Part I Ellington in context

1 Artful entertainment: Ellington’s formative years in context

Duke Ellington’s 1927 debut at Harlem’s Cotton Club has long been positioned as a landmark moment in his career. During his initial four-year tenure at the club, the bandleader’s orchestra rose to national and then international fame. Throughout this period, the growing critical and public interest in Ellington was fueled by both the ever-increasing brilliance of his compositions and his incomparable orchestra, as well as the innovative promotional strategies of his manager, Irving Mills. The building blocks for this unique career, though, were formed in the musical and cultural contexts of Ellington’s youth in Washington, D.C.; in his early years as a sideman and bandleader in both Washington and New York; and especially in his educational immersion in the world of Harlem entertainment.

Edward Kennedy (“Duke”) Ellington was born in April 1899 and raised in a loving, middle-class household in Washington’s thriving African-American community. In Ellington’s youth, Washington had the largest black population of any city in the country, and his racial pride and strong self-image were greatly shaped by the mores of this city’s significant black middle- and upper-class communities. His Washington years also laid the foundations of his growth and interests as a musician and composer.

Ellington’s family had a passion for music, and he loved to listen to his mother, Daisy, play hymns and light-classical / parlor pieces at the piano, including such favorites as C. S. Morrison’s 1896 “Meditation” and Ethelbert Nevin’s 1898 “The Rosary.” Ellington’s father, James Edward (known as “J. E.”), played both piano and guitar by ear, and favored opera arias and popular songs of the day.1 When young Edward was around seven or eight, Daisy arranged for him to take piano lessons with a Mrs. Marietta Clinkscales, but as Ellington later noted, “At this point, piano was not my recognized talent.”2He was also exposed to black church music traditions, with his father attending the local African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, and his mother attending a Baptist denomination. In both, Ellington heard a range of popular hymns and spirituals, such as “Abide With Me” and “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”3 This music was quite important to him and richly informed his later extended compositions, such as Black, Brown and Beige (1943) and his three Sacred Concerts (1965, 1968, and 1973), as well as numerous smaller works.

Ellington liked to joke that he had two educations – one in the pool hall, and one in school.4 In Frank Holliday’s poolroom, he was able to observe a cross-section of Washington’s diverse African-American community and to overhear both talented pianists and conversations between “the prime authorities on every subject.”5 By the time he was 13 or 14, Ellington had begun to seek out performances by many of the region’s talented ragtime pianists. Of particular importance was a family vacation in the summer of 1913 to Asbury Park, New Jersey, where he was impressed by a young pianist, Harvey Brooks, who taught Ellington a number of elementary ragtime techniques. After this, Ellington was greatly inspired to return to learning the piano. He later said, “I played by ear then,” but acknowledged that he “couldn’t begin to play the tunes” of the pianists he admired.6 At the same time, he worked at a soda fountain called the Poodle Dog Cafe. When the cafe needed a new pianist, Ellington offered his services, but quickly realized that “the only way I could learn how to play a tune was to compose it myself and work it up.”7 Ellington thus wrote his first composition, Soda Fountain Rag (a.k.a. Poodle Dog Rag), and this creative act was intimately entwined with both necessity and his performance aspirations. Other ragtime-influenced piano compositions followed, including What You Gonna Do When the Bed Breaks Down? (1913) and Bitches’ Ball (1914). As the Ellington scholar Mark Tucker has noted, early works like Soda Fountain Rag were not fully composed, “set” compositions but instead “consist[ed] of a few musical ideas that serve[d] as a basis for improvised elaboration.” The young pianist regularly adapted such materials in new combinations, tempos, rhythms, and styles. In this period Ellington acquired his nickname, “The Duke,” when a friend remarked on his elegant clothes and noble demeanor. After he was goaded into playing a number at a dance, Ellington also discovered that “When you were playing piano there was always a pretty girl standing at … the end of the piano.”8 Though he was training to become a commercial artist as he began high school in 1913–1914, Ellington had found the key inspirations for his ultimate career as a composer-musician.

The Washington experiences that left the greatest impact on his growth as a musician were the lessons he learned – both directly and through observation – from the city’s pianists. In addition, as Tucker has noted, Ellington found lifelong artistic and professional inspiration in the city’s black historical pageants, the elder professional musicians who encouraged his early bandleading endeavors, and the so-called “Washington pattern” of black composer-bandleaders.9 This “pattern” involved the pursuit of multifaceted careers (as bandleaders, performers, composers, and songwriters), a professional demeanor that commanded cross-racial respect, and the active promotion of black vernacular idioms through original compositions. Tucker points to the older musician-bandleaders Will Marion Cook, James Reese Europe, and Ford Dabney – all central figures in both New York and Washington entertainment across Ellington’s youth – as the three most likely career models for the aspiring pianist-composer. Following this “Washington pattern” across his career, Ellington pursued a diverse creative life that spanned work as a pianist and bandleader, work in musical theater and nightclub revues, and the composition of vernacular-based concert works.

Among the many musicians Ellington knew in his teens, the two most important were Oliver “Doc” Perry and Henry Grant. Both were generous, intelligent, “conservatory” musicians who took an interest in Ellington and impressed him with their deep respect for both formal (classically trained) and vernacular (“the cats who played by ear”) musicians. Perry, a ragtime pianist whom Ellington called his “piano parent,” taught the young pianist rudimentary ragtime and popular-music score-reading skills and chord theory.10 Grant taught music at Ellington’s high school and generously gave him private lessons in harmony, a gesture which the budding musician later felt “lighted the direction to more highly developed composition.”11 Ellington’s associations with such supportive, older musicians also led to performance opportunities that set him on track for a career in music rather than art.

These early piano jobs further awakened his skills as a businessman, and a notable lesson came during a job as a substitute pianist for a socialite party. Though Ellington provided the actual entertainment, the original pianist, to Ellington’s amazement, still collected 90 percent of this engagement’s $100 fee. As he recalled, “the very next day” he “arranged for a Music-for-All-Occasions ad in the telephone book,” and Ellington-the-entrepreneur was born.12 His entertainment agency provided both music – which led to the formation of his first band – and advertisement, with Ellington creating posters to advertise events.

In his autobiography, Ellington remarks that in his Washington youth “it was New York that filled our imagination. We were awed by the never-ending roll of great talents there … in society music and blues, in vaudeville and songwriting, in jazz and theatre, in dancing and comedy.” He adds that “Harlem … [had] the world’s most glamorous atmosphere. We had to go there.”13 Ellington further recounts a long list of Harlem’s entertainers as well as its famous nightclubs, ballrooms, and theaters. While he and his Washington friends were deeply entranced by the seductive folklore of black Harlem, across their teenage years in the 1910s, this world was only just coming into being.

In a 1925 essay, the famous African-American author James Weldon Johnson notes that, in the 1890s, “the center of [Manhattan’s] colored population had shifted to the upper Twenties and lower Thirties west of Sixth Avenue.” Johnson adds that the black population moved again in the next decade, this time up to an area around West 53rd Street.14It was during this latter era that New York’s African-American entertainment traditions first took shape in a variety of stage productions. The black pioneers in Broadway musical theater, the nascent recording industry, and the later dance band industry of the 1910s emerged around the West Indian-born comic Bert Williams and his vaudeville partner George Walker. In late 1897, the young composer-violinist (and former Washingtonian) Will Marion Cook approached Williams and Walker with the idea of mounting an all-black musical called Clorindy, or, The Origin of the Cakewalk. Cook’s hour-long show opened – without Williams and Walker, due to a prior engagement – in July 1898 at the Casino Theatre Roof Garden on Broadway at 39th Street. This production sparked an African-American entertainment renaissance that produced a decade-plus string of all-black musical theater hits. Another member of the Williams-Walker creative team was Will Vodery, who shared duties as musical director, composer, and arranger with Cook. The successes of Williams, Walker, Cook, and Vodery were not alone. In particular, James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson, in partnership with the performer Bob Cole and the conductor James Reese Europe, mounted serious competition.

Ellington was greatly impressed by the business acumen, cross-racial success, and race-oriented artistry of both Cook and Vodery. He gratefully acknowledged on numerous occasions that across the 1920s both men generously provided him with professional advice as well as “valuable” informal lessons in harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration. Even though the precise nature of these “lessons” is unknown, Cook and Vodery were undeniably important professional friends, role models, and mentors for the young composer across his early years in New York. Ellington’s emergence as a Washington bandleader in the mid-teens was also shaped by the broader cultural influence of these older musicians.

In 1910, black Broadway’s core members formed the Clef Club, the premier New York booking agency and trade union for black musicians. With James Reese Europe as its president, the Clef Club was at the forefront of providing music for a major dancing craze that ran from 1913 to 1919. Though black stage productions on Broadway waned during the mid-to-late teens, these syncopated orchestras maintained a prominent presence of black performers in white entertainment venues up through 1919. This white market demand for black bands spread to other cities with major African-American communities, including Washington, and provided many young musicians with opportunities both to perform in, and join, established ensembles, and to organize their own dance bands. Ellington was active in both areas, but even during this period of his growing success, he had his sights set on New York.

Ellington’s star-struck impression of black New York was centrally tied to Harlem’s rise as the epicenter of the black entertainment community. This uptown relocation came at the end of 1913, when Europe and other musicians broke from the Clef Club to found the Tempo Club, a second black booking agency. Whereas the Clef Club was based in Midtown, the Tempo Club was founded in Harlem. This shift was central to the birth of Harlem entertainment proper, and paralleled the influx of African Americans into this neighborhood. New York’s top all-black and mixed-race nightclubs similarly moved up to Harlem across the mid-to-late teens.

Ellington’s first personal encounter with the world of Harlem entertainment came in Washington in November 1921, after a friend dared him to play his rendition of the Harlem pianist James P. Johnson’s virtuosic composition Carolina Shout for Johnson himself. Johnson was impressed, and became a friend and supporter of the young pianist. Through similar Washington encounters, Ellington began to associate with other key New York musicians.

New York’s black entertainment renaissance of the 1920s took root on Broadway stages following the immense success of the 1921 all-black musical Shuffle Along, by the stage duo of Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, along with the pianist Eubie Blake and his singing partner, Noble Sissle. This production was the catalyst for a second wave of all-black musicals across the 1920s. While Shuffle Along’s success increased white interest in black entertainment in Harlem, fashionable white audiences had ventured up to Harlem’s black cabarets from the very beginnings of the community’s nightclub scene in the mid-1910s. It was in this earlier period that a celebrated virtuosic piano tradition took shape in and around Harlem’s new nightclubs. By the early 1920s, James P. Johnson was the chief exponent of this early jazz idiom, which was known as stride piano. Johnson’s 1918 and 1921 piano rolls of Carolina Shout laid the foundations of jazz piano for a generation of pianists – including Ellington – who learned the work note-for-note from these rolls.

Despite the rising profile of Harlem nightlife, several major setbacks for New York’s black entertainment community occurred in the late teens. First, the 1917 New York arrival of the (white) Original Dixieland Jazz Band (the “ODJB”) marked the beginning of a nationwide white interest in jazz-related music (as distinct from ragtime). Shortly thereafter, a group of arrangement-heavy, white dance bands rose to prominence and began to distance themselves from the rough-edged, New Orleans-style, improvised “hot” jazz of the many bands that followed the ODJB model. These “sweet” dance orchestras included the bands of Art Hickman and Paul Whiteman, among others. An important turning point in the racial makeup of New York’s music scene occurred in 1919 when the Hickman ensemble displaced the black orchestra of Ford Dabney (a Clef Club member) at theater impresario Florenz Ziegfeld’s Broadway roof garden restaurant. After this, there were still a number of smaller Midtown/Broadway nightclubs and dance halls that featured black jazz-oriented bands. By the early 1920s, Harlem nightclubs began to feature both small bands and the aforementioned piano performers. Within time, these bands were also backing ever more elaborate floorshow revues. By the mid-1920s, many of these nightclub revues aspired to be just as lavish as their Broadway stage counterparts, and this ambition led to larger orchestras and the rise of black big band jazz. This is the precise context of Ellington’s rise to fame.

Ellington first traveled to New York in February 1923. He and his friends, drummer Sonny Greer and saxophonist Otto Hardwick, had been hired as backing musicians for the clarinetist Wilbur Sweatman’s engagement at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre. During their short stint with Sweatman, Greer, Hardwick, and Ellington circulated among Harlem’s entertainment community, and most particularly James P. Johnson’s social circle. Ellington was soon introduced to several musicians who later joined his first New York bands, including trumpeter James “Bubber” Miley and trombonist Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton. After their money and gigs ran out, Greer, Hardwick, and Ellington headed back to Washington. By the summer of 1923, however, they returned with the band of banjoist Elmer Snowden. After several minor fiascos and a spot of good luck, Snowden’s band landed a prime spot at Barron’s Exclusive Club up in Harlem. While Ellington largely played for dancers at Barron’s, he had the opportunity to work as a rehearsal pianist for the Connie’s Inn revues (also in Harlem), an engagement that launched his education on the workings of Harlem’s burgeoning musical revue tradition. By late summer, he had also partnered with the lyricist Jo Trent in a new songwriting venture. In the fall of 1923, Snowden’s orchestra relocated to the Hollywood Club (on 49th Street near Broadway), a small Midtown venue popular among white musicians and Broadway celebrities. Ellington quickly assumed control of the band, and the venue’s name changed not long after to the Kentucky Club. The Washingtonians, as they were called, soon began to develop a more “hot” sound with the addition of such new band members as Miley and Nanton.

Ellington’s early, pre-Cotton Club compositional efforts from this period ideally reflect the entire breadth of mid-1920s black entertainment trends. Through his partnership with Trent, Ellington hoped to break into the lucrative songwriting business of black Tin Pan Alley. The composer was indeed quickly befriended by such influential black songwriters as Maceo Pinkard. Pinkard notably arranged for the Washingtonians’ first recording session, which included such early Ellington-penned instrumental compositions as Rainy Nights and the train-themed Choo Choo.15 While fairly routine fare for the day, these early recordings do exhibit small innovative details – and the distinctive instrumental voices of his band members – that were later transformed into hallmarks of Ellington’s work for the Cotton Club. With this future in mind, it should be noted that the Trent-Ellington partnership contributed several songs – such as “Jim Dandy,” “Jig Walk: Charleston,” and “Deacon Jazz” – to a new stage revue, Chocolate Kiddies. This production was meant to emulate the success of two earlier nightclub revues, the 1922 Plantation Revue and the 1922–1923 Plantation Days, both of which went on to Broadway stage runs and lucrative European tours (Chocolate Kiddies only accomplished the latter). Ellington was equally successful in the dance band realm, and during this initial foray to New York, his Washingtonians even entered the nascent medium of radio through local broadcasts from the Kentucky Club. The band additionally began to pursue vaudeville work. In sum, these various career developments illustrate Ellington’s growing abilities to navigate the increasingly fluid boundaries between dance bands, Tin Pan Alley song publishing, the record industry, radio, and New York nightclub and stage entertainments.

In mid-to-late 1926, Ellington began his professional association with Irving Mills, a well-connected white music publisher, impresario, and talent manager.16 Together they built the Ellington orchestra into one of the top dance orchestras of the day, black or white. Through his diligent and persistent promotion of the bandleader across the late 1920s and 1930s, Mills was able to advance Ellington’s career up a ladder of ever more prestigious accomplishments. The end goal of these efforts can be seen in Mills’s 1930s advertising manuals, which boldly demand that promoters “sell Ellington as a great artist, [and] a musical genius whose unique style and individual theories of harmony have created a new music.”17 This “musical genius” image had its roots in Ellington’s early years with Mills, over 1926 and 1927, when the bandleader was finding his unique voice as a composer. This individuality partially emerged in a number of mid-1926 recordings, but it is with the November 1926 recordings of such instrumental compositions as East St. Louis Toodle-O and Birmingham Breakdown – and especially the April 1927 Black and Tan Fantasy – that his characteristic early voice as an orchestral jazz composer fully blossomed. Notably, these arrangements were recorded more than half a year before these same numbers became cornerstones for the exotic sound of his Cotton Club “jungle music.”

In October 1927, the Ellington orchestra joined the Lafayette Theatre’s Jazzmania stage revue. It was this engagement that caught the attention of the songwriter Jimmy McHugh, who was busy developing a new floorshow revue at the Cotton Club in Harlem. At the encouragement of McHugh (who had ties to Mills), Ellington and his band were hired as the club’s new orchestra. As the story goes, the Cotton Club’s gangster associates freed Ellington from a conflicting contract by telling a theater owner to “be big or you’ll be dead.”18

With his employment at the Cotton Club, Ellington had moved to the epicenter of 1920s Harlem entertainment. The club’s regular radio broadcasts – which were primarily features for the band – soon spread the bandleader’s music and name across the country.19 For the club’s glamorous revues, he contributed band arrangements for songs by the club’s white composing staff as well as his own distinctive compositions as instrumental background music for select show numbers. The band additionally provided music for dancing. Ellington’s new Cotton Club fame led to national and international tours for the band, work in various Broadway and Hollywood musical productions, and many other high-profile opportunities.

Like Cook’s and Vodery’s work in the teens, Ellington’s Cotton Club-era compositions and arrangements drew unusual cross-race critical praise for his abilities as a “serious” composer working in popular entertainment. From the late 1920s forward, this critical literature routinely positioned the 1926 and 1927 recordings of East St. Louis Toodle-O and Black and Tan Fantasy as both watershed moments for the bandleader and the first true expressions of his unique voice as a composer. These compositions represent ideal early examples of the “Ellington Effect,” to borrow the famous phrase coined by Ellington’s later writing partner Billy Strayhorn. In this expression, Strayhorn meant to capture both Ellington’s habit of composing and orchestrating specifically for the unique musical talents of his band members, and the distinctive greater whole that was produced when these individual instrumental voices sounded together in the performance of his compositions.20 Both of these early compositions also immerse the listener in the haunting “jungle music” idiom of the Cotton Club era. As heard in these two compositions, the “jungle” idiom owed a great deal to the combination of Ellington’s orchestrations, the collective expression and instrumental voices of his performers, and, most especially, the growl-and-plunger brass contributions of Miley (who was credited as a co-composer on both numbers) and Nanton.

When the critic R. D. Darrell first reviewed the April 1927 Brunswick record of Black and Tan Fantasy, he commented on its “amazing eccentric instrumental effects,” emphasizing that such “stunts” were “performed musically, even artistically.”21 Five years later, Darrell noted that in this first listening he “laughed like everyone else over [the recording’s] instrumental wa-waing … But as I continued to play the record … I laughed less heartily … In my ears the whinnies and wa-was began to resolve into new tone colors, distorted and tortured, but agonizingly expressive.”22 This transformation in Darrell’s view of Black and Tan Fantasy – from “novelty” record to a more culturally elevated “composition” – ultimately laid a major foundation for later critical arguments that held jazz to be an art. This early Ellington criticism – which often provocatively compared Ellington’s rich “orchestral technique” to the music of such classical composers as Igor Stravinsky and Frederick Delius, among others – was quickly recycled as promotional fodder by Mills Artists to reinforce Ellington’s growing public image as a “respected” composer. The English critic Constant Lambert’s 1934 book, Music Ho!, also played a major role in the journalistic reception of Ellington as a “serious composer.” Lambert notably states here that Ellington “is a real composer, the first jazz composer of distinction.”23 In a related trend, from the late 1920s onwards, there were regular press accounts of Ellington’s social and professional encounters with classical musicians – such as his widely reported 1932 invitation from the noted composer Percy Grainger to have the Ellington band perform in a lecture-demonstration in Grainger’s New York University music appreciation class. With such favorable publicity, Ellington’s music came to be positioned as the very definition of new, culturally elevated “jazz composition.”

As Tucker has argued, the originality of a number like East St. Louis Toodle-O was only achieved after Ellington’s “long experience playing Tin Pan Alley pop songs, hot jazz numbers, and the blues.” In finding his own voice, he “had evoked a style that drew upon all these genres, as well as African-American folk music, both secular and sacred … But in a way, even before setting foot in the Cotton Club door, Duke Ellington had arrived.”24 As Tucker further emphasizes, the bandleader’s early years at the Cotton Club formed the “final important phase of his musical education” through his on-the-job immersion in the production processes of the club’s floorshow revues.

Early and mid-century highbrow–lowbrow cultural rhetoric regularly insisted upon rigid distinctions between the spheres of art and entertainment, with the former field retaining great cultural privilege and status, and the vast latter arena being typically viewed (from above) as a cultural wasteland. What is unusual in early Ellington criticism is the readiness of his proponents to characterize him as a “real composer” and to compare his arrangements and compositions to the work of revered classical composers. Such loosely supported comparisons of jazz and classical compositions were key elements in these efforts. While such cultural rhetoric proclaiming the art of both jazz and Ellington’s music was clearly advantageous for his career, and while his early Cotton Club years were central to his training, growth, and fame as a composer, Ellington himself found earlier models for appreciating the art of black popular music – and ultimately jazz – in the work and professional ideologies of his Harlem entertainment mentors and peers. In this tradition, popular music could indeed aspire to be artful entertainment.

Notes

1 , Music Is My Mistress (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973; reprint, New York: Da Capo, 1976), 20, and , Ellington: The Early Years (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 20.

2 Ellington, Mistress, 9. There were various spellings for her name. See also Tucker, Early Years, 23.

3 Tucker, Early Years, 22.

4 Ibid., 25.

5 Ellington, Mistress, 30.

6 , Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 36–37.

7 Reference HasseIbid., 37.

8 Reference HasseIbid., 38–39.

9 See , “The Renaissance Education of Duke Ellington,” in Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance: A Collection of Essays, ed. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990), 111–27.

10 Ellington, Mistress, 28.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., 31.

13 Ibid., 35–36.

14 , “The Making of Harlem,” Survey Graphic, March 1925, 635.

15 See Tucker, Early Years, 103–4.

16 Ibid., 196–98.

17 “Irving Mills Presents Duke Ellington,” a Mills Artists advertising manual from early 1934 (New York: Mills Artists, n.d.), 18. From the Schomburg Center, New York Public Library.

18 Tucker, Early Years, 210.

19 These broadcasts were band features rather than the club’s floorshow revues. See , Ellington Uptown: Duke Ellington, James P. Johnson, and the Birth of Concert Jazz (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009), 127, 315n40.

20 , “The Ellington Effect,” Down Beat, November 5, 1952, 2; reprinted in The Duke Ellington Reader, ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 269–70.

21 , writing in the Phonograph Monthly Review, July 1927; reprinted in Ellington Reader, ed. Tucker, 33–34.

22 R. D. Darrell, “Black Beauty,” in Ellington Reader, ed. Tucker, 58–59.

23 , Music Ho!: A Study of Music in Decline (1934; republished London: Penguin Books, 1948), 155–57.

24 Tucker, Early Years, 258.

2 The process of becoming: composition and recomposition

Nat Hentoff once told me that Duke Ellington often described his music as “in the process of becoming.” One of the things we all love about jazz is its one time only nature – catching lightning in a bottle. Of course, this is in direct opposition to the formal compositional process where specific notes are rendered onto paper for eternity. Jazz composition thus involves a dramatic tension: the integration of improvisation into a planned format. Even after Ellington had solved this problem in a given composition, he continued to look for new ways to achieve that perfection of musical form which, at the same time, would make for fresh performances.

For most artists the commercial recording of a composition, arrangement, or performance is the definitive realization, but for Ellington – and here is the beauty and the frustration – the recording is but one of many performances of an ever-evolving piece of music.

The beauty is in Ellington’s conception of art: “Art is dangerous. It is one of the attractions: when it ceases to be dangerous, you don’t want it.”1 One potential danger in the performing arts is the possibility of change. We wait for a certain something to happen, but maybe it won’t. Maybe something else will be there and change the experience, making it somewhat or even totally different. Maybe we will like it better, or maybe we will like it less. It’s a risk we as listeners take. Ellington not only demands this of us listeners, but also encouraged his players to take risks and inspire him.

A frustration many people have with Ellington is that in a 50-year career he wrote and recorded more music than we can ever digest. If only there were some way to limit it. Some recordings appear identical, but on a closer look, we notice details that are changed. Russell Procope said that he played the clarinet solo on Mood Indigo every night from 1946 to 1974 and never played it the same way twice.2 This solo had the same basic pitches and rhythms as the famous Barney Bigard solo on the initial 1930 recording, but as with many of the Ellington set pieces, Procope was always aware that he had the latitude to change it as he saw fit, whether in small or big ways.

Ellington, unlike most of his fellow bandleaders, was loathe to tell the players too much on how to interpret his music. He wanted the individual band members to express themselves through his music. The spirit was more important than the notes. When he gave directions to the band, most often he would be descriptive (e.g., “give me some personality” and “reeds – you are the train whistle”), leaving the musical details to the players. Often he would tell a story to get what he was looking for.

Clark Terry tells the wonderful anecdote about recording “Hey, Buddy Bolden” from A Drum Is a Woman with Ellington in 1957. There was no written trumpet part for Clark, who told the Maestro that all he knew about Buddy Bolden was that he was the first great jazz musician in New Orleans long ago and that he played the trumpet. But that wasn’t enough information to create a trumpet feature. Ellington told Clark that Buddy Bolden had a sound so big, he could play the trumpet on one side of the Mississippi, and people could hear him all the way on the other shore; that he was the most stylish of dressers and always had all kinds of women following him around; that he would run diminished chords up and down the entire range of his horn like glorious fanfares that would inspire even Gabriel in heaven. Clark said that within a minute or two of hearing Ellington’s descriptive prose, “I thought I was Buddy Bolden.”3

Lawrence Brown, whose early personal dispute with Ellington soured their relationship, but nevertheless didn’t stop him from performing with the orchestra for another 25 years, would always say that Ellington’s real gift was sales. He was a con man of the highest order – he conned audiences into listening to his music and he conned the players into following him anywhere. Perhaps “conned” is a bit strong. Ellington had the ability to get people to want to do what he wanted.

Ellington would jest that he used a gimmick to keep his personnel – he paid them money. But the truth is that he paid them far less than they could earn elsewhere. As Rex Stewart wrote, “Those of us who have had the privilege of working with Duke are constantly reminded of the debt that we owe him for being allowed to be in his orbit.”4 Once an interviewer asked Harry Carney why he stayed so long (47 years). Harry responded that every day he got to go to work and sit down next to some great musicians, and on his stand would be a new piece of music with his name on it written by Duke Ellington. Why would he ever want to leave?5

Process

But what about the actual music? What was the process of composition? In the European classical tradition we tend to think of two opposite processes exemplified by Mozart and Beethoven. In general, Mozart worked quickly with few if any revisions, while Beethoven’s music went through numerous rewrites and changes. Each man achieved greatness through his own method.

So which camp does Ellington fall into? Actually both. Some pieces like Concerto for Cootie and Harlem Air Shaft were performed and recorded nearly as originally conceived. The eight-note motif of Concerto for Cootie came from Cootie Williams. Ellington heard it and offered him a small sum of cash. Since Cootie had no particular interest in doing anything with his lick, this seemed like a fair enough deal to him. Jimmy Maxwell, Cootie’s subsequent roommate in Benny Goodman’s band, once told me that the open horn theme in D-flat major, heard later in the composition, was improvised by Cootie. Since no score or second trumpet part has survived, we can’t know for sure.

On Harlem Air Shaft Ellington changed the title, added a clarinet solo on the third and fifth choruses, and allowed for trumpet improvisation and rhythm section interpretation. Other than that, the famous 1940 recording is quite like the Ellington handwritten score.

Other pieces contain large sections of music that were created in the recording and never written down. For the first three minutes or so of Happy Go Lucky Local (side one of the original 78 record), the original score was scrapped completely and replaced by music created from Ellington’s oral description of a rural train ride through the South. The conductor’s bell, the couplings banging together, the engineer’s whistle, and the other train onomatopoeia are all prelude to the magnificent blues choruses on side two.

Most of Ellington’s music falls somewhere between the two poles of composition and improvisation. Each piece is a case of problem solving by a master problem solver. Ellington’s lack of formal musical training kept him free of the usual tricks and clichés that many other composers, arrangers, and bandleaders employed. Instead he created his own solutions. One example is when Ben Webster was added to the four-man saxophone section, thus making a five-man section. On many of the preexisting charts, Webster was told to play the lead alto saxophone part down an octave. This would strengthen the lead without disturbing any of the harmonies. No new part would need to be created, nor would any of the original parts need to be rewritten. An interesting situation occurred: on the closely voiced sections, Webster’s tenor now sounded a second or third below Carney’s baritone. It is uncommon in most bands to put the baritone anywhere but on the bottom of the saxes or brass. Ellington liked this reversal of roles so much that he continued to use it as an alternative color to the normal saxophone order.

The most famous cliché about Ellington is Billy Strayhorn’s statement that Ellington’s instrument is his orchestra. On a superficial level this can be said about every composer, and certainly about every composer who conducts his own band or orchestra. But in the case of Ellington, it goes much deeper. Ellington wrote not only for a given instrument, but, more specifically, for an individual player with his own particular sound, timbre, personality, and musical sensibilities.

When a player left the band his features were generally retired or rearranged for an entirely different instrument. When new players joined the band, in many cases they would barely solo at all for six months or even a year until Ellington understood their musical personalities and how to integrate them into the sound of the band. Clark Terry’s only solo for a long, long time was Perdido. He often said, “Duke taught us who we were.” Britt Woodman replaced his idol Lawrence Brown in the trombone section. After his first performance with the band (where he played Brown’s solos note for note as he had copied them off the original records), Ellington summoned Britt to his dressing room where he told the young trombonist, “I hired Britt Woodman, not Lawrence Brown.”6

In 1939 three major jazz artists joined the orchestra: Billy Strayhorn (arranger/composer), Ben Webster (tenor saxophone), and Jimmie Blanton (bass). Strayhorn was an enormous help to Ellington, taking on the responsibility of writing nearly all the music Ellington had no time or inclination to write. Blanton revolutionized the way the bass was played in jazz by liberating it from its root functions and making it into a real melodic virtuosic voice. Ben Webster was Ellington’s first tenor saxophone star, melding the styles of Coleman Hawkins and Johnny Hodges.

Two Ellington pieces written in 1939 prior to the arrival of Webster and Blanton did not get recorded until March 6, 1940. Ellington had the challenge of figuring out how to integrate these two powerful personalities into already formed pieces: Ko-Ko and Jack the Bear.

Ko-Ko

Many critics cite Ko-Ko as Ellington’s greatest composition. One can easily see why it would receive such accolades. Like Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring it is at once the most primitive and most sophisticated music in its genre. This basic three-chord minor blues has tom-tom rhythms, plunger growls, and shrieks that go back before slavery all the way to Africa. And yet there is harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, and formal sophistication ten to twenty years ahead of its time.

Little was changed on the recording of this piece from its original conception, with the exception of the two newcomers in the band. Blanton pretty much keeps to the written bass part until the second-to-last chorus, at which point each section of the band plays a scale-wise version of the four-note motif starting at the bottom and ascending to the clarinet at the top. This two-measure cascade is answered by a two-bar bass break, which essentially happens three times. Curiously Blanton, who was known for his outrageous technique and rhythmic and melodic invention, chooses to walk quarter notes in each of the three breaks. His sound and rhythmic propulsion are so astonishing that he makes what should be the weakest instrument in the band (and indeed it usually was until then) into Atlas holding up the world on his shoulders. He continues to walk under the shout chorus (the next 12 measures), further energizing the band in a way that no one in 1940 had ever heard.

Ellington’s solution for Ben Webster was of a different nature – much more subtle, but no less creative. Since all the reed voicings were already in complete four-part harmony, Ellington could use his normal solution for adding a saxophone part – having Ben Webster double the lead clarinet part down an octave. But in the case of Ko-Ko that would not work so well, since it’s a much more harmonically adventurous piece and the doubling would sound too conventional. Ellington wanted something wilder, so he wrote Webster a new part. Fortunately this part (in Ellington’s hand) has survived.

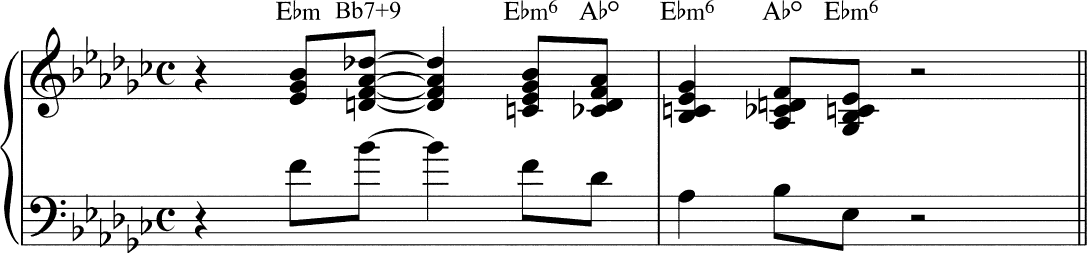

After resting for the introduction, the reeds enter at letter A, answering the valve trombone in rich four-part harmony. Webster’s part adds an extra note to each voicing. His rhythms are identical to the other reeds, but he adds a fifth, and, most notably, dissonant note to each harmony. While skipping from ninths, elevenths, thirteenths, and alterations, he also has an interesting melody of his own. This would be akin to taking a completed crossword puzzle and inserting a letter on each line that would give a deeper meaning to the words. Not just any letters, but odd ones like x, y, z, k, j … (Example 2.1).

Example 2.1. Tenor saxophone part (on bass clef) for Ben Webster on Ko-Ko (Duke Ellington), recorded March 6, 1940, and included on The Blanton-Webster Band, RCA Bluebird 5659–2-RB (CD, 1986).

The climax of this first chorus comes in the ninth and tenth bars, where Webster plays a normal blues melody from the dominant (B♭) to the ♭7 (D♭) of the key (E-flat minor). The genius of this is that at this moment the saxes and rhythm section are playing substitute chords of the ♭VI7 to the V7 (B7 to B♭7), thus making Webster’s notes the major seventh on a dominant ♭VI chord and the augmented ninth of the V7 (Example 2.2).

Example 2.2. Tenor saxophone part (on bass clef) for Ben Webster on Ko-Ko (Duke Ellington), recorded March 6, 1940, and included on The Blanton-Webster Band, RCA Bluebird 5659–2-RB (CD, 1986).

All this sounds natural due to the blues sensibilities that Ellington has created, but surely no one had ever written anything so daring in all of jazz. Where can we go from here?

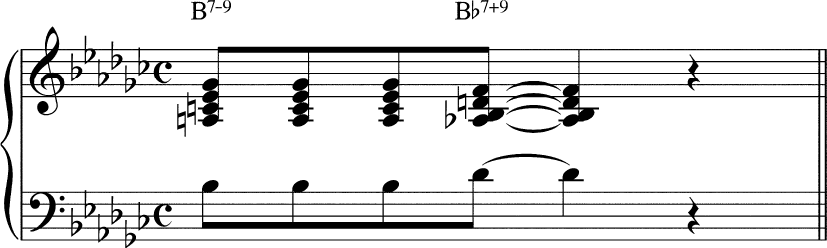

The saxes, including Webster, are unison for the next three choruses. The succeeding chorus has the following call and response pattern: the trumpets play an ascending scale-wise four-note motif in unison and are answered by the harmonized reeds and then the harmonized trombones, each playing a repeated two-note motif. For this chorus Webster’s added pitches are the fifth saxophone and the first trombone, making each section sound richer. For a little icing on the cake, Ellington gives Webster a sixteenth-note turn on his notes with the trombones (Example 2.3).

Example 2.3. Arrangement of winds on Ko-Ko (Duke Ellington), recorded March 6, 1940, and included on The Blanton-Webster Band, RCA Bluebird 5659–2-RB (CD, 1986).

In the following chorus of cascading four-note scale motifs, Webster is the fourth saxophone, the first trombone, the fourth trumpet, and finally the mirror of the clarinet, thus making each section a little fuller and richer than they were in the original conception of the piece (Example 2.4).

Example 2.4. Arrangement of winds on Ko-Ko (Duke Ellington), recorded March 6, 1940, and included on The Blanton-Webster Band, RCA Bluebird 5659–2-RB (CD, 1986).

On the succeeding shout chorus Webster joins Otto Hardwick and Carney in the saxophone unison while Hodges and Bigard are with the dissonant brass voicings. At the end of the coda Webster first is the bottom trumpet, then echoes the baritone motif on the dominant, and finally finishes as the fourth reed on the scale-wise four-note motif much as he did in the sixth chorus.

The beauty of Webster’s part is its absolute integrity. It is as beautiful horizontally (melodically) as it is vertically (harmonically). Once one becomes aware of this tenor saxophone part, it is difficult not to listen for it throughout the arrangement. What should be a minor detail is written in such an interesting way that the informed listener doesn’t want to miss relishing any of it.

Jack the Bear

Jack the Bear presented Ellington with a different set of problems. Whereas Ko-Ko was a fully functioning piece that the band just needed more time to learn to perform, Jack the Bear lacked compositional focus. Here is a case of a piece that might have never been recorded had Ellington not figured out how to fix the arrangement. In this case both Jimmie Blanton and Billy Strayhorn provided the answer.

Ben Webster merely was given the lead clarinet part to play. The tenor saxophone sounds an octave lower than the clarinet, so with the exception of the clarinet solos (where Webster joins the other saxes in unison background figures), the added fifth saxophone merely serves to support the lead part, without adding any extra harmonic information.

In its original conception, Jack the Bear began with an ensemble introduction and used the same material for the coda. Here is where the piece faltered. This material, although not bad in itself, did not introduce or tie up the entire piece in a way that was satisfying. The intro’s relationship of loud/soft and high/low was too blatant. These opposites are explored throughout the piece, but in a much more subtle and integrated way.

Introductions and codas have the heavy responsibility of informing the listener what is about to unfold and then, at the end, summing up what we have heard. These were Ellington’s most difficult sections to write. Most often he would work out a piano introduction on the bandstand or in the recording studio. The spontaneity relieved him of thinking about how important this was, and left him to let his subconscious do the work.

Codas were another story. So often they would be added during the recording session (as in Purple Gazelle from the LP Afro-Bossa) or improvised by band members on the bandstand (Rockin’ in Rhythm and The Gal from Joe’s). Ruth Ellington once told me that her brother, Edward, had a great fear of death, and that writing endings symbolized death to him, hence his trouble writing them. There are some famous Strayhorn codas to complete Ellington arrangements (for example, I Got It Bad and Harlem). But just to be enigmatic, Ellington contributed the coda to Strayhorn’s Take the “A” Train.

In the case of Jack the Bear, Ellington’s son, Mercer, told me that Strayhorn came to New York to work with the orchestra in 1939 just as they were leaving on a European tour. The Maestro instructed Mercer to take care of Strayhorn until they got back. Strayhorn ended up staying in Ellington’s apartment, where he could look through Duke’s scores. One such score was an abandoned piece named Take It Away. Strayhorn came up with the idea for the trombone/reed/bass call-and-response introduction, which begins and ends the piece, thus focusing on a virtuoso bass solo like no one ever heard before. Aside from Blanton’s mastery of the instrument and huge sound, Ellington’s understanding of recording technique led him to have his bassist stand in front of the band – right next to the microphone. Although Ellington had been using this recording setup for years, this was his first recording of a bass feature with the big band, and the results were startling. The bass is a full partner to the rest of the band in terms of volume, intensity, and virtuosity. Furthermore in a mere three minutes Blanton set down the parameters of bass melody and harmony for the next 20 years.

Along with the introduction and coda came a new title: Jack the Bear. It’s no wonder that Ellington discarded Take It Away. Had this piece had something to do with the paring down of the instrumentation (like Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony), then this would have been a fine title. But sometimes Ellington chose working titles hastily just for identification, and after seeing where the piece went, he would come up with something more appropriate. The meaning of Jack the Bear is somewhat elusive. There was an expression around that time, “Jack the Bear, he don’t care,” but that in itself doesn’t pack enough meaning to explain this piece, so scholars dug back further to the early part of the twentieth century and found a New York pianist named Jack the Bear.7 Not a surprising name for that profession, what with Willie “The Lion” Smith and Donald “The Lamb” Lambert as competitors.

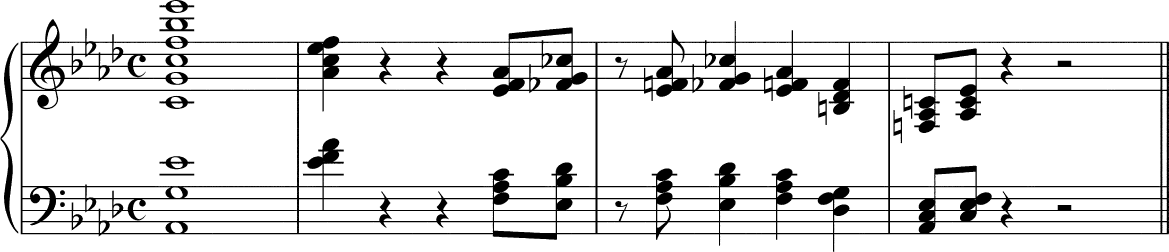

Since Jack the Bear never recorded, we don’t know a whole lot about how or what he played, but, most likely, the unison signal that Ellington uses as a transition throughout the piece (Example 2.5) was either a lick of his that Ellington had learned or it was something that reminded Ellington of his predecessor. It may even have come to Ellington from his mentor, Willie “The Lion” Smith. No matter where Ellington got it from, its harmonic roots in the traditional vaudeville chaser cannot be overlooked. It is this lick that inspires Blanton’s bass lines for the piece, so when we first hear the signal, we experience a feeling of recognition, having heard Blanton’s solo on the new introduction. This is absolutely crucial to the understanding and enjoyment of the piece.

Example 2.5. Unison signal in Jack the Bear (Duke Ellington), recorded March 6, 1940, and included on The Blanton-Webster Band, RCA Bluebird 5659–2-RB (CD, 1986).

This piece is essentially a 12-bar blues with some 8-bar strains interjected. The 8-bar introduction, which uses the reed responses from the first shout chorus by downwardly terracing the dynamics while lowering the octaves on successive statements, was definitely an afterthought. The original chart began on what is now the ninth bar. However Ellington’s piano part in this call and response with the band is new. What he originally conceived was a high loud whole-note chord that resolved to a soft unison quarter note on the downbeat of the second bar. Then the band tutti answer would stay soft for two more bars. This pattern is basically repeated twice, making slight alterations to fit the blues chord progression (Example 2.6).

Example 2.6. Piano chord and band tutti answer in original chart of Jack the Bear (Duke Ellington) in the Duke Ellington Collection, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Publishing rights administered by EMI Robbins Catalog Inc. (ASCAP) and Sony ATV Harmony (ASCAP).

Now here’s the tricky part: Ellington removes the loud chord and its resolution from the original chart and replaces it with a blues motif that arpeggiates the vi minor seventh with half-step chromatic lower neighbor grace notes to the C (Example 2.7).

Example 2.7. Piano and band tutti answer in recording of Jack the Bear (Duke Ellington), recorded March 6, 1940, and included on The Blanton-Webster Band, RCA Bluebird 5659–2-RB (CD, 1986).

The odd thing is that on the fifth bar Ellington repeats this figure almost verbatim instead of using a C♭ to imply the ♭7 on the IV chord of the blues. It could be a IVmajor9, except that Blanton clearly stays on the tonic for the entire eight bars, never even hinting at the D♭ chord. Bars 9–12 do the traditional V to I cadence. They are then followed by the aforementioned unison signal for four extra bars.

The rest of the chart follows as planned until the recapitulation. When the blues chorus without the IV chord returns, it is Blanton who provides the calls to the band instead of Ellington. He also stays on the tonic for eight bars. Following this 12-bar chorus Blanton plays a spectacular chromatic four-bar break ending with an ascending scale up to the tonic. The band plays a tonic thirteenth chord to end the piece.

These are the most famous four measures in all jazz bass playing. Charles Mingus transcribed Blanton’s solos from this piece and kept that sheet of music his whole life. Modern bass playing starts here. But it is not just Blanton’s playing that makes this such a wonderful moment. This cadenza is the logical extension and conclusion of the little four-bar signal that inspired this whole three minutes of music.

If we look at the original score, in place of the final bass solo in the coda there are two bars of ensemble. Then there is some blank space on the paper followed by three alternative A♭7 voicings – none of which wound up being used on the recording. The blank space on the paper shows that Ellington was unsure how he would end this piece. Along comes Jimmie Blanton, and the puzzle is solved.

Coda: an American way of composing

Early in Ellington’s career, Will Marion Cook gave the young composer-bandleader some informal composition lessons while riding in the back of taxicabs. At least two pieces of sage advice became crucial pillars of Ellington’s relationship with pencil and paper.

It was the European-trained Cook who explained the basic processes of musical development – retrograde, inversion, truncation, diminution, and so on. Ellington quickly became a master of these techniques and constantly invented new and wonderful-sounding combinations.

A related tidbit of advice from Cook was not to look to Europe for musical inspiration, but rather to mine the American folk and popular music traditions so that he could create truly American music. And further, Cook advised that when Ellington faced a musical problem, he should figure out how others solved it and then find his own way.

Ellington’s creative problem solving fed on itself year after year, but always in deference to the band’s performance. Once a new piece was composed and arranged, and parts copied, it was placed on the individual music stands where it became the musical property of the musicians. Ellington would let the musicians find themselves in the music, and would gently encourage them to tell a story and to play together nicely. He defined himself as a creator of settings for his great soloists. He saw his job as inspiring his musicians to be great. This generosity created one of the greatest symbiotic relationships in all of Western music.

Notes

1 This quote is widely attributed to Ellington, but its source is unclear.

2 Interview in Memories of Duke documentary (1980), directed by Gary Keys.

3 From the Duke Ellington: Reminiscing in Tempo documentary on PBS television, in the American Experience series.

4 , Jazz Masters of the 30s (1972; New York: Da Capo Press, 1982), 102.

5 , “An Evening with Harry Carney,” Down Beat, May 25, 1961.

6 Britt Woodman conversation with the author.

7 According to Eubie Blake, Jack the Bear’s real name was Wilson: “He had a lot of tricks. You could learn a lot from watchin’ him. He didn’t have to work because he always had women keepin’ him. He was always dressed to kill. Diamonds, everything.” , Eubie Blake (New York: Schirmer Books, 1979), 148.

3 Conductor of music and men: Duke Ellington through the eyes of his nephew

Duke Ellington had synesthesia, a neurological condition characterized by a merging of the brain’s sensory circuitry. He heard sounds as colors and saw colors as sounds. The flight pattern of a bird would occur to him as a musical phrase. The approach of a rumbling train could form a bass line in his head. To him, baritone saxophonist Harry Carney’s “D” was dark blue burlap. Johnny Hodges playing a “G” on his alto sax came across as light blue satin. As a synesthete, Duke experienced the world in a way that was very uniquely his own, a quality reflected in the way he functioned as both a bandleader and a composer. He saw people, situations, and art from a different angle and through a different lens. The lifelong, overriding theme he always harkened back to was one of connectedness and of finding harmonies and beauty where they might not be immediately obvious.

Duke Ellington, my uncle, was my father figure. After the departure of my father, we shared a uniquely intimate relationship. The two of us traveled together all over the globe, sleeping in the same hotel rooms, sharing transport and meals. I also worked as a manager for the band on major tours, and was the impetus behind some of Duke’s historical collaborations. It is from that vantage point that I discuss Duke’s career, with particular focus on his relationship with his band, his partnership with co-composer Billy Strayhorn, and his artistic vision and endeavors in his latter years. Based on my experience with my uncle, a portrait emerges of a bandleader who deftly managed the antics and unbridled egos of his musicians for the greater good of music; of a composer who eschewed conventions; and of a deep thinker who through his music tried to spread a message of unity and commonality to a world divided by politics, religion, and race.

Duke and his men

Given his synesthesia, it is not surprising that Duke referred to his band as his palette. He likened his stage performances to creating a new painting every night. He even conducted with a visually artistic flair, using his up-down, side-to-side strokes to trace the shape of a treble clef in the air. Duke viewed his band as his greatest instrument, but unlike a piano made of inanimate keys, strings, and pedals, each member of the band had a personality attached. And as is often the way with great artists, the personalities behind the Duke Ellington Orchestra were often difficult, headstrong, and temperamental. Part of Duke’s genius was in how he managed the men in his band, creating beauty out of the chaos, and forming what is arguably the most brilliant ensemble in American musical history.

Duke had an exceptionally high tolerance for bad behavior, substance abuse and ill temper from his band. If he valued a player’s talent, Duke – unlike Count Basie, an orderly disciplinarian who managed his musicians in an almost military fashion – would often overlook whatever personal foibles and flaws might come along with the man. Lateness, drunkenness, and personality conflicts were commonplace in the orchestra. Violence between the musicians was known to erupt. Duke worked around whatever problems came his way, especially with his longer-term players, and consistently managed to evoke masterful performances out of his musicians. Once Duke had cultivated a certain sound and sensibility in a player he was loathe to let him go. Additionally, Duke’s complicated chromatic and contrapuntal harmonies often proved disconcerting to uninitiated or strictly traditional players, who would doubt what was written on the staves in front of them at first and second blush.

But that is not to say Duke turned a blind eye to the trouble his musicians stirred up. Newcomers who created issues could be summarily dismissed, as when a young Charles Mingus was fired in 1953. After less than a week with the band Mingus had an altercation with trombonist Juan Tizol. Tizol claimed Mingus tried to attack him with an iron curtain rod after Mingus disagreed with Tizol’s musical instruction. Mingus counterclaimed that Tizol came after him with a knife. While Tizol habitually carried a blade on him, there was no evidence that he came at Mingus, beyond the bassist’s claim. Tizol, an elder statesman of the Ellington orchestra, was deferred to in that episode and Mingus was fired by Duke on the spot. While Duke recognized Mingus as a great talent, and even worked with him a decade later on the album Money Jungle, he did not hesitate to axe the new bassist for the greater good of the band and the security and well-being of an established member, Tizol.

Duke was also known to pink-slip a musician if he didn’t mesh with the rest of the band musically. In the 1960s, at my behest, Duke hired bebop drummer Elvin Jones. Elvin’s reputation and résumé were stellar. A master of percussion, he had worked as a sideman for Mingus and Miles Davis, and was a member of John Coltrane’s quartet. Elvin did not cause any ripples in the band personality-wise. But his playing was too avant-garde for the old guard. So despite Elvin’s great talent and prestige, Duke very politely let him go.

In general, the band’s antics and misbehaviors were dealt with without firings. A skillful reader of people and situations, Duke would let the band members stretch out and follow their impulses right up until the disorder spilled over into their performance. At that point, Duke would intervene. And when that time came, he did not lead through fear or intimidation. Mediation and psychological manipulation were his most commonly used tools for dealing with other human beings. Two to four times a year, the band would reach a point where their wanton ways translated into terrible performances. Duke would wait until a particularly shoddy performance, until the men had boarded the bus with all their instruments packed and stowed away. Then word would begin to spread that Duke wanted to speak with the band.

The idea of Duke setting foot on the bus was cause for alarm. Duke never rode on the band bus, preferring the quiet, calm presence of his driver, baritone saxophonist Harry Carney, to the raucous noise of the bus. So when word got out that Duke would be boarding the band bus, everyone knew it wasn’t good. The band would fall into an uncharacteristic silence, as Duke climbed the steps of the bus. The stillness continued as Duke would begin pacing between the driver’s seat and the back of the bus. Then Duke would speak to the band. Although he never lost control, his anger was evident and his voice was raised.

The speech he would give was always a variation on the theme of togetherness. Duke would tell the band he had worked hard to get himself in this position, and that the band had worked alongside him to put themselves where they were. Duke would tell the band they were not holding up their side of the deal by embarrassing themselves on stage, and if they wanted to remain in their position of prestige they needed to maintain a higher level of performance. Duke would also, in his way, subtly invoke race, reminding the band that they represented black American culture and had a duty to represent their people in a positive light. Then Duke would return to his chauffeured car, leaving the band to ruminate on his words in silence.

These speeches would typically have an instantaneous – though not permanent – effect on the band, causing them to improve upon their musicianship and performances for at least a couple of months. Then, inevitably, the backward slide would begin again, resulting in another subpar performance and another visit by Duke to the band bus. This cycle could not be ended. It was a dilemma inherent in Duke’s formula of choosing the best talent and the best musicians for his artistic vision, despite the problems they might bring with them. The train would inevitably run off the tracks; Duke could only learn to cope and right the course.

Duke’s most effective weapons in corralling his band were his words, which he used in wide range and with great fluidity. He could gently coax, intelligently argue, or slice to the heart of someone’s weakness. The only commonality in his usage is that he was hardly ever direct, always preferring insinuation and suggestion. In the 1960s, the band was playing at jazz impresario George Wein’s club Storyville in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Backstage, trumpeter Willie Cook was waiting to go on, projecting his usual arrogant attitude and the cool aloofness of a hipster. Willie, a handsome, fine-featured man, was a heavy drug user and known to cause trouble. Not long before the Storyville gig, Willie had been among a group of band members arrested for narcotics while the orchestra was in Las Vegas. The arrest caused Duke professional embarrassment. As Duke rushed on to the stage at Storyville, he accidentally stepped on Willie’s feet. Willie puffed up in anger and shouted at Duke: “Hey man, you stepped on my foot.” Duke stopped and stared Willie directly in the eye. “You stepped on my life,” Duke said abruptly, and without apology, before he turned on his heel and kept on going.

But Duke did not like to have bad words with people. He tended to mediate disputes, again using the idea of togetherness and a common goal to bring warring musicians around. Cat Anderson was one of the most volatile personalities, a prickly man who had to be handled with a delicate touch. Cat was known for playing extremely high notes on his trumpet that would shrill above the rest of the band. An orphan from South Carolina, he was mercurial and could shift from a back-slapping good mood one moment to extreme fits of rage the next. His temperament, combined with the trying schedule of the road, often resulted in fights. In the late fifties, during a concert at an outdoor amphitheater in Detroit, drummer Sam Woodyard hit his cymbal, which loosed and flew across the stage, hitting Cat in the back of the head. Cat, convinced this was a personal affront, launched into a screaming fit and stormed off stage. Duke kept on playing as if the entire scene had never occurred, finishing the number before smoothly calling for an unplanned intermission. Cat needed a great deal of handling and cajoling to be convinced to rejoin the band after the break. But somehow Duke assuaged Cat, who agreed to finish the show and to temper his accusation that Woodyard had tried to kill him.

More typically, conflicts within the band were of a more mundane nature. Musicians would come into Duke’s dressing room with grievances about their pay, or the music, or another band member. Duke would usually be in his typical rest position, legs up on the wall, silk kerchief covering his eyes. Or he would be writing away, already rethinking the previous performance for the next day. Duke would calmly defuse the complainants’ concerns, redirecting their thoughts with his verbal gymnastics, or coolly assuring them that they would be taken care of.

Most of the major eruptions and misadventures in the band were sparked by volatile personalities like Cat, or by the heavy drinkers and drug users, such as Paul Gonsalves, Ray Nance, Sam Woodyard, and Willie Cook. Johnny Hodges, the alto saxophonist whose signature smoothness of tone became synonymous with the Duke Ellington orchestra, was not of that ilk. Johnny was among the band members who seemed to be constantly perturbed about one thing or another. Senior in status and superior in talent, Johnny harbored a condescending attitude. He would come up to Duke, tap his arm repeatedly, and then launch into a lengthy speech about how Duke should be running the band. Johnny would also constantly threaten to leave the orchestra, although he actually ventured out only once to form his own group. Johnny was gone from 1951 to 1955, before returning to both Duke and his old petulant ways. Duke composed songs for Johnny, such as Jeep’s Blues, to feature his unmistakably silky tones and the uncanny timing of his phrasing. Duke based the songs on riffs that Johnny had played for him. But Johnny felt entitled to royalties for the music he inspired, and would rub his thumb and forefinger together when these songs were played to display his dissatisfaction.

But in truth, while Duke might have based Jeep’s Blues on a riff or some noodling, he was never one to deny an enterprising musician his due as a composer. Duke was sensitive to giving musicians credit for their work. Before he formed his own publishing company – Tempo Music – in 1941, publishers such as Irving Mills and Jack Robbins routinely attached their names to Duke’s work. It wasn’t until Duke formed Tempo that he had complete control over attributing credit where it was due. Duke encouraged his musicians to take advantage of the publishing opportunities that Tempo offered and gave broad play, both on stage and in the recording studio, to the songs of his musicians. Billy Strayhorn’s Take the “A” Train is perhaps the most famous example of this, followed by Juan Tizol’s Caravan and Perdido. But lesser-known pieces abound, such as Johnny Hodges’ Squatty Roo and Cat Anderson’s Trombone Buster, a piece written to feature Buster Cooper, whose trombone playing mirrored his speech pattern, which was marked by a series of sputtering stutters followed by energetic bursts of exclamatory phrases. And if Duke contributed to another band member’s piece, he would regularly grant attribution to both parties, as in his collaborations on Air Conditioned Jungle with Jimmy Hamilton and Rent Party Blues with Johnny Hodges. For Duke, musical credit was not a zero-sum game. He was secure in his reputation and status, and felt there was enough credit, glory, and stage time to go around.

Duke did not have much patience for haggling over financial matters, nor did he have much respect for musicians who used offers from other bands to leverage a higher paycheck. When trumpeter Cootie Williams left the band for a better-paying position with Benny Goodman in 1941, Duke did not counteroffer or try to convince him to stay. This remained a lifelong offense to Cootie despite his deep admiration for Duke as a composer and musician. Duke wasn’t pleased with the thought that his players were thinking of leaving him, and while he handled day-to-day gripes about money with aplomb, he found it particularly distasteful that someone would leave his orchestra for the sake of money.

Duke could be very personally generous with his musicians. Paul Gonsalves, the tenor saxophonist whose solo brought the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival to its feet, had the smooth sound of more traditional players, such as Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster, with some of the bebop stylings of Charlie Parker. Paul was known for his great affability. He was equally known for his extreme drunkenness – a trait that Duke disliked, but tolerated. Duke called him “The Ambassador,” a reference to his ability to charm and disarm everyone he met on the road regardless of their background. Duke would position Paul front and center during tours sponsored by the U.S. State Department, since Paul was sure to win over whatever dignitaries were in front of him. But Paul was also a constant source of trouble to Duke and the band due to his alcoholism. He once disappeared on the road in Japan after missing our stop on the bullet train. But in quintessential Paul Gonsalves fashion, he somehow commandeered a crew of rice paddy workers to drive him back to the city where the band was performing. Paul’s long-term alcoholism and substance abuse eventually resulted in his suffering from seizures. On one occasion, Paul began seizing during a flight over Europe and we had to get special emergency clearance to land in Greece during a military coup d’état.

Late one night, after playing a gig in Las Vegas, Paul decided he would go into Duke’s dressing room to complain about his pay. Paul had been fulminating for a couple of days after realizing that he was the only man in the band who did not own his own home or car. So Paul shored up his nerve, gathered his thoughts, and began ferociously banging on Duke’s door, expecting an argumentative retort from Duke. “Door’s open,” Duke responded calmly, diffusing Paul before he even came in the room.

Paul entered to find Duke deep into a composition, pen and paper in hand. “Paul, it’s good to see you, but I’m writing,” Duke said. Paul persevered, saying he wanted more money so he could get a house and a car like the rest of the band, and that he wanted to talk about it right that minute. Paul’s wife, Joanne, was living in Rhode Island and had grown tired of not seeing her husband, who was spending his time in New York and on the road. Upon hearing Paul’s complaint, Duke wearily got up from his seat, put his arm around Paul, and launched into a speech, which began, “Paul, you and I are both artists, so I know you understand I need this time to get things done.” Somehow, Paul soon found himself in the hallway, alone with no answers and not a cent more in his paycheck. In fact, Paul claimed that after Duke’s brain twisting, he had forgotten why he even went to see Duke in the first place. Paul managed to pull himself together enough to broach the topic again the next day, and Duke told him that they would be back in New York in eight days and would deal with it then. Duke then conveyed the situation to my mother, Ruth Ellington, and his son, Mercer, back in New York. My mother and Mercer went about making arrangements for Paul and Joanne to purchase a house in Long Island. Two days after the band got back to New York, Duke had Paul picked up in a chauffeured Cadillac. The car took Paul to Long Island, right to the doorstep of his new home. This incident is very indicative of Duke’s generosity as well as his indirect, often unexpected way of dealing with his men.

But Duke did not have such a warm relationship with everyone in his band. He was almost as notorious for his skills of seduction as he was for his music, but he rarely kept the same woman around for long. Such was the case with actress Fredi Washington, who had a short-lived affair with Duke. But while Duke lost interest in her, she always carried a torch for him, even after her marriage in 1933 to Lawrence Brown, a trombonist with the band. Lawrence was aware of his wife’s unrequited yearning for Duke and harbored a quietly simmering animosity towards him. Lawrence stayed with the band, aside from venturing off with Johnny Hodges in the early 1950s, for the steady paycheck. While Duke was aware of Lawrence’s negative attitude and grumblings, he was immune to their impact. Such personal pettiness barely pinged on his radar. He employed Lawrence for his ability as a player and his musical contribution to the band, despite his sourness.

Music was the metric by which Duke Ellington made his decisions – not ego, not personality, and not what was most easy or conventional. In Duke’s world, the music always came first. This is how he led his life and his band, and how he managed to overcome an almost insurmountable degree of chaos and conflict to bring an assembly of the greatest players of his time together on a near-nightly basis.

Duke and Strays

Duke’s relationship with my godfather, Billy Strayhorn, was one of the most pivotal and influential of his life, professionally and personally, musically and emotionally. Duke and Strayhorn first crossed paths in Strayhorn’s native Pittsburgh in 1938. Strayhorn had had a couple of months of classical training at the Pittsburgh Musical Institute and had been working at a drugstore as a soda jerk and delivery boy. After an Ellington concert, Duke heard Strayhorn perform a song that he had composed and set lyrics to, and immediately sensed a great talent and a sympathetic intellect. Duke was so impressed he hired the 23-year-old on the spot as a lyricist, and soon moved him in to live with his only child, Mercer Ellington, and my mother, his only sibling, Ruth Ellington.

Duke’s initial impression of Strays proved prescient. Very early on, Duke began to cultivate Strayhorn’s prodigious talent in both composing and arranging. Duke did not believe in coddling great talents, and his initial methods for training Strayhorn were very much “sink or swim.” One of Strayhorn’s first assignments with Duke was to arrange two pieces, “Like a Ship in the Night” and “Savoy Strut,” for Johnny Hodges in a small-group session. In addition to similar trials by fire, Duke worked closely with Strays, teaching him the particulars of his inner world as a composer. In the early years of their collaboration, Duke spent a great deal of time teaching Strays the fundamentals of the harmonies that he was trying to achieve with the band, and how he wanted to layer the instruments within a composition. Strays readily absorbed Duke’s ideas and eventually contributed his own artistic vision.

Strayhorn came into his own as a composer in part thanks to a radio industry boycott against the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1941. Duke was an ASCAP member, so his material was off-limits on the radio for the duration of the strike. Mercer and Strayhorn were not ASCAP members, so Duke commissioned them to compose a new band book. But Duke’s compulsion to compose could not be quelled. On the sly, he had more than a little hand in Mercer’s and Strayhorn’s work during this period; for example, “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be” is attributed to Mercer but came more from Duke’s mind. But Strayhorn showed marked development during that period, composing Passion Flower and Chelsea Bridge.

Ever subdued and reserved, Strays hated the limelight, preferring the comfort of his home and the company of his friends to the rigors of the road. On the rare occasion that Strays would attend a performance, my uncle would unfailingly call him up to the stage to sit in and play something – often Take the “A” Train. Strays would trudge up to the stage with palpable reluctance. When Strayhorn was not around, Duke would make every effort to credit him as the composer of whatever Strayhorn material was performed.

While Strayhorn was an undeniable genius as a composer, he did not have the best temperament for tangling with the rough and difficult personalities of the band. He was gentle, intellectual, and soft-spoken, an anomaly in the hard-charging, often odious, sometimes violent world of jazz musicians. But that does not mean Strayhorn always remained in the background. In 1956, I witnessed Duke and the orchestra recording the Ellington songbook with Ella Fitzgerald. Duke and Strayhorn collaborated on the 16-minute, four-movement Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald, in which Duke and Strays took turns at the piano and in a semi-scripted verbal tribute to the great songstress. The recording is a prime example of Duke’s willingness to share the stage with Strayhorn on major projects, and also highlights the marked difference between them as pianists – Duke playing with rawness and the sensibility of an arranger, and Strayhorn showing his classical, more restrained bent.

One consistent exception to Strayhorn’s tendency to skirt the edge of the action was when his song “Lush Life” was performed. This melancholic song of lost love was extremely personal for Strayhorn, and he was very exacting and demanding about the way it was sung. He invariably became very emotional about the phrasing and emotional timbre of those who dared to sing it in his presence. In addition to being the song closest to his heart, “Lush Life” is the prototypical example of how Strayhorn’s style differed from Ellington’s. Strayhorn had an openness and emotional vulnerability that was all his own. The melancholia, earnestness and bittersweet longing of “Lush Life” is a contrast to Duke’s raw sensuality and his tongue-in-cheek approach to both life and musical composition.