Introduction

‘Evil’, warned the November 1915 edition of the Women's Christian Temperance Union's (WCTU) magazine, the White Ribbon, ‘is never more active nor more openly aggressive than in times of war, when the passions of men and women alike are roused…and when many of the ordinary restraints of convention and public opinion are slackened’.Footnote 1 World War I pushed groups like the WCTU, but also other middle-class (and particularly white) Capetonians, to view Cape Town as a place of increased moral corruption. Within this, women, and young girls, were framed as responsible for upholding the moral and racial integrity of the city, nation and empire. This article argues that whilst this discourse was prevalent prior to World War I, the material conditions of wartime Cape Town were integral to accentuating it.

World War I was a moment of material change – with significant demographic, infrastructural and material implications for the cities and people involved (Jay Winter and Jean-Louis Robert's first volume, Capital Cities at War: Paris London, Berlin 1914–1919, makes this particularly clear, as does Stefan Goebel and Derek Keene's Cities into Battlefields: Metropolitan Scenarios, Experiences and Commemorations of Total War and Jerry White's Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War).Footnote 2 In turn, these material changes to the city interacted with ideas about the city and its various inhabitants. This article affirms Vivian Bickford-Smith's approach to recognize the importance of, and interrelation between, both these ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ components of a city.Footnote 3 On this basis, it contends that wartime material changes to Cape Town were important to understanding the heightening of moral anxiety in the city, and that this, in turn, placed greater emphasis on the position of women, and particularly those of the white, English-speaking middle class, as the moral bastions of society.

This article further adds to the small body of research that has been done on South African cities and World War I – in fact no specific urban-history-based work appears to exist. Bill Nasson's World War One and the People of South Africa is the most recent and holistic contribution to the history of the Union and the war, and whilst it touches upon opinions and experiences of South Africa's urban populations during the war, the city itself is not the focus.Footnote 4 Other publications have specifically focused on, or integrated, the ‘national’ story,Footnote 5 the military history of the war,Footnote 6 particular events,Footnote 7 specific troop or soldiers’ histories,Footnote 8 propaganda and the war,Footnote 9 identity-politics and the warFootnote 10 and its commemoration.Footnote 11 Exploring Cape Town's wartime urban history also heeds the call by Ross J. Wilson, writing about New York and World War I, to produce city histories during the war that look beyond Europe. The focus on the latter (‘rubble cities’ or ‘cities in ruins’) has become an imaginative short hand for all urban experiences of the wars, when it is clearly not universal.Footnote 12

Women are central to this exploration into the material and moral effects of the war on Cape Town as discourses around them represented a nexus between concerns about health, race and morality. This argument has long been made by the likes of Ann Laura Stoler and Anna Davin. Stoler emphasizes that women were vital to the colonial project and that early twentieth-century concerns about infant welfare and racial degeneration exposed the ‘vulnerabilities of white rule’, and the need for countermeasures to ‘safeguard European superiority’.Footnote 13 Davin has similarly focused on the ‘pervasive’ influence of Eugenics at this time and the positioning of motherhood as integral to the future of Britain and the empire.Footnote 14 This was reflected in the rise of infant welfare movements which campaigned for improved medical facilities and educational programmes for mothers and their children. Within the South African context, Sarah Duff demonstrates the connections between the Union's and Britain's child welfare movement, arguing that South African welfare societies – such as the Society for the Protection of Child Life (SPCL), founded in Cape Town in 1908 – were increasingly directed towards ‘a South Africanist project’ that sought to solidify white rule,Footnote 15 whilst Jennifer Muirhead links anxieties around ‘poor whites’ (largely poor, rural Afrikaners who were forced to move to the city) to the early twentieth-century child welfare movement in the Union.Footnote 16

Studies have also examined the effects of World War I on discourses around motherhood. Referring to Britain, Katie Pickles has emphasized that ‘maternal identity’ was particularly stressed during the war.Footnote 17 Susan Grayzel has similarly demonstrated that the war heightened ‘the emphasis on motherhood as women's primary patriotic role and the core of their national identity’. Footnote 18 It was particularly the loss of the empire's white men as ‘cannon fodder’, however, that re-enforced the anxiety around child welfare.Footnote 19 Whilst Duff shows how the war (and English-speaking middle-class attitudes to poor Afrikaners) challenged the work of child welfare groups in Cape Town, and Susanne Klausen connects wartime anxieties around the future of white South Africa to an intensified discourse around racial degeneration, there has been no serious attention given to the nature of the wartime city itself in contributing to ideas around motherhood and morality.Footnote 20 This article thus offers a unique perspective by emphasizing the importance of the city's material conditions in enflaming concerns around morality and the maintenance of white minority rule. As such, ideas emanating from the powerful white middle classes about the future of the Union were grounded in developments and experiences in the Union's cities.Footnote 21

The context of Cape Town at the outbreak of war

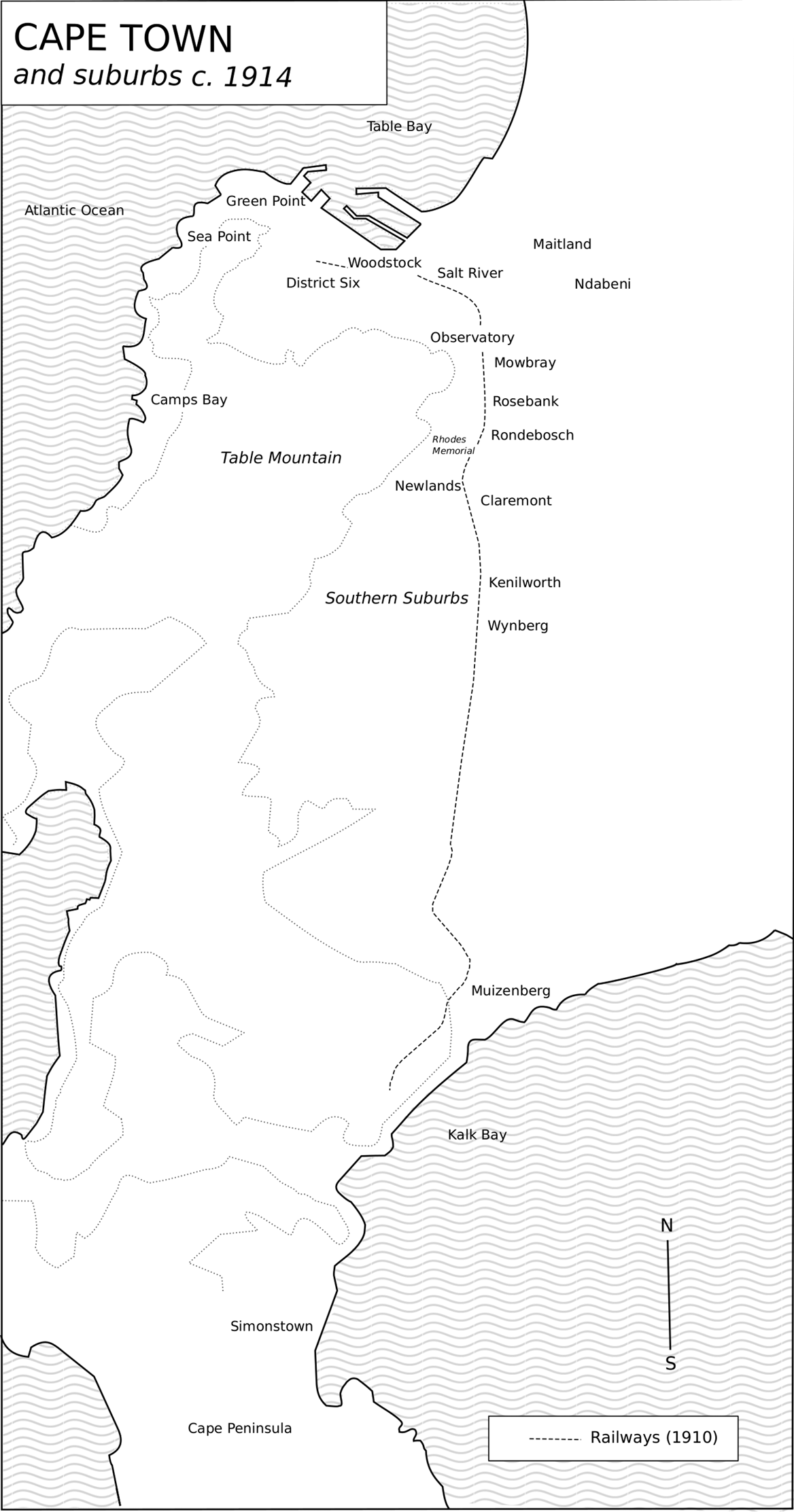

In August 1914, the Union of South Africa, as a Dominion of the British empire, entered World War I. The nature of this involvement was hotly contested by the nation's ruling white elite, whilst reactions from the largely disempowered black and coloured sections of the population varied from apathy, to anxiety, to strong calls of pro-British loyalty (Figure 1). Cape Town's response was a seemingly cohesive cry in support of Britain. Nevertheless, the news was met with great anxiety. Despite the recent formation of the Union in 1910 (forged out of the former colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange Free State by a pro-British Dutch elite who saw the future of the country developing within the realm of empire),Footnote 22 the Anglo-Boer War had ended just over a decade earlier. Ten years was not a long time to forgive and forget a war, and there was great uncertainty about how an imperial war would affect the Union.

Figure 1. Map of the Cape Peninsula, 1914. In 1913, the city's various municipalities united to form Greater Cape Town (with the exception of Wynberg).

Cape Town was a ‘cosmopolitan’ city, and its people reflected its history both of slavery, starting after the Dutch East India Company first laid claim to the Cape in the mid-1600s, and later, from the 1800s, of British settler colonialism. It had been transformed into a British city over the course of a century of British rule – through education, language, culture, architecture and institution, Britishness became hegemonic.Footnote 23 On the eve of war, approximately 53 per cent of the city's population was white, whilst 46 per cent of it was colouredFootnote 24 (see Table 1 below). At this time, Cape Town's black population was notably small, sitting roughly at 1 per cent.Footnote 25 (Under the Cape Acts 40 of 1902 and number 8 of 1905, it was unlawful for black people living in Cape Town to reside anywhere but in the ‘location’, Ndabeni, with the exception of live-in domestics, property owners and those people qualifying for the franchise).Footnote 26

Table 1. Suburban population of Cape Town, according to census categories of 1911

Source: Union Government of South Africa 32, Census for 1911 (Pretoria Government Printer, 1912), 86–7.

Despite the city's cosmopolitanism, it has now been widely acknowledged that segregation was an established, albeit inconsistent, feature of the city by the early twentieth century.Footnote 27 White Capetonians (although not all) increasingly defined ‘Britishness’ in terms of a ‘kith-and-kin’ or ‘ethnic variation’, which presupposed a common ‘ancestry, history and culture’.Footnote 28 As such, they looked down upon those who had assumed or adopted Britishness through acculturation – something which was overtly evident when one's skin colour differed.Footnote 29

The city centre itself was divided into wards, or districts (see Figure 2), and the more affluent areas, such as ‘Gardens’, were predominantly white. This contrasted with poorer locales, such as District Six. The latter, which lay on the east edge of the city, held a predominately working-class coloured population which was interspersed with poor Afrikaners, Indians, Greeks, Germans and ‘some immigrant Jews, Britons, and Italians’, who ‘still lived cheek-by-jowl’.Footnote 30 Even in areas which were generally considered ‘poor’, white Capetonians were, on average, half as cramped as their coloured and black neighbours (there were 1.7 times more coloured and black Capetonians per room across the city).Footnote 31 This disparity reflected the unequal access that coloured and black Capetonians had to education and wealth.

Figure 2. Ward map of Cape Town city centre, 1917.

Material changes and challenges to the wartime city

The war affected Cape Town both imaginatively and materially. It was seen in advertising, in fashion and literature. By September 1914, Heynes Mathew at 17–19 Adderley Street was advertising Kodak cameras to men ‘off to the front’ – ‘just think of the many interesting pictures you can get on trek, in camps, groups of your comrades’. New fashion trends appeared in the display windows of Garlick's Department Store – ‘German Kulture’, declared the South African Domestic Monthly in March 1915, could not destroy fashion, ‘even at the very edge of the veld.’ Footnote 32 The war was woven into cinema (or the ‘bioscope’) and theatre.Footnote 33 By the first week of November 1914, the ‘first public attempt to turn the war to dramatic uses’ it was announced, could be viewed at the Tivoli theatre.Footnote 34 Bioscopes jam-packed soldiers and civilians together, and displayed war-themed dramas and informative newsreels. They were also used for recruiting. At the Tivoli and Alhambra in December 1915, Major Bass’ call to arms was heralded by three trumpeters, with similar scenes across the city at Wolfram's, Fisher's Grand Theatre and the Opera House.Footnote 35 Music and song were other avenues through which the war was woven into the soundscape of the city. After bioscope and theatre performances, ‘God save the King’ was sung,Footnote 36 whilst on sports fields and in school halls, war-related tunes could be heard. In District Six, the song ‘Here's health unto his Majesty’ was performed during a November 1914 concertFootnote 37 at the largely black Zonnebloem CollegeFootnote 38 (which was founded by the first bishop of Cape Town in 1858 ‘for the purpose of educating…the sons of Native chiefs and other members of the Bantu and mixed races in South Africa’).Footnote 39 It is unclear if all the students were entirely enthused – the programmes left over from these occasions offer little nuance. Nevertheless, patriotic songs were particularly common during war-related occasions, including ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’, ‘Soldiers of the King’, ‘It's a Long Way to Tipperary’ and ‘Land of Hope and Glory’.Footnote 40

The war also changed the city by militarizing certain spaces and altering where civilians were permitted to be. The initial uncertainty about the safety of the city saw measures put in place for the protection of the Cape Peninsula. Sizable sections of Table Mountain, for example, were declared prohibited areas – much to the disappointment of avid hikers of the Cape Mountain Club, with the exception of the permit ‘under the hand of the mayor’.Footnote 41 Perhaps the most overt sign of the war's presence in the city was the presence of uniformed troops in the Peninsula. This was one of the first features to mark Cape Town noticeably as a city ‘at war’. Alice Green, writing to her brother ‘Eppy’ in September 1914, wrote of the troops encamped at ‘Groote Schuur and elsewhere along the mountain’, who, after totalling ‘more than 10,000…all vanished as silently and suddenly’ as they had come.Footnote 42 Of all the passing troops, it was the Anzacs who left the largest impression on Cape Town, and particularly so after 1916 when the route past the Cape was increasingly used. The Australian troops travelled in convoys of four or five ships, each holding between 1,500 and 2,000 troops on board.Footnote 43 By the end of 1916, according to one report, ‘approximately 40,000 men were provided with refreshments, entertainments and other troops services’.Footnote 44

The presence of soldiers was one of the main material changes to the city that fed into a climate of heightened moral concern. Reports of soldiers ‘constantly’ visiting ‘unsavoury’ areas in District Six flamed the fires of moral outcry. Conveniently located in close proximity to the main thoroughfare of Adderley Street, the Castle (the old Dutch fort was used as the imperial military headquarters during the war) and the Harbour, troops did not need to wander far to visit the illicit bars and brothels of the district. ‘If our nation ever comes to an end’, argued the White Ribbon in April 1915, ‘it will not be by war with another nation…Our danger lies from within, from vice and evil.’Footnote 45 The idea that women's virtues could uphold ‘civilization’, as discussed earlier, drew upon early twentieth-century ideas about the empire's future (white) generations and the sustainability of the British colonial project. Within South Africa, it reflected concerns about maintaining white hegemony in order for the country to develop along modern and ‘civilized’ lines. Replicating the call for young men to volunteer, the White Ribbon thus appealed to young girls:

Your country needs you!…In the battles to be fought, and which women can share and take part in, all are needed and the delicate, refined, gentle girl can take up her place beside her stronger comrade. Boys and men go out from their homes with the influences of mother and sister around them. It is the girls they meet everywhere that must help them to maintain right ideals of womenhood.Footnote 46

This discourse wove together patriotism and moral purity and, at the centre of it all, middle-class, white women were framed as the bastions of civilization and empire.

Groups such as the WCTU believed that troops in the Peninsula would be best looked after by steering them away from the morally distasteful distractions of games, booze and bodies, and that the warm smiles of respectable women accompanied by tea and cake would be a pleasing way to welcome troops into the city.Footnote 47 The Mowbray WCTU branch, for example, entertained 33 young men from the HMS Goliath in early 1915. After being served refreshments ‘in the shape of melons, buns and lemonade under the shade of trees in the Avond Rust garden’, they were accompanied to Rhodes Memorial and the zoo.Footnote 48 Abstinence was also stressed as a way to counter immorality.Footnote 49 Inspired by Lord Kitchener's call for a teetotal war in 1914, and more pointedly the king's own pledge to abstain from alcohol, the WCTU initiated their temperance campaign in May 1915. Many ladies spent their weekends providing tea and handing out white temperance badges to troops visiting the Feather Market at the bottom of Dock Road and, by 1917, they boasted between 600 and 700 pledges.Footnote 50

Troops may have been one of the main focuses around wartime morality for middle-class women, but their attention was also inward-looking. The idea that girls might be swept up in wartime passions, or ‘Khaki fever’, raised concerns about their moral sanctity.Footnote 51 This discourse varied according to race and class in the city. For middle-class white girls, this rested upon the idea that they were the future mothers of the South African nation. It was along these lines that Dr Lillian Robinson encouraged ‘purity’ to be taught as a form of patriotism, as ‘the nation wanted hardy, self-reliant women for its future mothers’.Footnote 52 This was echoed by the WCTU and sister societies, such as the ‘League of Honour’, set up through the National Council of Women (NCW) in May 1915,Footnote 53 and the Child Life Protection Society (CLPS).Footnote 54 It was further believed that white working-class girls should be elevated to ‘respectable’ standards of living. This upliftment, however, also stemmed from fears that miscegenation (and thus racial degeneration) was endemic in the city's multi-racial impoverished quarters, such as District Six. This was echoed in the desire to instil working-class, coloured girls with middle-class, Christian values. Whilst much of this work was driven by genuine concern for their welfare, it was also a question of limiting miscegenation and population control within the urban context. A seeming result of this increased wartime anxiety around the moral fortitude of the city's poor females was the establishment in 1915 of the Stakesby-Lewis Hostel for coloured women in Loop StreetFootnote 55 (with the help of a visiting Scottish WCTU member, Miss Lochhead),Footnote 56 and the opening of the Marion Institute for coloured ‘wayfarers’ by Mrs Carter, the Anglican archbishop's wife.Footnote 57 The former also represented the formation of the Cape Town's ‘Coloured WCTU’, which sought to help poor, uneducated coloured girls become ‘respectable ladies’, by instilling in them the virtues of Christianity and Temperance (it also encapsulated the aspirations of the coloured petty-bourgeoisie).Footnote 58 At their first annual meeting, parents were advised by one ‘Mrs Earp’ to ‘keep their children from associating with European men’, whilst emphasizing that ‘if their daughters went astray, it was the fault of the mothers’.Footnote 59

The introduction of women's patrols by September 1915 was another way in which respectable Capetonian women sought to maintain the proper rules of feminine conduct, by countering ‘“excessively familiar talk with soldiers of uncertain character”’.Footnote 60 These patrols were lobbied for by the NCW and the WCTU, who had taken increasing interest in the women patrols in Great Britain, Canada and the United States.Footnote 61 The wartime departure of policemen and the strains experienced by the police meant that the WCTU and the NCW had greater leverage with which to push their cause.Footnote 62 Adorned with special badges, these volunteers were tasked with spotting recognized prostitutes, patrolling public spaces and befriending ‘any girl who needs it’.Footnote 63

The presence of soldiers may have been a significant source of moral anxiety in the wartime city, but this anxiety was also exacerbated by deeper, infrastructural urban challenges. Increased urbanization, the development of factories and a wartime rise in the cost of living led to concerns about the moral and material welfare of the city's poor. Much of this was directed towards working-class women.

The wartime increase in Cape Town's population linked to fears around the material and moral corruption of the city. According to the 1911 and 1921 censuses, the city's population increased from roughly 150,000 to 183,000 (22 per cent).Footnote 64 The substantial increase in the city's white population, of roughly 30 per cent, reflected the number of poor, rural Afrikaners who retreated to the city during the war out of necessity.Footnote 65 This linked to a broader process of agrarian transformation, stemming back to the late nineteenth century. Footnote 66 Poor, rural farmers were further affected by the years during and after the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), including a post-war depression (1903–9) and waves of drought and pestilence.Footnote 67 Whilst these factors had already triggered a movement of ‘poor whites’ into the city before World War I, the war years themselves saw little reprieve. With the collapse of the Ostrich feather industry upon the outbreak of war, the resurgence of drought years in 1916–17 and the substantial wartime rise in the cost of living, urban resettlement was the only option for many. Cape Town's black population similarly saw a substantial increase during the war years. For example, Ndabeni increased by 132 per cent between 1914 and 1918, from 1,536 people to 3,561. This was, according to the Department of Native Affairs, a result of the increased demand for ‘native labour’ during the war, which had caused many men to ‘flock to the Cape’.Footnote 68

The growth of the city's population during the war put the city's housing system under enormous strain. In fact, the Acts of 1902 and 1905, which prevented black men and women from residing outside of Ndabeni (barring exceptions), were increasingly waved as a result of the location's overcrowding during the war.Footnote 69 Poorer areas like District Six were also particularly affected by urbanization, as they were the more affordable choice for newcomers to the city.Footnote 70 The deplorable state of overcrowding in impoverished areas, exacerbated by the war, fuelled concerns around poor whites, miscegenation and the corrupting influences of racially mixed ‘slums’. By 1919, it was admitted in a Report on Housing in the Peninsula that the city now required roughly 3,500 houses for its ‘poorer classes (both white and coloured)’, which amounted to 30 per cent of the overall housing shortfall for the Union's total urban areas.Footnote 71

Concerns about poor whites and racial degeneration in Cape Town's ‘slums’ were also reflected in the discourses around the ‘protection of child life’. Speaking at the opening ceremony of ‘Children's Week’ in April 1916, inaugurated by Lady Buxton through the CLPS, the chief justice of the Union, Sir James Rose-Innes, urged that,

Of all the tragic aspects of the great struggle which is going on, the most tragic is the profuse expenditure of young life…that should press upon us the desirability that the young children which are growing up shall be made as efficient as possible to take their place in the struggle in the future.Footnote 72

Rose-Innes continued, stating that there was ‘no portion of the British Empire’ in which ‘the child is such a valuable asset as South Africa’. His argument positioned white South Africans as the ‘trustees of civilization’ in Africa and as such, he warned against the dangers of seeing ‘civilized children, white or black, flung into the sea of barbarism and ignorance’.Footnote 73 The city's medical profession supported these views and, in 1916, the Cape British Medical Association published the Training of our Girls which proposed motherhood as key to securing racial and national well-being as ‘healthy mothers’ meant ‘healthy children’.Footnote 74 The idea that large swathes of the white population – generally poor Afrikaners – were moving into impoverished urban areas and ‘degenerating to the socio-economic condition of blacks’, threatened white hegemony in the country, and ‘civilization’ itself. Footnote 75 The upliftment of poor mothers and their children was accordingly perceived as vital to counter these dangers.

The substantial rise in the cost of living during the war accentuated anxiety around child welfare. By 1917, prices were 40 per cent higher than their 1910 levels.Footnote 76 Monthly expenditure for a family of five in Cape Town was estimated to have increased from £13 11s 4d pre-war to £18 16s by November 1917, whilst the city had the lowest effective wages in the Union from 1914.Footnote 77 The CLPS thus noted in September 1917 that the ‘staggering shock of war’ had chiefly affected the poor. Tinned milk, it was revealed, ‘has now got beyond the reach of the purses of slum mothers…Cow's milk was always so; but now there is no alternative, not even the inferior one of condensed milk.’Footnote 78

The growth of factories in Cape Town during the war was another reason for the city's burgeoning population and subsequent concerns about morality, motherhood and the future of the white races. This was enabled by wartime conditions, which created a bubble of protectionism for the Union.Footnote 79 Factory production in the Cape Province as a whole increased during 1915–21 by 141 per cent.Footnote 80 By 1920–21, Cape Town was responsible for 88.2 per cent of the factory production in the province, and the largest concentration of industry lay in food production, at 26.4 per cent. The number of bakeries and biscuit factories grew from 71 to 120 between 1915 and 1919, with coloured female employees increasing by 320 per cent.Footnote 81 By 1917, the labour registration officer of the Department of Mines and Industries, Mr Harry Beynon, estimated that there were at least 5,000 female factory workers, the majority of whom were coloured and under 19 years of age.Footnote 82 Factory work was thus linked to the increasing presence of mostly coloured, but also poor Afrikaner, women coming into Cape Town from the impoverished farmlands of the Western Cape during the war, in search of work.Footnote 83

It was this rise of women in factories that helped feed into anxiety around morality and motherhood during the war. One of the chief concerns was that children were being neglected as a result of absent mothers and, after being approached by the NCW, the city council opened a municipal day nursery in early February 1918 ‘in the vicinity of Sir Lowry Road’, District Six.Footnote 84 The other concern was that working-class women were spending their wages on alcohol. This likely drew upon public discourse in Britain which targeted working-class women as the site of increasing moral corruption.Footnote 85 Indeed, Mrs K. van der Blerk, writing in August 1918, noted that ‘a great deal has been written of late about the wicked misuse to which girls at home, who are earning big wages in munition factories, are putting their money. It is said they are simply wasting it on foolish luxuries, and often spending it on drink.’Footnote 86 Alcohol had been the target of temperance campaigns in the Peninsula during the war, but attempts to shut down liquor-selling businesses in the city were repeatedly overturned as a result of opposition from the Peninsula Licensed Victuallers’ Association (which consisted of a politically connected stratum of liquor producers and retailers in the Cape). The desire to limit working-class women's access to alcohol, however, was widely accepted and, in 1918, legislation banning the sale of liquor to women was introduced.Footnote 87 Although this stirred up ‘a great deal of feeling’ within women's groups (both the NCW and the WCTU felt that the ban was sexist), they conceded that it was necessary ‘to safeguard many women who are exposed to great temptations’.Footnote 88

In contrast to the corrupting influence of wages on working-class women, another, seemingly opposite, worry emerged, linked to their inadequate pay. Most young (and particularly coloured) girls were heavily exploited, working long hours and in unsanitary conditions. This was particularly true in the numerous garment factories which were rapidly established in response to the wartime demand for uniforms.Footnote 89 Concern regarding the exploitation of women in factories fed directly into a 1917 Report on the Regulation of Wages Bill, which concluded that girls (sometimes as young as 12) were largely underpaid, making a decent standard of living impossible. Many factory owners justified low pay by arguing that females were dependants,Footnote 90 yet many were responsible for supporting children, parents and siblings. The Reverend Caradoc Davies of Maitland reported that a widow with five children who worked at a cardboard factory received only one shilling a day, whilst a girl at a sweet factory earned between six and seven shillings a week, with which she supported ‘her very poor mother’.Footnote 91 Across the city's factories, most white apprentices were receiving £1–2 per month whilst ‘improvers’ (or mid-level) were paid between £2 and £3 per month. Skilled workers could be given as little as £2 8s per month, although their pay averaged around £5 per month. The committee estimated that the lowest wage which a ‘grown-up girl’ could live on ‘decently’ was £5 a month, but it left no room for savings or luxuries.Footnote 92 Even then, these figures refer only to the wages of white women and do not reflect the fact that many factory owners paid coloured women less, believing they did not require the same standard of living.Footnote 93

The poor pay of women factory workers raised concerns that they were forced to ‘eke out their income by immoral means’,Footnote 94 particularly considering the wartime hike in the cost of living. It is, however, difficult to state how many women turned to prostitution during the war. The assistant medical officer of health for the Union, Dr J.A. Mitchell, approximated that, in Cape Town, there were roughly 50 European and 300 coloured prostitutes who were professional (‘who lived solely on prostitution’), with a much larger, unknown number of women who were clandestine or occasional ‘street-workers’.Footnote 95 As seen in Figure 3 below, there is an overall trend of increasing prostitution during the war years, despite a dip in April 1915 when only five women were arrested (although, as with all records, these numbers need to be taken with caution).Footnote 96

Figure 3. Arrests for prostitution and vagrancy, Cape Town, 1914–1920.

What is known is that the majority of arrests for solicitation during the war were for destitute, coloured girls under the age of 21. Vagrancy arrests further reveal not only a high proportion of prostitutes, but a large number of coloured young women more generally speakingFootnote 97 (for example, one prostitute, Rosie Murphy, in a case against her pimp, revealed to the magistrate that she lived ‘in the mountainside’).Footnote 98 Ultimately, it appears that the turn of impoverished females to prostitution might have been more than a reflection of the climate of heightened anxiety around morality, and was also a reality grounded in everyday hardships, exacerbated by the war.

Conclusion

At the end of 1918, legislation was passed that granted women the right to be town councillors in the Cape Province. The Women's Enfranchisement League and the WCTU had campaigned for this right during the war as ‘a woman reformer without the vote is like a soldier without a gun, an army without ammunition’.Footnote 99 In part, the passing of this legislation was enabled by the ‘absence of enlisted men’,Footnote 100 but it also reflected the idea that women were particularly capable of guiding questions of morality and child welfare which, as has been demonstrated, were deemed vital to urban order and the future prosperity of white minority rule. The material effects of World War I on the city certainly played a role in cementing this belief, aided by ‘Khaki fever’ and the increasing death-toll of the empire's (white) men. Indeed, other legislation enacted after the war, including the 1919 Health Act, the 1920 Housing Act and the 1923 Native Urban Areas Act, similarly linked to concerns about the health of the white races and the nature of the Union's cities.Footnote 101

This article has demonstrated that women were at the centre of these ideas around war, health, race and the urban environment, and that action was largely driven by the white middle classes. It has also shown that the discourse was varied according to the race and class of different Capetonian women. For middle-class white females, it rested upon the idea that they were the future mothers of the South African nation, and that they were also responsible for guiding the moral lives of men. It was also believed that white working-class females should be educated and elevated to ‘respectable’ white standards of living. This upliftment reflected fears that miscegenation was rampant in the city's multi-racial impoverished quarters, such as District Six, which were under increasing strain during the war. This approach was similarly seen in the desire to instil working-class, coloured females with middle-class, Christian values. Even if much of this work was informed by genuine concern for their welfare, it too was a question of population control in the urban context. Increased urbanization, the rise in the cost of living and the increasing availability of factory work to working-class women further incensed fears of their moral corruption and their ability to fulfil their roles as mothers. These ideas were powerful in that they fed into new legislation which increasingly emphasized a white-welfarist approach and informed ideas about the future of South African cities.