Introduction

The liberation of East Central Europe by the Red Army at the end of the Second World War ushered in a multi-layered process of unification of this region into a socialist community led by the Soviet Union. The transformation of the cultural landscape was part of this violent project. Its main markers represented monuments devoted to the Red Army and the friendship with the Soviet Union as well as street names commemorating local, national and international heroes of the Bolshevik revolution and the communist cause. When state socialism collapsed between 1989 and 1991, the de-communization of East Central Europe began.

A closer look at how the cultural landscape in Poland has been cleared of the material legacies of communism between 1989 and 2019 reveals various types of agency operating behind this process. By studying political discourses, legal regulations and social practices aiming to rename streets and remove monuments associated with communism from Poland’s public sphere, this article identifies three stages of the purification process. The early 1990s were shaped by spontaneous and locally driven attempts at removing the most visible markers of communism. This outburst of popular iconoclasm was followed by 20 years of uncertainty about how to proceed with the remnants of the communist past. Since 2015, a new type of anti-communist fervour can be observed. In contrast to the early 1990s, the recent attempts at de-communizing Poland’s public space have been initiated not from below, but from above. In other words, during the last 30 years, Poland’s de-communization project has undergone a major transformation: from a popular need expressed in a variety of decentred initiatives to a political programme revolving around one centrally organized idea.

And yet the material legacies of communism are still present in Poland’s public realm. Their persistence not only illustrates the ambivalent attitudes of Poles towards the recent past of their country, but it also reveals both the mobilizing potential as well as the limits of anti-communism. Additionally, it demonstrates how difficult it is to provide for a legally binding and practically effective definition of communism, and it exemplifies a broader struggle over the question of who should play which role in shaping Poland’s cultural landscape.

Popular Iconoclasm of the Early 1990s

In 1989, Poland’s public space was saturated with the legacies of communism, the Polish–Soviet friendship, brotherhood in arms and the joint victory over fascism. As in other countries of East Central Europe, the transformation of state socialism into liberal democracy went hand in hand with the removal of the material traces of Poland’s dependency on the Soviet Union (Gamboni Reference Gamboni1997: 51–90). A key role in this process was played by the (newly created or re-empowered) self-governing units: due to administrative and territorial reforms introduced in the 1990s, the control over Poland’s cultural landscape has been largely seceded to local authorities.

Some of the most disturbing symbols of the recent past quickly disappeared from Poland’s public realm. By July 1989, the statue of the communist leader Bolesław Bierut (1892–1956) was toppled in his hometown of Lublin. In November of the same year, the statue of Feliks Dzerzhinsky (1877–1926), one of the main architects of the Red Terror, was removed from Warsaw. A few weeks later, the statue of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) himself disappeared from Nowa Huta. Whereas the monument representing Bierut ended up in a small museum in south-eastern Poland, that of Dzerzhinsky fell apart while being lifted by a crane, and that of Lenin was sold to a Scandinavian business to be exhibited in a sculpture park. Other material remains of Poland’s communist past could also be easily recoded and reused for new purposes. For example, in 1990, the Lenin Museum in Warsaw was quickly transformed into a Museum of Independence, and the former headquarters of the Polish United Workers’ Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) became the seat of the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

These remarkable acts of removal and reusage of the material legacies of communism were paralleled by apparently less spectacular, but actually even more momentous interventions in Poland’s cultural landscape. It is estimated that, by 1993, around 30% of street and square names were changed across the country (Hałas Reference Hałas and Marody2014). The financial and organizational consequences of these changes for individual citizens, institutions and communities proved to be so overwhelming that later attempts at changing the names of streets and squares associated with the legacies of the People’s Poland that had survived the early 1990s often triggered popular protest and contempt.

Beyond spectacular and widely publicized instances of removing and reusing the material traces of communism on the one hand and rather silent changes of street and square names on the other, the early 1990s saw a variety of local strategies of coping with the so-called Red Army monuments. Rarely created by known (or renowned) artists and rarely challenging the language of monumental realism, most of them represented impressive figures of soldiers, grand obelisks, and tanks. Usually located in central squares, on major roundabouts or in front of town halls, they were supposed to express Poland’s gratitude for the liberation, honour the brotherhood between the Red Army and the Polish Army on the Eastern Front and to commemorate the fallen soldiers or individual Soviet heroes.

By setting in stone an ideologically driven interpretation of the history of the Second World War in East Central Europe, Red Army monuments were in fact vehicles to enforce political and symbolic hegemony of the Soviet Union in this region. The view on wartime developments that was officially accepted in the People’s Poland silenced the memory of several events, including the Soviet invasion of Poland in mid-September 1939, Soviet deportations of Polish citizens in 1940 and 1941, the Katyn massacre in 1940 in which the NKVD (the Soviet secret police agency) killed up to 22,000 Polish military officers and intelligentsia, the Soviet unwillingness to support the Warsaw insurgents in the summer of 1944 and acts of physical violence against Polish civilians that accompanied the liberation of East Central Europe in late 1944 and early 1945.

In popular imagination, the memory of these events mingled with a much longer history of Russian influence in Poland, including Russia’s participation in the partitions of Poland in the late eighteenth century, which annihilated Polish statehood for the next 123 years, the Polish–Soviet war in 1919–1920 and the Red Terror of the 1930s. It is therefore little wonder that prior to 1989, Red Army monuments were not only places where party, state and military functionaries used to lay wreaths and hold speeches during remembrance days, but were also objects of silent disapproval, ironical distancing, deflationary nicknames and violent attacks (Czarnecka Reference Czarnecka2015: 135–177).

Between 1989 and 1993, up to one third of the 476 Red Army monuments existing in Poland were relocated to military cemeteries or ended up in municipal storage houses, and many of them were later transferred to the Gallery of Socialist Realist Art that was established in 1994 in Kozłówka or to the Museum of the People’s Poland that was founded in 2010 in Ruda Śląska (Czarnecka Reference Czarnecka2015: 336–338). Usually, the initiative to remove the Red Army monuments came from politicians and activists defining their identity in strongly anti-communist, anti-socialist, anti-Soviet and anti-Russian terms. In most cases, the disappearance of Red Army monuments went unnoticed. Sometimes, however, it turned into a political happening. For example, in mid-1990, local activists from Gdynia in northern Poland framed the removal of the Red Army monument in their city as the ultimate symbol of regaining freedom and independence. When pulling down the inscription ‘Eternal Honour and Glory to the Heroic Soldiers of the Red Army,’ they celebrated the event with a glass of champagne. A couple of weeks later, a group of inhabitants of Białystok in eastern Poland expressed delight at the removal of the local Red Army monument by destroying the plinth and putting there a banner with the slogan “Here stood a monument of shame” (Czarnecka Reference Czarnecka2015: 340–341). These playful rather than violent events provided (mostly) young Poles with the opportunity to express their negative feelings towards both the recent past of their country and Poland’s eastern neighbour.

The moderate acts of popular iconoclasm of the early 1990s might be explained by three limiting factors. One of them was the continuous presence of the Soviet/Russian army on Polish territory. In the early 1990s, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Poland seemed unlikely even to the most optimistic observers. Until it really happened in 1993, there was a broad consensus in Polish politics that it is better not to raise unnecessary conflicts with (the main successor of) the Soviet Union because Poland’s Western aspirations, including NATO- and EU-membership, largely depended on its good relations with its eastern neighbour. Of equal importance, however, was Poland’s energy security: as long as it depended on Russian oil and gas deliveries, conflicts with Moscow had to be avoided. Eventually, an important limiting factor was the lack of a Polish–Russian agreement that would regulate the status of the Red Army monuments in Poland. The legal grey zone ceased to exist in 1994 when a bilateral agreement was signed (Agreement of 22 February 1994). However, the devil was in the detail.

As it turned out, the Polish–Russian agreement contained two bones of contention. One of them resulted from the lack of coherence between the official name of the document and its content, the other from diverging interpretations of the content itself. According to its first article, the agreement ‘on the graves and memorials of victims of wars and repression’ relates to ‘places of memory and last rest’ – both Russian in Poland and Polish in Russia. In the name, as well as in the content of the agreement, its Russian and Polish rendering uses the same ambiguous phrase (mecmo naмяmu in Russian, and miejsce pamięci in Polish) which can mean both a physically understood ‘site of memory’ and a symbolically understood ‘place of memory’. As will be shown, whereas the Polish authorities focus on the content of the first article and interpret the phrase ‘places of memory and last rest’ as relating to cemeteries only, the Russian authorities focus on the conjunction ‘and’ in the name of the agreement, insisting that it would protect ‘places of memory’ and ‘places of last rest’, i.e. not only cemeteries, but also monuments. The other bone of contention is the ‘list of known places of memory and last rest’ referred to in the second article of the arrangement, which both sides agreed to prepare. Whereas the Russian authorities maintain that a corresponding list for the Polish territory exists, the Polish authorities claim the opposite. In the years to follow, the Polish–Russian disagreements around the scope of their bilateral agreement triggered a number of controversies around several Polish monuments commemorating the Soviet soldiers.

Twenty Years of Uncertainty

Against the expectations of the most eager anti-communist activists, the withdrawal of the Russian troops from Polish territory in 1993 did not open a new phase of purification of Poland’s cultural landscape from the material remains of communism. After the initial renaming of streets and the fervent dismantling of monuments, the acts of recoding the public realm became sporadic. Yet the issue of de-communization did not disappear from public discourse. Between the mid-1990s and mid-2010s, the main dilemma revolved around the question of who should mastermind and manage the de-communization process and, more generally, around the role of the state in the construction of collective memory.

The suspension of the de-communization process after 1993 cannot be understood without considering the spectacular career made by the main successor of the communist party, i.e. the Social Democracy of Poland (Socjaldemokracja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, SdRP). Whereas in the semi-free elections of June 1989 the PZPR lost all the seats in parliament it could, in 1993 its successor won the elections with 20% of the vote and, after four years in opposition – meanwhile transformed into the Democratic Left Alliance (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD) – won again by obtaining over 41% of the vote in 2001.

The most widespread explanation of the electoral success of the post-communist party in Poland is that the so-called losers in the transformation process from socialist to market economy turned away from those representing the neoliberal order and returned to the political force associated with the stability of the pre-1989 period. No less important however, was the ability of the post-communist left to transform itself by adapting to the new situation and exploiting the weakness of its political competitors (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2002), and the fact that the collapse of state socialism in Poland was not identical to a complete disappearance of left-wing sympathies among Polish voters.

Considering that the macro-political change and the micro-political continuities brought about between the mid-1990s and early 2000s, the issue of de-communizing street and square names virtually disappeared from the public eye and the remaining Red Army monuments were more often re-coded and re-used than removed. Some communities opted for more pragmatic, others for more creative approaches. For example, in 1993, the monument devoted to Red Army soldiers in the town of Włocławek in central Poland was transformed into the Monument of the Polish Soldier. In 1997, by replacing the red star with a white eagle, the authorities of Puszczykowo, a small town in western Poland, altered the Red Army monument into a monument devoted ‘To all those who sacrificed their lives for the country’. In 2000, the Red Army monument in the Pomeranian town of Darłowo was refashioned into a monument commemorating ‘A thousand years of Poland’s return to the old Slavic lands’ (thus replicating one of the main tenets of the memory politics pursued in the People’s Poland with regard to the German lands that became part of Polish territory in 1945) (Czarnecka Reference Czarnecka2015: 347). In other places, the local authorities showed even greater creativity. For example, in 1996, the authorities of the town of Kłodzko in south-western Poland granted a lease on their Red Army monument to an insurance company that transformed the statue into an advertisement. Around the same time, in Kęszyca Leśna in western Poland, the Red Army monument was cleared of Soviet emblems and complemented with a plaque recalling the most important events in the history of the village. Moreover, in June of each year, when the Catholic villagers hold a procession to celebrate Corpus Christi, the re-coded monument becomes part of an altar (Czarnecka Reference Czarnecka2015: 348).

At the same time, many communities were reluctant to make the final decision about how to proceed with their Red Army monument, assuming that human remains might lie beneath. The decision to remove such an object would not only mean a good deal of additional work, but also the risk of losing control over the site because it would need to be re-classified as a war grave and the responsibility for it would be automatically transferred to the respective voivode, i.e. the official representative of the government at the regional level.

The unwillingness of the local authorities to complete the de-communization of public space triggered serious criticism from right-wing politicians and opinion makers who considered the removal of the Red Army monuments necessary for the moral regeneration of Polish society. The unfinished de-communization, they argued, would devastate Poland’s collective identity by promoting historical amnesia and undermining the popular sense of justice.

Due to external and internal pressures, the general interest in the material remains of communism increased in Poland around the mid-2000s. Externally, two events sparked a new wave of activities targeted mainly at the Red Army monuments. One was the spectacular commemoration of the end of the Second World War in Moscow in 2005. Attended by around 50 heads of state, including the US president George Bush, the commemoration was used by Vladimir Putin to advance his vision of Russia’s national identity as based on the pride of Soviet and Russian military achievements and the rehabilitation of the country’s imperial past (Weiss-Wendt Reference Weiss-Wendt2021). The other event was the relocation of the Bronze Soldier monument from the centre of Tallin to a military cemetery in 2007, which triggered mass protests and riots among the Russian community in Estonia, caused the death of one rioter and provoked a serious Russian–Estonian conflict (Brüggemann and Kasekamp Reference Brüggemann and Kasekamp2008). In reaction to these developments, a number of Polish NGOs publicly demanded the immediate removal of the remaining Red Army monuments from Poland’s cultural landscape.

Internally, 2005 saw the victory of the Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) in the parliamentary and presidential elections. However short, the PiS time in office brought anti-communism back to the mainstream of Polish politics (Ostolski Reference Ostolski2020). Between 2005 and 2007, the anti-communist energy of the ruling party was translated into two pieces of legislation that were supposed to complete the de-communization process (Bill of 13 December 2007a; Bill of 13 December 2007b). In order to accelerate the de-communization process, both bills aimed at strengthening state authority over Poland’s cultural landscape by transferring the responsibility for monuments and other sites of memory from local authorities to the voivodes. Unsurprisingly, both bills quickly became the subjects of withering criticism. The political opponents of PiS, many public intellectuals and moderate historians criticized the return to centralism. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the head of the Russian Orthodox Church condemned the idea of a wholesale removal of the remnants of the communist past (Ochman Reference Ochman2013: 75–89). However, since the bills were submitted shortly before the early election in 2007, they were not even debated in parliament.

The new government formed in 2007 by the main opponent of PiS, i.e. the central-right Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO), did not pursue the radical de-communization project advanced by its predecessor. In the following years, the main driving force behind the idea of removing the material remnants of communism from Poland’s public space became the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN). Established in the late 1990s in order to pursue archival, investigative, research, and educational work related to wartime and post-war history, the IPN quickly became the most powerful broker of public history in Poland. Between 2007 and 2010, the IPN requested that local authorities of 138 Polish towns and cities change street and square names allegedly glorifying communism. A refusal would be treated as a decision to preserve the main tenets of the political propaganda promoted in the People’s Poland, disregard the memory of victims of totalitarian crimes, disrespect those who had fought for Poland’s freedom, glorify Stalinism and pay reverence to the criminal ideology of communism (Korkuć Reference Korkuć2010). To boost these arguments, the IPN referred to Article 13 of the Polish Constitution and Article 256 of the Penal Code (Constitution 1997; Penal Code 1997). Considering that these legal arrangements barely include relevant stipulations, one might assume that the IPN was betting on the local authorities’ lack of legal expertise.

Despite ethical, historical and legal arguments, the strategy pursued by the IPN backfired. Fewer than 30% of the local authorities responded at all. Out of 37 responses, only six were positive and 21 were negative. The authorities of ten communities announced public consultations and, if such consultations took place, their participants rejected the IPN request. In some cases however, the local authorities advanced more ingenious approaches. The example of ‘22 July Street’ is telling. Some communities argued that this name would not refer to the main national holiday celebrated in the People’s Poland, which commemorated the signing of the July Manifesto in 1944, and which is officially considered to mark the birth of the new regime, but to other events. Whereas the authorities of the small village of Abramów in south-eastern Poland argued that their ‘22 July Street’ would commemorate the day in 1807 when Napoleon proclaimed the Duchy of Warsaw, the inhabitants of Konotop in western Poland maintained that the ‘22 July Street’ in their village would refer to the day in 1977 when the first inhabitants of a newly built settlement moved in to this street (Ochman Reference Ochman2013: 92). As the activities pursued by the IPN had no legal force, the vernacular cultures of remembrance could persist for years to come.

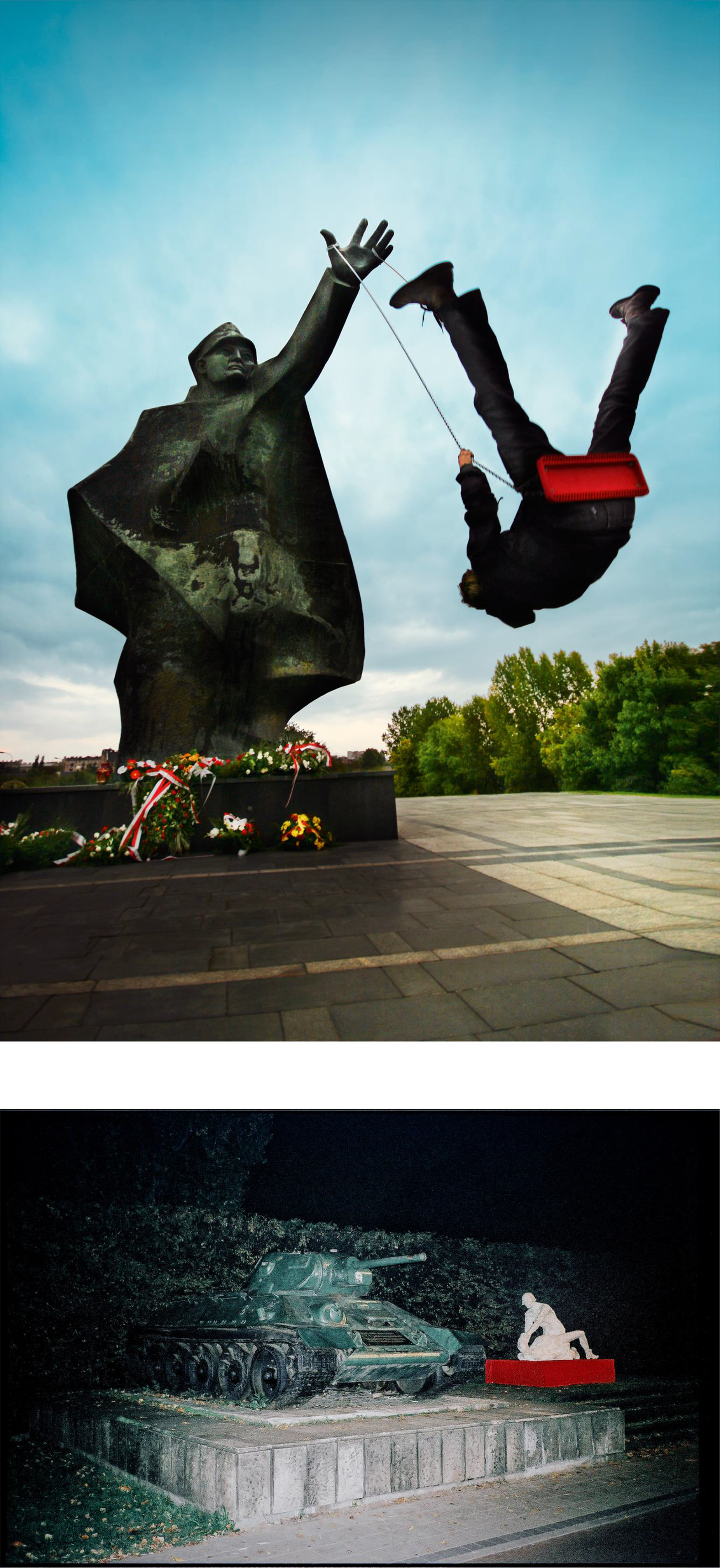

The overall failure of the persuasion campaign launched by the IPN in 2007 along with the tragic death of its head Janusz Kurtyka in a plane crash near Smolensk, Russia, in 2010, might explain why no similar programme was established with regard to the Red Army monuments. At the same time, the plane crash itself, in which 96 prominent figures of Polish political and public life died – including President Lech Kaczyński – had an impact on the attitudes of Poles towards the Red Army monuments. In the aftermath of the catastrophe, the country was flooded with conspiracy theories revolving around the role that Russia allegedly played in the accident. Its media landscape saw an unprecedented growth of (extreme) right-wing press, radio and television, and anti-communist activists called again for completing the unfinished de-communization of Poland’s public realm. In 2010 and after, some Red Army monuments became the objects of attacks and aggression (Czarnecka Reference Czarnecka2015: 344). It is safe to assume however, that for the majority of the Polish population the Red Army monuments were nothing more than a ‘conspicuously inconspicuous’ part of their environment (Musil Reference Musil and Wortsman2006: 64). Rare exceptions in the quiet lives of the Red Army monuments in Poland around 2010 were artistic interventions both scandalizing and normalizing the role of Soviet soldiers in Poland’s post-war history (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Top. ‘Carousel Slide Swinging’. In September 2008 Kamila Szejnoch (b. 1978) transformed the monument devoted to Berling Army Soldiers in Warsaw into a huge toy. By highlighting the contrast between the bronze monument and the tiny individual swung by the hand of History, her illegal art installation was supposed to draw public attention to the complexity of the past. Picture: Kamila Szejnoch (courtesy of the artist). Bottom. ‘Komm Frau’. In October 2013, Jerzy Bohdan Szumczyk (b. 1987) unsettled the public space in Gdansk by placing a statue of a Soviet soldier raping a pregnant woman next to a Red Army monument in the Victoria Street. The aim of his illegal intervention was to pay tribute to the victims of sexual violence committed by Soviet soldiers in East Central Europe in 1944/1945. Picture: Michał Szlaga (courtesy of the author)

Anti-Communist Fervour since 2015

The de-communization process was reborn in 2015 after the second victory of PiS in both the presidential and parliamentary elections. The party leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, learned a lesson from the defeat in 2007. As explained in an interview given while in opposition, Kaczyński’s priority became the idea of what he called ‘national integration’: ‘There is a rule first advanced, I think, by Konrad Adenauer that for a right-wing party which wants to be in power, there must be only a wall to its right’ (Kaczyński Reference Kaczyński2008). Beyond fervent nationalism, ultra-Catholicism and obsessive familialism, strong anti-communism has become part and parcel of his party’s identity (Korycki Reference Korycki2017).

According to the interpretation of Poland’s recent history promoted by the elites and allies of PiS, the negotiated nature of Poland’s post-1989 settlement precluded a full de-communization of the country. One of the many initiatives undertaken by the new parliament to eliminate the lingering communist impact on Poland’s political and cultural life was a law prohibiting ‘the propagation of communism or other totalitarian systems’ passed in April 2016 (Act of 1 April 2016). According to this legal act, ‘[n]ames of buildings, objects, and devices of public use, including roads, streets, bridges, and squares […] are not allowed to commemorate persons, organisations, events, or dates symbolising communism or any other totalitarian system’. In order to provide as precise a definition of communism as possible, the task to draw up a list of such names was assigned to the IPN.

The catalogue of names propagating communism includes around 150 entries and is worth considering in detail (IPN: Nazwy do zmiany).Footnote a We find there are not only names of relatively unknown local communist activists, but also those of the most influential theorist of communism, Karl Marx (1818–1883); the world-renowned economist Oskar Lange (1904–1965); the pioneer of Polish futurism Bruno Jasieński (1901–1938) or the still fairly popular First Secretary of the PZPR in the 1970s: Edward Gierek (1913–2001).

Beyond the main catalogue of names propagating communism, the IPN also devised three other lists. The catalogue of names that carried ‘a positive resonance and were falsely interpreted under communism’ (e.g. Defenders of the Peace) as well as ‘ambiguous names’ (e.g. Pioneers) would require from the local authorities the passing of a new resolution justifying their use (IPN, Nazwy wymagające). The catalogue of names ‘falsely associated with the norms of the law’ includes only two entries – that of the socialist politicians Stanisław Okrzeja (1886–1905) and Bolesław Limanowski (1835–1935) (IPN, Postaci zasłużone). Finally, the catalogue of names ‘of controversial nature and falsely associated with the norms of the law’ includes such entries as May Day, the Commune of Paris, and the name of the cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin (1934–1968) (IPN Nazwy kontrowersyjne).

Whereas local authorities were given freedom of choice whether ‘ambiguous’ and ‘controversial’ names would be retained or changed, those requiring the passing of new resolutions had to be approved by the IPN and those that the IPN deemed to propagate communism had to be removed within a short period of time. Failure to comply with the law would result in an intervention by the voivode, i.e. the state authority.

The practical application of the new rules led to many controversies and conflicts. An important source of social discontent was the opinions of the IPN about resolutions passed by the local authorities in order to explain the new meaning of an old street name. Two examples of local resourcefulness related to 22 July might serve as an illustration. As in the case of Abramów mentioned above, the authorities of Ostrołęka in north-eastern Poland passed a resolution explaining that the ‘22 July Street’ would commemorate the proclamation of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807. This interpretation was approved by the IPN. Less successful were the authorities of Kruklanki in northern Poland. Their attempt to explain that the ‘22 July Street’ in their village would commemorate the day in 2016 when Pope Francis established the Feast of St Mary Magdalene did not convince the IPN, so the voivode repealed the resolution. In response, the authorities of Kruklanki filed the case to the administrative court. In early 2018, the court ruled that 22 July does not necessarily arouse associations with communism, so the name of the street did not have to be changed (Ulica 2018).

Another source of social discontent was the state’s interventions in cases when the local authorities had ignored the stipulations of the new law. Some decisions taken by the voivodes were formally wrong as they replaced the existing street names with names that had already been used in the public space of a given town or city. Other decisions were problematic for practical reasons as the new names were very long or complicated. Yet other changes irked the local inhabitants, most notably when a commonly accepted street name had been replaced by that of Lech Kaczyński (1949–2010), whose political legacy was highly divisive. As a result, many decisions taken by the voivodes triggered public protests and – as in the case of Kruklanki mentioned above – prompted the authorities of some communities to start a lawsuit (Kałużna Reference Kałużna2018: 163–164).

In response to the reluctance and resistance from below, the parliament decided to restrict the de-communization law. An amendment adopted in June 2017 not only made any protest against decisions taken by the voivodes ineffectual, but also extended the scope of the law on monuments (Act of 22 June 2017). As in the case of street names, the IPN prepared a detailed list including 229 objects propagating communism. In contrast to the case of street names however, the amendment left the local authorities virtually no space for action by reducing the decision-making process to two actors: the voivode’s decision to remove a monument had to be approved by the IPN. In this way, the role of the local authorities was restricted to bearing the costs of the removal. As the dismantling of monuments proved to be a lengthy process, in December 2017 the parliament passed yet another amendment reducing the period for the removal from one year to only 30 days (Act of 14 December 2017). As a result, dozens of monuments associated with communism disappeared from Poland’s public space in early 2018 (Behr Reference Behr2019). Applauding and contesting reactions to this process reflect the overall ambivalence of Poles towards the pre-1989 past of their country.Footnote b

Unsurprisingly, the forced removal of monuments also caused a great deal of controversies and conflicts (Figure 2). On the one hand, local authorities did not share the ‘paranoid viewing’ of the ruling party that had turned ‘public spaces into environments filled with menacing objects’ (Szcześniak and Zaremba Reference Szcześniak and Zaremba2019: 2012) or simply did not enjoy implementing and financing decisions they had not made. On the other hand, the government had to deal with protests expressed by the Russian authorities, media and NGOs. The Russian embassy in Poland meticulously documented the individual instances of removing the Red Army monuments and framed many of them as violations of the bilateral agreement signed in 1994. While publicizing the selected cases, Russian activists and journalists often blurred the distinctions between monuments, memorials and mausoleums.

Figure 2. Top. In early 2018, unknown activists put a banner on the Red Army monument in Olsztyn in northern Poland with the slogan ‘Monument of Gratitude for Enslavement’ and the image of a Soviet soldier harassing a woman. Picture: Zbigniew Woźniak (courtesy of daily Gazeta Olsztyńska). Bottom. In April 2018, shortly after the removal of the ‘Monument of Gratitude’ in Legnica in south-western Poland, members of the grassroots initiative ‘Active Legnica’ placed on the empty pillar a ‘Monument of the Clean Nation’ represented by a rubber duck (kaczka) – a clear allusion to the family name of the PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński. Picture: Andrzej Andrzejewski (courtesy of the author).

Arguably, the most severe Polish–Russian tension revolved around a mausoleum of the Red Army soldiers that had been built in 1945 in Trzcianka in western Poland and was demolished in September 2017. Whereas the Polish authorities insisted that during the exhumation in the early 1950s the remains of all 56 soldiers were relocated to a military cemetery and, subsequently, that the edifice was no longer a mausoleum but a monument, the Russian authorities claimed that the building was still a grave and should not be destroyed (Commentary 2017; Announcement 2017). According to media reports, in late 2020, the families of soldiers buried in Trzcianka filed a lawsuit against Poland with the European Court of Human Rights (Ptak Reference Ptak2020).

This and other Polish–Russian conflicts around Red Army monuments in Poland stem from different understandings of what the notion of ‘place of memory’ actually means – a term that was so prominently featured, but was so poorly defined, in the 1994 agreement. In more general terms however, Polish–Russian struggles around Red Army monuments in Poland reflect the clash of mnemonic interests pursued by the authorities of both countries: whereas Poland is obsessed with purifying the cultural landscape of the communist legacy, Russia strives to maintain the vanishing remains of the Soviet empire – both at home and abroad.

As there is no final report documenting the implementation of the 2016 law, it is difficult to determine how successful the politics of de-communization pursued by PiS has actually been. Still, three conclusions can be drawn. Poland’s cultural landscape continues to be shaped by the material legacies of communism – including some street names and probably 100 monuments (Ferfecki Reference Ferfecki2019). In addition, even if all street names and monuments associated with communism could have been changed or removed, Poland’s public space would not be free from the material legacies of the People’s Poland. Recall that the 237-metre high Palace of Culture and Science, Stalin’s ‘gift of friendship’ constructed in the very centre of Warsaw in 1955 and therefore the largest and most visible leftover of Poland’s communist past, can be neither demolished nor altered because it was listed in the Registry of Objects of Cultural Heritage in 2007. Furthermore, there is a strange irony in the fact that PiS has been pursuing their de-communization project by using means and methods recalling those applied by the PZPR – including the ‘leading role of the party’ in the transformation of Poland’s cultural landscape and the black and white interpretation of history – leaving no space for ambivalence.

Conclusion

The persistence of the dispute around material legacies of communism in Poland’s cultural landscape is revealing. First, it shows both the mobilizing potential as well as the limits of anti-communism and illustrates the ambivalent attitudes of Polish society towards the recent past of the country. Second, it provides clear evidence for the fact that cultural landscape can be a battlefield between political ideologies and popular mythologies and nostalgias. Third, it demonstrates how difficult it has been to provide a legally binding and practically effective definition of communism, and therefore exposes the limitations of the legal governance of collective memory.

In more general terms, the recent Polish experience of renaming streets and removing monuments associated with communism along with radical plans at transforming the public spaces that were developed across time in other countries and cultures, suggests that any attempt at creating a cultural landscape purified from the material remnants of a particular past might be at best an illusory endeavour. No matter who and how one tries to shape the public space according to their idée fixe, cultural landscapes tend to be palimpsestic rather than homogeneous phenomena.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.

About the Author

Kornelia Kończal is Professor of Public History at Bielefeld University, Germany. She is the author and editor of many publications on European history and memory. Her work has appeared in several edited collections and scholarly journals such as East European Politics and Societies, European Review of History, Journal of Genocide Research and Memory Studies. Currently, she is preparing a book on the reconstruction of the post-German territories in East Central Europe after 1945.