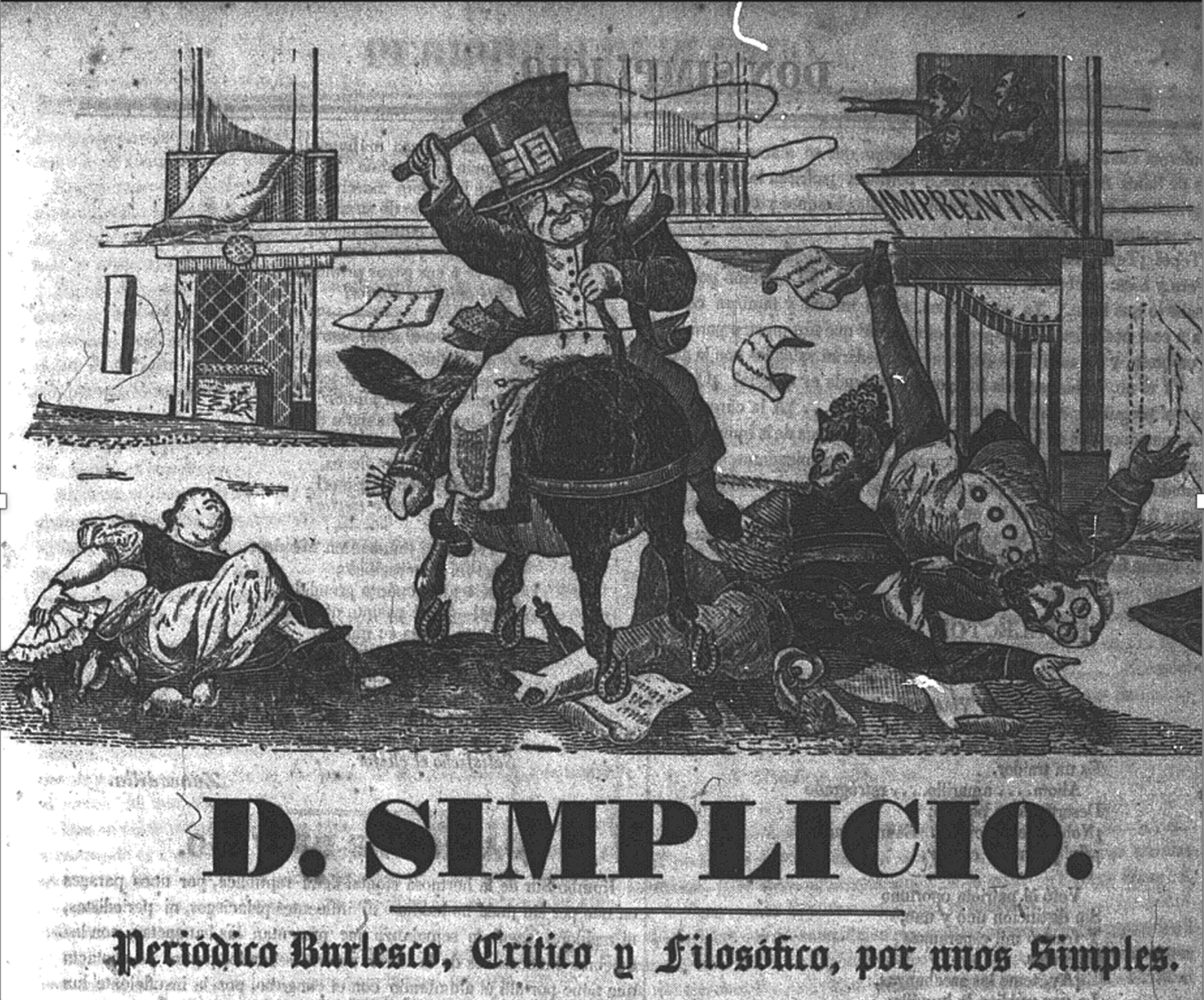

As war with the United States loomed in late December 1845, a satirical biweekly newspaper, Don Simplicio, appeared in bookshops and printing shops and on street corners in Mexico City. Conjured up by Guillermo Prieto and Ignacio Ramírez (‘El Nigromante’, or ‘The Necromancer’), two of Mexico's most brilliant minds, the newspaper offered biting critiques of society's ills, leaders’ failures and governments’ shortcomings. The editors took aim at army officers, clergy, magistrates, bureaucrats, wasteful spending and the ruinous state of Mexican society.Footnote 1 Prieto and Ramírez's self-deprecating and sharply critical tone became one of the newspaper's hallmarks, as did the emblematic frontman they used to launch their attacks. Featuring on the masthead, this figure wore a top hat, leather trousers and a huácaro de indianilla, a short, military-style jacket with tails (see Figure 1).Footnote 2 He sported a panza de usurero (usurer's paunch) and rode a donkey backwards, brandishing a whip in one hand while steering the animal by the tail with the other. Below him, whipped into submission, lay a drunken soldier and a cleric (with the face of a cat) – symbols of still-powerful corporate bodies and legacies of Mexico's colonial past. The frontman's visual and figurative centrality begs at least two questions. First, who was he? Second, why had Prieto and Ramírez decided to use him to engage in debates about society, politics and the nation-in-formation – a nation that some contemporaries feared might simply dissolve?

Figure 1. The masthead of Don Simplicio, c. 1845–6

Source: Microforms collection, Bracken Library, Ball State University, Muncie, IN

The figure was none other than Don Simplicio (Mr Simpleton), the unlikely protagonist of the city's most popular play, Todo lo Vence Amor, o La Pata de Cabra (Love Conquers All, or The Goat's Hoof) by Juan de Grimaldi. La Pata de Cabra, as it became known, was a fantastical, over-the-top comedia de magia, a genre combining stage tricks, illusions, complex machinery and fantasy, and it took the city by storm following its 1841 debut. Audiences revelled in the comedia de magia's wacky song-and-dance numbers and spectacular stage tricks. They also found irresistible the extra-terrestrial travels and serial misadventures of Don Simplicio, the play's bombastic, cowardly leading man who invoked familiar tropes from Spanish Golden-Age literature.Footnote 3 Within a week of its opening, one theatre critic wrote that his cheeks hurt from laughing and claimed that the gracioso (buffoon), Don Simplicio, alone made it worth attending.Footnote 4 Several years later, Prieto speculated that the play had been staged at the New Mexico Theatre at least 30 times.Footnote 5 Writing in 1850, another critic observed that it was the city's most frequently staged play and one that ‘everyone had learned by heart’.Footnote 6 The play's unprecedented box office success led to calls to change its name to La Pata de Plata (a reference to Mexican-minted silver coins, or pesos fuertes, in demand globally) or La Pata de Oro (gold).Footnote 7 La Pata de Cabra's popularity on stage is only part of the story. Off stage, the play spawned at least half a dozen satirical newspapers, whose editors included, in addition to Prieto and Ramírez, prominent men of letters (letrados) José María Rivera, Juan de Dios Arias and Niceto de Zamacois.

Given the tumultuous context – in the 1840s and 1850s Mexico suffered a disastrous war with the United States (1846–8) and careened into civil war a decade later (1858–61), following years of intensifying political polarisation – it might seem surprising that letrados turned to Grimaldi's farcical play to engage in serious debates about the nation.Footnote 8 However, a review of newspaper titles published between 1845 and 1857 – Don Simplicio, El Hijo de D. Simplicio, La Pata de Cabra, La Espada de D. Simplicio, La Patita and El Burro de D. Simplicio (Don Simplicio's Son, The Goat's Hoof, Don Simplicio's Sword, The Little Hoof and Don Simplicio's Donkey) – shows editors centring the play in public discourse in the midst of this uncertainty. Such titles were designed so that readers could easily identify editors’ objectives, ideologies and interests at a glance.Footnote 9 The La Pata-inspired newspaper editors reimagined exchanges, scenes and characters from the play to deliver blistering critiques of public officials, institutions and political customs. They did so in part to insulate themselves against prosecution in a period when press freedoms were subject to a tangle of legal and constitutional regulations and the whims of those in power. The editors were also negotiating the bounds of free speech. In satirising the popular play, they sought to broaden the terms and spaces of public debate, sustain dialogue and strengthen democratic discourse. Their efforts helped make debates and democratic discourse more resilient in tempestuous times.

Free speech preoccupied public men in nineteenth-century Mexico, who understood the idea not only as a right but as central to liberalism.Footnote 10 Indeed, the freedom to publicly express one's opinion was to many constitutive of other tenets of liberalism such as popular sovereignty and electoral democracy. Fractious contests over what could be said and written produced an impressive body of laws, decrees and polemics; and the periodical press was a particularly important space of negotiation.Footnote 11 This article, in tracing the ways editors reimagined the play through their satirical newspapers, shows how a vibrant world of political debate was constructed and functioned. Though it focuses on Mexico City, it engages with a growing body of scholarship that explores strategies individuals adopted to stake their claim in public debates and the body politic in nineteenth-century Latin America.Footnote 12 Its examination of free speech in the nineteenth century also reverberates in our present, for, as Pablo Piccato has argued, ‘Much of the concern about what we call citizenship today (representation, participation in public life, claims of individual rights and obligations) was formulated through the nineteenth century and up to the early post-revolutionary years as, fundamentally, the ability to express one's reason – an individual's demand to be part of public opinion.’Footnote 13

Editors’ decisions to use La Pata de Cabra's fantastic world to express their opinions in public highlight how the worlds of the press and the stage overlapped. They also underscore an important idea: scholars must pay more attention to the dynamic relationship between print culture and performance. Those who study the press often cite the satirical newspapers spawned by La Pata de Cabra. For instance, a renowned compendium of nineteenth-century newspapers classifies Don Simplicio as ‘one of the best examples of Mexican satire’.Footnote 14 Don Simplicio's pages contain satirical poetry, dialogues and more traditional editorials without direct reference to the play. But a reading that fails to account for the ways Prieto and Ramírez embedded language, imagery and characters from the stage to deploy layered critiques results in incomplete comprehension. Because satire works insofar as audiences can peel back its layers and decipher (at least some) of its multiple referents and meanings, such a reading leaves the reader unable to fully grasp the newspaper's irony or its broad appeal.Footnote 15 Scholars of theatre, on the other hand, focusing on the origins of a ‘national’ theatre, have overlooked the Spanish drama's popularity and its incorporation into national and political discourse in Mexico.Footnote 16 An analysis of the phenomenon that emerged around La Pata de Cabra brings these two fields of study – theatre and the press – into productive and necessary conversation.Footnote 17 In particular, this analysis reveals how the two fields converged at mid-century to enable the development of a unique form of public political discourse centred on satirical renderings of the city's most popular play.

This article's focus on the intersections between the press and the stage offers insights into the study of political expression in at least three intertwined ways. First, by examining journalists’ attempts to negotiate press freedoms, this article reveals important efforts to make debates and democratic discourse more resilient. It builds on recent scholarship, arguing that negotiating the bounds of what could be said or written mattered more to politicians and intellectuals than protecting the right to vote.Footnote 18 Second, the La Pata phenomenon demands that scholars of the press and print culture more carefully examine the nineteenth-century stage. Theatre offered a storehouse of symbols that journalists invoked and refashioned to inflict scathing critiques. Indeed, as one literary scholar has argued, theatre became a lens through which mid-century intellectuals interpreted the world.Footnote 19 In selecting a well-known play, satirists spoke to a broad audience, including those who might not have been active consumers of the city's burgeoning print culture. They also wrote with a robust aural culture in mind, expecting debates to spill over into cafés, reading rooms, workshops, popular establishments and street corners where newspapers were read aloud.Footnote 20 Third, an analysis of the La Pata phenomenon highlights satire's power as a political language and potent discursive weapon.Footnote 21 Written satire flourished in the 1840s and 1850s amid political tumult and volatile press regulations, forming an expansion of public debates in those decades.Footnote 22 Letrados capitalised both on satire's ambiguity and on the play's popularity to bolster public debate. Delimiting how and why journalists turned to satire, and to Grimaldi's play in particular, to shape public opinion, define the contours of free speech and make public debates more resilient forces a reconsideration of the broader impact of the satirical press in Mexico.Footnote 23 Satire was not simply a commentary on the political landscape. It was also productive of it, as an analysis of the La Pata phenomenon shows.

This article is divided into three acts, in the spirit of the subject under study. The first summarises Grimaldi's play, situates it in the politico-historical context of mid-century Mexico and explains how the phenomenon that developed around the play changed the political lexicon. The second section, through a close reading of three of the satirical newspapers spawned by Grimaldi's play – Don Simplicio, La Pata de Cabra and La Espada de D. Simplicio – expands upon the first, exploring how journalists reimagined the play to engage a broad public in pressing political debates. The concluding section argues how understanding Grimaldi's play, and editors’ creative satirisations, unlocks a deeper understanding of the period.

Act I: Satire and the Play in a Time of Crisis

At its simplest, La Pata de Cabra was a moralistic boy-meets-girl love story that fitted the romantic mould then in vogue in Mexico.Footnote 24 The play narrates the tale of a beautiful maiden, Leonor, who falls in love with the rogue (pícaro), Don Juan, just before she is to wed the false nobleman, Don Simplicio. The tension over whom she will marry drives the plot, which Grimaldi embellishes with all manner of stage tricks, sets, scene changes and mythical creatures. In the play's opening scene, as Don Juan is about to commit suicide, two pistols magically fly out of his hands and discharge harmlessly. Cupid appears and after more stage effects – the moon and water turn red, thunderclaps are heard and lightning strikes a cauldron holding a goat – he presents Don Juan with a goat's hoof, the talisman that will ensure his happiness and his marriage to Leonor. In Act II, Don Simplicio pursues the lovers, who have fled, balconies move between levels, constables are suspended in mid-air and portraits take up arms against Don Simplicio. As Act II closes, Don Simplicio's hat becomes a hot-air balloon and carries him into space. In Act III, the play becomes even more surreal and otherworldly. Vulcan (a figure modelled on the Greek god Hephaestus), Cyclops and a magician make their stage debuts. The play reaches a climax in Cupid's palace when Leonor weds Don Juan in the presence of Don Simplicio, Don Lope (Leonor's tutor, who arranged the marriage to Don Simplicio) and the crème de la crème of ancient mythological society. In the play's final exchange, a proudly defiant Leonor asserts, ‘You will surely now be convinced, my dear tutor, and you too, my stubborn suitor, that love conquers all.’

Mixed in with the magic and mythical beings, Grimaldi's play featured an improbable – and very funny – protagonist in Don Simplicio. When Don Lope introduces Leonor to Don Simplicio, presenting him as ‘one of the most distinguished noblemen from Navarre’, Leonor looks Don Simplicio up and down before guffawing. Soon thereafter, the audience hears the protagonist's full name for the first time: Don Simplicio Bobadilla Majaderano y Cabeza de Buey. The first part was a riff on the words simpleton (Simplicio), dunce (bobo) and bird-brained (majadero). The second was a play on the surname of famous Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca (‘Cow's Head’; compare Don Simplicio's ‘Ox's Head’). Don Simplicio's foolishness is highlighted when he remarks to his mute sidekick, Lazarillo, after stumbling over his proposal to Leonor, ‘Good sir, I think I made a favourable impression.’ Grimaldi peels back Simplicio's false bravado and bombastic rhetoric to expose his cowardice as the play moves forward. When Don Juan jumps out from behind a mirror to challenge Don Simplicio to a fight, the false nobleman hides behind servants, while proclaiming, ‘Hold me back, boys. Hold me back so I don't kill him!’ By play's end, Simplicio accepts defeat and Leonor weds Don Juan.

However zany, Grimaldi's play teemed with satire. Figures representing authority and power (Don Simplicio and Don Lope) were mocked and defeated. Chivalrous behaviour was shown to be hollow and self-admiring. Leonor's defiance, Don Juan's mockery of his social superiors, the incongruence between honour and status and noble titles, and the calling into question of conventions of masculinity upended social conventions, gender norms and power structures. No scene from the play better captured its satirical overtones than Don Simplicio's observations from his trip into outer space. As Act III opens, Don Simplicio comes crashing back to earth. He tells the search party that has come to find him, headed by Don Lope, about his conversations with the lunar people (lunáticos), a pun on the alternative meaning ‘lunatics’:

Imagine that everything there is the reverse of here. Lovers are constant, spouses are faithful, merchants don't cheat you, officials speak using good manners (con buen modo), soldiers don't swear … In the way they eat, in the way they dress, even in their public entertainments, the lunáticos prefer national things to foreign ones … Literature is honoured there. All men with talent are rich and all rich men are talented. Journalists speak impartially about things they can judge, and they remain quiet about things they cannot judge. Polemics are carried out in a measured way. Everything's upside down, my friend, everything's upside down.

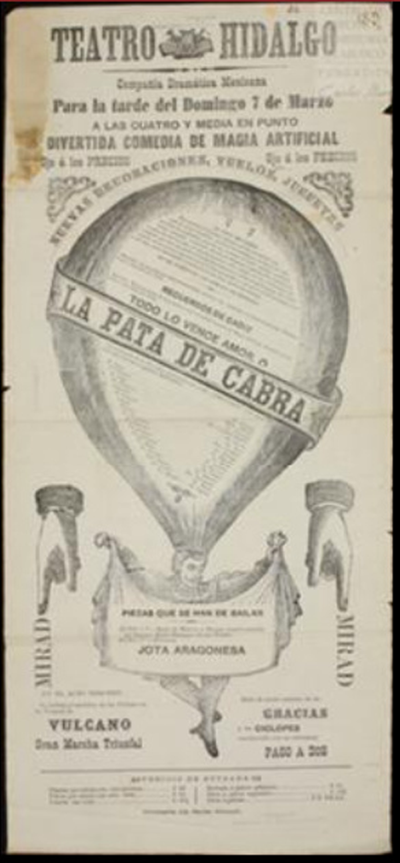

Simplicio's reporting on the moon's topsy-turvy world signalled to audiences the exchange's ironic tone. His observations also resonated with theatregoers in Mexico City, who delighted at the suggestion that the lunático government knew how to conduct business better than their own and that lunático society was more genteel. The prelude to that scene – at the end of Act II when Don Simplicio drifts into outer space suspended from a balloon – was so memorable that impresarios invoked it decades later in theatre posters (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Theatre poster for La Pata de Cabra (the play), 1870s

Source: Centro de Estudios de la Historia de México-CARSO, Mexico City, Impresos Armando María y Campos, Programas de Teatro, Serie 10, Legajo 1379

Full of farce, satire and slapstick, La Pata's whimsical world sent theatregoers into a frenzy. Among the hundreds of romantic dramas, French melodramas, Spanish comedies and operas staged in the city during the 1840s and 1850s, none was as popular as Grimaldi's play. The facile explanation for the play's resonance is that it offered an escapist pursuit. La Pata de Cabra's nutty, bizarre world was so unreal that it helped spectators forget about the challenges of politics and daily life. Humour can indeed act as a powerful salve in times of political disaffection.Footnote 25 There was, however, a figurative and discursive parallelism between the worlds of the play and that inhabited by mid-century theatregoers that made Grimaldi's play work – and work well – for a long time. Journalists found in the stage apt metaphors to explain contemporary politics. For instance, one wrote about President Mariano Arista's 1852 address to the National Congress in his weekly theatre column, describing the speech as a melodramatic mimetic monologue. In the column, the journalist predicted ‘that we will see things [in political drama] as outrageously entertaining as that scene in La Pata de Cabra when Don Simplicio's hat turns into a hot air balloon’.Footnote 26 Impresarios adopted similar language, advertising Grimaldi's play, in the playwright's own terms, as a melo-mimo-drama, mitológico-burlesco, de magia – a mythological, burlesque and comic melodrama that imitated reality – giving audiences some idea of what they could expect.Footnote 27 The farce mid-century residents lived was not populated by mythical creatures, but these seemed no more fantastical than the waves of insurrection, foreign wars, regional separatist movements, presidential ousters, loss and sale of national territory and squander of treasury resources that happened during these decades.

The angst and uncertainty felt by many created favourable conditions for satire. As one historian described it, this was a period of profound disillusion (1835–47) followed by despair (1847–55).Footnote 28 Destructive rebellions in the capital (1840–1) stoked fears of anarchy and social dissolution.Footnote 29 These fears opened a path for military leader, caudillo and six-time President Antonio López de Santa Anna's return to power in what is known as the dictadura disfrazada (1841–4).Footnote 30 The optimism that reigned at the end of the ‘disguised dictatorship’ faded quickly. A series of unpopular decisions by then-President José Joaquín de Herrera's moderado (moderate federalist) government during 1845, including the attempted recognition of Texas's independence, united dissident factions and ultimately led General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga to launch a successful rebellion – the ‘Plan and Manifesto of San Luis Potosí’ – against Herrera in December. Paredes's government, installed on 4 January 1846, failed to achieve its promises to bring order to the treasury and to operate efficiently.Footnote 31 It lost considerable support when the general's secret commitment to a monarchist conspiracy organised by Spanish Minister Salvador Bermúdez de Castro became public.Footnote 32

Mexico's inability – or unwillingness – to set aside factional rows continued into the war with the United States. As US troops advanced toward Mexico City in January 1847, National Guard units in the capital rose up against the government of the puro (radical federalist) Valentín Gómez Farías in the ‘Polkos Rebellion’ (in deprecating reference to the rebels’ support for US President James K. Polk). Street fighting paralysed the city, led to Gómez Farías's ouster, and was followed by a violent nine-month occupation by US forces.Footnote 33 Separatist uprisings in Tabasco and Yucatán further highlighted the state of disunity. Those events, combined with the loss of more than half of Mexican territory following the 1848 signing of the Guadalupe Hidalgo peace treaty, dealt a huge blow to national morale. In the wake of defeat, conservative statesman Lucas Alamán lamented that Mexico since its independence (1821) had moved ‘from infancy to decrepitude without ever having experienced the vigour of youth’.Footnote 34 Moderado Mariano Otero reportedly blamed Mexico's defeat on the lack of a national spirit.Footnote 35

Political polarisation heightened in the war's aftermath. Struggles between moderados, puros, conservatives, monarchists and santanistas (supporters of Santa Anna) intensified. These divisions were formalised through the creation of the Conservative Party and the Santanista Party in 1849. The failure of successive moderado Presidents Herrera (2 June 1848–15 January 1851) and Arista (16 January 1851–5 January 1853) to establish a stable constitutional government, revive the economy, address social grievances, resolve church–state tensions and introduce enduring reforms exacerbated tensions.Footnote 36 An uneasy alliance between the military, conservatives, puros and santanistas that returned Santa Anna to power for the sixth and final time (20 April 1853–12 August 1855) dissolved quickly. By late 1854, Santa Anna's rabid anti-liberalism and repression had lost him considerable support, including from loyalists.Footnote 37 The resistance movements that emerged through the Plan of Ayutla (1 March 1854) eventually forced Santa Anna from power, but they also pushed the country closer to civil war. In the following years, moderados and puros fought amongst themselves and with conservatives to dictate the country's future, instituting laws and decrees in the late 1850s and early 1860s that separated church and state, granted the state power to intervene in ecclesiastical affairs and divested the church of property and wealth. Tensions spilled over into outright violence in early 1858, starting a three-year civil war that claimed at least 8,000 lives.

Fractious negotiations over free speech and a series of frequently changing regulations governing freedom of the press contributed to the era's instability.Footnote 38 Political authorities issued press laws to balance protecting individual liberties with securing political control, though the latter most often won the day.Footnote 39 A brief overview of press legislation during and after Mexico's war with the United States reveals how quickly and dramatically regulations could change. In 1831, the government of Anastasio Bustamante suspended press juries (groups of citizens of good standing who judged the merits of alleged violations and meted out punishments), which had been established in 1821. Later that decade, federal district governor, José María Tornel, banned the voceo, the practice of reading newspapers out loud in public; this instance marked at least the third time such a ban had been put in place since 1824.Footnote 40 In early 1846, President (and General) Paredes met with opposition editors and threatened them if they disturbed the peace with their writings.Footnote 41 Paredes issued two new decrees when the editors failed to comply; the second, declared in April, imposed a blanket moratorium on criticism of authorities. Officials raided newspaper offices and printing shops, shutting down presses and jailing many editors, including Prieto and Ramírez.Footnote 42 On 14 November 1846, provisional President José Mariano Salas declared a reglamento (ruling) that in large measure protected press freedoms; while the new law expanded what were considered abuses of the press, it nullified existing restrictions and re-established press juries, increasing their size.Footnote 43 In 1848, moderado President Herrera reconfigured the November 1846 press law, expanding the definition of defamation to include satires and invectives. This law led to the arrest and imprisonment of journalists Francisco Zarco and Antonio Pérez Gallardo, who had accused Herrera's minister of war, Arista, of acting unpatriotically during the US–Mexican War.Footnote 44 On 22 September 1852, Arista, facing growing unrest and open rebellion, passed a law that prohibited freedom of the press. That restriction was overturned six weeks later, only to be reversed on 25 April 1853 by the Ley Lares, Mexico's most severe press law. The Ley Lares silenced opposition to Santa Anna's rule and led to the closure of over 40 newspapers.Footnote 45 On average fewer than six newspapers were published per day while the law was in effect (until August 1855).Footnote 46

Journalists deployed satire in part to navigate this fraught tangle of regulations and extra-legal harassment over free speech. They also did so to express dissatisfaction with the instability, hypocrisy and general lack of national unity they observed, and to call their contemporaries to action.Footnote 47 Satirists criticise the existing social or political order in an effort to improve society, not merely to express indignation. Believing, with Gilbert Highet, that ‘most people are purblind, insensitive, perhaps anesthetized by custom and dullness to resignation’, ‘[The satirist] wishes to make them see the truth – at least that part of the truth they habitually ignore.’Footnote 48 Satirists do this by forcing listeners/readers to reconcile the incongruity between incompatible scripts, between the real and the humorous.Footnote 49 Audiences in turn experience humour (satire, irony and parody) at the intersection of these scripts, when they realise – then process – the discrepancies between what is written and what is intended, or between what is and what could or should be.Footnote 50 When done well, the rewards to the reader/listener are twofold: ‘the pleasure of an aesthetic experience coupled with the reasonable hope that a stable political order may be attainable’.Footnote 51

In Mexico and Latin America more broadly, both written and performative satire had enjoyed a long history. Satire appeared in lampoons (pasquines) that criticised colonial authorities, in the poetry of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and in the limericks of eighteenth-century Afro-Mexican José Vasconcelos (‘El Negrito’, ‘The Little Black Man’).Footnote 52 It infused marionette performances in elite homes and in public spectacles which featured the immolation of papier mâché effigies.Footnote 53 During the early decades of the nineteenth century, satirical expression surged. Satire filled the pages of José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi's novels and inspired political caricatures like José María Torreblanca's El Mono Vano (The Vain Monkey).Footnote 54 It featured in puppet theatre productions, where characters serving as social critics mocked political, religious and social authorities.Footnote 55 A more public, carnivalesque expression of satire took root in annual Holy Week Judas burnings. Such events temporarily inverted the social order, as effigies of Judas Iscariot – and hated political figures – were destroyed.Footnote 56

Satirists in mid-century Mexico drew upon a wealth of cultural references to expose bitter truths. Many had read classical works from Greece and Rome and the writings of Enlightenment thinkers. Ramírez reportedly knew from memory classical Greek and Roman texts, possessed a profound understanding of Voltaire and based many of his own writings on the ideas of Adam Smith and Jeremy Bentham.Footnote 57 Satirists immersed themselves in the worlds of literature, poetry and drama. They were also keenly aware of deeply rooted, popular, performative satire. In reimagining Don Simplicio's character (and Grimaldi's play more broadly), the satirists considered in this article sought to produce intense irony and elicit a good laugh by suggesting that a foolish, irrational cultural persona could lead the country more adeptly than the individuals who had actually taken the reins. To be sure, these journalists-cum-satirists were concerned with bolstering their status as some of the country's most combative and important political figures.Footnote 58 But their enterprise extended beyond the politics of humiliation or self-fashioning.

The editors of the La Pata-inspired newspapers sought not only to speak truth to power but also to make public debates more resilient through satirisations of Grimaldi's play. By capitalising on the play's popularity, they aimed to broaden engagement among their readers/listeners, including those less attentive to politics. Though this argument – about satire's ability to broaden engagement – draws on findings from more recent empirical scholarship on the effects of political satire, evidence from mid-nineteenth-century Mexico points to a similar conclusion.Footnote 59 As this article reveals, satirical renderings of Grimaldi's play expanded the political lexicon in an era when political ideas circulated widely due to new technologies that enabled larger print runs.Footnote 60 By the late 1840s, Don Simplicio had become linguistic shorthand in the press. Prieto and others adopted it as their pen name. In the mid-1850s, Zamacois, the conservative Spanish-born journalist and editor of La Espada de D. Simplicio, delivered critiques as ‘slaps’, channelling the scene when Don Simplicio mocks a portrait then slaps the figure before it comes to life and disarms him. Puro journalists Arias and Rivera offered their own brand of satirical invective, or pati-cabriología (‘goat's hoof-ism’), peddled by a goat-journalist – a creature they imagined into existence through their newspaper, La Pata de Cabra. More generally, satirists used the play to stir up and sustain debates about ‘forbidden’ topics. They reimagined scenes and characters to shine light on two-faced politicians, the Catholic Church's hypocrisy and the country's lack of unity, its numerous constitutions and political customs that hindered the nation's development.

Act II: The La Pata-Inspired Satirical Press

Grimaldi's play spawned at least six satirical political newspapers in Mexico between 1845 and 1857, four of which were published in the capital. El Hijo de D. Simplicio was printed in Orizaba from 1849 to 1851.Footnote 61 Following the toppling of Santa Anna's dictatorship in 1855, Arias and Rivera published La Pata de Cabra six days per week from August 1855 to February 1857 while Zamacois's La Espada de D. Simplicio ran 100 editions from November 1855 to March 1856. The fifth, La Patita, a so-called ‘descendant’ of La Pata de Cabra, was published for only a few months between May and September 1857.Footnote 62 Gerardo Yeliat published the sixth, El Burro de D. Simplicio (August 1857–April 1862), in Tlaxcala.

The appearance of La Pata-inspired newspapers formed part of a broader florescence of written satirical expression in the 1840s and 1850s. Editors dedicated columns to the discussion of satire.Footnote 63 They published satirical weeklies and serialised newspaper columns like Juan Bautista Morales's El Gallo Pitagórico (The Pythagorean Rooster, 1842–4). A number of these publications drew inspiration from the stage. There was, for instance, D. Juan Tenorio (1849–50?), a newspaper that backed Bernardo Couto's candidacy in the 1850 presidential election and whose title invoked Spanish playwright José Zorrilla's caricature of the libertine Don Juan.Footnote 64 There was also El Diablo Verde (The Green Devil), an anti-monarchical weekly published in Querétaro (November 1849–April 1850) dedicated to instructing Queretanos on electoral rights and understandings of the law.Footnote 65 El Diablo Verde took its name from a comedia de magia that competed with Grimaldi's play and featured collaborations from Rivera and Arias, future editors of La Pata de Cabra.

Scholars have convincingly argued that attempts to draw clear boundaries between literary pursuits and political writing are ahistorical enterprises.Footnote 66 The newspaper editors-cum-satirists considered in this article operated across multiple fields. As ‘poet-legislators’, they embraced public life, mixing politics and literature, journalism and legislative action, armed conflict and oratory.Footnote 67 Prieto, for instance, held political posts, wrote for literary magazines, penned theatre chronicles and costumbrista sketches (sketches of manners and customs) and gave rousing public speeches. He even took up arms during the 1847 Polkos Rebellion.Footnote 68 Ramírez, ‘El Nigromante’, was a writer, poet, lawyer and public official, who served twice as education minister and once on the Supreme Court.Footnote 69 Arias was principally a writer. He founded 14 newspapers, including La Pata de Cabra, and contributed to many more.Footnote 70 He also served as a deputy to the 1856 constitutional convention and as secretary of state for Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada's government. While Prieto, Ramírez, Arias and others engaged in multiple modes of writing, the La Pata-inspired satirical publications allowed them to commingle politics and theatre, poetry and editorials, farce and reality.

From Don Simplicio's first edition in December 1845, Prieto and Ramírez fashioned reputations for delivering incisive critiques. Across 110 issues spanning 17 months (December 1845–April 1847), the newspaper adopted a seriocomic and self-deprecating tone to address constitutional reform, press freedoms, taxes, laws, elections, pronouncements, the rise of monarchism and war with the United States. Don Simplicio's format was similar to contemporary newspapers; most editions led with an editorial and included sections for news, letters to the editor, trade or commerce (parte mercantil) and public entertainments. However, by blending and juxtaposing real news and satirical expression, Prieto and Ramírez blurred the boundaries between the real and the seemingly absurd. They thus capitalised on the incongruity – and especially the irony – readers experienced when they encountered the unexpected. For instance, Don Simplicio's first edition closed with an announcement. In the space reserved for notices about upcoming theatrical performances, it read

PUBLIC ENTERTAINMENTS

NATIONAL THEATRE

Tonight. – New Comedy:

‘Imminent Conflict. Yankees in Matamoros

and Mexican troops in San Luis’Footnote 71

Not all of Don Simplicio's satire was so grim. In a mid-January 1846 issue, Prieto and Ramírez situated an urgent and serious editorial about constitutional reform alongside an article whose tone was more waggish; in that article, titled ‘The Future Constitution!’, the editors proclaimed: ‘We don't want a federation, or centralism, or monarchy, but rather riots.’Footnote 72 The irony was multi-layered, emerging not only from the incongruence between the excitement connoted by the article's title and the gloomy tone of its content but also in readers’ understanding of the editors’ actual aversion to anarchy.

Prieto and Ramírez's jocularity belied a fearlessness to confront powerful generals and political figures. In their first edition, the editors issued a fictional pronunciamiento (pronouncement) in response to the Plan and Manifesto of San Luis Potosí (15 December 1845) put forward by Generals Paredes and Manuel Romero. Pronouncements like this one were an accepted, if extra-constitutional, way of conducting politics and bringing about political change;Footnote 73 they were also frequent, with some 1500 declared nationwide between 1821 and 1876.Footnote 74 Aside from provoking the ire of Paredes and Romero, the difference in tone between the generals’ plan and the ‘Pronunciamiento de Don Simplicio’ was stark. Whereas the San Luis pronunciamiento claimed to speak for the will of the nation (as nearly all pronouncements did), Don Simplicio's began, ‘Compatriots, the plan I have proclaimed is not the expression of the national will, for the simple reason that I don't know what the national will is, and, I confess, I doubt such a thing even exists …’Footnote 75 The self-deprecating tone of the parodic pronunciamiento laid a foundation for the editors’ long-running social critique. Poking fun at the ubiquitous ‘political custom’ of the pronouncement and the mania for public office-holding (empleomanía), Prieto and Ramírez wrote, ‘Live off the fatherland. Get a job, marry without means, and make pronouncements annually. These are pleasures only a Mexican can understand.’Footnote 76

As evidenced above, part of Don Simplicio's appeal came from the editors’ inventiveness. Prieto and Ramírez embedded criticisms within familiar religious and literary forms like psalms, poems, dialogues, chronicles and theatrical skits. For example, in one edition, they replaced the standard editorial, or ‘Ass's Bray’, with a satirical ‘Simplician’ psalm that asked why God had given Mexicans so much in abundance yet had been so economical with judgment.Footnote 77 In other editions, Prieto and Ramírez invoked for readers memorable scenes from the play, especially Don Simplicio's trip to the moon. The editors reimagined these scenes to critique Mexico's inefficient customs collection system, its deplorable transportation infrastructure and the weakness of law and order.Footnote 78

Don Simplicio's editors frequently used stage language and imagery to tap into the surging popularity of theatregoing; the number of theatres in the city grew fourfold between 1840 and 1860.Footnote 79 In March 1846, Prieto and Ramírez packaged a critique of General Paredes's failed monarchist plot as a fable to be enacted on stage.Footnote 80 In the fable, the ‘wise’ cats (the president and his followers) created an elaborate ruse to catch rats (republicans), only to have their brilliant trap revealed. Prieto described this plan and trap in vivid detail as if it were a complex piece of stage machinery. A board connecting the structure's wooden support pillars formed a narrow path that led to an aromatic European cheese. A trapdoor hid a boiling cauldron of water into which the rats would fall to their deaths. Because foreign cheese (forms of government like monarchy) made them sick, none of the rats fell into the trap. But the machine's inventor, General Paredes, continued to insist the machine worked, and he sent his helper to his death in a final golpe teatral (theatrical coup de grâce). Written in verse, the fable ended: ‘Look for another way to betray the nation, oh monarchist faction!; it was because of a lazy stagehand (maquinista) that the trap (la tramoya del ratón) was laid bare.’

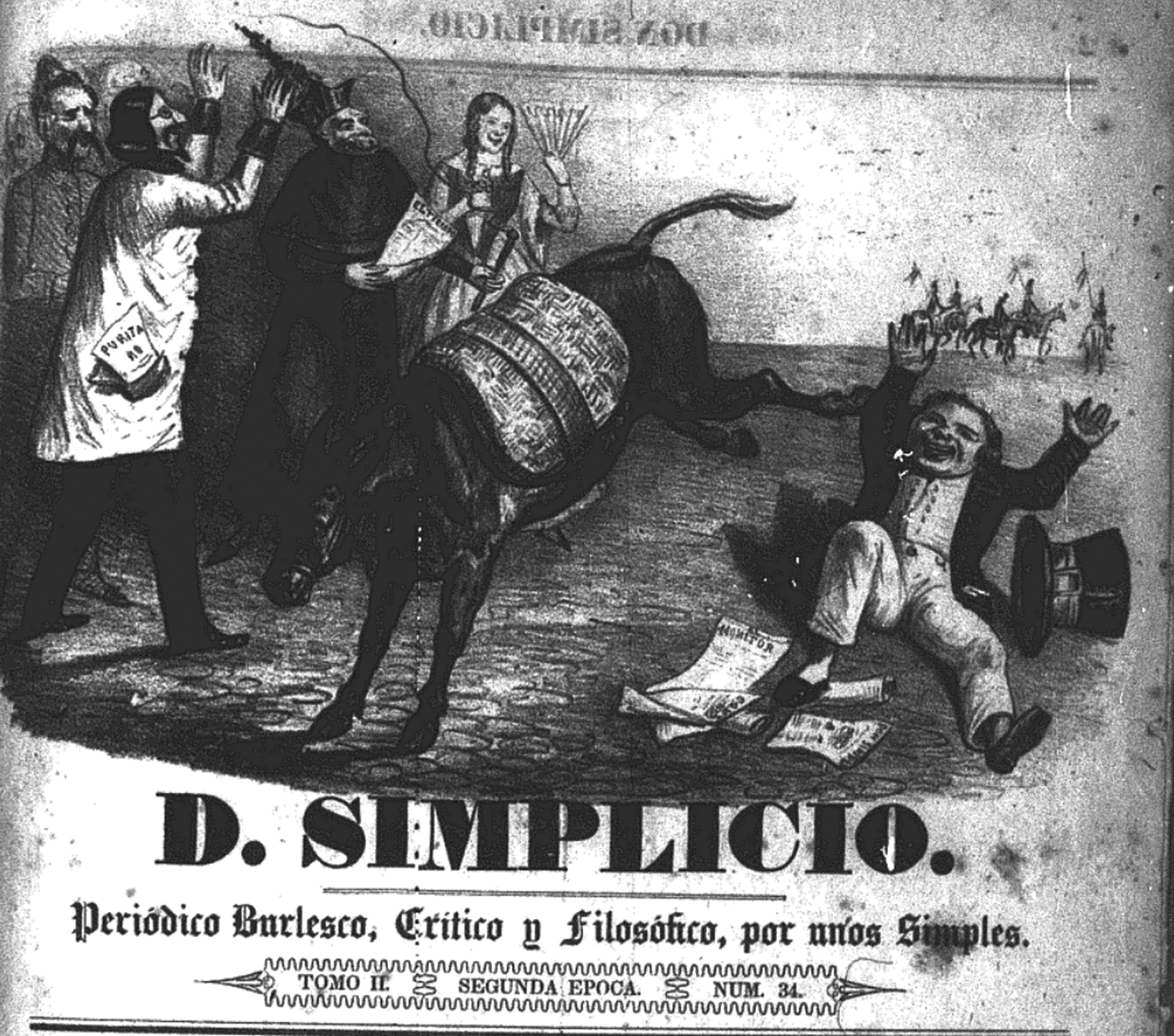

The men's attempt to turn the real world upside down through satire was not without risk. Soon after the fable was published, General Paredes ordered a crackdown on press freedoms that landed Prieto and Ramírez in jail for several months – an act the editors satirised in an image that was the sole item on the newspaper's front page on 25 April, depicting Don Simplicio temporarily toppled from his donkey while the other figures from the masthead celebrated (Figure 3). In a bold rebuke, Prieto and Ramírez re-opened the newspaper on 1 July 1846 with the publication of a fictional new play.Footnote 81 The play's protagonist, Don Simplicio, declares: ‘I've broken my ribs! But I've triumphed!’, echoing the line shouted by Grimaldi's protagonist upon his return from the moon. When questioned by another character as to what he had triumphed over, Don Simplicio states ‘fear’. After their imprisonment, Prieto and Ramírez published Don Simplicio three times per week until April 1847, when the newspaper closed permanently. Despite the closure, both men remained central figures in public life. In addition to writing poetry and plays, Prieto served in the National Congress for decades and in the cabinets of four presidents, and was director of the postal service.Footnote 82 Ramírez founded and wrote for other newspapers, created the National Library while serving as a minister in Benito Juárez's cabinet (1861) and worked as a magistrate on the Supreme Court until his death in 1879.Footnote 83

Figure 3. The masthead of Don Simplicio, 25 April 1846. Don Simplicio is shown toppled from his donkey, as the newspaper's editors were briefly jailed.

Source: Microforms collection, Bracken Library, Ball State University, Muncie, IN

Partisan lines had hardened considerably by August 1855, when puros Rivera and Arias published the satirical daily La Pata de Cabra (see Figure 4). In addition to a demoralising war with the United States, the nation had endured two years of anti-liberal rule by Santa Anna – effectively silencing the opposition press and severely curtailing press freedoms through the Ley Lares. Because of these transformations, Grimaldi's play retained its relevance. Satirisations even intensified, judging by the number of La Pata-inspired newspapers published between 1855 and 1857. An analysis shows that the rhetoric contained in the newspapers did not become markedly more instrumental and adversarial, as Elias José Palti has argued.Footnote 84 Instead, Rivera, Arias and Zamacois (editor of La Espada de D. Simplicio) sought to make public debates more resilient amid acute political polarisation by appealing to readers’/listeners’ familiarity with the play.

Figure 4. La Pata de Cabra (the newspaper), 1855

Source: Courtesy of DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, University Park, TX

Arias and Rivera sustained debates through a biting form of satire they called ‘goat's hoof-ism’, delivered by an anthropomorphised goat. In the paper's second edition, published on 23 August 1855 in the midst of a cycle that saw factions make pronouncements in San Luis Potosí, Nuevo León and Mexico City, Arias and Rivera channelled Grimaldi's play through a dramatic scene they entitled ‘Don Simplicio on the Moon Meditating Reforms for Mexico’. The scene opened with, ‘What a stupendous thing! Here on the moon, soldiers stand at the vanguard of democracy, because of which the public loves them. The moon's president solicits the will of the people … and agiotistas [usurious lenders] have their wings clipped like bats so they cannot fly away.’Footnote 85 The criticism of Santa Anna's most recent dictatorship, infamous loan sharks and the central role soldiers had played in a recent slew of pronunciamientos was clear. In the future Mexico imagined by the newspaper's editors, soldiers followed the law, politicians listened to the people and lenders put patriotism over profits.

Arias and Rivera railed against the republic's lack of nationalism and they questioned the patriotism of its inhabitants and leaders, just as Ramírez and Prieto had done a decade before in Don Simplicio. On 24 September, with debate raging about who should permanently assume the presidency following Santa Anna's forced resignation, La Pata de Cabra staged in its pages a public auction at the national palace entitled ‘Nation for Sale to the Highest Cash Bidder’.Footnote 86 The auctioneer received not a single bid for ‘that beautiful place full of illusions that after 11 years of fighting won its independence, a candid place full of vigour and civic virtue, possessing the elements of happiness’. The following month, with no more certainty over who would replace Santa Anna, Arias and Rivera published a fictionalised theatrical skit in which a character cast as president claimed, in a mixture of prose and verse, ‘It is difficult to govern a nation where there's no public spirit, where people join together like leeches in a pot because they were put there … where there's no patriotism / and only selfishness / where bureaucrats rob / with vile pretensions.’Footnote 87

La Pata de Cabra ruthlessly criticised politicians, especially the exiled Santa Anna. In a faux independence celebration staged in the newspaper's pages on 11 September (instead of the usual 16 September), Arias and Rivera pilloried the patriotic committee (a the group of citizens charged with organising independence day celebrations) for failing to celebrate the day when the ‘illustrious fugitive, His Most Serene Highness, Don Simplicio Bobadilla, Santa-Anna, Majaderano, Cabeza de Buey y Mano de Gato … that hero of a hundred battles’ had defeated invading Spanish forces at the Battle of Tampico in 1829.Footnote 88 This satirical passage packed a heavy punch. It mocked Santa Anna's self-proclaimed title (‘Su Alteza Serenísima’) and his self-importance; when president, Santa Anna insisted that independence be celebrated on the date he defeated Spanish forces in 1829 rather than on the date of Father Miguel Hidalgo's call to arms in 1810. It also compared him to Don Simplicio and thus to Grimaldi's cowardly stage character. Its charge of ‘Mano de Gato’ (Cat's Paw) laid bare the allegations of rampant corruption, and even treason, that plagued the former president. It likely invoked for readers Santa Anna's 1853 Venta de La Mesilla (Gadsden Purchase) of 45,000 square miles of land in present-day Arizona and New Mexico, for US$ 10 million, which he had squandered by spring 1854.Footnote 89

Reflecting the hardened ideological positions of the post-war era, Arias and Rivera were sceptical of moderados like Ignacio Comonfort. Even though Comonfort had supported both the heterogeneous alliance to overthrow Santa Anna (organised through the Plan of Ayutla) and the interim government of puro general Juan Álvarez, Arias and Rivera worried whether Comonfort could rein in his puro ministers and a puro-dominated Congress. They also doubted his ability to overcome the vested interests and corporate bodies that had influenced his predecessors; Comonfort was deeply unpopular with conservatives, army officers and priests.Footnote 90 In October 1856, La Pata de Cabra published a caricature of Comonfort, depicting him as a political tightrope walker (un maromero político) trying to balance the demands of puros and conservatives.Footnote 91 The editors’ suspicion would prove well founded when Comonfort's attempted self-coup against his own government backfired in late 1857 and early 1858, throwing the country into civil war.

Arias and Rivera directed much of their vitriol at the conservative press. In editorials, they accused La Verdad of telling lies and spreading hearsay while they charged that La Sociedad was run by gachupines (a derogatory term used to refer to Spaniards) and read by corrupt conservative political opportunists.Footnote 92 However, none received more critical attention than monarchist-leaning Spaniard Zamacois's La Espada de D. Simplicio. By 17 November 1855, when La Espada de D. Simplicio first appeared, its creator had established a reputation as a prolific writer, sharp intellect and keen observer of customs. Zamacois wrote poetry, plays and zarzuelas (operettas). He also authored a 20-volume history of Mexico and wrote two entries for Los mexicanos pintados por si mismos alongside fellow contributors Rivera, Arias and Ramírez.Footnote 93

In the pages of La Espada, Zamacois offered a conservative counter-narrative. The newspaper's motto, ‘The sword is the best form of reason’, produced irony on at least two levels. On one level, it was a jab at liberals’ claims to hold dominion over reason. On another level, it tapped into readers’ and audiences’ knowledge of Don Simplicio's morbid fear of confrontation. Indeed, few things illustrated the stage character's cowardice better than the sword rendered useless in his trembling hands. Zamacois's deployment of the sword as a figurative weapon, then, should be read as a reimagining of its power. Wielded in the right hands (read: conservative), it could, for once, serve as a formidable weapon.

Zamacois directed his attacks in La Espada at liberal newspapers and public figures. In its prospectus, he promised to ‘unmask La Pata de Cabra's intellect when it lacked judgment’ – a promise he fulfilled, especially in a bitter week-long exchange in early February 1856 when he criticised Arias and Rivera for excessive grammatical mistakes.Footnote 94 Zamacois lambasted El Monitor Republicano and El Siglo XIX, the city's liberal dailies, for unleashing borregos, or false news stories.Footnote 95 Beyond rival newspapers, La Espada aimed its attacks at public figures, the city council and the government of moderado Comonfort through original lyric poems entitled ‘cintarazos’, or slaps – invoking the scene from the end of Act II in the play. Zamacois was especially critical of liberal governments’ failure to pay salaries and pensions in the months following Santa Anna's ouster. In a contrived dialogue between an ex-employee of the treasury and his mother-in-law, she offers the following advice: ‘I'm nothing more than a poor woman but I think to become minister of the treasury one needn't read more than four books to understand perfectly the country, its resources and riches, its needs, etc. and … not paying anyone and receiving much [in taxes], well, anyone can serve as minister.’ The dialogue ended in a couplet that read: ‘He who pays badly and overcharges / Has much money left over.’Footnote 96 Zamacois followed up this thinly veiled critique with a full-fledged assault days later, condemning the injustice of the decision by former Don Simplicio editor Prieto, now treasury minister, to lay off some public employees and reduce the salaries of others.Footnote 97

In spite of their divergent views and heated exchanges, the editors of La Pata de Cabra and La Espada de D. Simplicio, and indeed of all the La Pata-inspired satirical newspapers, shared a commitment to take on the ridiculous through Grimaldi's play, even if they disagreed sharply on what was ridiculous. For example, Arias in an 1856 editorial criticised the Comonfort government's passage of the Ley Lafragua, a press law that made it easier for authorities to track down anyone who violated its provisions.Footnote 98 The new law suspended press juries, forbade political caricature and forms of satirical expression that ‘incited disobedience of the law or the authorities’ and required authors to sign their names under what they wrote.Footnote 99 In the editorial, Arias informed readers that the goat-journalist had metamorphosed into a human as a result of the provisions of the new law. He then wondered how the government could prohibit the use of ridicule when its own dealings were, in fact, absurd. Perhaps trying to deflect attention from an accusation that was sure to attract unwanted attention, Arias followed up with a claim that was light-hearted and self-deprecating: ‘Because of the new law, [the editor of] La Pata has been guaranteed that no one will ridicule the name of this newspaper, no matter how absurd it is.’Footnote 100

Conservative and puro journalists alike abhorred the Ley Lafragua.Footnote 101 Zamacois criticised the new law's provisions in multiple editorials.Footnote 102 In the end, however, the law substantively altered La Espada's content; Zamacois ceased publishing his original satirical verses and he toned down critiques while gauging the new law's enforcement. In mid-March 1856, ‘convinced that the current press laws do not allow our newspaper to publish anything of interest’, Zamacois suspended publication indefinitely.Footnote 103 La Espada's demise in the wake of the Ley Lafragua was not unique. Enforcement resulted in the closure of more than a dozen newspapers in Mexico City and Guadalajara between January and November 1856, though La Pata de Cabra was not among them.Footnote 104 Similarly to other newspapers, the peddlers of pati-cabriología became more cautious.Footnote 105 Caustic editorials became infrequent, and at times the editorial section disappeared altogether, as the focus turned toward theatrical productions, operas and other diversions.Footnote 106

Nonetheless, debates and critiques that appeared in the press reverberated because of long-standing journalistic practices. Zamacois's La Espada de D. Simplicio, for example, republished articles from conservative newspapers like La Sociedad and El Ómnibus and liberal ones such as El Monitor Republicano and El Heraldo. Most returned the favour. The conservative El Ómnibus reprinted editorials and poetry from Zamacois's newspaper on a weekly basis, while El Monitor Republicano republished editorials and poems from La Pata de Cabra bimonthly. A decade earlier, El Monitor Republicano reprinted material from Prieto and Ramírez's Don Simplicio biweekly, including each of the satirical paper's scathing, non-satirical editorials or ‘brays’.Footnote 107

Rising literacy rates and editors’ familiarity with the city's aural culture broadened and strengthened debate, too. A commission formed in 1845 to study the state of public instruction found that the expansion of literacy in the city had been ‘rapid, visible and glorious … and that literacy now reached diverse classes within the city’.Footnote 108 Waddy Thompson, US Minister to Mexico (1842–4), noted similar trends. He recalled in his memoir that all the servants he encountered could read. He also remembered having ‘often observed the most ragged leperos [drifters], as they walked down the streets, reading the signs over the store doors’.Footnote 109 While these anecdotes are merely suggestive of higher-than-assumed literacy rates, an individual's ability to read text independently was only part of such a calculation. Ideas and debates in the press circulated widely through read-aloud practices. Contemporary visual depictions such as José A. Arrieta's 1851 oil painting ‘Tertulia de pulquería’ show reading aloud to be a collective and social act; in Arrieta's painting, six men and a woman congregate at a table in a popular establishment drinking pulque while engaging boisterously in a discussion of contemporary newspapers and broadsides.Footnote 110 Such practices enabled and widened engagement in politics and public life.Footnote 111

We should thus abstain from drawing hasty conclusions about newspapers’ impact based on stubborn beliefs about widespread illiteracy or circulation rates: sales may have ranged from 200–500 for the biweekly Don Simplicio and up to 8000 for the daily La Pata de Cabra.Footnote 112 Satirists understood the power of the press to shape public debates. They also knew how the written word circulated, and they built these understandings into the design of their publications. Weaving together dramatic sketches, poetic verses, songs, short stories, editorials, letters and epigrams – forms that lent themselves to public readings – these seriocomic newspapers were at once whimsical and didactic, humorous and critical. Editors captured listeners’ and readers’ attention by writing with flare and style. Some, it seems, were quite successful. Writing in the early 1880s, statesman, soldier and literary figure Vicente Riva Palacio noted that Arias and Rivera's La Pata de Cabra was so popular that it was remembered fondly decades later.Footnote 113

Act III: The Conclusion, or Seriously Joking

Don Simplicio became a great cultural symbol of mid-nineteenth-century Mexico City. That much is clear, but important questions remain. How, for instance, can we explain Don Simplicio's rise from bumbling stage character to symbolic avenger of political and social ills? What effect did the La Pata phenomenon have, and how does its examination deepen our understanding of Mexico's mid-nineteenth-century history?

The unrivalled popularity of Grimaldi's play explains in part Don Simplicio's rise to prominence. Following its 1841 debut, the play was staged dozens of times that decade. By the early 1850s, Grimaldi's play was regularly given at the city's principal playhouses as the half-price Sunday matinee, patronised by families and more popular audiences. The play was staged frequently at second-class playhouses as well. By 1880, productions of Grimaldi's play in Mexico City numbered at least 120, and likely far exceeded that, considerably outpacing any other production.Footnote 114 Audiences clamoured for the play because it offered something for everyone; in David Gies's words, ‘[the play's] strength lay in that it had (in abundance) … flashy spectacle, local color, stage tricks, topical humor, puns and jokes, knock-about comedy, wonderful acting, a fast-moving plot and suspense’.Footnote 115 Impresarios capitalised on theatregoing trends and tastes. They advertised the extravagant costs of a particular production's mise en scène, including newly painted sets and elaborate stage machinery.Footnote 116 La Pata de Cabra's resonance radiated beyond the playhouse stage. Music from the play featured in open-air concerts in the Alameda, one of the city's largest public parks, and bookshops sold copies of the script.Footnote 117

Don Simplicio also became an avenger of social and political ills through the efforts of satirists who reimagined him as a stand-in for corruption, incompetence, greed, pretension and unfulfilled promises. Their satire contributed to this transformation by facilitating the play's movement between the playhouse, the press and the public imagination. On-stage productions sustained interest in and shaped the way audiences understood and engaged with satirical renderings in the press and public life, while satirisations in periodicals injected new meanings into on-stage performances. Indeed, the La Pata satirists were so successful at inserting the play into public debates that non-satirical newspapers followed suit. For instance, in 1850, El Siglo XIX's editors lambasted the conservative El Universal for alleging that the former's editors never wrote about issues pertaining to the public interest. ‘El Universal that fills its columns with bland declarations; El Universal which dodges serious polemics’, the editorial thundered, ‘El Universal, which offers promises, and like Don Simplicio, and never fulfils those promises …’Footnote 118 Such references appeared in public debates for decades.Footnote 119

Why, then, did satirists try so hard for so long to sustain these debates through Grimaldi's play? Moreover, how effective were they? Answering these questions requires a closer examination of satire. Scholars consider satire as both an art form and as a persuasive discourse. They also see its essence as humanitarian; satirists criticise because they believe things can be better and they want them to be so.Footnote 120 The first goal of the satirist is to convince others to listen and care sufficiently. The second and considerably more difficult goal is to inspire others to challenge the existing order. But even if people are compelled to act, what role does satire play in this compulsion?

The question about satire's persuasive capacity – is it an agent of influence or simply a reflection of public opinion? – has been and continues to be a subject of intense debate.Footnote 121 Humour's polysemic nature makes finding evidence of satire's persuasive capacity challenging, for the experience of humour depends upon audiences’ ability to reconcile incongruity, and each individual brings different understandings to the text. A century and a half later, it is all but impossible to know precisely who consumed the satirical newspapers considered in this article. As scholars of the public sphere have argued, gender, class, cultural difference and literacy all factored into access.Footnote 122 It is even more difficult to discern how the public read them and how specific satirisations shaped individual opinions. What does seem clear, though, judging from the play's resonance, is that the audience was broad.

Research on contemporary satire, especially as it relates to the relationship between satire, political participation and democratic discourse, offers a useful lens for measuring satire's impact. This research reveals that political humour in general, and satire in particular, can increase audiences’ political attentiveness, learning and rates of discussion.Footnote 123 Though they did not say so explicitly, it seems the La Pata satirists understood this: they could broaden and sustain public debates across society by drawing on the play's popularity. Prieto, Ramírez, Arias, Rivera and Zamacois turned to satire not only to forge reputations and avoid prosecution but also ‘to invigorate public debate, encourage critical thinking, and call on citizens to challenge the status quo’.Footnote 124 Satire offered a mode of critique uniquely fit for the circumstances. It was, as a journalist from the era described it, ‘the only viable genre in a context where everything is absurd’.Footnote 125 The satirists considered here hoped – and expected – to find a receptive audience for their satire and their visions for a better society.

In mid-nineteenth-century Mexico, satire formed a critical weapon in the written arsenal. Journalists and public figures used it to proffer radical critiques while strengthening dialogue and democratic discourse. Satirical renderings of Don Simplicio and La Pata de Cabra's whimsical world worked because Grimaldi's play was so well known. They also worked because contemporaries saw parallels between Grimaldi's over-the-top show and the at times farcical (real) world of mimetic insurrectionism and political coups d’état. Reflecting on the relationship between theatre and politics in 1848, Prieto had quipped, ‘Between us Mexicans, few things are more frequent or more accepted than pronunciamientos and magical comedies.’Footnote 126 And no comedia de magia was more popular than La Pata de Cabra.

An approach to the study of nineteenth-century Mexico that pays closer attention to intersections between politics and the playhouse transforms our understanding of this period, for culture and politics intertwined to produce phenomena like those which emerged around Grimaldi's play. The task of reconstructing cultural imaginaries, while painstaking, is necessary if we want to better grasp how letrados harnessed popular cultural symbols to shape, sustain and broaden political debate. Scholars of satire posit that ‘political comedy, satire, and parody all provide important narrative critiques that enable democratic discourse and deliberation’.Footnote 127 Satirists, then, offered individuals opportunities to analyse and interrogate power and politics rather than remain subjects of it. In Mexico and throughout Latin America in the nineteenth century, they drew heavily on the world of theatre. By cloaking acerbic critiques in La Pata de Cabra's absurd world, satirists probed and challenged the bounds of what could be said and written. They enticed their readers to do the same by inviting them to imagine different possibilities. At times, they were met with fines and imprisonment. At others, when administrations restricted press freedoms, they toned down their rhetoric. Nonetheless, many persevered, fighting to sustain dynamic, contentious debates in the midst of armed insurrections, foreign invasions and civil war.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the many people who read this article and offered feedback. I want to thank in particular the reviewers and editors from the JLAS; your comments, suggestions and questions strengthened this article in ways big and small. I also want to acknowledge Edward Wright-Rios, Frank ‘Trey’ Proctor, and especially Celso Castilho for their generous and incisive comments on previous drafts. I owe a debt of gratitude to Paula Covington at Vanderbilt University and Terre Heydari, Joan Gosnell and Katie Dziminski at the DeGolyer Library (Southern Methodist University) for helping me track down extant copies of some of the satirical newspapers examined in this article. Finally, I would be remiss not to thank Lauren Ingwersen, whose patience and understanding has allowed me to extend nap times, work late into the evening and periodically hide away from our two loving and energetic children to finish this article.