Introduction

‘I only write music and let it speak for itself’ – such was Antonín Dvořák's attitude, according to Josef Kovařík (1871–1951), the composer's personal secretary in New York.Footnote 1 Indeed, throughout his career, Dvořák seemed reluctant to share his views publicly. Unlike Bedřich Smetana, who was known for his controversial opinion pieces for the newspaper Národní listy in the early 1860s,Footnote 2 and Zdeněk Fibich, who contributed regularly to the music journal Dalibor in the 1880s,Footnote 3 Dvořák did not write a single article for the Czech press,Footnote 4 and as a result, his exact perspective on many of the prevailing issues of the day – both aesthetic and political – has been difficult to ascertain. Yet, this rather reticent public persona should not be taken at face value. Projecting a ‘shy’ image of himself might be understood as a viable strategy for self-advancement. Moreover, Dvořák was not as passive as Kovařík suggested. Dvořák first emerged on the Prague scene in 1873,Footnote 5 and his in-person English debut came roughly a decade later, though he made some contacts in Austro-German circles in the intervening years. It was precisely during his visits to England, beginning in the mid-1880s, that Dvořák became particularly concerned about forging a certain kind of image for himself in the Czech lands. Far from taking a hands-off approach, Dvořák played an active role in determining exactly which aspects of his reception in England would be relayed to the Czech public. As demonstrated below, he took a carefully contrived path of self-promotion – one that was naturally voiced most explicitly during his trips to England, over a comparatively short period of time in his career.

Not only did Dvořák take a keen interest in English reviews of his music while he was abroad, but he also sent many of these reviews back home with the request that they be reprinted in Czech translation in the newspapers and journals of Prague. In his attempts to influence the ways in which he was being portrayed in these Czech periodicals, Dvořák enlisted the help of several prominent figures on the Prague music scene. Among them were Václav Juda Novotný and Emanuel Chvála, leading critics and promoters of Dvořák's music during the 1880s, as well as philologists Josef Zubatý and Václav Vladimír Zelený, who mainly contributed to Dvořák's cause by translating his English reviews into Czech, but occasionally acted as music critics in their own rights. With the exception of Chvála, each of these individuals accompanied Dvořák to England at one time or another and had the opportunity to witness the composer's reception there first-hand. When not serving as travel companions, these men were on the receiving end of countless reviews that Dvořák saw fit to send to Prague for re-publication. The periodicals in which these reviews were to appear, as mentioned by Dvořák in his letters, include Dalibor, a specialized music journal; Národní listy, which had by then become the main outlet of the more progressive political party in the Czech lands – the ‘Young Czechs’; and two Prague dailies that were owned by the Conservative ‘Old Czech Party’: Pokrok and the German-language Politik. Collectively, these publications represent a large range of groups co-existing in 1880s Prague, which suggests that Dvořák was hoping for a wide readership.Footnote 6 Though the occasional translated review did appear in the newspapers as per Dvořák's request,Footnote 7 it was the editorial staff at the journal Dalibor who really took up the task with a vengeance. Beginning in 1884, Dalibor ran a series of articles on Dvořák's trips to England; each of the articles contains a detailed report of the composer's successes and excerpted English reviews in Czech translation.Footnote 8 Since Dvořák was the mastermind behind much of the excerpting, this Dalibor series shows that the notoriously reticent composerFootnote 9 took a more active part in managing his press than previously presumed.Footnote 10

Some of Dvořák's other professional choices, including the dedications of his compositions, can also be viewed through this strategic lens. In describing virtuoso musicians of the eighteenth century in general, Dana Gooley observes that they tended to be somewhat unabashed in their self-promotion; ‘they proudly paraded their letters of recommendation’, writes Gooley, ‘and pompously dedicated commemorative compositions to the local sovereigns before whom they appeared. The more prestigious and powerful the patron, the better’.Footnote 11 While Dvořák was certainly more subtle in his approach – operating in the very different social and cultural climate of the late nineteenth century – he did seem surreptitiously to employ some of the same tactics as these eighteenth-century musicians in an attempt to court the public in the Czech lands. This is particularly evident in the dedication of one of Dvořák's most overtly patriotic and personally nostalgic works, his cantata Hymnus: Dědicové Bilé hory (Hymnus: Heirs of the White Mountain, 1872). The Prague premiere of Hymnus in 1873 marked an important juncture in Dvořák's career. The piece was remarkably well received, and in the decades that followed, both Dvořák himself and his critics in Prague would continue to look back on this event as the composer's first major success.Footnote 12 As this was his official Czech debut, the work's eventual dedication ‘to the English people’ seems rather surprising. As discussed below, the change in dedication occurred during Dvořák's sojourns in England during the mid-to-late 1880s and this meant withdrawing the initial dedication that Dvořák had intended – to Vítězslav Hálek, the author of the Hymnus text. Unusual though it may seem on the surface, this English dedication can be understood as a clever tactical ploy, meant to signal the composer's international credentials and clout to audiences at home. Both his excerpted English reviews and his Hymnus dedication show that Dvořák was quite adept at handling the ‘business’ side of his profession, and they provide a rare glimpse at Dvořák's role as his own strategist. At the same time, they illuminate a desire to protect Dvořák, and other composers of the nineteenth century, from potential accusations of strategic self-promotion.

More broadly, then, the case of Dvořák points to nineteenth-century notions of the ‘artist’.Footnote 13 It casts a spotlight on the false perception that composers are somehow removed from the concerns of everyday life. Specifically, it calls into question the Romantic-era insistence that composers eschew ‘materialistic’ pursuits in favour of devoting themselves solely to lofty, artistic goals. To some extent, such views of the artist continue to linger, obscuring the labour involved in musical creation in favour of a focus on music's metaphysical value alone. In highlighting the tactics and strategies that Dvořák used to advance his own career, this study not only offers a more nuanced interpretation of Dvořák's public personality, but – more importantly – it pushes back against prevailing perceptions of the ‘artist’ in general.

‘A good impression on the nation’: Dvořák's Excerpted English Reviews in the Czech Press

In a letter to critic Eduard Hanslick (1825–1904) dated 6 November 1886, Dvořák writes enthusiastically about his reception in England: ‘there may not be a country outside of my homeland, where my works are so cultivated, valued and loved’, he muses.Footnote 14 Making no fewer than nine trips to England in the span of just over a decade between 1884 and 1896, Dvořák established a good rapport with English audiences. This would prove to be advantageous not just in securing his reputation abroad, but also in elevating his status among his Czech compatriots, and discussions of Dvořák's largely favourable English press are particularly prominent in the composer's letters from the 1880s.Footnote 15 In some of his early correspondence from England, Dvořák presents the idea of publishing translated English reviews in Czech periodicals as a matter of mere practicality. Writing to Novotný while on his first trip to England – at a time when he was not yet confident with his English-language skills – Dvořák claims that these reprints in translation are his fastest means of finding out what is being written about him in London: ‘as usual, I have received the Prague paper today’ states Dvořák, ‘and in it, I have finally learned the content and meaning of the London critiques, for I am so busy that I do not have time to ask someone for a translation’.Footnote 16 Soon, however, the reprinted English reviews became a conduit through which Dvořák could assure readers at home of his unwavering devotion to the Czech nation and his aim to bring international glory to the Czechs. Already in the same letter, Dvořák thanks Novotný for overseeing the Czech publication of these reviews and adds: ‘I do not even have to tell you that it makes me very happy and I am overjoyed, when the good Czech people can find out about the triumphs of a Czech artist’.Footnote 17

Dvořák's desire to be portrayed as a Czech ‘nationalist’ in these reprinted English reviews largely dictated which portions were highlighted and which portions were downplayed or omitted. For instance, when sending an article from the London Daily News to Zubatý in August of 1885, Dvořák gives specific directions with regard to the translation. The article reports on a rehearsal of Dvořák's cantata The Spectre's Bride, Op. 69 (Svatební Košile, 1884) and ends with the following sentence in the English original: ‘at [the rehearsal's] conclusion, Herr Dvorák [sic], whose English is not quite so fluent as that of Herr Richter, addressed in German a few words of hearty praise of the magnificent manner in which the orchestra had read his difficult music at sight.’Footnote 18 Fearing that this sentence might incite criticism among the Czechs – that his speech in German might be construed as part of an effort to present himself to English audiences as a German composer – Dvořák writes to Zubatý: ‘please do not mention that I had to speak a few words in German because I do not know English yet … Perhaps you might write that I spoke in Turkish! You know how things are at home.’Footnote 19 Dvořák's quip demonstrates that he knew the Czech readers for whom these translations were intended. Having been censured in Dalibor some five years earlier for allowing exclusively German titles and texts to be published on the scores of his vocal works,Footnote 20 Dvořák was sensitive to his Czech audience and careful to avoid actions that might give rise to controversy.Footnote 21 A year later, in October of 1886 – in its coverage of Dvořák's fifth trip to England, specifically to Leeds – Národní listy specifies the language that Dvořák used to address his audience at a concert because it was not German this time; citing the Daily News, the Czech newspaper reports that Dvořák thanked the crowd in English, a language that would have undoubtedly been deemed much more acceptable to Czech readers.Footnote 22

Beyond issues of mere language, Dvořák seemed keen on drawing public attention to his own patriotism. He was very particular, for example, about how his interview for the Pall Mall Gazette was to appear in Czech translation. This interview – famously entitled ‘From Butcher to Baton’ – tells Dvořák's ‘rags-to-riches’ story and concludes with a strong patriotic statement from the composer:

Twenty years ago, we Slavs were nothing; now we feel our national life once more awakening, and who knows but that the glorious times may come back which five centuries ago were ours, when all Europe looked up to the powerful Czechs, the Slavs, the Bohemians, to whom I, too, belong, and to whom I am proud to belong.Footnote 23

In a letter to Novotný dated 15 October 1886, Dvořák is adamant that these remarks be reproduced for the Czech public, stating:

I would like to draw attention especially to the last sentence [of the interview], where I said that all of Europe used to gaze at our nation with admiration and that a time of glory will hopefully come again; our nation may be small, but we can nevertheless show what we were, what we are, and what we will be!Footnote 24

Dvořák followed this up three days later with another letter, providing detailed instructions for the Czech version of the interview to translator Zubatý: ‘see to it that it gets reprinted above all in Národní listy; I think that it will make a good impression on the nation. Leave out the biographical details, but make sure that the last exchange is reproduced in full. The nation will rejoice’.Footnote 25 Though Zubatý evidently managed to have it reprinted in Dalibor only, he complied with Dvořák's specifications in all other respects. Aware of the kind of effect that Dvořák's statement was supposed to have on Czech readers, Zubatý prefaced the translated quotation with a few sentences of his own, emphasizing Dvořák's loyalty to his Czech roots, in spite of his international accolades: ‘All, who have had the privilege to meet him in person, will know about Dvořák's sincere patriotism’, writes Zubatý. He continues:

Last spring, [serving as a companion on one of Dvořák's trips to England], I had the opportunity nearly every day to become convinced of the fact that Dvořák is not any different in far-away England than here in Prague. Even so, we are filled with renewed joy when we see that, in his national pride, our master distinguishes himself from countless other artists, great or small; we see that our delight in his renown will never be marred by accusations of national indifference.Footnote 26

There can be no reason to doubt the sincerity of Dvořák's remarks about his homeland; however, his eagerness to have them reprinted in translation also indicates a certain consciousness of his ‘nationalist’ reputation in the Czech press. As David Beveridge points out, ‘the outburst of nationalist sentiment at the close of this interview was intended for the Czech audience at home as much as for the British’.Footnote 27

Dvořák was not always as direct as these examples suggest, often leaving it up to the discretion of the Czech critics to determine which excerpts of the English reviews were suitable for reprinting. This is evident in his approach to the reviews of the St Ludmila oratorio, Op. 71 (Svatá Ludmila, 1885–86). Writing to Zubatý on 18 October 1886, Dvořák provides the following rather vague instructions:

Translate all [of the critiques and] give them to Novotný, so that he can adapt them as he sees fit. Perhaps he might write a feuilleton for his journal Hlas and then you – or he – can put those critiques that seem best into Politik or Národní listy. The best ones are probably those that were printed in the Daily News, Daily Telegraph, Saturday Times (especially), Daily Chronicle, Globe, Standard … Only be sure to give all of the newspapers the same critiques, perhaps two, three or more, but excerpted or however you would like.Footnote 28

Though much is left unspecified, even this example demonstrates that Dvořák usually chose the articles that were to be sent home himself and rarely did so without commenting on them in some way in the accompanying letters. He also had clear preferences when it came to English critics. Dvořák saw Joseph Bennett (1831–1911) of The Daily Telegraph as his staunchest defender in England and regarded Francis Hüffer (1845–89) of The Times as the least willing among the English to lend support to his cause. In a letter addressed to Chvála, dated 26 October 1886, Dvořák alludes to a difference of opinion with Hüffer at their first meeting and attributes the critic's reserve to this incident: ‘I had a conversation with [Hüffer] two years ago and we did not agree’, writes Dvořák, ‘I told him my honest opinion and ever since that time, his behaviour toward me is somewhat reserved and he makes use of every opportunity to take a stab at me’.Footnote 29 In contrast, Dvořák was consistently pleased with Bennett's reviews of his music, occasionally referring to him as the ‘English Hanslick’ – a nickname that indicates both the critic's willingness to promote Dvořák's music abroad and his authority in the journalistic press. This view of Bennett is echoed in Czech periodicals. Reporting on Dvořák's first London trip, an anonymous critic in Dalibor writes:

Thanks to criticism and English journalism, Dvořák is a popular individual today, and an individual who is a favourite not only in musical circles, but also in the eyes of the wider London audience. Especially favourable criticism on Dvořák was written by the critic Bennett, a diligent English soul, who, in his newspaper The Daily Telegraph, truthfully related Dvořák's past full of obstacles and his significance for Czech national music.Footnote 30

As expected, then, Dvořák tended to forward Bennett's articles to his contacts in the Czech lands and to avoid passing along Hüffer's critiques. Articles from The Daily Telegraph are reprinted in Dalibor quite frequently, but articles from The Times are rarely to be seen.

Once again, Dvořák's image as a nationalist was the issue at stake in these choices, as indicated in a letter that the composer wrote to Novotný in April of 1885, following the London premiere of his Symphony in D minor, Op. 70.Footnote 31 Of Bennett's assessment, Dvořák writes: ‘as always [he] has understood my work completely’.Footnote 32 Bennett repeatedly drew attention in his articles to the ‘nationalist’ elements in Dvořák's music, and his review of the D-minor Symphony is no exception. In Bennett's view, every movement of the work bears the mark of its nation, and he even goes so far as to dub the piece ‘Slavonic’ Symphony – a remark that Czech critics were doubtless keen to reprint.Footnote 33 Whereas Dvořák approves of Bennett's critique, he expresses a sense of frustration over Hüffer's review: ‘four years ago, [Hüffer] declared my Sextet [Op. 48, 1878] to be a masterpiece and original, and now he finds fault with my so-called Slavic originality. In short, this is complete nonsense, and it is not worth discussing any further’.Footnote 34 These words were provoked by Hüffer's review of the Symphony, which begins with the following statement:

In [Dvořák's] earlier orchestral works, the Slavonic Rhapsodies, and even in parts of the first symphony, the popular songs and dances of his country played an important part, and gave, as it were, their typical cachet to his imaginings. We pointed out more than once that, charming though these reminiscences might be, they did not suffice to establish the reputation of a great composer, that to prove himself such Herr Dvorak [sic] would have to sink his nationality for a season and be his own individual self. In his D minor symphony he has certainly done the former. With the exception, perhaps, of some rhythmical idiosyncrasies in the scherzo, and again in the last movement, there is nothing that a German or an Englishman might not have written as well as a Slav. Unfortunately, however, the individuality here is not sufficiently strong to atone for the loss of national colour.Footnote 35

Even Hüffer's decision to address the composer as ‘Herr Dvorak’ was likely to stir contentions – both because of the misspelling of Dvořák's surname and the German honorific, implying to Czech readers that Dvořák was somehow presenting as a German composer when abroad – much less the critic's comments on the symphony's lack of substance when stripped of its so-called ‘national colour’. As expected, Hüffer's critique of the D-minor Symphony was excluded from Dalibor. Clearly, Dvořák was determined to share with his Czech audiences those articles that portrayed him unequivocally as a Czech composer writing nationalist works and to suppress reviews that might contradict that image.

Czech critics assisted Dvořák in highlighting the positive aspects of his English reception. They frequently teased out the most enthusiastic parts of a given review and withheld any sections that were likely to cause offence, even when Dvořák did not ask them to do so.Footnote 36 For example, Hüffer's largely complimentary article on Dvořák's Stabat Mater, Op. 58 (1876–77) is reproduced almost in its entirety in Dalibor, translated by Zubatý, but the paragraph in which Hüffer criticizes Dvořák's ‘cavalier’ approach to declamation is conspicuously absent, as is Hüffer's assertion that the piece lacks the kind of passion that can be heard in the sacred works of Beethoven and Berlioz.Footnote 37 Based on the existing correspondence, it would appear that Dvořák did not have a hand in orchestrating these omissions. Likewise, Dvořák does not give any particular directions to Zubatý, when sending along the review of The Spectre's Bride that was published in the London Standard.Footnote 38 Zubatý, however, takes great liberties with his translation, only including the portions of the original review that report on the warm reaction of the audienceFootnote 39 and omitting the sentences that address the ‘repulsiveness’ of the cantata's storyline.Footnote 40 These examples show that Dvořák's contacts in Prague did much of the excerpting themselves, and they were important allies in presenting Dvořák to Czech readers in the best possible light. The foreign press – especially the long-standing and well-established English press – was manipulated in this way for home consumption. Though acting in concert with a network of critics, editors and translators, it was ultimately Dvořák who took the initiative and sought to micromanage his public image in the Czech lands from the distant shores of England.

Such involvement with the Czech press was rare for Dvořák. He did not see to it that positive Austrian and German critiques were reprinted in Czech periodicals,Footnote 41 nor did he send any of the highly favourable American reviews of his music back home for re-publication. It seems to have been with good reason that he failed to take such an active part in these other contexts. Czech newspapers and journals tended to have correspondents in German-speaking Europe, thereby eliminating the need for Dvořák to act as his own manager there. Additionally, Dvořák's American sojourn during the 1890s – though of much longer duration than any of his other travels – received far less press coverage in the Czech lands than his earlier trips to England;Footnote 42 this is likely because Dvořák's reputation at home was well-established by then, and perhaps he no longer felt the need to consolidate it. Dvořák's apparent efforts at self-promotion from England were, thus, quite exceptional, but not entirely uncharacteristic of him. After all, Dvořák read reviews of his music on a regular basis throughout his career and was not indifferent to the opinions of his critics, be they Czech or foreign. His extensive revisions to the opera Dimitrij, Op. 64 (1881–82, rev. 1894) were triggered in large part by Eduard Hanslick's assessment of the work, and Dvořák's willingness to take advice from others was looked upon as a tremendous asset by many critics writing for Dalibor. He is praised several times on the pages of the journal for the ‘self-criticism’ and ‘self-denial’ that he showed in undertaking a complete rewrite of his early opera Král a Uhlíř, Op. 14 (The King and the Charcoal Burner, 1871, rev. 1874) for the benefit of performers and audiences at Prague's Provisional Theatre.Footnote 43 Alan Houtchens expresses it well, when he writes that ‘being very sensitive to fluctuations in public taste and attentive to critical reviews of his compositions, [Dvořák] was instinctively motivated by healthy doses of pragmatism and even opportunism’.Footnote 44

‘With feelings of deep gratitude’: Universality, Self-Promotion and the English Dedication of Dvořák's Hymnus

One of the clearest examples of the pragmatism that Houtchens describes is the way in which Dvořák handled performances in England of his cantata Hymnus. Although this work is largely unknown today, its Prague premiere in 1873 was a pivotal moment for Dvořák, and for several decades, Czech critics would continue to remind their readers in Prague of the event, not only because of its personal significance to Dvořák, but also because of its exceptionality in terms of scale and spectacle.Footnote 45 Hymnus further struck a chord with Czech audiences in 1873 owing to its nationalist content, for which there was a real appetite at that time. The text is taken from an epic poem in rhymed verse entitled Dědicové Bílé hory (Heirs of the White Mountain), written in 1868 by Czech poet Vítězslav Hálek. The White Mountain, to which the title refers, is situated on the Western outskirts of Prague, and it was the location of a crucial battle that the Czechs fought and lost against the Bavarian and imperial troops on 8 November 1620. This military defeat had far-reaching consequences for the Czechs, bringing about a loss of independence and a nearly three-hundred-year period of Austrian rule. A critical event in Czech history, White Mountain was explored by various writers during the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the ‘national revival’ (národní obrození) was gaining momentum, and Hálek's allegorical drama conforms to this larger trend. Set in 1640 – some 20 years after the pivotal battle took place – Hálek's drama features both historical and fictional characters, who describe the repercussions of White Mountain to a blissfully ignorant individual, identified as the ‘genius’. After bearing witness to the atrocities that resulted from the lost battle, the characters join together in the concluding Hymnus, which, while acknowledging past sorrows and suffering, is ultimately meant to convey a sense of hope for a brighter future. It is only this very last part of the drama that Dvořák set to music in his cantata. The text of Hymnus ends with declarations of love for the mother country, including the line: ‘Let us love her, as no nation has loved before.’Footnote 46 Appropriate to the text, Dvořák's Hymnus begins softly and builds to a bombastic climax. By choosing E-flat major as the tonic key for a composition that expresses heroic resolve, Dvořák seems to be tapping into a tradition that dates back to Beethoven, and one that also included more contemporaneous composers like Wagner. In its original form, Dvořák's Hymnus calls for an orchestra, with a large complement of brass and percussion instruments, and it was premiered by a 250-member chorus. Though the orchestral writing would later be reduced, such performing forces were massive by late nineteenth-century Czech standards, making the work sound like a communal nationalist plea.

The earliest Prague performance of Hymnus was also set against a very particular political backdrop, too complicated to be discussed at length here.Footnote 47 In short, the work was written soon after a campaign had been mounted – with the support of Cisleithanian Minister-President Karl Sigmund Hohenwart – that sought to grant the Czechs greater independence within the Habsburg Empire. Even though Minister-President Hohenwart was initially disposed to appease the Czechs and promised to enable them to attain a kind of ‘separate status’ with respect to the then Austro-Hungarian Empire, thereby increasing Czech autonomy, external pressures led Hohenwart to go back on his word; and these events, which unfolded in 1871, were widely seen as a devasting blow to the Czech national cause.Footnote 48 The Hymnus premiere took place in early 1873,Footnote 49 when the abortive Hohenwart episode was still fresh in people's memories, and the piece likely fared so well with audiences at that time because it seemed to encapsulate what everyone was feeling in the aftermath of this recent Czech defeat.Footnote 50

While the Prague premiere marked Dvořák as a fighter for the Czech cause, the work's English afterlife is equally intriguing and speaks to Dvořák's role as his own strategist. In a letter written in March of 1884 and addressed to Czech composer and conductor Karel Bendl, who had directed the Prague premiere of Hymnus, Dvořák describes a London performance of his Stabat Mater: ‘imagine the New Town TheatreFootnote 51 [in Prague] about five times larger than it is’, he writes, ‘then you will know what Albert Hall is like, where 10,000 people listened to Stabat Mater and 1,050 musicians and singers played and sang [it], accompanied by that colossal organ!’Footnote 52 Dvořák's enthusiasm is palpable, as he marvels at the kinds of performing forces that were available to him in England – ones that were unimaginable in the Czech lands. When more works were solicited from Dvořák for performance in that country, Hymnus was a logical choice. Having been premiered at a concert that broke Czech records in terms of grandeur, the work must have seemed uniquely suited for performance in England – a place with a rich choral tradition. That Hymnus was given an English premiere in the mid-1880s is not unusual; much more puzzling is the English dedication that the piece now bore.

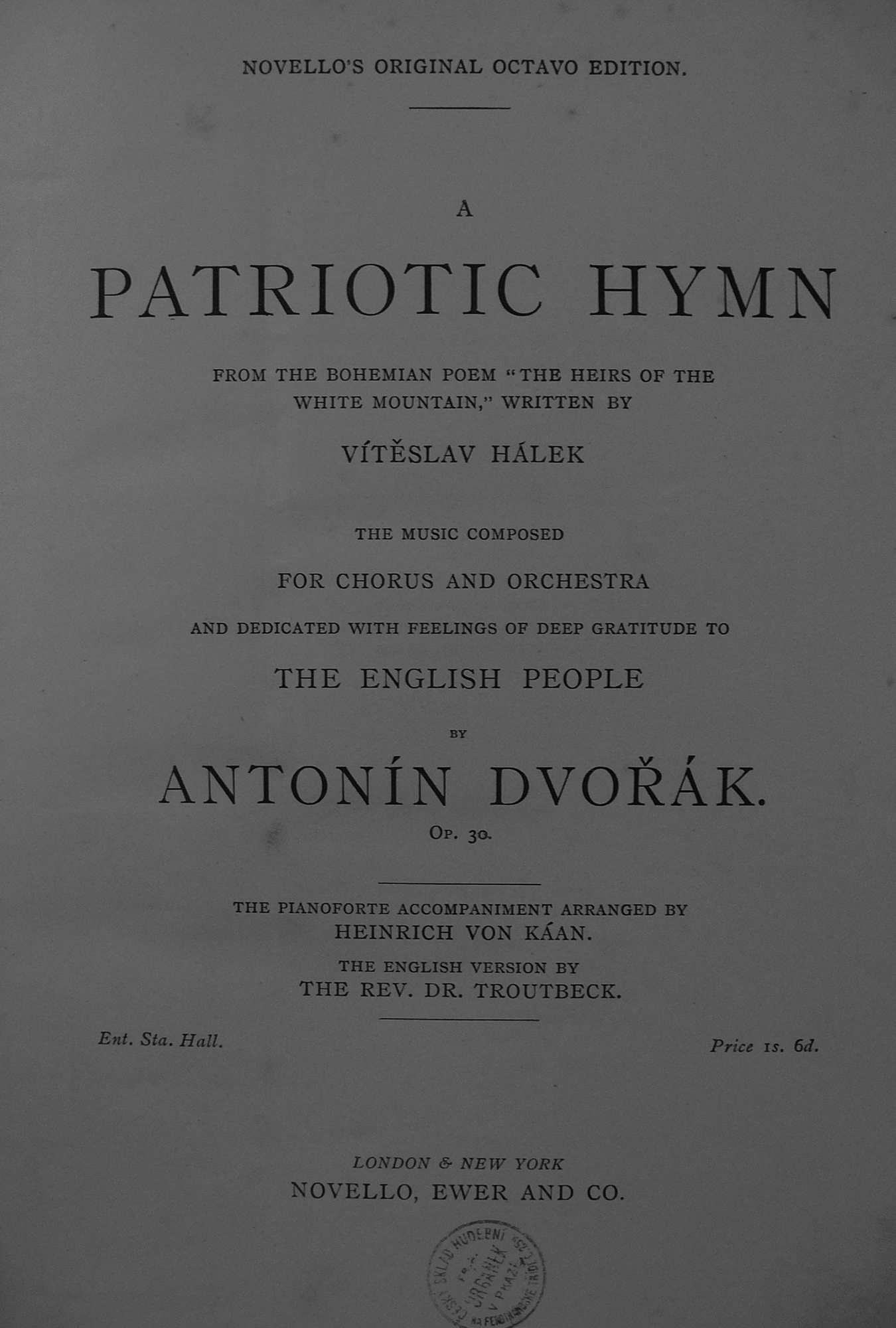

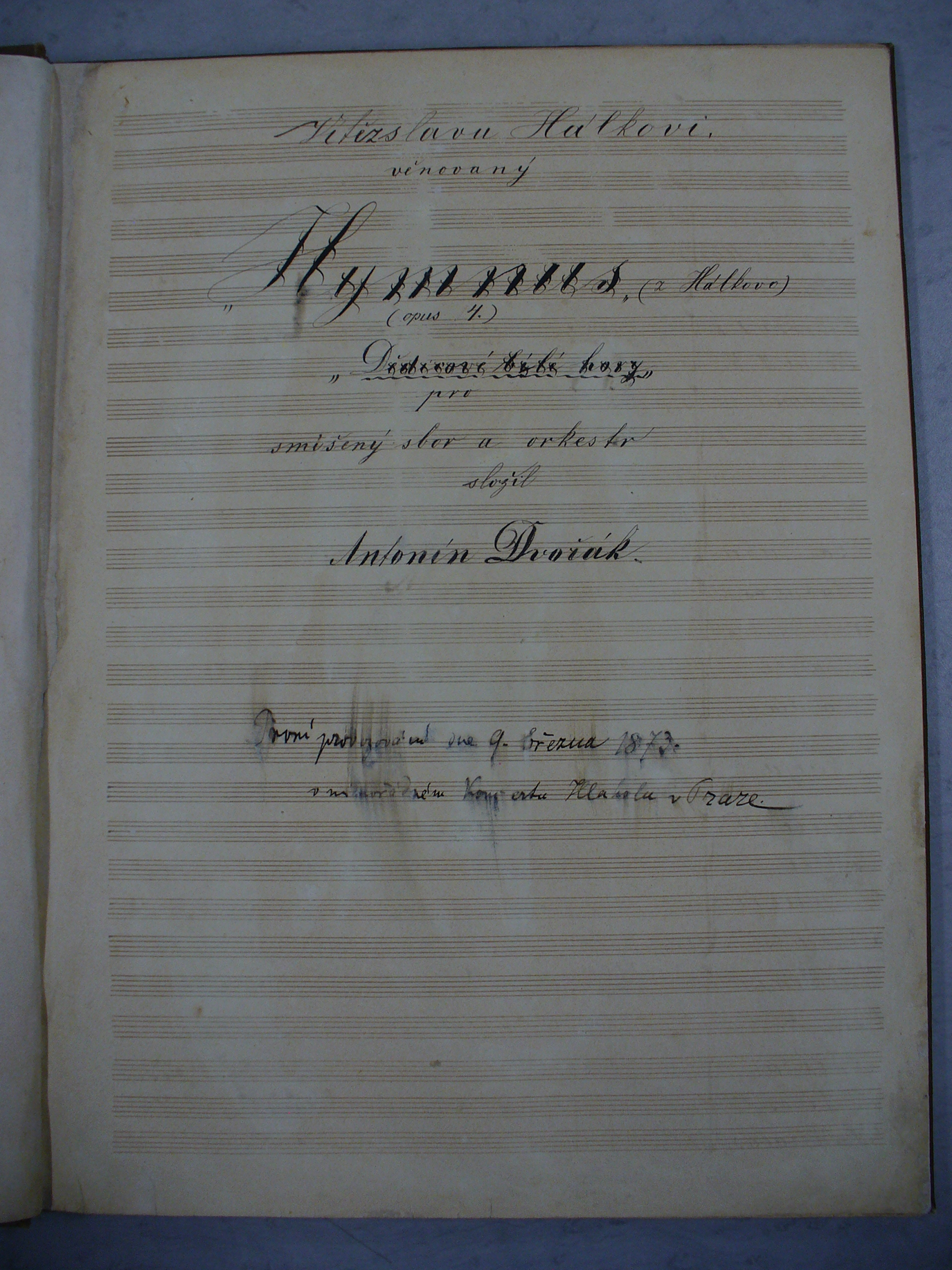

Given the references to seventeenth-century Czech history in its text and the heated political circumstances of its Prague premiere, it is surprising that Dvořák dedicated Hymnus ‘with feelings of deep gratitude to the English people’, when it was published by Novello (Fig. 1). Two other aspects of the dedication are striking. First, the dedication was made in 1885, a full 12 years after the work was premiered. Emily Green observes that it was rare during the nineteenth century for dedications to be added to pieces in repeated printings, and if any change was made, dedications tended to be removed over the course of time.Footnote 53 Even though Hymnus did not appear in print before 1885, the English dedication must be counted as an addition or rather a change of mind because Dvořák initially dedicated the work to the author of its text: Vítězslav Hálek; the poet is clearly identified as the dedicatee, in Dvořák's hand, at the top of the second page of the original autograph score (Fig. 2). Dvořák was able to withdraw the dedication to Hálek likely because few people were aware of it, since the work still had only existed in manuscript up to that time, and the poet had passed away in 1874.

Fig. 1 Cover of the published Novello score, showing Dvořák's dedication. Source: Antonín Dvořák, A Patriotic Hymn (London: Novello, 1885)

Fig. 2 Dvořák, Hymnus, second page of the original autograph score. English translation: “Dedicated to Vítězslav Hálek, Hymnus (opus 4) (from Hálek's) “Heirs of the White Mountain” for mixed chorus and orchestra, composed by Antonín Dvořák (smudged content: First performed on 9 March 1873 at the extraordinary Hlahol concert in Prague). Used with the permission of the Antonín Dvořák Museum, National Museum, Prague (1436)

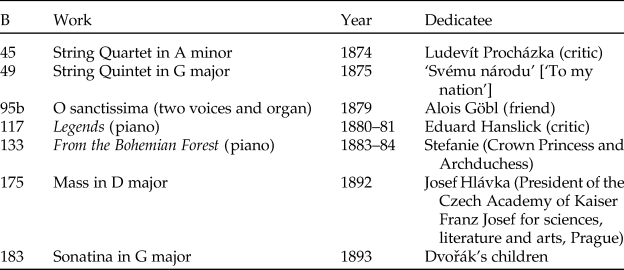

The second aspect that makes this dedication unusual is that it is directed at a people. Composer-to-composer dedications were common during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 54 Dvořák, however, dedicated works to only four composers: Karel Bendl, Johannes Brahms, Pablo de Sarasate and Josef Hellmesberger (see Table 1). Other Dvořák dedicatees included critics, such as Ludevít Procházka and Eduard Hanslick; people in positions of power, such as the Imperial Princess Stefanie and Josef Hlávka, the president of the Czech academy of arts, sciences and literature; and Dvořák's friends and family members (see Table 2).

Table 1 Dvořák's Dedications to Composers. Source: Jarmil Burghauser, Antonín Dvořák: Thematický katalog, Bibliografie; Přehled života a díla [Thematic catalogue, bibliography; survey of life and work] (Prague: Bärenreiter Editio Supraphon, 1996).

Table 2 Some of Dvořák's Other Dedications. Source: Jarmil Burghauser, Antonín Dvořák: Thematický katalog, Bibliografie; Přehled života a díla [Thematic catalogue, Bibliography; Survey of life and work] (Prague: Bärenreiter Editio Supraphon, 1996).

Otherwise, the vast majority of Dvořák's dedicatees were performers.Footnote 55 Thus, the dedication to the English people is anomalous. The only comparable dedication is the inscription ‘to my nation’ that appears on the printed score of Dvořák's String Quintet in G major, Op. 77 (1875). In contrast to Hymnus, the String Quintet has no obvious elements that critics might call ‘Czech’; in fact, the very genre of the string quintet likely would have been perceived as rather ‘unCzech’ at a time when Bohemian composers, who wanted to make some kind of nationalist statement, tended to favour large-scale genres, primarily opera. Also, Dvořák's dedication of the String Quintet contains the wording ‘to my nation’ and not ‘to the Czech people’ – a subtle, but important distinction. The notion of dedicating a work to a people, as Dvořák does with his Hymnus, has greater specificity, and it has less of an explicitly partisan orientation than nation would have had. Since Dvořák encountered English people primarily as audience members at concerts of his music during his trips to England, this phrasing implies that the dedication can somehow be related to Dvořák's English reception.

Emily Green proposes that, among other functions, dedications served as public gifts that required reciprocation.Footnote 56 She goes on to point out that dedications did not necessarily reciprocate dedications, but could be offered in return for other types of gifts, like good reviews. This idea of dedication as a form of gift-giving seems to apply well to Dvořák. One cannot help but notice that Dvořák's dedication of his D-minor String Quartet, Op. 34, to Brahms came in 1877, just after Brahms had introduced Dvořák to the Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock. Similarly, Dvořák dedicated his Wind Serenade, Op. 44, to critic Louis Ehlert in 1878, when Ehlert's favourable article on Dvořák was still hot off the press. In both cases, Dvořák's dedications can be understood as gestures of reciprocation – as Dvořák's way of recognizing the part that these men played in the furthering of his career. That the English dedication of Hymnus contains the words ‘with feelings of deep gratitude’ implies that it too was meant as a gift. Dvořák may have wished to thank the English in a public way for their enthusiastic reception of his music. Although Dvořák's works were heard in England as early as 1879, he really burst onto the English scene in 1884, the year in which he visited the country for the first time. As stated above, eight more visits to England would follow, most of them during the 1880s, and the dedication of Hymnus in 1885 came at about the time when Dvořák had reached the peak of his success there.

Dvořák was the first Czech composer to receive considerable recognition abroad, and the desire to give credit to English audiences is understandable; why Dvořák would do it with this particular piece is less clear. An assumption that holds true for any dedication is that the dedicated work should be well liked by the dedicatee. Hymnus was performed at St James's Hall in London, in English translation, only after it had been published by Novello; this means that the dedication was in place before Dvořák knew how Hymnus would fare with English audiences and critics. If the reviews that were published following the 1885 London premiere are any indication, the dedication seems to have been somewhat miscalculated. According to the critic writing for the Morning Post:

the music is meritorious and effective, but does not belong to the category of inspired creations, and the difficulties required to be conquered before an adequate representation of the author's ideas can be fully realised are more than the generality of choral societies will likely care to overcome for so small a result as is likely to follow.Footnote 57

A similar assessment is given in The Monthly Musical Review: ‘the performance was not very good, but the work itself is too complicated in construction, and therefore fails in the effect which is aimed at’.Footnote 58 The English reviews were not all bad – the reviewer for The Times reports that the work was ‘favourably received’Footnote 59 – however, these articles do call into question Dvořák's decision to dedicate Hymnus, rather than another piece.

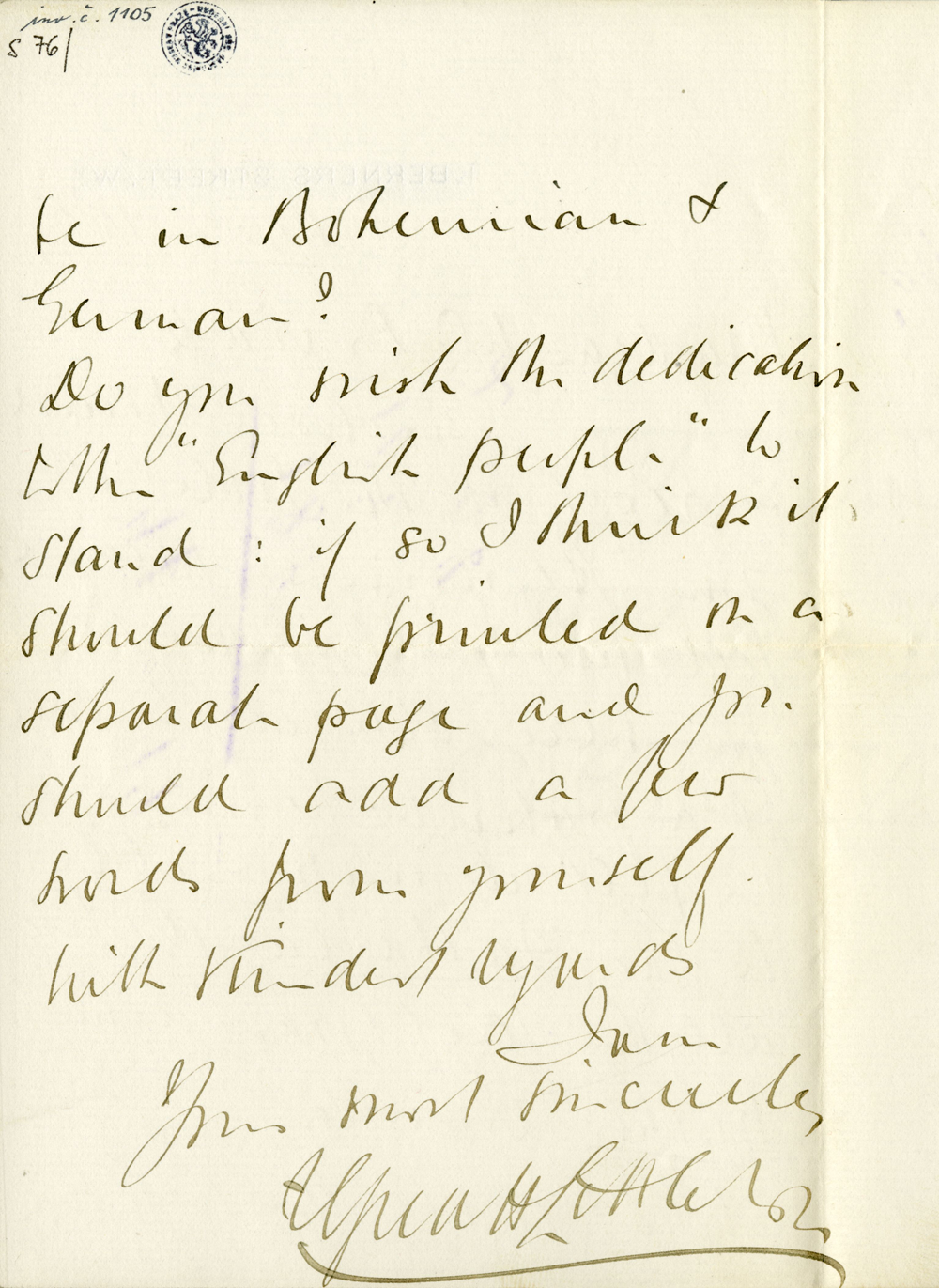

One explanation for the choice is simply that Hymnus was Dvořák's first English publication. Dvořák may have wanted to include a nod to the English people on the title page of his first printed Novello score, regardless of which piece was being published. Another possibility is that this gesture of gratitude was orchestrated by someone else. David Beveridge suggests that the English dedication was in fact publisher Alfred Littleton's idea and Dvořák acceded to it without giving much thought to its appropriateness.Footnote 60 As evidence for this interpretation, Beveridge cites a letter from Littleton to Dvořák dated 2 February 1885: ‘do you wish the dedication to the “English people” to stand: if so, I think it should be printed on a separate page and you should add a few words from yourself’Footnote 61 (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Letter from Alfred Littleton to Dvořák (2 February 1885). Used with the permission of the Antonín Dvořák Museum, National Museum, Prague (S 76/1105)

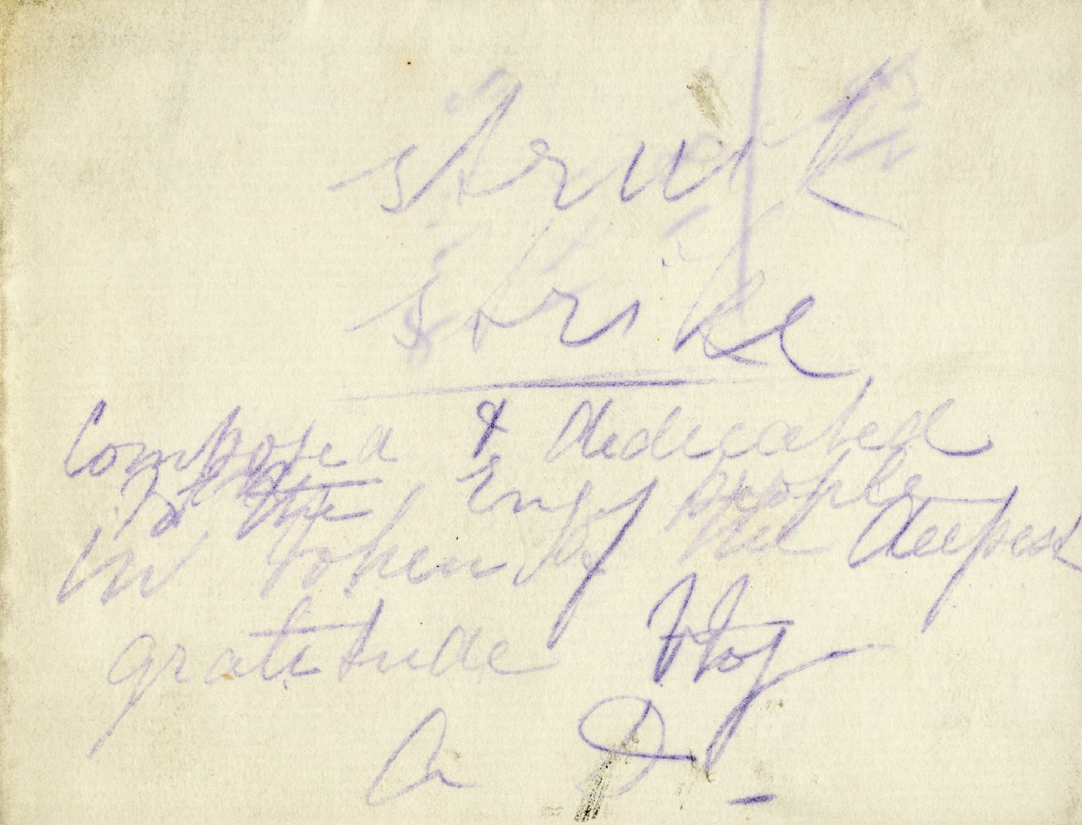

Littleton's request for Dvořák to add a few of his own words has led Beveridge to suspect that the idea of the dedication did not come from Dvořák and that the composer was merely asked to confirm it and help with the wording. On the back of the letter from Littleton, Dvořák begins to draft out the dedication, jotting down the words ‘composed and dedicated to the English people in token of my deepest gratitude’ (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Dvořák drafts out his English dedication on the back of Littleton's letter. Used with the permission of the Antonín Dvořák Museum, National Museum, Prague (S 76/1105)

Though it would later be edited out, Dvořák's statement that Hymnus was ‘composed’ for the English people is extraordinary, since he wrote the work in the early 1870s at a time when he still had no hope of it being performed outside of the Czech lands. What Dvořák is probably alluding to here are his revisions. Before submitting it to Novello for publication, Dvořák toiled over the score for the better part of three months.Footnote 62 This was not the only time that Dvořák revised Hymnus; he had already reworked it extensively in 1880. Thus, the 1885 version might be understood as a new piece, requiring a fresh dedication to reflect its changing audience.

Dvořák may have altered the music of Hymnus, but – at least to the Czechs – its text remained the same and the overwhelming impression from the 1873 premiere was not easily erased. These factors indicate that the dedication of Hymnus was more deliberate than the theories presented thus far would suggest. After all, Dvořák's correspondence shows him to be a tenacious individual, not easily bullied into making a dedication that he did not want to make.

A passage taken from the anecdotes of Zubatý, who accompanied Dvořák on one of his trips to England, gives some insight into this issue. Granted, Zubatý wrote these anecdotes in 1910 – a full 25 years after the events being described had occurred and against the backdrop of what would soon become a rather heated debate in the Czech press over Dvořák's legacy. Even so, Zubatý offers a unique perspective on Dvořák's patriotism when abroad:

Dvořák was Czech with every breath, even if he had an aversion to all loud displays of patriotism … It is interesting and instructive that the same Dvořák, who was the sworn enemy of empty radicalism, could not help but conduct himself as a Czech, body and soul, when he was abroad … Upon arriving in London [in 1885], Dvořák was surprised by posters, advertising that ‘Herr Anton Dvořák’ will conduct his new symphony on this and that date. Dvořák immediately insisted that he be addressed in Czech on the posters as ‘pan Antonín Dvořák’. The consortium of German artists invited him at that time to an evening [celebration] being prepared in his honour; similar celebrations had been arranged in the past for Bülow, Richter and others. With many thanks, Dvořák refused, explaining that he is not a German artist.Footnote 63

The ‘empty radicalism’ referenced in this excerpt could perhaps be understood as an oblique reference to Richard Wagner, whose extreme egotism undoubtedly hovered over the ways in which composers spoke about themselves in the 1880s. More explicitly, however, Zubatý contends here that Dvořák was more comfortable giving voice to his ‘Czechness’ in LondonFootnote 64 than in Prague, and the English dedication of Hymnus might be seen as a manifestation of this tendency.

Whether referring to music performed at home or abroad, by the mid-1880s, Dvořák spoke of art as lying outside the domain of politics. In a letter to Simrock dated 10 September 1885, Dvořák writes: ‘what do we have to do with politics; let us be glad that we can devote ourselves to the service of beautiful art!’Footnote 65 Given Dvořák's attitude as revealed in this letter, the dedication of Hymnus to the English people might be interpreted as an attempt to make the work's message less obviously Czech and more universal – a patriotic plea to which any nation could relate. In some ways, the Czech reviews from 1873 already suggest that Hymnus would lend itself well to such a goal. Most Czech critics discuss the work's ‘patriotic enthusiasm’ or ‘patriotic fervour’, without making specific reference to its ‘Czechness’.Footnote 66 The writer of one of Dvořák's obituaries would even claim that Hymnus was not Czech enough.Footnote 67 Perhaps as a means of deflecting attention away from its specifically Czech origins, Novello added ‘Patriotic’ to the title of Hymnus for its English publication.Footnote 68 If universality was Dvořák's aim, the English reviews indicate that he had mixed success. The critic writing for The Graphic in 1885 states that ‘as music, [Hymnus] cannot be considered apart from its essentially nationalistic surroundings’Footnote 69 and a reviewer for The Musical Times writes in 1886 that ‘the work is so thoroughly national in feeling as to appeal only to the composer's own countrymen’.Footnote 70 One critic offers a different perspective, stating that ‘[the voices] rang out in the unaccompanied phrases at the close with a richness of quality and full volume which would have extorted the admiration of a Yorkshireman’.Footnote 71

Irrespective of Dvořák's exact intent, the English dedication of Hymnus did serve as the inscription for a public gift. Whether it was meant as a response to the enthusiasm that English audiences and critics had shown for Dvořák's music or as a gesture of thanks for his first English publication, Dvořák certainly had reason to feel ‘deep gratitude to the English people’. Perhaps the gift lay in Dvořák's attempt to take a nationalist piece, associated with a politically charged occasion, and refashion it for an entirely new context, thereby infusing it with a greater degree of universality. Some gifts are taken by the receiver and yet never quite relinquished by the giver.Footnote 72 This is especially true for a musical composition, because no matter who it is dedicated to, it still somehow belongs to the composer. Thus, the true recipient of the dedication – the one to benefit most from the giving – could be Dvořák himself. By dedicating it to the English people, Dvořák may have used Hymnus as a vehicle to raise awareness in England of Czech national aspirations, while simultaneously drawing attention in the Czech lands to his personal successes abroad. The role of the English can be compared to the part of the ignorant ‘genius’ in Hálek's allegory, to whom seventeenth-century Czech history is told. Seeing the past sufferings and hopes of the Czechs, as expressed in the Hymnus text, might have been intended to inspire compassion and lead the English to make certain connections to contemporary Czech politics. As a desirable ‘by-product’, the dedication also allowed Dvořák to let Czech audiences know about the kind of following he had gained in England – one that would warrant expressions of deep gratitude. Foreign acclaim, or indeed affirmation, was typically held in high regard among the Czechs at this time; in many cases, it was only after works by Czech composers achieved recognition on foreign stages that Czech audiences really started to take notice of them.Footnote 73 In light of these realities, the dedication was significant because of the message it conveyed about Dvořák to audiences at home, and the attendant elevation in status that it would confer on him.

Conclusion: Rethinking Dvořák's Role in Constructing his Public Image

The Hymnus dedication, taken together with Dvořák's tendency to determine which English reviews would appear in the Czech press, shows Dvořák to be rather deliberate in the way that he constructed his public image. This aspect of Dvořák's career has remained largely unexplored for two reasons.Footnote 74 The first has to do with prevailing perceptions of Dvořák himself. The image of Dvořák as a naïve composer – one who was dependent on the generosity of others for his success – has become ingrained. His dread of making public appearances and speeches was well known to his acquaintances, and Czech critics often make mention of his humility in their reports on his triumphs abroad.Footnote 75 Ironically, Dvořák's humble and unenterprising nature is emphasized in one of the very articles that he sent home for reprinting. Seeking to provide some background information on the composer before proceeding to review his Stabat Mater, the critic for The Birmingham Daily Post writes:

It would be superfluous on the present occasion … to enter into biographical details. It will suffice to remark that Dvořák is evidently as modest and retiring as he is gifted; and that, but for the friendly intervention of Johannes Brahms, who was quick to recognise a kindred genius in the work of the Czech composer, and spared no pains to drag him from his comparative obscurity, Anton Dvorak's [sic] music might still have been a sealed book to the mass of music lovers among whom it has already created such a furore.Footnote 76

In particular, the phrasing that Brahms had ‘to drag him from his comparative obscurity’ implies that Dvořák was somehow disinclined to enter into the public sphere and pitch his music to a wide audience.

The second reason why Dvořák's role as strategist rarely comes to light is broader. Dana Gooley explains that, whereas eighteenth-century composers were often shameless in their efforts to appease their aristocratic patrons, self-promotion was frowned upon during the nineteenth century, as it seemed to run counter to Romantic ideology.Footnote 77 People liked to believe that composers’ successes were the spontaneous outcome of their talents alone, rather than the result of careful planning and calculated activity. As Martha Woodmansee observes, these Romantic notions of the ‘artist’ can be traced at least as far back as 1785 when German philosopher Karl Philipp Moritz wrote his seminal essay,Footnote 78 arguing that art has ‘intrinsic’ value that is entirely independent from external realities and contexts.Footnote 79 Taking art out of the realm of the mundane, Moritz writes that the beautiful object ‘constitutes a whole in itself’ and ‘yields a higher and more disinterested pleasure than the merely useful object’.Footnote 80 The implication is that the value of art is self-apparent, and doing anything to promote it would undermine that value. Later taken up by other individuals, including Immanuel Kant, these ideas shaped perceptions of the artist's role in society and initiated changes to the social and economic situation of the arts.

In spite of this shift in thinking, recent scholarship has shown that throughout the nineteenth century self-promotion and media manipulation were quite common, if covert in order to avoid the stigma associated with these pursuits. David Larkin, for example, draws attention to the various strategies Franz Liszt used during the 1850s to ‘massage critical opinion’ of his works and ‘spin’ the media in his favour.Footnote 81 Yet, Liszt understood that he needed to be discreet in his approach. If composers took too much of an active role, they ran the risk of being accused of opportunism. William Weber points out that musical opportunism – the ability to spot and take effective advantage of an opportunity – was essential for professional musicians during this time and simultaneously scorned by society at large. As Weber puts it,

the most basic act of the opportunist was self-display – indeed, self-promotion. On a certain plane, an aspiring musician had to make claims for him or herself in ways that went beyond conventional music-making … But self-promotion was often interpreted as going against social norms, either within the music profession or society itself.Footnote 82

Such thinking seems to have been just as pervasive among the Czechs during the nineteenth century as it was elsewhere; on occasion, Dalibor was used as a platform from which critics warned musicians of the dangers of becoming overly focused on material concerns. In an article from 1879 on art and education, for instance, critic Josef Srb Debrnov detects a general lack of true appreciation for music in the Czech lands and attributes this, in part, to materially minded musicians – ones, who, in his phrasing, ‘revel in their own glory and self-conceit’, rather than striving for ‘the ideal in art’.Footnote 83 As much as composers sought to give the impression that they paid little heed to these ‘material gains’, as Srb Debrnov describes them, they still had to contend with the day-to-day realities of survival. These matters were very real for Dvořák, who had a wife and six children to support. When negotiating his salary with New York Conservatory head Jeanette Thurber in April of 1894, Dvořák signals both his need and his reluctance to behave in a mercenary fashion: ‘the necessities of life go hand in hand with Art’ he writes, ‘and though I personally care very little for worldly things, I cannot see my wife and children in trouble’.Footnote 84

In keeping with these established social norms, Dvořák sought to assure the Czech public of the purity of his motives – that he was in fact doing everything solely for the purpose of putting the Czechs in the international spotlight. Behind the scenes, however, he was a shrewd businessman. Dvořák's plea to Thurber is reminiscent of countless exchanges that he had with the Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock in the hope of arriving at a lucrative deal on the publication of his music. Dvořák proved to be savvy not only in his dealings abroad, but also in his interactions with his compatriots. His letters from England written during the mid-1880s reveal that he understood the importance of forming connections with prominent Czech critics and promoters, cultivating and maintaining his personal image at home, using the Czech press – with its considerable local reach – to his advantage and conforming to the concerns of his Czech audience. In so doing, Dvořák shows – perhaps more clearly than those who were more publicly outspoken – the ways in which composers of the nineteenth century needed to negotiate between the demands of self-promotion and the need to maintain and perpetuate the notion that ‘art’ exists in an elevated plane – in a realm that lies beyond the concerns of everyday life. Moreover, by seeking to bring a distinctly Czech persona to the fore, Dvořák demonstrates that he was keenly aware of what Michael Beckerman calls ‘the public-relations aspect of nationalism’.Footnote 85 Dvořák's remark, then, to Kovařík, suggesting that he was content simply to let the music ‘speak for itself’, does not tell the whole story.