INDONESIAN FINANCIAL TECHNOLOGY

Overview

In Indonesia, the Central Bank (Bank Indonesia) defines financial technology (FinTech) as follows:

Financial technology is the use of technology in the financial system, which results in products, services, technology, and new business models. The products or services impact the monetary and the financial system stability and the efficacy, security, and innovations in payment systems. (Bank Indonesia 2020)

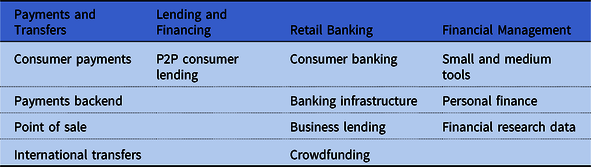

According to the Indonesian Central Bank Regulation No. 19/12/PBI/2017 concerning FinTech, there are four types of FinTech services in Indonesia (FinTech Indonesia 2020):

-

(1) Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending and crowdfunding services by offering loans in rupiah currency directly between lender and borrower, facilitated by technology. Examples are Kredivo, KoinWorks and Investree. Besides P2P lending, there is a FinTech innovation in crowdfunding that provides shares issued by holding companies, called equity crowdfunding, including Santara, Bizhare and CrowdDana.

-

(2) Investment and risk management is another FinTech innovation that assists the community in managing financial planning, such as Bareksa, Cekpremi and Rajapremi.

-

(3) Payment, clearing and settlement startups offer payment gateway or e-wallet services, including Kartuku, Doku and Finnet.

-

(4) Market aggregators are the last FinTech services that use an online portal to provide financial information for the targeted audience. These services offer information, financial tips, credit cards and investments. The market aggregators include Cekaja, Cermati and KreditGoGo (see Table 1).

Table 1. Financial Technology Services Available

Source: Bank Indonesia.

Recently, the vast growth of FinTech companies in Indonesia demonstrates the increasing number of Internet users in the community. In 2020, P2P lending dominated the Indonesian market, followed by digital wallets like GoPay, OVO and DANA (Bank Indonesia 2020). FinTech companies that provide services on capital markets and data analytics are the third biggest users. The last ones are financial management, crowdfunding and insurance services.

Another peculiar advantage of the FinTech sector is its ability to link financial transactions covering 13,000 islands in Indonesia. FinTech has been able to reduce the problems for small- and medium-scale enterprise (SME) funding and expand financial inclusion due to the high use of mobile telephony. The use of multiple SIM cards facilitates multiple business transactions all at the same time.

Risks and Challenges of Financial Technology

FinTech services raise severe risks to the financial system. These include cybercrime, misinformation, abuse of fake identities, money laundering and terrorist financing. Terrorists’ use of FinTech will involve occasional use for specific and limited purposes, including: (a) raising funds or procuring illicit items on the Internet; (b) soliciting donations in crowdfunding campaigns conducted on social media and encrypted messaging platforms; and (c) transmitting funds internationally among members of terrorist networks using P2P value transfers.

In addition, the terrorist actors may use FinTech for its anonymity and pseudonymity. Ultimately, FinTech’s being untraceable may expand its utility to terrorist actors. For example, FinTech apps are growing in number and availability. They present law enforcement agencies with substantial challenges in preventative efforts such as early detection relative to the FinTech sector.

The potential of FinTech as a method of international funds movement is clear to all types of customers, including terrorists and terrorist organizations. Due to its digital system, there are growing concerns among Asian law enforcement agencies that FinTech may be increasingly tapped for various illicit purposes. Messaging applications and social media are other channels through which terrorist and extremist actors can seek anonymity. In the terrorist crowdfunding campaigns identified to date, potential donors are often directed via Twitter and Facebook to encrypted messaging applications such as Telegram. The potential benefits of this approach are clear: crowdfunding campaigns allow sympathizers to “support the cause” without having to leave the confines of their own home, and with an additional layer of anonymity around their communications.

Moreover, one can have unlimited access and multiple digital wallets for FinTech. The FinTech apps are readily and easily portable, with a distinct advantage over carrying physical cash. One can carry FinTech apps across borders by keeping a software wallet application on a phone, tablet or another portable device. FinTech mobile wallet cards can serve a similar function, as they can be loaded with the online digital wallet and carried from one place to another.

A significant attraction for FinTech that may hold some appeal for terrorist actors is its ability to enable value transfers internationally while avoiding regulated intermediaries. FinTech provides a relatively effective means for transferring value P2P across borders. This feature is attractive to terrorists who receive payments from supporters anywhere in the world without the payments having to pass through a bank or other financial institution. One case suggests that terrorist actors may be attempting to exploit this feature to move funds. For example, in 2017, Indonesia’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) reported that Bahrun Naim, a jihadist who planned the 2016 attacks in Jakarta, used PayPal and Bitcoin to transfer funds from the Middle East to support Indonesia-based terror cells across Java.

The Abuse of Technology in Facilitating Terrorist Financing

Generally, digital technology benefits terrorist groups in conducting direct solicitation activities. The Internet facilitates those direct solicitations by using emails, sites, chat rooms and other platforms to gather donations from members, supporters and sympathizers worldwide. Besides commercial sites, social media is also used by terrorist groups to promote campaigns and raise funds. Through social media, terrorists can grasp a more influential audience through P2P communication, including chats and forums, social networks like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and mobile applications for personal communication, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, or safer communication networks Surespot and VoIP. Some case studies feature terrorist groups that raise money to fund terror. The Global Jihad Fund, associated with Usama bin Laden, publishes a website and provides bank account information that urges donations to assist various jihad movements globally by offering funds for military training and arms purchases (U.S. Department of Treasury 2020). In Saudi Arabia, Islamic State in the Levant (ISIL) groups actively collected donations via social network channels and used prepaid cards. They communicated through Twitter and required potential donors to continue contacting via Skype. Those who would donate their funds had to buy international prepaid cards and inform the terrorist groups of the card number so that the fundraisers could send the information to one member based in a neighbouring country close to Syria. This person of interest then sold the card number at a lower price and offered cash to ISIL networks (Planet Compliance 2021).

Another case identified in Russia shows the misuse of e-wallets to collect funds for supporting terrorists and families. A group managed a large-scale crowdfunding scheme through social networks and the Internet by registering e-wallets, credit cards and mobile phone numbers. They generated a narrative describing the fundraising activities to support Syrian refugees, particularly those in need of medical and financial aid, by building mosques and schools. However, the funds collected were transferred to credit cards or e-wallets, then moved circularly among bank accounts. Finally, the group withdrew the money in cash and transported it by couriers before channelling the funds to assist terrorists and their families (Planet Compliance 2021).

In Indonesia, only a few cases have identified the abuse of FinTech innovations, including PayPal, Bitcoin and online P2P lending companies. This section discusses those case studies in two parts. The first part explores three Internet and social media abuse cases, including cybercrime. The second part examines five cases related to the misuse of FinTech services. The first part of the Indonesian case study analyses the Internet and social media in facilitating fundraising activities among terrorist groups by presenting the cases of Rio Adiputra, Cahya Fitrianta and Bahraini Agam’s networks. In 2012, the Indonesian police arrested Cahya Fitrianta, Marwan and Rizki Gunawan for their involvement in cybercrime.

The crime proceeds would have been used for supporting a terrorist group in Poso, the Mujahidin Indonesia Timur, led by Santoso. This includes organizing military training. They were executing a church bombing in 2011 and supporting terrorist widows, jihadists and terrorist inmates’ wives. From 2010 to August 2012, Marwan and Rizki Gunawan worked with Cahya Fitrianta, a male terrorist who hacked a multilevel marketing website, speedline.com. By activating non-active members and obtaining their security identities, they produced funds up to US$50,000 and transferred the money to some false accounts and the accounts of Cahya’s wife, Nurul Azmi Tibyani (Laksmi Reference Laksmi2017).

In 2015, Rio Adiputra was sentenced to four years for a terrorism case. He requested funds, ordered by Iron, directly from the networks in Bima. The funds were used to support terrorist wives left by their husbands who joined the Santoso group. Adiputra received funds of IDR 1.5 million from Hafid, Fadli and Lahmudin, members of Santoso’s group. He spent the money to buy tickets to Poso, purchase fertilizers as explosives and rental vehicles. Adiputra used a WhatsApp messenger platform to communicate among terrorists. The closed encrypted platform enabled them to raise funds without being intercepted by the authorities.Footnote 1

Last, the abuse of the Internet to facilitate terrorists’ fundraising techniques was also found in the case of Bahraini Agam and Rio Priyatna Wibawa. In 2016, the police caught those terrorists concerning a bombing plan targeting 120 offices of the Regional People’s Representative Council all over the country. The group planned to produce and run an illegal drugs business. They gathered the funds from members and sympathizers by promising that the money would be used to support the establishment of an Islamic State in Indonesia. They used closed Facebook and Blackberry groups to promote their jihad efforts to collect the money. They also developed the plan of building an illegal business to produce and sell drugs, the methamphetamines named Blue Ice, as another way to generate more money for terrorism. The plan to produce Blue Ice was put into effect between May and August 2016. Rio spent 14 days making the drugs; however, the results were poorly completed because of limited tools and equipment. The remaining chemical substances were then used to craft DNT (dinitrotoluene) explosives. However, the police thwarted this plan (Badan Nasional Pennungulangan Terrorisme 2017).

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The FinTech sector that enables P2P lending pertains to a novel way of matching potential investors with borrowers and allocating the risks involved, which FinTech facilitates.

The digital and communications technology empowers electronic contracting; the divisibility of loan contracts across many lenders and investors; a broader investor diversification; added information in credit assessment and risk-based loan pricing; and a plethora of algorithmic methods for matching multiple borrowers and lenders and determining the appropriate interest rates. Unlike traditional banking, P2P operators do not take on credit risk and, by matching investors with borrowers, do not provide investors with liquidity or take on interest rate risk (Chen Reference Chen2022).

Although Indonesia’s FinTech industry has made significant strides, the auxiliary sectors such as cybersecurity and data protection support have been inadequate. Cybersecurity experts predict that the total cost of cybercrime will increase by 15% per year in the next five years, reaching US$10.5 trillion annually by 2025, up from US$3 trillion in 2015 (GlobeNewswire 2021).

INTERPOL’s Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Cybercrime Operations Desk, with the collaboration of the law enforcement agencies in the region and INTERPOL’s private sector cybersecurity partners, identified these cyber threats:

-

(1) Business email compromise campaigns, which result in large and medium businesses suffering major losses;

-

(2) Phishing – cybercriminals are utilizing global communications technology to deceive victims;

-

(3) Ransomware – cybercrime targeting hospitals, medical centres and public institutions for ransomware attacks has increased rapidly. Cybercriminals targeted health institutions due to the pandemic in many countries;

-

(4) E-commerce data interception poses an emerging and imminent threat to online shoppers, undermining trust in online payment systems;

-

(5) Crimeware-as-a-service – pertains to a threat where actors can manipulate situations that include cybercriminal tools and services, including non-technical ones, to the extent that anyone can become a cybercriminal with low “investment”;

-

(6) Cyber scams. Cybercriminals have revised their online scams and phishing schemes, impersonating government and health authorities to lure victims into providing their personal information and downloading malicious content; and

-

(7) Cryptojacking pertains to the hacking of cryptocurrencies.

INTERPOL’S ASEAN Desk and ASEAN Cyber Capacity Development Project have four pillars: enhancing cybercrime intelligence for effective responses to cybercrime; strengthening cooperation for joint operations against cybercrime; developing regional capacity and capabilities to combat cybercrime; and promoting good cyber hygiene for safer cyberspace (INTERPOL 2021).

Indonesian authorities regularly update their policies on lenders, including the P2P sector. For example, in August 2022, Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK)) set a minimum capital requirement for lenders at IDR 25 billion (US$1.67 million), up from IDR 1 billion previously, with an additional demand to maintain at least IDR 12.5 billion of equity at all times (FinTech Indonesia 2020).

MISUSE OF FINTECH

This research also cites the five cases closely related to the misuse of FinTech for terrorism purposes, including the cases of the Solo bombing attack, Leopard Kumala, Bahrun Naim, Adi Ale Sapari and the Abu Ahmed Foundation (AAF). On 5 July 2016, Nur Rohman exploded himself in the local police office in Surakarta, Central Java. Later, the police identified Munir Kartono and Dwi Atmoko, who claimed that their group linked with the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), particularly with the network of Bahrun Naim, had planned such an incident. Naim used a third-party PayPal account owned by Hadrian to move the money from overseas to Indonesia. The communication was conducted on Telegram, an encrypted messaging platform, to discuss the attack plan and the arrangement to transfer the funds.Footnote 2

Next, the first terrorism case using Bitcoin was a lone-wolf case involving Leopard Wisnu Kumala in 2016. The Tangerang District Court convicted him because he detonated a triaceton triperoxide (TATP) bomb in a local shopping centre. Leopard extorted the shopping centre manager, requested Bitcoin money through blackmailing, and asked the manager for IDR 300 million. The manager was only able to send a sum of Bitcoin money. Disappointed by the manager, Leopard exploded a bomb inside the shopping centre (Cahya Reference Cahya2015).

In the same year, the public was also surprised by terrorist financing activities done by Bahrun Naim through abusing cryptocurrency for terrorism financing. Besides using PayPal, he also utilized Bitcoins to transfer money to his networks back home in Indonesia to fund terrorist activities. Bahrun Naim directed his followers to launder the money through cryptocurency accounts, including Bitcoin wallets, besides carding techniques, as published in his online manual in 2016 (Arianti and Yaoren Reference Arianti and Yaoren2020).

Besides the Bahrun Naim case, the authorities also investigated illicit financial transactions involving the AAF. This foundation is an Indonesia-based jihadist-aligned fundraising network which is suspiciously affiliated with the Al Qaeda-linked Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. The AAF promoted humanitarian assistance and jihadist-supporting activities to help oppressed Muslims in Palestine, Syria, Xinjian and Burma. In 2018, the group publicized its activities via various social media platforms, including Facebook, Telegram, Instagram and Twitter. Relying on charity programmes, the group gathered cash and online donations using Bitcoins, Monero, Dash and Verge cryptocurrencies (Jusi, Satrya, and Wardoyo Reference Jusi, Satrya and Wardoyo2019). The AAF used individual accounts in Indonesia to facilitate its financial activities. One of the suspects had financial links with terrorists in one of the Pacific countries. The AAF has been listed on the domestic terrorist lists in Indonesia (Badan Nasional Pennungulangan Terrorisme 2017).

The latest case probing the use of FinTech services for terrorist financing purposes involves Adi Ale Sapari. Adi’s networks pledged their allegiance to ISIS and planned to organize shooting and bomb-making training in West Java. To obtain the funds, Adi applied online for loans to five P2P lending companies, with details as follows:

-

(1) On 22 April 2019, Adi obtained IDR 9,420,000 from an online loan from DBS Bank.

-

(2) On 26 May 2019, Adi got IDR 570,000 from PT Kredit Pintar with the online program “KREDIT PINTAR”.

-

(3) On 26 May–17 June 2019, Adi secured IDR 2,930,000 from three loans provided by PT Kredit Utama Fintech Indonesia using the online program “RUPIAH CEPAT”.

-

(4) On 30 May 2019, Adi withdrew IDR 1,000,000 through an online loan program by PT Digital Kita under “TUNAI KITA”.

-

(5) On 26 May 2019, with the program “PINJAM YUK”, Adi also tried to apply for a loan of IDR 300,000, but the company rejected his application.

Besides the programs mentioned above, he also applied for other online loan brands and collected money from online lending activities up to IDR 16,190,000. Most of the funds were used to buy airsoft guns or weapons. The terrorist group also purchased ammunition from an online e-commerce platform.Footnote 3

Indonesian Regulations on FinTech

This section discusses the current policy environment that regulates terrorist-financing crime and formulates policies in FinTech services by Indonesian regulatory authorities: Bank Indonesia and OJK. Finally, the discussion on the policy environment also identifies some challenges in implementing countermeasures to mitigate further risks of terrorist financing in the application of FinTech services.

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

The Indonesian Government adopted FATF recommendations at the country level by formulating a new Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Law No. 15 of 2002 to criminalize money laundering for the first time. Afterwards, the Law was amended with the AML Law No. 25 of 2003 and the AML Law No. 8 of 2010. The AML Law regulates terrorist financing as a predicate offence to money laundering crimes. Stakeholders should report any suspicious transactions related to the financing of terrorism. The AML Law defines terrorist financing as “assets which are recognised or which are reasonably alleged to be directly or indirectly used for the terrorist activity, terrorist organisation, or individual terrorism”.

Bank Indonesia

Bank Indonesia launched a regulation on financial technology known as FinTech Regulation Number 19/12/PBI/2017 regarding the Provision of Financial Technology, dated 30 November 2017 (“Reg. 19/2017”). Bank Indonesia regulates the implementation of FinTech to encourage innovations in the financial sector by applying the consumer protection principle, risk management principle and prudential principle to maintain monetary stability, financial system stability and efficient, smooth, secure and reliable payment systems.

Bank Indonesia has also defined sanctions for both FinTech and payment system providers that had failed to register their business by 30 June 2018.

These sanctions are levied on the unregistered FinTech provider: (a) warning letter; (b) suspension of business activity; (c) other action concerning payment system activity; and (d) recommendation to the authority to revoke the business licence. In addition, the specific sanctions for the unregistered payment system provider consist of the following: (a) warning letter; (b) fine; (c) suspension of payment system service in part or whole; and (d) licence revocation as payment system provider.

If a payment system service provider has obtained a licence from Bank Indonesia, then that provider is exempted from the obligation of registering with Bank Indonesia. However, the payment system service provider will still have to submit information to Bank Indonesia on a new product, service, technology, and business model which meets the Financial Technology criteria.

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK, Indonesia’s Financial Regulation Authority)

The OJK fully implemented five strategies to support digital financial innovations in Indonesia:

-

(1) Holistic and balance strategy. The OJK ensures the resiliency, safety and soundness of FinTech and promotes innovation and competition. FinTech companies must ensure customer protection in their business to create and maintain trust in the industry.

-

(2) Agile regulatory framework. The OJK sets principle-based regulations for digital financial innovation while acknowledging that the FinTech industry is evolving rapidly. It gives the industry the flexibility and responsibility to define codes of conduct and operating standards that fit with their business.

-

(3) Market conduct supervision. The OJK is accountable for the regulation and supervision of FinTech. Meanwhile, FinTech is responsible for managing its business by applying sound corporate governance, risk management and compliance. The OJK appointed a FinTech Association to oversee FinTech development.

-

(4) Regulatory sandbox. A regulatory sandbox is the OJK testing mechanism to assess the reliability of the business process, business model, financial instruments and the governance of the innovator based on the specific predefined criteria. The regulatory sandbox allows the OJK to gain a deeper understanding of FinTech business models and risks and also allows FinTech firms to improve their business models and governance (Table 2).

Table 2. FinTech Regulation in Indonesia (Kharisma Reference Kharisma2020)

-

(5) Digital innovation. The OJK nurtures innovation and responsible finance through the establishment of the OJK FinTech Centre, named “OJK Infinity” – “OJK Innovation Centre for Digital Financial Technology” launched on 20 August 2018. The OJK Infinity carries out three responsibilities: a FinTech learning and innovation centre, a media centre for carrying out group events and sending out positive developments among critical stakeholders, and as a laboratory for regulatory sandboxing.

Prevention and Suppression of Terrorist Financing Law

In 2013, the Indonesian Government enacted a special law on terrorist financing, Law No. 9 of 2013, concerning the Prevention and Suppression of Terrorist Financing Law (Countering the Financing of Terrorism or CFT Law). The CFT Law stipulates terrorist financing as:

assets of every kind, whether tangible or intangible, moveable, or immovable, however, acquired, and legal documents or instruments in any form, including electronic or digital, evidencing title to, or interest in, such form, including, but not limited to, bank credits, traveller’s cheques, bank cheques, money orders, shares, securities, bonds, drafts, letters of credit.

The CFT Law regulates five significant aspects of preventing and suppressing terrorist financing. First, the Law offers parameters for convicting direct and indirect terrorist financing activities conducted by individuals and organizations. The second aspect is setting up an anti-terrorist financing policy system that involves the FIU and financial service providers (FSPs). The system covers regulations in applying the Know Your Customer (KYC) and the Customer Due Diligence policies and the monitoring and controlling mechanism of FSPs and money remittance companies. Third, the Law also controls the cross-border cash-carrying reports for FIU and Customs.

Furthermore, the CFT Law formulates crime investigation and prosecution procedures, freezing assets mechanisms, and best practices of freezing without delay assets referred to in the United Nations Resolutions 1267 and 1373. Finally, the Law leverages national and international cooperation in preventing and combating the financing of terrorism. In the area of mitigating risks of terrorist financing in FinTech services in Indonesia, the Central Bank, Financial Service Authorities and the Commodity Futures Trading Supervisory Body are three prominent government agencies generating regulations and supervising FinTech companies.

Based on the regulation map, three groups of FinTech industries are operating in Indonesia (Andriariza and Agustina Reference Andriariza and Agustina2020):

-

(a) Payment systems that include non-cash payments attached to commercial merchants (e-money) – for example, OVO, GoPay, DANA and LinkAja.

-

(b) Indonesian lending companies, which consist of the following:

-

P2P lending services that connect lenders and borrowers like, for example, Modalku, Investree, Amartha and KoinWorks.

-

Balance sheet lending platforms that offer direct loans from their capital. For example, UangTeman, JULO, TunaiKita and Doctor Rupiah.

-

Online credit platforms, for example, Akulaku, Kredivo and Cicil.

-

Online credit using pawn systems, for example, Pinjam.

-

-

(c) Other FinTech innovations which offer financial services and are excluded from payment and lending platforms are called crowdfunding for social activities, social services, health and digital banking. Several examples include Kitabisa.com, Jenius by BTPN and Digibank by DBS Bank. Some Indonesian conventional banks have also developed their financial services into digital banking services.

POLICY GAPS

This study analyses the applications of FinTech in Indonesia by examining the characteristics of FinTech that pose risks and challenges to the country’s existing policies. As of now, Indonesia does not have a robust regulatory framework specifically for FinTech. Notwithstanding that banking, capital market and insurance industries are provisioned under specific laws, FinTech has only been regulated by policies generated by the Central Bank and OJK. This means that there is a legal vacuum surrounding the FinTech industry. Based on document studies, there are three primary concerns in applying FinTech services in Indonesia. The first concern is consumer protection policies, including a strategy to protect consumer funds from criminal activities, like fraud and other illegal practices. The second concern is data security policies. Protecting customers’ data is crucial to utilizing a digital banking system. Therefore, following this, there is a policy gap in the existing FinTech regulations in Indonesia. The legal aspects regulated by the OJK and Central Bank could not include criminal provisions because they are not a law. This has an impact on the establishment of a robust countermeasure in preventing and mitigating the risks of FinTech being abused by criminals. Illegal activities like fraud, hacking, cybercrime and personal data thefts, considered criminal actions, could not be legally dealt with under such regulations.

In addition, the European Union (EU)–ASEAN Experts Roundtable discussion on 26 August 2021 identified three strategic issues in implementing the CFT policies on FinTech services in Indonesia. First, experts from financial regulators and law enforcement agencies in Indonesia and the Philippines acknowledged that FinTech policies in both countries are sufficient to disrupt terrorism funding. The regulations cover provisions on establishing and registering FinTech companies and applying compliance with AML/CFT regimes enforced by the FIUs. However, there is a significant concern about the lack of policy implementation. Second, experts identified challenges posed by applying FinTech in digital payment systems. These include optimizing regulatory technology to address FinTech and terrorist financing risks and strategies to address the use of fake identities in FinTech best practices, including blockchain technologies. Another challenge is in the newly developed products in FinTech, such as the use of e-commerce, digital wallets or startup companies that are modified to FinTech channels. Adding regulatory reform regarding information technology is needed, particularly in mitigating the potential misuse and abuse of personal data.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

There are four areas of concern that have an impact on the FinTech sector. First, Indonesia lacks a precise regulation of the cybersecurity ecosystem. For example, cyber-attacks in Indonesia for the first quarter of 2022 reached 11.8 million. Indonesia’s National Cyber and Crypto Agency (BSSN) identified 1.6 billion “traffic anomalies” in 2022. Approximately 62% of the “anomalies” were attributed to malware, followed by trojan activity and phishing attempts (INTERPOL 2021).

Second, the existing government regulatory policies fail to define personal data classifications. Without these clear and narrow definitions, the Government will be unable to set penalties for data security violations. Establishing preventative measures has a limited scope. For example, Law No. 11 of 2008 on Electronic Information and Transactions and its 2016 Amendment prioritize consent and empower the netizens to petition a court to order a web host to remove their personal data. It also authorizes the Government to terminate online connectivity for any site hosting information that violates Indonesian laws or morals. Moreover, the Law is unclear on which agency would be responsible for preventing or responding to specific violations, thus, leaving individuals without any means of recourse.

Third, the government agencies have overlapping and fragmented regulations in the financial sector. These weak regulatory systems may harm the FinTech sector, which handles voluminous payments and lending services transactions. For example, Bank Indonesia is responsible for data protection in the banking and finance sector. The BSSN supervises the monitoring of cybersecurity intelligence and cybercrime. The Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Kominfo) is tasked to work with law enforcement to surveil and investigate cybercrimes. This autonomous set-up between these government agencies hampers the central Government’s capacity to address, coordinate and craft strategies to respond and react to cybersecurity threats. Since financial crime and terrorist financing are cross-border crimes, there is a need for a well-coordinated effort among these three agencies. Moreover, since each agency has different priorities and approaches to cyber threats, they must agree on strategies to strengthen the overall cybersecurity structure.

Fourth, Indonesia is a linguistically diverse country. There are over 800 languages spoken in Indonesia, according to the 2010 census. Soosai Raj et al. (Reference Soosai Raj, Kasama Ketsuriyonk and Halverson2018) have demonstrated that multilingual countries like India and Indonesia will benefit significantly by establishing coding dojos that, for teaching programming, use both English and the most widely used local languages, which, in the case of Indonesia, are Bahasa Indonesia and Jawa. It is important to note that while computer languages, in theory, are more or less agnostic to the native human languages of whoever is using them, programming languages are not just a tool for communicating with the computer. Even though the primary goal of programming languages is to design tools for communicating with the computer; there is another goal that is as important if not arguably even more important: the fact that languages are meant to communicate with other human beings a few months down the line. Therefore, unless the programming team behind local cybersecurity all speak the same language, it is extremely important that the code communicates very well and takes into complete account all cultural nuances.

In programming, choosing the proper function names is extremely important. Thus if, for example, one is programming in English and one’s command of the said language is limited, it will not be easy for English-speaking programmers to read one’s code. Likewise, suppose cybersecurity analysis of Indonesian websites and applications relies on foreign cybersecurity experts who are not proficient in the local languages. In that case, there is a massive gap in timely and credible assessment and monitoring of illicit use of FinTech. This problem has been plaguing the programming industry for several decades. Acknowledging the problems and challenges in the programming industry concerning the native languages of programmers is essential to formulating effective long-term solutions to resolve the lack of cybersecurity and countering terrorism financing awareness at both the local and national levels of governance.

Cities in Indonesia and worldwide are constantly at risk of cyber-attacks and various other threats. From hijacking device communications and tapping into security information to downloading citizens’ personal information and siphoning critical data, there are various ways hackers can take advantage of weak IT systems. Cyber-attacks are further complicated in countries rife with conflict and terrorism threats perpetrated by a lack of a unified command to monitor, analyse, investigate and prosecute terrorism financing.

Offences in the FinTech Sector

As technologies quickly change and become far more sophisticated, cyber-attacks and terrorism financing are also rapidly evolving. Since attacks by Indonesian terrorist groups are more complex and sophisticated, the Indonesian Government should invest in technical and policy solutions, ideally under a unified command.

Given the numerous challenges of Indonesian FinTech, this article will highlight these recommendations for advancing this sector.

POLICY DIRECTIONS

Clear Government Regulations

Indonesian regulators have to deal with multiple issues regarding the FinTech sector, all at the same time. Platform lending is just one among the rest of the services offered. The regulators are all concerned to make sure that their country takes advantage of the opportunities to improve the financial system implicit in FinTech, but they are all also concerned with making sure that the risks involved are understood and protected against. The Indonesian Government strives to achieve the following through FinTech: (1) puts forward several opportunities for making payments more efficiently; (2) facilitates the rapid matching of borrowers to lenders; (3) simplifies access to finance for SMEs; (4) safeguards customers from financial crime and counterterrorist financing; and (5) nurtures FinTech startups with certainty and stability in their business operations through clear rules, regulations and guidelines.

Streamline FinTech Standards Among Regulatory Authorities

Indonesia’s regulations in the FinTech sector have overlapping functions that waste taxpayers’ money. Thus, laws that foster cohesion and unity of standards within the FinTech industry need to be developed.

Stronger Cybersecurity Ecosystem that Supports FinTech

The persistence of cyber threats requires a more iron-clad cybersecurity system for the FinTech sector. Due to the increasing volume and value of FinTech transactions, the protection of their systems against imminent threats has to be seriously taken into account. Cybersecurity solutions can combine security protocols, ease of use and efficiency. Facial biometrics can prevent hackers from wreaking havoc on the FinTech sector.

Digital Know Your Customer Policies and Single Identity Number

One of the challenges faced by FinTech industries is building robust customer identification procedures for digital payment systems. By improving their FinTech applications, FSPs offer secure financial services.

This includes strategies to develop digital KYC policies and protect consumers’ data. The digital KYC policies should be able to identify and verify new customers’ information without face-to-face interactions. One of the critical components to enhancing FinTech companies’ ability to apply certain digital KYC policies is the connectivity with the government citizenship database. Therefore, implementing a single identity number (SIN) policy is highly significant to mitigate the risks of data leaking or being abused by criminals.

This also includes improving applying digital signatures and managing digital documents to optimize FinTech businesses.

It is recommended that the FinTech industry should utilize the SIN in all of its transactions. This policy will enhance transparency and prevent financial crime and fraud. The SIN stores a database associated with the identity of every citizen over the age of 17 years and married. The SIN is a unique number integrated into a citizen’s identity card. The SIN and identity cards will form a national population database that can be the only reference for various public service applications. The presence of a SIN will facilitate the implementation of biometric data that guarantees the uniqueness of one’s identity card ownership.

EU–ASEAN FinTech Collaboration

Since the onset of COVID-19, more banks in Asia have embarked on digital transformation either in-house or in partnership with existing FinTech companies. The banks’ initiatives in the digital space received favourable responses from the Government. It is estimated that there are more than 600 FinTech startups in the ASEAN region, with new companies emerging almost daily. When it comes to minimizing the risk of FinTech being used for terrorist purposes, government enforcement agencies are under-resourced and ill-equipped to handle the massive volume of alleged violations or reported suspicious transactions.

With its ambitious initiatives for regional financial integration, coupled with financial risks, new challenges and disruption, e.g. FinTech and artificial intelligence, ASEAN can learn from the EU’s experience, particularly regarding monitoring and surveillance systems. Putting these systems in place helps the FinTech sector to track the implementation progress and ensures financial stability while minimizing the risks of FinTech being exploited for terrorism financing. Though some commonalities are pronounced between the two regions, e.g. complex economic and social models and the goal to pursue stability-oriented economic and financial systems and open regionalism, the significant variance between the regions is the fundamental difference in organization and institutionalization. Robust EU–ASEAN FinTech cooperation can lead to high-level technical assistance from the EU to ASEAN member states to impact implementation strategies to minimize the risks of FinTech being used for terrorist purposes. There is also a need to harmonize digital regulations focusing on the FinTech sector across ASEAN economies and to establish clear digital payment regulations.

List of Abbreviations

- AAF

-

Abu Ahmed Foundation

- AML

-

Anti-money laundering

- ASEAN

-

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- CFT

-

Countering the Financing of Terrorism

- EU

-

European Union

- FATF

-

Financial Action Task Force

- FinTech

-

Financial technology

- FIU

-

Financial Intelligence Unit

- FSP

-

Financial service providers

- ISIL

-

Islamic State in the Levant

- ISIS

-

Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

- KYC

-

Know Your Customer

- OJK

-

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan

- P2P

-

Peer-to-peer

- SIN

-

Single identity number

- SMEs

-

Small- and medium-scale enterprises

- VoIP

-

Voice over Internet protocol

Amparo Pamela Fabe is a visiting fellow at the International Centre for Policing and Security, University of South Wales. She is an anti-money laundering and counterterrorist financing expert in Southeast Asia, focusing on financial technology and virtual assets. She is also a professor at the National Police College and a countering violent extremism expert for the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police. Ms Fabe trained at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

Joan Andrea Toledo is a well-known investigative journalist, resource speaker and expert in countering violent extremism, deradicalization and countering terrorism financing in Southeast Asia. She is the author of the best-selling non-fiction book, Crossing the Red Line: Unmasking Covert Communists. She is a co-author of other landmark works such as the Disruptive Innovations of the Duterte Presidency (2019), Communist Termites: Stories of How Communist Terrorists Destroy Religions and Families from Within (2020) and Narrative Warfare® 1: Inside the Mind of the General Who Cannot Be Defeated by Communist Terrorists (2021).

Sylvia Laksmi holds a PhD in Terrorist Financing, Strategic, and Defence Studies from the Australian National University. She is a member of the Expert Working Group, the NATO Building Integrity Programme, and The Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance.