The presentation of archaeological sites is a central topic in public archaeology and heritage studies (Copeland Reference Copeland and Merriman2004; Grima Reference Grima and Moshenska2017; Smith Reference Smith2006). Accessibility, sustainability, and political and economic issues influence the ways in which a site is lived and perceived by the public. This relationship is even more stressed if it concerns an ongoing excavation project, where setting up outreach activities is only one voice in the research agenda. Although it has to deal with time and funding constraints, an ongoing excavation project offers the possibility of experimenting with new approaches.

This article focuses on the case study of Uomini e Cose a Vignale (Italy), an excavation project that has allowed experimentation with new approaches mainly due to two extraordinary traits: the duration of the project—more than 10 years—and an exceptional discovery, a huge mosaic from the fourth century AD. The first trait has supported the development of specific strategies for public outreach with the goals of raising awareness about the project and supporting the research funding. The combination of this first trait with the fascination with the discovered mosaic has encouraged the field team to question the existence of an emotional connection between the public and the archaeological site and to explore the potential benefits of an emotional approach.

Although there is still a lack of recognition of affect and emotion as essential constitutive elements of heritage-making (Smith and Waterton Reference Smith and Waterton2009:49), “emotion can be intimately linked to that feeling of a shared past that the antiquity of things and places has the potential to stir in every individual” (Fortuna Reference Fortuna2013:110) and “validates the way visitors engaged or disengaged with the information contained in exhibitions and heritages sites” (Smith and Campbell Reference Smith, Campbell, Logan, Craith and Kockel2015:449). In the last few years, there has been a growing interest in how emotions are recruited, molded, and used in contemporary processes of drawing on the past to effect the present from social, cultural, and ideological points of view. For example, some essays on the subject have been published (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Smith and Wetherell2017; Smith and Campbell Reference Smith, Campbell, Logan, Craith and Kockel2015; Wetherell Reference Wetherell2012); an ongoing European Union–funded heritage project called EMOTIVE, which aims to use emotional storytelling to change how we experience heritage sites, began in 2016 (http://www.emotiveproject.eu/); and two volumes of related scholarship were recently published (Tolia-Kelly et al. Reference Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, Watson, Tolia-Kelly, Waterton and Watson2017; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Wetherell and Campbell2018). Tolia-Kelly and colleagues stress that “the notion of affecting heritage will play out in myriad ways” (2017:3).

This essay describes three public activities carried out in Vignale and a preliminary analysis of the public feedback. Since an emotional connection emerged, we will focus on how we might build upon these responses for the benefit of both the archaeological project and its stakeholders. Moreover, the article aims to show how these activities followed two different lines of promotion of the project, on-site and off-site, allowing for the involvement of different audiences. As a matter of fact, one of the main concerns of archaeology today is maximizing the value of the archaeological resource—its sites, materials, and knowledge—to the public, as archaeologists seek to make heritage relevant, especially to local communities (see overview in Smith and Waterton Reference Smith and Waterton2009). There are many ways to do this, and one is to invest in emotions.

The first section provides an overview of the project and introduces the discovery of the mosaic. The second section is dedicated to a description of the events concerning the archaeological site of Vignale. The presentation of the data related to the events will provide some insights about the visitors’ feedback. The third section will deal with the results of the preliminary analysis and the value that emotions might have in an ongoing excavation project.

SM, FR

AN OVERVIEW OF THE RESEARCH PROJECT

Vignale is an archaeological site on the coast of Tuscany, situated in the Municipality of Piombino (Livorno), in a territory called Val di Cornia (Figure 1). The area of the archaeological site is divided into two parts by a main road, SP39 Aurelia (Figure 2), and it is situated near the village of Riotorto. The site was occupied from the third century BC to the sixth century AD and even later. The most notable buildings at the site are a Roman posting station (mansio) and villa (Giorgi Reference Giorgi, Basso and Zanini2016; Giorgi and Zanini Reference Giorgi and Zanini2014).

FIGURE 1. Location of Riotorto, near the site of the Vignale project in Tuscany, Italy.

FIGURE 2. Archaeological site of Vignale (photo by IS Piombino).

The property on which the archaeological site of Vignale is located is owned by Tenuta di Vignale, an agricultural holding that produces oil and wine. In 2003, Tenuta di Vignale started to set up a vineyard, but Roman walls emerged from the soil, and as a consequence, the project was aborted. According to Italian law, ancient remains lying under the soil belong to the state. In this case, the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio and Tenuta di Vignale made a formal agreement: archaeologists can investigate the site, while the field, still the property of Tenuta di Vignale, is used for grazing.

Since 2005, a team from the University of Siena (Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche e dei Beni Culturali), supervised by Professor Enrico Zanini and Dr. Elisabetta Giorgi, has been conducting the project Uomini e Cose a Vignale (People and Things at Vignale). Excavation seasons of four to five weeks were conducted in September and October as field schools for university students. We have been part of the team since 2006 and 2007. Initially the research project was funded by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Tourism and the university; over the years, a growing number of stakeholders have supported the archaeological investigation by providing in-kind contributions on a voluntary basis, including accommodations and food for the field team. A network of local associations, mainly based in Riotorto, actively support the organization of outreach activities, having found in the archaeological project an appropriate environment for developing their own interests.

Riotorto dates to the nineteenth century, and because of its recent foundation, the inhabitants do not feel that their identity is deeply rooted in the past. Over the years, the excavation project has played an increasingly important role as a place where local residents can experience the past. Thanks to the interest of a local politician, to interaction with a local school, and, above all, to the proximity to SP39 Aurelia, since 2007 the interaction between the locals and the archaeologists has increased. Drivers on SP39 Aurelia see the archaeologists working very close to the road and often decide to take a break to inquire about the activities in progress. This has brought many people to the site and has required the archaeologists to think about effective approaches to interaction with the public, other than the traditional guided tour. Their ability to present the site is affected by its poor state of preservation—due to repeated plowings over the centuries—and by the shape and functions of the ancient posting station, which are unfamiliar to most visitors. For these reasons, archaeologists sought creative outreach solutions (Mariotti et al. Reference Mariotti, Marotta, Ripanti, Basso and Zanini2016).

The approach resulted in “Excava(c)tion,” a communication strategy that conceives the site as a stage and digging as a performance (as defined in Pearson and Shanks Reference Pearson and Shanks2001), through a continuous dialogue between archaeologists and the public. Two types of performances are the core of “Excava(c)tion” (Costa and Ripanti Reference Costa and Ripanti2013): live and online. The latter have been available on YouTube since 2011 (https://www.youtube.com/user/UominieCoseaVignale/) and on our website since 2015 (http://www.uominiecoseavignale.it/). Over the years, many public projects have been developed at the archaeological site. Depending on the audience, we propose dedicated activities:

• laboratories and didactic works for children, either on-site and in the classroom

• thematic dinners set in Roman times

• archaeological hikes

• theatrical performances and docudramas

Uomini e Cose a Vignale has progressively extended the ways in which the community engages in the research, combining the scientific project with a strong social value (Mariotti et al. Reference Mariotti, Marotta, Ripanti, Basso and Zanini2016).

FR

AN UNPREDICTABLE VARIABLE: AN EXTRAORDINARY DISCOVERY

The 2014 excavation season started with an extraordinary discovery: a polychrome mosaic of 100 m2 depicting Aion, the God of Time, surrounded by the Four Seasons at the center of three figurative panels (Figure 3). A coin of Constantine (AD 324–330) found in the preparatory layer permitted archaeologists to date the mosaic to the first half of the fourth century (Giorgi and Zanini Reference Giorgi and Zanini2015, Reference Giorgi, Basso and Zanini2016). The exceptional nature of the finding was immediately clear: the richness and the high artistic quality of the decoration had no comparison among other late antique mosaics in central Italy.

FIGURE 3. Mosaic discovered in 2014 (photo by IS Piombino).

This unexpected find benefited the research in multiple ways. It confirmed the site as a prestigious residence owned by an important dominus of his time (Giorgi Reference Giorgi, Basso and Zanini2016:178). On the other hand, it also became an opportunity to explore both how much local communities can be affected by archaeological activities and how they relate and react to the discovery of such a surprising artifact.

During the 10 previous years of research in Vignale, archaeologists had been unearthing and exploring a conspicuous part of the ancient remains, but the deep plowing activity carried on in the field over the previous centuries had affected site preservation and consequently people's perception of the site (Mariotti et al. Reference Mariotti, Marotta, Ripanti, Basso and Zanini2016:254). When the mosaic finally popped up, the previous effort in explaining and communicating the nature of the structures and their meanings was almost unnecessary: its enormous archaeological and artistic value was so clear that it needed no explanation.

The news of the discovery spread quickly, initially through word of mouth and then through regular and enthusiastic coverage by the local media. More people started coming to the site daily (for an estimated average of 30 people per day), sometimes more than once in a day, to observe new developments. Children and teens were once again a big part of our public: during the 2015 excavation season, the whole mosaic area was finally unearthed, and in just 16 working days, we received visits from 19 primary, secondary, and high school classes.

The local municipality, for its part, kept assuring us its support too. Since the mosaic area was localized outside the fenced area of the site—very close to the main road—it granted us the use of a mobile fence to ensure the protection of the mosaic during the night.

From the very first moments of its discovery, people recognized the mosaic as an important and representative symbol of their community's past, something that was fragile and needed to be protected. They immediately felt deeply invested in the primary management of the discovery both as individuals and as part of the associational network that was active in the local social system.

As the mosaic floor kept emerging from the earth, we did not think about what could happen next: we could not know and we did not much care, as the unexpected emotion of the discovery had completely absorbed us. But even without any precise awareness, the discovery of the mosaic began a new and upgraded phase of involvement by different members of the local community.

SM

TELL STORIES, CONVEY EMOTIONS

The discovery of the mosaic was a major turning point for the archaeological project, even from the point of view of outreach activities. Now Vignale had something really fascinating and easy to understand in the eyes of visitors. A room with a mosaic is clearly comprehensible; merely looking at it opens up new potential for narration and engagement.

Our main goal was no longer to explain to visitors what they were looking at but, rather, to reveal to them the artistic importance of the mosaic and its surprising story. The best way to reach these goals was to improve “Excava(c)tion” and, especially, to adapt the live performances to this new purpose. To perform a story in front of the public means to convey archaeological knowledge in a way that involves and resonates with people, leaving them with a stronger memory of the experience.

Offering a performance based on the archaeological research was not a new challenge for the field team. Between 2008 and 2013, the most time-demanding communication activity was the production of docudramas. These are amateur short films conceived as “micro-stories,” set both in the past and in the present (Ripanti and Osti Reference Ripanti, Osti, Witcher and Van Helden2018; Zanini and Ripanti Reference Zanini and Ripanti2012). They were interpreted by the same archaeologists who were digging the site and were produced with the intent to narrate the results of the current excavation season to the local community. Docudramas were usually shown at the end of each campaign, at a public conference or during a dinner organized by local associations. Because of this experiment, the field team understood the great potential of reenacted stories in arousing curiosity and eliciting emotional responses.

Before the discovery of the mosaic, we had also engaged in some shared projects and initiatives bearing a strong emotive response. The most significant for us was Giù le mani dalla nostra storia (Get your hands off of our history), conducted in partnership with a class of 10-year-old children. Schools from the nearby territory enjoyed didactic activities on the site, and we archaeologists went to schools to introduce our work. In September 2013, the project suffered from an act of vandalism. Unexpectedly, the class proposed that we, together, record an antilooting video. We accepted the challenge. The children wrote the script, and the video was recorded by the field team. The main message is that nothing of “monetary” value is stored in the warehouse and that digging random holes in the site only damages our common history. It was shown in a cinema in Piombino and, with 1,043 views, was the second-most popular video on the project's YouTube channel (https://youtu.be/zB6WCei8WQw). Above all, it was evidence of the strong relationship forged with the local school in these years.

The commitment to live performances and the involvement of citizens increased with the discovery of the mosaic; our good relationships with local communities, associations, and schools; and the support of the municipality and of some local companies, combined with the desire and determination of the field team to keep opening the excavation and telling its stories. In 2014 four archaeologists from the team (including us) founded M(u)ovimenti, a dedicated cultural association that has the management of the outreach activities of Uomini e Cose a Vignale among its main goals. M(u)ovimenti plans and coordinates events, acting as a facilitator among the field team and the associations organizing various activities. M(u)ovimenti is also responsible for collecting donations in a broad sense. Since the live performances were conceived as single events, visitors were not required to pay a fixed entrance fee but could make a voluntary donation. In this way they could support the research project.

Events

To give a brief idea of the changes in our public outreach strategy after the discovery of the mosaic, a detailed presentation of three emblematic events and the related data follow. These events provide a sense of both the context and the opportunities and challenges of managing an outstanding discovery with local citizens.

Colorare un'emozione (Color an emotion) was the first program set up after the discovery of the mosaic. Its purpose was mostly to promote fund-raising to finance the early stages of consolidation of the mosaic. The initiative took place during the Sagra del Carciofo, a deeply rooted local festival dedicated to the artichoke and organized by Associazione Cultura e Spettacolo for the past 48 years. The field team and M(u)ovimenti assisted with the festival logistics and promoted the project with a stand. In 2015, the archaeologists hung up a black-and-white poster of the mosaic. By donating 1€ a visitor could color a tessera of the mosaic and write his or her name beside it (Figure 4). In 2016, we repeated the initiative, adding a life-size poster depicting Aion with the slogan “Il Signore del Tempo ha contagiato anche me!” (The God of Time is heritage of mine!), to encourage people to take selfies with the god.

FIGURE 4. Field Director Enrico Zanini showing how coloring a tessera worked during the Colorare un'emozione initiative (photo by Elisabetta Giorgi).

Una notte a Vignale (A night in Vignale) is a series of events set in different excavation seasons. The event starts in late afternoon with a performance, followed by a dinner outside the site fence. The field team sets up the performance, and two local associations organize the dinner. The performances have a different theme every year, inspired by the ongoing investigations. In 2014, a theatrical play involving both archaeologists and professional actors took place in four different areas under excavation (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Scene from Una notte a Vignale (photo by Francesco Ripanti).

In 2015, the core of “Una notte di luce” (A night of light) was a suggestive guided tour of the mosaic, lit by a lighting truss. In 2016, “Ancora una notte a Vignale” (Another night in Vignale) narrated the stories of the 10 most interesting objects found in Vignale over the years. Ten panels showed a photo and a brief description of each object. In the first part of the event, visitors listened to the story of each finding, told by the voices of archaeologists recorded in audio files and broadcast via a public address system. At the end of the performance, the archaeologists who had told the story were at the public's disposal, standing beside the panels to answer questions.

In 2017, “Il Mosaico del Granduca” (The mosaic of the Grand Duke) told the story of the nineteenth-century excavation managed by Grand Duke Leopold II and his engineer Alessandro Manetti. Archaeologists performed three scenes set between 1830 and 1835; three brief dialogues between a current young archaeologist and an expert opened each scene. The questions of the young archaeologist found answers in the subsequent scene.

In the first the Grand Duke talks with Manetti, who is in charge of planning the route of a new road (the modern Aurelia); they are unaware that the new road is going to cross the ancient remnants of the site. In the second scene Manetti shows the mosaic to the Grand Duke. In the third the Grand Duke makes an agreement with Lelio Franceschi, the owner of the field, to build a room aimed at preserving the mosaic. The shifting of time was emphasized with different lights: LED lights for the scenes set nowadays and torches for the scenes set in the nineteenth century.

Poderando is a series of events set up by a local association, Trekking Riotorto, with a fixed format: the participants pay a fee to go hiking in the Natural Park of Montioni. There are checkpoints along the track, and at each, local associations and wineries provide food and drinks. In “Poderando incontra l'archeologia” (Poderando meets archaeology) and in “Poderando e la visita al mosaico del Signore del Tempo di Vignale” (Poderando and the visit to the mosaic of the God of Time of Vignale), set up in 2015 and 2017, respectively, Vignale was the most important stop on the trek thanks to the fascination with the mosaic.

Poderando provided a high number of visitors in comparison with the normal standards for an excavation such as Vignale. We had 1,200 visitors in one day in 2015 and 600 in 2017. To manage this flow of people, the field team defined some fixed checkpoints: an introduction to the project at the entrance, the farm, the posting station (mansio) and the villa, and finally the mosaic. An archaeologist was present at each checkpoint and gave a guided tour to groups of about 20 people. Other archaeologists led the groups from checkpoint to checkpoint. At the end of the track, M(u)ovimenti ran a stand for spontaneous contributions.

Data

Part of Francesco Ripanti's doctoral project has been concerned with studying the participation of the visitors at the events organized in 2016 and 2017 in Vignale with both quantitative and qualitative research. The former is best suited to answering questions about how many people did or thought something. The latter enables one to address deeper questions, such as why people did or did not like something (Research Councils UK 2011). In this case a combination of both approaches has been used.

No data were collected with proper methods from the early event Colorare un'emozione. Nevertheless, it showed positive outcomes: the early stages of mosaic consolidation were successfully funded, and the feedback provided by the participants was surprising. Children and adults asked for particular options, such as coloring specific tesserae: “Can I color the bunch of grapes in the hand of the Autumn?” Others called by phone to try to reserve parts of the mosaic: “Can I book the head of Aion?” We interpreted these behaviors as initial evidence of an emotive attachment to the mosaic.

For the four successive events, including Poderando and “Il Mosaico del Granduca,” 287 questionnaires were collected.Footnote 1 Among the information that was collected through the questionnaires, three sets of data are used to support the aims of this essay.

The first set of data concerns the analysis of the open-ended questions: they provide some valuable insights for understanding whether an emotional connection was achieved.Footnote 2 Focusing on “Il Mosaico del Granduca,” 35 visitors stressed three main themes: story, performance, and emotional connection (Figure 6). The predominance of “performance” supports the respondents’ appreciation of the theatrical play: it describes what each person saw. “Story” stresses a major interest in the facts represented. “Emotional connection” attests that the overall effect of the play gave rise to an emotional feeling. The most used words were atmosphere, passion, and emotion.

FIGURE 6. Responses (n = 35) to the question “What positively impressed you most about the event?” for “Il Mosaico del Granduca.”

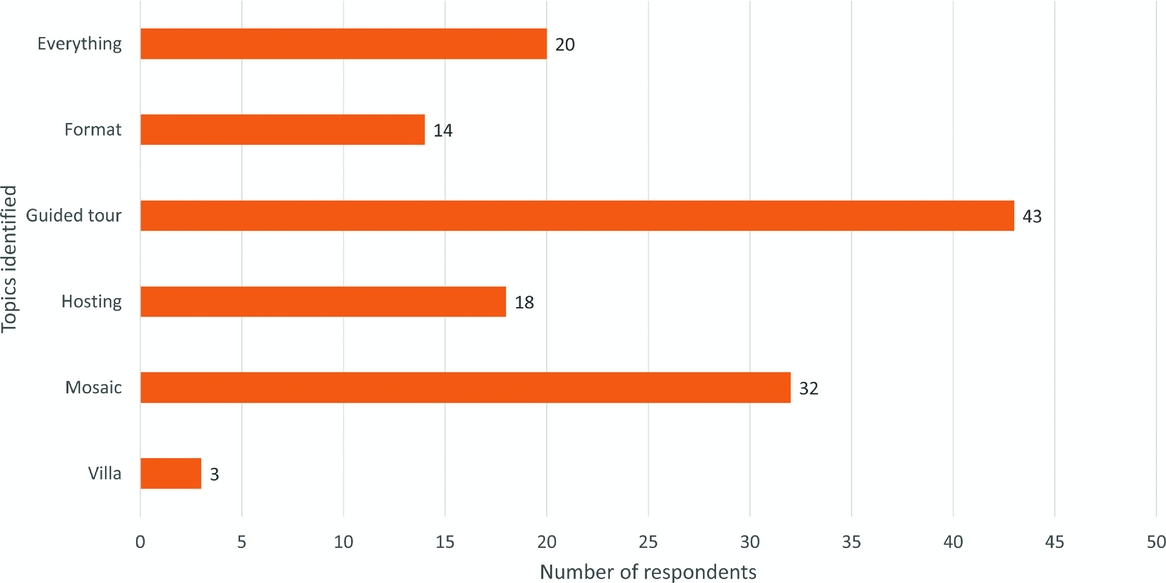

The same open-ended questions provide very different feedback about Poderando (Figure 7).Footnote 3 Responses from 130 visitors stressed six main themes, and their choices relate mostly to the main components of the event: the logistics (format, guided tours, and hosting) and the contents of the visit (mosaic and villa). Emotional connection was not explicitly mentioned.

FIGURE 7. Responses (n = 130) to the question “What positively impressed you most about the event?” for Poderando.

The second and third sets of data regard the percentage of new visitors taking part at each event and the provenance of the visitors (Figures 8 and 9). Poderando shows a higher percentage (76%) of visitors coming to the site for the first time than “Il Mosaico del Granduca” and “Ancora una notte a Vignale.” In regard to the latter set of data, the provenance information states that the events in Vignale involved the local public (located in the provinces of Livorno and Grosseto) above all, with small groups of visitors coming from central and northern Italy.

FIGURE 8. Responses to the question “Is this the first time you took part in one of our events?” Left: Ancora una notte a Vignale (n = 41); center: “Il Mosaico del Granduca” (n = 47); right: Poderando (n = 147).

FIGURE 9. Provenance per province of the visitors taking part in the four events analyzed (n = 288).

FR

EXPLORING THE VALUE OF EMOTIONS IN VIGNALE

The different kinds of relationships and collaborations set up over the years have influenced our ways of promoting the archaeological project and of capitalizing on the value attached to the site. At present, the promotion of the site follows two fixed avenues: on-site and off-site. The former is a top-down approach that allows us to plan activities according to our preferences and goals. For example, in “Il Mosaico del Granduca,” the performance was set just outside the mosaic area: there, a group of archaeologists formed a chorus who performed a well-known traditional song, “Maremma amara,” originally sung by the wives of the workers who built the new road in 1830, at the time of the first discovery of the mosaic. With the song and other techniques we sought to involve the public. As shown in Figure 6, besides mentioning the performance, the respondents from “Il Mosaico del Granduca” implied an emotional connection with the site. The combination of the display of the mosaic, the well-organized and detailed planning, and the rendition of “Maremma amara” helped in striking a chord with the audience.

When setting up a public outreach initiative on-site it is clear that the display of an exceptional find such as the mosaic plays a major role in fascinating attendees. Its attractive power can be inferred using Figure 8: as can be seen, in a comparison between the left and center pie graphs in Figure 8, the percentage of respondents taking part in our events for the first time was about one-third higher for “Il Mosaico del Granduca” than for “Ancora una notte a Vignale,” when the mosaic was not visible.

The second line of promoting Uomini e Cose a Vignale is off-site: when the fieldwork is closed, we move elsewhere to keep on publicizing the project. Since on these occasions we respond to invitations made by external organizers, a bottom-up approach works as an impetus. Such events help us to enter the local community and, by being a part of it, show our engagement. Taking part in such popular festivals as the Sagra del Carciofo helps to enlarge our audience. Even if we cannot support this statement with data, Colorare un'emozione was an effective way to make people aware of our project and to collect donations toward the consolidation of the mosaic, even though participants were at the festival for other purposes.

Poderando lies at the intersection of these two avenues: it is planned and organized by Trekking Riotorto, but a part of it is carried out on-site. Figure 7 shows some positive impressions related to various aspects of the event but no specific mentions regarding emotions. In comparison with “Il Mosaico del Granduca,” in Poderando we cannot plan everything in advance: the site is just the last checkpoint of the day, people usually arrive in big groups, and the time dedicated to introducing them to the site is usually limited. It is likely that the positive feedback depended to a large extent on the ability of we archaeologists to stimulate participants’ curiosity about a place that many of them were visiting for the first time. Consequently, the kinds of connections established with the public in Poderando are different from those in “Il Mosaico del Granduca.”

Figure 8 (center and left) shows that the percentage of respondents taking part in our events for the first time was yet another third higher for Poderando than for “Il Mosaico del Granduca.” Trekking Riotorto is a very active association and is very well known in Val di Cornia: therefore, it is rather clear that the organization of events managed by an external association has allowed us to expand the audience interested in our work.

According to this preliminary analysis, two different kinds of considerations can be made. In the line on-site, an emotional connection has been detected and deserves further study and elaboration in the future with more specific analyses. The different avenues stimulate different connections with the site, and from now on, we have to think about the ways in which we can capitalize on these connections.

These different approaches, based on the harmonization of the archaeological activity or event with different types of contexts, publics, and potential goals, can potentially be adapted to other archaeological experiences dealing with the engagement of local communities. The development of different lines of promotion allows encounters with new audiences and with new and diverse requests for valuing heritage.

Our visitors have told us: “Thank you because you tell us the stories we need.” We have become confident that our work is oriented in the right direction: archaeology in this sense can offer both intellectual challenge and emotional connection (Henson Reference Henson and Moshenska2017:45). As a result, an archaeological site that elicits emotions in the visitor will later turn into memories, and having this experience in a specific place can create a sense of belonging and contribute to the forging of an identity (Smith Reference Smith2006:83).

The crisis of the local steel industry of Piombino deeply affected the whole Val di Cornia area and caused a major rethinking and rebuilding of community needs, priorities, and also identity (Tonarelli Reference Tonarelli2016). In a context of this kind we are forced to reflect upon the concept of “value” referred to in archaeological heritage (Carman Reference Carman2005:20–24). As Mason (Reference Mason, Fairclough, Harrison, Jameson and Schofield2008a:104–107) states, the term value can have both sociocultural and economic meanings, which may appear to contradict each other (Burtenshaw Reference Burtenshaw2014:52; Gould and Burtenshaw Reference Gould and Burtenshaw2014:3–5; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Ashworth and Tunbridge2000:129).

As archaeologists, we have to accept that “even if the cultural values of heritage are key for conservation advocates, they are not the most important ones for everybody” (Mason Reference Mason2008b:309). For some, a particular site might be significant because it gives them a job; for others, it may be connected to their memories, or they may recognize its strong educational value; or it is a beautiful place to spend some spare time, or it represents the identity of their territory and the heritage of their country, even if they never visit it. In this large variety of cases, and if we consider every citizen a stakeholder, as it should be (as intended in Council of Europe 2005), emotive connection plays an enormous role: if people cannot perceive how archaeology can relate to their lives, a concurrent lack of interest and support will always persist (Merriman Reference Merriman and Southworth1989:23; Schadla-Hall Reference Schadla-Hall1999; Schadla-Hall and Larkin Reference Schadla-Hall and Larkin2014). Being more specific, as Holtorf points out, heritage value for communities is closely related to its “metaphorical content,” that is, its ability to evoke both “stories about the visitors themselves” and “stories that reaffirm various collective identities” (Reference Holtorf, Smith, Messenger and Soderland2010:43). In this sense, heritage is considered meaningful because it confirms communities’ idea of their past and reinforces their sense of belonging.

Referring to the typology of heritage values provided by Mason (Reference Mason, Fairclough, Harrison, Jameson and Schofield2008a:103), in our case emotions influenced both sociocultural and economic values. The activities described and the people's support (intended as both moral and economic) came naturally when we started communicating not only the mere archaeological data but also the human side of the site. The name of our project is closely concerned with these aspects.

Since the site is located in a tourist area, the connection between communities and their past could have material consequences for their identity, sense of belonging (see Smith Reference Smith2006:83, Reference Smith2014:125), and even economic development (as examined by Gould and Paterlini [Reference Gould, Paterlini, Gould and Pyburn2017] in their study about the management of the archaeological and natural park system of the Val di Cornia). Recently, a new project affecting economic heritage value has started. “Villa del Mosaico” (after the name by which the field was known even before the beginning of the excavation) was launched in April 2017 by Azienda Agricola Tenuta di Vignale, the agricultural holding that owns of the field where the archaeological site is located. Tenuta di Vignale proposed a collaboration concerning the production of the red wine “Villa del Mosaico” and the vermentino “Campo degli Albicocchi” (Figure 10). The bottles show the logo of the archaeological project on the front label and a description of it with a QR code that links to the Uomini e Cose a Vignale website on the back label. Members of local communities, the Municipality of Piombino, and the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the provinces of Pisa and Livorno endorsed the project for its potential to promote both archaeology and local products, as well as to create a specific tourist identity. Thanks to this collaboration, the new series of wine is being widely distributed: some thousand bottles were sold in six months, and the archaeological project receives a percentage of the sales. The project, as it is conceived, could provide economic income and long-term social benefits; moreover, the economic effect resulting from an archaeological research project could be observed and measured in future years.

FIGURE 10. Bottles of the red wine “Villa del Mosaico” and the vermentino “Campo degli Albicocchi” (photo by Francesco Ripanti).

Furthermore, this experience could become the first of a series of collaborations with local producers that could lead to the creation of a network of local stakeholders. This kind of business, in this perspective, could benefit from cultural involvement that would increase its appeal and contribute to the development of local tourism; at the same time, they could be engaged in the management of a public archaeology project. In this case, archaeology could really become an economic asset (as defined in Burtenshaw Reference Burtenshaw and Moshenska2017:37–41).

SM

FINAL THOUGHTS

The presentation of the site with creative approaches on-site and off-site and the development of different kinds of relationships with local society were ongoing processes before the discovery of the mosaic. That exceptional event amplified these processes: in a short time, the mosaic became the material element around which a huge amount of curiosity and expectations focused. The mosaic positively affected the presentation of the site: we consolidated the on-site and off-site lines of promotion, thanks to the initiative of some local associations in supporting the events we planned and in inviting us to the events they organized. In both cases, our effort was focused on narrating the outstanding story of the mosaic and on finding a connection with the public—transforming the “intellectual” sentiment of the discovery into a shared and valuable emotion for the benefit of both the archaeological project and its stakeholders.

From now on, we can plan our next steps with a new awareness: as described in the preliminary analysis, it is possible to strike the right chord with the public when certain conditions occur. We believe that emotions can affect both the sociocultural and the economic value of archaeology: further analyses and studies need to specify the kinds of emotional connections that occurred and to assess the emotional impacts of public outreach activities and projects such as the production of “Villa del Mosaico.”

SM, FR

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Enrico Zanini for his comments while writing this essay, the editors of the journal and the guest editors of this special issue for their invitation and support, the anonymous reviewers for their critiques and insights, and Giulia Osti and Mireia Alcantara Rodriguez for help translating the abstract into Spanish. We would also like to thank the field teams that have worked at Vignale over years. This work would not be possible without the great willingness of every archaeologist who has taken part in the project. Moreover, we can never be grateful enough to the local communities for their contagious enthusiasm and enormous support over the years. No permit was required for the work.

Data Availability Statement

All new data are presented in the text.