In memoriam Adrienne Fried Block

If relatively modest in quantity, the chamber music of Amy Beach comprised a significant body of work that confronted meaningfully the churning countercurrents animating her idiosyncratic musical style. She was a largely autodidactic composer steeped in traditions of European art music who nevertheless found ways to acknowledge her own American identity. She was a highly successful song composer who essayed the larger forms, and not at all timidly. She was a musician who, along with many of her contemporaries, lamented the relevance of Romanticism receding from the onslaught of twentieth-century modernisms. And she was a composer who, though “one of the boys,”2 owing to her association with the Second New England School, worked energetically to promote the careers of other American women composers, even as she continued to publish her own music under the authorship of Mrs. H. H. A. Beach.

This last point bears emphasis, especially in approaching her chamber works. At the turn to the new century, the genre was still largely a male-dominated domain; relatively few women found their comfort zone while expending their aesthetic creativity on string quartets, piano trios, and all the rest. One has only to recall the experience of another gifted song composer, Fanny Hensel, who produced her sole string quartet in 1834 for private consumption, only to admit that, unlike her brother, who had already published two quartets, she had been unable to work through the unfathomable late quartets of Beethoven, and that in her view her larger compositions all too often died in their youth from decrepitude.3

Between Hensel and Beach, not many women composers invested substantially in chamber music. Among the few who come to mind was Clara Schumann, whose own Piano Trio in G minor, op. 17, dates from 1846, the year before Hensel died; following it by several years were the three Romances for violin and piano, op. 22, written for Joseph Joachim and figuring frequently in their concerts together.4 The list of women after Clara Schumann who entered the lists of chamber music is not long. Three French composers who did were Cécile Chaminade (1857–1944), with a pair of piano trios; Marie Jaëll (1846–1925), with an estimable string quartet of 1875; and Louise Farrenc (1804–75), whose extensive chamber compositions range, most unusually, from duos all the way to a nonet. The Venezuelan pianist Teresa Carreño (1853–1917), to whom Beach dedicated her Piano Concerto and Violin Sonata, wrote a string quartet in 1896. English Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), who studied in Leipzig, where she met Brahms, created two sonatas in 1880, both in A minor, for violin, op. 5, and for cello, op. 7, and both were fairly enveloped by the “Brahmsian fog.”5 Smyth’s countrywoman Alice Mary Smith (1839–84) tested her mettle in piano quartets and string quartets. Finally, Swedish organist Elfrida Andrée (1841–1929) produced a violin sonata and a piano trio, quartet, and quintet, as well as string quartets.

Unlike most of the contributions of these predecessors, several of Beach’s chamber works did receive noteworthy performances during her career in the United States and abroad, especially the Romance, op. 23; Violin Sonata, op. 34; and Piano Quintet, op. 67. Nearly all of Beach’s chamber music appeared in print from her principal publisher, Arthur P. Schmidt, centered in Boston, with a branch in New York and international affiliation in Leipzig; only a few compositions were left in her musical estate for posthumous publication.6 Chronologically, this repertoire falls into three groups, of which the first concentrated on works for violin and piano: the Romance, op. 23 (1893); Violin Sonata, op. 34 (1896); Three Pieces, op. 40 (1898); and Invocation, op. 55 (1904). In the second group, Beach explored a variety of other ensembles: Piano Quintet in F-sharp minor, op. 67 (1909); Theme and Variations for Flute and String Quartet, op. 80 (1920); Suite for Two Pianos, op. 70/104 (1924); and the one-movement Quartet for Strings, op. 89 (1929). The third and final group added two late works, the Piano Trio, op. 150 (1939), and Pastorale for wind quintet, op. 151 (1942).7

I

On May 1, 1893, having delivered a short address celebrating “the growth and progress of human endeavor in the direction of a higher civilization,” President Grover Cleveland pressed a golden telegrapher’s key to complete an electric circuit and activate 100,000 incandescent lights, launching the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Among the technological innovations that enlightened, amused, and titillated fairgoers over the next six months – no fewer than some 28,000,000 visitors, a staggering two-fifths of the population of the United States – was the world’s first Ferris Wheel (meant to rival the Eiffel Tower that had dominated the Parisian cityscape during the Exposition universelle of 1889), a moving sidewalk, the elevator, the phonograph, and the telephone. Among the practical inventions making their debut were the zipper and the dishwasher, the latter the brainchild of Josephine Cochrane.

She was just one of many women who made an impact at the fair. The Board of Lady Managers, whose president was Bertha Honoré Palmer, a wealthy Chicago socialite, had commissioned the Woman’s Building, designed by the twenty-one-year-old architect Sophia Hayden, to showcase the “progress” of womankind. A number of women artists and sculptors displayed their work, among them Mary Cassatt, who, against the discouragement of her fellow impressionist Edgar Degas, contributed a 58 × 12-foot mural on the theme of the modern woman8; and the sculptor Enid Yandell, a pupil of Rodin, who created the caryatid that supported the roof garden. Amy Beach received a commission to compose a cantata, the Festival Jubilate, op. 17, performed by an orchestra and chorus directed by Theodore Thomas on the opening day before an audience of some 2,000 that thronged the Woman’s Building.9 Early in July, Beach returned to the Exposition to perform some of her piano pieces, the song “Sweetheart, Sigh No More” (the third of the Four Songs, op. 14), and the Romance in A major, op. 23, the last with Maud Powell, the first American violinist to enjoy an international concertizing and recording career.10

As Adrienne Block has suggested, the inspiration for Beach’s first chamber work was, in fact, “Sweetheart, Sigh No More,” though likely few at the time realized the connection.11 Set to a text by Thomas Bailey Aldrich,12 editor of the Atlantic Monthly from 1881 to 1890, this modified-strophic, sentimental love song falls into three sections (A, A’, A”) that progressively recall and expand to a climax the refrain-like line, “Sweetheart, Sigh No More,” which concludes each of the three five-line stanzas. Here is the first stanza of Aldrich’s poem and, for comparison, the beginnings of Beach’s song and Romance (Examples 7.1 and 7.2).

Example 7.1 Beach, “Sweetheart, Sigh No More,” op. 14, no. 3, mm. 1–6.

Example 7.2 Beach, Romance, op. 23, mm. bars 1–6.

Without much difficulty, one can perceive similarities between the two settings: they share, for instance, a rising melodic line defined rhythmically as three-eighths, dotted quarter, and eighth. That said, though, the Romance impresses as a recast version of the song. While the vocal line commences on its tonic keynote (f’) and progresses through scale degrees 2, 3, and 5 (g’, a’, c”), the violin melody begins on its fifth scale degree (e’) and climbs through scale degrees 6 and 7 (f♯’, g♯’) before reaching, via an appoggiatura on b’, 8 (a’). What is more, the instrumental melody unfolds in three consecutively expanding gestures that span, in turn, a fifth (e’–b’), sixth (f♯’–d”), and seventh (a’–g♯”), presaging Beach’s later manipulation and expansion of register in the concluding section of the piece, in which the violin plays its melody beneath the piano, which offers a murmuring accompaniment high above with pianissimo tremolos.

Like the song, Romance falls formally in three parts, though the second (animato) is sufficiently modulatory and developmental in character to suggest a contrasting middle section, yielding a ternary form (ABA’) for the whole, as opposed to the essentially strophic patterning of the original song. In the B section of the instrumental reworking, Beach explores third relationships, in particular the lower thirds F major and F-sharp major, more extensively than in the song, where the tonic F major is only briefly juxtaposed with D-flat and A-flat major, that is, thirds below and above the tonic. More subtle to trace is the relationship between the violin part and the vocal part. Initially, Aldrich’s poetry does map conveniently onto the Romance so that, for instance, we may readily underlay “It was with doubt and trembling” beneath the violin entrance, encouraging us in effect to hear op. 23 as a Lied ohne Worte. But within a few bars, any imagined vestiges of a text disappear, while the music asserts its autonomous character as an abstract piece for violin and piano.

With the Violin Sonata, op. 34, Beach produced a major chamber work that freely acknowledged its nineteenth-century European roots – first and foremost, Brahms; to a lesser extent Liszt, in Beach’s use of thematic transformation and certain piano figurations; Wagner, in her application of chromatically saturated textures, especially in the slow movement; and perhaps also Dvořák, in her intimations of folk music in the second-movement scherzo. The sonata dates from 1896, just months before the passing of Brahms in April 1897. From the outset, Beach’s score absorbs the modally infused late style of Brahms; indeed, not insignificant portions of her sonata seem to privilege modal versus tonal formations and relationships. If we consider, for instance, just the keys of the four movements – A minor, G major, E minor, and A minor (ultimately ending in the parallel major) – we see that the lowered seventh degree, a characteristic marker of the Aeolian mode, is tonicized in the second movement. In addition, several themes of the sonata tend to avoid the raised in favor of the lowered seventh scale degree and also feature the Phrygian half-step E–F, that is, in terms of the Aeolian mode, the fifth scale degree supported by its upper neighbor. As in the late music of Brahms,13 these modal flavors afforded Beach viable alternatives to the well-trodden terrains of late nineteenth-century tonality, increasingly perceived, as the century’s end neared, as having been stretched to its limits.

A case in point is the opening theme of the first movement, presented in stark pianissimo octaves, which analyze more convincingly as a modal rather than tonal gambit (Examples 7.3a and 7.3b). As the reduction in Example 7.3b illustrates, this theme divides the octave into the fifth and fourth (a–e’–a’), with the fifth scale degree embellished by its diatonic neighbor notes, d’ and f’.

Example 7.3a Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/I, mm. bars 1–7.

Example 7.3b Reduction.

Significantly, Beach initially avoids the seventh scale degree; its first appearance occurs in bars 5 and 6, as the (lowered) g♮’, an inner voice of the mediant C-major harmony. All these calculations have the effect of postponing until bar 14 the first, brief arrival of the dominant with its raised leading tone, G♯. But the onset of the Animato in bar 33, marking the transition to the second theme, now accommodates more compellingly a hybrid modal/tonal, if not tonal reading. Thus, the lowered seventh degree does return as a bass pedal point, but in tonal terms, as V/III, seemingly in order to prepare for a second theme in the mediant C major. Beach sidesteps this anticipated progression, however, so that when, moments later, the second theme emerges, it does so in a luminous E major, moving us securely into a tonal orbit around the dominant (Example 7.4).

Example 7.4 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/I, mm. 63–71.

The first movement offers other instances of modal/tonal exchanges, as at the end of the exposition, where the expected close in E major yields instead to a modally tinged E minor. Similarly, in the recapitulation Beach obviates the effect of the returning second theme in A major by recalling at the end of the movement its Aeolian opening, as if to remind us of the crepuscular, modal origins of the sonata. These modal/tonal ambiguities inform, too, the late music of Brahms, likely a primary influence on Beach’s op. 34. One need look no further than the start of Brahms’ Violin Sonata in D minor, op. 108 (1888), where our sense of “D minor” arguably rather suggests transposed Aeolian on D, with its lowered leading tone, C♮. Or, the beginning of the Clarinet Sonata in F minor, op. 120, no. 1 (1894), where the theme describes a descending form of the Phrygian mode transposed to F. Or, to choose three of Brahms’ later compositions in A minor: the Intermezzo, op. 76, no. 4 (1878), Double Concerto, op. 102 (1887), and Clarinet Trio, op. 114 (1891), all of which highlight the lowered G♮ and thereby invoke the Aeolian mode.

As mentioned earlier, the second movement, in a ternary ABA’ scheme, offers a scherzo in G major (with a trio in the parallel minor), thus elevating the natural seventh scale degree to prominence, but now in a tonal context. The scherzo does not exactly begin in G major, however. Rather, the first two bars describe a falling figure that outlines an A-minor triad in imitative counterpoint before pivoting toward G major (Example 7.5).

Example 7.5 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/II, mm. 1–5.

With the key signature of one sharp, this A-minor opening actually seems to draw on the transposed Dorian mode on A (i.e., A, B, C, D, E, F♯, G, A), which, through a simple process of rotation, readily transforms itself into G major, beginning in bar 3, where the bass of the piano establishes G as the tonal foundation. Beach’s conceit thus links the scherzo to the first movement, so that its close in the Aeolian mode gives way, if only momentarily, to transposed A-Dorian before turning to a tonal organization and confirming G major as the key of the scherzo. Here the F♯, which replaces the F♮ of the first movement, is a critical pitch that plays two roles – first as the raised sixth of A to impart a Dorian character, and then as the leading tone to G major. In a similar way the spectral trio, putatively in the parallel G minor, creates enough tonal uncertainty through its use of the lowered seventh degree to tempt us to hear parts of it as G-Aeolian, or at least as a tonal/modal hybrid (Example 7.6).

Example 7.6 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/II, Più lento, mm. 1–3.

These evocative mixtures are not dissimilar to what Chopin had explored in his Nocturne in G minor, op. 15, no. 3, of 1833, which similarly resists fitting comfortably within its assumed key, owing again to the prominence of the lowered seventh degree and strategic placement of chromatic pitches that challenge the tonal identity of the piece.

Chromaticism weighs heavily on the third movement (Largo con dolore) of Beach’s sonata, one of her most heartfelt creations and the emotional high point of the work. Granted, the movement begins securely enough in E minor, but as we proceed further, the dense chromaticism more and more loosens the tonal moorings of the music, effectively setting us adrift in Wagnerian currents that evade tonal closure by means of strategically placed deceptive cadences. Example 7.7 illustrates one such cadence that seems intended to revisit the shifting tonal tides of Tristan und Isolde.

Example 7.7 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/III, mm. 14–15.

And yet, by the end of the Largo Beach again betrays her affinity to Brahms. The surprise turn to E major in the closing bars allows the composer to revive some modal associations that bring to mind the Andante moderato of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, op. 98 (1886), celebrated for its initial horn solo in the Phrygian mode, brought back in its closing bars, as shown in Example 7.8a.

Example 7.8a Brahms, Symphony No. 4, op. 98/IV, mm. 113–18.

Five bars from the end of her movement, Beach appears to allude in the high violin tessitura to this horn call, featuring the lowered sixth and leading tone (C and D) as the piano climbs in gently quivering tremolos grounded in E major (Example 7.8b).

Example 7.8b Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/III, last six measures.

From this fading welter of sound we may extract a mixed mode on E (E–F♯–G♯–A–B–C–D–E), in which the first tetrachord supports E major, while the second favors a Phrygian hearing. As in Brahms’ symphony, modal mixtures thus help to create a spellbinding, iridescent conclusion that plays at the borders between tonality and modality.

Just as Beach found a way to link the scherzo to the first movement, so too does she connect the finale to the slow movement, in this case through an energetic transition. Its purpose is to redefine the placid E-major close of the Largo as the invigorated dominant-seventh of A minor (V–V7–i). Here Beach draws on precedents of several nineteenth-century composers. One thinks, for instance, of the finale of Mendelssohn’s Cello Sonata in D major, op. 58 (1843), or the complex finale of Brahms’ Piano Quintet in F minor, op. 34 (1865), both of which use transitions to introduce their final movements. When Beach’s first theme arrives thirteen bars into the finale, we encounter a tonal/modal mixture that again may be read alternately in A minor or the Aeolian mode (Example 7.9).

Example 7.9 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/IV, mm. 13–16.

Appropriately enough, this theme impresses as derived from the Aeolian theme of the first movement (cf. Example 7.3a), which partitions the octave into the fifth and fourth, the difference between the two themes being that in the finale, Beach partially fills in the fifth with a stepwise ascent to the third scale degree (A, B, C, E). Note also that the ornamentation of the fifth degree, E, with its upper neighbor, F, is now transferred to the busy tremolos of the piano accompaniment. Throughout the course of the finale, Beach’s primary theme undergoes metamorphoses not unlike the thematic transformations conjured by Liszt or what Arnold Schoenberg would later describe as the developing variations of Brahms. Thus, we may comprehend the lyrical second theme (Example 7.10) as a distant cousin of the opening theme – here Beach expands the original outline of a step and third (A B A C) slightly to accommodate a fourth (D E D G).

Example 7.10 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/IV, mm. 47–51.

A more straightforward transformation of the first theme occurs in the fugato marking the beginning of the development (Example 7.11). In this case, Beach was perhaps recalling a similar procedure applied by Liszt in the fugato of his Piano Sonata (1853), the subject of which openly derives from the introductory bars of that work. But for the American theorist/pedagogue Percy Goetschius, in the main Beach followed “the methods of development peculiar to Brahms.”14 Was Goetschius referring to how she developed her themes, how she applied modal mixtures, or perhaps to other techniques? He did not elaborate further, though as we shall see, Beach would find other opportunities to indulge her Brahmsian pursuits.

Example 7.11 Beach, Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 34/IV, mm. 97–102.

Her next two chamber compositions, the Three Pieces, op. 40 (1898), and Invocation, op. 55 (1904), are both small-scale creations that return us to the songlike character piece represented by the earlier Romance. Precious little is known about their inspiration or early history. Of the three titles for op. 40 – La Captive, Berceuse, and Mazurka – Nos. 2 and 3 refer to well-established genres through several common markers, whether the muted, rocking rhythms and stable pedal points of the berceuse, or the rustic gestures and drones of the Polish peasant folk dance. But in the cases of La Captive and Invocation, the sources for the titles remain unclear, so we are left to our own devices to interpret them. La Captive, at least, does encourage some speculation. It may be that here Beach was alluding to Victor Hugo’s poem of the same name from Les Orientales (1829), a collection, in Graham Robb’s pithy summary, “set in a Never-Never Land which resembled Spain, Algeria, Turkey, Greece and China, and called itself ‘The East’.”15 Beach responded by restraining the violin part throughout to the G-string of the instrument, “freeing” this captive only in the final bars through an arpeggiated series of ethereal, ascending harmonics.

II

In 1908, when Beach turned to the vaunted genre of the piano quintet, she would have been intimately familiar with the exemplars of Robert Schumann (1842) and Brahms (1864), both of which she performed with the Kneisel Quartet, and probably also those of Franck (1879) and Dvořák (1887). All of these save the Dvořák use prominent cyclical thematic techniques, whereby material from the first movement reemerges in transformed guises in the finale (Schumann and Brahms) or second and third movements (Franck). Beach followed suit by recalling the mysterious prefatory Adagio of her quintet late in the finale, just before the coda, and spirited Presto leading to the radiant ending in F-sharp major. But in this case the construction of her Adagio, which unfolds a descending chromatic tetrachord (F♯, F♮, E, D♯, D♮, C♯), betrays the strong influence of Brahms’ quintet, with which we may hear Beach’s score to be in dialogue.

Beach would have noticed, for instance, that the initial bars of Brahms’ op. 34 describe a tetrachordal Dorian descent from F through E♭, D♮, and C (Example 7.12a), and that subsequently the same perfect fourth is filled out chromatically (F–E♮–E♭–D♮–D♭, and C; Example 7.12b), a centuries-old topical reference to the lament (passus duriusculus).

Example 7.12a Brahms, Piano Quintet in F minor, op. 34/I, mm. 1–4, and reduction.

Example 7.12b Brahms, Piano Quintet in F minor, op. 34/I, mm. 12–16, and reduction.

This motive of the composed-out fourth provided Brahms with several options for later use in his quintet – for instance, the half-step D♭–C, highlighted especially in the jarring Phrygian cadence at the end of the scherzo. Of particular relevance to Beach, though, was the second theme of his finale, also derived from the chromatic tetrachord, and the apparent inspiration for the first page of her quintet (Example 7.13).

Example 7.13a Brahms, Piano Quintet in F minor, op. 34/IV, mm. 252–60.

Example 7.13b Beach, Piano Quintet in F♯ minor, op. 67/I, mm. 1–24.

In a remarkable transformation, Beach reworked this tetrachord, now transposed up a step to span the fourth F♯–C♯, into a new, tonally destabilized form. The reduction in Example 7.14 shows how.

Example 7.14 Reduction of Example 7.13b.

She begins by assigning the violins and viola a stationary, high pianissimo unison F♯ that seems to emerge ex nihilo, as if to assert that in the beginning was the unmediated, uninterpreted pitch F♯. Against it the piano erupts from below with a series of arpeggiated dissonances – first a French augmented-sixth chord, then a IV7 chord, and finally an embellished augmented triad, none of which clarifies our sense of F-sharp minor. The strings then repeat their unison, unharmonized pedal point and commence a craggy chromatic descent clearly modeled on the theme from Brahms’ finale (cf. Example 7.13a). This descent actually overshoots its goal, for it extends the tetrachord by one step to fill out the tritone F♯–B♯. From this point, the downward stepwise motion continues in unison with the natural diatonic version of F-sharp minor before ultimately coming to rest on the dominant. The half cadence on C-sharp major is, notably, the only consonant moment in the slow introduction. In short, Beach has thwarted our sense of a tonic so that instead of an F♯-minor triad we hear just the pitch F♯, isolated and suspended in a high, rootless register, where it blends with the swirling dissonant arpeggiations accumulating below. From a tonal perspective, the effect of the whole Adagio is thus to begin in medias res, setting us down in an unpredictable sea of chromatic sonorities from which we slowly drift toward the relative stability of the dominant.

Notwithstanding her clear debt to Brahms, the abstract model behind Beach’s Adagio is ultimately that of the historical slow introduction, traditionally understood to begin (securely) in the tonic and then to modulate and pause on the dominant, not infrequently via a stepwise descent, whether diatonic or chromatic.16 By literally upending a stable opening on the tonic, Beach acknowledges the critical juncture at which tonality had arrived. Indeed, it is more than fitting that her quintet was exactly contemporary with another chamber work in F-sharp minor, the Second String Quartet, op. 10, of Arnold Schoenberg, which, ironically, did begin with a stable F♯-minor triad, though, of course, it would end with a phantasmagoric vision of Stefan George’s poem “Ich fühle Luft von anderem Planeten” (“I feel a fragrance from another planet”), the new “pantonal” world that Schoenberg would fearlessly explore the very next year in his Drei Klavierstücke, op. 11.

Of course, Beach never committed to that salto mortale, though her modification of Brahms’ tetrachord afforded her a viable way to explore a fully saturated chromaticism that, in turn, had direct implications for her understanding of tonal relationships. And so, the first theme of the exposition uses a variant of the tetrachordal figure in the first violin, with the tonic pitch now transposed to the deep bass of the piano, as if to grant it structural weight, even though Beach fills the space between with rustling, mostly dissonant piano sextuplets, few of which actually touch on the tonic harmony (Example 7.15).

Example 7.15 Beach, Piano Quintet in F♯ minor, op. 67/I, mm. 25–28.

Eventually this first thematic group evaporates into diminished-seventh chords in the high register, and we proceed to the second theme, which, surprisingly enough, materializes in B major, that is, the subdominant (Example 7.16).

Example 7.16 Beach, Piano Quintet in F♯ minor, op. 67/I, mm. 73–79.

The new theme appears in the middle register of the piano in a texture reminiscent of Brahms’ nostalgic use of the so-called three-hand technique.17 Above we hear repeated statements of f♯’’’, the tonic pitch from the slow introduction that Beach now recasts as the fifth scale degree of the subdominant. She does not linger long before leading her new theme through a series of quick modulations that include the submediant D major, so that for a moment we might understand B major and D major as forming a pair of third-related tonalities. Nevertheless, the exposition does conclude in the subdominant, with references to the fourth B–F♯, and, again, the high treble f♯’’’.

Now if we pause to consider the tonal trajectory of the exposition, we begin to apprehend its overarching unity. By modulating to the subdominant, instead of, say, the mediant or dominant, Beach reinforces the tetrachordal foundations on which this music rests. That is, the Ur-tetrachord of the Adagio, F♯–C♯ (extended through B♯ to the tritone) is complemented and “completed” in the exposition by its mirror tetrachord, B–F♯ (Example 7.17).

Example 7.17 Beach, Piano Quintet in F♯ minor, op. 67/I, tetrachordal summary.

Taken together, the two symbolically span the total chromatic and help to explain the restless, searching quality of the quintet, which visits ever so briefly any number of keys while minimizing if not avoiding altogether unambiguous statements of the tonic triad until the final cadence of the movement. For Beach, tonality is still understood as a teleological process – F-sharp minor is the goal of this movement and is ultimately attained in its closing bars, though the narrative of how she accomplishes that is anything but predictable, as most of the expected or familiar tonal anchoring points in the movement are weakened or occluded, if not removed.

It is well known that at an early age Beach displayed not only perfect pitch but pronounced signs of synesthesia, through which she associated particular keys with colors.18 In her musical palette, F-sharp minor was a black key. In contrast, D-flat major, the key of the second movement of the quintet, aroused for her softer hues of violet. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, she created here a lushly romantic movement firmly centered on D♭, enharmonic equivalent of the C♯ of the first movement. The Adagio espressivo opens straightaway with a yearning theme in the muted strings, an eight-bar period that divides symmetrically into two four-bar phrases, the second stretched a bit by a brief metrical change from 4/4 to 6/4 (Example 7.18), as if to suggest an expressive rubato.

Example 7.18 Beach, Piano Quintet in F♯ minor, op. 67/II, mm. 1–8.

The theme appears subsequently in the piano, and then in the second violin a minor third above, in E major, before the cello introduces a second theme in B-flat minor, a minor third below the tonic. These third relationships return us to the realm of late Romantic tonality, as Beach rapturously redirects her gaze backward, to revive a fleeting, autumnal vision of the musical past from which she had first drawn her musical nourishment.

It remains then for the finale to reconvert the D♭ to C♯ in a brusque transition that launches the movement (Allegro agitato). The function of C-sharp major as the dominant is now in focus and reinforced, so that the movement ultimately can conclude in F sharp, not in the veiled, chromatically clouded minor of the first movement, but in its triumphant major form. Along the way, Beach introduces and develops themes that derive from the tetrachord of the first movement, including, toward the end of the development, a fugato with a tonal answer that chisels out the telltale fourth, F♯–C♯, all in preparation for a dramatic ascent and pause. From the silence emerges once again the Adagio of the first movement, with the high, disembodied F♯’’’ suspended above. The final unwinding of the tetrachord then transpires in the spirited coda, where we hear in succession seven dissonant chords that accompany the chromatic descent F♯, E♯, E♮, D♯, D♮, C♯, and C♮ (Example 7.19).

Example 7.19 Beach, Piano Quintet in F♯ minor, op. 67/III, mm. 311–14.

Its continuation, ultimately moving through B to A♯, provides the final steps that convincingly affirm the tonal paradigm of dominant-tonic and bring this rich work to its close. All that remains unanswered is which color in the end supplants the black and violet of the first two movements.

III

Among Beach’s least-known chamber work is the unjustly neglected Suite for Two Pianos (Founded upon Old Irish Melodies), released in 1924 as her op. 104. We do not know for certain, but a reasonable hypothesis is that the composition at least drew upon an earlier two-piano work titled Iverniana, which Beach had performed in 1910. She went as far as to assign the opus number 70 to that duet, but never published it; subsequently the manuscript disappeared, and no trace has yet emerged. What has come down to us as the Suite, op. 104, is in four movements, two of which have programmatic titles: Prelude (E minor), “Old-Time Peasant Dance” (E minor), “The Ancient Cabin” (A-flat major), and Finale (E minor/major). The predominance of the key of E minor, use of the lowered seventh scale degree and pentatonic formations, and appearance of Irish folk melodies or imitations thereof recall the composer’s “Gaelic” Symphony, premiered in Boston in 1896. In turn, that linkage encourages us to revisit briefly the celebrated controversy about American music precipitated by another symphony in E minor, Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony, premiered in 1893 at the newly finished Carnegie Hall in New York.

In an interview appearing in the New York Herald on May 21, 1893, Dvořák had argued that the future of American music “must be founded upon what are called negro melodies.” The pentatonic slow movement of his symphony was understood to simulate African American spirituals, and in fact its haunting English-horn melody would later enjoy an afterlife as the spiritual “Goin’ Home.” Nevertheless, among the early reactions to the “New World” Symphony were these private comments of Beach, who found Dvořák’s music to “represent only the peaceful side of the negro character and life. Not for a moment does it suggest their sufferings, heartbreaks, slavery.”19 Dvořák later revised his views to take into account Native American music as a second repository of folk materials available to composers, and shortly before leaving the United States in 1895 to return to Prague went a step further: “It matters little whether the inspiration for the coming folk songs of America is derived from the negro melodies, the songs of the creoles, the red man’s chant, or the plaintive ditties of the homesick German or Norwegian. Undoubtedly, the germs for the best of music lie hidden among all the races that are commingled in this great country.”20

Unlike Dvořák, whose symphony “hinted at an exotic otherness that listeners were supposed to intuit as American,”21 Beach confirmed her Gaelic/American sympathies by specifically labeling her symphony and citing several folk melodies excerpted from a series of articles about Irish music published in the Dublin-based Citizen of 1841.22 Of interest to us here is that when composing the Suite, op. 104, she returned to the same source and chose four additional Irish melodies for reuse, one for each movement. In order of appearance, they are: 1) “Song of Sleep” (Lullaby), 2) Irish dance, 3) “Molly St. George,” and 4) a traditional Irish fiddle tune.23 Adapting them for her suite, Beach transposed three to different keys. The “Song of Sleep,” transmitted in a tonally ambiguous setting oscillating between C minor and E-flat major, she reworked to E minor/major, but left unchanged the Irish dance in E minor. Then, she transposed “Molly St. George” a fourth above from E-flat to A-flat major, and the tune for her finale a fifth above from A minor to E minor, ending in E major. Three of the four movements thus privileged E minor, the prevalent tonality of Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony. In the case of the second movement (“Old-Time Peasant Dance”), Beach was perhaps intent upon providing an alternative to Dvořák’s irrepressible symphonic scherzo, thought by some scholars to have been his musical realization of a Native American dance described in Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha (1855). In effect, Beach shifted the locale from the southern shore of Lake Superior for Dvořák’s score to Gaelic “pagan mid-summer-nights’ feasts” for her own, during which “the mad priests and votaries of Baal danced …, whirling round their bonfires.”24

Though Beach often drew upon traditional materials from the “Old World” to celebrate local color – witness, for example, the piano Variations on Balkan Themes, op. 60 (1904) – she also explored music of the Alaskan Inuit natives in her search for an exotic American “Other.”25 Here Beach was allying herself with the so-called Indianist movement, which had produced visions of an “imaginary Native America steeped in an imaginary past”26 in works such as Edward MacDowell’s orchestral Indian Suite, op. 48 (1892),27 and in the lecture-recitals and publications of Arthur Farwell, who founded the Wa-Wan Press in 1901 in an effort to promote composers who incorporated Native American musical materials into their work.

An early example of Beach’s interest in the topic of Native American culture is her part song for female choir “An Indian Lullaby,” op. 57, no. 3, of 1895. In this case, neither the text, which speaks of a soft forest bed of pine needles, nor the music, which begins in a lilting, modally colored A minor but ends in the parallel major, actually appears to draw on authentic Native American materials. Rather, the composition reflects the gaze of Amy Beach as she searches for an idealized American exoticism while still employing primarily Western musical techniques (Example 7.20).

Example 7.20 Beach, “An Indian Lullaby,” op. 57, no. 3, mm. 1–4.

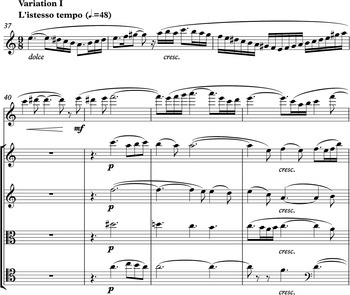

Be that as it may, in 1920 Beach returned to her part song and reused it as the basis for her Theme and Variations for Flute and String Quartet, op. 80. Following the presentation of the part song by the string quartet, the flute enters with a brief cadenza that features augmented seconds, effectively identifying the instrument as the Native American protagonist (Example 7.21).

Example 7.21 Beach, Theme and Variations, op. 80, Variation 1, mm. 37–43.

In the first variation the flute projects a high cantilena, like a spontaneous improvisation suspended above, while the string quartet adheres below more closely to the theme. There then follow a contrapuntal second variation and a third in the style of a slow, morbid waltz, both markers of Western musical topics, neither of which, however, fully engages the spectator-like flute. Only in the fourth variation, a fleet-footed scherzo for the string quartet that shifts the key signature from A minor to F-sharp minor, does the flute begin to sing strains from the original theme above the string ensemble, all preparatory to the emotional crux of the composition – the exquisite, searing fifth variation in F-sharp major. Here the flute finally enters fully into the conversation of the quartet, as Beach resorts to her most passionate, chromatic, late-Romantic style, matched in intensity possibly only by some passages in her Piano Quintet (Example 7.22).

Example 7.22 Beach, Theme and Variations, op. 80, Variation 5, mm. 51–54.

But, as if turning back from this unusual symbolic alliance of two different musical worlds, she then leads us through a foreshortened reprise of the scherzo to the Tempo del Tema, with its relatively monochromatic theme in A minor and cadenza-like response from the flute. The ultimate sixth variation brings one more Western “artifice,” a fugue on a subject fashioned from a portion of the theme. Here the flute participates equally with the string quartet in dispatching a five-voice fugue, though its frenzied course toward A major is abruptly cut short. In the final page Beach comes full circle to the original modal theme and allows the flute to have the final comment with a hushed reference to its cadenza.

If the Theme and Variations offer an idealized meeting of two different musical cultures, a meeting admittedly still beholden to the Western musical hegemony, Beach progressed to the next step by directly integrating authentic Inuit melodies into a major chamber work, the one-movement String Quartet, finished in 1929.28 This quartet was one of her few compositions she was unable to see through the press; indeed, not until 1994 did the first edition appear.29 The result was a singular admixture of three modal Inuit melodies, each introduced against the backdrop of an intensely chromatic, dissonant language that also framed the composition in an introduction and coda best described, perhaps, as music in search of a tonal center. Ultimately Beach found it in the final cadence, in which an amorphous augmented triad slips almost imperceptibly into a G-major sonority, providing closure to this experimental work. The peripatetic fourteen-bar introduction, much of which returns in the coda, offers Beach at her most dissonant: these bookends represent her realization, as it were, of Schoenberg’s schwebende Tonalität, or “suspended tonality.” Here she explores a tonally decentered, weightless realm with eerie pianissimo altered chords – nearly all dissonant – and sliding chromatic lines that situate us somewhere in twentieth-century modernity and the crisis of tonality (Example 7.23).

Example 7.23 Beach, String Quartet, op. 89, mm. 1–14.

When, after a brief silence, the first Inuit melody appears in the viola, it enters initially as unadorned monophony, as if some vision of a preternatural, uncorrupted past unaffected by musical modernity, before then being swept up in the swirling chromatic polyphony of the ensemble. Beach’s strategy seems to be to contrapose the modern with the ancient – the European string quartet with its rich associations of contrapuntal thematic working out initially collides with the timeless, indigenous single-line music of the American Inuit. Thus, the third Inuit melody generates the subject of an unconventional fugue, the center of a symmetrical arch form (Introduction ABCB’A’ Coda) not unlike the paradigms employed by Bartók in his string quartets. And just as Bartók joins elements of folk music to a modernist style, so too does Beach create a new alliance of binary opposites – for instance, of modality vs. suspended tonality, or monophony vs. polyphony (Examples 7.24a and b).

Example 7.24a Beach, String Quartet, op. 89, mm. 15–19.

Example 7.24b Beach, String Quartet, op. 89, mm. 263–74.

But, in the end, the two sides meet halfway with a serene G-major sonority that at once resolves the accumulated dissonance of the whole and reimagines the limits of a modal musical universe, a compelling example of the new path Beach was beginning to explore in her later music.

IV

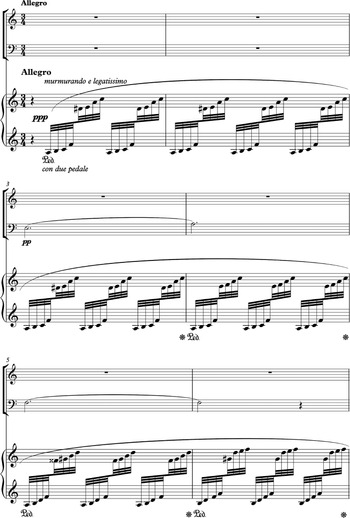

Beach would return to chamber music on two more occasions. The short Pastorale, op. 151, is a late recasting from 1941 for wind quintet of a modest earlier work for flute, piano, and cello. A far more substantial offering, one that conveniently summarizes the contrasting directions we have been tracing in her chamber music, is the Piano Trio in A minor, op. 150, composed in just two weeks in June 1938. In her diary Beach noted that she was creating the trio out of “old materials,” and indeed the result arguably represents her most eclectic creation, incorporating, in Adrienne Block’s estimation, “French modern, late Romantic, and folk elements, perhaps guided by narrative concerns.”30

The first movement begins with swirling, ppp arpeggiations in the piano that project ambiguity in two ways. First, while the A-minor triad is embedded in the figurations, so too are the “outlier” pitches B, F, and D♯, creating a blurred, dissonant harmonic effect sometimes tending toward whole-tone formations, and indeed reminiscent of Beach’s impressionist piano character piece of 1922, “Morning Glories,” op. 97, no. 1. Second, the figure begins in the middle of a 3/4 bar, so that metrically speaking, we are not on terra firma until a bar and a half later, when the cello introduces the modal first theme on the downbeat in dotted halves (Example 7.25).

Example 7.25 Beach, Piano Trio, op. 150/I, mm. 1–6.

The more tranquil, expressive second theme follows in E-flat major (enharmonically D-sharp) and B major, two keys drawn from the anomalous pitches of bar 1 that again favor whole-tone associations, though on the local level Beach’s harmonic language continues to drift in the chromatically saturated tonal style associated with post-Wagnerian tonality.

Perhaps this retrospective quality explains her decision to base the outer sections of the slow movement (Lento espressivo) on her setting of Heinrich Heine’s “Allein,” op. 35, no. 2 (1897), an intense composition that looks back to the lofty subjectivities of German Romanticism, with treatments of the same, trenchant verses by Schubert (“Ihr Bild” from Schwanengesang, 1828), Clara Schumann (op. 13, no. 1, 1844), and the young Hugo Wolf (1878). Heine’s text concerns a portrait of a deceased lover who seems to come to life. Quite in opposition to Beach’s nostalgic return to the German Lied in the “black” key of F-sharp minor (Example 7.26a) is the central portion of the movement, a playful scherzo in the parallel major, inspired by an Inuit melody, The Returning Hunter (Example 7.26b), that Beach had first explored in her suite for children, Eskimos, op. 64, no. 2, from 1907:

Example 7.26a Beach, Piano Trio, op. 150/II, mm. 1–3.

Example 7.26b Beach, Piano Trio, op. 150/II, mm. 33–42.

Beach thus pairs an art song with a vernacular folk song in a combination of a slow movement and scherzo, an arrangement that recalls Brahms’ similar formal approach in the Violin Sonata No. 2 in A major, op. 100.31

Adrienne Block has surmised that the energetic finale was inspired by yet another Inuit melody, “Song of a Padlimio,” which Beach could have discovered in a monograph by anthropologist Franz Boas, The Central Eskimo (1888).32 Propelled by a compact ostinato figure spanning the thirds below and above A (A–G♯–F♯–G♯–A–B–C♯–B; note the reference to the F-sharp minor of the second movement), the movement features two themes, of which the first, in A major, appropriates pentatonic contours and syncopations pointing to folk song, while the second, in D-flat major, again lapses into Beach’s lyrical, romantic vein.

In the end, it seems, Beach was content to juxtapose and celebrate musical opposites and to suggest, but not insist upon, their interrelationship as she pursued her distinctive vision of American music. It was a dynamic vision of leavening practices drawn from familiar nineteenth-century European music with relatively little explored but fertile resources of an American musical Other. It was, finally, one vision of many for the establishment of a viable twentieth-century American style that would combine elements of high art and vernacular traditions – a vision, to be sure, “worthy of serious attention.”