Introduction

Credit transactions are specific types of forward-looking economic operations: they entail an obligation to repay, and create a thick temporality through lasting relationships between lenders and borrowers. While many forms of market exchanges display duration through repetition [Gulati Reference Gulati1995; Uzzi Reference Uzzi1999], in the case of credit, the obligation is formally or morally defined (through a contract, embeddedness within interpersonal networks, psychological trust) from the beginning: lenders require a collateral, thus giving value to a specific form of debt, and they set aside a portion of the loan (a rate) to cover the risk and the disutility of foregoing an amount of money for a time. Hence, on top of two required characteristics—a price and a collateral—lenders also need to build “fictional expectations” [Beckert Reference Beckert2013] about negative scenarios, such as consumer default, and their ability to enforce repayment, whether through physical or political force or, in many common market operations, through civil courts. Credit transactions therefore imply different levels of “legal coding” [Pistor Reference Pistor2019]: a loan is a specific type of financial asset which requires the selection of a legal framework, a method to price the future [Black Reference Black2013; Deringer Reference Deringer2017] and a type of collateralization. Focusing on the regulation of unsecured loans in the United States, we trace the evolution of these three legal outcomes between 1903 and 1945: these define institutional configurations whose transformation was driven by legal struggles between political reformers and various market players. In order to characterize this evolution, we suggest the concept of regulatory differentiation: in the early 1900s, state usury laws remained relatively similar, but the indeterminacy raised by salary loans triggered local conflicts, which gradually shaped credit markets and organizational hierarchies within this nascent field. This ecology further differentiated until the mid-1940s, despite the various attempts at uniformization, as consumer credit progressively became the subject of federal policy-making.

Unsecured loans to consumers are, paradoxically, not devoid of collateral but rely on future revenues as security, as opposed to material property such as goods, furniture or houses. In the late 19th century, a shift occurred as labor income, in the form of wages or salariesFootnote 1, became secure enough to enable workers to access credit on the sole basis of their current occupation. The ecology of unsecured lending was diversified and shifting: in the Appendix, we provide an overview of its evolution during the first half of the century. Nowadays, this type of credit includes a wider range of operationsFootnote 2, and risk evaluation has been mostly reduced to a unique quantified instrument, in the form of a credit score [Poon Reference Poon2009; Lauer Reference Lauer2017]. However, employment still represents the underlying force driving this form of credit, as wages constitute the primary asset of most consumers, generating a flow of future earnings. In order for workers’ labor assets to be coded into capital, lenders need to evaluate the “discounted” present value of this income stream and design specific devices to ensure repayment or garnish wages. Historically, turning future, virtual wages into capital was not only the result of industrial, technological or cultural evolutions, but the outcome of long-term legal and political processes involving conflicts between credit companies and Progressive movements, as well as between lending organizations. Most controversies pertained to the legal status of “salary advances,” a type of transaction where workers assigned their future income in exchange for short-term credit [Soederberg Reference Soederberg2014: 72-73]: lenders continuously argued that these were not “loans” but wage “sales,” a position strongly opposed by reformers seeking to build a modern national credit market. As Fourcade and Healy [Reference Fourcade and Healy2007] have put it, focusing on this type of “conflict over meaning opens the prospect of linking local battles over particular transactions with large-scale shifts in categories of worth”.

Carruthers and Stinchcombe [Reference Carruthers Bruce and Stinchcombe1999] were the first to present the liquidity of financial assets as a problem in the sociology of knowledge, when “facts about future income streams become sufficiently standardized and formalized, so that people know they can be bought and sold on a continuous basis”. These processes of “capitalization” have been at the center of many recent sciences and technology studies (STS) [Doganova Reference Doganova2014; Birch Reference Birch2017; Deringer Reference Deringer2017; Muniesa et al. Reference Muniesa, Doganova, Ortiz, Pina-Stranger, Paterson, Bourgoin, Ehrenstein, Juven, Pontille, Sarac-Lesavre and Yon2017; Birch and Muniesa Reference Birch and Muniesa2020], focusing on industries where future expectations drive investment choices, such as finance, venture capital or biotechnology. While this trend of critical finance studies greatly helps in understanding the centrality of such processes for techno-scientific capitalism, this body of research has largely overlooked law and regulatory compliance as central mechanisms in shaping financial marketsFootnote 3. Indeed, creating capital is not only about “knowing” the future, manipulating technologies or providing the right script to convince market actors to act in the present. These frequently interact with regulators and courts, striving to impose contractual devices or metrics supporting the creation or exchange of assets, giving rise to conflicts which often play out in legal terms.

Regulating Credit Markets: From State Arenas to Federal Policymaking

A vast body of research has shown that law is far from an external body of rules governing financial activities: the impact of legal reforms, or regulatory attempts, on market responses depends on the reaction and intervention of organizations, courts and social movements as well as the interpretive conflicts between these various stakeholders [Edelman and Stryker Reference Edelman, Stryker, Smelser and Swedberg2005; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2009; Black Reference Black2013]. This is particularly true for financial markets, which are frequently prone to rule bending or eviction: understanding regulatory processes therefore requires the adoption of a “relational approach” [Gray and Silbey Reference Gray and Silbey2014; Thiemann and Lepoutre Reference Thiemann and Lepoutre2017], focusing on interactions between market actors and those seeking to implement reforms or bend organizational routines.

In this regard, a first set of research has relied on the concept of “legal endogeneity,” which specifically captures a type of private power where organizational rules or practices shape the interpretation of legal principles [Dobbin Reference Dobbin2009; Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Krieger, Eliason, Albiston and Mellema2011]. As rule implementation is both a site of “overt political contestation” and “covert institutional diffusion” [Edelman and Stryker Reference Edelman, Stryker, Smelser and Swedberg2005: 542], this approach emphasizes the organizational resources that market actors and social movements devote to slant downstream interpretations. However, simultaneously, this approach leaves little room for discussions and interactions between regulators and the regulated, restricting stakeholders to their respective capacity to implement and circumvent rules. Filling this gap, a second approach has shown that compliance depends not only on distant conflicts between organizations and courts or legislators, but on the density of ties between regulators and market actors [McCaffrey, Smith and Martinez-Moyano Reference McCaffrey, Smith and Martinez-Moyano2007]. As Thiemann and Lepoutre [Reference Thiemann and Lepoutre2017] have argued, expert networks function as “interpretive communities,” where market responses are determined by local discussions over the “meaning of compliance”. While this hermeneutic perspective reintroduces relations between competing social groups, it also tends to undermine the propensity of these interactions to result in conflict, as the technicity of expert discussions often prevents or supersedes the possibility of judiciary resolution.

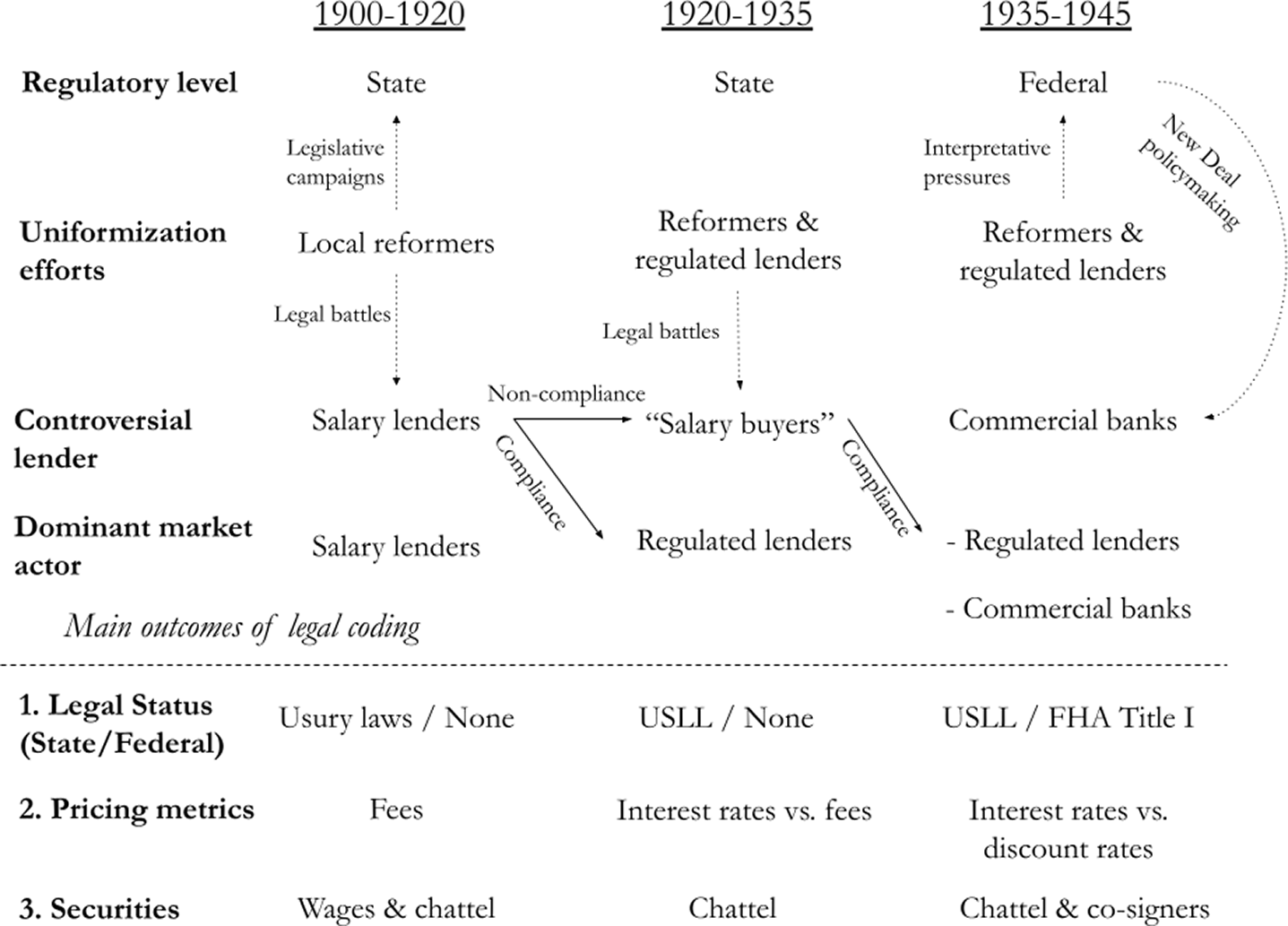

Building on these two approaches, this article adopts a more longitudinal perspective, studying a process of historical differentiation: as consumer credit laws were discussed and then implemented at the state level, multiple power struggles between regulators and lending companies determined distinct legal outcomes as well as local credit market configurations. These state level interpretations were driven both by discussions between market actors and local reformers, within regulatory networks, and through legal battles over rule evasion, carried out within lower, and sometimes higher, courts. More specifically, we show that the initial power balance between elite reformist groups and salary lenders led to a plurality of legal decisions through the 1900s (I), which in turn set various states on diverging regulatory paths throughout the 1910s and 1920s (II). Finally, the New Deal policies of the 1930s partly shifted policy power away from states and to the federal level. And, whereas lending companies and Progressive reformers had partly failed to produce a universal model of wage-based loans, commercial banks succeeded in superimposing their organizational model over the existing heterogeneity (III), in part by keeping the controversial discussions within expert circles.

The history of unsecured consumer loans illustrates the effect of regulatory differentiation on market structure, which allows us to make two contributions to the “relational perspective” on law and finance. First, we extend the literature on regulatory compliance to legal pluralism: whereas the “legal endogeneity” approach has mostly focused on uniform federal employment law, we shift the focus to more granular conflicts, looking at strategies, resources and political opportunities exploited by rival actors to shape wage credit markets. Second, we show that this process not only produced varying levels of compliance; it also contributed to the segmentation of consumer credit markets: as both reformers and lenders strove towards uniformization, with limited success, several strata of legal coding continued to coexist—between states but also between state and federal levels—shaping interorganizational hierarchies within the field.

Case Selection for the Comparative-Historical Approach

The case analysis focuses primarily on for-profit and non-bank credit companies, in the first two sections, and their opposition with commercial banks in the third; while we touch upon the history of the two secondary providers of unsecured loans at the time—credit unions and Morris Plan banks—their credit models raised distinct regulatory issues, outside the scope of this studyFootnote 4.

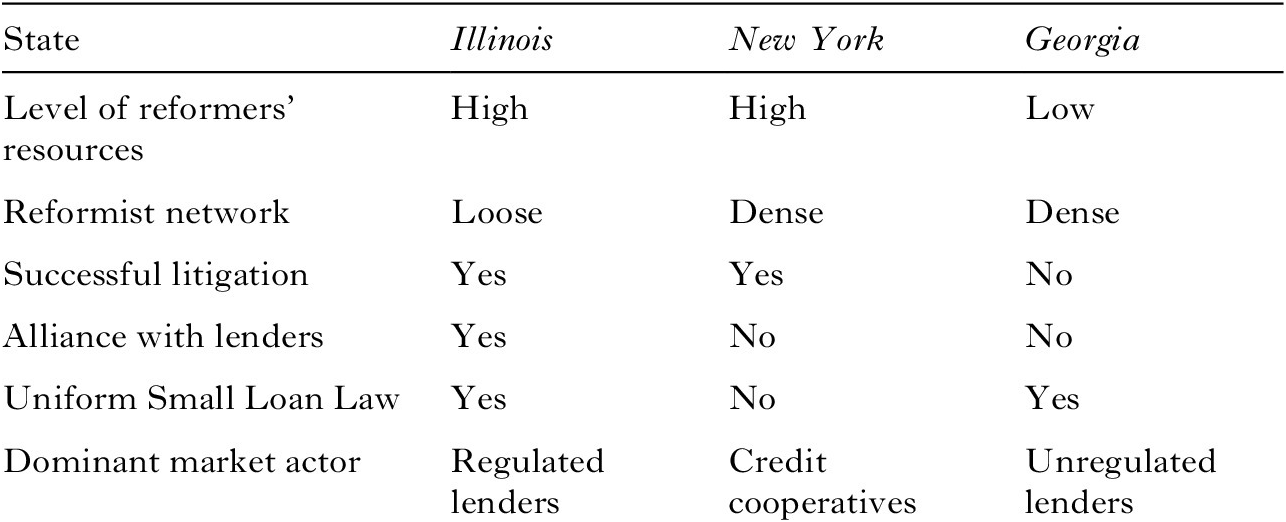

Salary loan activities mostly developed in urban and industrialized areas, as lending agencies primarily targeted stable wage-earners employed by large integrated companies [Easterly Reference Easterly2010; Carruthers, Guinnane and Lee Reference Carruthers Bruce, Guinnane and Lee2012; Bittmann Reference Bittmann2020a]. The expansion of wage-based (or unsecured) loans, hence required a sufficient growth and stabilization of industrial jobs for at least a segment of the workforce, but also a relative standardization of labor contracts and the related legal vocabulary [Laurie Reference Laurie1997; Njoya Reference Njoya2007]. The first part of our study builds on a comparative-historical approach focusing on the industrialized states of New York, Illinois and Georgia, a selection motivated by both quantitative and qualitative elements. New York and Illinois were two of the largest states, in terms of population and manufacture productionFootnote 5, and its main cities, New York City and Chicago, harbored some of the most active reformist networks during the Progressive era [Willrich Reference Willrich2003; O’Connor Reference O’Connor2007; Donovan Reference Donovan2010]. Similarly, Georgia was leading the industrial development of the New South: a major railroad hub, Atlanta spearheaded this growth and hosted an emerging reformist elite, albeit with fewer material resources [Shepard Reference Shepard2009; Amsterdam Reference Amsterdam2016]Footnote 6. Despite these similarities, as well as similar usury laws, these three states had diverging trajectories in the 1900s and 1910s: in Illinois, reformers worked hand in hand with lenders to draft the first state level regulation, later to be adopted nationwide, whereas in Georgia and New York, local elites fought against salary lenders, with unequal success. These initial configurations led states on distinct regulatory and market paths: Illinois and Georgia both adopted a credit reform, known as the Uniform Small Loan Law, in the late 1910s, and yet with drastically diverging effects. Whereas Illinois witnessed a large development in regulated loans, Georgia became the nation’s hub for unregulated “salary buyers” in the 1920s. By contrast, in New York, such a law was never passed, preventing the growth of a regulated loan market in the state.

The second section of this paper focuses strictly on Georgia, as this state became the central focus of reformists’ efforts during the 1920s: leaning on early judicial victories obtained in the early 1910s, the “Atlanta Big Four” built the largest network of unregulated agencies, extending throughout the country, and the conflict with reformers had major consequences for loan activities nationwide, as regulated lenders came to rely exclusively on chattel goods, and not wages, as collateral. In the third section, we analyse the conflict between bankers seeking to overhaul this regulatory framework and the established stakeholders, with Illinois lenders and New York reformers standing as their loudest opponents. Rather than seeking a uniformization of state laws, bankers and their trade associations supported a distinct national framework for wage bank loans, with a separate legal status, a unique pricing and distinct collateralization methods, further differentiating the credit market.

Data and Methods

Our data collection strategy was aimed at tracking the trials and controversies [Fourcade Reference Fourcade2011; Angeletti Reference Angeletti2017] regarding “salary advances”. To do so, we collected archives both from a major philanthropic organization, the Russell Sage FoundationFootnote 7 (hereafter RSF), which monitored and defended state level reforms throughout the country, and from local organizations, such as legal aid societies and chambers of commerce in Chicago, New York and Atlanta. Then, we amassed a set of local newspaper articles, commenting on legal cases and arguments as well as their repercussion in the public sphere. These materials enable us to identify key moments, where credit reform was a “hot cause” [Rao Reference Rao2008], prone to uncertain evolutions. We additionally collected a set of judiciary archives, tracking “salary advances” both in lower court proceedings and in reformers’ legal actions. We identified credit contracts in early judiciary records, as well as among lenders’ commercial papers, and followed the discussions of indeterminacies and compliance among credit activists, identifying relevant minutes and correspondence pertaining to the transaction’s legal status. Hence, we followed the unfolding of local scandals, revealed by legal aid lawyers or “crusading” newspapers, through cases brought to court and to judges’ final decisions as well as the rationales given. Finally, the description of the opposition between regulated lenders and commercial banks builds on material dedicated to various legal issues, located in the RSF archivesFootnote 8: these contain trade publications and discussions within professional associations—especially the Consumer Credit Division of the American Banking Association, created in 1939—as well as details about the opposition between supporters of distinct credit models.

Obscure Fees and Transparent Rates, 1900-1920

As Marx [(1867) Reference Marx, Moore and Aveling2015, Chapter XXIII: 401] pointed out early on, wages are an ongoing advanced contracted by the employer over the current month or week, only to be reimbursed at the end of the production cycle. Building a market for wage credit required a form of brokerage, where companies would temporarily liquidate the employer’s debt, through an advance given to the worker in exchange for a fraction of the amount lent. From the Colonial era until the early 20th century, state usury laws had remained the main legal status governing debt exchanges [Rockoff Reference Rockoff2003]; however, usury caps were primarily designed to control rural credit, guaranteeing that farmers could easily finance their seeds and tools before periodic harvests. The extension of small loans to urban dwellers raised legal uncertainties, largely exploited by agencies, who continuously argued that these were not credit transactions, but a form of salary “purchase” [Anderson Reference Anderson2008; Hyman Reference Hyman2012; Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane Reference Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane2015; Bittmann Reference Bittmann2020b].

This practice was hence described, by Progressive reformers, as a strategy designed to evade usury laws and expose workers to the risk of “financial servitude” [Bittmann Reference Bittmann2019], which could only be averted, according to the rallying elites, through establishing a “fair” rate, ensuring both a “reasonable profit” for lenders and moderate costs for borrowers.

Through “anti-loan shark crusades,” reformers sought exemptions to usury rates, for a specific class of small loans below $300, thus striving to eradicate unregulated lenders through competitive pressures [Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane Reference Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane2015; Bittmann Reference Bittmann2019]. The main policy tool was a fixed annual interest rate, which would replace various fees charged by salary lenders: as fees were paid on a weekly basis, they led to renewable loans, with reformers pointing to the accumulating charges over the course of weeks, months or years. In sharp contrast, an interest rate was supposed to curtail the practice of “doubling up”Footnote 9: borrowers would know the “true” and “transparent” price, through a fixed rate, and would contract a loan for a finite period, usually of one year. While this specific form of economic policymaking has been extensively studied, the legal operations as well as the frequent conflicts these transactions gave rise to have yet to be documented. Transforming the market through interest rates implied an extensive struggle aimed at convincing courts that these transactions were, indeed, a disguised form of credit to be subjected to usury rates.

While usury laws varied from state to state, both in terms of legal rates and ensuing penalties, during the 19th century these had slipped in the background of policymaking, with many states abandoning their status or subscribing to the general usury provision of the National Banking Act of 1863 [Rockoff Reference Rockoff2003]. The growth of salary lending therefore spurred a renewal of interest in usury ceilings as an efficient policy instrument, initiating a process of regulatory differentiation across various states, which we study through the comparison of New York, Illinois and Georgia.

In New York, We Have a Good Law

In New York, anti-usury campaigns were spearheaded by the Department of Remedial Loans (DRL) of the powerful Russell Sage Foundation. Founded in 1907 by Margaret Sage, the widow of the industrial tycoon, this organization devoted approximately $15 million to the “improvement of social and living conditions” in the country [Glenn, Brandt and Andrews Reference Glenn John, Brandt and Andrews1947: i.], investing in causes such as child hygiene, schooling or women’s working conditions. Dedicated to credit reform, the DRL had been vested with two core missions: defending “loan shark victims” through court actions, and promoting the growth of an alternative source of credit, in the form of semi-philanthropic lending associations, partly for-profit but guaranteeing a limited rate to poor borrowers [Easterly Reference Easterly2010, Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane Reference Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane2015; Fleming Reference Fleming2018b]. In doing so, the Department relied heavily on a close network of New York philanthropic elites, which historians have called “charity organizers” [Bacciochi et al. 2014], eager to mitigate the harmful consequences of industrial capitalism. These reformist circles included the largest network of charity organizations in the country, as well as burgeoning women and consumer groups [Bittmann Reference Bittmann2020b]. The first director of the DRL, Arthur Ham, cultivated strong ties with key institutional actors at the state level, such as banking authorities and the District Attorney.

The Department was rapidly successful in both endeavors. On the one hand, Ham incentivised debtors to initiate litigations against lenders, through the New York Legal Aid Society, offering to cover the ensuing expenses [Glenn, Brandt and Andrews Reference Glenn John, Brandt and Andrews1947: 140; Easterly Reference Easterly2010: 175-177]. Moreover, in 1913, the DRL managed to convince the district attorney of New York County to appoint a prosecutor in charge of usury cases: in his first five months in office, he obtained over one thousand victories in lower courts [Calder Reference Calder1999: 128]. The same year, Ham’s proselytist efforts led to the arrest of the main lender in the state, Daniel Tolman, who was sentenced to six months in prison and rapidly ceased to operateFootnote 10. On the other hand, the DRL actively promoted a specific type of credit union, known as a remedial loan association: Ham contributed to the federation of these organizations into a national union, acting as its unofficial chairman [Fleming Reference Fleming2018b: 37], and he convinced the president of the RSF to invest $100,000 in the creation of the Chattel Loan Society of New York [Glenn, Brandt and Andrews Reference Glenn John, Brandt and Andrews1947: 139], an organization established to provide an alternative source of credit to salary loans in the city, offering credit based on chattel goods. Between 1914 and 1918, close to one dozen credit cooperatives were created along a similar blueprint, and Ham directly worked with the State Banking Authority to lift several restrictions, facilitating their expansion [Easterly Reference Easterly2010: 193]. Between 1910 and 1925, 60-70% of their capital was detained by philanthropic organizations based in the state, a specific situation which led Ham to forgo the pursuit of any project of legislative reform, stating on multiple occasions that “in New York, we have a good law” [op. cit.: 189]. However, as Easterly [2010: 191-194] has shown, these organizations achieved only limited success, as many lasted only a few years or failed to balance their accounts, and the available funds never covered the growing needs of the local working class.

This unique configuration of reformist networks in New York, both in terms of campaigning power and investment capacity, led to a divided market, with unregulated salary buyers on the one hand and large semi-private credit associations on the other, funded by philanthropic capital and bent on supplanting the latter. Quite paradoxically, as the DRL became the most ardent supporter of credit reforms across state legislatures, in New York, compliance was not an option for salary lenders as no regulation was specifically set up to create a legal market.

From Litigation to Legal Reform in Illinois

Progressive reformers in Illinois were among the busiest in the country. From “anti-vice crusades,” seeking to regulate prostitution, alcohol, drugs and gambling, to campaigns against “white slavery,” associated with the forced prostitution of young white women, from the settlement houses movement led by Jane Addams to the reform of municipal courts, a wide array of business, religious, political, legal and scholarly elites was in constant effervescence [Willrich Reference Willrich2003; Donovan Reference Donovan2010; Keire Reference Keire2010; Batlan Reference Batlan2015]. Contrary to New York, this heterogeneous class of social reformers represented a loose and dispersed network, without any dominant figures or attempts at coordination. However, the frequent recourse of the reformist movement to courts and litigation produced a group of experienced legal professionals, frequently involved in the defense of multiple causes: among their most prominent figures were Harry Olson, Chief Justice of the Chicago Municipal Courts, District Judge and future Federal Judge Kenesaw M. Landis, prosecutor Clifford G. Roe and Daniel Trude, a young attorney later to be appointed as Circuit Court Judge. During the “anti-loan shark” campaigns carried out between 1912 and 1917, these worked hand in hand with the Chicago Legal Aid Society to defend usury “victims” and expose the illegal practices of salary lendersFootnote 11. Chicago’s most influential newspaper, The Chicago Tribune, also contributed to these efforts, setting up a “Legal Department” with the support of over 80 local lawyers, an initiative which led to the first successful prosecutions against lenders in 1912Footnote 12.

In 1916, the Department of Public Welfare of the city of Chicago coordinated and funded a large study, entitled The Loan Shark in Chicago, supervised by the sociologist E.E. EubankFootnote 13. Upon its publication, a large meeting was organized by the municipality, attended by representations of 44 local reformist organizations, among which the Chamber of Commerce, the State Bar Association, several large banks and social work or charity organizationsFootnote 14. However, several lenders also participated in the discussion, in particular Leslie Harbison, a senior manager for the largest network of salary loan agencies in the country, later to be incorporated as Household Finance. The presence of Harbison testified to a shift in the strategy pursued by Illinois lenders: the bad press, constant pressure of civil litigation as well as the fear of imprisonment, which followed Tolman’s arrest in New York, gradually convinced the company’s management that a collaboration with reformers would be in the best interests of their business [Bittmann Reference Bittmann2020b]. Anticipating an imminent legal reform, the company’s principal lawyer, Frank Hubachek, had drafted a bill proposal, in line with reformers’ core principles, which was submitted to, and finally endorsed by the various participants of the 1916 meeting. Simultaneously, Harbison and Hubachek also met with Arthur Ham and the DRL, seeking the endorsement of the RSF and its expert reputation: whereas Ham believed the DRL resourceful enough to oust salary lenders in New York, he was also convinced that allying with several enlightened lenders, willing to comply with regulation, would represent reformers’ best chance at implementing a credit reform at the national level (art. cit.). In the aftermath of the meeting, a Legislative Committee was formed and the drafted bill was defended at the following state legislature, leading to the passage of the first small loan law in 1917.

The intense legal battles waged against Illinois lenders resulted in a collaboration between a segment of dominant market actors, seeking to capture what was perceived as an inevitable regulation, and local as well as national reformers looking for a model victory which could lead to similar actions across the country. Contrary to New York, where regulation was achieved against lenders by a cohesive set of philanthropic elites, in Illinois, the interpretation according to which salary advances were, in effect, bona fide loans was supported by a diverse group of reformers, characterized by more distant ties and comparatively more legal resources. Such a configuration then led to a legislative reform that benefited from the support and investment of market actors.

Regulating Without the Courts: The Success of Georgia Lenders

Between 1903 and 1910, elites located in Atlanta, Macon, and Augusta organized “crusades” against salary lenders’ “nefarious business”Footnote 15. Contrary to New York and Illinois, these reformers primarily belonged to the business world, and their actions were coordinated by local Chambers of Commerce: in Atlanta, local entrepreneurs, bankers and employers carried the fight against usury as a way to improve the condition of the growing industrial working class, and simultaneously modernize the Southern economyFootnote 16. As early as 1903, the Atlanta Chamber issued a resolution, calling to “stamp out this evil” and “bring this matter to the attention of the Georgia Legislature”. These had, however, much fewer resources than their northern counterparts: local Chambers were plagued by limited funds, philanthropic organizations were still in their infancy and no legal aid societies existed in Southern states [Shepard Reference Shepard2009; Amsterdam Reference Amsterdam2016]. Moreover, direct civil action was deemed complicated because, in most cases, legal professionals could not reach borrowers until they faced a trial, and, even then, usury laws tended not to be applied as local Justices of the Peace routinely judged in favor of lendersFootnote 17.

The first collective action followed a scandal revealed in June 1910, when a railroad worker was imprisoned after his refusal to pay various fees imposed by five credit agenciesFootnote 18. The Atlanta Chamber issued a second resolution, calling out the press and seeking the support of two Solicitors General, who decided to release a text in the local press, inviting “loan shark victims” to report to their officesFootnote 19. In a few days, more than 20 borrowers were ready to testify and a grand jury prosecution was opened, with cases prepared and brought by the solicitors. The day of the hearing, 38 credit companies were summoned to submit their documents but only 5 complied: one of the lenders’ lawyers deemed the accusation “fictitious,” stating that “the law [was] on their side” and that the transactions on trial could not be assimilated with creditFootnote 20. A second hearing was then dedicated to “victims,” during which lenders pressured borrowers by sending collection agents outside of the courtroom, “taking notes and recording names of their victims who dared to tell their stories”Footnote 21. These actions emphasize the specific balance of power in this Southern state, in favour of lenders who actively fought legal actions, refusing both to back down or support, as in Illinois, the regulation of their activities.

The grand jury nevertheless issued 142 indictments against lenders, as well as bailiffs and one magistrate: these accusations did not have immediate effects but, as a journalist underscored, “the evidence in the cases mentioned will render it possible to make a fair and square test, both of the usury law and of the kind of transactions that the money lenders have been carrying on”Footnote 22. Such a test case was finally brought in front of a superior court jury in December 1911. It concerned one of the largest credit companies in the country, operated by the King Brothers of Atlanta. After several hours of deliberation, the jury found the lenders not guilty of usury, stating that state laws were “faulty” and that the defined usury rates did not apply to the transactionFootnote 23.This defeat temporarily halted the elites’ efforts to regulate the credit market, as lenders’ contractual devices prevailed. In the aftermath of the decision, the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce did try to organize a legal aid society and finance a local credit association, but both of these organizations were short-livedFootnote 24. Reformers concentrated most of their efforts on promoting a model small loan law to be presented at the state legislature, following the passage of the law in Illinois and in other states: they were more successful in this endeavour, as the RSF-endorsed credit reform was voted in 1920 in Georgia, despite the previous judiciary setback.

In Georgia, the lack of a proper framework combined with the limited economic and legal resources of local elites played in favor of fees over interest rates, legitimizing organizational practices over reformers’ interpretation. This made up for a distinct market configuration, as regulated small loans were provided a legal infrastructure, but without the support of the courts, a situation which allowed the rapid growth of unregulated lending during the 1920s.

In Table I, we summarize the results of the comparative-historical analysis which emphasizes the effect of regulatory differentiation on the structure of credit markets: the level of financial, reputational and legal resources available to reformers, as well as the configuration of expert networks, determined the issue of the power struggle with lenders at the state level. In New York, the density of the reformist network enabled local elites to directly finance and coordinate a non-market organizational alternative to salary lending, whereas in Illinois, the low level of coordination led to a response that was more judiciary than economic, with local actors choosing to include dominant market players in the regulatory design. Finally, in Georgia, while the battle waged to extend usury laws was lost, reformers were still able to push for a legal reform, setting up for a conflict regarding the implementation of the new law to non-compliant lenders.

Table I The influence of regulatory efforts on local market configurations, prior to 1920

Uniformizing Markets Through the Courts: Fighting Salary Buyers in Georgia

The promotion of the Uniform Small Loan Laws (USLL) across the country continued during the 1920s, with 22 states adopting a version of the model law prior to 1930 [Carruthers et al., Reference Carruthers Bruce, Guinnane and Lee2012]. This legislative success was mostly the result of the joint efforts of the DRL and a new association of small loan brokers, which remained under the strict control of the increasingly dominant Household Finance Corporation [Bittmann Reference Bittmann2020b]. After what was perceived as a successful campaign in New York, the DRL assumed a more coordinating role, endorsing laws and giving legal and financial support to local reformers who sought out their expertise. In this context, the situation of Georgia rapidly stood out as the main threat to the viability of regulated markets: the success of the “salary buyers”, in spite of a proper legal framework, emphasized the limits of a strictly political response—in the form of state laws—to rule circumvention. Put differently, Georgia became the main regulatory frontier because it precisely raised issues of implementation, interpretation and compliance with the new laws. In the early 1920s, the DRL missioned Household Finance’s Frank Hubachek, now the main legal counsel for regulated credit companies, to devise a legal strategy intended to curb the activities of non-compliant lenders, which were expanding across state lines. In his ensuing memorandum, Hubachek identified the main issue with the implementation of the law: “The question […] is very simple: is the transaction a loan or a sale? There is no other question or problem. […] The law in Georgia on the question whether wage assignments are bona fide sales or usurious loans is much confused”Footnote 25. In order to convince the courts of the “true” nature of wage assignments, the strategy suggested by Hubachek was to emphasize the existence of a “duty to repay” and the “intention of the parties of the transaction to create this duty”: according to him, “this obligation of repayment” was “the essential characteristic which distinguishes a loan from a sale”.

In doing so, the lenders’ counsel did not believe in the power of banking or trade state authorities. According to Hubachek, these did not have the capacity to impose such an enlarged interpretation, and the DRL needed to coordinate with regulated lenders as well as local reformers in order to obtain strategic court rulings: “a case must be brought, and so decided, before such a tribunal [superior court], as to compel them [supervisory agencies] to act. But it is submitted that the prosecution of the original test case should not be left to these officials under any circumstances”Footnote 26. Pedriana and Stryker [Reference Pedriana and Stryker2004] have demonstrated that, in cases of weak supervisory agencies, social movements can resort to court action in order to produce enforcement and the intended changes in organizational practices. In such a context, the struggle is often “waged in explicitly legal terms,” the law becoming a “master frame” through which activists seek to gather resources and design actions [Pedriana Reference Pedriana2006]. Between 1924 and 1931, the DRL and Georgia reformers pursued such a strategy, intended to curtail lenders’ power and impose “salary purchase” as a valid legal standard.

Compliance as Politics: From Interpretive to Judicial Conflicts

In March 1926, delegates from the DRL, along with Georgia reformers, met with two of the largest owners of credit agencies in the South, including one of the King Brothers, looking to convince them of the many benefits attached to the new frameworkFootnote 27. The attending lenders argued that some of the smaller loans, of amounts inferior to $50, would not be profitable at the USLL rate, of 42% annually. For this class of transactions, they suggested additional fees which would be authorized on top of the legal interest, according to a “sliding scale”: 50 cents for loans of $5, 70 cents for those between $5 and $8, and up to $2.50 for loans of $50. This was unacceptable for reformers, whose flagship instrument, a unique and fixed rate, was aimed at ensuring “transparency” for the borrower. Behind this debate lay an opposition between two credit models, based either on wages or private property. Reformers argued that salary buying was “a severe drain on the family budget” and considered that “there are many useless and improvident loans caused by the fact that a man has opportunity to get a loan on his salary”Footnote 28. This critique did not only target unregulated lenders but aimed at doing away with the practice of turning wages into capital as a whole. Indeed, whereas the USLL did not specify a required collateral, the RSF continuously stressed that it would be preferable to refuse any “unsecured loans” based on future earnings, and focus on workers who could mortgage valuable goods such as furniture, clothes, cars, etc. A study conducted on 10,000 small loans authorized throughout the country shows that, in 1922, only 164 (1.08%) were secured by wages [Robinson and Stearns Reference Robinson and Stearns1930: 141]: the new regulation not only affected the way credit prices were disclosed; it also associated workers’ credit not with labor income but with ownership. According to King, some of their agencies had tried to abandon salary lending, but they were able to retain only 3% of their customers in these casesFootnote 29. Hence, the refusal to comply, expressed by Georgia “salary buyers,” did not simply stem from an incentive to circumvent the law: under the legal opposition between fees and interest transpired a divergent understanding of how wage-earners should be allowed to build debt.

Following the shortcomings of the meeting, the DRL decided to push for legal action. The main concern was the unpredictability of common law courts: at the time, Justices of the Peace had been professionalized and replaced by municipal courts in most parts of the country, and even small credit claims could face trial by jury [Willrich Reference Willrich2003]. However, as the jurisprudence contained in the Hubachek memorandum showed, there was still much hesitation on the part of juries: in 1929, an Atlanta lawyer, J.L.R. Boyd explained that “in Georgia, salary buyers have provided for themselves a cloak of legality which Juries cannot (with unanimity) see through”Footnote 30. Consequently, reformers decided to bring cases to equity courts, where no juries sat. Equity trials dated back to British medieval law, and enabled citizens to appeal directly to the king, or to one of his representatives, for a certain class of cases where common law was deemed unfit [Kessler Reference Kessler2005]. Whereas common law represents a conservative, slowly evolving body of decisions, equity courts were perceived by some legal scholars as more flexible: in those, judges were not bound by precedent-based interpretation and ruled according to a subjective understanding of the parties’ actions. Unsurprisingly, equity procedures were strongly advocated by legal realists of the time: for instance, Roscoe PoundFootnote 31 supported their development, stating that they would enable the justice system to adapt more efficiently to the rapidly changing social conditions affecting American citizensFootnote 32.

These courts therefore represented a form of “kadi justice,” according to Weber’s characterization [(1922) Reference Weber1978: 975-976] in his work on the rationalization of law: for Weber, these sitting judges were misaligned with the spirit of “rational capitalism,” where the formal interpretation of texts tended to prevail. As courts became a central tool in economic policymaking during the Progressive Era, in the absence of direct federal intervention, equity found a strong echo among legal professionals seeking to regulate credit markets. In Georgia, Boyd defended this strategy in a legal aid bulletin: “It is believed, that when confronted with the facts, a judge—not a jury, whose morality is that of its weakest member—can suppress for the good of Society such loan companies as operating outside the law”Footnote 33. The disguise of interest as fees (and of loans as sales) was framed as an issue in economic knowledge and transparency: the new law was designed to uplift the credit market but, in order for it to achieve its regulatory purpose, judges needed to acknowledge that the interest rate, defined through the USLL, was the only “true” way to price loans.

In May 1926, the newly founded Atlanta Legal Aid Society (ALAS), along with the support of the DRL, filed 600 petitions with a county judge, who agreed to grant an equity judgementFootnote 34. In his defense of “poor wage earners,” Boyd stated that “salary buying” represented “one of the greatest menaces we have to the welfare of the poor,” and offered a simple solution in the enforcement of the law: “In order that poor persons may be offered legitimate means of borrowing money, Georgia together with 21 other states has adopted the law urged by the Russell Sage Foundation, under which money lenders may charge 3.5 percent interest a month. But that was not enough to satisfy the men now getting rich by buying salaries”Footnote 35. One “tragic” story was put forward during the audience, which was then publicized by various newspapers throughout the country: Burl Parrish, an “old-time darkey,” had paid $2 every week for three years, “without whittling down the principal. […] Uncle Burle needed money because his ‘chillun was hungry’, so he sold his salary. […] You may wonder why even an ignorant Negro would continue to pay week after week the way Uncle Burl did. The loan sharks told him that if he didn't keep paying they would tell his employer […] and he would be fired. Fear made him a financial slave”Footnote 36. The emphasis put on the assumed financial incompetence of the African-American borrower, and its obvious racist undertone, was meant to appeal to the moral compass of the Southern white judge. However, equally important was the reference to the USLL, with the lawyer stating: “the law regulates all interest charges, and the law should be enforced”. Local elites, such as employers, priests, lawyers or philanthropists, widely expressed their support of the “crusade,” and in June 1926 the judge issued 120 temporary injunctions against “salary buyers,” with lenders agreeing to annul any debt contracted by borrowers and cover judicial fees. In 1929 and 1931, Atlanta lawyers resorted to similar tactics, filing for injunctions within equity courts, an infrequent but successful way of obtaining legal recognition of the contractual framework championed by reformist movements.

The Reign of Interest: Interpretive Success in a Higher Court

In between these actions in the equity courts, credit activists closely analysed the decisions rendered by municipal courts, bringing multiple cases to trial where significant evidence tended to show the creation of an “obligation to repay”Footnote 37. The defence of borrowers followed a strict pattern, with arguments closely in line with reformers’ interpretation: “The outraged ‘wage earner’ plaintiff can usually recite to jurors many reasons why a ‘straight’ sale of his wages was an impossibility. He relates a set of facts showing an agreement both 1. To lend money 2. To deposit as ‘collateral’ security an absolute deed to wages”Footnote 38. Then, “the ‘salary buyer’ presented the usual ‘amendment’ alleging ‘fraud’,” an argument to which the lawyers replied by denouncing “the attempted use of the courts to accomplish ‘indirectly’, by a ‘tort’ suit what cannot be accomplished ‘directly’ by a ‘contract suit’”. Here, the lawyer tried to underline a contradiction in the lenders’ plea: lenders defended the legitimacy of their “wage assignment” transactions, and yet they did not seek compensation on the basis of a breach of contractFootnote 39.

Following this strategy, originally suggested by Household’s Frank Hubachek, Atlanta reformers managed to have two “wage assignment” cases reviewed by the Georgia Supreme Court, in February and April 1930. Both pertained to railroad workers who assigned their wages to “salary buyers,” and both were appealed by the ALAS following a superior court ruling in favor of the lenders, as in 1911. Yet in the late 1920s, the regulatory configuration was entirely different, as reformers had the support of a new credit law as well as additional resources stemming from the support of national reformers and regulated lenders. Consequently, the Supreme Court overturned the superior courts’ judgement in both cases, with judges insisting on the repetition of similar transactions at frequent intervals. In Jackson v. Bloodworth, the judge ruled that “the series of transactions” was “not a series of bona fide assignment of wages, but […] a loan by the assignee of the original sum of money advanced […] and the periodic payments made from time to time by the assignor to the assignee amount to interest paid by the assignor […] and, where the interest thus paid is usurious, the series of transactions constitute[d] a scheme for the evasion of the laws against usury”Footnote 40. The judge then underlined the existence of an “obligation” and a “debt” and hence the necessity, for lenders, to collect their money through a usual procedure of money “due and unpaid”. The language used closely followed the arguments put forward by reformers: the rulings insisted on the creation of a duty to repay and reaffirmed small loan laws as a relevant framework in assessing the transactions’ legality. These “loans” were therefore deemed usurious, even if the accumulated fees were not compounded in an explicit interest rate in either decision.

In the aftermath of the decisions, the ALAS obtained a growing number of favorable rulings in common law courts, where the Supreme Court’s reasoning was increasingly applied. Moreover, reformers used these decisions to pressure local employers into rejecting wage garnishments targeting their employeesFootnote 41. In seeking the transformation of credit practices, both the law and favorable decisions became strategic resources in order to influence courts, but also employers and non-compliant lenders. As a consequence, the two main Georgia chains converted to “regulated small loan lending” in the early 1930s, agreeing to comply with the USLL and its flagship rate, and in so doing stopped accepting wages as collateral. In the two firms’ first annual reports, balance sheets indeed show an exclusive use of chattel mortgages as credit assetsFootnote 42.

Following the initial differentiation of the states’ regulatory infrastructures as well as market configurations, during the 1920s, attempts at uniformization were carried by an “unlikely alliance” between regulated lenders and an increasingly coordinated network of credit experts [Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane Reference Anderson, Carruthers and Guinnane2015]. This was partially achieved both through national legislative campaigns and local judicial actions: salary loans were put to their most pivotal test in Georgia, as reformers sought to transform the decision-making process of lower civil courts, institutions which were perceived as the main gatekeepers of rule implementation in consumer finance. As Edelman et al. [Reference Edelman, Krieger, Eliason, Albiston and Mellema2011: 911-912] have pointed out: “It is the lower courts that are sociologically most interesting” as it “is in this locale that legal doctrine meets society most directly as lawyers and parties contest facts as well as law”. Relying on the new USLL as a “master frame,” but also on a quasi-sociological understanding of debt as obligation, Georgia reformers succeeded in building favorable jurisprudence through Supreme Court judgements. However, this process also had major consequences in terms of market structure, influencing the type of security regulated lenders were willing to accept. Hence, until the mid-1930s, small loans represented the first nationwide market for consumer credit, yet in a way that prevented American workers from directly using their wages as collateral.

Discount vs Interest: Is Banking Moneylending? 1934-1943

In the early 1930s, the main market divide separated regulated lenders, operating under the USLL, from unregulated lenders in non-USLL states or fighting against the USLLFootnote 43. In the absence of constructive federal regulations, state credit laws thus continued to represent the main regulatory reference point, defining a fixed monthly interest rate and chattel goods as legitimate collateral. However, in the late 1920s, commercial banks had started offering small loans to consumers, a type of credit which grew rapidly during the second part of the 1930s [Chapman Reference Chapman1940]. Up until this point, bank credit had remained strictly business-oriented: consumers could use deposit or saving services, but credit was only granted to business owners. In 1928, National City Bank opened the first Personal Loan Department in New York City, offering loans of up to $1,000 to steadily-employed workers [Hyman Reference Hyman2012: 87]. As the experience proved successful, other banks soon opened their doors to private consumers. The development of bank loans occurred primarily in states where no USLL had been voted [Plummer Reference Plummer1940]: New York soon became the leading state for bank loans, representing 29% of overall volumes in 1936, whereas the largest regulated lending states—Illinois, Ohio and Pennsylvania—accounted for just 7% of bank creditFootnote 44, a spatial distribution that emphasizes the effect of prior regulatory dynamics on credit markets. Moreover, in the years following the 1929 crisis, commercial banks were targeted for their responsibility in the financial meltdown [Huertas and Silverman Reference Huertas and Silverman1986], and these organizations were seeking new sources of legitimacy and revenues. Investing in consumer credit was seen as a way of promoting a form of “community logic” [Marquis and Lounsbury Reference Marquis and Lounsbury2007], where the focus was diverted away from profits and speculative investments, and towards financial services to “average citizens”. This impetus was reinforced by the Modernization Credit Plan of 1934, also known as Title I of the National Housing Act, which included, on top of the push for state-backed mortgage credit, a second provision devoted to small consumer loans of up to $2,000, to be issued by banksFootnote 45. Such loans grew rapidly during the second part of the decade, so much so that, by 1945, banks had become the primary providers of consumer credit, surpassing small loan lenders [Dauer Reference Dauer1944].

As these activities expanded, so did competition with regulated lenders. This opposition crystallized in a major controversy regarding price disclosure, which culminated in an open battle between 1939 and 1943. Whereas small loans were regulated by fixed USLL interest rates, banks traditionally relied on discount, withdrawing an amount in dollars from the original loan: rather than charging a monthly rate on a declining balance, expressed through a percentage, discounting implied a deduction of the cost right from the start, with customers usually paying $6 on a $100 loan (or a 6% discount). Bankers argued that this method more directly expressed the “true” price of credit, as a clear amount in dollars was initially charged. In contrast, regulated lenders and Progressive reformers criticized this approach as a new scheme intended to “deceive” the borrower: arguing that, mathematically, the corresponding interest rate on a 6% discount was around 11.7% for a one-year loanFootnote 46. More generally, promoting such a pricing method was, for bankers, a way to establish a distinct form of consumer credit, and this was perceived as a major challenge to the regulatory infrastructure strenuously built by Progressive reformers, and implemented through costly legal battles. As the American Banker Association (ABA) argued in 1940, discount and interest represented two distinct “philosophies of lending,” and nothing justified the need for banks to comply with the USLL frameworkFootnote 47. Commercial banks were not trying to supersede the existing state regulations, but to add a distinct, federal strand of legal coding, whereby these new loans would simply represent an extension of commercial credit to individual consumers.

As the indeterminacy raised by the discount method further differentiated the credit markets, Progressive reformers and regulated lenders pursued their attempts at uniformization, stating that banks should rally under the established USLL rulesFootnote 48. However, contrary to the opposition between reformers and unregulated lenders, this conflict over the right method for pricing credit was no longer waged through local campaigns and court battles. In the 1930s, consumer credit had become a federal, macroeconomic issue [Bittmann Reference Bittmann2019] and, therefore, the fight for market regulation shifted away from the local scale. Leaning on the sympathy of New Deal regulators, bankers succeeded both in keeping this controversy within the confines of expert administrative circles, and imposing a distinct method for coding workers’ debt at the federal level.

Coding at the Federal Level: The Rate Controversy of 1939-1943

In 1939, faced with the growth in bank consumer credit, Rolf Nugent, director of the former DRL, now renamed Consumer Credit Department at the RSF, asked for the intervention of the Federal Reserve Board in order to regulate loans made on discount, arguing that the “legal status of these transactions” remained “exceedingly hazy”Footnote 49. According to him, discount rates were reminiscent of unregulated salary loans: this practice, designed to “avoid interest rate restriction” was “not only unauthorized, but contrary to public policy as expressed in usury statutes”. His claim was backed by recent decisions of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), concerning automobile financing [Fleming Reference Fleming2018a]: several car manufacturers were aligning themselves with banking practices, charging a 6% discount, and the FTC had forced these creditors to abandon this method, which was deemed deceitful. However, in the case of bank loans, both the FTC and the Federal Reserve remained silent when solicited by the RSF. Progressive reformers had established their expertise over credit matters at the state level but, in contrast to banks, they had only distant ties with federal regulators. Similarly, dominant actors within the small loan field tried to warn banks of the risks associated with pricing credit by any other means than a fixed interest rate. Byrd Henderson, president of the Household Finance Corporation, advised banks to switch to the interest method, based on his personal experience with legal struggles: “credit to wage earners is a delicate and explosive thing. No one seems to care what a large corporation pays for its borrowed money. But let clerks or mechanics pay twice what they think they are paying and public opinion rises in disapproval”Footnote 50. Coding workers’ debt had raised many sensitive issues, which his company had managed to contain through legal cooperation with “public leaders” and “welfare organizations”. In his opinion, the discount method would always be perceived as dishonest, as the corresponding interest rate would always appear higher, a fact that was “true both mathematically and in contemplation of law”. Moreover, behind those apparent calculative conflicts, the reluctance of bankers to comply with the USLL stemmed from two critical issues.

First, switching to interest rates would entail organizational costs: as a Tennessee banker argued, it would “necessitate a complete change in forms, confusion, inconvenience and unnecessary expense,” such as “increased operating costs, additional capital investment in new equipment and calculators”Footnote 51. This was particularly true since the Title I legislation was modelled after banking practices: it authorized discounts as a pricing method and included predefined tables to facilitate banks’ adoption of the plan. When a personal loan department was opened, bank directors often used formulas and contracts they had established to benefit from this federal program. Additionally, discount rates were strongly tied to banks’ commercial credit services: according to the president of the Michigan Bankers Association, there was “no great difference in the credit which may be extended to a salaried man or to a business man, as both types of loans are based on the ability to repay a certain amount at a specific time. One relies on the future of his business, and the other on his future salary”Footnote 52. According to this logic, consumer loans were a mere extension of commercial credit, and borrowers should be offered the same conditions as entrepreneurs, in the form of discounts in dollars.

The second set of costs were reputational: interest rates were associated with a class of regulated lenders allowed to charge rates higher than usury laws, which, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, could stigmatize these new banking services. An editorial in American Banker voiced the opinion of many members of the profession at the time, stating that the interest method seemed “designed to force banks to choose between two horns of a resultant dilemma: 1) to become tarred with the stigma which is attached to the high money lender 2) to get out and stay out of the business of making small personal loans”Footnote 53. Bankers sought to resolve this professional conflict by asserting that banking and money-lending remain two distinct financial activities. In a paragraph entitled “Shoemaker, stick to your last,” a Wisconsin banker argued that “[b]ankers […] have sought a fair lending formula, which best fits in their accustomed manner of doing business and […] they studiously avoided telling other consumer credit lending agencies how to run their business”Footnote 54.

The various attempts at criticizing the discount method were not only hindered by the loose connections between USLL supporters and federal regulators, but more generally by the unwillingness of the federal administration to regulate bank consumer loans. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), through its administrator Stewart McDonald, continuously reaffirmed its intention not to interfere with commercial banks so as not to risk their participation in the recovery programs [Coppock Reference Coppock1940: 5; Trumbull Reference Trumbull2014: 31]. Regulatory opposition could, therefore, only come from state legislatures. However, among every states which addressed the rate issue during this period, all but one legislated in favor of the discount [Chapman Reference Chapman1940: 51-53]. Two main reasons explain these unanimous, state level decisions not to legislate against this method. First, most banks engaging in consumer credit were large and nationally chartered, and state governments remained reluctant to constrain these companies: any local regulation applying to both local and national banks would be attacked in a federal court as an encroachment on the separation of powers, whereas any law specifically targeting state banks would distort competition to the advantage of national banks. Second, the ABA progressively took a united stance in favor of discount over interest: when Walter French was appointed director of the newly created Consumer Credit Division in 1940, his first matter at hand was the rate controversy. In his correspondence with officers of the RSF, French confessed that he observed a “gradual crystallization of opinion among bankers” in favor of discount, which led him to defend this method with both federal and state authoritiesFootnote 55.

Thus, the success of banks in legitimizing their organizational choices illustrates a form of “legal endogeneity” unfolding at the federal level, and which neither regulated lenders nor credit reformers could forestall. As a result, in the mid-1940s, the USLL remained the relevant state level framework for consumer loans, but bank credit was ruled of a different nature, as these organizations were authorized to disclose prices with a distinct method. In turn, this evolution further contributed to regulatory differentiation, introducing a distinction between state and federal strands of legal coding.

Socializing Workers’ Debt: Co-Signers and Community Banking

The pricing method was the main, yet not the only divisive issue between credit agencies and commercial banks. The majority of bank loans did not rely on traditional collateral, either in the form of wage assignments or chattel mortgages; rather, they required the signature of two additional wage-earners, “steadily employed,” furnishing additional security in case of default. While asking for endorsers was a typical practice within commercial credit at the time, in the case of personal credit, banks relied on a patented credit model known as the Morris Plan. This type of institution had been created in 1910 by a Virginia banker, Arthur Morris, as an alternative to both regulated chattel loans and salary purchases: targeting the “propertyless man”Footnote 56, these structures offered loans from $10 to $10,000 to wage-earners who could obtain the support of two “co-signers”. These Morris Plan banks sought to be recognized as banking institutions with no deposit services, and their legitimacy was equally challenged from the 1910s onwards by “anti-usury” reformers, although to a much lesser degree than “salary buyers”. In 1940, 31 states had authorized this system but its network remained limited in scope, with a low overall volume of loans [Dauer Reference Dauer1944]. However, because of its particular model targeting wage-earners without the stigma of wage assignments, the Morris Plan served as a reference for pioneer bankers looking to invest in consumer credit: according to Walter French, “the success of the Morris Plan banks encouraged others to enter the field”Footnote 57 and, during the 1930s, many of these organizations were purchased by commercial banks, to be transformed into in-house loan departments.

For commercial banks, importing the “co-signers” system represented a way of reinforcing the community logic, at the heart of their involvement in consumer credit, all the while avoiding the stigma and judicial complications associated with garnishing wages. As an earlier promoter of the system wrote to an officer at the RSF: “The plan does not require a wage assignment from any of the signers, which eliminates a certain feeling of embarrassment from the better class of borrowers”Footnote 58. Moving away from “poor” workers’ credit hence required a distinct contractual device: when additional wage-earners were involved in the plan, bankers argued, personal debt became embedded in the borrower’s interpersonal network, pledging not his property, but his “community”. However romanticized this method could appear, it emphasized the way commercial banks tried to position themselves within the legal and organizational landscape of the time: even if banks were, in fine, relying on their borrowers’ labor income to ensure repayment, they shifted the focus away from wages as security, and towards wage-earners as social individuals, evolving within a community of indebted workers.

Whereas the fight against “financial enslavement” had frequently denounced the dispossession of workers who pledged their wages to lenders, this method was intended to shield banks for remnant Progressive controversies. This differentation was particularly visible in the way an Iowa banker defended the direct withdrawal of wages from workers’ paychecks as an expeditious convenience. In 1940, the director of a bank based in Des Moines established partnerships between his organization and several local employers: when a worker applied for a loan, bank employees would get in touch with the employer’s accountant, so that repayments could be directly withdrawn from the worker’s pending wagesFootnote 59. Each “employee-borrower,” as the director put it, was offered a savings account to which his revenue was transferred on payday, and from which the bank would collect payments. The banker defended the efficiency and simplicity of the plan, with no harassment involved of either party: because the savings account remained active even after the loan had been paid in full, he argued that many borrowers would “become savers instead”. This collection method, although similar to that which had triggered legal battles up until the 1930s, did not raise any controversy, demonstrating that the propensity of regulatory indeterminacies to remain within expert or professional networks, or turn into an open conflict, depends on the screening capacity of market actors.

Summary of Results and Conclusion

Our main results concern the effects of regulatory differentiation on market structure, summarized in Figure 1. We identified three distinct periods of interpretive conflicts regarding salary loans and followed their impact on the coding of workers’ wages, through three outcomes: legal status, pricing metrics and collateralization. During the first two decades of the 20th century, fees were at the heart of unregulated lenders’ credit model: contractual schemes were intended to facilitate frequent renewals and wage garnishments within lower courts, all the while circumventing traditional usury laws. Regulatory efforts were initially carried by local groups of Progressive reformers, both waging legal battles and organizing reform campaigns within state legislatures. These endeavors led states on diverging regulatory paths, depending on the success of legislative efforts—in the form of a uniform credit law—and local judicial battles, and incidentally to a first major split in the market, between compliant chattel lenders and non-compliant “salary buyers” (see Table I). Then, through the promotion of a fixed interest rate, Progressive reformers sought to homogenize credit markets and limit the capacity of unregulated credit agencies to evade the new laws. In their major fight against Georgia lenders during the 1920s, reformers benefited from the support of regulated credit companies, an alliance which resulted in favourable court decisions, but simultaneously expanded a credit model built not on wages, but on personal property.

Figure I Regulatory differentiation on the market for unsecured loans, 1900–1945

Key: Dashed arrows designate policy efforts, whereas solid arrows indicate an organizational change. This graph does not account for across-state differentiation, and should be read jointly with Table I. USLL stands for Uniform Small Loan Laws.

Finally, the use of discount rates by banks aimed at establishing a separate banking jurisdiction over unsecured lending, and the adoption of a co-signer model was intended to shift the focus away from the controversial coding of workers’ wages. Commercial banks were successful in superimposing a distinct consumer credit regulation at the federal level, thanks to their strong professional unity (at least for national banks) and the support of the New Deal administration. In contrast, despite their expertise over credit matters, the low “structural embeddedness” of Progressive reformers within federal “interpretive communities” resulted in an unsuccessful attempt at raising a discussion over discount rates [Thiemann and Lepoutre Reference Thiemann and Lepoutre2017], a failure which led to a second market divide, between banks and regulated lenders. This coexistence of two distinct legal regimes, along with state level differences and the persistence of unregulated salary lenders, continued until the passage of the Truth in Lending Act of 1968, which represented the first attempt to impose a single metric on all consumer credit providers, in the form of annual percentage rates [Fleming Reference Fleming2018a]. While the imposition of a universal instrument represented a new step towards the construction of a national credit market, the idea that political intervention should prioritize the supervision of the pricing method, through a strict legal framework, directly followed the conflicts that unfolded during the first half of the century. Moreover, this evolution did not resolve the existing differentiation between market tiers, which endured and continues to stratify unsecured consumer finance until today.

Through this paper, we hoped to provide a crossing point between critical financial studies, which have underlined the central role of capitalization devices in techno-scientific capitalism [Muniesa et al. Reference Muniesa, Doganova, Ortiz, Pina-Stranger, Paterson, Bourgoin, Ehrenstein, Juven, Pontille, Sarac-Lesavre and Yon2017; Birch and Muniesa Reference Birch and Muniesa2020], and a legal theory of capital modulation [Black Reference Black2013; Pistor Reference Pistor2019]. Far from abstract ordinal metrics designed to classify risk, such as postulated by microeconomic theory, prices and their supporting formulas represent central regulatory devices governing financial practices. More precisely, in the market for unsecured loans, discussions about the meaning of compliance revolved around calculative technologies, which, in turn, provided the infrastructure for coding workers’ wages in distinct fashions. Building on existing literature which has identified two major mechanisms driving regulatory compliance, namely “legal endogeneity” and “interpretive communities” [Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Krieger, Eliason, Albiston and Mellema2011; Thiemann and Lepoutre Reference Thiemann and Lepoutre2017], we showed how these played out in the context of consumer credit regulation. The longitudinal approach to power struggles and alliances between reformers and lenders shed light on two competing historical dynamics—differentiation and uniformization—which help us understand the two main divides in the market for unsecured loans: between unregulated salary lenders and regulated small loan brokers, as well as between banks and non-bank credit companies. As Aspers, Bengtsson and Dobeson [Reference Aspers, Bengtsson and Dobeson2020: 425] recently put it, “regulation is a form of fashioning of markets”: In expanding the analysis of compliance to address more classical issues in economic sociology, such as market structure and field-level organizational dynamics, this article thus invites further research to explore the complex interplay of legal, political and relational factors in shaping the historical evolution of financial markets.

Appendix

Lending was far from a new phenomenon for American workers, yet the growing urbanization and industrialization of the late 19th and early 20th century modified the ecology of consumer credit: typical creditors dating back to the Colonial era included pawnshops, small peddlers or retail merchants, and these coexisted with more contemporary forms, such as instalment buying, offered by a variety of small and large companies, and department store credit. Unsecured loans stood at a comparative advantage with all of the former, in that it required neither the physical dispossession of personal property, such as in the case of pawnshops (chattel lenders did not require that pledged goods should be kept in their offices), nor did it jeopardize personal or community ties, as was often the case with local merchants or peddlers.

Five major credit providers offered various types of wage-based loans until 1945: regulated small loan lenders and unregulated salary buyers—the main focus of our study—and, after 1930, commercial banks, as well as credit unions and Morris Plan banks. The two last types of companies were less dominant, in terms of loan volumes, and we decided to exclude them from our study (despite occasional references) because of their specific organizational models. Credit unions were very diverse, from local trade cooperatives to large lenders, such as the Provident Loan Society, to more organized nationwide bodies, such as the National Federal of Remedial Loan Associations, promoted by the DRL: limited in both scope and funds, they offered minimal rates but little flexibility to debtors, and were highly dependent on the availability of local philanthropic capital [see Fleming Reference Fleming2018b: 31-36]. Patented Morris Plan banks also drew upon the cooperative model––which according to its founder, Arthur Morris, inspired the co-signer model––but were entirely for-profit. These companies strove, with little success except in two states (Ohio and Iowa), to be recognized as a new form of banking, and never sought to compete with other small loan lenders: they targeted primarily white collar or middle-class borrowers and offered, on average, much higher loans, of around $250 to $300. By comparison, salary lenders issued loans ranging mostly from 25 cents to $50, and regulated small loans were rarely above $100 [Robinson and Stearns Reference Robinson and Stearns1930]. At their peak, in 1940, there were only 94 Morris Plan banks in the country, most of them being gradually acquired by national banks.