Introduction

The archaeobotanical record of early (pre-3000 cal BP) domesticated rice (Oryza sativa) in Island Southeast Asia largely relies on the presence in pottery sherds of husk impressions and inclusions, and, occasionally, adhering grains (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Shutler, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1986; Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood, Gillespie, Thompson, Vogel, Ardika and Datan1992; Paz Reference Paz1999, Reference Paz2005; Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, Beavitt and Kurui2000; Castillo & Fuller Reference Castillo, Fuller and Bellina2010; Barker et al. Reference Barker, Hunt, Carlos, Barker and Janowski2011). Problematically, these types of ‘rice-associated pottery’ have been presented as the earliest evidence for the introduction of rice farming into the region (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Shutler, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1986; Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood, Gillespie, Thompson, Vogel, Ardika and Datan1992; Beavitt et al. Reference Beavitt, Kurui and Thompson1996), despite the uncertain domestication status of the associated rice. Finds have often been assumed to represent domesticated rice based on grain or husk morphology, which is not diagnostic of domestication within Oryza species. Assessment of the abscission scar on spikelet bases is considered the most reliable diagnostic marker of domesticated rice in macrobotanical assemblages (Thompson Reference Thompson1992; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009). Without assessment of this marker, early rice-associated pottery could indicate either intentional or incidental inclusion of native wild rice.

The oldest rice-associated pottery in Island Southeast Asia was recovered in 1989 during excavations at the cave of Gua Sireh in south-western Sarawak on Borneo (Ipoi & Bellwood Reference Ipoi and Bellwood1991; Ipoi Reference Ipoi1993). A single, charred rice grain was found embedded in the surface of a sherd and subsequently radiocarbon-dated to 4960–3565 cal BP (Figure 1; Table S1 in the online supplementary material (OSM); 3850±260 uncal BP, CAMS-725; Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood, Gillespie, Thompson, Vogel, Ardika and Datan1992). Rice husks were also reported from comparable stratigraphic contexts at Gua Sireh (Beavitt et al. Reference Beavitt, Kurui and Thompson1996). Despite the imprecision of the radiocarbon date, the Gua Sireh find is anomalously old compared with other reliable finds of rice-associated pottery from Island Southeast Asia (Paz Reference Paz2005), and up to 1000 years older than the estimated timeline for Neolithic expansion into the region (Bellwood Reference Bellwood2017: 273–74). The curious case of this single pottery sherd outlier invited re-analysis to clarify the chronology of early rice cultivation in Island Southeast Asia.

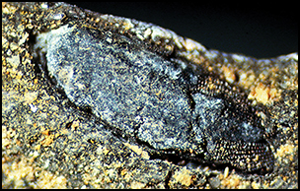

Figure 1. Photomicrograph of a fully charred Oryza grain embedded in the surface of the older sherd. The grain was AMS-dated to 4960–3565 cal BP (CAMS-725; Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood, Gillespie, Thompson, Vogel, Ardika and Datan1992). Note the partial husk on the exterior with its distinctive ‘checkerboard’ pattern. No scale on original (image courtesy of R. Gillespie).

Here we present the results of penetrative but non-destructive microCT analysis of two sherds from Gua Sireh: the anomalously old sherd (CAMS-725) and a more recent sherd directly dated to 1990–830 cal BP (Table S1; 1480±260 uncal BP, CAMS-721; Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood, Gillespie, Thompson, Vogel, Ardika and Datan1992). The objective is to determine the presence and domestication status of associated rice through analysis of spikelet bases included within the organic temper of the ceramic sherds. Previous qualitative development of microCT technology applied to the investigation of domesticated rice within pottery sherds (Barron et al. Reference Barron2017; Barron & Denham Reference Barron and Denham2018) is extended here through the quantitative assessment of spikelet-base assemblages. Our results demonstrate that organic inclusions within each sherd function as a discrete, well-preserved archaeobotanical assemblage.

The early (pre-3000 cal BP) dispersal of rice in Island Southeast Asia

Current archaeobotanical evidence suggests that rice was first domesticated in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze Valley c. 8000–6000 cal BP, following a protracted period of pre-domestication cultivation (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009; Deng et al. Reference Deng, Qin, Gao, Weisskopf, Zhang and Fuller2015). Subsequently, rice cultivation spread to southern China by c. 5000–4700 cal BP, to southern Vietnam by c. 4150–3265 cal BP and to Taiwan by at least 4200 cal BP and possibly as early as 4800 cal BP (Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood2011; Barron et al. Reference Barron2017; Castillo et al. Reference Castillo, Fuller, Piper, Bellwood and Oxenham2017; Deng et al. Reference Deng, Hung, Fan, Huang and Lu2018; Yang et al. Reference Yang2018). Rice-associated pottery from Andarayan in northern Luzon (Philippines) was directly dated to 3970–3380 cal BP (Table S1; 3400±125 uncal BP; lab code not provided; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Shutler, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1986: 5), and was inferred to have been made locally; it is currently the oldest putative evidence for cultivated rice in the Philippines.

The early Gua Sireh sherd, dated to 4960–3565 cal BP (CAMS-725), is anachronistic when compared to the chronological framework for both the domestication of rice in East Asia and the dispersal of rice cultivation through Southeast Asia. Although comparably aged rice-tempered pottery on Borneo is claimed in association with a burial dated to almost 5000 cal BP at Niah Cave (Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, Beavitt and Kurui2000), this find is neither confirmed nor discussed in later publications (Barker & Richards Reference Barker and Richards2013; Barker & Farr Reference Barker and Farr2016). Furthermore, Doherty et al. (Reference Doherty, Beavitt and Kurui2000: 148) identified rice in sherds from 35 sites across Borneo, “covering the period from 4000–3000 BP to 400 BP”, but neither the imaging nor dating of these sherds has been fully published to enable independent assessment. Doherty et al. (Reference Doherty, Beavitt and Kurui2000) suggested that rice in pottery from early sites (i.e. pre-dating 3000 cal BP) was relatively sparse and suggestive of incidental inclusion during the manufacturing process, rather than intentional addition as temper. They propose that rice remains only became a popular tempering material on Borneo after 1000 cal BP. The current evidence does not point to significant open-field rice cultivation in most regions of Island Southeast Asia before 2000 cal BP (discussed in Donohue & Denham Reference Donohue and Denham2010).

Regardless of the imprecise age estimates for this early inclusion of rice, a significant methodological issue prevents the establishment of an irrefutable link between rice-associated pottery and the introduction of cereal agriculture to Borneo (cf. Hayden Reference Hayden, Barker and Janowski2011; Barton Reference Barton2012). The occurrence of rice does not necessarily mean the presence or cultivation of domesticated rice, as a number of wild rice species grow across the island (contra Beavitt et al. Reference Beavitt, Kurui and Thompson1996: 30). Conceivably, these could have been exploited long before the introduction of domesticated rice cultivation by people engaged in foraging. Modern wild rice distributions (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1994; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Sato, Castillo, Qin, Weisskopf, Kingwell-Banham, Song, Ahn and van Etten2010), as well as Early Holocene palaeoenvironmental records, such as the Loagan Bunut lake core on Borneo (Hunt & Premathilake Reference Hunt and Premathilake2012), show the spatial and temporal prevalence of wild rice species. Rice appearing in the archaeological record, particularly in small quantities, may therefore be potentially associated with wild rice foraging practices and need not imply cultivation.

Methods

Thompson (Reference Thompson1992) first developed the method to discriminate domesticated rice in macrobotanical assemblages using the distinctive abscission scar, namely the detachment mark, on spikelet bases. This scar represents anthropic selection for non-shattering seed dispersal, as opposed to the natural shattering dispersal mechanism of wild species. This method was refined and applied by Fuller et al. (Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009) to archaeobotanical assemblages at multiple sites in the Yangtze Basin (Fuller & Qin Reference Fuller and Qin2008; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Denham, Arroyo-Kalin, Lucas, Stevens, Qin, Allaby and Purugganan2014; see ‘spikelet reference images’ in the OSM). At maturation, abscission in wild rice leaves a smooth, concave and rounded depression after the spikelet detaches. In contrast, domesticated scars are torn out, leaving a deep and irregular pit in place of the abscission layer; in addition, these pits tend to be asymmetrical rather than round. Green-harvested (or ‘immature’) types are identified by a protruding scar, in which some of the rachilla vasculature is still attached to the spikelet base, indicating that it has been broken off before it is ripe (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009). In cases where the above criteria are obscured, spikelet bases are classified as indeterminate.

The discrimination of spikelet-base morphology has not previously been used to verify claims for domesticated rice associated with pottery in Island Southeast Asia. Thompson (Reference Thompson1992) had limited success in the application of this technique to the investigation of rice-tempered pottery sherds; spikelet bases were often too damaged or fragile for further analysis following manual extraction of the samples from the pottery. Barron et al. (Reference Barron2017) have recently demonstrated the utility of microCT imaging for the high-resolution, penetrative 3D visualisation of rice spikelet bases within pottery sherds from Vietnam. Images of organic materials within the sherd were of sufficient resolution to determine qualitatively the domestication status of rice spikelet bases. The technique has so far not been applied to the quantitative investigation of rice-associated pottery.

The Gua Sireh sherds were scanned at the National Laboratory for X-ray Micro Computed Tomography (CTLab) at the Australian National University. The sherds were placed in an aluminium tube, secured with packing foam and required no further sample preparation. They were scanned using high-resolution helical-CT (ANU4) with a 2mm aluminium filter at 100kV and 50μA, resulting in a 16.7μm voxel size (Latham et al. Reference Latham, Varslot and Sheppard2008; Myers et al. Reference Myers, Kingston, Varslot and Sheppard2011). The datasets were then visually rendered using Drishti Paint v2.6.4 and Drishti Renderer v2.6.4 (Limaye Reference Limaye2012).

Initially, the dataset for each sherd was viewed in low resolution, specifically at 1/64 of maximal resolution, to identify organic inclusions within the pottery matrix. Organic inclusions are readily identifiable due to lower X-ray attenuation, representing lower densities relative to the clay matrix and mineral temper. We determined the spatial limits of inclusions of interest before subjecting them to high-resolution (16.7μm resolution) 3D visualisation and targeted morphological analysis to identify rice spikelet bases (Barron & Denham Reference Barron and Denham2018). Where possible, quantitative analysis was designed to evaluate a minimum of 100 rice spikelet bases within a sherd and to create accompanying visualisations of 50 spikelet bases within each sherd. Rice spikelet bases were classified into wild, domesticated, immature and indeterminate types using reference images (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009; Deng et al. Reference Deng, Qin, Gao, Weisskopf, Zhang and Fuller2015; see ‘spikelet reference images’ in the OSM).

Results

MicroCT analysis of the two dated sherds from Gua Sireh under study indicates sparse organic remains within the older sherd (CAMS-725) and abundant organic remains distributed throughout the more recent sherd (CAMS-721) (Figure 2). Visual inspection suggests that organic inclusions had been converted to charcoal as a result of being encased within a low-oxygen environment during firing of the pottery. Although the organic materials are highly fragile and prone to disintegration upon disturbance, they are well preserved in situ. Attempts to date rice spikelet bases encased within the more recent sherd were, however, unsuccessful, possibly due to mineral replacement of the organic inclusions (see ‘attempted radiocarbon dating’ in the OSM). Nonetheless, the hard pottery fabric preserved high levels of morphological detail of the encased organic remains. There were several regions of interest within the older sherd, namely areas that displayed X-ray attenuation values of the expected range for organic materials (Figure 2B). These were subsequently investigated in high resolution, but none exhibited distinctive rice husk or spikelet-base morphologies when imaged individually. Thus, given the absence of rice remains or other suitable organic materials within the sherd, it was not possible to obtain another AMS date for this sherd.

Figure 2. Virtual images showing clay (left) and organic (right) fractions within the older sherd, CAMS-725 (A–B) and the more recent sherd, CAMS-721 (C–D). The clay fraction is in brown, representing the external surface of a sherd. The organic fraction depicts in green all organic inclusions within a sherd (images by A. Barron).

We were able to assess the probable affiliation of the AMS-dated rice grain (CAMS-725) embedded on this sherd (Figure 1). Grain dimensions, as measured from the photograph, estimate a length/width (L/W) ratio of 2.86. Given the oblique angle of the grain in the photograph, this could be an overestimate. A ratio of 2.50 would probably be an underestimate based on likely length and width measurements of the grain. The true L/W ratio of this grain is likely to fall somewhere between 2.50 and 2.86, which is significant because L/W ratios in rice of subspecies japonica are usually less than 2.20 and not more than 2.50. Ratios greater than 2.50 are present in the subspecies indica and are typical of wild rice species (Castillo et al. Reference Castillo2016: fig. 8). Early examples of archaeological rice in Mainland Southeast Asia appear to be entirely of the subspecies japonica derived from domestication in China; the indica subspecies is unlikely to have been introduced before 2000 cal BP (Castillo Reference Castillo2011; Castillo et al. Reference Castillo2016, Reference Castillo, Higham, Miller, Chang, Douka, Higham and Fuller2018). Thus, considering the antiquity of the Gua Sireh context on Borneo, the morphology of this grain is consistent with a species of wild rice.

The more recent sherd (CAMS-721) contains abundant organic remains, including rice spikelet bases and husks (Figure 2). Fifty spikelet bases were individually rendered and visualised, with the intention of determining the domestication status of Oryza sativa inclusions (see ‘rice spikelet base visualisations’ in the OSM). The high levels of morphological detail preserved and the high scanning resolution enable virtual inspection of the abscission scar on each spikelet base. Of these, 70 per cent were determined to be of a domesticated type (n = 35; Figure 3A–C), four per cent were indeterminate (n = 2; Figure 3D), 22 per cent were wild type (n = 11; Figure 3E–F), and four per cent were derived from a different wild rice species (Oryza sp.; n = 2; Figure 4) (Table S2). The immature form was not present.

Figure 3. Visualisations of spikelet bases included within the more recent sherd (CAMS-721), illustrating the presence of domesticated types (A–C; inclusions 22, 23 and 32, respectively), an indeterminate type (D; inclusion 25) and wild types (E–F; inclusions 35 and 27). Visualisations of 50 spikelet-base inclusions within this sherd are provided in the online supplementary material (images by A. Barron).

Figure 4. Visualisation of spikelet bases included within the more recent sherd (CAMS-721), showing two spikelet bases derived from a non-AA genome wild rice species that was probably indigenous to Borneo (A–B; inclusions 17 and 29, respectively) (images by A. Barron).

Discussion

The re-analysis of the two Gua Sireh sherds demonstrates the value of microCT for investigating rice-associated pottery in Island Southeast Asia. The archaeobotanical evidence associated with putatively early sherds in the region comprises surface impressions and inclusions of rice husks within the pottery fabric. MicroCT is an efficient technique that makes it possible to visualise rice spikelet bases and other organic remains in 3D, where present, throughout the thickness of an entire sherd. The technique is not limited to surface analysis and does not require any breakage to retrieve archaeobotanical samples. MicroCT thus has the potential to revolutionise the investigation of plant domestication and dispersal in the past, by transforming individual pottery sherds into well-preserved archaeobotanical assemblages.

MicroCT analysis of the older sherd (CAMS-725) confirms that it was not rice-tempered. Aside from the single charred grain from the surface, no other inclusions or impressions of rice grains, husks or spikelet bases were found within the sherd, nor were they present on its exterior surfaces. The absence of any other rice remains within this sherd leaves two possible explanations for the presence of the single grain: either prior incorporation within the raw clay deposit or incidental inclusion during the manufacturing process. The embedded grain was originally identified as ‘carbonised rice’ due to the distinctive ‘checkerboard’ patterning on the husk (Bellwood et al. Reference Bellwood, Gillespie, Thompson, Vogel, Ardika and Datan1992). The absence of the spikelet base hinders determination of domestication status, while the estimated L/W ratio best corresponds with a wild type of rice. It should also be noted that, even if the grain's spikelet-base morphology could be assessed, little could be deduced about the domestication status of larger rice populations from a single specimen. The spikelet-base methodology for identifying domesticated rice relies on proportional counts of morphological types, and therefore requires both quantitative and qualitative evaluation. Conservatively, the grain attests to the presence of wild rice growing on Borneo c. 4960–3565 cal BP, but does not provide evidence for the introduction of rice cultivation from Mainland Southeast Asia at this time.

Sherd CAMS-721 contained abundant rice spikelet bases, of which 50 were imaged. The spikelet-base assemblage is consistent with that associated with the cultivation of domesticated rice (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009, Reference Fuller, Denham, Arroyo-Kalin, Lucas, Stevens, Qin, Allaby and Purugganan2014, Reference Fuller, Weisskopf and Castillo2016) in that it is dominated by domesticated types (70 per cent). In total, wild rice types represented 26 per cent of the assemblage, which suggests that weedy forms were harvested together with domesticated rice. These proportions of domesticated and wild types are broadly consistent with assemblages ranging from 5000–4000-year-old agricultural sites in China (20–25 per cent; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009) to Iron Age (c. 2500–1400 cal BP) sites in Thailand (2–12 per cent; Castillo et al. Reference Castillo2016: tab. 6). Thus, the assemblage within the more recent Gua Sireh sherd is consistent with its age of c. 2000–800 cal BP, namely the period during which open-field rice cultivation became widespread across Island Southeast Asia (Donohue & Denham Reference Donohue and Denham2010).

Significantly, the presence of two spikelet bases (4 per cent) derived from an unidentified wild rice species indicates the incidental exploitation of wild rice species potentially growing in plots alongside domesticated rice. In domesticated rice and its wild progenitors (Oryza rufipogon, sensu lato), the spikelet base attaches to the rachilla on one side. This seems to characterise the AA-genome groups within the genus Oryza (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1994), which include domesticated Asian rice and domesticated African rice, as well as wild relatives. In other Oryza species, however, the rachilla attaches from below, leading to a squatter spikelet base and an abscission scar at the attenuating base of the spikelet rather than on one side. This is typical of non-AA genome wild Oryza spp., comparable to Oryza officinalis (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Ling, Zhijun, Yunfei, Leo-Aoi, Xuguo and Guo-Ping2011: pl. 12.3). This trait is probably ancestral, as it is shared with related genera such as Zizania, Leersia and Hydrochloa (Weatherwax Reference Weatherwax1929), whereas the side attachment characterises wild and domesticated AA Oryza species. The two non-AA type spikelet bases in sherd CAMS-721 suggest the presence of indigenous wild rice species on Borneo (O. officinalis, O. meyeriana or O. ridleyi; Vaughan Reference Vaughan1994), which sometimes grow as weeds within domesticated rice plots, and can be harvested and processed along with domesticated rice. All are shade-tolerant species and can be expected to grow in plots adjacent to forest (Weisskopf et al. Reference Weisskopf, Harvey, Kingwell-Banham, Kajale, Mohanty and Fuller2014).

Conclusion

MicroCT analysis of pottery sherds is non-destructive and enables high-resolution visualisation of delicate organic remains preserved within hard, protective ceramic fabrics. The technique has great potential for the investigation of plant remains encased within sherds at sites where macrobotanical preservation may otherwise be poor, such as the wet tropics and some semi-arid and arid environments.

The re-analysis of sherds from Gua Sireh has clarified an anomaly of the Southeast Asian archaeological record, namely purported evidence of domestic rice on Borneo by 4960–3565 cal BP. The rice grain embedded in the sherd's surface (CAMS-725) probably represents the incidental inclusion of a native wild rice species growing locally on Borneo. The absence of suitable dating material precludes re-analysis of the age of this sherd.

The analysis of the more recent sherd (CAMS-721) demonstrates the suitability of microCT to image a large number of rice spikelet bases non-destructively, so that proportional quantitative counts of abscission scar morphologies can be compiled for a single sherd. High-resolution data were obtained for 50 spikelet bases within the sherd. Overall, this study demonstrates the potential of microCT to transform individual pottery sherds into well-preserved, as well as stratigraphically and temporally well-constrained, archaeobotanical assemblages.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Laboratory for X-ray Micro Computed Tomography at the Australian National University (ANU CTLab), particularly Levi Beeching and Michael Turner, for access to and use of CT scanning facilities, and Tim Senden, Research School of Physics and Engineering (ANU), for his continued guidance and support. Spikelet bases of multiple rice species were examined in the University College London archaeobotany reference collection. Thanks are also due to Richard Gillespie for sharing his images and recollections of previous dating protocols, and to Rebecca Esmay for her careful work pre-treating such a tiny sample for radiocarbon dating. This research is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT150100420). Many thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for greatly improving the manuscript.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.166