What citizens think about Muslim immigrants has important implications for pressing challenges facing Western democracies: concerns over civic cohesion,Footnote 1 the acceptance of asylum policy regimesFootnote 2 and political responses to terrorism.Footnote 3 Yet the scholarly discussion thus far has analyzed citizens’ attitudes toward Muslim immigrants based on a general understanding of anti-immigrant sentiment. We believe this general view fails to capture citizens’ specific attitudes toward Muslim immigrants, whose traditional religiosity is often viewed as a danger to Western liberal values, secularism and democracy.

This article argues that the widespread reservations about Muslim immigrants stem first and foremost from a rejection of fundamentalist forms of religiosity. While this notion has been voiced on several occasions in political theory,Footnote 4 it has not been given due empirical consideration and substantiated with credible evidence. The empirical literature on ‘Islamophobia’Footnote 5 has simply assumed that Muslim immigrants are more religious than the majority population and, importantly, that they are also perceived as such by the citizens of Western democracies.Footnote 6

To better understand citizens’ views of Muslim immigrants, we need to compare their attitudes with those toward other religious groups and – most importantly – separate nominal religion (that is, Muslim vs. Christian) from the type of religiosity (that is, devout, radical or non-practicing). While some (experimental) survey studies distinguish between Christian and Muslim religious practicesFootnote 7 or between immigrants in general and Muslim immigrants in particular,Footnote 8 others hold the ethnicity, country of origin or immigrant status constant in order to contrast Christians with Muslims.Footnote 9 All these studies come to the conclusion that Christians are preferred over Muslims, and thus confirm what has been shown in the literature on immigrant attitudes in general – namely that cultural distance affects how migrants are perceived.Footnote 10 But none of these studies examine anti-religious sentiments: the degree of religiosity is not varied, and only attitudes toward individuals who are both foreign and belong to a particular religion are considered. One exception is Wright et al.,Footnote 11 who distinguish between Muslim women wearing a headscarf vs. a burka. However their study does not clarify the extent to which the headscarf and burka reflect different degrees of religiosity, and in any case it concerns only one specific aspect of religiosity.

To overcome this limitation and to advance our understanding of ‘Islamophobia’ – that is, whether it is a dislike based on immigrants’ ethnic background, religious identity or specific religious behavior – we fielded a representative online survey experiment in the UK in summer 2015. The experimental design is based on a full factorial analysis that manipulates the ethnic background of a fictitious group (Nigerian, Bulgarian or British), their religious identity (Muslim or Christian) and their religious behavior (non-practicing, devout or radical). This puts us in the unique position of being able to disentangle the role of traditional religiosity from ethnicity or immigrant status on the one hand, and nominal religious belonging on the other.

Our results suggest that in general Muslims are not viewed more negatively than Christian immigrants from Bulgaria and Nigeria. More interestingly, actual religious behavior is clearly a more decisive factor than either religious identity or ethnic background. By far the most negative attitudes are toward religious fundamentalists. While this effect is indeed stronger for Muslims than it is for Christians, Christian fundamentalists are clearly resented more than the average practicing Muslim. Therefore we conclude that citizens’ concerns about Muslim immigration are less about immigrants or religious groups per se than they are about extreme forms of religiosity.

This finding has important implications for our understanding of the current challenges of Muslim immigration. One of these implications is that overly simplistic explanations of anti-immigrant sentiments and simple dichotomies between liberal supporters and conservative critics of Muslim immigration break down. While it is well documented that people with liberal values have more positive attitudes toward immigrants,Footnote 12 it has been shown at least for the United States that they are generally also highly critical of traditional Christian forms of religiosity.Footnote 13 It can thus be argued that while liberals are more open to change and care less about collective groups, they see traditional religion and especially Islam as a threat to liberal values and thus reject religious groups – more so than their conservative counterparts.

This ‘intolerance of the tolerant’ is exactly what we find in our data. While conservatives hold more negative attitudes toward immigrants and prefer Christian over Muslim migrants, liberals generally have more positive attitudes toward immigrants. But they also have a pronounced dislike for religious groups, regardless of their nominal faith tradition. Conservative and religious natives, however, have more positive views of religious immigrants than liberal-secular natives. Nonetheless, traditional conservative and religious values are related to more negative attitudes toward immigrants.

Our experimental evidence suggests that a large part of the controversy over Muslim immigration thus stems from the fact that Muslim immigrants face a double opposition: they are rejected because of their immigrant status and because of their particular type of religious behavior. In other words, different group characteristics of Muslim immigrants matter to different degrees to different people, but add up to a general opposition.

Our article contributes to the recent growth in scholarly interest in public attitudes toward immigrants in general and Muslim immigrants in particular.Footnote 14 While a series of studies has sought to explain attitudes toward Muslims,Footnote 15 these tend to focus on theories explaining resentment of immigrants in general. Our article supports a more specific argument to understand opposition toward Muslim immigrants by stressing the religious/cultural nature of this political conflict.Footnote 16 Muslim immigrants are not only disliked for their ascriptive characteristics that cannot be changed but also for their religious behavior, which may be more susceptible to policy intervention. The current political conflict is only partly between Muslims and Christians and between immigrants and native citizens. To a large extent it is also a conflict between political liberalism and religious fundamentalism. We thus also contribute to the sparse literature on anti-religious sentiments that has so far mostly focused on attitudes toward Christian fundamentalists or atheists in the United States.Footnote 17

EXPLAINING ANTI-MUSLIM IMMIGRANT SENTIMENTS

The main explanation for anti-immigrant sentiments put forward in the literature is that immigrants are perceived as a competitive threat to the host society.Footnote 18 The scholarly debate mainly revolves around the question of whether this threat is best understood in terms of economic resources or cultural identities, and tends to favor the latter.Footnote 19 Whereas economic concerns subsume fears over increased labor market competition as well as strains on social security systems,Footnote 20 cultural concerns evolve around issues of national identity, shared values and social cohesion that may be threatened by immigrants.Footnote 21

More recently, several scholars have developed more specific ‘cultural threat’ arguments to explain negative attitudes toward Muslim immigrants to Europe. Some consider Muslims’ cultural beliefs on gender roles or sexual orientation to be incompatible with the liberal and secular lifestyles in these countries.Footnote 22 Others argue that the supposed secularism of European liberal democracy, both in terms of the rules of the game of public life and of collective identities, has been overstated.Footnote 23 Instead, they state that Muslim immigration threatens the collective identities in European host societies because these identities are deeply rooted in Christian traditions. When a society’s political, social and cultural life is defined by strong references to religious tradition, religious minorities pose a direct ‘religious threat’ to this collective identity.Footnote 24

Either way, accommodating Muslim immigrants into European societies often involves changing the existing rules as well as the loss of longstanding traditions, valuable privileges and maybe even everyday habits. Not only do many citizens prefer the status quo and are uncomfortable with change; they also view Muslim newcomers as a threat to their way of life and react with animosity to their practices and demands. Of course, negative reactions to the Muslim community may also be rooted in the perceived security threats associated with Islamic terrorism.Footnote 25

Our theoretical argument builds and expands on these perspectives. Like others before us, we stress the fundamental role of cultural threat in our explanation of anti-Muslim attitudes. And like others, we argue that Muslim immigrants’ religiosity – their religious ideas, practices and claims for religious rights – are the decisive features of this particular group that trigger the feelings of cultural threat in citizens of the host society. We reconcile the perspectives of ‘cultural threat’ and ‘religious threat’ by pointing out that Muslim immigrants pose different types of threats to different segments of the native population. Importantly, and going beyond existing studies, we devise an experimental design that allows us to disentangle the role of traditional religiosity from ethnicity on the one hand, and nominal religion on the other.

THE ROLE OF TRADITIONAL RELIGIOSITY

In a nutshell, we contend that what drives citizens’ antipathy toward Muslim immigrants is primarily a dislike of ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘radical’ forms of religiosity. Muslim immigrants not only have a different ethnic and religious background; they are also more religious, and sometimes their religiosity takes on very traditional forms. Several studies show that Muslim immigrants are more religious than the average citizen in their host societies.Footnote 26 Koopmans studies six Western European countries and finds that while 44 per cent of foreign- and native-born Muslim immigrants have fundamentalist attitudes, only 4 per cent of Christian natives can be considered fundamentalist.Footnote 27

Citizens often perceive Muslims as more religious or fundamentalist than Christians, and are presented as such by the media. Fischer et al.Footnote 28 show that many think Muslims are more intrinsically religious and identify more with their religion than Christians. Pew Forum finds that in Western publics, fears of Islamic extremism are closely associated with worries about Muslim minorities.Footnote 29 According to this study, 61 per cent of the UK population believes that Muslims want to remain distinct from society, rather than adopt their nation’s customs and way of life. A further 63 per cent think that the Islamic identity of resident Muslims in the UK is growing stronger. SaeedFootnote 30 concludes that in British public discourse Muslims are often linked to fundamentalism. According to Eid, Western mediaFootnote 31 presents Muslims as a homogeneous community rooted in fanaticism and oppression.

Traditional religiosity and religious fundamentalism are seen as a threat because their values run counter to modernity.Footnote 32 Whereas modern values emphasize individual freedom, gender equality and political secularism,Footnote 33 all of which had to be wrestled from religious authorities in the past, radical religiosity rejects these cultural and political manifestations of modernity. It is ‘a discernable pattern of religious militancy by which self-styled “true believers” attempt to arrest the erosion of religious identity, fortify the borders of the religious community, and create viable alternatives to secular institutions and behaviors’.Footnote 34 Fundamentalists believe that one should return to the eternal and unchangeable rules laid down in the holy scriptures, that these rules allow only one interpretation that is binding for all, and that religious rules should have priority over secular laws.Footnote 35 To the extent that religious fundamentalists do not merely withdraw from general society but seek to actively shape it in accordance with their religious views, they pose a considerable challenge to the prevailing social and political order.

This role of traditional religiosity is important for our understanding of anti-Muslim sentiments. Muslim immigrants face a double opposition in the public because they trigger different fears and feelings of dislike in different segments of the population. Whereas conservative and politically right-leaning citizens are more critical of immigrants and Islam in general, they hold more favorable views toward traditional religiosity. Liberal and politically left-leaning citizens, however, are open to immigrants and members of different faiths, but they tend to be critical of the values associated with traditional forms of religion. The divide ‘over lifestyle and cultural dominance issues such as abortion, gay rights, gender roles, and the place of religion in the public sphere’ makes liberals oppose religious fundamentalists.Footnote 36 This leads to an uneasy situation in which different citizens dislike Muslim immigrants for quite different reasons.

Some research supports the claim that liberals generally dislike fundamentalist or extreme forms of religiosity. Yancey finds that factors that explain positive attitudes toward out-groups – such as education or political ideology – have inverse effects on attitudes toward Christian fundamentalists: ‘the characteristics that predict acceptance of nontraditional religious groups are inversely correlated to rejection of fundamentalists’.Footnote 37 Bolce and de MaioFootnote 38 come to similar conclusions and show that anti-fundamentalist attitudes are especially widespread among highly educated and secular persons. This confirms the study by Hyers and Hyers,Footnote 39 who show that Christian fundamentalists feel discriminated against in secular universities. According to Yancey,Footnote 40 fundamentalists are seen as a danger to the development of progressive values. They are viewed as conservative, intolerant and culturally backwards. It remains an open question, however, whether these resentments themselves constitute cultural or religious prejudices or an attempt to defend democratic, pluralistic values.Footnote 41 Most likely, they are both.

With regard to traditional Muslim religiosity, HelblingFootnote 42 shows that while people with liberal values have more positive attitudes toward Muslims than those with conservative values, this effect disappears when it comes to the acceptance of the Muslim headscarf. In a similar vein, in several countries support for banning the full Islamic veil is evenly distributed across education levels and political ideologies, and is even greater among high-income groups.Footnote 43 The headscarf may be perceived as a religious symbol and therefore be opposed due to anti-religious sentiments or the rejection of traditional forms of religiosity. It is also often seen as a symbol of gender inequality and the oppression of women. Sniderman and HagendoornFootnote 44 show that the role of women and the general lack of self-determination in traditional Muslim societies is a frequent liberal criticism of Islam.

In sum, and given previous research, we expect that people with liberal values generally have more positive attitudes toward immigrants than conservatives, irrespective of their cultural/religious background. However, when it comes to migrants who are religious or even radical (irrespective of whether they are Christians or Muslims) this positive attitude disappears and concerns over the loss of liberal values trump general tolerance.

Apart from triggering the ‘intolerance of the tolerant’, the traditional religiosity of Muslim immigrants may also reveal the ‘tolerance of the intolerant’. Religious people are usually more conservative, and fundamentalists more right-wing authoritarian.Footnote 45 Whether religiosity leads to negative or positive attitudes toward out-groups has been disputed for a long time.Footnote 46 Recent empirical studies suggest that agnosticism leads to more toleranceFootnote 47 and that religiosity leads to more negative attitudes toward migrants and more ethnocentrism.Footnote 48 Others show that religiosity does not lead to out-group hostility when one controls for fundamentalist ideas.Footnote 49 It thus appears that it is mainly fundamentalism that is related to prejudices against other minorities, including ethnic and racial minorities.Footnote 50

However, if liberals reject traditional religiosity, it is plausible to assume that religious natives will show solidarity toward religious immigrants since they too constitute a marginalized group in secular and liberal societies.Footnote 51 This leads us to expect that for religious natives, negative attitudes toward immigrants in general are reduced if these immigrants are religious themselves. Given previous research, we expect them to resent migrants in general more than non-religious people, as they are more conservative. However, we expect these negative attitudes to decrease when it comes to religious migrants, as religiosity is seen as a common identity trait in secular Western societies.

DATA AND METHODS

The Survey Experiment

To test our argument about the role of religiosity in attitudes toward Muslim immigrants, we conducted an online survey experiment that asked respondents to indicate their feelings toward randomly assigned groups. The experimental design was based on a full factorial analysisFootnote 52 that manipulated the immigrant status of a fictitious group (immigrants from Bulgaria, Nigeria or native Britons), their religious denomination (Muslim or Christian) and their degree of religiosity (non-practicing, devout or radical) (see Appendix Table A1 for an overview of all combinations of vignettes).Footnote 53 The vignette study was part of a larger UK representative panel survey of almost 4,500 respondents, fielded in June 2015 and executed by YouGov.Footnote 54 We only included respondents who identify as White British in our analyses. This group makes up 90 per cent of the sample. Within this group, only fifty-three persons indicated that they were not Christian, and five reported that their religion was Islam.

Each respondent received one vignette that reads as follows (the underlined parts were randomly varied across respondents, see Appendix Table A2 for all question wordings.):

‘Now we are interested in your opinion regarding some groups that are currently active in social and political life in Great Britain. Imagine a group of immigrants from Nigeriawho are devout Muslimswho regularly go to the mosque and regularly pray at home. Members of this group want to hold public rallies and demonstrations for a better recognition of their interests in Britain.’

We restricted our study to Muslims and Christians, as the former constitute a major and controversial immigration group in Great Britain (and most Western European countries) and the latter represents the traditional majority religion in Great Britain.Footnote 55 We described migrants as coming from either Bulgaria or Nigeria as we wanted to select countries where both Muslims and Christians live to make the vignettes realistic (this would preclude Pakistan, for instance). In Nigeria, Muslims make up roughly 40 per cent and in Bulgaria 10 per cent of the population. Moreover, both nationalities constitute important migrant groups in Great Britain. We refrained from including more controversial immigration groups such as migrants from Arabic countries that are often related to terrorism, as respondents might already have very strong opinions about these groups, and since the effects of perceived or real security threats are not part of our study. Syrians were not included, as they did not make up an important group of migrants (or asylum seekers) in Great Britain at the time of the data collection, which took place a couple of months before the refugee crisis from that country started.

Due to its colonial past, there have been large migration flows from Nigeria to Britain over the last five years. While the Bulgarian community in Britain was rather small for a long time, the EU enlargements in the mid-2000s have led to increased immigration from Eastern Europe, including Bulgaria. Differentiating between Bulgarian and Nigerian migrants also allows us to vary cultural distance and to differentiate between EU and non-EU migrants. We also included vignettes that described the groups as natives to have a reference group and to better compare the effect of ethnicity to the effect of religion and religiosity.

Since respondents might have different understandings of what the different degrees of religiosity mean, we provided short definitions in the survey, which allows us to guarantee a higher degree of internal validity. In line with the literature, we differentiate between three degrees of religiosity that are defined as follows: non-practicing (persons who never go to church/mosque and never pray), devout (people who regularly go to church/mosque and regularly pray) and radicals (people who think there is only one interpretation of the Bible/Koran, and that it is more important than British laws).

Of course, it is still possible that people connote additional meanings with these three labels. For example, although we define radicalism as an extreme form of religiosity, some respondents may think of terrorism when they hear this term. This is, however, a general problem with several terms used in the vignettes. As Sides and GrossFootnote 56 convincingly demonstrate, groups simply described as ‘Muslims’ or ‘Muslim-Americans’ are seen as more violent, even without the specification ‘radical’. Our study aims to deal with this problem and to disentangle the different meanings and perceptions about Muslims by separating nominal belonging from actual types of religious behavior.

MAIN DEPENDENT AND INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

After another vignette on the authorities’ decision to either ban or permit these public demonstrations, which we used for another analysis,Footnote 57 we asked respondents to indicate their general feelings about the group described in the vignette:

‘Now we would like to know what your general feelings are about this group. We’d like you to rate them with a feeling thermometer. Ratings between 50 and 100 degrees mean that you feel favourably and warm toward them; ratings between 0 and 50 degrees mean that you don’t feel favourably toward them and that you don’t care too much for them. If you don’t feel particularly warm or cold toward them you would rate them at 50 degrees.’

The feeling thermometer score constitutes our dependent variable. It reflects the general attitudes toward the groups that are presented in the vignettes and varies between 0 (very negative) to 100 (very positive). As documented in Appendix Table A3, which provides summary statistics, the mean attitude toward all groups is 38.Footnote 58 The feeling thermometer allows us to measure Islamophobia, which we define as an unnuanced, negative and emotional assessment of Muslims. The feeling thermometer also allows us to make very fine-grained distinctions, which is of particular importance for subjective variables that ‘can perhaps be thought of in terms of a continuum that reflect direction and intensity and perhaps even have a “zero” or neutral point’.Footnote 59

Our key independent variables are the three characteristics that we presented to the respondents and that varied across the vignettes (nationality, religion, religiosity). The variables are coded 1 if a respondent received a vignette with the respective characteristic and 0 if not. One-third of the respondents received the native frame, and two-thirds one of the two immigrant frames (Bulgarians/Nigerians). Half of the respondents received the Christian and the other half the Muslim frame. Finally, each of the three religiosity frames was assigned to one-third of the sample, respectively (see Appendix Tables A1 and A3).

FURTHER VARIABLES

We further measured respondents’ degree of liberalism and religiosity. We used two alternative measures to measure liberal/conservative attitudes. The first is a simple left–right scale. Respondents were asked to position themselves on a scale from 1 (very left-wing) to 7 (very right-wing). As we present in Table A3, left- and right-wing voters are evenly distributed in this sample with a mean value of 3.97. For some of the analyses we split the respondents into two groups – those who take positions left or right of the center (that is, with scores smaller or greater than 4). Each of the two groups makes up roughly 35 per cent of the sample.

The second measure of cultural liberalism is an index built from three items. Respondents were asked to indicate on a scale from 1 (liberal) to 5 (conservative) how much they (dis-)agree with the statements that it is better if women with young children do not work, that in Britain men and women interact in an overly unreserved way, and that they prefer to have homosexuals among their friends. On average, the group of people with liberal values is a little larger than the group with conservative values. This appears in Table A3 that indicates a mean value of 2.4. For some of the analyses the scale is split at the mean to differentiate between liberals and conservatives (smaller or greater than 2.4).

In order to capture respondents’ religiosity we distinguish between the same three groups as in the vignettes. To measure religiosity we asked the respondents to indicate on a scale from 1 to 11 how religious they see themselves, regardless of whether they belong to a particular religion. In a second question they were asked to indicate on a scale from 1 to 7 how often they attend religious services apart from special occasions such as weddings and funerals. We built an index from the average of these two items (α = 0.68). We consider respondents to be devout if they score greater than the mean of this measure.

To measure radicalism, respondents were asked to indicate on a scale from 1 to 5 to what extent they (dis-)agree with the statements that there is only one interpretation of religious rules and every religious person must stick to that, and that religious rules are more important to them than British laws. We again built an index combining these two items (α = 0.63). We defined radicals as respondents who at least partly agree with both statements (same or greater than 3.5). This group makes up around 5 per cent of the sample. This roughly corresponds to the 4 per cent of Christian fundamentalists that Koopmans found in six Western European countries.Footnote 60

RESULTS

Ethnicity, Religion or Religiosity?

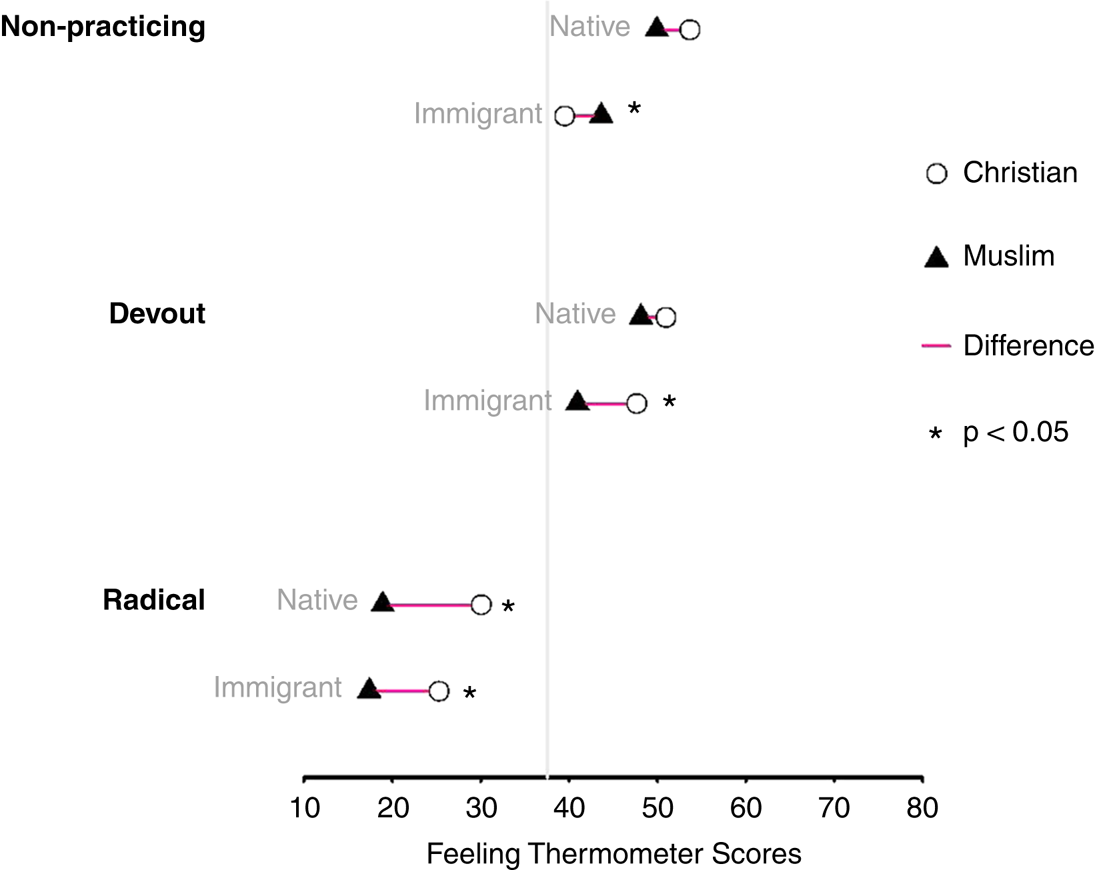

Figure 1 presents the average feeling thermometer scores that respondents gave toward the groups we differentiate in our survey experiment. The average feeling thermometer score across all groups is around 38 (vertical gray line). The key comparison we are interested in is the difference in attitudes toward Christians (white circles) and Muslims (black triangles),Footnote 61 and how this difference behaves when the groups are described as more or less religious and whether they are immigrants or native British.Footnote 62 The horizontal line segments indicate the difference.

Fig. 1 Feeling thermometer scores toward different social groups defined by immigrant status, religion and religiosity Note: the key comparison is the difference in attitudes toward Christians (white circles) and Muslims (black triangles), which is indicated by the horizontal line segments. The vertical gray line shows the average feeling across all groups.

The experimental results support our argument concerning the role of traditional religiosity in understanding citizens’ attitudes toward Muslim immigration. First of all, if we focus on groups of native British who are either non-practicing or moderately religious, citizens do not have significantly different feelings toward Muslims and Christians. For completely secular groups the difference in feeling thermometer scores is only −3.8 [95 per cent CI: −8.26, 0.38] and for devout groups only −2.8 [−7.39, 1.27]. Secondly, we find that non-practicing and devout immigrant groups are only slightly less liked than natives. More importantly, Muslim immigrants are not necessarily resented more than Christians. Quite to the contrary, regarding non-practicing immigrants, Muslims are even liked a bit more than their Christian counterparts (4.2 [1.53, 6.71]). This empirical evidence clearly suggests that, controlling for religiosity, citizens are not concerned with the difference between Muslims and Christians per se. But this changes once religiosity enters the picture. For devout immigrants the difference between Muslims and Christians is significant (−6.7 [−9.45, −3.90]), indicating some reservations against Muslims’ religiosity.

Thirdly, and in line with our argument, citizens have a pronounced dislike for radical forms of religiosity. Fundamentalist religious groups receive markedly lower feeling thermometer scores than all other groups. This holds for both Muslims and Christians as well as for immigrants and natives. Importantly, citizens view native Christians who are fundamentalists less favorably than they view Muslim immigrants who are simply devout practitioners of their faith (the difference is −10.9 [−14.35, −7.28]). This evidence supports the notion that a social group’s particular religious behavior – and not only its immigrant status or faith tradition – is the key determinant that drives citizens’ likes or dislikes. However, Muslim fundamentalists are clearly the least liked group of all. Among natives, the difference in feelings toward Muslim and Christian radicals is quite pronounced and significant (−11 [−15.2, −6.97]). The same holds for radical immigrant groups, where Muslims are also less liked than Christians (−7.9 [−10.8, −5.22]). These findings make clear how important it is to differentiate between different types of Muslim immigrants, and that they are not generally seen in a more negative light than other immigrants. Instead, it is fundamentalist religiosity that produces negative attitudes.

CONSERVATIVE AND LIBERAL VIEWS ON MUSLIM IMMIGRANTS

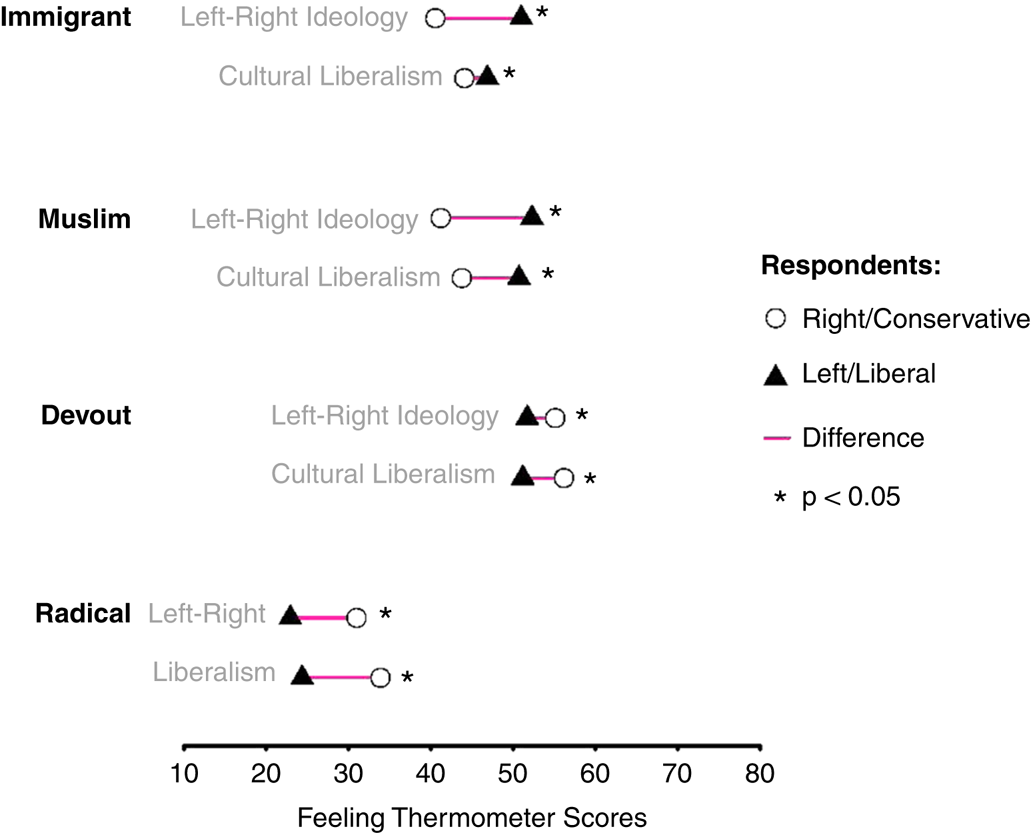

Having established the role of traditional religiosity in anti-immigrant sentiment, we now turn to the question of how respondents’ political ideology and values interact with immigrants’ group characteristics. To allow for alternative measurements of ‘conservatism’ and ‘liberalism’, we group respondents using a left–right ideology scale as well as an index for cultural liberalism. We present the results in Figure 2. Here, the key comparison is the difference in feeling thermometer scores between politically right-leaning or conservative respondents and their left-leaning or liberal counterparts. The horizontal line segments indicate the difference between these respondent types. Full regression models with multiplicative interaction terms are documented in Appendix Table A4.

Fig. 2 How respondents’ political ideologies and values interact with group characteristics Note: we report average feeling thermometer scores. Results are based on the regression models documented in Appendix Table A4. The key comparison is the difference in feeling thermometer scores between politically right-leaning or conservative (white circles) and left-leaning or liberal respondents (black triangles). The horizontal line segments indicate the difference between these respondent types.

The experimental findings suggest that differences in political ideology and liberal values are clearly related to different feelings toward different social groups. First, and in line with our expectations, citizens who identify themselves as politically left and who hold culturally liberal views have significantly warmer feelings toward immigrants. When compared to right-leaning and conservative citizens, the respective differences in thermometer scores are 9 [95 per cent CI: 12.4, 5.59] and 3.2 [6.1, 0.3]. Secondly, in general they also have significantly more positive views of Muslims (in fact, they even view Muslims more favorably than Christians, also see Appendix Table A1). The differences between left/liberals and right/conservatives are 9.7 [12.9, 6.4] and 7.3 [10.0, 4.6] points on the feeling thermometer, respectively.

Thirdly, however, left-leaning and culturally liberal respondents have less warm feelings for religiously devout groups. The differences when compared to the right-leaning and more conservative citizens are significant (4.8 [0.8, 8.8] and 4.6 [1.3, 8.0]). This finding is even more pronounced when we look at attitudes toward radical groups. Although both left/liberals and right/conservatives have rather cool feelings toward fundamentalist religious groups, they are markedly less liked by the political left and culturally liberal. The differences between ideological camps are statistically significant and roughly twice as large as the ones found for devout groups: 9.5 [5.5, 13.4] and 9.2 [5.9, 12.5].

This finding has an important implication: if it were the case that respondents’ negative reactions to religious radicalism were merely the product of security concerns, and that respondents simply equated radicalism with ‘terrorism’, we would expect conservatives to react much more negatively to religious radicals than liberals. This is so because, arguably, conservatives are far more concerned with issues of national security than liberals. But this pattern is not at all what we see in our data: liberals – who place less emphasis on national security – have more negative feelings about religious radicals than conservatives do. We argue that this has to be explained by reference to cultural concerns.

Additional analyses of the effects of native respondents’ religiosity produce similar patterns (see Appendix Figure A1 and Table A6). The degree of natives’ religiosity has no (or hardly any) effect on anti-immigrant sentiment. Yet devout citizens have significantly more positive feelings toward religious groups than secular citizens. And fundamentalist citizens have significantly warmer feelings than regularly practicing citizens. This pattern holds for both devout and radical immigrant groups. This again may indicate that radicalism is not simply equated with security threats. Native Christian radicals would be expected to be as concerned as non-religious natives.

Figure 3 takes the analysis one step further and presents the interaction of respondents’ political ideology and cultural values with immigrants’ religion and religiosity. As before, we find that radical religious groups are always less liked than merely devout groups, no matter whether they are Muslim or Christian. And this general pattern holds for both leftist/liberals and rightist/conservative respondents. However, respondents who consider themselves politically left or culturally liberal discriminate less between the two faith traditions: for them, only a group’s actual religiosity is decisive. Since Christian radicals, at least in the European context, are not associated with terror, this again points to cultural and not merely security concerns. Right-wing and conservative respondents, however, have a clear preference for Christian groups. They like devout Christians more than devout Muslims and fundamentalist Christians more than fundamentalist Muslims. No such pattern can be observed for secular groups.

Fig. 3 How respondents’ political ideologies and values interact with religious immigrant characteristics Note: we report average feeling thermometer scores. The results are based on the regression models documented in Appendix Table A5. The key comparison is the difference in feeling thermometer scores between politically right-leaning or conservative (white circles) and left-leaning or liberal respondents (black triangles). The horizontal line segments indicate the difference between these respondent types.

CONCLUSION

Muslim immigrants to Western democracies tend to be more traditionally religious than the citizens of their host societies.Footnote 63 Therefore they not only differ in terms of ascriptive features such as ‘ethnicity’ and ‘religion’, but also in their actual religious behavior. We argue that Muslim immigrants’ religiosity is the key to explaining citizens’ attitudes toward this particular immigrant group. While this argument can be found in political theory,Footnote 64 it has not yet been established by empirical evidence. Several studies that have investigated attitudes toward Muslims or compared attitudes toward both Christian and Muslim immigrants have also made similar claims.Footnote 65 But none of these studies has directly addressed the degree of religiosity of Muslims; they have simply assumed that people see Muslims as religious. Based on the results of a survey experiment, we provide such evidence and show that citizens’ uneasiness with Muslim immigration is indeed first and foremost the result of a rejection of fundamentalist forms of religiosity.

Our results contribute to our understanding of citizens’ anti-immigrant sentiments because they suggest that common explanations, which are based on simple dichotomies between liberal supporters and conservative critics of immigration, need to be re-evaluated. We find that while all three characteristics – ethnicity, religion and religiosity – affect citizens’ feelings toward immigrants, they do so to quite different degrees for different people. While the politically left and culturally liberal have more positive attitudes toward immigrants than right-leaning individuals and conservatives, they are also far more critical of religious groups. Therefore, we conclude that a large part of the current political controversy over Muslim immigration has to do with a double opposition: Muslim immigrants are met with reservation by some because of their immigrant status or religious belonging, and from others because of their particular type of religious behavior, which is often seen as incompatible with liberal and democratic values.

Although we expect to find similar patterns in other Western countries, our experimental evidence remains restricted to the UK and thus we cannot exclude the possibility that context matters. As Helbling and TraunmüllerFootnote 66 have recently demonstrated in a comparative study, the political regulation of religion is related to citizens’ attitudes toward Muslims and their religious demands. It might be interesting to investigate the extent to which these policies also affect how people differentiate between different forms of religiosity. The public role of religion also sets European states apart from the United States, where religion is less regulated yet Christian religious fundamentalism is more widespread. In line with our argument, we would assume that this suggests a higher acceptance rate of fundamentalist religiosity at the aggregate level. It is, however, rather unlikely that such a situation would also produce more positive attitudes among liberals. As several studies have already shown, liberals have particularly hostile attitudes toward Christian fundamentalists in the United States.Footnote 67 There is little reason to believe that this might be different for Muslim fundamentalists. At the same time, Muslim immigrants in the United States may come from different countries of origin, mostly the Middle East, which may introduce further concerns about security threats.Footnote 68

An important implication of our results is that they stress the importance of differentiating between different kinds of Muslim immigrants, and that citizens do not always see them in a more negative light than they would other immigrant groups. This is crucial to know, as the majority of Muslim immigrants are not fundamentalists.Footnote 69 For one, this supports Brubaker’s recent argument that Muslims are ‘not a homogeneous and solidary group but a heterogeneous category’ and should be treated as such in research.Footnote 70 At a minimum, this involves the need to separate religious identity from actual religious behavior, and to recognize that Muslim identity cannot be equated with traditional forms of religious values and practices without losing analytical clarity.

Our findings also contribute to a better understanding Islamophobia by providing a more nuanced view of the religious/cultural nature of the political conflict surrounding Muslim immigration to Western democracies.Footnote 71 Increasing inflows of Muslim immigrants in recent decades have highlighted the importance of dealing with religious customs and claims for religious rights. Muslim immigrants are not disliked per se. In fact, secular Muslim immigrants are not viewed more negatively than non-religious Christian immigrants at all. The current political conflict is not about Muslims versus Christians or immigrants versus natives, but about political liberalism versus religious fundamentalism. We have suggested here that radical religion is mainly rejected on cultural grounds because it is seen as incompatible with modern cultural and political values. But of course, radical religion may also be perceived as a security threat, as is clearly the case with international Islamic terrorism. We hope future experimental designs will be better able to address this possibility and allow us to further disentangle the sources of anti-Muslim sentiment.