1. Introduction

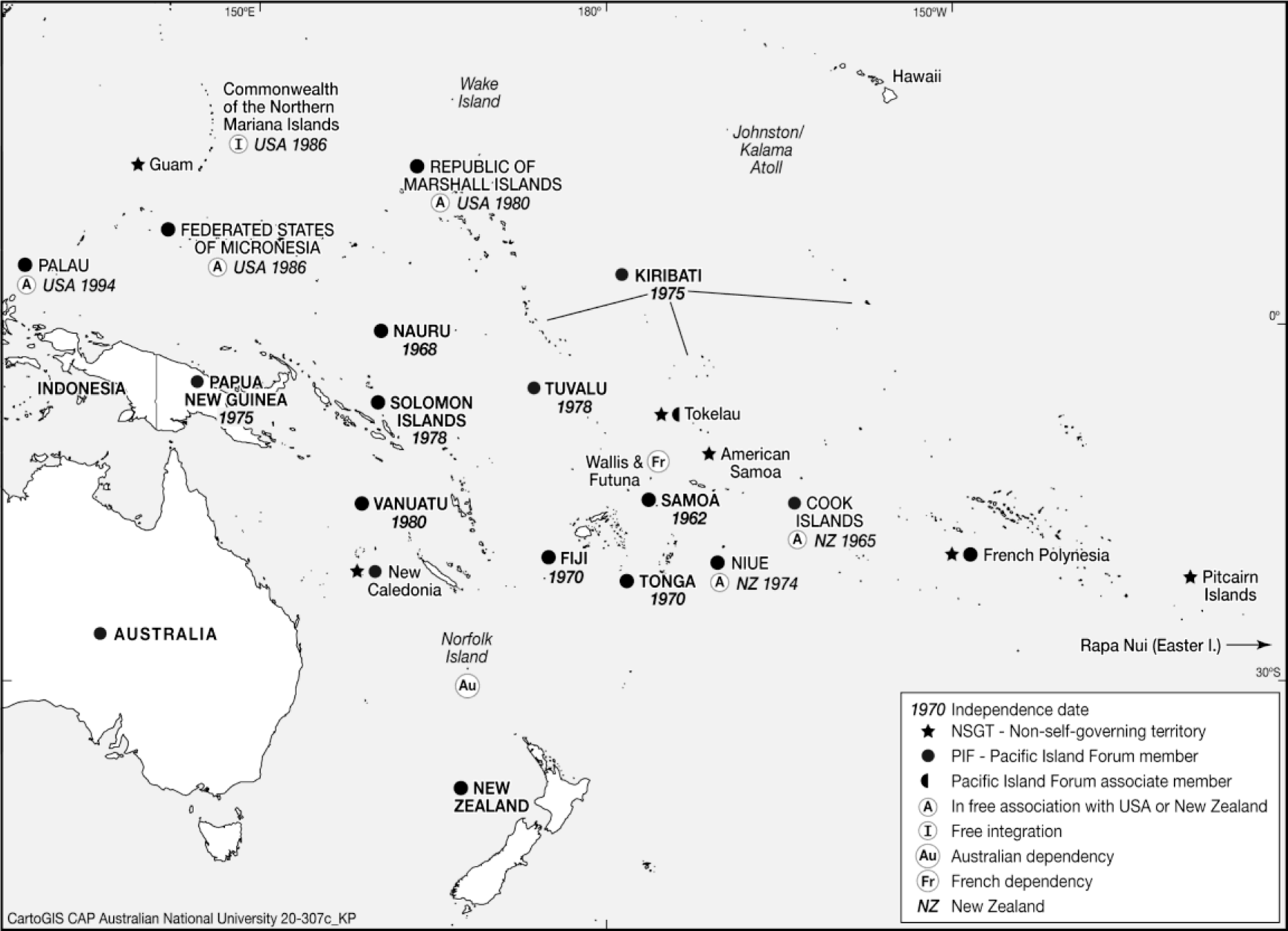

The ocean is prominent in all aspects of Pacific life and indeed the region calls itself the ‘ocean continent’ (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 Comprised of island states and non-self-governing territories (NSGTs), when discussion turns to territory, the issue today is often existential, with a focus on land territory’s disappearance as a result of climate change. What is less commonly analysed are the South Pacific’s territorial claims, including both active disputes and matters of relatively dormant disagreement, below the threshold of ‘dispute’ for the purposes of international law.Footnote 2 The region’s quiet and informal style of diplomacy and consensus-based decision-making – known as the ‘Pacific Way’ – might explain why trace of disagreement over territory between the Pacific Island CountriesFootnote 3 (PICs) can be difficult to find. In fact, the reason lies elsewhere: the region’s territorial differences overwhelmingly result from colonialism, pitting former colonies and current NSGTs against still present colonial powers. These territorial claims are, in other words, intertwined with matters of self-determination, a principle of great importance to the Pacific both historically and today as the process of decolonization continues. Self-determination is also invoked by those groups with post-independence secessionist claims of their own.

Figure 1. The Ocean Continent.

This article provides an overview of these legally varied sovereignty claims in the Pacific: secessionist claims, self-determination claims, and finally, territorial disagreements pitting NSGTs and former colonies against third party metropolitan powers. More specifically, understanding secession and self-determination in the Pacific is a necessary and appropriate backdrop to the region’s few – but legally interesting – territorial disputes and disagreements. One of the most active of these concerns Matthew and Hunter Islands, currently under negotiation between France and Vanuatu.

What emerges from the analysis is that Pacific practice in this domain is consistent with general international law; that there is also little disagreement between the states and territories of the region itself, whose shared values have instead given rise to innovative solutions to their legal problems: either through the leveraging of regional institutions – so vital to the region’s identity – to pursue their claims against metropolitan powers, or through innovative arrangements to alleviate problems left by colonial powers. Indeed, the region is replete with innovative legal solutions based on shared values and peaceful international relations. As such, Pacific practice and engagement with international law can provide a blueprint for others around the globe.

2. Explaining the relative lack of inter-state territorial disputes and the dominance of self-determination claims

Inter-state disagreements over territory in the Pacific are rare because, with few exceptions (to be considered below), the territorial integrity of the NSGTs was respected at independence and these territorial units in turn mostly aligned with geographic divisions and rarely cut across ethnic ones. The widespread maintenance by colonial powers of the pre-independence territorial integrity of their colonies is consistent with international law on self-determination (once that right emerged as positive law);Footnote 4 and on independence, with the principle of uti possidetis juris, as a means of orderly decolonization.Footnote 5 That said, after their independence some states in the Pacific faced secessionist claims. This is arguably because nationalism is generally considered weak, notably in Melanesia where the Pacific’s biggest population concentrations lie and where there is tremendous ethnic diversity. At the same time, in many other parts of the Pacific the struggle for independence from colonial authority itself remains a work in progress. Indeed, self-determination rather than nationalism is constitutive of identity and thus defines the region, its achievement expressed though membership of the region’s pre-eminent political institution, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF or Forum). It is against this broader background of secessionist and self-determination claims (considered in this Section 2) that today’s territorial disputes can be situated (Section 3 below).

2.1 The nature and fate of the region’s secessionist movements

The secessionist movements that exist both today and historically are mostly in Melanesia, in the western Pacific. As noted, this is not surprising given its ethnic and linguistic diversity. To illustrate, over 860 languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea (PNG). In Vanuatu, consisting of over 80 islands, over 100 languages are spoken. Today the two most prominent secessionist movements are in West Papua (consisting of the Indonesian provinces of West Papua and Papua) and Bougainville (in PNG). However, a particularly interesting case is in the east, in Polynesia, where an historic claim has been resolved with an innovative legal arrangement. This is the case of Banaba (Ocean Island), which lies in the Republic of Kiribati.

2.1.1 Current secessionist movements

The West Papuan and Bougainville secessionist movements both claim a right to independence on the basis of the right to self-determination. Conceptually however, the two claims differ. In the case of West Papua, the question is whether self-determination is extant despite UN approval of a self-determination process and the territory’s integration into Indonesia in the 1960s. In the case of Bougainville, even if cast in terms of self-determination, independence rests on PNG’s consent, pursuant to the procedures agreed to in a peace agreement between the parties,Footnote 6 PNG having exercised on behalf of Bougainville and the rest of the former colonial territory, its right to self-determination in 1975 when PNG became independent. The so-called ‘one shot’ (at independence) rule thus comes into play, which on a traditional analysis bars further legal entitlement to self-determination.Footnote 7

2.1.1.1 West Papua

The West Papuan secessionist struggle is taking place on the Indonesian side of the South Pacific’s only land border; a 750km divide between PNG and Indonesia on the island of New Guinea,Footnote 8 where illegal logging flourishes in the world’s third largest rainforest. West Papua, also variously known as West New Guinea, West Irian, Irian Jaya, and Western New Guinea, is Indonesia’s only Pacific Ocean controlled territory.

When Indonesia became independent in 1950, West New Guinea remained under Dutch rule, having been administratively severed from the Dutch East Indies (i.e., pre-independence Indonesia) in 1949 pursuant to a Charter of Transfer of Sovereignty.Footnote 9 According to the Indonesian interpretation of the 1949 Charter this separation was provisional, for one year only, whereas the Dutch interpreted the same instrument as providing for a permanent separation. Indonesian-Dutch tensions persisted from 1949–1962 during which time the Dutch advocated almost any alternative to Indonesian sovereignty – whether it was through the creation of a Melanesian Federation or some sort of UN administration of West New Guinea. The US mediated an agreement between the parties in 1962 (the New York Agreement),Footnote 10 pursuant to which the UN created its first territorial administration, the UN Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA) and one of its earliest peacekeeping operations, the UN Security Force in West New Guinea (UNSF).Footnote 11 This ultimately saw the Dutch transition out of their position as a post-War Pacific power as jurisdiction over West New Guinea was in 1963 transferred to Indonesia. Still under the terms of the New York Agreement this transfer was to be followed by an ‘act of free choice’, to be organized by Indonesia before the end of 1969, in order to enable the Papuans to exercise their right to self-determination. A plebiscite was indeed conducted of ‘representative councils’ in Papua. Those supporting Papuan independence have maintained that this process was unfair. However, on 19 November 1969 the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 2504 (XXIV) noting that Indonesia had fulfilled its obligations to conduct a plebiscite under the New York Agreement. Thirty-four states abstained from the vote but none voted against.Footnote 12

The issue of self-determination is nonetheless still pursued and there is scope to claim that the situation between Indonesia and West Papua is not simply a matter of Indonesia’s domestic jurisdiction, but remains ‘in international relations’ with the right to self-determination yet to be exhausted.Footnote 13 This argument does, however, rest on the hypothesis that under international law in force at the time, the Dutch were legally within their rights in separating West New Guinea from Indonesia in 1949 (thus breaking up the colony’s territorial integrity and making West New Guinea a separate unit) and that the 1969 Indonesian plebiscite was indeed illegitimate as a matter of international law. It also assumes that the UN General Assembly’s approval of Indonesian integration of the territory is non-binding.

Being prior to the emergence in 1960 of the right of people to self-determination,Footnote 14 it is difficult to assert that the law of 1949 prevented the severance of West New Guinea from the rest of the Dutch East Indies. However, it is even harder to challenge the General Assembly’s 1969 approval of Indonesia’s conduct.Footnote 15 As the Court stated in the Chagos Advisory Opinion, the General Assembly has a ‘crucial role’ in respect of self-determination.Footnote 16 If one accepts that the discretion of the Assembly (with its subsidiary organ the Committee of 24), to characterize a group as a ‘people’ is constitutive of their right to self-determination, generating that right for a given group, then surely it follows that the Assembly must also be the arbiter, as representative of the international community, of whether that right has been lawfully exercised. Despite the recommendatory nature of its resolutions, the authority of the Assembly to make legally binding determinations under general international law in respect of self-determination matters is well established. As the ICJ stated in the Namibia case which bore on self-determination:

… it would not be correct to assume, that because the General Assembly is in principle vested with recommendatory powers, it is debarred from adopting, in specific cases within the framework of its competence, resolutions which make determinations or have operative design.Footnote 17

As the Namibia case reveals and indeed, as has more recently been affirmed by the ICJ,Footnote 18 the Assembly’s decision-making power on self-determination also clearly extends to decisions made in the exercise of an oversight function.Footnote 19 This is well established. In the Pacific, the General Assembly has for instance, authoritatively asserted that it did not consider France’s 1987 referendum on New Caledonia to be valid and called for a free and authentic act of self-determination.Footnote 20 Thus, in relation to West Papua and Resolution 2504, the key to any challenge is whether the Assembly’s exercise of discretion in making its determination can be contested – and not whether the referendum was flawed in the eyes of others, something which is generally conceded.Footnote 21 The Assembly could of course decide to pass another resolution and list West Papua as an NSGT, but failing that, Resolution 2504 must arguably be challenged in order for a West Papuan right to self-determination to succeed.

The legal frame for assessing the Assembly’s exercise of its discretion is whether ‘the General Assembly acted within the framework of the Charter and within the scope of the functions assigned to it to oversee the application of the right of self-determination’.Footnote 22 The question does not turn on motives, but rather on interpretation, an objective exercise; specifically whether the Assembly’s decision was ‘reasonable in relation to the objectives of the relevant law’, in this case to the New York Agreement and the law of self-determinationFootnote 23 – which in respect of the latter, requires a ‘freely expressed will and desire’ of the people concerned.Footnote 24 Whilst the Court bypassed the issue in the East Timor case when dealing with Portugal’s assertion that Security Council and General Assembly determinations were final on the issue of self-determination,Footnote 25 in the much earlier 1948 Admissions Advisory Opinion the Court indicated that the General Assembly could appreciate in a discretionary way the factual criteria of the rule in question (Article 4 UN Charter) so long as there was a reasonable connection between its decision and the rule, and the exercise of discretion was performed in good faith.Footnote 26 The same reasoning might apply here, although the assessment must bear in mind that the adoption of a resolution by an organ of the United Nations benefits from a presumption of legality.Footnote 27

That said, in the light of the Chagos Advisory Opinion, the fact that the former colonial territory of West New Guinea is not currently on the UN Committee for Decolonisation’s list of NSGTs does not definitively exclude the right to self-determination. It is also of some moment that in recent years, some Pacific states have called on Indonesia to give effect to a free Papuan vote on their independence whilst also calling for an end to human rights abuses.Footnote 28 In that regard, the World Court’s 2010 comment in the Kosovo Advisory Opinion that ‘remedial secession’ as a ground for self-determination in the event of egregious human rights abuses elicited ‘radically different views’Footnote 29 (suggesting by inference that the consistent state practice needed for a customary right did not exist) may or may not still hold today.

More broadly one can note that with the departure of the Dutch, any inter-state territorial dispute between Indonesia and PNG is absent despite kinship ties across the border. This is borne out at the local level. Although the Indonesia-PNG boundary has been delimited since 1895, with some more recent amendment,Footnote 30 the border remains porous with recording made of fugitive crossings by West Papuan separatists into PNG prompting occasional Indonesian military led law enforcement incursions into PNG in hot pursuit.Footnote 31 Indonesia has in the past denied that these pursuits occur.Footnote 32 Nonetheless, this issue does not appear to give rise to dispute between these two states today, and most pertinently here, no dispute exists in relation to the boundary itself.

2.1.1.2 Bougainville

Unlike Papua, Bougainville does not relate to a split cutting across land territory, the divide instead being more characteristic of the region and its disputes (few though these are): that of a split archipelago (see Figure 2). Here that occurs between the southern tip of PNG’s Autonomous Region of Bougainville on the one hand, and the Republic of Solomon Islands’ northern-most Shortland islands on the other. When Germany ceded the Northern Solomon Islands, consisting of a cluster of islands of the Solomon archipelago, to the British in 1899, it retained the most northerly islands of Bougainville (the biggest and richest island of the geographic chain), together with Buka Island. This meant that after time as part of the Australian administered Mandate and later Trust Territory of New Guinea, these islands would ultimately become part of PNG. Today’s Autonomous Region of Bougainville still seeks independence from PNG, having fought a bloody conflict from 1988–1997 that only ended with PNG’s agreement to allow a Bougainville independence referendum.Footnote 33 That referendum, conducted between 23 November and 7 December 2019, resulted in an overwhelming vote for independence. This will, in the first instance, lead to consultations between the Autonomous Bougainville Government and the PNG government. Despite being part of the Solomon archipelago in a geographic sense, it is significant that Bougainville is not seeking integration with the Republic of Solomon Islands.

Figure 2. Secessionist Claims.

It can be seen that as in the case of West Papua, the issue here is a secessionist movement and the exercise of a claimed right to self-determination. No apparent dispute exists between the states of PNG and Solomon Islands in relation to the territory in question – even if tensions existed between them in the early to mid-1990s when PNG Defence Forces occasionally entered Solomon Islands territory as it sought to quell the Bougainville rebellion.Footnote 34

2.1.2 Historical secessionist movements and the respect for territorial integrity

As noted above the lack of inter-state disagreement over territory can be explained in political terms both by weak nationalism and a fortunate geographic situation where natural divisions tend to correlate with ethnic ones. In legal terms, the rationale lies in the region’s respect for the colonial unit’s territorial integrity, which on independence converted to respect for the principle of uti possidetis juris. In so doing, one sees that the uti possidetis juris principle was in this region, as in Latin America and later Africa,Footnote 35 a matter of positive international law anchored in state practice since the 1960s when the South Pacific NSGTs began their journey to independence. This outcome was aided by the consistently held position adopted by UN organs – the Trusteeship Council and General Assembly – on self-determination and to that extent these principles could be considered quasi-legislated. The respect for territorial integrity of the colonial unit and its desire to carry it forward to independence is also seen on the ground both in Bougainville’s prior claims for independence but also in the region’s other historic secessionist claims (detailed below and summarily depicted in Figure 2).

2.1.2.1 Bougainville and other parts of PNG: Bougainville

The Bougainville conflict of 1988-97 was not the first attempt by Bougainville to gain independence. In 1969 the Napidakoe Navitu nationalist society sought a referendum to ask the Bougainville population whether they wished to remain a part of PNG; unite with the New Guinea Islands (Manus, New Britain and New Ireland); join the British Solomon Islands Protectorate (which gained independence in 1978); or become an independent state.Footnote 36 Whilst the request for a referendum was refused, the Napidakoe Navitu nonetheless went ahead with a vote in 1970, reporting an overwhelming vote for secessionFootnote 37 – which did not eventuate, the pre-independence boundaries of PNG being instead maintained.

In August 1975, just prior to PNG’s independence on 16 September 1975 (full internal self-governance having begun on 1 December 1973), the North Solomons Movement declared the independence of the ‘Republic of North Solomons’ to be effective 1 September 1975. The UN did not recognize the declaration despite the dispatch of a delegation to the UN to that end.Footnote 38 The General Assembly’s longstanding views on the matter, later reiterated in respect of Bougainville before the Trusteeship Council, favoured the future PNG’s territorial integrity, and these affirmed the:

imperative need to ensure that the national unity of Papua New Guinea was preserved and strongly endorsed the policies of the administering authority and of the Government of Papua New Guinea aimed at discouraging separatist movements and at promoting national unity.Footnote 39

The North Solomons Movement resiled from its declaration of independence shortly before PNG’s independence on 16 September 1975Footnote 40 and its leaders integrated into the new PNG government.Footnote 41

The Gazelle Peninsula of East New Britain Elsewhere in PNG, to the northwest of Bougainville in East New Britain, the Mataungan Association was a prominent PNG secessionist group.Footnote 42 As early as 1971 they called for self-government and told a visiting UN Mission that they wanted land issues resolved by the International Court of Justice.Footnote 43 However, like a number of other groups,Footnote 44 it has been suggested that the main aim was not secession from PNG, though the Mataungan Association used this as a threat to achieve its more localized ambitions of autonomy.Footnote 45 Also created on the Gazelle Peninsula, the Melanesian Independence Front (MIF) had earlier sought to create a new Melanesian federation. Established in 1968, the MIF – like the contemporaneous and equally short-lived Napidakoe Navitu movement noted above – sought to create a newly independent state called Melanesia bringing together the four New Guinea Districts of Manus, New Ireland, New Britain and Bougainville.Footnote 46 This movement is separate to the Dutch proposal for a Melanesian Federation noted above in relation to Papua (Western New Guinea) and would die out in 1969.

At this point one can note that these examples reveal that although nationalism is weak, there was some historic appetite for pan-Melanesian federation. Today the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), a sub-regional institutional arrangement, to some extent fulfils that purpose, albeit at an international level. As will be seen below in relation to the contemporary Matthew and Hunter dispute, the MSG can provide leverage for sub-state actors to prosecute their international claims, and so confer upon them a degree of international legal personality, circumventing the ‘veil’ constituted by the colonial power. As will be seen at the regional level the PIF plays the same role, as well as that of excluding others – notably colonial powers – from the region’s political processes.

Papua’s Besana Group Finally, of particular note is Papua’s Besena Group which resisted the unification of the Australian administered Trust Territory of New Guinea with the Australian colony of PapuaFootnote 47 and declared Papua to be an independent republic in March 1975 just before PNG independence. Historically, the Australian colony of Papua had been governed quite differently to the German colony and later League of Nations Mandate of New Guinea, leading to considerable economic disparities between the two territories. The two were nonetheless administratively joined by Australia in 1949 – despite protest from the UN General Assembly both of Australia’s behaviour in this case, but also in relation to the joint administration of other similar territories elsewhere.Footnote 48 In Papua’s case, as in all the preceding PNG examples, the principle of territorial integrity as a precept of the law of self-determination was respected.

2.1.2.2 The Solomon Islands’ Western Breakaway Movement

Whilst most of the region’s secessionist movements are found in PNG, the Solomon Islands, a state with over 70 linguistic groups, has experienced significant ethnic strife. Of particular note were the tensions on Guadalcanal from 1998 to 2003 (escalating to a non-international armed conflict by June 2000), pitting the Malaita and Guadalcanal ethnic groups against one another, and culminating in the deployment in 2003 of an Australian led peacekeeping mission known as the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI).Footnote 49

Of note here however is a rebellion by another group, the Western Breakaway Movement, in the Western Province which sought autonomy in 2000 whilst the Malaita-Guadalcanal conflict was underway.Footnote 50 This movement, which prior to the Solomon Islands’ independence in 1978 had by some accounts envisaged independence of its own (or at least separation from Malaita)Footnote 51 , in the late twentieth century merely sought greater autonomy.Footnote 52 It is revelatory of the political fragility of some of the Melanesian states. Indeed at this time other Solomon Islands provinces also sought greater autonomy, but with a view to transforming the Solomon Islands into a federation style republic rather than demanding full secession.Footnote 53

2.1.2.3 The New Hebrides’ secessionist movements

Just prior to its independence as the Republic of Vanuatu in 1980, the Condominium of New Hebrides experienced revolts on the islands of Espiritu Santo (Santo) – via the initially ‘indigenist’Footnote 54 Nagriamel movement – and Tanna in the south, via the Tafea movement. These had roots going back to the 1960s, with political crises marking the 1970s, including at least one attempted declaration of independence in 1975.Footnote 55 In the 1970s the Nagriamel movement’s character changed as alliances were formed with French settlers (the Mouvement autonome des Nouvelle-Hébrides) who aligned with French government interests in seeing a post-independent Vanuatu in the form of a confederation with close ties to New Caledonia and by extension, France.Footnote 56

In April 1980, three months prior to Ni-Van independence, the rebels in Santo declared the independence of the Vemarana State with the support of businessmen in New Caledonia, American businessmen who sought to create a tax haven, and unofficially, some of the New Hebrides’ French administrators.Footnote 57 They were supported by other northern groups seeking to join the Vemarana in a Federation of the Northern Islands which, it was hoped, would also be linked with the Tanna movement in the south of today’s Vanuatu. The rebels in Tanna also planned to secede but they never issued a declaration of independence.

Despite longstanding French reluctance, in June 1980 the British and French dispatched troops to quell the rebellions. As MacClancy points out ‘in true Condominium fashion, the metropolitan governments each [did so] independently (without informing the other of its decision)…’.Footnote 58 One month later, the South Pacific Forum (known since 2000 as the Pacific Islands Forum) admitted the New Hebrides – then on the eve of its independence – as a new Forum member and called on Britain and France to end the rebellion,Footnote 59 fearful that secessionist movements might be encouraged in other Forum island States.Footnote 60 Vanuatu would become independent on 30 July 1980 – the first of the French Pacific colonies and last of the UK’s to do so.Footnote 61 Prior to independence, on 14 July at the Forum’s Tarawa meeting, and at the behest of New Hebrides’ democratically elected local Chief Minister Walter Lini, and who would become post-independence Prime Minister, the New Hebrides invited the PNG Defence Force to dispatch troops (the Kumul Force) to the territory. Troops would arrive after independence on 18 August 1980 and quelled the Santo rebellion by the end of that month. This was the first international intervention by a Melanesian state onto the territory of another stateFootnote 62 – done here with Australian logistic and communications support.Footnote 63

The pre-emptive nature of this invitation (having been issued prior to independence), legitimized by the context in which it was made (a Forum meeting) is an interesting one for international law. One criterion for consent to the use of force is that it must be made by the lawful government and that means the state’s highest authority.Footnote 64 At the time of the consent to the otherwise prohibited force, was this Walter Lini? Did the existence of the Condominium make it unclear who else that might be? At the same time, one of the rules surrounding the right to self-determination is that the forcible struggle to enforce that right cannot entail third party forcible assistance. The implication is that the legitimacy conferred by the Forum on Walter Lini prior to independence, and the implementation or execution of this invitation post-independence made the operation lawful.

Although in this case unsuccessful, the New Hebrides’ Nagriamel movement, which ultimately defended French settler interests, has been likened to Mayotte,Footnote 65 which remained French despite the rest of the Comoros archipelago – and colonial unit – becoming independent in 1974. The UN General Assembly repeatedly condemned Mayotte’s separation from ComorosFootnote 66 and today that condemnation finds legal support in the ICJ’s 2019 Advisory Opinion on the analogous pre-independence separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius.

2.1.2.4 Banaba (Ocean Island)

Thus far all the historic instances of attempted secessions in the South Pacific have yielded the same result: since the emergence of the right to self-determination in the 1960s, primacy has always been given to the territorial integrity of the self-determination unit, even when the initial joining of two units – the case of Papua and New Guinea – was contested by the UN. The same primacy to territorial integrity is confirmed in the final example discussed below, but this situation is perhaps the most interesting since this confirmation of the principle of territorial integrity comes at the expense of a people’s connection to their territory.

The Polynesian island of Banaba or Ocean Island (Figure 1) was initially part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (GEIC). Following a pre-independence referendum held in December 1974, the GEIC divided into the independent states of Kiribati (considered part Micronesian, part Polynesian) and Tuvalu (considered Polynesian). After lengthy debate, Banaba remained part of Kiribati. It is however quite distinct. Geographically it resembles (the relatively proximate) Nauru with large phosphate deposits that were mined by the British since the early 1900s.Footnote 67 Following Japanese occupation of the island during the Second World War, and to enable further exploitation of the island’s lucrative resources, in 1942 the British purchased, and then in 1945 relocated Banaba’s population to, the Fijian island of Rabi. Banaban descendants are today Fijian citizens, but the island and its inhabitants are governed by the Banaban Rabi Council of Leaders. Whilst the Banabans have ownership of most of Rabi, the island remains subject to Fijian sovereigntyFootnote 68 and the fact that it is an integral part of Fiji has never been doubted. That said, despite Banabans not being Kiribati citizens, the Rabi Council of Leaders sends Banaban representation to the Kiribati parliament.Footnote 69 This innovative arrangement is protected by the I-Kiribati Constitution and attaches rights to the descendants of the ‘former indigenous inhabitants of Banaba’.Footnote 70 As will be seen, indigenous connections are particularly important in all parts of the Pacific and in this instance one can see how the region’s newly independent states found an original solution to respect their cultural ties and to share their institutions as a means of doing so.

Significantly, in 1965 – and so prior to the breakup of the GEIC – Banaba argued for its own independence. The UK countered this in the UN by arguing in favour of the territorial integrity of the colonyFootnote 71 (in the same year that the British severed the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius).Footnote 72 Indeed, Fiji would take up the same argument claiming it would not tolerate any severance of its territory,Footnote 73 although the Banabans were not seeking secession of Rabi from Fiji, but rather of Ocean Island from Kiribati. The UN Committee of 24 did not support the Banaban case for independence but directed the UK to find a solution that would give Banaba control over its natural resources.Footnote 74 Whilst consideration was given to Banaban arguments in favour of the free association of Ocean Island with Kiribati, ultimately the island remained within the new state – subject nonetheless as a matter of its domestic constitutional law to the representation rights of Banabans.

Reports indicate that some Banabans would today like to return to Banaba.Footnote 75 In this regard it is material that the initial population transfer to Rabi occurred at the end of the Second World War and so before any right to self-determination for NSGTs arose. Even were self-determination found to have been denied in this case, it is interesting that the ICJ has recently asserted that any resettlement issues would be a matter of human rights law.Footnote 76 The interim conclusion in this regard is that territory more so than people appear to characterize the right to self-determination for the purposes of international law – perhaps a banal observation given the equal importance that states attach to territory.

2.2 Self-determination as constitutive of the region

There are multiple instances in the South Pacific where an established right to self-determination remains to be fulfilled. The UN’s list of NSGTs, contains a large number of South Pacific territories – of the 17 current NSGTs, six are in the Pacific,Footnote 77 just behind the Caribbean, which has seven.Footnote 78 Indeed this list might increase as today Australia’s Pacific Ocean dependency of Norfolk Island (which since 1856 houses a large number of Pitcairn Island descendants) has petitioned the UN’ Special Committee on Decolonization for listing as a NSGT following Canberra’s withdrawal of the island’s autonomy in 2016.Footnote 79 In the past Australia has strenuously resisted any such attempts.Footnote 80

Today New Caledonia is prominent amongst the UN list: after a long struggle two independence referendums were held but failed in 2018 and 2020 respectively with one more to be held, probably in 2022. New Caledonia had been reinstated on the UN list of NSGTs in 1986Footnote 81 (having been absent from it since 1947)Footnote 82 at the request of Australia and New Zealand along with the PICs. It is an interesting case, though not unusual in the region, because it involves not only the self-determination of a people within the meaning of General Assembly Resolution 1514 (1960), but also one to be exercised by an indigenous people.Footnote 83 Indeed, most if not all Pacific NSGTs have large indigenous populations within the scope of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples:Footnote 84 French Polynesia (whose listing as a NSGT in 2013 is staunchly opposed by France), Guam, American Samoa, Tokelau – and indeed not on that list though aspiring to be there, the Papuans in West Papua.

As noted, a colonially dominated people can enjoy a right to self-determination even if they are not on the UN’s list of NSGTs and there are several such candidates in the Pacific. An interesting case is Hawaii which is culturally and geographically part of the region (but as will be seen, not so politically). Hawaii was removed from the UN’s list of NSGTs following a 1959 referendum and the territory’s accession to the status of a state in the US union. However, scope for reopening the matter – at least as an in-principle proposition under international law – arose in 1993 when the US Congress adopted a resolution recognizing the illegality of both the 1893 de facto annexation of Hawaii (contrary to treaties then in force and undertaken without Washington’s approval), as well as the later official 1898 US annexation of the kingdomFootnote 85 when Hawaii ‘ceded’ sovereignty to the US.Footnote 86 The 1993 ResolutionFootnote 87 consists of two substantive paragraphs. The first contains an ‘acknowledgement and apology’ for these events, although the US Supreme Court has interpreted this to be ‘conciliatory and precatory’ and not creative of substantive rights; the resolution’s second paragraph then stipulating: ‘Nothing in this Joint Resolution is intended to serve as a settlement of any claims against the United States.’Footnote 88 The US Supreme Court has interpreted this provision as a disclaimer.Footnote 89 The Resolution nonetheless calls for reconciliation and whilst Hawaii’s indigenous population is divided on how this is to be pursued, some favour sovereignty.Footnote 90 It must be recognized that this population is small – and it is perhaps for that reason (as well as the argument that the right to self-determination was exhausted in 1959), that the principal debate centres on indigenous rights, rather than that of independence and a restoration of de jure sovereignty.

Not only do the New Caledonian and Hawaiian situations illustrate both the imbrication of indigenous rights with that of self-determination in the region but also, how the Pacific as a region is constructed politically. Hawaii is not generally considered a political member of the Pacific, a status reserved for those entities having exercised their right to self-determination and who choose independence from, rather than integration with, the colonial power.Footnote 91 Admission to the PIF attests to this achievement. That said, the Forum admits entities who enter into free association with other states.Footnote 92 Significantly, it has been quick to admit NSGTs prior to full statehood, but whose independence as a result of the self-determination process is imminent. Thus, PNG was admitted in 1974 – after full internal self-governance in December 1973 and just before independence in September 1975. As noted above the New Hebrides was admitted on the eve of its independence. New Caledonia, together with French Polynesia, currently in the midst of the self-determination processes were (perhaps prematurely) admitted to the Forum in 2018.

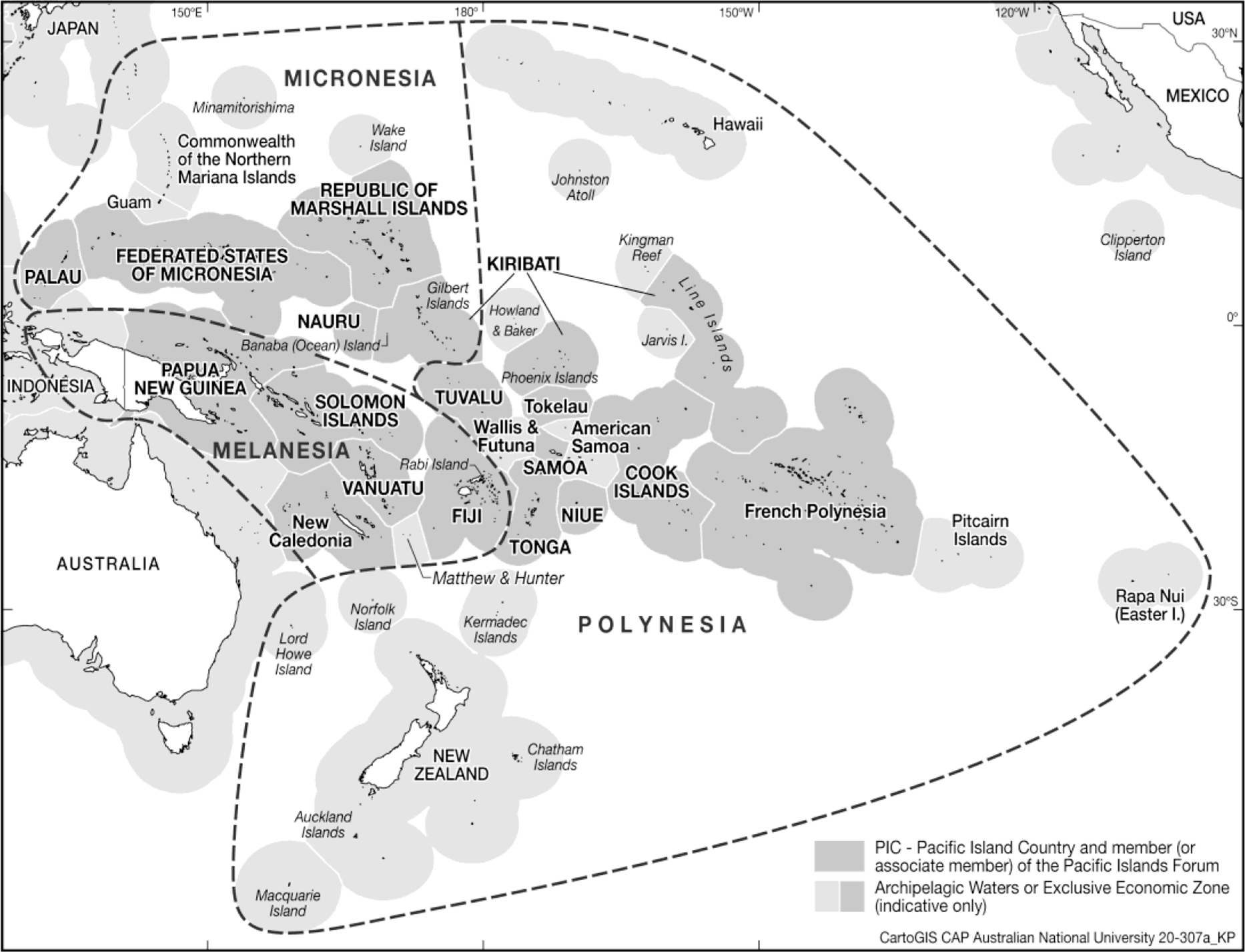

In this way, since the early 1970s, as decolonization progressed, self-determination has come to frame the South Pacific, its exercise determining the region’s legitimate representatives and thus the place of each territorial entity within or outside the region as a political community, the latter personified by the PIF.Footnote 93 Unlike the region’s other principal organization, the South Pacific Commission (now the Pacific Community), created by the colonial powers in 1947 to co-ordinate social and economic activities apolitically, the PIF was created by the newly independent states as the pre-eminent political arrangement. It excluded and continues to exclude those territories that are yet to exercise their right to self-determination, just as it excludes from membership the colonial powers – with the exception of New Zealand (more clearly a Pacific nation) and Australia (perhaps in some respects a Pacific nation). And it is in fact, the failure to liquidate colonial situations that gives rise to the current legal issues over the status of territory.

3. Current international territorial disputes and disagreements

Today, two types of territorial disagreement exist in the Pacific ‘in international relations’ within the meaning of international law – and thus of international concern rather than domestic jurisdiction. On the one hand are the disputes between independent PICs, which are exceptionally rare, and on the other, claims by NSGTs against colonial powers (Tokelau re Swains) as well as by those states in free association with the other claimant and thus where there is a situation of some de facto dependency (Marshall Islands re Wake).

Of the inter-state claims, one can note that as between the PICs themselves, both Fiji and Tonga claim Minerva Reef which appears to lie in Fiji’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). However Minerva Reef is fully submerged at high tide, and so is not capable of being reduced to sovereignty according to recent judicial pronouncements.Footnote 94 Few, if any, other disputes exist between the PICs today although Vanuatu and Fiji have recorded disagreement over Vanuatu’s dispute with France over Matthew and Hunter islands. That dispute brings into play the geography of archipelagos, self-determination and indigenous rights.

3.1 Matthew (Umaenupne) and Hunter (Leka) Islands

France (for New Caledonia) and Vanuatu both claim sovereignty over the Matthew and Hunter Islands, two very small volcanic outcrops at the southern tip of the Vanuatu archipelago. Prior to its independence, the Condominium of New Hebrides was a joint colonial protectorate, with a legal personality distinct from both Great Britain and France individually, although France and the UK each retained jurisdiction over their own nationals.Footnote 95

On both sides of the Hunter and Matthew disagreement, the precise grounds for the claim to title have not been clearly assertedFootnote 96 and the matter is currently under negotiation. France generally asserts that the two islands had ‘always been an integral part of New Caledonia’Footnote 97 – and so presumably since 1853 when New Caledonia and her (undefined) ‘dependencies’ were annexed by France. The New Hebrides being, at the time, clearly excluded from the category of New Caledonian dependency, Matthew and Hunter might also be excluded on this basis. Other accounts of the French position hold that France annexed the islands in 1929.Footnote 98 Most French accounts also refer to a 1965 decision of the New Hebrides’ Joint CourtFootnote 99 which purportedly confirmed Hunter and Matthew’s legal attachment to New Caledonia;Footnote 100 a position reiterated by France and (according to France) by the UK, immediately after Vanuatu’s independence when that position was contested by the then newly independent state’s Prime Minister, Walter Lini.Footnote 101

Vanuatu’s argument in support of its claim to sovereignty, whilst resting on title as successor state to the New Hebrides – and thus requiring demonstration of a prior title vested in the CondominiumFootnote 102 – is otherwise also unclear. It does not appear to rest solely on contiguity, not in itself a root of titleFootnote 103 unless it can be shown that these tiny islands are mere dependencies.Footnote 104 The difficulty for both Vanuatu and France in this regard is that although geographically forming part of the Ni-Vanuatu archipelago, the islands may be located closer to New Caledonia’s Walpole Island than to Vanuatu’s southern island of Anatom.Footnote 105 With no clear indication that the islands are dependencies the argument for title arguably lies elsewhere,Footnote 106 bearing in mind that whilst ‘proximity as such is not necessarily determinative of legal title’,Footnote 107 it may give rise to a presumption.Footnote 108 One argument favouring Ni-Vanuatu sovereignty can be derived by inference from the French position. As the French have phrased it – and as would appear from the written answers given to questions in the French Parliament in 1983 – Vanuatu’s claim is that an agreement was struck between France and the British by which France ceded the islands to the New Hebrides.Footnote 109 This line of argument emerges because the French records deny that any act of cession occurred. Another line of argument for Vanuatu is that ‘[i]n 1965 the United Kingdom occupied the two islands which were attached to the Condominium of New Hebrides’.Footnote 110 The author of this argument does not elaborate. What is clear is that Vanuatu’s southern indigenous groups have longstanding customary attachments to these two islands, something conceded in French official statementsFootnote 111 and recorded in the literature.Footnote 112

Since the adoption of UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the creation of the EEZ, small islands such as Hunter and Matthew, which adorn the Pacific Ocean, have of course taken on heightened importance. Not surprisingly, France, well aware of Vanuatu’s claim since at least 1980, has delimited its baselines on the assumption that Hunter and Matthew are French. Whilst these two outcrops are clearly above water at high tide and are therefore islands within the meaning of Article 121 of UNCLOS,Footnote 113 France has claimed an EEZ on the assumption that Hunter and Matthew are capable of sustaining human or economic life of their own. The combined claimed EEZ is 190,000 km2 Footnote 114 (indicatively shown on Figure 1), underscoring the great interest to states in laying claim to these micro territories. Interestingly, were Vanuatu sovereign over the two islands, they would form part of the Vanuatu archipelago and so could benefit from archipelagic baselines, thus obviating the need to demonstrate that the islands are capable of sustaining life within the meaning of Article 121 UNCLOS.Footnote 115

The delimitation process undertaken by France and Vanuatu of their maritime boundaries in the area reveals a series of public acts in respect of their respective claims to the islands. These acts have clearly arisen after the crystallization of the dispute which arguably occurred on Ni-Van independence in 1980 (as noted), but they reveal the existence of a dispute and its on-going nature. Between 2007 and 2012, claims by both parties to extended continental shelves directed the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf not to pronounce in respect of the islands.Footnote 116 Both parties have adopted legislation including the islands within their maritime boundariesFootnote 117 and have protested officially the other claimant’s domestic legislation.Footnote 118 France has always been quick to point out any failure by Vanuatu to protest French acts.Footnote 119 This includes Vanuatu’s failure to object when France deposited with the UN a 1983 Franco-Fijian treaty delimitating their EEZ and which establishes the limits of their maritime spaces to the east of Matthew and Hunter.Footnote 120 This general pattern of claim and counter-claim and indeed protest and counter-protest can in fact be traced to Vanuatu’s independence in 1980 when Prime Minister Walter Lini claimed the islands for the newly independent state, making it safe to assume that the dispute arose, at the latest, in 1980.Footnote 121

So, is there a basis to either state’s sovereignty claim? Pre-independence acts in respect of the islands do exist and as such can inform the analysis,Footnote 122 including notably the French annexation of 1929, if proven. As no record exists of agreements between the powers and local tribes in the New Hebrides,Footnote 123 the assumption must be made that there was no cession of territory but that the 1929 acquisition (if proven) was an occupation of a terra nullius. For the other side, Condominium acts in respect of the islands appear to be negligible. Moreover, events surrounding the New Hebrides Joint Court decision of 1965 appear to confirm French title.Footnote 124 Material held at the UK’s National Archives indicate that in 1965 two individuals approached the New Hebrides Joint Court to register title to the islands.Footnote 125 However, the French member of the Joint Court did not allow the case to be heard, claiming that it fell outside the Joint Court’s jurisdiction because the islands were New Caledonian dependencies (thus alluding to France’s 1853 annexation noted above) and so the matter was removed from the court’s list.Footnote 126 In a letter from the UK’s Colonial Office to its Foreign Office the view was expressed that although the file relative to the islands could not be found, ‘they [the UK] were content with the assertion that Matthew and Hunter belonged to New Caledonia’.Footnote 127 Neither of these statements are, if made unilaterally, of any consequence: the Condominium was for France and the UK individually, a foreign entity.Footnote 128 Only a decision of the Condominium itself can have any legal bearing on the matter. Problematically however for Vanuatu, is a subsequent letter dated 22 November 1965 from the French and British Resident Commissioners – i.e., from the Condominium itself – confirming that the islands were New Caledonian dependencies.Footnote 129

One can note that this occurred against a backdrop of considerable uncertainty. A confidential note of 2 March 1965 records that just prior to the First World War, both France and the UK denied attachment of the islands to New Caledonia and the New Hebrides respectively.Footnote 130 Moreover, official correspondence relates that as late as 1962, maps variously showed the islands to be French (New Caledonian), New Hebridean, and even Australian.Footnote 131 This suggests that prior to 1962, although the islands were administered from the New Hebrides, there was, in light of the purported 1929 French act of annexation, doubt as to where sovereignty lay. It was only in 1976 that France transferred the administration of the islands to New Caledonia. Even if this transfer provides some potential indication of prior New Hebridean title, the Joint Commissioner’s concession in 1965 to accept France’s claim arguably relinquishes any claim to the islands that might have previously existed.Footnote 132 The inherent weakness in the condominium regime, which effectively allowed France, through a patent conflict of interest of the French appointed Resident Commissioner, to secure its own rights over those of the Condominium, effectively leads to the conclusion that on the evidence available today, France (on behalf of New Caledonia), rather than Vanuatu, has a stronger claim to sovereignty over the islands.

In his address to the 67th session of the UN General Assembly (2012), Vanuatu’s Prime Minister noted that negotiations had begun on the dispute between France and Vanuatu.Footnote 133 These appear to have already been underway in 2010.Footnote 134 In 2013, the new Prime Minister Kalosil reiterated the claim, putting it in the context of Vanuatu’s indigenous people’s close cultural affiliation with the islands.Footnote 135 These were the terms in which the matter was put:

Since our independence 33 year [sic] ago, the indigenous people of my country are still concerned that part of our maritime and cultural jurisdiction including Umaenupne (Mathew) and Leka (Hunter) Islands, south of Vanuatu were withheld by France. And in doing so, the people of our country were denied the right to exercise full political freedom and inherent cultural rights, preventing the indigenous people of the Southern Province of our country to fulfil and protect their cultural and traditional obligations in connecting its people to their land, sovereign since time immemorial.

These two islands are of paramount importance because they form the basis of the establishment of our unique cultural framework connecting our cultural island group known as Tafea islands. It is this cultural framework that had governed and defined who we are and our livelihood long before the administrative colonial powers began to explore and govern our shores. Sadly, today, our indigenous people continue to be denied access to these cultural and sacred Islands.

My Government calls upon the Community of Nations in this assembly to uphold the principles of respect on the rights of our indigenous people and their livelihood and for the Government of France to allow our indigenous people of Tafea to have access to their forefathers land, Umaenupne and Leka Island, in the Republic of Vanuatu.Footnote 136

In 2014, Prime Minister Natuman addressed the General Assembly stating that the work of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya had brought the question of Hunter and Matthew to the attention of the Human Rights Council’s 21st Session and in 2012 the French had responded and expressed an openness to dialogue.Footnote 137 What the Prime Minister sought in this 2014 speech was to:

… allow our indigenous peoples to resume the rights to fully exercise their cultural and spiritual obligations in the two islands of Umaenupne (Mathew) and Leka (Hunter), and to revive the traditional routes of our ancestors in the Tafea province.Footnote 138

It would appear that the claim to sovereignty was not being pursued in that speech. Moreover, Vanuatu’s subsequent speeches to the General Assembly from 2015 (70th session) to 2018 (73rd session) make no mention of Matthew and Hunter. More recently press reports indicate otherwise.Footnote 139

Regardless of who is currently sovereign over Hunter and Matthew, in 2009 New Caledonia’s national liberation movement (NLM),Footnote 140 the Front de libération nationale kanak et socialiste (FLNKS), signed an agreement (the Kéamu Accord) with the FLNKS stipulating that it would restore the islands to Vanuatu once New Caledonia was independent.Footnote 141 The FLNKS reaffirmed their support for Vanuatu’s claim in 2019, citing the close cultural ties between the islands and Vanuatu. The 1998 Noumea Accord between the French and FLNKS stipulates that the territorial integrity of New Caledonia must be maintained.Footnote 142 This provision undoubtedly intends to prevent a Mayotte style situation where one part of the population prefers to remain attached to France, but it also commits France to maintaining New Caledonia’s territorial integrity, including Matthew and Hunter, should they prove to attach to New Caledonia. The Noumea Accord also stipulates that for the time being international relations are exclusively a matter for the French government: whilst New Caledonia has no autonomy in this sphere, it is nonetheless to be associated with the French state in the exercise of this function.Footnote 143

Both the Kéamu Accord and the Noumea Accord (which from the perspective of French law is seen as a ‘federating’ and so domestic law instrument)Footnote 144 raise interesting issues as to their status under international law given that New Caledonia is a NSGT with a right to self-determination, as well as the increasing recognition of indigenous rights over land as articulated in Article 26 of the 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 145 Article 26 affirms the fundamental connection between indigenous peoples and the lands that they have traditionally used or occupied. This means the matter is not purely domestic. Were Matthew and Hunter a New Caledonian dependency, the question arises: from the perspective of international (as opposed to French) law, who has the legal capacity to bind that territory – France or the FLNKS as the NLM? One is reminded here that an NLM can conclude certain treaties within the sphere of their competence,Footnote 146 such as cease-fire agreements, but that more generally their personality is limited.Footnote 147 The Tribunal in the Abyei arbitration found, for example, that neither a Comprehensive Peace Agreement nor an Arbitration Agreement between Sudan and the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement Army were treaties but rather were ‘agreements between the government of a sovereign State, on the one hand, and, on the other, a political party/movement, albeit one which those agreements recognize may – or may not – govern over a sovereign state in the near future’.Footnote 148 Moreover, NLMs are unable to conclude multilateral treaties. Arguably, however, legal personality can vary not only according to the entity itself, but also the region in which it operates.

In the Pacific, one can recall in respect of Vanuatu that in 1980 the incoming post-independence regime, during a transitional period but before independence, consented to the (post-independence) deployment of PNG troops in Vanuatu. In that case Chief Minister Walter Lini had been elected, which is not the case of the FLNKS which is one of several parties in a diverse New Caledonian Congress.Footnote 149 And if the FLNKS has a degree of international personality by virtue of its membership of the sub-regional institutional arrangement, the Melanesian Spearhead Group, New Caledonia has since 1999 been represented at the regional level – in the Forum – by the President of the Government of New Caledonia and this has always been by an anti-independence politician. Nonetheless, given the emphasis on the self-determination-territory nexus, the question remains whether the FLNKS – or some movement representative of New Caledonia rather than colonial France – have the right to determine the status of territory by virtue of international law directly. One view, which reconciles the situation, is that the people’s representative (traditionally the NLM) is sovereign over the colonial territory without necessarily having legal capacity internationally to exercise that sovereignty.Footnote 150 In the case at hand, this arguably means that France can speak but only on behalf of the New Caledonian people – and the MSG has identified the FLNKS in that regard. Thus, any arrangement reached pending New Caledonia’s full exercise of its right to self-determination is to be undertaken jointly which, happily, is what the Noumea Accord provides from the domestic law perspective. What this means is that arguably in relation to Hunter and Matthew, as a matter of international law, France should take into account the FLNKS’ views – including notably, that expressed in the Kéamu Accord.

A solution inspired from the Torres Strait on the Australia/PNG border, could be useful in resolving this dispute. It is one that respects the indigenous rights of those traditionally connected to the islands. Prior to PNG independence, the Australian state of Queensland had progressively extended its border northwards, ultimately coming very close to mainland PNG. As a result, on PNG independence in 1975, PNG and Australia had to negotiate sovereignty over certain islands and the establishment of maritime boundaries in an area close to the PNG mainland. In undertaking this task, an important consideration was the traditional way of life of the Torres Strait Islanders and adjacent coastal Papua New Guineans and consequently both freedom of movement and fishing rights were preserved in a ‘protected zone’ extending both north and south of the maritime boundary.Footnote 151 The zone encompasses the land, sea, airspace, seabed and subsoil of the designated area; it extends environmental protections; and also creates a Torres Strait Joint Advisory Council to assist in implementation.Footnote 152 Without wishing to revert to a solution approximating the condominium, this might nonetheless prove to be an effective solution, at least pending New Caledonia’s fulfilment of its right to self-determination.

Finally one can note that even though France has not ratified International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 relative to Indigenous Peoples in Independent Countries, the tribunal in the Abyei award noted that it ‘enshrines a positive duty on the part of states to safeguard the rights of peoples to their traditional land use’;Footnote 153 the tribunal concluding that as a matter of general principle and in the absence of agreement to the contrary, traditional rights have ‘usually been deemed to remain unaffected by any territorial delimitation’.Footnote 154 If this reflects customary international law, then even if France were sovereign over Matthew and Hunter and no arrangement could be made with Vanuatu, traditional owners have a right to their traditional land use.

3.2 Disputes involving NSGTs and states in free association

Two disagreements are prominent. One concerns the dispute between the Marshall Islands (a state freely associated with the US) and the US over sovereignty to Wake Island (Enen-kio). The other disagreement is between Tokelau, a NSGT and current New Zealand dependency, and the US in relation to Swains/Olohega, sometimes written as Olosenga, and which is currently administered by American Samoa, a US NSGT (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Self Determination in the South Pacific.

3.2.1 Wake Island (Enen-Kio)

Wake Island (Enen-Kio) is located north of the equator to the west of Hawaii.Footnote 155 The Republic of Marshall Islands considers itself sovereign over Enen-kio and has drawn maritime boundaries accordingly.Footnote 156 This island is currently claimed and administered by the US and is classed under US law as a territory that is ‘unincorporated’ (thus with no prospect of becoming a state in the Union) and ‘unorganised’ (and thus with no constitution or government of its own).Footnote 157

The Marshall Islands’ claim to Wake is that Spain ceded the island to Germany at the same time as – but not by virtue of – the conclusion of the Hispano-German Protocol of 17 December 1885.Footnote 158 That Protocol was concluded following Pope Leo XIII’s mediation of a disputeFootnote 159 between Germany and Spain relative to the neighbouring Caroline and Palaos (Pelew or Palau) islands. The Pope’s mediation attributed sovereignty over these islands to Spain on the basis of its occupation – there being no need at the time for this to be effectiveFootnote 160 – but noting the active presence of German traders (habilitated to exercise state functions and claim title on behalf of Germany) called on Spain to establish institutions of state in the area and accord German traders rights of access and establishment.Footnote 161

By expressly stipulating the co-ordinates of the Caroline and Palaos islands, the mediation and subsequent Hispano-German Protocol of 1885, establish that Wake Island (19N and 166E) lies just to the east of the Carolines and Palaos and so within the geographic area of the Marshall Islands. Germany was at the time active over the Marshall Islands and would, in 1885 – one month after the Pope’s mediation – declare it a protectorate (all German colonies were termed ‘protectorate’, which is misleading since acquisition of title would occur by unilateral Imperial decree).Footnote 162 This protectorate was recognized one year later, in 1886, by the British as falling to the German sphere of influence.Footnote 163 Wake’s location is thus established as outside the Carolines and Palaos and probably within the Marshall Islands.

Historian Dirk Spennemann, who has undertaken a forensic analysis of the German Foreign Office archives of the time, states that among the Spanish territories ceded at the same time as the 1885 Hispano-German Protocol’s conclusion were both Wake and Johnston (Kalama) atolls.Footnote 164 This Spanish cession of Wake to Germany is referenced in an 1899 letter from von Bulow to the German ambassador in Washington, leading Spennemann to conclude that in the eyes of Germany and Spain at least, Germany was sovereign over Wake island.Footnote 165 In addition to this cession by Spain, Germany’s claim to Wake has been said to derive from earlier agreements that it concluded in 1878 with the local chiefs. Whether or not the latter agreements were at the time considered treaties within the meaning of contemporaneous international law, such acts could under the international law then in force, nonetheless create ‘suzerainty over the native state [that] becomes the basis of territorial sovereignty as towards other members of the community of nations’.Footnote 166 Finally, in case there were any doubts as to Wake’s location, Spain would ultimately cede the Carolinas and Palau to Germany on 12 February 1899. However, the US claims to have acquired title either one year earlier (in 1898), or one month earlier (in January 1899).

US title to Wake, which is without fresh water and traditionally uninhabited, is sometimes said to derive from the 1898 Treaty of Paris by which Spain ceded the Philippines and Guam to the US, although no mention is made of Wake Island in that treaty and it is indeed considered to be a weak basis for the assertion of sovereignty given the clear geographic co-ordinates of the 1875 (and so prior) Hispano-German agreement.Footnote 167 Other, more frequent, accounts indicate that Wake Island was claimed for the US on 17 January 1899 by Commander Taussig on the USS Bennington.Footnote 168 An article co-signed by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt asserts that there was no confirmatory action by Congress of this move,Footnote 169 although Spennemann documents some acts of display of sovereignty undertaken on the day of the claim.Footnote 170

Significantly, Germany itself never strenuously defended its title over Wake Island, being more concerned in the 1880s–1890s, to secure Samoa. Whether this amounted to an abandonment of sovereignty, with the requisite animus and corpus is not clear.Footnote 171 It is nonetheless important for legal purposes that Germany’s claim to Wake was forgotten following the First World War when it lost its Pacific territories and, as a result, unlike the other German Pacific territories north of the equator, Wake Island did not effectively form part of the Japanese administered South Pacific Mandate created in 1922. German abandonment furnishes the strongest legal footing for the US’ annexation of the island in 1934 (incidentally, a year after Japan withdrew from the League of Nations but maintained administration over the Marshall Islands) when on 29 December 1934 President Roosevelt, by executive order placed Wake Island under the control and jurisdiction of the Secretary of Navy.Footnote 172

Assuming no prior abandonment by Germany – which can only operate if ‘manifested clearly and without any doubt’Footnote 173 – and indeed that initial German title can be sufficiently proved, did German sovereignty over Wake persist? Or was sovereignty removed from Germany by operation of the law given that this would be the effect of the Mandate system in respect of all Axis held territories,Footnote 174 even if the League mistakenly forgot to include the island (both nominally and as a matter of fact on the ground) within that regime? This too leaves open the possibility of US annexation in 1934. A similar result might be achieved by operation of the – not undisputed – principle of acquisitive prescription,Footnote 175 although the Marshallese lack of opportunity to protest, as an entity under Mandate and Trust, should in this case be taken into account. If on the other hand, as Spennemann argues,Footnote 176 the territory was by operation of the law, in fact within the ambit of the Japanese Pacific Mandate following the First World War and the subsequent post Second World War Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, then Wake should have reverted to the Marshall Islands upon the latter’s independence and decision to enter into free association with the US.Footnote 177

It may be that there are insufficient facts to determine sovereignty over Wake. But as in the case of Hunter and Matthew, Wake is also of significant cultural importance to the Marshallese and in the event that sovereignty cannot be established, the opportunity to draw upon the international law of indigenous peoples as it develops through instruments such as the 2007 Declaration, provides one avenue for at least a partial satisfaction of Marshall Island demands. Indeed, the Torres Strait solution might be the very well suited to this end, recalling also that traditional rights might be asserted even in the absence of agreement as seen above in relation to Matthew and Hunter – assuming its customary status given that the US, like France, has not ratified ILO Convention 169. The difficulty in this case is the strategic importance of Wake Island to the US which currently uses it for military purposes. But the US has already used undisputed Marshall Islands territory in the same way – the nuclear testing at Bikini and Enewetak Atolls when the Marshall Islands was part of the Strategic Trust.

3.2.2 The Guano Islands Act (1856) and Swains (Olohega/Olosenga) Island

The US claims a number of islands in the Pacific under the 1856 Guano Islands Act. This provides that subject to conditions, private US citizens can claim uninhabited islands, islets, cays as well as rocks, for guano production, with the consequence that the territory then ‘appertains’ to the US.Footnote 178 Whilst the Clipperton Island case (Clipperton also being located in the Pacific) shows that the conferral of a guano concession can amount to a display of sovereignty, the meaning of the term ‘appertain’ in the 1856 Act does not necessarily refer to sovereignty.Footnote 179 Certainly, the aim of the instrument – as was so often the case in colonial practice – was to enable exclusive use of the territory without concomitant responsibilities internally.Footnote 180 In two cases, the US Supreme Court confirmed this purported effect of the 1856 Act from the perspective of US law: the rights of exclusive possession to the exclusion of other states are acquired externally, albeit without the responsibilities that are ordinarily entailed by sovereignty internally. Whilst these judicial pronouncements might be seen by some to support the conferral of sovereignty, the US executive has repeatedly denied as much,Footnote 181 and indeed, under US law it would appear that the executive, rather than the judiciary, is the authority in matters of sovereignty over territory.Footnote 182 Moreover, the grants under the Act were only temporary, until the exhaustion of the guano deposits, strengthening the conclusion that under the Guano Islands Act, the requisite intention to acquire sovereignty was absent.

In practice the US administration of the 70 or so claimed territories under the Guano Islands Act has been described as chaotic.Footnote 183 Sometimes the islands did not even fall within the terms of the 1856 Act. For instance, Palmyra, with a ‘variable and temporary’ population of between four and 20 people,Footnote 184 (administratively severed from Hawaii but remaining incorporated – and so eligible to become a state in the US union) turned out not to consist of guano. It is not surprising that these claims would often be followed up by acts more immediately recognized by international law for the acquisition of title, although in a few cases the solutions were innovative.

One of these concerned the islands of Canton and Enderbury, located in the Phoenix group in Micronesia and now part of Kiribati (see Figure 4). Both islands were claimed by US under the Guano Islands Act, but then abandoned, and then claimed by Great Britain, a London based company establishing business there.Footnote 185 The islands were, however, seen as good aircraft landing strips, and so these two states concluded an agreement in 1939 to establish joint governance over the territory without prejudice to the question of sovereignty. By precluding for either of themselves a preponderance of influence, the colonial powers could enjoy the attributes of sovereignty in the remote territories of the Pacific without its inconveniences or responsibilities – and in doing so, forestall further dispute amongst themselves. Ultimately the situation over Canton and Enderbury would be liquidated by the Treaty of Tarawa (1979), pursuant to which both the UK and US relinquished their claims and the islands would become a part of Kiribati.Footnote 186

Figure 4. Territorial Disputes and Lesser Disagreements.

Indeed, most of the territories claimed in connection with the Guano Islands Act have been liquidated by treaty (see Figure 4): in 1979 (US-Kiribati treaty); 1980 (the treaty between US–New Zealand (on behalf of Tokelau) and the treaty between US-Cook Islands); and 1983 (US-Tuvalu treaty).Footnote 187 Pursuant to the Treaty of Tarawa, the US retained Kingman Reef and Palmyra Atoll, as well as Jarvis, Howland and Baker islands.Footnote 188 It also relinquished its claim to 15 islands – eight in the Phoenix Group and five in the Line Group. (Kiribati, Treaty of Friendship and Territorial Sovereignty, 23 September 1979).Footnote 189 Finally one can note that some of the islands are the subject of competing claims as between Hawaii and the US – the case of Palmyra and Cornwallis.Footnote 190

One of the territories claimed originally by virtue of the Guano Islands Act and which remains in contention despite the conclusion of a maritime boundary treaty, is Swains/Olohega Island. This small island is geographically part of the Tokelau chainFootnote 191 (see Figure 4). Tokelau protests the US claim of sovereignty; the latter claiming to have annexed the island by passage of a joint Resolution of Congress on 4 March 1925 subsequent to settlement there by a US national pursuant to the 1856 Guano Island Act. Leaving aside geography and cultural features, Tokelau appears to have asserted some basis of claim to the island by virtue of its prior occupation by a Frenchman by the name of Tyrel.Footnote 192 Certainly at the time of its discovery by Spain in 1606, Swains was inhabited by Polynesians and it is claimed that it was in ‘indigenous Tokelauan hands’ in 1840 when a US whaler, Captain Swain visited the island, although the island would apparently be claimed by the British at about the same time.Footnote 193 It would however never be considered by the British as part of the three islands called the Union group (being today’s Tokelau) that had been annexed by Captain Oldham for the British in 1888.Footnote 194 Tokelau itself was part of the GEIC until 1926 when its administration was transferred to New Zealand (and formally ceded in 1948). Swains Island is currently administered by American Samoa, a NSGT. Tokelau remains a New Zealand dependency and also listed by the UN as a NSGT.

By virtue of a maritime delimitation treaty of 2 December 1980 between the US and New Zealand known as the Tokehega Treaty, New Zealand renounced any claim to Swains Island.Footnote 195 This was done as part of a broader settlement also including the Cook IslandsFootnote 196 and would see the US renounce claims to seven other islands in the region: Pukapuka (Danger), Manahiki, Rakahanga, Penrhyn (claimed by the Cook Islands) and Atafu (Duke of York Island), Nukunono (Duke of Clarence Island) and Fakaofo (Bowditch Island) – the latter three being Tokelau itself!Footnote 197 Wikileaks correspondence nonetheless reveals that in 2007 the US asked New Zealand to recognize US sovereignty over Swains after Tokelau alleged that Tokelau was sovereign over the island,Footnote 198 revealing that the matter is still in some contention.

Assuming Tokelau could establish prior title (which is not readily apparent), the question of whether New Zealand could in 1980 – clearly after the emergence of the right to self-determination – renounce Swains on behalf of Tokelau and thus break up its territorial integrity is an interesting one. If it did so unlawfully, the 1980 treaty would be invalid, in accordance with the terms of Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) – assuming self-determination was by 1980 peremptory – and consequently requiring a reconsideration of all the islands renounced by New Zealand and the US in that agreement. Significantly, however, the signing ceremony of the 1980 treaty was concluded in the presence of the Tokelauan chief and indeed co-signed by him. Moreover, the preamble, an aid to the treaty’s interpretation, provides that the treaty is concluded pending Tokelau’s exercise of its right to self-determination. It would be difficult to prove that this was not a matter of free will, but that would certainly be the argument that Tokelau would want to make in order to revise the question of sovereignty over Swains/Olohega.

4. Conclusion

Having mapped the Pacific’s various sovereignty claims – a task that the legal literature has to date overlooked – one sees that the colonial carve-up of the region occasionally separated local populations from their traditional and cultural lands and that this invariably occurred when colonial borders cut across natural archipelagos; the very locations where today one finds most of the Pacific’s sovereignty claims: Bougainville; Hunter and Matthew; Wake and Swains. But these disagreements exist against a broader context: first, one of general compliance by the PICs with the rules of international law relative to territory. Already during the decolonization process, the territorial integrity of the self-determination units was accepted pre-independence, as was the principle of uti possidetis juris on independence. Modern inter-state territorial disputes amongst the PICs are rare to non-existent, and despite internal ethnic strife occasionally precipitating the movement of people across borders (such as from West Papua to PNG or from Bougainville to the Solomon Islands) and the political fragility of some states (such as the Solomon Islands), secessionist claims, like other territorial claims, have never led to inter-state hostilities.

Second, self-determination remains unfinished business. The region still counts six NSGTs and at least one entity (Norfolk Island) seeks to join that group. In cases where international territorial (as opposed to secessionist) claims exist, they do so against current and former colonial powers, all of whom currently control the territories in question (Hunter and Matthew, Swains and Wake). Whilst some claims may be hard to prove (e.g., Swains), opportunity nonetheless exists to shape future territorial settlements in a way that remains true to the region’s values; and in particular the shared respect and understanding amongst the PICs of indigenous attachment to traditional lands. The increasing opposability under international law of indigenous rights strengthens that prospect. Innovative solutions have been developed to achieve this end – even in cases where the former colonial power retains control of the contested territory. The legal solution adopted in the Torres Strait (with Australia, a former colonial power) is an illustration. The case of Banaba another, where independently of foreign powers, an innovative solution was found. Moreover, the region’s political institutions - both the Forum and sub-regionally, the MSG – empower those deemed by the newly independent states to belong to the region. As seen on the eve of Vanuatu’s independence, these international institutions can confer a degree of capacity and thus some international legal personality on sub-state entities pending their independence. In this way indigenous voices can be leveraged. This has lessons for those NSGTs with territorial claims, but also for Vanuatu in respect of Hunter and Matthew given its agreement with the FLNKS in the Kéamu Accord.