Introduction

It is well known that organic agricultural production is developing dynamically around the world as the number of farmers converting to organic production increases (Willer and Lernaud, 2016; Eurostat 2018). As has been shown in studies, agricultural research and education in Europe has played a major role in the advancement of agriculture and land use (Porceddu and Rabbinge, Reference Porceddu and Rabbinge1997; Mulder and Kupper, Reference Mulder and Kupper2006). Productivity per hectare – the efficiency and efficacy of external inputs – has increased as the scientific basis of agriculture has expanded through the adoption of new knowledge and technology (Kivinen et al., Reference Kivinen, Nurmi and Salminiitty2000; Chaplin et al., Reference Chaplin, Davidova and Gorton2004; Akkamahadevi et al., Reference Akkamahadevi, Sreenivasulu, Sreenivasa and Lankati2018). Nevertheless, the future of agricultural education depends on more than just higher yields; it also needs a broader view that includes environmental conservation and protection, climate change mitigation tools, sustainable agriculture, precision agriculture and technology, geo-information systems and innovative agricultural entrepreneurship (Porceddu and Rabbinge, Reference Porceddu and Rabbinge1997; Mulder and Kupper, Reference Mulder and Kupper2006). Societies are changing, and so should agricultural education. Graduate and undergraduate studies in agriculture and agricultural engineering, along with agricultural vocational training schools, are examples of the broad changes in education in agriculture and natural resources (Kunkel et al., Reference Kunkel, Skaggs and Maw1996). This is a key issue because some researchers believe agriculture is not undergoing a generational change, which is not the case of organic farms, where organic farmers are often younger than their non-organic counterparts (Green and Maynard, Reference Green and Maynard2006). In consequence, the younger generation needs to be better prepared for the changes in agriculture and its markets, which are driven by higher incomes and greater demand for high-income elasticity goods and services. Issues such as health concerns, environmental respect and food quality are motivating the organic revolution, which is well-known, yet not widely implemented in agricultural studies.

Few research studies have acknowledged the importance of education in agriculture, especially the importance of the future employability of students in the organic sector of the agricultural industry. Organic farming requires more labor than conventional farming, and leads to higher rural employment (Jansen, Reference Jansen2000; Offermann and Nieber, Reference Offermann and Nieber2000), which should be an incentive for agricultural education programs. We present an innovative study to provide the point of view of stakeholders toward employing qualified graduates in their companies. To our knowledge, this study is the first time organic agriculture industry stakeholders (employers) across Europe have answered questions related to issues about the appropriateness of current agricultural education and training for employment in the organic agriculture industry, stakeholders’ interest in training students for employment and what kinds of abilities and skills are needed for employment.

Empirical methods

Survey procedures

A survey with stakeholders from all links of the organic food chain was carried out in 2015 in seven European countries: Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain. The study was designed and conducted by partner universities of the European project titled ‘Innovative Education toward the Needs of the Organic Sector’ (https://epos-project.net/). The University partners were (1) Warsaw University of Life Sciences, (2) Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, (3) University of Kassel, (4) University of Helsinki, (5) Estonian University of Life Sciences, (6) University of South Bohemia in Ceske Budejovice and (7) Università degli Studi della Tuscia.

The main objective of the survey was to identify the knowledge and skills most attractive to stakeholders (employers) in the organic agriculture sector for the agricultural education sector. Stakeholders included ministries and other public bodies, certification bodies, advisory services, education and expert organizations, farmers, processors and traders. All stakeholders interviewed followed or were familiar with Organic European Regulation n. 834/2007 concerning organic production and labeling (and repealing Regulation n. 2092/91). Stakeholders were contacted through national organic agriculture networks to obtain the largest possible sample (Casagrande et al., Reference Casagrande, Peigné, Payet, Mäder, Sans, Blanco-Moreno, Antichi, Bàrberi, Beeckman, Bigongiali, Cooper, Dierauer, Gascoyne, Grosse, Heß, Kranzler, Luik, Peetsmann, Surböck, Willekens and David2016), and then randomly selected based on their availability to participate in the survey.

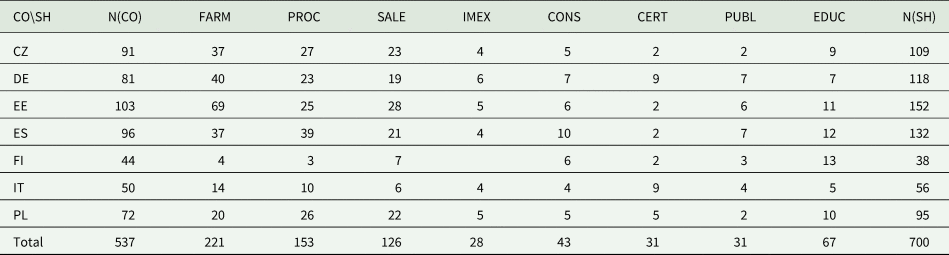

A questionnaire with closed-ended and open-ended questions was created by the project partners to encompass the diversity among the stakeholders (Table 1). To test whether the questions were understandable, several non-target groups were asked to read and answer the survey. Closed-ended questions were drawn up in order to cover the diversity among the stakeholders. This allowed a statistical approach to multi-component analysis to reveal groups of stakeholders with similar behaviors or attitudes. Open-ended questions were added to obtain additional information for certain answers.

Table 1. Number of responses from stakeholdersa (SH) in each country (CO)

CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; EE, Estonia; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; IT, Italy; PL, Poland; FARM, Farmers; PROC, Processors; SALE, Salesmen; IMEX, Import/Export; CONS, Consultants; CERT, Certifiers; PUBL, Public service; EDUC, Educators.

a Due to multichoice options for stakeholder questions the N(CO) and N(SH) can differ.

The questionnaire was divided into five sections. The first section included the socioeconomic demographics of the stakeholders and information about their business or institution. The second section included questions related to the willingness to employ graduates in the organic agricultural industry. Stakeholders indicating a positive answer were subsequently asked to indicate their preference on the educational level of their employees (high school graduate, vocational school, bachelor, master degree, etc.). In addition, respondents were asked to rank on a five-point Likert scale the theoretical knowledge and practical skills they would expect from graduates. Beyond this information, respondents were asked about their level of satisfaction with the current degree of skills of university graduates in organic agriculture, and their preferences between traditional and more innovative teaching methods.

The questions were first written in English to establish a common understanding among the partners, and then translated into the national languages of the partners' countries. National languages were used to make it easier for the respondents to understand and answer the questions. This also strengthened the validity of the research and increased the willingness to participate in the survey. Next, the answers to the open-ended questions were translated from the national languages to English. In both cases, attention was paid to careful translations so as not to lose any information in the dual translation process.

Acceptable response rates were achieved by using two data collection techniques: structured interview and on-line survey. Interviews with individual stakeholders were conducted by researchers who were instructed to read questions exactly to avoid influencing the respondents in any way, and complete the questionnaire according to each respondent's replies. The on-line survey was delivered via websites and social media (Facebook). It was also possible to combine these two data collection techniques. The partners were free to choose the technique that best suited them.

Description of interviewed stakeholders

Detailed information regarding the number and socioeconomic demographics of the stakeholders for each country is reported in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Our data come from a unique dataset of 700 interviews with 537 stakeholders. In some cases, a person represented two different categories (e.g., processor and salesman), so sometimes two responses were collected from the same person. This explains why the number of respondents (CO) was lower than the number of responses (SH) in Table 1. Like Casagrande et al. (Reference Casagrande, Peigné, Payet, Mäder, Sans, Blanco-Moreno, Antichi, Bàrberi, Beeckman, Bigongiali, Cooper, Dierauer, Gascoyne, Grosse, Heß, Kranzler, Luik, Peetsmann, Surböck, Willekens and David2016), the objective was to collect at least 30 surveys per country.

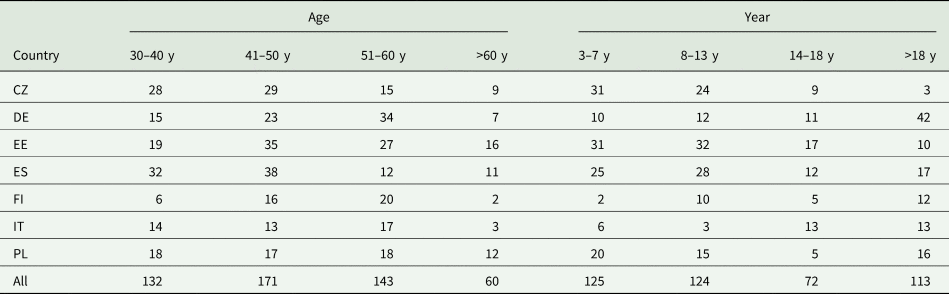

Table 2. Respondents' ages and years in the organic sector for each country

Country: CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; EE, Estonia; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; IT, Italy; PL, Poland.

The most represented groups in the survey (as well as in the real-world scenario) were farmers and processors, while the least represented groups were importers/exporters, certifiers and representatives of the public services (Table 1). Data in Table 2 indicate that most of the respondents in all the countries were in the 41–60 age category, and the smallest group in the 60 and over age category. There were big differences in the years worked in the organic agricultural sector among the individual countries [this corresponds to years of membership in the European Union (EU)], but altogether, most of the stakeholders were active for 3–13 years. One important consequence was earlier access to EU subsidies for the older EU-member states.

The survey focused on the most interesting findings presented in five groups of thematic points: (1) degree of graduate for optional employment, (2) profile of disciplines of graduates, (3) strategies for recruitment of graduates, (4) skills requirement and (5) teaching innovations.

Statistical analysis

All data in the dataset were distributed within a scoring system, ranking from 1 to 5 (‘undesirable / disagree’ by scores 1 and 2; ‘no opinion’ by score 3; ‘desirable / agree’ by scores 4 and 5). Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVAs were applied using the Minitab17© statistical software. Means were compared with the Dunn-Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Evaluations were carried out by clustering whole questions of the dataset: (a) per thematic point, (b) per partner country and (c) per stakeholder. Stakeholders were categorized as (1) farmers, (2) processors, (3) salesmen, (4) import/export representatives, (5) consultants, (6) certifiers, (7) public service representatives and (8) educators.

It is important to underline that all Figures 1–5 are prepared for the whole dataset of stakeholders' answers (700) in all countries. Tables 3–7 present detailed information (see the Results section).

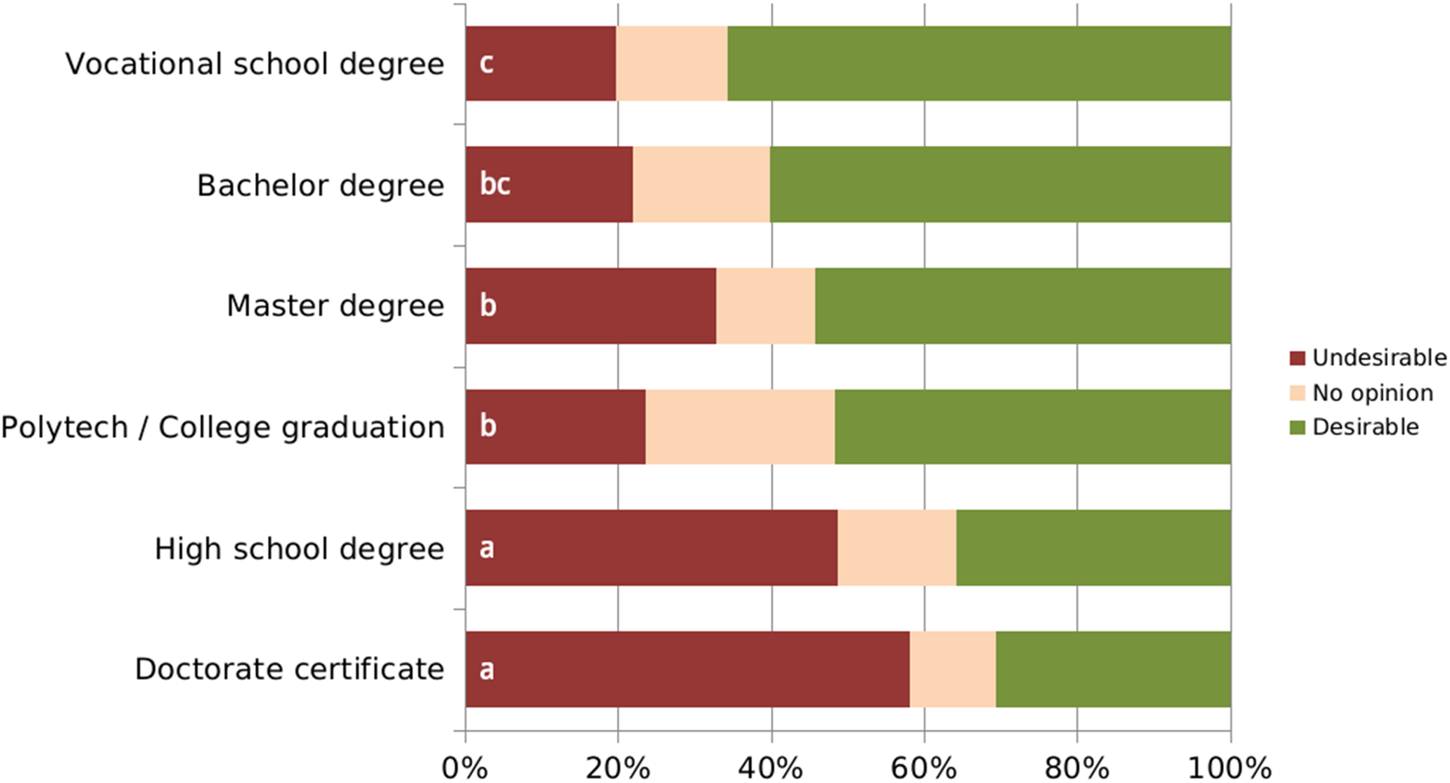

Fig. 1. Preferred degrees of graduates for employment (all stakeholders together).

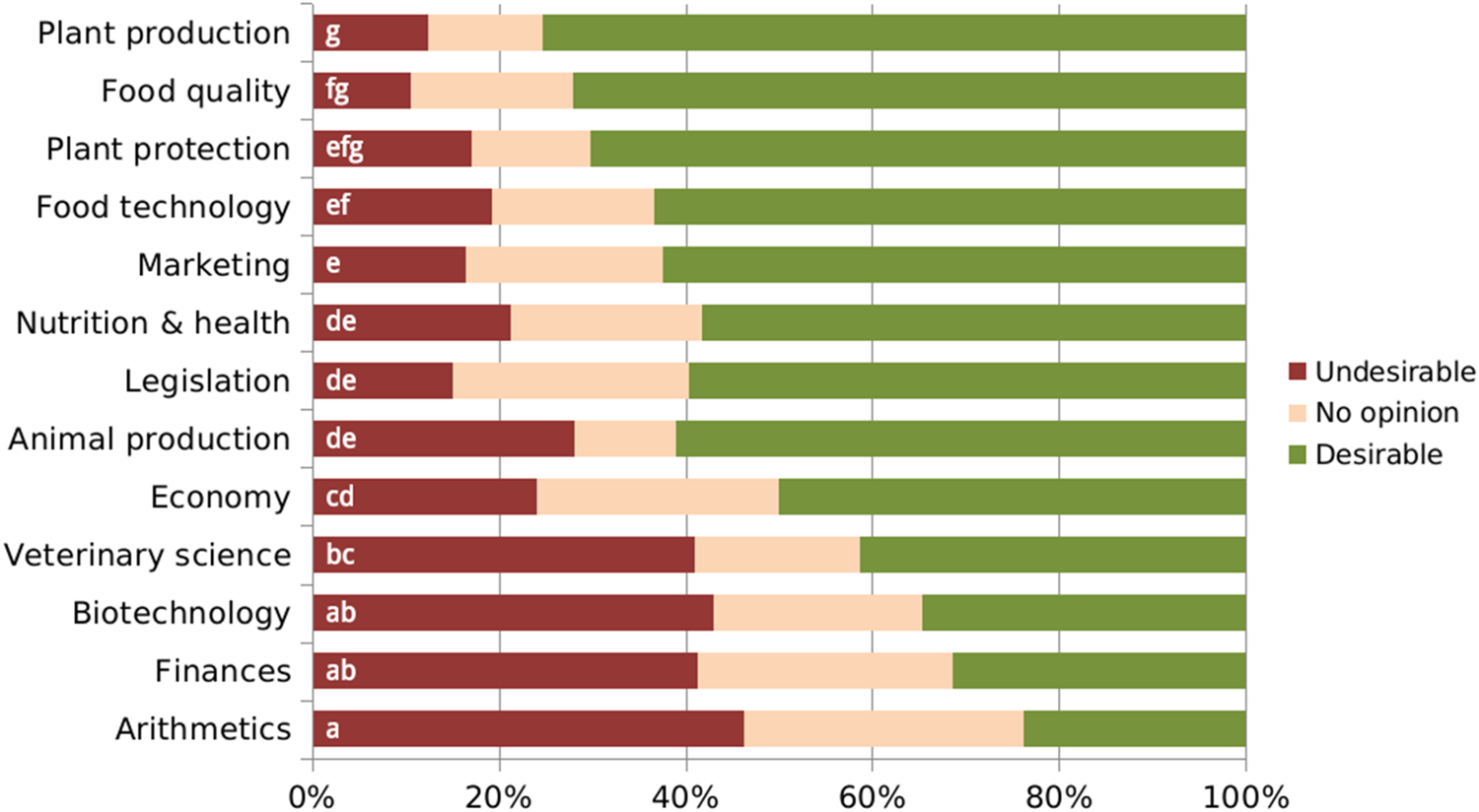

Fig. 2. Desirable discipline-profiles of graduates for employment (all stakeholders together).

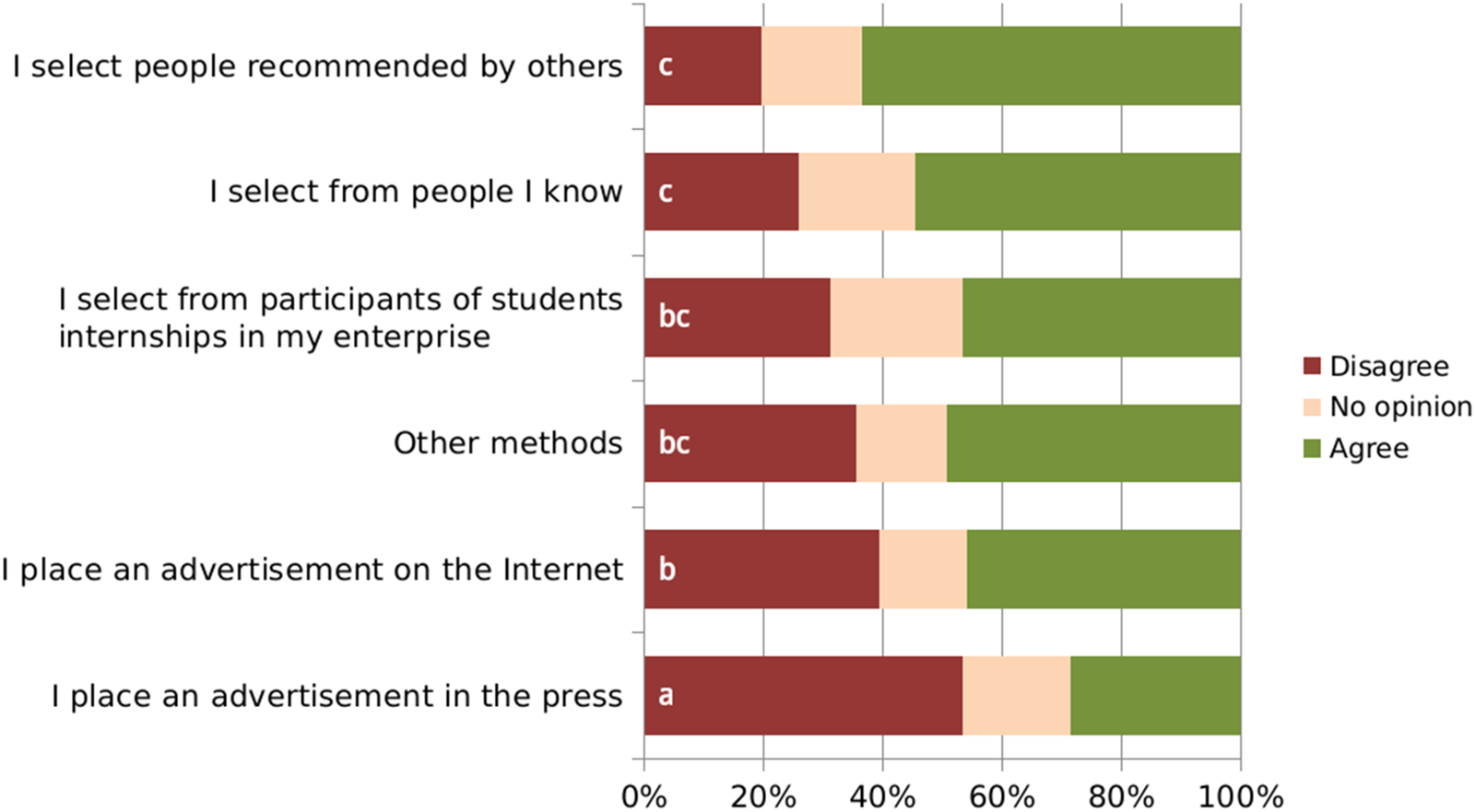

Fig. 3. Strategies of recruitment for employment of graduates (all stakeholders together).

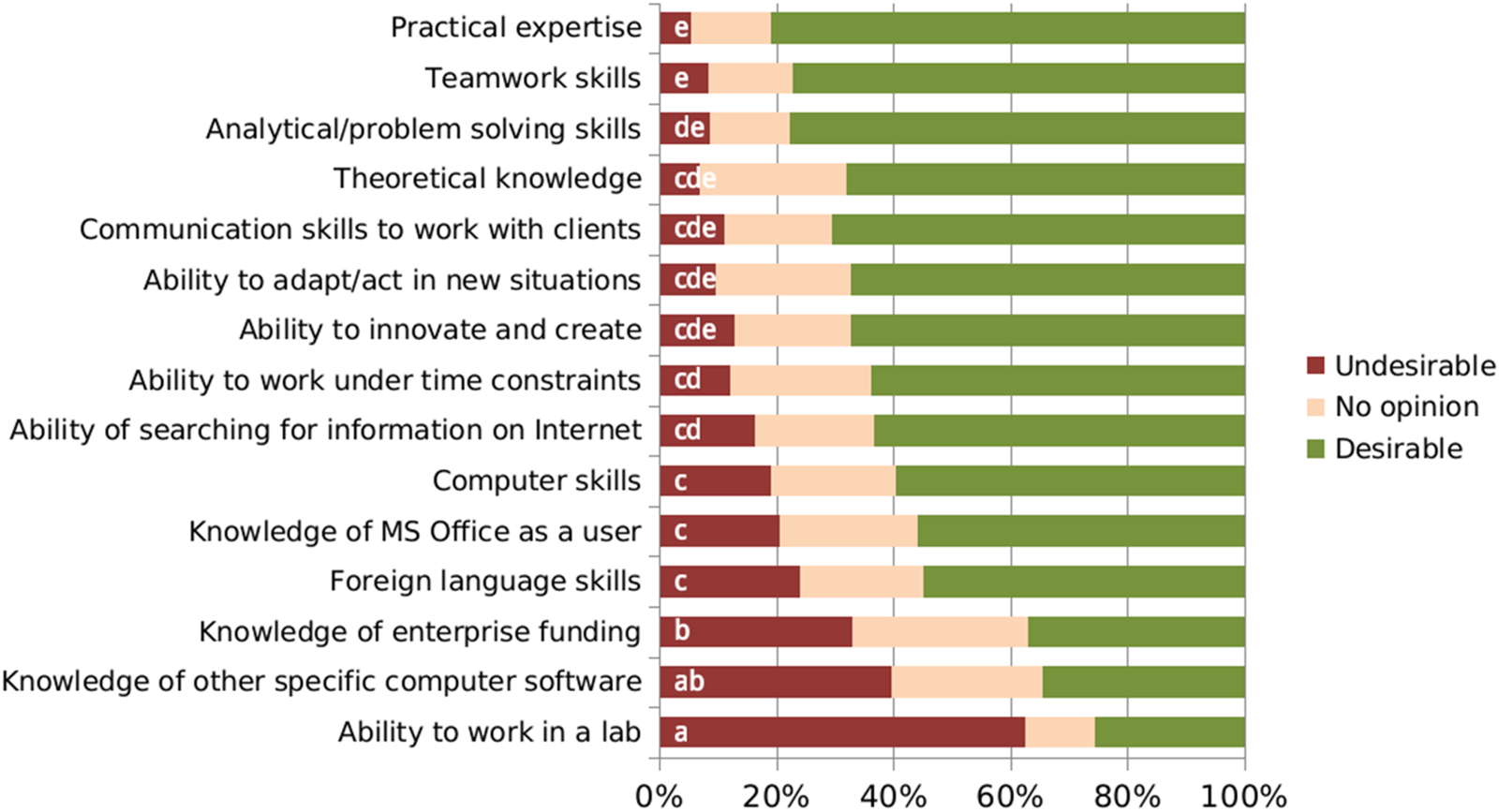

Fig. 4. Desirability of skills of graduates by potential employers (all stakeholders together).

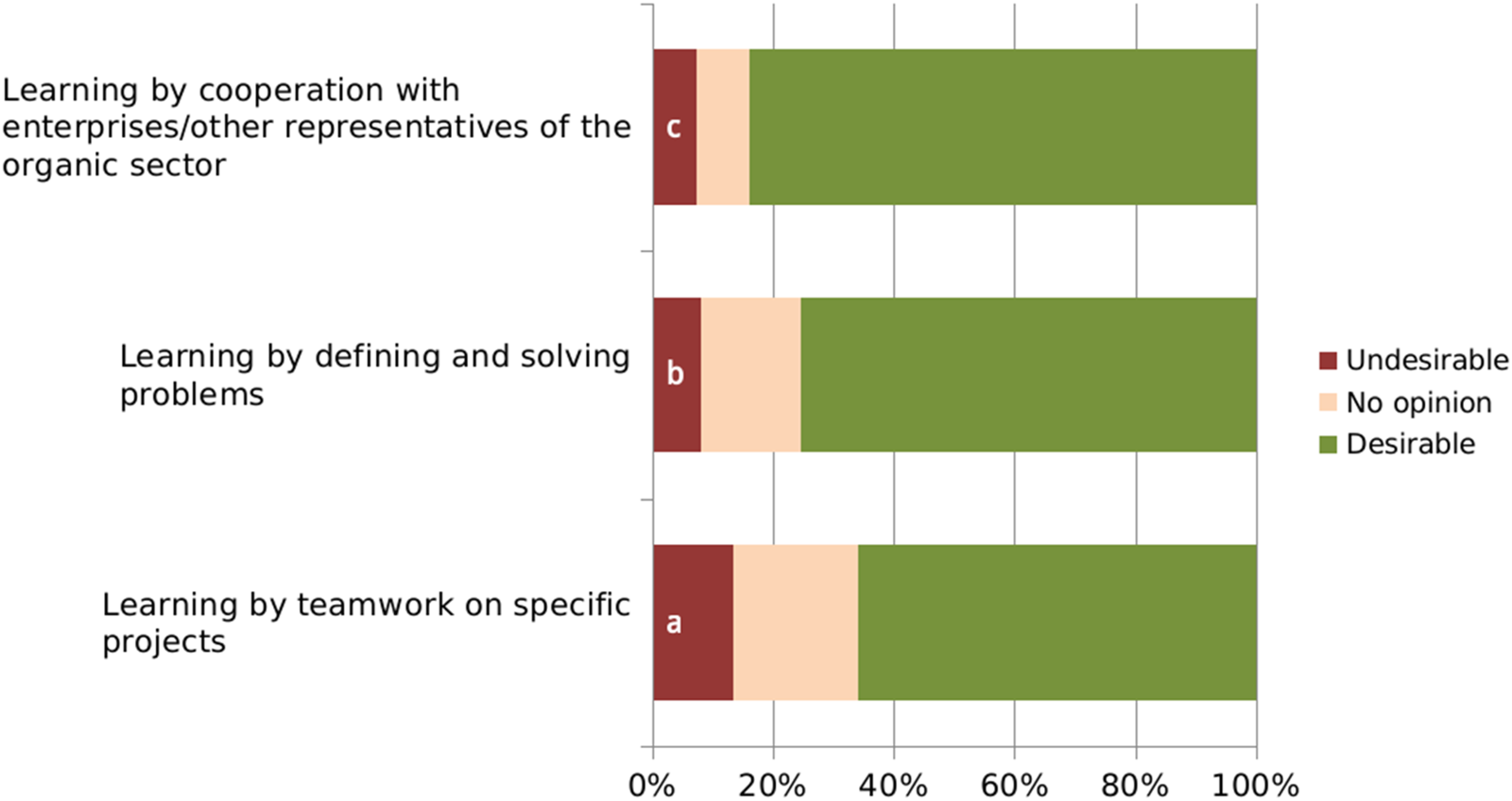

Fig. 5. Approach to innovation in teaching (all stakeholders together).

It is also important to say that the statistical tools used allowed us to overcome the problem of the uneven number of responses from different stakeholder groups. The N per variant or minimum/maximum per variant group is included in the tables and figures. There are no weaknesses due to under-sized groups.

Results

Type of graduate

We were interested in studying the ‘type of graduate’ preferred by the different stakeholders of the organic sector for optimal employment. The possible answers to this question were six fixed replies: three for academic degrees and three for non-academic degrees. The ranking of estimates of the six replies over all country data is presented in Figure 1. Our results showed that stakeholders generally preferred to hire employees with vocational school and bachelor degrees rather than PhD degrees (Fig. 1). Generally, the least preferred employees were the ones with PhD degrees, as there were statistically significant differences between the PhD degree and all other degrees.

The preferred degrees for stakeholders employing graduates in the organic sector are presented in Table 3. The PhD degree was the most desirable by educators and public sector representatives, and the least desirable by salesmen, farmers and processors. The vocational school degree was the most desirable by farmers, processors and salesmen, and least desirable by certifiers and educators.

Table 3. Desirability of selected educational degrees of graduates for different stakeholders

P084: Doctorate degree; P080: Vocational school degree.

EDUC, Educators; PUBL, Public services; CERT, Certifiers; CONS, Consultants; IMEX, Import/Export; SALE, Salesmen; FARM, Farmers; PROC, Processors.

Profile of discipline of graduates

In line with the type of graduate preferred, we delved into the subject of the theoretical knowledge expected from graduates. Results of the survey for all stakeholders from all countries clearly showed a preference for the disciplines of plant production, plant protection and animal production on the production side; food quality and food technology on the food system side and marketing and legislation on the economics and juridical sides (Fig. 2). The least desirable graduate discipline-profiles were arithmetic, biotechnology and finances. Again, due to the distinctly different needs of the various stakeholders, there were clear differences within the answers for the same topics (Table 4).

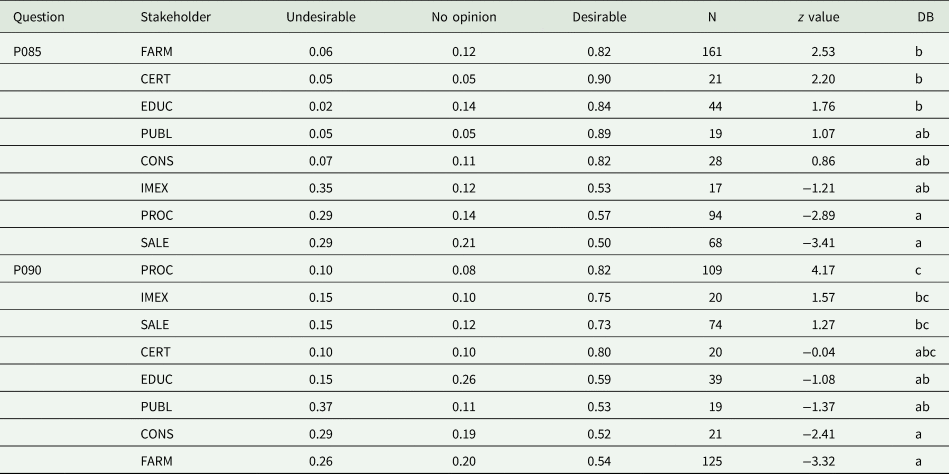

Table 4. Desirability of selected knowledge areas of graduates for different stakeholders

P085: Plant production; P090: Food technology.

CERT, Certifiers; CONS, Consultants; EDUC, Educators; FARM, Farmers; IMEX, Import/Export; PROC, Processors; PUBL, Public service; SALE, Salesmen.

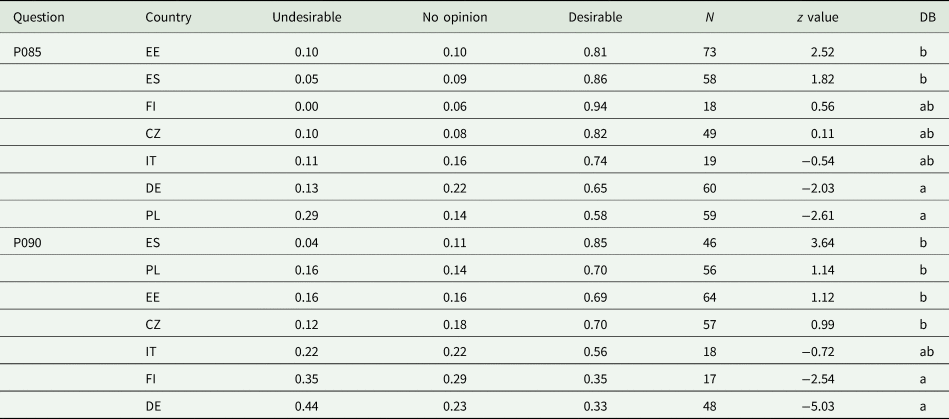

Knowledge in plant production receives a high score from farmers, certifiers and educators (level of agreement, 82–90% desirable), results which significantly differ from those of processors and salesmen (level of agreement, 50–57% desirable and 29% undesirable). Food technology receives a high score from processors, importers/exporters and salesmen (level of agreement, 82 and 73%, respectively). By contrast, only 52–54% of consultants and farmers desire the same background; differences between these two groups of stakeholders are significant (Table 4). Also, there are significant distinctions between the replies of the stakeholders from various countries (Table 5). For example, plant production is significantly more desired by stakeholders from Estonia and Spain (81 and 86%, respectively) than by stakeholders from Germany and Poland (65 and 58%, respectively).

Table 5. Desirability of selected knowledge areas of graduates in different countries (for all stakeholders together)

P085: Plant production; P090: Food technology.

CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; EE, Estonia; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; IT, Italy; PL, Poland.

Strategies for recruitment

The question of how new employees are recruited was posed to the different stakeholders, with six possible answers provided: recommendations, people known by recruiter, internships (training), other methods, advertisements on Internet and advertisements in print media (Fig. 3). The results show that the stakeholders prefer to follow an informal recruitment channel (recommendations, people known by recruiter), rather than formal channels (advertisements on Internet or in print media). The difference between informal and formal recruitment channels is significant.

Skills requirements

Desirability of different skill requirements by graduates for the stakeholders is presented in Figure 4. Analysing all the skills together shows that the most desirable skills are practical expertise, teamwork and analytical/problem solving.

Table 6 also presents details regarding the desirability of different skills by stakeholders. Generally, all skills together are most desired by consultants (75%). This result is understandable because consultants need higher knowledge and skills in their profession.

Table 6. Desirability of knowledge areas/skills of graduates for stakeholders (treated separately and whole group)

P107: Theoretical knowledge; P108: Practical expertise; P109: Ability to work in a lab; P110: Computer skills; P111: Knowledge of MS Office as a user; P112: Ability to search information on Internet; P113: Knowledge of specific computer software; P114: Communication skills to work with clients; P115: Teamwork skills; P116: Analytical/problem-solving skills; P117: Foreign language skills; P118: Ability to adapt/act in new situations; P119: Ability to work within time constraints; P120: Ability to innovate and create; P121: Knowledge of enterprise funding.

CERT, Certifiers; CONS, Consultants; EDUC, Educators; FARM, Farmers; IMEX, Import/Export; PROC, Processors; PUBL, Public service; SALE, Salesmen; CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; EE, Estonia; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; IT, Italy; PL, Poland.

Table 6 also illustrates the desirability of the graduates' knowledge and skills for in particular countries. Finnish and Estonian stakeholders were the most interested in the knowledge and skills of the graduates, while Italian, German and Polish stakeholders were the least interested. The difference was statistically significant.

Teaching methods

The last part of the survey is illustrated in Figure 5. In the opinion of all stakeholders together, the most desired innovation in academic teaching is learning by cooperation with enterprises (>81%), followed by learning by defining and solving problems (>75%) and learning by teamwork on specific projects (>60%).

Table 7 shows detailed information regarding the approach to innovations in teaching graduates. Consultants and certifiers are the most interested in teaching innovations (84 and 86%, respectively), while farmers and processors are the least interested (71 and 72%, respectively). Again, this is in line with the previous results because consultants and certifiers are directly interested in the modern skills of graduates.

Table 7. Approach to innovations in teaching (1) common ranking by different stakeholders and (2) common ranking by individual countries

P127: Learning by defining and solving problems; P128: Learning by teamwork on specific projects; P129: Learning by cooperation with enterprises/other representatives of the organic sector.

CERT, Certifiers; CONS, Consultants; EDUC, Educators; FARM, Farmers; IMEX, Import/Export; PROC, Processors; PUBL, Public service; SALE, Salesmen; CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; EE, Estonia; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; IT, Italy; PL, Poland.

Examining the country-specific data, Italian and Czech stakeholders are slightly more interested in the teaching innovations than their colleagues from other countries, but the differences are not significant. The least interested in teaching innovations are surprisingly the German stakeholders. In general, all stakeholders indicated a high preference (agreement-level >70%) toward new teaching approaches (i.e., problem-solving, teamwork and practice-based strategies).

Discussion

The literature research indicates that the topic of employers' (stakeholders) demand for better qualified graduates within the organic sector is new, and the present study is one of the first to analyze this issue.

The present study shows that the most attractive degree for stakeholders is vocational education, followed by BSc, MSc and PhD studies. The result that employees with PhD degrees are not preferred by stakeholders is not surprising in the context of the practical professions offered by the organic agriculture industry. We have to consider the positions of the stakeholders (Table 1), which clearly differentiate between those more focused on personnel with practical skills (farmers, processors and salesmen) and those more focused on personnel with theoretical knowledge (educators and public service).

The type of education degree can have a strong influence on how graduates perceive agriculture (as one total component or groups of individual components). Both the general and specific approaches can be very productive in scientific terms. The first by the implementation and derivation of practical rules, and the second by gaining understanding in some of the basic processes involved. The distinction between the two approaches has its counterpart in education and training (Porceddu and Rabbinge, Reference Porceddu and Rabbinge1997).

Different studies report higher values for labor in the organic sector than in the conventional sector (Offermann and Nieber, Reference Offermann and Nieber2000), in addition to greater demand for employees, thus helping to reverse the decline in the agricultural labor force, which has fallen in the last decades (Green and Maynard, Reference Green and Maynard2006). Agricultural employment has decreased by 2% per year during the last 25 years, although the number of EU agricultural employment still exceeds 5% (Porceddu and Rabbinge, Reference Porceddu and Rabbinge1997). The effect of education on agriculture professionals shows that studies incorporating organic agriculture has a positive influence for adopting environmentally friendly practices (Padel, Reference Padel2001; Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2008; Kallas et al., Reference Kallas, Serra and Gil2010), and that better educated, as well as younger, professionals are more likely to adopt the organic farming certification (Aubert and Enjolras, Reference Aubert and Enjolras2017). Data suggest that formal education has a positive influence on students' perception of the benefits of organic agriculture (Nunez et al., Reference Nunez, Kovaleski and Darnell2014), with organic agriculture classes increasingly being offered (Hilimire and McLaughlin, Reference Hilimire and McLaughlin2015). More students are interested in Alternative food systems, with a strong accent on organic methods. Students are also interested in related subjects, such as health, environmental sustainability, accessibility and social justice. Even so, Williams and Wise (Reference Williams and Wise1997) discovered that despite high school students being positive about the potential impel of sustainable agriculture, they do not fully understand how sustainable agriculture components fit together and relate to social goals such as quality water, safe food and preservation of natural resources. There needs to be better development of teaching and learning initiatives for sustainable (organic) agriculture in schools for students majoring in agriculture.

Taking into account the fact that the organic market growth is increasing, stakeholders are interested in topics clearly connected to practical needs such as plant production, plant protection and animal production, as well as topics related to food quality and marketing. Stakeholders are aware of the importance of the future of green marketing and its potential effect on the agricultural industry (Byrla, Reference Byrla2015).

Regarding strategies for recruitment, we found that organic agriculture stakeholders significantly prefer informal routes. There has always been a distinction between the formal (advertisements, job agencies, etc.) and informal (word-of-mouth methods, social connections, etc.) recruitment methods. Informal recruitment methods are often used for screening new personnel in many types of jobs (Flap and Boxman, Reference Flap, Boxman, Lin, Cook and Burt2001; Marsden and Gorman, Reference Marsden, Gorman, Berg and Kalleberg2001; Breaugh, Reference Breaugh2013) because they provide more accurate information about prospective employees (Gërxhani and Koster, Reference Gërxhani and Koster2015). The use of informal recruitment methods has additional advantages besides the obvious speed and cost of the process (Watson, Reference Watson and Sisson1989; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Marchington, Earnshaw and Taylor1999).

One of the major issues of recruitment is knowing what makes graduates employable. Results from our study show that for stakeholders (employers), the most attractive skills are practical expertise, teamwork and problem solving skills, while the least attractive skills are working in a lab, knowledge in specific computer software and expertise in financial issues. Previous studies have shown that small firms have problems in attracting the staff they need, often due to low salaries (Atkinson and Storey, Reference Atkinson, Storey, Atkinson and Storey1994) and the lack of basic skills, especially among younger workers (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Marchington, Earnshaw and Taylor1999). Kunkel et al. (Reference Kunkel, Skaggs and Maw1996) posit that ‘the most important step in implementing the needed fundamental changes in higher education in agriculture and natural resources is to gain a perceptive understanding of the society and the industries for which our graduates must be readied.’ That is why this issue is so relevant and there is a clear need to know the demands of stakeholders (employers). Karsten and Risius (Reference Karsten and Risius2004) report that stakeholders complain about graduates being deficient in skills such as writing, speaking, problem solving, data collection and learning on their own. Moreover, stakeholders report that graduates have low awareness of environmental issues, and different cultures and attitudes. According to our study, highly desired skills are analytical/problem solving expertise and ability to adapt/act in new situations. A study by Gil et al. (Reference Gil, Garcia-Alcaraz and Mataveli2015) confirms these findings, adding that additional training is needed to improve employees' competencies (i.e., the ability to act in new situations is an important basic skill).

Humburg et al. (Reference Humburg, van der Velden and Verhagen2013) state that professional expertise is the most important skill set that affects graduates' employability. Other important skills are interpersonal skills, relevant work experience, innovative/creative skills and commercial/entrepreneurial skills. There is high interest in the practical skills and internship experience.

Regarding teaching methods, our results clearly indicate that innovations in the teaching/learning process are necessary within organic agricultural education. The order of preference by stakeholders is learning by cooperation with enterprises/other representatives of the organic sector, learning by defining and solving problems and learning by teamwork on specific projects (Fig. 5).

The conclusions reached in the study by Butun et al. (Reference Butun, Erkin and Altintas2008) are relevant for the present study. The authors find the problem-based learning approach is an effective method to cope with stakeholders' (employers) demands, especially the ability to find and filter proper information, to work both independently and as part of a team, to acquire new knowledge and to take the initiative. Achieving these professional skills requires good social skills and learning abilities. Hilimire (Reference Hilimire2016) finds that effective approaches include emphasizing interdisciplinary skills while balancing experience, theory and practical skills acquisition. Penttinen et al. (Reference Penttinen, Skaniakos and Lairio2013) state that all didactic practices should aim at paralleling the holistic construction of students' careers with their well-being to facilitate students' transition from university to working life. Hilimire et al. (Reference Hilimire, Gillon, McLaughlin, Dowd-Uribe and Monsen2014) find that neither traditional nor non-traditional agricultural education programs explicitly address food systems from a global, structural and sociocultural perspective. Hilimire (Reference Hilimire2016) further finds that students participating in these courses develop deep critical thinking skills around value-based difficult issues to solve complicated food systems problems. The need to combine a study program with internships or training in companies can be the key to successful employment (Karsten and Risius, Reference Karsten and Risius2004).

In summary, professional agricultural educators need to think strategically about what needs to be accomplished to prepare the human resources required for feeding the world's population and protecting the environment and, where necessary, be prepared to shed traditions that constrain the profession. Making improvements in the quality of higher agricultural education worldwide will depend on a variety of interrelated changes. Some changes will require efforts at the individual institutional level while others will require global cooperation (Acker, Reference Acker1999).

Conclusions

We have evaluated at the European scale the needs of the job market of different stakeholders, and can offer some new findings relevant for future educational activities within organic agriculture. There is a clear willingness to employ graduates in organic agriculture, which is crucial for both the education system and the sector; however, there is no common agreement in the level of studies (varying from vocational education to doctorate studies) to best achieve this. From the stakeholders' (employers) point of view, the most desirable knowledge among graduates of organic agricultural studies is plant production, food quality and plant protection, while the most desired skills are practical expertise, teamwork and problem solving skills. We can conclude that stakeholders are not satisfied with the level of knowledge of the current graduates, and point out that traditional teaching methods may not be the most adequate ones. Teaching methods should be adapted to the needs of the stakeholders (employers) and innovative tools are necessary. It is important to increase cooperation with companies or other representatives of the organic sector, and to learn by defining and solving problems in order to have a broader understanding of the situation. This can be a challenge for current study programs of all levels across Europe, but we think it is the starting point to ensure a successful organic sector which, year after year, is increasing its presence all over the world.

Acknowledgements

This study has been carried out within the project ‘Innovative Education towards the Needs of the Organic Sector’, acronym EPOS, no. 2014-1-PL1-KA203-003392, funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union. This publication reflects only the authors' views. The European Commission and Erasmus+ National Agency are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.