Introduction

Globalization has become highly contested in many countries. Immigration, free trade, and European integration are salient issues and divide citizens into supporters and opponents of globalization. We have seen this with Brexit in the United Kingdom, with the election of Donald Trump in the United States and in the presidential conflict between Emanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen in France to name but a few of the most well-known recent manifestations of this conflict. Political sociologists discuss ‘a new structural conflict’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) or ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2017), pitting ‘cosmopolitans against nationalists’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012), ‘winners against losers of globalization’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016) or ‘cosmopolitans against communitarians’ (Teney et al., Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2014; De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürnforthcoming). Whether conflicts over globalization amount to a cleavage is imperative, because it has important implications for democracy. Cleavages structure democratic politics over long periods of time. They enable and channel citizen participation and mobilization in democratic politics, and facilitate compromise in policy-making (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). In a sense, cleavages allow deeply rooted societal conflicts to be played-out and reconciled in a peaceful, democratic way (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990).

Many studies, notably those cited above, focus on the positioning of political parties and public opinion. They document the organizational and structural components of the cleavage, respectively. Yet, the important third dimension of cleavage formation – the normative dimension – has received comparatively little attention. To speak of a full cleavage, an organizational dimension, structural dimension, and normative dimension of conflict need to align (Mair, Reference Mair2005). That is, citizens on each side need to be represented by political parties or other collective actors. The connection between them is facilitated by ideology and collective identity. The class cleavage did not become a full cleavage until liberalism and socialism were fleshed out as full-blown ideologies to make sense of a range of issues and mobilize citizens through simplified calls for ‘freedom’ or ‘equality’. To investigate this elusive normative component of the alleged new cleavage on globalization, this contribution sets out to map the existence of ideologies of globalization.

Beyond investigating the existence of a cleavage, the study of ideologies of globalization is paramount to understand how globalization itself as a process is developing. While globalization is driven by technological progress that facilitates ever faster, easier, cheaper, and more far-reaching human interaction across borders, it is not an automatic process. In the words of Manfred Steger:

… globalization was never merely a matter of increasing flows of capital and goods across national borders. Rather, it constitutes a multidimensional set of processes in which images, sound bites, metaphors, myths, symbols, and spatial arrangements of globality were just as important as economic and technological dynamics (Reference Steger2013: 221).

Thus, ideologies advocating or inhibiting globalization may have a major effect on its course. A dominant ideology that promotes globalization is likely to stimulate further interaction across borders. Similarly, ideologies skeptical of globalization may contribute to altering or halting its development. The question thus becomes pertinent whether ideologies underpin the globalization conflict, not only for the sake of understanding democracy in the 21st century but also for understanding the development of globalization itself.

Ideology may exist in a psychological sense (Leader Maynard and Mildenberger, Reference Leader Maynard and Mildenberger2016), that is, as a set of values and identity perceptions in the minds of citizens. The question then is: how did such ideologies get there? This contribution focuses on the making of – or constructing of – ideologies on globalization. Drawing on the seminal work of Michael Freeden (Reference Freeden1996: 15), I conceive of ideologies as ‘… organized, articulated, and consciously held systems of political ideas incorporating beliefs, attitudes, and opinions’. Freeden advocates a morphological approach to the study of ideologies, that is, an approach primarily focused at mapping the relationship between linguistic concepts in public discourse. Public statements such as: ‘This is what liberty means, and that, is what justice means' (Freeden, Reference Freeden1996: 76, emphasis in original) are the core building blocks of ideology. The making of ideologies thus consists of successfully linking various concepts to calls for action in the public sphere. As argued by Heywood, ‘Everyday language is littered with terms such as “freedom”, “fairness”, “equality”, “justice” and “rights”’ (Reference Heywood2017: 1). Successfully defining what liberty, justice, and other concepts mean or imply is called ‘decontestation’. The more a justification becomes associated with a particular call for action, the more decontested it becomes. Socialists have been highly successful in linking concerns for equality with state-run policies of redistribution just like liberals have been highly successful in justifying a retraction of the state from the economy and an assertion of rights at the level of human individuals as the pursuit of freedom. In morphological terms, ‘freedom’ and ‘retraction of the state’ become part of a discursive formation of political concepts. Operationally then: ‘ideologies are groupings of decontested political concepts’ (Freeden, Reference Freeden1996: 82).

This study sets out to systematically investigate whether such groupings of decontested concepts can be identified in globalization discourse, and what they look like. Extant studies on ideologies of globalization build mostly on anecdotal qualitative evidence, constructing ideal-typical ‘truth claims’ of what these ideologies look like. While we thus have indicative ideas about what globalization ideologies look like, we have little systematic quantitative evidence to date (but see Steger et al., Reference Steger, Goodman and Wilson2013). Without further systematic rigorous analysis, it is hard to assess how well these ideal types reflect actual public discourse on globalization. This study therefore sets out to systematically analyze public discourse on globalization in a wide variety of locations, on a range of different issues. It rigorously analyzes how and to what extent concepts are linked to different calls for action, thus mapping the ideological space and degree of successful decontestation. It presents an original data set of 11.810 political claims on migration, climate change, human rights, trade, and regional integration made in Germany, the United States, Mexico, Poland, Turkey, the European Parliament (EP), and the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), between 2004 and 2011. The analysis shows that calls for opening or closure of borders are largely unrelated to expressions of globality. Globalization discourse thus unfolds in a two-dimensional ideological space. Subsequently, I map where justificatory concepts and their moral foundations are located in this two-dimensional space and measure whether they are successfully decontested. While many concepts remain essentially contested, the analysis reveals the making of four distinct ideologies. One of them is a rather thick manifestation of liberalism. Three others – cosmopolitanism, communitarianism and statism – are thin ideologies in the sense that they can be attached to thick ideologies in various ways.

Theory

Globalization scholars identify how the physical process of globalization is propagated by a powerful neoliberal ideology (e.g. Mittelman, Reference Mittelman2004). Neoliberals rhetorically connect free trade with the concepts of freedom, prosperity and peace: ‘[Neoliberal globalisation] remains perhaps the most effective tool we have to make the world not just more prosperous, but also a freer and more peaceful place’ (Paulson quoted in Mittelman, Reference Mittelman2004: 48). Other studies also document the discursive components of opposition to globalization. Rupert (Reference Rupert2000: 15), for example, identifies three different ideologies in the globalization debate. ‘… the dominant liberal narrative of globalization is being contested … from at least two distinct positions. One of these might be described as the cosmopolitan and democratically-oriented left … The other I will refer to as the nationalistic far right’. Rather than a bipolar pro vs. anti-globalization conflict, we may thus face a more multifaceted ideological spectrum.

To find out what this spectrum looks like, Michael Freeden (Reference Freeden1996, Reference Freeden2006) proposes the analytical morphological approach. It is ‘analytical’ in the sense that it positions itself in the positivist tradition. Rather than criticizing ideology as a tool of domination, the aim is to empirically map the nature of ideologies. Freeden sets out his morphological approach to study systematically the linguistic connection between various concepts. The analytical morphological approach thus leads to the systematic study of how the political concepts mentioned by Heywood and others – equality, freedom, fairness, etc. – are linked to arguments in favor and against various dimensions and manifestations of globalization. The more individual concepts become systematically linked to a particular political program, the more decontested they are. This raises several questions. Which concepts should we study? What are the relevant linguistic components of debates on globalization that might form the building blocks of different distinct ideologies?

According to Steger (Reference Steger2007), globalist ideology consists of six core truth claims: (1) globalization is about the liberalization and global integration of markets; (2) globalization is inevitable and irreversible; (3) nobody is in charge of globalization; (4) globalization benefits everyone; (5) globalization furthers the spread of democracy in the world; and (6) globalization requires a global War on Terror. We see here a clear linkage of a policy agenda of open borders connected to the decontestation of choice (there is no choice) and an articulation of who is or ought to be the key authority steering globalization (no one). Furthermore, as Steger continues: ‘The … idea of “benefits for everyone” is usually unpacked in material terms such as “economic growth” and “prosperity”’ (Reference Steger2007: 373). Steger’s inductive approach has yielded some key expectations regarding decontested concepts and their constellation. This includes policy positions, justifications, and collective identity. But without knowing the full population of concepts out there, we might miss important patterns in the contestation and de-contestation of concepts. Making a step in the direction of identifying this full population, Azmanova (Reference Azmanova2011) hints at how arguments from niche debates within political and legal theory start to become discernable in the wider public sphere debate on globalization. Implicitly, she draws here on the classic wisdom of Keynes: ‘Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back’ (Reference Keynes1951: 383).

The possible spaces of globalization ideology can be conceptualized based on philosophical arguments of universalism vs. contextualism on the one hand and globalism vs. statism on the other hand (Zürn and De Wilde Reference Zürn and De Wilde2016). Debates about how to realize justice in an interdependent world have played a major role in political philosophy for ages, allowing us to identify the range of arguments that might possibly be employed by those contributing to political debate about globalization in the public sphere. Following this, I distinguish here between four ‘bones of contention’. First, actors contributing to the globalization debate articulate policy demands concerning the openness or permeability of borders. This includes questions like: Should migrants be allowed to enter our country? Should we facilitate free trade? Second, actors address the desirability of political authority beyond the state. Questions on this dimension include: Should the World Trade Organization be allowed to rule on what is fair trade? Should the EU be empowered to fix the asylum quota for its member states? Third, actors engage in the articulation of collective identity. That may be in a representative form, as in ‘we demand social justice and equality for all people in the world’ (cf. Steger, Reference Steger2007: 378) or it may be in the form of a more cognitive assertion of the geographical scope of problems resulting from globalization. During the Brexit campaign, the United Kingdom Independence Party (in)famously asserted that the United Kingdom could not handle any more immigrants and was at a ‘breaking point’ (Stewart and Mason, Reference Stewart and Mason2016). This clearly presents the problem of refugees as a national one, not a global one. Fourth, and finally, actors link their policy demands, assertions on authority beyond the state and collective identity to justifications like equality, justice, economic prosperity, and inevitability. These justifications are ultimately rooted in moral foundations at the heart of philosophical debates. Notably, these are whether we can realize global justice based on the rights of the individual (Rawls, Reference Rawls1971), our embeddedness within broader groups (Walzer, Reference Walzer1983; Sandel, Reference Sandel1998), or a distinct reflection on what other groups need and are entitled to (Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka1995). Synthesizing these inductive and deductive approaches allows the formulation of descriptive hypotheses on the existence of ideologies in public debates on globalization and their respective values on four bones of contention.

Steger’s six core truth claims of a globalist ideology clearly resonate with the four bones of contention derived from political theory. The first truth claim on liberalization of markets contains an advocacy for open borders. The third truth claim that nobody is in charge (and that this is a good thing) implies a denunciation of political authority beyond the state. The second claim that globalization benefits everyone presents a universal collective identity as frame of reference. Finally, the second, fourth, fifth, and sixth claims justify globalization as inevitable, bringing economic prosperity, being good for democracy, and conducive to security.

Globalism Hypothesis: Public discourse on globalization features an ideology in which advocacy for open borders is systematically linked with a denunciation of political authority beyond the state, a universal human identity and the justifications of inevitability, economic prosperity, liberty, democracy, and security.

Agreeing with Rupert (Reference Rupert2000), Steger identifies two challenger ideologies to this dominant globalist ideology. First, particularist protectionism articulates an agenda against open borders. Steger sees this as strongly associated with far right populism in Europe and the United States.

Particularist protectionists include groups on the political Right who blame globalization for most of the economic, political and cultural ills afflicting their home countries or regions. Threatened by the slow erosion of old social patterns, particularist protectionists denounce free trade, the power of global investors, the neoliberal agenda of multinational corporations and the ‘Americanization of the world’ as practices that have contributed to falling living standards and/or moral decline. Fearing the loss of national self-determination and the destruction of their cultures, they pledge to protect their traditional ways of life from those ‘foreign elements’ they consider responsible for unleashing the forces of globalization (Steger, Reference Steger2007: 377).

Sometimes, the particularists might focus on free trade such as Ross Perot’s ‘giant sucking sound’ or Marine Le Pen’s statement that globalization means ‘manufacturing by slaves for selling to the unemployed’ (BBC, 2017). At other times, the focus is on the loss of cultural distinctiveness as a result of immigration or the loss of political sovereignty because of European integration. Key for this ideology, according to Steger, is the combination of a policy demand against open borders with a focus on a core group. A second descriptive hypothesis thus concerns the existence of a particularist protectionist ideology.

Particularist Protectionist Hypothesis: Public discourse on globalization features an ideology in which advocacy against open borders is systematically linked to the denunciation of authority beyond the state with the justifications of culture, tradition, prosperity and collective self-determination of and for a defined core group.

The key ideological component of collective identity is what differentiates the particularist protectionists from the universalist protectionists, according to Steger. Universalist protectionists also campaign against open borders, but demand a global authority charged with global redistribution because they are concerned about the inequality between the global North and South. ‘Universalist protectionists claim to be guided by the ideals of equality and social justice for all people in the world, not just the citizens of their own countries’ (Steger, Reference Steger2007: 378). The difference lies both in the cognition of problems (are we facing problems at national or at global level?) and the articulation of collective identity. Whereas particularist protectionists identify a regional group or nation as the focus of attention, the universalist protectionists focus on inequality and justice on a global scale. Hence, the existence of ‘globality’ as quoted from Steger in the introduction is paramount to globalization ideology. Following from the recognition of global concerns, universalist protectionists might be against free trade and open borders, but they are not necessarily opposed to political authority beyond the state (Steger and Wilson, Reference Steger and Wilson2012). Some regulation and enforcement may be needed to protect vulnerable groups such as indigenous societies and refugees and to orchestrate redistribution from the global North to the global South. The third descriptive hypothesis thus concerns the existence of a universalist protectionist ideology in globalization discourse.

Universalist Protectionism Hypothesis: Public discourse on globalization features an ideology in which advocacy against open borders is systematically linked to advocacy for political authority beyond the state and the justifications of equality and social justice, propagating a focus on human individuals across the globe or the collective universal identity of humanity.

The synergy of Steger’s inductive focus on the constellation of truth claims with our deductive theory on four bones of contention (Zürn and De Wilde Reference Zürn and De Wilde2016) yields the expectation that three ideologies of globalization can be identified in discourse and what their particular constellation of decontested concepts is. The three hypotheses reflect this. Their particular constellation of decontested concepts is summarized in Table 1. Note that these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. It could be that we find none of these ideologies as predicted in the analysis of globalization debate, or one, two, or all three.

Table 1 Theorizing ideologies of globalization

Finally, we need to free the analysis of ideologies from actors and look at arguments instead. The best empirical analyses on globalization ideology so far in existence, start from the assumption that key actors in the debate – such as the World Bank (Rupert, Reference Rupert2000: 50) or the Global Justice Movement (Steger and Wilson, Reference Steger and Wilson2012) – express a distinct and coherent ideology. This entails the danger of ecological fallacy. By assuming that a single actor has one single ideology, that this is complete and that globalization ideology can therefore best be studied by first identifying key players in the debate and then mapping their ideology, one risks underestimating the amount of ideologies, and overestimating their consistency. As Freeden originally argues, ‘ideologies are groupings of decontested political concepts’ (Reference Freeden1996: 82). They exist at discursive level, rather than actor level. Key actors in public debate may express the complete grouping of decontested concepts of a single ideology. More likely, however, is that they express parts of several groupings of decontested concepts. To best find out the nature of ideologies and differences between them, we need to empirically study decontestation at the level of arguments, rather than at the level of actors. This approach carries an additional value in that it allows a more finegrained analysis of the ‘thickness’ of ideologies. So far, ideology theory conceives of ideologies as either thick or thin (see Freeden, Reference Freeden1998: 75). The elaborate inductive quantitative approach employed here, however, sees thickness as a matter of degree. Ideologies can be more or less thick depending on the amount of successfully decontested concepts in its group and their extent of successful decontestation.

This study thus builds on the emerging literature on globalization ideology. Its primary aim is empirical: to map existing ideologies. In doing so, it pushes the frontier of Freeden’s analytical morphological research agenda on ideologies on three fronts. First, it deductively identifies major bones of contention, heeding Keynes’ classic wisdom that political debates in the public sphere are more often than not a transformed reflection of niche debates among academics. Thus, I study arguments about the permeability of borders, allocation of authority, collective identity, and justifications as they have long played a role in philosophical debates between universalist and contextualist theorists and between globalist and statist theorists. Second, I consider arguments as the basic building blocks of ideologies, without a priori fixing them to actors. Given that extant research on globalization ideologies has hardly done this to date, we take an inductive approach to analyzing the extent to which political concepts are decontested and in which way they combine to form identifiable, distinct groupings. Third, it opens up the dichotomy between thick and thin ideologies and reveals four distinct ideologies that have varying degrees of ‘thickness’.

Research design, method, and data

In the literature on ideologies, it is often implicitly assumed that ideologies are not restricted to a single country or issue (Heywood, Reference Heywood2017). All the main ideologies – for example, liberalism, socialism, fascism, etc. – have become manifest in multiple countries and featured in a variety of policy debates. Studying a single policy debate in one particular context thus hardly suffices to establish the existence of ideologies. I therefore analyze arguments in the public sphere in a wide range of contexts. This presents a hard test for finding ideological groupings, because it is unlikely that particular concepts are successfully decontested across very different contexts in similar ways.

To capture the wide variety of manifestations of globalization, the paper analyzes debates on five different political issues that each involve border-crossing: climate change, human rights, migration, regional integration, and trade. These reflect the border crossings of pollutants and their remedies, norms and values, people, political authority, and goods and services, respectively. There are many more issues that manifest and contribute to globalization which could have been included in this study. The selection here is merely an attempt to capture a broad variety of different issues related to globalization. They all involve some form of border-crossing directly related to human interaction and the potential political steering thereof. Thus, these issues allow for arguments in favor and against facilitating the interaction that generates such border crossings. The data includes public debates in five different countries – Germany, Poland, Turkey, the United States, and Mexico. They are all large, advanced industrialized democracies subject to the forces of globalization, but they differ strongly in their cultural and political heritage that may affect the ideologies present. In addition, plenary debates in the EP and UNGA on the same five issues are included. These are two ‘strong publics’ (Fraser, Reference Fraser1992) directly connected to the most powerful international organizations orchestrating globalization.

Claims in public spheres

To conduct an analytical morphological study of globalization ideologies, arguments on the permeability of borders need to be measured in association with allocation of authority, expressions of collective identity, and justifications. Moreover, the aim is to do this in a way befitting the positivist mapping agenda laid out by Freeden. Thus, we need a method to systematically measure the connection between such concepts at argument level in a reliable and valid way. I therefore build on the method of claims analysis (Koopmans and Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham1999) as a specific form of quantitative content analysis. Claims analysis is very suitable for an analytical approach to ideologies as it takes a very small unit – a ‘claim’ – as unit of analysis and measures relevant variables at that level. This allows analyzing linkages between policy preferences, discursive allocation of authority, collective identity articulation, and justification at the level of individual arguments made in public. Taking claims as a unit of measurement comes with the major advantage of maximizing ‘construct equivalence’ (Hantrais, Reference Hantrais1999: 104; Wirth and Kolb, Reference Wirth and Kolb2004) since political claims are basic building blocks of political debates, recognizable across time, space and forum. A claim is defined as a unit of action in the public sphere: ‘[…] which articulate [s] political demands, decisions, implementations, calls to action, proposals, criticisms, or physical attacks, which, actually or potentially, affect the interests or integrity of the claimants and/or other collective actors in a policy field’ (Statham, Reference Statham2005: 12). The archetypical claim would be a verbal speech act concerning some political issue that could be loosely translated as: ‘I (do not) want …’. However, the definition above is far more inclusive, encompassing meetings of the G8, protests by farmers, resolutions tabled by parliamentarians, and critical op-ed pieces by journalists. In textual terms, a claim can be as short as a few words, or as elaborate as several paragraphs, as long as it is made by the same claimant(s), conducting a single action in which a single position regarding open borders on a single globalization-related issue is articulated. The data were derived from at least three newspapers of different political profile in each of the five countries using key word sampling in LexisNexis as well as plenary debates in the UNGA and EP sampled from their respective online archives. The newspapers included are: Süddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, taz, Die Welt (Germany), La Jornada, Reforma, El Universal (Mexico), Gazeta Wyborcza, Rzeczpospolita, Nasz Dziennik (Poland), Milliyet, Hürriyet, Zaman (Turkey), New York Times, Houston Chronicle, and Washington Times (United States).

Coding was structured by a detailed codebook and involved 26 variables: (a) Year, (b) Source, (c) Claimant Type, (d) Claimant Scope, (e) Claimant Function, (f) Claimant Nationality, (g) Claimant Party, (h) Action, (i) Addressee Type, (j) Addressee Scope, (k) Addressee Function, (l) Addressee Nationality, (m) Addressee Party, (n) Addressee Evaluation, (o) Issue, (p) Problem Scope, (q) Position, (r) Intervention, (s) Object Function, (t) Object Scope, (u) Object evaluation, (v) Justification, (w) Conflict Frame, (x) Claimant Name, (y) Addressee Name, and (z) Origin. In short, it measures WHERE, WHEN, WHO, HOW, directed at WHOM, claims WHAT, for/against WHOSE interests, and WHY. In total, the data set contains 11,810 claims made between 2004 and 2011. Intercoder reliability of unitizing and all relevant variables was above the standard 0.70 agreement threshold (Lombard et al., Reference Lombard, Snyder-Duch and Bracken2002: 593). For further details on sampling, coding instructions, detailed inter-coder reliability results and descriptive statistics, please see the online codebook (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Koopmans and Zürn2014). In many ways, this representative claims analysis profits from previous claims analysis projects, such as EUROPUB.COM (Koopmans, Reference Koopmans2002) or SOM (Berkhout and Sudulich, Reference Berkhout and Sudulich2011). Drawing lessons of operationalization from these projects allows it to measure key concepts in a reliable and valid way. It differs, though, in three respects given the specific interest in mapping ideologies on globalization with an analytical morphological approach. First, it includes a wider set of countries and globalization-related issues, whereas previous projects have mostly focused on immigration and European integration as contested issues within Western Europe. Second, it conceives of political claims as potential representative claims (Saward, Reference Saward2010) in which actors try to mobilize a certain constituency. This implies a change from considering the ‘object’ of a claim from anyone affected to anyone whose interests or values are positively defended (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2013). Not only does this theoretically match the interest of studying ideology better, it also proved easier to code, yielding higher inter-coder reliability than was achieved on this variable in previous projects. Finally, given the prominence of justifications and moral foundations as central decontested concepts, this project invested more effort into adequately and elaborately measuring these as compared to previous claims analysis projects.

In the claims data set, the four conceptualized components of globalization ideology are operationalized as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2 Operationalization of ideology components

The variable position captures policy preferences regarding open borders where +1 indicates a claim in favor of open borders and −1 a claim against. The intermediate value 0 was allocated to claims of ambivalent, neutral, or unclear positions. To operationalize arguments in favor and against political authority beyond the state, this paper uses the addressee scope variable. An addressee is an individual or collective actor specified by the maker of the claim who is called upon to realize the articulated policy demand, or criticized for not doing so. Most often, addressees are powerful individuals or institutions with a capacity to influence policy that the actor making the claim lacks. For example, in a claim in which activists call upon the G20 to do more to combat poverty in the world, the G20 would be the addressee. Addressee scope is then the geographical location or mandate of the addressee. The G20, international organizations or such vague addressees as ‘the international community’ are coded as authority beyond the state (+1), whereas national addressees such as the government of a country are coded as −1. Similar scope variables operationalize collective identity and cognition. Problem scope indicates the cognitive geographical range. That is, it provides an answer to the question of whether a particular issue or policy problem affects the local, national, regional, or global level. National problems are coded as −1 whereas arguments identifying an international or global nature of globalization issues are coded as +1. Collective identity is operationalized through object scope, which measures any mentioned collective identity, group or individual by the maker of the claim as his or her constituency or whose case he or she is championing. Again, the maker might claim to represent an international (+1) or national (−1) group (Table 3).Footnote 1, Footnote 2

Table 3 Descriptive statistics on four variables operationalizing ideology components

The descriptive statistics already indicate a degree of dominance of globalist ideology. Three out of four means are positive, meaning we document more claims advocating open borders than closed borders and more claims recognizing problems related to globalization to stretch beyond the state than claims presenting issues as national in scope. In contrast, addressees are predominantly national. Overall, the discourse on globalization advocates open borders but demands action on this from national authorities. Beyond these interval variables that document a global/international vs. a national orientation, two multinomial variables capture justifications and moral foundations. First, in line with previous related content analysis projects (e.g. Helbling et al., Reference Helbling, Hoeglinger and Wueest2010) moral, ethical, and instrumental justifications are distinguished. Inductively, the list of justifications expanded during the coding within the confines of this conceptual framework. Whenever an actor justified his or her claim with a reference to moral values, we coded whether an individualist or collectivist understanding of justice was articulated and whether the claimant talked in terms of rights or needs. To illustrate the complexity, think of the different understandings of such a broad concept as ‘freedom’. We operationally defined it as ‘arguments articulating a preference to remove obstacles in economic, political or other forms to human self-fulfillment’. Freedom might be understood as a collective right – the freedom of a community to shape its own destiny. As, for example, stated by Mary Lou McDonald, member of the European parliament (MEP) for the far left European united left/Nordic green left group in the EP debate on the Lisbon Treaty in 2008: ‘Would the people of Europe support [the Lisbon] Treaty? I believe they would not, and perhaps that is why they are not being asked. … I want my country to have the freedom to take decisions in the best interests of our people’.Footnote 3 Here, the justification is coded as ‘freedom’ and the moral foundation is ‘own collective needs’. But freedom may also be understood in individual terms, such as freedom from oppression or freedom of speech. For example, in February 2011, the New York Times reported on violence by Colonel Qaddafi’s forces against Libyan citizens: ‘… crowds … had taken to the streets to mount their first major challenge to the government’s crackdown. ‘They shoot people from the ambulances,’ said one terrified resident, Omar, … ‘We have no freedom here,’ he said. ‘We want our freedom, too’.Footnote 4 Here we also coded ‘freedom’ as justification, but with ‘individual rights’ as the moral foundation. These are just two examples of how we coded complex justifications and their various moral foundations. A full overview of the justifications used along with coding instructions can be found in the online codebook. Descriptive statistics are in the Online Appendix.

Findings

The first question to answer is whether there are indeed three distinct ideologies, as hypothesized above. After establishing the number of ideologies, we can subsequently analyze the nature of each of them. The number of ideologies, I argue, is a function of the dimensionality of the ideological space combined with patterns of decontestation. The review of the literature has yielded four bones of contention, three of which are ‘dimensional’: permeability of borders, allocation of authority, and collective identity. With dimensional, I mean they conceptually contain various positions on a single line. For example, a single argument could be in favor of fully open borders, somewhat free border crossings, or completely closed borders. In operational terms, they can be considered scaled or dichotomous variables. In contrast, the fourth bone of contention – justification – is a multinomial variable in operational terms. If the three dimensions of permeability of borders, allocation of authority, and collective identity turn out to be empirically unrelated, then we face a three dimensional ideological space. It means that an argument for open borders may or may not go together with an argument supporting international authority and/or the representation of a global or international constituency. A bivariate correlation analysis of the four interval variables position, addressee scope, problem scope, and object scope, however, reveals positive and significant correlation.Footnote 5 This indicates that we may not face a three-dimensional space. On closer inspection, the positive correlation between the position variable on the one hand and the other three variables on the other is very weak. The high number of claims in the analysis accounts for the significance of the results. In comparison, the correlation between the other three variables is much stronger. As a robustness check, I conducted the same bivariate correlational analysis for each of the different contexts – Germany, Mexico, Poland, Turkey, the United States, the EP, and the UNGA – separately. A similar check was done for each of the issues – climate change, human rights, migration, regional integration, and trade. The positive correlation between position and the other three variables does not hold in these robustness checks, while the significant and positive correlation between the other three variables is robust.

There is thus strong empirical evidence that allocation of authority, cognition, and collective identity together form a single dimension in globalization ideology as measured in public discourse. So much so, that they are scalable (Cronbach’s α is 0.734). I thus constructed an additive new variable globality which is the sum of addressee scope, problem scope, and object scope (descriptive statistics in Table 3). A principal component analysis confirms the two-dimensional nature of globalization ideology. The second dimension barely misses the standard threshold of 1.0 Eigenvalue, but explains a significant additional amount of variance, combining with the first dimension to go over the standard minimum of 60% explained variance for factor analysis (Table 4).

Table 4 Principal component analysis

Extraction method: principal component analysis.

Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Eigenvalues above 0.9 reported.

a Rotation converged in three iterations.

We have now established that four out of six discourse components of globalization ideology form a two-dimensional space, with the position (permeability of borders) as one dimension and the allocation of authority, cognition, and collective identity (globality) combined making up a second dimension. This means that the amount of ideologies can vary between zero and four. It would be zero if all justifications are located in the center of this space, thus remaining contested. To further understand, consider the hypothetical example that an appeal to ‘equality’ is as often used to justify open borders as it is to justify closed borders. The mean location of this justification on the permeability of borders dimension would then be in the middle of the y-axis. Now consider the same applies for the globality dimension, we would find ‘equality’ right in the middle of the two-dimensional ideological space. This means it is a deeply contested concept. What it means to pursue equality in a globalizing world could be anything. In this hypothetical case, the discursive struggle is raging and ‘equality’ is not part of a globalization ideology, because it has not been successfully decontested. Now consider another hypothetical example, where – as theorized in the literature – neoliberal ideology consists of arguments for open borders with no one in charge as the best way to realize economic prosperity. We would then find ‘economic prosperity’ as justification in the open borders and low globality corner of the ideological space, because justifications of furthering economic prosperity are strongly associated with claims to open up borders for the sake of national or other demarcated groups and their problems. What it means to pursue economic prosperity would in this case be successfully decontested: it would mean open borders and low globality.

In short, the more justifications diverge from the center toward either of the four corners of the two-dimensional space, the more decontested they are and the more they contribute to the establishment of globalization ideologies. If all justifications are located in the center of the space, it means they are all contested and no clear globalization ideology can be discerned. If, on the other extreme, all justifications are located at corner positions, they have all become successfully decontested, and globalization debate is shown to be highly ideological. The amount of ideologies is operationalized as the number of the four quadrants of the two-dimensional ideological space that are populated by justifications whose position clearly diverges from the contested center of overall discourse. If all four discursive quadrants are populated by different groupings of concepts, this will be considered evidence for the existence of four distinct ideologies. Finally, the more concepts are successfully decontested in any of the four quadrants, the ‘thicker’ this particular ideology is as it implies a more complete and established political program.

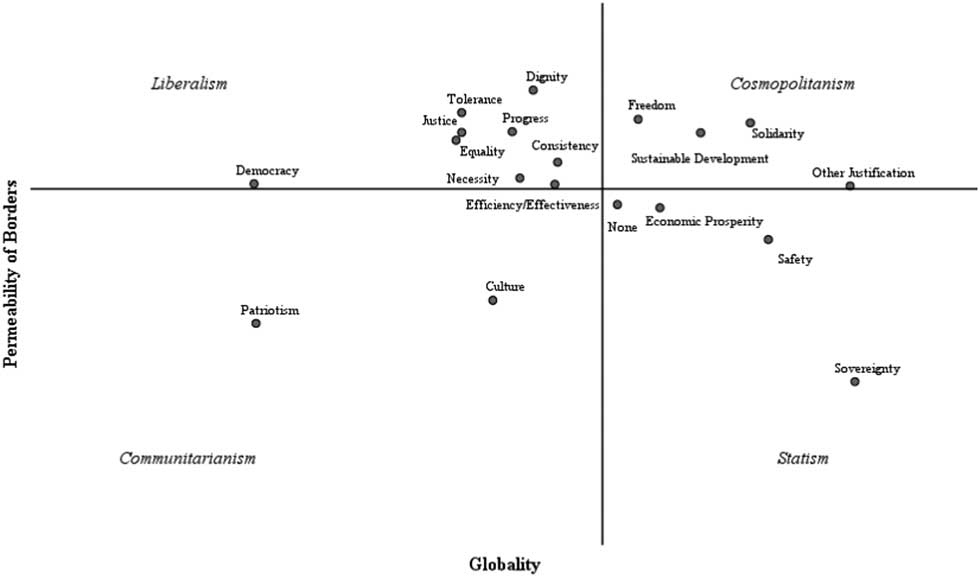

Below is the two-dimensional space of permeability of borders (y-axis) and globality (x-axis) with lines indicating their mean positions (at x=0.23 and y=0.46). It can thus show how a group of claims that contains a certain justification relates to the mean positions on both dimensions. Here, all claims across issues and countries are weighted equally. This reflects the morphological assumption that ideologies are located at argument level and the implicit assumption in the literature that ideologies should be discernable across various different specific policy debates and that they are not restricted to a single country (Figure 1).Footnote 6

Figure 1 Mapping Justifications in the two-dimensional ideological space.

The bottom left quadrant features claims that are relatively skeptical of open borders, do not recognize the globality of problems and/or argue against political authority beyond the state. These claims often refer to patriotism and cultural concerns and values. However, they are not necessarily associated with the nationalist far right, as indicated by Rupert and Steger. The left, especially far left, equally make such arguments, as the quoted claim from MacDonald, MEP, above illustrates. It is furthermore echoed by non-partisan actors, such as clergy: ‘In a letter to Poles living outside the country, the [group of Polish] bishops call upon them “not to lose the spirit of healthy patriotism and not to break the bond with the nation”’.Footnote 7 While this ideology largely reflects the predictions of particularist protectionism formulated in Hypothesis 2, the label of communitarism fits better since a wide range of actors beyond far right nationalists make such claims.

The top left quadrant features claims in favor of open borders but relatively nationally oriented in terms of the authority, cognition, and collective identity. This reflects the discursive constellation of globalism, as reflected in Hypothesis 1. It also features some of the key justifications of globalism, namely justifications related to democracy, progress and necessity. However, some other key justifications are not located here. Arguments regarding safety and economic prosperity are in the opposite bottom right quadrant. It thus appears that the truth claim that globalization requires a global war on terror is not – or no longer – a part of this ideology. Nor does it appear that this pro-globalization ideology has successfully decontested economic prosperity as a core justification associated with its political program. What the nature of problems is, who should be in charge, and which policies should be pursued in the name of furthering economic prosperity are deeply contested questions in public debates about globalization. Moreover, the top left quadrant features some moral and ethical considerations for which Steger and other critics of neoliberal globalization do not give it credit. Arguments in favor of open borders in an international – as opposed to global – worldview are often justified with concerns for equality, justice, tolerance, and human dignity. This quadrant includes arguments in favor of free trade without global regulation, but also champions applying global human rights standards in a local setting and welcoming refugees in a particular country. The claim by Omar, the Libyan protester against Qaddafi that was quoted above, fits into this quadrant. It demands the application of global norms on human rights while having a clear local Libyan focus. Thus, this ideology is rather the classic ideology of liberalism that is concerned with individual happiness and self-determination in cultural, political, and economic terms, instead of the narrower neoliberal market ideology or neoconservative democratic imperialism that critical theorists often depict it to be. Tolerance is the most important concept associated with this ideology, as corroborated in the robustness checks in the Online Appendix.

The top right quadrant reflects some key features of the universal protectionism as formulated in Hypothesis 3. Claims in this quadrant articulate demands for powerful international institutions to regulate globalization, and justifications of solidarity and sustainable development. There is, however, a crucial feature that goes against expectations formulated in Hypothesis 3, namely that these arguments are explicitly championing open borders. These might be economic free trade arguments, but more likely advocacy for global respect for human rights, welcoming refugees and global action against climate change. Labeling this quadrant universalist protectionism therefore appears a misnomer. Instead, the evidence in this paper documents the existence of a pure form of cosmopolitanism as ideology in the public sphere, that champions open borders, international authority and stresses the global nature of problems in pursuit of solidarity and sustainable development. These are not anti- or alter-globalist arguments, they are ultra-globalist, if anything.

Finally, the bottom right quadrant presents us with a puzzle, initially. It seems paradoxical that arguments invoking sovereignty as a key justification would advocate authority beyond the state. This ideological grouping should be considered a hybrid form. The arguments here recognize the global nature of today’s problems and international interdependence but advocate closure of borders and preservation of sovereignty to protect societies. Globalization is either a threat or given in this narrative. Consider, for example, the following claim: ‘While migration contributes to the increase in the rates of intellectual and economic growth of many countries, it can also at times be a serious challenge to other countries. It is therefore imperative that we agree on realistic mechanisms that recognize the right of sovereign States to protect their borders …’.Footnote 8 It reflects statism as a strand in political theory that combines a recognition of global issues and problems with the advocacy of closure and maintenance of the nation state as the key institution of global politics (Nagel, Reference Nagel2005). An emphasis on intergovernmental solutions to international problems, rather than powerful supranational institutions, contributes to the establishment of this statist ideology in public discourse. Of the four ideologies documented here, this is clearly the thinnest. Aside from a recognition of interdependence – particularly in the form of global threats – and an advocacy of sovereignty, there is not much substance to this ideology.

While these four ideologies appear clear and intuitive, no conclusive answer is yet given to the question how distinctive they are. In other words: to what extent are the justifications associated with each of the four ideologies successfully decontested? Many justifications appear close to the center in the graph, indicating that arguments in all four of the quadrants employ them. They are thus contested. While no justification is completely decontested, a Kruskal–Wallis H test reveals that there are significant differences on both dimensions between groups of claims that employ different justifications.Footnote 9

Figure 2 Mapping moral foundations in the two-dimensional ideological space.

Following this result, I ran Games–Howell Posthoc tests of pairwise mean differences to see if any of the individual justifications is significantly associated with one of the four ideologies.Footnote 10 Patriotism is significantly associated with mean positions that are in the bottom-left communitarian ideological quadrant. Equality, justice, and necessity are significantly associated with the top left liberal ideology. Sovereignty and safety are significantly associated with the bottom right statist ideology. All other justifications are either not significantly decontested or only so on one of the two ideology dimensions. Finally, I ran the same tests on the specification of moral justifications in terms of understandings of justice.Footnote 11 Here too, the null hypothesis that there is no difference in philosophical underpinning of moral argumentation across the four ideologies needs to be rejected. In other words, the evidence presented here supports the notion that different ideologies of globalization have become discernable in the public sphere as various justifications and expressions of moral foundations have become significantly decontested.

Given low numbers of claims that contain explicit articulation of what kind of foundation underpins moral argumentation, few of these foundations are significantly associated with one of the four ideologies. Only a concern for the rights of individuals stands out as core to the liberal top left quadrant and lends it further ‘thickness’ as ideology. It should further be noted that no ideology can claim a monopoly over morality. Three of the four ideologies contain explicit moral argumentation, even though they have different understandings of justice in such argumentation. While the liberal ideology bases its argumentation and judgment of globalization on the foundation of individual human rights and needs, cosmopolitans adhere to multicultural principles of taking into account the rights of other groups (cf. Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka2010). Finally, communitarian arguments are based in the foundational concern for the needs of one’s own group.

To sum up, this rigorous quantitative content analysis of globalization discourse reveals a two dimensional ideological space of globalization. One of the quadrants of this space, where arguments for open borders with a local focus are located, features a rich set of justifications and moral foundations. These arguments are justified with moral concerns for equality and justice with an understanding of justice based on individual human rights and needs. It furthermore contains ethical and instrumental justification, showing concern for tolerance, progress, necessity, and democracy. These are all related to classic liberalism, centered around individual freedom. It features the thickest ideology. The other three quadrants also feature decontested concepts, but not to a similar extent as the liberal ideology. A communitarian ideology features arguments against open borders and global governance. They are justified by concerns for patriotism and culture, based morally on the needs of the own collective. This line of argumentation could come, however, in both socialist and nationalist variants. Protection of the welfare state and protection of an ethnic group both employ communitarian argumentation. Hence, it remains a fairly thin ideology. Naming it nationalism is misleading, as its core group can also be international, such as ‘Europeans’, ‘the West’, or the global Umma. The term communitarianism is here preferred over particularlist protectionism to acknowledge its concern for morality and its usage by actors of various political profiles. Third, the analysis reveals a cosmopolitan ideology. Here arguments feature in favor of both open borders and global governance, justified by concerns for solidarity and sustainable development and the rights of other disenfranchised groups. In refutation of the universalist protectionism hypothesis, this ideology strongly advocates open borders, hence the labeling of cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism, as documented here, remains a thin ideology just like communitarianism. Finally, a statist quadrant forms the thinnest of ideological quadrants. Arguments contributing to the establishment of this ideology in public discourse articulate the recognition of global problems and interdependency, considers this a threat or a given, and justifies its claims against open borders with concerns for sovereignty and safety.

Conclusion

Four distinct globalization ideologies become evident in this investigation of the existence of ideologies in the public discourse on globalization. First, a thick liberal ideology features arguments in favor of open borders and against regulating authority in the form of powerful international organizations or global governance more generally. It is driven by the concerns for geographically limited problems and in the pursuit of local or national interests. In contrast to neoliberalism, this ideology is not only concerned with free markets and lacks the safety or security concerns of the neoconservative War on Terror. Instead, this study documents the propagation of globalization by a thick liberal ideology which advocates individual rights in cultural, political, and economic terms to push for open borders, albeit with a local orientation. Second, the analysis reveals a communitarian ideology opposing globalization. These arguments articulate demands for closing borders and against global governance. They are justified with appeals to patriotism and concerns for preserving culture. Moreover, they are rooted in moral foundations connected to communitarian political philosophy where the own group and its needs stands as the ultimate unit of moral concern. It is decidedly thinner than liberalism. Third, this paper presents evidence of a cosmopolitan ideology. It consists of arguments in favor of open borders and global governance, justified by concerns for solidarity and sustainable development and the rights of other, disenfranchised, groups. It is thin, like the communitarian ideology. Finally, a very thin statist ideology articulates the recognition of global problems and interdependency, considers this a threat or given, and justifies its claims against open borders with concerns for sovereignty and safety (Table 5).

Table 5 Four ideologies of globalization

Justifications and specifications with significant deviation of group means from the average in both dimensions are underlined. Others are in italics.

Three key revisions to our understanding of ideologies in relation to globalization follow from these findings. First, advocates of globalization are not neoliberals or neoconservatives. A depiction of globalist ideology as merely championing free trade, deregulation, and aggressive democratization is not supported by the data in this study. Rather, a thick liberal ideology stands behind open borders that is equally concerned with cultural, political, and moral considerations of liberalism as with economic considerations. Second, the ideology of the anti- or alter-globalization movement needs to be rethought. Crucially, this analysis reveals strong advocacy of open borders in arguments typically associated with this group. If anything, this is an ultra-globalist ideology, since the evidence does not reveal protectionist tendencies. It is therefore best labeled cosmopolitanism. Third, this study shows how denouncing opposition to globalization as nationalist or protectionist does not do it justice. The arguments against globalization documented here reflect the moral foundations of communitarian political philosophy. They articulate the legitimacy of achieving justice for one’s own group and evoke concerns for patriotism and culture. Hence, no ideology of globalization can claim a monopoly on morality.

Only one of the four ideologies observed here deserves the label of thick ideology. All others are thinner and may come in variants linked to traditional ideologies like socialism, conservatism, or even fascism. Furthermore, the analysis reveals that many core concepts remain essentially contested. Robustness checks also reveal a degree of fluidity in the constellation of ideological concepts across issues and countries. The ideological landscape in globalization discourse is thus far from fully crystalized. We are witnessing a period in time in which globalization ideologies are still in the process of being made, rather than having been fully established. The ideological discursive landscape may well have further developed by now. The data presented here runs until 2011, meaning some formative events for globalization ideology like Brexit, Trump’s election, or TTIP are not yet included. Future research could investigate this historical dimension in the formation of globalization ideologies further.

Theoretically, this article presents three innovations. First, it takes the analytical morphological approach to ideologies to a new level by employing it in systematic quantitative content analysis. This is done through a deductive identification of possible dimensions of ideology from political philosophy, drawing on Keynes’ classic wisdom that ideologues in the public sphere often draw from the works of academics and that ideological components as occurring in the public sphere can thus be related to academic works. Following this identification of the possible landscape and dimensionality of ideologies, inductive analysis, taking Freeden’s emphasis on ideologies as groupings of concepts seriously, was conducted to identify the empirical dimensionality of globalization ideology. Finally, a varied, detailed, and rigorous analysis of concepts in this space allows us to open up a binary distinction between thick and thin ideologies. The approach developed here allows us to conceive of a continuum, from very thick to very thin ideologies. This is corroborated by showing the thickness of liberal ideology in globalization discourse, the thinner versions of cosmopolitanism and communitarianism, and the very thin statism.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000164

Acknowledgements

This article stems from the project ‘The Political Sociology of Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism’, conducted at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center, 2011–2016. The author would like to thank the fellow project members Ruud Koopmans, Onawa Lacewell, Wolfgang Merkel, Oliver Strijbis, Céline Teney, Bernhard Wessels, and Michael Zürn for highly stimulating collaboration.