Following its rise to power in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) identified “the core task of the party's work concerning women” as “mobilizing women to participate in socialist construction on all fronts.”Footnote 1 Under the new regime, the overall trend of women joining the workforce meant that female employment rapidly increased. From 1949 to 1960, the number of non-agricultural and non-domestic women workers skyrocketed from 600,000 to over 8 million.Footnote 2

A major boost to female employment occurred in 1958–1960 when the government launched multiple campaigns under the Great Leap Forward (GLF) banner. A major theme of the campaigns was “liberating women's labour power.” In cities, women were organized into various small neighbourhood workshops for manufacturing, recycling and other services. By April 1960, there were an estimated 3.75 to 4 million women employed in such workshops, in addition to the 8.25 million “regular” women workers and employees.Footnote 3 In other words, women workers in neighbourhood industry accounted for about one-third of non-agricultural female employment in the country.

Although a product of the GLF, the institution of neighbourhood industry survived and prospered for decades after the GLF had failed. Occupying the lowest rung of China's urban employment hierarchy, these neighbourhood workshops employed millions of women. For most, a position in the workshop was their very first job outside the home. Women who performed well assumed leadership positions and ended up practically running the workshops; indeed, the workshops came to be characterized as a niangzijun 娘子军 (“women's army”), a witty term referring to an all-female military contingent.Footnote 4

The GLF is seen as a major catastrophe, and justifiably so.Footnote 5 The famines that claimed tens of millions of lives during this period were indisputably a terrible result of Mao Zedong's 毛泽东 policy and even the CCP has acknowledged that the campaign was one of the key mistakes made by the Party during the Mao era.Footnote 6 Yet, as far as women's employment is concerned, the GLF mobilized millions of women to take up work outside the home and established an irreversible trend of female employment in China's cities. There is unanimous agreement in China that it was the GLF, or simply “the year 1958,” that gave rise to the new norm in urban China that practically all working-age women should work outside the home.Footnote 7 By the end of the Mao era, there were about 20 million women working in manufacturing, of which 8.48 million (or 42 per cent) were employed in “collectives” that were largely developed from urban neighbourhood industry.Footnote 8

This article takes Shanghai as a case study to examine this type of employment for women in China. As the nation's largest city, Shanghai was at the forefront of China's neighbourhood industry both in terms of the number of women who were employed in the sector and the way in which it operated. From 1958 to 1960, the city had created 738,000 new jobs, of which 439,000, or about 60 per cent, were performed by women.Footnote 9 By 1960, female employees in Shanghai numbered 665,000, a more than a 12-fold increase since 1952; of these, about 140,000, or more than one-fifth of the city's total female employees, were working in neighbourhood workshops.Footnote 10 These workplaces were operated by China's three-layer neighbourhood organizations, which were introduced in the early 1950s. Shanghai was one of the first cities to establish this system. By the time the GLF was launched, neighbourhood organizations had already become a fully functioning grassroots apparatus for governing the city's 6 million residents. Neighbour organizations played a pivotal role in setting up neighbourhood workshops, referred to as “alleyway production teams” (lilong shengchangzu 里弄生产组, APTs hereafter), in the city's 11,000 alleyways. Over the following 20 years, APTs became synonymous with urban neighbourhood workshops throughout the country.Footnote 11 There is, arguably, no better city for studying China's neighbourhood workshops than Shanghai.

China under Mao was a highly ideologically driven nation. Based on the Marxist belief that women could not realize their productive potential unless they were freed from the drudgery of household labour, the Party believed that women joining the workforce in “socialist construction” was a prerequisite for their liberation.Footnote 12 Behind this rhetoric, as we will see, was a sober calculation by the state to employ women in low-paid jobs, with no fringe benefits, in order to supplement state-run industries. As Harriet Evans has pointed out, “The new communist government's policies on gender equality and female employment were fundamentally motivated by economic interests.”Footnote 13 Unskilled women workers (fei jishu nügong 非技术女工) were regarded as a type of labour reservoir that was available in times of need but with no maintenance cost to the state.Footnote 14

Nonetheless, the story of China's urban neighbourhood workshops is not simply one of the exploitation of cheap labour. Women were not entirely passive in the process. They exploited the Party's own slogans to legitimize their drive for financial independence, social status and self-esteem. Yet, again, what was involved was not a simple dichotomy between exploitation and empowerment, nor a confrontation between state and labour. Rather, the state and the workers had a shared common ground that made it possible to accommodate each other's interests. To be sure, in the communist system the state remained the dominating force, but this did not preclude women workers at the grassroots from actively pursuing their own interests.

The Rise of Neighbourhood Workshops

Neighbourhood organizations were one of the major institutions established by the CCP after it took power. They were responsible for watching over every household and providing some community services. From the bottom up, the structure was (and still is) made up of three basic layers: residents’ small groups, residents’ committees and street offices.Footnote 15 As defined by the government, these were “self-governing mass organizations”; however, in reality they formed part of the party-state's top-down control mechanism, or the “roots of the state.”Footnote 16 In the communist “partocracy,” these committees constituted the lowest levels of urban administration, with each unit being a subdivision of an organ one step higher up in the bureaucracy. Staff members were appointed from above and were overseen by the CCP branch at each level.Footnote 17

In less than a year after the CCP took control of the city in May 1949, Shanghai had started to set up neighbourhood organizations in every part of the city. By the end of 1954, it had established 1,852 residents’ committees, which supervised more than 36,000 residents’ groups, with a personnel of 95,000 mostly unpaid women cadres.Footnote 18 During the GLF, these neighbourhood organizations were responsible for setting up thousands of small manufacturing workshops and service facilities under the generic name “alleyway production teams” in the city.Footnote 19

In August 1958, Ma Wenrui 马文瑞, the PRC's minister of labour (1954–1966), called for “further liberating women's labour power,” encouraging women, typically housewives between the ages of 25 and 45, to leave their traditional domestic duties in order to join “socialist construction” outside the home.Footnote 20 This call was met with great enthusiasm amid the frenzy of the GLF. Zhangjiazhai 张家宅, a neighbourhood in west Shanghai, founded the city's first ten APTs, which made toys, electrical devices such as lightning arresters, and clothing accessories, within days of Ma's announcement.Footnote 21 In just a few months, 7,667 neighbourhood workshops were established and as many as 299,000 women were employed.Footnote 22

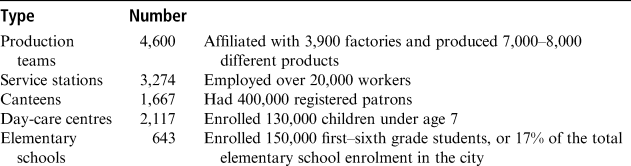

Like many other things that emerged during the GLF, the mobilization and mass participation organized by the government involved not only widespread voluntarism but also excessive haste. The headlong rush to establish neighbourhood workplaces reflected a herd mentality. According to the Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Statistics, at the end of 1959, 11,173 neighbourhood workshops and service units had been established in the city. They employed 139,630 workers, nearly all of whom were women.Footnote 23 Another government survey of these “work units” (see Table 1) stated that in May 1960, Shanghai had 9,983 neighbourhood workshops, which employed 278,000 women, or about 42 per cent of the female employees in the city.Footnote 24

Table 1: Neighbourhood Organization-sponsored Work Units in Shanghai, December 1959

Source: The survey was conducted in March 1960 by the Shanghai Municipal Communist Youth League United Front Office. Zhonggong Shanghai shiwei dangshi yanjiushi 1999, 186.

Notes: According to what the government claimed to be “very incomplete statistics,” in 1960 production teams produced, among other products, 29,740,000 toys, 1,700,000 umbrellas, 97,688,000 cartons, 6,826 straw hats, 3,400,000 woollen sweaters, 3,640,000 pieces of clothing and 5,680,000 scarves. SMA, B123-5-327-11.

This dramatic trend did not last long. The GLF ended in disaster, including widespread famine in 1959–1961. To cope with this crisis, the government reduced investment in industry and called for a reduction in the urban population. Nationwide, tens of millions of urban-based employees were sent to rural and frontier areas. From 1961 to 1962, Shanghai laid off 312,000 employees of state-own enterprises; 183,000 of them were sent to the countryside.Footnote 25 As a result, female employment in Shanghai experienced a major setback.Footnote 26 By the end of 1961, about half of the women who had been employed during the years of the GLF were laid off.Footnote 27

Neighbourhood workshops were not operated on the state budget, so presumably they would not have been affected by the cuts in state funding. However, these workshops had their own vulnerabilities. The downsizing of various industries meant that orders from state-run factories, which were essential to the existence of these workshops, were reduced. Given the informal nature of these work units, it was easy to shut them down. In March 1961, the number of Shanghai's neighbourhood workshops fell to 7,572, with 242,983 workers. More than 6,700 were APTs, which employed 174,054 workers.Footnote 28 From late 1961 to the first half of 1962, neighbourhood workshops underwent mergers, shutdowns and reorganization. As a result, more than half of the workers “went back to the home kitchen.”Footnote 29

Still, even after the widespread job cuts, more than 100,000 women did keep their jobs in the thousands of neighbourhood workshops across Shanghai that survived the GLF. A number of the best-run APTs – 510 in total – were elevated to the category of “street factories” (jiedao gongchang 街道工厂). These were run, depending on their products, by various industrial bureaus that reported directly to the municipal government. These factories were known as “big collectives” (dajiti 大集体) and the level of their employment was next only to state-owned enterprises in China's industrial hierarchy. Their employees received a monthly salary (rather than daily wages) as well as fringe benefits, including medical care and a retirement pension.Footnote 30

The remaining APTs (3,178 in total) were officially categorized as “small collectives” (xiaojiti 小集体). Their employees were paid daily wages, usually 0.60 yuan a day (later increased to 0.70 to 0.90 yuan), and received no fringe benefits except for an annual bonus of about ten yuan, which was distributed before the Chinese New Year.Footnote 31 In comparison, the average monthly pay for all employees in Shanghai in 1962 was 68.41 yuan.Footnote 32

By the end of 1962, APTs employed 86,000 workers citywide.Footnote 33 In the following years, when the economy was recovering, the number of APT employees increased steadily. By 1965, APTs employed 127,000 workers, a 48 per cent increase from 1962.Footnote 34 In fact, these neighbourhood workshops became part of the government's solution for the unemployment problem. For instance, in July 1966 there were 53,000 unemployed youth in the city; 16,000 of them, mostly women, were assigned a job in neighbourhood workshops.Footnote 35 In 1969, after the worst of the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution had subsided, APTs employed more than 190,000 workers. Over 80 per cent of them were described as “toting shopping baskets, tending coal stoves, and taking care of the kids” before joining the workforce.Footnote 36 Overall, after the GLF, it became the norm for women to have a full-time job outside the home, and the decades following the GLF witnessed a remarkable shift towards the near universal employment of women in urban China.Footnote 37

Types and Administration

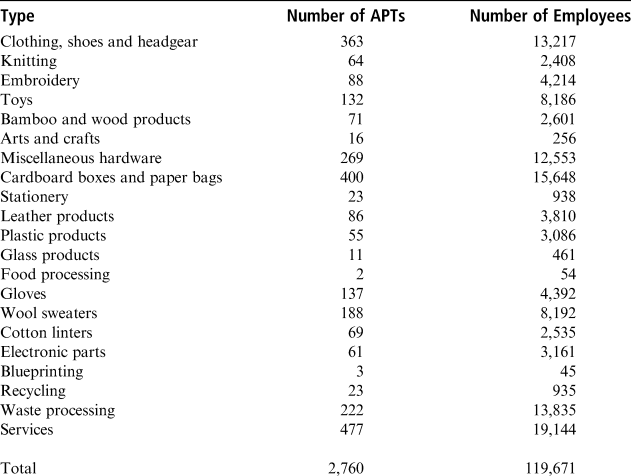

Although all of these workplaces went by the generic name of “alleyway production teams,” they in fact varied widely in the products and services they provided as well as in their organization and role in production. The Shanghai municipal government listed 21 types of APTs, grouped into four categories, based on a citywide survey conducted at the end of 1965. The categories included independent producers (5 per cent), members of a production chain (67 per cent), waste reclamation (12 per cent) and services (16 per cent).Footnote 38

“Independent production” referred to workshops that produced their own merchandise, which consisted mostly of handicraft products such as various types of bamboo ware, embroidery and wooden objects. These workshops were “independent” in the sense that they managed everything on their own, a working model known as zichan zixiao 自产自销, or “production and marketing all by oneself.” For instance, a workshop making bamboo goods was responsible for finding raw materials (i.e. bamboo) in the countryside, shipping it to the city, making the products and marketing them to retail stores. Many of these small workshops were in Nanshi 南市 district, the site of the old Chinese city and a centre of family-run handicraft trades for centuries.Footnote 39 Needless to say, these APTs were not family-run businesses, although they bore some resemblance, and their “independence” reflected a certain level of flexibility permitted by the Party's policymakers, who tended to acknowledge local conditions.Footnote 40

The great majority of APTs formed one part of a bigger production chain. These workshops took purchase orders from larger, state-run factories that outsourced parts and accessories for their products or else subcontracted the assembly of products. Commonly, APTs made or assembled items such as toys, clothing, pillowcases, scarves, shawls, embroidered apparel, shoe uppers, haberdashery (buttons, ribbons, zippers, etc.), cardboard boxes, brown bags, pins, safety pins, metal springs, stationery, school supplies, plastic products, and so on. Some workshops also helped larger factories make high-tech products such as radio parts, electric transformers, electricity meters, coils and various tools (see Table 2).Footnote 41 The synergistic relations between APTs and state-run factories were crucial. The workshops soon became, as the government acknowledged, “an important force to supplement big industries and help many factories and enterprises to fulfil their production plans.”Footnote 42 And, for APTs in this category, the purchase orders from big industries were essential for their survival.

Table 2: Types and Sizes of Alleyway Production Teams (APTs) in Shanghai, 1965

Sources: SMA B158-2-9-66.

“Waste reclamation” referred to the city's numerous waste recycling depots where residents could sell all kinds of household waste for cash. Since China was still a very poor country, every bit of feipin 废品 (scrap or waste material) delivered to recycling depots became source material for some type of industry.Footnote 43 Recyclable paper, such as books, newspapers, magazines and wastepaper, was among the most common items sold, but there were many more. Worn-out shoes, rags, toothpaste tubes, broken light bulbs, fluorescent tubes, glass, used electric wire and used batteries were all recycled. In an age of scarcity, even food waste such as bones, chicken and duck gizzards (an ingredient used in Chinese medicine), and chicken and duck feathers were traded in. Human hair and nails were also traded in – barbershops routinely collected customers’ hair to sell to the depots. By the end of 1959, there were 181 waste reclamation depots in the city.Footnote 44

As for “services,” neighbourhood organizations ran day-care centres, canteens, telephone booths and clinics, as well as what were called “service stations” where people went to pay utility bills and get household goods repaired, clothes mended, laundry washed, and so on. Of these services, day-care centres were particularly relevant to women. China had a high birth rate in the early 1950s of 2 per cent. Between 1950 and 1955, women were on average giving birth to more than six children. The next decade saw a slight decrease in fertility, to 5.61.Footnote 45 It was common in those days for mothers to have several small children at home. Neighbourhood day-care centres were established, initially free of charge, to free up women from childcare duties and encourage them to go out to work.Footnote 46

Each residents’ committee had a clinic manned by one or two so-called barefoot doctors who were also on an APT payroll. These medical personnel typically received a few months of basic training in a district hospital and could treat minor illnesses, such as common colds, or minor abrasions. Periodically, the clinic gave vaccine shots to school children and residents for free as part of government drives. Clinic staff also made local house calls to administer prescription shots at a rate of 0.10 yuan per injection.Footnote 47

The APTs came under the administration of two parallel structures. The street office had a management team that oversaw human resources and general day-to-day operations. Above it, the district's bureau of handicraft industries took care of purchase orders and quality control. From 1973 onwards, as part of the effort to carry out Mao's instruction to ensure a “unified leadership” at all levels of administration, the Party committee of the street office gradually took on the leading role in all things related to APTs and was directly responsible to the district government. However, this change had little effect on the ground, where daily operations were run by a few team leaders appointed by the street office or the neighbourhood committee. Virtually all of the team leaders were women and none of them were on the government payroll; they were, just like their co-workers, daily wage earners.Footnote 48 Few were Party members, the most important emblem of social status in Mao's China. In fact, the Party had a minimal presence in these workplaces. In 1969, at the high point of Maoism, less than 0.1 per cent of APT employees were Party members, the lowest proportion of membership among all types of urban work units in China.Footnote 49 The Party's political neglect of APTs reflected its disregard for these women who worked at the bottom rung of urban employment.

Despite these administrative structures and their large number, the APTs cost the government virtually nothing. In 1968, a decade after the institution was established, the Shanghai municipal government undertook a general review of the workshops. In its report, it outlined four basic APT characteristics: the APTs needed no investment from the state; they had no need for factory buildings or the kind of equipment that a regular factory would require; they were small, dispersed and flexible in their operations; and they used spare or recycled materials to meet the needs of large factories. All of these characteristics were regarded as valuable, but the review made no reference to “liberating women's labour force,” the rationale for creating these workplaces. Clearly, the government looked at the APTs from a self-serving perspective. While it was pleased with what the APTs had accomplished in the preceding decade, instead of rewarding them, it intended to keep them running as a subaltern workforce. The report concluded that “APTs are different from [state-run] factories and enterprises; they should not be detached from urban neighbourhood organizations and take a so-called path to gradual elevation to become full-fledged work units.”Footnote 50 This policy continued for the next ten years.

Meanwhile, these workshops had become not only a solution for unemployment but also a significant source of revenue for the government. Shanghai's toy industry, for instance, exported two-thirds of its output overseas, earning precious foreign currency that China badly needed. APTs made up the great majority of industrial enterprises, and in 1965 alone, made a net profit of US$5.2 million for the government through exports.Footnote 51 In 1972, the total annual output value of APTs reached over 140 million yuan, with more than 20 million yuan held in their collective reserve funds.Footnote 52 While the government assumed no financial responsibility for these enterprises, it raked in a handsome amount of taxes from them. Take, for example, Guangdong Street, a neighbourhood in downtown Shanghai immediately adjacent to Nanjing Road. The 11 workshops in that neighbourhood employed 3,124 workers and, from January 1964 to September 1968, paid 939,700 yuan in taxes. This means that although China at the time did not have an individual income tax, on average each worker paid 300.80 yuan to the state, an amount that exceeded the average annual income of the workers.Footnote 53

Professed Volunteerism

In the beginning, the neighbourhood workshops were established, at least purportedly, in the spirit of volunteerism and women's liberation in the great march to socialism. The principle regarding pay in these workplaces was “centralizing income, rationalizing distribution, promoting the communist spirit, and the principle of distribution according to work.”Footnote 54 Although having an income always helped (more on this later), at first most women were primarily motivated to join the workforce through government mobilization during the GLF. Among ordinary families in Shanghai in the 1950s, it was still customary for the wife to take on the role of homemaker; only about 17 per cent of women were in paid employment.Footnote 55 The idea of working in a neighbourhood workshop was not always welcomed by the women or their families.

Physically, all the workshops were located in residential neighbourhoods, typically in a room or two on the ground floor of an alleyway house. These houses were usually two- to three-story Victorian/Edwardian terraced houses, as were introduced by the British in the late 19th century. About 80 per cent of Shanghainese lived in such houses until the end of the 20th century.Footnote 56 Since the houses shared a common wall, a few adjacent living rooms (typically around 20 square metres each) could be knocked into one to create a workshop floor. Other rooms, such as kitchens and so-called pavilion rooms (a room above the kitchen originally designed as a study or guestroom), were also used for the same purpose.

These premises were mostly offered up by residents, sometimes willingly, out of a sense of duty, but also because of the pressure to be seen as a good citizen of the socialist nation. Families that had an extra room to spare would most likely have been families of former capitalists and well-paid professionals. They were mobilized to surrender their extra space to an APT at a time when the socialist nationalization campaign had just ended. For them, contributing a room to a neighbourhood organization was a way of showing their commitment to the socialist nation.

At the beginning, residents brought basic furniture (chairs, stools, tables, etc.) and simple tools (scissors, rulers, tailor's chalk, etc.) from their homes to the workplace. These contributions often accounted for more than half of the primary equipment of the workshops.Footnote 57 Ma Liying 马丽英 joined a sewing workshop near Nanjing Road and worked there for decades. She recalled her experience:

In 1958, Chairman Mao called for the liberation of women's labour. We all left home cheerfully, without hesitation. At that time, there was nothing to begin with, so we all voluntarily donated. This was called “starting an enterprise from scratch,” with everyone contributing whatever they had. I had just bought a sewing machine for my home, but I donated it to the workshop. I wasn't alone in doing so; many people did the same thing. There was no need to persuade people to contribute.Footnote 58

Treadle sewing machines were expensive (starting at around 150 yuan) but were in much demand, as sewing workshops were among the most common types of APT. Other donations would typically include a few old-fashioned square dining tables (known as a “table of the Eight [Daoist] Immortals” since it can seat eight people) and workers would bring their own stools to the workshop.

In the more affluent neighbourhoods, the garages of private homes or apartment buildings were commonly turned over to APTs. Since private automobiles had been almost entirely eliminated from the city after 1949, most of these garages were unused; by removing the interior walls, they could be turned into sizable workshops. Various types of workshop sheds were also built at the entrances to alleyways, cul-de-sacs or detached houses. These were meant for temporary use and were not authorized by the district's bureau of housing and real estate, which was responsible for issuing all title deeds in the area. Nevertheless, the legal status of these structures was uncertain since they were built by the neighbourhood organization for APTs and often remained standing for decades. Frequently, the housing bureau accepted these buildings as they stood and would either provide a title deed retrospectively or else categorize the structure as an “unauthorized construction” but do nothing about it.Footnote 59 In addition, some of the air-raid shelters that were constructed in the early 1970s as part of China's preparations for a possible war with the “Soviet social imperialists” were used to house APTs. By the end of the Mao era in 1976, APTs in Shanghai had a total floor space of well over 8 million square feet and were dotted all over the city.Footnote 60 Nevertheless, since these workshops were all located away from the main streets among residential homes, casual visitors to the city rarely noticed them.

The Politics of Downsizing

The spirit of volunteerism and women's liberation that supposedly served as the foundation of the neighbourhood workshop was fragile. Moral suasion, socialist devotion and Party propaganda during the GLF did boost morale and get the ball rolling, but ultimately it was pragmatism and utilitarian calculations of both the Party cadres and the women workers on the ground that sustained the system. The politics involving the 1960–1961 downsizing and reorganization of the neighbourhood workshops illustrates this point.

The reactions to the redundancies involved in this downsizing varied. Overall, workers complied, with little resistance. Many women workers had not considered their job to be a serious form of employment to begin with and so being discharged was not particularly upsetting. Women in financially better-off families even felt relieved, since they had joined the workforce only because the government had called for it; now they could go back to a more relaxed lifestyle with their families and not worry about being seen by the authorities as politically backward or uncooperative.Footnote 61

However, there were disgruntled employees who confronted residents’ committee cadres and some workers who felt strongly that they had been mistreated. One woman openly and frankly expressed her feelings to the neighbourhood committee:

You mobilized us to go to work, you told us the factory wouldn't close, you said there was enough work for all us, and you said we shouldn't depend on our backstage boss [i.e. husband] for a living – why do you now ask us to return home?Footnote 62

Some discharged workers went further by showing up at the workshop daily as if they had not been laid off, demanding to be paid out of the APT's collective reserve fund which was designated for emergencies. Such protests by women who desperately needed a job were understandable, yet the authorities were not sympathetic. The government wanted to limit the number of workers on the payroll and saw these complaints as an emerging demand among these workers for the government to take care of them. “The fact that some housewives who entered factories now should be dismissed but do not want to leave is in fact asking for the government to take care of them,” one government report stated. “It is a demand that the state take care of the collectives and the collectives take care of the individual.”Footnote 63 In the following years, the government frequently emphasized that APTs should remain under the administration of neighbourhood organizations, that is, they should not in any way come under the government's budget.

Such a utilitarian approach to female labour contrasted sharply with the Party's proclaimed principle of gender equality. This, however, should not come as a surprise. Just a few months before the launch of the GLF, with its huge demand for labour and consequent campaign to “liberate women's labour power,” the Party indeed recognized that housework is a type of “social work” and asked women to be content with being homemakers. In early 1958, top government officials publicly declared that “it is glorious [for women] to take care of household duties and hence the Party's call for being industrious and thrifty in managing one's household can be carried out by actual actions” and that “doing housework is a way to support husbands and [adult] children in their workplaces, therefore it too is a contribution to the revolution.”Footnote 64 On International Women's Day of that year, the People's Daily carried an editorial suggesting that it would be more beneficial to the state if some women cadres retired and returned to taking care of their children so the government could avoid paying for childcare. It instructed the women that, “for the sake of the state, it would be better [for you] to resign and return home and attend to the housework.”Footnote 65 Just four months later, however, Minister Ma totally changed the tone. In an article published in Laodong 劳动, the Ministry of Labour's mouthpiece, he called for “further liberating women's labour power.” This unleashed a frenzy of exhortations for women to work outside the home.Footnote 66 The swing of the pendulum seemed to be dramatic, but the forces at work indeed remained the same, that is, the Party saw women as a secondary reservoir of labour to be used at its convenience.Footnote 67 China scholars have applied the concept of adaptive governance to explain the resilience of the regime after Tiananmen.Footnote 68 The CCP's adaptive governance, one may add, can also include rapid ideological fluctuations, justified by rationalizations in the vein of “Mussolini is always right” and an overweening sense of self-righteousness.

With regard to the layoffs, in determining who could stay – a decision left to street office and neighbourhood committee cadres – women in their early 30s to early 40s had priority. The rationale for favouring this age cohort was that older women “have a lot of household chores to do, they are physically weaker, get tired easily,” and some of them had bound feet. “It would be bad,” one internally circulated report claimed, “to let foreign visitors see women with bound feet working in a factory.” Younger women, on the other hand, were an unsettling force in the workshops, as they usually wanted to work for state-run or “big collective” factories; some of the more determined ones even wanted to apply for college.Footnote 69 In the minds of the cadres, a sort of culinary technique could, metaphorically, apply in this situation: cutting off the two ends of a cucumber would leave the best part, the centre.Footnote 70

There were also detailed deliberations among cadres on the benefits of hiring middle-aged women. First, they were nearly all married and so had a husband with a regular job. Since the family did not necessarily depend on the wife's income to make ends meet, they were usually content with the meagre income that came with workshop jobs. Second, married women tended to be stable. Most had a family to take care of and did not have any ambitions to move on to a state job. Third, these women were in good health and could do physically demanding work, such as pulling a four-wheel delivery cart (locally known as “yellow croaker carts,” huangyuche 黄鱼车 in Chinese, as they were often used for transporting fish), a common way of moving goods in the city. This kind of work was often needed in neighbourhood workshops, but older women were unable to do it and younger women were unwilling to do it. Finally, women in this age bracket typically had some schooling, which, it was argued, tended to make them fast learners.Footnote 71 Clearly, these cadres’ calculations were hard-headed and differed little from the thinking of employers in a capitalist society; they had nothing to do with “women's liberation.”

On Their Own Terms

Why, despite all the disadvantages, did hundreds of thousands of women in Shanghai (and millions of women elsewhere in urban China) work in neighbourhood workshops? The simple answer is that since these women were poorly educated and largely unskilled (see Table 3), the job market did not offer them many choices. This explanation is by and large true but far from complete. Women had political and economic motives, as well as certain lifestyle concerns, for working in neighbourhood workshops. In other words, when it came to the question of employment outside the home, these women were not entirely passive. Many worked in the same APT unit for years, seemingly satisfied with their work life. There were several reasons for their satisfaction.

Table 3: Level of Education among 115,324 New Women Factory Workers in Shanghai, 1958

Source: Shanghai funüzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 2000, 5:1:2.

Notes: The level of education refers to the highest level of school that a worker attended but not necessarily completed.

Politically, despite being at the bottom of China's urban employment hierarchy, working for an APT meant a woman worker had a work unit (danwei 单位), which was “the locus of an individual's identity in urban China.”Footnote 72 In such a milieu, APT workers were seen as occupying a level above housewives, as APTs provided a venue where housewives could be recognized as workers in a country that was ostensibly ruled by the working class. The sense of fulfilment and self-esteem that came with having a danwei played a role.

Economically, even though APT workers were at the lowest rung of the city's pay scale, the pay was sufficient to support the woman worker herself. Interviews with former APT workers conducted in 2011 found that working in neighbourhood workshops definitely made them feel financially independent and gave them a sense of satisfaction for being able to contribute to the household income. A woman who had worked as a childminder in a neighbourhood day-care centre recalled, more than half a century later, her excitement when she received her first month's pay packet of ten-plus yuan, the very first pay she had ever received in her life. A woman worker in a garment workshop told of her feelings about her income: “It was fine if my husband had money, or my parents had money, but none of this counted when it came to me having my own money. Only when I was [financially] independent could I could really have my own status.” Another woman was married to a seaman, a high-paid job at the time. On average, a sailor earned twice as much as a skilled worker and had other benefits.Footnote 73 Thus, financially speaking, this woman did not have to work outside the home, but she believed that “a woman who stays home and depends on her husband would not have political status.” She joined a workshop that made shoe uppers. For her, “the 70-or-80-cent-a-day pay was the foundation of equality between men and women as well as the beginning for a husband and wife to be progressive together.” Although her family was not at all under financial pressure, she often worked overtime in order to meet a goal she had set for herself: to earn 30 yuan a month. Later on, this hard work paid off when she was promoted to head of a street factory.Footnote 74

APTs offered women flexible working hours, something that was not available in more regulated workplaces and an important consideration for women with small children. When APTs were first set up in 1958, they had a somewhat unregulated schedule. As former workers put it: “You brought a stool with you to the shop and started to work, and that was all there was to it.”Footnote 75 Soon after, the work schedule was set at eight hours a day and six days a week, with daily work hours typically from 7:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m., but a worker could take time off without pay largely anytime she wanted. The weekly day off could also be flexibly scheduled and did not necessarily have to be on Sunday.Footnote 76

Some workshops had a piece-rate wage system, allowing workers to take assignments back home to finish. Thus, a woman could register in the workshop and have work assigned to her, but the whole family, typically children and the elderly in particular, could help with the work she took home. Safety pins, for example, were typically assembled at home (the head and the body of a pin was put together by hand for final permanent punching by a machine in a factory). Wages were based on the weight of the pins assembled. Assembling 500 grams of standard-sized safety pins (about 600 pieces) paid only 0.11 yuan.Footnote 77 But, since the assignments could be carried out at home, as long as the worker (or, rather, she and her family) could complete a good amount of work, the pay could still be significant. Another common take-home task was the joining together of machine-woven sweater pieces (i.e. bodies and sleeves). This practice of working in the home continued during the Cultural Revolution. In 1969, there were still about 40,000 such workers, known as “scattered households,” in the city. Some earned as much as 60–70 yuan a month; in a few cases, their income exceeded 100 yuan a month. There were also reports of scattered households secretly delegating their quota to others and taking a commission.Footnote 78

APT work required little skill and therefore there was no educational requirement or probationary period (most other jobs in Shanghai required a three-year apprenticeship). Jobs categorized by the government as work in the “handicraft industry” had a relatively light and physically less demanding workload in comparison to operating a machine or working on an assembly line in a regular factory, where the workers needed to keep up with the pace of the machine. There were also two breaks during the day. The morning one was for “radio broadcast exercises” – that is, exercises to music on the radio or, sometimes, a tape recorder. The other break was in the afternoon for about 15 minutes.Footnote 79 Most workplaces in the city had similar breaks, but the contiguity of the APT with the home apparently made the breaks more beneficial for workers.

Finally, these workshops were within walking distance or a short bicycle ride of home. Most APT employees rarely needed to walk more than a block or two to go to work; for many, the daily commute was just a matter of crossing the street or going to the other end of the alley. The short distance made it possible for most APT employees to return home to make lunch for their families during the hour-long lunch break and do a bit of shopping on the way, as most of the stores for daily necessities were just within a few blocks.Footnote 80 Some workers recalled that they lived so close to their workplace that they could run errands even during work hours. One might go back home to sign for a registered letter when the mailman came or, in the case of unexpected rain, take in laundry hanging on the line to dry.Footnote 81 A former APT worker recalled that she often spent the 15-minute break in the afternoon rushing back home to make a bowl of lotus root paste or some other light refreshment for her bedridden mother.Footnote 82

Starting in 1973, APT employees who had worked for ten years or more were eligible for a retirement pension at the age of 55, based on their years of service. For each year she had worked, an employee received a pension of 2 per cent of her wages or salary, based on her pay rate in the year she retired. Retired workers also received near full coverage of their medical expenses. So, 15 years after the APTs were founded, hundreds of thousands of workers finally received something that they were long overdue.Footnote 83

Conclusion

In reference to gender equality and women's role in society, Mao Zedong famously declared that “women hold up half the sky.”Footnote 84 In the urban neighbourhood workshops and services that were established during the Great Leap Forward in the name of “liberating women's labour power for socialist construction,” nearly all APT workers were female. In terms of sheer numbers, women in fact held up more than half the sky in these workplaces. These enterprises changed the traditional role of the woman as a homemaker. Despite the downsizing in 1960–1961, neighbourhood workshops provided employment for hundreds of thousands of women for decades in the city of Shanghai alone.

The call for women's participation in paid labour in general and the introduction of neighbourhood workshops under the banner of “women's liberation” in particular did not necessarily mean the authorities were genuinely concerned about women's rights or interests. As we have seen, officials were calculating both in initiating the institution and in reorganizing it. Even the official categorizing of various types of neighbourhood workshops was designed to fit certain stereotypes. Chinese policymakers believed that certain types of work were “more suited to women than to men because of the nature of their physique, degree of physical strength and physical characteristics.”Footnote 85 The following policy statement referred to the division of labour in rural areas, but cadres in the city had the same mindset:

Physically, some people are strong while others are weak; some heavy manual farm jobs fit the stronger sex better. This is a division of labour based on the physiological features of both sexes, and is appropriate. We can't impose the same framework on female and male commune members alike in disregard of the former's physiological features and physical power. In some kinds of work, women are less capable than men but in others they are better.Footnote 86

CCP cadres in Shanghai frequently expressed similar views regarding certain types of work they deemed fitting or unfitting for women. Purportedly, the differentiation was based on good intentions, that is, to take into consideration (zhaogu 照顾) the physiology of women workers.Footnote 87

Whether one agrees or disagrees with such an assessment, this kind of practical concern was the basis for organizing a huge throng of unskilled and poorly educated women into the “handicraft” sector of the economy that defined neighbourhood workshops. For Chinese policymakers at the grassroots level, women's liberation as a government dogma, or what scholars have called “socialist state feminism,” had to be adapted to take on board economic considerations and local conditions.Footnote 88 During the GLF, ideological rhetoric asserted that working for such neighbourhood workshops entailed “women's liberation” and “working women as part of the proletariat” but, ultimately, such official proclamations faded into the background and became largely irrelevant in the daily operation of these workplaces.

To the women who went to work in an APT, the new social status conferred by working outside the home was a motivation, but more practical factors such as the income (small but still meaningful), the easy commute to work, the flexible work schedule, the option of doing some of the work at home, the opportunities of manipulating the system to earn extra money, and so on, all figured in their deliberations over whether to work for an APT.Footnote 89 When the workshops were set up, no one could predict their future. In the end, not only did the institution survive but it thrived, greatly contributing to the near-universal employment of urban women and helping to foster a strong sense of job entitlement among them.Footnote 90

There was an undercurrent of manoeuvring and calculating during the GLF and its aftermath that was not readily visible but nonetheless was very powerful. In their analyses of state–labour relations in authoritarian states, scholars have developed the concept of “shades of authoritarianism” in which “a ‘shade’ is an ideal-type of manifestation of authoritarian governance exhibiting a distinct approach to state–labour relations that is nevertheless blurred at the edges.”Footnote 91 To paraphrase, we may say that “liberating women's labour power” during the GLF was a shade of high socialism.Footnote 92 It was a distinct approach by the Maoist state to labour and gender issues, yet it had its “blurred edges” that allowed the state to wield the slogan in times of need and fade it out at will. Likewise, in times of need, women would use the slogan as a basis for political legitimacy to seek an occupation, gain status and protect their lifestyle – in short, to pursue their own interests.

“Liberating women's labour power” has always been the CCP's proclaimed policy, and the GLF did not mark the beginning of such an effort. But, of all the political campaigns launched under Mao – and there were as many as 55 according to one account – the GLF was the only one that included a programme specifically intended to emancipate women from their traditional role as homemaker so that they could work outside the home.Footnote 93 The GLF is regarded as an outrageously irrational campaign, yet a close look at the neighbourhood workshops indicates that a certain rationality was alive and well. The seemingly obscure invention of “alleyway production teams” is an outstanding case of the “sense and sensibility” of both the party-state and grassroots society at a time of madness and chaos. The Great Leap Forward “ended not with a bang but a whimper,” but at least it left one positive bequest.Footnote 94 In the end, as far as the abiding effect of women's participation in the workforce is concerned, it could be seen as a blessing in disguise.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the support provided for this research by the Ivan Allen College Dean's Distinguished Research Award at Georgia Tech and the International Research Centre on “Work and Human Lifecycle in Global History” at Humboldt University, Berlin.

Bibliographical note

Hanchao Lu is professor of history at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He specializes in the history of modern China. His publications include three award-winning books, Beyond the Neon Lights: Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 1999/2004), Street Criers: A Cultural History of Chinese Beggars (Stanford University Press, 2005), and The Birth of a Republic: Francis Stafford's Photographs of China's 1911 Revolution and Beyond (University of Washington Press, 2010). He has served as the editor of The Chinese Historical Review and is currently director of the China Research Centre in Atlanta.