INTRODUCTION

April 20, 2013, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake hit Lushan County in southwestern China's Sichuan province. The Red Cross Society of China (RCSC), a national humanitarian social relief organization supported by the central government and operated by the Ministry of Health, was supposed to be a leader in fundraising and disaster relief. However, the lack of public confidence in RCSC became painfully clear after a series of scandals in 2011. Footnote [1] In the first 24 hours after the earthquake, which is usually considered to be the prime time for fundraising, RCSC only raised a paltry $23,000 in private donations. This is in sharp contrast to $3 million raised by One Foundation (OF). The OF, previously run under the umbrella of RCSC, became the first independent charity foundation in China on January 11, 2011. Ever since, the OF outperformed RCSC in disaster relief and charity activities. The sharp contrast between these two organizations stirred wide discussion in domestic and international discourses, focusing on the credibility crisis of RCSC and the increasing recognition and credibility gained by OF.

Obtaining credibility and legitimacy raises daunting challenges for a new organizational form like OF. Although founded by a world famous actor – Jet Li – OF suffered many difficulties from early establishment to the stage of obtaining its public and independent fundraising status. To accomplish its social mission, OF needed not only to navigate through state's strict regulations, but also to develop an autonomous and sustainable model. As social enterprises need to cope with incompatible demands and prescriptions (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013), the process of OF's creation and legitimation involves dealing with highly incompatible demands imposed by multiple institutional constituents such as state, civil society, and market.

This study aims to investigate the creation process of the OF in China's charity field where multiple and contradictory institutional logics coexist and compete. Institutional logics are ‘socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs and rules’ (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio1999: 804). They provide sets of principles and beliefs that prescribe appropriate behaviors for actors to achieve their goals (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and Dimaggio1991; Thornton, Reference Thornton2002). Incompatible logics generate tensions where actors need to carry out integrative and adaptive coping strategies (Greenwood, Diaz, Li, & Lorente, Reference Greenwood, Diaz, Li and Lorente2010; Yu, Reference Yu2013). Although previous studies have emphasized the importance of blending competing logic during the process of creating social enterprises (Galaskiewicz & Barringer, Reference Galaskiewicz, Barringer, Gidron and Hasenfeld2012; Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013; Tracey, Phillips, & Jarvis, Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011), we find this literature is insufficient to explain the case of OF.

First, extant research mainly focuses on the contest and integration between two logics – market logic and social mission logic – in Western developed societies. Few research studies have been conducted in transitional economies or developing countries where a larger number of logics coexist and compete (Goodrick & Reay, Reference Goodrick and Reay2011; Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Taking China as an example, in addition to dealing with these two logics, social organizations have to struggle with restrictive regulations posed by a state-centric political system – reflected as the state logic – and strive to increase autonomy and encourage civic engagement – reflected as the civil society logic (Lan & Galaskiewicz, Reference Lan and Galaskiewicz2012; Zhao, Reference Zhao2012). As the number of logics and the degree of incompatibility among these logics increase, OF faces heightened challenges (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011), thus posing an intriguing puzzle regarding OF actors’ responses.

Second, recent studies have explored how actors engage in institutional work as a coping strategy to deal with institutional multiplicity and change existing institutions (Coule & Patmore, Reference Coule and Patmore2013; Greenwood, Suddaby, & Hinings, Reference Greenwood, Suddaby and Hinings2002; Rojas, Reference Rojas2010). Yet, these studies mainly look at elite and/or powerful actors who have sufficient resources and capabilities as prerequisites for initiating changes (DiMaggio, Reference Dimaggio1988; Fligstein, Reference Fligstein1997). We know little about how actors may learn to use and accumulate resources in devising and advancing institutional work. Specifically, what is missing is a temporal perspective in understanding how actors develop their resources and capabilities to deal with multiple logics in different organizational stages to gradually accomplish their organizational goals.

This study addresses these gaps by analyzing OF's creation and legitimation process. Using the findings merged from various sources of data, we bracket OF's creation and legitimation process into four organizational stages – idea gestation, piloting, adjusting, and transformation. We then show, in each stage, what are the major institutional constraints and logic conflicts and how actors deploy resources to enact institutional work and develop their capabilities to achieve their organizational goals. This study makes three important contributions. First, it provides empirical evidence of how institutional multiplicity provides opportunities for discretionary action and organizational innovation. This paper proposes paying more attention to understanding how actors expand their repertoire of responses and even take advantage of logic multiplicity to negotiate a novel organizational form. Second, this study contributes to the institutional work and social entrepreneurship literature by theorizing a temporal model to illustrate the dynamic relationships among the organizational stage, institutional work, and resources and capability development. Third, this paper sheds lights on the processes and strategies that drive innovation in China's non-profit sector.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Institutional Work as a Coping Strategy to Conflicting Institutional Logics

When creating a new organizational form in an environment where competing logics impose critical challenges, actors need to enact institutional work to integrate logics (Yu, Reference Yu2013). The concept of institutional work underlines the need for understanding actors’ motivation, resources, and capabilities (Lawrence & Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006). Extant research has provided insights into how actors with abundant resources skillfully facilitate entrepreneurial endeavors and influence institutional environments. However, it tells us little about how actors with limited field power and resources carry out institutional work (Martí & Mair, Reference Martí, Mair, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009). When confronted with multiple institutional demands and limited resources and capabilities in challenging the status quo, the questions thus remain: How is new organizational form creation possible? What are the different types of institutional work at play? Exploring answers to these questions is important since literature focusing on how heroic actors leading social change does little to help us understand the process and strategies underlying social entrepreneurship initiated by peripheral actors (Dacin, Dacin, & Tracey, Reference Dacin, Dacin and Tracey2011).

An emergent literature has begun to understand how actors undertake institutional work to deal with multiple institutional logics (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Lounsbury & Crumley, Reference Lounsbury and Crumley2007; Rojas, Reference Rojas2010); what is still missing is a temporal perspective to illustrate how actors leverage and even create needed resources during the process of enacting institutional work in different organizational stages and how they gradually develop their capabilities to reach their organizational goals. Tracy et al. (Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011)’s multilevel model provides a useful framework for grasping how social entrepreneurs engage in three levels of institutional work – micro-, meso-, and macro-level – to create a new type of social enterprise in the UK. They suggest that when trying to blend for-profit and non-profit logics, social entrepreneurs simultaneously engaged in multilevel institutional work. Their study does not include a temporal dimension to consider how social entrepreneurs may engage and progress through three levels of institutional work through accumulative fashion. Other researchers underline that social entrepreneurs need different resources and skills that are distinctive from commercial entrepreneurs (Dacin, Dacin, & Matear, Reference Dacin, Dacin and Matear2010; Dart, Reference Dart2004) and higher level institutional work is likely to require more resources and capabilities (Leblebici, Salanick, Copay, & King, Reference Leblebici, Salancik, Copay and King1991; Lounsbury & Crumley, Reference Lounsbury and Crumley2007). Therefore, this simultaneous perspective is poorly suited to illuminate the creation process of new charity forms in developing countries and transitional economies where political, cultural, social, and market logics all come into play and actors have to cope with multiplicity in a gradual fashion. Martí and Mair (Reference Martí, Mair, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009) find that to alleviate poverty in Bangladesh, poorly resourced and peripheral social entrepreneurs need to undertake institutional work in an experimental manner. Therefore, we need a dynamic and temporal perspective to understand how actors accumulate resources and develop capabilities during the process of enacting and advancing institutional work.

Overall, the existing body of research leaves us with unanswered questions when it comes to explaining the institutional work of actors with limited field resources and experience in societies where multiple incompatible logics come into play. Two questions remain unanswered: (1) What kinds of institutional work do actors undertake to create a new organizational form in an environment of institutional multiplicity? (2) How do actors deploy resources and develop their capabilities to progress through different levels of institutional work along this process? Our purpose for this study is to answer these questions by analyzing the case of OF that is embedded in a challenging institutional environment in China's non-profit sector.

Multiple Institutional Logics and Challenges in China's Non-profit Sector

As a charity organization, OF is committed to disaster relief, supporting special children, and building a sustainable platform for integrating resources in the charity field. This commitment was formed and reformed during the organizational creation process, starting from 2006 and lasting until January 2011. During this process, Li and his OF team members constantly experienced multiple logics conflicts. Although being a world-famous actor, Li lacked sufficient resources and power when entering the charity field. OF was continuously exposed to challenges and tensions posed by two societal-level logics and two field-level logics. Table 1 compares these four logics according to their goals, means, and referent audience and stakeholders related to OF. In China, social organizations include non-profit organizations (NPOs) and non-government organizations (NGOs) with charity organizations being a type of NPO. During China's economic and societal transition, social organizations face increasing tensions between two divergent societal-level logics. The state logic refers to the orientation of the state and its entities in securing political and social order (Dobbin & Dowd, Reference Dobbin and Dowd1997) by regulating and supervising social organizations (Wang, Yin, & Zhou, Reference Wang, Yin and Zhou2012). Because of the Chinese authoritarian regime, state logic can be represented at different administrative levels. Local governments practice state logic to demonstrate their accordance with state intentions, in the meantime, they pursue local experimentation and innovation for their own political interests (Zhou, Reference Zhou2010). The civil society logic prescribes the demands for organizational autonomy and civic engagement in the process of tackling social problems (Ma, Reference Ma2002).

Table 1. Institutional multiplicity in China's non-profit sector: The case of OF

The interplay between state logic and civil society logic depicts the survival environment for social organizations in China (Kojima, Choe, Ohtomo, & Tsujinaka, Reference Kojima, Choe, Ohtomo and Tsujinaka2012). OF was created to embrace civil society logic through establishing an autonomous organization and encouraging civic engagement in charity activities. However, it faced the pressures of state logic to comply with the ‘dual administration system’. This system requires that, to obtain a non-profit status, charity organizations be registered at the Ministry of Civil Affairs or its local agency and affiliated with a professional supervisory agency that has a patronage relationship with the government (Saich, Reference Saich2000; Zhao, Reference Zhao2012). This regulation complicates the registration process and threatens the autonomy and efficiency of OF. Paradoxically, to obtain legitimacy and resources, OF needs to hold on a good relationship with government agency, putting OF at the risk of sacrificing autonomy and efficiency. Therefore, the coexisting and conflicting relationship between state logic and civil society logic adds ambiguity and uncertainty to the development of OF.

OF also needs to respond to incompatible prescriptions and demands posed by two field-level logics. Social mission logic requires charity organizations to maximize goods and services to relieve disasters and improve social conditions (Pache & Chowdhury, Reference Pache and Chowdhury2012; Santos, Reference Santos2012). Market logic guides social enterprises and charity organizations to follow market rules and use business approaches to maximize returns to social welfare (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls2009; Pache & Chowdhury, Reference Pache and Chowdhury2012; Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio1999). For OF actors, when committing to their social mission – engaging in disaster relief, supporting special children, and building a professional charity platform – they need to conform to the market logic and develop a sustainable model by following market rules and advocating their practices among powerful market players. However, OF's involvement in business activities creates the impression of mission drift (Jones, Reference Jones2007). The government and public are constantly concerned about a potential diversion of time, energy, and money away from OF's social mission, thus threatening its legitimacy and survival.

To summarize, these four logics constitute a complex institutional environment which OF actors need to navigate and to enact coping strategies. On one hand, OF actors need to comply with the state logic to obtain a legitimate status so they can encourage civic engagement in charity activities. On the other hand, OF actors need to follow the market rules and work with market players to develop a sustainable charity model and, at the same time, avoid mission drift. As our review above shows, the current literature has not provided a temporal perspective to unpack the process of how actors enact and progress institutional work to deal with such a complex institutional environment. Therefore, the creation and legitimation process of OF provides a rich setting for exploring this underdeveloped topic.

METHOD

To understand how actors deployed resources in devising institutional work to create a new organizational form under the environment of institutional multiplicity, we conducted a case study of OF. The goal of OF was to build a professional, transparent, and sustainable charity foundation that encourages civic engagement in charity. The emergence of OF was punctuated by alternating periods of stability and instability (Gersick, Reference Gersick1994), demarcating different organizational stages along the creation and legitimation process. In different organizational stages, actors confront different challenges and tasks and they need to adapt their coping strategies accordingly. By dividing organizational stages, we examine the characteristics of logic conflicts and actors’ institutional work as a coping strategy at different stages, thus having the opportunity to theorize a temporal model to illustrate the dynamic relationships among the organizational stage, institutional work, and resources and capability development. In the next section, we explain how data was collected and analyzed.

Data Collection

We collected data based on a combination of media interviews, personal interviews, organizational documents, and news reports. The primary source of the data came from transcripts of interviews conducted by various types of media, including newspapers, magazines, TVs, and Internet companies. We collected this interview data because the professional media tracked the founding and development of OF and interviewed various actors and stakeholders during its different stages. These interviews provided longitudinal data and reduced the potential for ex-post rationalization bias. We first received the interview list from OF, then we collected the media interviews on the Internet. Finally, we retained 14 interviews, including 10 interviews with Jet Li, 2 interviews with OF top management members, and 2 interviews with state officials of the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCA). The ambiguous information was checked with OF staff through follow-up emails.

Field observations were conducted in the summer of 2011, including personal interviews with two project managers at the Chengdu office, one brand manager, and one public relations manager at the Beijing headquarters. Informants were asked questions about the creation process of OF, the challenges they faced, and their responses. These interviews were semi-structured, lasting between 30–90 minutes, and were recorded and transcribed. We also collected OF's rich archival data, including quarterly working documents detailing its daily activities and annual financial reports issued from April 2007 to December 2010. In addition, we also checked media reports by searching keywords such as ‘One Foundation’, ‘civil philanthropic organizations’, ‘NPOs’, and ‘Jet Li’ in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), a database comprised of the main Chinese newspapers and academic journals. We obtained 362 hits, of which 75 were included in the analysis.

Data Analysis

Our in-depth case analysis consisted of four stages. The first stage involved separating the longitudinal process data into analytically identifiable and mutually dependent stages (Langley, Reference Langley1999). Focusing on identifying ‘disruptive events’ (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1999), such as key challenges and tasks and the introduction of new organizational structures and practices, we bracketed OF's creation and legitimation process into four organizational stages: idea gestation, piloting, adjusting, and transformation. In the second stage, based on actors’ narration of the external environment, we identified how actors perceived and responded to the conflicting demands imposed by four logics – state, civil society, social mission, and market – at different stages. Specifically, we asked ourselves the following questions during the analysis: (1) What are actors’ perception of the prescriptions and proscriptions of different logics during each stage? (2) What are the relationships among these logics? We iterated between open coding (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) and reviewed the literature on institutional logics until adequate conceptual themes were refined (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989).

The third stage focused on identifying different forms of institutional work that actors undertook to cope with multiple logics in each stage. We identified initial concepts through open coding. This generated first-order categories related to the activities engaged during the creation and legitimation process. We then used axial coding (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) to form second-order themes. Axial coding helped us move from thick description to explaining the phenomenon by making links among the first-order categories and collapsing them into a smaller number of themes (Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011). This process synthesized themes emerged from our data and the existing concepts in the literature. In the third step, we aggregated the second-order themes and categorized them into three levels of institutional work: individual level, organizational level, and societal level. Figure 1 shows the data structure related to actors’ institutional work. Furthermore, we identified what types of resources actors deployed to enact institutional work and how they developed their capabilities as the resulting outcome of institutional work at each organizational stage.

Figure 1. Data structure for institutional work by OF actors

In the final stage, we strived to see the ‘big picture’ by discovering key themes and overriding patterns. We then drew models to illustrate and theorize the dynamic relationships among organizational stages, institutional work, and resource deployment and capability development. We moved back and forth between the data and possible theoretical conceptualization until they reached a good fit (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989).

RESULTS

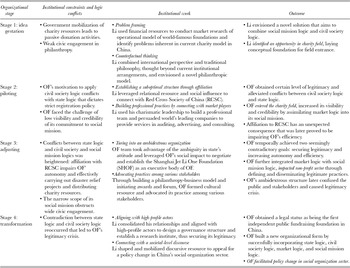

We now return to our research question and present empirical evidences to answer the question of how actors deal with multiple logics conflicts at different stages. Table 2 depicts multiple logic conflicts that OF faced, various types of resources and different kinds of institutional work that actors deployed to strategically deal with such logic conflicts, and the outcome that OF achieved at every stage. In the following sections, we will present the empirical evidences.

Table 2. Coping with institutional constraints and logic conflicts

Stage 1: Idea Gestation

On December 25, 2004, Li and his children almost lost their lives in a huge tsunami in the Maldives. Surviving this frightening experience, Li was motivated to establish a charity foundation for disaster relief and for providing psychological crisis prevention services for children and youth. However, he faced a critical institutional constraint: in mainland China, government mobilization of charity donation has been the dominant model leading to passive donation activities and weak civic engagement in tackling social problems. By comparing domestic and international charity models, Li realized that there was no ‘ready-to-wear’ model to rely on under the current condition. Under such a condition, Li undertook two forms of institutional work: (1) framing problems underlying current charity models; (2) counterfactually thinking of a novel charity model to combine social mission and civic engagement.

Problem framing

For Li, the motivation to build a novel charity foundation was driven by a form of individual-level institutional work – problem framing. It involves identifying the problem at hand and making explicit the failure of the existing practices (Suddaby & Greenwood, Reference Suddaby and Greenwood2005; Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011). Despite achieving great success as a movie actor, Li was totally an outsider to the charity field. To clearly identify the problems and find a solution for Chinese charity organizations, Li spent his own money on visiting universities and charity foundations around the world to learn global charity concepts and practices. He also invited consulting firms to conduct charity market research in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Li's global learning experience and market research reports helped him identify the limitations inherent in the current charity field, as he framed:

First, no non–government organization (NGO) has high credibility in China. Second, there does not exist a very transparent system during the operation. Third, most NGOs do not have a clear and long-term vision. Fourth, it is not convenient for Chinese people to donate

(Li & Zeng, Reference Li and Zeng2008).These four problems reflect Li's preliminary perception of the constraining institutional settings. First, government agencies use administrative mechanisms to mobilize charity resources by imposing pressures on individuals’ and firms’ donation behavior, leading to their passive donation activities. Second, many charity organizations in China lack credibility and civic engagement because they do not have transparent systems and long-term development visions. For Li, the current ‘fashionable model’ of disaster relief is shortsighted. As he stated,

The most prevalent response to a disaster in the world is a business/economic model, or a fashionable model. Newspapers start to report, people intensively express their emotion and love in a very short time. Emotions explode. Various foundations start to raise funds for relief. However, after one or two weeks, people become indifferent. After two months, people are no longer talking about the disaster

(Qu, Reference Qu2008).With financial resources and personal effort spent on market research and international comparison, Li clearly identified the problems inherent in China's current charity field. It provided an opportunity for Li to develop a novel charity foundation and practices to solve these problems.

Counterfactual thinking

After framing the problems inherent in the current charity field, Li engaged in counterfactual thinking – challenging assumptions, investigating underlying causes, and envisioning an unusual solution to the problems (Gaglio, Reference Gaglio2004; Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011). To enact this individual-level institutional work, Li creatively combined his international perspective and his knowledge of Chinese traditional philosophy. First, with his international perspective and learning experience, Li categorized two types of global well-known charity foundations. The first type is the ‘big foundation’ that uses investment income from its endowment to support annual programs. Li described it as ‘chicken that lay eggs every year’ (Qu, 2008). The second type is religious foundations such as Tzu Chi Foundation and Christian Foundation that receive donations based on people's religious beliefs. Li found that both types of foundations would not work out in China. On one hand, government regulations require a minimum of 70% of the funds be used for disaster relief annually, only allowing 10% for further investment, which constrains the growth of the foundation. On the other hand, Li realized that the government might be ‘sensitive’ to the religious foundation and a new foundation based on religious belief might restrict itself in reaching more citizens.

Li had to try something different and design a novel model that could encourage wide civic engagement. He asked himself a creative question, ‘Can I have eggs without chicken’? (Qu, 2008). To answer this question, Li turned to Chinese traditional philosophy for insight. He discovered Taoism has ancient wisdom that can offer insights to develop his charity concept, ‘The Tao begot one, one begot two, two begot three, and three begot the ten thousand things’. According to his understanding, ‘one means from zero to one; “zero” is doing nothing; “one” is doing something that makes a fundamental difference’ (Qu, 2008). He believed that if each person moves from inaction to donating at least one yuan each month, the small individual donations could be transformed into a much greater fund. Therefore, he proposed his charity concept of ‘1 person + 1 yuan +1 month = one big family’. With this belief, he named the organization ‘One Foundation’ that aims to build a viable charity model, raise citizens’ charity awareness, and cultivate a culture of sustainable giving in China. He described his novel charity model as:

My model is different – it is a kind of ‘Public Charity’. My ideal foundation is a fundamental charity facility much like the water and electricity to a city. It can support a relief of a disaster for two or three years. The ‘public charity’ is not driven by the influence of trends, but is driven by a custom of giving

(Qu, Reference Qu2008).To summarize, in idea gestation stage, Li creatively combined his international learning experience with his understanding of Taoism that helped him think beyond the current institutional arrangements and envision a novel charity model. His OF charity concept seeks to embrace social mission logic and civil society logic by encouraging a wide scope of civic engagement in disaster relief and improving the welfare of special children. Our analysis suggests that the individual-level institutional work of problem framing and counterfactual thinking changed Li's position from being an outsider in the charity field to a field insider and laid the conceptual foundation for field entering and enacting organizational-level institutional work.

Stage 2: Piloting

In the piloting stage, Li and his team members put OF's charity concept into practice. However, implementing the concept of encouraging civic engagement in charity activities was highly challenging because of restrictive regulations posed by the state and low credibility of charity organizations. According to the registration policy, OF should be registered as a public foundation, since only public foundations could raise funds from the public, while private foundations are not allowed to do so. However, the state has a hostile attitude toward allowing a civil charity foundation to be established as a public foundation because of suspicions of potential for-profit business activities (Zhao, Reference Zhao2012). Even if OF decided to register as a private foundation, it still faces the challenge of a ‘dual administration system’: to obtain a private foundation status, OF needs not only to be registered at the MCA or its local agency, but also to be affiliated with a supervisory agency, which is typically a government entity. However, the supervisory agencies usually reject affiliation requests from civil organizations (Zhao, Reference Zhao2012).

Under such circumstances, Li and his team undertook two types of institutional work by leveraging his relational resources, social influence, and charismatic leadership to mobilize relevant actors to deal with the conflicts between state logic and civil society logic. The first one was building a suboptimal organizational structure through affiliation with a highly legitimate government organization. The second one was building professional organizational practices through connecting with market players.

Establishing a suboptimal structure through affiliation

After several rounds of discussions with MCA and several local bureaus of Civil Affairs, OF still could not register as a public foundation or a private foundation. Under such conditions, Li decided to loosely couple with the state logic. As he described, ‘I don't like to complain about any institutions, maybe the Chinese government is considering loosening the regulations on public foundations. I am willing to think in the shoes of the government’ (Qu, 2008). The solution that Li and his team came up with was to affiliate OF with the Red Cross Society of China (RCSC) – China's largest official charity organization that monopolizes public donation resources. To make this affiliation work, Li used his relational resources to ask for referrals to bridge a connection with Changjiang Guo – the vice Minister of RCSC. As an exchange, Li suggested using the OF and his social influence to help RCSC transform itself from being a blood donation organization to becoming a professional charity organization.

On December l8, 2006, Li signed a contract with RCSC and registered ‘Jet Li One Foundation’ as a special program under the RCSC. Running under the umbrella of RCSC, OF gained the half-official legal status that allows it to raise funds publicly. However, OF's allocation of the funds needed to be monitored and approved by RCSC. As noted by Li,

In order to raise the money publicly, we have to rely on this platform. Although everybody donates one yuan every month, this money has to be shown on their bank account. This has to be done with credibility

(Li et al., Reference Li, Sun, Huang and Chen2008).Based on our analysis, we find that OF's affiliation with RCSC as a highly legitimate actor is an important form of organizational-level work devised to alleviate conflicts between the state logic and civil society logic. Although OF compromised its initial idea of building a foundation with an autonomous structure, this affiliation helped OF obtain a certain level of legitimacy that is crucial for its early survival.

Building professional practices by connecting with market players

From the charity market research, Li learned that one of the reasons leading to weak civic participation in charity activities is charity organizations’ lack of credibility. In order to increase OF's credibility, OF needed to build professional practices and a transparent system. Therefore, in piloting stage, Li started to assimilate elements from market logic into its social mission. First, using his charismatic leadership and influence, Li persuaded several people who had rich international business executive experience to join his team. For example, Li persuaded Weiyan Zhou – a Yale graduate with 20 years of executive experience in large commercial companies – to be the executive director of the OF. As Zhou described, ‘his charisma is very great and I was totally persuaded by his responsible and earnest attitude’ (Luo, Reference Luo2008). In addition, unlike many NPOs that are operated by volunteers, OF only recruited full-time employees, which helped OF maintain a high level of professionalism and stability.

Second, to ensure transparency and efficiency of its practices, OF assimilated elements of market logic by referring to the practices of public companies. For example, Li communicated with professional service companies about his charity concept and ideal organizational practice. Audit companies such as Deloitte and KPMG agreed to audit and release OF's annual financial record. Consulting companies such as Bain and Mckinsey and advertising companies such as BBDO and Ogilvy & Mather agreed to provide services for strategic planning and marketing. Impressed by Li's social entrepreneurship, these companies even provided their services for free.

In addition to assimilating the elements of professionalism, transparency, and efficiency from the market logic into OF's social mission, Li and his team began to seek to assimilate commercial elements into its practices. In winter 2007, Li was invited to the Six Annual Conference of Chinese Business Leaders. At first, he was reluctant to attend it. He asked himself why he needed to meet commercial entrepreneurs since he initially wanted to distance OF from commercial activities and sought to build a charity organization that encourages civic engagement. At the last minute, Li decided to attend this meeting, which later turned out to be a big surprise. During the meeting, Li met entrepreneurs such as Jack Ma – the founder of Alibaba Group and Huateng Ma – the founder of Tencent. One month later, he also attended the annual meeting of Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business where he met Bing Xiang – the dean of the business school and Weihua Ma – the president of Chinese Merchant Bank. The OF team began to learn to operate their foundation more efficiently and market its practices to include more audiences. The initial connection with entrepreneurs prepared OF for its later adjustment from being a charity foundation to becoming a platform that focuses on integrating charity field resources. As Li described:

Our specialty is fundraising, not spending the money. . . I hope I could cooperate with entrepreneurs. Their wisdom and business experiences could help me systematically manage the money. Philanthropy in 21st century is the one with the spirit of enterprise

(Lei, Reference Lei2010).Through establishing a professional team and a transparent system, OF increased its visibility and credibility. Through initial contact with entrepreneurs, the OF team began to think about adjusting its organizational practices to reach a larger audience and more stakeholders. These activities involved assimilating elements of market logic into its social mission commitment. To undertake this organizational-level work, Li used his charismatic leadership and social influence to attract market players’ attention and recognition. With this work, OF entered the charity field, moved from being a field outsider to becoming an important field player. OF's field entrance laid the ground for advancing institutional work to the societal level and associating its practices to a wider range of stakeholders in the charity field.

Stage 3: Adjusting

With OF's increasing visibility in the charity field, ironically, it experienced higher level conflicts among the state logic and civil society and social mission logics. Affiliation with RCSC had an unexpected consequence: it restrained OF from obtaining autonomy and effectively carrying out its social mission. Under the tight supervision of RCSC, OF lacked an independent legal entity and financial account and OF had little say about the allocation of its money and charity resources. This problem was exacerbated during OF's Wenchuan Earthquake relief in May 2008. OF raised about 800 million RMB in a month, however, it took a long time to get approval from RCSC to distribute donations. In addition, all relief materials had to be channeled through regional RCSC that was under control of both RCSC headquarters and local government, whose requirements were often in conflict. This controlling system greatly reduced OF's efficiency.

Another challenge faced by the OF team was that with their narrow scope of social mission, they could not achieve the goal of encouraging a wide scope of civic engagement. OF's primary social mission at the early stage was to provide services of psychological crisis prevention for children and youth who had experienced earthquakes or other disasters. However, psychological crisis prevention was a very new concept in China; only few people were knowledgeable about it. In the first year, OF only collected 10 million RMB, of which, individual donations only account for 19%. This result was too far away from reaching their goal of encouraging civic contribution. The executive director – Weiyan Zhou said: ‘it is a wasting of the brand of Jet Li. If it continues like this, OF has no way out’ (Lei, 2010).

Under such constraints, the OF team decided to redesign OF's organizational structure and practices to reduce RCSC's control, improve efficiency, and reach more stakeholders in the field. After the Wenchuan Earthquake disaster relief, they realized that with its increasing credibility and role in the field, they had more power to negotiate with local government and advocate their practices among various stakeholders. At the same time, the government was aware of the big impact of civic organizations and prepared to negotiate (Simon, Reference Simon2008). In adjusting stage, the OF team carried out two types of institutional work: (1) turning OF into an ambidextrous organization (Benner & Tushman, Reference Benner and Tushman2003) to obtain more autonomy and efficiency; (2) advocating practices among various stakeholders by forming a business and charity model and initiating charity awards and forum.

Turning into an ambidextrous organization

After realizing the structural constraints, the OF team attempted to pursue becoming an independent legal entity with independent financial accounts. After consulting with experts and government officials, they found that it was still difficult to transform OF into a public foundation. However, they also realized that the ambiguity embedded in existing institutional frameworks might provide room to negotiate for autonomy. Since 2008, the national MCA chose neither to promote nor to restrict the discussion and practice of social enterprise (Zhao, Reference Zhao2012). The OF team took advantage of this ambiguity and leveraged OF's impact to persuade RCSC and Shanghai Municipal Civil Affairs (SMCA) to allow OF to establish a private foundation as an executive body of OF. As Weiyan Zhou said,

The best solution is to establish a public fundraising foundation. However, the government is very strict with the examination and approval. So we ask around about how to deal with it. People came up with different solutions. For example, One Foundation could register a private company at the Industry and Commerce Bureau, then transfer the money from the RCSC One Foundation Project to this company to carry out projects. With the same team, we can do both. However, this solution is illegal and not transparent. There are many problems. So we had to consult with lawyers and leaders of RCSC and also officials from MCA. Finally, we made a hard decision: establish a private foundation

(Huang, Reference Huang2011).On October 16, 2008, Shanghai Jet Li One Foundation (SHOF) was launched. As a private foundation, SHOF was not allowed to raise money from the public. However, the money raised publically by the OF could be transferred to SHOF. With this organizational rearrangement, the OF team could avoid the tight control of RCSC and independently allocate financial resources and execute projects. Realizing the increasing importance and credibility of OF in mobilizing charity resources, RCSC and SMCA also turned a blind eye to this settlement.

Our analysis suggests that in this stage, OF began to identify and take advantage of the ambiguity inherent in the state's attitude towards social organizations and leveraged its proven social impact to negotiate for an ambidextrous architecture. By turning OF into an ambidextrous organization, OF temporaly tempered the conflicts between the state logic and social mission logic. This adjustment helped OF achieve two seemingly contradictory goals of alignment and adaptability (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Reference Gibson and Birkinshaw2004). On one hand, loosely coupling with the state logic by affiliating with RCSC secured OF's legitimacy as a public foundation. On the other hand, OF obtained more autonomy and increased its efficiency.

Advocating practices among various stakeholders

The OF team realized that in order to create more impact on the charity field and even on the non-profit sector, they needed to adjust their social mission. On April 19, 2008, Li announced OF's new social mission: in addition to providing disaster relief and supporting special children, they strive to build a platform to intergrade charity field resources and support Chinese NPOs’ professional development. Recognizing that Chinese NPOs lack a professional and transparent system and there are no widely acknowledged norms and standards in charity field, the OF team started to form the cultural resource by collecting, understanding, and leveraging their knowledge to define and disseminate what is considered to be appropriate norms and standards in China's non-profit sector.

First, OF created a ‘win-win’ donation model to blend business and charity. This model persuades firms to donate 0.01yuan, 0.1yuan or 1yuan from the profit of selling one product and it can also help them promote their brands. For example, on March 5, 2008, OF signed a contract with China's film industry leader Huayi Brothers Media Group. According to the contract, if one film ticket was sold, Huayi Brothers would donate 0.1 yuan and the related theater would donate 0.01yuan to OF. OF advocated and extended this model to various industries, including bank, beverage, clothing, sports, real estate, and manufacturing, thus cultivating a charity habit among commercial firms.

Second, OF initiated ‘OF Philanthropy Awards’ to define and disseminate the norms and standards for NPOs’ practice. It set ‘credibility, professionalism, execution and sustainability’ as evaluation standards and invited consultants, legal and financial professionals, journalists to vote for ‘philanthropy stars’ and ‘future philanthropy stars’. On November 1, 2008, OF held a grand ceremony in Beijing and awarded seven Chinese NPOs with 1 million RMB to fund their daily operations and improve the organizations’ services. Since then, NPOs with specializations ranging from mental and physical health to education and poverty alleviation have received these awards. These awards also established role models and advocated what is required to be successful NPOs in China.

Third, with its increasing publicity and credibility, OF was able to connect and influence a larger scale of stakeholders. Hosting an annual philanthropy forum is another advocacy activity. On October 31, 2009, the first annual forum gathered stakeholders across various sectors, including scholars, government officials, and representatives from companies, NPOs, and media, to exchange ideas on the best philanthropic practices of in China. The first forum received wide attention from media, 26 reputable Chinese publications made featured reports on this event.

To summarize, through designing the business-charity donation model, awarding, and hosting forums, OF escalated institutional work from organizational-level to societal-level. In this stage, the OF team promoted advocacy work by deliberately representing the interests of various stakeholders from various sectors (public, market, non-profit sector) and at the same time promoting its own agenda (Lawrence & Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006). By forming a cultural resource, OF defined and disseminated the standards in China's non-profit sector and obtained endorsements from important referent audiences across sectors. This set the stage for its later transformation into an independent charity fundraising foundation. Our analysis also suggests that by organizational adjustment and advocacy work, OF further integrated market logic and temporarily mitigated the conflicts between the state logic and social mission logic. However, the temporal mitigation was later proved to be problematic: OF's ambidextrous architecture confused the public and stakeholders and caused its legitimacy crisis.

Stage 4: Transformation

Through previous accumulative work, OF has amassed wide recognition in the charity field and non-profit sector. However, OF's ambidextrous structure brought a legitimacy crisis. The public and OF's cooperators were confused with OF's dual identity and concerned about whether the money donated to OF had been properly used. To them, OF was a ‘private’ foundation (SHOF), but it was wearing a ‘public’ hat under the RCSC (Ping, Reference Ping2010). Considering public suspicion and OF's potential mission drift, SMCA urged SHOF to stop receiving money transferred from OF. Moreover, OF faced the risk of losing the right for public fundraising because its contract with RCSC approached expiration. In this situation, previously tempered logic conflicts surfaced again: the government's interest in controlling and avoiding risks conflicted with OF's demands for autonomy and efficiency. In this stage, in order to deal with the reoccurring logic conflicts mainly induced by the state logic, Li and his team mainly engaged in two forms of societal-level institutional work to seek a solution. The first one was aligning with high-profile actors to secure legitimacy and credibility. The second type was connecting with a societal-level discourse to impose pressure for organizational transformation.

Aligning with high-profile actors

For OF, an important step in obtaining a public and independent fundraising status was to build a professional and transparent governance structure. To accomplish this goal, Li consolidated his relationships and aligned with high-profile actors, including prestigious entrepreneurs, intellectuals, and prominent figures from the government and media. First, Li invited them to design a governance structure that had the similar feature as a public company. According to their plan, a new OF with an independent status would be headed by a council composed of nine members, including seven entrepreneurs, Jet Li, and Weiyan Zhou. The organizational decision would be made during the annual board meeting and daily administration would be managed by a management committee. After the first council meeting, in early February 2010, the council submitted an application to MCA with the aim of transforming OF into a public and independent foundation.

Second, after experiencing the iterative phase of conflict and cooperation with government, the OF team concluded that satisfying the enduring demands from the stage logic and obtaining endorsement from government officials was an inevitable step towards obtaining a public and independent status. The team then realized an opportunity to ally with a high-profile official. Zhengyao Wang – the former director of the MCA's social welfare and charities department – was quite touched by OF's and other civic charity organizations’ active engagement during the disaster relief of the Wenchuan Earthquake. During his term, he had pledged to promote the development of social organizations in China. Therefore, Li invited Wang to establish and direct the OF research institute. On June 21, 2010, Beijing Normal University One Foundation Public Interest Research Institute was founded. Prominent government officials and political actors and another 200 people, including university scholars both from China and abroad, leaders of public interest organizations, and entrepreneurs attended the ceremony. Founding such an institute was a creative attempt that further facilitated cross-sector exchanges and widely opened the door for exploring domestic and international cooperation.

Our analysis finds that aligning with high-profile actors was an important form of societal-level institutional work enacted for survival from the legitimacy crisis. OF connected with high-profile actors across sectors to design a professional governance structure and establish a research institute, thereby securing and increasing its credibility and legitimacy.

Connecting with a societal-level discourse

Although the OF council made a great effort of applying an independent status, they did not receive positive feedback from MCA. Being frustrated again, Li's team decided to draw on a wide public discourse to appeal for a solution. They enabled discursive work (Lawrence & Phillips, Reference Lawrence and Phillips2004) to make its organization widely understood in the Chinese society. First, they tried to enhance OF's positive image. In June, a film titled ‘Ocean Heaven’, starring Li and another famous actor, was released. Appealing for giving more care to special children, this movie attracted great attention from the public. Then, Li openly spoke about the organizational dilemma and constructed and mobilized discursive resources (Hardy, Palmer, & Phillips, Reference Hardy, Palmer and Phillips2000) to affect institutional order in the non-profit sector.

In summer and autumn of 2010, Li changed his previous attitude of ‘putting on the shoe of government’ to talk about his upset with government attitudes. During interviews with Netease and The Beijing News, Li talked about how OF's current status hindered OF from fulfilling its mission of encouraging civic engagement and cherishing a sustainable giving culture in China. On September 12, 2010, Li revealed in a CCTV interview where he complained that while OF's practices has gained wide recognition, it might be shut down due to the lack of a clear legal status. As he noted,

The OF is like a 3-year-old child, healthy but lacking an identity card. He might be questioned by those who seek more transparency and professionalism in China's charity development. The government should open a ‘window’ that would allow charity organizations like OF to survive

(Li, 2010).Li also constructed the discursive resources to relate OF's problem as the general dilemma faced by China's social organizations and appealed for a change in China's non-profit sector. Media exposure sparked immediate public discussion on similar situations faced by many charity organizations and grassroots NPOs. The discourse criticized that the patriarchal relationship between OF and RCSC hinders OF's development. Some government officials and scholars began to reflect on government regulations and appeal for a solution. Thus, connecting with the societal-level discourse and mobilizing discursive resources helped frame the problem beyond OF's own dilemma to a prevalent challenge in China's social sector. The widespread public discussion imposed high pressure on MCA. Liguo Li, the director of MCA, noted in an interview that MCA paid close attention to OF's development; they were impressed by its transparent structure and effective practices and they were doing research to examine how to treat OF's model.

The combination of high-profile actors’ advocacy, widespread media exposure, and increasing public awareness had pushed the government to make official responses. This condition attracted attention from Runhua Liu – the director of Shenzhen Municipal Civil Affairs Bureau (SZMCAB). Liu made a call with Li and invited OF to be registered as a public foundation in Shenzhen. As a ‘special economic zone’, Shenzhen enjoys an advantage of local experimentation. Since 2008, SZMCAB has tried to carry out a series of reforms in the social organization sector. In July 2009, Shenzhen government signed an agreement with the MCA to undertake a preliminary trial that allows social organizations to directly register with the SZMCAB without affiliating to a supervisory agency. On December 3, 2010, the SZMCAB officially approved OF with a legal right for independent public fundraising. On January 11, 2011, the Shenzhen OF (SZOF) was officially established. Composing of prestigious entrepreneurs, OF team members, and economists, the SZOF council institutionalized its mission and practices. SZOF is committed to disseminating innovative and civic charity concepts and establishing a professional, transparent, and sustainable platform for China's non-profit sector.

To conclude, our findings suggest that connecting with societal-level discourse is an important form of institutional work enacted to highlight the problem. Facing the reoccurring logic conflicts, OF mobilized discursive resources and related its organizational dilemma to the interests of various stakeholders to collectively advocate a change in non-profit sector. Through aligning with high-profile actors and connecting with societal discourse, OF formed a community and imposed pressures on government to legalize its status, finally achieving its goal of becoming an independent and public charity organization.

The Impact on China's Social Organization Sector

The creation and legitimation process of OF set an example of cross-sector (public, private, and social organization sector) collaboration and organizational innovation in China's non-profit sector. More importantly, it stirred wide public discussion about the urgent need for registration and administration reform in China's social sector. Since the beginning of 2011, local governments including Beijing, Shenzhen, and Chengdu announced that charity, social welfare, and social service organizations do not need to get permission from a supervisory agency to register their status. Moreover, on July 4, 2011, Liguo Li announced that this direct registration would be implemented on a nationwide scale. This announcement is seen as an important step toward the abolishment of the ‘dual administration system’. The OF collaborated with high-profile actors and various stakeholders to collectively urge and facilitate such policy reform in China's social sector. While the story of the OF and its impact still continue, its creation and legitimation process leaves us a lot to reflect upon and theorize.

DISCUSSION

This study aims to investigate how actors navigate through multiple institutional logics and enact institutional work to create and legitimate a new form of charity foundation in China. We have discovered two important findings. First, our results show that the endurance of institutional multiplicity and complexity creates latent paradoxes in which logic conflicts and alleviation appear temporally (Jay, Reference Jay2013) in different organizational stages. In addition, due to the lack of experience, actors have an inadequate perception of external institutional arrangements at each stage. These features lead to the fact that actors have to try out and experience more stages to gradually accomplish their goals. For example, in the piloting stage, affiliation with RCSC provided OF a certain level of legitimacy. However, the OF team did not realize that this affiliation and loose coupling with the state logic would have an unexpected consequence in that it could impede OF from effectively carrying out its social mission. In the adjusting stage, the OF team conceived that, by turning OF into an ambidextrous organization, they could undermine the state logic and reinforce other logics to promote OF's autonomy and efficiency. Yet, the dual identity dilemma further exacerbated logic conflicts and caused a legitimate crisis. These results show that actors’ interpretation and responses to logic conflicts appear as both a success and failure at specific organizational stages. The organizational structure and practice that work well in an early stage (e.g., piloting stage) may not work well in a later stage (e.g., adjusting stage), therefore, actors need to accumulate resources, progress institutional work, and develop capabilities in subsequent stages to deal with enduring logic conflicts.

Second, we unpack the process of how institutional work is undertaken in a temporal fashion and how actors deploy resources to enact it and develop their capabilities to cope with multiple logics. Figure 2 illustrates the model of organizational stage and temporal and progressive institutional work. Our results show that from the idea gestation stage to the transformation stage, OF actors advanced institutional work from individual – to organizational – and to societal- level. We also elaborated on the resources actors deployed to enact institutional work and the resulting outcomes at each stage (see Table 2). Specifically, we found that OF's deployment of resources advanced along this process. In early stages, OF mainly focused on using and leveraging Li's financial resources, international experience and knowledge, charismatic leadership, and social influence. In later stages, with OF's increasing visibility and credibility, the OF team focused on forming cultural resources and constructing and mobilizing societal discursive resources. Along these lines, OF's capabilities were also developed and expanded: from identifying opportunity and entering the charity field to creating an impact on the non-profit sector and to facilitating policy change in China's whole social organization sector. With its growing scope of resources and capabilities, the OF team gradually improved its toolkits and skills to mitigate conflicts and integrate multiple logics and finally legitimate its new organizational form and practice.

Figure 2. Organizational stage and institutional work: a temporal model

Theoretical Implications

This study offers several theoretical contributions to our understanding of actors’ responses to institutional multiplicity (Zhang, Tan, & Tan, forthcoming). First, our study provides empirical evidence of how institutional multiplicity creates a possibility for discretionary action and organizational innovation. Extant literature lacks a rich understanding of how actors develop a wider scope of responses to a condition of multiple logic conflicts. We show that although actors have limited experience and resources to deal with institutional multiplicity, they can focus on dealing with pressuring demands and proscriptions posed by certain logic (e.g., state logic) during the different organizational stages. As organizations evolve and experience enduring logic conflicts, actors develop a repertoire of responses: they prioritize, assimilate, blend, and balance logics. By prioritizing and/or adapting to certain logic(s) at a particular stage, actors avoid being overwhelmed by multiple demands so that they can temporally mitigate logic conflicts, resolve pressing issues, and achieve provisional solutions. Such an insight shifts current discussion centering on constraints posed by institutional multiplicity to propose paying more attention to understanding how actors expand their repertoire of responses (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011) and even take advantage of logic multiplicity to negotiate a novel organizational form.

Second, this study contributes to the institutional work and social entrepreneurship literature by theorizing a temporal model to illustrate the dynamic relationships among organizational stage, institutional work, and resources and capability development. Built on Tracey et al. (Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011)’s multilevel model of institutional work, we advanced a temporal perspective by showing how actors gradually progress institutional work from individual to organizational and to society level. This temporal process is due to institutional multiplicity and actors’ resources and experience limits that we have discussed earlier. Our paper thus contributes to an underexplored topic about how actors will less field resources and experience initial changes (Martí & Mair, Reference Martí, Mair, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009). Furthermore, this study conceptualizes actors’ capability development as the expansion of their influence: from understanding and entering the charity field, to more broadly influencing practices of the non-profit sector, to facilitating regulative change in the social organization sector that benefits not only charity organizations but also NPOs and NGOs. In other words, our research theorizes a dynamic process in which certain resources are necessary for enacting a certain level of institutional work, capabilities developed as the resulting outcome from lower level of institutional work which sets the stage for the next step of resource leverage and a higher level of institutional work.

Implication for Understanding Innovations in China's Non-profit Sector

First, the findings observed from OF in China's non-profit sector offers much needed insights into actors’ response to a high degree of institutional complexity in the context of a transitional economy, given that prior findings have been primary derived from Western developed society. Second, the present study sheds light on how two features of the state logic create a room for logic integration and discretionary actions. The first feature is that the demands prescribed by the state logic can be represented and met at both state and local levels. Chinese state requires strict regulation and supervision over social organizations, but meanwhile, it encourages local experimentation. The establishment of SHOF at Shanghai and SZOF at Shenzhen illustrates local governments’ interests in local innovation and their willingness to negotiate. The second feature is that the state's attitude of neither promoting nor restricting the practice of social enterprises entails a degree of ambiguity that allows actors to engage in discretionary action (Goodrick & Salancik, Reference Goodrick and Salancik1996). Due to these two features, Li and his team seized the opportunity and aligned with external stakeholders to negotiate with the state and mitigate the conflict between the state logic and other logics, and finally, not only legitimated its new charity form but also became a changing agent in China's social organization sector.

More broadly, our paper highlights a Chinese approach to organizational innovation and institutional change. Huang (Reference Huang and Huang2010) suggests that under the pluralist environment in China, new institutions are edged by experimentation and gradual implementation. As our case shows, being embedded in the emerging non-profit sector where social entrepreneurs, government officials, and market stakeholders have the mindset for temporal solutions and continuous negotiation to gradually reach the condition that satisfies demands from multiple institutional constituents and audience. We expect that, as institutional multiplicity and conflicting relationships will still be a dominant feature in China's social organization sector, this temporal solution and incremental change will be a viable strategy to drive change and innovation.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study has several limitations. First, the main research findings are drawn from media interviews and reports, which tracked the founding process of the OF and reduced potential ex-post rationalization bias. However, this source did not directly investigate the actual perception, motivation, and process through which OF actors deal with multiple logics. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. Second, this research was based on a single case study; its generalizability is limited. However, focusing on a single case is necessary to investigate the process of emergence of a new organizational form to capture its complex dynamics (Maguire & Hardy, Reference Maguire and Hardy2006). Although Li initially lacked field resources and relevant capabilities, his high profile still helped OF garner resources and networks. Future studies may explore how actors with lower profiles and fewer resources enact institutional work to navigate through a pluralistic institutional environment and create a new organizational form.

We suggest that the following topics bear further exploration. First, future research might explore OF's further development and its impact on China's non-profit sector. We suggest that logic integration and legitimate status established in OF's transformation stage is still a temporal solution. Further research may study how actors’ different interests and demands, reflected as enduring logic conflicts, further play out and influence OF. In addition, future study could also explore whether and how the institutional work undertaken in this context might be diffused, learned, and imitated by other Chinese NPOs.

Finally, the temporal model theorized in this paper should be tested and refined in future research endeavors. For example, it would be interesting to explore whether and to what extent this model can be applied to understand the emergence of new organizational forms and practices in other transitional economies. In addition, researchers may also extend this model to understand innovation and change in mature fields in developed societies where ‘implications of logics have been clarified and built into regularized practices’ (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011: 335). Building a new organizational form in mature fields might be more challenging because the availability for discretionary actions is lowered (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Thus, it may require actors to manage the settled but divergent multiple logics, accumulate resources, and develop capabilities to find provisional solutions and gradually institutionalize new organizational forms and practice. We hope our temporal model is beneficial for researchers to take new organizational form creation as an iterative process of dealing with multiple logics and unpacking actors’ strategy of layering resources and capability to reach organizational goals.

CONCLUSION

This study resonates the recent call for understanding actors’ response to institutional complexity posed by multiple logic conflicts (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Using the OF case, we analyze how the coexisting and competing relationships among multiple institutional logics in China's non-profit sector provide a possibility for organizational innovation. Building on Tracey et al. (Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011)’s model of multilevel institutional work, this paper advances a temporal perspective by showing how actors progress institutional work from individual-, to organizational- and to societal-level on the path toward achieving their goals. This study contributes to institutional theory and social entrepreneurship literature by showing why the temporal institutional work is a viable strategy to deal with logic conflicts and elaborating how actors accumulate resources and develop capabilities to legitimize a new organizational form as well as their practices. While much remains to be further explored and refined, we hope this paper provides an exploratory work to understand organizational innovation in China's non-profit sector and, more broadly, to understand actors’ temporal responses to complex institutional environments.