Introduction

Failure to thrive is a multifactorial condition associated with insufficient usable nutrition. The aetiology of failure to thrive associated with malnutrition is categorised as: inadequate dietary intake, inadequate absorption or utilisation, and/or increased metabolic requirements. Most cases occur secondary to inadequate dietary intake, gastroesophageal reflux, psychosocial issues, and/or mechanical swallowing dysfunction.Reference Zenel1 A rare cause of failure to thrive is cricopharyngeal achalasia, which occurs when the cricopharyngeus muscle fails to relax during deglutition, resulting in severe dysphagia. Cricopharyngeal achalasia in the paediatric population can present with feeding difficulty, aspiration and failure to thrive. Treatment is controversial, and includes both medical and surgical management. Another cause of failure to thrive is laryngomalacia, which usually presents with inspiratory stridor. Patients often have difficulty co-ordinating breathing and swallowing, resulting in poor feeding and dysphagia. Severe cases can be associated with aspiration, cyanosis, apnoea, pulmonary hypertension and failure to thrive.

We report a rare case of an infant with failure to thrive secondary to both laryngomalacia and cricopharyngeal achalasia. In addition, we show that functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing and videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing are complimentary to each other in the evaluation of children with failure to thrive and suspected oropharyngeal dysphagia, and demonstrate that concomitant management of both conditions can be carried out safely, with obviation of symptoms.

Case report

A four-month-old male presented to the emergency room for poor feeding, dehydration, failure to thrive and inspiratory stridor. The patient had been exclusively breast-fed, with reported poor swallowing co-ordination, fatigue during feeding after approximately 7 minutes and weight loss over the prior week.

His prenatal and birth histories were unremarkable. Although he was full-term at birth, weighing 3.77 kg, the patient did not regain his birth weight until almost three months of age. Growth parameters included a weight of 6.41 kg (39th percentile) and a length of 67 cm (less than 3rd percentile for weight-to-length ratio).

On examination, he had a slightly sunken fontanelle, capillary refill of 3 seconds, and was both socially and neurologically intact without obvious delay. His medical history was significant for laryngomalacia (which was being managed with anti-reflux medication), gastroesophageal reflux, and recurrent bronchiolitis and pneumonia, with multiple hospitalisations during his second and third months of life. Past surgical history included tongue and labial frenectomy for oral motor dysfunction. He was admitted to the gastrointestinal service for failure to thrive and potential gastrostomy tube placement.

Flexible fibre-optic laryngoscopy showed redundant tissue over the arytenoids, consistent with previously diagnosed laryngomalacia. A functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing revealed laryngeal penetration with both thin and thick liquids, and excessive hypopharyngeal secretions. A videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing showed frank aspiration and persistent prominence of the cricopharyngeus muscle, consistent with cricopharyngeal achalasia (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Prominence of cricopharyngeus muscle on pre-operative videofluoroscopic swallow study (arrow).

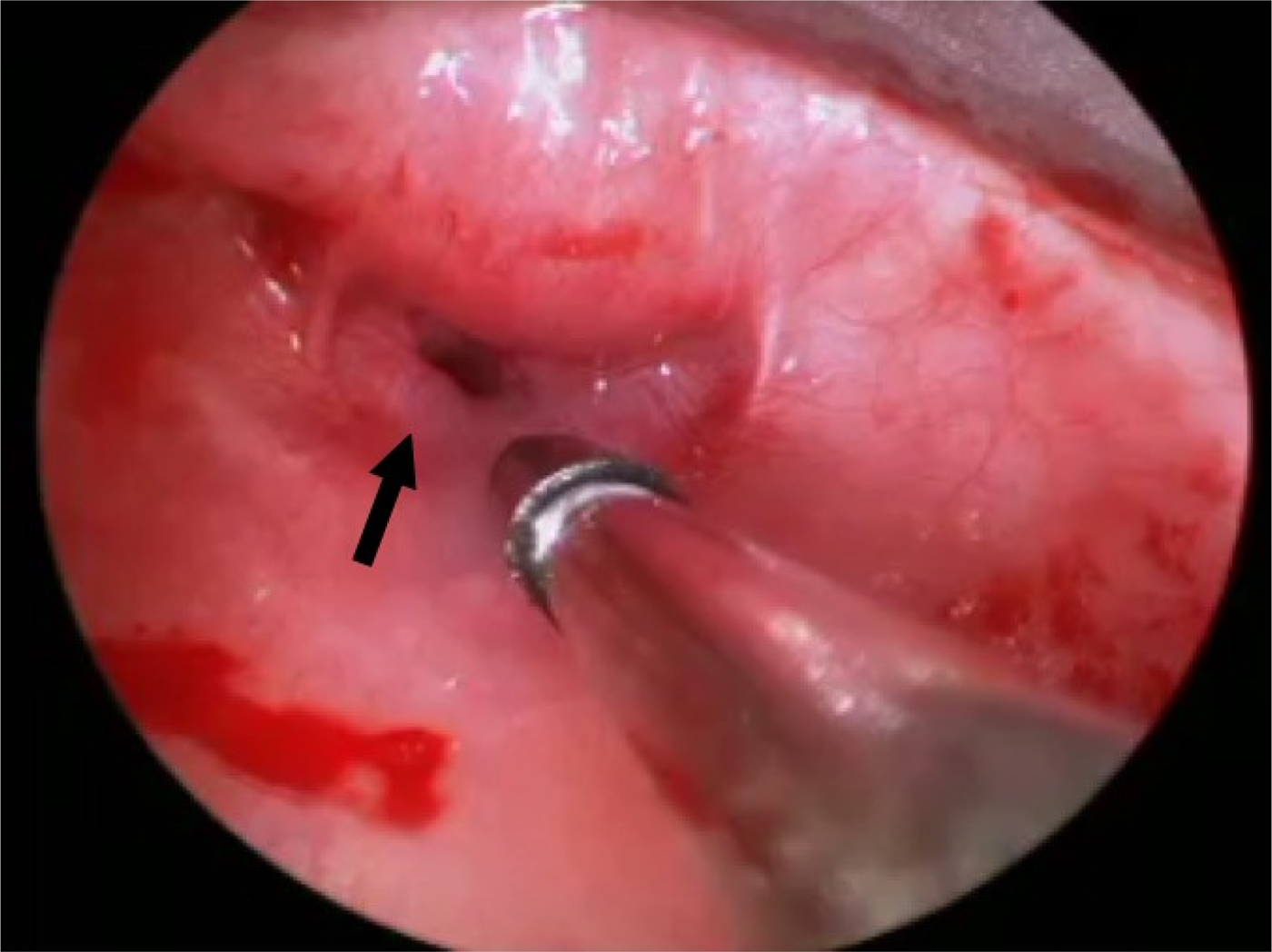

The patient was taken to the operating theatre for direct laryngoscopy with supraglottoplasty, bronchoscopy, oesophagoscopy, and botulinum toxin injection of the cricopharyngeus muscle. After endoscopic confirmation, a total of 25 units (0.5 ml of a solution of 50 U/ml) of botulinum toxin A (Botox; Allergan, Irvin, California, USA), freshly reconstituted with 0.9 per cent sterile saline, was injected into 3 sites of the cricopharyngeus muscle (Figure 2). Supraglottoplasty using a cold technique was performed, with removal of the redundant tissue over the arytenoids (Figure 3). A nasogastric tube was subsequently placed.

Fig. 2 Direct laryngoscopy image showing excessive redundant tissue over arytenoids, suggestive of laryngomalacia.

Fig. 3 Intra-operative image showing the cricopharyngeal bar (arrow) along with the injection needle for botulinum toxin.

The patient tolerated thickened breast milk on bedside swallow assessment, and the nasogastric tube was removed on the 1st post-operative day. The stridor resolved, and flexible fibre-optic laryngoscopy demonstrated no pooling of secretions and no evidence of laryngomalacia. A post-operative videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing showed that both the oral and pharyngeal phases were within normal limits; the cricopharyngeus muscle prominence was no longer identifiable (Figure 4).

Fig. 4 Resolution of cricopharyngeal bar on post-operative videofluoroscopic swallow study following botulinum toxin injection.

The patient was discharged home on the 3rd post-operative day. At the time of discharge, the patient was taking a full 6 fl oz (177 ml) feed. He remained on ranitidine, and continued speech and occupational therapy as an out-patient. At 3 months’ follow up, he weighed 9.6 kg and was at 90th percentile on the growth curve. He reportedly had occasional stridor, which was not audible during the clinic visit. Repeat flexible fibre-optic laryngoscopy findings were unremarkable.

Discussion

Cricopharyngeal achalasia interferes with the passage of a food bolus into the upper oesophagus due to the failure of upper oesophageal sphincter relaxation at the end of the pharyngeal phase. This ultimately results in the upper oesophageal sphincter being in a state of tonic contraction. The aetiology of cricopharyngeal achalasia is multifactorial, and the condition can either be isolated or associated with other neuromuscular disorders.Reference Sewell and Bauman2–Reference Salib, Aubert, Valioulis and de Billy4 Clinical signs and symptoms include feeding difficulty, regurgitation, aspiration and failure to thrive. The diagnosis is often delayed in children, and early feeding difficulties in an infant may be misinterpreted for a more common disorder such as laryngomalacia. Feeding difficulties secondary to laryngomalacia result from structural anomalies associated with the disorder and interruption of the suck-swallow-breathe mechanism. As a result, infants with laryngomalacia associated with dysphagia are more likely to develop failure to thrive. The abnormal feeding symptoms of cricopharyngeal achalasia are similar to those of laryngomalacia, and both may be associated with failure to thrive concomitantly. Cricopharyngeal achalasia in an infant is likely to be misdiagnosed as laryngomalacia or another feeding disorder until a swallow study is performed.

Videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing and airway endoscopy should be strongly recommended in children with laryngomalacia and feeding difficulties, to rule out other pathologies in the upper aerodigestive tract. The aetiology of the feeding difficulty in this case was initially based upon a known history of laryngomalacia. It was not until a videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing was performed and showed a persistent prominence of the cricopharyngeus muscle that the concomitant diagnosis of cricopharyngeal achalasia was made. Our review of scientific databases revealed no cases of the combined pathology.

Management of cricopharyngeal achalasia is controversial, especially concerning the paediatric population. Cricopharyngeal myotomy and oesophageal dilation have been cited as the preferred methods of treatment.Reference Barnes, Ho, Malhotra, Koltai and Messner5–Reference Erdeve, Kologlu, Saygili, Atasay and Arsan7 Medical management with nifedipine and nitrates has also been studied, with inconclusive results.Reference Barnes, Ho, Malhotra, Koltai and Messner5–Reference Erdeve, Kologlu, Saygili, Atasay and Arsan7 Treatment via botulinum toxin injection was first reported by Blitzer and Brin, in which they described excellent results with the percutaneous injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of cricopharyngeal achalasia in adults.Reference Blitzer and Brin8 The use of botulinum toxin has since evolved with direct injection into the cricopharyngeus muscle, which is both safe and efficacious.Reference Scholes, McEvoy, Mousa and Wiet9 While viable treatment options continue to improve, there remains a paucity in the reported incidence of paediatric cricopharyngeal achalasia, with spontaneous resolution often seen in neonates and infants. This suggests that the aetiology may be secondary to neuromuscular immaturity; therefore, initial management with botulinum injection may be preferred over surgical intervention in children.Reference Hussain and Di3

Scholes et al. performed a retrospective review of six children treated with botulinum toxin injection (mean dosage of 5.6 U/kg) for cricopharyngeal achalasia, with complete resolution of symptoms in four of the patients after one to two injection sessions.Reference Scholes, McEvoy, Mousa and Wiet9 While only temporarily therapeutic in the remaining two patients, the use of botulinum injection helped to confirm dysfunction at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle in all patients.Reference Scholes, McEvoy, Mousa and Wiet9 Barnes et al. also performed a retrospective study on three children with cricopharyngeal achalasia who underwent botulinum toxin injection in the cricopharyngeus muscle.Reference Barnes, Ho, Malhotra, Koltai and Messner5 With two to three sessions of botulinum injection (mean dosage of 3.1 U/kg), with a mean interval of 3.3 months between sessions, all patients improved clinically and had their feeding tubes removed. Cricopharyngeal achalasia symptoms resolved over a mean follow-up period of 22.1 months.Reference Barnes, Ho, Malhotra, Koltai and Messner5

Limitations of these studies include the need for long-term follow up and larger sample sizes. Nevertheless, the data successfully demonstrate the utility of botulinum toxin injection in the diagnosis and management of cricopharyngeal achalasia in the paediatric population. Our patient showed significant improvement after a single session with injections into three regions of the cricopharyngeus muscle.

• Functional endoscopic and videofluoroscopic evaluations of swallowing are complimentary in evaluating paediatric dysphagia

• Laryngomalacia can be associated with a secondary lesion such as cricopharyngeal achalasia, resulting in paediatric dysphagia

• Supraglottoplasty and botulinum toxin injection are effective for definitive management in cases of combined pathology, and can be safely performed in a single surgical setting

Conclusion

Cricopharyngeal achalasia is a rare condition of unknown aetiology in the paediatric population. Videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing and airway endoscopy are recommended in children with feeding difficulties, to rule out multiple pathologies in the upper aerodigestive tract. While the standard treatment is surgical myotomy, botulinum toxin injection may be a more appropriate option in the paediatric population.

Competing interests

None declared