Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the most prevalent life-threatening health conditions in western countries, associated with relatively high mortality rates. Cardiovascular events such as heart attack or stroke often lead to heightened levels of psychological stress, depression, and anxiety (Konstam et al., Reference Konstam, Moser and De Jong2005). It is also widely recognized that reducing stress and mental health problems is crucial to the prevention and recovery of cardiovascular events (Whalley et al., Reference Whalley, Rees and Davies2011). Therefore, national health guidelines, for instance by the British National Health Service, recommend offering psychological counseling to CVD patients (Gillham and Clark, Reference Gillham and Clark2011; Smith and Kneebone, Reference Smith and Kneebone2016).

Despite the importance of mental health care for CVD, only 24 psychological clinical trials have been published (Whalley et al., Reference Whalley, Rees and Davies2011; Tan and Morgan, Reference Tan and Morgan2015). These studies show that these treatments have only small effects on anxiety and depression and no consistent positive effects on outcomes such as quality-of-life and physical well-being. The statistical heterogeneity between studies is large, which makes it difficult to generalize findings. Interventions mainly include behavioral and cognitive exercises, such as relaxation, self-awareness, self-monitoring, risk education, emotional support, homework, behavior change guidance, and cognitive techniques (Whalley et al., Reference Whalley, Rees and Davies2011). In most studies, the therapeutic mechanisms leading to therapeutic change are not directly measured, thus it remains unknown how these interventions precisely lead to improvement. Thus, most psychological interventions in CVD have insufficient validity and efficacy. Therefore, it has been argued that new conceptual models are needed to understand the aetiology of stress and mental health problems in CVD patients. Such a new model may help to develop new — potentially more effective — psychological therapies (Carroll and Nuro, Reference Carroll and Nuro2002; Rounsaville et al., Reference Rounsaville, Carroll and Onken2006; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker2015).

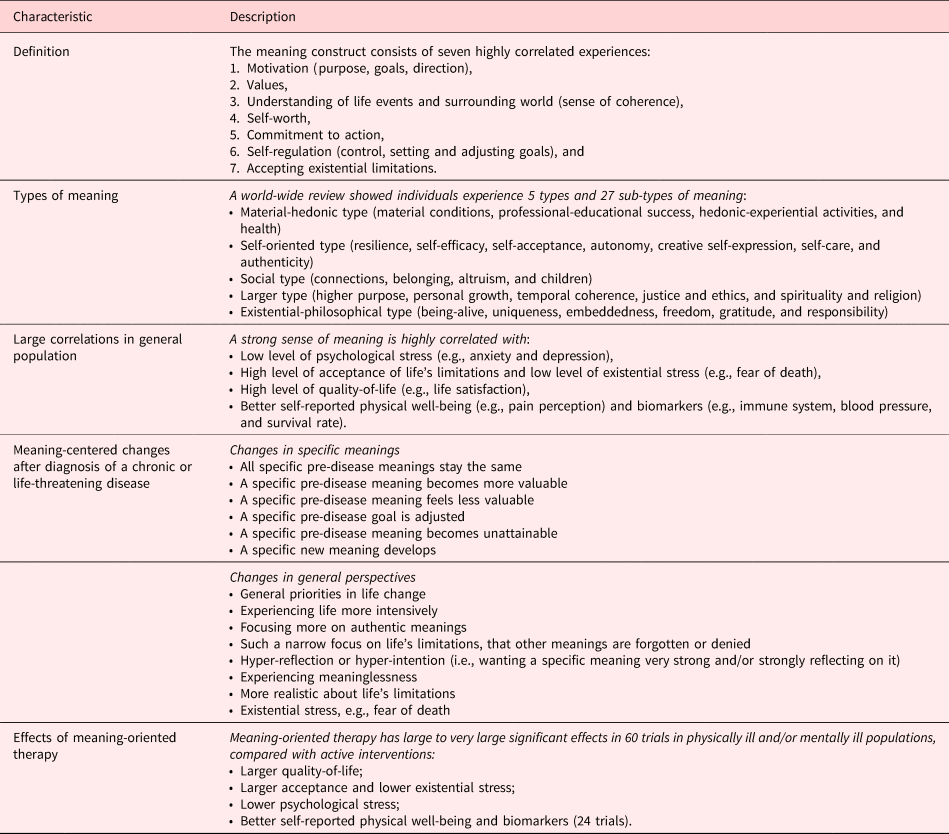

The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic literature review on the relationship between meaning and CVD, which will be used to develop a conceptual model, — which may be used as foundations for the development of new psychological treatments focusing on meaning. This focus on meaning follows from the growing literature on the relationship between CVD and positive psychological attributes, and particularly meaning-making (Park, Reference Park2010; Boehm and Kubzansky, Reference Boehm and Kubzansky2012; Dubois et al., Reference DuBois, Beach and Kashdan2012). This meaning-centered paradigm could explain the relative lack of effects of the usual care for CVD. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy does not systematically address the central question that most patients with a chronic or life-threatening physical disease such as CVD ask: “How can I live a meaningful and satisfying life despite my disease?” (Vos, Reference Vos2016a). Their primary concerns seem more related to their quest for meaning than to cognitive or behavioral issues. Research indicates that physically ill patients need to make sense of the disease and fit this into their overall perspective on life; they could subsequently experience psychological stress due to the tensions between these situational and global meanings (Park and Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997). Table 1 summarizes the empirical evidence from previous reviews for the relevance of meaning in coping with a chronic or life-threatening physical disease other than CVD (Vos, Reference Vos2016a, Reference Vos, Russo-Netzer, Schulenberg and Batthyany2016b). For example, this shows how meaning is an evidence-based psychological construct, which can be differentiated from other phenomena (Park and Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997; Park, Reference Park2010). A large body of the literature shows that in the general population, a lack of meaning leads to lower quality-of-life, higher levels of stress, and worse physical health such as higher blood pressure and suppressed immune system (Ryff et al., Reference Ryff, Singer and Dienberg Love2004; Vos, Reference Vos, Russo-Netzer, Schulenberg and Batthyany2016b).

Table 1. Overview of evidence-based characteristics of meaning in life (based on the review in Vos, Reference Vos2016a, Reference Vos2017)

Method

Several authors have published systematic literature reviews on general psychological causes and consequences of CVD (Rozanski et al., Reference Rozanski, Blumenthal and Kaplan1999; Dimsdale, Reference Dimsdale2008). A systematic meta-analysis on psychological treatments was published by Whalley et al. (Reference Whalley, Thompson and Taylor2014). Other reviews also describe the literature on general positive psychology in CVD (Boehm and Kubzansky, Reference Boehm and Kubzansky2012). Some reviews describe meaning amongst other factors (Rozanski et al., Reference Rozanski, Blumenthal and Davidson2005; Leegaard and Fagermoen, Reference Leegaard and Fagermoen2008; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Bavishi and Rozanski2016; Sin, Reference Sin2016). However, these studies do not review all meaning-centered aspects of meaning in CVD. Therefore, a systematic literature review was conducted on meaning and CVD. Meaning was defined as described in Table 1.

A systematic scoping literature review was conducted in consecutive rounds. A review protocol was developed in line with PRISMA and MOOSE-guidelines (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin and Morton2000; Liberati et al., Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff2009), which can be requested from the authors. The aim of this review was to search for any studies with or without interventions, with or without comparisons on the relationship between meaning in life and CVD. Meaning in life was defined as in Table 1. CVD was defined as any type of cardiovascular event or cardiovascular surgery (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, recovery of coronary artery or heart disease, and cerebrovascular accident).

First, databases were searched and included Pubmed, Web-of-Knowledge, PsycInfo, PsycTest, Medline, Embase, scholar.google.com, and Scopus. Two sets of search terms were combined. The set of terms regarding meaning was derived from previous reviews (Vos and Vitali, Reference Vos and Vitali2018) and included: “meaning in life” or “meaning of life” or “life meaning” or “meaningful life” or “living meaningful*” or “noetic” or “purpose in life” or “purpose of life” or “life purpose” or “purposes in life” or “purposes of life” or “life's purpose” or “goal in life” or “goal of life” or “goals of life” or “goals in life” or “life's goal*” or “value* in life” or “life's value*” or “significance of life” or “life destiny” or “destiny in life” or “destiny of life” or “life* essence” or “essence of life” or “sense of life” or “aims in life” or “aims of life” or “life* aims” or “meaning-making” or “existential” or “positive psychol*.” The set of terms regarding CVD included: “cardiovascular” or “heart” or “stroke” or “cardiac” or “cardiolog*” or “coronary” or myocardial or cerebrovascular*. Given the large number of findings, we added PubMed Mesh terms ([counseling] OR [psychotherapy] OR [psychology]) and capped scholar.google.com results at 10,000 hits. Additional studies were identified via the reference lists. Second, meaning-centered experts excluded articles through thorough reading of the titles and abstracts. Third, studies were excluded on basis of full-text manuscripts. Fourth, all studies are summarized and presented in the text. Fifth, risk of bias was assessed via the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Studies with a large risk of bias are described separately in the Findings section (Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of studies on meaning in CVD

Sixth, articles were synthesized via thematic analyses (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Braun and Hayfield2015). We did not limit the research findings to any specific variables, as we wanted to get a full overview of the relationships between CVD and meaning in life. We did not conduct meta-analyses due to the heterogeneity of instruments and study designs; therefore, we did also not present the detailed characteristics of each study. However, in the reporting of the studies, we summarize the average effects reported in the studies based on their unweighted average. For example, we describe R 2 of 0.75 as large, 0.50 moderately large, and 0.25 small. However, this presentation of effect size should be read as indicative only.

On the basis of this literature review, a conceptual model was developed, by combining this with a pre-existing review of meaning in other chronic and life-threatening diseases (Vos, Reference Vos2016a) and a review of the mechanisms of meaning-centered treatments (Vos, Reference Vos, Russo-Netzer, Schulenberg and Batthyany2016b, Reference Vos2017). Several authors have argued that a conceptual model needs to integrate all relevant literature while being concise, and this describes the central clinical phenomenon, aetiology, mechanisms of change, and impact on patients (Wampold, et al., Reference Wampold, Mondin and Moody1997; Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2009; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker2015; Vos, Reference Vos2017). The logical model is visualized.

Findings

Findings

17,084 publications were found, of which 113 were selected, reflecting 21,509 patients (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of included and excluded studies.

Eleven studies described meaning as a moderately strong predictor of cardiovascular risks. Nineteen studies described meaning as part of positive well-being and showed how positive well-being is a moderately strong predictor of cardiovascular health and lower CVD risk in the general population. Four studies described that CVD patients spontaneously ask questions about meaning with doctors and nurses. Thirty studies described changes in meaning in life and questions about meaning in life after a CVD event. Four studies described the positive effects of a meaning-oriented coping-style on adjusting to living with a congenital heart disease and reducing psychological stress, such as focusing on what is meaningful in life instead of on the limitations in life. Eighteen studies described meaning-centered coping as a predictor of long-term physical and psychological well-being in CVD patients. Fifteen studies described that experiencing life as meaningful and/or using meaning-oriented coping-styles predict CVD-related lifestyle changes in CVD patients, such as dieting and exercising. Twelve studies described psychological intervention studies in CVD patients which had one or more meaning-oriented aspects (most of which were positive psychology interventions), and which indicated moderate to large improvements in psychological well-being.

Analyses of risk of bias for the correlational studies indicated good or acceptable risk for all studies. Analyses of risk of bias revealed a significant risk for 10 out of 12 clinical trials, due to lack of control groups, unclear blinding and in 3 studies incomplete data reporting.

Meaning-centered conceptual model

The literature from the previous step was combined with other studies on the psychological aspects of coping with CVD, and on meaning in other chronic and life-threatening physical diseases. Figure 2 summarizes the meaning-centered model of CVD. This is followed by a description of the treatment manual that is based on this meaning-centered model.

Fig. 2. Logical meaning-centered model of CVD.

Predictors of CVD event

Empirical studies have suggested many factors which seem to increase the risk of CVD events. This includes, amongst others, biomedical risks such as genetics and body weight; lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise; level of psychological stress; stress reactivity and anxiety (Roest et al., Reference Roest, Martens and de Jonge2010); personality such as type A and hostility(Chida and Steptoe, Reference Chida and Steptoe2008); and quality-of-life such as optimism and meaning (Dubois et al., Reference DuBois, Beach and Kashdan2012). The effect of sociodemographic and life history risk factors on stress and CVD risks are mediated by meaning-centered coping (Chen et al., Reference Chen, McLean and Miller2015; Su et al., Reference Su, Jimenez and Roberts2015). For example, meaning-centered coping-styles reduce the level of psychological stress (Kopp et al., Reference Kopp, Skrabski and Szekely2007; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Arnold and Valenzuela2014b). These factors are likely intertwined, such as high stress levels leading to chronic inflammation which could contribute to CVD risks (Rohleder, Reference Rohleder2014; type A personality is associated with high levels of stress and low quality-of-life; physical exercise may also reduce stress; Scully et al., Reference Scully, Kremer and Meade1998).

Post-CVD event

After patients have experienced a CVD event, they may be required to make lifestyle changes, possibly because their disease makes it impossible to do the activities they did in the past, or they need to lower their CVD risk, for instance by exercising or stopping smoking. However, research shows that many patients find it difficult to make these changes, particularly due to a lack of motivation; therefore, intervention studies suggest that their motivation could be improved by focusing on the positive meaning of these activities for their life in general (Tinker et al., Reference Tinker, Rosal and Young2007). Many patients experience CVD events also as psychologically traumatic, particularly because it confronts them with the limitations and finitude of life, which may subsequently increase their level of psychological stress and decrease their quality-of-life and increase their risk of another CVD event (Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Jansson and Norberg1999; Stoll et al., Reference Stoll, Schelling and Goetz2000; Coughlin, Reference Coughlin2011). Like other potentially life-threatening diseases, the CVD event has suddenly confronted them with their limitations and finitude, they need to change parts of their life, and they may develop new general perspectives on life (LeMay and Wilson, Reference Lemay and Wilson2008). Qualitative studies show that many patients feel stuck in a vicious cycle of limitation and resignation, and they need to “use self-care” and “see the possibilities that exist in everyday life” (Mårtensson et al., Reference Mårtensson, Karlsson and Fridlund1997). People start to search for meaning in response to the existential limitations that CVD has confronted them with (Koizumi et al., Reference Koizumi, Ito and Kaneko2008). Thus, the core psychological question of coping with a CVD event and its aftermath seems to be their question: “how can I live a meaningful and satisfying life, despite the disease and the changes in my life?”

Meaning-oriented coping

Patients may have a broad range of answers to this question, as reviewed elsewhere (Vos, Reference Vos2016a, Reference Vos2017). This model focuses on the core component of meaning, which is mentioned in many of the dominant medical and health psychology paradigms, such as stress-coping and appraisal models (Park and Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Choi and Yum2016), terror management theory (Solomon et al., , Reference Solomon, Greenberg and Pyszczynski2015), motivation psychology and motivational interviewing (Lundahl et al., Reference Lundahl, Moleni and Burke2013), post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi et al., Reference Tedeschi, Park and Calhoun1998), and the recovery model (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Breeze and Neilson2014a). Similar to other diseases, several studies have shown that positive well-being, including meaning, is associated with lower cardiovascular risks and ill-being, albeit with modest effect sizes possibly because the effects are mediated by other factors such as lifestyle changes, stress level and biophysical changes (Boehm et al., Reference Boehm, Peterson and Kivimaki2011).

Long-term impact

When individuals can make sense of their disease and its treatment, they are more motivated for the required lifestyle changes (ibidem). Meaning-centered coping skills follow from the concept of meaning, which is an empirically validated experience, associated with motivation, values, self-worth, understanding and self-insight, self-worth, self-regulation, and goal-setting (Vos, Reference Vos2016a, Reference Vos2017). A review of 45,000 individuals world-wide show that individuals find meaning via material-hedonic, self-oriented, social, larger, or existential-philosophical types of meaning (ibidem). Research indicates that patients directly benefit from exploring a wide number of meanings (ibidem). Thus, meaning-centered coping-styles include a well-established range of skills, of which the most important are: accepting the disease and its limitations; experiencing meaning despite change (i.e., continued meanings, new meanings, transcending the situation, and new perspectives on life); using meaning as resilience and stress-buffer; beneficial coping-styles; hope and optimism; self-efficacy; and motivation to lifestyle change (ibidem).

Discussion

This systematic literature review has shown how meaning is a moderately strong predictor of the occurrence of a CVD event and of the short-term and long-term psychological and physical impact of CVD. To make sense of this literature, other studies were integrated in the development of a logical meaning-centered model of CVD. This model indicated the central role that meaning plays for patients before and after CVD events.

Systematic studies need to further confirm the meaning-centered model, and particularly examine how individuals create and adjust meaning after CVD events. There is a risk of confirmation bias due to reviewing only literature on meaning, and not searching for other literature on other CVD-related mechanisms.

Following the systematic literature review, CVD patients may be recommended to improve their sense of meaning in life, to reduce their CVD risk, and to improve their mental and physical well-being on short-term and long-term. As an improved sense of meaning in life seems to have moderately strong positive effects on these outcomes. Our review suggests that the effect size of meaning on CVD is similar or larger than the effect sizes for usual recommendations to improve the outcomes after a CVD event, such as stopping with smoking, reducing body weight, or using statins (Kannell and Higgins, Reference Kannel and Higgins1990; Law et al., Reference Law, Wald and Rudnicka2003; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Huxley and Wildman2008; Rizos et al., Reference Rizos, Ntzani and Bika2012). Although more systematic and longitudinal studies are warranted to confirm the strengths of these relationships, these findings indicate the importance of meaning in life in the recovery after CVD events. One of the ways to improve this could be to offer meaning-oriented therapy (Vos, Reference Vos2016a, Reference Vos2017).

Funding

The author does not claim any funding for this study.

Conflict of interest

The author does not claim any competing interests.