This letter introduces a comprehensive data collection on roll-call votes (RCVs) in the German Bundestag between 1949 and 2013. RCVs are one of the most important data sources on parliamentary behavior. Beyond producing legislative output, RCVs put the positions of Members of Parliament (MPs) and party groups on the public record, serve party leaders as an instrument with which to monitor backbench behavior, and enable opposition parties to obstruct parliamentary business (Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld1995a). RCVs from various parliaments have been used to investigate, among others, party competition and legislative coalition formation, the strategic behavior of individual MPs and legislative parties, party unity and intraparty politics, and MP responsiveness to voters and other outside interests (for example, Carey Reference Carey2007; Carrubba, Gabel and Hug Reference Carrubba, Gabel and Hug2008; Eggers and Spirling Reference Eggers and Spirling2016; Hix Reference Hix2004; Hix and Noury Reference Hix and Noury2016; Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997).

Empirical research can rely on comprehensive longitudinal roll-call data for a number of countries, most notably the US Congress (for example, Lewis et al. Reference Lewis2017; Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997),Footnote 1 the European Parliament (Hix, Noury and Roland Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2005), and the British House of Commons (for example, Eggers and Spirling Reference Eggers and Spirling2016; Norton Reference Norton1975); on some cross-country comparative datasets for shorter periods of time (Carey Reference Carey2007; Coman Reference Coman2015; Hix and Noury Reference Hix and Noury2016; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006); and on numerous contemporary and historical single-country datasets.Footnote 2

For the German Bundestag, RCV data has thus far only been available for limited periods of time (Ohmura Reference Ohmura2014b; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld1995b; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2010; Stratmann Reference Stratmann2006). At the same time, the Bundestag is an attractive parliament to study. It is one of the most powerful legislatures in a parliamentary democracy (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2011); its internal organization is rather elaborate (Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000); and its mixed electoral system offers attractive opportunities to analyze one of the most fundamental aspects of legislative behavior: the effect of electoral rules on legislative voting (for example, Manow Reference Manow2015; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2010; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2015).

The datasets described here contain information on individual voting behavior and a wide array of variables that characterize the MPs and RCVs they voted on. The data are freely available to the academic community at Harvard Dataverse.Footnote 3 In this letter, we describe the structure of the datasets, present descriptive information on key variables and discuss potential research questions to be addressed with the data.

New Datasets on Roll-Call Votes in the German Bundestag

The most fundamental data for roll-call analysis is an MP’s decision to vote yea/nay or abstain on a motion – or not to cast a vote at all. To this data, we add personal information on the MPs and contextual information on the motions voted upon. Both sets of variables can be used to explain various questions about roll-call behavior. The combination of extensive contextual information and voting data is a distinguishing feature of this dataset; most other roll-call datasets are limited to voting behavior.

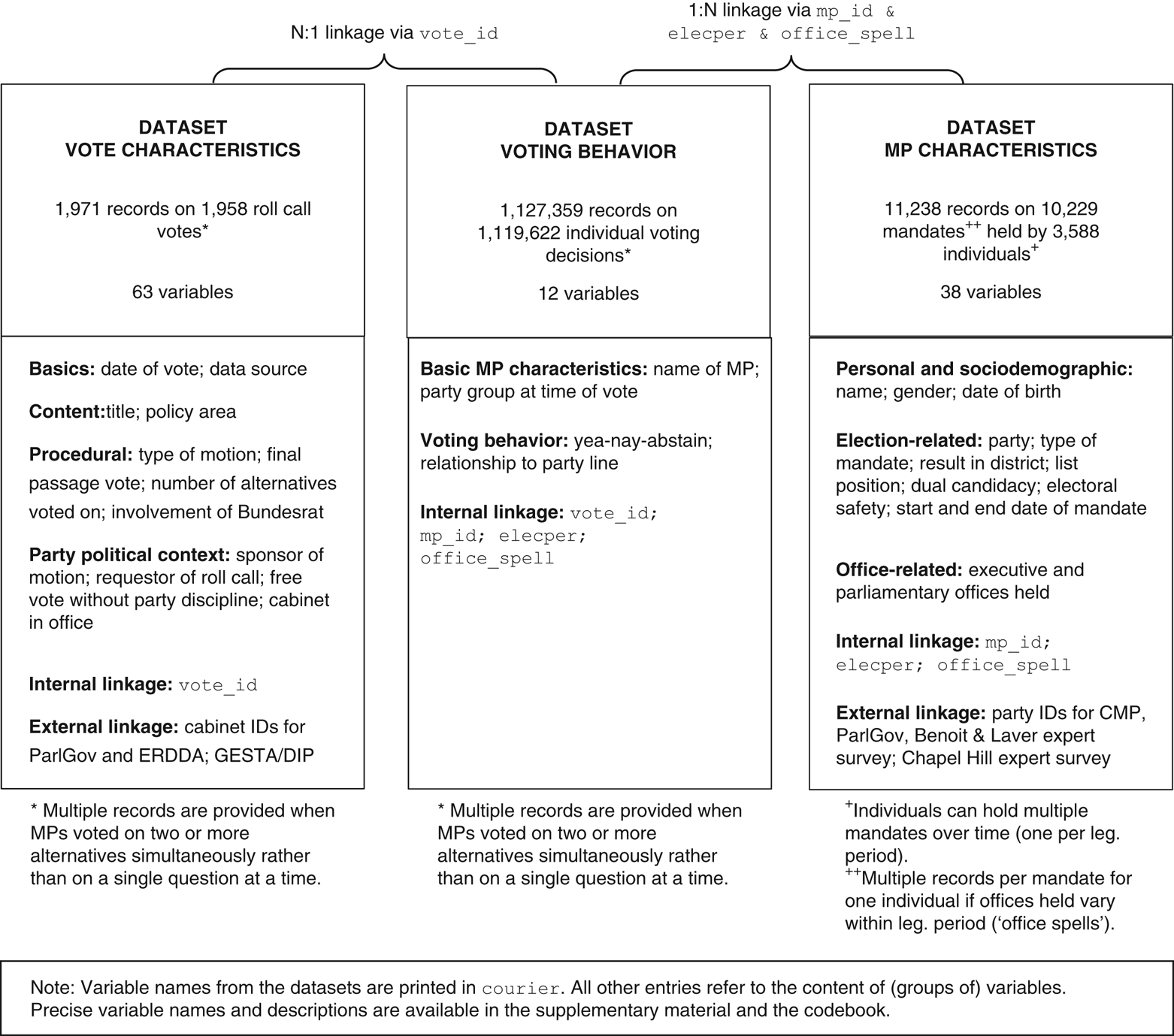

We record the data in three separate datasets that are linked via different identification (ID) variables. This setup allows for efficient data storage and enables researchers to create datasets at different levels of aggregation depending on their research question (we discuss some examples in the concluding section). Furthermore, we provide ID variables to link our data to datasets on party positions and government characteristics.Footnote 4

The RCVs were collected from the official minutes of the Bundestag. The contextual variables stem mostly from data handbooks published by the research service of the Bundestag (Wissenschaftlicher Dienst).Footnote 5Figure 1 visualizes the structure of the three datasets, their linkage and the types of variables contained in each of them. The supplementary material provides a list of all variables in the dataset; further details are available in the codebook at Harvard Dataverse.

Figure 1 The structure of the datasets

Roll-Call Vote Characteristics

The dataset VOTE CHARACTERISTICS contains information on all 1,958 roll calls during the first seventeen legislative periods of the Bundestag (1949–2013). A few roll calls contained a simultaneous choice with more than one alternative (for example, a single vote on four different proposals to reform the abortion law in 1974). These RCVs have multiple records in the dataset (one for each alternative) to allow voting behavior to be coded in the same categories of yea-nay-abstention.

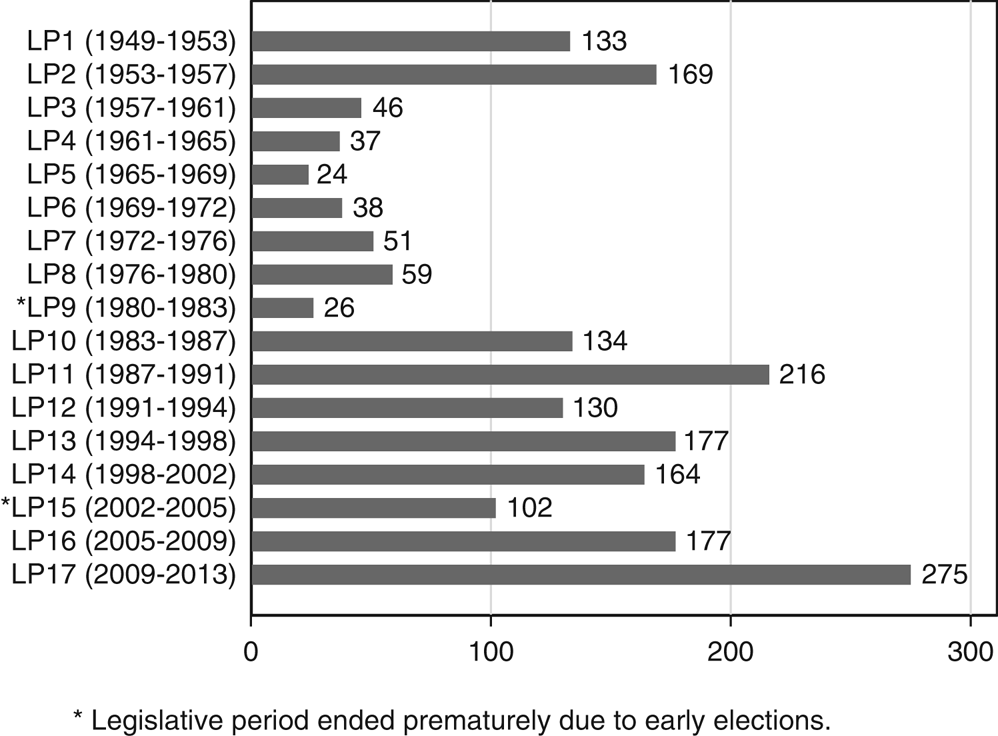

RCVs are not the Bundestag’s default voting method. The chamber votes via roll call only if this is actively requested by a sufficiently large group of MPs, currently 5 per cent of all MPs or a parliamentary party group.Footnote 6 As a result, the number of roll calls is relatively small and varies over time (Figure 2). About 5 per cent of all final passage votes are taken by roll call (Bergmann and Saalfeld Reference Bergmann and Saalfeld2016); for other types of motions the share is unknown because there are no data on the number of votes taken by other procedures.

Figure 2 The frequency of roll-call votes by legislative period

Any study of roll-call voting in Germany must take this selection process into account, because it most likely leads to an unrepresentative sample consisting of high-salience votes. Whenever possible, we coded the party requesting the roll call to allow researchers to model this selection process.Footnote 7Figure 3 plots RCVs initiated by government parties, opposition parties and both types of parties together, both in absolute numbers and as percentages of all roll calls during a legislative period (indicated by the height of the bars). The graph reveals that most RCVs were requested by opposition parties (overall 70 per cent) but shows variation over time.

Figure 3 Roll-call requests by government status and legislative period

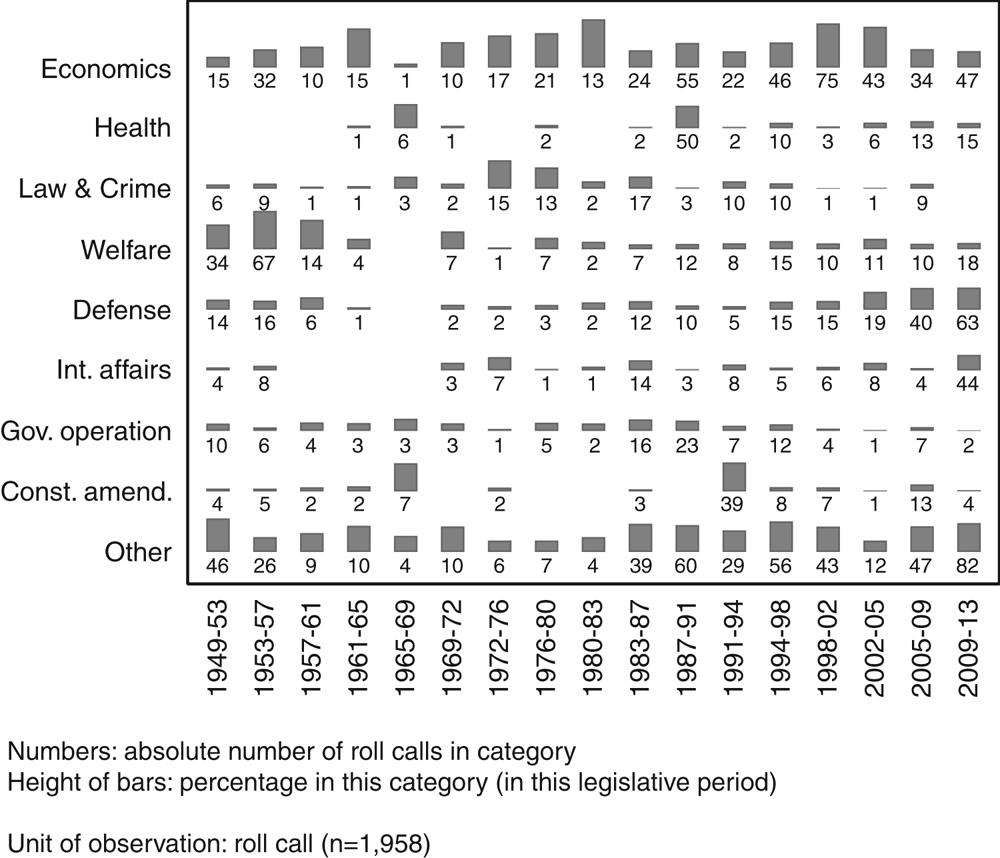

The dataset contains several variables that can be used to model the roll-call selection process and to explain observed voting behavior. First, we coded the policy area of the motion based on the German Policy Agendas codebook (Breunig Reference Breunig, Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014). Figure 4 indicates that most roll calls related to economic policy, welfare (especially in early periods) and (in recent years) defense (mostly on foreign deployment of the German military).

Figure 4 Primary policy areas of roll-call votes by legislative period

Secondly, we recorded the sponsor of the motion (not to be confused with the actor requesting the roll call). Over the entire period, 63 per cent of all roll calls were held on motions sponsored by opposition parties, one-third by government parties and the remaining small share jointly by parties from both camps. In 74 per cent of all cases, the roll-call vote was requested by the party that sponsored the original motion. We also identified 102 free votes on which the leadership of at least one party group waived party discipline, mostly on ethical and other conscience issues (Ohmura Reference Ohmura2014a). In addition, we coded the formal type of motion (for example, bill, amendment to bill, resolution, committee report, etc.), identified final passage votes, and recorded the constitutional veto power of the second chamber, the Bundesrat, with regard to the motion.

These data allow us to contribute to the ongoing international debate on strategic roll-call requests and the amount of bias it introduces in roll-call studies (for example, Carrubba, Gabel and Hug Reference Carrubba, Gabel and Hug2008; Hug Reference Hug2010; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld1995a). An initial analysis of the selection process for final passage votes shows that the likelihood that the vote is taken by roll call increases with the number of parties in the Bundestag, the ideological polarization of the party system on the policy dimension of the vote and the level of electoral volatility (Bergmann and Saalfeld Reference Bergmann and Saalfeld2016). Furthermore, changing institutional hurdles for requesting roll calls affect their frequency, but are clearly not the only explanation because the number of roll calls varies considerably within periods with stable rules.Footnote 8

MP Characteristics

The dataset MP CHARACATERISTICS comprises all 3,588 individuals who participated in at least one RCV in the Bundestag until the end of the seventeenth legislative period in 2013. First, it provides basic biographic data (date of birth and gender) as well as information on MPs’ partisan affiliations and length of service. Secondly, the dataset includes variables on the way MPs won their seats. For each legislative period we coded how an MP was elected in the German mixed electoral system (either via a single-member district or a party list), whether she ran as a candidate in both tiers and how competitive her election was (closeness of the district race, rank on the party list, and estimated re-election probabilities; see Stoffel and Sieberer Reference Stoffel and Sieberer2018). Finally, the dataset records the exact time periods during which MPs held any of the following executive or legislative offices: cabinet minister, junior minister, president or vice president of the Bundestag, (vice-)chair of a standing committee, (vice-)chair of a parliamentary party group and party whip.

Voting Behavior

The dataset VOTING BEHAVIOR records the behavior of all MPs associated with a parliamentary party group on all roll-call votes (1,119,622 individual decisions).Footnote 9 The total number of records is slightly higher (1,127,359), because voting behavior on RCVs with multiple alternatives is split into multiple observations per MP (one for each alternative). Each record contains the MP’s partisan affiliation at the time of the vote and two variables on voting behavior: one records how the MP voted on the motion (yea, nay, abstention, absence and a few residual categories). The second variable codes how the MP positioned herself with respect to the party line, which we define as the majority position within the party group or, in the few cases without an absolute majority within a group, as the position taken by the chair of the parliamentary party group.

Descriptively, this variable indicates high levels of unity. Figure 5 displays, for each party and legislative period, the share of all voting decisions that (a) were in line with the party position, (b) deviated weakly from it (for example, abstention when the party line was yea or nay) or (c) deviated strongly (yea if the party voted nay and vice versa). While deviation was slightly more common among Christian Democrats and Liberals in the 1950s and 1960s and is more frequent for the Greens compared to other parties, the overall picture is one of strong party unity.Footnote 10

Figure 5 Individual voting behavior with regard to the party line, by party and legislative period

Possible Research Questions

The datasets introduced in this letter enable researchers to study a wide range of questions with regard to legislative behavior and party competition in Germany. This concluding section discusses particularly promising fields of research (beyond the question of strategic roll-call requests we discussed above) as well as some limitations of our data.

We start with two caveats. First, any analysis must bear in mind the selective character of the sample. Roll calls in the Bundestag are confined to motions that are sufficiently important for at least one party to request a recorded vote. Thus, they allow inferences about legislative behavior on high-salience issues where public signaling is a main concern of the relevant actors. It is an open question, however, whether and how such findings generalize to more routine matters.

Secondly, the high levels of party voting (see Figure 5) as well as high coalition discipline make many roll calls uninformative for reconstructing the ideological positions of individual MPs using any scaling method. As in many other parliamentary democracies, such analyses mainly pick up party differences and, in particular, the government−opposition divide, but do not yield valid measures of ideological positions (Hix and Noury Reference Hix and Noury2016). For this endeavor, parliamentary speeches and surveys may be a more appropriate data source (for example, Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2016; Deschouwer and Depauw Reference Deschouwer and Depauw2014; Proksch and Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2015).

Despite the issues of selectivity and generalizability, the roll-call data can be used to address relevant questions on different levels of analysis, both specifically for the German context and, if connected to similar datasets, also in comparative perspective. At the party level, roll calls allow us to study the positions parties take on different issues and thus to map core features of party competition over time. Here, the need to request roll calls can even be an asset because it reveals information specifically on the issues for which different parties want to create parliamentary publicity. We can also compare the topics on the roll-call agenda (Figure 4) with the broader policy agenda (for example, as measured in the German Policy Agendas Project, Breunig Reference Breunig, Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014) to study how political parties shape the legislative agenda. Secondly, aggregated voting behavior at the party level allows us to study government−opposition dynamics and the competitive strategies opposition parties choose vis-à-vis the government (for example, Andeweg Reference Andeweg, Müller and Narud2013; Hohendorf, Saalfeld and Sieberer Reference Hohendorf, Saalfeld and Sieberer2018; Tuttnauer Reference Tuttnauer2018). Thirdly, the data allow a longitudinal analysis of party unity in the Bundestag and can thus contribute to the large body of literature that seeks to explain high levels of voting unity in legislatures as well as determinants of its variation (for example, Carey Reference Carey2007; Coman Reference Coman2015; Kam Reference Kam2009; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld1995b; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006; for a first analysis of our data with regard to party unity, see Bergmann et al. Reference Bergmann, Bailer, Ohmura, Saalfeld and Sieberer2016).

At the MP level, the most obvious question is why individual MPs express dissent by voting against their parties’ majority. Recent research on this question focuses on electoral incentives (for example, Carey Reference Carey2007; Coman Reference Coman2015; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006). The German mixed-member electoral system, in which MPs are simultaneously elected in single-member districts and via closed party lists, offers good conditions for studying this relationship, even though the degree to which it constitutes a quasi-experimental setting is contested (for competing views see, for example, Manow Reference Manow2015; Moser and Scheiner Reference Moser and Scheiner2004). As previous empirical research provides mixed results for different time periods, the question of a ‘mandate divide’ should be revisited based on our comprehensive time series (on Germany: Dishaw Reference Dishaw1971; Ohmura Reference Ohmura2014b; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld1995b; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2010; Stratmann Reference Stratmann2006; Zittel and Nyhuis Reference Zittel and Nyhuis2018; for a comparative perspective, see, for example, Crisp Reference Crisp2007; Herron Reference Herron2002; Jun and Hix Reference Jun and Hix2010). Beyond electoral system effects, our data can also be used to assess how other factors discussed in the literature such as policy area, election timing, gender, career stage, electoral vulnerability and constituency characteristics affect politicians’ decisions about whether to toe the party line (for example, Andre, Depauw and Martin Reference Andre, Depauw and Martin2015; Bailer and Ohmura Reference Bailer and Ohmura2018; Baumann, Debus and Müller Reference Baumann, Debus and Müller2015; Benedetto and Hix Reference Benedetto and Hix2007; Ohmura Reference Ohmura2014b). Finally, by matching our data to information on other activities within the legislature (for example, speeches or parliamentary questions) and beyond (for example, campaign activity) we can address broader questions on MP behavior such as the claim of an individualization and personalization of representation (for example, Karvonen Reference Karvonen2010; Zittel and Gschwend Reference Zittel and Gschwend2008).

Studying these questions requires different aggregations of the data, such as within party groups or for individual MPs over time. The disaggregated nature of our datasets provides a flexible way to easily create bespoke variables and datasets. For example, measures of party unity (such as the Rice Index) and the size of intraparty groups can be calculated by aggregating individual voting behavior within party groups for individual roll calls and subsequently for any chosen interval. Variables on legislative competition such as party seat shares or the margin of the government over the opposition are obtained by aggregating the number of MPs from each party or group of parties (such as government parties) at any point in time. Particularly interesting MPs (for example, party leaders or MPs with particular personal backgrounds) can easily be identified based on MP-specific variables in the dataset (such as age, gender, regional background and the various leadership positions coded) and data from other sources (for example, on MPs’ professional background or self-reported links to interest groups). Such MPs can subsequently be tracked over their entire career in the Bundestag.

To conclude, the datasets presented here provide ample opportunity for studying legislative behavior in the Bundestag over time and make the German case accessible for comparative roll-call analysis. We hope legislative scholars will make active use of this new resource.

Supplementary material

The data, replication instructions, and the data’s codebook can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VBWHRO and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000406

Author ORCID

Ulrich Sieberer, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4027-1393; Thomas Saalfeld, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2849-0665; Tamaki Ohmura, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4791-6978; Henning Bergmann, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1197-5092; Stefanie Bailer, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8646-6076.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation to Stefanie Bailer, Thomas Saalfeld and Ulrich Sieberer (Az. 10.12.1.125). We gratefully acknowledge this support as well as excellent research assistance by Matthias Bahr, Lukas Hohendorf, Franziska Loschert and Elena Maier. We thank Philip Manow for making contextual data on MPs available to us and Michael Stoffel for his contribution to estimating electoral safety measures.