members to target at-risk children for assistance and intervention. If we break down just the category of chiefs who have never ended a child marriage, we get a clear picture of their activism (see Table III).

Table III Activism of chiefs who have never ended a child marriage, Malawi (2017–2018)

Source: Interviews conducted in Malawi by the author from August 2017–April 2018. Note: figures presented as part of the total (33). So, 30/33 chiefs can clearly articulate causes and consequences of child marriage.

Of the 33 chiefs who have never personally ended a child marriage, 90% can still clearly articulate the causes and consequences of early marriage; 72% know the legal marriage age; 78% work in an area with bylaws that prohibit child marriage; and 69% cite ‘chiefs’ as the actors best able to combat the practice of child marriage. It is also worth noting that 51% of the chiefs in this category have been in their position for five years or less. Additionally, 87% of the chiefs who have never ended a marriage are operating at the VH level. With more time in the position, the number of marriages ended increases. Likewise, the higher up the hierarchy they are, the more likely it is for chiefs to report higher numbers of child marriages ended.

CHIEFS ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE

How do chiefs in Malawi end child marriages? Who do chiefs work with to find the marriages and break them? How do they ensure the children are not sent back to the marriage after it is broken? Answering these questions is essential to understanding the potential power that chiefs possess to serve as political and cultural intermediaries.

Child marriage reform can be divided into four distinct phases (Figure 3). The first phase involves working with members of the community to design and implement a set of bylaws that clearly outline the prohibition of child marriage and further outline how cases of child marriage will be handled by the chiefs. The second phase finds chiefs working with a broad coalition of community members to encourage community-level understanding and acceptance that child marriage is prohibited.

Figure 3. Four phases of ending child marriage for chiefs in Malawi.

The third phase requires chiefs to provide individualised counselling to families – and sometimes even other chiefs – who are found to be in non-compliance with the child marriage ban. Most chiefs spoke of family counselling as integral to their work. By going directly into the homes of citizens, or calling the families to appear before them, the chiefs display their political and cultural authority. During this phase, chiefs rely on the guidelines outlined in the bylaws to determine whether the offending parties will be punished and in what way. The final phase is the monitoring of broken marriages to ensure that the children are not forced back into the marriage or abused or neglected by their families.

Creating and enforcing bylaws

The first step in effectively combating child marriage practices is for chiefs to work with community leaders to craft bylaws that prohibit child marriage and detail the steps that will be taken to end the child marriages that have taken place. The role of chiefs in creating and enforcing local-level bylaws – even laws that directly contradict or expand on national laws – is well cited in existing literature (Muriaas Reference Muriaas2009; Eggen Reference Eggen2011; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Kern and Kromrey2016). Across my interviews, 90% of chiefs cited using bylaws to some degree. As one female Senior Chief explained: ‘I was so thankful when Parliament changed the laws at the national level because then I wasn't alone anymore. I could point to the law and say, ‘See, this is the law of our country’. It was no longer me acting on my own’ (Senior Chief #121 2018 Int.). The bylaws are created as part of an open forum with either a chief's Village or Area Development Committee (VDC/ADC). One Area Development Committee (ADC) chairman in Dowa explained: ‘The bylaws are [usually] discussed at the ADC level. Even the TA is a member of our group and we all agree that the laws have to be obeyed … The chiefs are very democratic and we work with the chiefs constantly because they are living with us here in our area’ (ADC chairman #1 2018 Int.).

The ADC chairman raises an important point: in the minds of most Malawians the creation of a TA's bylaws is a highly democratic process, more democratic than laws passed by Parliament. A Social Welfare Officer in Dowa agreed, saying: ‘Those bylaws were designed in my presence. The bylaws are well known to the people. They were designed, drafted and are being implemented by them. It belongs to them and is from them. Not like the ones from the Parliament, oh, it's quite … different’ (Social Welfare Officer #1 2017 Int.). A VH in Dowa echoed this sentiment saying: ‘We have bylaws; we created them as a community. We had a representative from the TA, the GVHs, World Vision, members of the government headed by the Social Welfare Office, and members of the pastors’ groups. That was three years ago and we are all using them’ (VH #102 2018 Int.).

The most effective bylaws pertaining to child marriage will (1) prohibit the practice of marriage for anyone under 18 years of age with no exceptions; (2) outline the actions the chiefs and the community will take to prevent or break such marriages; and (3) detail the punishment for all parties involved breaking this law. I say, ‘all parties’ because it typically takes several people's participation for a marriage to take place including the bride and groom, their families, the chief and a religious official. The best bylaws outline punishments for these secondary actors as well, not just the immediate families, making it undesirable for any to be involved. For example, a Senior Chief in Mangochi explained:

All the VHs know our laws. If I see a VH not following the bylaws, they are not sending a child to school, I will punish them, even remove [them] from [their] position. He must give me a goat if he breaks my laws. It is my job to watch the GVHs. The GVHs watch the VHs and I will punish the GVHs. They will punish their VHs. (Senior Chief #55 2017 Int.)

It is important to note that not all bylaws are the same. While most bylaws settle on 18 as the legal marriage age with no legal loopholes, mirroring the national laws passed in 2015, enforcement mechanisms of the bylaws and punishment for breaking the bylaws vary widely. Even the age – 18 years old – is a point of contention. Many chiefs argued the age limit should be set even higher. For example, a VH in Zomba explained, ‘If someone reaches between 26 and 27 [years old], that one can get married. She can enter marriage. From 18 to 25 [years old]? No’ (VH #36 2017 Int.).

Another challenge with replicating the national marriage laws at the local level is the fact that national laws are written in English, a language most Malawians do not speak or read. Many chiefs argued that a central reason they serve as intermediaries between the national government and the people, both on matters of politics and culture, is the fact that the government operates in a language foreign to most of its citizens. Furthermore, many chiefs in this sample reported that national laws were only changed to appease international observers and that the national government has no real plan or interest in implementing the new laws. To challenge this point, I asked every chief if they knew any details of the President's plan, Vision 2020, for ending child marriage. While 52% of chiefs had heard the words ‘Vision 2020’ on the radio, they could not explain any details of the plan. Only 2% of chiefs could cite any of the government's plans for implementation, while 45% of chiefs had never heard of the plan at all. Thus, chiefs see the opportunity to create bylaws on issues like child marriage as a chance to bring governance to the people, governance they do not see central government representatives like the MPs providing. Since chiefs are operating largely divorced from the central government on this issue, it is no wonder that enforcement plans and punishments vary so widely.

Community level education and policing

The second phase of combating child marriage is for chiefs to take their newly created bylaws and conduct comprehensive community-level education and policing of the new laws. This requires a combination of persuasion and punishment. For TAs, it involves calling all their GVHs to a meeting; this usually includes other prominent officials including social welfare officers, police officers, head teachers, NGO officials and religious leaders. The bylaws are shared by the TA at these meetings and then each GVH is responsible for returning to their area, calling their VHs together, and explaining the changes to them. Once the information is in the hands of the VHs, the people are informed and community-level policing can begin. As one VH said, ‘Once I've told the people together, they know. The cannot pretend they do not know and keep breaking the law. I told them. They will be held accountable from that moment’ (VH #102 2018 Int.).

For the chiefs, education takes another form: they must sensitise people against performing harmful cultural practices. Chiefs alone have the power to use their cultural authority to prohibit cultural practices. For example, one of the most common cultural practices for girls that promotes the spread of HIV and results in early pregnancy – and by extension early marriage – involves the use of a fisi, or hyaena. A fisi is a man who deflowers young girls in a professional capacity (Warria Reference Warria2018). This practice is widespread across several of Malawi's tribes including the Chewa, Yao and Mang'anja (all represented in this study). During the initiation period for girls, families hire a fisi to come during the night to teach the girls how to have sex (Kamlongera Reference Kamlongera2007). The sex, often forced, must be unprotected. This form of sexual cleansing is considered a necessary rite of passage (Day & Maleche Reference Day and Maleche2011). However, it often results in the transmission of HIV and other STIs, as well as unwanted pregnancy.

Malawians consider it taboo to speak openly about initiation practices like the fisi, so clear data remain difficult to acquire (Tembo & Phiri Reference Tembo and Phiri1993; Kamlongera Reference Kamlongera2007; Skinner et al. Reference Skinner, Underwood, Schwandt and Magombo2013). However, for just the Southern region, conservative estimates place the proportion of girls aged 12–19 participating in initiation rites at as high as 57%, with the Yao contributing rates of over 70%. According to Warria (Reference Warria2018: 299), ‘Anecdotal evidence suggests that this could actually be higher in other parts of the country’. Chiefs spoke at length about the ways they work with their communities to dissuade them from observing this practice. For example, one Senior Chief in Dedza brought all her people together and declared: ‘God created the hyaena to be in the forest and that hyaena has four legs. So where did this two-legged hyaena come from? From this moment, I am cutting out the practice of hyaenas with two legs! The only hyaenas allowed in my area will have four legs and they will live in the bush’ (Senior Chief #121 2018 Int.).

Another way chiefs are persuading their communities to abandon harmful cultural practices is through promoting the importance of education. For example, I spoke with a GVH in Dowa who has spent every morning, Monday to Friday, for the past 12 years walking to all the villages around his area that feed into seven primary schools. Each day he goes in person to the villages and calls to the children, ‘I want everyone to go to school! Let's get prepared!’ Then the chief personally walks with the children to class. He said: ‘Most of the parents appreciate what I do and [my] chiefs are very happy … it is a sacrifice because I could be home doing work, but this is important. NGOs come here and give the message of sending children to school, [but] I am doing this work myself. It has to start with me’ (GVH #106 2018 Int.).

Chiefs also have the power to use their own families as examples that can be set for the community. For instance, a Senior Chief in Nkhata Bay said: ‘I've got a very good example of my own. My sister's daughter was selected to go to secondary school but she got pregnant. [People] said I should take her and give her to the boy but I said “No, I will take care of her until she gives birth, then I will send her back to her parents and back to school”’ (Senior Chief #89 2017 Int.).

Individualised counselling and punishment

As hard as some chiefs may try to intervene, child marriages still occur. What happens when a family conducts a child marriage? How does a chief hear about the plans? How do they intervene? For the most part, chiefs who are effectively blocking child marriages before they happen rely on spy networks stationed across their villages to inform them when a family is considering placing a girl into an arranged marriage. Spies can be anyone, male or female, of all ages and professions. One chief told me the story of a spy who keeps a hidden cell phone in his outhouse so he can call the chief in private. When his wife found the phone and accused him of cheating, the couple went to the chief's house so the chief could confirm that the man was a sanctioned spy involved in child advocacy.

When it is time for a chief to intervene to either stop a child marriage from taking place or break a marriage, the chief has two options: (1) call the families before them or (2) go to the family directly. Most chiefs I spoke with offer the in-face meeting with a family as the first opportunity for them to break the child marriage. If the family agrees to break the marriage immediately and send the child back to school, the chief takes no further action and the families are not required to pay any sort of fine as punishment. In these cases, the chiefs warn the families of the dangers of child marriage and discuss the importance of education for improving the future of the child, her family, and by extension the entire community. Chiefs also help families work through occasional financial issues, offering advice on how best to care for the child while postponing her marriage.

If the individualised counselling session proves unsuccessful, chiefs have a few options. Some chiefs, per the bylaws, will demand punishment for a family unwilling to break a child marriage. They may also report the case either to their superior chief or to the local police (or both). Each case is unique, depending on how willing the family is to break the marriage, so chiefs must be flexible. One VH in Zomba explained it this way:

If I hear that a certain child is now in a marriage from a spy, then we go there and settle the matter. If it fails, we go above to the GVH. If that fails, from there we should go to other NGOs like YONECO here in Zomba. We punish the families at that point because they broke the bylaws, so they must pay a chicken or a goat … In one case recently, we just discussed the issue and she went back to school. In another case, we had to punish them. (VH #17 2017 Int.)

Forms of punishment

In my interviews with chiefs, 66% admitted to using some form of punishment to encourage compliance with new marriage laws. The two primary forms of punishment utilised are (1) financial punishment and (2) social punishment. Financial punishment involves extracting a fine from a family that breaks the law. Families may be forced to pay a chicken (worth approximately £2.69/US$3.50), a goat (£26/US$34), or give a similar amount directly in kwacha. In most cases, fines from each family (the boy's and the girl's) are expected. Some chiefs are adamant that only one kind of payment will be accepted. For example, a Senior Chief in Dowa argued, ‘They must pay a goat. Always a goat. No chickens, no money. Because if it's not a goat they will do it again. A goat hurts’ (Senior Chief #115 2018 Int.). As one of the most impoverished countries in the world, the loss of a goat is catastrophic for a rural farming family. In this way, losing a goat to pay a fine is genuinely painful to the family. Thus, if the community knows that the penalty for breaking a law is a goat and they know it is impossible to give away a goat, they are more likely not to break that law.

However, I found that in almost all areas where the TA had set the penalty for practicing child marriage as a goat, the sub-chiefs within their jurisdiction were more flexible. For example, a VH operating within the area of the Senior Chief cited above said the following when asked whether he extracts fines:

Sometimes, yes, it depends on the situation. It depends on how cooperative the parents are. They are fined for causing unnecessary problems, one chicken from the boy and one from the girl. In the bylaws, we are supposed to fine a goat, but not many people can manage to pay that, so we warn them and they are supposed to pay a chicken. (VH #102 2018 Int.)

In some cases, chiefs are even dealing a ‘double punishment’. One VH in Zomba explained:

Sometimes people in this village choose to have a marriage without notifying [me], but when my people, when my spies, find out, the issue comes to the chief. Everything always comes to me. Then the families get punished twice because they broke the law, the national law of Malawi, and they got married without telling me, which is against my laws. They must inform me before a marriage can take place … so we punish the parents by paying with goats so that they feel pain. (VH #39 2017 Int.)

Social forms of punishment utilised by chiefs involve specific acts (or the prohibition of acts) that demonstrate to the rest of the community that a citizen has broken a law or otherwise offended the chief. For example, one female VH in Zomba said that if she fears a family cannot pay a fine, she will have them work in her fields instead. Another chief will punish families by having them perform public works, like digging a new latrine. Many chiefs admitted that they use power over funerary rights as punishment by barring errant families from attending funerals. In a few cases, chiefs went so far as to refuse families the right to bury their own dead until they broke a child marriage. A GVH in Dowa admitted: ‘We punish them by saying they cannot attend such things as funerals, or if they acquire assistance from us we deny it, so from fear of that they comply’ (GVH #93 2018 Int.).

The ultimate form of punishment utilised by chiefs is excommunication or banishment. In some cases, chiefs admitted that they banished troublesome families when they would not agree to break a child marriage. The few chiefs who admitted to using this extreme tactic only did so after other avenues were exhausted. In one case, a GVH I spoke to explained:

I've ended four marriages in my area. I called the families here and counselled them. If they are failing to end the marriage, they are supposed to be punished, so they are all aware of my threats of punishment. If they are failing to follow my instructions they are supposed to pay a chicken. If they fail in this, I will remove them from the village. Three families have now left my village. (GVH #3 2017 Int.)

There is an essential caveat to effective use of punishment: chiefs must hold themselves, their families and other chiefs to the same standards as the rest of the community. During my time in the field I heard countless stories about chiefs who punish citizens for breaking various laws, but if a member of their own family breaks this same law the chief does nothing. For example, one focus group participant in Dowa explained:

At my [village] … there was a marriage of young children. The boy was 15 years old and the girl was 14 years old. They got married and the girl got a baby quickly. She is still at the family where the boy is living. The boy is attending secondary school while the wife is at home. The chief knows and is doing nothing because the boy in question is his son. (Mndolera #4 2018 focus group)

Other problems arise when higher-level chiefs claim in their bylaws that they will hold errant chiefs accountable but do not follow through. If there is to be a punishment for chiefs for allowing a child marriage to take place, TAs must make an example of those chiefs or run the risk of their laws not being properly enforced and, by extension, their authority questioned. Many TAs I spoke to have experience in removing errant chiefs. One Senior Chief in Mangochi told me this story about a recent case of child marriage in his area:

I called the VH together with the parents of the couple. First, I punished the VH with giving a goat, because he lives in the village and he knows this should not happen. Then I counselled the families with the VH present to discuss the dangers of early marriage and the importance of going to school. The families [are] also punished. They should give a goat too … You see, at the level of the village, it is a chicken from both sides of the family, so two chickens total. Those chickens are paid at the VH level. But I had to become involved in the case, so at this level they [must] pay a goat. (Senior Chief #55 2017 Int.)

Citizen reprisals to punishment

Of the 66% of chiefs who use punishment to combat child marriage, approximately 44% cited fear of danger from the community that included threats, intimidation, bad feelings, even fear of witchcraft and death. Many chiefs cited members of their communities coming to their house in the night to intimidate them over breaking a marriage. Others said that families who were punished would spread mean gossip around the village. In a few instances, chiefs were threatened with curses for their interference. Most frequently, angry parents will bring their daughter to the house of the chief and leave her on the porch saying, ‘She's your problem now. You feed her’.

One way chiefs can avoid harsh scrutiny from their communities is to be transparent about where and how goods or money taken as punishment are being spent. For example, several chiefs admitted to keeping animals taken as punishment and using them to feed their own family. The people see this as the chiefs enriching themselves at the expense of the people. Some chiefs are now refusing to accept punishments as a private gift. Instead, they offer the animals or money to help improve the community. For example, a female VH in Zomba explained: ‘I recently ended four child marriages. I punished [the families] through paying cash of 2,000 MWK and all four marriages were ended. I then used the cash to buy salt and sugar and then I gave it to a school with an orphanage. And the families all know that is what I did’ (VH #7 2017 Int.).

In another case, a female VH in Zomba shared out the proceeds of animals taken as punishment to help cover the salaries of the teachers at the local nursery schools. In Nkhata Bay, a TA gives proceeds from punishments to the VDCs, who use the money to fund development activities. Several other chiefs mentioned taking all money made through the breaking of child marriages and using it to pay the school fees of the girls in question. In this way, if the family tries to turn the girl over to the chief to care for her, the chief has some money set aside to send her back to school.

Monitoring ended marriages

The final phase of the process is for the chiefs to continue to monitor the broken marriages to guarantee that the children are not forced back into the marriage, forced into another marriage, or otherwise abused by their families. The chief can also coordinate with the schools for the children to go back to school. Many of the social welfare officers, teachers and parents I spoke with said this is the area where chiefs are least effective. Too many chiefs are breaking the marriages and not following up to check on the status of the child.

Effective monitoring takes place on several fronts and many actors can be involved, not just the chief. First, the living conditions of the child at home need to be monitored. In so many cases where poverty is the cause of the marriage in the first place, families cannot afford to keep the child. That is why they turn to marriage. For families that refuse to take back a girl after she is taken from a marriage, the chief will sometimes work with the community to find another place for the girl to go, perhaps the home of an aunt or a grandmother. In all cases, the chief should ensure that the child is not facing abuse or neglect.

CONCLUSION

This article had two aims. First, using child marriage reform in Malawi as a case study, I find that chiefs are essential actors of political reform, particularly when policies are rooted in cultural practice. The second aim was to offer a more holistic view of how chiefs are attempting to combat the practice by providing evidence taken from interviews that highlights each step of the process. Building on the work of scholars such as Eggen (Reference Eggen2011) and Gottlieb (Reference Gottlieb2018), I find that chiefs in Malawi navigate a complicated socio-political landscape, relying on their unique cultural powers of punishment and banishment to push for child marriage reform.

In strong departure from previous work that argues traditional authorities are a barrier to improving family law (World Health Organization 2009; Htun & Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2013), evidence from my study suggests that state agencies and NGOs do not need to think of chiefs as antithetical to their work to promote democracy and human rights. In fact, when given proper training and resources, chiefs may just be the strongest, most effective force the state can deploy to promote policy changes rooted in cultural practice.

Rather than being disgruntled with chiefs using their authoritarian powers of punishment and banishment, civilians in my study applauded their efforts. In fact, I often heard Malawians assert that chiefs are more transparent, more receptive to the needs of their communities, and easier to work with than elected representatives. One woman stated emphatically: ‘If the rural areas are developing, it is because of the chiefs. If the country is developing, it is because of the chiefs. If there is security in this country, it is because of the chiefs. If there is peace in this country, it is because of the chiefs’ (Female farmer #1 2017 Int.).

My findings that chiefs are desirable agents of political and cultural change hold broad support beyond the population in this study. Recent rounds of Afrobarometer data (2017/2018) for Malawi cite chiefs as having the highest performance approval rating of any political actor (67%; compared with 32% for the president, 29% for MPs, 30% for ward councillors). They are also the most trusted of any political actor (63%; compared with 40% for MPs and 39% for local government councillors).Footnote 3

This study represents a small, qualitative sample within a single-country case study and thus its generalisability is limited. Further research is needed to understand the impact that chiefs are having in other countries with high child marriage rates, such as Chad or Niger. Would the tactics being used by chiefs in Malawi have the same effect in these countries? Do chiefs even enjoy the same status as political and cultural authorities? What about cultural reform in countries like Tanzania, which largely abolished the chief system at independence? Who is championing grassroots cultural reform in the absence of chiefs? Again, further case studies are needed.